1 Laboratory of Human Anatomy and Cell Biology, Faculty of Health Sciences, Tsukuba University of Technology, 305-8521 Tsukuba, Japan

Abstract

Cell-to-substrate adhesion sites, also known as focal adhesion sites (FAs), are complexes of different proteins on the cell surface. FAs play important roles in communication between cells and the extracellular matrix (ECM), leading to signal transduction involving different proteins that ultimately produce the cell response. This cell response involves cell adhesion, migration, motility, cell survival, and cell proliferation. The most important component of FAs are integrins. Integrins are transmembrane proteins that receive signals from the ECM and communicate them to the cytoplasm, thus activating several downstream proteins in a signaling cascade. Cellular Proto-oncogene tyrosine-protein kinase Src (c-Src) and focal adhesion kinase (FAK) are non-receptor tyrosine kinases that functionally interact to promote crucial roles in FAs. c-Src is a tyrosine kinase, activated by autophosphorylation and, in turn, activates another important protein, FAK. Activated FAK directly interacts with the cytoplasmic domain of integrin and activates other FA proteins by attaching to them. These proteins activated by FAK then activate other downstream pathways such as mitogen-activated protein kinase (MAPK) and Akt pathways involved in cell proliferation, migration, and cell survival. Src can induce detachment of FAK from the integrin to increase the focal adhesion turnover. As a result, the Src-FAK complex in FAs is critical for cell adhesion and survival mechanisms. Overexpression of FA proteins has been linked to a variety of pathological disorders, including cancers, growth retardation, and bone deformities. FAK and Src are overexpressed in various cancers. This review, which focuses on the roles of two important signaling proteins, c-Src and FAK, attempts to provide a thorough and up-to-date examination of the signal transduction mechanisms mediated by focal adhesions. The author also described that FAK and Src may serve as potential targets for future therapies against diseases associated with their overexpression, such as certain types of cancer.

Keywords

- focal adhesion (FA)

- extracellular matrix (ECM)

- integrin

- focal adhesion kinase (FAK)

- c-Src

Cell-to-substrate adhesion sites, also known as focal adhesions, are dynamic multi-protein complexes that act as vital hubs for bidirectional communication between cells and the extracellular matrix (ECM) [1]. Integrins, a type of transmembrane receptor, connect the cytoskeleton of the cell to the ECM, providing a mechanosensitive platform for signal transduction. Focal adhesions (FAs) play an important role in perceiving mechanical cues from the surrounding microenvironment, such as ECM stiffness, topography, and forces created by neighboring cells or tissue tension via integrin clustering and contact with ECM components [2].

Different cytoplasmic proteins interact directly or indirectly with activated integrins, which are essential for FA assembly and disassembly. Focal adhesions are large protein complexes that include structural proteins such as talin, vinculin, paxillin, alpha-actinin, and a kinase called integrin-linked kinase (ILK). These proteins are involved in cross-linking of actin to integrin. These structures connect integrins to the actin cytoskeleton and initiate signaling pathways. Talin and vinculin coordinate interaction between integrin and the actin cytoskeleton to provide rigidity and signaling. Paxillin is an example of a scaffold protein where it recruits other focal adhesion proteins. Alpha-actinin, one of the spectrin superfamily members, cross-links actin filaments to provide additional structural strength to the cytoskeletal network. ILK binds to integrins and other focal adhesion proteins; it is involved in the direct linking of integrins to the actin cytoskeleton and regulation of cell adhesion, spreading, and migration [3]. Migrating and nonmigrating cells interact with each other by phosphorylating downstream targets and signal transduction pathways. For example, cadherin-mediated adhesion, the cytoplasmic domain of cadherins, interacts with catenins that link to the actin cytoskeleton. Some intracellular points of signaling convergence upon ligand binding by integrins include the focal adhesion kinase (FAK) pathway and the phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase (PI3K)/Protein kinase B (Akt or PKB) pathway, which promotes cytoskeletal changes required for migration and attachment.

Focal adhesions not only function as mechanical sensors but also as integrative signaling centers, converting mechanical inputs into a diverse range of intracellular signaling events [4]. Proliferation, differentiation, cell migration, and survival are all regulated by these signaling pathways. Due to their crucial significance in cellular processes, abnormal focal adhesion signaling has been linked to a variety of physiological and pathological conditions, from cancer and cardiovascular metastasis to tissue homeostasis and embryonic development [5].

FAK and Cellular Proto-oncogene tyrosine-protein kinase Src (c-Src), two non-receptor tyrosine kinases, coordinate many cellular tasks such as adhesion, migration, proliferation, and survival. They are detected in physiological and pathological processes, including cancer. It is, therefore, essential to establish the clinical relevance of FAK and c-Src toward the discovery of targeted treatments and enhanced results for cancer patients [6]. FAK is a significant controller of the signal transduction involved in integrin activation. It enriches focal contacts, links ECM with actin filaments, and regulates cellular migration and signaling. Through autophosphorylation of tyrosine 397 (T397), FAK’s activation helps recruit Src family kinases that prompt the signaling pathways, including PI3K/Akt and mitogen-activated protein kinase (MAPK)/extracellular signal-regulated kinase (ERK). These pathways control cell survival, cell division, and cell motility; hence, FAK is essential in cellular processes [7]. Nevertheless, FAK is reported to be overexpressed in several cancers such as breast, prostate, colon, and pancreatic cancers. Its overexpression is associated with increased tumor growth, invasiveness, and metastases. FAK induces epithelial-mesenchymal transition (EMT), resulting in migratory and invasive ability of the cells, contributing to metastasis. Therefore, these findings reaffirm that FAK is an essential protein in the maintenance of cancer stem cells and modifying tumor microenvironment, pointing to the significance of this protein in cancer progression [8].

