1 Hephaestus Laboratory, School of Chemistry, Faculty of Science, Democritus University of Thrace, Kavala University Campus, 65404 Kavala, Greece

2 Laboratory of Inorganic Chemistry, Department of Chemistry, National and Kapodistrian University of Athens, 15771 Athens, Greece

3 Department of Nutritional Sciences and Dietetics, University of the Peloponnese, 24100 Kalamata, Greece

4 Department of Dietetics and Nutrition, Harokopio University, 17676 Kallithea, Greece

5 Laboratory of Biochemistry, Department of Chemistry, National and Kapodistrian University of Athens, 15771 Athens, Greece

Abstract

Since 2000s, we have outlined the multifaceted role of inflammation in several aspects of cancer, via specific inflammatory mediators, including the platelet activating factor (PAF) and PAF-receptor (PAFR) related signaling, which affect important inflammatory junctions and cellular interactions that are associated with tumor-related inflammatory manifestations. It is now well established that disease-related unresolved chronic inflammatory responses can promote carcinogenesis. At the same time, tumors themselves are able to promote their progression and metastasis, by triggering an inflammation-related vicious cycle, in which PAF and its signaling play crucial role(s), which usually conclude in tumor growth and angiogenesis. In parallel, new evidence suggests that PAF and its signaling also interact with several inflammation-related cancer treatments by inducing an antitumor immune response or, conversely, promoting tumor recurrence. Within this review article, the current knowledge and future perspectives of the implication of PAF and its signaling in all these important aspects of cancer are thoroughly re-assessed. The potential beneficial role of PAF-inhibitors and natural or synthetic modulators of PAF-metabolism against tumors, tumor progression and metastasis are evaluated. Emphasis is given to natural and synthetic molecules with dual anti-PAF and anti-cancer activities (Bio-DAPAC-tives), with proven evidence of their antitumor potency through clinical trials, as well as on metal-based anti-inflammatory mediators that constitute a new class of potent inhibitors. The way these compounds may promote anti-tumor effects and modulate the inflammatory cellular actions and immune responses is also discussed. Limitations and future perspectives on targeting of PAF, its metabolism and receptor, including PAF-related inflammatory signaling, as part(s) of anti-tumor strategies that involve inflammation and immune response(s) for an improved outcome, are also evaluated.

Keywords

- inflammation

- PAF

- PAFR

- PAF-inhibitors

- cancer

- metastasis

- anti-inflammatory

- anti-cancer

- natural bioactives

- metal-based anti-inflammatory mediators

Albeit the promises of several anticancer approaches, cancer still remains one of the leading causes of death and a worldwide health concern [1, 2, 3]. Cancer encloses a broad spectrum of distinctive diseases hallmarked mainly by the abnormal and uncontrollable proliferation of cells that result in tumors [1, 2]. A comprehensive insight into the various signaling pathways participating in all stages cancer formation, development and metastatic progression, is essential, for designing appropriate preventative and therapeutic strategies [3, 4, 5, 6]. Most common cancer cases are known to affect human breasts, lungs, colon, rectum, skin and prostate [3, 7]. Well-established cancer risk factors, including non-intrinsic, exogenous determinants such as radiation, viruses, chemical carcinogens and unhealthy lifestyle patterns like tobacco smoke, alcohol consumption, unhealthy dietary habits and physical inactivity [3, 8, 9, 10, 11, 12], as well as endogenous risk factors (immune, hormonal, microbial, family-inherited cancer [13], DNA repair ability/inability, induced inflammation etc.) and intrinsic contributors (i.e., spontaneous errors in DNA replication), suggest some kind of causality but do not entirely account for cancer progression [1, 7, 11, 12].

Evidently, cancer emerges from the buildup of numerous genetic mutations and inappropriate expression/non-expression of associated genes (tumor inducing and/or tumor suppressing genes), as a result of the reciprocal connection between individual genetic or behavioral factors, and hence, prompts abnormalities in the control of mainly cell division, multiplication, tumor angiogenesis, and proliferation, all of which are usually associated with inflammatory manifestations [1, 3, 5, 14]. Inflammation is usually a normal response of our immune system against several insults, such as trauma and infections, but also against abnormal tumor formation and cancer. However, chronic inflammation increases the probability of cancer and enhances tumorigenesis and metastasis, by forming an inflammatory tumor microenvironment, that usually consists of engaged cancer, stromal and inflammatory cells [2, 14].

Platelet-activating factor (PAF) [15] is the most potent lipid inflammatory mediator that is implicated in chronic inflammatory manifestations involved in chronic disorders, including tumor formation and progression, through an interplay of its signaling with several cancer-related inflammatory cytokines and chemokines [1, 2]. A typical PAF molecule structure is generally known as 1-O-alkyl-2-acetyl-sn-glycero-3-phospho-choline [15], while other polar lipids and other molecules with similar structure and activity to those of PAF also exist. PAF and several PAF-like molecules are involved in many cancer-related pathological processes including angiogenesis, tumorigenesis and metastasis. A continuous inflammatory activation due to chronic or acute infections, environmental contributors, and lifestyle factors, is associated with the development of several cancer types, tumorigenesis, tumor growth and metastasis, with belligerent clinical features [16, 17]. Chronic inflammation specifically, induces carcinogenesis via reactive oxygen and nitrogen species, cytokines, PAF and prostaglandins, leading to neoplastic transformation, cancer promotion, and recurrence even after therapy. Notably, tumor cells themselves can initiate and propagate such PAF-associated inflammatory conditions that will further promote tumor development, and neo-angiogenetic and metastatic procedures [1, 2]. Therefore, systemic inflammation poses one of the predominant cancer-related mortality etiology [17, 18].

Regardless of the defining factor of malignancy occurrence, treatment-wise approaches against cancer progression can generally be categorized into the following broad categories: chemotherapy, immunotherapy, radiotherapy, and surgery with targeted therapy, hormonal therapy, and cell therapy being lesser known but of equal importance—with their usage being sometimes interchangeable and even necessary for a more sought-after clinical outcome [19, 20]. Surgery despite being hailed as the main curative treatment, isn’t always enough. Therefore, the need for a wider scope of anti-cancer curative and palliative interventions in all stages of malignancy is evident [19, 20].

Systemic Anti-Cancer Treatments (SACT), are represented by traditional chemotherapeutic cytotoxic agents further categorized as antimetabolites, DNA alkylators, DNA binders or cleavers, DNA topoisomerase inhibitors, and tubulin/microtubule inhibitors—the main mechanisms of the currently 80 cytotoxics that are heavily relied upon [21]. Immunotherapy and its biological agents as an adjuvant to chemotherapy, find application in both early and more advanced cases of cancer [22], and despite growing interest in further nano-enhancement towards selective cell-type metabolic inhibition [23], a clear survival benefit does not apply across the board [20, 24, 25, 26]. Differences in therapy type bring about different toxicities. In addition, risk factors like age along with prognostic biomarkers, frameworks, and indexes, can elucidate potential limitations of patients, mainly when palliative care is discussed—a defining example being the comprehensive geriatric assessment (CGA) for older recipients of radiation oncology services [27].

The relationship between inflammation and cancer is integrated into the clinical

setting through the realization and subsequent usage of inflammatory markers as

prognostic tools [28]. In addition, nutritional factors may modify the relation

of inflammation and cancer prognosis. For example, Nakamura et al. [22] showed that several inflammatory markers have a prognostic value only when the

patient nutritional status is taken into account with the use of the Geriatric

Nutritional Risk Index. The interaction between cancer-induced inflammatory

responses and anti-cancer therapeutic agents, dichotomizes future plans of

action, in which anti-PAF like drugs are used as an adjuvant to cancer treatment.

For example, an increase in PAF-Receptor (PAFR) expression can benefit

anti-cancer progression—via the pathway of Nuclear Factor kappa-B (NF-

On the other hand, PAFR agonists, PAF and PAF-like ligands can help tumor survival through cell proliferation and anti-cancer treatment protection [29]. Subsequently, PAFR antagonists gather growing experimental interest as an adjuvant to anti-cancer treatments [29]. PAF as a mediator of inflammatory responses among other physiological processes, can be a focal point of re-assessing its remediation, alleviating and curative potential as an anti-cancer treatment area. In the initial stages of tumorigenesis and angiogenesis, PAF can pose as a focal point of the clinical prognosis. Since the induced by PAF inflammation and associated signaling are involved in several processes that take place within the tumor microenvironment, such as a tumor induced angiogenic activation of endothelial cells that usually leads to neo-angiogenesis, and therefore colonization of other tissues, it is apparent that an anti-PAF approach can provide benefits against these inflammation related tumor metastatic procedures [1, 2].

da Silva Junior et al. [29] proved experimentally that remedies like chemotherapy and radiotherapy, induced excess production of PAF-like molecules and enhanced PAFR expression in the tumor microenvironment, while it was also discovered that PAF-antagonists reduced drastically tumor recurrence, and thus it was proposed that an assortment of chemo- and radiotherapy with PAF-antagonists, might represent an encouraging approach for addressing cancer [29]. More recently, by observing PAF’s way of generating and moving-utilizing bioactive extracellular vesicles, specifically microvesicle particles (MVPs), Travers et al. [30] revealed that pro-oxidative stressors produce oxidized PAF-antagonistic glycerol-phosphocholines, which in turn stimulate further enzymatic PAF production via PAFRs. As a result, MVPs formation and release were augmented, serving as a transmitting mechanism of PAF and similar bioactive agents and as potent PAFR antagonists [30].

