1 Department of Ophthalmology, Pennsylvania State University College of Medicine, Hershey, PA 17033, USA

2 Section of Research Resources, The Pennsylvania State University College of Medicine, Hershey, PA 17033, USA

Abstract

Age-related macular degeneration (AMD) is the most common cause of vision loss in people above the age of 50, affecting approximately 10% of the population worldwide and the incidence is rising. Hyperreflective foci (HRF) are a major predictor of AMD progression. The purpose of this study was to use the sodium iodate mouse model to study HRF formation in retinal degeneration.

Sodium iodate (NaIO3) treated rodents were studied to characterize HRF. 3-month-old male wild-type (WT) C57Bl/6J mice were injected with phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) or varying doses of NaIO3 (15–60 mg/kg). Optical Coherence Tomography (OCT) images were collected at baseline and several days post-NaIO3 injection. Retinal thicknesses were measured using Bioptigen software. Seven days post-injection, eyes were prepared for either transmission electron microscopy (TEM), Hematoxylin & Eosin (H&E), or immunofluorescence.

OCT imaging of the mice given higher doses of NaIO3 revealed HRF formation in the neural retina (n = 4). The amount of HRF correlated with the degree of retinal tissue loss. H&E and TEM imaging of the retinas seven days post-NaIO3 injection revealed several pigmented bodies in multiple layers of the retina (n = 3–5). Immunofluorescence revealed that some pigmented bodies were positive for macrophage markers and an epithelial-to-mesenchymal transition marker, while all were retinal pigment epithelium (RPE) 65-negative (n = 4).

The data suggest that NaIO3 induces the formation of HRF in the outer retina and their abundance correlates with retinal tissue loss. The experiments in this study highlight NaIO3 as a clinically relevant model of intermediate AMD that can be used to study HRF formation and to discover new treatment targets.

Keywords

- macular degeneration

- retinal pigment epithelia

- hyperreflective foci

- epithelial-to-mesenchymal transition

Macular degeneration is a major cause of vision loss in people over 50 years old, with the most common form being Age-related macular degeneration (AMD), impacting an estimated 18.34 million people 40 years and older [1]. There are two types of late-stage AMD, wet and dry. While wet AMD is treatable, it impacts only 10% of the patients with AMD [2]. Most patients suffer from dry AMD, which is primarily characterized by the formation of large drusen and can develop into geographic atrophy. Unfortunately, there are no standardized treatment options for this patient population. Patients are recommended to take Age-related Eye Disease Study 2 (AREDS2) vitamins which have been shown to have some effect on slowing the progression of AMD [3, 4]. Although the underlying mechanisms of AMD are not completely understood, many known stressors contribute to its development, including age, genetics, and lifestyle.

Patients with AMD experience progressive central vision loss, and fundoscopic exams reveal drusen formation and pigment accumulation. Retinal imaging obtained by spectral domain optical coherence tomography (OCT) also reveals sub-retinal retinal pigment epithelium (RPE) deposits and hyperreflective foci (HRF) in the outer retina. HRF are anomalous puncta detected by OCT, which correlate with hyperpigmentation on fundus imaging. The presence of HRF is a strong predictor of AMD disease progression; however, their origin remains unknown [5, 6, 7, 8, 9]. HRF have also been used as an indicator of treatment efficiency in neovascular AMD [10]. Some evidence suggests that HRF may be derived from RPE cells that have undergone epithelial-to-mesenchymal transition (EMT) [5, 11, 12]. While others suggest that HRF are due to infiltrating macrophages that contain partially digested RPE fragments [13]. Since HRF are closely linked to disease progression, investigating the molecular mechanisms underlying their formation and development may provide essential information to improve treatment strategies in patients with AMD.

The sodium iodate (NaIO3) model is a well-established method to induce acute RPE degeneration; however, the consequent production of HRF in this model has not been extensively characterized. Previous labs have used concentrations of NaIO3 ranging from 10 mg/kg to 100 mg/kg with differing results. NaIO3 acts as an oxidative stressor that selectively damages the RPE cells at optimal doses [14]. A recent study has shown that varying concentrations of NaIO3 can yield a variety of results depending on age and gender [15]. The retinas of older mice were more susceptible to NaIO3-induced injury when compared to younger mice of the same gender. Young female mice also had decreased injury when compared to male mice of the same age. The degree of variability of retinal damage differed between the older male and female mice, with the male mice having either no injury or widespread injury after 25 mg/kg while the majority of female mice had widespread retinal injury [15]. The fact that retinas of older mice are more susceptible to NaIO3-induced injury supports the validity of the model because AMD strongly correlates with age. The purpose of this study was to investigate the potential of using the NaIO3 model to characterize HRF and propose this as a model to study the role of HRF in macular degeneration.

C57BL/6J mice were bred in the central animal facility at Pennsylvania State University College of Medicine in Hershey, Pennsylvania. This study used 3-month-old male mice for all experiments. A small cohort of female mice was used to determine that there were no sex-based differences in the response to NaIO3, at least detected by the imaging modalities used in this study. All animals had unlimited access to food and water and were maintained on a 12-hour light/dark cycle. All animal husbandry and experimental procedures were performed in accordance with the Public Health Service Policy on Humane Care and Use of Laboratory Animals, and were approved by the Pennsylvania State University College of Medicine Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee. Experiments were also in compliance with the Association for Research in Vision and Ophthalmology statement for the use of animals in ophthalmic and vision research.

NaIO3 solution (5 mg/mL, Sigma-Aldrich #S4007, St. Louis, MO, USA) was

freshly prepared in sterile phosphate-buffered saline (PBS), pH 7.4, on the day

of injection. Mice received a single intraperitoneal (i.p.) injection of 0 (PBS

vehicle control), 15, 30, 45, or 60 mg/kg (n = 4 per dose) and were housed for

seven days post-injection. This range was chosen to mimic intermediate AMD, based

on other studies showing moderate to severe damage to the retina after NaIO3

doses 30 mg/kg or higher with a more rapid decline after doses

Mice were anesthetized using a 100 mg ketamine (Vedco, Inc. #50989-996-06, St.

Joseph, MO, USA)/10 mg xylazine (Akorn #59399-110-20, Decatur, IL, USA)/kg i.p.

injection. A drop of 2.5% proparacaine-HCl

(Bausch & Lomb #17478-263-12, Lakefront, IL, USA) solution and 1%

phenylephrine (Paragon BioTeck, Inc. #42702-102-15, Portland, OR, USA) was

placed on each eye for topical anesthesia and pupil dilation, respectively.

Artificial tears and an eye cover (custom 3D-printed) were used to protect the

cornea from dehydration before image acquisition. OCT images were collected using

Envisu R2210 (Bioptigen, Durham, NC, USA) fitted with mouse optics

pre-NaIO3, and 1-, 3-, 5- and 7 days post-NaIO3 injection. Images were

centered on the optic nerve head, and 1.4 mm

The greyscale of the OCT images was inverted to assist with easier quantification. The number of HRF was quantified manually. Before quantification, the images were deidentified and the concentration of NaIO3 was removed from labels. Intraretinal hyperreflective spots were characterized as being distinct from the RPE layer but with similar reflectivity, and their size ranged from 10–45 µm. Other artifacts were not included due to their lack of hyperreflectivity and/or lack of distinction from other structures in the retina. HRF in the vitreous were not counted.

At day seven after NaIO3 treatment, mice were euthanized by CO2 asphyxiation and the eyes were removed and placed in ice-cold PBS (pH 7.4). Eyecups were prepared as previously described [19, 20, 21]. Briefly, the eye was placed in ice-cold PBS and the cornea, lens and vitreous were removed under a dissection microscope. Eyecups were then fixed with 4% paraformaldehyde (PFA) (Fisher Scientific #T353-500, Hampton, NH, USA) for 15 min at room temperature (RT) and washed three times for 5 min in PBS. The eyecups were then placed in 30% Sucrose (MP Biomedical #194747, Santa Ana, CA, USA)/0.05% sodium azide (Sigma Aldrich #S-8032, St. Louis, MO, USA) solution and stored at 4 °C until processing. The eyes were frozen in 7.5% gelatin (Sigma Aldrich #G2500-500G)/15% sucrose (MP Biomedical #194747) and sectioned using a cryostat (12 µm).

Six sections per mouse were examined. The sections were blocked using 5% normal

donkey serum (NDS) (Jackson ImmunoResearch Labs #017-000-121, West Grove, PA,

USA) for 1 hour and incubated in primary antibodies overnight at 4 °C.

The sections were then rinsed using 1

Six sections per mouse were fixed again in 4% PFA overnight at 4 °C and rehydrated through graded ethanol (100%, 95%, 70%) before 10 min. incubation in hematoxylin. Then they were rinsed using tap water, dipped in EtOH/HCl twice, and then ammonia water for 30 s. The sections were then submerged in Eosin-R for 2 min. Sections were dehydrated through graded ethanol, and cleared in xylene. The slides were mounted using Cytoseal 60 mounting media (Thermo Scientific #8310-16, Waltham, MA, USA). The sections were imaged using a Zeiss AxioObserver v7.0 microscope fitted with an Apotome (Zeiss, Oberkochen, Germany). Images were acquired using Zen software (version Lite, Zeiss, Wetzlar, Germany). The thickness of retinal layers and the number of pigmented lesions were quantified manually. The central and peripheral regions were determined by dividing the length of the retina into four parts. The inner portions were considered to be central and the outer portions were considered to be peripheral.

Mice were euthanized as described above. Eyes were removed and placed in transmission electron microscopy (TEM) fixative (0.16 M cacodylate buffer (Electron Microscopic Sciences Cat #1165, Fort Washington, PA, USA), 16% paraformaldehyde (Electron Microscopic Sciences #15700), 8% glutaraldehyde (Electron Microscopic Sciences #16000), 30% sucrose, and 1 M CaCl2) for 1 hour at 25 °C. The iris and lens were removed and the eyecup was placed in TEM fixative for 24 hours at 4 °C. After fixation, the eye cup was cut in half through the optic nerve. The central portion of each half was removed and placed in TEM fixative for processing in the Pennsylvania State College of Medicine TEM core facility. Samples were fixed using 2.5% glutaraldehyde/2% paraformaldehyde in 0.1 M cacodylate buffer (pH 7.4) and further fixed in 1% osmium tetroxide (Electron Microscopic Sciences #19100) in 0.1 M cacodylate buffer (pH 7.4) for 1 hour. Samples were dehydrated in a graduated ethanol series and embedded in Epon 812 (Electron Microscopic Sciences #14121). Thin sections (70 nm) were stained with uranyl acetate (Electron Microscopic Sciences #22400) and lead citrate (Electron Microscopic Sciences #17800). 9 sections per eye were examined for qualitative differences using a JEOL JEM1400 Transmission Electron Microscope (JEOL USA Inc., Peabody, MA, USA). The TEM Core (RRID:SCR_021200) services and instruments used in this project were funded, in part, by the Pennsylvania State University College of Medicine via the Office of the Vice Dean of Research and Graduate Students and the Pennsylvania Department of Health using Tobacco Settlement Funds (CURE). The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the University or College of Medicine. The Pennsylvania Department of Health specifically disclaims responsibility for any analyses, interpretations, or conclusions.

