1 Department of Marine Life Science, Jeju National University, 63243 Jeju, Republic of Korea

2 Food Safety and Processing Research Division, National Institute of Fisheries Science, 46083 Busan, Republic of Korea

3 Department of Biotechnology, Faculty of Agriculture and Plantation Management, Wayamba University of Sri Lanka, Makandura, 60170 Gonawila (NWP), Sri Lanka

4 Department of Seafood Science and Technology, The Institute of Marine Industry, Gyeongsang National University, 53064 Tongyeongsi, Gyeongsangnamdo, Republic of Korea

5 Major of Biomedical Engineering, Division of Smart Healthcare, College of Information Technology and Convergence and New-Senior Healthcare Innovation Center (BK21 Plus), Pukyong National University, Namgu, 48513 Busan, Republic of Korea

†These authors contributed equally.

Abstract

A sea cucumber (Stichopus japonicus) is an invertebrate rich in high-quality protein peptides that inhabits the coastal seas around East Asian countries. Such bioactive peptides can be utilized in targeted disease therapies and practical applications in the nutraceutical industry.

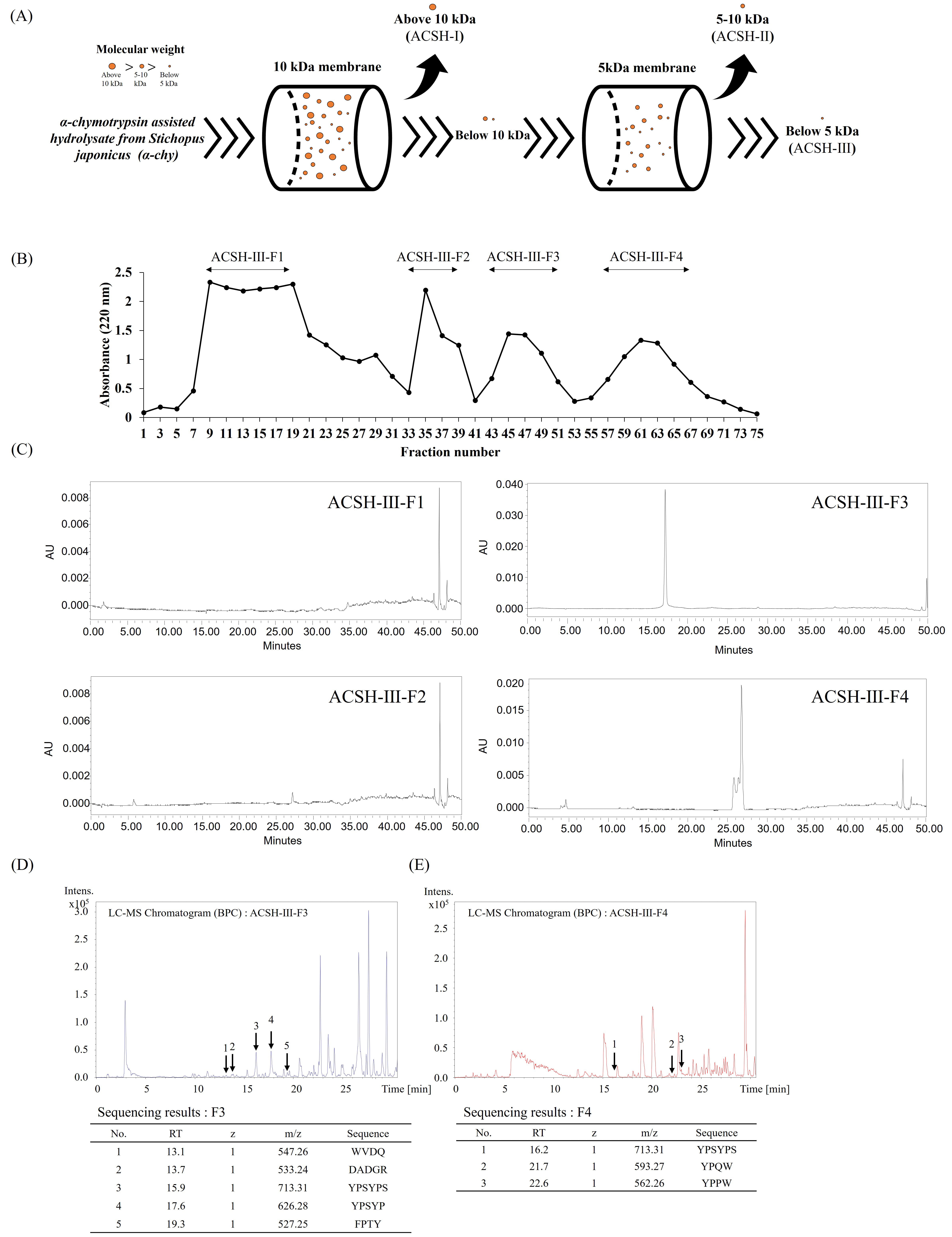

Bioactive peptides were isolated from Stichopus japonicus through ultrafiltration and Sephadex G-10 size exclusion chromatography. The low-molecular-weight fraction (ACSH-III) showed the highest hydroxyl radical scavenging and angiotensin-converting enzyme (ACE) inhibitory activities. Subsequent purification of ACSH-III resulted in four fractions, of which ACSH-III-F3 and ACSH-III-F4 exhibited significant bioactivity.

