1 Department of Cytophysiology, Chair of Histology and Embryology, Faculty of Medical Sciences in Katowice, Medical University of Silesia in Katowice, 40-752 Katowice, Poland

2 Students Scientific Society, Chair of Histology and Embryology, Faculty of Medical Sciences in Katowice, Medical University of Silesia in Katowice, 40-752 Katowice, Poland

3 Department of Experimental Medicine, Medical University of Silesia in Katowice, 40-752 Katowice, Poland

4 Department of Pathomorphology and Molecular Diagnostic, Faculty of Medical Sciences in Katowice, Medical University of Silesia in Katowice, 40-752 Katowice, Poland

†These authors contributed equally.

Abstract

Background: In humans, chronic liver disease (CLD) is a

serious clinical condition with many life-threatening complications. Currently,

there is no therapy to stop or slow down the progression of liver fibrosis.

Experimental mouse models of CLD, induced by repeated intraperitoneal injections

of carbon tetrachloride (CCL

Keywords

- experimental models of hepatotoxicity

- galactosoamine

- carbon tetrachloride

- chronic liver failure

- stem cell therapy

In humans, chronic liver disease (CLD) is a large group of clinical conditions

characterized by impairment of liver function and morphology lasting over 6

months. The most common causes of CLD are alcohol consumption and viral

infection. Less common etiological factors of CLD include nonalcoholic

steatohepatitis, biliary obstructive disorders, right sided heart failure,

Wilson’s disease, hemochromatosis, and chronic use of specific medications [1].

Regardless of the etiology, untreated CLD leads to cirrhosis, which is defined as

pathological remodeling of the liver parenchyma with fibrotic scar formation and

presence of regenerative nodules. The pathogenesis of this disease involves the

destruction of parenchymal cells by the causative agent. Apoptosis or necrosis of

hepatocytes induces an inflammatory reaction that activates hepatic stellate

cells (HSCs) via multiple cytokines such as IGF-1, TGF-

Animal models of hepatotoxicity induced by hepatotoxins, including carbon

tetrachloride (CCl

In the present study, we compared the development of histopathological changes

induced in Sprague Dawley rat and BALB/c mouse experimental models by repeated

injections of CCl

The study was performed on two-month-old male Sprague Dawley rats weighing

180–220 g, and six-week-old male BALB/c mice weighing 18–25 g, purchased from

the Animal House of the Center for Experimental Medicine (CMD) of the Medical

University of Silesia in Katowice. During the experiment, the animals were housed

in cages (six per cage) under standard conditions of temperature (22

°C

The study was approved by the Local Ethics Committee for Animal Experiments of the Medical University of Silesia (decision no. 18/2018). Rats and mice were treated in accordance with the Directive 2010/63/EU on animal experimentation.

The animals were randomly divided into 4 groups (18 individuals per group).

D-galactosamine hydrochloride (no. 22981; Cayman Chemical; Ann Arbor, Michigan,

USA) was dissolved in physiological saline. Carbon tetrachloride (no. 118804704;

Chempur; Piekary Śl

| Hepatotoxin | Control groups | Chronic liver injury | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Rats | Mice | Rats | Mice | |

| Carbon tetrachloride | 200 |

25 |

100 |

12.5 |

| D-GalN hydrochloride | 250 |

125 |

25 mg/100 g bw, twice a week | 75 mg/100 g bw; twice a week |

During autopsy, 1 mL of orbital sinus blood was collected. Alanine transaminase (ALT), aspartate transaminase (AST), and alkaline phosphatase (ALP) activities and total protein (TP) were measured to assess liver injury by liver function tests. Blood tests were performed on a chemistry analyzer (AU480; Beckman Coulter, Brea, CA, USA) according to protocols provided by the manufacturer. In addition, blood smears stained with May Grunwald-Giemsa stain were done to assess cell morphology. Serum biochemistry tests and blood staining were performed in the Silesian Analytical Laboratory (Katowice; Poland).

The excised sections of the left liver lobe were fixed in 10% buffered formalin

solution, dehydrated, and embedded in paraffin. The obtained paraffin blocks were

cut into 4

The severity of hepatitis was assessed by a simple grading algorithm evaluating

parenchymal injury and interface hepatitis. Normal liver parenchyma was graded as

(0). Hepatitis was graded as follows: minimal (1), mild (2), moderate (3), and

marked and/or multiacinar bridging necrosis (4) [24, 25]. Liver steatosis was

graded as follows:

The progression of liver fibrosis was evaluated by Sirius red staining, which

was performed to visualize collagen fibers. Liver sections (4

To quantify the percentage area occupied by collagen fibers, fifteen random

fields of 0.0944 mm

The localization of cells expressing Ki-67, a marker of proliferation,

Before incubation with the primary antibody, the sections intended for Ki-67 visualization were incubated for 60 min with a citric acid-based antigen unmasking solution (Vector Laboratories; Newark, CA, USA) for antigen retrieval. Non-specific antibody binding was then blocked using 2.5% equine serum (Vector Laboratories; Newark, CA, USA) for 60 min. Subsequently, liver sections were incubated with anti-Ki67 (SP6) antibody (ab16667; Abcam, Cambridge, United Kingdom) diluted 1:400 for 20 h at 4 °C and with anti-rabbit secondary antibody conjugated with peroxidase (Vector Laboratories; Newark, CA, USA) at room temperature for 30 min. Appropriate positive controls were created as sections taken from human tonsils.

Liver sections intended for identifying apoptotic cells and, separately,

alpha-smooth muscle actin (

Final visualization was achieved by using diaminobenzidine (Vector Laboratories;

Newark, CA, USA). On each slide, ten random fields of 0.3779 mm

Small sections taken from the liver were homogenized using a Unidrive X 1000 homogenizer (CAT, Ballrechten-Dottingen, Germany). Total cellular RNA was isolated using the commercially available RNA Extracol reagent (Eurx, Gdańsk, Poland) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Nucleic acid concentration and quality were measured with Nanodrop ND-2000 (Thermo Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA). RNA was stained with Simply Safe (Eurx, Gdańsk, Poland) and visualized after agarose gel electrophoresis.

Ribonucleic acid was reverse-transcribed into complementary deoxyribonucleic

acid (cDNA) using total RNA and random hexamer primers of the smART First Strand

cDNA Synthesis Kit (Eurx, Gdańsk, Poland) and

The expression of eight genes involved in liver fibrosis, angiogenesis,

oxidative stress, lipid metabolism, and carcinogenesis (Table 2, Ref. [32, 33, 34, 35, 36, 37])

was detected using FastStart Essential DNA Green Master (Roche, Basel,

Switzerland) in Light Cycler 96 (Roche, Basel, Switzerland). All samples were

tested in triplicate. The oligonucleotide primers used in the reactions were

purchased from Sigma Aldrich Company (St.Louis, MO, USA). Each run was

completed using melting curve analysis to confirm the specificity of the

amplification and absence of primer dimers. The relative expression of the

examined genes was calculated according to the 2

| Gene name | Gene abbreviation | Function | References |

|---|---|---|---|

| Type I collagen | COL1A1 | Liver fibrosis | [32] |

| Type III collagen | COL3A1 | ||

| Transforming growth factor beta | TGF- | ||

| Tyrosine-protein kinase Met | c-Met | Angiogenesis | [33, 34] |

| Hepatocyte growth factor | HGF | ||

| Cytochrome P450 2E1 | CYP2E1 | Oxidative stress | [35] |

| Peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor alpha | PPAR- |

Lipid metabolism | [36] |

| Growth arrest and DNA-damage-inducible protein alpha | Gadd45a | Carcinogenesis | [37] |