Data are presented as mean

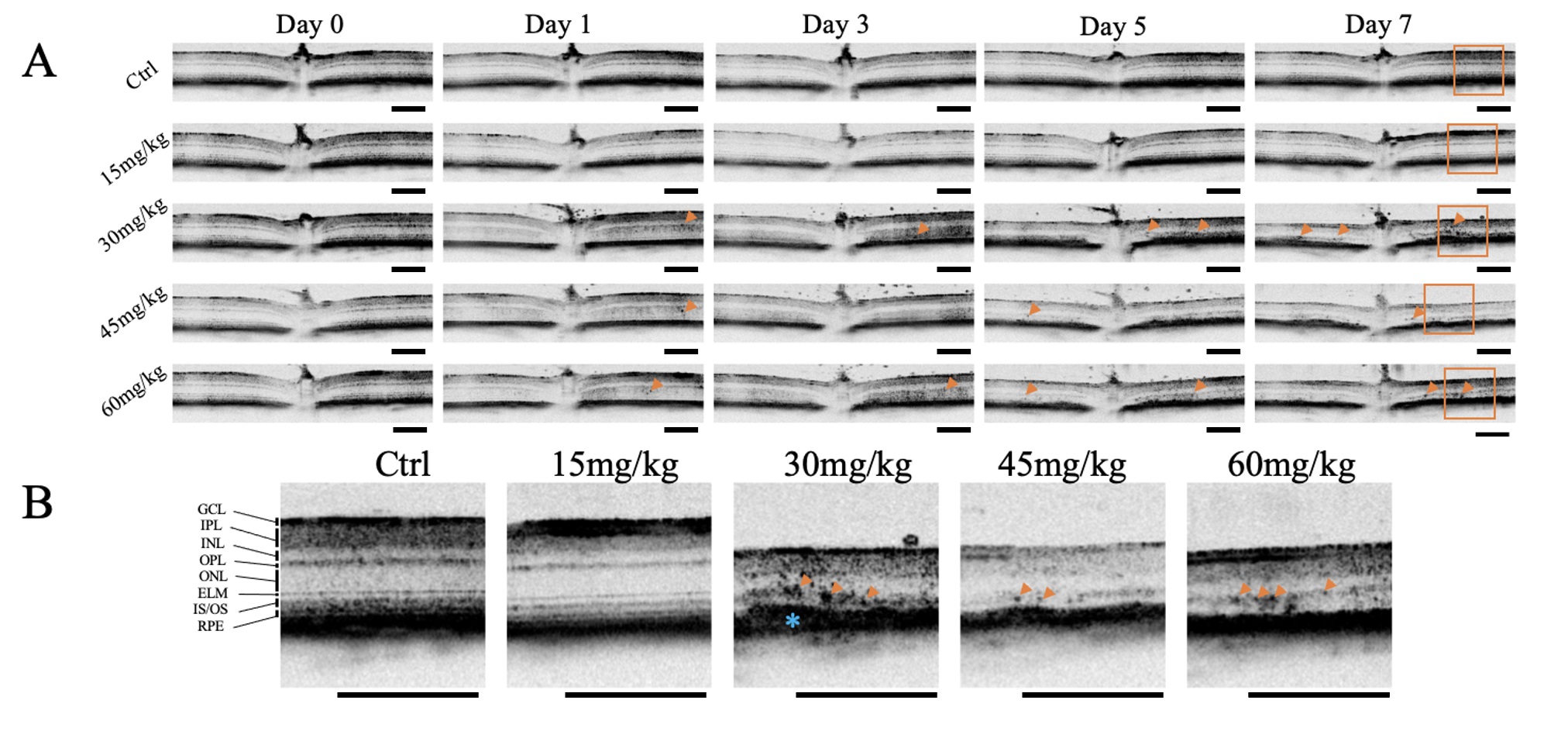

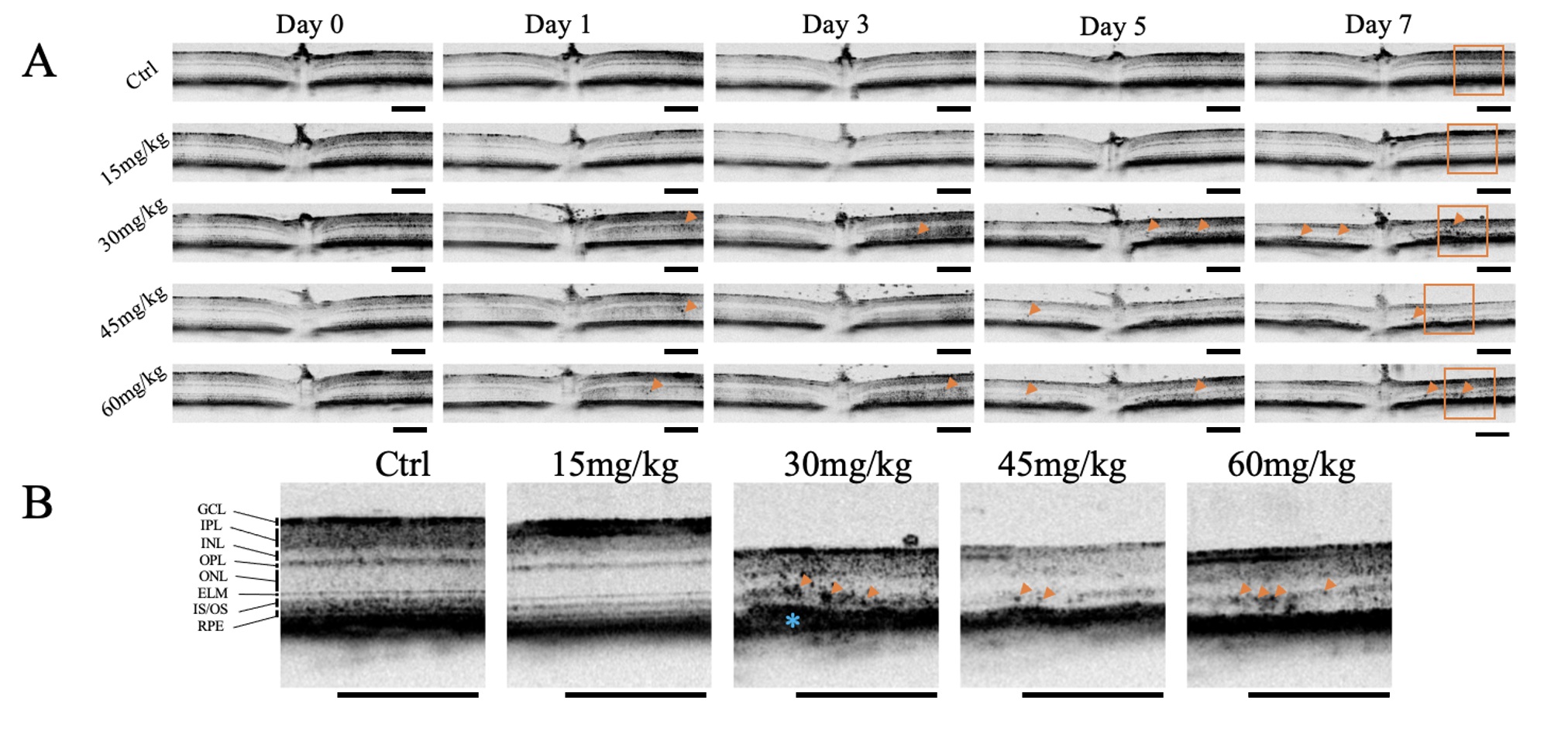

Retinas were imaged by OCT on Day 0, before injection with NaIO3 or the

vehicle, and also 1, 3, 5, and 7 days after NaIO3. On day 0 there were no

observable differences in the morphology of the retinas between groups. No HRF or

other anomalies were noted on OCT images No HRF were present in retina of mice

given vehicle or 15 mg/kg NaIO3 after 7 days; however, HRF were observed in

mice given 30 mg/kg, 45 mg/kg, and 60 mg/kg by 5 days post-injection (Fig. 1).

Quantification of OCT images revealed that the number of HRF significantly

increased in retinas of mice 5 days after

Fig. 1.

Fig. 1.

Optical Coherence Tomography Images of Retinas After Sodium

Iodate Contain Hyperreflective Foci. Optical coherence tomography (OCT) images

were acquired from mice at baseline (pre-sodium iodate [NaIO3]), and 1-, 3-,

5-, and 7-days post-injection (n = 4 per group). (A) Representative OCT images of

