1 Center for Endocrine Metabolism and Immune Diseases, Lu He Hospital, Capital Medical University, 100000 Beijing, China

2 Beijing Key Laboratory of Diabetes Research and Care, 100000 Beijing, China

†These authors contributed equally.

Abstract

Non-alcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD) is a group of metabolic liver illnesses that lead to accumulation of liver fat mainly due to excessive nutrition. It is closely related to insulin resistance, obesity, type 2 diabetes, and cardiovascular disease, and has become one of the main causes of chronic liver disease worldwide. At present, there is no specific drug for the treatment of NAFLD; lifestyle interventions including dietary control and exercise are recommended as routine treatments. As a drug for the treatment of type 2 diabetes, sodium-glucose co-transporter type 2 (SGLT-2) inhibitors may also play a beneficial role in the treatment of NAFLD. This article reviews the mechanism of SGLT-2 inhibitors in the treatment of NAFLD.

Keywords

- SGLT-2 inhibitors

- non-alcoholic fatty liver disease

- non-alcoholic steatohepatitis

- type 2 diabetes

Non-alcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD) is a group of liver diseases associated with metabolic dysfunction, such as diffuse non-alcoholic liver steatosis, non-alcoholic steatohepatitis (NASH), and other features of liver damage, such as liver cirrhosis and hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) [1]. NAFLD is defined as the presence of steatosis in more than 5% of hepatocytes and the absence of causes like excessive alcohol consumption, drugs, or other chronic liver diseases. NAFLD has become one of the main reasons for chronic liver disease around the world. The prevalence of NAFLD is reported to be about 25% worldwide, ranging from 13.5% in Africa to 31.8% in the Middle East [2, 3].

NAFLD has become the fastest-growing factor in HCC in some western countries [4]. The leading factor contributing to the development of NAFLD is overeating, which leads to the accumulation of adipose cells in the liver tissue. NAFLD is interrelated with metabolic syndromes (MS) such as insulin resistance (IR), obesity, and type 2 diabetes (T2DM), which increases the risk of cirrhosis and related complications [2]. Furthermore, studies have indicated that NAFLD is also related to cardiovascular diseases [5], chronic kidney diseases [6], and the long-term risk of developing extrahepatic cancers [7].

The pathogenesis of NAFLD is complex and not yet clearly understood, so there is still a lack of specific drugs for its treatment, and lifestyle interventions are currently being used but with limited success [1]. Studies suggest that the novel hypoglycemic drug class of sodium-glucose cotransporter-2 (SGLT-2) inhibitors shows a favorable effect in the treatment of NAFLD [8, 9]. Thus, this review summarizes the clinical studies and possible mechanisms of SGLT-2 inhibitors in the treatment of NAFLD and may provide some ideas for the treatment of NAFLD.

