1 Key Laboratory of Tropical Translational Medicine of Ministry of Education, Hainan Key Laboratory for Research and Development of Tropical Herbs, Hainan Medical University, 571199 Haikou, Hainan, China

2 Institute for Molecular Bioscience, The University of Queensland, St. Lucia, Brisbane, QLD 4072, Australia

Abstract

As primitive metazoa, sea anemones are rich in various bioactive peptide neurotoxins. These peptides have been applied to neuroscience research tools or directly developed as marine drugs. To date, more than 1100 species of sea anemones have been reported, but only 5% of the species have been used to isolate and identify sea anemone peptide neurotoxins. There is an urgent need for more systematic discovery and study of peptide neurotoxins in sea anemones. In this review, we have gathered the currently available methods from crude venom purification and gene cloning to venom multiomics, employing these techniques for discovering novel sea anemone peptide neurotoxins. In addition, the three-dimensional structures and targets of sea anemone peptide neurotoxins are summarized. Therefore, the purpose of this review is to provide a reference for the discovery, development, and utilization of sea anemone peptide neurotoxins.

Keywords

- Sea anemone

- Peptide neurotoxins

- Transcriptomics

- Proteomics

- Multiomics

- Three-dimensional structure

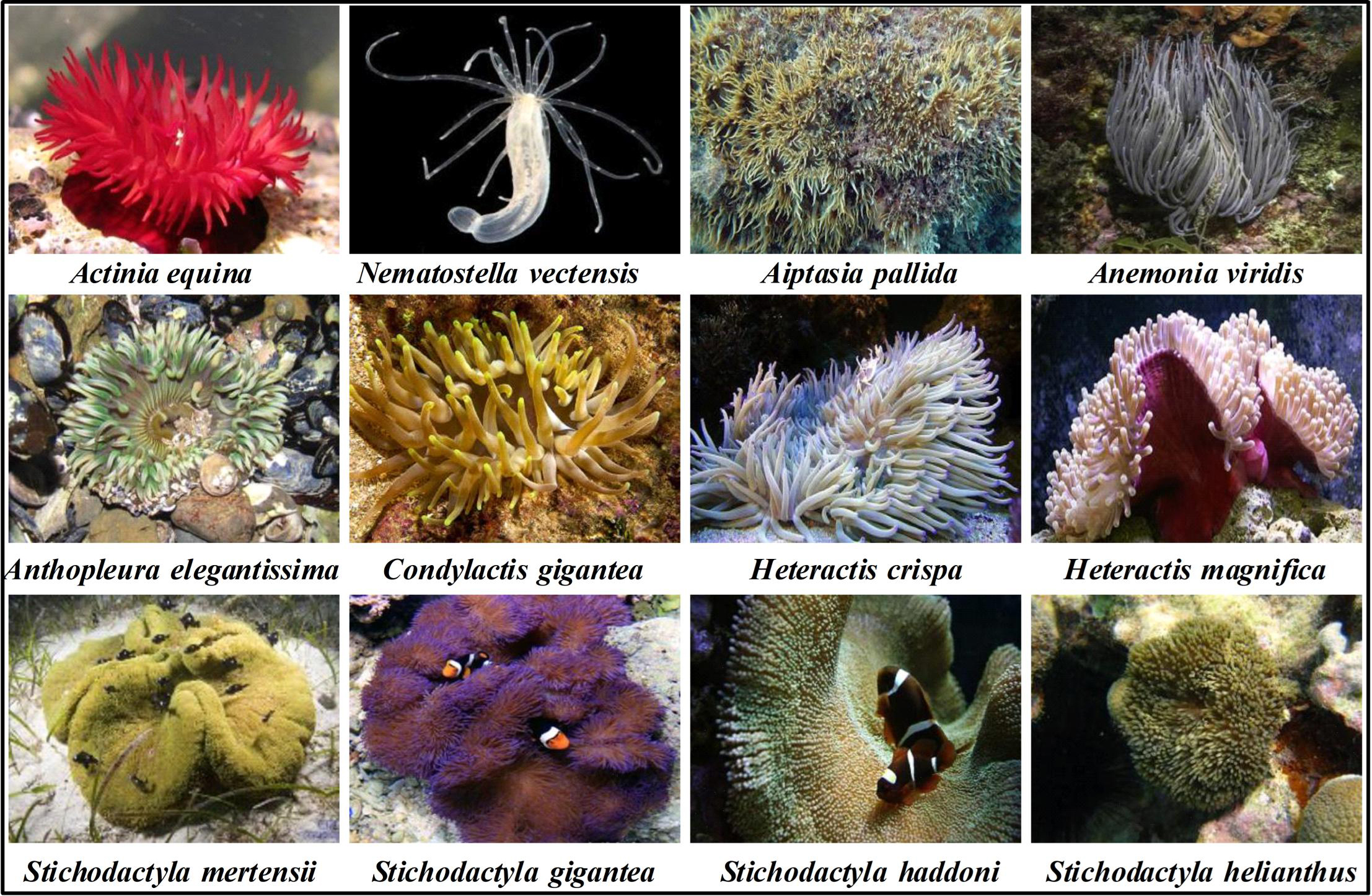

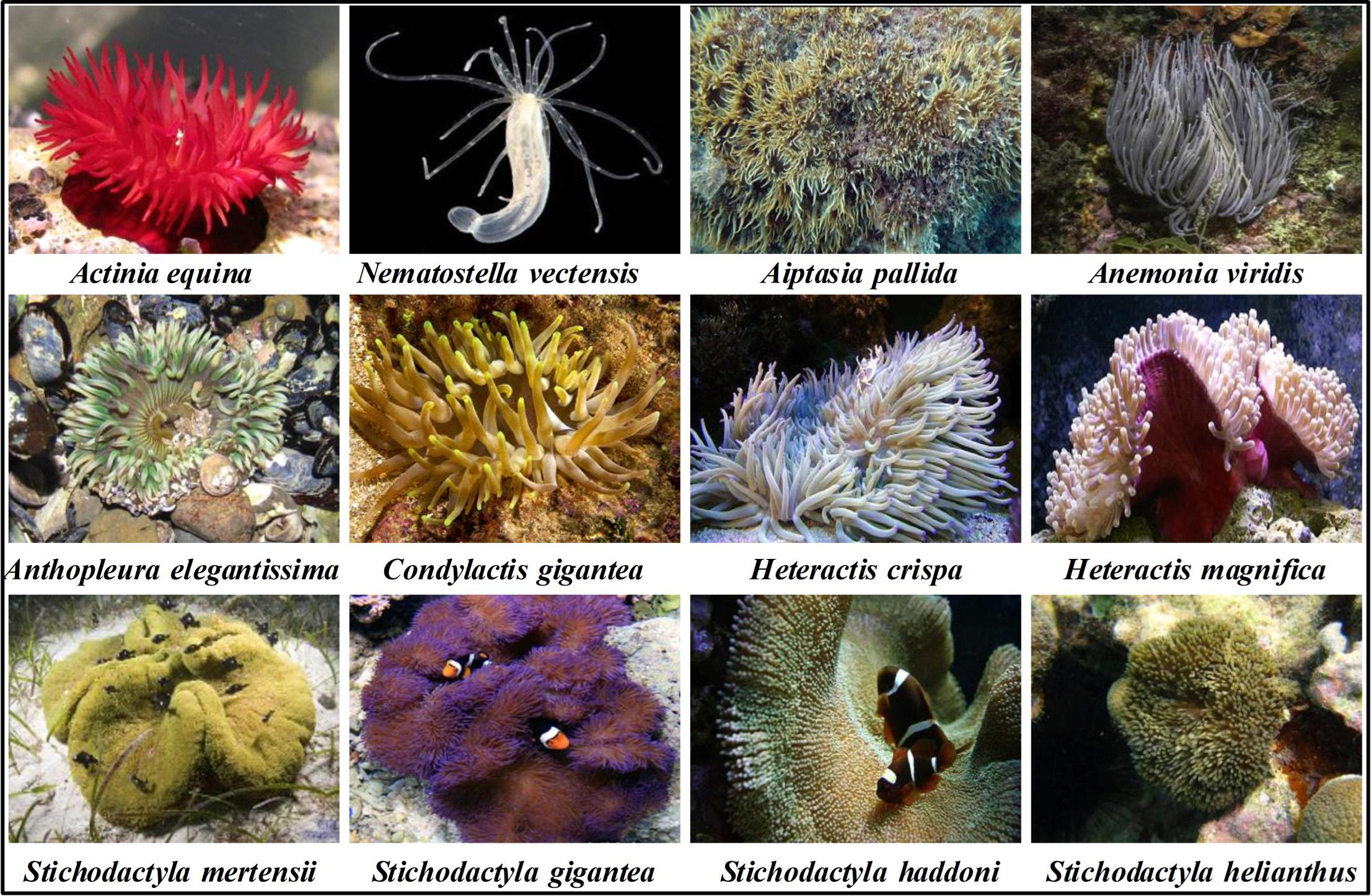

Sea anemones (Actiniaria), sometimes called the flowers of the sea, are among the oldest surviving orders of venomous animals that belong to the phylum Cnidaria [1]. Fossil data and genomics evidence suggest that their origin was prior to the Ediacaran period ~750 million years ago [2]. Within the class Anthozoa, sea anemones form the hexacorallian order Actiniaria. Actiniaria are divided into two extant suborders: Anenthemonae and Enthemonae. Anenthemonae is a suborder with fewer species, containing members of the families Actinernidae, Edwardsiidae, and Halcuriidae [3]. The model organism Nematostella vectensis is the most familiar and well-studied member of this Edwardsiidae family [4]. Enthemonae contains the preponderant majority of species and anatomical diversity within Actiniaria, further subdivided into the superfamilies Actinioidea, Actinostoloidea, and Metridiodea [5]. Sea anemones have strong adaptability and can be distributed in various marine environments from the intertidal zone to the abyssal sea and from tropical waters to polar seas [6]. Fig. 1 shows the representative sea anemone species worldwide; some of these sea anemones have a large biomass and play important ecological roles [7]. Sea anemones have a simple nervous system and lack the lowest brain base or central information processing mechanism. Without true muscle tissue and visual capacity, they rely on nematocysts on their tentacles to release venom for predation, defense, and intraspecific competition [8, 9]. Nematocytes present in all cnidarians produce highly complex venom-filled organelles known as nematocysts [10]. Nematocysts are the primary venom delivery apparatus of cnidarians, composed of a capsule containing an inverted tubule capable, which are forcefully everted and inject venom into the target organism when stimulated mechanically or chemically [10, 11].

Fig. 1.

Fig. 1.Representative sea anemone species worldwide.

Previous studies have shown that sea anemone toxins contain complex mixtures of

proteins, peptides, and nonproteinaceous compounds (Table 1, Ref. [5, 12, 13, 14, 15, 16, 17, 18, 19, 20, 21, 22, 23, 24, 25, 26, 27, 28, 29, 30, 31]) [32, 19, 33].

Typically, the main peptide/protein compounds found in sea anemone venom can be

divided into three groups: (1) phospholipase A2 enzymes (PLA2) that catalyze the

hydrolysis of phospholipids and participate in inflammatory reactions [34, 35];

(2) cytolysins, which mainly form pores on the cell membrane and cause cell lysis

[15]; and (3) peptide neurotoxins that act on voltage-gated sodium (Na

| Type | Structure family | Pharmacological group | Ref. | |