mice given varying concentrations of NaIO3 at different time points are

shown. Hyperreflective foci (HRF) (orange arrowheads) and thinning of the retina

were induced at NaIO3 doses

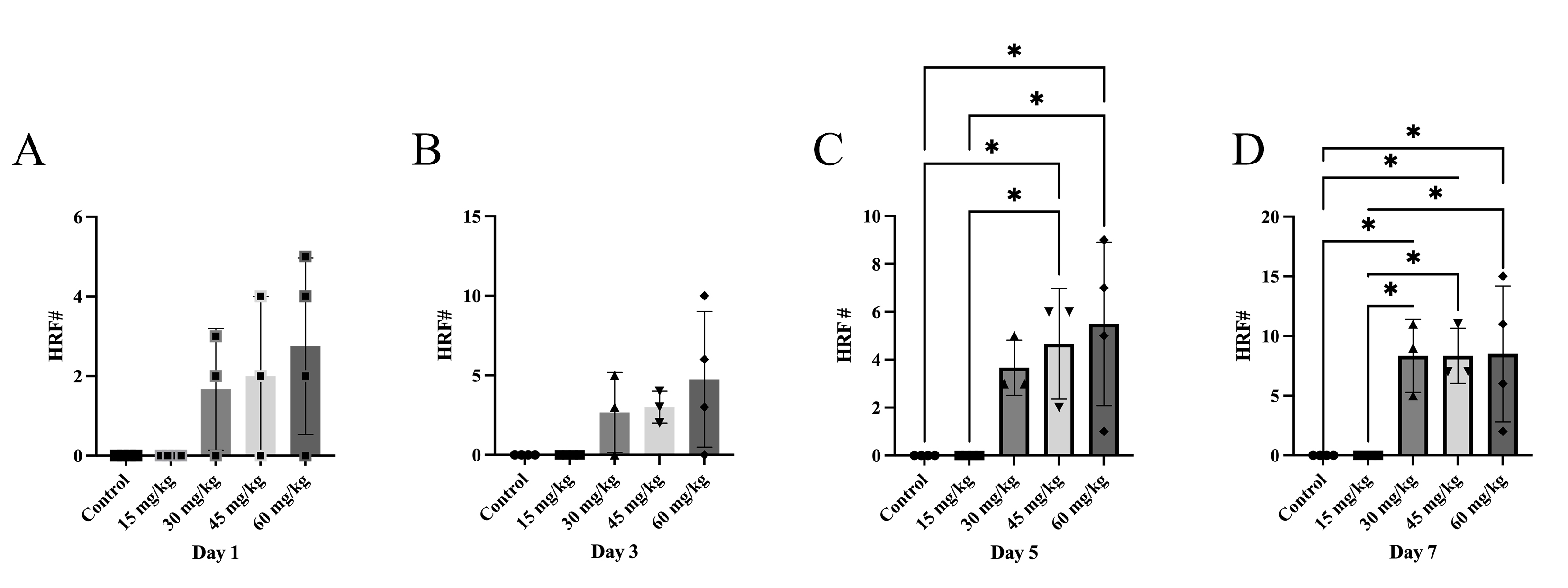

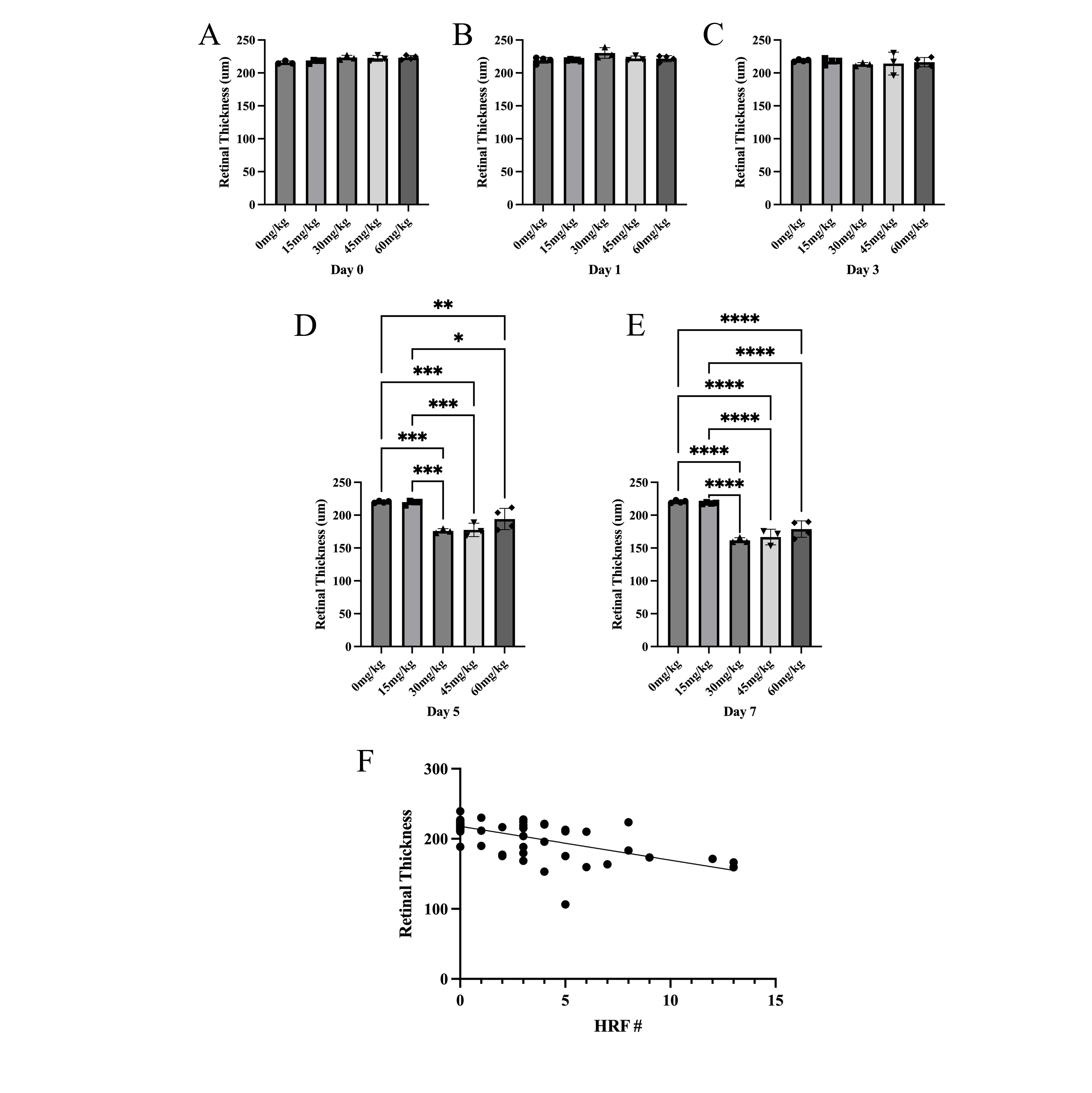

Fig. 2.

Fig. 2.

Sodium Iodate Increases the Number of Hyperreflective Foci over

Time. The retinal thickness and number of hyperreflective foci (HRF) were

manually quantified in OCT images, n = 4 per group. (A–D) Number of HRF 1, 3, 5,

and 7 days after NaIO3. There was a significant increase in the number of

HRF 5 and 7 days after NaIO3 with doses

Fig. 3.

Fig. 3.

Sodium Iodate Decreases Retinal Thickness over Time and

Correlation between the number of Hyperreflective Foci and Retinal Thickness.

