Frontiers in Bioscience-Landmark (FBL) is published by IMR Press from Volume 26 Issue 5 (2021). Previous articles were published by another publisher on a subscription basis, and they are hosted by IMR Press on imrpress.com as a courtesy and upon agreement with Frontiers in Bioscience.

Retraction of Frontiers in Bioscience-Landmark 2025, 30(2)

1 Department of Emergency, The Affiliated Huaian No.1 People’s Hospital of Nanjing Medical University, Huai’an, Jiangsu 223300, P.R. China

Abstract

Acute lung injury (ALI) is a life-threatening condition caused by severe inflammation of lung tissues. We hypothesized that lipopolysaccharide induced acute lung inflammation and injury in mice might be controlled by lonicerin (LCR), a plant flavonoid that impacts immunity, oxidative stress, and cell proliferation. LCR reduced pathological changes including pulmonary edema, elevation of protein in bronchoalveolar lavage, inflammation, pro-inflammatory gene expression, expression of toll-like receptor 4/nuclear factor-kappa B, apoptosis, and significantly reduced mortality. Together, the results suggest that LCR might be a potential and effective candidate for the treatment of ALI that acts by inhibiting inflammation and apoptosis.

Keywords

- Acute lung injury

- ALI

- Lonicerin

- LCR

- lipopolysaccharide

- LPS

- Inflammation

- Apoptosis

Acute lung injury (ALI) or acute respiratory distress syndrome is an inflammatory response to both pulmonary and extra-pulmonary stimuli, characterized by acute onset of new or worsening respiratory dysfunction (1,2). Despite advances in intensive care with optimal ventilation support, ALI is still a devastating condition with a high mortality rate of approximately 40% (3). Although the pathogenesis of ALI is complex, the inflammatory response and apoptosis imbalance play important roles in the progression of the condition (4-6). Thus, therapeutic strategies aimed to suppress inflammation and apoptosis might be effective.

Flavonoids are natural polyphenols present in many vegetables and fruits (7), and have attracted attention owing to their bioactivities, including anti-inflammation, anti-apoptosis, anti-proliferation, and anti-oxidation activities, to prevent different types of diseases (8,9). Flavonoids have been proved therapeutically effective against renal, liver, heart, and lung injuries, induced by different stimuli (10-13). Lonicerin (LCR) is a flavonoid isolated from Lonicerae Flos (14), which can regulate immunity, cell proliferation, and oxidative stress. Production of the synthetic version of lonicerin is simple, feasible, economic, and convenient for manufacturing at industrial scale (15). In mice, LCR has been proved effective in treating fungal arthritis, a common inflammatory arthropathy (16). Considering that the inflammatory response plays an essential role in lipopolysaccharide (LPS)-induced ALI, we hypothesized that LCR will be effective in treating the condition. Literature search revealed that no published studies assessed the therapeutic role of LCR in ALI. Thus, we attempted to explore the effects of LCR on ALI and study the underlying molecular mechanisms, providing new insights into the prevention and/or treatment of ALI.

Previous reports have indicated that the pro-inflammatory cytokines, including interleukin-1 beta (IL-1β), interleukin-18 (IL-18), interleukin-6 (IL-6), and tumor necrosis factor-alpha (TNF-α), are important in inducing pulmonary inflammation (17, 18). Apoptosis is a process of controlled cellular death, wherein the activation of specific death-signaling pathways leads to deletion of cells (19). These death-signaling pathways can be activated in response to receptor–ligand interactions, environmental factors such as ultraviolet light and redox potential, and internal factors that are encoded in the genome (20, 21). Eventually, apoptosis leads to fragmentation of DNA, reduction in cell volume, and its phagocytosis by nearby phagocytes (22). Abnormal activation or suppression of apoptosis could lead to diseases in humans either due to early death of heathy cells or prolonged survival of unhealthy cells (23). In addition, phagocytosis of several apoptotic cells, such as neutrophils, could trigger alterations in the activation phenotype of lung macrophages (24). Furthermore, the main feature of ALI includes the destruction of alveolar epithelium and severe damage to the alveolar capillary barrier, increasing the alveolar capillary permeability to a large extent (25). Thus, targeting the inhibition of apoptosis is essential to find new therapeutic strategies.

In the present study, LCR significantly reduced LPS-induced pathological issues, pulmonary edema, and protein in bronchoalveolar lavage fluid (BALF). Hence LCR might be a new and effective candidate in treating ALI.

Male C57BL/6 mice, 6 weeks old and weighing 18–20 g, were obtained from the Experimental Animal Center of Chinese Academy of Sciences in Shanghai (Shanghai, China) and provided with water ad libitum and food, and maintained in climate-controlled quarters with 12/12 h light/dark cycle under germ-free conditions at 25°C. The mice were housed for a week to adapt to the environment and then were randomly divided into five groups (n = 15 in each group): i) Control (Con) group; ii) LPS group; and iii) LCR-treated groups (10, 20, and 30 mg/kg, indicated as LCR1, LCR2, and LCR3, respectively). LCR (HPLC ≥ 98%) was purchased from Baomanbio (Shanghai, China), and was intraperitoneally injected to the respective LCR group mice, once a day at the above mentioned concentrations, for 3 consecutive days. Mice in the Con and LPS groups received an equal volume of normal saline. On the third day, three hours after LCR/saline administration, the mice were anesthetized with diethyl ether (6.5%) inhalation, and lung injury was induced in LPS and LCR group mice by administering 10 µg of LPS (in 50 µl PBS) through intranasal route. Mice in the Con group were administered 50 µl normal saline without LPS. The mice were then monitored for seven days, after which all mice were euthanized by intraperitoneal injection of pentobarbital (50 mg/kg; Sigma Aldrich, USA), which was incubated at 37°C for 1 h. Just before euthanasia, using tracheal cannula, chilled PBS was introduced into the lungs three times and the bronchoalveolar lavage fluid (BALF) was collected. Post euthanasia, lung tissue was also harvested for assessments. The middle lobe of the right lung was excised, the wet and dry (by incubating at 80°C for 24 h) weight of which was measured to establish the wet/dry weight ratio. The procedures were approved by the Research Ethical Committee of Huai'an First People’s Hospital, Nanjing Medical University (Nanjing, China). All procedures were in accordance with the Regulations of Experimental Animal Administration issued by the Ministry of Science and Technology of the People’s Republic of China.

