1 Department of Biochemistry and Molecular Biology, Faculty of Medicine, University of Oviedo, 33006 Oviedo, Spain

2 Department of Functional Biology, Faculty of Medicine, University of Oviedo, 33006 Oviedo, Spain

3 University Institute of Oncology of Asturias (IUOPA), University of Oviedo, 33006 Oviedo, Spain

4 Health Research Institute of Asturias (ISPA), 33011 Oviedo, Spain

5 Department of Morphology and Cell Biology, Faculty of Medicine, University of Oviedo, 33006 Oviedo, Spain

Abstract

Autophagy is a conserved catabolic process that promotes cellular homeostasis and health. Although exercise is a well-established inducer of this pathway, little is known about the effects of different types of training protocols on the autophagy levels of tissues that are tightly linked to age-related metabolic syndromes (like brown adipose tissue) but are not easily accessible in humans.

Here, we take advantage of animal models to assess the effects of short- and long-term resistance and endurance training in both white and brown adipose tissue, reporting distinct alterations on autophagy proteins microtubule-associated proteins 1A/1B light chain 3B (MAP1LC3B, or LC3B) and sequestosome-1 (SQSTM1/p62). Additionally, we also analyzed the repercussions of these interventions in fat tissues of mice lacking autophagy-related protein 4 homolog B (ATG4B), further assessing the impact of exercise in these dynamic, regulatory organs when autophagy is limited.

In wild-type mice, both short-term endurance and resistance training protocols increased the levels of autophagy markers in white adipose tissue before this similarity diverges during long training, while autophagy regulation appears to be far more complex in brown adipose tissue. Meanwhile, in ATG4B-deficient mice, only resistance training could slightly increase the presence of lipidated LC3B, while p62 levels increased in white adipose tissue after short-term training but decreased in brown adipose tissue after long-term training.

Altogether, our study suggests an intricated regulation of exercise-induced autophagy in adipose tissues that is dependent on the training protocol and the autophagy competence of the organism.

Keywords

- exercise

- endurance training

- resistance training

- autophagy

- ATG4B

- adipose tissue

- LC3B

- p62

The local and systemic benefits of exercise training have been widely described in the literature [1], not only for sports performance but also to prevent and treat several chronic pathologies, including metabolic disorders [2]. Thus, exercise has emerged as a powerful and safe lifestyle intervention to promote health throughout the lifespan, including the elderly [3]. Nine major hallmarks have been defined to characterize aging [4], with exercise being able to counteract several of them [5, 6]. The loss of autophagy, a major proteolytic system in our cells, is one of these hallmarks. Autophagy is a stress-induced response that mediates the transportation of cytoplasmatic components to the lysosome for its ultimate degradation. There are three types of autophagy: macroautophagy (where the cargo is sequestered and delivered by double-membrane vesicles termed “autophagosomes”), microautophagy (when invaginations of the lysosomal membrane directly sequester cytosolic portions), and chaperone-mediated autophagy (CMA, for targeted proteins displaying a specific motif). This process, along with its complex molecular machinery, is essential to maintain cellular homeostasis, and its decline has been described during aging in different animal models [7, 8], while its activation has been linked to increased lifespan and healthspan in flies, worms, and mammals [9, 10, 11]. Interestingly, endurance exercise is a well-known physiological inducer of autophagy [12], and we have previously described that this mechanism is particularly relevant for resistance gain and exercise-induced adaptations in the brain [13]. However, the effects of training on the autophagic response of white and brown adipose tissues (WAT and BAT) remain unclear. This is relevant, as autophagy and fat tissues play an important role in maintaining the organism’s metabolic balance and preventing metabolic, cardiovascular, and cognitive diseases [14, 15, 16, 17]. In this regard, WAT and BAT play distinct (yet interconnected) roles in age-related metabolic syndromes [18]. While WAT primarily functions as energy storage, it also secretes hormones (adipokines) that influence appetite, insulin sensitivity, and inflammation [19]. However, its expansion, often associated with obesity, can lead to chronic inflammation, insulin resistance, and type 2 diabetes [20]. Conversely, BAT is mainly specialized for thermogenesis (burning energy to produce heat), and it is linked to improved glucose metabolism and insulin sensitivity [21]. With aging, and contrarily to WAT, BAT mass tends to decline, contributing to metabolic dysfunction. This reduced BAT activity has been associated with an increased risk of obesity, type 2 diabetes, and cardiovascular disease [22]. Interestingly, autophagy is emerging as a crucial regulator of adipose tissue function, though its function is context-dependent [14]. Furthermore, exercise can also regulate the activity of adipose tissues [23]. For example, it has been described that endurance exercise induces WAT “browning” [24], an autophagy-dependent process that has been linked to a diminished risk of metabolic diseases [25, 26]. Nevertheless, very little is known about the effect of resistance exercise on autophagy in adipose tissues.

