1 Faculty of Chinese Medicine and State Key Laboratory of Quality Research in Chinese Medicine, Macau University of Science and Technology, 999078 Macau, China

2 Department of Cardiovascular Disease, Shenzhen Traditional Chinese Medicine Hospital, 518020 Shenzhen, Guangdong, China

3 Department of Intervention, Traditional Chinese Medicine Hospital Affiliated to Southwest Medical University, 646000 Luzhou, Sichuan, China

4 Education Evaluation and Faculty Development Center, Guangxi Medical University, 530021 Nanning, Guangxi, China

5 Department of Vascular Surgery, The Affiliated Hospital of Southwest Medical University, 646000 Luzhou, Sichuan, China

6 College of Pharmacy, Hangzhou Normal University, 310030 Hangzhou, Zhejiang, China

7 Department of Medical Oncology, The Affiliated Hospital of Hangzhou Normal University, College of Medicine, Hangzhou Normal University, 310030 Hangzhou, Zhejiang, China

8 Faculty of Health Sciences, University of Macau, Taipa, 999078 Macau, China

9 Guangdong-Hong Kong-Macao Joint Laboratory for Contaminants Exposure and Health, 510000 Guangzhou, Guangdong, China

10 Zhuhai MUST Science and Technology Research Institute, 51900 Zhuhai, Guangdong, China

†These authors contributed equally.

Academic Editors: Antonio Barbieri and Francesca Bruzzese

Abstract

Cancer has emerged as one of the world’s most concerning health problems. The progression and metastasis mechanisms of cancer are complex, including metabolic disorders, oxidative stress, inflammation, apoptosis, and intestinal microflora disorders. These pose significant challenges to our efforts to prevent and treat cancer and its metastasis. Natural drugs have a long history of use in the prevention and treatment of cancer. Many effective anti-tumor drugs, such as Paclitaxel, Vincristine, and Camptothecin, have been widely prescribed for the prevention and treatment of cancer. In recent years, a trend in the field of antitumor drug development has been to screen the active antitumor ingredients from natural drugs and conduct in-depth studies on the mechanisms of their antitumor activity. In this review, high-frequency keywords included in the literature of several common Chinese and English databases were analyzed. The results showed that five Chinese herbal medicines (Radix Salviae, Panax Ginseng C. A. Mey, Hedysarum Multijugum Maxim, Ganoderma, and Curcumaelongae Rhizoma) and three natural compounds (quercetin, luteolin, and kaempferol) were most commonly used for the prevention and treatment of cancer and cancer metastasis. The main mechanisms of action of these active compounds in tumor-related research were summarized. Finally, we found that four natural compounds (dihydrotanshinone, sclareol, isoimperatorin, and girinimbin) have recently attracted the most attention in the field of anti-cancer research. Our findings provide some inspiration for future research on natural compounds against tumors and new insights into the role and mechanisms of natural compounds in the prevention and treatment of cancer and cancer metastasis.

Keywords

- Chinese medicine

- bioactive compounds

- cancer

- tumor

- molecular mechanisms

Cancer is one of the most concerning health problems facing mankind. The progression and metastasis mechanisms of cancer are complex, including metabolic disorders, oxidative stress, inflammation, apoptosis, and intestinal microflora disorders. These pose a significant challenges to our efforts to prevent and treat cancer and its metastases. Natural drugs have a long history of use in the prevention and treatment of cancer. Many effective anti-tumor drugs, such as Paclitaxel, Vincristine, and Camptothecin, have been widely prescribed for the prevention and treatment of cancer [1]. In recent years, a trend in the field of antitumor drug development has been to screen effective and safe antitumor ingredients from natural drugs and to conduct in-depth studies on the mechanisms of their antitumor activity.

In this review, we searched Chinese and English electronic databases including the CNKI database, Wanfang Data Knowledge Service Platform, VIP Chinese Science and Technology Journal Database, PubMed Database, and Web of Science Database, for relevant studies. All research results from 2000 to the present were selected to obtain the three most commonly used Chinese herbal medicines through screening. The active compounds from the selected medicines were identified using the Traditional Chinese Medicine Systems Pharmacology Database (TCMSP) by analyzing oral bioavailability and drug similarity index. Subsequently, we searched the databases (PubMed and Web of Science) using the keywords for one of the compounds from the TCMSP and “Cancer” or “Tumor” “Carcinoma” or “Malignancy” to obtain articles published from January 2000 to the present.

Finally, we comprehensively analyzed and summarized the literature on the pharmacological effects and molecular mechanisms of these natural compounds against cancer and cancer metastasis. This article presents some new insights into the role of natural compounds in the prevention and treatment of cancer and cancer metastasis.

Common Chinese and English databases, including CNKI Database, Wanfang Data Knowledge Service Platform, VIP Chinese Science and Technology Journal Database, PubMed, and Web of Science, were searched, screening for relevant literature published in China and abroad from January 2000 to November 2021. The databases were searched using the following terms: [“traditional Chinese medicine (TCM)” OR “Chinese medicine” OR “herbal medicine” AND “cancer” OR “tumor” OR “carcinoma” OR “malignancy”]. According to the interface of each database, the comprehensive retrieval of subject words combined with keywords and free words was carried out to ensure the systematic integrity of the literature retrieval.

We searched all the basic studies on the mechanism of antitumor action of natural compounds and gathered all proven targets. To ensure the authenticity and stability of the results, only relevant studies with cell samples were selected.

