1 Kuwait Cancer Control Centre, Department of Medical Laboratory, Molecular Genetics Laboratory, Ministry of Health, 13001 Shuwaikh, Kuwait

Abstract

Multiple sclerosis (MS) is a complex autoimmune disorder of the central nervous system (CNS) with an unknown etiology and pathophysiology that is not completely understood. Although great strides have been made in developing disease-modifying therapies (DMTs) that have significantly improved the quality of life for MS patients, these treatments do not entirely prevent disease progression or relapse. Identifying the unaddressed pathophysiological aspects of MS and developing targeted therapies to fill in these gaps are essential in providing long-term relief for patients. Recent research has uncovered some aspects of MS that remain outside the scope of available DMTs, and as such, yield only limited benefits. Despite most MS pathophysiology being targeted by DMTs, many patients still experience disease progression or relapse, indicating that a more detailed understanding is necessary. Thus, this literature review seeks to explore the known aspects of MS pathophysiology, identify the gaps in present DMTs, and explain why current treatments cannot entirely arrest MS progression.

Keywords

- multiple sclerosis (MS)

- experimental autoimmune encephalomyelitis

- MS therapies

- MS pathogenesis

- immune system

- neurodegenerative disorder

Multiple sclerosis (MS) is a multifactorial disease that affects the central nervous system (CNS) and is believed to be caused by dysfunction of the immune system [1]. In 2023, more than 2.9 million people worldwide had MS [2].

MS can severely impact neurological function, causing varied symptoms. During remission, some show recovery, but chronic disabilities often become irreversible due to axonal loss [1, 3]. There are four main subtypes: relapsing-remitting MS (RRMS) (most common with unpredictable relapses/remissions), primary-progressive MS (PPMS) (steady disability without relapses), secondary-progressive MS (SPMS) (progressive decline after RRMS), and progressive-relapsing MS (PRMS) (disability plus relapses). Clinically isolated syndrome (CIS) involves a first episode of MS-like CNS symptoms [1, 3].

Despite ongoing research, the etiology of MS remains unclear. However, multiple factors such as genetics, environmental conditions, and infections are associated with development of the disease [1]. Effective disease treatment hinges on a comprehensive understanding of its pathophysiology. To date, research into the pathophysiology of MS has been extensive; however, a complete understanding of this complex process is lacking [3]. While initial theories suggested that MS resulted from a viral infection of the CNS, subsequent research shifted the perspective towards an autoimmune pathway as the primary cause of the disease [4]. Since then, our understanding of the disease has become much clearer, although more work is still needed to fully elucidate the underlying mechanisms [3].

MS is an incurable disease; however, since the introduction of interferon (IFN) in 1993, there has been a significant increase in the number of treatment options available to MS patients [5]. Currently, there are more than 19 United States Food and Drug Administration (FDA)- and European Medicines Agency (EMA)-approved disease modifying therapies (DMTs) available to treat patients with MS, each targeting specific immunological mechanisms (Tables 1,2,3,4) [6, 7]. However, the existence of multiple DMTs for MS treatment, coupled with variations in international guidelines, has led to inconsistent decision-making across clinics, raising concern and requiring attention [7, 8, 9, 10].

| Type | Drug name | Brand name | Mechanism of action | Method of administration | Approval year (FDA) | Approval year (EMA) | Approved for | Contraindications | Efficacy | Adverse effect |

| Monoclonal antibodies | Mitoxantrone | Novantrone | Synthetic antineoplastic anthracenedione | Intravenous | 2000 | 1998 | SPMS | Hypersensitivity reactions to mitoxantrone. | Reduces relapses, progression, and lesions in MS. | Myelosuppression, congestive heart failure, AML, serious skin damage (necrosis). |

| PRMS | ||||||||||

| Worsening RRMS & | ||||||||||

| Natalizumab | Tysabri | anti- |

Intravenous | 2004 | 2006 | Relapsing forms of MS | Hypersensitivity reactions to natalizumab, patients who have or had PML, immunocomprimised patients, it should not be administrated with immunoregulatory agents. | Reduce clinical relapses by 67%, new brain MRI lesions by 83%, and disability progression by 42%. | Bladder/urinary issues, skin reactions, respiratory symptoms, cardiovascular problems, genital/vaginal irritation, swelling (face, eyes, lips), fatigue and weakness. | |

| Alemtuzumab | Lemtrada | Anti-CD52 | Intravenous | 2014 | 2013 | Relapsing forms of MS | Hypersensitivity reactions to alemtuzumab, HIV infection, active infection, uncontrolled hypertension, history of arterial dissection of the cervicocephalic arteries, history of strokc, history of angina pectoris or myocardic infraction, coagulopathy, on anti-platelets or anti-coagulant therapy, other concomitant autoimmune disease. | Reduce ARR (49%–55%), reduce MRI lesions (old 61%–63%, new: 17%–32%), and EDSS score (27%– 42%). | Acquired haemophilia A, ITP, TTP, kidney, thyroid, red and white blood cells (RBC & WBC) disorders, autoimmune encephalitis. | |

| Daclizumab | Zinbryta | Anti-CD25 | Subcutaneous injection | 2016 | 2016 | Relapsing forms of MS | Hypersensitivity reactions to daclizumab, hepatic disease or hepatic impairment, history of autoimmune hepatitis or other autoimmune condition involving the liver. | Significant ARR reduction (54%), reductions in new lesions (69%–78%). | Liver problems (including autoimmune-related liver problems), immune-system problems (immune-mediated disorders). | |

| Ocrelizumab | Ocrevus | Anti-CD20 | Intravenous | 2017 | 2018 | Relapsing forms of MS, early PPMS | Hypersensitivity reactions to ocrelizumab, active hepatitis-B infection. | Reduce ARR (46%), reduce MRI lesions (old: 94%, new: 77%–83%) and EDSS score (40%). | Back pain, depression, herpes virus-associated infections, infusion reactions, lower respiratory infections, pain in extremities, upper respiratory infections, cough, diarrhea, edema peripheral, skin reaction. | |

| Ofatumumab | Kesimpta | Anti-CD20 | Subcutaneous injection | 2020 | 2021 | Relapsing forms of MS | Hypersensitivity reactions to ofatumumab, hepatitis-B infection, active infection. | Reduce relapses (44%), reduces MRI lesions (old: 96.4%, new: 82.7%), and reduce disability worsening events (21.6%). | Upper respiratory infections, injection-related reaction, skin reaction, urinary tract infections, decrease in IgM levels, oral herpes. |

FDA, Food and Drug Administration; EMA, European Medicines Agency; EDSS, expanded disability status scale; AML, acute myeloid leukemia; HIV, human immunodeficiency virus; ITP, immune thrombocytopenic purpura; TTP, thrombotic thrombocytopenic purpura; DMTs, disease-modifying therapies; MS, multiple sclerosis; SPMS, secondary-progressive MS; PRMS, progressive-relapsing MS; RRMS, relapsing-remitting MS; PPMS, primary-progressive MS; MRI, magnetic resonance imaging; PML, progressive multifocal leukoencephalopathy; ARR, annualized relapse rates; CD52, cluster of differentiation 52; IgM, immunoglobulin M. & patients whose neurologic status is significantly abnormal between relapses.

| Type | Drug name | Brand name | Mechanism of action | Method of administration | Approval year (FDA) | Approval year (EMA) | Approved for | Contraindications | Efficacy | Adverse effect |

| S1PR modulator | Fingolimod | Gilenya | S1P1,3,4,5R modulator | Oral | 2010 | 2011 | Relapsing forms of MS | Hypersensitivity reactions to fingolimod, cardiovascular events or problems (including; recent myocardial infarction, unstable angina, stroke, transient ischemic attack, AV block, cardiac arrhythmias, etc.). | Reduce relapses (54% reduction in ARR) and slow disability worsening. | Cardiac and macular effects, posterior reversible encephalopathy syndrome, liver damage, breathing problems, severse worsening of MS after discontinuation of fingolimod, increase blood pressure, Basel cell carcinoma and melanoma, allergic reaction. |

| Siponimod | Mayzent | S1P1,5R modulator | Oral | 2019 | 2020 | Relapsing forms of MS, active SPMS | Hypersensitivity reactions to siponimod or any of its ingredients, immunodeficiency syndrome, PML or cryptococcal meningitis, active cancer, severe liver problems, heart problems, pregnant or planning for pregnancy. | Reduce ARR (52%), total (58.1%) and regional (58.3%–85.4%) brain atrophy, and confirmed disability progression (22%). | Skin reaction, basel cell carcinoma, lymphopenia, convulsions, macular oedema, atrioventricular block, bradcardia, squamous cell carcinoma. | |

| Ozanimod | Zeposia | S1P1,5R modulator | Oral | 2020 | 2020 | RRMS, active SPMS, CIS | Hypersensitivity reactions to ozanimod or any of its ingredients, immunodeficiency, heart problems, severe infection, cancer, liver problem, pregnancy or planning for pregnancy. | Reduce ARR (38%–48%), reduce MRI lesions (old: 53%–63%, new: 42%–48%), and EDSS score (6 months: 8.6%). | Heart problems, urinary track infection, increase in blood pressure, skin reaction, PML (rare). | |

| Ponesimod | Ponvory | S1P1R modulator | Oral | 2021 | 2021 | RRMS, active SPMS, CIS | Hypersensitivity reactions to ponesimod or any of its ingredients, immunodeficiency, heart problems, severe infection, cancer, liver problem, pregnancy or planning for pregnancy. | Reduce ARR (31%), reduce MRI lesions (56%), and EDSS score (17%). | Urinary tract infection, bronchitis, viral infections, herpes zoster viral infection, pnemonia, vertigo, pyrexia, macular oedema, seizures, bradcardia. |