Here, we describe how different exercise models (resistance and endurance, short- and long-term) modify the levels of autophagy markers in WAT and BAT. Specifically, we have analyzed the status of microtubule-associated proteins 1A/1B light chain 3B (MAP1LC3B, or LC3B, an indicator of autophagosome abundance, as it is attached to the membranes of these autophagic structures), the LC3B-II/LC3B-I ratio (that also reports autophagosome accumulation when it is increased, as the lipidated form, LC3B-II, rises at the expense of the cytosolic form, LC3B-I), and the amounts of sequestosome-1 (SQSTM1/p62, an autophagy adapter that is degraded when the route is activated). The levels of these autophagy proteins are widely used reporters that can be easily assessed by western blot analyses, providing a valuable estimation of the formation of autophagosomes and the degradation of their internal substrates [27]. Moreover, we use autophagy-deficient mice to describe how the impact of training is affected when this process is hampered, as is observed during aging.

8-week-old male mice with mixed background C57BL6/129Sv, deficient in

Atg4b [28] (KO; n = 36) and their corresponding wild-type (WT) controls

(n = 36), were used. Eight mice were housed per cage with food and water

ad libitum. Mice were maintained on a 12 h light/dark cycle (onset at

8:00 AM) and under controlled temperature (22

A commercial treadmill for rats (LE8700, Panlab, Barcelona, Spain) and an

own-manufactured vertical ladder were used for training. The ladder was built

with 30 steel wire steps of 1.5 mm diameter, separated by 15 mm. A 20

Full-detailed training protocols are described elsewhere [13]. Briefly, training was divided into two different phases.

Acclimation period (2 weeks): To favour mice acclimatization, all animals stayed 20 min in each working station (treadmill, ladder, and clean cage), 5 days/week in groups of four. In the first week, mice were placed on the treadmill without movement and in the resting area at the top of the ladder. The following week, animals walked on the moving treadmill belt (10 cm/s, for 20 min) and they were shown how to climb the ladder, from the 5th top step to the resting area, with 2 min of rest intervals, for 20 min.

Training period (2 weeks or 14 weeks): The mice were trained in groups of four, with no rejection to training noted. No aversive stimuli were used. Progressive and humanized training protocols were performed [29], and control mice explored freely in a new cage while the exercise groups were training in the same room.

Mice were sacrificed 48 h after the last exercise bout by CO2 inhalation. Perigonadal WAT and interscapular BAT were extracted and preserved at –80 °C. Then, they were homogenized in an extraction buffer consisting of 20 mM HEPES (H4034, Sigma-Aldrich, Burlington, MA, USA), pH 7.4, 100 mM NaCl (S9888, Sigma-Aldrich, Burlington, MA, USA), 50 mM NaF (201154, Sigma-Aldrich, Burlington, MA, USA), 5 mM EDTA (E9884, Sigma-Aldrich, Burlington, MA, USA), 1% Triton X-100 (13444259, Thermo Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA), 1 mM sodium orthovanadate (S6508, Sigma-Aldrich, Burlington, MA, USA), 1 mM pyrophosphate (221368, Sigma-Aldrich, Burlington, MA, USA), and cOmplete™ protease inhibitor cocktail (04693116001, Hoffmann-La Roche, Basel, Switzerland). Then, samples were centrifuged at 12,000 g, at 4 °C, for 10 min, and the supernatant was collected and preserved at –80 °C until further use. Protein quantification was determined by the bicinchoninic acid technique (Pierce BCA Protein Assay kit; 23227, Thermo Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA). Total protein (20 µg) was electrophoresed on 15% SDS-polyacrylamide gel and transferred to PVDF (Millipore, Burlington, MA, USA) membranes, which were then blocked in TBS-T (Tris-buffered saline with 5% BSA (BP9706, Thermo Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA) and 1% Tween-20 (P9416, Sigma-Aldrich, Burlington, MA, USA)). Next, membranes were incubated with rabbit anti-LC3B (NB600-1384, Novus Biologicals, Littleton, CO, USA) and mouse anti-SQSTM1/p62 clone 2C11 (H00008878-M01, Abnova, Taipei, Taiwan) antibodies diluted in TBS-T. Then, membranes were incubated with corresponding secondary antibodies (Santa Cruz Biotechnologies, Dallas, TX, USA), conjugated with horseradish peroxidase, for 1 h at RT. Detection was developed with Luminata™ Forte (Millipore, Burlington, MA, USA) and images were acquired using an Odyssey® Fc Imaging System 2000 (LI-COR, Lincoln, NE, USA). Anti-actin conjugated with horseradish peroxidase (sc-47778, Santa Cruz Biotechnologies, Dallas, TX, USA) was used as a loading control.