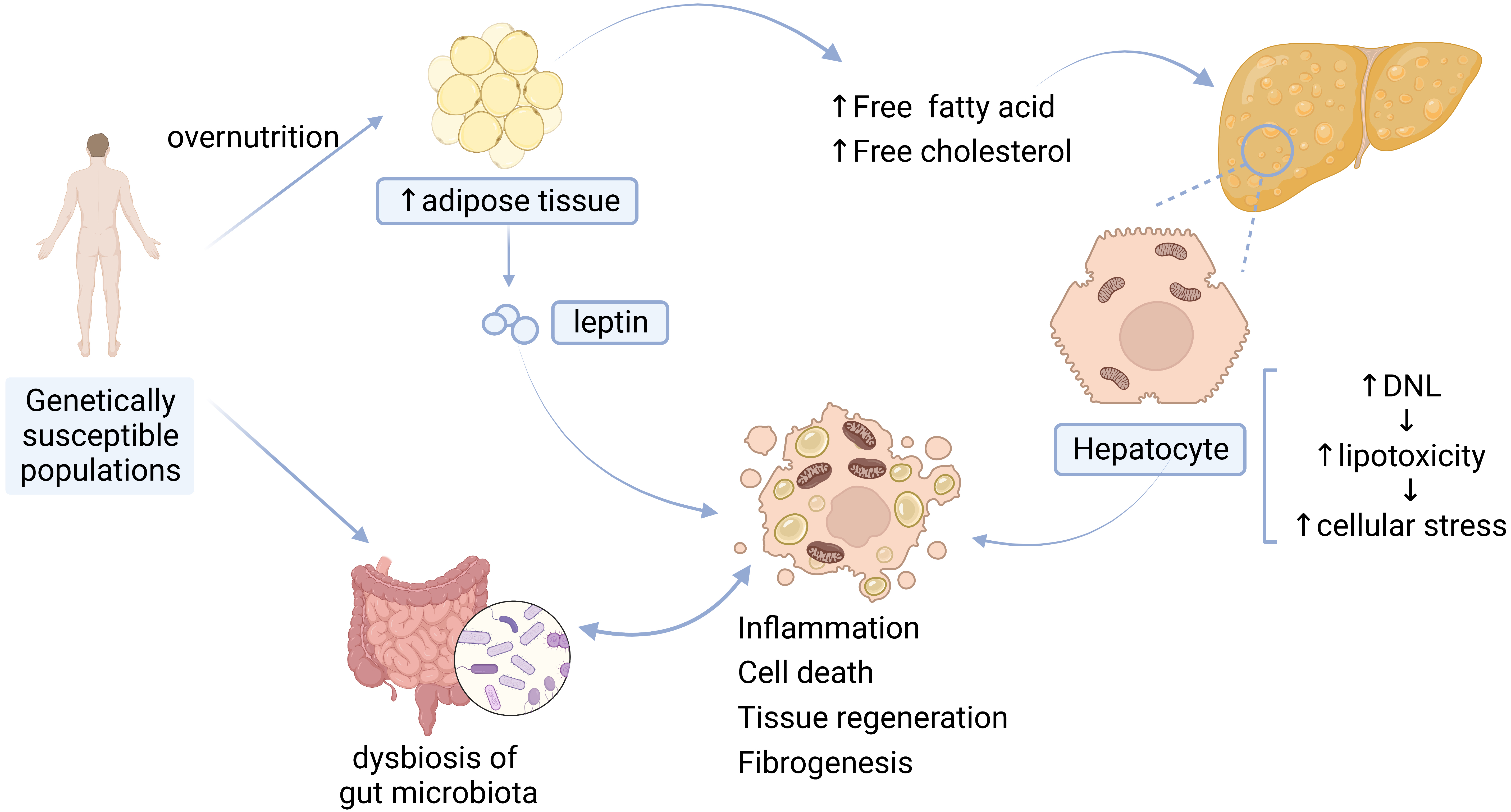

The pathogenesis of NAFLD is complicated and still needs to be further investigated. The “multiple-hit” hypothesis proposed that multiple injuries act together on genetically susceptible subjects to induce NAFLD. These injuries include adipokines secreted by adipose tissue, IR, gut microbiota, and inflammation [10] (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1.

Fig. 1.Pathogenesis of NAFLD. DNL, de novo lipogenesis.

The main driver of NAFLD is overnutrition, which leads to the excessive accumulation of adipose tissue in the liver and exceeds the liver’s metabolic capacity [2]. Accumulation of high levels of free fatty acids (FFA), free cholesterol, and other lipid metabolites leads to increased lipotoxicity [10], further contributing to cellular stress such as oxidative stress and endoplasmic reticulum (ER) stress [2], production of reactive oxygen species (ROS), mitochondrial dysfunction [10, 11], inflammasome activation [12], and apoptotic cell death, and subsequent inflammatory stimulation, tissue regeneration, and fibrogenesis [2].

Adipokines secreted by adipose tissue in the liver promote the development of NAFLD. (1) Leptin is synthesized and secreted from fat cells [13]. Higher levels of circulating leptin are associated with increased severity of NAFLD can boost inflammation and can increase susceptibility to hepatotoxicity [14]. (2) Adiponectin is a kind of adipokine that possesses hepatoprotective effects. Decreased levels of adiponectin have been found in individuals with NAFLD, and the levels of adiponectin are inversely related to the severity of steatosis, necroinflammation, and fibrosis [14].

IR, which is characterized by reduced glucose disposal in adipose tissue or muscle, is a crucial factor in the development of NAFLD [10, 15]. Research has suggested that IR drives hepatic de novo lipogenesis (DNL) in patients with NAFLD [16]. Hepatic DNL is a highly regulated metabolic pathway by which cells convert excess carbohydrates (usually glucose) into fatty acids [11], and then cause the inappropriate release of fatty acids through dysregulated lipolysis, subsequently leading to impaired systemic insulin signaling [15].

