1 Nanobiointeractions and Nanodiagnostics, Istituto Italiano di Tecnologia, Via Morego 30, 16163 Genova, Italy

Abstract

Chemokines are small proteins guiding cell migration with crucial role during immune responses. Their actions are mediated by 7-helix trans-membrane Gα protein-coupled receptors and ended by chemokine-receptor complex downregulation. Beyond its physiological role, ligand-induced receptor endocytosis can be exploited to vehiculate drugs and genetic materials within specific cells. Indeed, peptide-modified drugs and chemokine-decorated nanocarriers can target cell subpopulations significantly increasing cargo internalization. Carrier functionalization with small peptides or small-molecule-antagonists have been developed by different groups and proved their efficacy in vivo. One major limitation regards their restricted number of targeted receptors, although involved in diverse types of cancer and inflammatory diseases. Our group implemented nanoparticle decoration using whole chemokines, which in my opinion offer a versatile platform for precise drug delivery. The rationale relies on the broad and distinctive cellular expression of all chemokine receptors covering the different tissues, theoretically allowing chemokine-decorated particle delivery to any chosen cell subset. Although promising, our approach is still in its infancy and the experiments performed only in vitro so far. This manuscript briefly describes the established nanotechnologies for chemokine receptor-mediated delivery and, in greater details, our chemokine-decorated nanoparticles. Positive and negative aspects of the different approaches are also discussed, giving my opinion on why future nano-formulations could benefit from these chemo-attractant immune mediators.

Keywords

- chemokine receptor

- endocytosis

- nanoparticle

- drug delivery

- immune system

- cancer

- inflammation

Chemo-attractant cyto-kines (chemokines) are

approximately 10 kDa proteins characterized by two disulfide bonds formed among

four conserved cysteines [1]. The presence or absence, as well as the number of

aminoacidic residues between the first two cysteines proximal to the N-terminus

is used to classify and designate chemokines, as CC (adjacent cysteines) Ligand

(number) or CXC (cysteines separated by one aminoacid) Ligand (number) (e.g.,

CCL1, CCL2, … CCLn; CXCL1, CXCL2, … CXCLn) and their receptors, as

CC or CXC Receptor (number) (CCR1, CCR2, … CCRn; CXCR1, CXCR2, …

CXCRn). Two chemokine exceptions show one single C-C disulfide bridge and three

aminoacidic residues in between (CX3CL1), respectively. Fifty human

chemokines promiscuously bind with different affinity and specificity nineteen

7-helix trans-membrane G

Notwithstanding their broad role in cell biology, the physiological and pathological directions of leukocyte migration induced by chemokines and Chk-Rs represent their main tasks. From a functional point of view in immunology, chemokines are often described as “homing” [6] or pro-inflammatory [7]. The first ones are usually driving the physiological positioning of leukocytes in the immune tissues, whereas chemokines attracting effector cells towards sites of inflammation are considered pro-inflammatory. This useful description, however, is not precise and homing chemokines are frequently involved in inflammatory diseases or cancer. An emblematic example is the CCR7 and its binding chemokines CCL19 and CCL21 [8], which normally regulate the migration of antigen-presenting cells (APCs) and lymphocytes in the lymphoid tissues. For instance, CCR7 expression on M1 macrophages has a key pathological role in rheumatoid arthritis with CCL21 predominately responsible the disease manifestation in patients [9]. As well, CCR7 expression on dendritic cells mediate the origination and sustainment of different chronic inflammatory diseases, such as multiple sclerosis, psoriasis and several types of cancer [10]. On the contrary, pro-inflammatory chemokines are mainly dedicated to the attraction of phagocytes, granulocytes and activated lymphocytes to damaged or infected sites, working with high efficiency at very low concentrations in the nano-Molar range. CCL2, formerly named monocyte chemoattractant protein 1 (MCP-1) is among the most representative pro-inflammatory chemokines [11, 12]. Its role in most of the inflammatory pathologies is deeply investigated since decades, nevertheless, together with structurally similar chemokines, CCL2 provides crucial signals during the differentiation of T lymphocytes [13]. Moreover, a few chemokines such as CXCL12 (formerly know as stromal cell-derived factor 1, SDF-1) have so many different effects in all tissues that it is impossible to define them in a functional classification [14].

By a twist of evolutionary fate, an envelope protein of the Human

Immunodeficiency Virus (HIV), namely gp120, efficiently binds two Chk-Rs (CCR5

and CXCR4) following previous interaction of the virus with CD4 also expressed on

the host cell [15, 16]. Viral infection depends on these contacts, in facts, a

homozygous deletion at the residue 32 of the ccr5 gene can prevent the

HIV internalization in monocytes impeding the infection [17]. However, gp120 can

still independently bind CXCR4 triggering a biased signal transduction (e.g.,

Extracellular signal-regulated kinases (ERK) phosphorylation and apoptosis)

without receptor internalization [18]. On the other hand, different human viruses

encode human chemokine and ChR homologs in order to subvert the immune response

and increase their infectivity [19, 20, 21, 22, 23]. Worthy of mention, it is the discovery

of four other human “atypical receptors” strictly using

Together with their agonistic activity on GPCRs, some chemokines act as natural antagonists on non-cognate receptors preventing infiltration of leukocyte subsets in tissues or, alternatively, potentiating cell migration by synergistic effect with different chemokine-receptor systems [26].

Chemokine interaction with their corresponding receptors activate several intracellular signal pathways frequently inducing the endocytosis of the complex chemokine-chemokine receptor [27]. The internalization mechanism of Chk-Rs can be pharmacologically exploited to bring active molecules as well as NCs inside the cell for therapeutic goals. Although several cell membrane proteins can be mediators of endocytosis, the exclusive expression of Chk-Rs on different tissues and cell subtypes, or during the differentiation stages of the same cell line, could allow precise drug/gene delivery targeting.

Three different approaches to target Chk-Rs have been mainly explored by researchers in the fields of cancer, inflammation and general drug delivery. Firstly, the use chemokine receptor-binding peptides, eventually self-assembling in nano-structures, or chemokine-derived peptides used as drug carriers or to decorate nanoparticles (NPs). The second strategy exploits small-molecule chemokine receptor antagonists covering NP surfaces, demonstrating to be up-taken by receptor expressing cells. A third approach, used by our group, relies on the application of the full-length chemokines on the NP surface targeting, in principle, all the Chk-Rs of interest with their natural ligands.