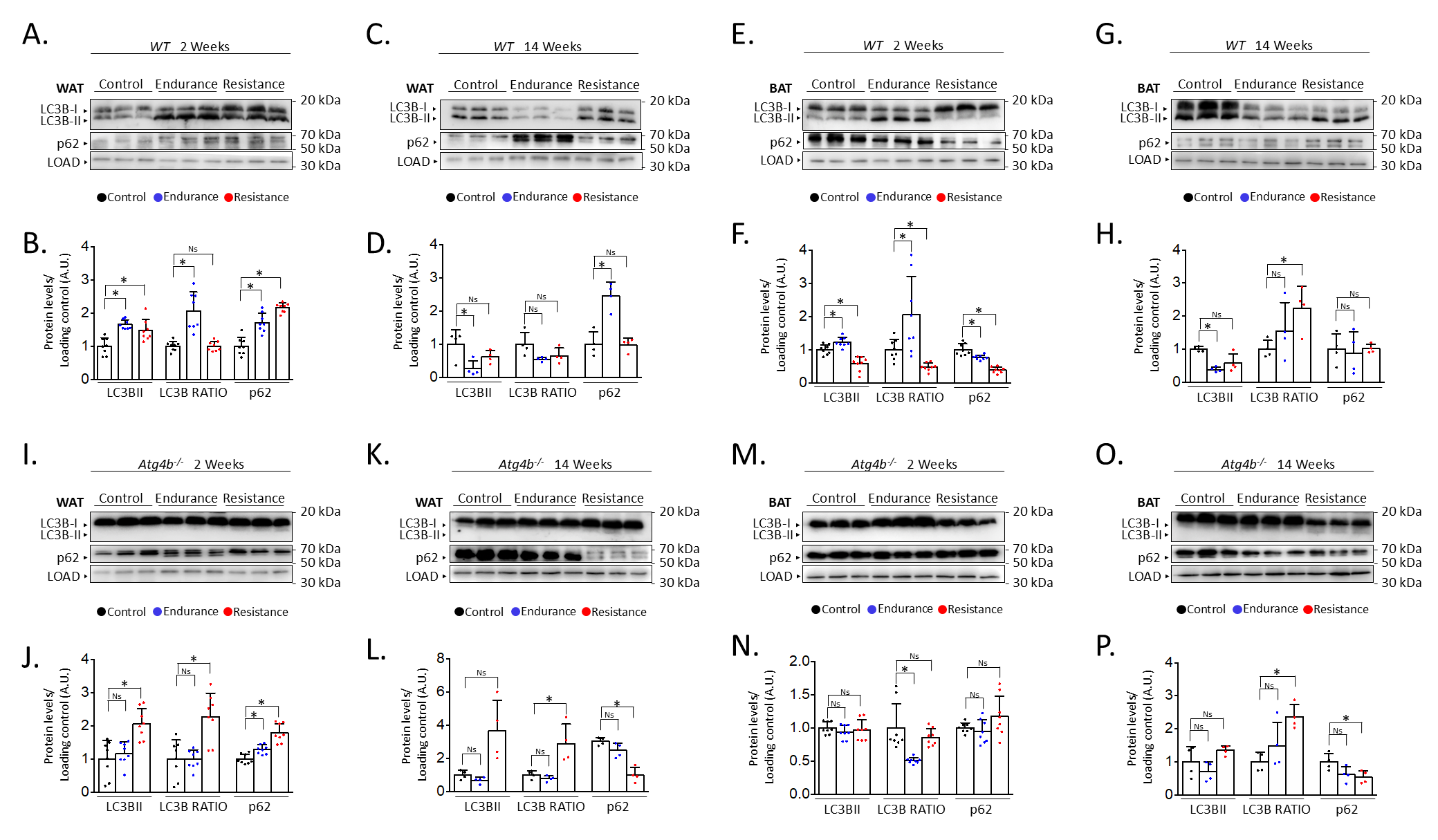

Data are presented as means

After describing the different effects of endurance and resistance training on the levels of autophagy in the brain of rested and exercised mice [13], we decided to address the status of autophagy markers in the adipose tissue after 2 weeks or 14 weeks of the aforementioned training protocols. For this purpose, we performed immunoblotting analyses to detect autophagy markers LC3B (as the accumulation of its lipidated form, LC3B-II, is associated with increased autophagy) and SQSTM1/p62 (an autophagy substrate) [27] in both gonadal white adipose tissue (WAT) and interscapular brown adipose tissue (BAT). Interestingly, both endurance and resistance training protocols increased the levels of these autophagy markers in WAT after just 2 weeks of exercise (Fig. 1A,B). In the case of endurance training, it also resulted in an increased ratio of the lipidated form of LC3B (LC3B-II) over the unconjugated one (LC3B-I), which could hint at a possible accumulation of autophagic vesicles within these cells. On the contrary, exercising the mice for 14 weeks distinctly affected the expression of these proteins (Fig. 1C,D). For instance, endurance training significantly reduced the levels of LC3B-II while increasing the presence of p62 in WAT. Meanwhile, a slight decrease in the quantity of LC3B-II after resistance training was not accompanied by an increase of p62, as its levels remained comparable to those from rested mice. Thus, while short exercise protocols seem to induce the increase of autophagy markers in WAT, the extension of these interventions results in the differential regulation of their expression depending on the type of exercise. However, these changes are not only exercise- or extension-dependent but also tissue-dependent. For instance, 2 weeks of endurance training also caused LC3B-II to increase in BAT, accompanied by a p62 decrease, in opposition to what we observed in WAT (Fig. 1E,F). As for resistance training, this short exercise protocol resulted in a significant decrease of both p62 and LC3B-II when these samples were compared to those from control animals. Intriguingly, the 14-week-long exercise protocols had comparable effects on the levels of autophagy markers in BAT (Fig. 1G,H), as both endurance and resistance training increased LC3B-II/LC3B-I ratio while the amounts of p62 remained unaltered. Taken together, these results confirm that different training protocols can distinctly alter the status of autophagy markers in adipose tissues.

Fig. 1.

Fig. 1.

Alterations on autophagy markers in white and brown adipose

tissues after endurance or resistance training. Western blot analyses of the

autophagy markers microtubule-associated proteins 1A/1B light chain 3B (LC3B) and

sequestosome-1 (p62) in wild-type WAT show that both proteins are increased after

short training, while only endurance training results in changes after 14 weeks

(showing p62 increase and LC3B decrease) (A–D). In wild-type BAT, p62 decreases