Peptides identified in these fractions, including Phenylalanine-Proline-Threonine-Tyrosine (FPTY) and Tyrosine-Proline-Serine-Tyrosine-Proline-Serine (YPSYPS), were characterized using high-performance liquid chromatography (HPLC) and quadrupole time-of-flight mass spectrometry (QTOF-MS). FPTY demonstrated the most potent antioxidant and antihypertensive activities among these peptides, with IC50 values of 0.11 ± 0.01 mg/mL for hydroxyl radicals and 0.03 ± 0.01 mg/mL for ACE inhibition. Docking simulations revealed strong binding affinities of these peptides to the active site of the ACE, with FPTY displaying interactions similar to those of the synthetic inhibitor lisinopril.

These findings suggest that the identified peptides, particularly FPTY, have potential applications as natural antioxidants and functional foods.

Keywords

- Stichopus japonicus

- bioactive peptide

- antioxidant activity

- antihypertensive activity

- nutraceuticals

Cardiovascular disease is widely regarded in industrialized nations as one of the most pressing health concerns. Indeed, cardiovascular diseases are the leading cause of death globally, with hypertension emerging as the primary risk factor in their development [1]. The angiotensin-converting enzyme (ACE) breaks down active bradykinin, which is essential for blood pressure control, and converts inactive angiotensin I into active angiotensin II, resulting in arterial contractions and elevated blood pressure [2]. Hypertension is commonly managed with medication, in particular ACE inhibitors, which are widely accessible, cost-effective, and also recommended as an initial treatment for other prevalent chronic conditions such as heart failure with reduced ejection fraction and chronic kidney disease [3]. Lisinopril, trandolapril, ramipril, moexipril, and quinapril hydrochlorides are chemically synthesized antihypertensive drugs [4]. ACE inhibitors are associated with a modest risk of bradykinin-mediated angioedema, acute kidney injury (AKI), hyperkalemia, and chronic cough [3]. However, studies have demonstrated that, unlike synthetic ACE inhibitors, ACE inhibitory peptides derived from dietary sources can lower high blood pressure without causing these adverse effects [5, 6]. There is also increasing evidence suggesting a connection between oxidative stress and the onset of numerous diseases, including hypertension [7]. Utilizing antioxidant compounds may present a promising strategy for mitigating oxidative stress and the associated cardiovascular diseases.

Excessive reactive oxygen species (ROS) levels can cause irreversible oxidative stress or damage; one of the primary drivers of oxidative damage is the imbalance between the oxidant and antioxidant systems in the human body [8]. Under normal conditions, the antioxidant defense system plays an essential role in scavenging excess ROS to stabilize the configuration of highly reactive free radicals and prevent cellular damage. The primary antioxidant defense mechanism is enzymatic, involving enzymes such as superoxide dismutase, glutathione peroxidase, catalase, peroxidase, and glutathione reductase [9]. However, external factors such as environmental pollution, ultraviolet (UV) irradiation, and exposure to chemical reagents can disrupt antioxidant systems, resulting in severe oxidative stress [10]. Excessive ROS-mediated oxidative stress is strongly associated with cell death, deoxyribonucleic acid (DNA) fragmentation, and tissue oxidation [11], which contribute to various human diseases, including neurodegenerative [12], cardiovascular [13], chronic kidney diseases [14], and lung cancer [15]. Recently, some publications have reported that excessive oxidative stress can induce metabolic syndromes such as diabetes, obesity, and cardiovascular disease [16]. Therefore, developing therapeutic agents capable of regulating excessive ROS generation would reduce its incidence, improve patient outcomes across a broad spectrum of disorders, and be clinically beneficial [17].

Notably, there is growing recognition of the bioactivities of naturally derived peptides; bioactive peptides are potent antioxidant candidates with biotechnological applications in the nutraceutical industry [18]. Therefore, many researchers are focusing on the therapeutic development of novel peptides isolated from land or marine animals and plants. Therapeutically active peptides generally comprise 2–20 amino acids and are abundant in bioresources, especially in animals with high peptide content. Moreover, these peptides have been shown to possess antioxidant [19], antimicrobial [20], antiwrinkle [21], anticancer [22], and antihypertensive [23] activities; likewise, a study has also demonstrated these properties in low-molecular-weight peptides [24]. Study has reported that the bioactivity of peptides originates from their specific compositional and structural characteristics [25]. Over the past few decades, biotechnological study has characterized many bioactive peptides isolated from marine animals [26].

A study has reported the importance of marine-derived peptides since these can also provide anti-inflammatory, antibacterial, and antihypertensive effects [27]. Therefore, they have received significant attention in the food and functional food industries. Marine-derived functional ingredients and bioactive peptides obtained from enzymatically hydrolyzed fish exhibit various functionalities highlighting their potential applications in food technology for developing functional foods and nutraceuticals [28]. Marine-derived peptides were found to promote antihypertensive properties by inhibiting the ACE, which reduces the production of angiotensin II (Ang II), a vasoconstrictor, and increases nitric oxide and endothelin in HUVECs and vascular endothelial cells [29]. Hence, several marine bioactive peptides have been commercialized in food and functional food industries [30].