The data was analyzed using the Statistica 13 computer software (StatSoft

Polska, Kraków, Poland). Parametric analysis of the obtained results was

performed using one-way ANOVA with appropriate post-hoc tests. The Kruskal-Wallis

test was used if normal distribution could not be assumed. For independent

groups, Student’s t-test was also used where appropriate. Differences

were considered as significant if p

In rats intoxicated with CCl

| Time point | Leukocytes [10 |

Lymphocytes [%] | Monocytes [%] | Eosinophils [%] | Band neutrophils [%] | Segmented neutrophils [%] |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Carbon Tetrachloride Rats | ||||||

| Control | 5.0 (3.0–5.2) | 74 (67–79) | 0 (0–0) | 0 (0–2) | 1 (0–3) | 20 (15–25) |

| 2 w | 6.9 (6.8–7.0) | 53 (50–55)* | 2 (1–2)* | 0 (0–0) | 1 (0–2) | 45 (43–47)* |

| 4 w | 6.2 (4.8–7.5) | 77 (69–85) | 0 (0–0) | 2 (1–2) | 2 (1–3) | 20 (12–27) |

| 6 w | 5.5 (5.0–9.0) | 67 (59–77) | 0 (0–0) | 1 (1–2) | 1 (1–3) | 31 (20–37) |

| 8 w | 6.0 (5.2–10.5) | 73 (28–84) | 0 (0–0) | 0 (0–1) | 2 (0–3) | 26 (14–69) |

| 10 w | 6.0 (2.3–6.7) | 54 (21–75) | 0 (0–1) | 2 (0–2) | 1 (0–4) | 43 (18–79) |

| 12 w | 1.7 (1.5–1.8) | 76 (76–76) | 0 (0–0) | 2 (1–2) | 3 (2–3) | 20 (19–21) |

| Carbon Tetrachloride Mice | ||||||

| Control | 4.5 (3.8–5.0) | 46 (42–47) | 0 (0–2) | 0 (0–1) | 0 (0–1) | 53 (50–58) |

| 2 w | 5.6 (4.5–6.7) | 19 (11–26)* | 5 (1–9) | 2 (0–3) | 2 (1–2) | 74 (68–79)* |

| 4 w | 3.4 (2.3–4.5) | 61 (59–62)* | 0 (0–0) | 1 (0–1) | 0 (0–0) | 39 (37–41)* |

| 6 w | 3.8 (1.8–6.0) | 44 (33–50) | 1 (0–2) | 0 (0–0) | 0 (0–0) | 55 (48–67) |

| 8 w | 4.8 (4.5–5.0) | 44 (42–46) | 1 (0–1) | 0 (0–0) | 0 (0–0) | 56 (53–58) |

| 10 w | 15.0 (12.0–18.0)* | 22 (18–24)* | 4 (4–5)* | 0 (0–0) | 0 (0–1) | 74 (72–76)* |

| 12 w | 4.5 (3.0–7.5) | 50 (34–56) | 2 (2–6) | 0 (0–0) | 0 (0–0) | 48 (42–60)* |

| D–Galactosamine Rats | ||||||

| Control | 2.5 (2.2–4.0) | 78 (76–88) | 0 (0–0) | 2 (2–6) | 2 (0–5) | 15 (8–18) |

| 2 w | 6.0 (5.8–8.5)* | 66 (64–71)* | 0 (0–1) | 2 (0–3) | 1 (0–3) | 31 (26–33)* |

| 4 w | 4.5 (3.5–7.5) | 78 (72–81) | 0 (0–0) | 1 (0–2) | 1 (0–3) | 21 (16–25) |

| 6 w | 3.8 (3.0–4.0) | 79 (67–90) | 0 (0–0) | 1 (1–7) | 1 (1–1) | 18 (8–25) |

| 8 w | 4.0 (3.0–5.7) | 86 (74–88) | 0 (0–0) | 1 (1–2) | 2 (0–2) | 11 (8–25) |

| 10 w | 4.2 (2.5–4.8) | 74 (45–75) | 0 (0–1) | 3 (1–4) | 1 (0–1) | 24 (22–49) |

| 12 w | 4.6 (3.8–5.3) | 78 (70–86) | 0 (0–0) | 4 (1–7) | 2 (2–2) | 16 (11–21) |

| D–Galactosamine Mice | ||||||

| Control | 4.5 (4.5–4.5) | 62 (48–62) | 3 (0–4) | 0 (0–2) | 0 (0–1) | 38 (31–49) |

| 2 w | 6.0 (3.8–12.0) | 57 (54–64) | 1 (0–3) | 1 (0–1) | 0 (0–3) | 36 (36–44) |

| 4 w | 2.5 (2.0–3.0)* | 71 (70–93) | 0 (0–1) | 0 (0–0) | 0 (0–1) | 29 (6–29) |

| 6 w | 2.5 (2.4–4.5) | 66 (61–74) | 0 (0–0) | 0 (0–0) | 0 (0–0) | 34 (26–39) |

| 8 w | 2.2 (1.8–2.5* | 71 (67–75) | 0 (0–0) | 1 (0–1) | 1 (0–1) | 29 (25–31) |

| 10 w | 4.5 (3.0–6.0) | 51 (49–58) | 0 (0–0) | 0 (0–0) | 0 (0–0) | 49 (42–51) |

| 12 w | 5.5 (5.0–6.0)* | 67 (53–74) | 1 (1–2) | 0 (0–0) | 1 (0–2) | 31 (22–46) |

| Data are presented as a median (min-max). No basophils were identified in blood

smears; n = 3. *p | ||||||

Changes in the percentage of blood cells in the group of CCl

The obtained data indicate that there are only minor changes in the percentage

of white blood cells, caused by long-term administration of CCl

We did not observe significant changes in ALT and AST activities in rats and

mice intoxicated with CCl

| Time point | Alanine transaminase (ALT) [U/L] | Aspartate transaminase (AST) [U/L] | Alkaline phosphatase (ALP) [U/L] | Total Protein [g/dL] |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Carbon Tetrachloride Rats | ||||

| Control | 50.7 (49.3–66.2) | 201.6 (131.4–260.4) | 229.5 (172.5–289.4) | 6.2 (5.7–6.3) |

| 2 w | 106.4 (84.8–128) | 254.25 (230.3–278.2) | 234.05 (194.4–273.7) | 6 (5.8–6.2) |

| 4 w | 96.1 (78.4–113.8) | 197.9 (197.6–198.2) | 320.75 (316.4–325.1) | 5.9 (5.9–5.9) |

| 6 w | 65.3 (49.7–68.3) | 226.4 (214.3–272.6) | 211.5 (157.3–219.7) | 5.9 (5.3–6.3) |

| 8 w | 108.1 (66.5–113.2) | 215.5 (170–237) | 208.2 (198.3–272.1) | 5.5 (5.2–5.6) |

| 10 w | 82.3 (58.7–92.3) | 191.2 (188.8–229.3) | 384.3 (242.9–522.9) | 5.4 (5.2–6) |

| 12 w | 76.35 (62.5–90.2) | 212.15 (166.1–258.2) | 190 (175.9–204.1) | 5.6 (5.6–5.7) |

| Carbon Tetrachloride Mice | ||||

| Control | 137.1 (128.5–274) | 989 (923.3–1054.7) | 65.5 (54–79.3) | 4.7 (4.6–5) |

| 2 w | 117.85 (117.7–118) | 694.85 (666.2–723.5) | 108.65 (93.9–123.4) | 5.4 (4.7–6.1) |

| 4 w | 95.9 (78.8–113) | 1070.55 (611.6–1529.5) | 132.95 (131.5–134.4)* | 5.25 (5–5.5) |

| 6 w | 174 (77.3–194.7) | 1325.5 (599.9–1459) | 121.8 (117–127.9)* | 5.5 (5.3–6) |

| 8 w | 195.35 (163.2–227.5) | 779.5 (538.8–1020.2) | 110.95 (97.6–124.3)* | 5.25 (5.2–5.3) |

| 10 w | 393.6 (322.1–594.8) | 1430.3 (968.9–1791.2) | 128.2 (118.8–134.5)* | 5.6 (5–6.4) |

| 12 w | 100.1 (99.6–180) | 512.2 (446.3–1276.7) | 94 (93.3–105.4)* | 4.6 (4.4–5) |

| D–Galactosamine Rats | ||||

| Control | 51.6 (48.7–61.5) | 198.4 (178–220.2) | 202 (154.3–268.9) | 6.2 (6–6.3) |

| 2 w | 62.5 (53–66.9) | 228.5 (172.6–245.6) | 303.2 (245.2–340.6) | 5.8 (5.7–6.1) |

| 4 w | 77.9 (67.8–87.4)* | 220.3 (203.1–299.2) | 276.7 (235–319.2) | 6 (5.7–6.3) |

| 6 w | 59 (41.2–69.5) | 211.6 (195.8–233.8) | 343.3 (247.3–357.2) | 5.9 (5.7–6) |

| 8 w | 60.8 (54.4–83.9) | 194.6 (188.4–199.4) | 283.7 (261.9–327.5) | 5.6 (5.2–5.8)* |