after short training but remains unaltered after 14 weeks, while LC3B-II

decreases after all training programmes except short-term endurance, which

increases it (E–H). In WAT from Atg4b-/-mice, LC3B-II (and the

LC3B-II/LC3B-I ratio) is only increased after resistance training, while p62

increases after short training (I–L). Finally, levels of LC3B-II do not change

in Atg4b-deficient BAT, with p62 decreasing after 14 weeks of training

(M–P). N = 8 mice per genotype in 2-week-long training protocols; N = 4 mice per

genotype in 14-week-long training protocols. Ns, no significant difference;

*p

Given the observed results in adipose tissue from trained WT mice, we were prompted to analyse the effect of training in the context of autophagy deficiency. Thus, we trained mice lacking cysteine protease ATG4B, a murine model that shows attenuated autophagic response [28] and increased susceptibility to different experimentally-induced pathologies [30, 31, 32, 33]. Even more, we have previously described that these animals show worse adaptive responses to exercise, also presenting alterations in the levels of autophagy markers in different brain areas [13]. As shown in Fig. 1I,J, both endurance and resistance training protocols induced a slight increase of p62 in the WAT of exercised animals after two weeks in comparison to their rested Atg4b-deficient littermates. However, only resistance exercise was able to increase the presence of LC3B-II in this tissue. ATG4B deficiency significantly disrupts LC3B-II formation in these animals [28], which suggests that the detection of the lipidated form of LC3B after resistance training may be due to a compensatory upregulation on the activity of the other ATG4 proteases (ATG4A, ATG4C and/or ATG4D). When the protocol is extended up to 14 weeks, mice exercised under the endurance training protocol showed protein levels that were comparable to those from control Atg4b-/- animals (Fig. 1K,L). However, WAT from mice that trained resistance still showed increased LC3B-II levels and increased LC3B-II/LC3B-I ratio, even though p62 was now significantly decreased. Curiously, 2-week training protocols had little to no effect on the levels of autophagy markers in BAT from Atg4b-deficient mice (Fig. 1M,N), as all three groups exhibited similar levels of LC3B-II and p62. In these animals, the LC3B-II/LC3B-I ratio was decreased after endurance training, though this was due to the increase of LC3B-I in this group. As for the 14-week-long training intervention, mice that trained resistance displayed once again a statistically significant decrease on p62 with an increase in the LC3B-II/LC3-I ratio, similar to what we observed in WAT (Fig. 1O,P). Protein levels were not significantly different after endurance training, though we could detect a partial trend towards a p62 decrease. Collectively, these data confirm that autophagy markers are also altered upon exercise in the adipose tissues of mice lacking ATG4B protease.