The human lung epithelial cell line BEAS-2B, purchased from American Type Culture Collection (Rockville MD, USA), were cultured in DMEM/F12, supplemented with 1% penicillin/streptomycin and 10% FBS (Hyclone, USA), and incubated at 37°C under 5% CO2 and 95% humidity. Pulmonary microvascular endothelial cells (PMVECs) were isolated from lung microvessels of male Sprague-Dawley rats by following previously reported protocol (26,27). Briefly, 150–200 g of harvested rat lung tissue was cut into 1mm2 pieces and digested using collagenase and trypsin. Post centrifugation, the obtained cells were seeded in gelatin-coated 25cm2 flasks, and cultured in DMEM containing 15% FBS, 2% endothelial cell growth supplement (ECGS 100 U/ml), and 1% penicillin/streptomycin (P/S) solution at 37°C in an incubator containing 5% CO2 and 95% humidity. The cells were then confirmed of their phenotype based on the morphology and expression of PECAM-1/CD31 (BD Biosciences, USA). Human pulmonary microvascular endothelial cells (ScienCell, USA) were cultured in endothelial cell medium (ScienCell) containing FBS, ECGS, and P/S. For experiments, the cells (between passages 4 and 10) were grown as a monolayer and serum starved (1% serum) for 6 h before each treatment.

Cells were seeded in 96-well plates at a density of 2×104 and 3×104 cells/well and incubated for 24 h at 37°C. Cell culture media were then replaced by complete media containing the indicated concentrations (0–160 μM) of LCR and incubated for 96 h. After incubation, 10 μl of MTT (KeyGen BioTech, Nanjing, China) was administrated to cells, followed by incubation for 4 h at 37°C, as per the manufacturer’s instruction. Later, the absorbance was read at 570 nm, using a microplate reader, and the data was evaluated to assess the cell viability (%).

IL-1β, IL-6, and TNF-α level in the serum and BALF were assessed using ELISA kits (R&D system, USA), following manufacturer’s instructions.

The collected BALF samples were centrifuged at 1,000 ×g for 10 min at 4°C, and the cell pellet was re-suspended in PBS. The total BALF cells were enumerated using a hemocytometer. The cells were then cytospun onto a microscope slide and stained for CD-68 positive macrophages (immunofluorescence) and Wright-Giemsa (Sigma Aldrich, USA) for cell classification. The percentage of BALF polymorphonuclear leukocytes (PMNs) and macrophages (MACs) was obtained by counting the leukocytes under a light microscope (Nikon, Japan).

Cells were harvested after various treatments and stained using the Annexin V/PI Cell Apoptosis Detection Kit (KeyGen Biotech, China), following the manufacturer’s instructions. Data acquisition and analysis were performed using a Becton Dickinson FACS Calibur flow cytometer with Cell-Quest software. The cells in the early stages of apoptosis were Annexin V positive and propidium iodide (PI) negative, whereas those in the late stages of apoptosis were both Annexin V and PI positive.

Total RNA from cells and lung tissue samples was extracted using Trizol Reagent (Invitrogen, USA), as per the manufacturer’s instructions. They were quantified and subjected to reverse transcription to prepare cDNA by RevertAid First Strand cDNA Synthesis Kit (Thermo Scientific Fermentas, USA). PCR was performed on a CFX96 Real-Time System (Bio-Rad Laboratory, USA). The primer sequences were commercially synthesized and are listed in table 1. Fold changes in the mRNA levels of the target gene relative to the endogenous cyclophilin control were calculated. Briefly, the cycle threshold (=Ct) values of each target gene were subtracted from the Ct values of the housekeeping gene cyclophilin (ΔCt). Target gene ΔΔCt was calculated as ΔCt of target gene minus ΔCt of the control. The fold change in the mRNA expression was calculated as 2−ΔΔCt.

| Primers | Forward | Reverse |

|---|---|---|

| IL-1ß | CTT GCG CGT TGT TTG CCG CTT CG | TGG GTC GCG GGT GAT TGG ATC GT |

| TNF-α | CTG GTC TTG GTG TCT CGC TTC CTG | GGC TGG CTC AGT GAG GGT TGA CT |

| IL-6 | CTA TGA CCA GGC TGC ATT CCT ATG | GTT GGC GCT GTG ATG TTA GAC T |

| GAPDH | CTG ACG AAG GAC AAT GAG TGC ACA GCG C | ATT CCA CAT CAC AAG ACT TCG CTC AGC C |

Approximately 100 mg of lung tissue was lysed with 1 ml of lysis buffer. After treatment under different conditions, the harvested cells were lysed in ice-cold lysis buffer in the presence of fresh protease inhibitor cocktail. The lysates were then centrifuged at 15,000 ×g for 15 min at 4°C to collect the supernatant. The BSA protein assay kit was used to detect the protein concentrations as per the manufacturer’s instructions (Thermo, USA). The protein extracts were separated by 10% SDS-PAGE and were then transferred to polyvinylidene fluoride (PVDF) membrane (Millipore, USA). PVDF was then treated with 5% skim-fat dry milk, in 0.1% Tween-20 in Tris-buffered saline (TBS), for 2 h to block the non-specific sites on the blots. The target protein blots were detected by incubating the PVDF membrane with primary antibodies, at 4°C overnight. The primary antibodies used in our study are as follows: rabbit anti-NF-κB/p65 (1:1000, #3039, Cell Signaling Technology, USA), TLR4 (1:1000, ab13556, Abcam), MD2 (1:1000, ab24182, Abcam), caspase-3 (1:1000, ab13847, Abcam), PARP (1:1000, ab32064, Abcam), Bax (1:1000, ab32503, Abcam), Bcl-2 (1:1000, ab32124, Abcam), and GAPDH (1:2500, ab9485, Abcam). The bands on PVDF were covered by chemiluminescence with Pierce ECL Western Blotting Substrate reagents (Thermo Scientific, IL). All experiments were independently performed in triplicates.

