Frontiers in Bioscience-Landmark (FBL) is published by IMR Press from Volume 26 Issue 5 (2021). Previous articles were published by another publisher on a subscription basis, and they are hosted by IMR Press on imrpress.com as a courtesy and upon agreement with Frontiers in Bioscience.

1 State Key Laboratory of Stem Cell and Reproductive Biology, Institute of Zoology, Chinese Academy of Sciences, Beijing, 100101, China

2 Beijing Key Laboratory of Animal Genetic Improvement, China Agricultural University, No. 2 Yuanmingyuan West Road, Beijing, 100193, China

3 Changsha Reproductive Medicine Hospital, Hunan, Changsha, 410205, China

4 Reproductive Medicine Center of People’s Hospital of Zhengzhou University, Zhengzhou 450003, China

5 Reproduction Medical Center, Yantai Yuhuangding Hospital of Qingdao University, Yantai 264000, China

6 Key Laboratory of Fertility Preservation and Maintenance of Ministry of Education, Ningxia Medical University, Yinchuan 750004, China

Abstract

Mammalian fertilization that culminates by fusion of the male and female gametes is intricately regulated within the female reproductive tract. To become competent to fertilize an egg, the mammalian spermatozoa that enter the female reproductive tract must undergo a series of physiological changes, including hyperactivation, and capacitation. For reaching full competency, the acrosome, a specialized membrane-bound organelle that covers the anterior part of the sperm head, must undergo an acrosome reaction. For becoming competent to bind an ovum, and to penetrate the zona pellucida and cumulus, many sperm proteins are released in the course of the acrosome reaction. Ultimately, the acrosome binds to the oolemma and fusion of sperm and egg occurs. In this review, we outline current understanding of the roles and effects of some essential sperm proteins and their functions during fertilization in the female reproductive tract.

Keywords

- Fertilization

- Sperm proteins

- Sperm-oocyte fusion

- Acrosome

- Review

The fusion of spermatozoa and oocytes is a complex process, involving capacitation, hyperactivation, the acrosome reaction (AR), binding of the spermatozoon to the zona pellucida, and activating the oocyte reaction (1). Fusion of spermatozoa with the oocyte plasma membrane occurs via the inner acrosomal membrane (IAM) exposed after the AR. In mammals, gamete fusion takes place through a specialized region of the acrosome known as the equatorial segment (ES) which becomes fusogenic only after the AR has been completed (2). Many studies have been performed on the functions of the acrosome and several molecules have been reported. For example, a set of attachment protein receptors has been reported (3), including PH-20 (4), ZP3R (5), SP-10 (6), IZUMO1 (7), and ADAM2 (which belongs to the ADAM family of proteins) (8). In particular, Equatorin, a complex 38–48 kDa protein in mice, is specifically located to the acrosomal membrane in various species, including humans (9–13). Our previous study showed that Equatorin plays an important role in acrosomal formation and fertilization (12). Research on sperm proteins participating in sperm–oocyte fusion has been the subject of many investigations to identify their roles and improve the diagnosis and treatment of human infertility. These studies have shown that sperm proteins can exert unique effects on fertilization in the female reproductive tract, which is the focus of this review.

