1 Department of Emergency Medicine, Shanghai Jiao Tong University Affiliated Sixth People’s Hospital, 200233 Shanghai, China

2 Department of Neurosurgery, Minhang Hospital, Fudan University, 201100 Shanghai, China

†These authors contributed equally.

Abstract

As antioxidant and anti-inflammatory agents, carbonic anhydrase inhibitors can exert potentially useful therapeutic effects following central nervous system trauma, including intracerebral hemorrhage (ICH). However, the therapeutic efficacy of ethoxyzolamide (ETZ) as a novel carbonic anhydrase inhibitor for ICH has not yet been determined.

An autologous blood injection method was used to establish ICH models, which were then used to establish the effects of intraperitoneal injection of ETZ on ICH. Neuronal damage, apoptotic protein expression, oxidative and inflammatory factor content, microglia marker Iba-1 positivity, hepatic and renal pathological changes, and serum concentrations of hepatic and renal function indices were assessed by Nissl staining, western blotting, enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA), immunohistochemistry, hematoxylin and eosin (HE) staining, and automatic biochemical analysis in brain tissues.

The ICH group showed massive hemorrhagic foci; significant increases in brain water content, modified mouse neurological deficit scoring (mNSS) score, pro-apoptotic protein expression, oxidative factors, pro-inflammatory factors, and Iba-1 positivity; and significant reductions in Nissl body size, anti-apoptotic protein expression, and antioxidant factors, all of which were reversed by ETZ in a dose-dependent manner. ETZ has a good biosafety profile with no significant burden on the human liver or kidneys. The Kelch-like ECH-associated protein 1 (Keap1)/nuclear factor erythroid 2-related factor 2 (Nrf2) pathway was mildly activated in ICH mice, and was further increased after ETZ injection. Molecular docking experiments revealed that ETZ could dock onto the Nrf2-binding domain of keap1.

ETZ, as a novel carbonic anhydrase inhibitor, further activated the Keap1/Nrf2 pathway by docking with the Nrf2-binding domain of keap1, thereby exerting antioxidant, anti-inflammatory, anti-apoptotic, and cerebral neuroprotective effects in ICH mice.

Keywords

- carbonic anhydrase inhibitor

- effects

- ethoxzolamide

- intracerebral hemorrhage

- the Keap1/Nrf2 pathway

Intracerebral hemorrhage (ICH) is a common cerebrovascular disease associated with high rates of disability and death, with approximately 40% of patients dying within 30 days of disease onset, and only 20% achieving functional independence within 6 months [1]. ICH accounts for approximately 10–15% of all stroke cases in the United States, Europe, and Australia, with an even higher incidence of 20–30% in Asia [2]. Worldwide, there are approximately 2 million new cases of ICH annually. Epidemiological statistics have shown that the incidence of stroke and ICH in China is approximately 60–80/100,000, accounting for 20–30% of acute cerebrovascular diseases. As such, this disease inflicts a heavy economic burden on the country, society, and families [3]. With the gradual aging of China’s population, the incidence of ICH in China is becoming increasingly serious, representing a significant public health problem. However, no specific treatment has yet been proposed for ICH.

The pathological progression of brain injury following ICH is complex, and includes two main mechanisms: primary injury due to hematoma formation and enlargement, and a much more complicated secondary injury caused by the toxicity of resulting oxidative stress, inflammation, and neuronal damage [4]. The brain is particularly vulnerable to oxidative damage because of its relatively weak antioxidant capacity and high metabolic activity [5]. In this context, researchers are becoming increasingly interested in secondary injury following ICH as oxidative stress has been shown to play a critical role in brain edema, blood-brain barrier (BBB) destruction, and neuronal death [6]. Previous studies have further demonstrated that levels of reactive oxygen species (ROS) increase with the reduction of antioxidant enzymes in the brain following ICH [7, 8]. Numerous studies in animal and cellular models have demonstrated the potent role of antioxidant molecules in alleviating ICH [9, 10, 11]. Both in vivo and in vitro experiments on ICH have supported the idea that baicalin can cross the BBB and improve neurological impairment by reducing the oxidative damage induced by ferroptosis [9]. Furthermore, edaravone, an ROS scavenger widely used in ischemic stroke, has been reported to effectively alleviate brain edema and neuronal apoptosis in ICH animal models [10, 11]. Notably, the results of phase II clinical trials of multitarget drugs targeting oxidative stress, including rosuvastatin and NXY-059, are promising [12, 13]. As such, targeting oxidative stress may represent a valuable approach to delay or prevent ICH progression.