The harvested lung tissue samples were fixed using 4% formalin, and embedded in paraffin. The tissues were then sectioned and subjected to Hematoxylin and Eosin (H&E) (Sigma Aldrich) staining to quantify morphological changes in the lungs. The extent of histological changes was graded from 0 (no alteration in lung structure) to 5 (severe injury of lung structure). The sections were also immunostained with primary antibodies against caspase-3 (Abcam, USA), by incubating at 4°C overnight. The cultured cells, after various treatments, were subject to immunofluorescent staining. Briefly, the cells were washed three times with chilled PBS and fixed with 3.7% (v/v) formaldehyde in PBS for 15 min. The specimens were then permeabilized for 5 min using 0.1% Triton X-100. For p-NF-κB staining, the cells were treated with mouse anti-p-NF-κB antibody (50 μg/ml) for 2 h. Then, they were stained with anti-mouse secondary antibody for 30 min, followed by washing with PBS three times. The sections were then mounted with Prolong Gold anti-fade reagent using 4′,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole (BeyoTime, Shanghai, China) for 5 min. Images were acquired by confocal laser scanning via epifluorescence microscopy (Nikon, Japan). The number of p-NF-κB-positive cells was determined per field (230 μm × 184 μm, at least five fields were chosen randomly) for each animal, following cell body recognition using Image Quant 1.43 program (NIH).

Data were expressed as mean ± SEM. Treated cells, tissues, and the corresponding controls were compared using Graph Pad PRISM (Graph Pad Software, USA) by one-way ANOVA with Dunn’s least significant difference tests. The differences between groups were considered significant at a p value of <0.05.

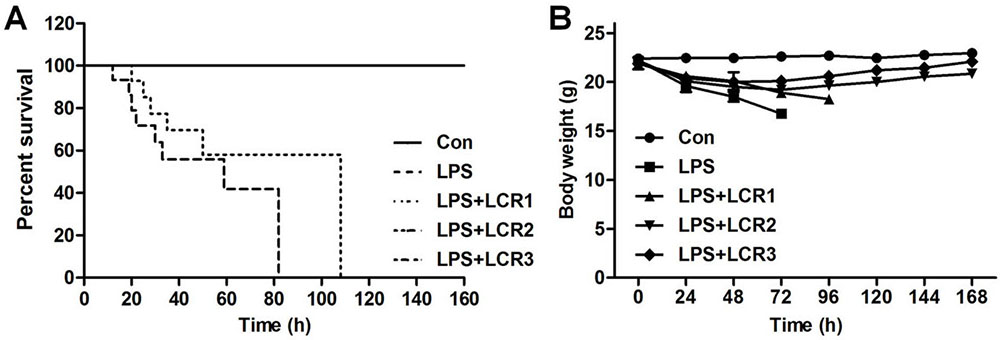

Post LPS inhalation, the survival rate and body weight of mice were recorded every 24 h. As shown in Figure 1A, the mice treated with LPS alone died within 4 days of exposing to LPS, while those pre-treated with 10 mg/kg of LCR died within 5 days. However, the mice pre-treated with 20 and 30 mg/kg of LCR survived through the study period. Simultaneously, in response to LPS treatment, all the mice progressively lost weight during the first 3 days, which was continued to fourth day in the LCR1 group mice. However, mice in LCR2 and LCR3 group gradually regained near normal weight, compared to control group mice, over the following days (Figure 1B). These results indicate that the LCR plays a protective role against LPS-induced ALI.

Figure 1

Figure 1Lonicerin alleviates LPS-induced septic shock in mice. (A) C57BL/6 mice were pre-treated with LCR (10, 20, and 30 mg/kg) daily for three days prior to LPS injection. The survival rate was monitored for 7 days at an interval of 24 h post LPS treatment. (B) The body weight of mice was recorded for 7 days at an interval of 24 h post LPS treatment.