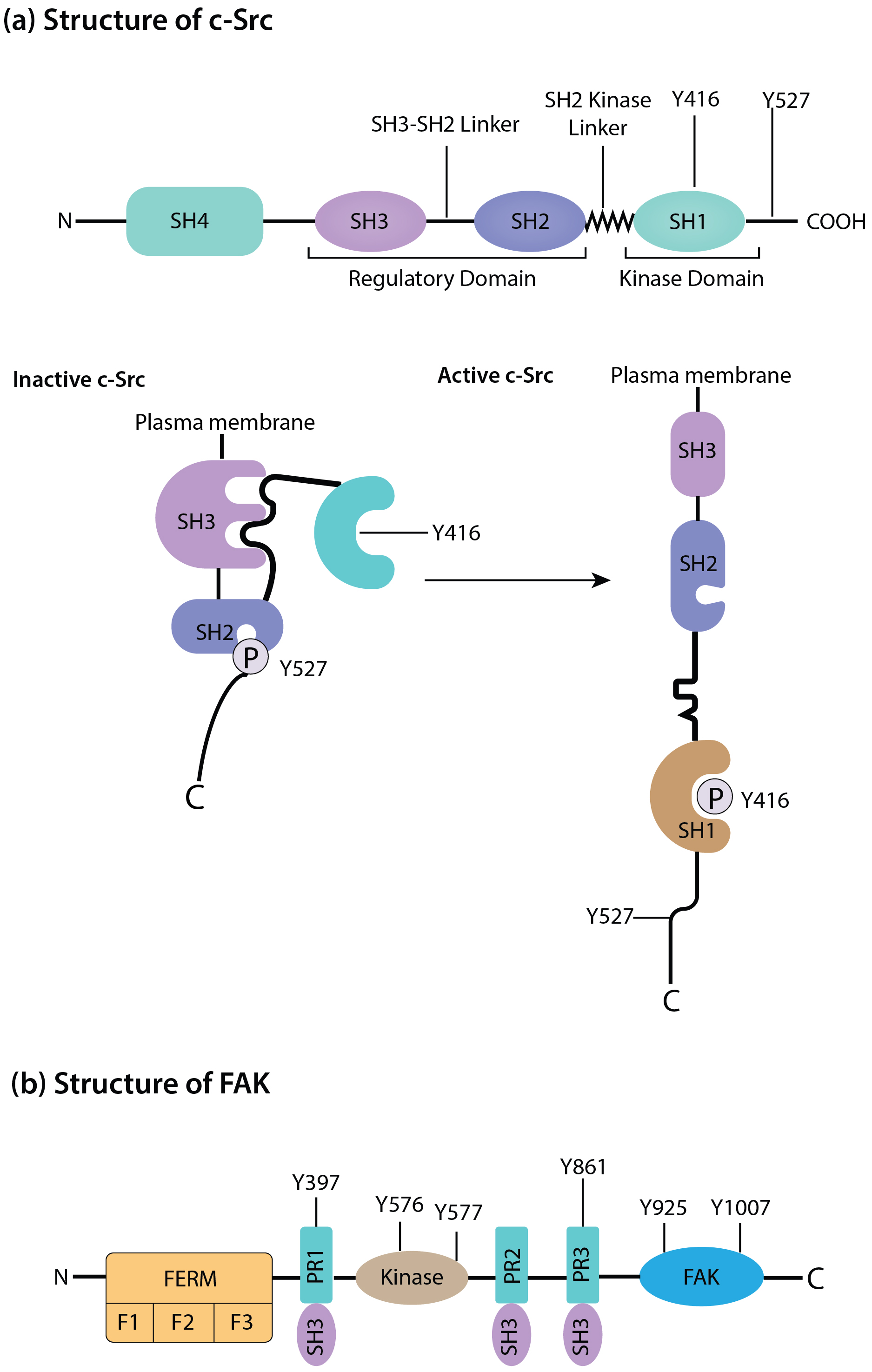

c-Src is categorized under the Src family kinases and is primarily found in signaling pathways such as growth factor receptors, integrins, and other surface molecules. c-Src is involved in cytoskeletal rearrangements, cell proliferation, and cell survival through the phosphorylation of the substrate molecules [9]. Like FAK, c-Src is overexpressed or hyperactivated in numerous malignancies. It objectively supports tumor development by stimulating and enhancing cell growth, resistance to cell death, blood vessel formation, and cancer spreading. c-Src plays a crucial role in cancer cells’ invasiveness through direct control of focal adhesion turnover, actin cytoskeleton dynamics, and MMP production and release. The c-Src/FAK complex is essential, especially for metastatic dissemination through detachment, migration, and invasion of cancer cells [10]. The structures and composition of FAK and c-Src are shown in Fig. 1.

Fig. 1.

Fig. 1.

Schematic of the structure and composition of c-Src (a) and focal adhesion kinase (FAK) (b). The duster of c-Src and FAK have a central role in signal transduction. During autophosphorylation at Tyr397, FAK systematically acquires a new binding site to the SH2 domain of c-Src, subsequently activating it. N, N-terminal domain; C, C-terminal domain; F, subdomains of FERM; FAT, focal adhesion kinase targeting domain; FERM, four-point-one, ezrin, radixin, moesin domain; PR, proline rich motifs; SH, Src homology; c-Src, Cellular Proto-oncogene tyrosine-protein kinase Src; P, phosphoric acid.

This review focuses on the roles of two important signaling proteins, c-Src, and FAK, and attempts to provide a thorough and up-to-date examination of the signal transduction mechanisms mediated by focal adhesions. c-Src, a non-receptor tyrosine kinase, belongs to the Src family of kinases (SFKs) and is essential for the control of cell growth, survival, and migration. The cytoplasmic tyrosine kinase FAK, on the other hand, functions as a key modulator of focal adhesion signaling and binds to activated integrins.

This review also attempts to combine the knowledge now available on focal adhesion signaling, highlighting the essential roles of c-Src and FAK in these complex cellular processes. Furthermore, it aims to illuminate the therapeutic potential of altering focal adhesion signaling pathways, providing fresh opportunities for the creation of targeted treatments for a variety of disorders characterized by focal adhesion dysregulation.

Complex macromolecular assemblies, known as focal adhesions, develop at the boundary between the extracellular matrix and the cell membrane [11]. Integrins, which are heterodimeric transmembrane receptors, are the primary components of focal adhesions. Integrins oversee the cell’s capacity to cling to and communicate with different elements of the extracellular matrix (ECM), including collagen, fibronectin, and laminin [11]. A wide variety of cytoplasmic signaling and structural proteins are attracted to and organized by the clustering and activation of integrins because of their binding to ECM ligands.

Focal adhesions vary dynamically because of integrin activation, moving through several stages of assembly and disassembly. The structural proteins vinculin, talin, and paxillin are crucial in the development of focal adhesions [12]. Talin is essential for connecting the cytoplasmic tails of integrins to the actin cytoskeleton, which facilitates integrin clustering and signaling [13]. Vinculin interacts with both talin and actin filaments, functioning as a molecular clutch to control the intensity of integrin-ECM connections [14]. Paxillin is a multifunctional scaffolding protein that helps maintain the stability and dynamics of focal adhesions by attracting numerous signaling molecules and actin regulators [15].

Integrins, a diverse family of receptors, allow cells to interact with a wide range of ECM ligands. Integrins are transmembrane proteins that have various subunit combinations. Each integrin receptor has two extracellular heads and two short intracellular legs. Extracellular heads bind with the ligand in ECM and also maintain subunit association [16]. To facilitate intracellular signaling and cytoskeletal organization, each integrin subunit has a brief cytoplasmic domain that interacts with particular focal adhesion proteins. The focal adhesion proteins, including talin, kindlins, and integrin-linked kinase (ILK), interact with the cytoplasmic tails of integrin subunits. The clustering and activation of integrins upon ligand binding depend on these interactions [17].

Large cytoskeletal protein talin connects activated integrins to actin filaments by directly binding to their cytoplasmic tails. Focal adhesions can react to changes in the cellular microenvironment because this contact is controlled by intracellular signals, such as mechanical force and phosphorylation processes [18]. By facilitating integrin clustering and increasing integrin avidity for ECM ligands, kindlins also play a significant role in integrin activation. Additionally, ILK affects focal adhesion dynamics and signaling by acting as a link between integrins and the actin cytoskeleton [17].

The highly controlled processes of focal adhesion formation and maturation involve a complex network of signaling proteins, enzymes, and adaptors. These elements work together to support focal adhesions’ structural stability and functional adaptability, allowing them to control a variety of cellular responses in response to environmental signals [19].

Overall, knowledge of the molecular structure and construction of focal adhesions reveals vital insights into the processes that underlie their generation, control, and functional importance. Essential activities, including proliferation, cell migration, and tissue development, are made possible by the dynamic nature of these adhesion sites, which also give cells the ability to control their adhesion and signaling qualities. Focal adhesion signaling dysregulation can cause a variety of clinical illnesses, making this field of study promising for therapeutic approaches aimed at diseases related to focal adhesion.