| Nonproteinaceous compounds | Purine | Adenosine receptor | [12] | |

| - | 5-HT3 receptor | [13] | ||

| Proteins | Enzymes | CYP74 | Unknown | [14] |

| PLA2 | PLA2 | [15] | ||

| Type III cytolysins | ||||

| Endonuclease D | Unknown | [5] | ||

| Serine protease S1 | Unknown | [5] | ||

| Cytotoxins | Actinoporins | Type II cytolysins | [16] | |

| CRISP | Unknown | [17] | ||

| WSC domain proteins | Unknown | [18] | ||

| Peptide neurotoxins | ATX III | Na |

[19] | |

| ASIC | [20] | |||

| K |

[21] | |||

| Na |

[5] | |||

| Na |

||||

| Na |

||||

| BBH | ASIC | [5] | ||

| K |

[22] | |||

| EGF-like | EGF activity | [23] | ||

| TRPV1 | [24] | |||

| ICK | ASIC | [25] | ||

| K | ||||

| Kunitz-domain | K |

[26] | ||

| TRPV1 | [27] | |||

| Protease inhibitor | [28] | |||

| PHAB | K |

[29] | ||

| SCRiPs | TRPA1 | [30] | ||

| ShK | K |

[31] | ||

| Note: 5-HT3, 5-hydroxytryptamine 3; CYP74, Cytochrome P450 proteins 74; PLA2,

Phospholipase type A2; CRISP, Cysteine-rich proteins; WSC domain, Cell wall

integrity and stress response component domain; ATX III, Anemonia sulcate toxin

III; ASIC, Acid-sensing ion channel; BBH, Boundless | ||||

According to the latest published data in the WoRMS database, 1162 species of sea anemones have been recorded worldwide, and high-throughput transcriptome sequencing shows that there are more than 100 different peptide sequences in each sea anemone to date [5, 45]. In particular, 612 putative protein and peptide sequences were discovered from the sea anemone Anthopleura elegantissima[46]. Owing to the small overlap of sea anemone toxins among different sea anemone species and significant interspecies variation (e.g., Stichodactylidae family), there are an estimated 1,200,000 natural peptides that are produced by sea anemones [47]. However, only 5% of the species and approximately 378 toxins from sea anemones are annotated in UniProtKB (https://www.uniprot.org/). Sea anemones are a treasure trove for relatively undeveloped bioactive and therapeutic compounds. Therefore, the discovery of novel sea anemone peptide neurotoxins from sea anemone resources using combined omics methods and high-throughput biological assays is essential for the development of sea anemone peptide neurotoxin drugs.

Traditional isolation and purification of sea anemone toxin are usually

performed directly from the crude venom. At present, there are three main methods

for extracting sea anemone crude venom: homogenization, milking, and electrical

stimulation methods [48, 49, 50]. A total of 43 sea anemone peptide neurotoxins have

been successfully isolated from different types of sea anemones by traditional

crude venom purification, and these peptide neurotoxins are summarized in Table 2

(Ref. [23, 26, 30, 48, 51, 52, 53, 54, 55, 56, 57, 58, 59, 60, 61, 62, 63, 64, 65, 66, 67, 68, 69, 70, 71, 72, 73, 74, 75, 76]). Among the sea anemone

peptide neurotoxins found by traditional crude venom isolates, the most common

cysteine pattern is CXC-C-C-CC, and these toxins mainly act on the Na

| Method | Name | Species | Sequence | Target/Activity | Ref. |

| Homogenization | δ-TLTX-Ca1a | Cryptodendrum adhaesivum | VACKCDDDGPDVRSATFTGTVDLGSCNSGWEKCASYYTVIADCCRKPRG | Na |

[51] |

| δ-TLTX-Ta1a | Thalassianthus aster | VACKCDDDGPDIRSATLTGTVDLGSCDEGWEKCASYYTVIADCCRRPRS | Na |

[51] | |

| gigantoxin III | Stichodactyla gigantea | AACKCDDDGPDIRSATLTGTVDLGSCNEGWEKCASFYTILADCCRRPR | Na |

[23] | |

| gigantoxin II | Stichodactyla gigantea | GVPCRCDSGPHVRGNTLTGTVWVFGCPSGWHKCQKGSSTCCKQ | Na |

[23] | |

| CgNa | Condylactis gigantea | GVPCRCDSDGPTVHGNTLSGTVWVGSCASGWHKCNDEYNIAYECCKE | Na |

[52] | |

| AdE-1 | Aiptasia diaphana | GIPCRCDKNSDELNGEQSYMNGNCGDGWKKCRSVNAIFNCCQRV | Na |

[53] | |

| Av2 | Anemonia viridis | GVPCLCDSDGPSVRGNTLSGIIWLAGCPSGWHNCKKHGPTIGWCCKQ | Na |

[54] | |

| Av1 | Anemonia viridis | GAACLCKSDGPNTRGNSMSGTIWVFGCPSGWNNCEGRAIIGYCCKQ | Na |

[54] | |

| Anthopleurin-A | Anthopleura xanthogrammica | GVSCLCDSDGPSVRGNTLSGTLWLYPSGCPSGWHNCKAHGPTIGWCCKQ | Na |

[55] | |

| Anthopleurin-B | Anthopleura xanthogrammica | GVPCLCDSDGPRPRGNTLSGILWFYPSGCPSGWHNCKAHGPNIGWCCKK | Na |