Stichopus japonicus (S. japonicus) is a teleost of the genus

Stichopus and is mainly found in East Asian countries [31]. S.

japonicus is a commercially valuable species that functions as a seafood and

critical raw material in traditional medicine [32]. The body of S.

japonicus consists mainly of collagen and mucopolysaccharides that possess

nutritional and biological activities, such as lipid metabolism and antioxidant,

antihypertensive, anticancer, antifatigue, and regenerative capacities [33]. In

our previous study,

Sephadex G-10 gel filtration resin (catalog: 07-0010-01), used for peptide

separation, was purchased from GE Healthcare (Uppsala, Sweden). Bovine pancreatic

S. japonicus samples were collected from Jeju Island, South Korea. The

captured adult S. japonicus was then dried and homogenized. After

homogenization, 1 g of powdered S. japonicus and 10 mg of

The peptides in two of the four Sephadex G-10 fractions (ACSH-III-F3 and

ACSH-III-F4) were sequenced and synthesized according to the protocol described by

Kim et al. (2019) [35]. The sequences and masses of the peptides in

ACSH-III-F3 and ACSH-III-F4 were analyzed using the LC UltiMate 3000 LC system

(Dionex, Sunnyvale, CA, USA) equipped with Poroshell 120 EC C18 separation

columns (2.1

A hydrogen peroxide scavenging assay was performed on the purified peptide fractions to assess their free radical scavenging activities. Hydroxyl radical scavenging activity was determined using the method described by Lee et al. (2023) [36]. Briefly, 50 µL 0.1 M phosphate buffer (Welgene Inc., Daegu, Korea) and 50 µL peptide samples were added to 96-well plates. Then, 10 µL 10 mM hydrogen peroxide (Junsei, Chemical, Tokyo, Japan) was added to each well, and the plates were incubated at 37 °C for 5 min. After incubation, 15 µL 1 U/mL peroxidase (Fluka, Buchs, Switzerland) and 1.25 mM 2,2′-azino-bis (3-ethylbenzothiazoline-6-sulfonic acid) diammonium salt (Sigma, St Louis, MO, USA) were added to the wells. After that, the mixtures were incubated in a shaking incubator at 37 °C for 10 min. Following an additional incubation period, the absorbance was measured at 405 nm using a microplate reader (Synergy HT Multi Detection microplate reader; BioTek, Winooski, VT, USA).

An ACE inhibition assay was performed to determine the potential antihypertensive activity of the isolated peptides. The peptides were dissolved in deionized water, and different concentrations were mixed with an enzyme-working solution (3-hyppurylbutyryl-Gly-Gly-Gly, aminoacylase). The principle of this assay is as follows: 3-hyppurylbutyryl-Gly-Gly-Gly (3HB-GGG) is converted by the ACE to 3-hyppurylbutyryl-Gly (3HB-G). Then, 3HB-G is converted into 3-hyppurylbutyryl (3HB) by an aminoacylase. Finally, 3HB reacts with a water-soluble tetrazolium salt (WST) colorimetric indicator to form a WST formazan. These WST formazan concentrations were measured at 450 nm using a microplate reader. The ACE inhibition assay and activity calculation were performed according to the manufacturer’s instructions (ACE-WST ELISA kit; Rockville, MD, USA).

In silico evaluation was performed using Discovery Studio V3.0 (Accelrys Inc., San Diego, CA, USA) in accordance with a previously published method [37]. Briefly, the X-ray crystallographic protein structure of the ACE was obtained from the Protein Data Bank (PDB) (PDB ID: 1O86). The obtained structure was corrected using the “clean protein” tool by removing the water and heteroatoms and inserting any missing atoms. Then, the structure was prepared using the “prepare protein” tool by correcting the missing loops and atoms. The regenerated structure was then superimposed on the raw structure, and the root mean square deviation (RMSD) value was calculated. After confirming the accuracy of the prepared structure, the active site was prepared. The ACE structure is available in the PDB as a complex with lisinopril (https://www.rcsb.org/structure/1O86). Therefore, the amino acid residues in the ACE responsible for binding were considered as the geometrical center of the active site, and an active site sphere was generated. The automated workflow “flexible docking” was used to perform in silico simulations. After obtaining the most likely ligand–receptor confirmation, the binding energy was calculated using the “calculate binding energy” tool. The binding energy was calculated using the equation presented below [37].

All experiments were conducted in triplicate, and the results are presented as

the mean

To purify the active peptides from S. japonicus, ACSH was fractionated using a series of UF membranes with reduced MW cut-offs (10 and 5 kDa), resulting in three fractions (above 10 kDa, ACSH-I; 5–10 kDa, ACSH-II; below 5 kDa, ACSH-III). A schematic representation of the UF fractionation method is shown in Fig. 1A. Among the UF fractions, low-molecular-mass ACSH-III exhibited the greatest hydroxyl radical scavenging activity, while the ACE inhibitory activity in ACSH-III also gradually increased; thus, ACSH-III was selected for peptide purification. Four fractions were identified from ACSH-III using Sephadex G-10 size exclusion chromatography; the resulting chromatograms are shown in Fig. 1B. HPLC was performed to identify peptides in the Sephadex G-10 fractions. Analytical HPLC was performed with silica-based Atlantis T3 columns using an increasing gradient of ACN eluent. The HPLC chromatograms of the Sephadex G-10 fractions are presented in Fig. 1C and show two major HPLC peaks for ACSH-III-F3 and ACSH-III-F4 at a wavelength of 280 nm. Ultimately, these results indicate that the Sephadex G-10 fractions, ACSH-III-F3 and ACSH-III-F4, contained peptides. Fig. 1D,E show the ACSH-III-F3 peptide sequences identified using quadrupole time-of-flight mass spectrometry (QTOF-MS). The peptide sequences were identified as TRP-VAL-ASP-GLN (WVDQ; MW: 547.26), GLU-ALA-GLU-GLY-ARG (DADGR; MW: 533.24), TYR-PRO-SER-TYR-PRO-SER (YPSYPS; MW: 713.31), TYR-PRO-SER-TYR-PRO (YPSYP; MW: 626.28), PHE-PRO-THR-TYR (FPTY; MW: 527.25), VAL-PRO-PRO-TYR-PHE-GLU-TRP-GLY (VPPYPEWG; MW: 944.45), and VAL-PRO-PRO-TYR-PHE-GLU-TRP (VPPYPEW; MW: 887.43). The ACSH-III-F4 peptide sequences were identified as TYR-PRO-SER-TYR-PRO-SER (YPSYPS; MW: 713.31), TYR-PRO-GLN-TRP (YPQW; MW: 593.27), and TYR-PRO-PRO-TRP (YPPW; MW: 562.26).