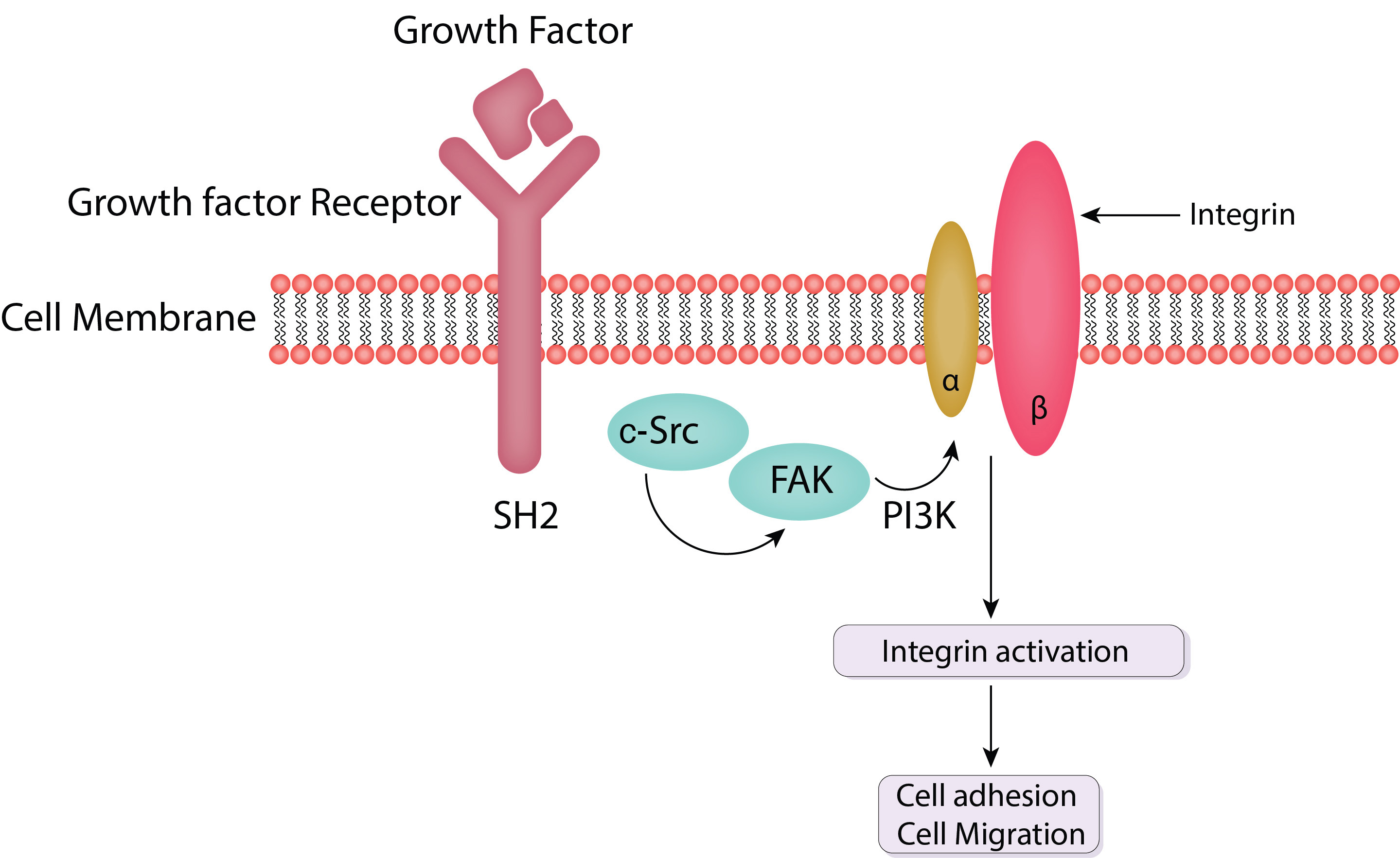

The extracellular matrix (ECM)’s mechanical and chemical inputs are transformed into intracellular responses by focal adhesions, which serve as integrative signaling platforms. These signaling events regulate a wide range of cellular activities and are governed by a dynamic network of proteins and enzymes. The main focal adhesion signaling pathways are discussed in detail in this section, with an emphasis on the functions of Src and FAK (Fig. 2) [20].

Fig. 2.

Fig. 2.

Schematic of FAK and c-Src mediated cell adhesion and cell migration. FAK is activated by integrins upon their binding to the extracellular matrix (ECM). This activation is marked by autophosphorylation at tyrosine residue pY397, creating a high-affinity binding site for Src family kinases. Activated FAK forms a complex with Src, leading to further phosphorylation of FAK and other focal adhesion proteins. PI3K, phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase; SH2, Src homology 2 domains; FAK, focal adhesion kinase; c-Src, Cellular Proto-oncogene tyrosine-protein kinase Src.

Integrins are critical in initiating focal adhesion signaling. When integrins connect to certain ECM ligands, they undergo a conformational shift that promotes clustering and activation. This activation sets off a chain of intracellular signaling processes that include the capture and activation of focal adhesion proteins, including talin, kindlins, and integrin-linked kinase (ILK) [21].

Integrins are cytoplasmically linked with non-receptor tyrosine kinases such as FAK and Src. These kinases are essential for signal transmission downstream of activated integrins. In addition, integrin clustering promotes the recruitment of structural and signaling proteins such as talin, paxillin, vinculin, and FAK [12].

Integrin activation leads to the activation and clustering of various adhesion proteins. This clustering ultimately leads to the connection of activated integrin to the cytoskeletal elements, including F-actin filaments [22]. This section describes the role of the adhesion proteins, which engage in the complex cascade leading to the activation of F-actin filaments.

Talin is a homodimeric protein with globular head and tail regions. It possesses a four-point-one, ezrin, radixin, moesin domain (FERM) domain in its head region, which has a high affinity for binding with the tail region of integrin. The FERM domain also has an affinity to bind with F-actin and FAK. The tail region of talin possesses a domain that has a poor affinity to bind with activated integrin. The tail region also has domains for actin and vinculin binding. These interactions make talin an important player in cell adhesion through the signaling cascade after integrin activation [23]. FERM domain also binds with and activates phosphatidylinositol-4,5-phosphate-Kinase gammma (PIPKIᵧ). Activated PIPKIᵧ stimulates the production of phosphatidylinositol-4,5-bisphosphate (PIP2), which in turn activates other cell adhesion proteins.

Recently, it has been investigated whether talin contains multiple binding sites for actin, which plays a crucial role in cell adhesion. Mutations in all these actin-binding sites of talin in Drosophila led to lethality. However, if all the actin-binding sites are not mutated, then existing normal actin-binding sites replace the function of mutated ones [24]. Furthermore, it was discovered that talin knockout embryonic stem cells failed to adhere to the ECM in culture [25]. Moreover, talin knockout in mice caused embryonic lethality [26]. Therefore, talin is one of the most important cell adhesion proteins, which plays a vital role in cell adhesion to the ECM.

Vinculin consists of a globular head and a tail region. Vinculin indirectly

binds with activated integrin tails. The globular head region of vinculin has

domains that can bind with talin and

It was found that vinculin knockout fibroblasts were highly motile and possessed minor cell-to-matrix adhesions [31]. Recently, it has been investigated that phosphorylation of tyrosine residue Y822 on vinculin is critically involved in cell adhesion. It was found that cells with Y822C mutated vinculin had high rates of cell proliferation, high motility, and minor cell adhesion [32].

In this way, vinculin plays a crucial role in the indirect interaction of cytoplasmic tails of integrin with F-actin cytoskeletal elements and in the maintenance of focal adhesion.

Integrin-linked-kinase (ILK) is a serine/threonine kinase. It binds with cytoplasmic tails of activated integrin. The C-terminus of ILK has a domain that interacts with other cell adhesion proteins, such as paxillin, and a group of F-actin-binding proteins called parvins. The N-terminus of ILK has a PH domain through which it binds with PINCH1 and PINCH2 (LIM domain-containing proteins). PINCH1 and PINCH2 are two proteins that interact with various proteins and participate in the actin cytoskeleton response to extracellular signals received by integrin.