FDA, Food and Drug Administration; EMA, European Medicines Agency; S1PR, sphingosine 1-phosphate receptor; EDSS, expanded disability status scale; AV, atrioventricular; CIS, clinically isolated syndrome.

| Type | Drug name | Brand name | Mechanism of action | Method of administration | Approval year (FDA) | Approval year (EMA) | Approved for | Contraindications | Efficacy | Adverse effect |

| Interfere with DNA replication and repair | Teriflunomide | Aubagio | Pyrimidine synthesis inhibitor | Oral | 2012 | 2013 | RRMS | Hypersensitivity reactions to teriflunomide or any of its ingredients, severe hepatic impairment, immunodeficiency, pregnancy or planning for pregnancy, breast-feeding, impaired bone marrow function, active infection, renal problems, severe hypoproteinaemia. | Reduce ARR (31%), reduce MRI lesions (old: 57%, new: 44%) and EDSS score (20%). | Pancreatic inflammation, allergic reaction, skin reaction, severe infection or sepsis, lung inflammation, transaminitis, teratogenicity, neuropathy, hypertension. |

| Cladribine | Mavenclad | Purine antimetabolite | Oral | 2019 | 2017 | Relapsing forms of MS | Hypersensitivity reactions to cladribine or any of its ingredients, HIV infection, active tuberculosis, hepatitis, immunodeficiency or taking immunosuppression medication, active cancer, moderate or severe kidney problems, pregnancy or planning for pregnancy, breast-feeding. | Reduce ARR (55%–58%), reduce MRI lesions (old: 86%, new: 73%), and EDSS score (47%). | Lymphopenia, shingles, liver problems, skin reaction, allergic reaction, hair loss, tuberculosis (rare). |

FDA, Food and Drug Administration; EMA, European Medicines Agency; EDSS, expanded disability status scale; HIV, human immunodeficiency virus.

| Type | Drug name | Brand name | Mechanism of action | Method of administration | Approval year (FDA) | Approval year (EMA) | Approved for | Contraindications | Efficacy | Adverse effect |

| Unknown | IFN |

Betaferon | Unknown | Subcutaneous injection | 1993 | 1995 | RRMS, active SPMS, CIS | Hypersensitivity reactions to IFN |

Reduce ARR (34%), reduce MRI lesions (old: 83%, new: 75%), and EDSS score (29%). | Skin reaction, allergic reaction, depression or suicidal ideation, excssive bleeding after injury, infections, GI problems, heart problems. |

| Extavia | 2009 | 2008 | Hypersensitivity reactions to IFN |

Skin reaction, lymphopenia, flu-like symptoms, myalgia, leukopenia, neutropenia, increased liver enzymes, headache, hypertonia, pain, insomnia, abdominal pain, asthenia. | ||||||

| IFN |

Avonex | Unknown | Intramuscular injection | 1996 | 1997 | RRMS, SPMS | Hypersensitivity reactions to IFN |

Reduce ARR (low dose: 29%, high dose: 32%), reduce | Allergic reaction. | |

| MRI lesions (old-low dose: 22%, old-high dose: 67%, new-low dose: 67%, new-high dose:78%), and EDSS score (low doe: 32%, high dose: 28%). | Depression. | |||||||||

| Liver problems. | ||||||||||

| Rebif | Subcutaneous injection | 1998 | 1998 | RRMS, active SPMS, CIS | Hypersensitivity reactions to IFN |

Allergic reaction, depression. | ||||

| Liver problems, skin reaction, flu-like symptoms, thyroid dysfunction, MS pseudo-relapse, GI problems, headache. | ||||||||||

| DMF | Tecfidera | Unknown | Oral | 2013 | 2014 | RRMS | Hypersensitivity reactions to DMF or any of its ingredients. | Reduce ARR (44%–53%), reduce MRI lesions (old: 74%–90%, new: 71%–85%), and | Lymphopenia, PML, allergic reaction, GI problems, skin reaction, hair loss. | |

| Generics | 2020 | 2021 | Suspection or confirmed PML. | EDSS score (38%). | ||||||

| MMF | Bafiertam | Unknown | Oral | 2013 | - | RRMS, active SPMS, CIS | Hypersensitivity reactions to MMF or any of its ingredients, liver problems, lymphopenia, active infection, pregnancy or planning for pregnancy. | - | Allergic reaction, PML, herpes zoster infection, lymphopenia, liver problem, skin reaction, GI problems. | |

| DRF | Vumerity | Unknown | Oral | 2013 | 2021 | RRMS | Hypersensitivity reactions to DRF or any of its ingredients, PML, severe liver disease, severe kidney disease, serious infection, GI disease. | Reduce ARR and reduce MRI old lesions (77%). | Allergic reaction, PML, skin reaction, GI problems, lymphopenia, pneumonia. | |

| GA | Copaxone | Unknown | Subcutaneous injection | 1996 | 2004 | RRMS, active SPMS, CIS | Hypersensitivity reactions to GA or any of its ingredients. | Reduce ARR (29%). | Skin reaction, vasodilution, dyspnea, chest pain. | |

| Glatopa (US) | 2015 | ? | ||||||||

| Generic | 2017 | 2016 | ||||||||

| Pegylated IFN |

Plegridy | Unknown | Intramuscular injection | 2021 | 2020 | RRMS | Hypersensitivity reactions to Pegylated IFN |

Reduce ARR (27%), MRI lesions (old: 86%, new: 67%), and EDSS score (38%). | Liver problems, depression, allergic reaction, seizures, skin reaction, kidney problems, blood problems, flu-like symptoms, myalgia, arthraglia, asthenia. |

FDA, Food and Drug Administration; EMA, European Medicines Agency; IFN

While current DMTs have significantly enhanced the quality of life for MS patients, unaddressed aspects remain unaddressed for the complete prevention of disease progression or relapse. Thus, developing targeted therapies thus necessitates a thorough understanding of the disease’s pathophysiology and the identification of areas that current DMTs fail to address. This review examines the pathophysiology of MS and provides an overview of current DMTs that target each stage of disease development. Furthermore, it sheds light on those aspects of MS pathophysiology that existing DMTs still do not properly address. In doing so, the review explains the gaps and limitations in the studies on the efficacy of DMT for MS. While most steps of MS pathological development are targeted by current DMTs, this review will explain why disease progression and relapse often cannot be halted despite such treatment measures.

Although there is no cure for MS, various DMTs are available that can help reduce clinical and subclinical disease activity, slow disease progression, and delay disease development. Currently, DMTs are approved to treat CIS, RRMS, SPMS, and PPMS [11].

DMTs can be categorized into four groups according to their mechanism of action:

monoclonal antibodies such as mitoxantrone, natalizumab, alemtuzumab, daclizumab,

ocrelizumab, and ofatumumab; sphingosine 1-phosphate receptor (S1PR) modulators

including fingolimod, siponimod, ozanimod, and ponesimod; DNA replication and

repair interfering agents such as teriflunomide and cladribine; and agents with

an unknown mechanism of action, including interferon-beta (IFN

2.2.1.1 Natalizumab

Natalizumab works by blocking the interaction between the

However, there is an important association between natalizumab use and a

heightened risk of progressive multifocal leukoencephalopathy (PML), a rare

demyelinating condition triggered by the John Cunningham virus (JCV) [6, 11, 15].

While JCV is common and generally asymptomatic, it can reactivate in individuals

with weakened immune systems [6, 11, 15]. It has been proposed that the increase in

circulating hematopoietic precursors and the buildup of pre-B and B cells due to

natalizumab may help JCV transition from its latent state to a more virulent

form, which can enhance viral activity and replication within lymphoid tissues

[6, 11, 15]. Key risk factors for developing PML during treatment with natalizumab

include prolonged therapy (

2.2.1.2 Ofatumumab

Ofatumumab is a monoclonal antibody designed to target the cluster of differentiation (CD20) protein found on the surface of B lymphocytes, although its precise mechanism of action remains unclear [6, 11, 16]. The fragment antigen-binding (Fab) region of ofatumumab specifically attaches to CD20, which leads to a depletion in B cell populations, and possibly T cell reduction as well, through two primary pathways [16]. One pathway is complement-dependent cytotoxicity (CDC), where the binding of ofatumumab activates the complement system, leading to the destruction of B cells that express CD20. Alternatively, binding can trigger antibody-dependent cell-mediated cytotoxicity (ADCC), in which effector cells, such as natural killer (NK) cells, identify and eliminate the antibody-labeled B cells [16]. This dual mechanism highlights the role of ofatumumab in modulating immune responses by targeting B cells directly [6, 11, 16] (Table 1).