Additionally, many inhibitors deriving from natural sources and especially dietary PAF inhibitors from the Mediterranean diet (MD), such as cereals, legumes, vegetables, fish, and wine, as well as MD micronutrients and extracts, could potentially hinder directly or indirectly, the pro-inflammatory activity of PAF—induced cancer [1, 2, 31]. Several bioactives found in MD foods, including polar lipids, phenolic compounds, carotenoids, terpenes, vitamins etc., favorably impact on all activity and metabolism of crucial inflammatory agents linked to chronic illnesses. These effects extend to PAF-related pathways, contributing to reduced inflammation, balanced homeostasis and lower risk of cancer and other inflammation-associated chronic health disorders [1, 2, 32].

In addition, several anti-PAF synthetic molecules have also been assessed for anti-cancer potential [2], while co-administration of potent PAF inhibitors improves remarkably the pharmacological action of cytotoxic compounds [33, 34]. Therefore, the development of new compounds that display dual anticancer and anti-PAF activities can be considered as an interesting approach in the fight against cancer. Within this point of view, recent outcomes on the anti-PAF and anti-tumor potential of “metal-based inflammatory mediators” have surfaced within the last decade as potential anti-inflammatory, anti-platelet and anti-tumor pharmaceuticals [35].

Thus, apart from the multifaceted role of PAF in cancer, tumor metastasis and anti-cancer strategies, which since 2000s we have outlined, this article thoroughly reviewes natural and synthetic bioactive molecules, such as dietary bioactives and metal-based anti-inflammatory mediators, respectively, which possess dual anti-PAF and anti-cancer activities.

Since the 19th century the German pathologist Virchow’s suggested a correlation between inflammation and cancer, based on the simple observation that inflammatory cells are present in tumor biopsies. Epidemiological studies further confirm that chronic inflammation increases susceptibility to a plethora of cancer types [36, 37]. Inflammation is the organism’s way of protecting itself from exogenous and endogenous factors like trauma, microbial infections and toxic drugs [38]. Depending on the type of stimulus, a corresponding and well-defined pathological consequence takes place aiming to help the tissue return to its basal state. Tissue dysregulation caused by modern lifestyle characteristics constitutes para-inflammation, an adaptive response less serious than chronic inflammation, which changes the baseline homeostatic checkpoints [39]. Nevertheless, para-inflammation can end up to chronic inflammation, which is in turn implicated in several chronic disorders, including cancer and its metastatic procedures.

The presence of such stimuli and other risk factors can also unfavorably deregulate the control of cell division and cell death. In this case, an uncontrolled cell proliferation and apoptosis take place, which may conclude in cancerous conditions [40]. Risk factors that influence acquired (e.g., epigenetic changes or ultraviolet-induced mutations etc.) or existing predisposition factors (e.g., genes) are important for prevention and remediation. These risk factors usually induce inflammatory manifestations, which are further implicated in the formation of tumors. Inflammation broadly categorized as acute or chronic is a key homeostatic mechanism, that is considered as therapeutic or pathological, respectively [41]. Pathologically inflamed cells are under the upregulation of mediators like PAF which work in tandem with angiogenic factors to facilitate new blood vessel growth in existing malignancies [1, 2, 42]. Angiogenesis lays the groundwork for metastasis and is the last checkpoint before drastic changes occur in prognosis.

The multifaceted process of metastasis stands as the predominant cause of mortality among patients suffering from cancer. Over the decades, major breakthroughs in perceiving all molecular and cellular mechanisms underlying this fatal progression in cancer have been made. Nevertheless, the epithelial-mesenchymal transition (EMT) and plasticity (EMP) during cancer progression, as well as the exact stage of tumor development, where a primary tumor converts into a metastatic, are still inadequately comprehended [43, 44]. Cancer metastasis, refers to the migration of cancerous cells—mainly via angiogenesis—to tissues and organs distant from the original tumor site, which in turn gives rise to new tumors (widely known as secondary and tertiary foci), thus, the induction of tumor formation in different body tissues [43, 45, 46, 47]. The crucial process of angiogenesis is vital to cancer progression and metastasis.

Specifically, during the evolving metastatic process, healthy functioning cells transform into oncogenic ones that engage in activities such as uncontrollable multiplication, immune system evasion and resistance to natural cell death enhancement, while prompting new blood vessels’ growth and tumorigenesis in remote organs, acquiring the ability to invade distant tissues and successfully surviving within the bloodstream [43, 44]. As the mass of cancerous cells expands, the formation of neoplastic blood vessels during angiogenesis ensure the provision of necessary oxygen and nutrients supply through blood stream, which further support tumor growth [2, 48, 49]. Moreover, cancerous cells may spread, invade and enter the bloodstream or lymphatic vessels, due to their direct induction of angiogenesis and thus, the creation of the acquired blood provision for secondary tumorigenesis [2, 47, 48, 49]. The primary stages of cancer metastasis, are basically the formation of the primary tumor and cancer cells invasive dissemination, followed by the intravascular expedition and dormancy of newly formatted tumor cells in the bloodstream (Circulating Tumor Cells (CTCs)) and finally their extravasation and colonization in the tumor microenvironment [45, 46, 50, 51].

Tumor-induced angiogenesis and neovascularization rely on multiple interactions among various cells, soluble substances, plus the extracellular matrix (ECM) constituents and involve four sequential stages. At first, the degradation of the basement membrane in the ECM as a result of the initiation of vessel activation [2, 52]. In particular, cancer cells trigger the activation of endothelial cells (ECs) located on prior vessels, due to the fact that cancer cells’ products/angiogenic factors, namely many cytokines and growth factors, strongly bind to their endothelium receptors, leading to said vessels’ activation. By the time vessels are activated significant proteases (serine (SPs), matrix metallo-proteases (MMPs) etc.) which disintegrate the ECM, are excreted [2, 46, 49, 52, 53].

Subsequently, ECs participate in neovascularization, assemble their cytoskeleton, and express cell-surface adhesion molecules (integrins, selectins etc.). In parallel, ECs synthesize and discharge specific proteolytic enzymatic agents, so as to be able to re-establish later on the previously-decomposed ECM. Moreover, the colonization of cancer cells to healthy tissues is based on the cancer cells’ attachment to neighboring interstitial cells and platelets enabled by specific adhesion molecules, the expression of which is favored by mediators secreted in the tumor microenvironment during neoangiogenesis [2, 44, 46]. As a consequence, the secondary and third angiogenesis phase, precisely the migration of ECs in the adjacent space and their resulting proliferation and stabilization respectively, occurs. Finally, the desired re-modelling of the ECM along with the significant lumen formation and formulated micro-vessels—maternal vessels interconnection take place, as the fourth stage of angiogenesis [2, 42, 52, 53]. The tumor induced and inflammation related processes of tumorigenesis, metastasis and angiogenesis, are intertwined and interdependent to ensure further tumor growth and colonization.

Tumor induced neo-angiogenesis is of great interest towards efficient anti-cancer strategies and therapies [2, 54]. Anti-angiogenic therapies in conjunction with immune checkpoint inhibitors, may not always prevent cell spreading [44]. Thus, establishing the biological mechanisms behind cancer metastasis is of vital importance for future identification of hidden effective prospects for therapeutic interventions and maybe as a potential forthcoming stage of overall cancer metastasis comprehension [48, 51].

Two are the primary molecular and cellular pathways connecting inflammation and

cancer: the intrinsic and extrinsic one (Fig. 1). Considering the intrinsic

pathways, many genetic alterations such as oncogenes drive the onset of

inflammation-related processes [36, 37]. In fact, intrinsic pathways connect

inflammatory constituents located in tumors to oncogenes, showing that genetic

incidences may cause neoplasia and initiate the inflammatory cascade. Main

orchestrates and pro-inflammatory mediators participating in the intrinsic

pathway of inflammation-related cancer, are oncogenes belonging to various

molecular classes and operating modes. For example, tyrosine kinases like

epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR) [55] and the rearranged during

transformation/papillary thyroid carcinoma (RET/PTC) [56] frequently induce human

cancer. Moreover, among the various identified oncogenes, frequent mutations of

the K - Rat sarcoma virus (Ras) gene, an isoform of the Ras gene for the

Ras/Rapidly accelerated fibrosarcoma (Raf)/mitogen-activated protein kinase

(MAPK) signal transduction pathway involved in cell cycle regulation, wound

healing, tissue repair, integrin signaling, cell migration and angiogenesis, is

directly involved in the formation of new blood vessels and tumorigenesis as well

as high chemoresistance [44, 57]. Nuclear oncogenes, like MYC tumor-linked

genes, produce a transcription factor overly-expressed in tumors, the

dysregulation of which initiates and sustains prime elements of the tumor

phenotype, as well as immune evasion [58]. In addition, oncosuppressors including

a plethora of tumor suppressor proteins (Hippel Lindau/hypoxia-inducible factor

(VHL/HIF) [59], phosphatase and tensin homologue (PTEN) and the transforming

growth factor-

Fig. 1.

Fig. 1.

Molecular pathways linking inflammation and cancer.