[56] | |

| Bg II | Bunodosoma granulifera | GASCRCDSDGPTSRGNTLTGTLWLIGRCPSGWHNCRGSGPFIGYCCKQ | Na |

[57] | |

| Bg III | Bunodosoma granulifera | GASCRCDSDGPTSRGDTLTGTLWLIGRCPSGWHNCRGSGPFIGYCCKQ | Na |

[57] | |

| APETx1 | Anthopleura elegantissima | GTTCYCGKTIGIYWFGTKTCPSNRGYTGSCGYFLGICCYPVD | Na |

[58] | |

| APETx4 | Anthopleura elegantissima | GTTCYCGKTIGIYWFGKYSCPTNRGYTGSCPYFLGICCYPVD | K |

[59] | |

| APETx2 | Anthopleura elegantissima | GTACSCGNSKGIYWFYRPSCPTDRGYTGSCRYFLGTCCTPAD | ASIC3 | [60] | |

| π-AnmTX Hcr 1b-2 | Heteractis crispa | GTPCKCHGYIGVYWFMLAGCPNGYGYNLSCPYFLGICCVKK | ASIC1a, ASIC3 | [61] | |

| π-AnmTX Hcr 1b-3 | Heteractis crispa | GTPCKCHGYIGVYWFMLAGCPDGYGYNLSCPYFLGICCVKK | ASIC1a | [61] | |

| π-AnmTX Hcr 1b-4 | Heteractis crispa | GTPCDCYGYTGVYWFMLSRCPSGYGYNLSCHYFMGICCVKR | ASIC1a | [61] | |

| PhcrTx2 | Phymanthus crucifer | ALPCRCEGKTEYGDKWIFHGGCPNDYGYNDRCFMKPGSVCCYPKYE | unknown | [62] | |

| Am II | Antheopsis maculata | ALLSCRCEGKTEYGDKWLFHGGCPNNYGYNYKCFMKPGAVCCYPQN | unknown | [63] | |

| Am I | Antheopsis maculata | NVAVPPCGDCYQQVGNTCVRVPSLCPS | Na |

[63] | |

| ShK | Stichodactyla helianthus | RSCIDTIPKSRCTAFQCKHSMKYRLSFCRKTCGTC | K |

[64] | |

| AsKs | Bunadosoma granulifa | ACKDNFAAATCKHVKENKNCGSQKYATNCAKTCGKC | K |

[65] | |

| AETX K | Anemonia erythraea | ACKDYLPKSECTQFRCRTSMKYKYTNCKKTCGTC | K |

[66] | |

| BgK | Bunodosoma granulifera | VCRDWFKETACRHAKSLGNCRTSQKYRANCAKTCELC | K |

[67] | |

| AeK | Hteractis magnifica | GCKDNFSANTCKHVKANNNCGSQKYATNCAKTCGKC | K |

[68] | |

| APEKTx1 | Anthopleura elegantissima | INSICLLPKKQGFCRARFYYNSSTRRCEMFYYGGCGGNANNFNTLEECEKVCLGYGEAWKAP | K |

[26] | |

| HCRG1 | Heteractis crispa | RGICSEPKVVGPCKAGLRRFYYDSETGECKPFIYGGCKGNKNNFETLHACRGICRA | Serine protease inhibitor | [69] | |

| HCRG2 | Heteractis crispa | RGICLEPKVVGPCKARIRRFYYDSETGKCTPFIYGGCGGNGNNFETLHACRGICRA | Serine protease inhibitor | [69] | |

| acrorhagin II | Stichodactyla gigantea | TDCRFVGAKCTKANNPCVGKVCNGYQLYCPADDDHCIMKLTFIP | crab toxicity | [70] | |

| gigantoxin I | Stichodactyla gigantea | DVGVACTGQYASSFCLNGGTCRYIPELGEYYCICPGDYTGHRCEQMSV | EGF activity | [23] | |

| Av3 | Anemonia viridis | RSCCPCYWGGCPWGQNCYPEGCSGPKV | Na |

[54] | |

| acrorhagin I | Actinia equina | SSTPDGTWVKCRHDCFTKYKSCQMSDSCHDEQSCHQCHVKHTDCVNTGCP | crab toxicity | [70] | |

| Electrical stimulation | δ-AITX-Bca1a | Bunodosoma capense | CLCNSDGPSVRGNTLSGILWLAGCPSGWHNCKKHKPTIGWCCK | Na |

[71] |

| BcIII | Bunodosoma caissarum | GVACRCDSDGPTSRGNTLTGTLWLTGGCPSGWHNCRGSGP FIGYCCKK | Na |

[48] | |

| BcIV | Bunodosoma caissarum | GLPCDCHGHTGTYWLNYYSKCPKGYGYTGRCRYLVGSCCYK | Na |

[72] | |

| AbeTx1 | Actinia bermudensis | RCKTCSKGRCRPKPNCG | K |

[73] | |

| BcsTx1 | Bunodosoma caissarum | ACIDRFPTGTCKHVKKGGSCKNSQKYRINCAKTCGLCH | K |

[74] | |

| BcsTx2 | Bunodosomacaissarum | ACKDGFPTATCQHAKLVGNCKNSQKYRANCAKTCGPC | K |

[74] | |

| BcsTx3 | Bunodosoma caissarum | GCKGKYEECTRDSDCCDEKNRSGRKLRCLTQCDEGGCLKYRQCLFYGGLQ | K |

[75] | |

| τ-AnmTx Ueq 12-1 | Urticina eques | CYPGQPGCGHCSRPNYCEGARCESGFHDCGSDHWCDASGDRCCCA | TRPA1 | [30] | |

| Milking | CGTX-II | Bunodosoma cangicum | GVACRCDSDGPTVRGDSLSGTLWLTGGCPSGWHNCRGSGPFIGYCCKK | Na |

[76] |

| CGTX-III | Bunodosoma cangicum | GVACRCDSDGPTVRGDSLSGTLWLTGGCPSGWHNCRGSGPFIGYCCKK | Na |

[76] | |

| Note: C is marked in red font to highlight cysteine. | |||||

The earliest report of the purification of sea anemone peptide neurotoxin was in the 1960s [78]. At that time, several to dozens of sea anemones were collected and homogenized to obtain enough venom for the isolation of one or a few sea anemone peptide neurotoxins [19, 79, 80, 81]. The crude venom obtained using homogenization was separated and purified by gel chromatography and reverse phase high performance liquid chromatography (HPLC) [53]. A total of 11 kg of Condylactis gigantea from the Caribbean Sea near Havana was collected by Standker et al. [52] and homogenized to obtain crude venom. The venom was then further isolated and purified to obtain the CgNa toxin [52]. Similar studies include the sea anemone peptides Av1-3 (previously named ATX I-III) with neurotoxic activity that were isolated from 5.5 kg of wet Anemonia viridis (previously named Anemonia sulcata) [54].

To date, 33 sea anemone peptide neurotoxins have been isolated by extracting venom from different types of sea anemones using the homogenization method (Table 2). Among these, important and typical sea anemone peptide neurotoxins include ShK, CgNa, AdE-1, Anthopleurin-A, and Anthopleurin-B. The most frequently studied sea anemone toxin is the ShK toxin from the giant sun anemone (Stichodactyla helianthus) [64]. This peptide has the ability to block the Kv1.3 channels of T lymphocytes, inhibiting their activation and therefore acting as a therapeutic to treat autoimmune diseases [82, 83]. New analogues of ShK, with good selectivity for Kv1.3 channels, have also been developed [84, 85, 86]. An analogue of this peptide (ShK-186) has been developed into the first-in-class clinical candidate dalazatide, and phase I clinical trials have been completed for the treatment of psoriasis [87, 88]. Dalazatide (formerly known as ShK-186) is being advanced as a treatment for various autoimmune diseases including type 1 diabetes, inflammatory bowel diseases, body myositis, lupus, psoriasis, multiple sclerosis, psoriatic arthritis, rheumatoid arthritis, and ANCA vasculitis [1, 89].

Isolation of toxins is usually performed by extracting toxins from homogenates of whole animals or frozen–thawed sea anemones or by isolation of the nematocysts followed by purification using various methods [90, 91]. The milking technique was first applied by Barnes to directly collect pure venom from jellyfish, where nematocysts are discharged through an amnion membrane [92]. Sencic and Macek described a new and simpler purification procedure of sea anemone toxins from the venom obtained using a new milking method different from that reported by Barnes [92]. They obtained two lethal and hemolytic peptide toxins, caritoxins I and II, from the sea anemone Actinia cari using the milking method [50].