Growing evidence has suggested that gut microbiota also acts as a significant driver to facilitate the occurrence and development of NAFLD, and to accelerate its progression to cirrhosis and HCC. The gut microbiota and its metabolites can directly affect intestinal morphology and immune response, leading to abnormal activation of inflammation and intestinal endotoxemia. Dysbiosis of the gut microbiota can also result in dysfunction of the gut-liver axis (physiological crosstalk between the liver and gut [12]) by changing the bile-acid metabolic pathway [17, 18].

Inflammatory activation is involved in the occurrence of NAFLD/NASH. Inflammation of the liver triggered by hepatocyte death, gut barrier dysfunction, adipokines, etc., contribute to the development of NAFLD [19]; the development of NASH is also the result of abnormal activation of conventional immune cells, parenchymal cells and endothelial cells of the liver in response to inflammatory mediators from the liver, adipose tissue and the gut [20].

As mentioned above, NAFLD has a bidirectional association with IR, obesity, and T2DM [2]. NAFLD and T2DM are two pathological conditions that often coexist and interact with each other, and T2DM can increase the risk of adverse hepatic and extra-hepatic outcomes [21]. A large meta-analysis involving 49,419 T2DM patients from 20 countries demonstrated that the global prevalence of NAFLD in T2DM patients is 55.5% [22]. There is growing evidence indicating that NAFLD may precede or promote the development of T2DM and that the risk of developing T2DM parallels the severity of NAFLD [21]. Mechanically, evidence suggests that hepatic lipid accumulation is associated with IR and an increased risk of T2DM, and reduced hepatic lipid accumulation is also associated with a reduced risk of developing T2DM [21, 23]. However, the specific mechanism of the increased risk of T2DM in NAFLD patients has not been clarified.

Since NAFLD is tightly related to T2DM, and IR also plays a vital role in the pathogenesis of NAFLD, hypoglycemic drugs have shown beneficial effects in the treatment of NAFLD (Table 1, Ref. [24, 25, 26, 27, 28, 29, 30, 31, 32, 33, 34, 35, 36, 37, 38, 39, 40, 41, 42]). Among these glucose-lowering drugs, SGLT-2 inhibitors have promising applications due to their advantages of improving intrahepatic IR and alleviating hepatic steatosis, etc.

| Hypoglycemic drugs | Hepatic beneficial effects | Adverse effects |

| SGLT-2 inhibitors | ||

| Pioglitazone | ||

| GLP-1RA | ||

| DPP-IV inhibitors | ||

Note:

4.1.1.1 Sodium-Glucose Co-Transporter Type 2 (SGLT-2) Inhibitors

SGLT-2 inhibitors (e.g., canagliflozin, dapagliflozin, empagliflozin) are the newest class of anti-diabetic medications and have shown some beneficial effects in the treatment of NAFLD. Clinical trials suggest that SGLT-2 inhibitors treatment is associated with the improvement of liver steatosis in NAFLD [24]. A meta-analysis shows that SGLT-2 inhibitors are effective in reducing aspartate aminotransferase (ALT), gamma-glutamyl transferase (GGT), and can also decrease the absolute percentage of liver fat content (LFC) on MRI in overweight or obese patients with NAFLD [25]. SGLT-2 inhibitors can reduce body weight in patients with or without T2DM [26, 43, 44], decrease plasma triglyceride (TG), and increase high-density lipoprotein (HDL) to improve dyslipidemia [27], which can be profoundly helpful in alleviating hepatic steatosis and improving NAFLD [45, 46]. SGLT-2 inhibitors can also alleviate IR and improve insulin sensitivity in high-fat diet (HFD) mice [28]. Furthermore, animal studies suggest evidence that canagliflozin attenuated the development of NASH and prevented the progression of NASH to HCC in the mouse model of diabetes and NASH/HCC [47]. In summary, SGLT-2 inhibitors can reduce LFC, improve hepatic steatosis, lower liver enzyme levels, improve dyslipidemia in patients with NAFLD, as well as improve IR, enhance insulin sensitivity and prevent the progression of NASH to HCC in mouse models, and SGLT-2 inhibitors probably are among the potentially effective drugs for the treatment of NAFLD.

4.1.1.2 Pioglitazone

As an insulin sensitizer, pioglitazone has been shown to improve liver function in NAFLD or NASH subjects [48]. Clinical study results showed that pioglitazone treatment improved fibrosis scores, reduced liver TG levels, improved insulin sensitivity in the liver, and made the resolution of NASH [32]. Treatment with pioglitazone, even at low doses, can also significantly improve hepatic steatosis in T2DM patients [33].