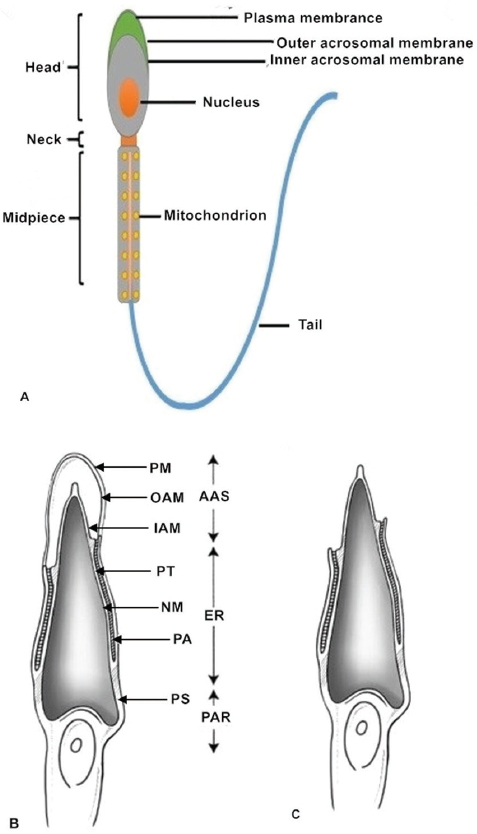

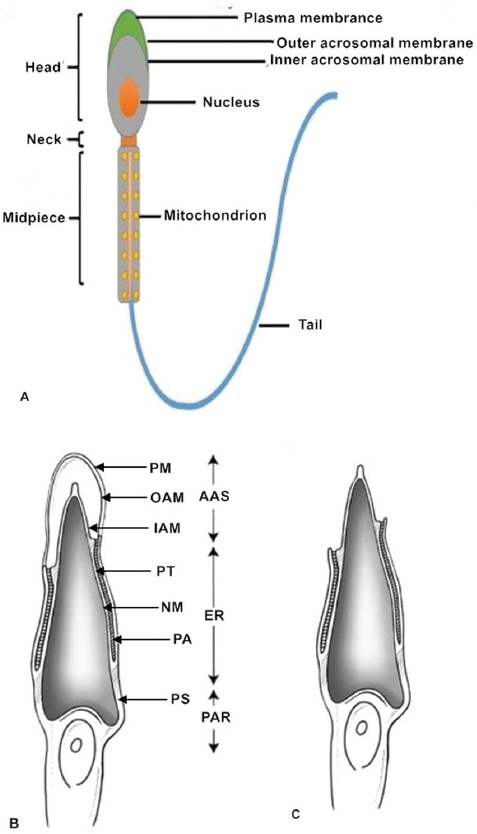

Normal, healthy mammalian spermatozoa range in length from about 40 to 250μm (a human sperm cell is 60–70μm long) consisting of a head, neck and principal piece (midpiece and tail) (14). The sperm head contains a highly condensed nucleus with haploid DNA surrounded by nuclear membranes (15, 16). The acrosome is a membrane-bound vesicle located outside the nucleus on the apical part of the sperm head. The acrosomal membrane is further subdivided into two parts: one is the inner acrosomal membrane that lies external to the sperm nuclear membrane; the other is the outer acrosomal membrane that covers most of the acrosome and lies below the sperm plasma membrane. Some important enzymes involved in sperm penetration of oocytes and their vestments are found in the acrosome (12, 17). The sperm midpiece contains mitochondria that provide power in the form of ATP for sperm tail movement (14). All structures of the sperm flagellum function to provide energy for swimming toward the oocyte and completing fertilization in vivo (Figure 1).

Figure 1

Figure 1Sperm structure. (A) The normal healthy mammalian spermatozoon includes the head, neck, midpiece and tail. The sperm head contains a highly condensed nucleus with its haploid genome surrounded by nuclear membranes. The acrosomal membranes include the inner acrosomal membrane which lies external to the sperm nucleus; the other is the outer acrosomal membrane which lies below the sperm cell plasma membrane. The sperm neck is followed by a short midpiece, containing mitochondria providing the power for sperm tail movement. The schematic diagrams show different parts of the sperm head before (B) and after (C) the acrosome reaction. After the acrosome reaction and zona penetration, the spermatozoa lose the plasma and outer acrosomal membranes of the anterior acrosomal portion, releasing the acrosomal matrix and exposing the inner acrosomal membrane (C). The plasma membrane and the equatorial segment of the posterior acrosome remain intact. AAS, Anterior acrosomal sac; ES, equatorial segment; IAM, inner acrosomal membrane; N, nucleus; NM, nuclear membrane; OAM, outer acrosomal membrane; PA, posterior acrosome; PAR, post acrosomal region; PM, sperm plasma membrane; PS, postacrosomal sheath; PT, perinuclear theca.