| 10 w | 64.7 (58.8–73.4) | 243.8 (193.2–262.5) | 260.9 (195.8–335.8) | 5.8 (5.5–5.9)* |

| 12 w | 58.2 (52.5–84.2) | 253.5 (212.2–348.7) | 333.5 (239.1–381.9) | 6.1 (5.9–6.2) |

| D–Galactosamine Mice | ||||

| Control | 143.6 (134.6–206.8) | 1049.6 (636–2328.7) | 114.3 (105.6–119.6) | 4.5 (4.4–5.1) |

| 2 w | 103.5 (76.5–183.9) | 560.8 (453.1–1571.8) | 125.3 (119–130) | 4.7 (4.4–4.8) |

| 4 w | 195.2 (111.9–232) | 1033.9 (279.7–1431) | 121.8 (98.6–144.5) | 5.1 (5–5.2) |

| 6 w | 155.05 (130–180.1) | 1403 (780.5–2025.5) | 117.25 (112.4–122.1) | 5.3 (5.1–5.5) |

| 8 w | 124.4 (65.8–167.1) | 626.8 (198.5–1672.2) | 105.8 (86.1–107.2) | 4.6 (4.5–5) |

| 10 w | 145 (92.6–153.5) | 675.7 (504.8–1141.6) | 105 (102.2–106) | 4.7 (4.4–5) |

| 12 w | 94.1 (92.2–106) | 605.3 (559.2–703) | 98.7 (84.7–104.7) | 4.5 (4.3–5) |

| Data are presented as median (min-max); n = 3. *p | ||||

Similarly to blood smears, we did not observe a clear pattern of long-term changes in serum parameters, reflecting toxic effects of both toxic compounds.

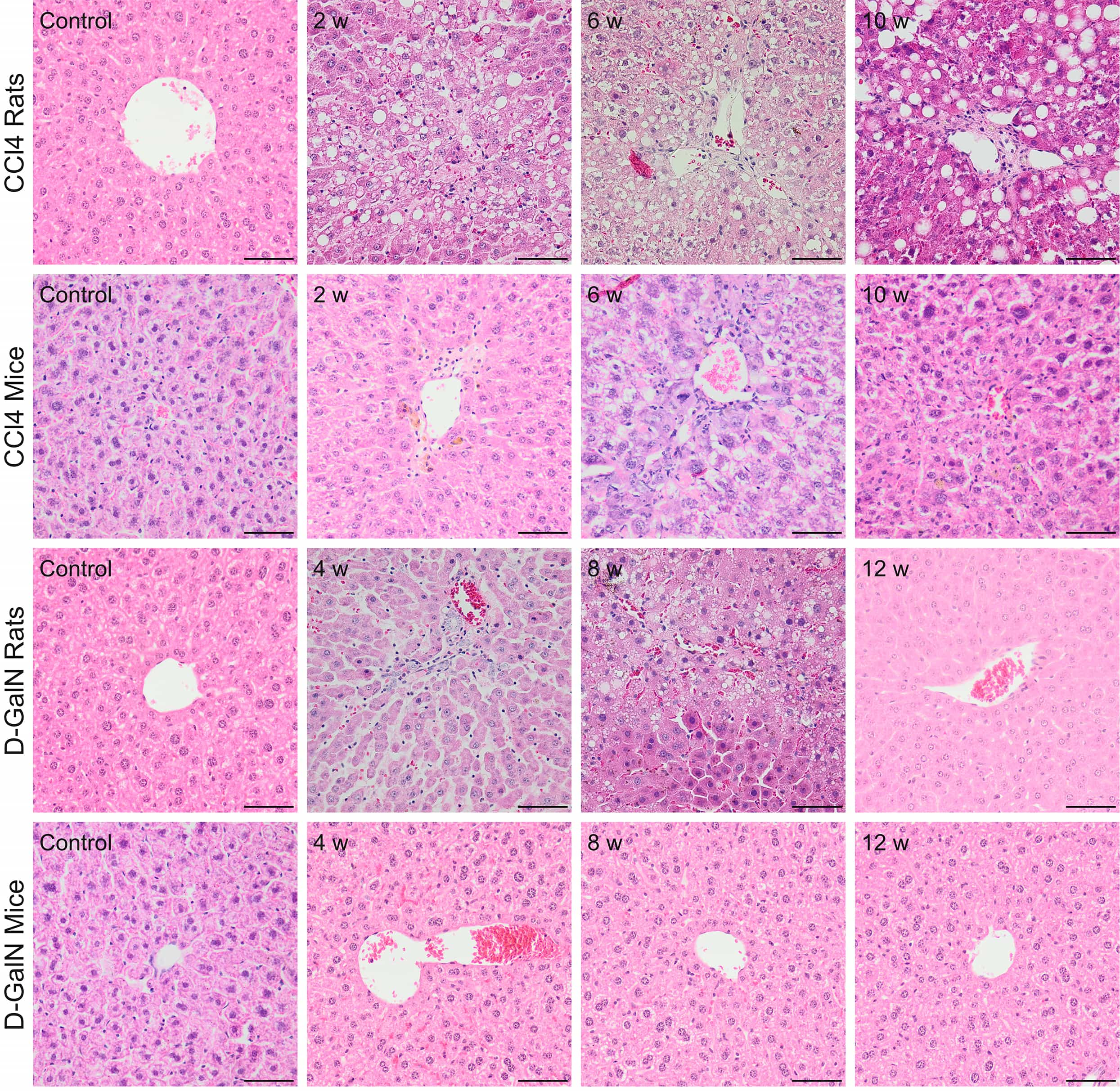

Most CCl

Fig. 1.

Fig. 1.Histopathological changes in zone 3 (pericentral) of the hepatic

acinus in rats and mice after repeated CCl

| Histopathological grading (0–4) | Steatosis (0–3) | Fibrosis: Ishak score (0–6) | ||||

| Carbon tetrachloride | ||||||

| Rats | Mice | Rats | Mice | Rats | Mice | |

| Control | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| 2 w | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 2 | 3 |

| 4 w | 1 | 1 | 2 | 0 | 3 | 3 |

| 6 w | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 4 | 3 |

| 8 w | 1 | 3 | 1 | 0 | 4 | 3 |

| 10 w | 2 | 4 | 1 | 0 | 4 | 4 |

| 12 w | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 5 | 4 |

| D-Galactosamine | ||||||

| Rats | Mice | Rats | Mice | Rats | Mice | |

| Control | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| 2 w | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| 4 w | 2 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 |

| 6 w | 2 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 |

| 8 w | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 3 | 0 |

| 10 w | 1 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 3 | 1 |

| 12 w | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 3 | 1 |

| Histopathological grading is the median of three animals. n = 3. | ||||||

In mice treated with CCl

In D-GalN-intoxicated rats, we observed mild hepatitis at weeks 4 and 6 of intoxication. During this period, we observed inflammatory infiltration in zone 1 of the hepatic acini (around portal areas) and ballooning degeneration around the central veins in zone 3. At a later time point, hepatitis slowly decreased (Fig. 1, Table 5).

We did not observe any histopathological changes in the livers of D-GalN-treated mice (Fig. 1, Table 5).