2.2.1.3 Ocrelizumab

Ocrelizumab is a humanized monoclonal antibody that, similar to ofatumumab, specifically targets the CD20 protein on B cells [6, 11, 17]. By binding to this protein, ocrelizumab facilitates the depletion of B cells that express CD20 [6, 11, 17]. However, unlike some therapies that aim to deplete B cells, ocrelizumab is formulated to allow preservation of the body’s ability to regenerate B cells and maintain existing humoral immunity [17].

This means that although ocrelizumab effectively reduces the number of circulating B cells, it does not completely eradicate them. This strategy enables the eventual repopulation of B cells and conservation of the body’s existing antibody-mediated immune functions. The selective approach to B cell depletion, combined with the maintenance of B cell reconstitution and humoral immunity, is believed to enhance the therapeutic effectiveness and improve the safety profile of ocrelizumab in treating a range of diseases associated with B cell activity [17] (Table 1).

2.2.1.4 Alemtuzumab

Alemtuzumab is a humanized monoclonal immunoglobulin G 1 (IgG1) antibody that targets the cluster of differentiation 52 (CD52) protein [6, 11, 18, 19]. CD52 is a glycosylphosphatidylinositol-anchored protein expressed at high levels on T and B lymphocytes, and to a lesser extent on monocytes, macrophages, and eosinophils. It is minimally expressed on NK cells, plasma cells, neutrophils, and hematopoietic stem cells [18, 19].

The binding of alemtuzumab to CD52 leads to the depletion of CD52-positive cells through two main mechanisms: ADCC (in animal models, this appears to be the predominant mechanism) and CDC of CD52-positive cells. The depletion of CD52-high CD4+ T cells may be particularly important in the development of secondary autoimmune conditions that can occur after alemtuzumab treatment, as these cells play a crucial role in regulating the immune response [18, 19]. The exact physiological function of CD52 is still not fully understood, but it has been implicated in the activation and migration of T lymphocytes, despite the lack of intracellular domains [18, 19] (Table 1).

Sphingosine-1-phosphate receptors (S1PRs) are a family of five distinct G protein-coupled cell surface receptors [6, 11, 20]. Among them, S1P1R plays a crucial role in various physiological processes including angiogenesis, neurogenesis, immune cell trafficking, endothelial barrier function, and vascular tone. S1P1R mediates the responsiveness of lymphocytes to the S1P chemotactic gradient, allowing them to traffic between secondary lymphoid tissues and efferent lymphatics [6, 11, 20]. Blocking S1P1R function leads to the sequestration of lymphocytes in the lymph nodes and thymus. S1P1R is also expressed on endothelial cells, where it regulates dendritic cell (DC) recruitment and vascular permeability [6, 11, 20]. In animal models, inhibiting S1P1R suppresses cytokine amplification and immune cell recruitment, which is the primary therapeutic target in MS treatment [6, 11, 20]. Moreover, the expression of S1PRs on various CNS cell populations suggests that their direct effects on the CNS may contribute to the therapeutic benefits observed. In the experimental autoimmune encephalomyelitis (EAE), MS mouse model, blockade of S1P1R enhances neuronal survival and inhibits gliosis and demyelination. The clinically relevant functions of the other S1PR subtypes (S1P2R, S1P3R, S1P4R, and S1P5R) are less well-established compared to S1P1R [20] (Table 2).

2.2.2.1 Fingolimod

Fingolimod, which targets S1P1R, S1P3R, S1P4R, S1P5R, was the first S1P1R modulator approved for clinical use [6, 11, 20]. It works by binding to S1P1R on lymphocytes, leading to receptor internalization and loss of responsiveness to the S1P gradient that drives lymphocyte migration from lymph nodes [6, 11, 20]. This reduces the number of circulating inflammatory cells, limiting their entry into the CNS. Beyond this systemic immunological effect, fingolimod may also stabilize the blood-brain barrier (BBB) and exert direct effects on CNS cells, such as reduced astrogliosis, axonal loss, and demyelination, in EAE models [6, 11, 20] (Table 2).

2.2.2.2 Siponimod, Ozanimod, and Ponesimod

Subsequently developed S1PR modulators, such as siponimod, ozanimod, and ponesimod, are more specific in targeting only S1P1, 5Rs or S1P1R, with the aim of maintaining efficacy while potentially reducing adverse effects [6, 11, 20]. All S1PR modulators are believed to have a similar impact on lymphocyte trafficking, but their direct CNS effects may vary and are not yet fully understood, particularly for S1P5R-mediated mechanisms [6, 11, 20] (Table 2).

2.2.3.1 Teriflunomide

Teriflunomide mechanism of action in MS is hypothesized to relate to its effects on the proliferation of stimulated lymphocytes [6, 11, 21]. During the cell cycle, lymphocytes undergo division, which involves an S phase (DNA synthesis) and M phase (cell division), separated by G phases. DNA synthesis in the S phase requires the provision of new building blocks, including pyrimidine and purine bases. Teriflunomide blocks de novo pyrimidine synthesis by specifically and reversibly inhibiting the mitochondrial enzyme dihydro-orotate dehydrogenase (DHODH), which is expressed at high levels in proliferating lymphocytes [21]. This teriflunomide-mediated blockade of pyrimidine synthesis interrupts the cell cycle in the S phase, exerting a cytostatic effects on the proliferation of T and B cells, thereby limiting their involvement in the inflammatory processes underlying the pathogenesis of MS [21] (Table 3).

Teriflunomide selectively inhibits rapidly proliferating, activated lymphocytes. Resting lymphocytes can undergo homeostatic proliferation using the salvage pathway, bypassing the DHODH enzyme targeted by teriflunomide [21]. This selective targeting allows teriflunomide to inhibit the hyperactive, proliferating lymphocytes involved in MS, without affecting other proliferating cell types such as gastrointestinal (GI) mucosal cells that express lower DHODH levels and do not display the same rapid expansion [21] (Table 3).

2.2.3.2 Cladribine

Cladribine is a nucleoside analog resistant to adenosine deaminase, allowing its accumulation in cells [6, 11, 22]. Phosphorylation of cladribine to its active triphosphate form (2-CdATP) impairs both nucleic acid synthesis and repair [22]. Cladribine also inhibits ribonucleotide reductase, further disrupting nucleotide synthesis [22]. These combined effects are predicted to induce apoptotic cell death, particularly in lymphocytes that rely on both de novo and salvage nucleotide pathways for DNA replication during clonal expansion [22]. The slow depletion of lymphocytes observed with therapeutic doses of cladribine suggests that it affects both resting and dividing cells, although the precise mode of action in MS is not fully understood [22] (Table 3).

2.2.4.1 IFN

IFN

2.2.4.2 DMF

DMF modifies a variety of proteins involved in T-cell activation through its electrophilic activity [6, 11, 24]. Additionally, DMF reduces the production of nitric oxide synthase and pro-inflammatory cytokines [24]. Beyond modulating T-cell function, DMF also affects the survival of immune cells themselves. This impact on cell survival is likely the underlying cause of the high incidence of lymphopenia associated with DMF treatment [24] (Table 4).

2.2.4.3 MMF

MMF is the active metabolite of DMF. MMF is believed to exert its therapeutic effects through activation of nuclear factor erythroid 2-related factor 2 (Nrf2) and nuclear factor kappa B (NF-kB) pathways, reducing oxidative stress and inflammation [25]. Specifically, Nrf2 activation by MMF provides cytoprotection in astrocytes, while MMF also decreases adhesion molecule expression, reducing monocyte migration across the BBB [25]. Additionally, MMF can modulate the immune response by impairing DC maturation and T cell activation [25]. Furthermore, Nrf2 activation by MMF has demonstrated neuroprotective effects on animal models of ischemia-reperfusion injury [25]. However, the precise mechanisms of action of DMF and its metabolite MMF in MS are not fully understood [6, 11, 25] (Table 4).

2.2.4.4 DRF

DRF is an oral fumarate approved for RRMS [6, 11, 26]. Similar to DMF, DRF is converted to the active metabolite MMF [6, 11, 26]. DMF has demonstrated efficacy in MS, but commonly causes GI adverse events in up to 40% of patients. By contrast, DRF has shown improved GI tolerability compared to DMF [6, 11, 26]. This may be due to the different chemical structure of DRF, resulting in lower production of the irritating metabolite methanol, as well as fewer off-target interactions. The better GI tolerability profile of DRF provides an alternative treatment option for RRMS patients unable to tolerate the GI side effects of DMF [11, 26] (Table 4).

2.2.4.5 GA

GA has several proposed mechanisms of action. One mechanism is binding to major

histocompatibility complex (MHC) class II molecules on antigen-presenting cells

(APCs), preventing stimulation of myelin basic protein (MBP)-specific cells.

Another mechanism is shifting the immune response from a pro-inflammatory to an

anti-inflammatory pattern. GA inhibits the secretion of pro-inflammatory

cytokines (interleukin 2 [IL-2], IL-12, IFN

Each DMT offers unique benefits along with safety concerns and substantial

costs, providing vital treatment prospects for people with MS [11, 14]. For

example, IFN

Understanding the pathophysiology of MS is crucial for determining the most suitable treatment for patients. MS begins with an immune response triggered by various unknown factors such as viruses, environmental factors, and genetics predisposing susceptibility factors [1, 41]. Several viruses have been linked to MS, with Epstein-Barr virus (EBV) playing a particularly important role. The significance of EBV concerning disease susceptibility is well known [42]. EBV infiltrates the brain through B cells and establishes chronic infection, leading to periodic reactivation and inflammatory responses. The presence of memory B cells and the similarity between EBV and MBP epitopes can trigger autoimmune reactions against the myelin sheath, causing axonal demyelination [42]. Additionally, EBV expresses an abnormal autoantigen found in the brains of MS patients [42].