Abbreviations: Ras/Raf, Rat sarcoma/Rapidly Accelerated Fibrosarcoma; EGFR,

Epidermal Growth Factor Receptor; RET/PTC, Rearranged during

Transformation/Papillary Thyroid Carcinoma; MYC, Myelocytomatosis; VHL/HIF, The

von Hippel Lindau/Hypoxia-inducible Factor; PTEN, Phosphatase and tensin homolog;

TGF-

The extrinsic pathways are guided by inflammatory leukocytes and many soluble mediators [36, 37]. In fact, infections associated with harmful pathogens such as human immunodeficiency virus (HIV), Hepatitis B and C viruses, Helicobacter pylori, etc. have been associated with several types of cancer [61, 62]. Other inflammation-related disorders, such as autoimmune disease like Chron’s disease [37], which mainly increase the risk of colorectal cancer occurrence, Inflammatory Bowel Disease (IBD) [63], metabolic syndrome and diabetes, chronic inflammatory pulmonary disorders, as well as a constant exposure to mechanical, radiation or chemical irritants [64], are proven as some of the leading extrinsic factors promoting tumor induction and progression [36, 37]. Moreover, inflammation-related reactive oxygen species (ROS) and nitrogen intermediates, have been proven in-vitro and in-vivo to be responsible for DNA damage, implicated in abnormal cancerous cell proliferation [36, 65]. On the contrary, anti-inflammatory and antioxidant bioactives, either of natural origin or synthetic ones, have been found to beneficially down regulate such manifestations [32].

The intrinsic and extrinsic pathways at some point converge as they induce

transcription factors like the NF-

More particularly, all key-orchestrators mentioned above, organize the production of inflammatory cells (e.g., Tumor Associated Macrophages (TAM) [71], Myeloid-Derived Suppressor Cells (MDSC) [72], monocytes, vascular endothelial cells (VECs), dendritic cells (DCs), T-cells, mast cells (MCs), neutrophils including polymorphonuclear cells (PMNs) [49], as well as basophils, eosinophils etc.), as well as specific soluble mediators including growth factors, cytokines and chemokines present in the tumor micro-environment, which even though are initially expressed as a normal response to controlled apoptosis and pyroptosis, they can activate undesirable cell proliferation [39]. Interestingly, PAF is a junction mediator of such intracellular and intercellular messaging [1, 2], even between other signaling compounds [73] and acts mainly in a juxtracrine, but also in an endocrine and paracrine way [74], and thus it has also been characterized as an hormone and/or a cytokine.

PAF physiological and pathophysiological roles are tightly associated with the inflammatory responses induced by an initial stimuli, as well as with several thromo-inflammatory manifestations linked to a dysregulation of inflammation due to several reasons, including ancer-induced inflammatory response [2, 32]. Usually, in the presence of an insult like a trauma and/or an infectious agent, homeostasis is disrupted and an inflammatory response is induced to counterattack an insult. Then, the initial inflammatory stimuli for probing an homeostatic inflammatory response against this insult, usually involves also an induction of PAF-synthesis, among other inflammatory signaling, so that the acutely increased PAF-levels further instigate the initial signal for inflammation-related response and counterback of the insult.

PAF and its PAF-like homologous lipid molecules are specific, structurally defined ligands that exclusively bind and induce their biological activities through a unique seven-transmembrane G-protein-coupled receptor known as the PAF-receptor (PAFR) with exceptionally high affinity. The PAFR is expressed on the surface of various mammalian cells, such as leukocytes, neutrophils, platelets, macrophages, and endothelial cells. Binding of PAF and/or PAF-like lipids on PAFR triggers an assortment of intracellular signalling cascades that can also result in further induction of PAF-synthesis and the expression of genes for inflammatory enzymes, mediators, chemokines and cytokines and their associated receptors, including PAFR itself [32, 75, 76]. This action is followed by a subsequent initiation and/or amplification of the inflammatory processes, including those involved in the initiation and progression of various cancers [1, 2, 75]. Although the roles of PAF, PAFR and PAF-like lipids in cancer have been previously reviewed by Tsoupras et al. [2, 32], Lordan et al. [1] and Melnikova and Bar-Eli [75], still some aspects on their multifaceted roles in tumor metastatic procedures and apoptotic procedures need to be further studied and re-evaluated.

Since PAF can activate several cells even at sub-picomolar concentrations, through its binding on PAFR, PAF-levels in blood, cells, and tissues are tightly regulated by specific homeostatic metabolic pathways for its synthesis and catabolism. When the initial insult and its manifestations have been addressed by such an inflammatory response, then inflammation needs to be resolved by specific signaling that usually involves the activities of resolvins and the reduction of PAF-levels by the induction of PAF-catabolism [32]. More specifically, PAF is inactivated and catabolised by the removal of the acetyl-group on the sn-2 position of the phospholipid molecules by PAF-specific acetylhydrolase (PAF-AH, EC 3.1.1.47) to form its inactive for inflammation lyso-PAF form. The lyso-PAF is then reconverted into PAF or other phospholipids by the introduction of an acetyl group or an acyl group to the sn-2 position; hence, the biological cycle of PAF is spontaneously regulated [32, 76].

Specific metabolic pathways for PAF-biosynthesis also exist that involve the activities of important enzymes, the regulation of which play crucial role in the continuation or not of PAF-synthesis and thus the maintenance or not of the PAF-related inflammatory stimuli. PAF is synthesised by many cells, usually as a response to specific stimuli, including but not limited to cytokines, endotoxins, and Ca2+ ionophores, through two distinctive enzymatic processes; the de novo and the remodelling pathways of PAF synthesis. Interestingly, PAF itself can induce both pathways [2, 32], since binding of PAF on its receptor induce intracellular signaling [2, 32, 75], an occasion that results in an increase of its synthesis among other stimuli, while an increase of PAF levels by the induced cells or by paracrine cells or even by other types of cells, including tumor cells can further instigate PAF-synthesis by both pathways. More specifically, in the remodelling pathway, the not inflammatory active lyso-PAF is acetylated to PAF by isoforms of acetyl-CoA and lyso-PAF acetyltransferases (Lyso-PAF ATs, EC 2.3.1.67), notably LPCAT1 and LPCAT2 [76]. Lyso-PAF, the substrate for this enzymatic synthesis of PAF, is produced by the activities of the secreted or plasma form of PAF-AH, also known as lipoprotein-associated phospholipase A2 (Lp-PLA2) firstly Phospholipase A2 (PLA2), which catalyse the de-acylation/acetylation of the sn2 acyl/acetyl groups of ethyl analogues of phosphatidylcholines present in cell membranes and/or in lipoproteins, including PAF and PAF-like molecules [32, 76]. PAF production by LPCAT2 is activated usually under acute inflammatory responses, but also during chronic inflammatory conditions [32, 62], whereas the role of LPCAT1 is still under investigation, but since it is calcium—independent, it seems that it does not participate in the inflammatory processes [76]. In the de novo pathway the main regulatory enzyme is a specific dithiolthreitol—insensitive cytidine diphosphate (CDP)-choline: 1-alkyl-2-acetyl-sn-glycerol cholinephosphotransferase (PAF-CPT, EC 2.7.8.2) that catalyses PAF production by the convertion of its substrate, 1-O-alkyl-2-acetyl-glycerol, to PAF [2, 77].

PAF-CPT and lyso-PAF-AT both catalyse the final steps in each biosynthetic pathway and exhibit a basic regulatory role in PAF-production [32, 76]. It has previously been proposed that the de novo pathway is responsible for endogenous PAF production and maintains normal physiological levels of PAF, whereas the remodelling route is implicated in a faster production of PAF, when the increase of its levels is acutely needed, including an acute response to an inflammatory stimuli. Nevertheless, it is now apparent that a long-term induction of PAF-CPT by the continuous presence of a risk factor, including the manifestations taking place within a tumor microenvironment, gradually increases systemic PAF levels with related consequences [2]. Furthermore, PAF-CPT activity seems to contribute to systemic inflammation and age-related malfunctions of the central nervous system and cancer [2, 32, 77], while its inhibition has provided beneficial outcomes in several chronic disorders [1, 2, 32, 76, 77]. Thus, the downregulation of both PAF-biosynthetic pathways and an upregulation of PAF-catabolism by specific anti-PAF bioactives seem to be an important approach to tackling PAF-induced thrombo-inflammatory manifestations [1, 2, 31, 32, 76].

However, it should also be noted that during several oxidative stress related thrombo-inflammatory manifestations, several reactive oxygen species also contribute to a non-enzymatic production of PAF and PAF-like molecules by instigating the oxidation of polar lipids (phospho-/glycol-lipids), either in cell membranes and/or in plasma lipoproteins, including low density lipoproteins (LDL) and high density lipoproteins (HDL). Thus produced PAF and its PAF-like oxidized phospholipids, can also further instigate an inflammatory stimuli by binding on PAFR, which also involves further induction of inflammation and its associated oxidative stress and thus increased PAF-levels, by both the enzymatic and the non-enzymatic PAF-synthesis. Subsequently, apart from the important beneficial roles of several anti-PAF bioactives against PAF-synthesis and activities, it is also highly important that the PAF-AH enzymes are also induced, since PAF-AHs have the capacity to indirectly terminate PAF-induced signalling pathways by directly reducing either enzymatic or oxidative upregulated increases of PAF levels [32]. On the other hand the plasma form of PAF-AH (LpPLA2) has also been proposed as a biomarker of inflammatory manifestations, probably due to its continuously increased levels and activities by the long-term presence of increased PAF-levels in such conditions, while recombinant PAF-AHs have also been proposed for anti-PAF benefits. Nevertheless more research is needed to fully elucidate the importance of PAF-metabolic enzymes and their regulation on PAF’s involvement in cancer.

