1 Intensive Care Unit, The Affiliated People’s Hospital of Fujian University of Traditional Chinese Medicine, 350004 Fuzhou, Fujian, China

†These authors contributed equally.

Abstract

LncRNA taurine-upregulated gene 1 (TUG1) can regulate vascular endothelial cell injury, a critical mechanism in treating hemorrhagic shock and fluid resuscitation (HS/R). Therefore, this study explored the influence of TUG1 in HS/R.

An in vivo rat model of ischemia-reperfusion (I/R) injury post-HS/R and an in vitro model of oxidative stress injury in rat cardiomyocyte cell line (H9C2) were constructed. In vivo, we silenced TUG1 and quantified its expression along with inflammatory factors through quantitative reverse transcription polymerase chain reaction (qRT-PCR), mean arterial pressure (MAP) detection and blood gas analysis. Myocardial functional impairment was assessed via Triphenyl-2H-Tetrazolium Chloride (TTC), Hematoxylin and eosin, and Terminal deoxynucleotidyl transferase-mediated deoxyuridine triphosphate nick end labeling (TUNEL) stainings. Oxidative stress level in rat serum was measured. In vitro, we examined the changes of cell viability, apoptosis, oxidative stress levels, inflammatory factor secretion and nuclear factor-κB (NF-κB)/p65 expression by 3-(4,5-dimethylthiazol-2-yl)-2,5-diphenyltetrazolium bromide (MTT), flow cytometry, Enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) and Western blot.

TUG1 level was elevated in rats of I/R model caused by HS/R. TUG1 silencing ameliorated the decline in MAP, acid-base imbalance and myocardial tissue damage, and suppressed oxidative stress and inflammatory factor levels in model rat. TUG1 silencing enhanced viability, impeded apoptosis, and reduced oxidative stress, inflammatory factor contents and NF-κB/p65 expression in H2O2 treated H9C2 cells.

TUG1 participates in regulating oxidative stress damage and inflammation induced by HS/R.

Keywords

- hemorrhagic shock

- fluid resuscitation

- long non-coding RNA TUG1

- NF-κB

- oxidative stress

- inflammation

Hemorrhagic shock (HS) refers to the pathophysiological process of acute blood

or serum loss caused by various reasons, resulting in reduction of effective

circulating volume and cardiac output, insufficient tissue perfusion, metabolic

acidosis and functional impairment, and systemic inflammation [1, 2, 3]. Despite the

major advances in resuscitation treatment and intensive care, HS still threatens

the life of trauma patients worldwide [4]. Fluid resuscitation can effectively

mitigate severe HS by ensuring the blood perfusion of important organs in a short

time [5]. However, recent clinical study has found without effective

hemostasis, large-dose fluid resuscitation can produce many adverse reactions,

such as weakened tissue oxygen supply resulting from reduced hemoglobin

concentration, coagulation dysfunction, reperfusion injury, and immune

dysfunction [6]. Notably, hemorrhagic shock and fluid resuscitation (HS/R) may

trigger oxidative stress damage [7, 8]. Moreover, reactive oxygen species (ROS)

activates activating nuclear factor-

Reportedly, long non-coding RNA (lncRNA) greatly impacts the process of

ischemia/reperfusion injury [10]. By high-throughput RNA sequencing analysis, Lin

et al. [11] discovered 851 significantly up-regulated lncRNAs and 1533

obviously down-regulated lncRNAs in rat heart tissues with severe HS-induced

ischemia-reperfusion (I/R) injury. LncRNA taurine-upregulated gene 1

(TUG1) is located on chromosome 22q12.2, and has many biological

functions. Sun et al. [12] reported that TUG1

can alleviate renal ischemia/reperfusion injury by regulating ferroptosis. Wang

et al. [13] revealed that TUG1 can be mediated by hypoxia

inducible factor 1 subunit alpha (HIF-1

Since TUG1 acts a part in HS/R with an obscure mechanism, this research illustrated the influence of TUG1 on HS/R.