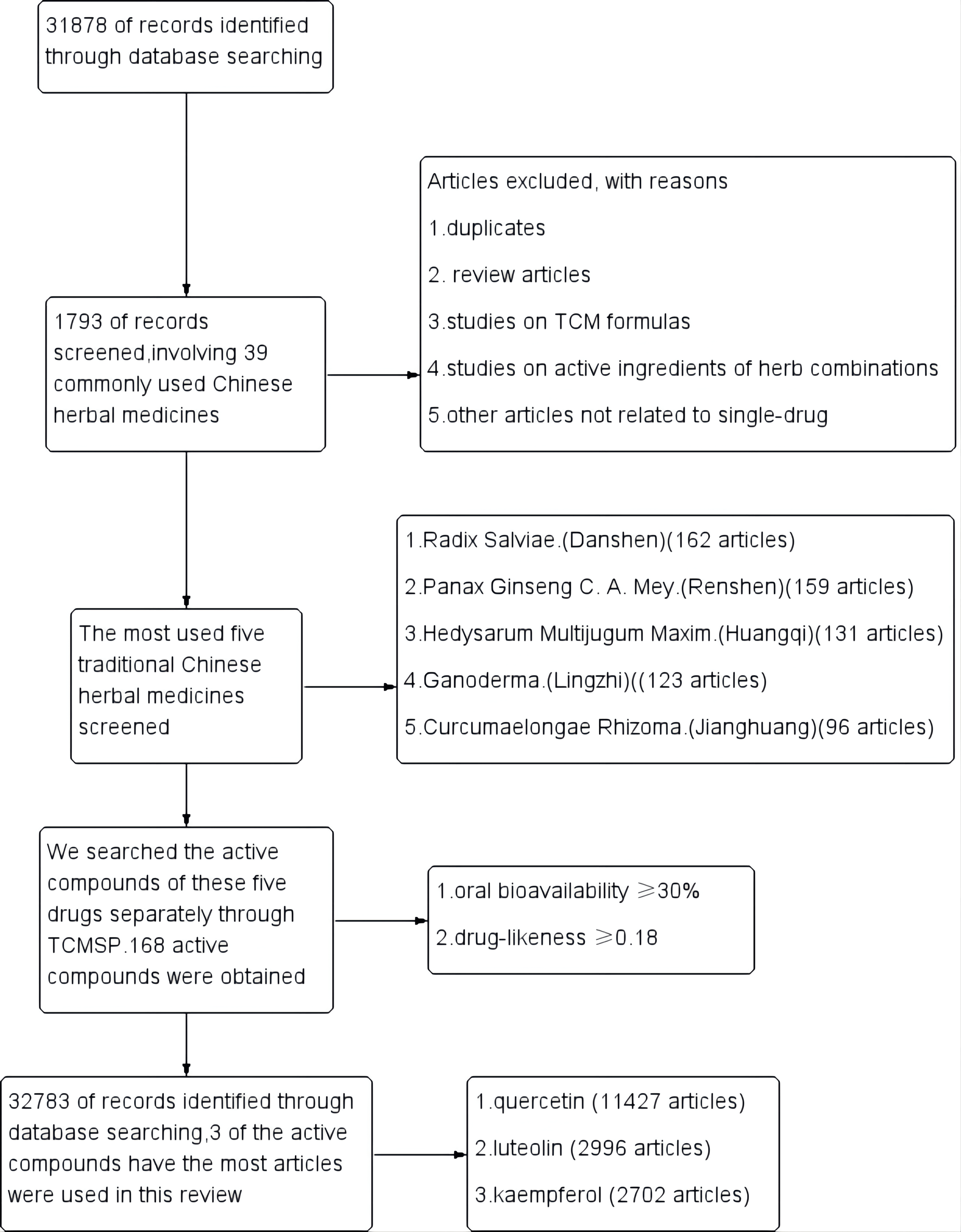

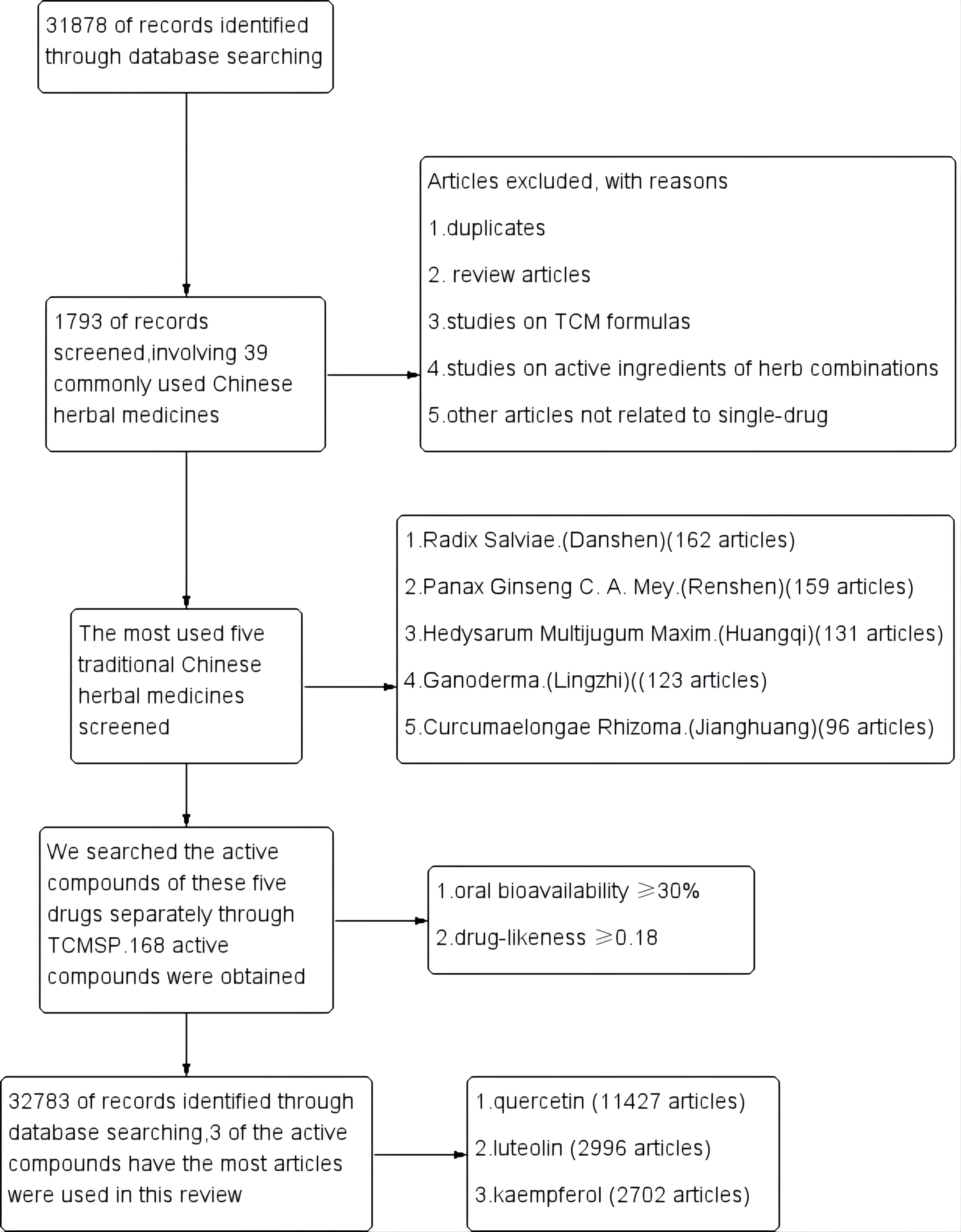

A total of 31,878 articles were retrieved, after excluding review articles,

studies on TCM formulas, active ingredients

of herb combinations, and other articles not related to a

single drug. 1793 single-drug articles were included in our study, involving 39

commonly used Chinese herbal medicines. The most commonly used five traditional

Chinese medicines were Radix Salviae (Danshen, 162 articles), Panax Ginseng C. A.