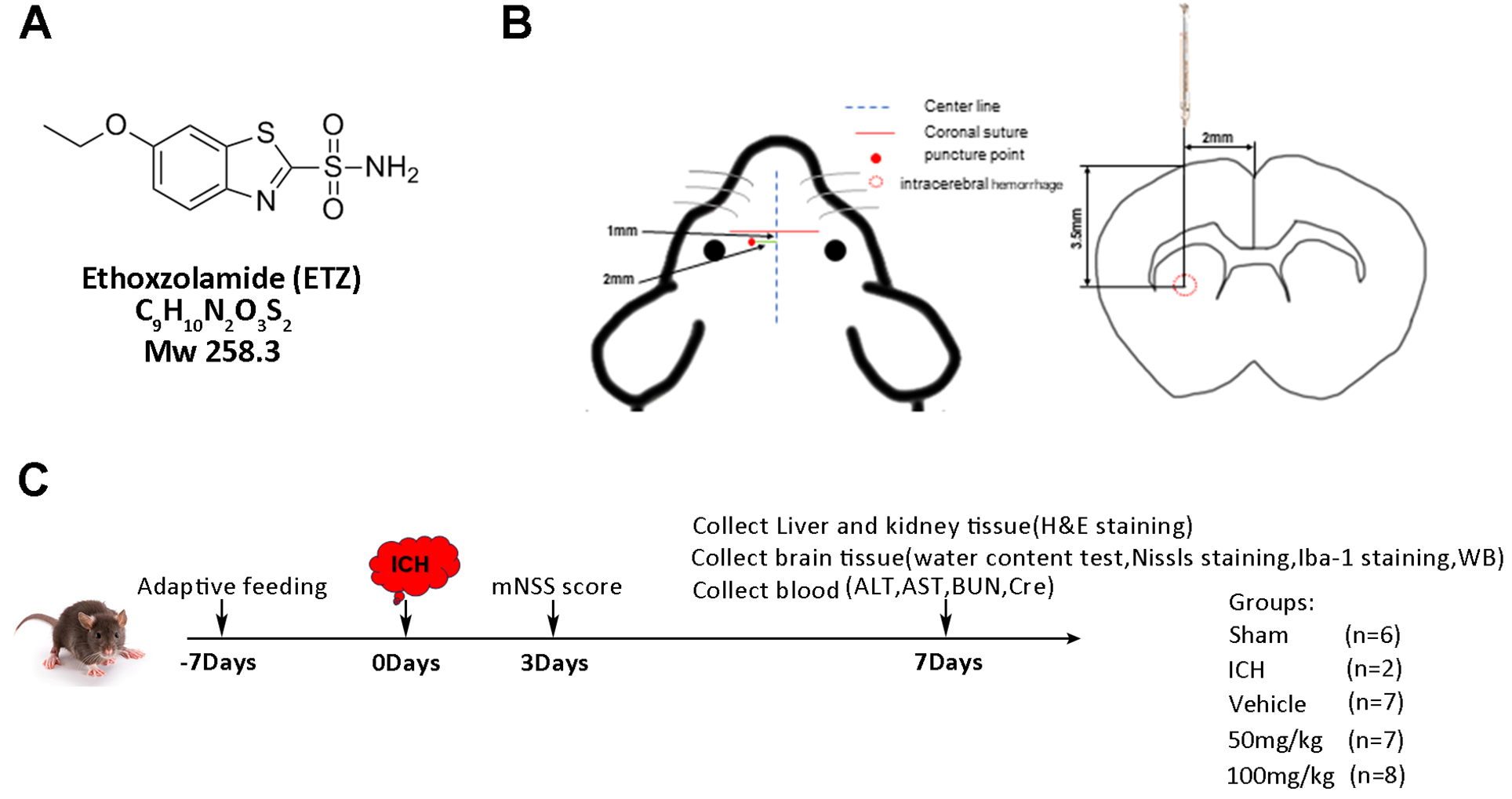

Carbonic anhydrase inhibitors are a class of compounds widely applied in medicine and agriculture to inhibit carbonic anhydrase activity [14]. Carbonic anhydrase is an enzyme found in many organisms that is involved in a number of important physiological processes, including cellular respiration, oxygenation, and acid-base homeostasis [15]. Carbonic anhydrase inhibitors have further been reported to restrain carbonic anhydrase activity by binding to this enzyme and blocking its catalytic reaction [16]; this class of inhibitors are widely used in drug development. As carbonic anhydrase plays a key role in a variety of diseases, such as cancer, hypertension, and glaucoma, inhibiting carbonic anhydrase could be a treatment option for these diseases [17, 18, 19]. Significant progress has been made in the use of sulfonamides as carbonic anhydrase inhibitors for anti-tumor, anti-neurological damage, and treatment of ICH and other diseases. Stella et al. [20] previously demonstrated that carbonic anhydrase is expressed in different cells of the central nervous system and is involved in the regulation of cerebral blood flow (CBF). Acetazolamide is a non-competitive inhibitor of carbonic anhydrase that has been shown to exert therapeutic effects on CBF, intracranial pressure, and brain tissue oxygenation in patients with subarachnoid hemorrhage, cerebral hemorrhage, traumatic brain injury, and hypoxic-ischemic encephalopathy. Chiu et al. [21] further showed that acetazolamide attenuated some of the sequelae associated with ICH by inhibiting the production of reactive oxygen species via astrocytes and microglia. Shah et al. [22] further proposed that carbonic anhydrase inhibitors protect the brain from oxidative stress and pericyte loss, thereby facilitating protection from oxidative stress caused by reactive oxygen species produced as a result of hyperglycemia-induced enhanced respiration. Ethoxzolamide (ETZ) (Fig. 1A), a novel carbonic anhydrase inhibitor, is a semi-synthetic aminoglycoside antibiotic clinically used to treat respiratory, urinary tract, and intra-abdominal infections caused by sensitive bacteria [23]. Studies on ETZ are limited, and its therapeutic effects on ICH have not yet been reported. Accordingly, the present study hypothesized that ETZ, a novel carbonic anhydrase inhibitor, would exert anti-ICH effects similar to those of other carbonic anhydrase inhibitors such as acetazolamide.

Fig. 1.

Fig. 1.

Experimental protocol and design. (A) Chemical structure, formula, and molecular weight of ETZ. (B) Schematic of the autologous blood injection method. (C) Experimental timeline. mNSS, Mouse neurological severity score; ICH, intracerebral hemorrhage; H&E, hematoxylin and eosin; ALT, alanine aminotransferase; AST, aspartate aminotransferase; BUN, blood urea nitrogen; Cre, creatinine.

The aim of this study was to investigate whether ETZ exerts a reparative effect on nerve injury in an experimental mouse model of ICH, and to explore the potential underlying protective mechanisms. Specifically, a mouse experimental ICH model was produced and intervened with intraperitoneal injection of different doses of ETZ, after which the effects of ETZ on hemorrhagic foci size, neurological function, neuronal demodulation, inflammatory infiltration, oxidative damage, liver and kidney function, and other related aspects were investigated. The final aim of this study was to provide a new line of thought for ICH clinical treatment.

A total of 60 male C57BL/6J mice were acclimatized and fed for one week before all experimental treatments were initiated. The ICH model was established using the autologous blood injection method, the day of surgery was recorded as day 0, and acclimatization culture was performed 7 days prior to surgery (day 7). There were 12 mice in the sham group, and 48 were used to establish the ICH model and randomly divided into three groups (n = 16 per group): ICH+vehicle, ICH+ETZ (50 mg/kg), and ICH+ETZ (100 mg/kg).