To sum up, in CCl

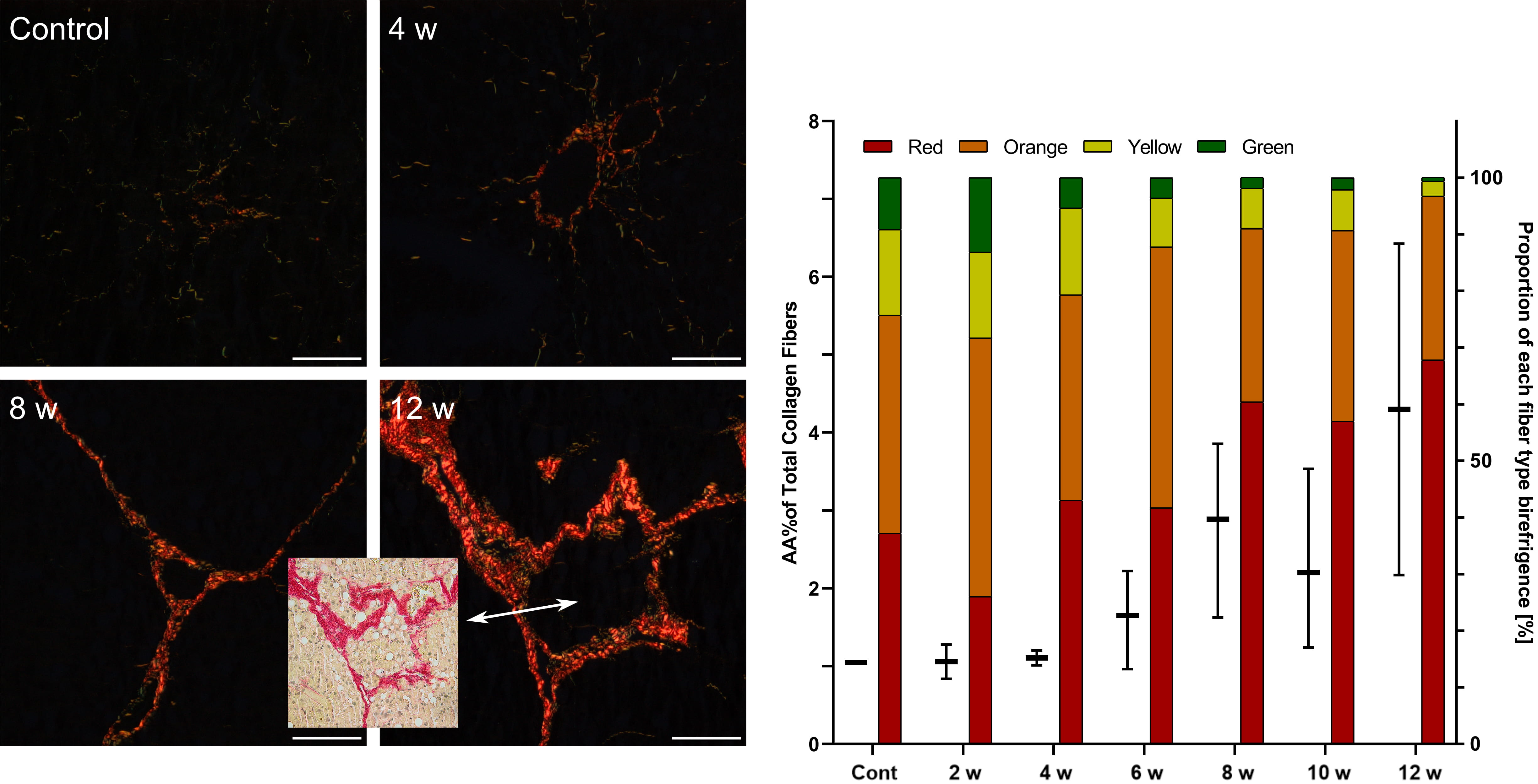

In animals of the control groups representing normal parenchymal architecture of the liver without fibrous expansion, the area of fiber deposition was 1% in rats and 0.37% in mice (Table 5, Figs. 2,3,4,5).

In the groups of CCl

Fig. 2.

Fig. 2.Assessment of fibrosis in the livers of rats after repeated

CCl

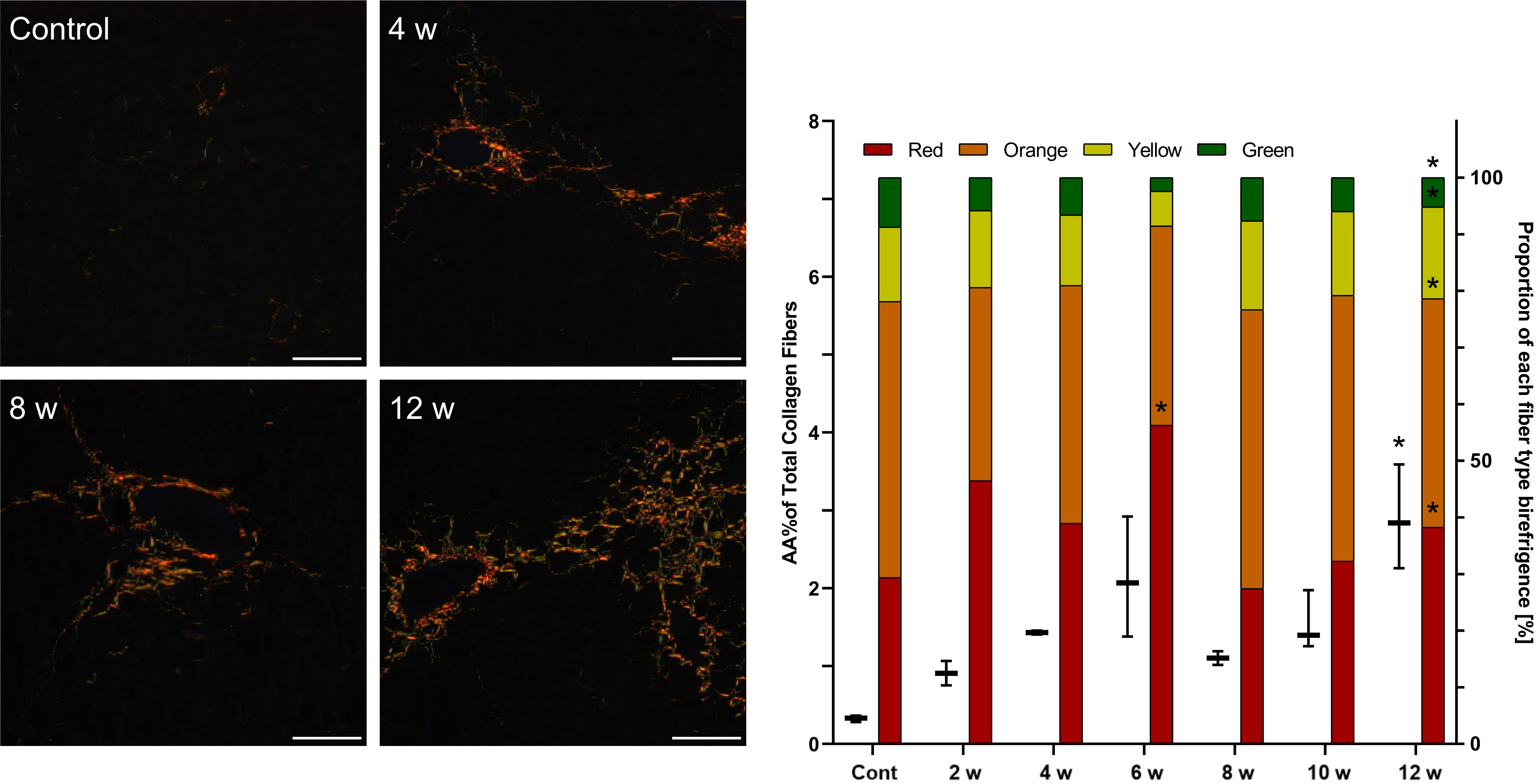

In CCl

Fig. 3.