Mey (Renshen, 159 articles), Hedysarum Multijugum Maxim

(Huangqi, 131 articles), Ganoderma (Lingzhi, 123 articles) and Curcumaelongae

Rhizoma (Jianghuang, 96 articles). We then searched the active

compounds of these five drugs separately through TCMSP. The active

compounds of each herb were sorted by the screening criteria

with oral bioavailability

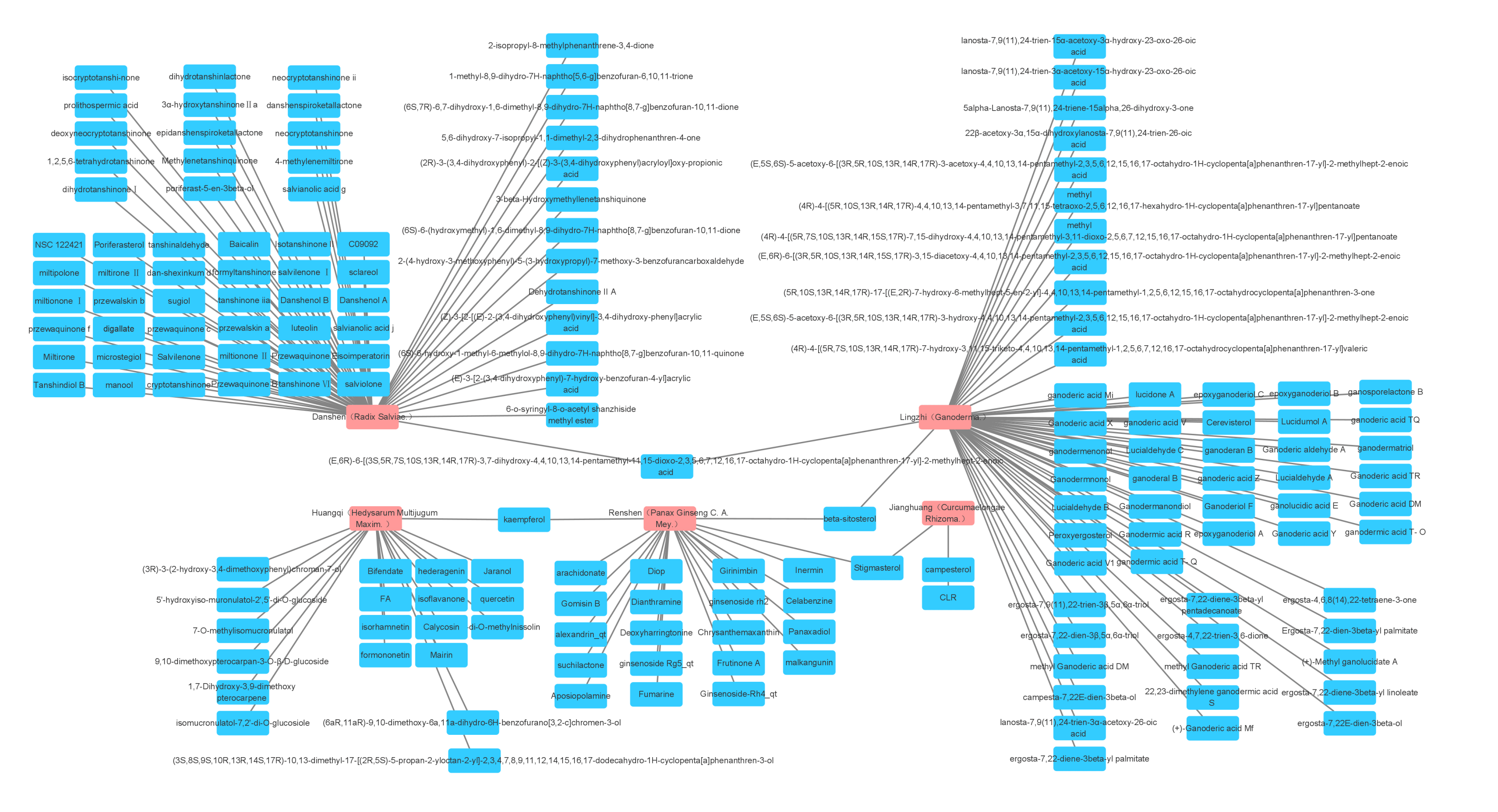

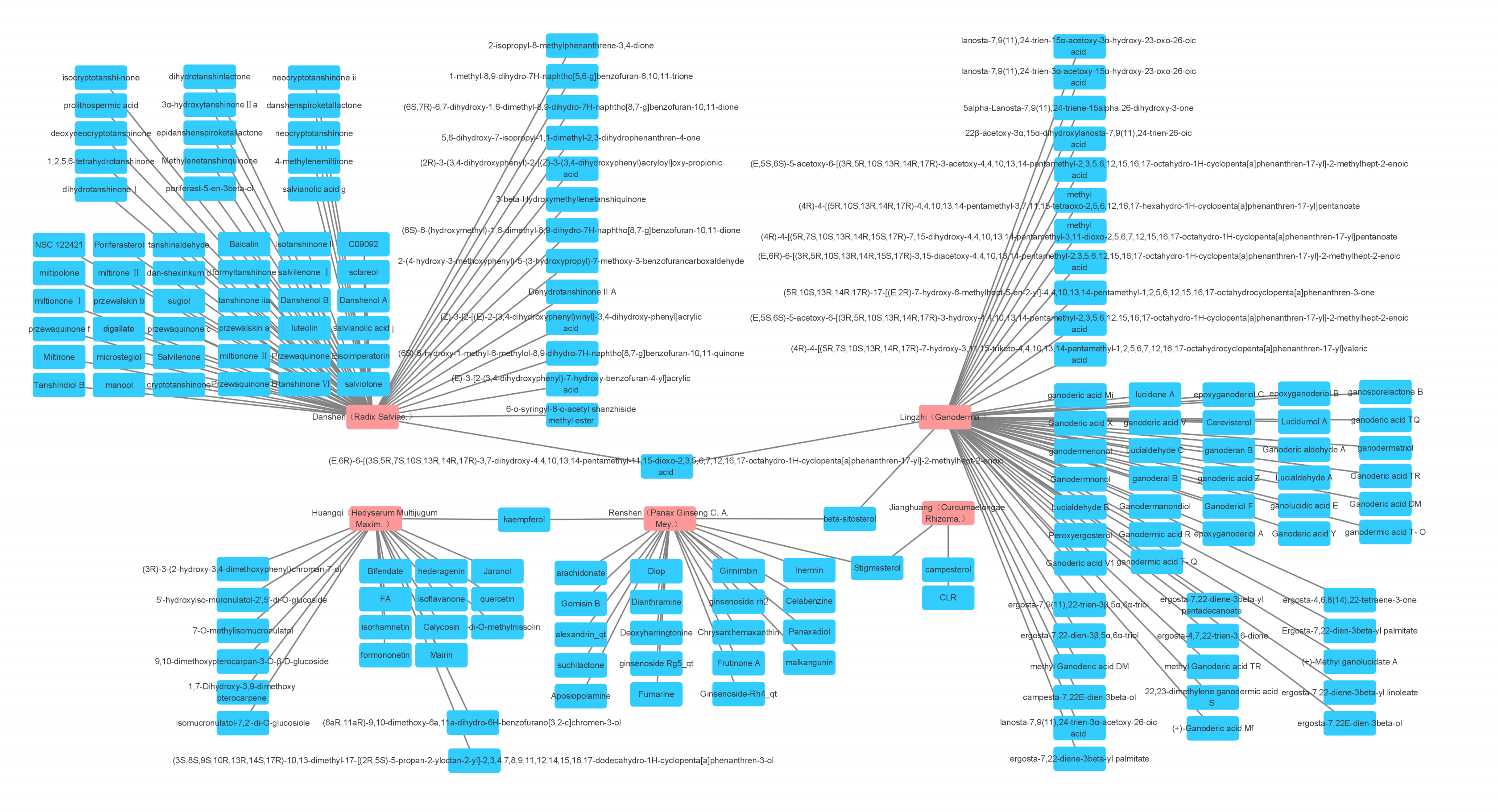

Fig. 1.

Fig. 1.The five most widely used single drugs in cancer and their active ingredients.

Fig. 2.

Fig. 2.Study flow diagram.

We summarized the reported targets of quercetin in the articles, which involving 36 different cancer cells (Table 1, Ref. [2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8, 9, 10, 11, 12, 13, 14, 15, 16, 17, 18, 19, 20, 21, 22, 23, 24, 25, 26, 27, 28, 29, 30, 31, 32, 33, 34, 35, 36, 37, 38, 39, 40, 41, 42, 43, 44, 45, 46, 47, 48, 49, 50, 51, 52, 53, 54, 55, 56, 57, 58, 59, 60, 61, 62, 63, 64, 65, 66, 67, 68, 69, 70, 71, 72, 73, 74, 75, 76, 77, 78, 79, 80, 81, 82, 83, 84, 85, 86, 87, 88, 89, 90, 91, 92, 93, 94, 95, 96, 97, 98, 99, 100, 101, 102, 103, 104, 105, 106, 107, 108, 109, 110, 111, 112, 113, 114, 115, 116, 117, 118, 119, 120, 121, 122, 123, 124, 125, 126, 127, 128, 129, 130]).

| Model cell | Reported targets |

| MDA-MB-468 | cyclin B1 [2] |

| TNF alpha, CCL28 [3] | |

| p53, Bcl2 [4] | |

| SOD, CYP1B1, CYP2, and CYP3 [5] | |

| MDA-MB-231 | Cx43 [6] |

| caspase-3, -8 and -9 [7] | |

| MMP-3 [8] | |

| alpha5- and alpha9-nAChR [9] | |

| Skp2, p27, FoxO1 [10] | |

| p53, p21, Bcl-xL, cyclin B1 [11] | |

| Skp2 [12] | |

| miR-146a, EGFR, bax, and caspase-3 [13] | |

| aldehyde dehydrogenase 1A1, C-X-C chemokine receptor type 4, mucin 1, and epithelial cell adhesion molecules [14] | |

| NF-κB , Hsp27, Hsp70 and Hsp90 [15] | |

| MCF-7 | p21CIP1/WAF1 [16] |

| PKC, ERK, AP-1 [17] | |

| p53, p57, CDK2, cyclins A and B, Bcl-2, DeltaPsi(m), caspase-6, -8 and -9 [18] | |