Milking involves the gentle squeezing of sea anemones to collect their

secretions, which is similar to stimulating sea anemones to release venom in the

natural environment [93]. This method has the advantages of not harming the sea

anemone, obtaining purer venom, and being able to extract the venom repeatedly.

Therefore, milking has become an effective method to extract sea anemone venom,

after homogenization and freeze-thawing methods. Zaharenko et al. [76]

obtained the cangitoxin (CGTX) analogue CGTX-II directly from sea anemone venom

by milking followed by two chromatographic steps. CGTC-II inhibited

Na

Electrical stimulation is often used to extract animal venom from inland poisonous animals such as spiders, scorpions, and wasps [94, 95, 96]. Malpezzi et al. [48] applied electrical stimulation to extract sea anemone Stichodactyla helianthus (formerly Stoichactis helianthus) venom for the first time and successfully isolated BcI, BcII, and BcIII. The main action of BcIII on Nav channels is a slowing of the inactivation process of the sodium current, with no significant effects on the activation kinetics. It is important to emphasize that the method used to obtain the venom in the present paper has many advantages: because it results in less contamination with other compounds from the sea anemone body, it simplifies the purification procedures and keeps the animals alive, allowing them to be reused to obtain more venom or return them to the sea.

BcIV, AbeTx1, BcsTx1-3,

In general, the extraction method of these venoms is time-consuming and labor-intensive. It is difficult to obtain a high amount of venom to isolate and purify sea anemone peptide neurotoxins, especially for rare sea anemone species. Therefore, more effective venom separation and extraction methods are needed to speed up the discovery of novel sea anemone peptide neurotoxins. This section does not represent a full-scale explanation of all the techniques used and improvements since the 1960s but instead provides a brief overview of the most commonly used techniques for sea anemone venom extractions for reference purposes.

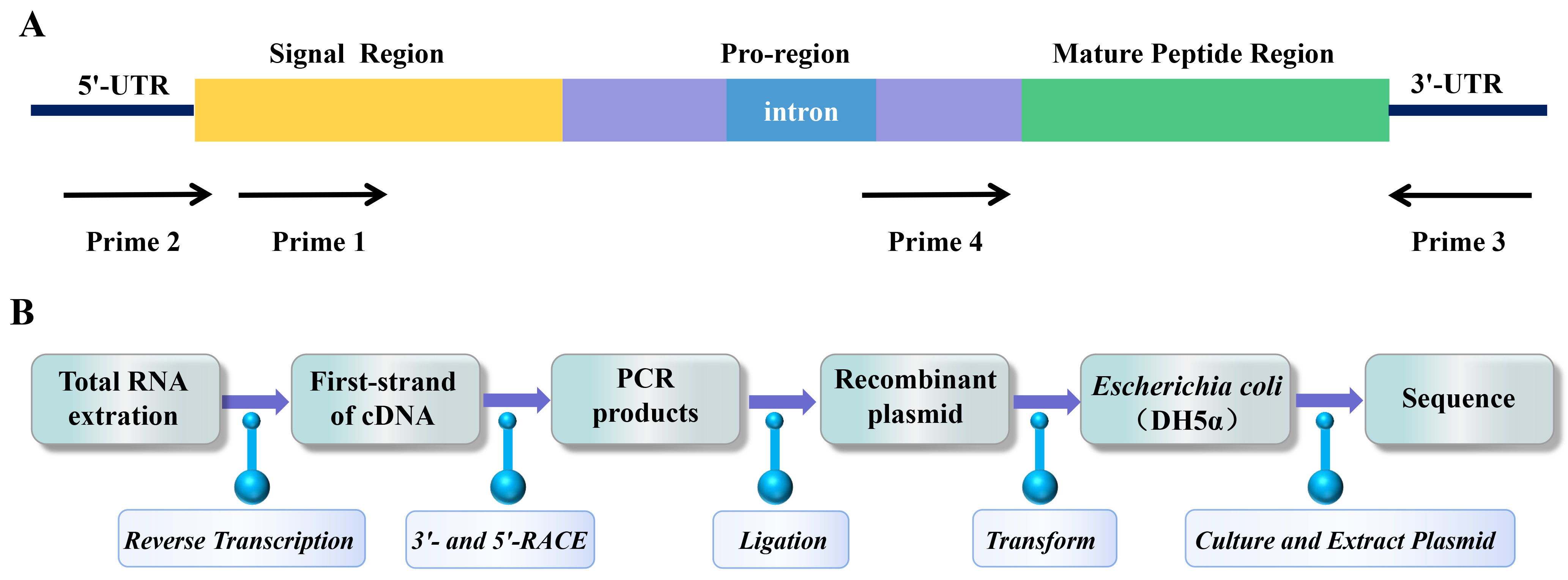

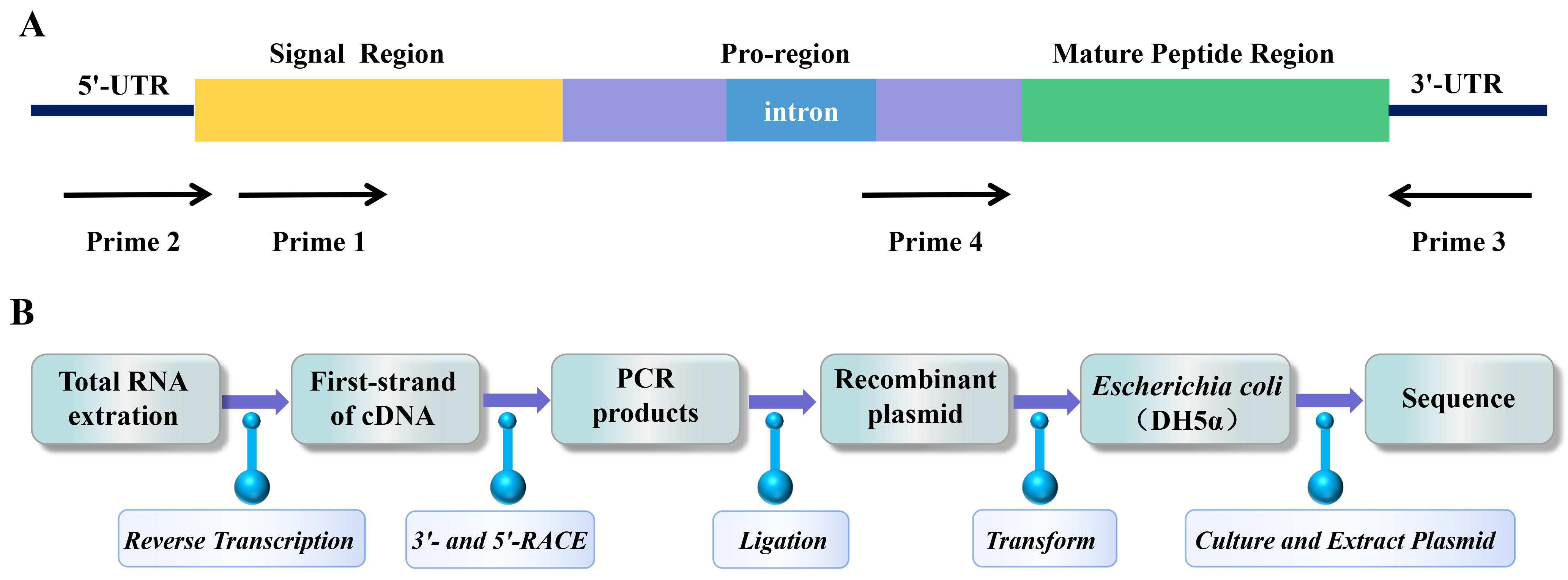

Gene cloning was used to discover novel sea anemone peptide neurotoxins at the end of the 20th century [98]. The advantage of gene cloning is that the peptide neurotoxin gene can be amplified from a small number of sea anemone tentacles by PCR. This method overcomes the limitation of crude toxin purification method in large demand for sea anemone samples, and has attracted the attention of scientific researchers [99]. Primer design is a key step in any experiment using PCR to target and amplify known nucleotide sequences of interest [100]. Rationally designed primers can not only improve PCR amplification efficiency but can also screen target sequences with high specificity [101]. Primers were designed and synthesized based on the conserved sequence in the signal region or the relatively conserved introns in the pro-region or untranslated region of the 3’- or 5’-UTR of a specific known sea anemone peptide neurotoxin precursor (Fig. 2A) [102]. Usually, cDNA is prepared by reverse transcription from total RNA extracted from sea anemones [98]. Total cDNA was used as a template, and PCR amplification was performed with specific primers to perform 3’- and 5’-RACE [102]. The PCR products were purified by electrophoresis on agarose gel, ligated to the plasmid vector, and transferred to Escherichia coli for replication, proliferation, and sequencing (Fig. 2B) [103].