The environmental factors that have garnered significant attention regarding their impact on MS include vitamin D levels, obesity, cigarette smoking, and gut microbiomes [43, 44, 45, 46, 47]. Research indicates a strong connection between vitamin D deficiency and both the onset and progression of MS, with even baseline levels of vitamin D even influencing disease activity. Individuals with a genetic tendency for higher vitamin D levels tend to have a reduced risk and later onset of disease [43, 44].

Additionally, a link has been identified between obesity in early life and an increased risk of developing MS, regardless of other influencing factors [45]. Cigarette smoking also appears to contribute to the progression of MS, although the precise mechanisms underlying this relationship remain unknown, leading to ongoing disagreements among researchers regarding its effects across different populations [46].

Moreover, the gut microbiome is increasingly recognized as an important factor in the pathogenesis of MS. Research has demonstrated that the intestinal microbiome can influence the development of CNS-reactive T cells and modulate the function of CNS-resident cells. Notably, transplantation of gut microbiota from MS patients can exacerbate EAE [47]. Investigations into the gut microbiome of individuals with MS have revealed changes that relate to both pro-inflammatory and anti-inflammatory responses [47].

Several genetic factors have been linked to the risk of developing MS, with the human leukocyte antigen (HLA)-DRB1*15:01 allele being the most significant, although it explains less than half of the genetic predisposition to the disease [1, 48, 49]. In addition to this allele, other regions within the HLA complex, as well as some non-HLA regions, have also been closely associated with MS risk [1, 48, 49]. Genome-wide association studies and linkage analyses have uncovered numerous genetic loci related to the immune, nervous, and hemostatic systems that contribute to susceptibility to MS. Furthermore, various epigenetic mechanisms, such as DNA methylation, histone modification, and mRNA methylation, are believed to play a role in the progression and development of MS [1, 48, 49].

MS is a complex autoimmune disease primarily affecting the CNS. The CNS is an immune-privileged site, with the BBB selectively regulating the entry of molecules and cells. In MS, this immune privilege is disrupted, leading to the undesirable activation of antigen-specific T and B cells. This triggers a cascade of self-damaging processes, resulting in CNS inflammation, demyelination, axonal damage, and neurodegeneration [1, 3, 48]. The exact mechanisms behind T– cell activation in MS are not fully understood, but one theory suggests peripheral T– cell activation, followed by their re-circulation into the CNS driven by the S1P gradient. The approved MS drug fingolimod exerts its action by blocking the S1P1R, supporting the importance of this pathway in disease activation [1, 3, 29, 48].

Once in the CNS, activated T cells release immunoregulatory molecules, leading

to demyelination through various hypothesized processes, such as

receptor-mediated phagocytosis of myelin, myelin stripping, vesicular disruption

of myelin sheaths, and oligodendrogliopathy [1, 3, 48, 50, 51]. During active stages

of MS, oligodendrocytes are dramatically lost due to immune-mediated mechanisms,

but large numbers of undifferentiated oligodendrocyte progenitor cells (OPCs) are

recruited to the site of lesions [1, 3, 48, 50]. In some cases, severe demyelination

may occur with complete loss of oligodendrocytes and lack of remyelination, which

may result from pathological mechanisms that effectively destroy all

oligodendrocytes and their progenitors, or from antigen-mediated immune responses

against these cells [1, 3, 48, 50]. In cases of attempted remyelination, some

stressed oligodendrocytes may be at risk of destruction, potentially driven by

gamma-delta (

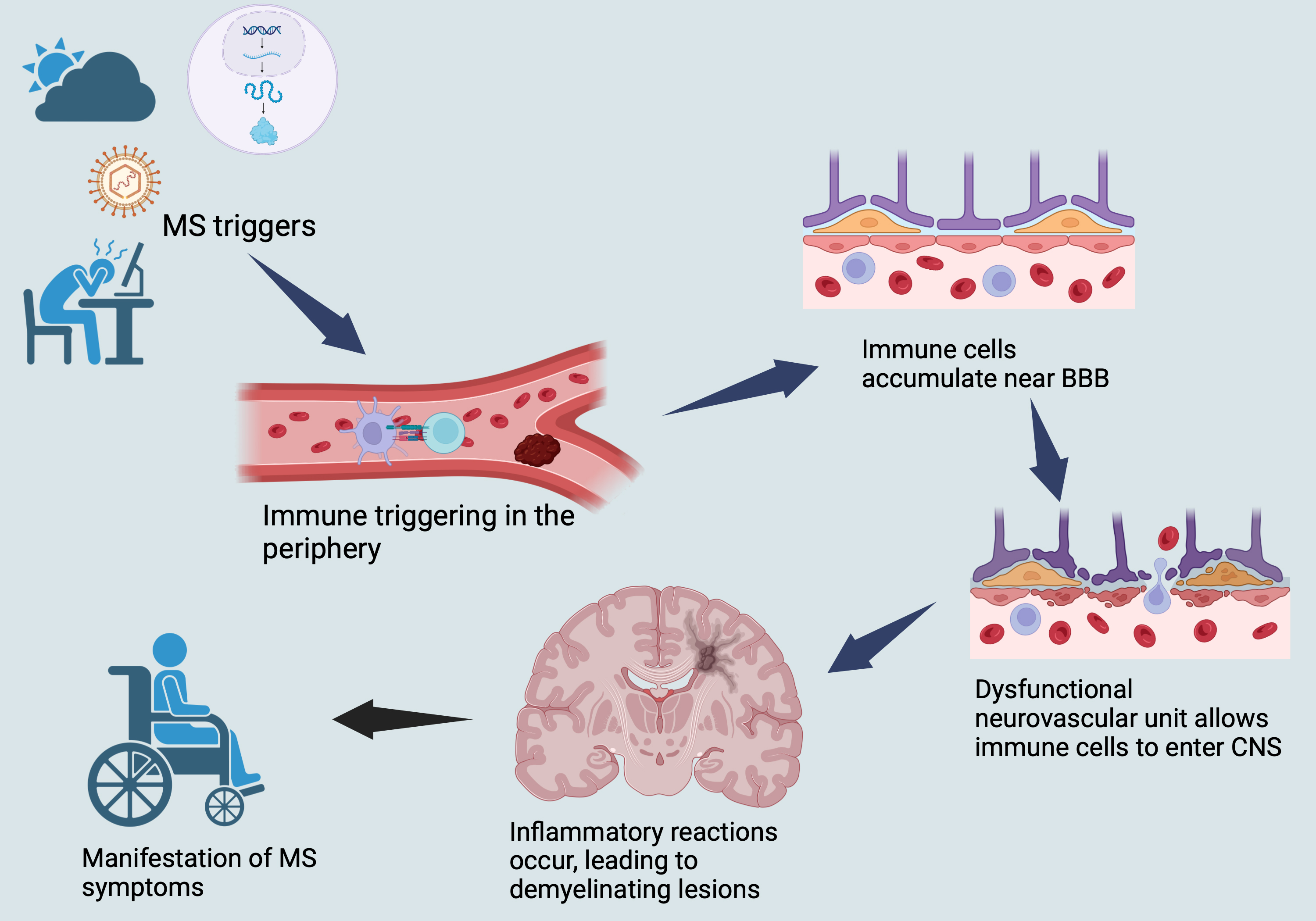

The disease course of MS typically involves episodic, relapsing-remitting phases driven by inflammation, followed by progressive phases characterized by demyelination and axonal loss (neurodegeneration) [1, 48, 50]. Understanding the complex interplay between these two underlying mechanisms is crucial for developing effective treatments for this debilitating disease (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1.

Fig. 1.

Illustrates a brief overview of MS pathophysiology. MS, multiple sclerosis; CNS, central nervous system; BBB, blood-brain barrier.

The initiation of inflammatory events in MS is thought to occur in the periphery with the activation of T and B cells, which are subsequently transferred to the CNS [1, 48, 50].