The zona pellucida (ZP) is a specialized extracellular matrix that contains three major glycoproteins, designated ZP1, ZP2 and ZP3 (18). Early studies demonstrated that ZP3 is the only glycoprotein that potently enables murine sperm–ZP binding and allows spermatozoa to attach to the ZP. Sperm–ZP binding is a critical step of sperm–oocyte fusion and follows the AR (18–20). Many studies have shown that degradation of the sperm plasma membrane leads to the loss of ZP3 receptors; a glycoprotein receptor to ZP2 is exposed and replaces the function of that for ZP3 (21). Thus, ZP2 serves as a secondary receptor for spermatozoa during the fertilization process and maintains binding of acrosome-reacted spermatozoa to oocytes. However, these glycoproteins appear to be indispensable elements for the function of oocytes. In mice, knockout of the coding genes for ZP2 or ZP3 prevent the development of a normal ZP, resulting in infertility (22, 23). A clinical study also showed that the ZP3 mutation, c.400G>A (p. Ala134Thr), prevents the assembly of the ZP and leads to oocyte degeneration (24). In addition, development of a normal ZP is prevented because of defective ZP1 and leads to the sequestration of ZP3 into the ooplasm (25). The sperm flagellum continues to provide power to help it penetrate through the ZP and effect fertilization. After spermatozoa penetrate the ZP, they will pass into the perivitelline space. Penetration of the human spermatozoon passing through the ZP takes less than 30 seconds under in vitro conditions (26).