(A–E) Total retinal thickness (µm) was measured 0, 1, 3, 5, and 7

days after NaIO3. The total retinal thickness was significantly less 5 and 7

days after NaIO3 with doses

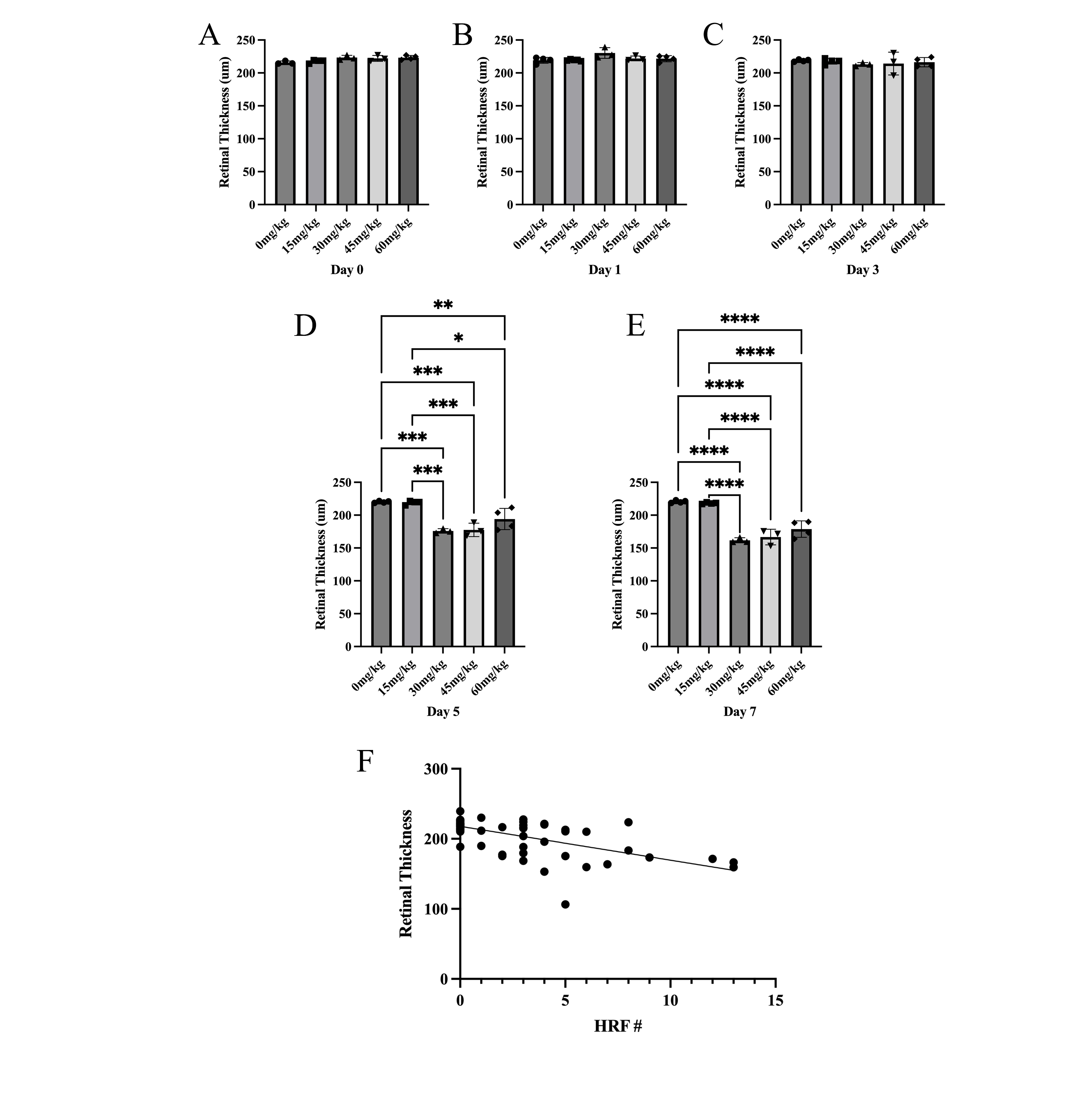

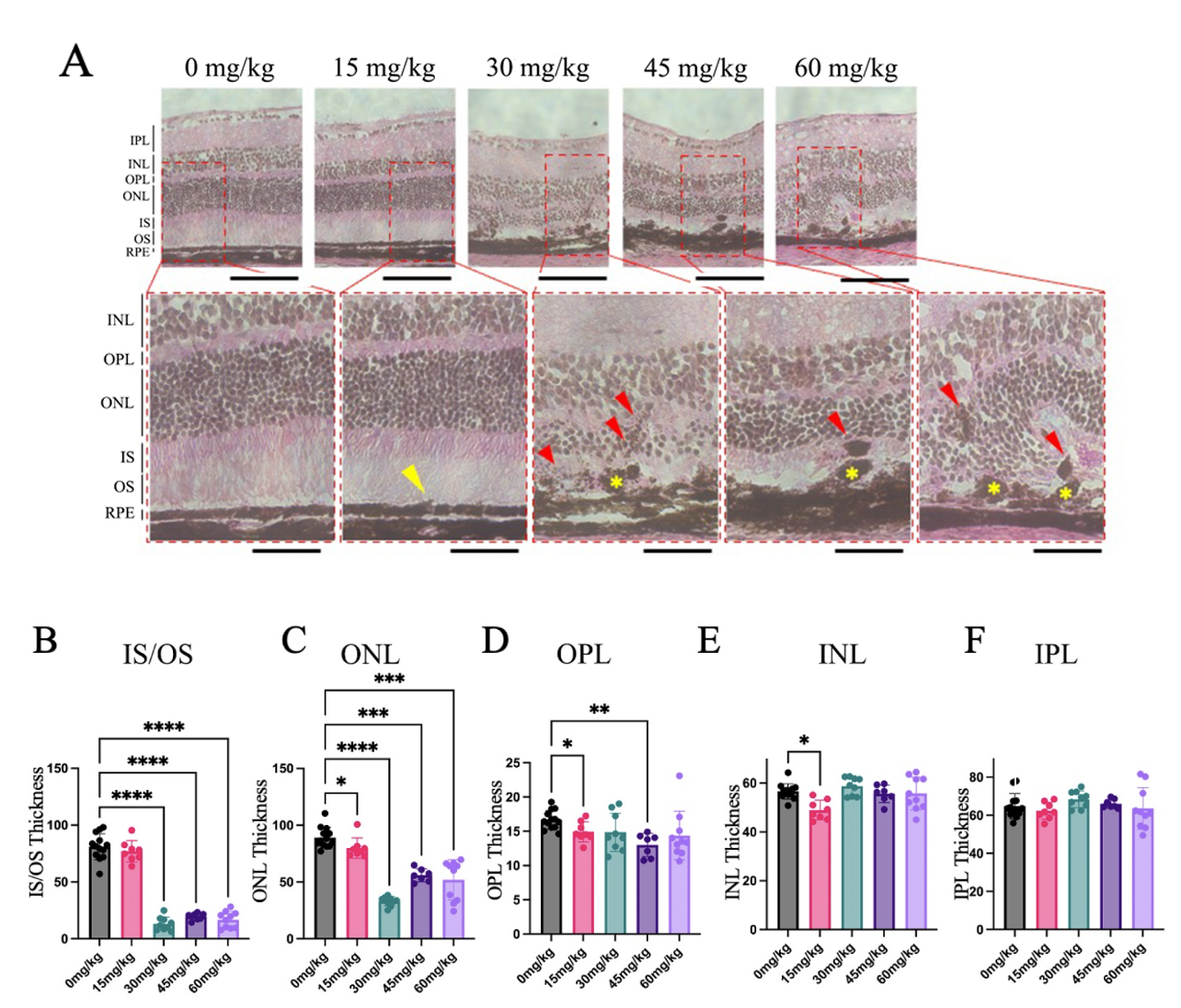

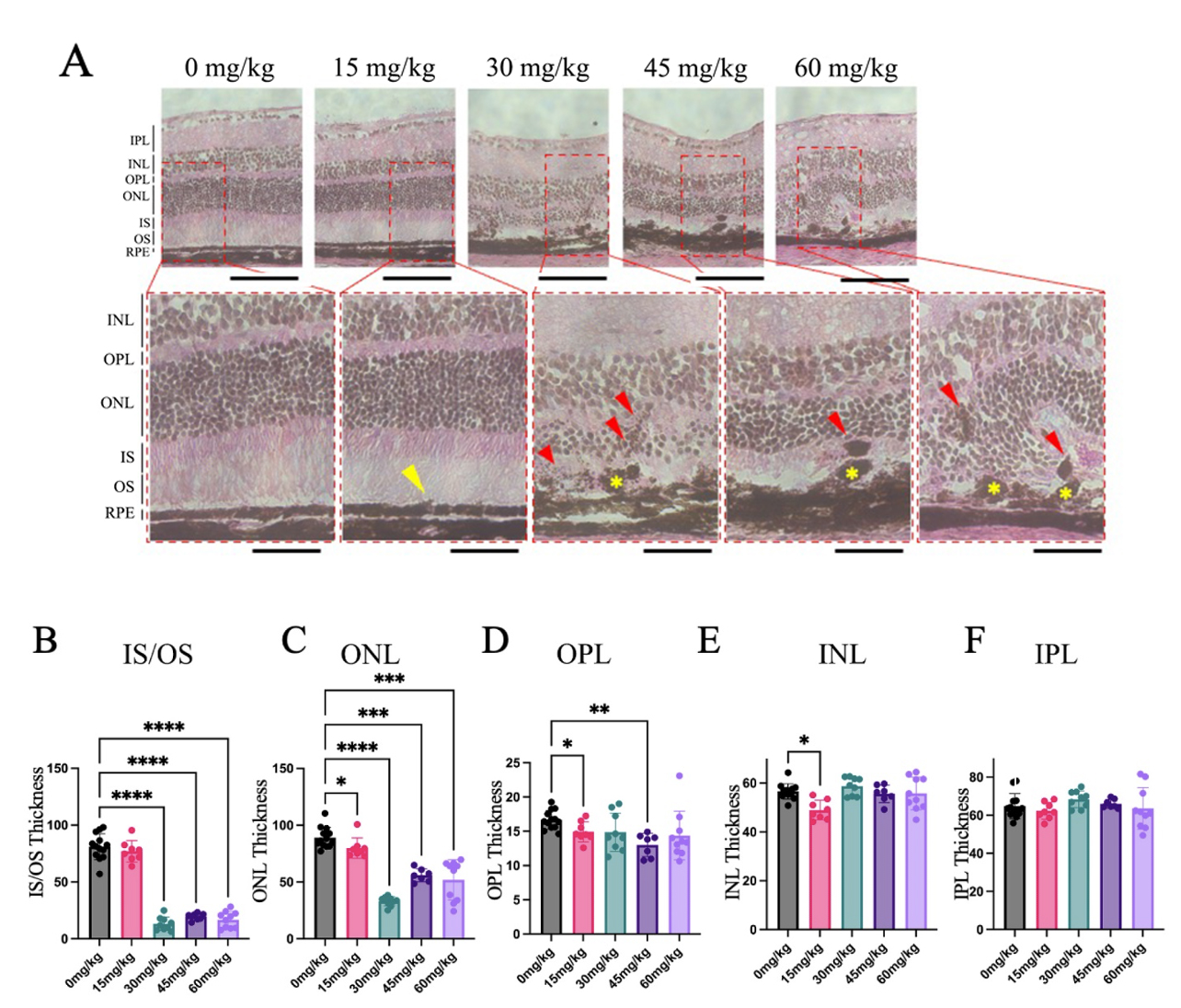

Eyes from mice 7 days after NaIO3 injection were sectioned for Hematoxylin & Eosin (H&E)

staining. Sections from mice given the vehicle contained no pigmented

abnormalities and the RPE layer was smooth and continuous, while sections from

groups given

Fig. 4.

Fig. 4.

H&E Sections Revealed Pigmented Anomalies and Distorted Retinal

Morphology Seven Days after Sodium Iodate Injection. Cross-sections of mouse

retinas were collected and stained using H&E, 7 days after NaIO3 injection

(n = 4–5 per group). (A) Subtle changes in RPE morphology were noted in the 15

mg/kg NaIO3 group (yellow arrowhead). The RPE was discontinuous in mice

given 30, 45, and 60 mg/kg NaIO3 (yellow asterisk), and abnormal retinal

pigment epithelium (RPE) layer structure is highlighted, and pigment

abnormalities appeared within the outer retina (red arrowheads). Other

abnormalities included folding of the nuclear layers and loss of photoreceptor

outer segments. (B–F) The thickness of the IS/OS, ONL, and OPL layers was

significantly less in mice given NaIO3 compared to the control group, whereas the IPL and INL experienced little or no significant changes (Data

expressed as mean

There was a significant reduction in the thickness of the inner segments/outer

segments (IS/OS) in groups given

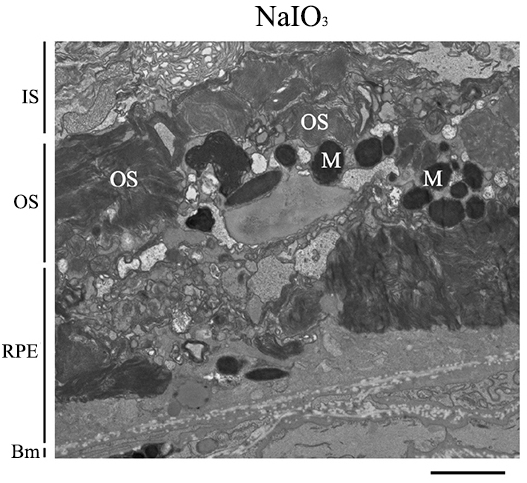

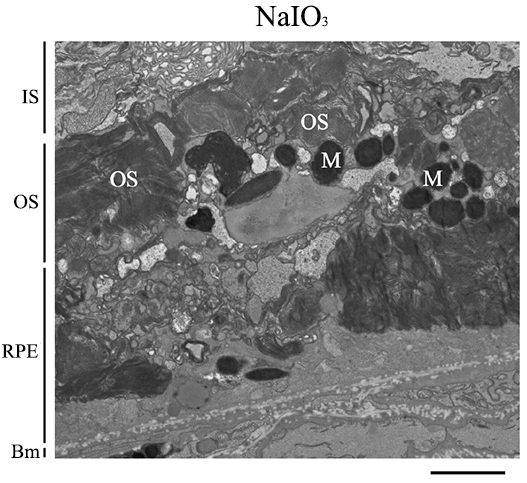

TEM images of mouse retinas were collected 7 days post-NaIO3 injection. The RPE cells of the NaIO3 mice had abnormal morphology; specifically, the microvilli of the RPE cells were absent and the basal infoldings had deteriorated in the NaIO3 retinas. The basal infoldings were also missing from some areas, and, when present, appeared smaller than in controls (Fig. 5).

Fig. 5.

Fig. 5.

Sodium Iodate Alters Retinal Pigment Epithelium Anatomy and Organization. Representative transmission electron microscope (TEM) image of the RPE layer of mice 7 days after 60 mg/kg of sodium iodate (NaIO3) (n = 3 per group). The basal infoldings of the retinal pigment epithelium (RPE) are absent, and the microvilli of the RPE are not seen. The RPE layer is disorganized and generally unrecognizable. Bm, Bruch’s membrane; IS, inner segments; M, Melanin; OS, outer segments; RPE, Retinal pigment epithelium. Scale bar = 2 µm.

