1 Department of Pharmaceutical Sciences, Laboratory for the Study of Neurohormonal Control of the Circulation, Nova Southeastern University Barry and Judy Silverman College of Pharmacy, Davie/Fort Lauderdale, FL 33328-2018, USA

Abstract

The sympathetic nervous system (SNS) consists largely of two different types of components: neurons that release the neurotransmitter norepinephrine (NE, noradrenaline) to modulate homeostasis of the innevrvated effector organ or tissue and adrenal chromaffin cells, which synthesize and secrete the hormone epinephrine (Epi, adrenaline) and some NE into the blood circulation to act at distant organs and tissues that are not directly innervated by the SNS. Like almost every physiological process in the human body, G protein-coupled receptors (GPCRs) tightly modulate both NE release from sympathetic neuronal terminals and catecholamine (CA) secretion from the adrenal medulla. Regulator of G protein Signaling (RGS) proteins, acting as guanosine triphosphatase (GTPase)-activating proteins (GAPs) for the Gα subunits of heterotrimeric guanine nucleotide-binding proteins (G proteins), play a central role in silencing G protein signaling from a plethora of GPCRs. Certain RGS proteins and, in particular, RGS4, have been implicated in regulation of SNS activity and of adrenal chromaffin cell CA secretion. More specifically, recent studies have implicated RGS4 in regulation of NE release from cardiac sympathetic neurons by means of terminating free fatty acid receptor (FFAR)-3 calcium signaling and in regulation of NE and Epi secretion from the adrenal medulla by means of terminating cholinergic calcium signaling in adrenal chromaffin cells. Thus, in this review, we provide an overview of the current literature on the involvement of RGS proteins, with a particular focus on RGS4, in these two processes, i.e., NE release from sympathetic nerve terminals & CA secretion from adrenal chromaffin cells. We also highlight the therapeutic potential of RGS4 pharmacological manipulation for diseases characterized by sympathetic dysfunction or SNS hyperactivity, such as heart failure and hypertension.

Keywords

- catecholamine secretion

- chromaffin cell

- free fatty acid receptor-3

- G protein-coupled receptor

- norepinephrine release

- regulator of G protein signaling-4

- signal transduction

- sympathetic nervous system

G protein-coupled receptors (GPCRs) represent the most diverse and populated

cell membrane receptor superfamily, with ~350 (non-sensory)

members mediating regulation of all aspects of cell physiology by various

chemical molecules and hormones [1, 2, 3, 4]. The catecholamines (CAs) norepinephrine

(NE) and epinephrine (Epi) mediate all the actions of the sympathetic branch of

the autonomic nervous system (SNS), as a neurotransmitter released by sympathetic

neurons and a hormone secreted by the adrenal medulla, respectively [3]. NE is

also secreted alongside Epi from the adrenal gland but to a lesser extent [5].