ILK overexpression is linked to certain cancers, making it a potential target for cancer [33]. Recently, it has been found that myeloid-specific ILK overexpression contributes to colorectal cancer. Targeting myeloid-specific ILK has the potential to treat colorectal cancer [34].

Hence, ILK plays a crucial role in cell adhesion by activating other proteins in a signaling cascade. This leads to the indirect interaction of different cell adhesion proteins with cytoplasmic tails of activated integrin in response to extracellular stimuli. ILK is potentially a therapeutic target for various disorders such as cancer, which are linked with ILK overexpression.

Paxillin is an adaptor protein that is involved in cell adhesion. The C-terminus of paxillin possesses four zinc finger motifs. Two of these zinc finger motifs assist paxillin to localize in the cell-matrix adhesion. The N-terminus of paxillin has five Paxillin LD consensus (LDxLLxxL) motifs that recruit vinculin, FAK, and ILK. FAK and Src phosphorylate tyrosine residues of paxillin and create Src homology 2 (SH2) domain binding sites. Paxillin’s SH2-binding sites stimulate CSK (C-terminal Src kinase) [35, 36] and CRK (CT10 regulator of kinase) [37, 38]. Following recruitment by the paxillin SH2-domain, CRK activates other cell adhesion proteins in a signaling cascade that leads to cell adhesion.

Recently, a tyrosine residue Y118 has been found on paxillin. Y118 plays a crucial role in cell adhesion. It was found that if Y118 on paxillin is made resistant to phosphorylation, it disintegrates focal adhesions and encourages cell migration in the zebrafish model [39], demonstrating the role of paxillin in cell-matrix adhesion. It also reveals how paxillin is involved in indirectly connecting various cell adhesion proteins to the activated integrin in focal adhesion sites on the cell.

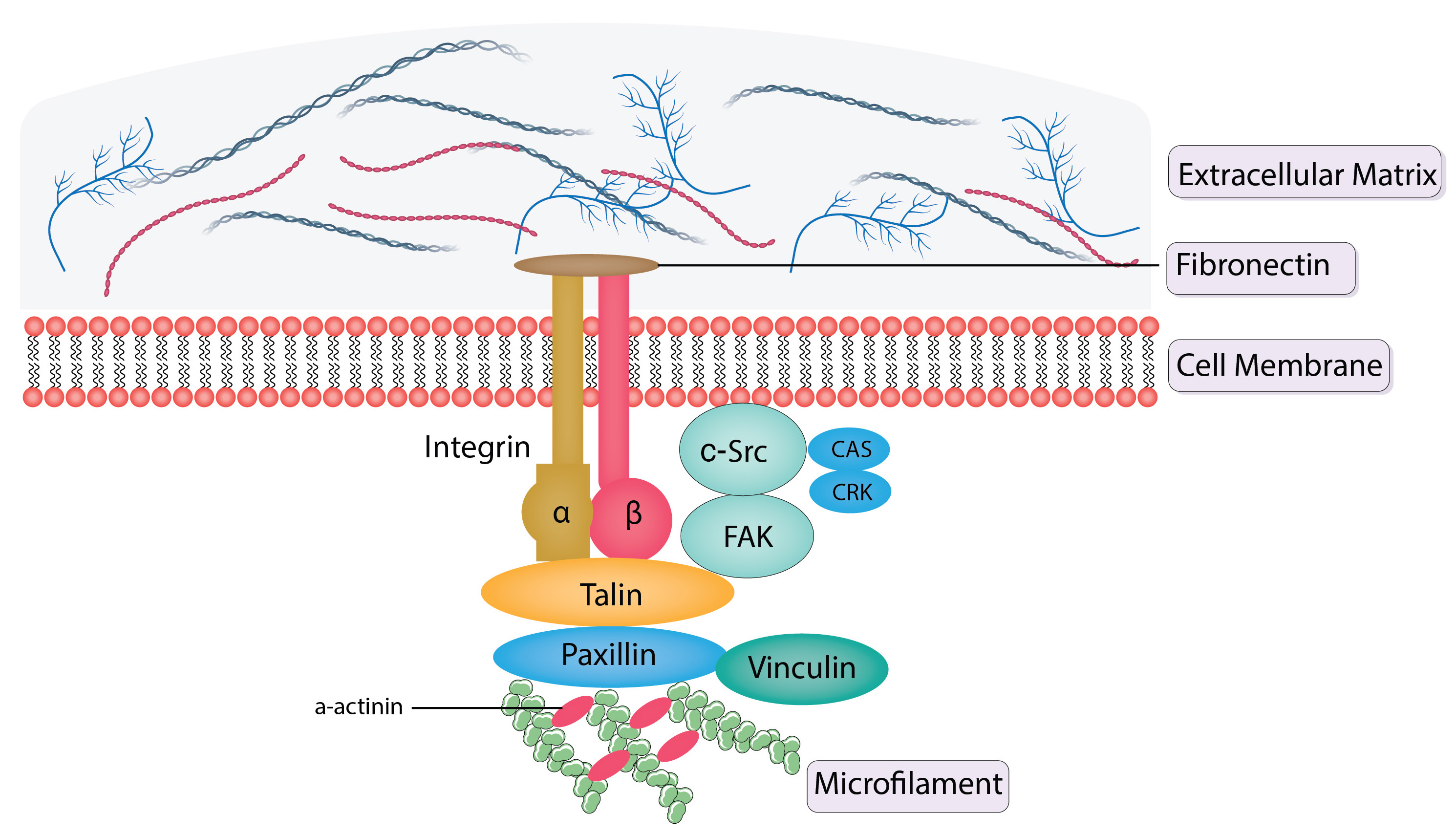

Schematics of structural and signal transduction proteins in focal adhesions are shown in Fig. 3 (Ref. [35, 36, 37, 38, 40, 41, 42, 43]).

Fig. 3.

Fig. 3.

Schematics of structural and signal transduction proteins in

focal adhesions. FAK, integrins, talin, vinculin, and paxillin are structural

proteins that are present in focal adhesions. Integrins are receptors with a

membrane and link the extracellular matrix to the intracellular actin

cytoskeleton.

A class of non-receptor tyrosine kinases called the Src family kinases (SFKs) are activated after integrin signaling. Src is the archetypal SFK and is crucial in controlling the dynamics of focal adhesions. Src is activated by autophosphorylation at particular tyrosine residues, which causes it to move to focal adhesions [44].

Src’s activities are governed by complex regulatory proteins. When phosphorylated at its C-terminal tyrosine (Y527 in human Src), it takes on a closed, inactive shape. Protein tyrosine phosphatases, such as CD45, can dephosphorylate this region, relieving autoinhibition and allowing Src to adopt an open, active conformation [45]. Src activation is additionally promoted by localization at focal adhesions and binding to scaffolding proteins.

Src phosphorylates a range of substrates inside focal adhesions after activation. These include focal adhesion proteins such as cortactin, FAK, and paxillin. Phosphorylation regulates the interactions of these substrates with other proteins, altering the subsequent signaling cascades [46].

The cytoplasmic tyrosine kinase FAK plays a crucial role in focal adhesion signaling, binding with activated integrins [47].

The first step in FAK activation is integrin-mediated clustering and contact with ECM ligands. This results in conformational changes, making it easier for certain tyrosine residues, such as Y397, to be autophosphorylated. SH2 domain-containing proteins, including Src itself, are attached to this autophosphorylation site [48]. Additional tyrosine residues on FAK are phosphorylated by Src to increase its kinase activity and produce docking sites for diverse signaling molecules.