At the end of the last century, the above-mentioned interaction of HIV with CCR5 and CXCR4 stimulated the search for specific antagonists to block the infection. An antimicrobial peptide isolated from the horseshoe crab (Limulus polyphemus) hemocytes, named [Tyr5,12,Lys7]-polyphemusin II peptide (T22) [28], demonstrated to be a potent HIV inhibitor by interfering with gp120 binding sites on CD4 [29] and CXCR4 [30]. This property of T22 has been exploited to selectively target CXCR4+ cells using T22-modified peptides [31]. Indeed, T22-green fluorescent protein (GFP) reporter was internalized by CXCR4 endocytosis and expressed within intracellular compartments. The same research group egregiously improved the targeting of CXCR4+ cancer cells using modified-T22 peptide-NCs over time, demonstrating the powerful exploitment of ChR-mediated drug delivery in different in vitro and in vivo disease models [32, 33, 34, 35, 36, 37, 38, 39, 40, 41, 42, 43]. Cancer cell lines as well as mouse models of acute myeloid leukemia (AML), diffuse large B-cell lymphoma (DLBCL), head and neck squamous cell carcinoma (HNSCC), endometrial cancer among others, were specifically targeted by self-assembly carriers of T22-modified proteins directed to CXCR4.

Protein-based NCs specific targeting CXCR4+ lymphoma cells in a mouse model was shown by Falgàs and colleagues [38]. Specific distribution in cancer cells, as evidenced by T22-GFP-peptide fluorescent emission, was achieved in subcutaneous lymphoma model after intravenous administration of the NC. T22-peptides’ selective targeting is underlined by their release in the bloodstream, given that the maximum pathological expression of the DLBCL is in the lymph nodes where enlarged B cells accumulate. Together with CXCR4+ cell delivery, these data also demonstrate the stability of T22-NCs in different biological milieus, such as blood and lymph.

CXCR4 is important in several kind of cancers and in particular in metastasis. Its overexpression in different cell types, as well as CXCL12 non-physiological release in some tissues, move cells away from their proper localization sites [44]. CXCR4 targeting results obtained with T22-delivery systems demonstrated their particular efficiency in inducing apoptosis of tumor cells by selective drug-induced cytotoxicity. In particular, in a work by Rioja-Blanco and colleagues [43] T22-diphtheria toxin cytotoxic domain monomers (T22-DITOX-H6) self-assembled into 38- and 90 nm NPs effectively killed cancer cells in the tumor microenvironment and distant metastasis without significant systemic toxicity in HNSCC mouse model. After repeated intravenous administrations, two principal metastatic sited in HNSCC cancer, namely lungs and liver, showed 70% reduction of the metastatic foci.

These experimental observations demonstrate the ability of blood circulating CXCR4-targeting NPs to kill tumor cells far from the injection site and impair their infiltration in the cervical lymph nodes, emphasizing persistence and distribution in vivo of these NPs.

As previously mentioned, some viruses encode chemokine and ChR homologs to disrupt the host immune reaction. Viral chemokine-derived peptides could also be an efficient tool to functionalize NPs for chemokine receptor targeting [45]. Triple negative breast cancer metastasis was impaired by empty liposomes engineered on their surface with DV1, a CXCR4 binding peptide based on the first 21 N-terminal residues of the human herpesvirus 8 (HHV 8 or Kaposi’s sarcoma-associated herpesvirus, KSHV)-encoded viral macrophage inflammatory protein II (vMIP-II) [46]. The DV1-liposomes blocked CXCL12-CXCR4 signaling, then cancer cell uncontrolled migration, without the adverse effects of common small-molecule CXCR4 antagonists. Considering the liposome-based carriers of modern vaccine-carriers, the opportunity to increase their selective targeting using chemokine-derived peptides could be an intriguing way for future vaccine formulation platforms. In addition, peptides able to potently bind CXCR4 have also been specifically designed and synthesized to be HIV inhibitors or conjugated onto NP surfaces for CXCR4 specific targeting [47]. 1DV3, 2DV3, and especially NP-surface decoration with 4DV3 peptide resulted in CXCR4 enhanced endocytosis of the carrier. Nevertheless, to ensure consistent therapeutic efficacy, peptide stability is crucial to enhance their shelf-life and resistance to degradation [48]. On the other hand, chemical modifications could alter their binding affinities and increase the risk of adverse reactions.

A different delivery strategy to aim at CXCR4+ cells was accomplished by NP-surface functionalization with small-molecule CXCR4-antagonists, especially 1,1′-[1,4-phenylenebis(methylene)] bis- 1,4,8,11-tetraazacyclotetradecane (AMD 3100) approved by FDA as HIV-infection inhibitor [49, 50, 51]. CXCR4-antagonist AMD3100 at high concentration shows some agonistic activities including CXCR4 internalization, although reduced compared to the natural ligand CXCL12. Presumably, crowding the nano-size surface area of NPs with AMD3100 molecules produce an increase of local CXCR4-binding molecule concentration allowing its partial-agonist property. The potential chemokine receptor dimerization/oligomerization could play a role when multiple weak agonists stimulate more than one receptor [52, 53], as it might be the case of several AMD3100 molecules closely bound on the NPs. Indeed, the release of liposomes delivering vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) small interference-RNAs (siRNAs) coated with AMD3100 was demonstrated as a promising therapeutic strategy to reduce liver cancer microenvironment-induced angiogenesis [54]. As well, AMD3100 functionalized lipid-coated poly(lactic-co-glycolic acid) (PLGA) NCs effectively delivered inside the cells sorafenib, an inhibitor for multiple kinases reducing angiogenesis and inducing cytotoxicity in vitro and in vivo models of vascular hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) [55].