| AMPK, mTOR [19] | |

| AMPK, mTOR, HIF-1 [20] | |

| Bcl-2, Bax [21, 22] | |

| survivin [23] | |

| RAGE, HMGB1, NF-κB [24] | |

| PTEN, Akt [25] | |

| CyclinD1, p21, Twist, and phospho p38MAPK [26] | |

| CDK6 [27] | |

| TGF- | |

| MMP-2/-9 [29] | |

| SkBr3 | HIF-1alpha, VEGF [30] |

| A549 | Bax, Bcl-2 and caspase-3 [31] |

| SIRT1, AMPK p62, LC3-II, beclin 1, Atg5, Atg7 and Atg12 [32] | |

| TIMP-2, Akt, MAPK, | |

| Bax, Bcl2 [34, 35] | |

| PDK3 [36] | |

| aurora B [37] | |

| nm23-H1, TIMP-2, MMP-2 [38] | |

| MMP-9, TGF- | |

| Bcl2, Bax, IL-6, STAT3, NF-κB [40] | |

| p53 [41] | |

| caspase-3 [42] | |

| Bcl-2, Bcl-x, Bax, caspase-3, caspase-7 and PARP, ERK, MEK1/2, PI3k, p38, Akt [43] | |

| p53, p21, survivin [44] | |

| COX-2, iNOS [45] | |

| Hsp72 [46] | |

| Hsp27 [47] | |

| H1299 | SIRT1, AMPK, p62, LC3-II, beclin 1, Atg5, Atg7, and Atg12 [32] |

| p53, p21, survivin [44] | |

| DR5, caspase-10/3, p300 [48] | |

| H69 | Bax, Bcl-2, and caspase-3 [31] |

| HepG2 | PDK3 [36] |

| ABCC6 [49] | |

| p53, cyclin D1 [50, 51] | |

| m-TOR, Nrf-2 [52] | |

| MEK1/ERK1/2, p38 MAPK, and JNK [53] | |

| cyclin D1 [54] | |

| SHP2, IFN- | |

| Bad, Bax, Bcl-2, and Survivin [56] | |

| BAX, BCL-2 [57] | |

| miR-34a, p53, SIRT1 [58] | |

| Sp1 [59] | |

| PI3K, PKC, COX-2 and ROS, p53, and BAX [60] | |

| FASN [61] | |

| Nrf2, ARE [62] | |

| p38-MAPK, Nrf2 [63] | |

| NF-κB, COX-2 [64] | |

| P53, caspase-3, caspase-9, survivin ,and Bcl-2 [65] | |

| Nrf2, Keap1 [66] | |

| caspase-3, caspase -9, Bcl-xL, Bcl-xS, Bax, Akt, ERK [67] | |

| Huh-7 | p53, cyclin D1 [50] |

| MEK1/ERK1/2, p38 MAPK, and JNK [53] | |

| SHP2, IFN- | |

| BAX, BCL-2 [57] | |

| HeLa | Hsp72 [46] |

| Hsp27 [47] | |

| MMP2, ezrin, METTL3, and P-Gp [68] | |

| Bax, Bcl-2, Cyclin D1, Caspase-3, GRP78, CHOP IRE1, p-Perk, and c-ATF6 [69] | |

| DNMTs, HDACs, HAT, HMTs and TSGs [70] | |

| LC3-I/II, Beclin 1, active caspase-3, and S6K1 [71] | |

| Rac1 [72] | |

| ROS, cytochrome-c, bcl-2, Bax, PI3K, and p-Akt [73] | |

| HPA [74] | |

| AKT, Bcl-2, p53 and caspase-3 [75] | |

| Bcl-2, Bcl-xL, Mcl1, Bax, Bad, p-Bad, cytochrome C, Apaf-1, caspases, surviving, p53, p21, cyclin D1, p50, p65, IκB, p-IκB- | |

| AMPK, ACC, AICAR, HSP70, caspase 3, PP2a and SHP-2 [77] | |

| Caski | HPA [74] |

| SiHa | MMP2, ezrin, METTL3 and P-Gp [68] |

| Hep-2 | Hsp72 [46] |

| Hsp27 [47] | |

| TFK-1 | BAX, BCL-2 [57] |

| LNCaP | PI3K, Akt [79] |

| Bcl-2, VEGF, Akt, PI3K [80] | |

| Bax, Bcl-2, caspase-3, AKT, VEGF [81] | |

| PI3K, Akt, AR [82] | |

| HSP27 [83] | |

| Bcl-2, Bax [84] | |

| PARP, Bad, Bcl-xL, Bax, procaspases-3, -8 and -9 [85] | |

| HIF-1 alpha, VEGF [30] | |

| caspase, PARP, IAP and Bcl-2 [86] | |

| Sp1, AR [87] | |

| AR, PSA, NKX3.1, ODC,, and hK2 [88] | |

| hsp70 [89] | |

| PC-3 | Bcl-2, VEGF, Akt, PI3K [80] |

| Bax, Bcl-2, caspase-3, AKT, VEGF [81] | |

| Cyclin D1, ErbB-2, ErbB-3, c-Raf, MAPK kinase 1/2 (MEK1/2), MAPK, Elk-1, and Akt-1 [90] | |

| hsp70 [89] | |

| LC3, Beclin-1, PI3K, Akt, mTOR, LC3-II, LC3-I [91] | |

| PI3K, Akt [92] | |

| P53, PI3K, AKT, MMP-2, and MMP-9 [93] | |

| TSP-1 [94] | |

| TGF- | |

| ATF, GRP78, GADD153, CDK2, cyclins E and D, Bcl-2, Bax, caspase-3, -8, and -9 [96] | |

| N-cadherin, vimentin, E-cadherin, Snail, Slug, Twist, EGFR, PI3K, Akt, ERK 1/2 [97] | |

| uPA, uPAR, EGF, EGF-R, | |

| Bad, IGFBP-3, cytochrome C, caspase-9, caspase-10, PARP, caspase-3, IGF-IR | |

| PLC, PKC, and MEK1/2 [101] | |

| Bcl-2, Bcl-x(L), and Bax [102] | |

| MMP-2 and MMP-9 [103] | |

| Cdc2/Cdk-1, cyclin B1, cyclin A, p21/Cip1, pRb, pRb2/p130, Bcl-2, Bcl-X(L), Bax, and caspase-3 [104] | |