Src, talin, paxillin, and other signaling molecules are among the proteins with which activated FAK forms complexes. The regulation of various cellular functions, including cell proliferation, migration, and survival, is aided by these complexes. Cellular responses to external inputs can be altered by activating downstream signaling pathways such as the Akt and phosphoinositide 3-kinase (PI3K)/mitogen-activated protein kinase (MAPK) pathways [49].

In conclusion, signaling kinases such as Src and FAK interact intricately with integrins, focal adhesion proteins, and focal adhesion signaling pathways. To maintain adequate cellular responses to the extracellular environment, these pathways, which regulate important cellular processes, are strictly regulated by signaling kinase [50]. The importance of comprehending these pathways for potential therapeutic approaches is highlighted by the fact that dysregulation of focal adhesion signaling has been linked to several illnesses.

Src and FAK are important factors that participate in the bidirectional control of focal adhesion signaling, which requires complex crosstalk between numerous signaling proteins. This section explores the functional significance of this crosstalk between Src and FAK within focal adhesions, as well as their reciprocal interactions and regulatory mechanisms.

The activity of Src can be directly influenced by FAK via a number of methods. When FAK is activated at focal adhesions, its SH2 domain recruits and binds Src [51]. This connection causes Src to undergo conformational changes, activating and boosting its kinase activity. Additionally, Src can bind at certain tyrosine residues that are autophosphorylated by FAK, further enhancing Src activation and signaling. By increasing Src activity, FAK aids in the phosphorylation of cytoskeletal and focal adhesion proteins, encouraging cell invasion and migration [44].

FAK can indirectly control Src through the modification of focal adhesion turnover and dynamics in addition to directly activating Src. FAK encourages focal adhesion turnover and disintegration, which causes these sites to release active Src molecules. After being released, Src can participate in signaling cascades in other parts of the cell, having an impact on cellular responses outside of focal adhesions [52].

On the other hand, Src can control FAK by phosphorylating it directly or indirectly through signaling complexes linked to FAK [53]. Src can directly phosphorylate FAK at tyrosine 576 and 577, activating FAK’s kinase activity and enhancing signaling downstream. Additionally, this phosphorylation generates molecular regulators of cellular mechanoadaptation at cell–material interfaces docking sites for other proteins with SH2 domains, enhancing FAK-mediated signaling [50].

Additionally, Src can control FAK indirectly by impacting focal adhesion dynamics. As a result of Src activity’s promotion of focal adhesion turnover, FAK may be released from focal adhesions. When FAK is released, it may undergo further regulatory mechanisms, such as being dephosphorylated by protein phosphatases, which affects the extent to which its kinase activity modulates and how it interacts with other signaling molecules [54].

When Src and FAK interact in focal adhesions, integrated signaling complexes are created that control particular cellular responses [55]. For instance, activated Src and FAK can work together to encourage cell migration by causing changes to the actin cytoskeleton and improving cell motility. These kinases, in conjunction, phosphorylate cytoskeletal proteins such as paxillin and cortactin, thus regulating cell adhesion and motility.

The Src-FAK signaling axis also controls cell survival and proliferation. The activation of Src and FAK triggers the downstream signaling pathways MAPK and PI3K/Akt, which support cell cycle progression, anti-apoptotic signaling, and cell survival [56].

In focal adhesions, Src and FAK form integrated signaling complexes crucial in illnesses, including cancer. Increased cell motility, invasion, and metastasis as a result of dysregulated focal adhesion signaling can aid in the development of tumors [5]. Src and FAK are intriguing targets for cancer therapy due to the abnormal activation of these kinases that have been seen in numerous cancer forms.

In summary, the dynamic regulation of cell proliferation, migration, and survival is influenced by the interaction between Src and FAK within focal adhesions. Focal adhesion signaling is complicated, and its significance in physiological and pathological situations is highlighted by the reciprocal control of these kinases and the development of integrated signaling complexes. Understanding how Src and FAK interact can be very helpful in developing targeted therapeutics for disorders such as cancer that exhibit focal adhesion disruption.

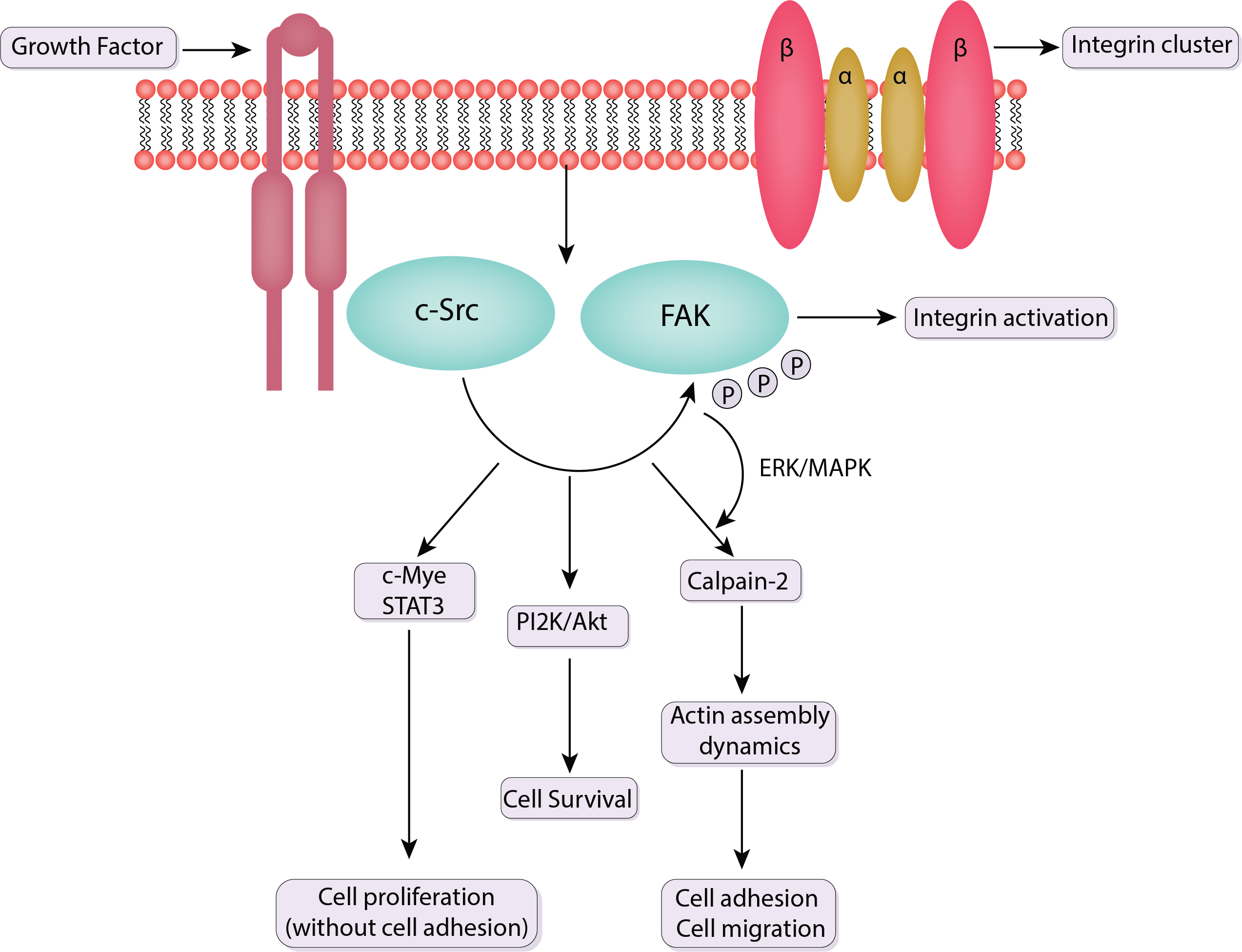

Fundamental biological processes such as cell migration are essential for many physiological processes for instance immunological responses, tissue formation, and wound healing. By serving as mechanosensitive platforms that react to mechanical stimuli from the extracellular environment, focal adhesions play a crucial part in coordinating and controlling cell migration. The discussion in this section emphasizes the dynamics and turnover of focal adhesions, as well as the functions of Src and FAK in cell migration (Fig. 4).