NCs covered with small-molecule antagonists of CXCR4 are efficient delivery systems to target CXCR4+ cells, specifically in cancer. However, the NC surface functionalization with small molecules requires some chemical steps that may pose toxicological concerns if used for treatments not aimed at killing tumor cells. Side-products of the necessary chemical reactions to covalently bind chemokine receptor antagonists, such as AMD3100, could induce unexpected side effects which have been not tested so far to the best of my knowledge.

Despite its significance as HIV receptor, CCR5 plays key role in macrophage-driven innate responses, T Helper 1 (TH1)-lymphocyte infiltration of tissues, viral infections, cancers and autoimmune diseases, all events characterized by inflammation [56]. So, together with the antagonistic blockade of HIV, CCR5 binding has been also successfully used for diagnostic purposes to identify inflammation in atherosclerosis [57]. An antagonist peptide for CCR5, the D-Ala1-peptide T-amide (DAPTA) peptide (D-Ala-Ser-Thr-Thr-Thr- Asn-Tyr-Thr-NH2) labeled with radioactive 111In, was shown to be an optimal tracer for CCR5+ macrophages and T lymphocytes in atherosclerotic plaques of mouse models [58]. The identification of the inflammatory stages in mouse vascular injury models has been obtained with a similar strategy using DAPTA modified 64Cu-labeled 15-to-20 nm polymer particles relying on the affinity of the DAPTA for CCR5 [59]. 64Cu-DAPTA-NPs allowed PET imaging of CCR5 in the ApoE-/- mice and revealed the receptor upregulation in the progressive injured vessel wall. Detailed atherosclerotic plaque progression and regression has been described by PET imaging using the same CCR5-binding NPs in a following work [60].

The diagnostic relevance of these studies goes beyond the possibility to identify specific cell subsets defining the disease. Tracing chemokine receptor expression allows to follow the development and evolution of inflammation with clear opportunity to intervene with appropriate treatments at the right time. These results demonstrated the feasibility and the efficiency of chemokine receptor-mediated endocytosis as entry door for drugs, toxins and diagnostic cellular sensors. In particular, the chemokine/ChR network is becoming more and more a privileged therapeutic target for nanomedicine application in inflammation and metastatic cancers [61].

GDPRs endocytosis is mainly mediated by clathrin-dependent mechanisms [62]. Although the clathrin protein-triskelion usually assembles into polyhedral cages of roughly 200 nm in diameter, bigger vesicles are also usually observed in microscopy [63]. These observations, reinforce the perspective to use Chk-Rs as specific gate for bigger size particles below the micron-scale diameter considering the clathrin-coated endocytosis vesicles mainly used for ChR-mediated internalization [64, 65, 66]. Together with the bulk material, also size, shape and surface chemistry contribute to the prediction of toxicity, immune compatibility and biodistribution of NPs [67, 68, 69, 70]. Actually, these physicochemical features can be modified by the biomolecules adsorbed onto the NP creating a “biomolecular corona” [71, 72]. NP surface chemistry is extremely relevant to define the adsorption properties in the biological milieu providing the corona-forming proteins, lipids, sugars and small molecules. For targeting purposes, specific adsorption of chemokines could also be a strategy to decorate NPs [73, 74], however, the stability of the chemokine-adsorbed corona could not be consistent in diverse biological media with marked variation of composition and ionic strength. Presumably, biodegradable NPs bearing entire chemokines firmly linked on their surface can reduce toxicity, corona formation and avoid small-molecule antagonist side-effects, albeit allowing selective receptor targeting.

The development of particles exposing the entire chemokine onto their surfaces requires some chemical steps to evaluate the desired synthesis and NC performances [73]. FITC-labeled SiO2 particles have been prepared by our group as proof-of-principle NPs of well-characterized size and shape [75, 76]. CXCL5 (formerly known as ENA78 [77]) was chosen as prototype chemokine to be covalently bound on the NP surface. To have successful ligand-receptor binding, the chemokine linked onto the NP surface must expose its N-terminus to correctly engage its receptor (CXCR2) following the two-step model, previously described for CXCL12-CXCR4 interaction [78]. Then, as-synthesized negative SiO2 NP surface was firstly aminated in order to bind the COOH-terminus of CXCL5. CXCL5-NPs allowed to demonstrate the selective targeting of CXCR2+ cell lines and their increased internalization.