36 Sprague–Dawley rats (male, 8–9 weeks old, 300–360 g; Hangzhou Medical

College, Hangzhou, China) were housed under specific

pathogen-free conditions at animal laboratory (20

Establishment of severe HS rat model referred to an existing study [11]. After being fasted for 12 h, the rats were anesthetized by intraperitoneal injection of 45 mg/kg sodium pentobarbital (P-010, Merck, Darmstadt, Germany), the femoral artery of which was separated and cannulated with polyethylene catheter. Subsequently, their left femoral artery was connected to a multi-channel physiological signal acquisition and processing system (BIOPAC, Goleta, CA, USA) to detect blood pressure (mean arterial pressure, MAP) and heart rate, while the right femoral artery was employed to control hemorrhage. The left jugular vein was cannulated with a PE-50 tube for fluid resuscitation. The total blood loss rate was controlled at 45%, and the bleeding time was controlled within 1 h. The blood flowing out of the left femoral artery was then perfused back into the rats within 40 min.

Based on previous description [14, 15], rats were given subcutaneous injection of phosphate buffer saline (PBS) (A610100, Sangon, Shanghai, China) containing small interfering RNA targeting TUG1 (siTUG1, 5′-GCAGUAAUUGGAGUGGAUATT-3′, siBDM0001, Ribobio, Guangzhou, China) or its negative control (siNC, 5′-UUCUCCGAACGUGUCACGUTT-3′, siN0000001-4-200, Ribobio, Guangzhou, China) 2 h before surgery. After 6 h of resuscitation, the collected blood samples were centrifuged (3000 g, 15 min), followed by serum storage (–80 °C). The rats were euthanized by an overdose of pentobarbital sodium (200 mg/kg, iv) for heart tissue collection.

Six groups were designed based on experimental animals (Sham, Model, Sham + siNC, Sham + siTUG1, Model + siNC and Model + siTUG1) (6 mice/group). The rats in Sham group experienced anesthesia and surgery, but without bloodletting.

Anticoagulated whole blood samples were collected 2 hours after resuscitation, in which bicarbonate (HCO3–) and lactate content were determined employing a Hemogas analyzer (ABL800 FLEX, Radiometer, Copenhagen, Denmark).

The heart was quickly taken out, and repeatedly rinsed with normal saline. Heart

tissue was immediately frozen in a –20 °C refrigerator for 20 min, and then cut

into 4–5 sections (thickness of 2 mm). Sections were stained

with 1.5% TTC (15 min; A610558, Sangon, Shanghai, China), and fixed with 10%

neutral formaldehyde solution (E672001, Sangon, Shanghai, China). After the

stained sections were imaged under a fluorescence microscope, their infarct area

(white area) and non-infarcted region (red area) were analyzed

and calculated through AlphaEaseFC image processing software

(version 4.0, Alpha Innotech, San Leandro, CA, USA). Infarct size (%) = infarct

area/total area

Heart tissues experienced fixation (10% neutral formalin solution, BL-G001,

Senbeijia, Nanjing, China), paraffin embedding and sectioning

into 5-µm-thick slices. The deparaffinized and hydrated

slices underwent color development exploiting H&E kit (BP-DL001, Senbeijia,

China), followed by dehydration and transparentization. After sealing with

mounting medium (SBJ-0700, Senbeijia, China), the degree of damage to the rat

myocardial tissue was observed (microscope, AE2000, Motic,

Xiamen, China, 100

TUNEL Apoptosis Detection Kit (C1086, Beyotime, Shanghai, China) was used for

TUNEL staining of heart tissue. After being deparaffinized, hydrated, treated

with proteinase K and washed, the section was incubated with TUNEL solution (60

min), and reacted with 4′,6-Diamidino-2-phenylindole (DAPI) solution (C1002,

Beyotime, China) for nuclear staining. Following dehydration, transparentization

and mounting, TUNEL-positive cells were finally observed (fluorescence

microscope, 200

MDA content in rat serum was determined by MDA detection kit (SBJ-R0007, Senbeijia, China). Briefly, the standard solution was diluted into different concentrations in preparation for the subsequent standard curve plotting. Afterwards, the diluted serum was added to an antibody-coated 96-well plate, and cultured with different reagents. Following absorbance measurement (450 nm, microplate reader, CMaxPlus, Molecular Devices, San Jose, CA, USA), MDA concentration detection was carried out based on the standard curve.