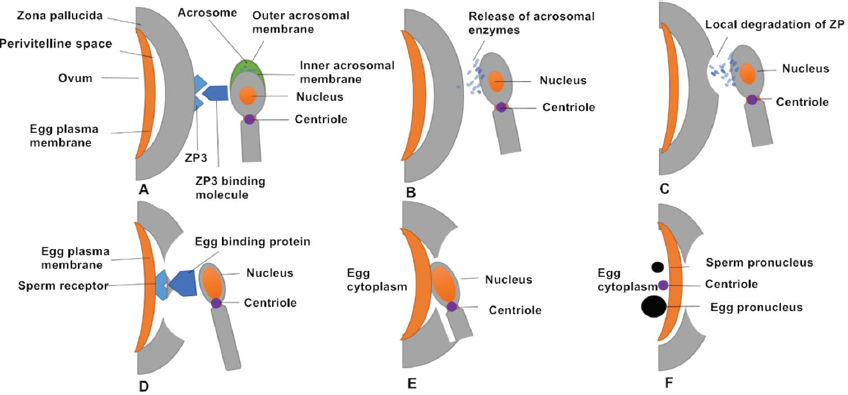

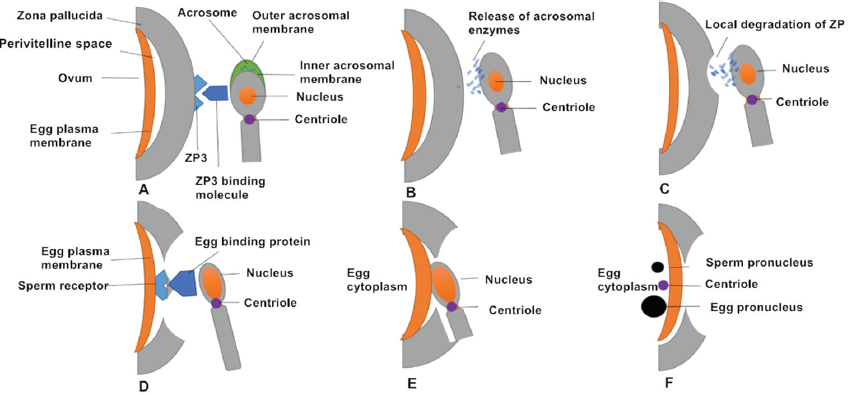

Successive stages of mammalian fertilization occur as follows. First, sperm–oocyte recognition initiates via ZP3 and ZP3 binding molecules on the sperm surface. Proteins on the sperm membrane bind to ZP3 (or ZP2) on the outer surface of the ZP. Second, ZP binding and the AR occurs. Sperm–oocyte binding triggers the AR, in which the sperm plasma membrane forms point fusions with the outer acrosomal membrane, causing exocytosis of the acrosomal contents. It is generally thought that that the AR begins after the spermatozoon binds to the ZP. However, oocytes of transgenic mice (ZP2Mut and ZP3Mut) could also be fertilized, demonstrating that the AR occurred at the time of sperm passage through the ZP or before reaching it (27). Third, acrosomal enzymes are released and the spermatozoon penetrates the ZP. Acrosomal enzymes assist in dissolving a hole in the ZP. Accompanied by sperm tail beating, sperm move through the ZP. During this time, cumulus cells also release factors to promote sperm penetration through the oocyte and to enhance sperm motility (28, 29). Fourth, oocyte binding proteins mediate sperm receptor recognition. Egg-binding proteins such as JUNO on the oocyte surface bind to molecules on the sperm cell membrane. Fifth, oocyte–sperm membrane fusion occurs and the sperm head and centriole enter the oocyte together with the midpiece and principal piece in most species. Finally, the male and female pronuclei migrate toward each other with the aid of microtubules and syngamy eventually occurs (16) (Figure 2).

Figure 2

Figure 2Successive stages of mammalian fertilization. (A) Sperm–oocyte recognition through ZP3 and ZP3 binding molecules. (B) ZP binding triggers the AR, in which the sperm plasma membrane fuses with outer acrosomal membrane and releases acrosomal enzymes. (C) Acrosomal enzymes dissolve a hole in the ZP to help sperm penetrate the oocyte. (D) The oocyte-binding protein (JUNO) on the inner acrosomal membrane binds to a sperm receptor on the oocyte surface. (E) Oocyte–sperm membrane fusion allows the sperm nucleus and centriole to enter the oocyte. (F) The sperm (male) pronucleus and oocyte (female) pronucleus migrate toward each other.

The first AR studies were carried out using conventional microscopy in 1952 (30). Studies found that mammalian fertilization requires a series of changes in the AR process, requiring necessary time-dependent physiological changes in spermatozoa in the female reproductive tract, collectively known as capacitation (31, 32). Recently, the terms ‘acrosomal exocytosis (AE)’ and ‘AR’ have been used interchangeably (33, 34). AE is a terminal morphological alteration of the spermatozoon and is a synchronized and tightly regulated progress during mammalian fertilization, including opening of hundreds of fusion pores between outer acrosomal membrane and sperm plasma membrane during sperm penetration of the ZP (30, 31). Moreover, the physiological site of the AE in the mouse has been determined to be the upper isthmus of the oviduct using genetically modified strains that carry DsRed2 in the mitochondria and enhanced green fluorescent protein (EGFP) in the acrosome (35).

The function of the acrosome depends on its characteristic configuration. The common features include three structures: an inner acrosomal membrane (IAM), which is laminated to the sperm nucleus, an outer acrosomal membrane (OAM), which is close to the plasma membrane over the acrosome and an equatorial segment (ES), which forms the posterior acrosomal margin where the IAM and OAM meet (32) (Figure 1). Acrosomal formation during late meiosis in the testis originates from small, proacrosomal vesicles in the Golgi apparatus of pachytene spermatocytes (36–38). The haploid spermatids inherit these proacrosomal vesicles containing a variety of proteins assemble and fuse; these proacrosomal vesicles eventually form a head structure that then gradually covers the future anterior segment of the sperm nucleus. The final sperm maturation phase occurs during epididymal transit.

As mentioned above, the acrosome is a vital organelle for fertilization, especially for AR and ZP binding. Sperm antigens are released in the course of AR to assist the binding of the spermatozoon to the oocyte. This release relies on a strict time schedule, which is decided by the location of the antigen (39). According to the different receptors involved, we can divide antigens into two main groups: sperm acrosomal antigens involved in binding to the ZP, and other antigens participating in the binding of the sperm and oocyte plasma membrane.