Both NE and Epi exert their actions in cells through nine different adrenergic

receptor (AR) subtypes, all of which are cell membrane-residing GPCRs. In other

words, all ARs couple to heterotrimeric guanine nucleotide-binding proteins (G

proteins) to transduce their signals inside the cell [6]. These heterotrimeric G

proteins consist of four families: Gi/o, Gs/olf, Gq/11/14/15,

G12/13, based on the 16 different G

All GPCRs act as a guanine nucleotide exchange factors (GEFs) for the

G

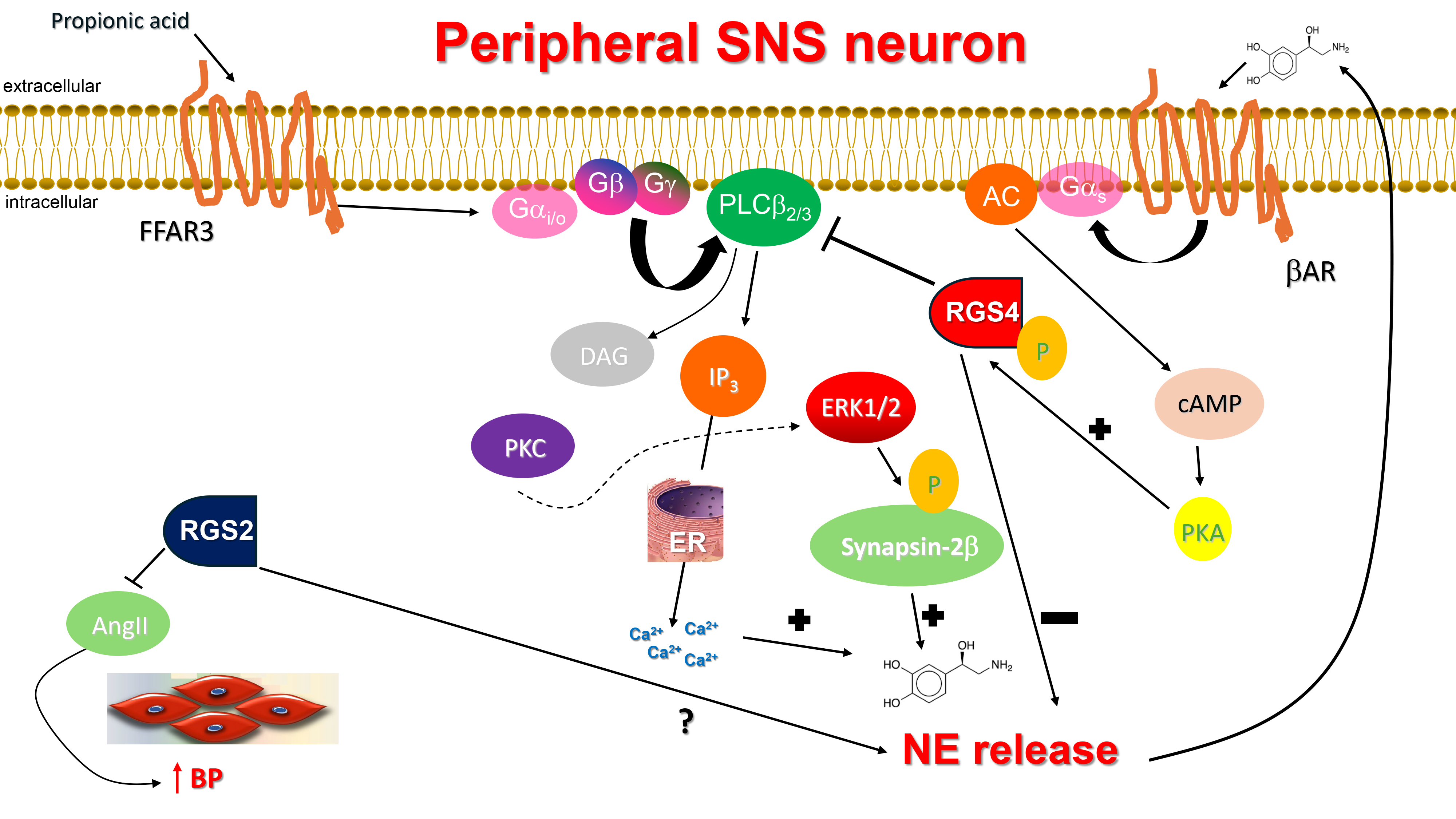

The roles of several RGS proteins, e.g., RGS6, RGS4, RGS2, in parasympathetic regulation of cardiac function, particularly in modulation of acetylcholine (ACh)-dependent bradycardia and slowing of atrial conduction, have been extensively documented [15, 16, 17, 18, 19, 20]. However, rather surprisingly, very little is known regarding regulation of sympathetic neuronal function/nerve activity (SNA) and NE release by RGS proteins. Studies on RGS2 knockout mice indicated that these animals display a hypertensive phenotype with central SNS activation, increased urinary NE levels, and impaired nitric oxide-mediated vasodilation [25, 26]. However, a later study failed to replicate these findings and reported indistinguishable circulating NE and Epi levels between RGS2 knockout and control wild type mice, as well as no change in mean blood pressure [27]. On the other hand, RGS2 ameliorates AngII-induced hypertension [28] and its levels can be reciprocally regulated by the vascular AT1R [29, 30, 31, 32]. Therefore, it is quite plausible that the effect of the genetic deletion of RGS2 on systemic hypertension is (primarily) mediated by elevated AngII signaling in the vasculature and not so much by elevated SNS activity and NE release. In any case, irrespective of the mechanism(s) involved, it appears that RGS2 plays a minimal (if at all) role in NE release from sympathetic neurons (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1.