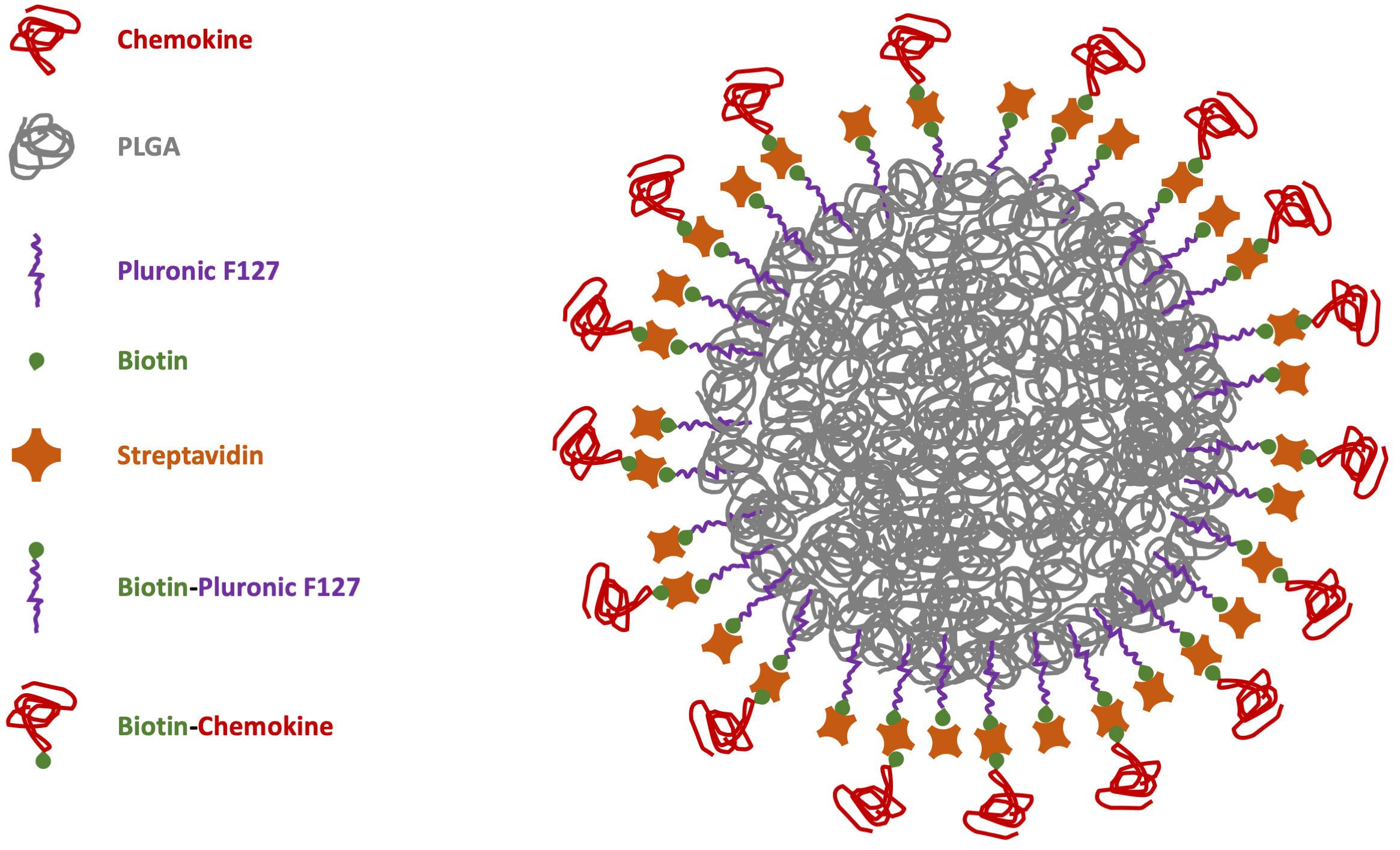

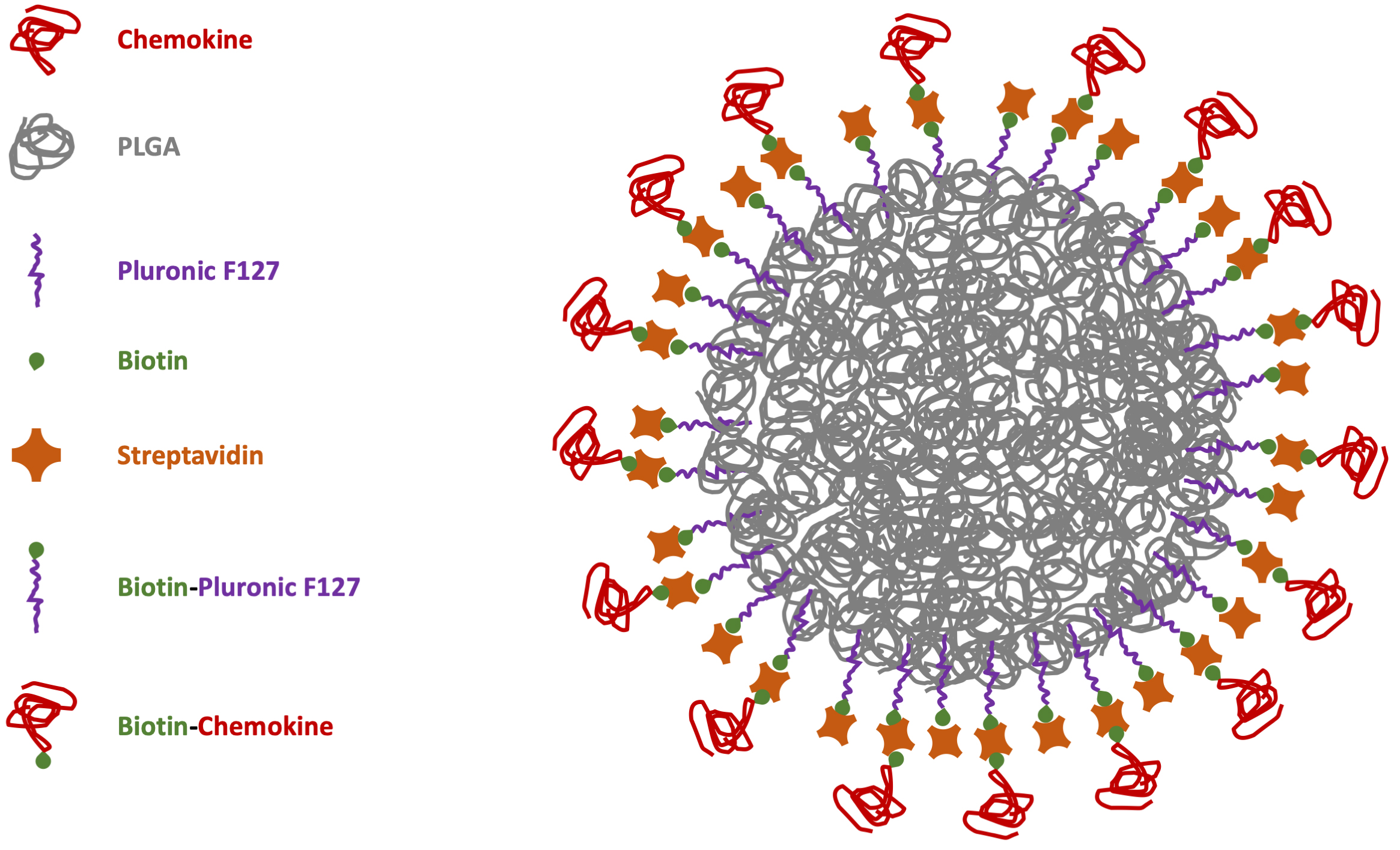

However, considering NC biocompatibility as one of the major issues for safe drug release, the best option would be to have biodegradable carriers to disappear after the delivery. Moreover, the possibility to avoid chemical reactions with potential noxious side-products can improve the synthesis of safe-by-design particles with easier translational potential for biomedical applications. This is particularly important in immunology for chemokine-functionalized NCs [79]. With these aims in mind, our group manufactured NPs through microfluidics-assisted nanoprecipitation using the FDA-approved polymer poly(lactic acid-co-glycolic acid) (PLGA) decorated with the CXCR4 receptor ligand CXCL12 [80]. To reduce the functionalization chemistry previously adopted for the chemokine covalent bond on the particle surface [75], PLGA-NPs were previously coated with a surfactant layer of biotinylated-Pluronic 127 to be further decorated using streptavidin (bearing 4 biotin binding sites per molecule) to link biotinylated-CXCL12 with strong-avidity (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1.