Zona pellucida 3 receptor (ZP3R), initially named SP-56, was first identified as a 56 kDa mouse sperm surface protein with a specific receptor for ZP3; however, there is no report about human ZP3R to date. ZP3R was found to be located on the intact sperm surface and was ascertained to be a binding site for ZP3 in acrosome-intact spermatozoa using photoaffinity cross-linking (40). With progression of the AR, proteases can dissolve ZP3R, and then it is released in areas surrounding the anterior acrosome (41). However, some studies found that ZP3R cannot be identified in live sperm surfaces before capacitation. This suggests that ZP3R is an intra-acrosomal component (42). In addition, as recombinant ZP3R can interact with the ZP of unfertilized oocytes but not with that of 2-cell embryos, it suggests that the changes taking place in the ZP during fertilization might influence the binding of ZP3R (5). Although ZP3R is an acrosomal matrix protein, it might have a vital role in sperm–ZP adhesion during fertilization (41). By targeting deletion of the Zp3r gene, the results showed that males and females homozygous for the affected gene exhibited no differences in litter sizes compared to wild-type and heterozygous animals. This study proves that either ZP3R is not involved in sperm-zona pellucida binding or this process might be functionally redundant, involving multiple proteins for gamete interactions (43).

Sperm protein-10 (SP-10) was first detected in human spermatozoa (44), and is produced via acrosomal vesicle protein 1 (ACRV1), and was later identified to be present in all tested mammalian species, including mice and baboons. SP-10 is specifically expressed in the testes and exclusively restricted to round and elongated spermatids (45). SP-10 can be first detected in the acrosomal vesicle of Golgi phase spermatids, and subsequently appears on the acrosomal vesicle. The involvement of SP-10 in the binding of sperm to the oolemma is supported by research showing that it is located at the ES (46). Furthermore, the coding gene of SP-10 is viewed as an excellent model to research the transcription of male germ-cell-specific genes (47). Using an anti-SP-10 antibody is used to identify the characteristic morphological features of each stage of acrosomal formation; therefore, it has made staging of the spermatogenic cycle relatively easy and clear (6). In some studies, recombinant SP-10 is used as an immunogen that can be made into man contraceptive vaccine in mouse models (48).

Fertilization antigen-1 (FA-1), a glycoprotein found as dimers (51 ± 2 kDa) and monomers (23 kDa), appears at the end of spermatogenesis. FA-1 exists on the surface of human, mouse, and rabbit spermatozoa. Because of the high conservation of its structure, FA-1 antigen might have similar functions across different species. According to research in human fertilization, as FA-1 is released from the acrosome, it can specifically recognize ZP3. On the sperm surface, once FA-1 recognizes the ZP of mouse oocyte as a complementary receptor molecule, it will affect binding of sperm to the ZP, rather than sperm motility. Antibodies to FA-1 antigen could inhabit sperm–ZP binding and shorten sperm capacitation and AR timing by blocking protein phosphorylation at some amino acids, such as tyrosine, serine and threonine residues (49). Female mice vaccinated with recombinant FA-1 antigen showed long-term, reversible contraceptive effects (50, 51).

PH-20, also known as sperm adhesion molecule1 (SPAM1), is a sperm hyaluronidase, identified in the testes of humans, mice, and bulls (4, 52). PH-20 antigen is located in the plasma membrane over the sperm head and on the IAM. During the AR, PH-20 is found in the IAM and in mosaic vesicles originating from the binding of the sperm plasma membrane and the OAM (53). in addition, after the AR, PH-20 is identified in the IAM of the anterior acrosome and plasma membrane of the ES. Some have used Pichia pastoris to produce a recombinant human PH-20 protein cloned from a specific core DNA fragment of the gene encoding human PH-20 (54). PH-20 has been viewed as multifunctional protein: thus, it is not only a hyaluronidase that is a receptor for hyaluronic acid (HA)-induced cell signaling, but also acts as receptor for the ZP during the AR (55). PH-20, as a sperm hyaluronidase, was regarded as an essential enzyme that can help sperm in penetrating the cumulus surrounding the oocyte when fertilizing. However, in mice, there is some evidence suggesting that PH-20 is not important for this process because the double knockout PH-20 mice remain fertile (56). Accordingly, using human kidney 293 cell lines expressing recombinant pig SPAM1, some have shown that PH-20 can break down the oocyte-cumulus complex during in vitro fertilization (57). Additionally, expression of PH-20 in pig seminal plasma showed significant correlation with high farrowing rates after artificial insemination (58).