Fig. 1.

Fig. 1.

Purification and identification of bioactive peptides from Stichopus japonicus. (A) Scheme of ultrafiltration methods used to obtain the three ultrafiltration fractions based on molecular size: above 10 kDa (ACSH-I), 5–10 kDa (ACSH-II), and below 5 kDa (ACSH-III) (B) Chromatogram of Sephadex G-10 fractions (ACSH-III-F1, ACSH-III-F2, ACSH-III-F3, and ACSH-III-F4). (C) High-performance liquid chromatograms of Sephadex G-10 fractions (ACSH-III-F1, ACSH-III-F2, ACSH-III-F3, and ACSH-III-F4). Liquid Chromatography-Mass Spectrometry (LC–MS) analysis and the (D) ACSH-III-F3 and (E) ACSH-III-F4 peptide sequences. ACSH, α-chymotrypsin assisted hydrolysate from Stichopus japonicus; WVDQ, Tryptophan-Valine-Aspartic acid-Glutamine; DADGR, Aspartic acid-Alanine-Aspartic acid-Glycine-Arginine; YPSYPS, Tyrosine-Proline-Serine-Tyrosine-Proline-Serine; YPSYP, Tyrosine-Proline-Serine-Tyrosine-Proline; FPTY, Phenylalanine-Proline-Threonine-Tyrosine; YPQW, Tyrosine-Proline-Glutamine-Tryptophan; YPPW, Tyrosine-Proline-Proline-Tryptophan.

The hydrogen peroxide scavenging and ACE inhibitory activities of the Sephadex

G10-derived fractions were determined. The 50% inhibitory concentration

(IC50) of hydrogen peroxide and the ACE are shown in Table 1. The IC50

of hydrogen peroxide and the ACE were recorded as 1.97

| Type | Sample | Hydrogen peroxide scavenging activity, IC50 value (mg/mL) | ACE inhibitory activity, IC50 value (mg/mL) |

| Enzyme-assisted hydrolysate | ACSH | 1.97 |

1.82 |

| Ultrafiltration fractions | ACSH-I | 1.14 |

1.78 |

| ACSH-II | 0.72 |

1.51 | |

| ACSH-III | 0.26 |

1.68 | |

| Sephadex G-10 fractions | ACSH-III-F1 | 1.51 |

1.23 |

| ACSH-III-F2 | 1.60 |

1.16 | |

| ACSH-III-F3 | 0.45 |

0.65 | |

| ACSH-III-F4 | 0.35 |

0.90 | |

| Synthesized peptides | Tryptophan-Valine-Aspartic acid-Glutamine (WVDQ) | 1.97 | |

| Aspartic acid-Alanine-Aspartic acid-Glycine-Arginine (DADGR) | 2.36 | ||

| Tyrosine-Proline-Serine-Tyrosine-Proline-Serine (YPSYPS) | 0.17 |

0.21 | |

| Tyrosine-Proline-Serine-Tyrosine-Proline (YPSYP) | 0.16 |

0.21 | |

| Phenylalanine-Proline-Threonine-Tyrosine (FPTY) | 0.11 |

0.03 | |

| Valine-Proline-Proline-Tyrosine-Proline-Glutamic acid-Glycine (VPPYPEWG) | 0.44 |