Fig. 3.Assessment of fibrosis in the livers of mice after repeated

CCl

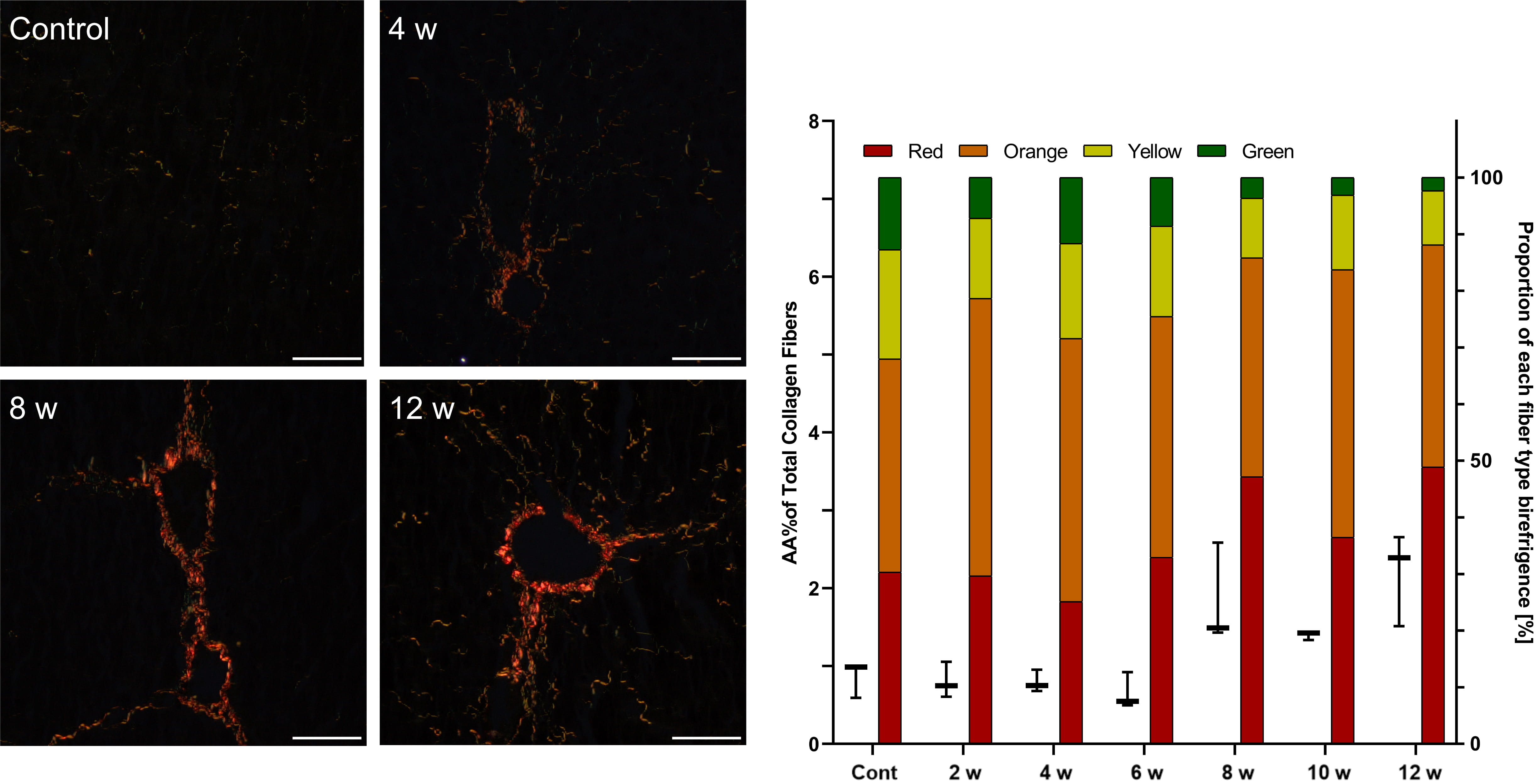

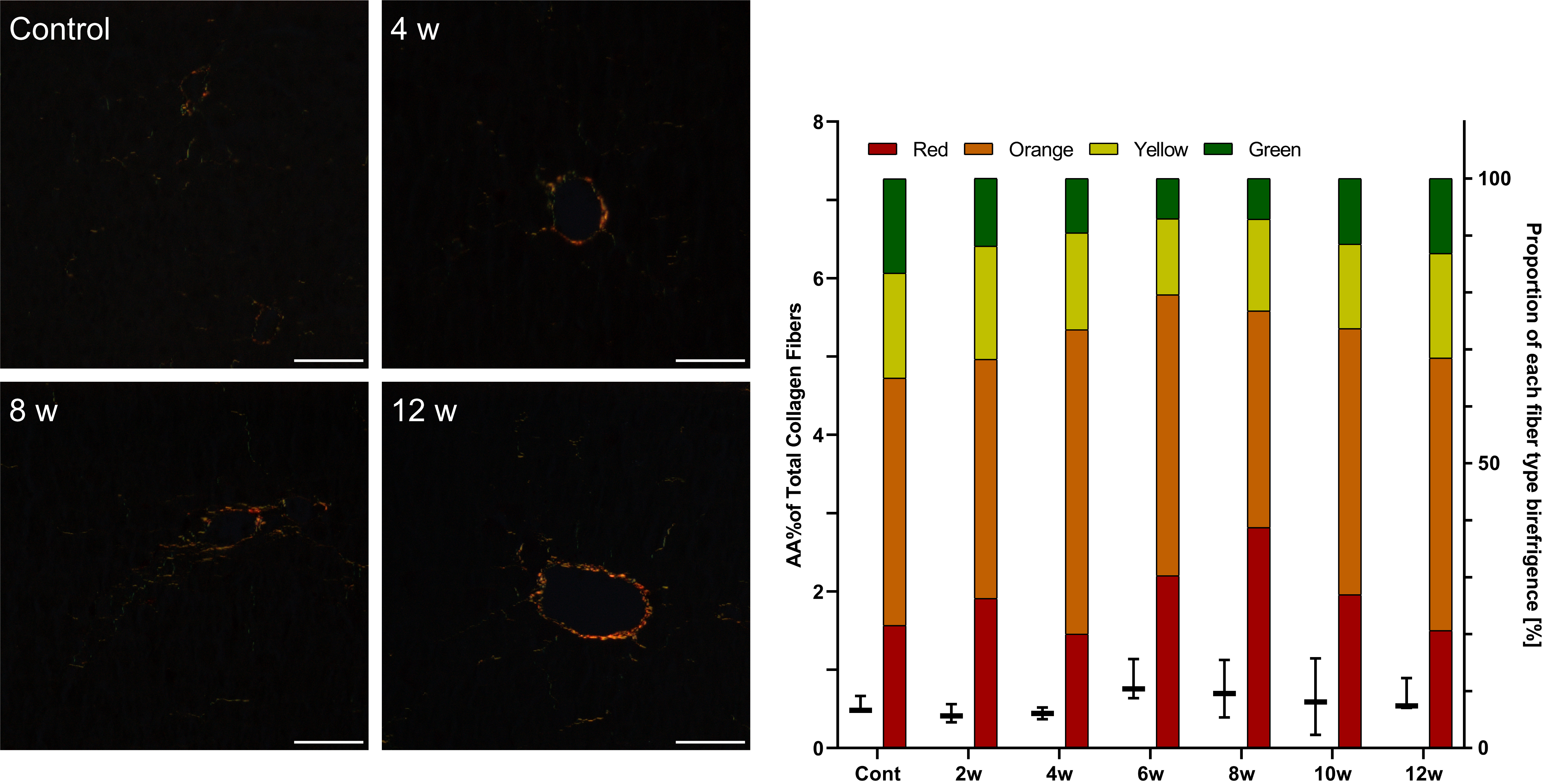

In D-GalN-treated rats, the first collagen depositions were observed at week 4. Polarizing microscopy showed fibrous expansion from some portal and pericentral areas and short septa corresponding to Ishak score 1 but no increased collagen area. After 8 weeks of intoxication, we noted moderate fibrosis with collagen deposition and an increasing number of thick red fibers (Table 5, Fig. 4).

Fig. 4.

Fig. 4.Assessment of fibrosis in the livers of rats after repeated

D-GalN injections. Sirius red staining under polarized light.

Mag. 200

In D-GalN-treated mice, minor liver fibrosis began at week 10. The semi-quantitative scale showed early fibrosis without a significant increase in collagen deposition at any time point (Table 5, Fig. 5).

Fig. 5.

Fig. 5.Assessment of fibrosis in the livers of mice after repeated

D-GalN injections. Sirius red staining under polarized light. Mag.

200

The onset of the different stages of liver fibrosis in the studied models is

presented in Table 6. At week 12 of CCl

| First sign of liver fibrosis | Early fibrosis | Established fibrosis | Incomplete cirrhosis | |

| CCl |

- | 2nd week | 6th week | 12th week |

| CCl |

- | 2nd week | 6th week | - |

| GalN rats | 4th week | 8th week | - | - |

| GalN mice | 10th week | - | - | - |

| The criteria for each stage of liver fibrosis were as follow: first sign of liver fibrosis (Ishak score 0–1 and no increased in the area of collagen fibers); early fibrosis (Ishak score 2–3 or increased in the area of collagen fibers); established fibrosis (Ishak score 4 and increased in the area of collagen fibers); and incomplete cirrhosis (Ishak score 5 and increased in the area of collagen fibers). | ||||