By means of GSH detection kit (BC1175, Solarbio, Beijing, China), the absorbance (412 nm) of the sample or reagent was detected, and GSH content in rat serum was calculated according to the standard curve.

Using SOD detection kit (BC0170, Solarbio, China), the absorbance (560 nm) of the sample or reagent was quantified, followed by measurement of SOD content in rat serum or cell supernatant.

Rat cardiomyocyte cell line (H9C2, CL-0089, Procell, Wuhan, China) were soaked (37 °C, 5% CO2) in Dulbecco’s Modified Eagle’s Medium (30-2002, ATCC, Manassas, VA, USA) with 10% fetal bovine serum, 0.1 mg/mL streptomycin and 100 U/mL penicillin. H9C2 cells were tested negative for mycoplasma. H9C2 cells were validated by short tandem repeat (STR) profiling.

Post total RNA extraction (total RNA extraction kit, EZB-RN4, HiFunBio, Shanghai, China) from rat heart tissues or H9C2 cells, reverse transcription and qPCR were completed by One-Step qRT-PCR kit (AE341, TransGen Biotech, Beijing, China) using Real-Time PCR Detection system (CFX Connect, Bio-rad, Hercules, CA, USA). Data were dissected by 2-ΔΔCt method [16]. Glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase (GAPDH, for lncRNA and mRNA) functioned as an internal control. The details of primers are listed in Table 1.

| List of oligonucleotide sequences | 5′ |

| Primers for PCR | |

| R-TUG1 F | CTGCTGAAGTTGTTTGCCTGCTTAC |

| R-TUG1 R | AATTGGGCACGAGAGGCTGAAAG |

| R-GAPDH F | TGCCACTCAGAAGACTGTGG |

| R-GAPDH R | TTCAGCTCTGGGATGACCTT |

| R-TNF- |

GTCGTAGCAAACCACCAAG |

| R-TNF- |

GTCGCCTCACAGAGCAAT |

| R-IL-6 F | GAGTTGTGCAATGGCAATTC |

| R-IL-6 R | ACTCCAGAAGACCAGAGCAG |

Abbreviation: F, Forward; R, Reverse; PCR, polymerase chain reaction;

TUG1, taurine-upregulated gene 1; GAPDH,

Glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase; TNF-

SiTUG1 (siG151012045709-1-5,

5′-GCAGUAAUUGGAGUGGAUATT-3′) and siNC (siN0000002-1-5,

5′-UUCUCCGAACGUGUCACGUTT-3′) were purchased from

Ribobio (China). The oligonucleotide sequences above were

transfected into the cells in a 6-well plate (4

In line with a previous description [17], an oxidative stress injury cell model was set up based on 500 µM H2O2 treated H9C2 (24 h). H9C2 were assigned into 4 groups: Control (normal culture), H2O2, H2O2 + siNC and H2O2 + siTUG1 groups (4-h treatment with 400 µM H2O2 after siNC/siTUG1 transfection or not).

With 3-(4,5-dimethylthiazol-2-yl)-2,5-diphenyltetrazolium bromide (MTT) assay

kit (SBJ-0191, Senbeijia, China), treated cells (3

Using an Annexin V-FITC Apoptosis Detection Kit (CA1020, Solarbio, China),

treated cells (1

LDH release in different groups was evaluated by LDH Cytotoxicity Assay Kit

(C0017, Beyotime, China). After different cell treatments, cells in each well

were cultivated with 60 µL LDH detection working solution (30 min).