0.37 | |

| Valine-Proline-Proline-Tyrosine-Proline-Glutamic acid (VPPYPEW) | 0.20 |

0.08 | |

| Tyrosine-Proline-Glutamine-Tryptophan (YPQW) | 0.23 |

0.13 | |

| Tyrosine-Proline-Proline-Tryptophan (YPPW) | 0.28 |

0.27 |

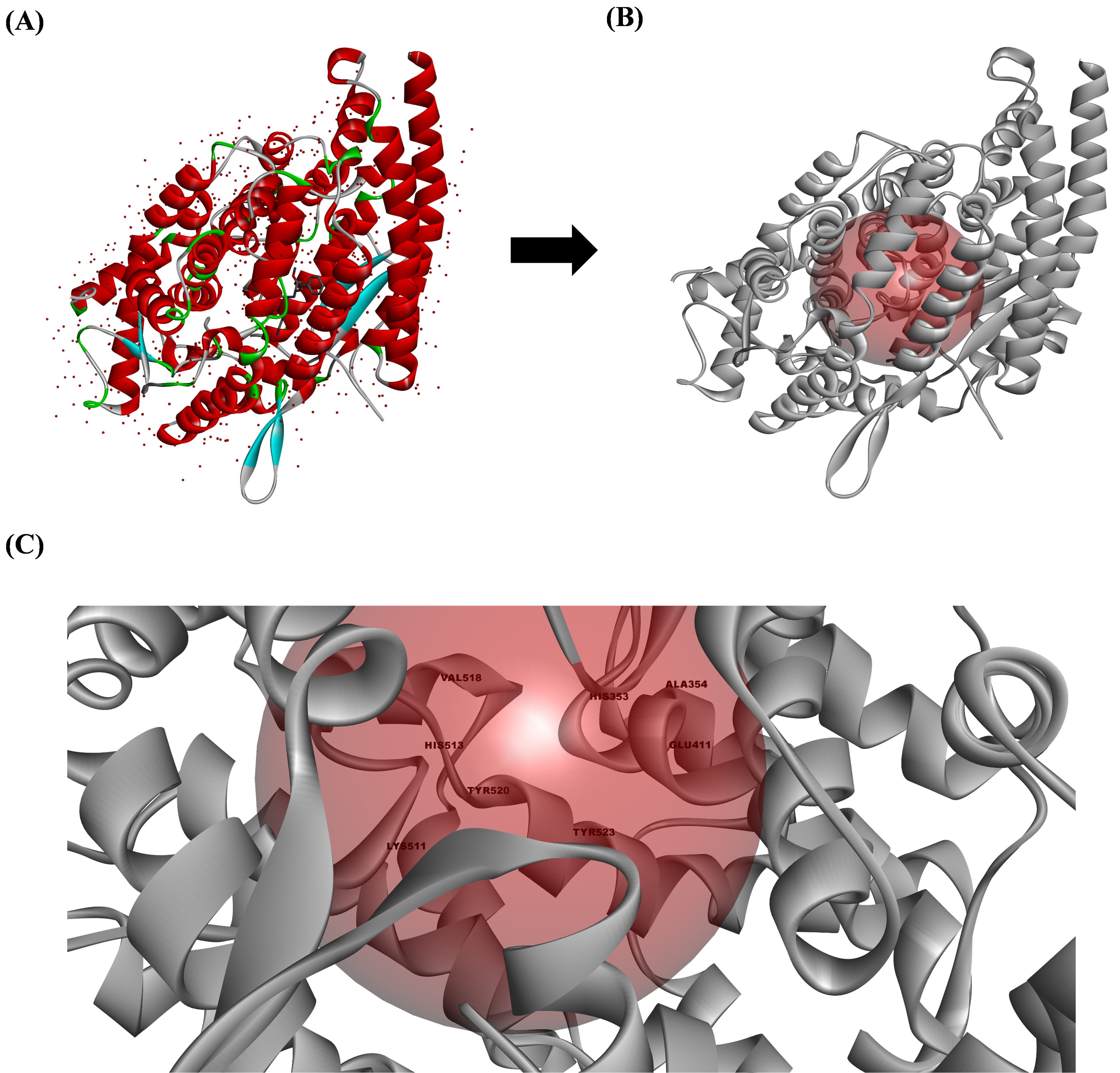

The ACE crystal structure was obtained from the PDB (PDB ID: 1O86) and processed

using Discovery Studio V3.0. The resulting active sites of the ACE comprised

VAL318, HIS353, ALA354, GLU411, LYS511, HIS513, TYR520, and TYR523 amino acid

residues (Fig. 2). Lisinopril was bound to the ACE at ASN277, GLN 281, THR282,

and TYR520 via four conventional hydrogen bonds, one van der Waals bond at

GLU384, and ten carbon–hydrogen bonds formed at TRP279, CYS352, CYS370, GLN369,

ASP377, VAL379, ASP453, LYS454, PHE457, and PHE527. Furthermore, lisinopril

formed one salt bridge and one attractive charge alongside two cation pi bonds

and one anion–pi bond at ASP415, TYR523, GLU162, GLU376, and HIS383,

respectively. Aside from these bonds, lisinopril also formed weaker bonds, such

as one

Fig. 2.

Fig. 2.

The active site preparation of the angiotensin-converting enzyme (ACE). (A) The ACE structure obtained from the Protein Data Bank (PDB) (1O86), (B) the ACE structure prepared using Discovery Studio V3.0 (Accelrys Inc.), and (C) the active site of the ACE that is responsible for converting angiotensin I to angiotensin II. All the structures were analyzed using Discovery Studio visualizer V3.0 (Accelrys Inc.).