The development of MS involves the activation of immune cells located in the

periphery by APCs. When the self-antigens are presented, such activation results

in the stimulation of auto-reactive T cells, which ultimately make their way to

the CNS and initiate MS lesions. APCs comprise of several cell types such as DCs,

monocytes, macrophages, and tissue-resident cells, which include CNS microglia

[52, 53]. DCs, a type of APC, are believed to be the primary APCs involved in the

pathophysiology of MS and are known to be impacted by several DMTs used to treat

MS [53] including IFN

| Pathophysiological aspects of MS | Immune triggering in the peripheray | Meningeal lymphatic vessels | Migration into the CNS | Crossing the BBB into CNS | Inflammatory factors | CNS demyelination and neurodegeneration | ||||||

| APCs | Treg | Activation of T– and B–cells | Glial cells | Neurons | ||||||||

| DC | Monocytes and monocyte-derived macrophage | Oligodendrocytes | Astrocytes | Microglia | ||||||||

| Targeted DMTs | IFN |

Mitoxantrone, natalizumab alemtuzumab, fingolimod, cladribine, DMF, and GA. | IFN |

Mitoxantrone, natalizumab, alemtuzumab, daclizumab, ocrelizumab, ofatumumab, fingolimod, INF |

There is no known impact of DMT. | Mitoxantrone, natalizumab, alemtuzumab, fingolimod, siponimod, ozanimod, ponesimod, and IFN |

Mitoxantrone, natalizumab, alemtuzumab, cladribine, fingolimod, siponimod, teriflunomide, and IFN |

Natalizumab, daclizumab, ocrelizumab, ofatumumab, S1PR modulators, teriflunomide, cladribine, IFN |

Alemtuzumab, fingolimod, siponimod, ponesimod, teriflunomide, IFN |

Fingolimod, natalizumab, ocrelizumab, siponimod, teriflunomide, IFN |

Natalizumab, fingolimod, ocrelizumab, ofatumumab, siponimod, teriflunomide, cladribine, IFN |

Fingolimod, natalizumab, alemtuzumab, siponimod, teriflunomide, cladribine, IFN |

| DMTs Impact | • Induction of apoptosis. | • Blocking myelin breakdown. | • Augmenting Treg and Bregs populations and efficacy. | • Inhibiting the proliferation, differentiation, and activation of inflammatory T– and B–cells. | - | • Decreasing leukocyte migratory activity through the BBB. | • Decreasing the infiltration of leukocytes through the BBB. | • Modifying markers associated with T– and B–cells. | • Decreasing apoptosis and promoting the differentiation, maturation, and remyelination of oligodendrocytes. | • Suppressing astrocytic inflammatory reactions. | • Decreasing microglial inflammasome activation. | • Boosting axonal metabolism. |

| • Alteration of cytokine profile. | ||||||||||||

| • Decreasing activation and accumulation in the CNS. | • Restoring proper neuronal network function. | |||||||||||

| • Decrease in dendritic cell (DC) migratory capacity. | • Altering subsets of T– cells. | • Enhancing the antiinflammatory phenotype. | ||||||||||

| • Inhibiting chemokines responsible for immune cell migration into the CNS. | • Inhibiting the migratory capacity of immune cells. | |||||||||||

| • Decreasing the quantity of inflammatory Th17 cells. | ||||||||||||

| • Reducing the expression of MHC-II and costimulatory molecules. | • Increasing levels of naive and anti-inflammatory cells. | • Normalizing excitability. | ||||||||||

| • Impact on T–cell differentiation. | ||||||||||||

| • Restoring levels of tight junction proteins. | • Providing protection against neuronal damage. | |||||||||||

| • Reducing inflammation and the number of cytotoxic CD8+ T– cells. | ||||||||||||

| • Reduction in antigen presentation ability of DCs. | • Restricting cytokine signaling between the CNS and immune system. | |||||||||||

| • Impacts phagocytic ability. | • Promoting BBB integrity. | |||||||||||

| • Ameliorating previous tissue damage. | ||||||||||||

| • Reducing MMP activity. | ||||||||||||

| • Weakening of DCs’ phagocytic and immunostimulatory capacity. | • Affects differentiation. | |||||||||||

| • Increasing levels of TIMPs and sVCAM-1. | • Enhancing the population of Tregs. | • Reducing axonal and neuronal degeneration. | ||||||||||

| • Induction of apoptosis. | ||||||||||||

| • Promotion of anti-inflammatory profile. | • Increasing the levels of naive T– cells. | |||||||||||

| • Inhibition of DC maturation. | ||||||||||||

| • Decrease in the quantity of DCs in lesions. | • Decreasing central memory T– cells. | |||||||||||

| • Amplifying the responsiveness of T– effector cells to immune regulation. | ||||||||||||

| • Reduce pro-inflammatory cytokines, and increase anti-inflammatory cytokines. | ||||||||||||

| • Decrease levels of chemokines linked to both Th1 and Th2 responses. | ||||||||||||

MS, multiple sclerosis; CNS, central nervous system; S1PR, sphingosine

1-phosphate receptor; IFN

For example, IFN

Monocytes and monocyte-derived macrophage were linked to advanced clinical disability, and disease progression in MS and EAE models. By contrast, microglia have been linked to early MS lesions and MS susceptibility genes, with evidence pointing toward them as being more closely associated with MS genes than neurons or astrocytes [62]. Various DMTs have been recorded to suppress or deactivate these cells during the course of MS (Table 5). For instance, mitoxantrone blocks myelin breakdown by macrophages [63], while natalizumab reduces microglial activation and suppresses the accumulation of microglia/macrophage populations in the CNS [64]. Alemtuzumab reduces the expression of major histocompatibility complex class II (MHC-II) and costimulatory molecules on microglia and infiltrating macrophages [65], while fingolimod impacts their activation and phagocytic ability [66]. Cladribine affects the differentiation of monocytes into macrophages, reduces their pro-inflammatory response, and induces microglial apoptosis [67]. Lastly, DMF suppresses pro-inflammatory macrophages [68], while GA inhibits the activation of monocytes and induces the differentiation of anti-inflammatory macrophages [69].

Tregs are a type of lymphocyte that plays a vital role in maintaining

self-tolerance and regulating immune responses in MS and EAE. Tregs are divided

into two types: naturally occurring CD4+ CD25+ forkhead box P3+

(FOXP3+) Tregs that arise from the thymus, and adaptive Tregs that arise

from immune responses outside the thymus. Both types of Tregs help to maintain

immune homeostasis and regulate autoimmune inflammation. The differentiation of

Treg precursor cells into effector Tregs is influenced by transforming growth

factor beta (TGF-

Inflammatory cells in MS patients are characterized by higher-than-normal levels of effector cytokines and expression of brain-homing chemokine receptors, as well as reactivity to antigens found in the CNS. It is believed that T and B cells in MS patients are prone to a deregulated inhibitory control, making the immune cells more prone to attack. These cells appear relatively resistant to regulation by regulatory cells. The disease pathogenesis implicates both T and B cells and their reactivity to multiple myelin antigens, such as MBP, myelin-associated glycoprotein, and proteolipid protein, which form multilamellar myelin sheaths around the axons and neuron cell bodies. Another protein, myelin oligodendrocyte glycoprotein, situated on the surface of the sheath, acts as an adhesive receptor, and connects neighboring myelinated fibers [51]. These cells infiltrate the BBB, activate local microglia and macrophages, thereby initiating a local inflammation process that leads to tissue damage and chronic inflammation [51].

Several DMTs, such as mitoxantrone, natalizumab, alemtuzumab, daclizumab,

ocrelizumab, ofatumumab, fingolimod, INF-

The theory that encephalitogenic molecules travel to the peripheral areas to activate T and B cells is a subject of ongoing discussion. Lymphatic vessels located in the meninges play a role in transporting macromolecules and immune cells from the cerebrospinal fluid to the peripheral immune system via the cervical lymph nodes, potentially impacting the pathogenesis of MS. The hypothesis suggests that the pathogenicity of MS may be altered by the drainage of encephalitogens out of the CNS, which then triggers the activation of peripheral immune cells. To support this notion, the obstruction of meningeal lymphatic function has been linked to a mitigated course of EAE, as it reduces interactions between T cells and APCs [99, 100]. Additionally, differences in the anteroposterior diameters of cervical lymph nodes between MS patients and healthy individuals lend further credence to the idea of lymphatic drainage contributing to the disease pathology [101]. To the best of the author’s knowledge, no studies have yet explored the effect of DMTs on the meningeal lymphatic vessel system in MS, likely due to its recent discovery and the novelty of this area of research.

Immune cells are believed to be directed towards the CNS where demyelination and

neurodegeneration occur. The involvement of S1P and S1P1R has been suggested in

this process. T cells express S1P1R on their plasma membrane, which gets

downregulated while entering the lymph node. Following activation and clonal

expansion, S1P1R expression increases, facilitating T cell migration from the

lymph nodes. This establishes a gradient of S1P expression, which is sensed by

S1P1R and can shuttle activated T cells back to the circulation possibly leading

to the CNS [102]. Chemokines are crucial for guiding leukocytes to sites of

inflammation within the CNS. Various chemokines have specific receptor-binding

affinities for different leukocyte types, such as neutrophils, eosinophils,

monocytes, DCs, and T cells. They work by directly attracting and activating

integrins on leukocytes to bind to adhesion receptors found on endothelial cells

[103]. DMTs impact this pathway in MS, such as mitoxantrone, natalizumab,

alemtuzumab, fingolimod, siponimod, ozanimod, ponesimod, and IFN

The mechanism by which immune cells cross the BBB into the CNS still remains to be resolved, but some studies suggest impaired junctional integrity with proteins such as occludin, claudin-5, and vascular endothelial-cadherin, barrier properties demonstrated with serum leakage, and reduced or impaired efflux pump activity such as P-glycoprotein (P-gp) as possible reasons [109].