Fig. 4.

Fig. 4.

Schematic of the signaling pathway of FAK and c-Src. Src binds to phosphorylated FAK at Y397. This association activates Src, which then phosphorylates additional tyrosine residues on FAK and other focal adhesion components. Src facilitates the turnover of focal adhesions and actin cytoskeleton remodeling, critical for cell motility. It also regulates the activity of other kinases and adaptor proteins involved in cell migration pathways. The FAK-Src complex activates multiple downstream signaling pathways that coordinate the reorganization of the cytoskeleton and the formation of new focal adhesions. ERK, extracellular signal-regulated kinase; STAT3, signal transducer and activator of transcription 3; PI2K, phosphatidylinositol 2-kinase; MAPK, mitogen-activated protein kinase; c-Src, Cellular Proto-oncogene tyrosine-protein kinase Src; P, phosphoric acid.

Protrusion, adhesion, traction, and retraction are all stages in the cycle of cell migration. Focal adhesions change dynamically during cell migration, allowing cells to bind to the ECM at the leading edge, produce traction forces, and deconstruct adhesions at the trailing edge [57], thus moving them in a directed manner.

New focal adhesions are created at the leading edge when activated integrins interact with ECM ligands. These embryonic adhesions develop into more substantial focal adhesions that facilitate cell spreading and migration, as well as cell-ECM adhesion. At the same time, the actin cytoskeleton changes and produces protrusive forces to push the cell forward [58].

Focused adhesions collapse at the trailing edge, separating the cells from the ECM. Cell retraction is made easier by the coordination of this disintegration process with actomyosin contractility [59]. Src and FAK are just two of the many signaling molecules that work in concert to control how tightly focal adhesion turnover and disassembly are regulated.

Through their participation in focal adhesion dynamics and signaling pathways, Src and FAK both play essential roles in controlling cell migration [60]. By phosphorylating focal adhesion proteins including paxillin and cortactin, which are involved in the control of focal adhesion assembly and disassembly, Src encourages cell migration. Src phosphorylates these proteins, modifying their interactions with other focal adhesion elements, regulating focal adhesion turnover, and facilitating effective cell migration [44].

FAK, a crucial regulator of focal adhesion signaling, influences focal adhesion formation and disassembly to control cell motility. Signaling molecules such as Src and paxillin are attracted to focal adhesions by activated FAK, which promotes their turnover. Additionally, the activation of downstream signaling pathways, such as the PI3K/Akt and MAPK pathways, which aid in cell migration, results from FAK’s localization to focal adhesions [61].

Focal adhesions have a role in collective cell migration, or the coordinated movement of groups of cells, in addition to individual cell migration [62]. In several developmental processes, including tissue repair, regeneration, and embryogenesis, collective cell migration is essential.

Cells interact with one another during collective cell migration through cell-cell junctions and focal adhesions, which transmit signals to nearby cells to regulate their migration. The collective mobility of the cell group is guaranteed by the coordinated activity of focal adhesions in these cells [62].

Overall, through controlling adhesion dynamics, cell-ECM interactions, and intracellular signaling, focal adhesions serve as crucial hubs in cell migration. Src and FAK’s interaction in focal adhesions helps to spatiotemporally regulate focal adhesion turnover and dynamics, which affects cell migration [63]. Since dysregulation of focal adhesion signaling and migration has implications in a wide range of disorders, this field of study has the potential for therapeutic intervention and the development of approaches to regulate cell migration in diseases such as cancer and tissue repair processes.

In addition to regulating cell migration, focal adhesions are essential for controlling cell proliferation and survival. The numerous pathways involved in cell cycle progression, apoptosis, and cell survival are influenced by the dynamic signaling processes at focal adhesions. The role of Src and FAK in cell proliferation and survival is examined in this section, which also examines the contribution of focal adhesions to these processes.

Cell cycle progression has been linked to the control of FAK. By modifying the activity of numerous cells cycle regulatory proteins, activated FAK encourages cell cycle entrance and progression [64]. FAK can activate the MAPK signaling pathway to phosphorylate and activate downstream targets involved in cell cycle control.

Additionally, FAK can directly phosphorylate and activate cyclin-dependent kinase (CDK) inhibitors such as p21 and p27, resulting in nuclear export and destruction. As a result, the cell cycle advances from the G1 to the S phase [65]. The tumor suppressor protein p53 is inhibited by FAK-dependent activation of the PI3K/Akt pathway, which promotes cell cycle progression [66].

Cell proliferation is also influenced by Src activation in focal adhesions. Src can phosphorylate and activate cyclin-dependent kinases (CDKs) and cyclins [67]. This leads to switching from one phase of the cell cycle to another thereby facilitating cell cycle progression and ultimately cell growth.

By phosphorylating CDKs directly or by controlling CDK inhibitors such as p21 and p27, Src can increase the activity of CDKs [68]. Additionally, via controlling the expression of cyclins and other cell cycle regulatory proteins, Src-mediated activation of the MAPK and PI3K/Akt pathways promotes the progression of the cell cycle [69].

Additionally, focal adhesions affect apoptosis (programmed cell death) and cell survival. As excessive adhesion can prevent apoptosis and insufficient adhesion can cause it, balanced focal adhesion signaling is essential for cell survival [70].

It has been demonstrated that FAK increases cell life expectancy by triggering the PI3K/Akt pathway. This pathway prevents apoptosis by controlling the activities of pro- and anti-apoptotic proteins. FAK affects the production of Bcl-2 family proteins, which are essential for controlling apoptosis [71].

Src can control apoptosis by signaling via focal adhesions. In several biological situations, Src activation has been linked to the prevention of apoptosis [44]. Cell survival and resistance to apoptosis-inducing stimuli are promoted by Src-dependent activation of survival pathways, including the MAPK and PI3K/Akt pathways.

Focal adhesion signaling dysregulation affects cell survival and proliferation, which has serious consequences for cancer and other pathological diseases. Abnormal focal adhesion signaling can encourage uncontrolled cell proliferation, aiding in the growth and spread of tumors [72]. Src and FAK are desirable targets for cancer therapy due to their overexpression or hyperactivation in a variety of malignancies [73].

Apoptosis susceptibility or resistance to cell death signals can both be raised by aberrant focal adhesion signaling, which can also disturb cell survival pathways [73]. This imbalance can impair tissue homeostasis, repair mechanisms, and contribute to the emergence of illnesses such as cardiovascular and neurological conditions.

In conclusion, focal adhesions serve a crucial role in regulating cell survival and proliferation through the intricate interaction of the Src and FAK signaling pathways. In order to maintain adequate cellular responses to growth and survival signals, balanced focal adhesion signaling is essential. Since these pathways are dysregulated in many diseases, it is possible to treat cancer and other pathological conditions with targeted medicines that modify focal adhesion signaling.

With their contributions to different physiological processes during embryonic development and adult tissue maintenance, focal adhesions play crucial roles in tissue development and homeostasis. With an emphasis on their functions in embryonic development and tissue maintenance, this section investigates the involvement of focal adhesions in tissue development and homeostasis.