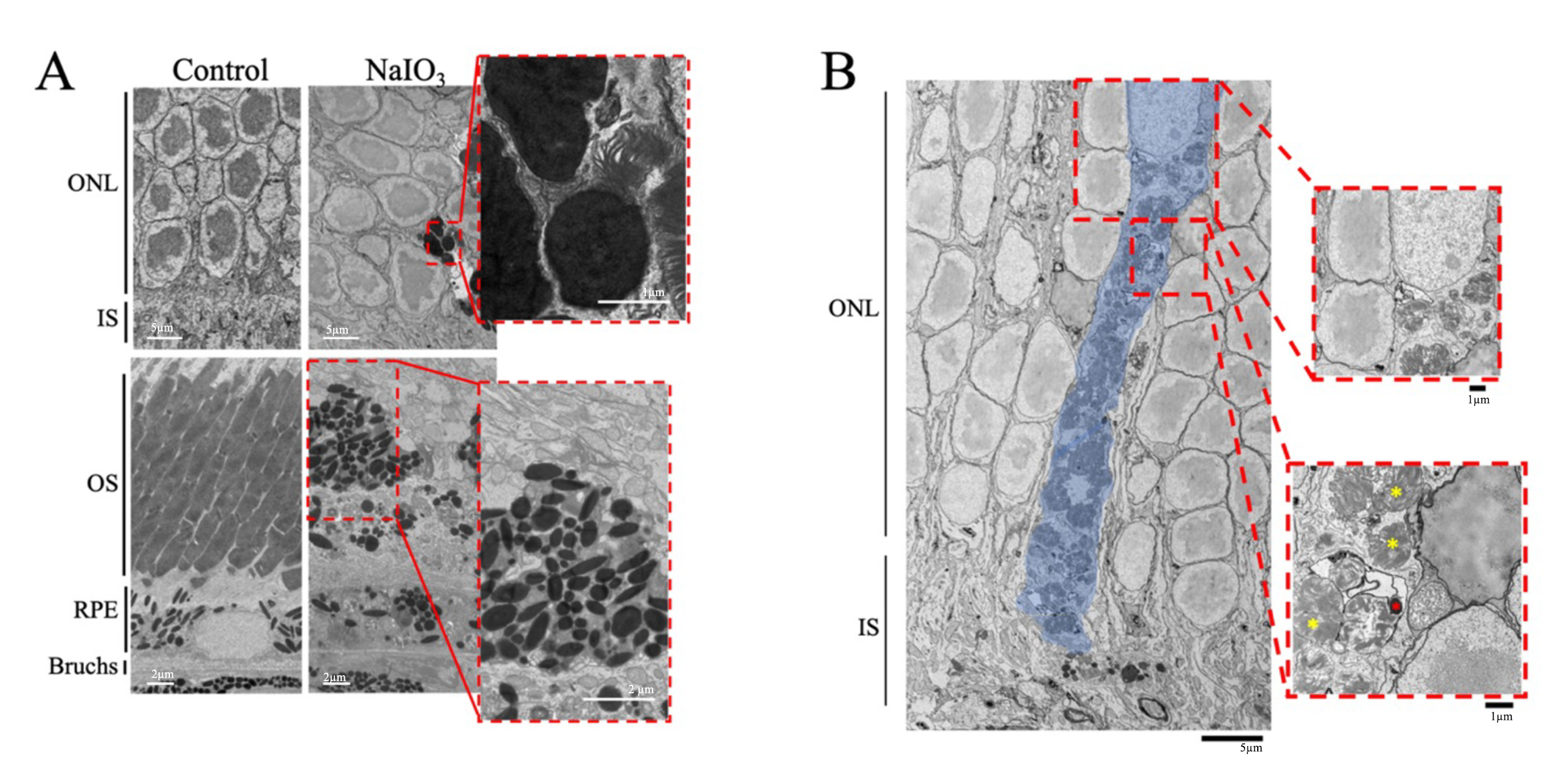

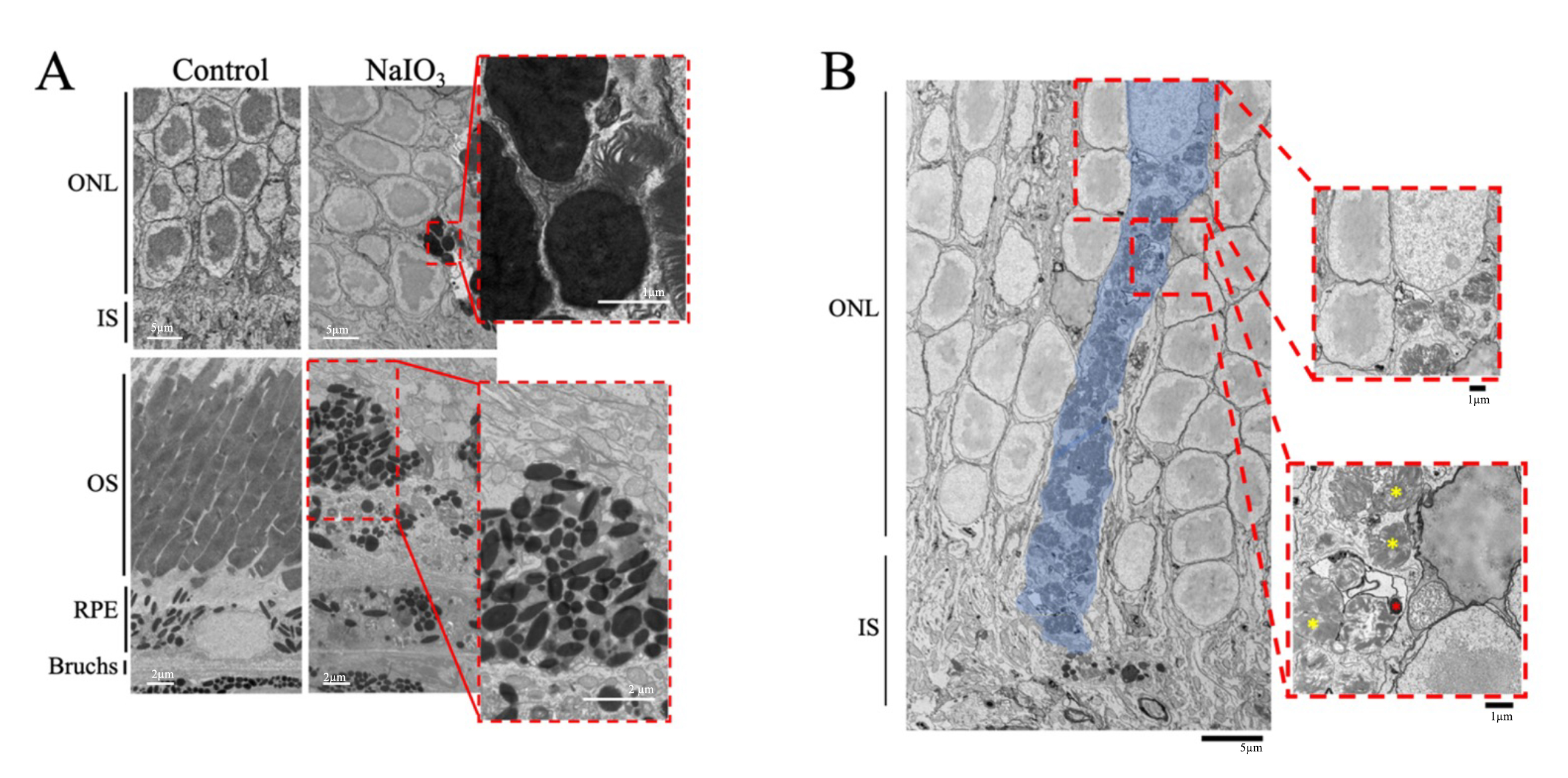

Pigmented abnormalities were observed in the ONL and the IS/OS layers of the retina of NaIO3-treated mice (Fig. 6A). The control retinas had intact photoreceptor outer segments and the RPE cells had basal infoldings along Bruch’s membrane and microvilli that extended into the OS layer. In contrast, the OS layer of the NaIO3-treated mice was degraded or missing in several regions. The OS and IS layers contained displaced electron-dense structures that resembled pigment, which was not seen in the control retinas. The size and abundance of the displaced electron-dense pigment varied and were noted in multiple layers of the outer retina, such as the photoreceptor OS and ONL layers. Along with the displaced electron-dense pigment, outer segment fragments were observed in the ONL. TEM of the NaIO3 retinas also revealed that the electron-dense pigment was contained intracellularly, based on its presence within the same plasma membrane shared with a nucleus (Fig. 6B). The image shows a displaced pigment-containing cell within the ONL (indicated by surrounding plasma membrane and photoreceptor nucleus). The morphology of the cell appeared abnormal compared to typical photoreceptor cells, suggesting that it originated outside the ONL. The cell also contained electron-dense pigment and partially digested photoreceptors.

Fig. 6.

Fig. 6.