Moreover, during MS, the endothelial cells of the BBB shift their immune

phenotype and increase expression of adhesion molecules such as E-selectin,

L-selectin, intercellular adhesion molecule-1 (ICAM-1), VCAM-1, and atypical

chemokine receptor 1, thus enabling immune cell infiltration [99]. ICAM-1 and

VCAM-1 bind the integrins leukocyte functional antigen 1 and very late antigen-4

(VLA-4) and mediate cellular transfer through the BBB [110]. This leads to

infiltration of immune cells, facilitated by matrix metalloproteinases (MMPs)

expressed by leukocytes that tunnel through the tight junctions and cleave

transmembrane

Immune cell-driven inflammation is considered a subsequent phase in the development of MS. The prevailing view is that the immunological underpinnings of MS involve the mediating actions of T cells, B cells, monocytes, and occasional plasma cells [99]. MS lesions typically form around CNS veins and venules, with active demyelination closely linked to inflammatory infiltrates. These perivascular infiltrates contain lymphocytes and plasma cells, while active tissue damage is associated with macrophages and microglia, all orchestrated by various cytokines, chemokines, and their receptors [50].

Numerous investigations have pointed to the involvement of B cells in the development of MS, as indicated by the detection of B cells, plasma cells, immunoglobulins, and complement deposition within MS lesions, along with the positive response to B cell-targeted therapies [123]. While B cells undergo affinity maturation and proliferation in germinal centers, the direction of B cell destiny is largely influenced by CD4+ T cells, specifically follicular Th cells, which guide their fate through a combination of membrane-bound and soluble stimulatory and inhibitory cues [124].

The significant role of CD4+ T cells and Th cells in MS is supported by evidence from EAE models. These cells precede the arrival of B cells in the CNS parenchyma, often reaching the site before clinical symptoms manifest, and they exhibit the capacity to trigger disease in otherwise healthy organisms. Furthermore, the targeting of antigens specific to Th cells has been shown to partially or even wholly suppress the progression of the disease [125].

Past studies have also highlighted those multiple subsets of CD4+ T cells,

including Th17, Th1, and Th2 cells, are linked to MS lesions. It is primarily the

Th1 cells, which produce IFN

Th17 cells, another subset of Th cells, express the VLA-4 surface antigen,

facilitating their migration into the CNS [51]. These cells exert multiple

effects in the CNS, including the production of high levels of glutamate, which

is harmful to oligodendrocytes. A subpopulation of Th17 cells, known as Th17.1,

secretes high levels of the IL-23 receptor. When stimulated, these cells produce

granulocyte-macrophage colony-stimulating factor (GM-CSF), transforming into more

encephalitogenic cells and intensifying CNS inflammation [51]. Both Th1 and Th17

cell populations increase during the onset of MS [51]. Th9 cells, an additional

subset of CD4+ T cells, produce IL-9 and appear to have an anti-inflammatory

effects on MS. Th9 cells differentiation is promoted by TGF-

While initial studies largely concentrated on the pathogenic role of CD4+ T cells in MS, recent research has progressively acknowledged the significant involvement of CD8+ T cells in the disease [127]. In MS brain lesions, CD8+ T cells are regarded as the most prominent T cell populations and have been found to closely correlate with the degree of axonal damage [127].

The

Macrophages are a dynamic and varied group of cells that play essential roles in immune responses and various disease processes [146]. They are considered professional phagocytes and are abundant within the CNS lesions of MS and EAE. These macrophages originate either from glial cells or from infiltrating peripheral monocytes. In a healthy CNS, peripheral monocytes or macrophages are typically absent; their presence in EAE or MS lesions is often linked to disease onset. Their involvement in the CNS underscores their vital role in the pathogenesis of MS [146].

Depleting monocytes before the onset of symptoms can delay the emergence of EAE and lead to a milder disease progression, while depleting them after disease onset can slow the disease progression [146]. Early in EAE, an increase in peripheral monocytes correlates with greater clinical severity and a greater likelihood of progressing to paralysis. The recruitment of monocytes into the CNS is primarily mediated by chemokine signaling, particularly through the engagement of C-C motif chemokine ligand 2 (CCL2) and C-C motif chemokine receptor 2 (CCR2) in the myeloid compartment. CCR2 levels rise in the blood of EAE patients in response to GM-CSF stimulation [146]. Once monocytes reach the CNS parenchyma, they become activated and differentiate into either myeloid DCs or macrophages. Depending on the signals present within the CNS lesions, macrophages can differentiate into a pro-inflammatory phenotype (M1) or an anti-inflammatory phenotype (M2) [146].

M1 cells secrete various cytokines that are crucial for antigen presentation and the sustained activation of T-cells, contributing to damage to the myelin sheath and surrounding cells, which leads to axonal degeneration [146]. During the remission phase, M2 cells predominate in the CNS lesions. M2 cells suppress pro-inflammatory cytokines and antigen presentation, thereby inhibiting CD4 T cell responses and facilitating remyelination and the differentiation of oligodendrocytes within CNS lesions. The polarization of M2 cells is beneficial in preventing the development of EAE [146].

DMTs impact the pro-inflammatory activity of macrophages. For instance, mitoxantrone halts myelin degradation by macrophages [63], while natalizumab decreases their activation and presence in the CNS [64]. Alemtuzumab reduces MHC-II expression on macrophages [65], fingolimod modifies their activation and phagocytic ability [66]. Cladribine affect monocyte-to-macrophage differentiation and promotes their apoptosis [67]. DMF suppresses pro-inflammatory macrophages [68], and GA encourages the development of anti-inflammatory macrophages [69].

Neutrophils play a significant role in the pathogenesis of MS. Animal models have demonstrated that neutrophils contribute to disease development and pathogenicity [147]. Following just 24 h of disease induction, neutrophils accumulate near the meninges in EAE, with their increased presence observed during both preclinical and peak phases of the disease [147]. GM-CSF and the secretion of chemokines (CXCL1, CXCL2, and CXCL6) from Th17 cells promote the recruitment of neutrophils to the brain and spinal cord in EAE [147].

In the blood of MS patients, increased levels of neutrophil-activating

chemokines and neutrophil-derived enzymes (e.g., CXCL1, CXCL8, neutrophil

elastase, and myeloperoxidase [MPO]) are observed, which are linked to the

formation of new inflammatory lesions [147]. The neutrophil-to-lymphocyte ratio

is proposed as a marker of disease activity, as it tends to be elevated in MS

patients, particularly during relapse compared to remission [147]. Neutrophils

possess a diverse array of effector functions that contribute to disease

pathogenesis, including the release of inflammatory mediators and enzymes such as

IL-1

In addition to their role as pro-inflammatory cells, neutrophils also function

as anti-inflammatory cells. They infiltrate tissues and enhance the uptake of

apoptotic neutrophils by macrophages. Neutrophils scavenge inflammatory

chemokines and cytokines using decoy and scavenger receptors [147]. The process

of efferocytosis, where macrophages engulf apoptotic neutrophils, promotes the

polarization of macrophages to an M2-like phenotype and negatively regulates

inflammation [147]. Several DMTs have been observed to influence neutrophil

function, counts and migratory capacity across the BBB. These include:

IFN

Cytokines are small, versatile proteins that play a crucial role in cellular

communication. These molecular messengers exert a wide range of effects, known as

pleiotropic functions, influencing various biological processes in both normal

physiological states and disease conditions. By facilitating intercellular

signaling, cytokines orchestrate complex interactions within the immune system

and beyond, contributing to the maintenance of health and the development of

pathological states [51]. In MS, cytokines play pivotal roles in the

pathogenesis of the disease. They are instrumental in activating encephalitogenic

lymphocytes, particularly Th1 and Th17 cells, and in facilitating the migration

of these lymphocytes into the CNS [51]. The differentiation of Th1 cells is

orchestrated by a triad of cytokines: IFN

The differentiation of Th17 cells is subject to tight regulation, involving a

complex interplay of cytokines. Primarily, this process requires the presence of

TGF-

In the context of MS, researchers have observed significant alterations in the

cytokine profile. Specifically, increased production levels of IL-6, IL-23, and

IL-1

Cytokines also play a crucial role in modulating lymphocyte migration across the

BBB. This process is intricate and involves multiple mechanisms [51].

TNF-

Several DMTs deplete cells that produce pro-inflammatory cytokines, reducing

their levels in cerebrospinal fluid and plasma, while increasing the levels of

anti-inflammatory cytokines. These pro-inflammatory cytokines include GM-CSF,

IFN

Astrocytes, microglia, oligodendrocytes, and neurons interact to control key processes in the CNS including development, inflammation, metabolism, and neuronal activity. These diverse cell types work together in complex networks to maintain homeostasis and support proper CNS function. In the context of MS, disruptions or imbalances in these intricate cell-cell interactions can contribute to the pathogenesis of the disease. Disruptions in the coordinated functions of astrocytes, microglia, oligodendrocytes, and neurons can contribute to the development and progression of the disease [47].

The CNS comprises both neuronal and non-neuronal cells including glial cells such as astrocytes, microglia, and oligodendrocytes, which play a critical supportive role in proper functioning of the nervous system [161]. Astrocytes and microglia play an essential part in the inflammation observed in the CNS during MS. Oligodendrocytes, the myelin-producing cells, are crucial in the demyelination process that characterizes the disease [47, 161].