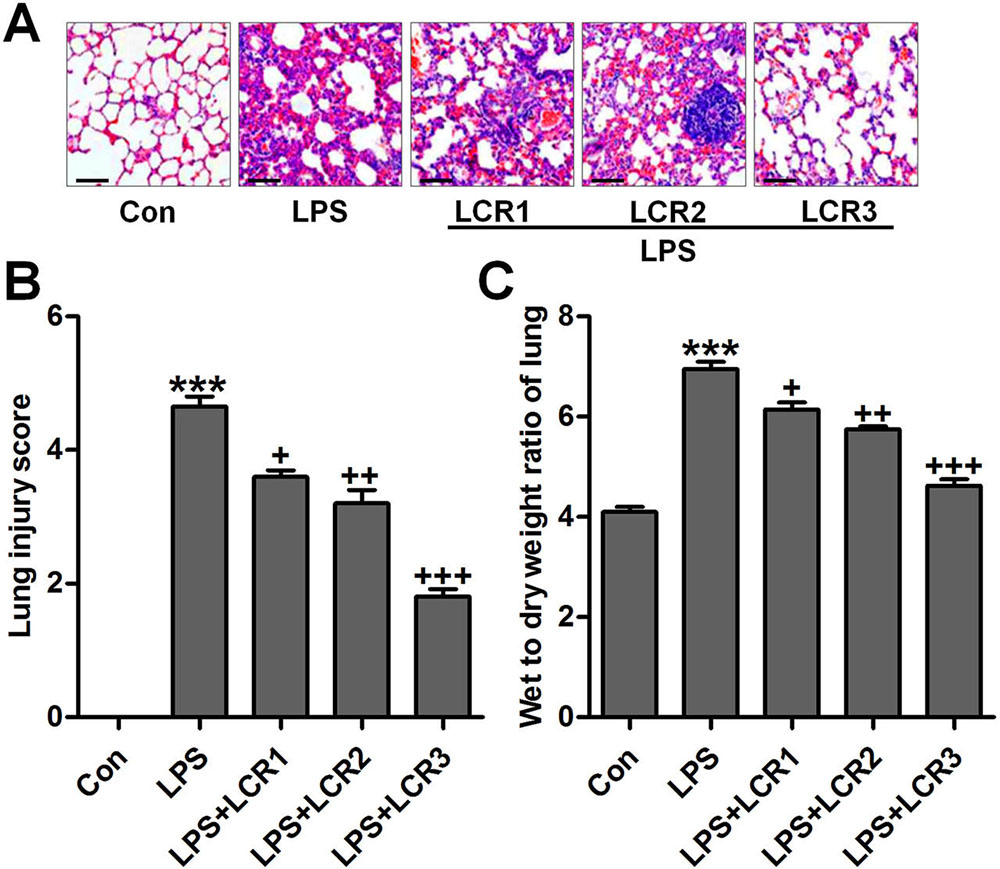

In response to LPS-induced ALI, mice exhibited severe infiltration of inflammatory cells in the lung alveolar spaces and interstitium. However, the number of infiltrated inflammatory cells significantly declined in response to LCR pre-treatment, in a dose-dependent manner. Further, LCR also alleviated LPS-induced histochemical alterations in mice lungs (Figure 2A and B). In addition, we also measured the wet/dry weight ratio of the mice lung tissues, as an indicator of lung edema. As suggested in Figure 2C, LPS-induced a severe lung edema in mice, as evidenced by the increased lung wet/dry weight ratio, which was significantly reduced by LCR pre-treatment.

Figure 2

Figure 2Lonicerin attenuates histochemical changes of lung tissues induced by LPS in mice with ALI. (A) The representative images of histological changes evaluated by H&E staining. (B) The quantification of lung injury scores following H&E staining. (C) Lung wet/dry weight ratio. SEM of three independent experiments (n = 8). ***p < 0.001 versus the Con group; +p < 0.05, ++p < 0.01, and +++p < 0.001 versus the LPS group.

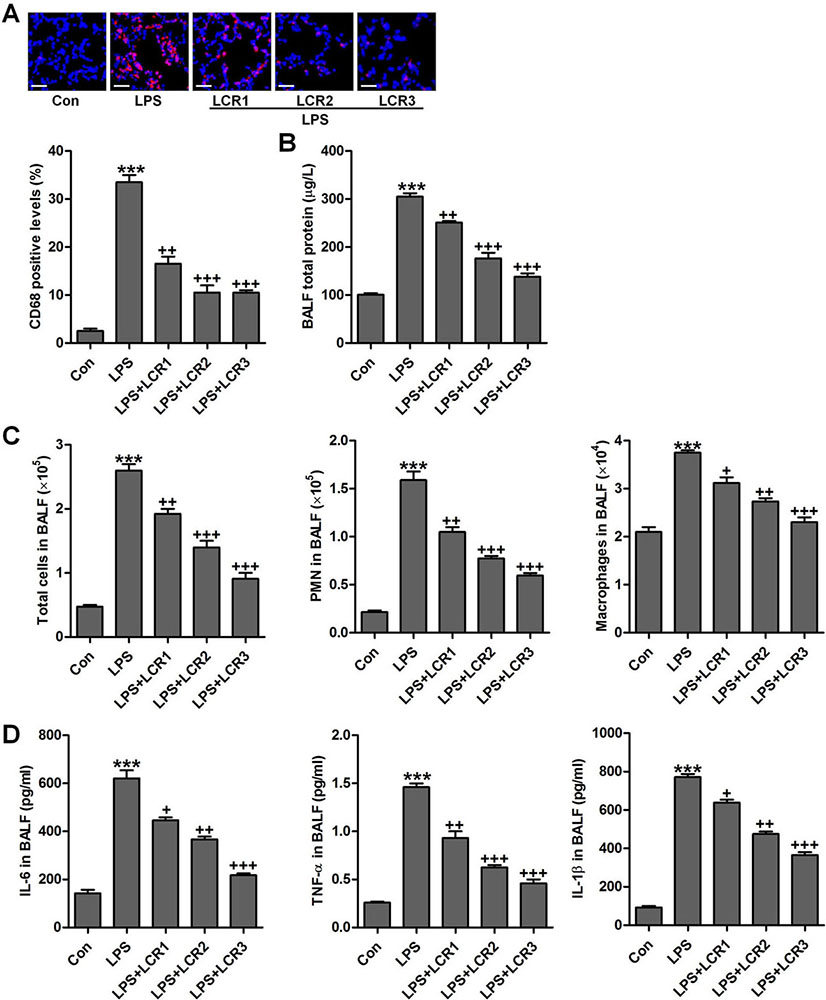

The protein concentration in BALF represents the alveolar-capillary barrier damage. CD68 positive macrophages, a hallmark of inflammatory infiltration, were assessed using immunofluorescence analysis (28), which indicated that LCR markedly suppressed macrophage infiltration in LPS-exposed mice lungs, in a dose dependent manner (Figure 3A). Further, LCR pre-treatment also attenuated the LPS-induced alveolar-capillary barrier damage, in dose dependent manner, as evidenced by a significant reduction in the total protein concentration in BALF of respective group mice (Figure 3B). LPS exposure resulted in an increased influx of total cells, polymorphonuclear leukocytes (PMNs), and macrophages, which significantly reduced after LCR administration (Figure 3C). Furthermore, increased levels of pro-inflammatory cytokines, IL-6, TNF-α, and IL-1β, were observed in BALF of LPS exposed mice, which was otherwise found significantly lowered in the BALF of LCR pre-treated mice (Figure 3D). Thus, the data above indicated that the LCR could suppress the LPS-induced inflammatory infiltration in mice lungs.

Figure 3

Figure 3Lonicerin inhibits the inflammatory infiltration as measured in BALF of LPS-treated mice. (A) The immunofluorescence analysis of CD68-positive levels in lung tissue sections, and quantification based on immunofluorescence is presented. (B) Total protein levels in BALF were examined. (C) The number of total cells, polymorphonuclear leukocytes (PMNs) and macrophages (MACs) in BALF were tested. (D) The levels of pro-inflammatory cytokines, IL-6, TNF-α, and IL-1β, in BALF; SEM of three independent experiments (n = 8). ***p < 0.001 versus the Con group; +p < 0.05, ++p < 0.01, and +++p < 0.001 versus the LPS group.