Fig. 1.

Scheme of chemokine-PLGA/Pluronic-NP. PLGA, poly (lactic-co-glycolic acid); NP, nanoparticle.

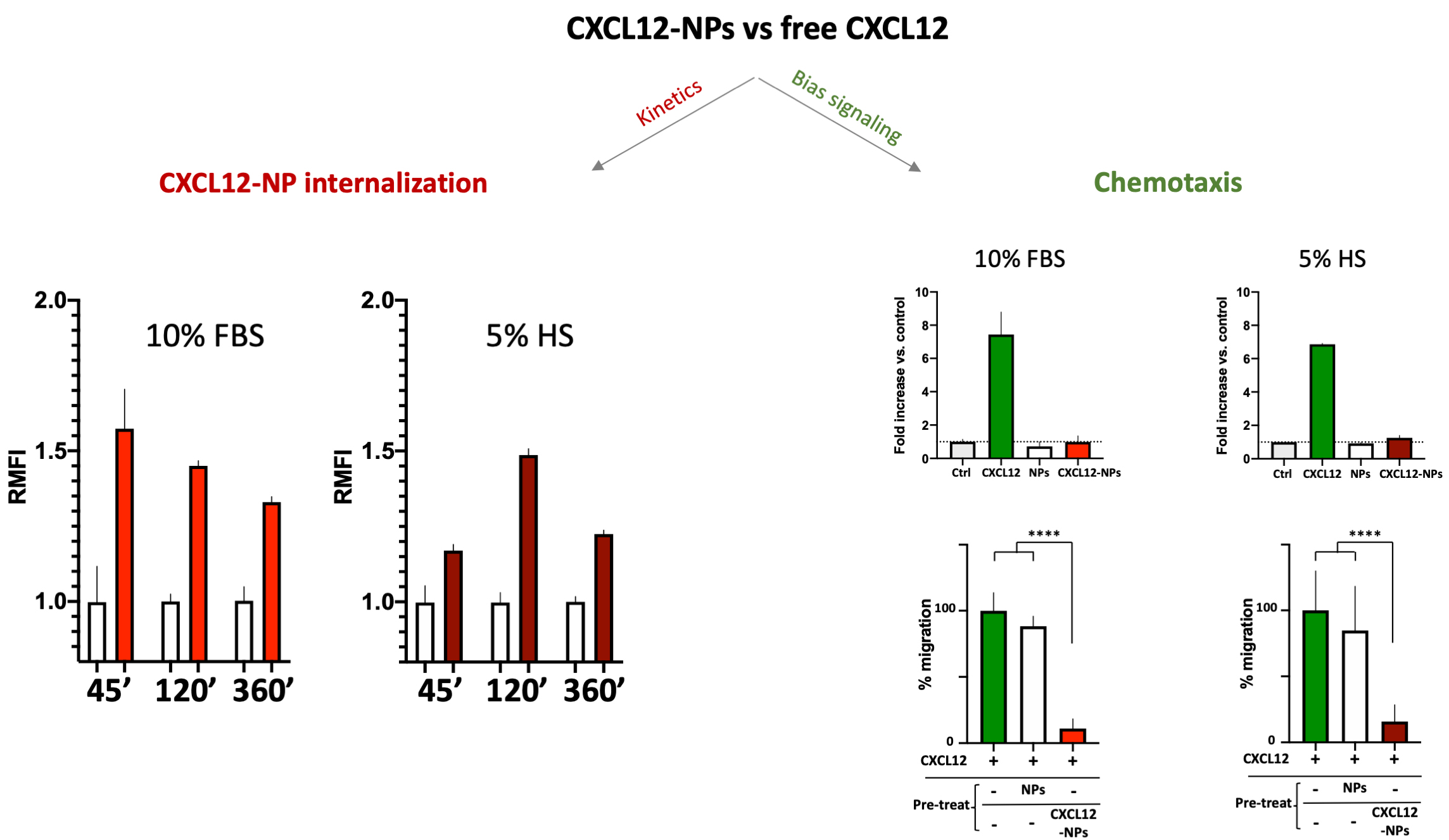

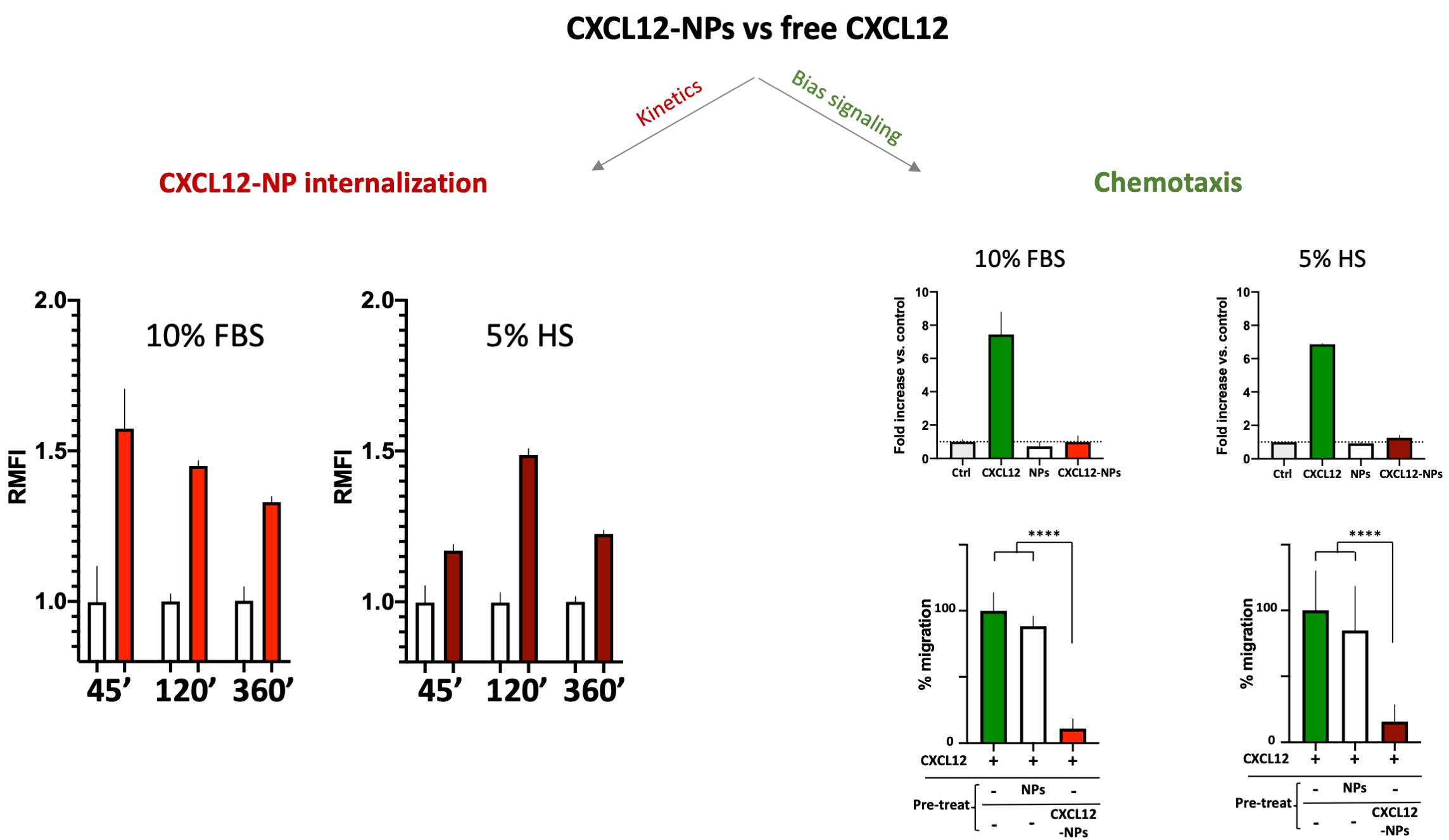

No cytotoxicity nor inflammatory cytokine release were shown by administration of PLGA-CXCL12 NPs to the monocyte/macrophage cell line, whereas increased internalization of CXCL12-NPs in CXCR4+ THP-1 cells was demonstrated, as expected. Two important data were obtained: different ChR internalization kinetics in different serum-supplemented media (biological milieu) and a bias signal transduction of chemokine-NPs in comparison with the free chemokine protein (Fig. 2, Ref. [80]).

Fig. 2.

Fig. 2.

CXCL12-NPs internalization (right graphs) in THP-1

cells cultured in 10% FBS/medium (red column) or 5% HS/medium (dark red column)

after 45 min, 2 h and 6 h in both media conditions. THP-1 cell migration (right

graphs, upper panel) towards free CXCL12 (green bars), non-functionalized NPs

(white bars) and CXCL12-NPs (red bars) in both media conditions; (right graphs,

lower panel) Cell migration towards CXCL12 (untreated cells in green bars), after

the treatment with non-functionalized NPs (white bars) and CXCL12-NPs (red bars). **** statistics significance by unpaired t test with

Welch’s correction, **** p

The above-mentioned effects of the biomolecular corona onto released NPs are evident in the different internalization kinetics of CXCL12-NPs in fetal bovine serum (FBS)-supplemented or Human Serum (HS)-supplemented media. As reported in Fig. 2, the kinetics of CXCR4-mediated cell uptake of CXCL12-NPs in FBS-medium is different