Focal adhesions are essential for cell motility, tissue morphogenesis, and organ creation during embryonic development. Focal adhesion-driven cell migration is crucial for gastrulation, neural crest migration, and the development of different organ systems [74]. Likewise, focal adhesion molecules particularly FAK, integrin, paxillin, and vinculin play an important function in heart formation. Focal adhesion protein assembly, interconnected with the cytoskeletal assembly, is pivotal in cardiomyocyte differentiation. It is also reported that FAK plays an integral role in heart tube looping, an important event during heart formation at embryonic stages. It is also highlighted that the down-regulation of FAK prevented the heart tube looping [75].

Mesenchymal stem cells (MSCs) in bone marrow can differentiate into osteoblasts, chondrocytes, and adipose tissues. FAK plays an important role in bone formation as it is highly activated during the process of differentiation of MSCs in osteoblasts [76].

Focal adhesion signaling is crucial for the direction of cells during migration and tissue formation. Integrin-mediated interactions between cells and the ECM via focal adhesions offer spatial cues that direct cell motion and establish tissue architecture [77]. Cell migration is controlled by the dynamic turnover of focal adhesions, which enables cells to adhere, migrate, and detach as they travel to the correct locations during embryogenesis [78].

Additionally, throughout tissue development, focal adhesions play a role in cell-cell adhesion and communication. They interact with molecules that regulate cell-cell adhesion, such as cadherins to control tissue integrity and organization [79]. For epithelial tissue synthesis and segmentation throughout embryonic development, focal adhesions and adherens junctions must coordinate.

Focal adhesions still play crucial roles in preserving tissue integrity and homeostasis in adult tissues. Focused adhesions are necessary for tissue-specific stem cells to sense and respond to ECM signals, which control their behavior throughout tissue repair and regeneration [80].

Focal adhesions serve as mechanosensors in tissues sensitive to mechanical forces, such as muscle and bone, and convert mechanical impulses into intracellular reactions [81]. Cells can adjust to mechanical stress and preserve tissue integrity through the interaction of focal adhesions with the ECM and subsequent cytoskeletal rearrangements.

Focal adhesion signaling is crucial for tissue homeostasis and the control of cell behavior in response to external signals. Focal adhesions, for example, are essential for regulating keratinocyte adhesion, proliferation, and migration during tissue regeneration and wound healing in the epidermis [82].

Focal adhesion dysregulation can significantly impact tissue pathology and healing. Poor focal adhesion signaling can delay wound healing and decrease tissue regeneration. Conversely, excessive focal adhesion signaling may cause fibrosis and tissue stiffness, which may affect the structure and functionality of the tissue [83].

Aberrant focal adhesion signaling can accelerate disease development in several pathological circumstances. For instance, enhanced focal adhesion signaling may encourage excessive ECM deposition in fibrotic illnesses such as liver or pulmonary fibrosis, which can result in tissue scarring and organ failure [84]. Understanding how focal adhesions affect tissue development and homeostasis will further our understanding of how tissues repair themselves and how different diseases emerge. For treatments in tissue regeneration and disorders linked to focal adhesion dysregulation, focal adhesion signaling may offer an opportunity [85].

In conclusion, focal adhesions play a crucial role in tissue formation and homeostasis by controlling cell migration, tissue morphogenesis, and interactions between cells and the extracellular matrix. They act as mechanosensors, converting mechanical inputs into intracellular reactions that aid in tissue integrity and force adaptation. This field of research is pertinent for therapeutic approaches aimed at boosting tissue regeneration and treating a variety of disorders since dysregulation of focal adhesion signaling can affect tissue repair and pathology [86].

Various diseases and pathological states evolve and grow because of focal adhesion signaling. Focal adhesion signaling dysregulation can cause atypical cellular responses, which aid in the etiology of disease. With an emphasis on cancer, cardiovascular, and neurological disorders, this section investigates the role of focal adhesions in disease and pathology.

Focal adhesions are crucial to the emergence and spread of cancer. Focal adhesions become dysregulated in cancer cells, altering cell-ECM interactions, enhancing cell motility, and increasing the potential for invasion [87]. Abnormal focal adhesion signaling can encourage cancer cells to separate from the main tumor, which then makes it easier for them to intravasate into blood or lymphatic arteries and spread metastatically [88].

The focal adhesion signaling linked to cancer metastasis involves Src and FAK as important participants. Elevated Src activity has been linked to increased cell motility, invasiveness, and resistance to apoptosis, all of which have been observed in various cancer types. Src alters the functions of focal adhesion and cytoskeletal proteins by phosphorylating them, boosting focal adhesion turnover, and encouraging cancer cell motility [89].

Similar to this, FAK overexpression and hyperactivation have been linked to aggressive tumor morphologies and negative clinical outcomes across a variety of cancer types [90]. By improving focal adhesion dynamics and downstream signaling pathways, activated FAK encourages cancer cell survival, migration, and metastasis.

Considering the critical role that focal adhesion signaling plays in the development of cancer, Src, and FAK have emerged as promising therapeutic targets [51]. To decrease focal adhesion signaling and target these kinases, numerous small chemical inhibitors and antibodies have been created [91].

A combination therapy that targets both Src and FAK has demonstrated promise in preventing the invasion, migration, and metastasis of cancer cells. Focusing on focal adhesion signaling not only affects cancer cells directly but may also have an impact on immune cells and fibroblasts that are linked to cancer, as well as other elements of the tumor microenvironment [92].

Focal adhesions also play an important role in cardiovascular disorders such as atherosclerosis, hypertension, and myocardial infarction. Focal adhesions are crucial for preserving the integrity of blood arteries, controlling vascular tone, and allowing endothelial cells to react to shear stress from blood flow [93].

Focal adhesion signaling dysregulation in endothelial cells can degrade the vascular barrier’s performance and cause endothelial dysfunction, which aids in the development of atherosclerotic plaque [94]. Furthermore, changed focal adhesion dynamics in vascular smooth muscle cells can affect artery stiffness and contractility, affecting the control of blood pressure [95].

Focused adhesions are also implicated in several neurological conditions, including brain tumors, neurodegenerative diseases, and neurodevelopmental problems. Neurodevelopmental disorders can result from dysregulated focal adhesion signaling, which impacts the migration of neural cells throughout brain development [96].

Focal adhesions influence brain tumor aggressiveness and treatment resistance which promote tumor cell invasion into surrounding brain tissue. Alterations in focal adhesion signaling have been connected to poor neuronal migration, synapse loss, and compromised blood-brain barrier integrity in neurodegenerative illnesses such as Alzheimer’s and Parkinson’s [5].

Being a link between ECM stimuli and the cytoskeleton of bone cells, focal adhesion is a key player in cell-external environment communication, bone cell adhesion, spreading, migration, and differentiation. MSCs can differentiate into different mesenchymal cell types. FAK promotes differentiation of the mesenchymal cells to bone cells by regulation of MAPK and Wnt signaling pathways and inhibits the mesenchymal differentiation into fat. Focal adhesion proteins are also linked with various skeletal deformities. In osteoarthritis patients, an increase in phosphorylation of FAK and Src was observed in the synovial fluid of joints. Similarly, in samples taken from rheumatoid arthritis patients enhanced expressions of phosphorylated FAK, paxillin, and Src are observed. In blood samples taken from osteosarcoma patients, high levels of FAK and Src associated with uncontrolled cell proliferation are observed. Depending on the disease type, focal adhesion proteins may serve as potential targets for the development of different therapies against different diseases [97].

It is possible to create specialized therapeutic approaches by comprehending the function of focal adhesion signaling in disease etiology [98]. For the treatment of cancer and other disorders characterized by focal adhesion dysregulation, targeting focal adhesions, Src, and FAK, in particular, shows assurance [98].