Absorbance (490 nm) was detected with a multiple detection reader for the

calculation of LDH content. LDH (U/mL) = (sample hole absorbance – background

blank control hole absorbance)/(standard tube absorbance – standard blank tube

absorbance)

Tumor necrosis factor (TNF)-

Total protein extracted (ExKine™ Total Protein Extraction Kit, KTP3006, Abbkine, Wuhan, China) [18] experienced quantification, separation, electrophoresis, transference to membrane and blocking (5% bovine serum albumin, BSA). The membrane was probed with the primary antibodies (GAPDH as an internal control), rinsed off, and reacted with secondary antibodies. The details of antibodies are exhibited in Table 2. Protein band visualization was conducted by enhanced chemiluminescence (ECL) Western Blotting Substrate (W028-2-1, Nanjing Jiancheng Bioengineering Institute, Nanjing, China) on a gel imaging system (610020-9q, QinXiang, Shanghai, China), after which the band intensity was calculated by ImageJ2x V2.1.4.7 (Rawak Software, Stuttgart, Germany). Relative protein expression levels = (gray value of protein band)/(gray value of GAPDH band). Data were normalized to Control group.

| Antibody | Catalog | Molecular weight (kDa) | Dilution | Manufacturer (UK) |

| NF-κB p65 (phospho S536) | ab239882 | 65 | 1/1000 | abcam |

| NF-κB p65 | ab16502 | 64 | 1/2000 | abcam |

| GAPDH | ab8245 | 37 | 1/5000 | abcam |

| Goat anti rabbit | ab205718 | — | 1/10,000 | abcam |

| Goat anti mouse | ab6789 | — | 1/10,000 | abcam |

NF-κB, nuclear factor-κB.

Data represented as mean

TUG1 expression level in rat heart tissue was much higher in model

group than Sham group (Fig. 1A, p

Fig. 1.

Fig. 1.

Effects of TUG1 silencing on MAP and metabolic acidosis in rat

model with HS/R. Construction of 6 groups based on experimental animals (6

mice/group): Sham (receiving anesthesia and surgery without bloodletting); Model

(receiving anesthesia, surgery and bloodletting); Sham + siNC (receiving

subcutaneous injection of siNC 2 h before anesthesia and surgery without

bloodletting); Sham + siTUG1 (receiving subcutaneous injection of siTUG1 2 h

before anesthesia and surgery without bloodletting); Model + siNC (receiving

subcutaneous injection of siNC 2 h before anesthesia, surgery and bloodletting);

Model + siTUG1groups (receiving subcutaneous injection of siTUG1 2 h before

surgery anesthesia, surgery and bloodletting). (A) TUG1 expression in

myocardial tissue of rats in Sham and Model group (n = 6) (qRT-PCR, GAPDH as

internal control). (B) TUG1 expression in myocardial tissue after

transfected with siTUG1 (qRT-PCR, GAPDH as internal control). (C) MAP at MBO, at

the start of resuscitation, at the end of resuscitation, and 1 and 2 h post

resuscitation. (D,E) Actual bicarbonate (HCO3–) and lactate levels in

rat blood samples (commercially available assay kits). *p

TTC staining results suggested the area of myocardial

infarction in the Model + siNC group was increased relative to Sham + siNC group,

which however was then reduced by silencing TUG1 (Fig. 2A,B, p

Fig. 2.

Fig. 2.

Effect of TUG1 silencing on myocardial injury in rat

model with HS/R. Construction of 4 groups based on experimental animals (6

mice/group) (Sham + siNC, Sham + siTUG1, Model + siNC and Model + siTUG1). The

rats were given subcutaneous injection of phosphate buffer saline containing

siTUG1 or siNC 2 h before surgery and then underwent Sham or HS/R operation.