| HSP72 [105] | |

| LAPC-4 | PI3K, Akt, miR-21, miR-19b, miR-148a, AR [82] |

| RWPE-1 | HSP27 [83] |

| TSU-Pr1 | HSP27 [83] |

| DU-145 | caspase, PARP, IAP , and Bcl-2 [86] |

| HSP72 [105] | |

| DR 5, PARP, caspase-3, and caspase-9 [106] | |

| JCA-1 | hsp70 [89] |

| SW480 | AIF and Caspase-3 [107] |

| TGF- | |

| cyclin D(1) and survivin [109] | |

| beta-catenin and Tcf-4 [110] | |

| ErbB2, ErbB3, Akt, Bax , and Bcl-2 [111] | |

| HT-29 | ErbB2, ErbB3, Akt, Bax, and Bcl-2 [111] |

| Bcl-2, mTOR, Akt, p53, Bax, p38 MAPK, and PTEN [112] | |

| Akt, CSN6, Myc, p53, Bcl‑2, and Bax [113] | |

| ROS, AMPK, p38, and sestrin 2 [114] | |

| GSTA1, GSTM1, GSTP1, GSTT1, and UGT1 [115] | |

| AMPK, p53, and p21 [116] | |

| AMPK, COX-2 [117] | |

| Caco-2 | GSTA1, GSTM1, GSTP1, GSTT1, and UGT1 [115] |

| TNF- | |

| NF-κB, Bax, and Bcl-2 [119] | |

| hOGG1 [120] | |

| CDC6, CDK4, cyclin D1, beta-catenin, TCF and MAPK [121] | |

| Ki67 [122] | |

| SW-620 | NF-κB, Bax and Bcl-2 [119] |

| HuTu 80 | GSTA1, GSTM1, GSTP1, GSTT1 and UGT1 [115] |

| Ki67 [122] | |

| CX-1 | HIF-1alpha, VEGF [30] |

| Eca109 | VEGF-A, MMP9 and MMP2 [123] |

| NF-κB, pIκB | |

| EC9706 | NF-κB, pIκB |

| KYSE-510 | miR-1-3p, TAGLN2 [125] |

| TE-7 | miR-1-3p, TAGLN2 [125] |

| SKMEL-103 | AKT, AXL, PIM-1, ABLK, HSP90, HSP70, and GAPDH [126] |

| SKMEL-28 | AKT, AXL, PIM-1, ABLK, HSP90, HSP70, and GAPDH [126] |

| PANC-1 | c-Myc, TGF- |

| STAT3, EMT, and MMP [128] | |

| Grp78/Bip, p-PERK, PERK, ATF4, ATF6, and GADD153/CHOP [129] | |

| Patu8988 | c-Myc, TGF- |

| STAT3, EMT, and MMP [128] | |

| BGC823 | uPAR, NF-κb, PKC, and ERK1/2 [130] |

In breast cancer, the action of quercetin involves modulating SOD enzyme activity, the selective inhibition of CYP1B1, CYP2, and CYP3 family of enzymes, G2/M arrest, and apoptosis [5]. A study on human breast cancer showed that quercetin triggered cell death of MDA-MB-231 cells via mitochondrial- and caspase-3-dependent pathways [7]. In studies on MCF-7 cells, quercetin not only induced cell cycle arrest but also induced significant apoptosis; the induction of apoptosis could be blocked by antisense p21 CIP1/WAF1 expression [16]. Quercetin regulated MCF-7 cell apoptosis through the AMPK-mTOR signaling pathway [19] and promoted apoptosis by inducing G0/G1 phase arrest [23].

In lung cancer, quercetin induced autophagy and apoptosis in lung cancer cells

through the SIRT1/AMPK signaling pathway [32]. Quercetin also inhibited

the metastasis of lung cancer by modulating the Akt/MAPK signaling

pathway and reduced the nuclear translocation of

In liver cancer, quercetin could enhance the effect of

interferon-

In cervical cancer, quercetin reactivation suppressed genes associated with cervical cancer by modulating epigenetic marks [70]. At the same time, quercetin induced apoptosis via the PI3k/Akt pathway [73], leading to the accumulation of ROS and upregulation of apoptosis of cervical cancer cells [75]. Quercetin suppressed the viability of cervical cancer cells in a dose-dependent manner [76].

In prostatic cancer, the combined use of metformin and quercetin exerted significant anticancer effects through the VEGF/Akt/PI3K pathway [80]. Quercetin increased the heat-induced prostatic cancer cell toxicity, possibly related to hsp70 [89]. Quercetin directly activated the caspase via the mitochondrial pathway, leading to apoptosis in prostate cancer cells [96].

In colon cancer, the anticancer effect of quercetin on colon cancer cells was associated with the down-regulation of survivin and cyclin D(1) expression [109]. The anticancer effect of quercetin was also correlated with the Akt and ErbB2/ErbB3 signaling pathways [111]. Quercetin induced apoptosis via the Akt-CSN6-Myc signaling axis in colon cancer cells [113].

In esophageal cancer, quercetin reduced the invasion and proliferation of esophageal cancer cells, which is related to MMP9, MMP2, and VEGF-A [123]. Meanwhile, inhibition of miR-1-3p could reduce the anticancer effect of quercetin, resulting in the restoration of esophageal cancer cell proliferation [125].

In pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma, quercetin inhibited tumor cell

proliferation and induced tumor cell apoptosis, which is associated with the

SHH and TGF-

We summarized the reported targets of luteolin in the articles, which involving 24 different cancer cells (Table 2, Ref. [131, 132, 133, 134, 135, 136, 137, 138, 139, 140, 141, 142, 143, 144, 145, 146, 147, 148, 149, 150, 151, 152, 153, 154, 155, 156, 157, 158, 159, 160, 161, 162, 163, 164, 165, 166, 167, 168, 169, 170, 171, 172, 173, 174, 175, 176, 177, 178, 179, 180, 181, 182, 183, 184, 185, 186]).

| Model cell | Reported targets |

| H929 | isoQC, CD47 and SIRP |

| H1975 | cyclin D1, caspase-3, Ki-67, p-LIMK and p-cofilin [132] |

| JNK, DR5, Drp1 [133] | |

| H1650 | cyclin D1, caspase-3, Ki-67, p-LIMK and p-cofilin [132] |

| A549 | JNK, DR5, Drp1 [133] |

| pFAK, pSrc, Rac1, Cdc42, RhoA [134] | |

| AIM2, caspase-1 and IL-1 | |

| p-PDK1 [136] | |

| miR-34a-5p, Bcl-2, MDM4, p53, p21, Bax, caspase-3 and caspase-9 [137] | |

| MEK, ERK, c-Fos , PI3K, Akt, NF-κB [138] | |

| Tyro3, Axl and MerTK [139] | |

| caspases-3 and -9, Bcl-2, Bax, MEK, ERK, Akt [140] | |

| Nrf2 [141, 142] | |

| E-cadherin, TGF- | |

| TRAIL [144] | |

| JNK, Bax, pro caspase-9, caspase-3, TNF | |

| H460 | AIM2, caspase-1 and IL-1 |

| miR-34a-5p, Bcl-2, MDM4, p53, p21, Bax, caspase-3 and caspase-9 [137] | |

| Axl and Tyro3 [139] | |

| Bad, Bcl‑2, Bax, caspase‑3 and Sirt1 [146] | |

| Bcl‑2, caspase‑3, ‑8, and ‑9, MAPK and ROS [147] | |

| Beclin-1, LC3II [148] | |

| H1299 | Bcl‑2, caspase‑3, ‑8, and ‑9, MAPK and ROS [147] |

| LNM35 | caspase-3 and -7 [149] |

| HeLa | TRAIL [144] |

| APAF1, BAX, BAD, BID, BOK, BAK1, TRADD, FADD, FAS, Caspases 3 and 9, NAIP, MCL-1, BCL-2, CCND1, 2 and 3, CCNE2, CDKN1A, CDKN2B, CDK4, and CDK2, TRAILR2/DR5, TRAILR1/DR4, Fas/TNFRSF6/CD95, TNFR1/TNFRSF1A, and Cytochrome C, HIF1 | |

| PKA, Jak1, Tyk2, STAT1/2, SHP-2 [151] | |

| E6, E7, pRb, p53, E2F5, Fas/FasL, DR5/TRAIL, FADD, caspase-3, caspase-8, Bcl-2, and Bcl-xL [152] | |

| caspase-8, caspase-3, XIAP, PKC [153] | |

| TNF | |

| AGS | Bcl-2, Cdc2, Cyclin B1, Cdc25C Caspase-3, Caspase-6, Caspase-9, Bax, and p53 [155] |

| CRL-1739 | MUC1, ADAM-17, IL-8, IL-10 and NF-κB. [156] |

| SGC-7901 | FOXO1 [157] |

| cMet, MMP9, Ki-67, caspase-3, PARP-1, Akt and ERK [158] | |

| VEGF, HIF-1 alpha, Bcl-2, PGE2, caspase-3 and -9 [159] | |

| Hs-746T | VEGF, Notch1 [160] |

| BGC-823 | Bax, Bcl-2, MAPK, pi3k, caspase-3, caspase-9 and cytochrome c [161] |

| VEGF-A and MMP-9 [162] | |

| MKN45 | cMet, MMP9, Ki-67, caspase-3, PARP-1, Akt and ERK [158] |

| MCF-7 | caspase-3, caspase -8, caspase -9, Bcl-2, Bax, miR-16, miR-21 and miR-34a [163] |

| Bax, Bcl-2, Caspase-3, EMT, Vimentin, Zeb1, N-cadherin, E-cadherin, miR-203 [164] | |