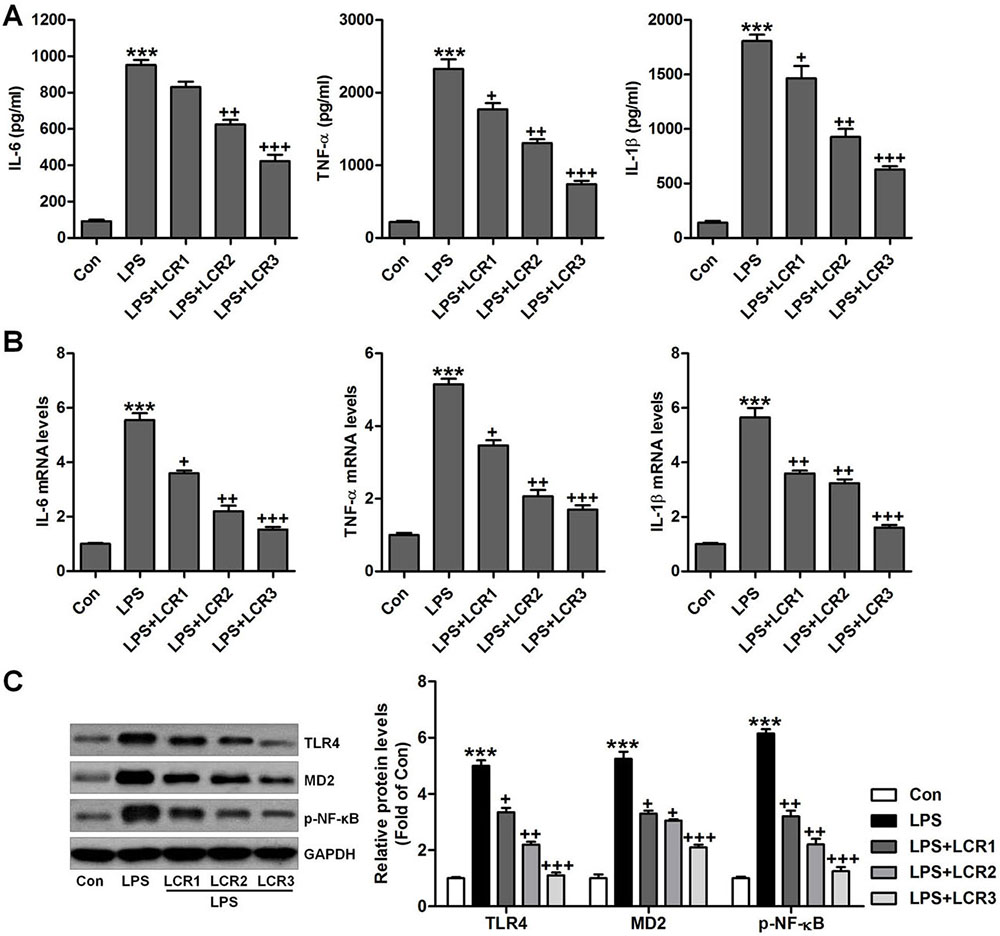

We further investigated the anti-inflammatory role of LCR in LPS-exposed mice. In LPS exposed mice, we found that the serum levels of IL-6, TNF-α, and IL-1β was dramatically increased, which was otherwise significantly attenuated by LCR pre-treatment, in a dose dependent manner (Figure 4A). Additionally, LCR pre-treatment also diminished the LPS-induced increased mRNA levels of IL-6, TNF-α, and IL-1β, in mice lung tissue samples (Figure 4B). The TLR4/NF-κB signaling pathway plays an important role in inducing inflammation. As shown in Figure 4C, western blot analysis revealed that the LPS-induced dramatically-increased expression of TLR4, MD2, and p-NF-κB were significantly reduced by LCR pre-treatment, in a dose dependent manner. The above data substantiates the LCR exhibited protection against LPS-induced ALI in mice, by inhibiting inflammation through inactivation of the TLR4/NF-κB pathway.

Figure 4

Figure 4Lonicerin suppresses inflammatory response in LPS-induced ALI mice. (A) Serum pro-inflammatory cytokines, IL-6, TNF-α, and IL-1β were determined using ELISA. (B) RT-qPCR analysis was performed to calculate IL-6, TNF-α, and IL-1β gene levels in lung tissue samples. (C) Western blot analysis was conducted to evaluate TLR4, MD2 and p-NF-κB protein levels in the lung tissue samples. SEM of three independent experiments (n = 8). ***p < 0.001 versus the Con group; +p < 0.05, ++p < 0.01, and +++p < 0.001 versus the LPS group.