(A,B) Myocardial infarction size of rats (TTC staining). (C) The myocardial

injury of rats (H&E staining, 100

Fig. 3.

Fig. 3.

Effects of TUG1 silencing on apoptosis, oxidative

stress and inflammatory factor expressions of myocardial tissue in rat model with

HS/R. Construction of 4 groups based on experimental animals (6 mice/group)

(Sham + siNC, Sham + siTUG1, Model + siNC and Model + siTUG1). (A,B) The

apoptosis of myocardial tissue (TUNEL staining) (magnification, 200

To explore whether TUG1 mediated oxidative stress of H9C2, we

transfected siTUG1 into H9C2 cells and determined the transfection efficiency by

qRT-PCR (Fig. 4A, p

Fig. 4.

Fig. 4.

TUG1 silencing counteracted the influences of H2O2 on

viability and apoptosis of H9C2 cells. H9C2 cells were assigned into 6 groups:

Control (normal culture); siNC (transfection with siNC); siTUG1 (transfection

with siTUG1); H2O2 (4-h 400 µM H2O2 treatment);

H2O2 + siNC (transfection with siNC and 4-h 400 µM H2O2

treatment); H2O2 + siTUG1 (transfection with siTUG1 and 4-h 400

µM H2O2 treatment). (A) TUG1 expression in H9C2 cells

transfected with siTUG1 or siNC (qRT-PCR, GAPDH as internal control).