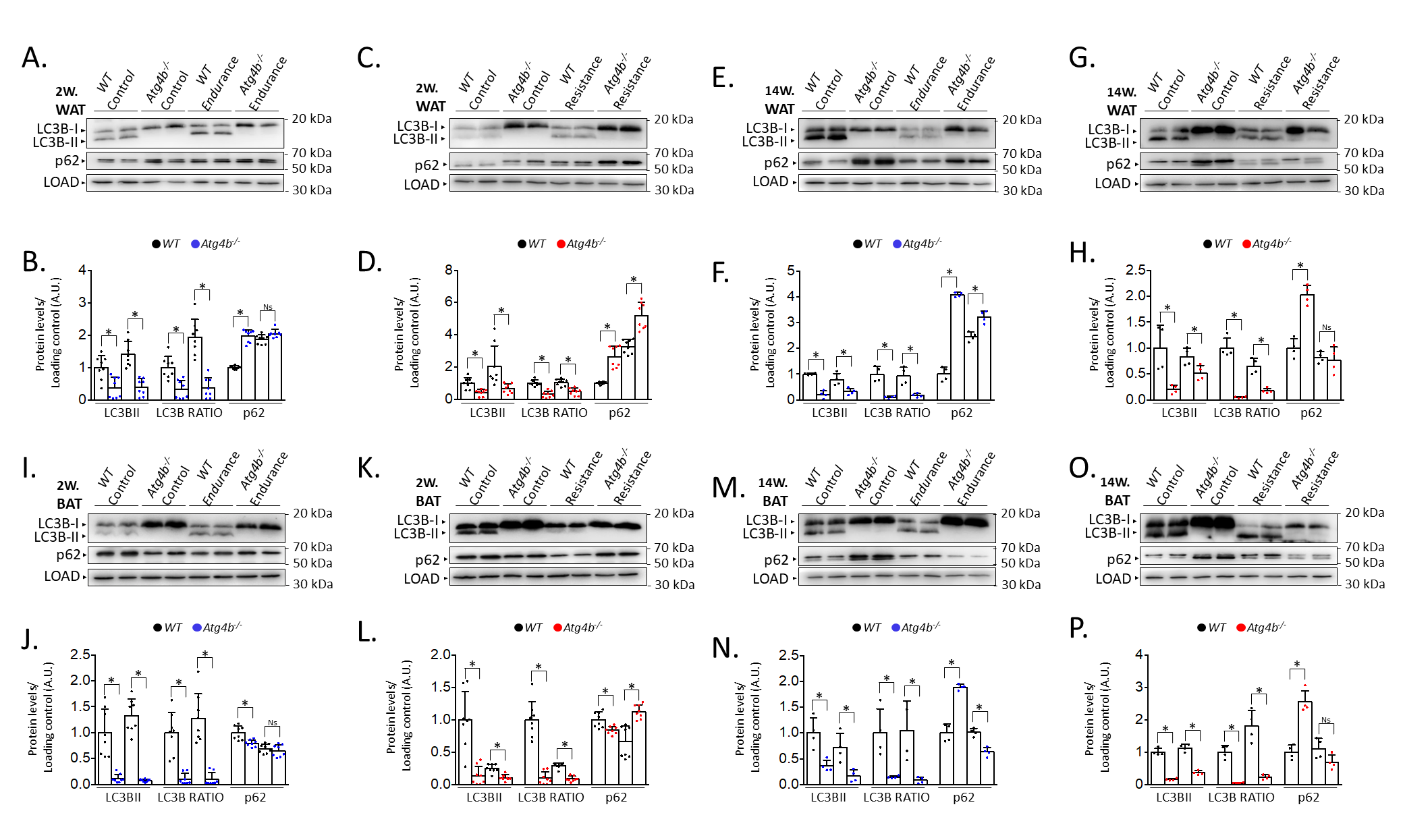

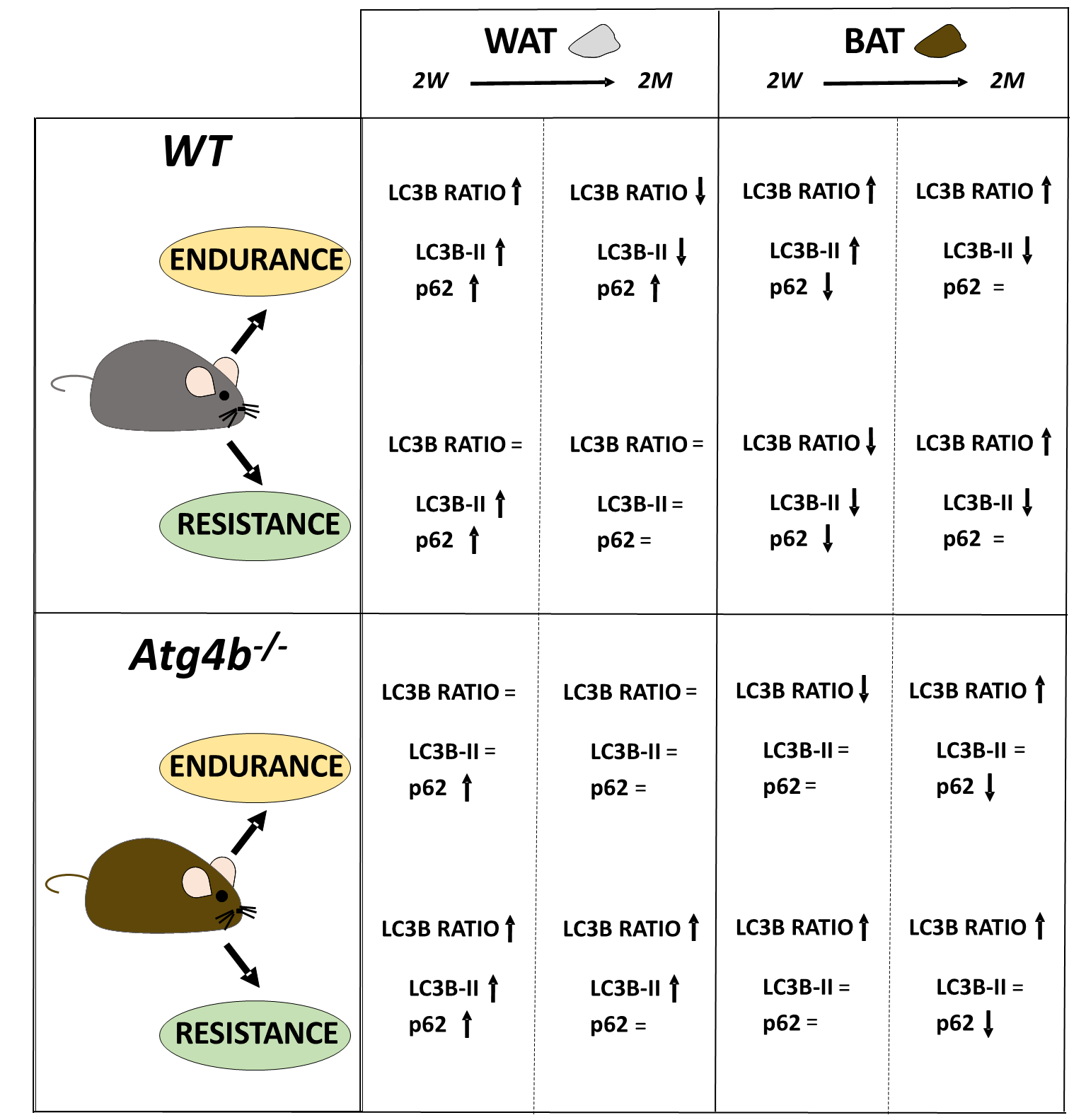

Last, we decided to compare protein levels of LC3B and p62 between WT and Atg4b-/- animals within the same group. This approach allowed us to assess possible alterations in these autophagy markers in basal conditions due to the absence of ATG4B and measure how the effect of training is affected when autophagy is hampered. In WAT, rested knock-out mice showed decreased LC3B-II levels and LC3B-II/LC3B-I ratio, as well as an increase of p62 (Fig. 2A–H) when compared to WT animals that were not trained either. These results further confirm our previous observations on the status of autophagy markers in the white adipose tissue of Atg4b-deficient mice [33]. All training protocols (endurance and resistance, short and long) failed to rescue LC3B or LC3B-II/LC3B-I ratio to the levels displayed by the corresponding WT groups in this tissue, highlighting the crucial role of ATG4B in LC3-II formation. As for p62, Atg4b-/-mice still showed increased levels of this marker after the 14-week-long endurance training and the 2-week resistance training. When we compared protein levels in BAT, we found out that Atg4b-deficient mice also showed a dramatic decrease of LC3B-II and in LC3B-II/LC3B-I ratio. However, contrary to what we observed in WAT, p62 levels were at first decreased in younger knock-out mice but already increased after 14 weeks (Fig. 2I–P), suggesting a probable accumulation in this tissue with aging, and matching the phenotype we describe in WAT. Once again, none of the training protocols succeeded in rescuing LC3B-II levels or LC3B-II/LC3B-I ratio to what is displayed by those observed in trained WT mice. Interestingly, while short training periods had either a null (endurance) or increasing effect (resistance) on the levels of p62, prolonged training resulted in a significant decrease of this protein in brown adipose tissue of knock-out mice. Altogether, these findings further demonstrate that exercise distinctly alters autophagy markers depending on the tissue, the protocol, and the presence/absence of ATG4B (Fig. 3).

Fig. 2.

Fig. 2.