from HS-medium. Although the maximal fluorescence intensity was similar by flow cytometry, the highest level of CXCL12-NPs internalization in HS supplemented medium was reached after 2 hours. On the contrary, faster internalization (max at 45 min administration) was seen in FBS-medium. This is partly due to the different membrane expression of CXCR4 in the two media, which is higher in FBS-medium cultured THP-1 [80]. Beyond the observed effects of serum on cell membrane protein expression, a direct effect of the biological molecules present in the media adsorbed onto the particles could not be excluded. The second intriguing observation regards the distinctive effect of chemokines is the induction of cell migration, a phenomenon called chemotaxis, which involves a huge number of intracellular mediators. Albeit, non-functionalized NPs nor CXCL12-NPs induce chemotaxis by themselves (Fig. 2, right upper panel), pre-administration of CXCL12-NPs reduces CXCR4+ cell migration towards CXCL12 gradient by a similar extent in FBS- or HS-supplemented media. On the contrary, the treatment with “naked” NPs does not impair cell migration (Fig. 2, right lower panel). Our interpretation is that chemokine-decorated NPs are able to bind and activate the signaling to internalize the receptor (as well as the free chemokine), but they fail to induce chemotaxis. In other words, CXCL12-NP-induced signal transduction after receptor binding does not proceed further towards the cytoskeleton rearrangement. As presumed, non-functionalized NPs do not bind CXCR4, as shown by their inability to compete with free CXCL12 in chemotaxis.