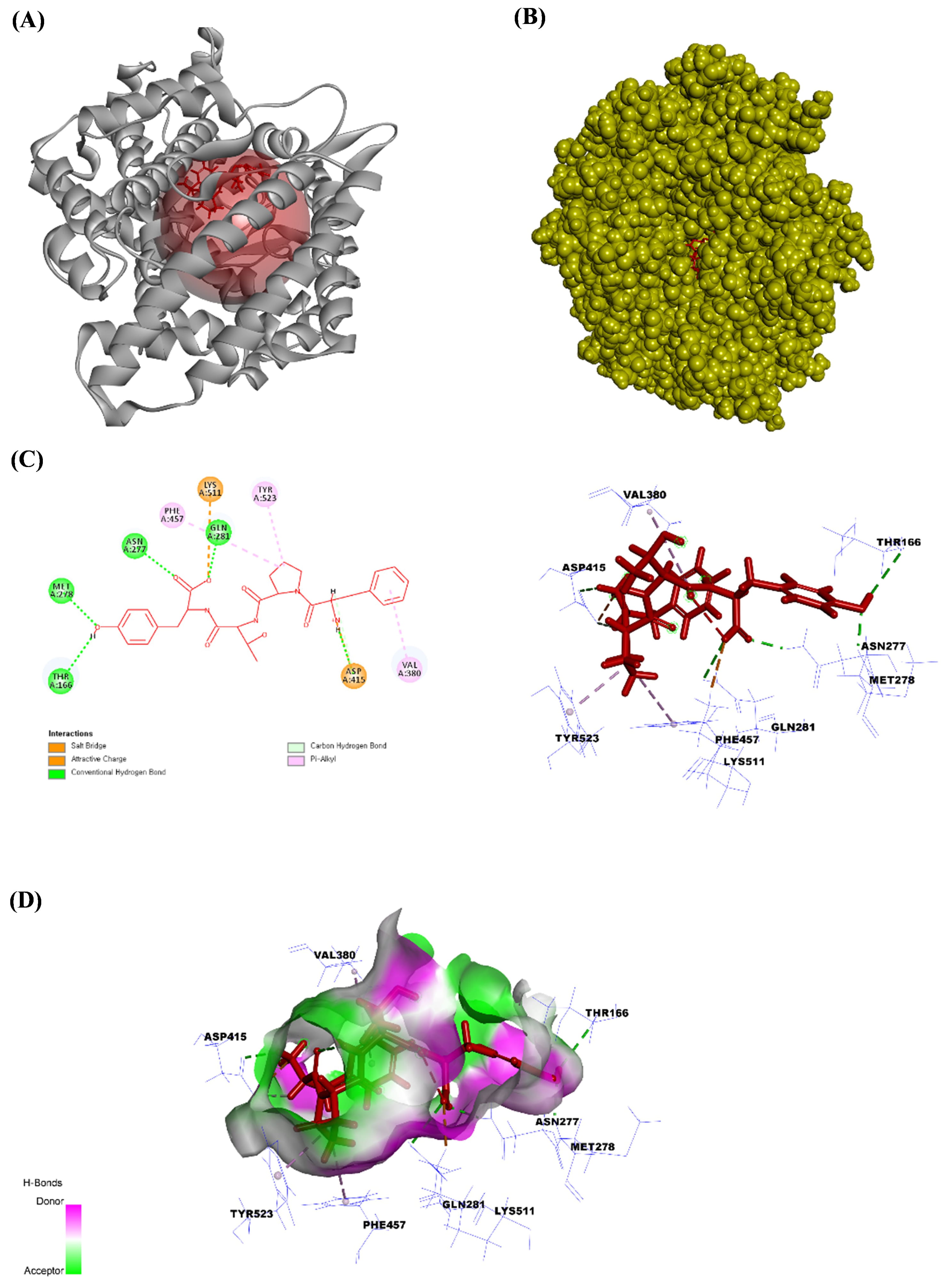

Fig. 3.

Fig. 3.

The angiotensin-converting enzyme (ACE) structure bound to FPTY. (A) The ribbon structure of ACE bound to FPTY, (B) the solid structure of ACE bound to FPTY, (C) the ligand interaction between FPTY and amino acids in the ACE, and (D) the 2D image of the bonds between FPTY and the ACE. All the structures were analyzed using Discovery Studio visualizer V3.0 (Accelrys Inc.).