Fig. 1.

RGS4 inhibits NE release from sympathetic neurons and & RGS2

reduces AngII secretion in the vasculature. AC, Adenylyl cyclase; AngII,

Angiotensin II; AR, Adrenergic receptor; BP, Blood pressure; cAMP, Cyclic 3′,

5′-adenosine monophosphate; DAG, 1′, 2′-Diacylglycerol; ER,

Endoplasmic reticulum; ERK1/2, Extracellular signal-regulated kinase-1/2;

Gαi/o, Inhibitory/other alpha subunit of heterotrimeric guanine

nucleotide-binding protein; Gαs, Stimulatory alpha subunit of

heterotrimeric guanine nucleotide-binding protein; IP3, Inositol 1′,

4′, 5′-trisphosphate; PKA, Protein kinase A; PKC, Protein kinase C;

PLC

In a recent study from our lab, RGS4 was shown to regulate NE release from

sympathetic-like neurons in vitro via its actions on the short chain

free fatty acid receptor (FFAR)-3, also known as GPR41, a GPCR that mediates

signaling by short chain (up to 5 carbon atoms) carboxylic acids, such as

propionate and butyrate [33]. FFAR3 is Gi/o protein-coupled GPCR robustly

expressed in murine peripheral sympathetic neurons, including cardiac SNS

terminals, wherein it regulates SNA/SNS firing by stimulating NE release [34]

(Fig. 1). Although both NE and Epi mediate the effects of the sympathetic nervous

system on all cells and tissues of the entire body, NE is the actual

neurotransmitter synthesized, stored, and released from sympathetic neurons,

since SNS neurons lack the enzyme phenyl-ethanolamine-N-methyltransferase (PNMT),

which converts NE to Epi [35, 36, 37]. FFAR3 promotes neuronal firing and NE synthesis

and release in SNS neurons via stimulation of Phospholipase C

(PLC)-

Finally, RGS4 can be activated via phosphorylation by protein kinase A (PKA),

the kinase activated by cyclic adenosine monophosphate (cAMP) produced by NE-activated