| Sp1, NF-κB, DNMT1 and OPCML [165] | |

| EGFR, PI3K, Akt, MAPK, Erk 1/2, STAT3 [166] | |

| Bcl-2, ROS [167] | |

| DR5, caspase-8/-9/-3, PARP, cytochrome c, Bax, Bcl-2 [168] | |

| Bcl-2, Bcl-2, AEG-1 and MMP-2 [169] | |

| Er | |

| GTF2H2, NCOR1, TAF9, NRAS, NRIP1, POLR2A, DDX5, NCOA3, CCNA2, PCNA, CDKN1A, CCND1, PLK1 [171] | |

| caspase-3 and -7 [149] | |

| MDA-MB-453 | Bax, Bcl-2, Caspase-3, EMT, Vimentin, Zeb1, N-cadherin, E-cadherin, miR-203 [164] |

| BT474 | Sp1, NF-κB, DNMT1 and OPCML [165] |

| MDA-MB-231 | EGFR, PI3K, Akt, MAPK, Erk 1/2, STAT3 [166] |

| caspase-3 and -7 [149] | |

| OPCML [172] | |

| hTERT, NF-κB, c-Myc [173] | |

| VEGF [174] | |

| Notch-1 [175] | |

| caspase-8, caspase-3, Fas, STAT3 [176] | |

| AKT, PLK1, cyclin B(1), cyclin A, CDC2, CDK2, Bcl-xL and Bax [177] | |

| MDA-MB-435 | VEGF [174] |

| SW620 | LC3B-I/II, Atg5, Bcl-2, Bax, caspase-3, PARP, ERK1/2, FOXO3a [178] |

| HCT116 | p53 [179] |

| Nrf2, ARE, DNMTs, HDACs [180] | |

| HT29 | caspase-8, caspase-3, XIAP, PKC [153] |

| caspase-3 and -7 [149] | |

| Nrf2, ARE, DNMTs, HDACs [180] | |

| HepG2 | PKA, Jak1, Tyk2, STAT1/2, SHP-2 [151] |

| caspase-8, caspase-3, XIAP, PKC [153] | |

| caspase-3 and -7 [149] | |

| p21, p53 [181] | |

| USP47, p62 [182] | |

| AMPK, NF-κB, ROS [183, 186] | |

| HGF, ERK1/2, Akt, JNK1/2, MEK, PI3K [184] | |

| p53, CDK, p21 [185] | |

| CNE1 | caspase-8, caspase-3, XIAP, PKC [153] |

In lung cancer, luteolin reduced the invasive ability of lung cancer cells, which is associated with Src/FAK-related targets [134]. Luteolin demonstrated antitumor effects through the MEK-ERK pathway [140] and reduced cell invasion via Sirt1-mediated apoptosis [146].

In cervical cancer, the expression of some proapoptotic genes, such as FAS, BOK, BAK1, BAD, BAX, FADD, TRADD, and Caspases 9 and 3, was increased by luteolin treatment. At the same time, it was also found that the expression of some anti-apoptotic genes, such as NAIP, MCL-1, and BCL-2, was significantly reduced. These results confirm that luteolin has strong anti-proliferative and pro-apoptotic effects, and this function is likely to be achieved by inhibiting AKT and MAPK pathways [150].

In gastric cancer, luteolin could reduce the proliferative capacity of gastric cancer cells by reducing VEGF production [160]. Luteolin could also cause cell death through the MAPK and PI3K pathways [161].

In breast cancer, luteolin reduced breast cancer cell proliferation and induced breast cancer cell apoptosis in two different breast cancer cell studies [165]. The antitumor effect of luteolin is related to the STAT3, MAPK, and PI3K signaling pathways [166]. The inhibitory effect of luteolin on breast cancer cell invasion might be related to the reduction of VEGF production [174].

In colon cancer, alterations in the protein levels and enzymatic activities of HDACs and DNMTs were also found in luteolin-treated colon cancer cells [180].

In liver cancer, luteolin affected the AMPK-NF-

We summarized the reported targets of kaempferol in the articles, which involving 25 different cancer cells (Table 3, Ref. [187, 188, 189, 190, 191, 192, 193, 194, 195, 196, 197, 198, 199, 200, 201, 202, 203, 204, 205, 206, 207, 208, 209, 210, 211, 212, 213]).

| Model cell | Reported targets |

| A549 | ROS, Nrf2, NQO1, HO1, AKR1C1 and GST [187] |

| miR-340, PTEN, PI3K, AKT [188] | |

| ROS, SOD, GPx, CAT [189] | |

| TGF- | |

| NCIH460 | ROS, Nrf2, NQO1, HO1, AKR1C1 and GST [187] |

| MCF-7 | ROS, SOD, GPx, CAT [189] |

| ER, PR, HER2, RhoA, and Rac1 [191] | |

| IRS-1, AKT, MEK1/2 [192] | |

| ER, E2 [193] | |

| MDA-MB-231 | ER, PR, HER2, RhoA, and Rac1 [191] |

| AP-1, MAPK, PKCδ, MMP-9 [195] | |

| CYP1A1, CYP1B1, AHR, ER | |

| BT474 | |

| SK-BR-3 | ER, PR, HER2, RhoA, and Rac1 [191] |

| BT-549 | CYP1A1, CYP1B1, AHR, ER |

| AGS | bcl-2, PARP, caspase 3, caspase 9, LC3-I, LC3-II, |

| SGC-7901 | ROS, SOD, GPx, CAT [189] |

| SNU-216 | cyclin D1, bcl-2, bax, caspase 3, caspase 9, autophagy-related gene 7, LC3-I, LC3-II, Beclin 1, p62, MAPK, ERK, PI3K, miR-181a [198] |

| bcl-2, PARP, caspase 3, caspase 9, LC3-I, LC3-II, | |

| MKN28 | cyclin B1, Cdk1 and Cdc25C, Bcl-2, Bax, caspase-3 and -9, PARP, p-Akt, p-ERK, and COX-2 [199] |

| MKN-74 | bcl-2, PARP, caspase 3, caspase 9, LC3-I, LC3-II, |

| NCI-N87 | bcl-2, PARP, caspase 3, caspase 9, LC3-I, LC3-II, |

| NUGC-3 | bcl-2, PARP, caspase 3, caspase 9, LC3-I, LC3-II, |

| SGC7901 | cyclin B1, Cdk1 and Cdc25C, Bcl-2, Bax, caspase-3 and -9, PARP, p-Akt, p-ERK, and COX-2 [199] |

| Hela | ROS, SOD, GPx, CAT [189] |

| PI3K, AKT, and hTERT [200] | |

| A2780 | GRP78, PERK, ATF6, IRE-1, LC3II, beclin 1, and caspase 4 [201] |

| Chk2, Cdc25C, Cdc2 [202] | |

| Bcl-x(L), p53, Bad, and Bax [203] | |

| CP70 | Bcl-x(L), p53, Bad, and Bax [203] |

| HCT116 | hnRNPA1, PTBP1, miR-339-5p [204] |

| AP-1 [205] | |

| PARP, caspase-8, caspase-9, caspase-3, phospho-p38 MAPK, p53, and p21 [206] | |

| caspase-3, Bcl-2, PUMA, ATM, and H2AX [207] | |

| LS174-R | ROS, JAK, STAT3, MAPK, PI3K, AKT, and NF-κB [208] |

| DLD1 | hnRNPA1, PTBP1, miR-339-5p [204] |

| HT29 | AP-1 [205] |

| IGF-II, IGF-IR, ErbB3, Akt, and ERK-1/2 [209] | |

| CDK2, CDK4, cyclins D1, cyclin E, and cyclin A [210] | |

| HCT15 | hnRNPA1, PTBP1, miR-339-5p [204] |

| AP-1 [205] | |

| PARP, caspase-8, caspase-9, caspase-3, phospho-p38 MAPK, p53, and p21 [206] | |

| SW480 | DR5 [211] |

| HepG2 | AKT, caspase-9, caspase-7, caspase-3, and PARP [212] |

| miR-21, PTEN, PI3K, AKT, mTOR [213] |

In lung cancer, kaempferol promoted the apoptosis of lung cancer cells by inhibiting Nrf2 [187]. Kaempferol exerted antitumor effects through the PTEN, miR-340 and PI3K/AKT pathways, thus inhibiting the growth of lung cancer cells and inducing the death of lung cancer cells [188].