The modeling method was as follows. Mice were anesthetized by isoflurane (3% for induction and 1–2% for maintenance, Baxter Healthcare Co. Deerfield, IL, USA) based on a commercially available rodent inhalation anaesthesia apparatus (Provet, Lyssach, Switzerland). As carrier gas, 100% oxygen was used at a flow rate of 400 mL/min. The anaesthetic gas was introduced into the nose mask (inner diameter 1.2 cm) through a thin tube (outer diameter 0.4 cm, inner diameter 0.3 cm). The opening of the thin tube was at a distance of exactly 0.5 cm from the latex membrane, which had a hole in the centre that fit around the nose of the mouse. The nose of the mouse was placed 2 mm in front of the opening of the inner tube. The nose mask merged into a thick outer tube (surrounding the thin inner tube), which allowed waste anaesthetic gas to be eliminated from the nose mask by a pump-driven filter system (flow rate 400 mL/min). The same principle was utilized for the induction chamber (inflow and outflow 400 mL/min). Then, mice were fixed on a brain stereotaxic apparatus. The skin was incised 2 mm to the right of the mouse centerline and 1 mm below the coronal suture to expose the fontanelle. Then, a small hole with a diameter of about 1 mm was drilled with a dental bone drill at 3.5 mm to the right of the fontanelle and 1 mm in front of the fontanelle, and 100 µL of autologous blood was injected vertically with a micro syringe after blood was drawn from the right femoral artery (Fig. 1B). In the Sham group, the needle was inserted without blood injection.

The experimental design is shown in Fig. 1C. In the ICH+vehicle group, 100 µL of 0.25% carboxymethyl cellulose was injected intraperitoneally into the ICH mice once daily for one week. For the ICH+ETZ (50 mg/kg) and ICH+ETZ (100 mg/kg) groups, 50 and 100 mg/kg ETZ (CAS: 452-35-7, TargetMol, Boston, MA, USA) (dissolved in 100 µL of 0.25% carboxymethyl cellulose) were injected intraperitoneally into ICH mice daily for one week. Mice in the sham groups were intraperitoneally injected with 100 µL of 0.25% carboxymethyl cellulose once daily for one week. Mice in each group were scored for modified nerve injury severity on day 3 after modeling, while the blood, brain tissues, liver, and kidney tissues were collected from mice after being anesthetized with 3% isoflurane and perfused intracardially with 4% paraformaldehyde (Sigma-Aldrich, St Louis, MO, USA) in 0.1 mol/L phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) on day 7 for the follow-up study. Five ICH mice died because of excessive hematoma before day 7 (three mice from the ICH+vehicle group and two from the ICH+ETZ (50 mg/kg) group). All animal experimental protocols were reviewed and approved by the Institutional Animal Care Committee of Minhang Hospital, Fudan University (No. 2023026).

The mouse brain was cut and divided equally into three pieces (front, middle,

and back) to measure the wet weight. Subsequently, the brains were baked in an

oven at 95 °C and then weighed to obtain the dry weight. The water content of the

brain tissue was calculated according to the following formula: (wet weight –

dry weight)/wet weight

Neurological function was scored using a double-blind method, with reference to the modified mouse neurological deficit scoring (mNSS) criteria, which includes four areas: motor tests, sensory tests, loss of reflexes and abnormal movements, epilepsy, muscle spasms, and dystonia. Neurological function was graded on a scale of 0–18, with lower scores indicating greater functionality; 0 indicating normal mice, and 14 indicating mice with maximal functional deficits.

Nissl staining provides insight into neuronal damage through the staining Nissl bodies. This technique was used to stain the brain tissue of each group in this study. In brief, mouse brains were transferred to a frozen slicer and rewarmed for at least 20 min before slicing. Subsequently, 200 µm coronal slices were obtained, dried at 40~50 °C for 2~3 h, air-dried at room temperature, submerged in 4% paraformaldehyde solution for fixation, and placed in the refrigerator at 4 °C overnight. After washing away the paraformaldehyde, the sections were placed in PBS containing 0.5% TritonX 100 (Sigma-Aldrich, St Louis, MO, USA) for 2 h to break the membrane. After Nissl staining for 30 min at room temperature, the sections were immersed twice in distilled water, followed by gradient dehydration. After air drying, the samples were observed under a microscope and photographed.

Measures of total antioxidant capacity (TAC, mlbio, Shanghai,

China), malondialdehyde (MDA, Cat#BC0020, Solarbio, Beijing, China), superoxide

dismutase (SOD, Cat#BC0175, Solarbio, Beijing, China), glutathione (GSH,

Cat#S0053, Solarbio, Beijing, China), tumor necrosis factor-

The mouse brain sections were sequentially subjected to deparaffinization, hydration, antigen recovery, serum blocking, incubation with the primary antibody (ab178846, Abcam, UK) and the corresponding secondary antibody, washing, diaminobenzidine (DAB) color development, hematoxylin counterstaining, and mounting. Under the microscope, three high-magnification fields of view were randomly selected for each section to detect the expression and localization of the microglial marker Iba-1 in the brain tissue.

Liver and kidney tissues were collected from each group of mice, and fixed with 4% paraformaldehyde at 4 °C for one week. After paraffin embedding and wax block sectioning, the tissues were stained with HE according to the manufacturer’s instructions (G. Fan, Shanghai, China). Sections were blocked by ethanol dehydration, and staining was observed under an inverted fluorescence microscope (IX53, Olympus Corporation, Tokyo, Japan).

The three-dimensional (3D) structure of Kelch-like ECH-associated protein 1 (Keap1) was obtained from the PDB database (https://www.rcsb.org/), selected based on the following principles: human protein, high resolution (less than or equal to 2.5 Å), having the original ligand, and crystallization pH should be as close as possible to the normal physiological range of the human body. The ETZ molecular structure was downloaded from the PubChem database (https://pubchem.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov), and the 3D stereostructure of the small molecule was drawn using ChenDraw. Finally, the Keap1 protein and ETZ small molecules were docked using AutoDock Vina 1.2.0 (Scripps Research Institute, San Diego, CA, USA) and visualized in PyMOL v.2.4 (Schrodinger Inc, New York, NY, USA) .

Target proteins in the cytoplasmic and/or nuclear fractions of brain tissue were obtained and quantified. The 20 µg/mL of nuclear/plasmic proteins was treated with 10% sodium dodecyl-sulfate polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (SDS-PAGE), and transferred to a polyvinylidene fluoride (PVDF) membrane, which were incubated with primary antibody separately overnight at 4 °C, and the antibody information is displayed in Supplementary Table 1. The membranes were subsequently incubated with horseradish peroxidase (HRP)-labelled goat anti-rabbit/mouse IgG antibody at room temperature for 2 h. Finally, protein expression was detected using excellent chemiluminescent substrate (ECL) reagents for chromogenic detection, and the protein gray scale was statistically analyzed using ImageJ software v1.45 (National Institute of Health; Bethesda, MD, USA).