Fig. 2.

Fig. 2.PCR amplification strategy and cloning process of sea anemone gene. (A) PCR amplification strategy to clone sea anemone toxin precursor genes from genomic DNA. (B) The process of gene cloning sea anemone peptide neurotoxins.

A total of nine types of sea anemone peptide neurotoxins were obtained by gene

cloning, as shown in Table 3 (Ref. [40, 51, 70, 104, 105, 106, 107]). The

most common cysteine pattern in peptide neurotoxins obtained by gene cloning is

CXC-C-C-CC, and its main target is the Na

| Name | Species | Sequence | Target/Activity | Ref. |

| SHTX IV | Stichodactyla haddoni | AACKCDDDGPDIRSATLTGTVDFWNCNEGWEKCTAVYTAVASCCRKKKG | Na |

[104] |

| δ-TLTX-Hh1x | Heterodactyla hemprichii | VACKCDDDGPDIRSATLTGTVDLGSCNEGWEKCASYYTVVADCCRRRRS | Na |

[51] |

| Hk2a | Anthopleura sp | MGVACLCDSDGPSVRGNTLSGTLWLAGCPSGWHNCKAHGPTIGWCCKQ | Na |

[105] |

| Crassicorin-I | Urticina crassicornis | GASCDCHPFVGTYWFGISNCPSGHGYPKKCASFFGVCCVK | antimicrobial activity | [106] |

| acrorhagin Ia | Actinia equina | SLTPSSDIPWEKCRHDCFAKYMSCQMSDSCHNKPSCRQCQVTYAICVSTGCP | crab toxicity | [70] |

| HCRG21 | Heteractis crispa | RGICSEPKVVGPCTAYFRRFYFDSETGKCTPFIYGGCEGNGNNFETLRACRAICRA | TRPA1 | [40] |

| SHTX III | Stichodactyla haddoni | TEEMPALCHLQPDVPKCRGYFPRYYYNPEVGKCEQFIYGGCGGNKNNFVSFEACRATCIIPL | K |

[104] |

| Magnificamide | Heteractis magnifica | SEGTSCYIYHGVYGICKAKCAEDMKAMAGMGVCEGDLCCYKTPW | [107] | |

| Note: C is marked in red font to highlight cysteine. | ||||

Although natural crude venom purification and gene cloning have greatly helped efforts to discover novel sea anemone peptide neurotoxins, most of the unknown sea anemone peptide neurotoxins have not yet been characterized. Therefore, there is an urgent need to develop more efficient, resource-conserving, and high-throughput methods. Transcriptomics, proteomics, and multiomics integration have opened a new era in the discovery of sea anemone toxins, rapidly accelerating the discovery of novel sea anemone peptide neurotoxins [1, 109].

The high throughput technologies used in venomics, especially transcriptomics, has produced large data sets that need bioinformatics support to fully explore their potential [110, 111, 112]. Modern bioinformatics tools have been recently developed to mine venoms, helping focus experimental research on the most potentially interesting neurotoxins [113]. The number of neurotoxins unraveled by high throughput multiomics approaches is very large, efficient computational approaches are required to mine this massive amount of data. Computational approaches that have been developed to help predict neurotoxins molecular targets, three-dimensional structures and functions, and identifying outstanding neurotoxins with potential new characteristics [114, 115, 116].

General databases, such as the Protein Data Bank (PDB) [117], UniProt [118], and NCBI Genbank/GenPept [119], play important roles in simplifying access to information about sea anemone neurotoxin sequences and three-dimensional structures. However, the information about sea anemone neurotoxins is not standardized in these resources, especially the naming of neurotoxins and pharmacological activities, and mining for sea anemone neurotoxins is difficult. A recently developed resource, VenomZone, is provided by the Swiss Institute of Bioinformatics (SIB), and has information about the venoms from six types of organisms, including sea anemones, cone snail, spider, Scorpions, bees and snakes. However, Specialized databases, from venomous animals, are slowly emerging. ISOB (Indigenous snake species of Bangladesh) [120], Arachnoserver [121], and Conoserver [122] provide information on venoms from respectively.

The term “transcriptome” was first used by Velculescu to analyze a set of genes expressed in the yeast genome in a scientific paper in 1997 [123]. In more than 30 years of development, sequencing technology has achieved considerable development, from the first to the third generation of sequencing technologies [124]. At present, the second-generation short-read-length sequencing technology still holds an absolute dominant position in the global sequencing market, but third-generation sequencing technology has also developed rapidly in the past few years [125]. With the rapid development of molecular biology and the decreasing cost of sequencing nucleic acids, especially massively parallel sequencing technologies, a large number of transcriptomic analyses of cone snail, snake, spider, scorpion, and a few other animal venom glands have been carried out [126, 127, 128, 129].

At present, high-throughput transcriptomics has been applied to 13 types of sea anemones: Anthopleura elegantissima, Anthopleura dowii, Aiptasia pallida, Anemonia sulcata, Anemonia viridis, Cnidopus japonicus, Exaiptasia pallida, Heteractis crispa, Oulactis sp., Megalactis griffithsi, Nematostella vectensis, Stichodactyla helianthus, and Stichodactyla haddoni [18, 46, 130, 131, 132, 133, 134, 135, 136, 137, 138]. There is a growing body of literature using transcriptomics data to study the symbiotic relationship between sea anemones and their symbionts or to study the mechanism of the evolutionary development of sea anemones [131, 139, 140]. Few studies have reported the transcriptome sequencing of sea anemone venom and identification of venom-related peptides and proteins, which can be used for their structural and functional analyses and venom evolution in the future (Table 4, Ref. [18, 46, 87, 109, 136, 135, 141, 142, 143]) [132, 136]. Tentacles are ideal for transcriptomics analysis because the number and level of transcripts encoded by sea anemone peptide neurotoxins from tentacles are much greater than those encoded by sea anemone peptide neurotoxins from other tissues [132]. The transcriptomics of sea anemone venom can describe the expression of sea anemone toxin and provide a useful method for rapid identification of putative sea anemone peptide sequences [46]. For example, Mitchell and his team used a transcriptomic strategy with Illumina RNA-seq sequencing platforms to study venom from the tentacles of the Oulactis sp. and compiled a venom-related component library of 398 putative venom-related peptides and proteins, including one putative actinoporin [136]. The venom composition across different tissues (tentacles, mesenterial filaments, and columns) in three species of sea anemone (Anemonia sulcata, Heteractis crispa, and Megalactis griffithsi) was used in a combined RNA-seq and bioinformatic approach by Macrander et al. [132]. Their tissue-specific transcriptome analyses showed that there are significant variations in the abundance of toxin-like genes across tissues and species, which provides a framework for the characterization of tissue-specific venom and other functionally important genes in this lineage of simple bodied animals in the future. In addition, Sebé-Pedrós et al. [144] performed whole-organism single-cell transcriptomics of Nematostella vectensis. Their study revealed cnidarian cell type complexity and provided insights into the evolution of animal cell-specific genomic regulation [144].

The first description of proteomics dates back to the early 1980s when Bravo and Celis developed protein separation by exceptionally effective 2D gel electrophoresis followed by Edman degradation sequencing to identify proteins and compare them to available protein sequence databases [145]. This, together with the wider availability of protein sequence databases, opened the door to the wide use of proteomics [146]. With the rapid development of analytical instruments and bioinformatics, proteomics has become a rapidly developing field and has shown to be applicable to many organisms and cell types [147, 148]. It has become an important tool for the study of animal venom, enabling detailed research of venom composition [149, 150, 151, 152].