However, since these structures are crucial for physiological processes in healthy tissues, therapeutic targeting of focal adhesions requires careful attention. The effectiveness of these therapeutic treatments depends on precise targeting techniques that specifically suppress aberrant focal adhesion signaling in disease conditions while maintaining normal tissue function [12].

In summary, focal adhesion signaling plays a role in the pathogenesis of a number of illnesses, including cancer, cardiovascular, and neurological disorders. Understanding the dysregulation of focal adhesions and the kinases that regulate them, Src and FAK, offers important insights into the pathophysiology of disease and suggests possible therapeutic targets [99]. In cancer and other conditions characterized by focal adhesion dysregulation, targeting focal adhesion signaling pathways may present new therapeutic opportunities.

Due to their crucial roles in numerous disorders, therapeutic targeting of focal adhesion signaling pathways, particularly Src and FAK, have drawn a lot of interest. The potential use of small molecule inhibitors, antibodies, and combination therapies to therapeutically target focal adhesion signaling is examined in this section.

Therapies targeting c-Src have received much attention due to their implication in cancer development. Src inhibitors, including dasatinib and bosutinib, have been synthesized and utilized in the hematological amelioration of cancer diseases. It also highlights that these inhibitors are promising mainly in solid tumors, especially when combined with other targeted therapies or chemotherapy drugs. Still, difficulties, including the emergence of resistant forms of cancer and toxic effects on the organism, remain an issue and require further improvement of the approaches based on targeting the Src kinase [51]. The FAK/c-Src complex is a central entity involved in oncogenic signaling. It increases migration invasion capability and protects cancer cells from apoptosis, promoting cancer metastasis and treatment resistance. Both FAK and c-Src kinases are overexpressed in human cancers; therefore, their inhibition might benefit cancer treatment. Inhibition of both kinases simultaneously seems even more effective in preclinical models than individual inhibition of every kinase [6].

To selectively target Src and FAK kinases and interfere with their activity and downstream signaling, small molecule inhibitors have been created. The ATP-binding pocket of the kinases is frequently the target of these inhibitors, which stop ATP binding and subsequent kinase activation.

Several Src inhibitors have been considered as potential cancer treatments in preclinical and clinical trials. Bosutinib, dasatinib, and saracatinib are a few examples. These inhibitors have exhibited promising antitumor activity in a variety of cancer types by effectively blocking Src-driven pathways, such as focal adhesion signaling.

FAK inhibitors, such as defactinib (VS-6063) and bemcentinib (R428), have been developed to target FAK kinase activity. These inhibitors reduce cell migration and survival by disrupting focal adhesion turnover and downstream signaling. FAK inhibitors are being considered as potential cancer and fibrotic illness therapeutics. Caffeic acid phenethyl ester (CAPE) is found in the propolis of honeybees. It has been found that CAPE has anti-inflammatory and anti-cancer potentials. CAPE inhibits phosphorylated FAK and paxillin, promoting increased expression of E-cadherin leading to inhibition of epithelial to mesenchymal transmission (EMT). This ability of CAPE has made it a potential therapeutic agent against cancer [100].

In addition to small molecule inhibitors, antibodies and peptide-based inhibitors targeting focal adhesion components such as integrins and FAK have been produced.

Specific integrin subunit antibodies have been investigated as therapeutic drugs to block integrin-mediated adhesion and focal adhesion signaling. Anti-v3 integrin antibodies, for example, have been studied for their ability to impair tumor angiogenesis and metastasis in cancer.

FAK targeting peptide is used to inhibit FAK signaling. Peptide-based inhibitors that mimic specific protein-protein interaction sites within FAK have been created. These peptides compete with FAK interactions, lowering focal adhesion turnover and downstream signaling.

Due to the complexity of focal adhesion signaling and its crosstalk with other signaling pathways, combination therapies have been investigated to target many components at the same time.

Src and FAK combination therapy: Preclinical investigations have demonstrated that combining Src and FAK inhibitors has synergistic effects. The simultaneous inhibition of Src and FAK impairs focal adhesion signaling and downstream pathways, resulting in improved anti-cancer effects and decreased metastasis. A new method in cancer therapy involves combining focal adhesion targeted medicines with immune checkpoint inhibitors. Since disrupting focal adhesion signaling may affect the tumor microenvironment and boost antitumor immune responses, this combined approach is appealing for cancer treatment.

FAK and c-Src inhibitors are shown in Supplementary Table 1 (FAK inhibitor), and Supplementary Table 2 (c-Src inhibitors).

There are various obstacles to the therapeutic targeting of focal adhesion signaling. Off-target effects and potential toxicity in normal tissues must be thoroughly investigated. Furthermore, cancer cells may resist targeted therapy, necessitating the development of several techniques or the discovery of novel inhibitors.

Future research in this area will most likely concentrate on identifying new targets within the focal adhesion signaling pathway and producing more targeted and effective inhibitors. Understanding the interactions between focal adhesion signaling and other biological pathways will also aid in the development of effective combination medicines.

In summary, therapeutic targeting of focal adhesion signaling, notably Src and FAK, has the potential to treat a variety of diseases such as cancer, fibrotic disorders, and cardiovascular diseases. To disrupt focal adhesion signaling and modify cellular responses in disease contexts, small molecule inhibitors, antibodies, peptides, and combination treatments are being investigated. Future research and clinical trials will help us further understand focal adhesion signaling and its therapeutic potential.

Focal adhesions are multifunctional, dynamic structures that operate as essential regulators of cell-ECM interactions and signaling. Their participation in a variety of cellular activities, such as cell proliferation, migration, survival, and tissue development, emphasizes their critical roles in normal physiological functions. However, disruption of focal adhesion signaling can contribute to the pathophysiology of a variety of illnesses, making them potential therapeutic targets.

This review article delves into a variety of aspects of focal adhesion signaling, with a particular emphasis on the functions of Src and FAK in cell response and disease development. The molecular architecture and composition of focal adhesions, the intricate signaling pathways involving Src and FAK, and their interaction in regulating cellular functions have all been investigated.

The importance of focal adhesions in human health and disease is highlighted by their participation in cancer, neurological and cardiovascular disorders, tissue formation, and tissue homeostasis. Understanding the molecular processes of focal adhesion signaling has led to new treatment approaches.

Preclinical and clinical trials of small molecule inhibitors, antibodies, and peptide-based inhibitors for various disorders have yielded promising results. Complications such as possible toxicities and the emergence of targeted therapy resistance still exist. Combination treatments that combine immune checkpoint inhibitors with drugs that target immune adhesions and different aspects of focal adhesion signaling simultaneously show significant potential for enhancing therapeutic effects.

Future research, in adhesion signaling pathways should focus on exploring targets and understanding its interactions with other cellular pathways. It is also crucial to investigate the role of adhesions in specific disease contexts to develop targeted therapy options.

The field of focal adhesion research presents challenges with implications for human health and disease management. Anticipating advancements in strategies and treatments for diseases is promising as our understanding of focal adhesion signaling deepens. By delving into the intricacies of adhesion signaling, we may pave the way for tailored treatments that can enhance the wellbeing of patients affected by diseases associated with focal adhesions.

KK prepared the figure or conducted the literature search for the manuscript, and wrote the paper. KK has participated sufficiently in the work and agreed to be accountable for all aspects of the work.

Not applicable.

Not applicable.

The work reported here was supported by Promotional Projects for Advanced Education and Research, National University Cooperation Tsukuba University of Technology. The funders had no role in study design, data collection and analysis, decision to publish, or preparation of the manuscript.

The author declares no conflict of interest.

Supplementary material associated with this article can be found, in the online version, at https://doi.org/10.31083/j.fbl2911392.

References

Publisher’s Note: IMR Press stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.