In breast cancer, kaempferol reduced the invasive effect of breast cancer cells in both MCF-7 cells and MDA-MB-231 cells, which might be related to the activation of Rac1 and RhoA [191]. At the same time, some studies have shown that the antitumor effect of kaempferol is independent of the ER-dependent pathway [193]. Kaempferol could block the signaling pathways related to MMP-9, thus affecting the expression of MMP-9 to reduce the migration ability of breast cancer cells [195].

In gastric cancer, kaempferol could induce gastric cancer cell apoptosis by affecting the JNK-CHOP signaling pathway [197]. A study found that the expression of miR-181a increased in gastric cancer cells treated with kaempferol. This may be one of the mechanisms of kaempferol’s antitumor effect [198].

In cervical cancer, kaempferol promoted cervical cancer cell death by affecting the hTERT and PI3K/AKT pathways [200]. Kaempferol had an obvious regulatory effect on ovarian cancer cell apoptosis, indicating that kaempferol has the potential to be a promising drug for ovarian cancer [203].

In colon cancer, kaempferol could reduce ROS production and affect NF-

In liver cancer, kaempferol reduced AKT phosphorylation in human liver cancer cells and has been shown to affect PARP, caspase-3, caspase-7, and caspase-9 [212]. Studies have also shown that kaempferol can significantly affect the invasion and growth of liver cancer cells; this process may be related to PTEN and miR-21, as well as the PI3K pathway [213].