Venom proteomics with modern mass spectrometry technology has proven to be an effective and high-throughput method for the discovery of novel sea anemone peptide neurotoxins [141, 153, 154]. To date, high-throughput proteomics have been used for sea anemones such as Bunodactis verrucosa, Nematostella vectensis, Stichodactyla duerden, Anthopleura dowii, and Stichodactyla haddoni, with an average of 321 proteins and peptide neurotoxins being identified in each sea anemone (Table 4) [18, 109, 141, 143, 153]. The first proteomic studies on the venom of sea anemone were performed by Zaharenko and colleagues, who investigated the peptide mass fingerprint and some novel peptides in the neurotoxic fraction of the sea anemone Bunodosoma cangicum venom. Their data showed that at least 81 molecules were eluted in the neurotoxic fraction and may be employed as active peptides for prey capture and defense [155]. In addition, a combination of offline RPC-MALDI-TOF and online nano-RPC-ESI-LTQ-Orbitrap proteomic techniques was used for Stichodactyla duerdeni by Cassoli and his team, which identified a total 67 proteins and peptides and revealed the presence of a novel O-linked glycopeptide [153]. Moreover, proteomics has also been applied to the model sea anemone Nematostella vectensis to more fully elucidate the molecular and cellular mechanisms underlying the repair of hair cells following trauma [156].

| Species | Sequencing platforms | Number of peptides and proteins found by transcriptomics | MS instruments | Number of peptides and proteins found by proteomics | Ref. |