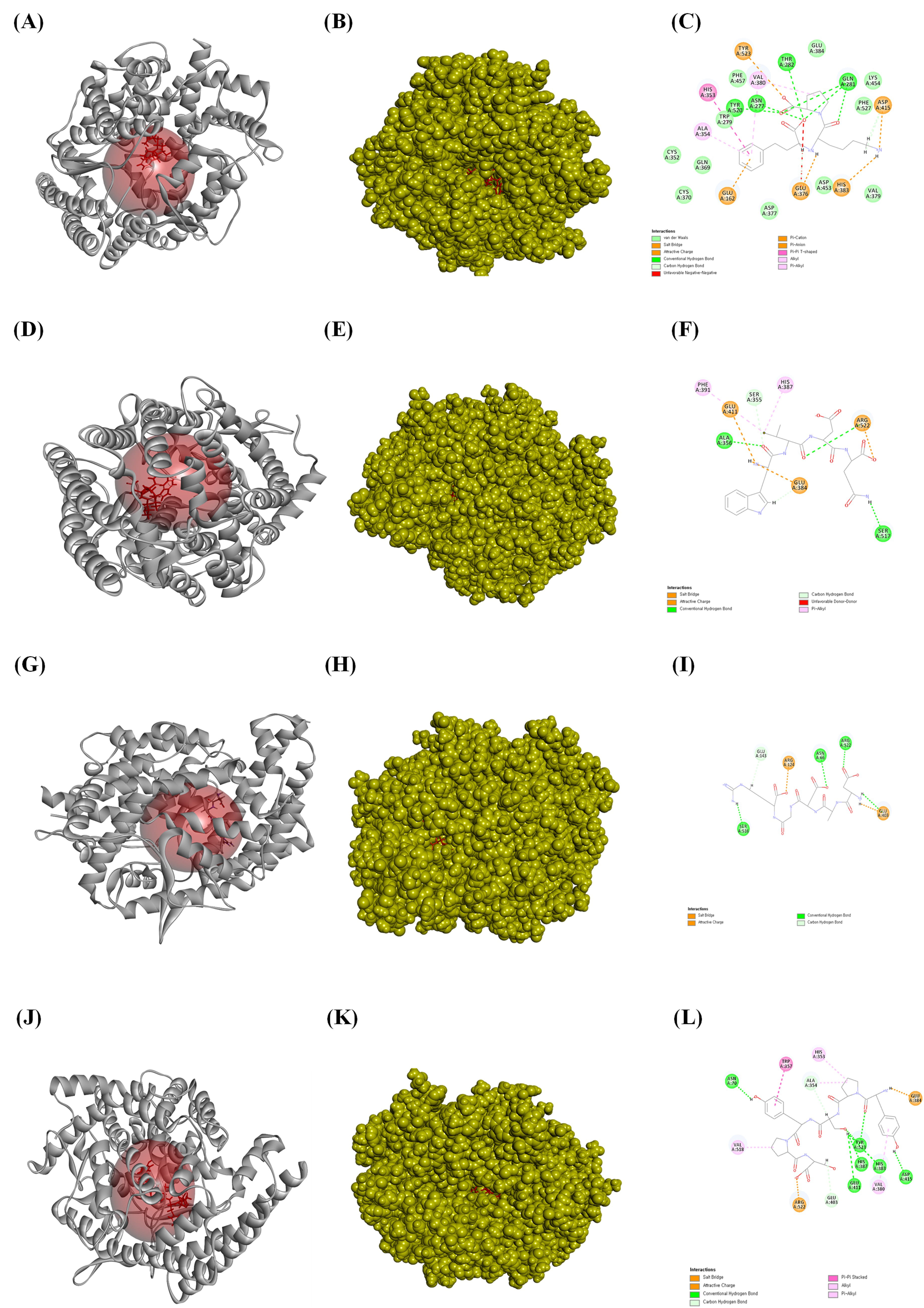

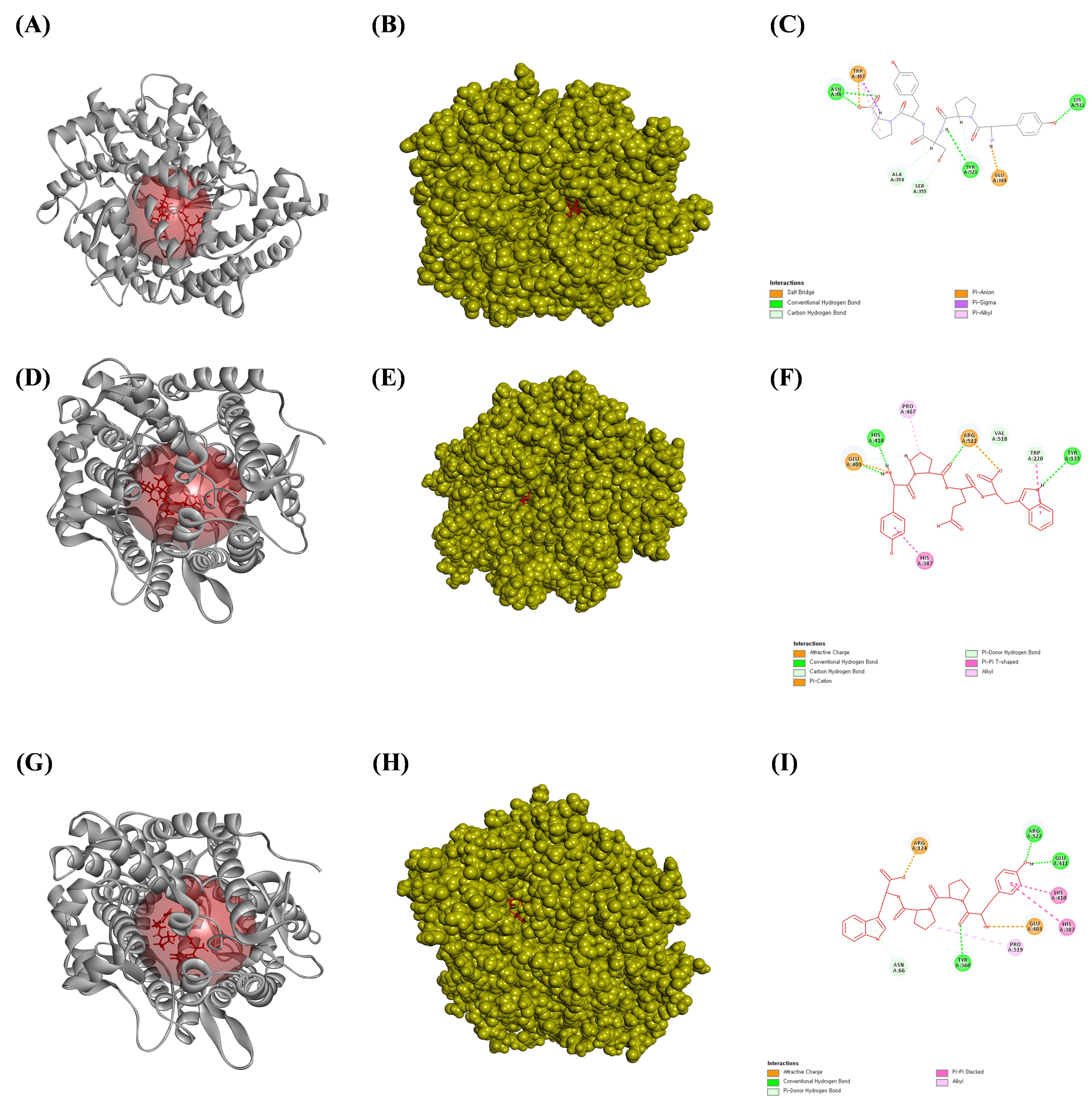

Fig. 4.

Fig. 4.

The ligands bound to the active site of the angiotensin-converting enzyme (ACE). (A) The ribbon structure of ACE bound to lisinopril, (B) the solid structure of ACE bound to lisinopril, and (C) a 2D image of the bonds between ACE and lisinopril. (D) The bound ribbon structure of ACE to WVDQ, (E) the solid structure of ACE bound to WVDQ, and (F) a 2D image of the bonds between ACE and WVDQ. (G) The bound ribbon structure of ACE to DADGR, (H) the solid structure of ACE bound to DADGR, and (I) a 2D image of the bonds between ACE and DADGR. (J) The bound ribbon structure of ACE to YPSYPS, (K) the bound solid structure of ACE to YPSYPS, and (L) a 2D image of the bonds between ACE and YPSYPS. All the structures were analyzed using Discovery Studio visualizer V3.0 (Accelrys Inc.).