***p

H2O2 treatment attenuated cell viability (Fig. 4C, p

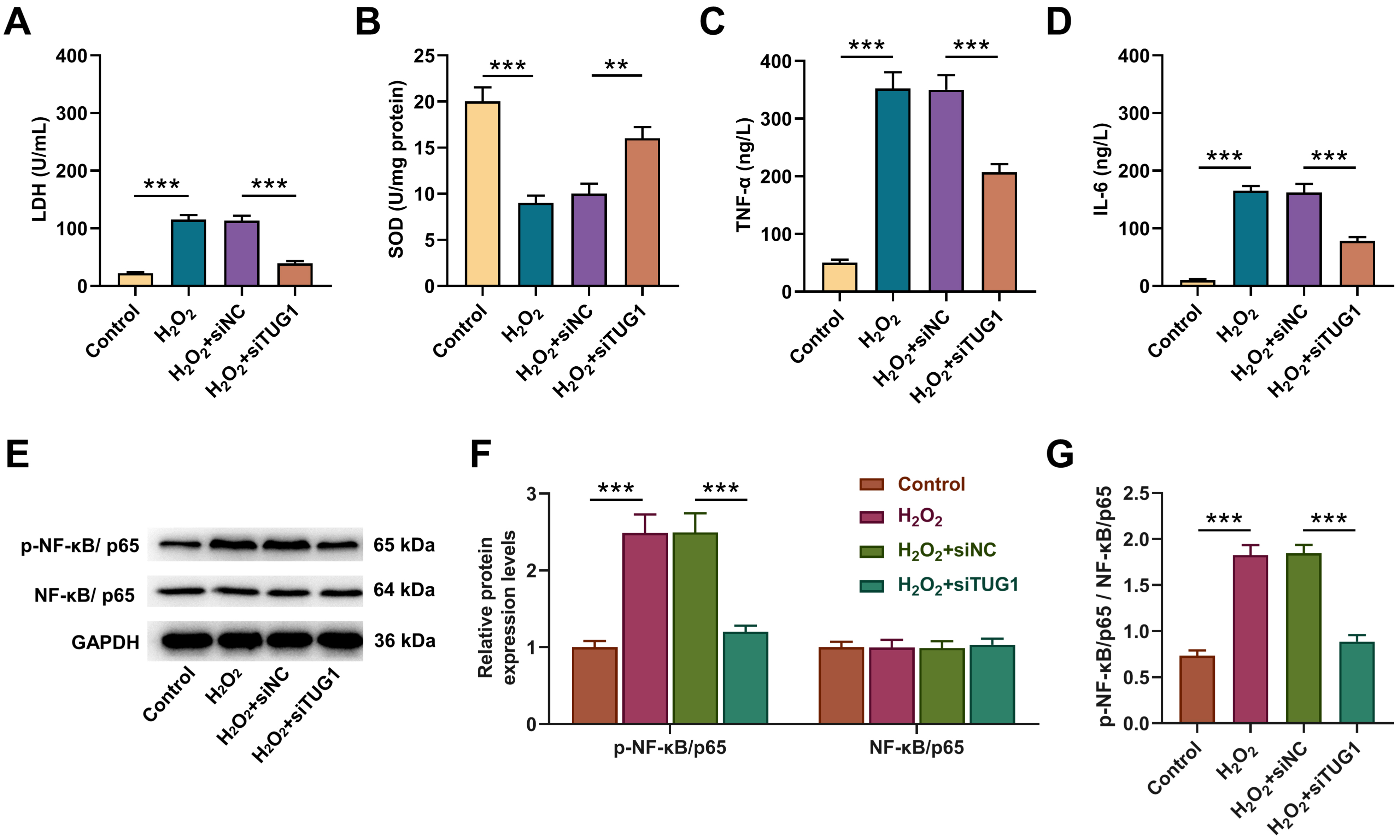

Fig. 5.

Fig. 5.

TUG1 silencing reversed the influences of

H2O2 on oxidative stress, inflammation and NF-

Severe HS/R can produce I/R injury in the ischemic tissue, manifested as a large number of free radicals and excessive inflammatory factors. In addition to restoring tissue perfusion and improving oxygen supply, the mass fluid resuscitation also can reduce oxidative stress and inflammation [19]. Our study clarified that TUG1 participated in the regulation of oxidative stress and inflammation caused by HS/R, and is of great significance for potentiating the effectiveness of fluid resuscitation.

We first constructed I/R rat model by HS/R, and found more TUG1 in

model group than Sham group, hinting that TUG1 may impact HS.

TUG1 silencing mitigated MAP reduction after resuscitation. The proper

pH value of various body fluids in organisms is one of the important conditions

for maintaining normal physiological activities. After treatment with siTUG1, the

acid-base imbalance in the blood of model rat was improved. HS may cause damage

to myocardial function due to the reduction of effective circulating blood volume

and insufficient tissue perfusion [20]. In our study, we observed that following

TUG1 silencing, the area of myocardial infarction, the degree of myocardial

tissue damage and the level of apoptosis were all effectively alleviated of model

rats. SOD, a vital antioxidant enzyme in the organism, can scavenge oxygen free

radicals and repress oxidative stress [21]. MDA is the end product of lipid

oxidation, the level of which can be upregulated by the rising free radicals

[22]. GSH is a common antioxidant [23]. TNF-

NF-

Taken together, TUG1 acts as an ideal and novel target for diagnosis

and treatment of hemorrhagic shock and HS/R. However, the absence of experiments

(NF-

To sum up, we corroborate TUG1 participates in mediating impaired cardiac function, oxidative stress damage and inflammatory response caused by HS/R, providing a new target for clinical treatment of HS/R.

The analyzed data sets generated during the study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Substantial contributions to conception and design: WL, HYC. Data acquisition, data analysis and interpretation: XLZ, MRL. Drafting the article or critically revising it for important intellectual content: All authors. Final approval of the version to be published: All authors. Agreement to be accountable for all aspects of the work in ensuring that questions related to the accuracy or integrity of the work are appropriately investigated and resolved: All authors.

Our research was approved by Zhejiang Baiyue Biotech Co., Ltd.’s Ethics Committee for Experimental Animals Welfare (ZJBYLA-IACUC-20220427).

Not applicable.

This work was supported by the Special Project of Fujian National Clinical Research Base of Traditional Chinese Medicine (JDZX201902).

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

Publisher’s Note: IMR Press stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.