Transmission Electron Microscopy Images Show Abnormal

Electron-Dense Structures in the Outer Retina. Representative transmission

electron microscope (TEM) of control mice and mice given sodium iodate

(NaIO3) are shown (n = 3 per group). (A) Electron-dense masses were

exclusively found in the RPE of the control mice. After concentrations of

NaIO3

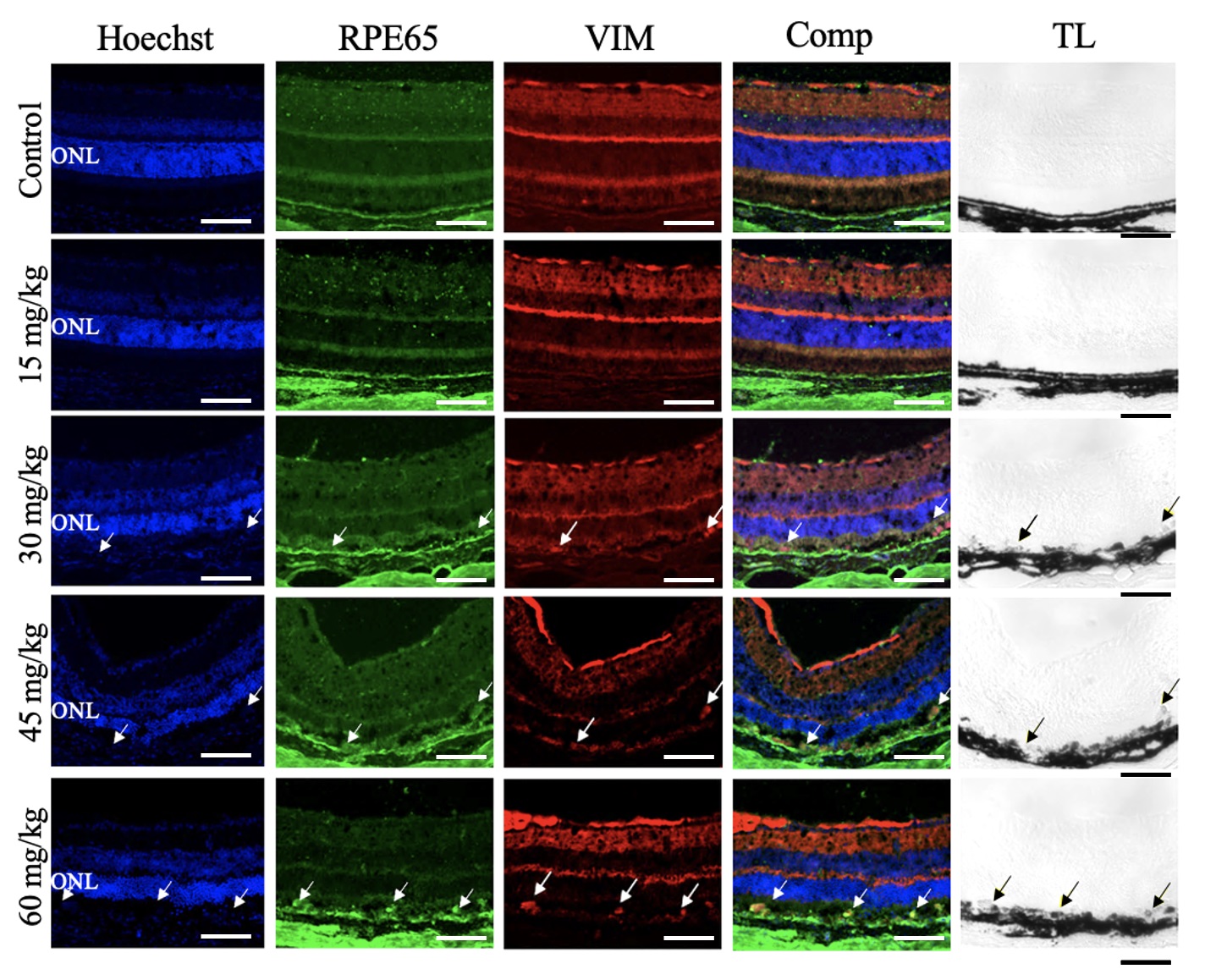

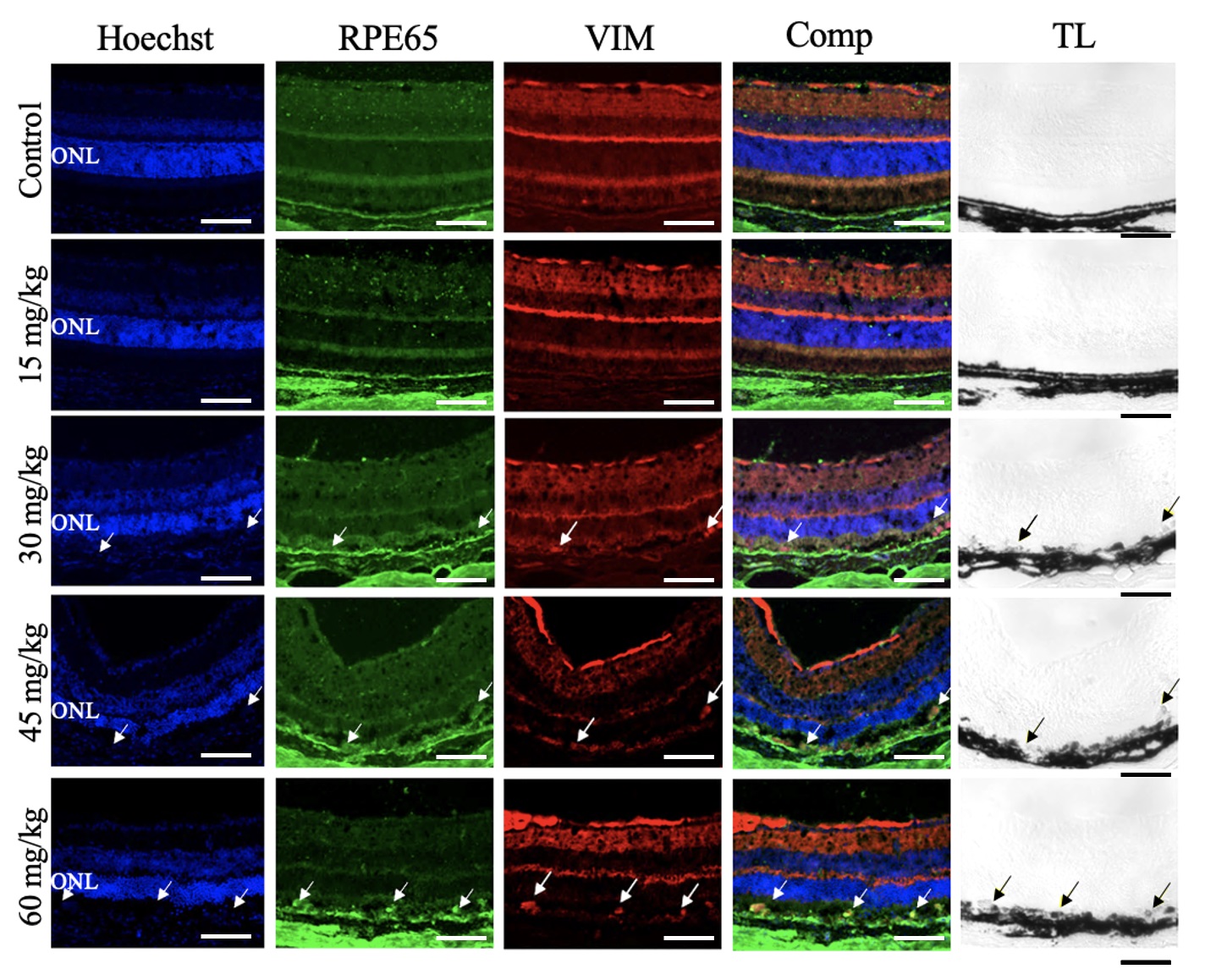

Retinal tissue was collected 7 days after NaIO3 injection and processed for

immunofluorescent labeling. Confocal imaging revealed that cells in the RPE layer

were positive for the RPE cell marker, RPE65, and the EMT marker, VIM, in the

retinas of mice treated with NaIO3

Fig. 7.

Fig. 7.

Sodium Iodate Induced Vimentin Expression in the Retinal Pigment Epithelium Layer. Representative confocal images of retinal sections from mice 7 days after NaIO3 injection, immunolabelled for RPE65 (green) and vimentin (VIM, red) and counterstained for nuclei with Hoechst (blue) (n = 4 per group). The overlay column (Comp) shows the merged image of all three fluorescent channels. The transmitted light channel (TL) is shown in the righthand column. First row: Control conditions. There was no VIM+ immunoreactivity in the RPE layer. Second row: NaIO3 15 mg/kg. No VIM+ immunoreactivity was detected in the RPE layer. Third row: NaIO3, 30 mg/kg. VIM+ and RPE65+ immunoreactivity colocalized (white arrows) and in the pigmented RPE layer (black arrows). Fourth row: NaIO3, 45 mg/kg. VIM+ and RPE65+ immunoreactivity colocalized (white arrows) in the pigmented RPE layer (black arrows). Fifth Row: NaIO3, 60 mg/kg. VIM+ and RPE65+ immunoreactivity colocalized abundantly (white arrows) in the pigmented RPE layer (black arrows). ONL, outer nuclear layer. Scale bar = 50 µm.

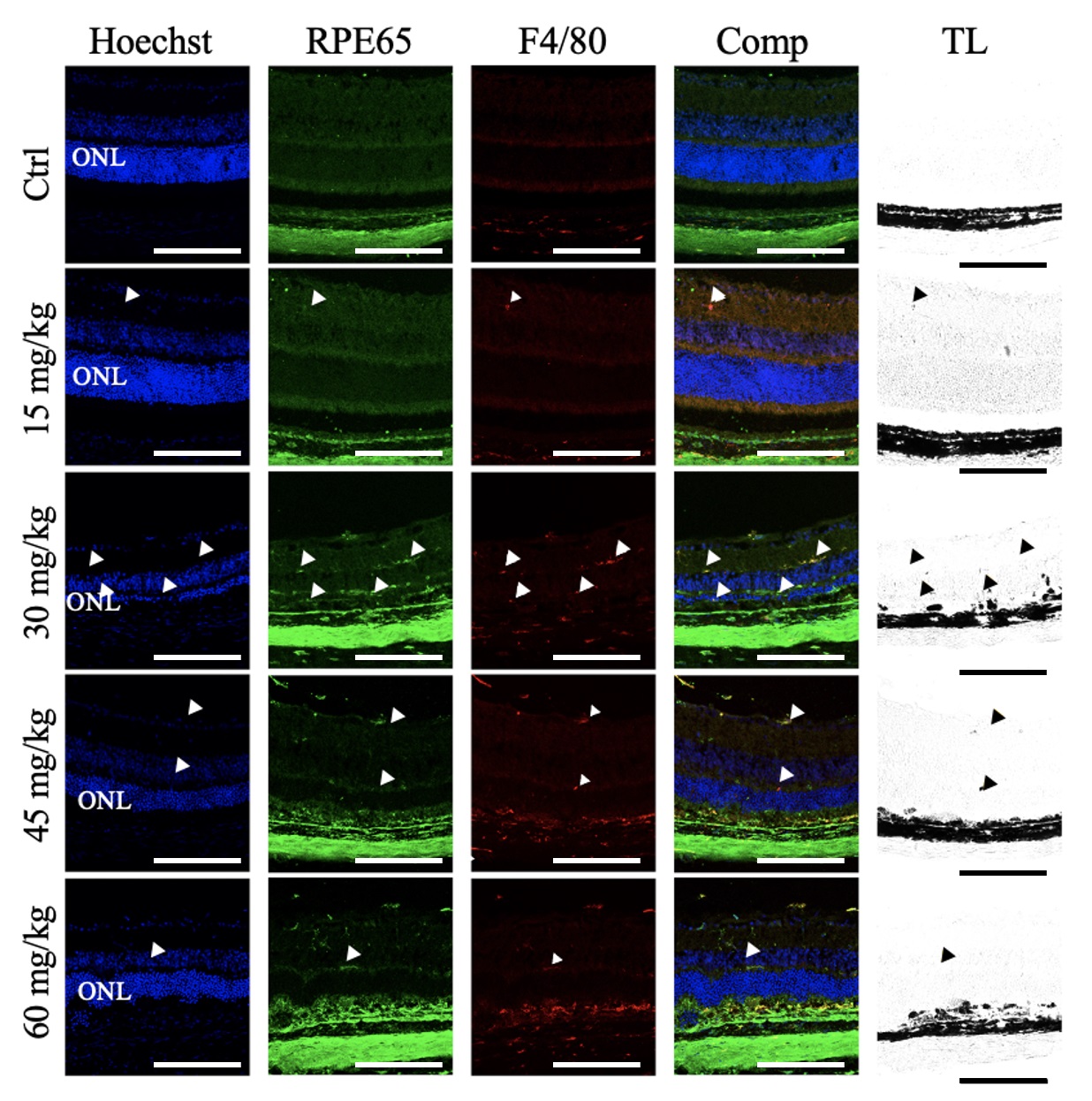

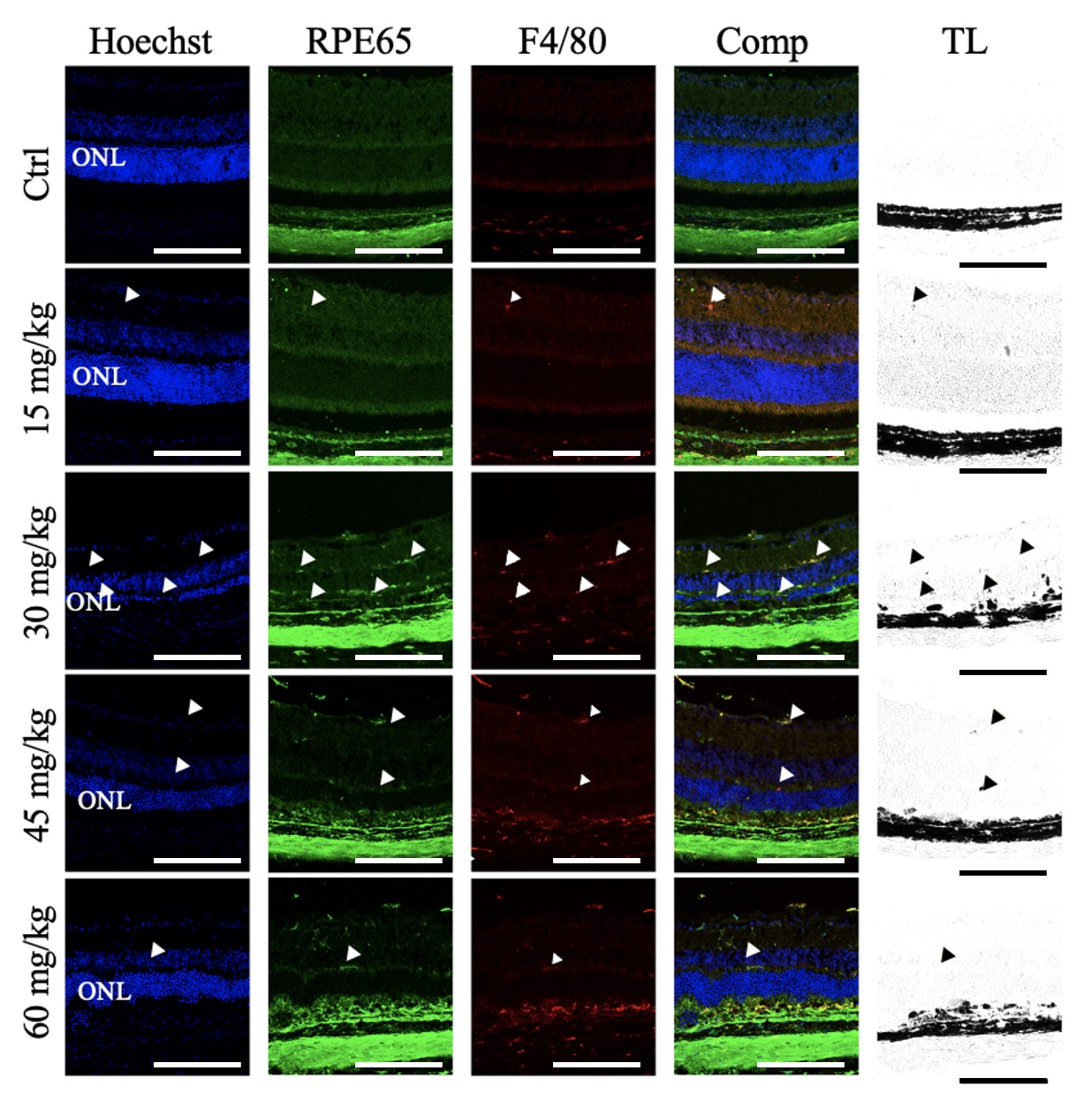

Retinal sections were also labeled for F4/80, a murine macrophage marker (Fig. 8). In the control retinas, F4/80 immunoreactive cells were detected in the choroid and sclera but not in the RPE and neural retina. Similarly, the retinas of mice given 15 mg/kg NaIO3 contained only sparse F4/80 immunoreactive cells in the neural retina. In mice given 30 mg/kg NaIO3, there was a greater abundance of F4/80 immunoreactivity in the neural retina, but only sparse F4/80+ immunoreactivity in the RPE layer. In the 45 mg/kg NaIO3- group, there was limited F4/80+ immunoreactivity in the neural retina and more in the RPE layer. Similar results were observed in the retinas of mice given 60 mg/kg NaIO3.