4.1.1.3 Glucagon-Like Peptide Receptor Agonists (GLP-1RAs)

GLP-1RAs (e.g., dulaglutide, exenatide, semaglutide) can reduce lipotoxicity by decreasing liver fat deposition, increasing hepatic insulin sensitivity by reducing steatosis, modulating liver fibrosis, and slowing down the progression of NAFLD to NASH [36]. GLP1-RAs can ameliorate steatosis, ballooning, and lobular infiltrates of NASH or achieve remission of NASH without worsening fibrosis [37].

4.1.1.4 Dipeptidyl Peptidase (DPP)-IV Inhibitors

DPP-IV inhibitors (e.g., sitagliptin, saxagliptin, linagliptin) are agents that can improve IR. Experiment have revealed that DPP-IV inhibitors attenuate NAFLD activity score (NAS) and fibrosis stage in the HFD-induced NAFLD mouse model [40]. The beneficial effect was likely achieved by restoring the gut-liver axis [49], reducing hepatic lipogenesis, and downregulating the expression of adipogenesis genes [41]. However, the beneficial effects of DPP-IV inhibitors on human NAFLD are still debated in clinical trials [50, 51, 52, 53], and strong clinical evidence for their clinical use in NAFLD/NASH is still lacking [38].

Altogether, SGLT-2 inhibitors benefit NAFLD remission not only by directly improving intrahepatic steatosis, reducing LFC, and improving liver enzyme levels, but also by improving systemic metabolic status by reducing body weight, lowering plasma TG levels, improving IR, and increasing insulin sensitivity. Therefore, SGLT-2 inhibitors may be at the top of list of hypoglycemic agents in the treatment of NAFLD.

In addition to the above-mentioned hypoglycemic drugs that are effective in treating NAFLD, there are also several novel drugs are currently in development or have entered clinical trials, Table 2 (Ref. [54, 55, 56, 57, 58, 59, 60, 61, 62, 63, 64, 65, 66, 67, 68, 69, 70, 71, 72, 73, 74, 75, 76, 77, 78, 79, 80, 81]) provides a brief overview of the experimental drugs that have progressed to clinical trials.

| Types of drugs | Hepatic outcomes | Diabetic outcomes | Refs |

| FXR | [54, 55, 56] | ||

| PPAR agonists | [57, 58, 59, 60] | ||

| THR |

[61, 62] | ||

| ACC inhibitors | [63, 64, 65, 66] | ||

| FAS inhibitors | [67, 68] | ||

| SCD1 inhibitors | [69, 70] | ||

| DGAT inhibitors | [71, 72, 73] | ||

| KHK inhibitors | [74] | ||

| MPC inhibitors | [75, 76] | ||

| FGF19 | [77, 78] | ||

| FGF21 | [79, 80, 81] |

The effect of Semaglutide in Subjects With Non-cirrhotic Non-alcoholic Steatohepatitis (NCT04822181): A clinical study that is under Phase 3 study about the effect of Semaglutide, a GLP-1 receptor agonist, on NASH.

Note:

Due to the different groupings and drug doses in clinical trials, the

p-values for the above data changes were not necessarily

Lifestyle interventions include a combination of calorie restriction and

exercise [11], which are currently the therapeutic strategies for NAFLD in the

absence of approved pharmacological therapies [82]. In patients with NAFLD,

exercise alone without dietary intervention can reduce intrahepatic triglycerides

(IHTG). A combination of diet and exercise can significantly reduce the level of

IHTG over exercise alone, as well as ameliorate glucose control and insulin

sensitivity [83]. Strong evidence showed that weight loss can alleviate liver

disease to some extent;weight loss of

Bariatric surgery is an effective treatment for weight loss and can lead to improvement in comorbidities as well [86]. A prospective study involving 109 patients found that after 1 year of follow-up, bariatric surgery contributed to the disappearance of NASH in nearly 85% of patients and the subsiding of fibrosis in 33% of patients [87]. Another 5-year follow-up of NASH patients who underwent bariatric surgery, showed results that were also consistent [88]. In addition, in patients with NASH and obesity, bariatric surgery is associated with a significantly lower risk of major adverse liver outcomes and major adverse cardiovascular events than did non-surgical treatment [89]. Bariatric surgery seems to be a beneficial option for obese patients with NASH, but the safety of bariatric surgery has not been well established [86]. Bariatric surgery may only be considered in highly selected patients with obesity and compensated cirrhosis [90].