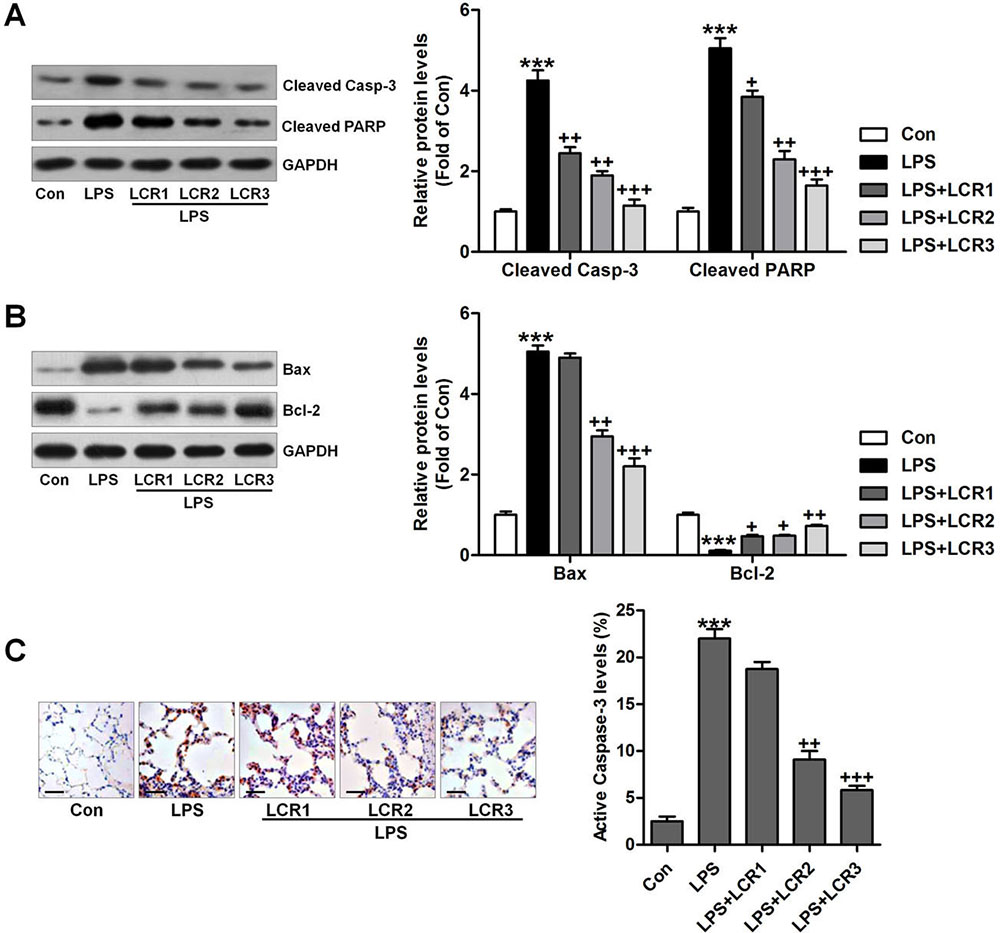

Cellular apoptosis has been reported to occur in LPS-induced ALI (24,29), and caspase-3/PARP plays an essential role in triggering such apoptosis (30). Western blot analysis indicated that the LPS could considerably induce caspase-3 and PARP cleavage in mice lungs, which was significantly attenuated by LCR pre-treatment (Figure 5A). Furthermore, the effect of LPS on Bax and Bcl-2 expression in mice lungs was also mitigated by LCR pre-treatment (Figure 5B). Immunohistochemical analysis further confirmed the inhibitory role of LCR in regulating active caspase-3 activity level by LPS (Figure 5C). Taken together, the results indicate that the LCR mediated reduction in LPS-induced ALI is also associated with inhibition of cellular apoptosis, in mice.

Figure 5

Figure 5Lonicerin alleviates apoptosis in LPS-induced ALI mice. (A) Cleaved caspase-3 and PARP levels in lung tissue samples were measured using immunoblotting assays. The quantification of active caspase-3 and PARP is presented. (B) Western blot analysis of Bax and Bcl-2. (C) Active caspase-3 in lung tissue sections was measured by immunohistochemical analysis. SEM of three independent experiments (n = 8). ***p < 0.001 versus the Con group; +p < 0.05, ++p < 0.01, and +++p < 0.001 versus the LPS group.