Fig. 8.

Fig. 8.

Sodium Iodate Increased F4/80+ Immunoreactivity in the Retinal Pigment Epithelial Layer and Neural Retina. Representative confocal images of retinal sections from mice 7 days after NaIO3 injection, immunolabelled for RPE65 (green) and F4/80 (red), and counterstained for nuclei with Hoechst (blue) (n = 4 per group). The overlay column (Comp) shows the merged image of all three fluorescent channels. The transmitted light (TL) channel is shown in the righthand column. F4/80+ immunoreactivity was observed in the choroid in all treatment groups. First row: Control. F4/80+ immunoreactivity was restricted to the choroid. Second row: NaIO3 15 mg/kg. F4/80+ immunoreactivity colocalized with RPE65 infrequently in the neural retina in addition to the choroid (white arrowheads) and corresponded to pigmented puncta (black arrowheads). Third row: NaIO3, 30 mg/kg. abundant F4/80+ immunoreactivity partially colocalized with RPE65 in the neural retina and RPE layer, in addition to the choroid (white arrowheads), and corresponded to pigmented puncta (black arrowheads). Fourth row: NaIO3, 45 mg/kg. F4/80+ immunoreactivity partially colocalized with RPE65 in the neural retina and RPE layer, in addition to the choroid (white arrowheads), and corresponded to pigmented puncta (black arrowheads). Fifth Row: NaIO3, 60 mg/kg. Occasional F4/80+ immunoreactivity partially colocalized with RPE65 in the neural retina and RPE layer, in addition to the choroid (white arrowheads), and corresponded to pigmented puncta (black arrowheads). ONL, outer nuclear layer. Scale bar = 50 µm.

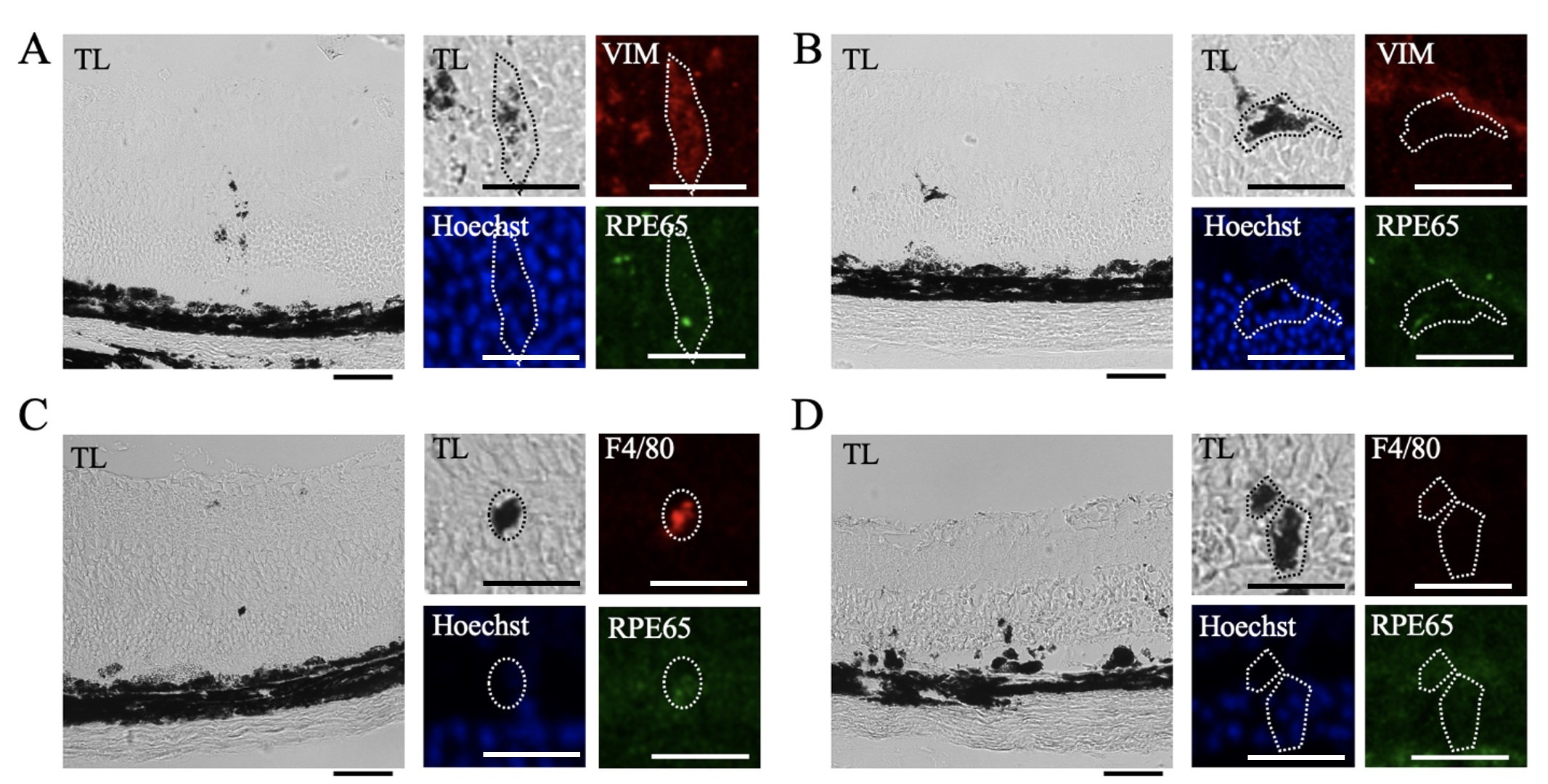

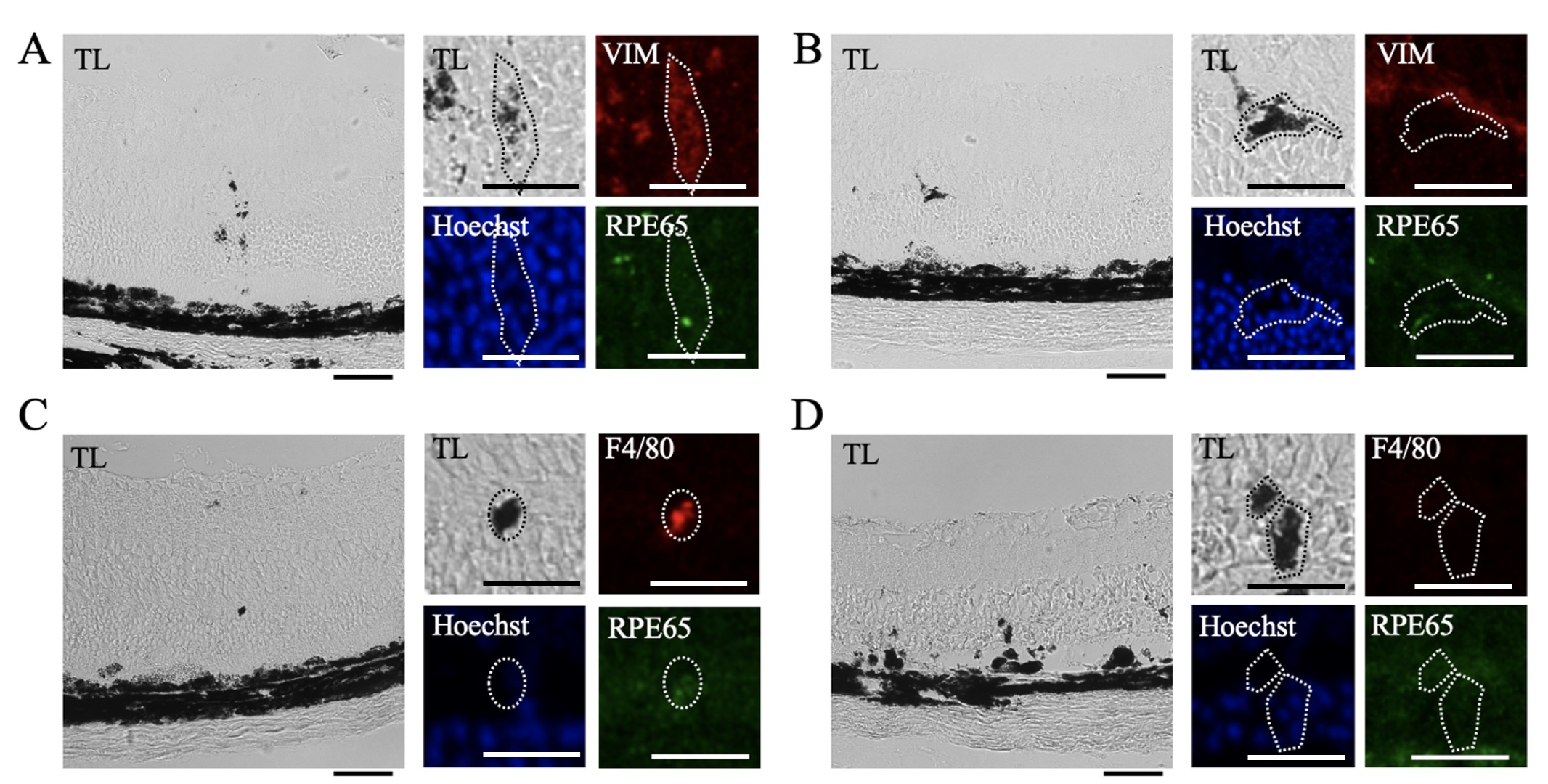

Pigment localized within the neural retina was observed by transmitted light imaging and corresponding confocal imaging of VIM, RPE65, and F4/80 immunofluorescence (Fig. 9). Pigment, VIM immunoreactivity, and RPE65 immunoreactivity colocalized in some places (Fig. 9A), but this was not uniform (Fig. 9B). Pigmented anomalies within the neural retina were also occasionally positive for F4/80+ immunoreactivity (Fig. 9C), but in most cases the pigment did not colocalize with F4/80 (Fig. 9D).