Within the tumor microenvironment, PAF is independently or simultaneously produced by activated ECs, inflammatory cells (leukocytes, platelets etc.), and “cancer-stroked” cells [2, 15, 29]. The increased levels of produced PAF there, can then boost cancer progression and metastatic angiogenesis [1, 3, 28, 72, 73].

Tumor-originated factors inhibit leucocytes production (monocytes,

macrophages, DCs etc.), otherwise the myelopoiesis procedure, within the tumor

host, while they amplify the expansion of immature myeloid cells [75, 78].

Multiple angiogenic tumor-derived agents/substances including cytokines such as

Interleukins (IL) (mainly IL-6 and IL-10), VEGF, tumor necrosis factor alpha

(TNF-

Interestingly, such tumor induced agents, cytokines and growth factors are also responsible for the induction and secretion of crucial lipid inflammatory mediators, including the induction of PAF-synthesis and expression of PAFR from the pre-mentioned activated endothelium within the tumor microenvironment and vice versa, while tumor cells themselves can also secrete PAF and express its receptor [2, 45, 46, 81, 82].

Several proinflammatory cytokines (TNF-

Apart from CCL2, other inflammation-associated chemokines (C-X-C motif) and chemokines ligands (CXCL), such as CXCL1, CXCL2, CXCL3, CXCL5, CXCL6 and CXCL8, along with their respective chemokine receptors (CXCR), CC chemokine receptors (CCR), CX3C motif chemokine receptor (CX3CR), and “C” sub-family of chemokine receptor (XCR), with atypical chemokine receptors (ACKRs), are also implicated in these processes [91]. MMPs regulation reportedly holds an interesting potential role too, not only in anti-inflammatory action but also in anti-metastatic effects, especially when natural bioactives like the ginsenosides are used as therapeutic agents [92]. Considering they mediate the activation of ECM along with hemopoietic cells, their potential role in supporting malignancy through dysregulation of proper angiogenesis like MMP-9, does attract attention as an adjuvant or potential biomarker of anti-cancer therapies [93].

Cells that are affected by factors of paracrine pathways, create intracellular

signal transduction pathways that influence the expression of other factors in

the equilibrium of programmed cell death. The transcription factor NF-

Such an inflammation-related cascade involving all the aforementioned pathways, cells, mediators, genes and substances, finally leads to Cancer-Related Inflammation (CRI). CRI serves as a focus for pharmacological approaches aiming to alter the host microenvironment [36, 69, 70]. Concretely, pro-inflammatory mediators, like cytokines, chemokines and especially PAF and their receptors, are potent targets for upcoming biological remedies and therapies. In fact, CRI may provide an additional viewpoint to effective responses against tumor [36, 69]. Several studies have reported that PAF and PAFR are interrelated with overall cancer development and the intrusion of several types of cancer [2], like the Epithelial Ovarian Cancer (EOC) [97].

Grasping the mechanisms of PAF activity, not only supports our better

understanding towards cancer progression and the versatile impact of

inflammation, but also may introduce potential new patterns in cancer treatment

[2, 32, 76]. For example, breast cancer cells are able to express PAFR, and produce

PAF in-vitro, when stimulated by cytokines like VEGF or TNF-

Apart from its involvement in cancer, PAF is a phospholipid inflammatory mediator implicated in several thrombo-inflammatory processes and inflammation-related disorders [32], such as cardiovascular diseases (CVD) [32], neurodegenerative [99] and renal disorders [100], diabetes [101], allergy [102]and autoimmune disorders [103], as well as several persistent infections, including COVID-19 [104, 105], HIV-induced infection [62], periodontitis [106], sepsis [107], leishmaniosis [108], etc. The binding of PAF on its 7-transmembrane G-protein-coupled PAFR initiates many intracellular signaling cascades, and then leads to various biochemical and functional pathways involved in the commencement and development of different cancers [1, 2, 29, 74, 76]. Moreover, the binding of PAF-like compounds to PAFR can also lead to various types of cellular activation in the PAF-signaling cascade, depending on the type of interaction (agonistic and/or antagonistic and/or inhibitory) [2, 76, 109, 110, 111].

The continuous presence of several risk factors associated with increased risk for several inflammation-related chronic disorders, including cancer and inflammatory metastatic manifestations, usually result in an induction and upregulation of PAF-synthesis, due to increased enzyme activities of both main regulatory enzymes of PAF-bisynthesis, PAF-CPT and Lyso-PAF-AT, as well as by oxidative stress induced non-enzymatic formation of PAF and PAF-like molecules, observed in such pathological situations. All the above usually conclude in upregulation of several inflammatory cascades, including that of the PAF/PAFR one, and a continuous inflammatory vicious cycle [32]. Such unfavorable PAF-induced inflammatory manifestations can in turn increase platelet and leukocyte reactivity and usually initiate endothelial dysfunction, which is a common step in several chronic disorders in which PAF and the PAF/PAFR signaling are implicated [32]. PAF-related inflammatory manifestations also take place inside the constructed tumor microenvironment and during inflammation-related tumor-induced angiogenesis, which usually result in tumor progression and metastasis [1, 2, 32].

PAF is plainly implicated in several cancer types such as digestive cancers,

where patients suffering from gastric adenocarcinoma develop features like

smaller-sized tumors, due to high PAFR expression [1, 112, 113]. The

over-production of PAF and over-expression of PAFR enhance tumor malignancy and

cell proliferation as reported for example in hepatocellular carcinoma [114], in

contrast to non-carcinoma specimens. Moreover, PAF is a crucial mediator in

enhancing tumor neo-angiogenesis, with an ability to directly activate

endothelial cells and indirectly mediate the process of angiogenesis. PAF’s role

in cancer metastasis is crucial, since its release by the activated endothelium

induces cellular proliferation, the production of cytokines, growth factors

or/and prostaglandins, and the expression of proteases (i.e., MMPs and SPs), all

leading to signaling cascades and the inevitable ECM degradation involved in

angiogenesis [2, 36, 115]. PAF has lately been identified as the inflammatory

mediator involved in inciting and initiating the expression of all aforementioned

angiogenic cytokine or growth factors, via the transcription factor

NF-

Fig. 2.

Fig. 2.

The implication of PAF in tumor development and metastasis Potential benefits of Bio-DAPAC-tives. (A) Several types of tumors in which PAF and its vicious inflammatory and carcinogenic cycle are involved for their progression and metastasis. (B) Magnifying the involvement of PAF and its inflammatory pathways in tumor development, progression and metastasis and the beneficial inhibitory effects of Bio-DAPAC-tives against both PAF and PAF-associated vicious carginogenic cycle; inflamed blood cells and endothelium and/or primary tumor cells secrete PAF and other inflammatory cytokines and growth factors, which further propagate an inflammatory and carcinogenic PAF-related vicious cycle of a continuous synthesis of PAF and expression of PAF-receptor (PAFR), cytokines, growth factors and their associated receptors, with a subsequent signaling that favors and induce tumorigenesis and activation of both tumor cells and the endothelium towards tumor-induced neoangiogenesis and metastasis. PAF, platelet-activating factor; Bio-DAPAC-tives, Bioactives with dual Anti-PAF and Anti-Cancer activities; SPs, serine; LPCAT2, lysophosphatidylcholine acyltransferase 2.

Cancer malignancy in PAF-related metastatic manifestations is also linked to the fact that cancer cells produce PAF themselves and express PAFR upon their membrane. For example, EGFR—evoked signaling increases PAF production in cervical and ovarian cancer cells, but the essential intertwinement between EGFR and PAF/PAFR axis, has yet to be explored [55, 119, 120, 121, 122]. Within the tumor microenvironment, PAF binding on its receptor can create interaction of tumor cells and endothelial cells that enhance cancer cell proliferation and a plethora of several intracellular signal transmissions, an intracellular state generated by the autonomous triggering of PAF mass production by cancer cells [2, 29, 73, 116, 123, 124].

In many PAF-related reports, PAF’s creation and binding to PAFR on the membrane surface of the above cells induce further PAF production, and thus the augmentation of angiogenesis. The exact timeline of the initial introduction of PAF inside the tumor microenvironment has yet to be fully clarified. Nevertheless, even in low intra-tumor PAF levels, PAF ensures proliferation, motility, neoplastic vessels’ creation and ECM degeneration. In addition, PAF boosts cancer progression, cancerous cells’ migration and adhesion molecules’ expression and thus, metastatic angiogenesis and tumor certain development [2, 3, 29, 73, 74] (Fig. 2).