The main common clinical SGLT-2 inhibitors include canagliflozin, empagliflozin, and dapagliflozin, and Table 3 (Ref. [29, 91, 92, 93, 94, 95, 96, 97, 98, 99, 100]) shows a summary of clinical studies on different SGLT-2 inhibitors for the treatment of NAFLD.

| Types of drugs | Study population | Duration (weeks) | Hepatic benefits | Diabetic benefits | Refs |

| Canagliflozin | T2DM, NAFLD | 48 | [91] | ||

| T2DM, NAFLD | 24 | [92] | |||

| T2DM, NASH | 12 | [93] | |||

| Dapagliflozin | T2DM, NAFLD | 24 | [94] | ||

| T2DM, NAFLD | 12 | [95] | |||

| T2DM, NAFLD | 12 | [96] | |||

| NAFLD | 12 | [97] | |||

| Empagliflozin | T2DM, NAFLD | 20 | ↔ | [29] | |

| NAFLD | 24 | [98] | |||

| T2DM, NAFLD | 24 | [99] | |||

| T2DM, NASH | 24 | [100] |

Note:

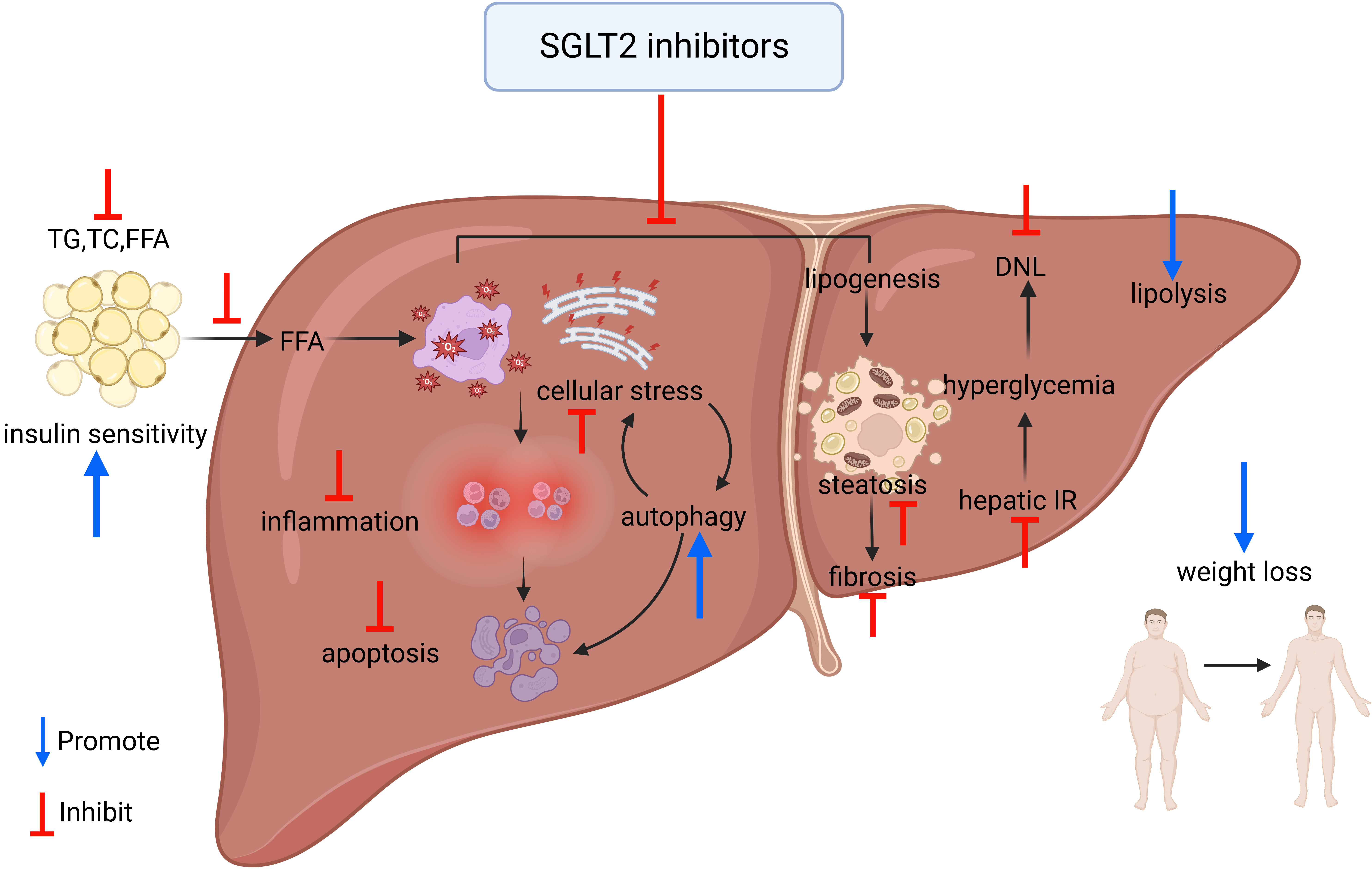

As previously mentioned, SGLT-2 inhibitors might be a potential approach for the treatment of NAFLD and have shown different beneficial effects. However, the exact mechanism by which SGLT-2 inhibitors ameliorate the liver injury associated with NAFLD remains unclear [101] (Fig. 2).

Fig. 2.

Fig. 2.Overview of the mechanism of improvement of NAFLD by SGLT-2 inhibitors. TG, triglyceride; TC, total serum cholesterol; FFA, free fatty acid; IR, insulin resistance; DNL, de novo lipogenesis.

The liver is an important metabolic organ in which metabolic function is

controlled by insulin and other metabolic hormones; aberrant energy metabolism in

the liver is related to NAFLD [102]. Insulin is the main regulator of glucose,

lipid, and protein metabolism. When plasma glucose concentration increases,

insulin secretion of

Fat accumulation is the main cause of the occurrence and development of NAFLD; SGLT-2 inhibitors can inhibit the production of liver fat and improve hepatic lipid metabolic disorder.

In HFD-induced mouse models, administration of canagliflozin reduced hepatic

lipid accumulation, downregulated lipogenesis markers (SREBP-1c and FASN), and

upregulated lipolysis markers (CPT1a, ACOX1, and ACADM) [105]. Animal studies