Fig. 9.

Fig. 9.

Heterogeneous Vimentin and F4/80 Immunoreactivity in Pigmented Anomalies. Pigmented anomalies were identified by transmitted light and compared to corresponding confocal images in retinal sections from mice 7 days after NaIO3 injection. Sections were immunolabelled for RPE65 (green) and F4/80 (red) or VIM (red), and nuclear counterstained with Hoechst (blue) (n = 4 per group). (A) Pigmented lesions identified in transmitted light (TL) images corresponded to Hoechst stain, some RPE65 immunoreactivity, and VIM immunoreactivity. (B) In other cases, pigmented lesions had Hoechst staining but no VIM or RPE65 immunoreactivity. (C) Pigmented lesions also partially corresponded to RPE65 and F4/80 immunoreactivity. (D) In other areas, pigmented lesions had Hoechst staining but no RPE65 or F4/80 immunoreactivity. Scale bar = 50 µm. Magnified scale bar = 25 µm.

The data presented here suggest a strong correlation between the NaIO3-induced retinal tissue loss and the abundance of HRF, as well as the extent of distortion of the RPE and outer retina. The abundance of HRF strongly correlated with retinal thinning, but HRF were present on day 1 and day 3, before the changes in retinal thickness, which only became significant on day 5. This suggests that increasing numbers of HRF may be predictive of photoreceptor cell death. Also, the electron microscope images suggest that NaIO3 caused electron-dense pigment to migrate into the retina as a component of cells that have undergone a morphological transformation. Pigmented anomalies within the neural retina colocalized with histological markers for RPE or macrophages, suggesting that HRF may be due to separate populations of migrating RPE cells and infiltrating immune cells although the majority of pigmented cells carried the RPE65 marker as well as vimentin, suggesting they were derived from the RPE and were undergoing EMT.

This study confirms that NaIO3 can be used to study the source and immunological characteristics of HRF, which are recognized as an important hallmark of AMD. The pathogenesis of AMD is poorly understood, but the current consensus is that oxidative stress in the RPE plays a significant role in their loss of function. Oxidative stress impacts multiple pathways in the RPE that result in injury and malfunction [23, 24, 25]. The body of research exploring the role of oxidative stress is extensive, and the selective impact of NaIO3 on the RPE, with the consequent formation of HRF correlating to tissue loss, suggests a strong link between the two. The data also add to the evidence that oxidative stress, regardless of modality, can induce EMT in RPE cells [26, 27, 28]. Therefore, the NaIO3 model offers an in vivo method to study the link between oxidative stress and EMT of RPE cells. HRF formation and distortion of the RPE layer are among the main characteristics of dry AMD, supporting the NaIO3 model as a valid tool for understanding clinical pathophysiology.

NaIO3 selectively damages the RPE cells at optimal doses [14], but previous studies have used concentrations of NaIO3 ranging from 10 mg/kg to 100 mg/kg with varying results [2, 5, 6]. Recent work shows that different concentrations of NaIO3 can yield results that vary by age and gender [15]. The retinas of older mice were more susceptible to NaIO3-induced injury when compared to younger mice of the same gender. Young female mice also had less injury compared to male mice of the same age. The distribution of retinal damage differed between the older male and female mice, with the male mice having a majority of no injury or widespread injury at 25 mg/kg and female mice having a majority of widespread retinal injury [15]. Older mice were more susceptible to NaIO3-induced retinal injury, which mirrors the clinical situation where age is a leading risk factor for AMD. NaIO3 also induces RPE dysfunction by initiating apoptosis and macrophage accumulation, resulting in photoreceptor injury [29, 30]. This damage is accompanied by thinning of the outer and inner segments of the photoreceptors and decreased visual acuity in mice [18].

The presence of HRF is the best predictor for AMD progression to the late-stage disease [31]. HRF have been analyzed using polarimetric imaging techniques to identify them. Polarimetry can differentiate the layers of the retina by measuring how the polarity of the light changes as it passes through each layer. Different mechanisms can cause changes in the polarization state: diattenuation, birefringence, and depolarization. Birefringent ocular tissues include the corneal stroma, sclera, and retinal ganglion cell (RGC) layer [32, 33, 34]. Depolarization can be found in tissue containing melanin, such as the iris, pigment-loaded macrophages, and the RPE layer [35]. HRF and the RPE layer have similar levels of hyperreflectivity detected by OCT and of depolarization on polarimetry [12]. Previous study of postmortem human tissue indicate that HRF are comprised of transdifferentiated RPE cells, although they do not account for all the HRF and the other pigmented cells in the neural retina. Some of the HRF in human AMD tissue are CD68+, CD163+, RPE65–, and CRALBP– suggesting they may have multiple origins [11]. Further immunological characterization of the HRF generated by NaIO3 in animals will determine the extent to which this model recapitulates the clinical condition.

There are numerous genetic models for dry AMD, that recapitulate different aspects of the disease. The carboxyethylpyrrole (CEP)-immunized mouse model relies on the addition of CEP to activate the immune system and produce AMD-like findings. CEP is a fragment of an easily oxidized fatty acid that is abundant in the retina and can act as a biomarker for oxidative stress and neovascularization [36, 37]. This model also develops a thickening of Bruch’s membrane [38]. A significant portion of other AMD models are genetically engineered mice, such as complement factor H (CFH) and apolipoprotein E (APOE) knock-out mice. The APOE knock-out develops abnormal vesicles in Bruch’s membrane [39]. Aged mice that expressed human ApoE2 on a high-fat diet show a more severe phenotype with sub-RPE deposits, hyper- and hypo-pigmentation, and thickening of Bruch’s membrane [40]. CFH-deficient mice have thinning of Bruch’s membrane, disorganized photoreceptors, and C3 accumulation [41]. Some of the mutations are linked to non-AMD retinal diseases, such as Abca4 knock-out (SLMD), S156C TIMP3 knock-in (SFD), and the R345W fibulin-3 knock-in (DHRD) mouse models, all of which present with different aspects of the disease. There are also SOD1 knock-out mice that develop drusen-like deposits, RPE vacuolization, and tight junction issues due to the loss of oxidative stress protection [42]. Despite the many different models available to study different aspects of AMD, NaIO3 is capable of rapidly and reliably inducing HRF and mimicking intermediate AMD with retinal thinning and RPE layer thickening. Recently, a genetic model of AMD involving an inducible knock-out of GPX4 has also been able to produce HRF in the retina and increase oxidative stress within the retina [43]. Although this model also recapitulates HRF, the NaIO3 model is an easily accessible and titratable trigger for HRF production. As such, the NaIO3 model is an essential addition to the tools needed to understand the disease mechanisms involved in early and intermediate AMD.

As with any animal model, NaIO3 does have some limitations. The mouse and human retina differ in various ways; most critically the mice lack a macula, which may be predisposed to degeneration in humans due to its high photoreceptor density, RPE phagocytic load, and a thinner Bruch’s membrane [44, 45, 46]. Mouse retinas, however, are similar to the human macula in that the photoreceptor density is higher in the center, and consequently have a high RPE phagocytic load, as well as a relatively thinner Bruch’s membrane [47]. In the present study, the location of injury was heterogeneous, suggesting that this model may not be the ideal option for determining the properties of the macular region that lead to preferential injury in that area in AMD. Although NaIO3 rapidly induced HRF in the retina, the damage varied within treatment groups. A recent study indicated that gender impacts the extent of NaIO3-induced retinal injury and concluded that young female mice had the least variability in response to NaIO3 [15]. Since only young adult males were used in our study it is possible that our findings may not fully generalize to females or other ages. Using young female mice may impact the results and will be considered for future experiments. Another explanation for the lack of area preference for the effects seen in this model is that the visual capacity of mice is different from humans. Mouse retinas are rod-dominant and human retinas are cone-dominant and have differing metabolic demands. Despite these differences, mice are an adequate animal model because the primary lesion of AMD is considered to occur within the RPE cells [44, 48, 49]. Some similarities between the human macula and murine central retinas imply that the findings may be comparable, and the results gleaned from NaIO3 in mice and other animals will contribute to a better understanding of HRF formation in AMD.

The purpose of this study was to study HRF formation in the NaIO3 model of AMD. Using multiple imaging modalities, we have shown that NaIO3-induced HRF have some similarities with HRF found in AMD, and HRF formation is predictive of tissue loss in the outer retina. The HRF in the present study were occasionally positive for macrophage markers, but also had histological characteristics consistent with epithelial to mesenchymal transition, such as VIM immunoreactive areas containing pigment. However, these findings did not apply to all the pigmented bodies, suggesting that there may be other cells and/or processes involved, including immune cell infiltration. Despite this possibility, our results support recent data suggesting that some HRF are migrating RPE cells [11]. This model is useful for studying the processes involved in HRF development. Much of the research using this model focuses on the impact of NaIO3 on the neural retina and the RPE. While these aspects of the model are important to study, we show that it can also be used to generate HRF and that the number of HRF correlates with the NaIO3-induced retinal loss. This model can be used to determine the biological processes that initiate RPE migration and its role in neural retinal degeneration. Future studies are required to elucidate how RPE oxidative stress pathways are linked to HRF development.

AMD, age-related macular degeneration; ANOVA, analysis of variances; AREDS2, age-related eye disease study 2; H&E, hematoxylin and eosin; HRF, hyperreflective foci; IHC, immunohistochemistry; INL, inner nuclear layer; i.p., intraperitoneal; IPL, inner plexiform layer; IS, inner segments; NaIO3, sodium iodate; NDS, normal donkey serum; OCT, optical coherence tomography; OPL, outer plexiform layer; OS, outer segments; ONL, outer nuclear layer; PBS, phosphate-buffered solution; PFA, paraformaldehyde; RGC, retinal ganglion cell; RPE, retinal pigment epithelium; RT, room temperature; SEM, standard error mean; TEM, transmission electron microscopy; VIM, vimentin; WT, wild-type.

Data will be available upon request to any interested parties.

JG, SG, AB, and JS designed the research study. Initials JG, SG, EK, GC, YD, and YZ performed the research. Initials SG, HC, AB, and YZ provided help and advice on improving imaging techniques and quantifying data. Initials JG, EK, GC, and YD analyzed the data. Initials JG wrote the manuscript. All authors contributed to editorial changes in the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript. All authors have participated sufficiently in the work and agreed to be accountable for all aspects of the work.

This study did not include human participants, human data or human tissue. The Pennsylvania State College of Medicine Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee reviewed the protocol of the presented work using laboratory mice, approved of the experimental plan and consented to the data presented in this work being published (Approval number PRAMS201646990).

We would to thank Bennett and Inez Chotiner for their support of our research. We would like to acknowledge the Transmission Electron Microscopy and Light Microscopy cores at Pennsylvania State for providing guidance to obtain the most rigorous imaging possible. We also would like to acknowledge our fellow research professors at Pennsylvania State for providing access to their resources and input throughout the development of this project.

This work was funded by the Bennett and Inez Chotiner Early Career Professorship in Ophthalmology endowment (JMS).

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Supplementary material associated with this article can be found, in the online version, at https://doi.org/10.31083/j.fbl2911380.

References

Publisher’s Note: IMR Press stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.