Despite the fact that cancer is highly associated with PAF activity, there is

still limited evidence that all types of cancer are affected by its role, such as

thyroid cancer [125]. At the same time, the PAF/PAFR axis functions also as an

immune-suppressor by easily enhancing resilient dendritic cells (DCs)

myeloid-suppressor cells’ proliferation and as an advocate of modifications in

the tumor microenvironment via the activation of MMPs and the triggering of VEGF

production, through the NF-

Latest insights have shown that PAFR and PAF-like molecules expression is induced by radiation and that the inhibition of PAFR augments the sensitivity of cervical and squamous carcinoma cells to treatment via radiation [126]. Thus, PAF, PAF-like molecules and PAFRs’ signaling, may both directly and indirectly affect cancer and tumor progression [29]. Some carcinogenic outcomes deriving from PAF activity and pathways are displayed in Table 1 (Ref. [55, 120, 127, 128, 129, 130, 131, 132, 133, 134]). Despite the fact that PAF is not the exclusive inflammatory mediator involved in cancer and tumor metastasis, it is one of the most crucial inflammatory and cancer-related mediators, the signaling and regulation of which must be fully elucidated.

| Inflammatory Pathways | Model | Study Design | Outcomes | Main Outcomes - Conclusions | References |

| LCAT2-PAF | [55] | ||||

| PAFR | |||||

| Ras-Raf-MEK-ERK | |||||

| PI3K-Akt-mTOR | |||||

| PAFR-evoked signaling pathways | [127] | ||||

| PAFR-evoked signaling pathways | [128] | ||||

| PI3K/AKT | [129] | ||||

| Wnt/ |

[130] | ||||

| STAT3 | [131] | ||||

| Apoptotic signaling and VEGFA-VEGFR2 signaling pathways- (suspected) | [132] | ||||

| PAF/PAFR pathway | [133] | ||||

| PAF/PAFR pathway | [133] | ||||

| PAFR/Stat3 axis | [134] | ||||

| PAFR/Stat3 axis (in-vivo) | [134] | ||||

| PAF/PAFR pathway | [120] |

Abbreviations: CSE, Cigarette smoke Extract; HUC, Primary Human Urothelial Cells; HTB-9, Human grade II Urinary Bladder carcinoma cells; HT-1376, Human grade III Urinary Bladder carcinoma cells; HBMEC, Human Bladder Microvascular Endothelial Cells; FWHM, Full Width Half Max; EMT, Epithelial-Mesenchymal Transition-like phenotype; HOSE cells, Normal Human Ovarian Surface Epithelial cells; OC, Ovarian cancer; EOC, Epithelial Ovarian Cancer; CAFs, cancer-associated fibroblasts; ESCC, Esophageal cancer; MSC-CM, Mesenchymal stem cell - derived conditioned medium; GB, Gallbladder; MSCs/RFP, mesenchymal stem cells/Red Fluorescent Protein; DMSO, Dimethyl sulfoxide; PLA2G7, lipoprotein-associated calcium-independent phospholipase A2 group VII; CSC, Cancer stem cell; CC, Cervical Cancer; MTT, 3-(4,5-dimethylthiazol-2-yl)-2,5-diphenyl-2H-tetrazolium bromide; GEO, Gene Expression Omnibus; TCGA, The Cancer Genome Atlas; LIHC, liver hepatocellular carcinoma; GTEx, Genotype-Tissue Expression Program; (S)-BEL, (S)-Bromoenol lactone; PI3K, Phosphoinositide 3-kinase; PAF-AH IB2, Platelet-activating factor acetyl hydrolase IB2; WT, wild type.

Based on the above, several PAF-inhibitors of synthetic or natural origin, have

been studied for reducing the PAF-related inflammatory burden during several

chronic disorders [32], including cancer. These molecules can either inhibit the

PAF/PAFR signaling and/or modulate PAF-metabolism. Promising results show

bioactive compounds that display dual anti-PAF and anti-cancer activities

(Bio-DAPAC-tives), which affect several stages of the involvement of PAF on tumor

progression and development (Fig. 2). Concordantly, research regarding the

implication of PAF and its signaling cascade, through NF-

By re-evaluating the existing progress in cancer research and the mediators

involved, it can now be suggested that PAF’s role in cancer is not so clear,

rather than it is multifaceted. PAF may enhance tumorigenesis and metastasis but

it may also serve as a beneficial mediator. For example, the increased expression

of the PAFR has been proposed to be responsible for cell apoptosis via the

activation of the transcription factor of NF-

| Intracellular Inflammatory Pathways | Model | Study Design | Outcomes | Main Outcomes - Conclusions | Ref. |

| Wnt/ |

[130] | ||||

| MAPK Pathway (p38 and ERK1/2) | [135] | ||||

| EGFR-evoked signaling pathways | [55] | ||||

| PAF/PAFR | [127] | ||||

| PAF/PAFR | [126] | ||||

| PAF/PAFR | [132] | ||||

| LPCAT1-4 | [136] | ||||

| PAF/PAFR | [120] | ||||

| PAF/PAFR (PAF-like family) | [137] | ||||

| PAFR/Stat3 axis (in-vivo) | [134] | ||||

Abbreviations: Bio-DAPAC-tives, Bioactives with dual anti-PAF and

anti-cancer activities; BMMs, Bone Marrow Monocytes; Trap, Tartrate-Resistant

Acid Phosphatase; RANKL, Receptor Activator for NF-

Interestingly, PAF can also facilitate apoptotic cancer cell death (Table 2, Ref. [55, 120, 126, 127, 130, 132, 134, 135, 136, 137]) while it stimulates eryptosis [138, 139]. It is noted that the programmed cell death spectrum includes oncosis, eryptosis/erythrocyte apoptosis, apoptosis, pyroptosis, and necrosis [140]. Anti-tumor effect through cell cycle intervention measures is quite common, showing PAF/PAFR involvement in some cases (Table 2). PAF-related eryptosis, highlights its dual role in cancer. Eryptosis protects from intravascular hemolysis, but inflammation and cancer can cause upregulation of signaling pathways that favor it. Moreover, eryptosis is a basis of cancer-evoked anemia which worsens with certain cytotoxic treatments [141]. PAF can cause this suicidal death of erythrocytes and PAF antagonists can logically prevent it, a mechanism that could support enhanced anti-cancer cytostatic therapies, since such drugs can induce eryptosis of non-malignant cells as well [142].

Nevertheless, PAF and cell death interactions are not limited to cancer-specific eryptosis. PAF and PAFR are involved in the inhibition of neuronal pyroptosis, demonstrating neuroprotective results after after ischemia/reperfusion (I/R) injury [143]. Depending on the cancer type and progression stage, anti-PAF approaches can encompass both positive and negative effects, a characteristic that increases current research interests concerning dual anti-PAF and anti-cancer drug development.

The implication of PAF in cancer formation, development and growth, as well as tumors’ abilities to go unnoticed and eventually even recruit immunologic and inflammatory agents to survive anti-cancer strategies has also shed light on the importance of the interaction of PAF and its’ signaling with all types of anti-cancer approaches. PAF’s therapeutic and promoting role in cancer progression includes the fluctuation of PAF-like molecules concentrations along with PAFR’s transcription degree and the interaction with anti-cancer chemo-therapeutics, regardless of adjuvants. Immunotherapy may be active or passive [144] and with the use of novel biological agents, more toxicity concerns may be present. Cytokine Release Syndrome (CRS) involves a potentially lethal response to such therapies against cancer, like adoptive T-cell usage [145]. PAF has not been confirmed to mediate the CRS progression. This aspect can be addressed in the future especially since PAF remodeling has already been characterized as a focus point for Chimera Antigen Receptor (CAR) T-cell therapy enhancement for patients with multiple myeloma [146].

PAF inhibitors and PAFR antagonists show favorable results either when solely used as an anti-PAF anti-tumor approach or when they are used in combination with cytotoxic anti-cancer treatments. Recent data has shed light to the mechanism with which anti-cancer drugs may upregulate PAF production creating a negative health effect, against their initial intended cause [147]. It is therefore clear that co-treatment with PAF-inhibitors and PAFR antagonists along with traditional anti-cancer drugs needs further study.

Many endogenous or ingested PAF inhibitors have been suggested in the past few years as potential PAF-activity suppressors in a plethora of physiological and cancer therapeutic/disease prevention procedures [76, 123, 148]. Since PAF antagonists circulate in the human body, it was hypothesized that their absence could increase PAF activity [32, 76]. Nevertheless, the discovery of PAF antagonists of synthetic and natural origin, including dietary PAF inhibitors, have been thoroughly assessed and evaluated for their potential inhibitory effect against the uncontrollable PAF cancer-inducing action [2, 32, 123, 149]. PAF inhibitors are classified through several ways, including their natural or synthetic origin [76, 123, 150], their various chemical structures or their interaction with the PAF receptor [123].

According to their specificity, PAF inhibitors are categorized as non-specific and specific inhibitors [76, 123]. Non-specific PAF inhibitors encompass compounds able to impede certain actions within PAF-triggered signal transduction pathways. G-protein inhibitors or calcium channel blockers are only a few of the many non-specific PAF inhibitors, that are of low importance since they lack specificity [123, 151]. Specific PAF inhibitors that completely or incompletely bind to the PAFR, have a potential therapeutic value as shown by in-vitro studies and animal models [76, 123, 150]. For example, some PAFR specific antagonists with proved anti-cancer activity are the synthetic ginkgolides BN-50730, BN-50739 and BN-52021 [34, 82, 152], WEB-2086 and WEB-2170 [34, 152], CV-3988 [152, 153] etc., that are suggested as potent anti-cancer agents [2]. Moreover, considering the structure-activity relationships of PAF inhibitors, several dietary polar lipids [154], nitrogen heterocyclic compounds, phenolics and other compounds that affect the PAF/PAFR are promising [123, 155]. Several studies on synthetic and natural PAF inhibitors as well as dietary PAF-antagonists, which reduce and/or inhibit cancer-related PAF activities are further outlined.