Data were processed using SPSS 22.0 (IBM Corp., Armonk, NY, USA), and presented

as the mean

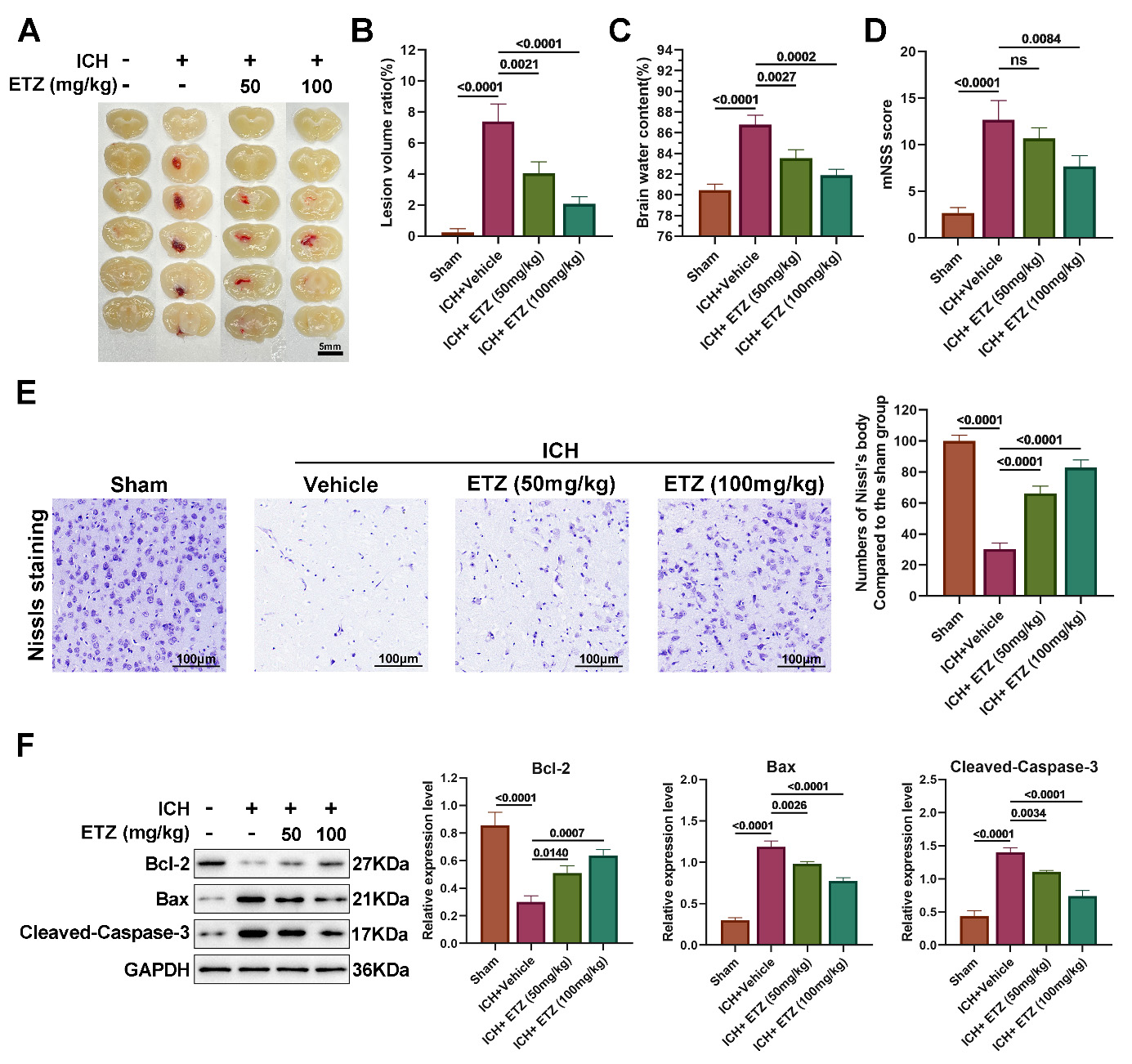

Typical macroscopic brain section images obtained from each group of experimental mice showed that a large number of hemorrhagic foci were visible in the ICH model group, whereas the volume of hemorrhagic foci was reduced in the ETZ-injected group, with the most pronounced effect observed in the 100 mg/kg group (Fig. 2A,B). Furthermore, examination of the water content of the mouse brain specimens in each group revealed that the water content in the ICH+Vehicle group was conspicuously increased compared to the sham group, whereas ETZ injection decreased the water content in a dose-dependent manner (Fig. 2C). Additionally, mouse neurological function scoring was performed with reference to the modified Mouse neurological severity score (mNSS) criteria for motor tests, sensory tests, loss of reflexes and abnormal movements, epilepsy, muscle spasms, and dystonia. The results revealed that the mNSS scores increased to approximately 12 after ICH modeling, and gradually decreased after ETZ injection, indicating that ETZ treatment could improve neurological deficits in mice (Fig. 2D). Next, the neurons were stained with Nissl stain to observe neuronal damage. As shown in Fig. 2E, the sham group presented with large and numerous Nissl bodies, reflecting the strong protein synthesis function of neuronal cells. In contrast, the number of Nissl bodies in the ICH model group was significantly reduced or almost disappeared, indicating severe neuronal damage. Following the administration of ETZ, the number and size of Nissl bodies gradually increased, and neuronal damage recovered (Fig. 2E). Subsequently, the expression of apoptosis-related proteins was assessed to further analyze whether ETZ affected neuronal apoptotic injury. The results of Western blotting showed that the expression of the apoptotic proteins Bcl-2 Associated X-protein (BAX) and Cleaved-caspase-3 was significantly upregulated, while the expression of the anti-apoptotic protein Bcl-2 was decreased in the brain tissues of the ICH model group, which was reversed by ETZ injection in a dose-dependent manner (Fig. 2F). This suggests that ETZ can attenuate ICH-induced neuronal damage and apoptosis as well as pathological dysfunction to a certain extent.

Fig. 2.

Fig. 2.