Comparison of the levels of autophagy markers in white

and brown adipose tissue from wild-type and Atg4b-/- mice by

western blot. In accordance with its role in LC3B activation, the lack of

autophagy-related protein 4 homolog B (ATG4B) results in the deficient formation

of LC3B-II (and, thus, decreased LC3B-II/LC3B-I ratio), as it can be seen both in

WAT (A–H) and BAT (I–P), independently on the training protocol. As for p62,

its levels are increased in the WAT from resting autophagy-deficient mice when

compared to wild-type animals, though short-term endurance and long-term

resistance training reverse this difference (A–H). As for BAT, resting

Atg4b-/- mice develop an increasing accumulation of p62 as weeks

pass by (I–P), though this increment is significantly abolished after long-term

endurance or resistance training (M-P). N = 8 mice per genotype in 2-week-long

training protocols; N = 4 mice per genotype in 14-week-long training protocols.

Ns, no significant difference; *p

Fig. 3.

Fig. 3.

The complex regulation of autophagy in adipose tissues after endurance or resistance training, with exercise distinctly altering the autophagy markers LC3B and p62 in a context-depending manner.

Our knowledge of the link between autophagy and exercise has expanded since it was first reported [12], yet we are still far from completely understanding the role of this cellular process in training adaptation of different organs and tissues. Even though recent articles have described how endurance training affects autophagy in white adipose tissue of different animal models [12, 34, 35, 36], this is to the best of our knowledge the first study to compare and analyse different types of exercise (endurance and resistance), lengths of training protocols (2 weeks and 14 weeks) and fat tissues (WAT and BAT) in both WT and autophagy-deficient mice. The use of animal models with partial autophagy capacity facilitates the investigation of how autophagy decline (which has been already described during aging [9] and disease [37]) can hamper the beneficial effects of exercise on the elderly. In this regard, exploring the relevance of exercise-induced autophagy in adipocytes is important as training is considered one of the main strategies to counteract the consequences of hypercaloric diets and sedentarism. Moreover, animal models allow the study of organs that are not easily accessible like brown adipose tissue, which is tightly linked to the obesity pandemic. The ATG4B-deficient mice that we used in this study proved to be a valuable model when exploring all these aspects, as it shows reduced autophagy levels (similar to what happens during regular aging, rather than a complete blockage of the route) [28] and increased susceptibility to develop metabolic syndromes [33]. However, our work just focuses on the impact of exercise on adipocyte autophagy during early adulthood. Thus, further research repeating the same training protocols on old mice could be of great interest when trying to assess the autophagy-dependent benefits of exercise in the elderly.

The results that we describe here confirm that exercise can modulate autophagy in adipose tissues. The effects of training on WAT and BAT are already being established [38, 39], as well as the association between WAT reduction, BAT increment, and decreased cardiometabolic risk [24, 25, 40]. At the same time, it is well-known that autophagy plays an important role in the homeostasis of both WAT and BAT [26], and its dysregulation in WAT leads to metabolic disorders [41]. An interesting question arises when considering that exercise is a direct, physiological inducer of autophagy, hinting at the possibility that the autophagic route is mediating the beneficial effects of training in the function of the adipose tissue. In this regard, our work shows that exercise, similar to what has been described in other tissues, also alters autophagy in adipose tissue in a multifactorial-dependent way. However, we still do not know how these training protocols have an impact on adipocyte autophagy. One possibility is that exercise may activate/repress specific signalling pathways that result in autophagy regulation. This could be the case of the CaMK/SK6-eEF2, the AKT/AMPK-mTOR or the AKT-FOXO1 axes [42]. Intriguingly, all of them have been linked to autophagy modulation, hinting at a possible direct molecular connection between training and autophagy [43]. However, this catabolic pathway could also be regulated in response to metabolic changes. Autophagy plays a major role in metabolism [44], and this function can be even more relevant in metabolic tissues like the WAT and the BAT [45]. Interestingly, even though ATG4B-deficient mice do not show changes in glucose tolerance or insulin sensitivity [33], they do display a distinct metabolic footprint [46], which may predispose them to metabolic disorders during aging. For this reason, an interesting future approach would be the metabolomic comparison of rested and trained WT and autophagy-deficient mice. Last, the observed dynamic, complex regulation of autophagy in the adipose tissues could have been favoured by what is known as the “thrifty genotype”, a hypothesis that aims to explain the persistence of genes that mediate nutrient storage throughout human evolution [47]. This would mean that autophagy dysregulation could impact how adipocytes store lipids. For example, an incorrect autophagic response may affect the levels of lipophagy (the autophagy-dependent degradation of lipid droplets, which is essential for the dynamics of lipid storage), triggering lipid accumulation and cell death, and predisposing the organism to metabolic syndromes like those associated with aging [48]. For this reason, specific techniques to monitor lipophagy could provide useful insights into adipocyte homeostasis. Moreover, we did not detect major changes in fat depots from WT and Atg4b-/- mice, but an exhaustive body composition analysis (using, for example, magnetic resonance imaging) could be performed to determine fat and lean mass after training protocols.