Since established evidence supported the anti-cancer effects of PAF inhibitors, many synthetic inhibitors possessing anti-PAF, anti-cancer or both actions have been introduced [123]. Specifically, the first PAF-like molecule that was discovered in 1983 and is reported as a synthetic PAFR antagonist is a thiazolium derivative namely CV-3988 [150, 152, 153]. More recent reports, have outlined that this specific PAF-inhibitor exhibits significant in-vivo and in-vitro anti-PAF activity [1, 156] and anti-cancer properties, since it notably reduced the development of new vessels in a tumor generated by subcutaneously implanted MDA-MB231 breast cancer cell lines in SCID mice [34]. Additionally, benzodiazepines derivatives, including one thienodiazepine, commonly “brotizolam” [156], with anti-PAF effects against PAF-induced platelet aggregation [157, 158], have also exhibited protective effects against cancer-induced anxiety and dyspnea [159]. Moreover, hetrazepine derivatives like the thieno-triazolodiazepine WEB-2086 and WEB-2170 are selective PAFR antagonists [150, 160, 161], as well as potent inhibitors of cancer proliferation in human solid tumor cell lines, like MCF-7 and MDA-MB-231 breast adenocarcinoma cells [162]. WEB-2086 was successfully used against Ultraviolet B (UVB) radiation-induced dermatitis as well [163]. Moreover, WEB-2170 can dose-dependently inhibit in-vitro the PAF-induced platelet aggregation [164], while muscle infusion of this PAF-antagonist during reperfusion inhibited neutrophil infiltration [165]. In parallel, WEB-2170 showed anti-cancer effects in combination with dacarbazine (chemotherapeutic drug) in reducing tumor volume in mice and increasing the survival of animals with tumors in a murine melanoma model [1, 166].

Some of the first synthesized molecules, shared a PAF-like glycerol backbone including the aforementioned CV-3988 [123], plus CV-6209 [167, 168], ONO-6240 [169] and Ro 19-3704 [170], while later on, this glycerol backbone was replaced by a cyclic structure so as to form molecules like SRI-63441 [171] or UR-11353 [172] (Fig. 3). All the above molecules are depicted as potent—PAF-like—PAF and PAFR antagonists, mainly in-vitro [167, 168, 171, 172] and in-vivo [168, 169, 170]. Of these synthetic PAF-inhibitors, CV-6209 displayed strong anti-tumoral effect when infused at low concentrations in in-vitro cultured human glioma cells [173] and in-vivo mainly in CT26 tumor-bearing mice [174]. Nevertheless, recently collected data showed that Ro 24-238 as well as other PAF-antagonists like Lexipafant, Modipafant and SR27417A [175], with promising anti-PAF protection against asthma [176], were unable to easily enter the affected tissues’ cell interior so as to prevent PAFR’s nuclear transcription, while SR27417A did not show safe evidence of its treatment effectiveness against acute ulcerative colitis or cancer [177].

Fig. 3.

Fig. 3.

Synthetic specific PAF-inhibitors with both anti-PAF and anti-cancer activities.

Another important synthetic specific PAF-antagonist, Rupatadine, possesses a dual functional role: it is both an oral PAFR and an effective histamine H (1)-receptor antagonist [178, 179]. This anti-PAF inhibitor, has been successfully utilized in order to treat allergic rhinitis [179, 180]. Lately, when it was used in human Mast cells (MCs) line LAD2 and primary human lung tissue MCs (hLMCs) in cooperation with CV6209, it showed efficacy in inhibiting MC cancer degranulation at both types of cell lines [181]. Rupatadine synthetic inhibitor was also characterized as a prognostic ovarian cancer marker, since it notably inhibited—in a recent in-vitro clinical trial—cell migration and proliferation of ovarian cells [120]. All positive proved outcomes deriving from Rupatadine’s use, led to the mass production of the first circulating drug, under the commercial name “Rupafin” [123], which is widely preferred in the systemic treatment of allergic disorders [182].

In the last decade, another class of synthetic molecules with potential anti-PAF and anti-cancer benefits has been reported. Several “metal-based inflammatory mediators” with potent anti-platelet properties against several pathways of platelet activation and aggregation have strong anti-PAF and anti-thrombin effects at very low concentrations [35]. Since both PAF and thrombin are implicated in cancer formation and metastasis [2], Philippopoulos and co-workers [123] reported a series of chromium(III), manganese(II), iron(II), cobalt(II), nickel(II), copper(II) and zinc(II) complexes with strong anti-PAF and anti-thrombin properties that can also be utilized against several cancers. Based on the reported preliminary Structure-Activity Relationship (SAR) data reported, a synergetic effect indicates the positive effect of ligand coordination to a metal center, that generally leads in an increase of the anti-PAF (antiplatelet activity) of the relevant compound [123]. Interestingly, it was determined that the activities of a series of metal complexes (expressed as IC50 values) against the PAF-induced platelet aggregation were comparable with the inhibitory effect of known natural PAF antagonists from the series of Gingolides B [183], along with that of rupatadine. Additionally, some of these complexes showed an activity against PAF-basic biosynthetic and catabolic enzymatic pathways in rabbit leukocytes, underlying their potent anti-inflammatory properties [35]. The 2-(2′-pyridyl)quinoxaline (pqx) ligand comprising these metal complexes with significant anti-PAF and anti-thrombin potencies was not solely active towards PAF and thrombin. In cellular proliferation studies from our group, pqx ligand precursor was found to be quite cytotoxic in tumor-derived HeLa cells, but its toxicity was reduced upon complexation to Cr(III), Co(II), Zn(II) Mn(II), Fe(II) and Ni(II) respectively. Interestingly, Cu-pqx was found to be more effective than cisplatin, as PAF-inhibitor expressed as IC50 values.

Moreover, a library of several metal-based complexes of Rh(I)/Rh(III) and Ru(II)/Ru(III) as potent specific inhibitors of PAF has been reported, with very strong anti-PAF effects at a nanomolar to micromolar scale [184, 185, 186, 187, 188]. For some of these metal-based complexes molecular docking calculations illustrated that they can be accommodated within the ligand-binding site of PAFR and thus block PAF activity with a specific antagonistic effect against PAF. These results, along with the observed anti-ADP and anti-thromin antiplatelet properties of these complexes (rhodium case), further suggest that they can be considered as metal-based PAF inhibitors with promising antiplatelet, antithrombotic, and anti-inflammatory activities. Nevertheless, some bulkier octahedral Rh(III) complexes that could not fit into the ligand binding domain of PAFR, could instead potentially exhibit their anti-PAF activity at the extracellular domain of PAFR.

Remarkably, two of these Ru-based PAF inhibitors (complexes 25 and 26 that are displayed in Fig. 3) exhibited comparable biological activity with rupatadine fumarate, a potent PAF receptor antagonist (0.26 µM), as previously stated [178]. In-vitro cellular proliferation studies of these two Ru-based PAF inhibitors against a range of cell lines (HEK-293 and breast cancer cell lines MCF-7 and MDA-MB-468) showed that the one with nanomolar potent anti-PAF effect (IC50 = 0.18 µM against PAF) was less cytotoxic (60.2% viability on HEK-293 cells) compared to the well-established cisplatin (10.3% viability), that has an IC50 value of 0.55 µM against PAF (Fig. 4). Additionally, for the same Ru-based metal complex a moderate activity (66.5% and 70% viability) was found on MCF-7 and MDA-MB-468 cancer cells. On the other hand, the second Ru-based complex proved less potent against MCF-7 (81% viability) and MDA-MB-468 (85% viability) cancer cell lines, which further illustrates the importance of structure activity relationships for these metal complexes.

Fig. 4.

Fig. 4.

Characteristic examples of synthetic metal-based complexes as inflammatory modulators with dual anti-PAF and anti-proliferative activities against cancer cells. IC50 values in µM concentrations against the PAF-induced aggregation of washed rabbit platelets are also presented.

In line with the results reported above for the ruthenium inhibitors, strong anti-PAF effect in platelets have been recorded with some organometallic tin(II) and tin(IV) complexes bearing bulky oxygen tripodal ligands. Molecular docking calculations illustrated that these organotin analogues cannot fit inside the PAF-binding site PAFR, suggesting that they can interact with the extracellular domain of the receptor, probably inhibiting PAFR by blocking the entrance of PAF inside its receptor [180]. Interestingly, two of these organotin complexes were also evaluated for antitumor activity, on human Jurkat T lymphoblastic tumor cell line and found to be more effective than cisplatin.

Besides the coordination compounds and organometallic complexes that have been reported so far, several other copper(I) [168], Ga(III) [168] , ruthenium(II)/(III) [189], rhodium(I)/(III) [168] and iridium (I)/(III)-based inhibitors [190] of the PAF-induced aggregation in both rabbit and human platelets in-vitro, in the nanomolar and sub-micromolar range have been investigated. Experiments on human platelet-rich plasma, in conditions closer to the in-vivo ones, were also performed for a series of copper(I) and rhodium(I) complexes, against other well-established platelet agonists like ADP and collagen.