| Oulactis sp. | Illumina HiSeq 1500 | 398 | [136] | ||

| Exaiptasia pallida | Illumina NextSeq 500 | 547 | [135] | ||

| Anthopleura elegantissima | Illumina HiSeq | 65 | [46] | ||

| Bunodactis verrucosa | - | - | MALDI-TOF/TOF | 412 | [141] |

| Cnidopus japonicus | - | - | LC-MS/MS | 27 | [142] |

| Nematostella vectensis | - | - | LC/MS | 1135 | [143] |

| Stichodactyla duerdeni | - | - | MALDI–TOF MS | 67 | [87] |

| Anthopleura dowii | Illumina | 261 | LC-MS/MS | 156 | [109] |

| Stichodactyla haddoni | Illumina NextSeq 500 | 508 | LC-MS/MS | 131 | [18] |

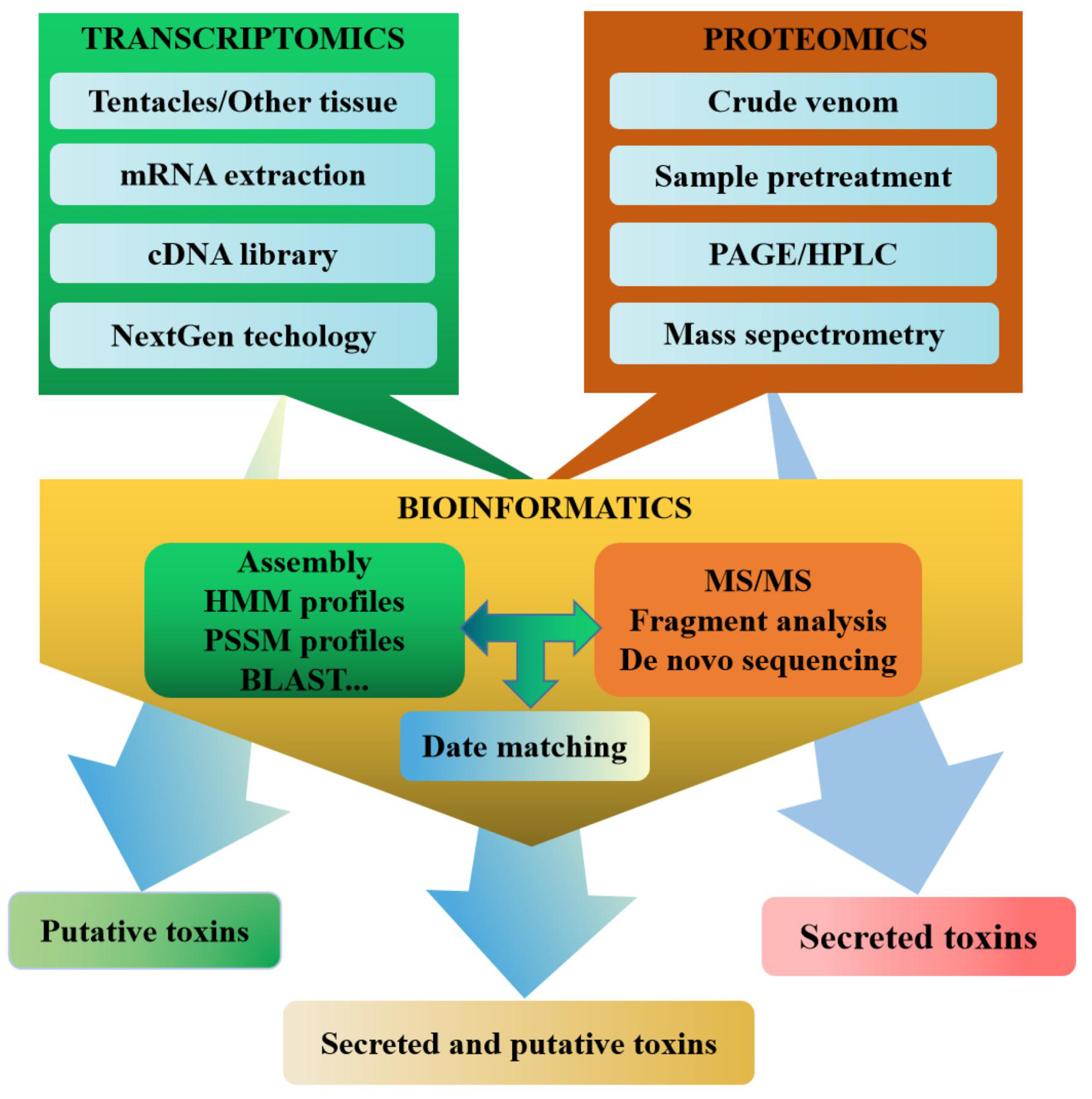

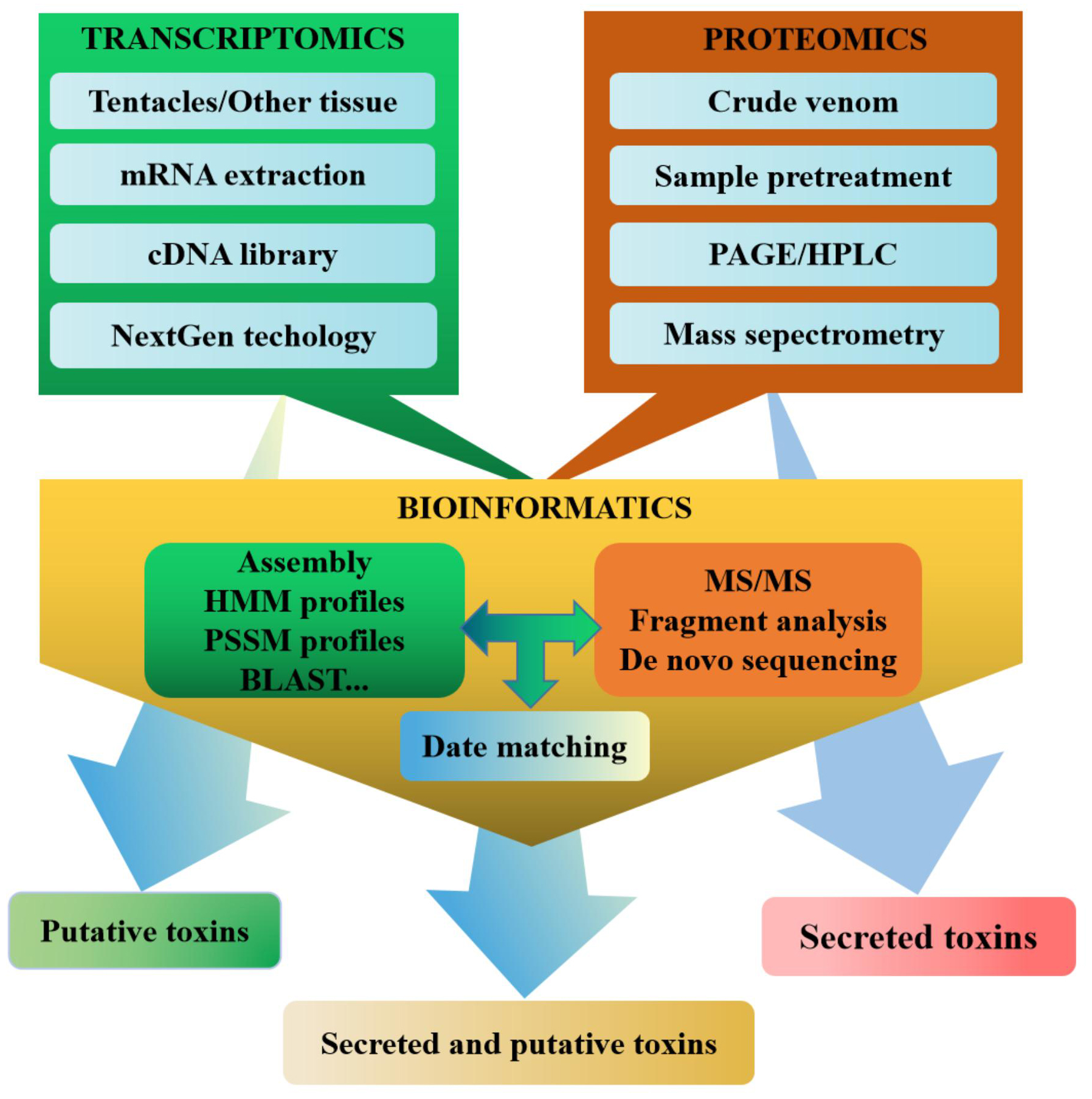

Multiomics has constructed a set of research strategies for sea anemone toxins based on integrated correlation analysis of transcriptomics and proteomics, which have been proven to be effective, and high-throughput methods to identify a large number of sea anemone toxin sequences (Fig. 3) [139, 141]. Both transcriptomics and proteomics benefit from the emergence and development of bioinformatics, especially the development of bioinformatics software, the improvement of algorithms, and the expansion of searchable databases [157, 158]. Bioinformatic tools such as BLAST, UniProt, PFAM, and others have frequently been used for venom transcriptomics and proteomics, playing an important role in raw data processing, sequence recognition, protein analysis, and superfamily classification [159].

Fig. 3.

Fig. 3.Multiomic approach to the discovery of sea anemone toxins.

Transcriptomics and proteomics are methods with limitations. Transcriptomics does not predicate post-transcriptional modifications or regulatory processes [28]. Proteomic techniques do not have the sensitivity to detect proteins with low abundance [29]. Therefore, multiomics technology combining transcriptomics and proteomics can effectively solve their respective limitations and can enrich the biological information from organisms. The multiomics techniques have enabled further exploration of the components of venomous animal species (scorpions, spiders, cone snails, and snakes) [160, 161, 162, 163], as well as sea anemone venom from a few species (Table 4) [18, 109]. Bruno Madio and colleagues used a combination of transcriptomics and proteomics to study Stichodactyla haddoni for the first time and identified 508 unique toxin transcripts, which were divided into 63 families. However, proteomic analysis of venom identified 52 toxins in these toxin families that might be false positives. In contrast, the combination of transcriptomic and proteomic data enabled positive identification of 23 families of putative toxins, 12 of which have no homology to known proteins or peptides [18]. In addition, Ramírez-Carreto and his colleagues also used a transcriptomic and proteomic analysis of the tentacles and mucus of the sea anemone Anthopleura dowii. Transcriptome analysis showed that 261 peptides were identified, while proteomic analysis identified 156 peptides. Some toxins identified in the tentacles and mucus proteome were not identified in the transcriptome [109]. In general, it was observed that the quantity and especially the diversity of probable toxins in the sea anemone transcriptome were far greater than those in the sea anemone proteome, which was similar to that in other venomous animals [164, 165].

Currently, transcriptomics and proteomics are considered to be effective, resource-saving, and high-throughput approaches for the discovery of novel sea anemone peptide neurotoxins. The multiomics approach is significantly more effective than the use of transcriptomics or proteomics alone. In the future, the application of multiomics technology in the development and utilization of sea anemone resources will accelerate the discovery of new sea anemone peptide neurotoxins and will continuously enrich and expand the database of sea anemone peptide neurotoxins.

At present, three experimental methods, X-ray crystallography, nuclear magnetic resonance (NMR), and cryoelectron microscopy (cryo-EM), are used to determine the three-dimensional structure of sea anemone toxins [166, 167, 168]. The X-ray crystallography technique can obtain high-precision protein structures. However, many proteins, especially small molecular peptides, cannot be determined by this method due to the difficulty of preparing crystals for structural analysis [166]. The advantage of NMR and cryo-EM is that there is no need to prepare protein crystals [169, 170]. NMR is mainly used to determine the structure of small molecular peptides, while cryo-EM is mainly used to determine the structure of macromolecular proteins [171, 172]. Therefore, NMR has played a prominent role in determining the three-dimensional structures of sea anemone peptide toxins because it is often used to analyze the structure of small molecular peptides. The three-dimensional structures of sea anemone peptide toxins determined by Solution NMR are summarized in Table 5 (Ref. [22, 29, 30, 167, 173, 174, 175, 176, 20, 177, 178, 179, 180, 181, 182, 183]).