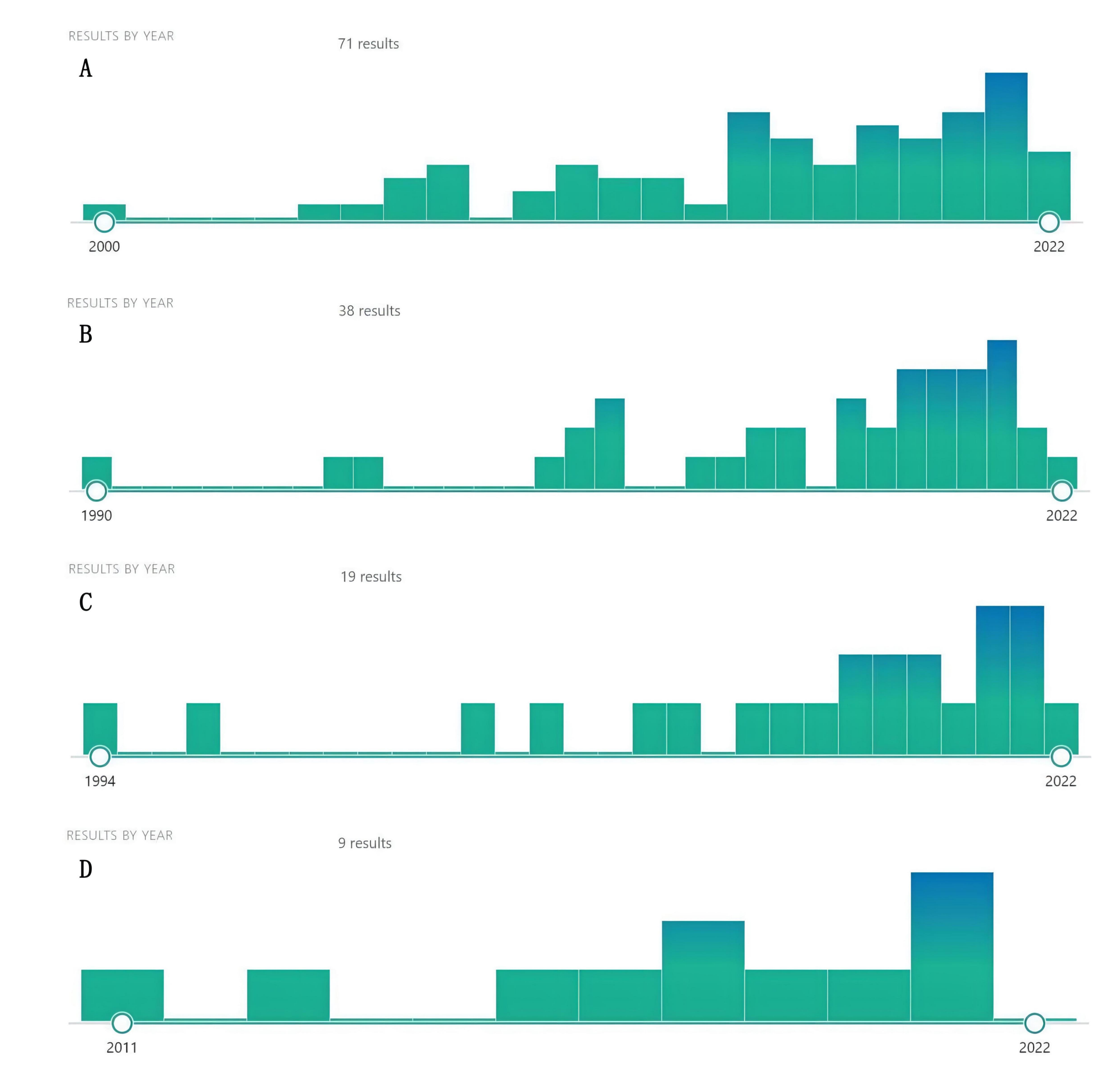

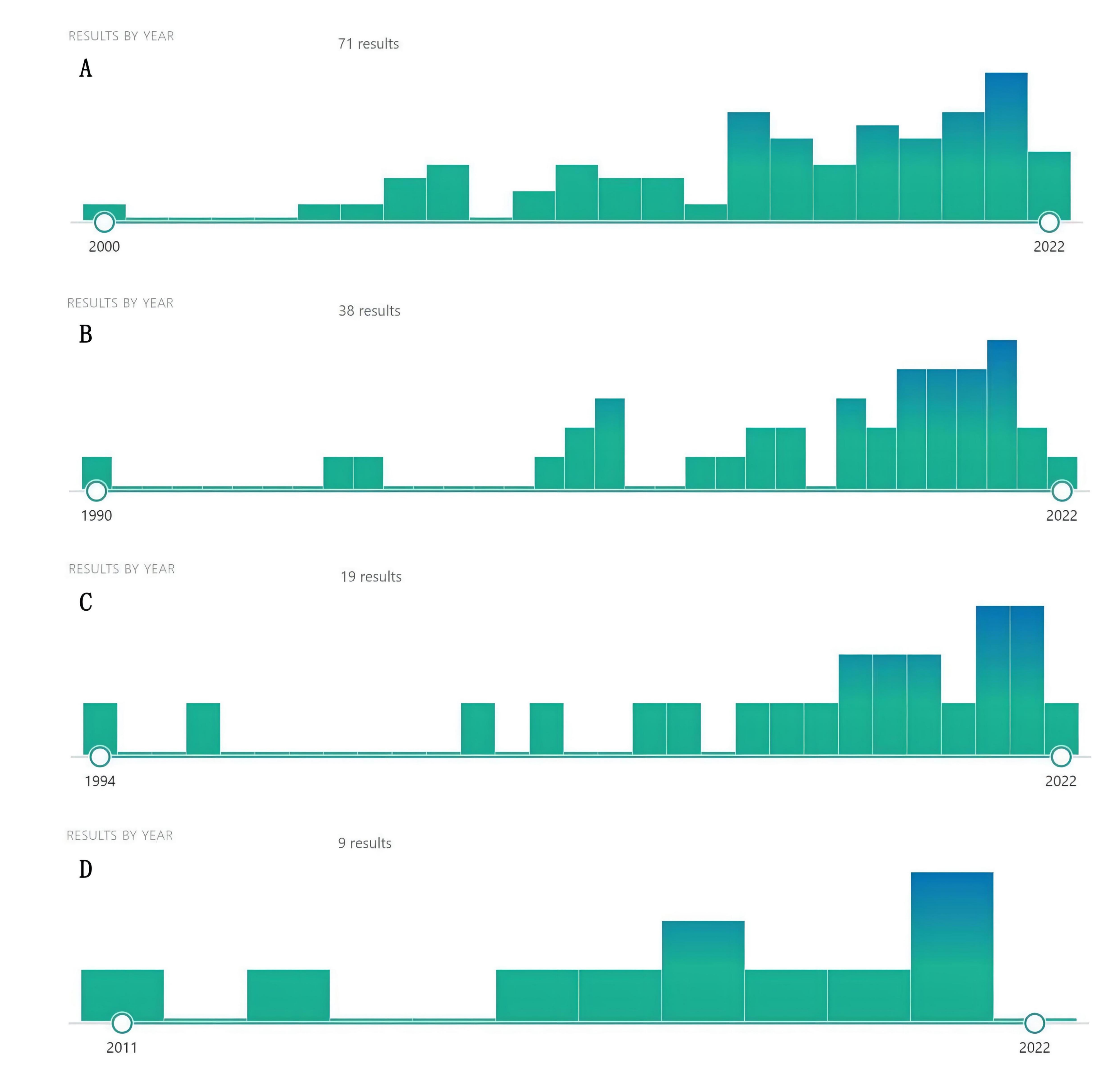

Using the name of natural compounds and “cancer” OR “tumor” OR “carcinoma” OR “malignancy” as keywords to search PubMed, we found a number of natural compounds with the potential to treat cancer and cancer metastasis. Although there were few studies on these natural compounds against cancer, they recently proliferated, indicating that natural compounds, such as dihydrotanshinone, sclareol, isoimperatorin, and girinimbin have a great anticancer potential, warranting further research (Fig. 3). At the same time, we predicted the potential targets of these four natural compounds through the SwissTargetPrediction database and screened out the top ten targets with a probability score greater than 0 (Table 4).

Fig. 3.

Fig. 3.Increasing literature about dihydrotanshinone (A), Sclareol (B), Isoimperatorin (C), and girinimbin (D) (From PubMed).

| Potential natural compounds | Potential targets | Probability score |

| Dihydrotanshinone | AKR1B1 | 1 |

| ACHE | 1 | |

| CES1 | 1 | |

| PTPN6 | 1 | |

| CES2 | 1 | |

| PTPN11 | 1 | |

| STAT3 | 0.114337559 | |

| IDO1 | 0.114337559 | |

| MALT1 | 0.106099949 | |

| KDM4E | 0.097874534 | |

| Sclareol | UGT2B7 | 0.206265233 |

| HSD11B1 | 0.182601417 | |

| PTGS1 | 0.174646372 | |

| NR1H3 | 0.111501865 | |

| AR | 0.111501865 | |

| CYP19A1 | 0.111501865 | |

| NR3C2 | 0.111501865 | |

| TRPV1 | 0.111501865 | |

| IDO1 | 0.111501865 | |

| CNR2 | 0.111501865 | |

| Isoimperatorin | BACE1 | 0.149732594 |

| KCNA3 | 0.108770969 | |

| SRD5A1 | 0.108770969 | |

| CA12 | 0.100578902 | |

| CA9 | 0.100578902 | |

| KCNA5 | 0.100578902 | |

| MAOA | 0.100578902 | |

| ALOX5 | 0.100578902 | |

| MAOB | 0.100578902 | |

| ALOX15 | 0.100578902 | |

| Girinimbin | DYRK1A | 0.100578902 |

| BCHE | 0.100578902 | |

| CLK4 | 0.100578902 | |

| HTR2B | 0.100578902 | |

| HTR2C | 0.100578902 | |

| SLC6A3 | 0.100578902 | |

| HTR6 | 0.100578902 | |

| AKT1 | 0.100578902 | |

| CLK2 | 0.100578902 | |

| DYRK3 | 0.100578902 |

Malignant tumors are common diseases with biological characteristics such as cell differentiation, abnormal proliferation, infiltration, and metastasis, and have become a worldwide problem. Western medicine treatments have a significant effect on eliminating malignant tumors, but are often accompanied by a variety of toxic and adverse effects such as gastrointestinal reactions, myelosuppression, and decreased immunity. Traditional Chinese medicine has a history of more than 2000 years in the prevention and treatment of tumors. It has played an important role in the treatment of cancers: increasing evidence has shown that TCM, usually combined with western medicine, can improve response to western medicine, reduce the toxic and side effects, improve the quality of life of patients, stabilize the tumor body, prevent tumor recurrence and metastasis, prolong the survival period, and increase the survival rate. Accordingly, the anti-tumor effects and mechanisms of TCM have become focal points of research. The development of modern science and technology, and the complementary advantages of multi-disciplinary and multi-field modalities help promite TCM’s broad prospects in anti-cancer field. In anticancer treatment, the application of TCM is limited due to the complex composition, difficult dosage control, and unclear mechanisms of action. With the standardization and modernization of TCM, through the multi-field and multi-level objective, accurate, qualitative, and quantitative research on the anti-cancer efficacy of TCM, the shortcomings of TCM (such as complex composition), unclear mechanisms, and unclear targets have been gradually overcome. Traditional Chinese medicine played an increasingly important role in the field of anti-cancer treatment.

With the continuous research on the natural ingredients of TCM, we found that these ingredients can exert anti-tumor activities in various stages of tumor growth, reflected in the following aspects: Improve the immune activity of the body, reduce the immunosuppressive effect of tumor cells, and inhibit the growth of tumor cells; regulate specific signaling pathways, inhibit tumor cell proliferation, and promote their apoptosis and autophagy; inhibit tumor angiogenesis; inhibit cancer cell invasion and metastasis ability; induce cancer cell cycle arrest, promoting its apoptosis, etc.

In this review, we found five commonly used anticancer Chinese herbal medicines

and 168 qualified natural compounds extracted from them (oral bioavailability

Although this paper searched and screened the relevant literature to the greatest extent possible, there are still certain limitations. In order to ensure the stability and reliability of the results, we selected human-related cell experiments and excluded clinical studies and animal experiments, but this did not ensure the comprehensive inclusion of all eligible studies. Further, we only provided a preliminary summary of the mechanisms and targets, and did not perform a systematic analysis.

Within the five most widely used anti-cancer Chinese herbal medicines,168 effective natural compounds were identified. The three most common natural compounds and their main mechanisms of action in the prevention and treatment of cancer and cancer metastasis were reviewed and summarized. In addition, our review found that four natural compounds have recently attracted the most attention in the field of anti-cancer study, indicating they are worthy of further research. Our findings provide some inspiration for future research on natural compounds against tumors and new insights into the role and mechanisms of natural compounds in the prevention and treatment of cancer and cancer metastasis.

QW, YW, and ELHL designed the research study. YW, HY, XS, MC, and GY performed the research. LL provided advice on data collection. HY analyzed the data. XX, YX, and GY retrieved and collected the data. YW wrote the manuscript. All authors contributed to editorial changes in the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Not applicable.

Acknowledge the support of the Science and Technology Development Fund, Macau SAR, the National Natural Science Foundation of China; 2020 Young Qihuang Scholar funded by the National Adminstation of Traditional Chinese Medicine; Guangdong Medical Science and technology research foundation project, the Zhejiang province science and technology project of TCM, Shenzhen Science and Technology Program.

This study was funded by the Science and Technology Development Fund, Macau SAR (file No.: 0098/2021/A2, 130/2017/A3, and 0099/2018/A3), National Natural Science Foundation of China (grant No. 81874380, 82022075, 81730108, and 81973635), 2020 Young Qihuang Scholar funded by the National Adminstation of Traditional Chinese Medicine, the Science and Technology Planning Project of Guangdong Province (2020B1212030008), Guangdong Medical Science and technology research foundation project (No. C2021102), and Shenzhen Science and Technology Program (No. JCYJ20210324111213038).

The authors declare no conflict of interest.