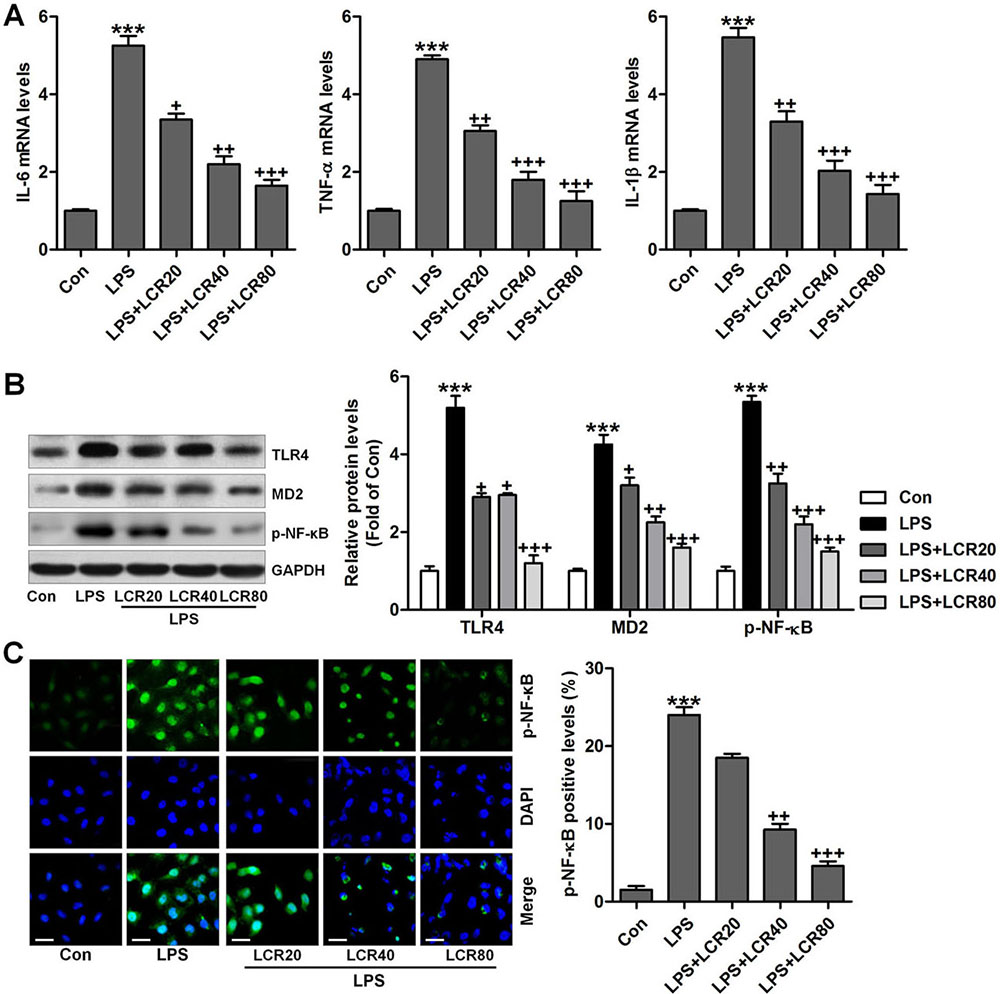

To further confirm the anti-inflammatory role of LCR in ALI, an in vitro study was conducted. First, the cell viability was measured using MTT analysis, to calculate the cytotoxicity of LCR on lung epithelial and microvascular cells. At the assessed concentrations, LCR did not affect the viability of BEAS-2B cells and PMVECs, in vitro (data not shown). BEAS-2B cells were pre-treated with LCR at the indicated doses for 24 h, followed by LPS stimulation for further 2 h. All the cells were then harvested for further study. As shown in Figure 6A, RT-qPCR analysis indicated that the gene levels of pro-inflammatory cytokines, including IL-6, TNF-α, IL-1β, were significantly elevated in the LPS-treated cells, while, LCR pre-treatment regulated this elevation in a dose-dependent manner. Further, the LPS-induced increased cellular expression of TLR4, MD2, and p-NF-κB, which are known to lead and participate in inflammatory response (29), was also dose-dependently regulated by LCR (Figure 6B). Finally, immunofluorescence analysis showed that the LCR pre-treatment led to significant reduction in the number of p-NF-κB expressing cells compared to LPS alone treated cells (Figure 6C). Together, the findings suggest that LCR has anti-inflammatory effects on LPS-induced ALI, in vitro.

Figure 6

Figure 6Lonicerin reduced inflammatory response in vitro. BEAS-2B cells were pre-treated with LCR (20, 40, and 80 μM) for 24 h and then exposed to LPS (100 ng/ml) for 2 h, followed by further experiments. (A) IL-6, TNF-α, and IL-1β gene levels were measured by the RT-qPCR analysis. (B) Western blot analysis of TLR4, MD2, and p-NF-κB in cells treated under the indicated conditions. (C) Immunofluorescence analysis was used to calculate p-NF-κB levels in cells, and the quantification of p-NF-κB is exhibited. SEM of three independent experiments (n = 6). ***p < 0.001 versus the Con group; +p < 0.05, ++p < 0.01, and +++p < 0.001 versus the LPS group.

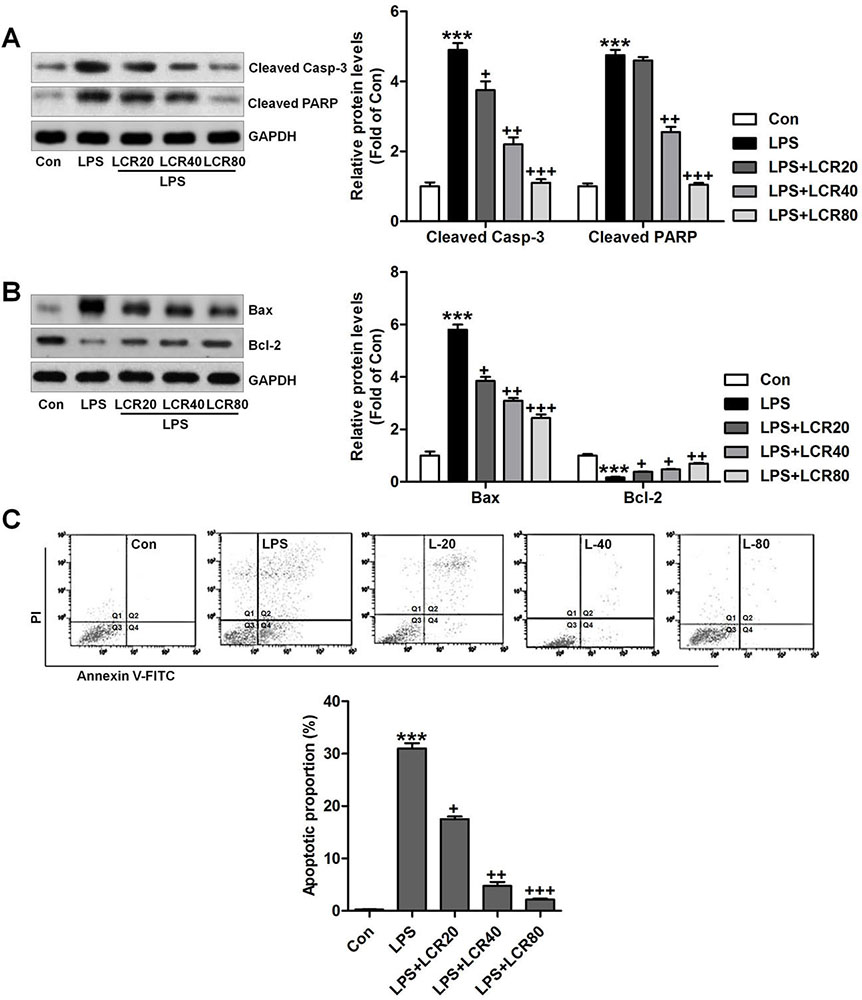

To further assess the effects of LCR on the regulation of apoptosis in vitro, the respective changes in the expression of cleaved caspase-3 and PARP in BEAS-2B cells were measured using western blot analysis. Figure 7A indicated that LPS led to increased expression of cleaved caspase-3 and PARP, which were notably regulated by LCR pre-treatment. Further, similar to in vivo results, LCR also reversed the effect of LPS on Bax and Bcl-2 expression in BEAS-2B cells (Figure 7B). Thus, LCR pre-treatment could block the LPS-induced activation of apoptosis pathway. Additionally, flow cytometry further confirmed our findings that LCR could suppress LPS-induced apoptosis in lung epithelial cells, in vitro (Figure 7C).

Figure 7

Figure 7Lonicerin blocks apoptosis in LPS-treated cells in vitro. BEAS-2B cells were pre-treated with LCR for 24 h, followed by LPS exposure for 2 h. Then, (A) cleaved Caspase-3 and PARP levels in cells were measured using Western blot analysis. (B) The immunoblotting analysis was used to calculate the Bax and Bcl-2 protein levels in cells. (C) Flow cytometry was performed to measure apoptotic proportion in BEAS-2B cells treated as indicated. The percentage of apoptosis was displayed. SEM of three independent experiments (n = 6). ***p < 0.001 versus the Con group; +p < 0.05, ++p < 0.01 and +++p < 0.001 versus the LPS group.