ETZ reduces neurological and pathological deficits induced by

intracerebral hemorrhage (ICH). (A) Representative brain sections; (B) Lesion

volume; (C) Brain water content; (D) Modified mouse neurological deficit scoring

(mNSS) score estimation of neurological function; and (E) Nissl staining

estimation of neuronal damage in the brains of ICH model mice injected

intraperitoneally with ETZ (50 or 100 mg/kg; n = 3, Scale bar = 100 μm.). (F) Western blot analysis of

BAX, Cleaved-caspase-3, and Bcl-2 protein levels in the mouse brains

intraperitoneally injected with ETZ (50 or 100 mg/kg); n = 3. Data: Mean

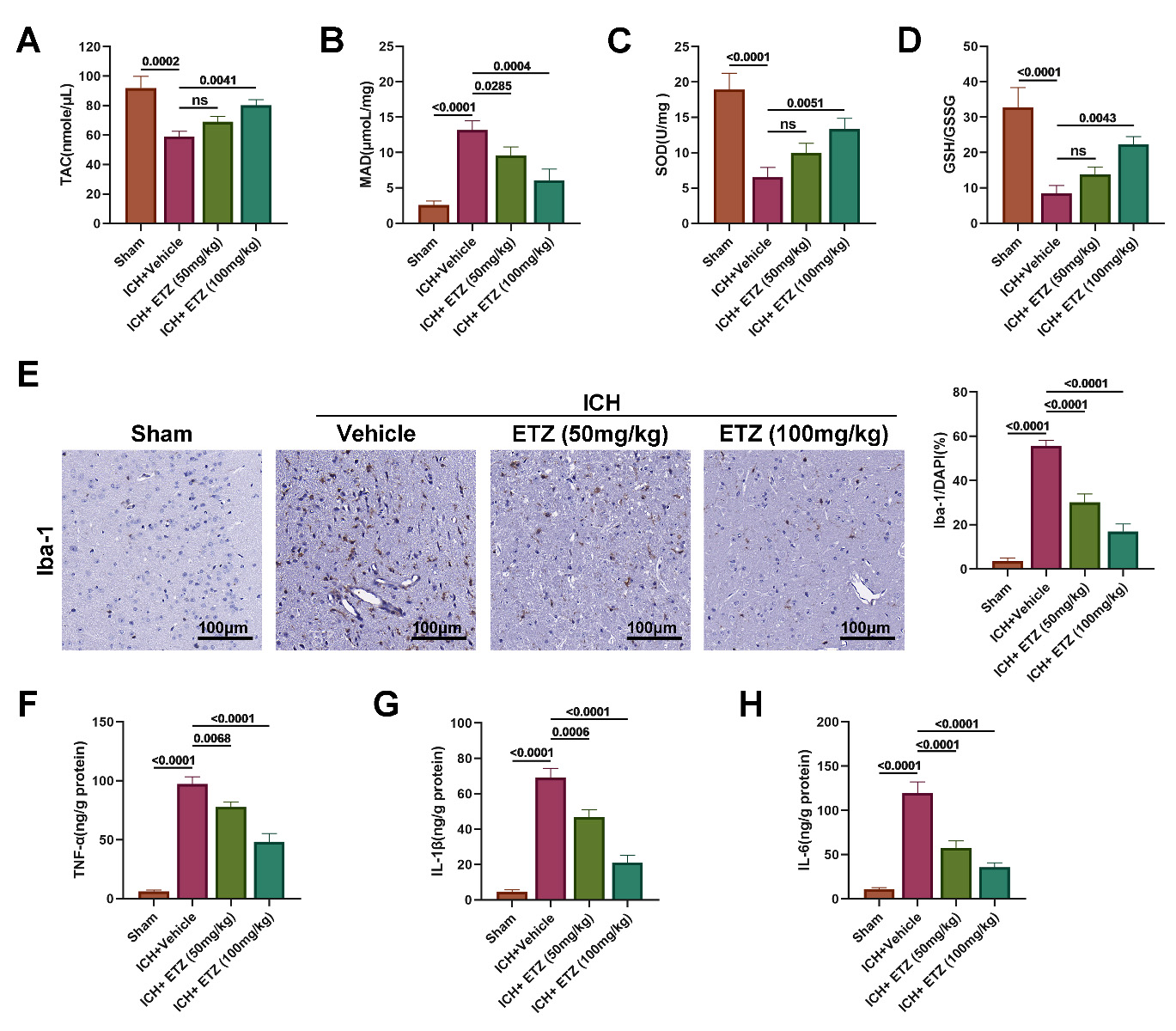

Previous studies [24, 25] have identified biological responses following cerebral

hemorrhage in the form of inflammatory factor expression, microglial activation,

and oxidative factor infiltration, which directly damage neurons, and are

important for the formation of brain tissue edema. Accordingly, the present study

further examined oxidative damage, inflammation, and microglial activation in the

brain tissues of mice in all groups. The results revealed a decrease that the

content of the antioxidant indicators TAC, SOD, and glutathione (GSH)/oxidized glutathione (GSSG) (Fig. 3A–D), while

the content of the oxidative damage indicator MDA was prominently increased in

the brain tissues of ICH mice, indicating the presence of oxidative damage in ICH

mice. However, we further observed a dose-dependent increase in the content of

the antioxidant indicators TAC, SOD, and GSH/GSSG, as well as a dose-dependent

decrease in the content of the oxidative damage indicator MDA in the brain tissue

of mice administered ETZ. In addition, the expression of the microglial

activation marker Iba-1 was markedly increased in brain tissue sections from ICH

mice compared to the sham group, while Iba-1 positivity was reduced following ETZ

treatment in a dose-dependent manner (Fig. 3E). Further tests on inflammatory

factors revealed that the levels of pro-inflammatory factors TNF-

Fig. 3.

Fig. 3.

ETZ alleviates ICH-induced oxidative stress and

neuroinflammation in mice. Enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA)measurements of (A) total antioxidant capacity (TAC); (B) malondialdehyde (MDA);