also suggest that canagliflozin can promote lipolysis by upregulating the hepatic

zinc-

Empagliflozin hinders hepatic lipogenesis by increasing the expression of

PPAR-

Inflammation activation participates in the development of NAFLD and NASH; studies suggest that SGLT-2 inhibitors also can inhibit the process of inflammation and thereby alleviate liver steatosis and fibrosis.

Canagliflozin suppressed the production of inflammatory

cytokines, such as TNF-

Dapagliflozin can reduce hepatic steatosis and fibrosis in high-carbohydrate

high-fat-induced NAFLD [107], which is accomplished by decreasing the DNL enzyme

ACC1 and upregulating the fatty acid oxidation enzyme ACOX1 [114]. It also

significantly reduces inflammatory factors such as TNF-

Cellular stress, such as oxidative stress and ER stress, is an important factor that produces the death of hepatocytes. SGLT-2 inhibitors can alleviate cellular stress and prevent hepatocyte apoptosis.

Animal studies have suggested that canagliflozin reduces hepatic oxidative stress and enhances the activity of antioxidant enzymes as well as enhances total antioxidant capacity [106]. Canagliflozin can lower hepatic inflammatory cytokiness levels, decrease serum caspase-3 levels, and enhance the expression of hepatic Bcl-2 to prevent hepatocyte apoptosis [106, 116] (Caspase-3 and Bcl-2 are factors that belong to the liver apoptosis pathway and relate to the attenuation of liver injury [117]).

Empagliflozin can reduce HFD-induced ER stress by downregulating the expression of genes involved in ER stress, such as CHOP, ATF4, and Gadd45 [28], thereby inhibiting the apoptotic process in hepatocytes [118]. Additionally, empagliflozin can enhance autophagy of hepatic macrophages via the AMPK/mTOR signaling pathway, and further inhibit IL-17/IL-23 axis-mediated inflammatory responses, thereby significantly attenuating NAFLD-related liver injury [101].

Ipragliflozin can enhance the concentration of FGF21, a key hepatokine with beneficial properties [119], thus significantly improving oxidative stress, inflammation, and fibrosis [107].