To summarize the stages of liver fibrosis in both experimental models, we found

that in CCl

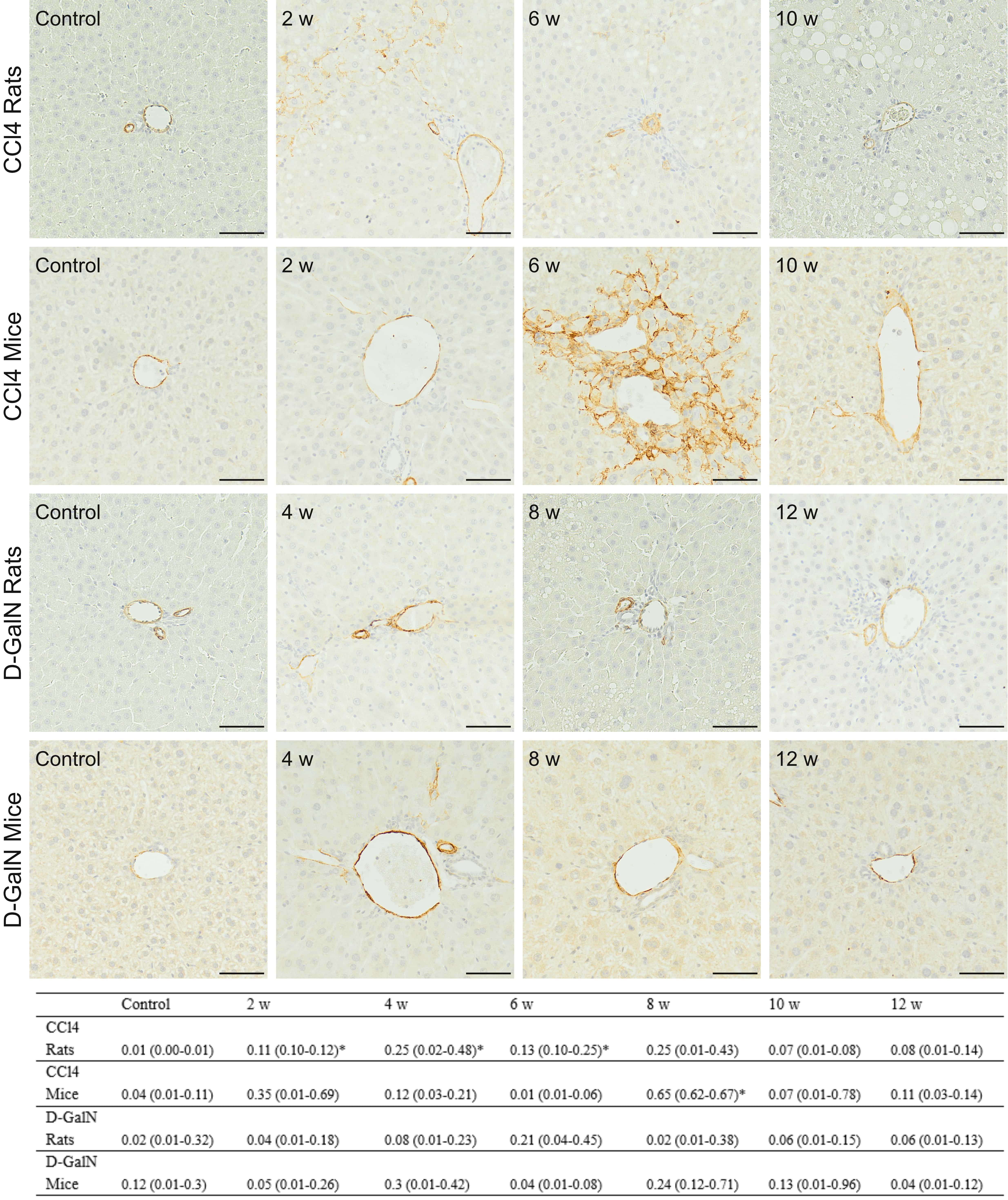

After repeated CCl

Fig. 6.

Fig. 6.Immunodetection of

The results indicated the stronger hepatic stellate cells activation in

CCl

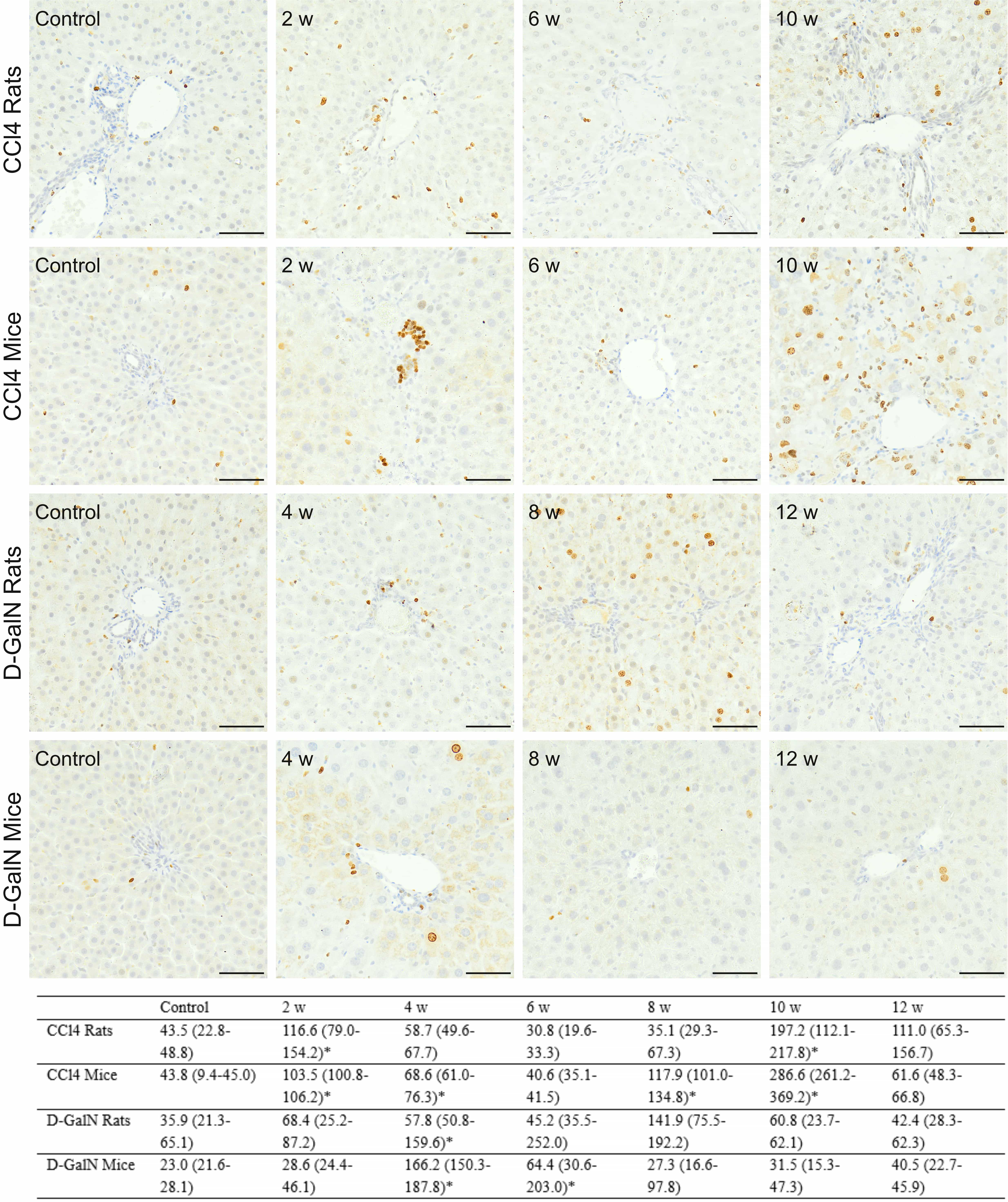

Rats repeatedly injected with CCl

Fig. 7.