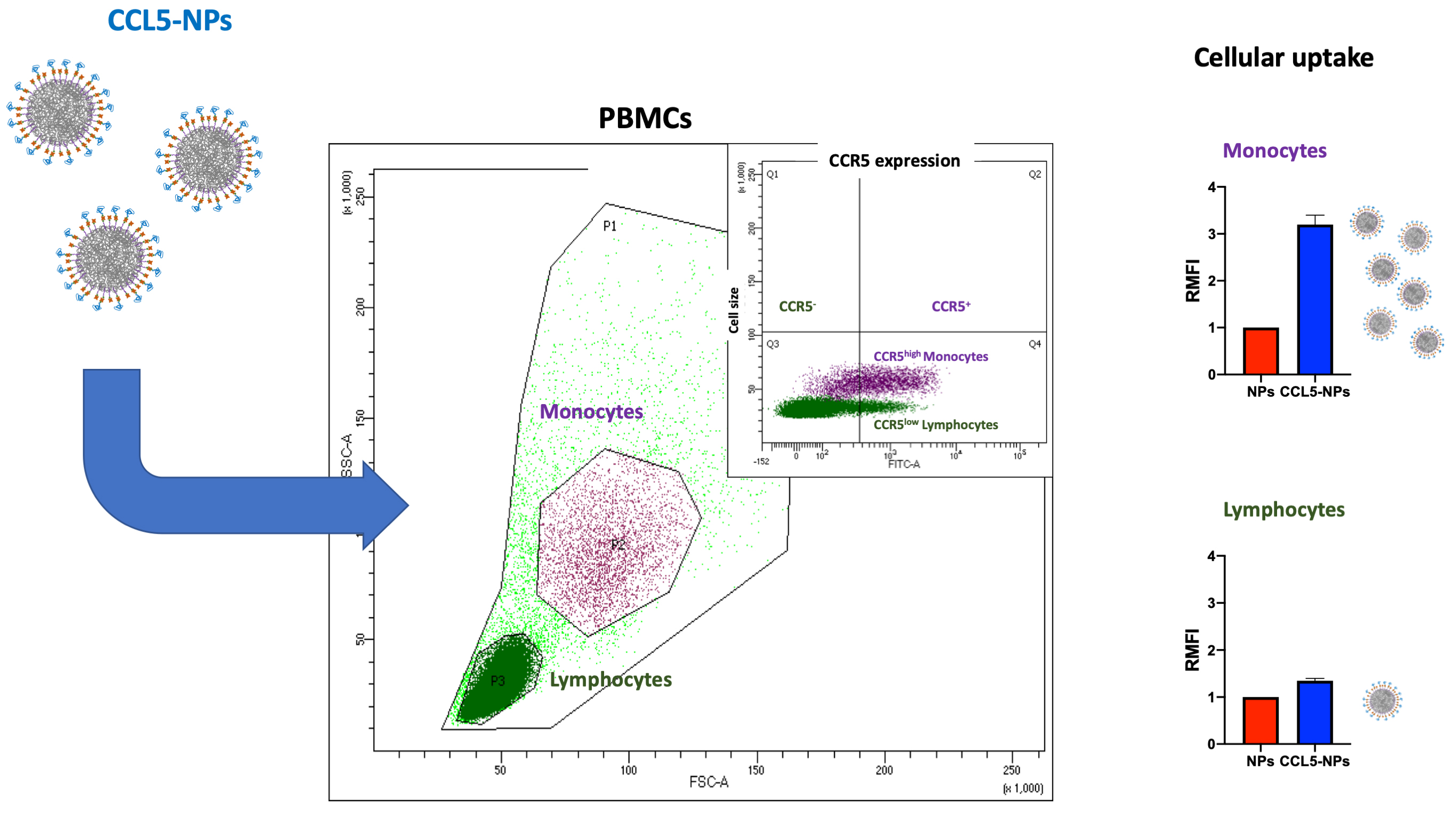

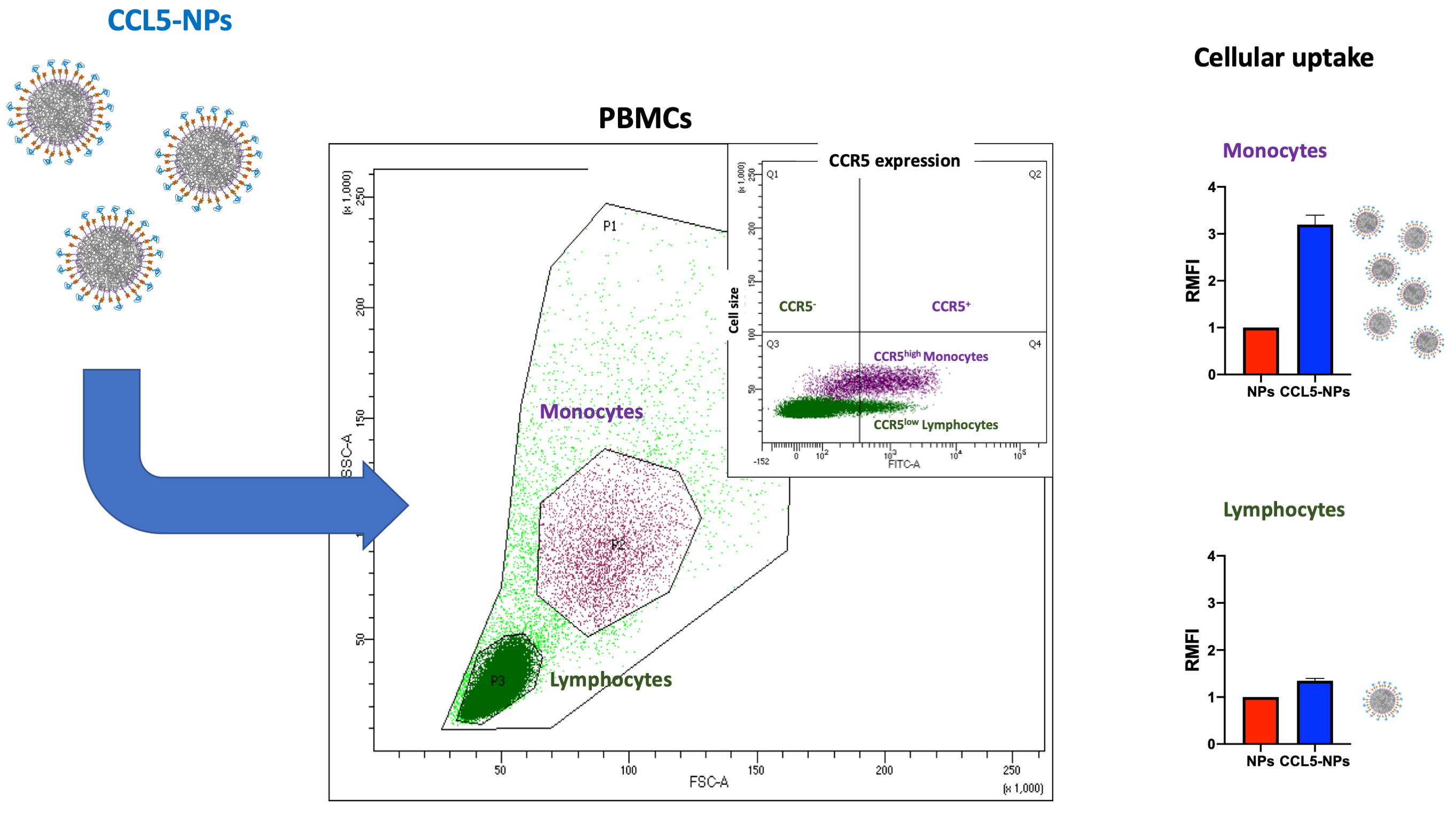

Receptor internalization by chemokine-NPs has also been confirmed with the same type of NPs functionalized with CCL5, showing only receptor binding at 4 °C followed by CCR5 (CCL5 receptor) internalization at 37 °C [81]. In the same work, it has been demonstrated the targeting of specific cell subsets in primary human Peripheral Blood Mononuclear Cells (PBMCs). Namely, CCL5-NPs specifically enter CCR5+ monocytes without binding CCR5– lymphocytes (Fig. 3, Ref. [81]). This result is very important for the designing of NCs with reduced side-effects in off-targeting tissues.

Fig. 3.

Fig. 3.

Scheme of CCL5-NPs internalization in PBMCs. CCL5, (C-C motif) ligand 5; CCR5, C-C chemokine receptor type 5; PBMCs, Peripheral Blood Mononuclear Cells; RMFI, Relative Median Fluorescence Intensity; SSC, Side Scattering; FSC, Forward Scattering; FITC, Fluoresceine Isothiocyanate.

Chk-Rs are gaining more and more attention as selective targets for several pathologies. Their endocytosis upon chemokine binding can be a selective entry door for the delivery of drugs or genetic materials. Among the several ways to target and engage the receptor, the use of short peptides, small molecule antagonists and the whole chemokine to functionalize NC surfaces have demonstrated solid and reproducible results. In search for the ideal NC to exploit ChR-mediated therapeutic release, CXCR4-mediated delivery of nanomaterials by exploiting surface-bound short peptides naturally produced by microorganisms is certainly at an advanced pharmacological stage demonstrating successful results to block metastasis and angiogenesis using in vivo cancer models. Certainly, this strategy should be pursued to fight several types of cancers and viral infections. Small molecule antagonists of CXCR4 and CCR5 and, maybe, a few other receptor antagonists could also be helpful to engage these receptors in the diseases related to their overexpression. Nevertheless, these strategies are limited to these receptors, so more selective approaches to fostering therapeutic breakthroughs in immunology could be helpful.

Immune diseases including infections or genetic mutations affect innate and the adaptive responses through several and diverse chemokines. The huge complexity of this scenario imposes extreme specificity for the delivery in different tissues, which I think it can be assured by the binding of the chemokine (natural ligand) to its cognate receptor. Inflammation in the brain, heart, mucosa and many other tissues necessitate extremely precise localization of anti-inflammatory therapeutics to result in efficient treatments. Although a preliminary stage, NC functionalization with whole-protein chemokines represent a promising approach exploiting the natural receptor ligands and their physiological spreading in biological fluids and tissues. Furthermore, the recent advances in biotechnology provide a plethora of bio-tools that could act in the right place at the right time if specifically delivered by chemokine-decorated NCs. We might think that Crisp/Cas9-mediated gene editing, synthesized messenger RNAs (miRNAs) or Piwi interacting RNAs (piRNAs), as well as other innovative biomolecular tool could be delivered at a precise stage of