Finally, it is important to acknowledge that, here, we only characterize the basal protein levels of LC3B (both its cytoplasmic, LC3B-I, and lipidated, LC3B-II, forms) and p62 by western blot analysis. This is a valid, good initial approach to getting valuable information about the autophagy status of a given system, but it falls short when trying to elucidate the complete autophagy flux or the regulatory systems altering the levels of autophagy markers. Thus, we believe additional studies can help to expand our knowledge on the exercise-dependent regulation of autophagy in adipose tissues [27]. As autophagy is a dynamic process, treating the mice with autophagy inhibitors (such as leupeptin, bafilomycin A1 or 3-methyladenine) or activators (like the Tat-Beclin 1 peptide, spermidine or resveratrol) would for example facilitate the full characterization of the autophagy flux in vivo conditions [27]. This effort could also be supported by complementary techniques, like the quantitation of autophagic vesicles by immunofluorescence or electron microscopy assays, or the transcriptional analysis of the expression of a wide range of autophagy-related (ATG) genes. Moreover, LC3B and p62 are bona fide markers for macroautophagy, but they do not report the status of microautophagy or CMA, alternative autophagic processes that require specific methods for their analysis. Additionally, the dissection of signalling pathways like the AMPK-mTOR axis, or the activity of transcription factors like the forkhead box class O (FOXO) protein family, would provide new insights into the regulation of the autophagy pathway in this context, clarifying the molecular mechanism that underlies the described training-dependent alteration of autophagic markers in these tissues.

Metabolic diseases are an epidemic that causes an enormous co-morbidity and a huge economic burden for the health system in developed countries [49]. Thus, it is important to define how lifestyle interventions (besides diet) can counteract the negative effects of these age-related pathologies. Given the beneficial impact of training in adipose tissues and metabolic health [23], the significant role of autophagy in age-related metabolic syndromes [50], and the autophagy-inducing effect of exercise [51], it is of great interest to clarify the crosstalk between these three components (training, adipocytes and autophagy) to improve the precision of the public health recommendations. However, the role of autophagy in WAT and BAT is complex [14]. Accordingly, we also observe this complexity when assessing exercise-dependent autophagy regulation, as we describe that different training protocols result in distinct alterations of autophagy markers in WAT and BAT. Thus, future research efforts should first focus on defining the precise role of autophagy in adipocyte differentiation and function. Then, specifying the effect of endurance or resistance training in white and brown adipocyte autophagy would allow us to develop tailored exercise interventions to counteract metabolic diseases. For instance, understanding the specific effects of resistance versus endurance training might allow for the design of exercise programs to preferentially target WAT or BAT, depending on the individual’s metabolic profile. Moreover, the duration of exercise training could also be optimized to obtain desired autophagy responses, depending on the tissue whose function we want to regulate. Thus, it is crucial to understand the underlying molecular mechanisms by which different types of exercise alter autophagy in WAT and BAT, identifying specific signalling pathways and transcriptional factors involved in the process.

In conclusion, this study shows for the first time a distinct effect of different specific training protocols (resistance or endurance exercise, with short-term or prolonged training) in the levels of autophagy markers in WAT and BAT tissues. Moreover, using ATG4B-deficient mice with a hampered autophagic response, we observed that an alteration in the correct development of autophagy cannot be fully rescued by training protocols, which is essential when trying to understand if exercise is beneficial during aging when autophagy declines.

Data presented in this study are contained within this article or are available upon request to the corresponding authors.

BFG and ÁFF designed the research study. MFS, HCM, CTZ, EIG, BFG and ÁFF trained the animals. MFS, HCM, CTZ, EIG, BFG and ÁFF collected the samples. ITG and MFS performed the biochemical analyses. ITG and ÁFF analysed the data. All authors contributed to the writing and revision of the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript. All authors have participated sufficiently in the work and agreed to be accountable for all aspects of the work.

All procedures were performed in accordance with institutional guidelines approved by Committee on Animal Experimentation of Universidad de Oviedo (PROAE 30/2016).

We thank Dr. Guillermo Mariño for shared reagents and helpful comments.

This work was supported by the Ministry of Economy and Competitiveness (Spain) under grant DEP2012-39262 to EIG and DEP2015-69980-P to BFG; and by the grant PID2021-127534OB-I00 (ÁFF), funded by the Ministry of Science and Innovation (Spain) and, as appropriate, by the European Regional Development Fund/European Union (ERDF/EU). ITG work is supported by the Ministry of Education, Culture and Sport (Spain) with a University Teaching Training (FPU) grant for PhD studies. MFS receives financial support from Foundation for Biosanitary Research and Innovation in Asturias (FINBA), “Call for predoctoral contracts for ISPA research groups”.

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Supplementary material associated with this article can be found, in the online version, at https://doi.org/10.31083/j.fbl2910348.

References

Publisher’s Note: IMR Press stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.