ALI is an inflammatory response to both pulmonary and extra-pulmonary stimuli, characterized by acute onset of respiratory dysfunction (1, 2). Even though there has been progress in understanding the molecular mechanisms underlying the pathogenesis of the disease, no therapies have been shown to improve mortality to date. Here we explored the effects of LCR in LPS-induced ALI murine models and the underlying molecular mechanisms involved in ALI progression. Our study indicated that LCR could protect mice from LPS-induced mortality, especially at higher concentrations. Furthermore, LCR exhibited a significantly protective effect on the mice lungs, as evidenced by the observed histological changes. Further, the LPS-induced increased infiltration of inflammatory cells was also suppressed by LCR, accompanied with reduction in secretion of pro-inflammatory cytokines. In addition, the inflammatory response observed in LPS-exposed mice and in lung epithelial cells was also suppressed by LCR, as evidenced by down-regulated pro-inflammatory cytokines and inactivated TLR4/NF-κB pathway. Apoptosis was found induced by LPS, confirming that LPS could induce cell death to aggravate lung injury. Of note, in such condition, LCR could suppress apoptosis by blocking caspase-3 and PARP cleavage. Therefore, LCR could be a novel flavonoid with therapeutic potential to attenuate ALI. However, further research is still required to comprehensively reveal the underlying molecular mechanism by which LCR prevents ALI and to assess whether it could be combined with other drugs or natural compounds to enhance their efficacy.

Macrophages are reported to be the major inflammatory and immune effector cells (31-33). They play an essential role in regulating inflammatory responses when stimulated with pathogens (34, 35). Polymorphonuclear leukocytes (PMNs) are essential components of the host defense and innate immune systems (36). As described previously, increased number of PMNs at the sites of inflammation could attenuate organ integrity because PMNs, in large numbers, have the potential to further weaken the injured tissue (37, 38). In the current study, we found that LPS treatment could induce homing of macrophages and PMNs in the lungs and accelerate the injury. Interestingly, pre-treatment with LCR was found to attenuate this effect, revealing its protective role against ALI.

NF-κB, a key player in the modulation of inflammatory and immune responses, plays an essential role in regulating the transcription of several inflammatory factors and cytokines, including IL-1β, IL-18, IL-6, and TNF-α (39, 40). Local production of cytokines in lung tissues, in response to infectious or inflammatory stimuli, could also attract immune cells to the inflammatory sites, resulting in pulmonary injury (41, 42). In unstimulated cells, the Rel protein dimers, which are mainly composed of p65 and p50 subunits, are normally sequestered in the cytosol as an inactive complex via binding to inhibitor κB-α (IκB-α) (43). Subsequent degradation of IκB-α, via activation of inhibitor κB kinase, will phosphorylate NF-κB. The resulting free NF-κB is then translocated into the nucleus, where it binds to the κB-binding sites in the promoter regions of the targeting genes and results in the transcription of pro-inflammatory mediators (44, 45). Myeloid differentiation 2 (MD2) is a co-receptor that physically associates with TLR4 on the cell surface and regulates the interaction between LPS and TLR4 (46). TLR4 was suggested to be a crucial sensing receptor for bacterial LPS (47). Activation of TLR4 by LPS results in the activation of the IκB-α/NF-κB pathway, contributing to the over-production of pro-inflammatory cytokines (48). Consistent with the findings of previous studies, we found that the production of pro-inflammatory cytokines, such as IL-1β, IL-18, IL-6, in BALF, serum, and lung tissues was dramatically increased by LPS, confirming the inflammation. However, LCR pre-treatment could attenuate the production of these pro-inflammatory cytokines by regulating the expression of TLR4, MD2, and p-NF-κB, under both in vivo and in vitro conditions, indicating that LCR can block LPS-induced inflammation through NF-κB inactivation.

The mechanisms responsible for epithelial cell apoptosis in ALI are far from being understood. According to a study conducted previously, the alveolar epithelium of patients who die of lung injury contains cells that display evidence of DNA fragmentation (49). Further, alveolar pneumocytes from humans with diffuse alveolar damage exhibit up-regulation of Bax, which is a Bcl-2 analog, that promotes apoptosis (50, 51). In murine models of pulmonary fibrosis and LPS-induced lung injury, apoptosis of alveolar epithelial cells has been reported (52). Bcl-2 is a potent suppressor of apoptosis. It can stabilize the mitochondrial membrane and inhibit the release of cytochrome-c. Subsequently, cytochrome-c can bind to caspase-9, which results in the activation of caspase-3 (53). Caspases are known as cysteine proteases and are synthesized as inactive proenzymes (54). In our study, apoptosis was evident in lung tissue samples of LPS-exposed mice, as evidenced by enhanced caspase-3 and PARP cleavage as well as increased expression of Bax. However, pre-treating with LCR could reduce caspase-3 and PARP cleavage and Bax expression, while also improving Bcl-2 expression. Similar results were also observed in our in vitro experiment using human lung epithelial cells. These data suggest that LCR could improve LPS-induced ALI by suppressing the apoptotic response.

In conclusion, our study indicated that pre-treatment with LCR could alleviate LPS-induced ALI in mice, as evidenced through improved histologic alterations, reduced inflammatory cell infiltration, and anti-inflammatory and anti-apoptotic effects that were dependent on the inhibition of TLR4/NF-κB and caspase-3/PARP pathways, respectively. This resulted in improved survival of mice against LPS induced ALI and thus, LCR might be an effective and promising candidate to protect lungs against this mortal condition.

ALI

Acute lung injury

Lonicerin

lipopolysaccharide

bronchoalveolar lavage fluid

polymerases (PARP) poly

toll-like receptor 4

nuclear factor-kappa B

acute respiratory distress syndrome

tumor necrosis factor-alpha

interleukin-1 beta

Real time-quantitative PCR