Fig. 5.

Fig. 5.

The ligands bound to the active site of the angiotensin-converting enzyme (ACE). (A) The bound ribbon structure of ACE to YPSYP, (B) the bound solid structure of ACE to the YPSYP, and (C) a 2D image of the bonds between ACE and YPSYP. (D) The bound ribbon structure of ACE to the YPQW, (E) the bound solid structure of ACE to YPQW, and (F) a 2D image of the bonds between ACE and YPQW. (G) The bound ribbon structure of ACE to the YPPW, (H) the solid structure of ACE bound to YPPW, and (I) a 2D image of the bonds between ACE and YPPW. All the structures were analyzed using Discovery Studio visualizer V3.0 (Accelrys, Inc.).

Marine animal-derived secondary metabolites have been proven to possess highly

effective biological activities. Fish have relatively high protein content ratios

compared to other nutritional components, and several bioactive peptides from

these sources have been proven beneficial in human diseases. Fish-derived

low-molecular-weight bioactive peptides have been recognized as functional

ingredients that exhibit various biological properties, such as antioxidant,

antifatigue, and immunoregulatory activities [38, 39]. Thus, extensive research

has been conducted to develop efficient methods for isolating and identifying

novel lead compounds with versatile uses in functional food and pharmaceutical

industries. In this study, S. japonicus samples were enzymatically

hydrolyzed with

Next, we performed an in silico molecular docking study to verify the binding affinity of the purified peptide for the ACE binding site. ACE inhibitors are the first-line therapeutic agents for the initial prevention of hypertension. Recent study has demonstrated that ACE inhibitors have comparable effects on the long-term prognosis and mortality rates in cardiovascular, cerebrovascular, and renal diseases [47]. Lisinopril can be used to treat acute myocardial infarction and high blood pressure and as an adjunct therapy for heart failure by inhibiting the ACE [50]. Thus, the current study attempted to determine the binding affinity and most stable pose of each isolated peptide in the active site of the ACE to evaluate their potential as small molecules and antihypertensive drugs. The C-terminus of angiotensin I contains a dipeptide consisting of histidine and leucine residues, which are cleaved by the ACE to produce angiotensin II. Therefore, peptides with high binding affinities for this active site would inhibit the histidine-leucine (HIS–LEU) motif cleavage. All peptides isolated from the ACSH-III-F3 and ACSH-III-F4 Sephadex G-10 fractions showed high binding affinity for the ACE active site. Our results also indicated that peptides containing hydrophobic amino acids, such as YPSYPS, YPSYP, FPTY, YPQW, and YPPW, showed strong ACE inhibitory activity. Supplementary Table 2 indicates the ratio of hydrophobic to hydrophilic amino acids in the peptide. Among the tested peptides, FPTY had the highest hydrophobic amino acid content. Thus, the in silico docking results indicated that these peptides have high binding affinities and interaction energies for the ACE. Furthermore, we found that FPTY showed specificity for binding to the ACE compared to other amino acids. FPTY shared the same amino acid residues with lisinopril, which mediates hydrogen bonding with THR166, ASN277, MET278, and GLN281. Furthermore, similar to lisinopril, FPTY forms a salt bridge with ASP415 and interacts with TYR523 via an alkyl–pi bond, whereas lisinopril forms a cation–pi bond. In addition to these bonds, FPTY has an attractive charge with LYS511 and an alkyl–pi bond with both VAL380 and PHE457. The in vitro results revealed that FPTY exhibited the highest antihypertensive activity by inhibiting the ACE.

Our findings suggest that Stichopus japonicus contains bioactive peptides with antioxidant and antihypertensive properties. In particular, FPTY showed promising properties and warrants further investigation for its therapeutic potential in treating oxidative stress and hypertension. FPTY also demonstrated strong ROS scavenging activity and significantly inhibited the ACE activity, which was attributed to its peptide structure and the specific amino acids it contained. However, further studies are required to verify these initial results, such as molecular dynamics simulations to explore the protein–ligand dynamics and additional experimental assays to validate the activity of FPTY. Further investigation into bioactive peptides from Stichopus japonicus could provide valuable insights for targeted therapies in these disease areas and lead to practical applications in the nutraceutical and functional food industries, potentially enhancing the development of new and effective dietary supplements.

Data presented in this study are contained within this article and in the supplementary materials, or are available upon request to the corresponding author.

HGL proposed the conception and design. HGL, DPN, JGJ, HHACKJ, NML and WKJ performed a acquisition of data. JGJ, JYO, YRC, HSK and WKJ performed the analysis and interpretation of data. HHACKJ, NML and MJMSK conducted the initial screening. HGL, DPN, MJMSK, HSK, SHP and YJJ performed the statistical analysis. HGL, JGJ, JYO, HHACKJ and NML organized the figures and tables. WKJ participated in the project design. HGL and DPN wrote this primary article. YRC and HSK revised and reviewed the manuscript. All authors contributed to editorial changes in the manuscript. All authors read and approved final version of the manuscript and are fully prepared to take responsibility for all aspects of the work.

Studies using Stichopus japonicus were exempt from review and approval by the Jeju National University.

We would like to express my gratitude to all those who helped me during the writing of this manuscript.

This work was supported by the research grant of the Gyeongsang National University in 2023. Further, this research was supported by the Basic Science Research Program through the National Research Foundation of Korea (NRF) funded by the Ministry of Education (2021R1A6A1A03039211).

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Supplementary material associated with this article can be found, in the online version, at https://doi.org/10.31083/j.fbl2910368.

References

Publisher’s Note: IMR Press stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.