3.7.1.1 Astrocytes

Astrocytes are crucial to CNS homeostasis, supporting neurotransmitter

recycling, maintaining the BBB, and balancing ionic distributions. MS

pathogenesis involves astrocytes playing either a pro- or anti-inflammatory role

[161]. Some astrocytes exhibit neurotoxicity in EAE and MS, exacerbating

neurodegeneration and inflammation. By contrast, others induce T cell apoptosis

as a regulatory measure against inflammation and neurodegeneration. The immune

actions of astrocytes vary depending on modulation by Tregs or promotion by

pathogenic T cells. Astrocytes expression of S1PR affect the disease severity,

demyelination, and axonal loss [162], and the dysregulated astrocyte-specific ion

channels may also influence its pathogenicity [161]. Astrocyte heterogeneity in

MS/EAE may provide valuable insights into the disease [161]. DMTs such as

fingolimod, natalizumab, ocrelizumab, siponimod, teriflunomide, IFN

3.7.1.2 Microglia

Microglia, a myeloid cell in the CNS derived from the yolk sac, regulate synapse

development, pruning, and excitability, acting as principal phagocytes and

regulators of inflammation [161]. In MS, microglia play a significant role in

remyelination, promoting oligodendrocyte precursor cells differentiation and

remyelination, but this function may be impaired by age-dependent increases in

circulating TGF-

3.7.1.3 Oligodendrocytes

Oligodendrocytes are the predominant cells responsible for the production of myelin and play a crucial role in the formation of myelin sheaths around nerve axons. While some oligodendrocytes may be preserved from damage during direct attacks by active T cells, severe demyelination can lead to the complete loss of these cells and a lack of remyelination. This might occur as a result of anomalies affecting OPC, an increased expression of specific immunoproteasomes in oligodendrocytes, or as a consequence of antigen-mediated immune responses launched against these cells [161]. Factors such as astrocyte signals, chondroitin sulfate proteoglycans, and hyaluronan oligomers may impede oligodendrocyte maturation and remyelination, while aged oligodendrocytes may also limit the remyelination process [161].

Recent research has suggested that individuals with MS demonstrate altered

oligodendroglial heterogeneity, potentially explaining the disease progression in

predisposed individuals [187]. Moreover, in MS, oligodendrocytes can function as

innate immune cells that execute phagocytosis and antigen cross-presentation to

cytotoxic CD8+ T cells, as well as activating memory and effector CD4+

T cells [188]. DMTs such as alemtuzumab, fingolimod, siponimod, ponesimod,

teriflunomide, IFN

The primary cause of clinical manifestation in MS is neuronal damage,

particularly axonal damage. Various mechanisms contribute to axonal damage and

are linked to ion channel dysregulation, the selective vulnerability and loss of

excitatory neurons, and loss of inhibitory synaptic inputs [197]. Additionally,

mitochondrial dysfunction, genetic predisposition, and defects in trophic and

anti-inflammatory intercellular communication are involved in neuronal death

[198]. However, certain DMTs have been shown to alleviate neuronal damage and

promote neuron survival, axonal projections, and synaptic function. For instance,

fingolimod, natalizumab, alemtuzumab, siponimod, teriflunomide, cladribine,

IFN

Although researchers have made significant strides investigating the pathophysiology of MS, it remains a complex disease that is not yet fully understood. Available DMTs target different aspects of this disease pathophysiology; nonetheless, it is unclear why these treatments alone are not sufficient to fully resolve the disease or mitigate its effects on patients.

Exploring the insufficiency of DMTs in fully resolving or mitigating the effects of MS requires consideration of various factors. These include the pathophysiology of the disease, cellular communication, the dynamic functionality of the cells, persistent autoantigen presentation, the optimal timing and mechanism of treatment, accounting for environmental factors, comorbidities, lack of diversity in DMTs clinical trials, risk-benefit profile, the potential role of pharmacogenomics in future MS treatment, the risk of administered DMTs causing new somatic mutations, the likelihood of developing anti-drug antibodies (ADA), and the wearing-off phenomenon.

The current available DMTs for MS target various aspects of the disease pathophysiology. However, there are still key components that remain incompletely addressed by the existing DMTs. One emerging area of interest is the role of meningeal lymphatic vessels in MS pathology. Recent research has identified the meningeal lymphatic system as a new aspect of MS pathology that requires further elucidation. These meningeal lymphatic vessels may play a crucial, and potentially primary, role in the development and progression of the disease. Although the exact function of the meningeal lymphatic system in MS is still under investigation, it is possible that this component of the disease pathophysiology has been overlooked or underappreciated [99, 100, 101].

Existing DMTs may not adequately target or modulate the processes occurring within the meningeal lymphatic vessels. Continued research is needed to fully characterize the involvement of the meningeal lymphatic system in MS pathogenesis. Understanding this newly identified aspect of the disease could open up new therapeutic avenues and highlight the limitations of current DMTs in addressing all the underlying drivers of MS. Targeting the meningeal lymphatic vessels may become an important consideration for the development of future emerging therapies.

While the current studies on DMTs for MS have provided valuable insights, they often fall short in fully addressing the role of cellular communication in the underlying pathology of the disease. The complex interactions and dynamic communication between the various cell types in the CNS, including astrocytes, oligodendrocytes, microglia, and neurons, are crucial in maintaining homeostasis and driving pathological processes [47]. However, the current understanding of how disruptions in these cellular communication networks contribute to the development and progression of MS remains limited.

Existing DMTs primarily focus on targeting specific immune mechanisms or modulating broader inflammatory pathways [11]. However, the intricacies of how the crosstalk between different CNS cell populations is altered in MS, and how this may impact disease pathogenesis, have not been extensively explored. Delving deeper into the nuances of cellular communication, signaling, and coordination within the CNS could unveil new opportunities for therapeutic interventions. Identifying key nodes or pathways in the dysregulated cellular networks may lead to the development of more targeted and comprehensive treatment strategies for MS.

The effects of DMTs on immune cells must be considered in the context of their dynamic functionality. Astrocytes and microglia, for example, can act as both pro-inflammatory and anti-inflammatory cells, depending on the specific environmental cues and signaling pathways activated. When targeting these immune cells with DMTs, it is important to take into account their multifaceted roles in the CNS. Astrocytes and microglia can play a protective, homeostatic function by clearing cellular debris and supporting neuronal health, but they can also become reactive and contribute to inflammation and tissue damage under certain conditions [161, 174]. The functional derivatives of these immune cells must be carefully evaluated when designing and implementing DMT strategies. Therapies that aim to modulate astrocyte or microglial activity should consider their potential to shift the balance between pro-inflammatory and anti-inflammatory states, as this can have significant implications for disease progression and neurological outcomes. By understanding the time-dependent and context-dependent functionality of key immune cell types, researchers and clinicians can develop more targeted and personalized DMT approaches that take into account the dynamic nature of the cellular landscape in the CNS.

The persistent presentation of autoantigens to the immune system is a key driver of the pathogenesis in MS. In MS, myelin proteins and other CNS components are recognized as foreign by the patient’s own immune cells, leading to chronic inflammation and autoimmune attack on the brain and spinal cord [3, 48, 50]. This ongoing autoantigen presentation sustains the activation of autoreactive T and B cells, fueling the cyclical pattern of immune cell infiltration, demyelination, neurodegeneration, and disease exacerbations that characterize MS [3, 48, 50]. Importantly, the continuous availability of these CNS autoantigens for recognition by the immune system poses a significant challenge for the efficacy of current DMTs.

Many DMTs work by modulating the immune system, for example, by sequestering lymphocytes in lymphoid tissues, depleting specific immune cell subsets, or altering their trafficking and activation [11]. However, as long as the target autoantigens remain present and accessible, the autoimmune process can resume even in the face of these immunomodulatory therapies. This may help explain why, despite the availability of numerous effective DMTs, disease progression and relapses often persist in many MS patients. The underlying autoimmune response, driven by the perpetual exposure to CNS autoantigens, is not fully addressed by the current DMT approaches. Therefore, strategies to interrupt this cycle of autoantigen presentation may therefore be an important frontier in MS therapeutics. Approaches such as antigen-specific immunotherapies, which aim to induce tolerance to key myelin and neuronal components, or therapies that can clear pathogenic autoantigen deposits, may hold promise in enhancing the long-term efficacy of DMTs [47, 208, 209].

To optimize the use of DMTs in MS treatment, physicians must consider both the

disease stage and progression level. Different DMTs have varying mechanisms of

action and are beneficial for different stages of the disease. In cases where

immune cells are triggered in the periphery, and immune cell education with

encephalitogenic potency is a concern, IFN

When evaluating DMTs for patients with MS, it is crucial to consider not only the direct effects of the therapies, but also the broader environmental and genetic factors that can influence disease susceptibility and progression. Several key environmental factors have been implicated in MS risk and pathogenesis including prior infections, vitamin D deficiency, obesity, smoking, and disruptions to the gut microbiome. These environmental susceptibility factors can significantly impact genetic transcription and immune cell trafficking into the central nervous system, ultimately shaping the individual’s disease profile and response to treatment [4, 41, 47]. For example, vitamin D has been shown to influence the genetic expression of numerous genes linked to MS susceptibility and immunological processes [1, 41, 48]. Similarly, alterations to the gut microbiome modulate immune cell trafficking, which can have downstream effects on disease activity and treatment efficacy [47].