Insulin is produced in islet cells of the pancreas and mostly cleared in the

liver. Hepatic insulin clearance (HIC) helps regulate insulin action by

controlling insulin availability in peripheral tissues, and is closely related to

hepatic lipid content and glucose metabolism [120]. Reduced HIC, due to obesity

and liver fat accumulation, is one of the causes of inappropriate

hyperinsulinemia and IR [121], and hyperinsulinemia is thought to play an

important role in the pathogenesis of NAFLD and NASH [122]. SGLT-2 inhibitors are

believed to increase HIC and improve

The influence of NAFLD is not limited to the liver. NAFLD has extra-hepatic consequences such as renal and cardiovascular disease. Chronic kidney disease (CKD) and NAFLD share pathogenic mechanisms including IR, lipotoxicity, inflammation, and oxidative stress [125]. SGLT-2 inhibitors are sodium-glucose cotransporter inhibitors, which have hypoglycemic effects by inhibiting the reabsorption of glucose in the proximal convoluted tubule, leading to substantial glucosuria and a reduction in plasma glucose levels. SGLT-2 inhibitors reduce afferent arteriolar vasoconstriction and may provide nephroprotection by attenuating glomerular hyperfiltration [126], decreasing inflammation, fibrogenic responses and cell apoptosis, preventing glucose overload-induced oxidative stress [127] and reducing serum uric acid levels [128]. SGLT-2 inhibitors also have the potential for cardiovascular protection by reducing inflammation [129], expediting lipolysis, and by other mechanisms.

Although the SGLT-2 inhibitors play a crucial role in the treatment of NAFLD, there are adverse effects and potential limitations in their clinical use. First, SGLT-2 inhibitors can significantly increase the risk of urinary tract and genital infections [130]. Therefore, clinicians should avoid adding SGLT-2 inhibitors in people with pre-existing urinary tract infections. Patients should also be advised to increase water intake and for women to keep the vulva clean during treatment. Second, SGLT-2 inhibitors reportedly can increase the risk of diabetic ketoacidosis. In some cases, blood glucose levels are normal or only mildly elevated, which may delay diagnosis. Hence, clinicians should be aware of identifying the presence of diabetic ketoacidosis. Regardless of blood glucose levels, patients taking SGLT-2 inhibitors who have symptoms of, or triggers for, ketoacidosis should be checked for ketone levels [30]. Third, T2DM is a risk factor for osteoporosis, and previous studies have suggested that the use of SGLT-2 inhibitors may increase the risk of fractures. However, recent studies have suggested otherwise [131], and the effect of SGLT-2 inhibitors on fractures is still controversial. Therefore, bone mineral density and fracture-risk assessment should be considered in the clinical setting for patients at higher risk of fracture [132]. Fourth, recent studies suggest that there is no evidence of increased renal risks in using SGLT-2 inhibitors; canagliflozin [133] and dapagliflozin [134, 135] are approved for chronic kidney disease and diabetic kidney disease (DKD); also, the annual rate of decline in the estimated glomerular filtration rate(eGFR) was slower in the empagliflozin group than in the placebo group [136]. Consequently, SGLT-2 inhibitors can be considered for treatment of stage 4 CKD and albuminuria.

Taken together, the results suggest that SGLT-2 inhibitors show potential for the beneficial treatment of NAFLD by alleviating hepatic steatosis and fibrosis, lowering liver enzyme levels, improving hepatic and systemic insulin resistance, reducing body weight, and so on. In patients with NAFLD combined with T2DM, SGLT-2 inhibitors are recommended in the absence of contraindications. For patients with NAFLD combined with obesity, SGLT-2 inhibitors have also shown some therapeutic effects, and if weight loss is difficult to achieve or ineffective, SGLT-2 inhibitors can be tried without contraindications. However, the application of SGLT-2 inhibitors requires attention to possible side effects such asdiabetic ketoacidosis, and urogenital infection, and monitoring of liver and kidney function is highly recommended.

IR, insulin resistance; TG, triglyceride; NAS, NAFLD activity score; LFC, liver

fat content; HDL, high-density lipoprotein; HFD, high-fat diet; PPAR-

BZ provided the conception and design of the manuscript, and agree to be accountable for all aspects of the work; RX and DL drafted the manuscript and reviewed the intellectual content critically; ZC and YX analyzed and interpreted data of the work; YanW, LM and YuanW acquired data of the work, and reviewed the manuscript critically. All the authors read and approved the manuscript.

Not applicable.

Not applicable.

This research received no external funding.

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

Publisher’s Note: IMR Press stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.