(C) superoxide dismutase (SOD); (D) glutathione (GSH)/oxidized glutathione

(GSSG) content in the brains of ICH model mice injected intraperitoneally with

ETZ (50 or 100 mg/kg; n = 6). (E) Immunohistochemical measurement of Iba-1

expression in ICH mouse brains injected intraperitoneally with ETZ (50 or 100

mg/kg; n = 3). (F) ELISA measurement of tumor necrosis factor-

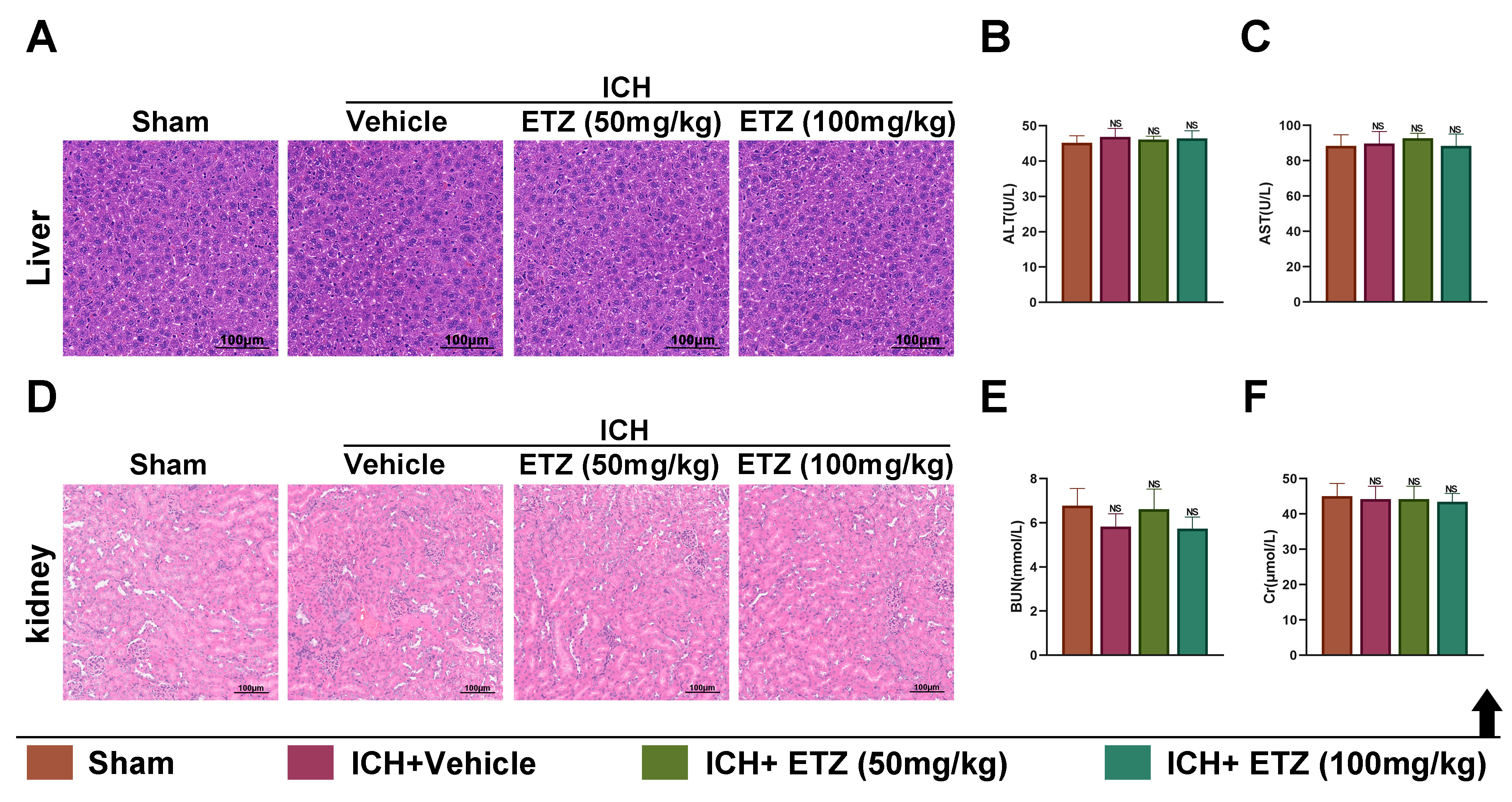

Before it can be used in humans, it is essential to explore the biosafety of ETZ; thus, HE staining and related functional indices were performed after collecting the liver, kidney, and serum from each group of mice to investigate the hepatorenal toxicity of ETZ. Pathological staining of liver sections revealed that the histopathological morphology of the liver was similar in all groups of mice, with no significant differences (Fig. 4A). There were also no significant changes in the liver function indices ALT (Fig. 4B) and AST (Fig. 4C). Similarly, renal histopathological morphology (Fig. 4D) and the renal function indicators BUN (Fig. 4E) and Cr (Fig. 4F) showed no significant changes among the four groups of mice. Overall, these results indicate that ETZ has good biosafety, exerting no significant burden on the liver and kidneys.

Fig. 4.

Fig. 4.

In vivo biosafety assessment of ETZ. (A) Hematoxylin and eosin (HE)

measurement of pathological changes in liver tissue sections of ICH mice injected

intraperitoneally with ETZ (50 or 100 mg/kg), scale bar: 100 µm. Automatic

biochemical analyzer detection of (B) alanine aminotransferase (ALT) levels; and

(C) aspartate aminotransferase (AST) levels in the serum of ICH mice injected

intraperitoneally with ETZ (50 or 100 mg/kg); n = 6. (D) HE measurement of pathological changes in renal tissue sections of ICH mice

injected intraperitoneally with ETZ (50 or 100 mg/kg), scale bar: 100 µm.

Automatic biochemical analyzer detection of (E) blood urea nitrogen (BUN) content