A sperm surface antigen involved in fusion of the spermatozoon and oocyte was identified as fertilin (also known as PH-30), which can be divided into ADAM1b (fertilin-α) and ADAM2 (fertilin-β). ADAM1b and ADAM2 constitute a heterodimer via noncovalent binding (59). ADAM1b and ADAM2 belong to the ADAM family (short for a disintegrin and metalloproteinase). Fertilins were first identified in the epididymis of mice and are located in the plasma membrane over the sperm head. In addition, ADAM2 gene knockout mice show functional defects of spermatozoa illustrating that ADAM2 is essential during sperm migration to the oocyte in the female reproductive tract in vivo (60). In mice and monkeys, ADAM2 has been identified as a 100 kDa precursor in the testis, it is processed to a mature form (47 kDa in monkeys, 45 kDa in mice) during sperm maturation (61, 62). However, although ADAM2, in human testis is found as 100 kDa precursors and is found in human spermatogenic cells, western blot analysis did not detect ADAM2 in human spermatozoa (8). In the boar epididymis. migration of fertilin occurs during passage of spermatozoa though the distal corpus, and is complete when spermatozoa pass the proximal cauda (63).

IZUMO1 is one of the immunoglobulin superfamily (IgSF) of proteins and was first detected as a sperm antigen against the OBF13 antibody, which can affect sperm–oocyte fusion in the mouse reproductive tract. In intact spermatozoa, IZUM1 is localized the acrosome and is not detectable on the sperm surface. At the middle stage of the AR, IZUMO1 is released to the sperm surroundings to promote fertilization. In IZUMO–/– male mice, although their spermatozoa can undergo the AR and penetrate the ZP, they are infertile because of a failure in sperm–oocyte membrane fusion (64). JUNO is the oocyte receptor of IZUMO1, and both of them are viewed as vital proteins for sperm–oocyte fusion (65). Moreover, human IZUMO1 can interact with hamster JUNO, illustrating that binding of IZUMO1 and JUNO has been conserved across several species (66). Studies have shown that IZUMO1 undergoes specific phosphorylation changes in the sperm tail during epididymal transit (67), and this region might play an essential role in fertilization. However, another study utilized mice whose sites of IZUMO1 phosphorylation were truncated via the CRISPR/Cas9 system and found that the fertility of the mutated mice was unaffected, indicating that phosphorylation of IZUMO1 appears to be unimportant for fertilization (68).

The equatorin gene, also called MN9 or AFAF in the human genome, encodes this acrosomal membrane protein. Equatorin localization is limited to the IAM and OAM from round spermatids to mature sperm stage and is most likely involved in acrosomal biogenesis. Equatorin is preserved at the ES after the AR and reduced the in vitro fertilization rate in vitro (10, 69). Another in vivo study indicated that mMN9 (an anti-equatorin monoclonal antibody) significantly inhibited the mouse fertilization rate. We found no obvious defects in the acrosome in Eqtn–/– male mice sperm (12), indicating that this protein is not essential for acrosomal biogenesis and that the loss of this gene does not affect acrosomal formation. Our observations revealed that the ES can be identified during acrosome biogenesis as a discrete domain in the acrosomal vesicle as early as the Golgi phase of acrosome biogenesis (70). Equatorin is not likely to be involved in fusion in this region because the OAM and plasma membranes do not fuse in the ES during the AR.