| Species | Toxin | Type | Length (AA) | PDB ID | Ref. |

| Anemonia viridis | BDS-1 | K |

43 | 1BDS | [173] |

| Bunodosoma granulifera | BgK | K |

37 | 1BGK | [174] |

| Stichodactyla helianthus | ShK | K |

35 | 1ROO | [175] |

| Actinia tenebrosa | Ate1a | K |

18 | 6AZA | [29] |

| Oulactis sp | OspTx2b | K |

36 | 6BUC | [167] |

| Anthopleura elegantissima | APETx1 | K |

42 | 1WQK | [176] |

| Anthopleura elegantissima | APETx2 | K |

42 | 1WXN | [20] |

| ASIC channel | |||||

| Antopleura cascaia | AcaTx1 | K |

32 | 6NK9 | To be published |

| ASIC channel | published | ||||

| Stichodactyla helianthus | ShPI-1 | Kunitz type | 55 | 1SHP | [177] |

| proteinase | |||||

| inhibitor | |||||

| Anemonia viridis | ATX-IA | Na |

46 | 1ATX | [178] |

| Anemonia viridis | ATX-III | Na |

27 | 1ANS | [179] |

| Anthopleura xanthogrammica | Anthopleurin-A | Na |

49 | 1AHL | [180] |

| Anthopleura xanthogrammica | Anthopleurin-B | Na |

49 | 1APF | [181] |

| Condylactis gigantea | CgNa | Na |

47 | 2H9X | [182] |

| Stichodactyla helianthus | Sh1 | Na |

48 | 1SH1 | [183] |

| Urticina grebelnyi | Ugr 9-1 | ASIC3 channel | 29 | 2LZO | [22] |

| Urticina eques | Ueq 12-1 | TRPA1 channel | 45 | 5LAH | [30] |

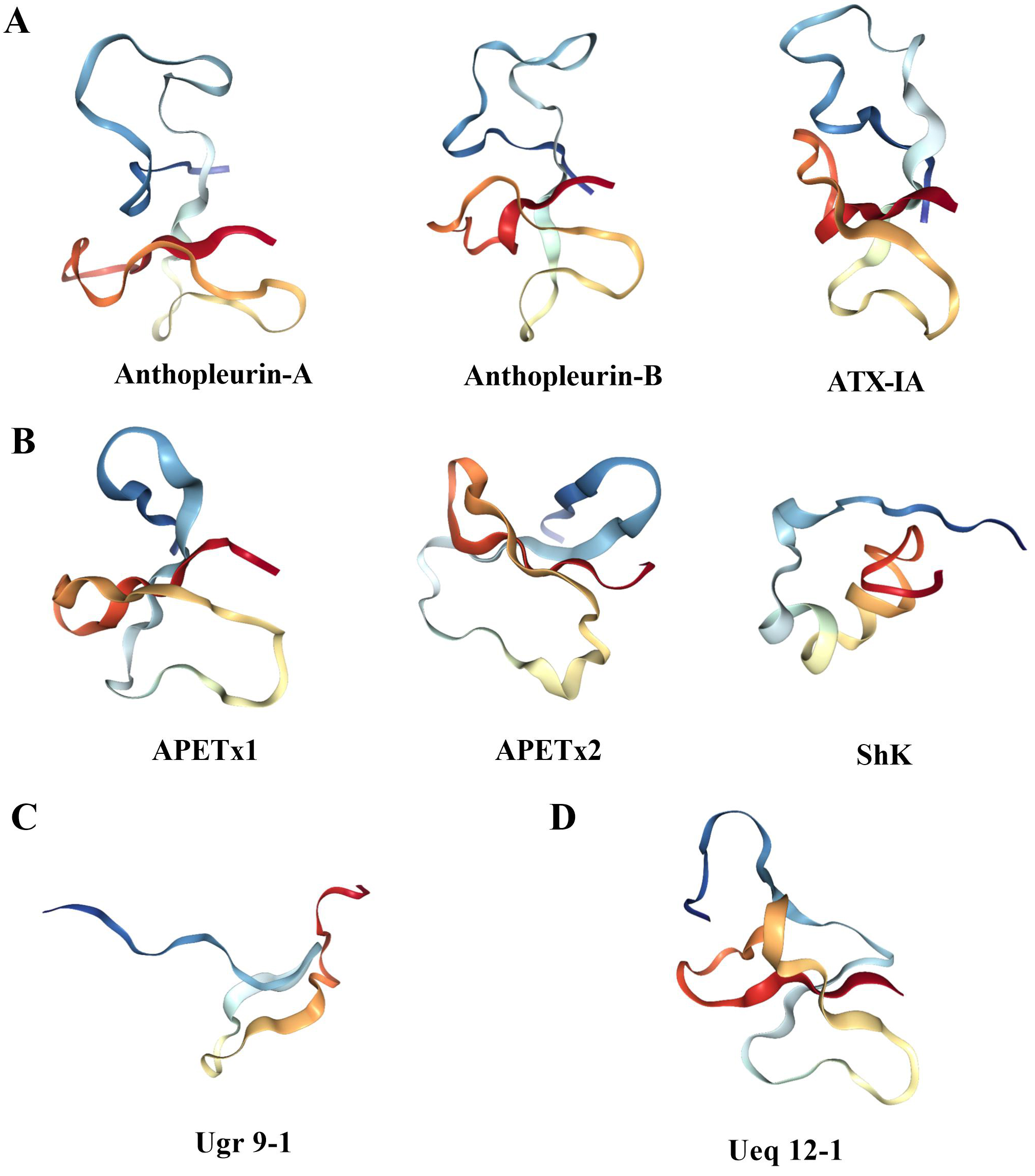

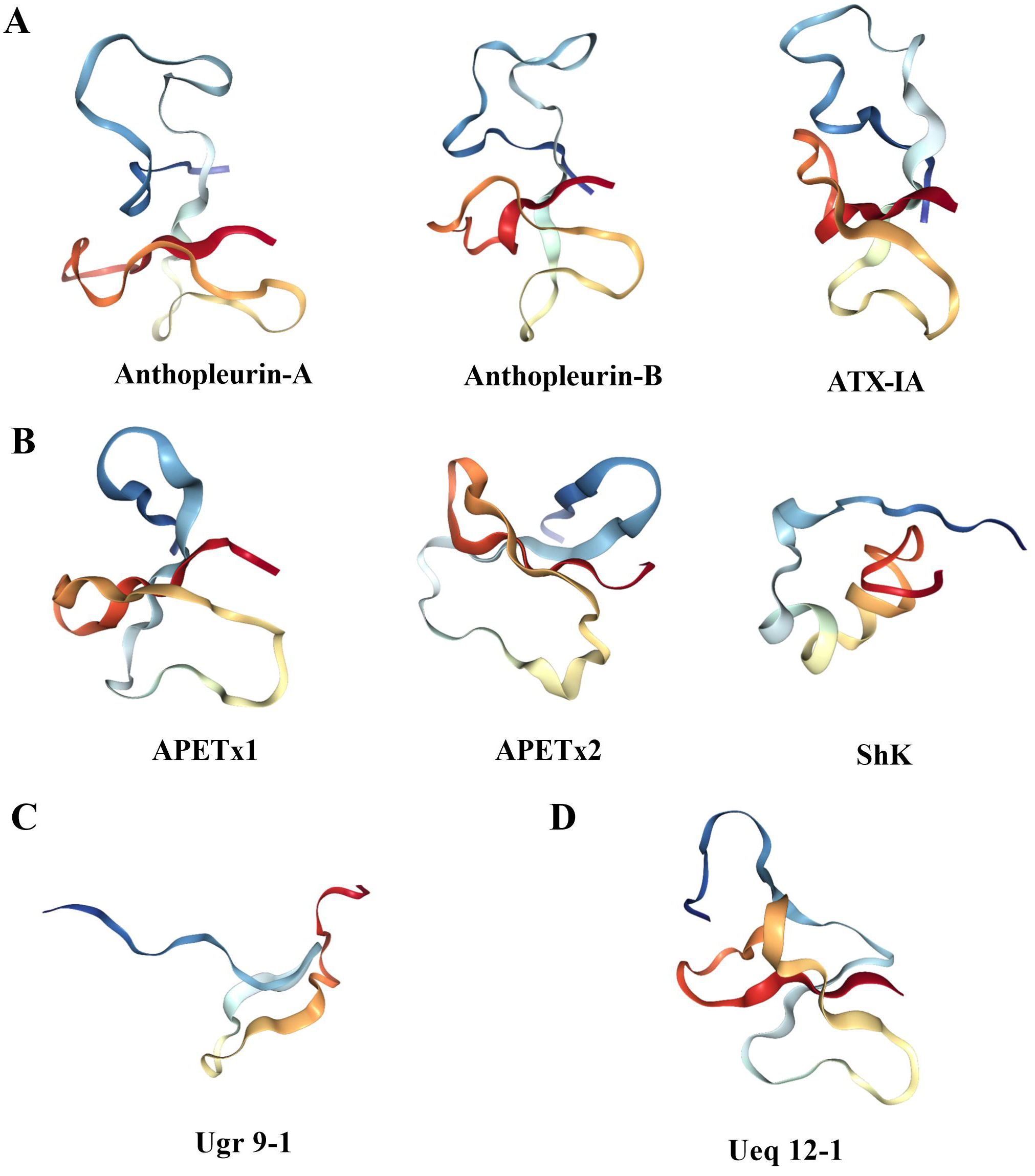

The first three-dimensional protein structures of sea anemones were obtained in

the 1980s by NMR analysis for Anthopleurin-A followed by ATX-IA [184, 178]. To

date, nine unique structural folds have been identified based on the

three-dimensional structure and/or cysteine-pattern: ShK, Kunitz-domain, ATX-III,

PHAB,

Sea anemone peptide toxins acting on the Na

Fig. 4.

Fig. 4.Three dimensional structure of sea anemone toxin. (A) The structure of Na

APETx1, APETx2, BDS-1, BgK, ShK, Ate1a, OspTx2b, AcaTx1, and ShPI-1 are examples

of toxins that inhibit the K

The ASIC3 channel toxin Ugr 9-1 with an uncommon

Ueq 12-1 isolated from sea anemones acts on the TRPA1 channel, and its

three-dimensional structure has been determined by NMR spectroscopy, which

represents a new stable disulfide fold, namely, SCRiPs (Fig. 4D). The

three-dimensional structure of Ueq 12-1 shows that SCRiPs are organized into a

peculiar W-shaped structure, the core of which is formed by a three-stranded

antiparallel

In this review, we described the discovery methods for novel peptide neurotoxins from various sea anemones. The traditional methods of crude venom purification and gene cloning can only discover a few known or novel sea anemone peptide neurotoxins in a low-throughput way. However, the transcriptomic, venom proteomic, and multiomic methods have high efficiency, resource-conserving, and high-throughput advantages and have opened a new era of novel sea anemone peptide neurotoxin discovery. Finally, the three-dimensional structure types and corresponding action targets of sea anemone peptide neurotoxins were summarized, which provide a theoretical basis for marine drug research and development.

BG conceived and designed the article; LY and JF collected the data; JF wrote the article, while BG and AHJ revised the article.

Not applicable.

We thank Yang Tao for helping to improve and beautify the pictures. Thanks to all the peer reviewers for their opinions and suggestions.

This work is supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (82060686) and Hainan Provincial Natural Science Foundation of China (820RC636).

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

PLA2, phospholipase A2 enzymes; Na