Notably, the ketone body

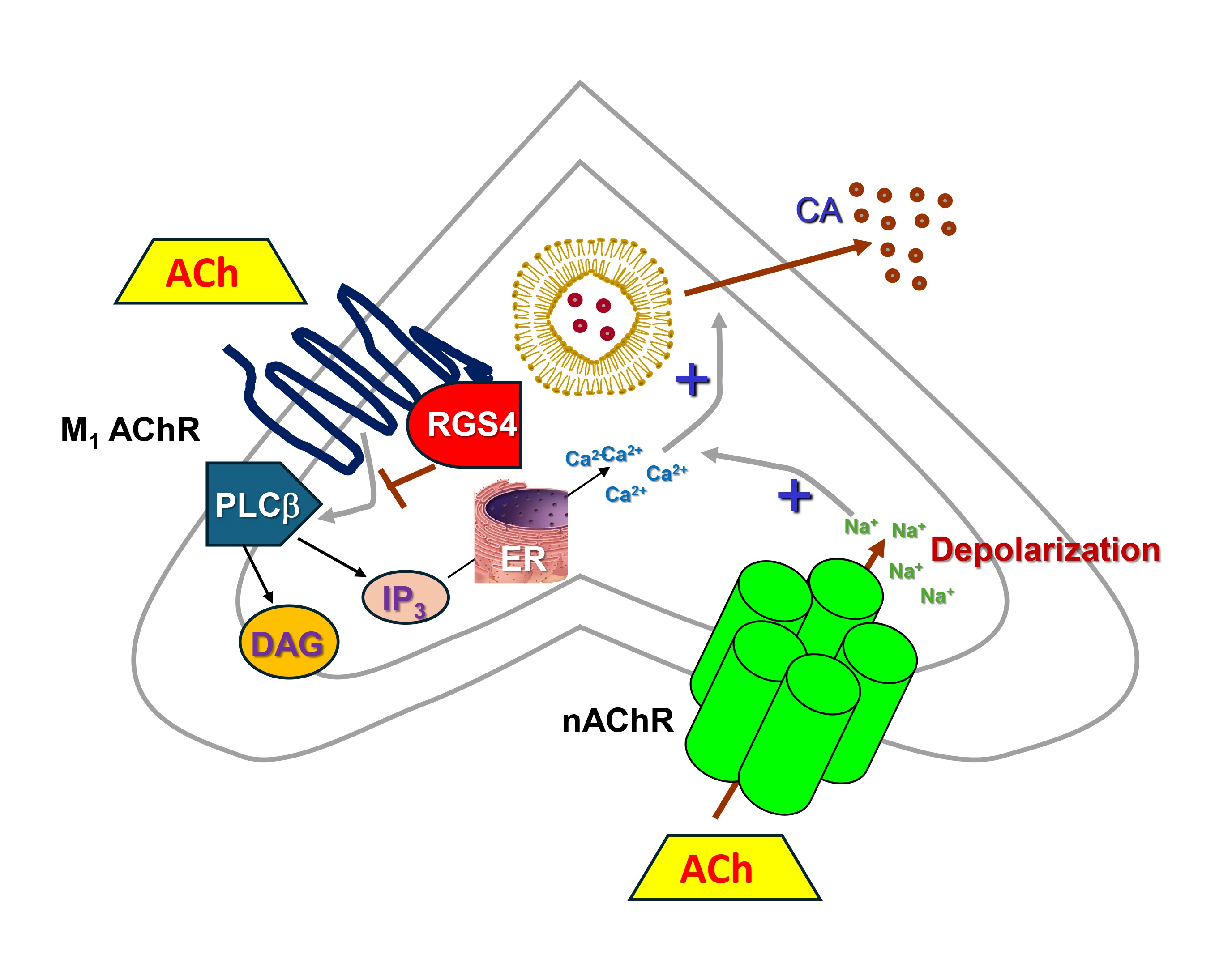

Certain RGS proteins, i.e., RGS4 and RGS2, play major roles in modulation of

adrenal CA secretion. Several Gq/11-coupled GPCRs, including muscarinic

M1 mAChRs and AT1Rs, that raise free intracellular Ca2+ levels act

as secretagogues for Epi and NE secretion from the chromaffin cells of the

adrenal medulla via the classic Ca2+-dependent process of

exocytosis/secretion [52, 53, 54, 55, 56, 57]. Interestingly, AT1R-dependent

Ca2+-dependent exocytosis leading to CA secretion can also be promoted by

the

Fig. 2.

Fig. 2.

RGS4 inhibits CA secretion in adrenal chromaffin cells. M1

AChR, Muscarinic cholinergic receptor type 1; nAChR, Nicotinic

cholinergic receptor; Ach, Acetylcholine; CA, Catecholamine (norepinephrine or

epinephrine); DAG, 1′, 2′-Diacylglycerol; ER, Endoplasmic reticulum;