and (F) creatinine (Cr) content in the serum of ICH mice injected

intraperitoneally with ETZ (50 or 100 mg/kg); n = 6. Data: Mean

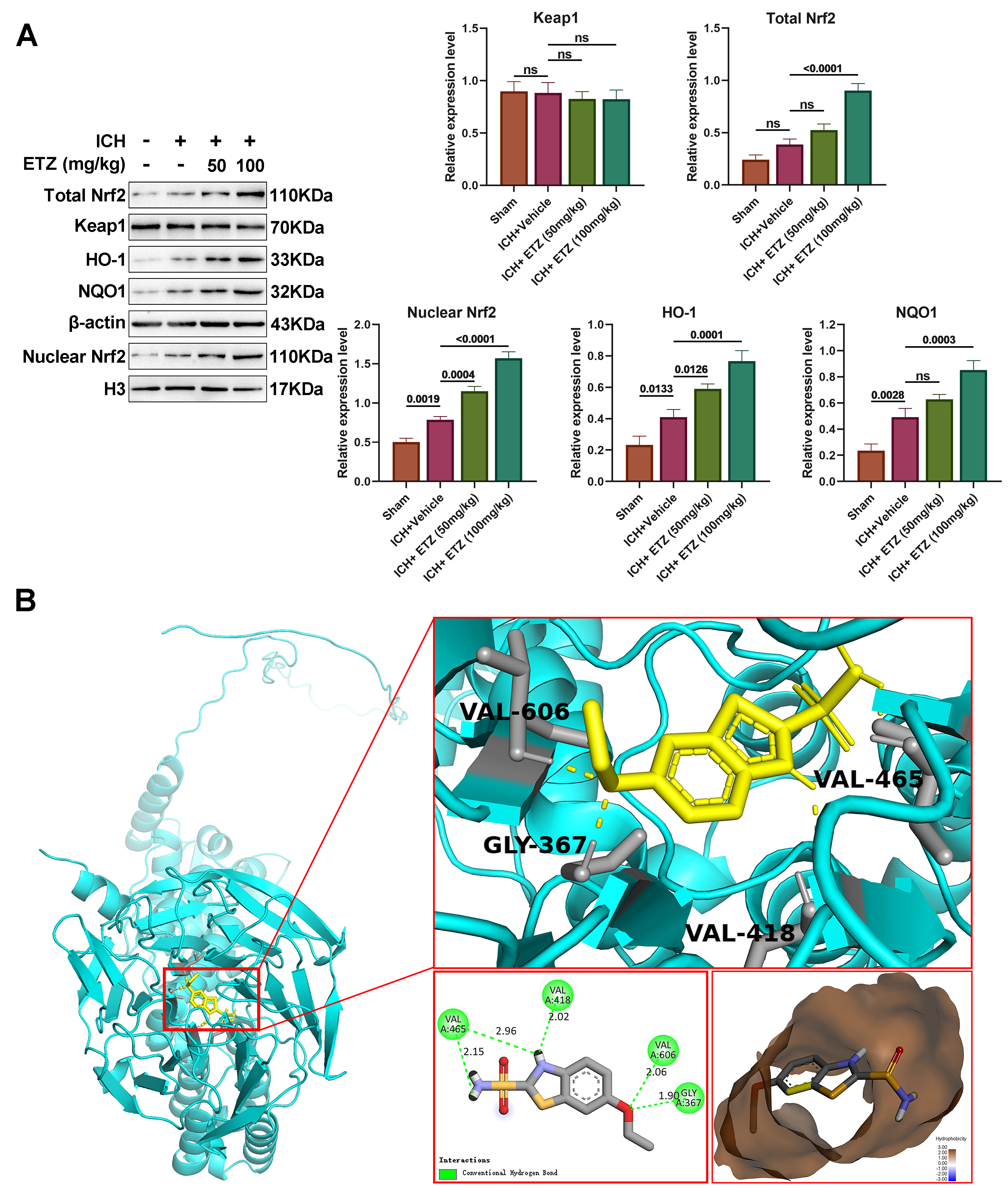

The Keap1/Nrf2 pathway is a core regulatory center of the antioxidant defense system which plays an important role in the amelioration of secondary injury. Studies have shown that the Keap1/Nrf2 pathway is activated to counteract secondary oxidative damage following ICH. In this study, we examined the expression of the Keap1/Nrf2 pathway-associated proteins in the brain tissues of mice from all groups, finding that total Nrf2, nuclear Nrf2, heme oxygenase-1 (HO-1), and NAD(P)H quinone dehydrogenase 1 (NQO1) proteins were slightly upregulated in the brain tissues of ICH mice, in addition to the Keap1 protein, which was further increased following the administration of ETZ in a dose-dependent manner (Fig. 5A). This suggests that treatment with ETZ following ICH activated the Keap1/Nrf2 pathway. Subsequently, we performed molecular docking analysis of Keap1 and ETZ, which revealed that ETZ was able to bind tightly to the Valine (VAL)-606, VAL-465, Glycine (GLY)-367, and VAL-418 amino acid sites in Keap1 (Fig. 5A), for which the binding energies were all less than –5 kcal/mol, while the action distances were 2.06 Å, 2.15 Å, 1.90 Å, and 2.02 Å, respectively, which proved that the drug binds well to the target site through hydrogen bonding (Fig. 5B). Taken together, these results indicate that ETZ exerts antioxidant, anti-inflammatory, and anti-apoptotic effects in ICH mice by docking with the Nrf2-binding domain of keap1 to further activate the Keap1/Nrf2 pathway.

Fig. 5.

Fig. 5.

ETZ regulates the Kelch-like ECH-associated protein 1 (Keap1)/nuclear factor erythroid 2-related factor 2 (Nrf2) signaling in ICH mice. (A)

Western blot analysis of total Keap1, Nrf2, nuclear Nrf2, heme oxygenase-1

(HO-1), and NAD(P)H quinone dehydrogenase 1 (NQO1) protein levels in ICH mouse

brains injected intraperitoneally with ETZ (50 or 100 mg/kg); n = 3. (B) 3D map

of the molecular docking of ETZ with Keap1. Data: Mean

Despite its high prevalence, there are still no effective treatments for ICH [26]. Hemorrhagic brain injury occurs not only as a result of a primary injury caused by the occupying effect of the hematoma itself and the direct destruction of the tissues surrounding the hematoma; in fact, secondary brain injury also plays an indispensable role in the prognosis of patients with ICH [27]. In the present study, we found that ETZ administered via intraperitoneal injection significantly attenuated early brain tissue damage following ICH, as evidenced by a reduction in the mNSS scores of behavioral deficits, amelioration of histological damage and cerebral edema around the hematoma, attenuation of neuronal injury and apoptosis, inhibition of oxidative factor levels, and microglial activation-mediated inflammatory infiltration.

Currently, ICH model construction methods include collagenase injection, autologous blood injection, microballoon puncturing of blood vessels in the brain, and etiology-specific model methods. Among these, the autologous blood injection method is the most widely applied, as this can better simulate the ICH model allowing the mechanistic investigation of the destruction of brain tissues around the hematoma by blood components after ICH [28]. The male mouse autologous blood injection model was chosen for this experiment, which has the advantages of being inexpensive, easy to manage, with a low mortality rate, ease of model construction, cerebral vascular anatomy similar to that of humans, and a smaller brain volume to facilitate experimental observation in histopathology and biochemistry [29]. Males were chosen primarily because of the male predominance of ICH, as well as the protective effect of estrogen on brain tissue [30].