Fig. 7.Immunodetection of Ki67

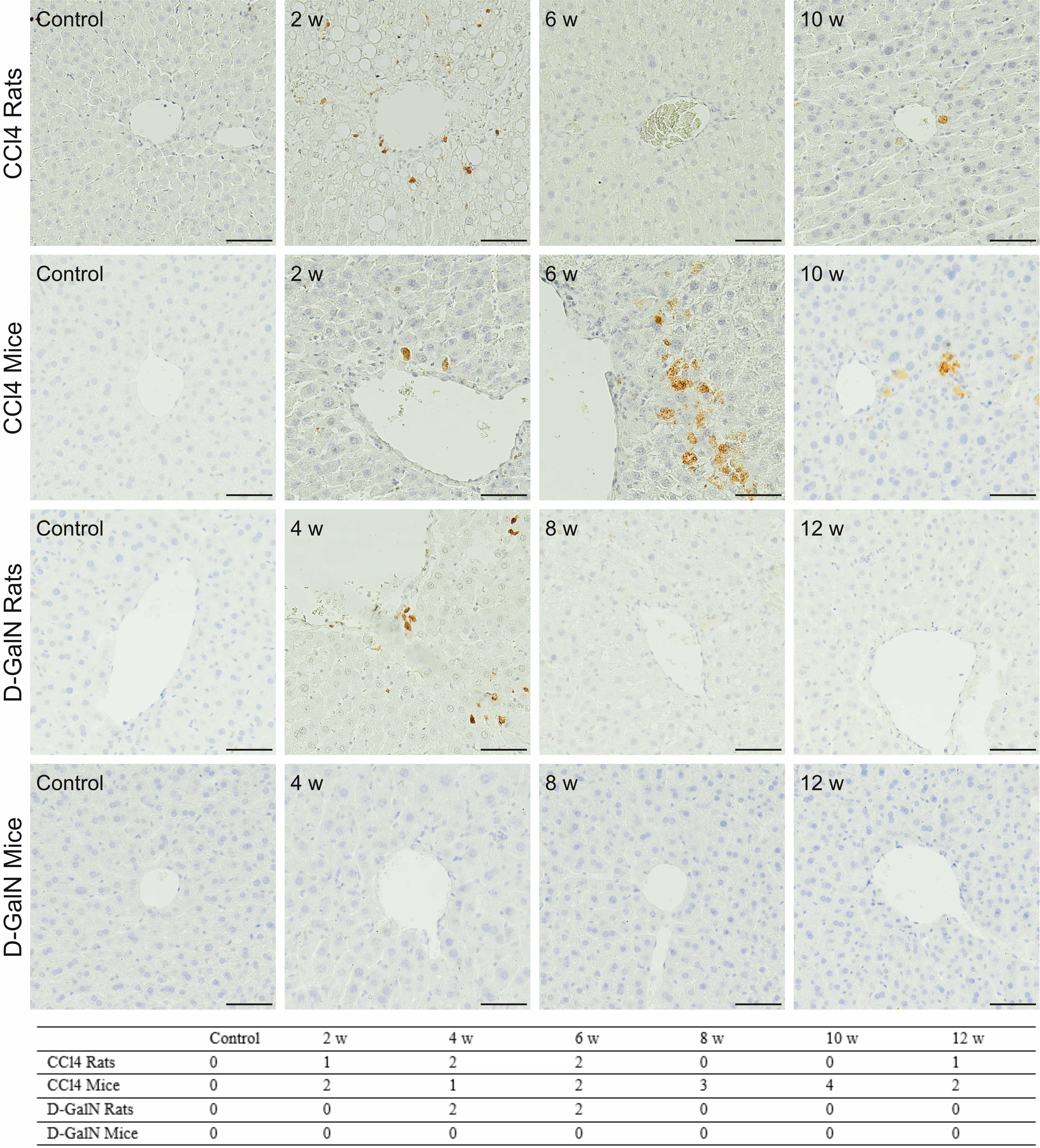

Minimal and moderate numbers of Cas3

Fig. 8.

Fig. 8.Immunodetection of Cas-3

The results indicated the coincidence of changes in apoptotic and proliferative

activities in livers, especially of CCl

We observed very low expression of Gadd45a, COL1A1,

IL-6, and TNF

Gene expression of COL3A1 in CCl

| Time point | COL3A1 | CYP2E1 | PPAR | c-Met | HGF |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Carbon Tetrachloride Rats | |||||

| Control | 0.103 (0.067–0.263) | 1.974 (1.381–3.826) | 0.178 (0.081–0.231) | 0.079 (0.013–0.132) | 0.048 (0.038–0.100) |

| 2 w | 0.180 (0.121–0.233) | 1.069 (0.782–2.372)* | 0.125 (0.104–0.152) | 0.103 (0.007–0.155) | 0.021 (0.016–0.026)* |

| 4 w | 0.028 (0.013–0.242) | 2.021 (1.564–2.151) | 0.376 (0.143–0.690) | 0.051 (0.015–0.094) | 0.036 (0.011–0.052) |

| 6 w | 0.120 (0.018–0.327) | 0.657 (0.255–1.590)* | 0.103 (0.032–0.143) | 0.039 (0.020–0.128) | 0.063 (0.029–0.510) |

| 8 w | 0.115 (0.097–0.184) | 0.967 (0.508–1.743)* | 0.097 (0.067–0.222) | 0.066 (0.063–0.083) | 0.069 (0.037–0.128) |

| 10 w | 0.137 (0.050–0.234) | 1.454 (0.663–2.261)* | 0.314 (0.069–0.513) | 0.053 (0.012–0.066) | 0.050 (0.026–0.110) |

| 12 w | 0.146 (0.074–0.171) | 2.255 (0.744–3.846) | 0.276 (0.077–0.29) | 0.019 (0.005–0.037)* | 0.035 (0.011–0.043)* |

| Carbon Tetrachloride Mice | |||||

| Control | 0.046 (0.031–0.062) | 28.052 (19.226–34.896) | 0.771 (0.189–1.106) | 0.156 (0.106–0.309) | 0.070 (0.048–0.152) |

| 2 w | 0.397 (0.179–0.485)* | 32.391 (15.313–39.854) | 0.611 (0.397–0.691) | 0.133 (0.095–0.189) | 0.161 (0.054–0.255) |

| 4 w | 0.251 (0.172–0.312)* | 15.665 (10.438–52.482)* | 0.387 (0.233–0.743) | 0.049 (0.014–0.117)* | 0.223 (0.137–0.290)* |

| 6 w | 0.145 (0.133–0.231)* | 26.709 (26.067–35.119) | 0.660 (0.446–1.16) | 0.099 (0.090–0.155) | 0.092 (0.078–0.127) |

| 8 w | 0.300 (0.244–0.309)* | 8.253 (6.737–36.560) | 0.285 (0.126–0.883) | 0.266 (0.192–0.340) | 0.019 (0.016–0.021)* |

| 10 w | 0.388 (0.327–0.420)* | 9.302 (5.936–12.812)* | 0.149 (0.125–0.208)* | 0.097 (0.061–0.133) | 0.166 (0.071–0.268) |

| 12 w | 0.161 (0.114–0.236)* | 48.001 (37.923–70.767)* | 1.035 (0.671–2.723) | 0.097 (0.023–0.223)* | 0.077 (0.023–0.132) |

| D–Galactosamine Rats | |||||

| Control | 0.091 (0.06–0.161) | 4.766 (1.331–6.203) | 0.501 (0.308–0.617) | 0.061 (0.032–0.079) | 0.183 (0.062–0.242) |

| 2 w | 0.096 (0.062–0.124) | 3.382 (3.108–3.962) | 0.290 (0.262–0.459) | 0.029 (0.017–0.043)* | 0.093 (0.045–0.15) |

| 4 w | 0.226 (0.143–0.346)* | 8.344 (6.684–14.527)* | 0.600 (0.415–1.320) | 0.028 (0.014–0.212) | 0.160 (0.127–0.483) |

| 6 w | 0.250 (0.052–0.361)* | 12.197 (10.618–28.413)* | 1.751 (0.840–2.054)* | 0.059 (0.017–0.140) | 0.092 (0.066–0.341) |

| 8 w | 0.056 (0.025–0.089)* | 6.326 (3.227–8.282) | 0.255 (0.143–0.287)* | 0.036 (0.023–0.042)* | 0.052 (0.027–0.106)* |

| 10 w | 0.063 (0.030–0.088)* | 7.122 (1.03–16.248) | 0.369 (0.056–0.698) | 0.029 (0.016–0.059)* | 0.093 (0.088–0.098)* |

| 12 w | 0.070 (0.030–0.107) | 6.928 (5.867–10.074)* | 0.522 (0.326–0.652) | 0.028 (0.014–0.044) | 0.152 (0.078–0.276) |

| D–Galactosamine Mice | |||||

| Control | 0.052 (0.023–0.082) | 34.028 (13.817–55.267) | 1.041 (0.682–1.432) | 0.258 (0.067–0.373) | 0.167 (0.009–0.187) |

| 2 w | 0.107 (0.059–0.229)* | 77.442 (57.083–102.893)* | 0.495 (0.066–1.306) | 0.263 (0.143–0.319) | 0.179 (0.067–0.185) |

| 4 w | 0.096 (0.077–0.209)* | 89.884 (33.121–127.972)* | 0.757 (0.253–1.264) | 0.236 (0.126–0.338) | 0.032 (0.015–0.054) |