a certain immune disease. Their delivery would take advantage of the expression of a particular Chk-Rs as the perfect entry door at that particular stage of the disease. The same receptor would not be expressed in previous or later pathological phases of the same disease, limiting unspecific immune reactions. Possible application of chemokine-mediated delivery to vaccinology is an intriguing scenario. The recent Covid-19 pandemics has shown the importance of lipidic NC-mediated delivery of mRNA-based vaccines. Thinking to improve their selective targeting to leukocytes, maybe restricted to lymphoid tissues in the mucosa, it is an amazing conjecture with potential implication for global health.

Anyway, some trouble-shooting will be necessary to overcome intracellular limitations. For instance, future applicative studies should concentrate on reliable method to cross the different barriers protecting the tissues, which sometimes represent the hardest obstacle in drug delivery.

ChR-mediated endocytosis relies on the endosome-lysosome pathway enforcing strategies for lysosomal escape of the delivered cargo. This specific point has also not been fully investigated. Whereas small-molecule drugs are supposed to escape more easily form intracellular vesicles, entire NPs are limited by their size and the bulk materials. In this regard, biodegradable particles like self-assembly peptides or hydrolyzable polymer-made NPs should be advantageous.

Although the chemokine decoration of the NCs could be beneficial to reduce the biomolecular corona in vivo, if compared to as-synthesized particle chemical surfaces, the blood circulation time of the diverse carriers should still be proved in different in vivo disease models, considering the distinctive plasma conditions induced by each disease states. Last but not least, many chemokines act as agonists for their cognate receptors and as antagonists for others requiring the precise selection of the proper protein to aim at chosen cell target.

Most of these obstacles could hopefully be overcome by the application of Artificial Intelligence to this field of research. For example, to produce “smart” chemokine-like peptides binding Chk-Rs with higher affinity than natural chemokines and able to trigger specific intracellular pathways of interest. If intensely trained neural networks will be able to unravel the tangle of thousands of chemical bonds among hundreds of biomolecules forming the corona in the different types of biological fluids, safe-by-design particles could show specific chemical surfaces to avoid random protein adhesion.

In conclusion, future precise medicine will need most of the available protocols, as well as the application of innovative technologies to improve the delivery of therapeutics by NCs through chemokine receptor endocytosis.

The single author was responsible for the conception of ideas presented, writing, and the entire preparation of this manuscript.

Not applicable.

I gratefully acknowledge the assistance of all my collaborators quoted in references, who allowed me organize this review with the reported results.

This research received no external funding.

The author declares no conflict of interest.

References

Publisher’s Note: IMR Press stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.