As antioxidant and anti-inflammatory agents, carbonic anhydrase inhibitors may exert potentially useful therapeutic effects after central nervous system trauma, including ICH [31]. Acetazolamide, a carbonic anhydrase inhibitor, has been found to reduce ICH-induced brain water content and neuronal death, as well as improve functional prognosis [32]. Consistently, the present study demonstrated that large hemorrhagic foci and a significant increase in brain water content were observed in the ICH model group, while the injection of ETZ reduced the amount of brain hemorrhage and water content in a dose-dependent manner. Furthermore, the murine neurological function score was referenced to the mNSS criteria for motor tests, sensory tests, absent and abnormal reflexes and movements, epilepsy, muscle spasms, and dystonia [33]. The results revealed a significant increase in mNSS scores after ICH modeling, as well as a gradual decrease in scores following ETZ injection, indicating that ETZ treatment improved neurological deficits in mice. Canepa et al. [34] further reported that both carbonic anhydrase inhibitors (methazolamide and acetazolamide) attenuated cerebral gliosis and improved cognition in TgSwDI mice, indicating that carbonic anhydrase inhibitors protect cerebral neurologic function.

Prior studies have shown that apoptosis in animal experiments may play a key role in the pathogenesis of early brain injury [35, 36]. The early apoptotic cascade after brain injury occurs in both brain cells (neurons, astrocytes, and oligodendrocytes) and cerebral vessels (smooth muscle and endothelial cells) [37]. As expected, our experimental results revealed that the expression of the apoptotic proteins BAX and Cleaced-caspase-3 were up-regulated, while the expression of anti-apoptotic protein Bcl-2 was decreased in the brain tissues of mice in the ICH model group. The expression of all three proteins was reversed by the injection of ETZ in a dose-dependent manner, suggesting that ETZ could attenuate the neuronal apoptosis induced by ICH to a certain extent. Li et al. [38] previously demonstrated that the expression of active caspase-3 was observably reduced in subarachnoid hemorrhage (SAH) mice treated with the carbonic anhydrase inhibitor mesylate, which could further accelerate recovery from neurological injury, effectively alleviate cerebral edema, and improve cognitive function in SAH mice. When ICH occurs, resulting in cellular damage, BAX proteins migrate to the mitochondria to promote the release of apoptotic factors, which can further contribute to the formation of apoptotic vesicles by binding caspase-9 to the multimer formed by cyt-c and the subsequent activation of caspase-3 to initiate apoptotic cell death [39]. Notably, during the caspase cascade reaction, caspase-3 acts as the key regulator of apoptosis, functioning as the final regulator and playing a central role in apoptosis regulation [40].

Microglia are key innate immune cells in the brain, and are thought to be the

first cells to respond to various acute brain injuries, including ICH [24]. In

rodents with collagenase and autologous blood-induced ICH models, secretion of

the pro-inflammatory cytokines IL-1

Oxidative stress is induced by the accumulation of ROS, which mediates the

inflammatory response following ICH. In the context of ICH, ROS-induced

activation of the inflammasome causes the secretion of IL-1

It is well known that the Keap1/Nrf2 pathway acts as a central regulatory hub of cellular antioxidant and anti-inflammatory machinery, playing an indispensable role in the amelioration of secondary injury [47, 48]. Natural antioxidants such as curcumin and sulforaphane effectively increase antioxidant enzyme gene expression in the brain tissues after ICH, whereas the silencing of Keap1/Nrf2 aggravates cerebral edema and neuronal degeneration, resulting in increased hemorrhage, leukocyte infiltration, ROS production, and DNA damage [48]. It has further been suggested that the Keap1/Nrf2 pathway is activated following ICH to counteract secondary oxidative damage. Our results showed that the intraperitoneal administration of ETZ after ICH activated the Keap1/Nrf2 pathway, which may be one of the mechanisms by which ETZ alleviates ICH injury. To understand the potential mechanism underlying the regulatory role of ETZ in the Keap1/Nrf2 pathway, we performed molecular docking, a theoretical approach to study the interaction and recognition between protein receptors and small-molecule ligands [49], to predict the interaction between ETZ and Keap1. Nrf2 is present in the cytoplasm as an inactive complex bound to Keap1 (a repressor molecule), facilitating its ubiquitination. Keap1 further contains several reactive cysteine residues that serve as sensors of the intracellular redox state [50]. The covalent modification of thiols in some of these cysteine residues causes the dissociation of Nrf2 from Keap1, resulting in its subsequent translocation to the nucleus [51]. Our data showed that ETZ could bind tightly to the VAL-606, VAL-465, GLY-367, and VAL-418 amino acid sites in Keap1, which may explain the regulation of the Keap1/Nrf2 pathway by ETZ.

However, this study had several limitations. First, the absorption pathway, effective site, and metabolic form of ETZ are crucial for evaluating the efficacy and safety of the drug, and should be further investigated. In addition, as the autologous blood injection model used in this study may not perfectly mimic the chronic and long-term outcomes of ICH, we primarily focused on the early phase of ICH. Hence, long-term studies based on other suitable ICH models are required to understand the chronic effects and the potential for recovery over extended periods. Moreover, the animal experiments in this study were insufficient to fully confirm that Keap1/Nrf2 is the target of ETZ in ICH treatment, and in-depth studies on the role of Keap1/Nrf2 inhibitors or activators in combination with ETZ in ICH are needed to provide a solid theoretical basis for the search for potential treatments for ICH. Finally, to understand sex-specific responses to hormonal differences, it will be necessary to validate these findings in female mice in the future.

Accordingly, the present study concluded that ETZ, a novel carbonic anhydrase inhibitor, could further activate the Keap1/Nrf2 pathway by docking with the Nrf2-binding domain of keap1, thereby exerting antioxidant, anti-inflammatory, anti-apoptotic, and cerebral neuroprotective effects in ICH mice. Overall, the results of this study present ETZ as a potential novel therapeutic strategy for ICH.

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

YXL, GS, and ZPS made substantial contributions to the conception and design of the work. Material preparation, data collection, and analysis were performed by JRD and WD. YXL and GS drafted the manuscript, while JRD and WD provided critical revisions. ZPS reviewed it critically for important intellectual content. YXL, GS, JRD, WD, and ZPS contributed to editorial changes in the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript. All authors have participated sufficiently in the work and agreed to be accountable for all aspects of the work.

All animal experimental protocols were reviewed and approved by the institutional animal care committee of Minhang Hospital, Fudan University. The ethics approval number is 2023026.

Not applicable.

This work was supported by Shanghai Minhang District Health Commission Project (2022MHZ062).

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Supplementary material associated with this article can be found, in the online version, at https://doi.org/10.31083/j.fbl2910356.

References

Publisher’s Note: IMR Press stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.