To support our findings further theoretical docking calculations are required to test our hypothesis of the most potent inhibitor that fits within the binding site of PAFR. Provided that the X-ray crystal structure of PAFR in complex with SR27417 antagonist has been recently elucidated, these results would enable us to organize better and suggest better metal-based inhibitors in the future [191]. Overall, the above results highlight the increased impact of the vast area of metal-based coordination compounds that could potentially be tested as inhibitors against the PAF-induced biological activities, and subsequently for anti-cancer benefits. It has been demonstrated that co-administration of potent PAF inhibitors remarkably improves the pharmacological action of compounds with cytotoxic properties [33, 34]. Therefore, the development of new compounds that display dual anti-cancer and anti-PAF activities can be considered as an interesting approach in the fight against cancer. Nevertheless, more studies are needed to evaluate their safety and efficacy, while in-vivo studies must be performed too in order to support the aforementioned promising in-vitro outcomes.

Several natural bioactives have been found to affect the PAF/PAFR inflammatory pathway, with favorable anti-inflammatory health promoting properties against inflammation-related chronic disorders [32], including cancer, which have previously been extensively reviewed by Tsoupras et al. (2009) [2] and Lordan et al. (2019) [1]. In these previous reviews several natural bioactives with anti-PAF activity have been outlined. From the year of 1995 and the investigation of the Swedish fauna [192], to 2009’s reviewing of anti-cancer properties of natural bioactives with anti-PAF properties [2] and 2013’s natural PAFR antagonists review efforts [193], as well as 2019’s anti-cancer dietary PAF-inhibitors potential elucidation [1], it is profound that there is a continuous assessment of anti-inflammatory natural bioactives for protection against PAF-related manifestations of cancer. In the present work the most recent outcomes on natural bioactives with both anti-PAF and anti-cancer health promoting properties are outlined and clarified.

For example, even though extensive research has been conducted in the anti-cancer properties of several phytochemicals that also possess anti-PAF properties, recent studies have outlined that bioactive phenolic compounds like resveratrol and flavonoids, demonstrate anti-inflammatory activities through the PAF/PAFR pathways and can reduce PAF-synthesis, leading to a decrease in the overall inflammatory response. The ability of these bioactive compounds to lower the levels and activity of thrombo-inflammatory mediators, namely PAF and thrombin, is rather promising against chronic diseases, including cancer [2, 32, 194, 195, 196, 197, 198, 199, 200, 201]. A classic example is resveratrol with proven anti-cancer, anti-inflammation and anti-oxidant actions [202], normally found in apples, grapes, etc., with strong anti-PAF effects in platelets and an ability to modulate PAF-metabolism towards reduced PAF-levels, which further supports its anti-inflammatory potential [2, 32, 194, 195, 196, 198, 203, 204]. Attention has also been given to resveratrol’s derivatives. For example, an anti-proliferative and anti-PAF-induced platelet coagulation study took place with a di-acetylated derivative of resveratrol, where increased anti-platelet activity of diverse derivatives exhibiting different in-vitro anti-cancer effects were observed [205].

Other natural bioactives include andrographolide,

| Type of study –inflammatory signalling | Model | Study Design | Outcomes | Main Outcomes - Conclusions | Ref. |

| Clinical Trial | HCC patients. | [207] | |||

| Clinical Trial | Chemotherapy patients. | [208] | |||

| PAF/PAFR (In-vivo) | Nude mice bearing SKOV3 cells that were grown subcutaneously as tumor xenografts. | [127] | |||

| PAF/PAFR (In-vitro) | BC cell line: MDA-MB-231. | [209] | |||

| STAT3 (In-vivo) | Hcclm3 cells in-vivo rat model. | [131] | |||

| In-vivo | BALB/c mice. | [206] | |||

| Ex vivo & in-vitro | Prostate tissue after biopsy and prostate cell lines. | [210] |

Abbreviations: Bio-DAPAC-tives, Bioactives with dual anti-PAF and

anti-cancer activities; AFP, Alpha-Fetoprotein; GB, Ginkgolide B; BMMs, Bone

Marrow Monocytes; AOM, Azoxymethane/DSS, Dextran Sulfate Sodium; HCC, Hepatocellular carcinoma; BC, Breast Cancer;

IFN-

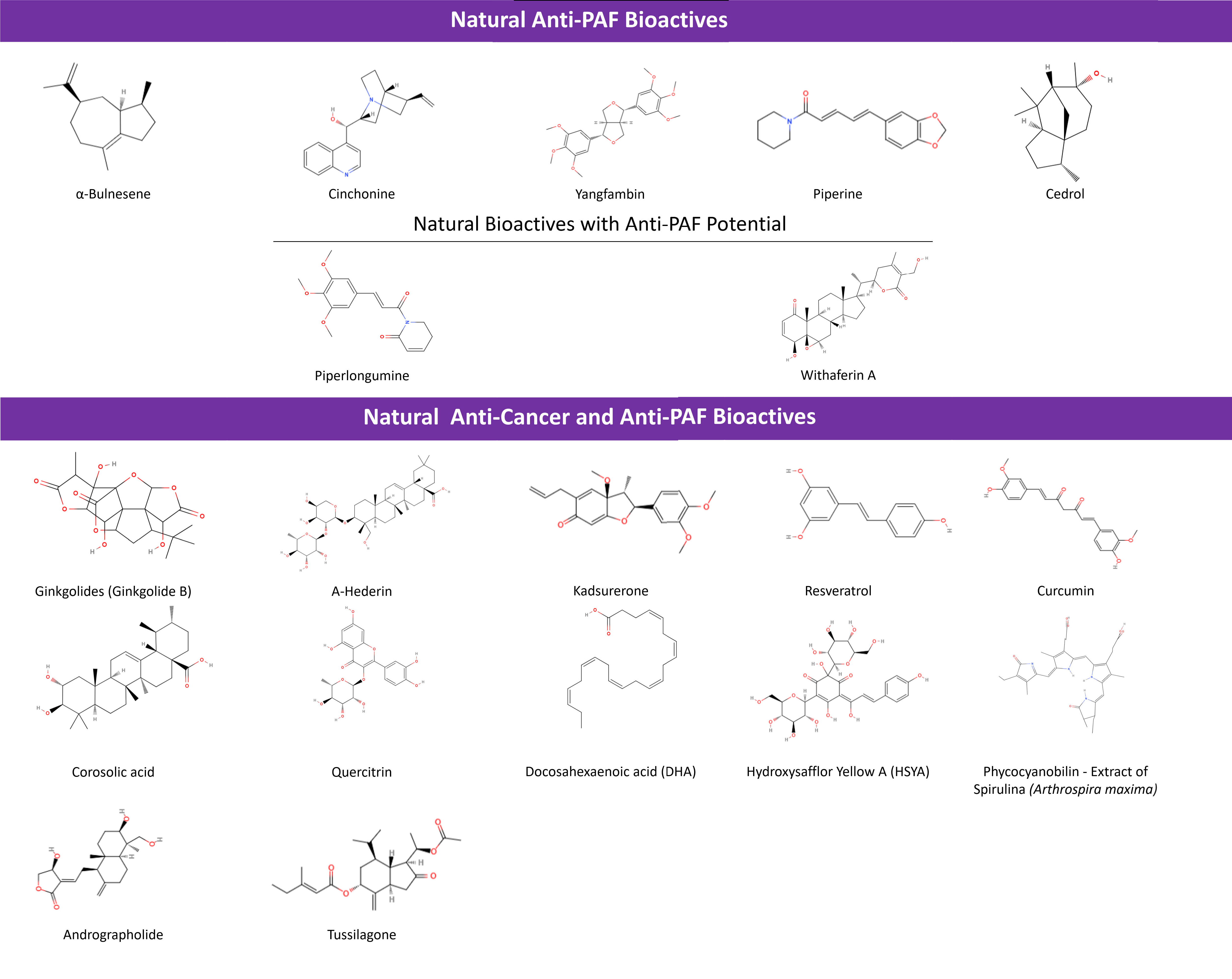

Fig. 5.

Fig. 5.

Natural Bioactives with anti-PAF and anti-cancer activities.

Such classic natural bioactives with anti-PAF and anti-cancer activity are represented clearly in the case of Ginkgolides. Their role as PAFR antagonists with anti-cancer effects, has been declared for quite some time [118, 211, 212]. In the last five, years the focus of research on these molecules has been shifted to the products of their aminolysis so as to obtain a potential enhancement of their anti-PAF activity [213]. A-Hederin and Kadsurenone have been investigated for several dual anti-PAF and anti-cancer effects with positive results (Table 3).

Other intercellular signaling pathways that involve anti-PAF action have also been proposed, including the MAPK’s signaling pathway-related Solamargine [214], LC3-I and LC3-II-related Hederagenin [215, 216], as well as Tagitinin C [215, 217], Narirutin and possibly other flavonoids [215, 218], which hold anti-cancer and anti-inflammatory potential when co-administered with traditional treatments. Whether their anti-inflammatory and anti-cancer responses could possibly be PAF/PAFR mediated should be further examined [215].

Likewise, Withaferin A, an equine known as a supplement under the name

“Ashwagandha”, promotes apoptosis of cancer cells when interacting

with signaling pathways, like STAT and NF-

Less research has been done on apigenins making tumor xenografts more susceptible to doxorubicin [223], while apigenin-derived phyto-constituents of A. elliptica exhibit anti-inflammatory [224] and anti-PAF effects [225] as extracts. Piperlongumine has shown inhibition of PAF-induced platelet aggregation [226] and cytotoxicity for HCC, with its characteristics bringing about a way to synthesize instead of plant-extracting this inhibitor, so as to research its tumor targeting [227]. Moreover, Carica papaya leaf extracts as anti-cancer bioactives have already been reviewed [228], but a combined anti-PAF involvement of the included phyto-constituents, is yet to be examined. It is noted though that the mature leaf juice inhibits PAF, while it stabilizes and increases platelet counts of thrombocytopenic rats [229].