| 6 w | 0.127 (0.049–0.199)* | 58.541 (40.530–172.545) | 0.319 (0.295–1.671) | 0.115 (0.048–0.406) | 0.098 (0.032–0.255) |

| 8 w | 0.087 (0.033–0.105)* | 15.291 (12.719–26.518) | 0.994 (0.181–0.992) | 0.040 (0.038–0.060)* | 0.013 (0.002–0.160)* |

| 10 w | 0.035 (0.031–0.038) | 18.319 (12.084–26.264) | 0.235 (0.132–0.462)* | 0.080 (0.073–0.098)* | 0.024 (0.003–0.057)* |

| 12 w | 0.062 (0.053–0.110) | 41.135 (30.376–47.368) | 0.673 (0.523–0.740) | 0.108 (0.093–0.248) | 0.117 (0.092–0.368) |

| Data are presented as a median of 2 | |||||

In CCl

We observed an increase in CYP2E1 gene expression in rats between weeks

4 and 12 and a temporary increase in mice at weeks 2 and 4, both treated with

D-GalN. In rats, it was statistically significant at weeks 4, 6, and 12

(p

There were noticeable but (at most time points) not statistically significant

differences in PPAR

In D-GalN-intoxicated rats, we observed a significantly increased

PPAR

In CCl

We observed small but statistically significant decreases in HGF gene

expression in rats treated for 2 and 12 weeks with CCl

In D-GalN-treated rats and mice, we observed a decrease in HGF expression after weeks 6 and 4, respectively, followed by a return to control values at week 12.

In this study, we assessed the progression of histopathological changes in the livers of experimental animals, in the chronic liver injury model, to select the best time for potential pharmaceutical or stem cell therapy. During long-term intoxication, in response to parenchymal inflammatory reaction, stellate cells produce collagen and other extracellular matrix components. Collagen fibers enter the perisinusoidal space of Disse and, as it were, seal the permeable barrier between the sinusoids and the liver parenchyma, effectively inhibiting the flow of substances and migration of administered cells that could leave the vascular bed. It has been observed that in people without liver fibrosis, this organ is a frequent site of metastasis of malignant tumors from other organs due to the favorable hemodynamic conditions of flowing blood, permeability of the sinusoidal wall, and the small diameter of sinusoids, which favors the formation of microemboli from circulating cells. The resulting emboli retain cells within the vascular network of the organ, promoting their migration into the liver parenchyma, which would be impossible if the cells were suspended in the flowing bloodstream [38]. In contrast, metastases from distant organs are found very rarely in patients with developed cirrhosis.

Nevertheless, cirrhosis itself requires treatment which, in addition to eliminating etiological factors, involves slowing down the progression of the disease, including fibrosis, and supporting the functioning of the liver. Failures of CLD cell therapies were most likely due to unfavorable biodistribution of the administered cells caused by advanced fibrosis [39, 40]. So far, no detailed model studies have been conducted to analyze how the duration of the intoxication, and thus the degree of fibrosis, affects the biodistribution of stem cells administered for therapeutic purposes [11, 14, 41, 42, 43, 44].

Experimental models used to induce liver injury include intoxication with

CCl

D-GalN is a highly hepatospecific compound. Unlike other hepatotoxins, D-GalN does not directly damage other organs and does not cause irritation when injected. In hepatocytes, D-GalN is eliminated by the galactose metabolic pathway, including D-GalN phosphorylation to galactosamine-1-phosphate (GalN-1-P), followed by its conversion to UDP-galactosamine, which has a higher affinity for uridine diphosphate (UDP) than for galactose. The trapping effect leads to uridine deficiency, inhibition of RNA and protein synthesis, and apoptotic cell death [51].

The primary lasting effect of our intoxication procedures was the progressive

liver fibrosis. The mechanism of fibrosis in models using CCl

The data obtained by us and other research teams suggest that the onset of

fibrosis in the models using CCl

At the molecular level, the process of fibrosis is influenced by a number of

factors, and in particular depends on the expression of the genes

TGF

We observed morphological features of liver injury accompanying the fibrosis

resulted from chronic liver injury [12], where the CCl

An additional effect of liver injury in the CCl

In the liver fibrosis models using repeated injections of D-GalN (25 mg/100 g bw in rats and 75 mg/100 g in mice), we observed the slow dynamics of fibrosis progression over time. Microscopic changes were accompanied by a transient increase in COL3A1 gene expression. Similar changes, especially in mice, have been previously noted by other researchers. In the rat models using repeated injections of 25 mg/100 g D-GalN bw, the presence of early or established fibrosis was demonstrated at week 12 of intoxication [14, 62]. In order to induce irreversible cirrhosis in the rat model, the duration of the intoxication should be extended to up to 6 months [67]. In the mouse model, an attempt to induce cirrhosis with a relatively high dose of 150 mg/100 g D-GalN bw administered regularly once a week for 13 weeks failed [68]. Overall, our results and literature data suggest that the rat and mouse models of CLD using repeated D-GalN injections offer significantly less opportunity to achieve established liver fibrosis and cirrhosis within a predictable and defined period of frame.

Fibrosis observed in D-GalN-intoxicated rats was accompanied by a relatively small inflammatory reaction and weakly pronounced visible histopathological changes, such as hepatocyte edema and ballooning degeneration. In the mouse model of chronic D-GalN administration, we did not observe any significant histopathological changes. In both rat and mouse models of D-GalN-induced CLD, other researchers observed little or no damage to the liver parenchyma [14]. Also, the increase in apoptotic activity only at certain time points after intoxication in rats, lack of apoptotic activity in mice, and temporary tendency to increase in proliferative activity observed in both rats and mice indicate relatively low potential of the D-GalN doses administered chronically to induce CLD. The scant literature data indicate a small effect of repeated low-dose injections of D-GalN on the induction of apoptosis [14, 62]. Increased apoptotic activity in the liver parenchyma is much more pronounced in the acute or fulminant injury model, where a single injection of high doses of D-GalN is used [69, 70]. Nevertheless, the decrease in the expression of the HGF gene and its receptor c-Met, found in animal groups studied by us, mostly those treated with D-GalN, coincides partially with literature data, which describe an increase in HGF expression in the initial stage of chronic hepatitis and a decrease in the expression of this gene in the advanced stage of the disease [66].

It should be noted that the histopathological changes recorded in the rat and

moue livers in both intoxication models were not clearly reflected in the results

of tests carried out on the blood of the test animals. In the models using

CCl

To sum up, the used doses of hepatotoxins allowed to show subtle differences in their effects over time, while avoiding too abrupt and advanced changes without the possibility of tracing intermediate stages. We assessed the severity of reversible and irreversible structural and functional changes in the liver in individual CLD models to determine the potentially optimal time of therapeutic intervention. Such CLD models might apply to different types of pharmaceutical treatments and to stem cell therapy. However, it should be noted that stem cell therapy has much more variables that might completely render the “timing” a less important limiting factor. For instance, the type of transplanted cells, their number, the pre-treatment/pre-genetic engineering of injected cells, the route of injection, the co-transplantation of more than one cell type, and many others are very powerful limiting factors that might influence its effectiveness. Based on this preclinical study, we can expect that in experimental rodents with established fibrosis large amount of collagen fibers which seal the sinusoids barrier, might prevent implanted cells homing process.

Summarizing the results obtained in the mouse and rat models using CCl

In mice, and rats CCl

We do not recommend rodent models of D-GalN-induced liver fibrosis due to the long incubation period, poor effect, and high costs.

CCl

All data generated or analyzed during this study are included in this published article.

PC and MK designed the research study. PC supported the studies financially (grands), provided help and advice. MK, EK, ŁL, AP, AS-S, EB, BS, MH, MM, AG, JP performed the research. PC, MK, ŁL, AS-S, BS, AP analyzed the data. PC and MK wrote the manuscript. All authors contributed to editorial changes in the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Animal experiments were approved by the Animal Experiments Ethical Committee of Medical University of Silesia, Katowice, Poland (decision no. 18/2018).

We thank the Silesian Analytical Laboratory (Katowice; Poland) for performing serum biochemistry analysis and blood morphology assessment.

The studies were supported by institutional grants (SUM Katowice) no: KNW-1-103/N/8/0 and KNW-1-100/K/9/0.

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

Publisher’s Note: IMR Press stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.