However, current research and clinical practices surrounding DMT selection often fail to adequately address these important environmental and genetic factors. By overlooking these broader disease determinants, clinicians may be missing critical opportunities to personalize treatment approaches and optimize outcomes for patients with MS. Environmental factors, such as geographic location and sunlight exposure, play a significant role in MS epidemiology. Patients living in sunny, equatorial regions tend to have different disease characteristics and progression compared to those in countries with more pronounced seasonal variations. These environmental influences can impact an individual’s risk of developing MS, as well as their response to various DMTs [1]. Similarly, genetic predisposition is a well-established determinant of MS susceptibility and phenotype. Certain genetic markers and profiles may confer differential risks and inform the optimal therapeutic approach for a given patient. However, these important genetic factors are often overlooked in the current DMT selection process [1].

Integrating the assessment of environmental susceptibility factors and their genetic and immunological implications into the DMT selection process can provide valuable insights to guide more tailored, comprehensive treatment strategies [47, 214]. This holistic approach recognizes the complex interplay between a patient’s genetic predisposition, environmental exposures, and the mechanism of action of the chosen DMT, ultimately enhancing the potential for successful long-term disease management.

People with MS often have other coexisting medical conditions, known as comorbidities. An individual with MS have higher rates of ischemic heart disease, stroke, peripheral vascular disease, and psychiatric disorders compared to the general population [215, 216, 217]. Comorbidities are especially common in underrepresented minority and immigrant groups with MS. Comorbidities impact the entire disease course. At an individual level, comorbidities are associated with more relapses, greater physical/cognitive impairment, reduced quality of life, and increased mortality [215]. Notably, the incidence of comorbid autoimmune diseases seems higher in MS patients compared to healthy individuals, with up to 18% of all MS cases in the New York MS Consortium registry suffering from additional autoimmune conditions [216].

Comorbidities may develop due to shared risk factors, one condition causing

another, or an underlying third condition. However, clinical trials of DMTs often

exclude individuals with comorbidities, limiting the real-world applicability of

trial results [215]. The most common autoimmune comorbidities in MS include

rheumatoid arthritis, psoriasis, and inflammatory bowel diseases [217]. This

overlap in pathogenesis between MS and other autoimmune disorders suggests that

some DMTs could potentially address both disease entities, potentially

simplifying treatment for these patients. For example, DMF may be a useful option

for MS patients also suffering from necrobiosis lipoidica associated with

diabetes or non-infectious uveitis [218, 219]. Similarly, siponimod was

well-tolerated and showed benefits in a phase II study of patients with

refractory dermatomyositis [220]. Comorbidities can also affect DMT initiation,

adherence, and effectiveness [221]. Studies show higher comorbidity burden and

the presence of specific comorbidities such as anxiety or ischemic heart disease

are associated with lower likelihood of starting injectable DMTs and increased

risk of discontinuing DMTs such as IFN

Understanding and managing comorbidities is crucial for optimizing outcomes in people living with MS. Prioritizing the patient’s symptom profile and optimizing their medication use are essential first steps in effectively evaluating and managing comorbidities. This foundation allows the clinician to develop a comprehensive, patient-centered approach to address this challenging and often complex symptom.

Another concerning aspect of DMTs for MS is the lack of representation from racial and ethnic minority populations in clinical trials [224, 225]. This presents a significant challenge in understanding the true effects, both beneficial and adverse, of these drugs among minority MS patients. The patient populations enrolled in pivotal DMT clinical trials have historically been predominantly white, with underrepresentation of racial and ethnic minorities who bear a disproportionate burden of MS. This lack of diversity limits the generalizability of the trial findings to the broader MS patient population, especially given the known differences in disease course, treatment response, and comorbidity profiles across racial/ethnic groups [224, 225]. Without robust data from diverse clinical trial cohorts, clinicians face uncertainty when prescribing DMTs for minority patients with MS. The effects of these therapies, including efficacy in reducing relapses and disability progression, as well as the incidence and severity of side effects, may differ significantly in non-white individuals compared to the trial populations [224, 225]. This knowledge gap presents substantial barriers to delivering equitable, personalized care for racial and ethnic minority patients with MS. Addressing the lack of diversity in DMT clinical research must be a priority to ensure these powerful therapies can be utilized safely and effectively across all populations affected by this debilitating neurological condition.

The complexity of MS precludes a simple, one-size-fits-all approach to DMT selection. Instead, a careful, personalized evaluation of the risk-benefit profile for each DMT is necessary when choosing the optimal treatment for a patient. When selecting a DMT clinicians must consider a multitude of factors, including the patient’s specific disease characteristics, personal preferences, presence of comorbid conditions, and reproductive plans [226]. This individualized approach is crucial to ensure the chosen DMT effectively manages the patient’s MS while minimizing the potential for harm.

One such consideration is the patient’s susceptibility to opportunistic infections, such as PML associated with prior JCV exposure [15]. The development of secondary autoimmune disorders or treatment-induced lymphopenia also merit careful evaluation, as these complications can significantly impact the tolerability and continued use of certain DMTs [18, 19, 24]. Furthermore, GI irritability should not be overlooked, as this side effect can also affect a patient’s ability to adhere to and derive long-term benefit from their prescribed DMT regimen [11, 26]. These types of treatment-emergent adverse events have the potential to disrupt the continuity of care, ultimately compromising the overall efficacy of the available DMT options.

Ultimately, the selection of a DMT for an individual patient with MS requires a comprehensive evaluation of the complex interplay between the patient’s disease profile, comorbidities, and the unique risk-benefit characteristics of each therapeutic option. Only by employing a personalized, nuanced approach can clinicians ensure the chosen DMT strikes the delicate balance between effective disease management and minimizing potential adverse outcome.

Personalized treatment is emerging as a potentially beneficial approach in the field of MS. Pharmacogenomics, a growing area in medicine that targets patient genetics when determining treatments, could be effective in treating MS. The disease is complex and has genetic susceptibility factors that influence progression, and variability in patient response to available DMTs can be attributed to genetics. Personalizing medicine can optimize patient response and help deliver the best treatment options. However, this field is still in its early stages and requires further research [227, 228].

The evidence suggests that certain DMTs used in MS treatment have the potential to induce new somatic mutations that can impact disease pathophysiology. Research indicates that fingolimod, teriflunomide, cladribine, alemtuzumab, and ocrelizumab can cause teratogenicity and embryonic lethality [229]. This leads to concerns that DMTs may affect genomic integrity and induce new mutations not present during disease development. In particular, cladribine has been found to have mutagenic effects on lymphocytes in patients with RRMS [230], while alemtuzumab has been linked to a risk of secondary autoimmunity [19]. These findings underscore the risk these drugs pose to genomic makeup. Due to these potential risks, patients taking these drugs must undergo regular monitoring for potential adverse effects. However, further research is necessary to determine the potential impact of certain DMTs on the development of new somatic mutations and how they might affect treatment outcomes.

ADAs represents a critical factor that impacts treatment discontinuation in MS patients. When administering monoclonal antibody DMTs, which comprise chimeric, humanized, and fully human antibodies, there is the potential for therapeutic resistance from the development of binding and neutralizing antibodies. This phenomenon can occur at rates ranging from under 1% to over 80% within a year of starting treatment [231, 232, 233]. Close monitoring of ADAs is crucial to optimize treatment outcomes for patients with MS and to ensure that treatment can be adjusted as needed.

Recent literature has reported the wearing-off phenomena in patients using monoclonal antibody treatment, manifesting as a reduction in perceived benefits before the next dose is due, often accompanied by depression and reduced treatment satisfaction. The definition of wearing off can vary significantly among patients and clinicians, making it difficult to interpret this phenomenon accurately [234, 235]. Interestingly, findings from a study indicate that patients treated with ocrelizumab, who reported wearing-off during treatment, showed reduced immunomodulation and increased neuroaxonal damage, potentially indicating a reduction in treatment response during the wearing-off period [236]. Further research is necessary to standardize the definition of wearing-off phenomena and develop strategies to address this challenge, optimizing treatment outcomes for patients with MS.

The current DMTs for MS have limitations in fully treating the disease, necessitating the development of new emerging therapies that aim to overcome the shortcomings of the existing DMTs. Several promising strategies are currently being explored, which may help address some of the key limitations of the current DMTs. These include therapies that target cellular communication, induce antigen-specific immune tolerance, and modulate environmental factors that contribute to MS pathogenesis [47].

Bruton’s tyrosine kinase (BTK) inhibitors target B cells and peripheral myeloid cells, limiting their pathogenic crosstalk with T cells. Some BTK inhibitors can also cross the BBB, potentially suppressing detrimental microglial functions and promoting remyelination, offering hope for treating progressive MS [47, 237].

Antigen-specific tolerance induction includes cell-based methods, such as administration of antigen-loaded tolerogenic DCs, autoantigen-specific regulatory T-cells, or chimeric antigen receptor T cells. However, logistical challenges limit the clinical implementation of cell-based therapies. Alternatively, nanoparticle-based, and mRNA-based approaches that deliver myelin antigens and tolerogenic adjuvants have shown promise in inducing bystander immune tolerance, an important feature considering the heterogeneity of autoantigens targeted in MS [47, 208, 209].

Environmental factor modulation identifies environmental factors associated with MS development, such as EBV and specific gut microbiome compositions, opening new therapeutic avenues including vaccines and probiotic supplementation. Additionally, factors such as circadian rhythms and pollution may provide insights into environmentally controlled pathways involved in MS pathogenesis [47, 214]. While these emerging therapies hold significant promise, their long-term efficacy, safety, and practical implementation remain to be fully established through continued research and clinical evaluation.