Curcumin affecting the NF-

Tusilagone, as shown in Table 3, has also been linked to attenuating inflammation-evoked carcinogenesis in cancer-colitis rat models [206]. Moreover it inhibited cancer cell proliferation and VEGF-induced angiogenesis as suggested from in-vitro and in-vivo experiments [233]. Tussilagone originates from the herb Tussilago farfara and exhibited antiproliferative and anti-inflammatory effects in breast cancer cell lines [234].

Furthermore, if inhibitory action against secreted PLA2-IIA as a component that precedes PAF production—via lysophosphotidate conversion—is considered, then anti-PAF phytochemicals like corosolic acid [235] and quercitrin [236] can become novel choices with both anti-inflammatory and anti-tumor effect in carcinoma-bearing and EAC-bearing mice, respectively.

Marine derived natural bioactives such as dietary omega-3 polyunsaturated fatty acids (n-3 PUFA) including docosahexaenoic acid (DHA), have also been found to possess both anti-PAF and anti-cancer properties [237]. For example, DHA has been linked to a noted phenotype differentiation in an eosinophilic leukemia (EoL-1) cell line assessment and a downregulation of sPLA2, PAFAH and MYC oncogene, with a subsequent upregulation of PAFR expression. Such a PAF/PAFR involvement should be further studied and utilized for the enhancement of an anti-proliferation action against EoL-1 leukemic cells [238]. Last but not least, extracts of marine algae like Spirulina possess anti-cancer effects and anti-PAF actions [239, 240, 241]. However, no follow-up study has been conducted yet, in order to correlate these benefits, especially in-vivo [240].

By using data acquired from the Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials (CENTRAL) all reported developments on clinical trials using all aforementioned natural anti-PAF and anti-cancer bioactives, were identified and reviewed. This was facilitated by using the NCT number of the clinical trials when available, or the main ID provided by the International Clinical Trials Registry Platform (ICTRP) Search Portal. For example, natural anti-PAF bioactives like Andrographolides, have been employed in studies as an adjuvant to drugs [242, 243, 244] including capecitabine for colorectal cancer patients (NCT01993472) without posted results. Cinchonine has been studied in a dietary trial of obese adults undergoing a low-calorie diet (Main ID: ISRCTN13055163) [245] but not in cancer patients.

Piperine has been studied as a biomarker/indicator of processed red meat consumption in randomized trials, but to the best of our knowledge it has not been correlated with cancer [246]. Other bioactives combinations, namely curcumin and taurine are investigates in a phase II clinical trial probing for potential stimulation effects on HCC patients as shown in Table 3 [207]. However, piperine (Main ID: EUCTR2016-004008-71-NL) [247] along with curcumin, have been shown to diminish tamoxifen and endoxifen pharmacokinetics in breast cancer patients, compromising research and calling for monitoring of intake [248].

As aforementioned, resveratrol, is one of the most studied natural bioactive phytochemicals in a plethora of clinical studies that in the past have already been linked to anti-cancer activities, e.g., evoking apoptosis of cervical cancer cell lines [249] and acting even as an adjuvant to cytotoxic drugs, like celecoxib protecting against breast cancer in rats, undergoing carcinogen administration [250]. In the last five years and focusing on cancer, a tendency to correlate resveratrol with prostate cancer is observed. Moreover, studies seem to focus on resveratrol’s possible alleviating effects on cancer patients (Main ID: CTRI/2017/04/008376) [251], even as a way to attenuate toxicities on 5-Fluorouracil based chemotherapy recipients, in a Resveratrol-Copper state (Main ID: CTRI/2023/07/055750) [252]. As a well-known food supplement, resveratrol is currently being tested along with other safe molecules like aspirin and metformin, in their potential to prevent polyps’ reformation and possibly bowel cancer (Main ID: ISRCTN13526628) [253]. Its effect was also researched on breast cancer survivors along with an exercise regime (Main ID: RBR-87g6ny8) [254], on patients of oropharyngeal cancers undergoing chemo-radiotherapy looking for oral mucositis prevention activities (Main ID: CTRI/2019/06/019500) [255], on patients undergoing brain radiotherapy for observation of brain metastases of lung cancer (Main ID: CTRI/2020/09/027794) [256].

Curcumin has been extensively reviewed for its therapeutic roles in the past [257]. A placebo-controlled clinical trial with curcumin administration was conducted in patients with colorectal cancer undergoing chemotherapy and serum inflammatory cytokines and quality of life were assessed (Main ID: IRCT20080901001165N43) [258].

DHA in the last 5 years has been tested on breast cancers and colon cancer as

well. In the placebo controlled trial women with a history of breast cancer were

administered with a daily dose of DHA (1000 mg). While higher levels of omega-3

fatty acids were found in the blood of the intervention group, TNF-

One important and thoroughly studied natural inhibitor is Phycocyanobilin, the extract of Spirulina (Arthrospira maxima), with strong anti-PAF properties [240]. Dietary Spirulina can be co-administered with cytotoxic anti-cancer drugs to minimize myelosuppression [208]. Concordantly, it has been tested for neurotoxicity in patients with gastrointestinal cancer undergoing chemotherapy, with undisclosed results [262].

As far as Tussilagone [206],

Healthy dietary patterns like MD that are rich in anti-PAF natural dietary bioactives, have shown benefits against inflammation-related chronic disorders, including cancer [1, 2, 32]. The beneficial impact of a Mediterranean-based dietary lifestyle has been intensively studied in several chronic diseases—directly or indirectly connected to inflammation, that are often fatal—including: CVD [263], obesity [264, 265], heart failure [266], diabetes (type 1 & 2) [267, 268, 269], diabetic retinopathy [270], metabolic syndrome [271, 272, 273], frailty risk [274], Alzheimer’s disease, brain atrophy, cognitive impairment and dementia [275, 276, 277, 278, 279], and plus, asthma [280, 281, 282], allergies [280, 283], hepatic fibrosis and non-alcoholic fatty liver disease [284, 285], inflammatory bowel disease [286, 287], autoimmune diseases such as rheumatoid arthritis [288, 289], lupus [290], or Hashimoto’s disease [291] and of course—our matter of interest, cancer and other subsequent manifestations [32].

The correlation between dietary patterns and cancer, has been vigorously studied and as a result, MD, which is rich in cereals, olive oil, fruits, vegetables, fish, wine and low in saturated fats and animal-related food, is believed to protect against several cancer types and even premature mortality in general [1, 292, 293, 294]. MD’s profile is rich in many natural antioxidants, bio-functional polar lipids and bioactives that have been proved to own anti-PAF activities, however, it is yet uncertain whether the link between MD and PAF is due to the reduction of underlying inflammation caused by an antioxidative diet or if antioxidants directly affect PAF’s metabolism [1, 295]. Interestingly, the antioxidant capacity of the diet has been negatively related to PAF levels in a cross-sectional study in healthy subjects [296]. Foods included in the MD diet pyramid and their derivatives are indeed rich in anti-PAF bioactives as concluded in several clinical trials.

The results of a meta-analysis, indicated that MD is able to potentially reduce inflammation and improve the endothelial function [297], while the MD lifestyle that is comprised of high amounts of PAF-inhibitory components, is also associated with cancer prevention [298]. Although there is scientific evidence concerning the vital preventative and protective role of MD against cancer [299], it has yet to be clarified through more comprehended data, if present health-related conditions and disorders like CVD or obesity in cancer patients, are favoring or discouraging the efficacy of dietary PAF inhibitors towards PAF activity and cancer progression [1].

Global research towards MD-cancer relation has gathered a more targeted interest over the past decade (2012–2022), where the total number of studies surpassed 200, in 2021 due to cancer already being a hotspot of research [300]. Clustering results of many conducted studies suggest that the MD is highly correlated to reduced risk of overall cancer mortality, as well as of several types of cancer including head, neck, colorectal, breast, gastric, liver, stomach, pancreatic and prostate cancer, due to this diet’s high nutritional intake [280, 301].

MD is also able to reportedly modulate the diversity of the gut microbiota, which also seem to contribute in the prevention of several cancer types like colorectal and breast cancer, by mainly reducing inflammation [300, 302]. Olive oil MD-derived polyphenols own beneficial effects towards cancer and tumorigenesis, because of their interaction with the gut microbiota, their regulative role that transforms it so as to include more protective bacteria and their contained bioactive metabolites [300]. Olive oil and its polyphenols as reported, may lead to 30% lower probability of digestive cancer occurrence [303].

The European Prospective Investigation into Cancer and Nutrition (EPIC-Europe) is a long-term, large-scale collaborative project that studies different populations from countries across Europe to investigate the relationships between diet, nutrition, lifestyle, and environmental factors, and the incidence of cancer and other chronic diseases. It is one of the largest cohort studies in the world, with more than half a million participants recruited across 10 countries in western Europe. EPIC-Europe was launched in the 1990s and has been going on for more than 30 years. The multicenter EPIC study found that the highest-recorded MD score was related to 7% reduction in total cancer risk in both male and female genders [304].