IP3, Inositol 1′, 4′, 5′-trisphosphate; PLC

Of note, RGS4 has been shown to also inhibit AT1R-stimulated aldosterone synthesis and secretion via downregulation of aldosterone synthase (CYP11B2) expression in adrenocortical cells [67], an effect shared with RGS2 [68]. Interestingly, adrenal RGS2 can be upregulated by angiotensin II (AngII), so RGS2-dependent aldosterone secretion inhibition might serve as a negative feedback mechanism for AngII-induced aldosterone production [68]. However, unlike adrenocortical aldosterone production which has been shown to be blocked by both RGS2 and RGS4, RGS4 remains the only RGS protein reported to date to inhibit CA secretion from the adrenal medulla [57]. Indeed, RGS4 knockout mice exhibit elevated adrenal CA secretion but RGS2 knockout animals have apparently normal circulating Epi (and NE) levels [27], which, given that the adrenal gland is the sole source of circulating Epi, argues against a significant impact of adrenal RGS2 on CA secretion. Thus, adrenal CA secretion inhibition, coupled with its effects on aldosterone secretion from the cortex, place RGS4 front and center in adrenal hormone secretion regulation, uniquely positioned to filter down excess CA and aldosterone production. Thus, strategies to potentiate adrenal RGS4 activity/levels may afford a significant therapeutic benefit in diseases characterized by elevated CA and/or aldosterone levels, such as chronic heart failure, hypertension, and other heart diseases [69, 70].

One such strategy is the use of the neurostimulant parachloroamphetamine (PCA), which specifically inhibits the Arg/N-end rule pathway, delaying the degradation of RGS4 [71]. RGS4 is a substrate of the so-called “Arg/N-end rule” pathway, in which proteins with either positively charged residues (the case of RGS4), such as Arg, Lys, and His, or bulky, hydrophobic residues, such as Phe, Trp, Leu, Tyr, and Ile, at their N-termini undergo proteasomal degradation and PCA has been reported to inhibit the Arg/N-end rule pathway slowing down RGS4 degradation in vitro and in vivo [71]. Indeed, intraperitoneal injection of PCA significantly increased endogenous RGS4 protein levels in the brain, particularly in the frontal cortex and hippocampus, in mice [71]. Thus, PCA or PCA derivatives may be utilized for therapeutic boosting of protein levels/activity specifically of RGS4 in the central nervous system or in the adrenal glands.

Considerable progress has been made over the past two decades in delineating the various signaling properties and biological actions of RGS proteins in almost every organ system, including in the central and autonomic nervous systems. As key regulators of GPCR signaling through G proteins, RGS proteins are enticing therapeutic targets based on their physiological and pathophysiological importance in the heart, kidneys, central nervous system, oncology, and other disease areas. On the other hand, there is a plethora of pathological situations where enhanced G protein signaling, accompanied by reduced RGS protein activity, is involved in the pathophysiology of a cardiovascular disease, so augmentation of RGS protein function would be desirable.

It is clear from the discussion above that particularly adrenal RGS4 could be targeted for sympatholytic therapy in the context of heart failure, hypertension, and other diseases accompanied and aggravated by elevated SNS activity. Although it is generally very hard to enhance the activity of an RGS protein pharmacologically, the inhibition of the N-end rule pathway with agents like para-chloroamphetamine provides a realistic, paves a viable way forward for the pharmaceutical and, importantly, selective potentiation of RGS4 activity. Regarding the central SNS, the picture is still quite foggy, unfortunately. More studies are urgently needed to address the roles of specific RGS proteins in regulation of SNA and NE release from the central nervous system (CNS). For the time being, RGS4, again, appears to be the RGS protein family member standing out for therapeutic targeting. Coupled with its established role in prevention of atrial fibrillation and of other cardiac arrhythmias, as well as its potential role in mitigating cardiac hypertrophy and heart failure (reviewed in Ref. [33]), it is easily conceivable that pharmacological targeting of RGS4 may be pursued for treatment of various cardiovascular conditions in the near future. On the other hand, given the multifaceted role of RGS4 in neuropsychiatric disorders (e.g., schizophrenia), potentiation of RGS4 in the CNS might turn out to be a “double edged sword”. Hence, the need for more studies on RGS4 and the other R4 family RGS proteins is more urgent than it has ever been.

RS and AL performed literature research and contributed to the writing of the manuscript and the drawing of the figures. AL supervised the project, led the writing of, and edited the manuscript. Both authors read and approved the final manuscript. Both authors have participated sufficiently in the work and agreed to be accountable for all aspects of the work.

Not applicable.

Not applicable.

A.L. is supported by a grant from the National Institutes of Health (NIH)/National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute (NHLBI) (R01 #HL155718-01).

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

Publisher’s Note: IMR Press stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.