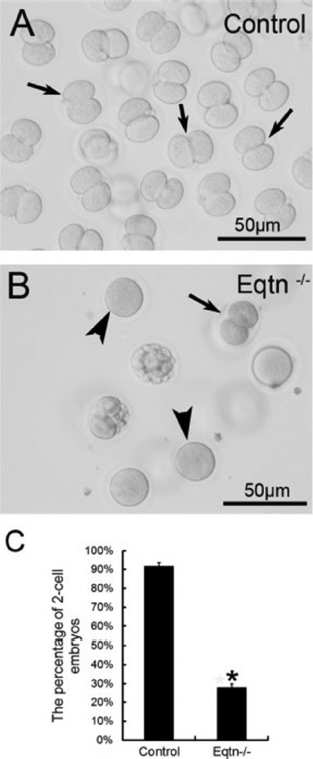

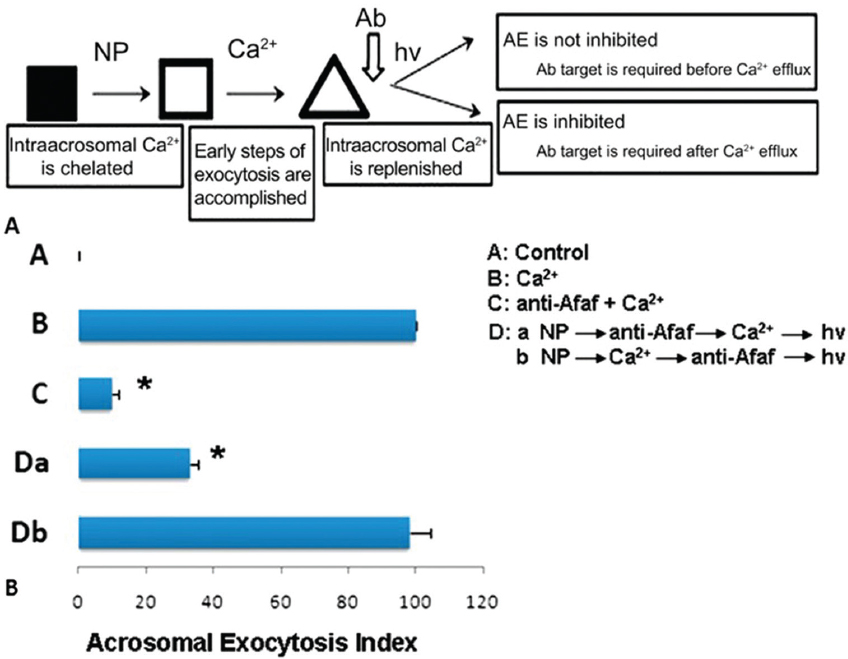

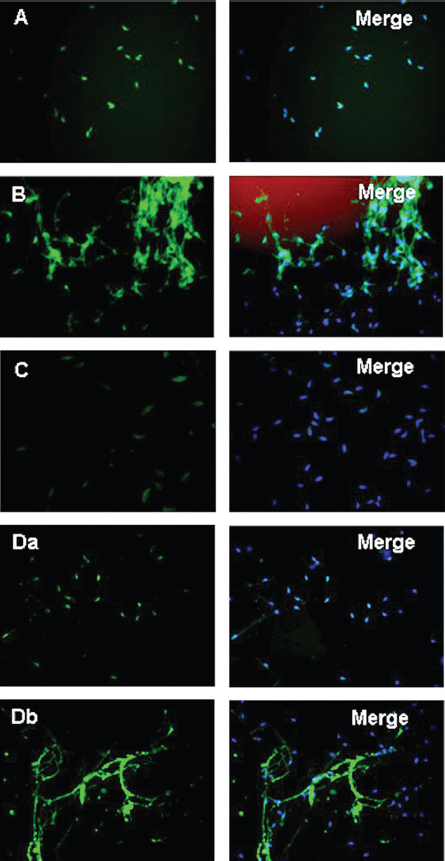

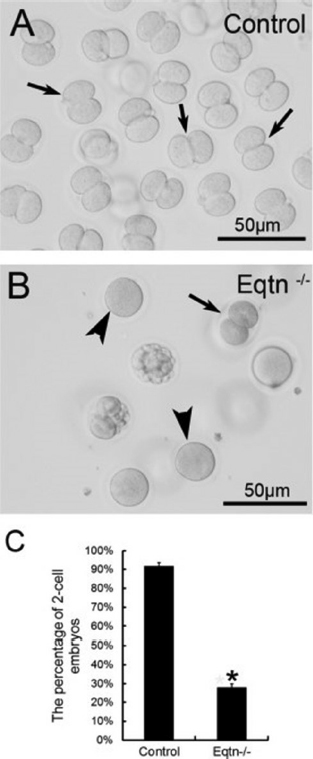

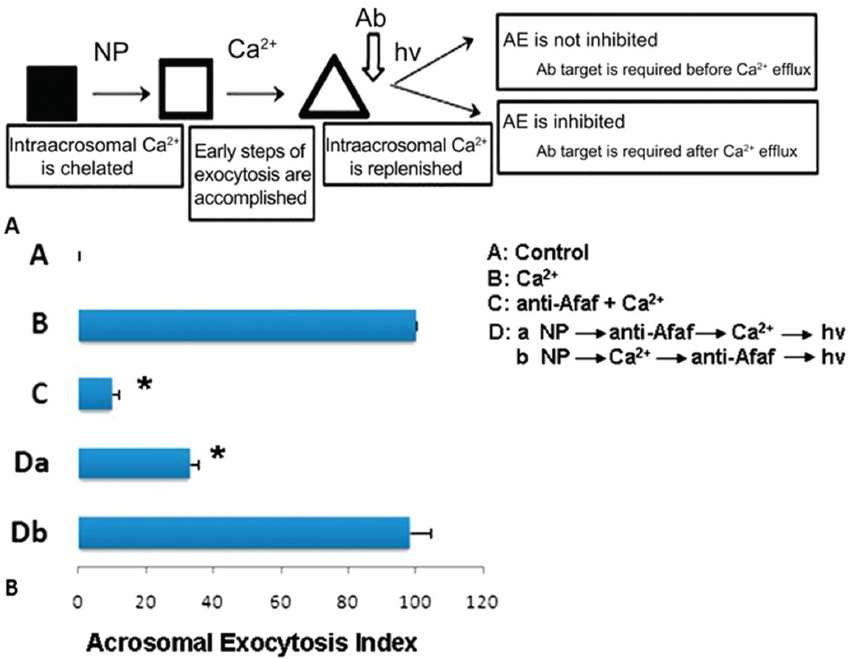

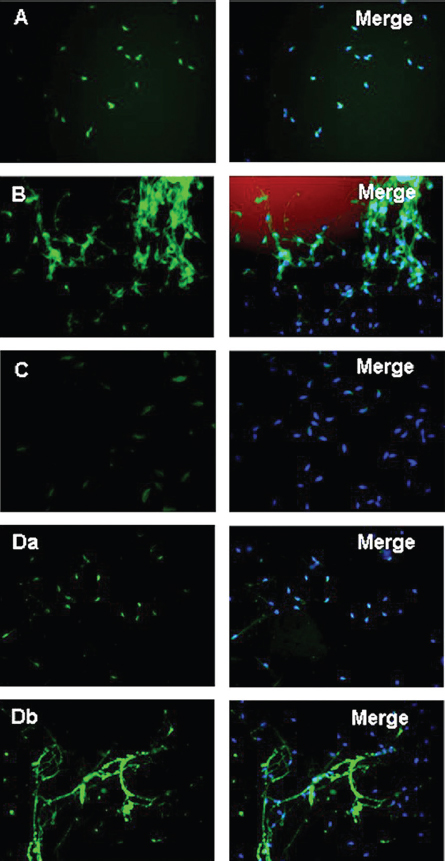

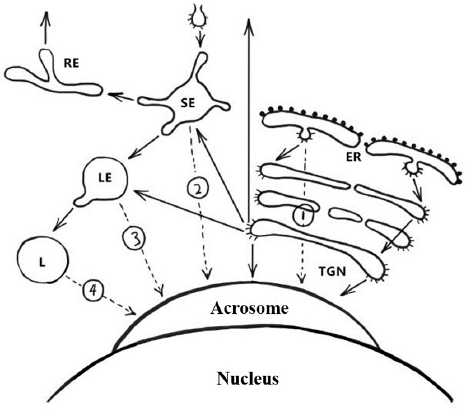

The AR is a universal requisite for sperm–oocyte membrane fusion occurring via the IAM exposed after the AR. Equatorin contained in the posterior acrosome is detectable only after spontaneous or induced ARs following fixation and permeabilization, but not in intact spermatozoa (2). Many studies have shown that equatorin is required for successful sperm–oocytes fusion in vitro and in vivo. We showed that Eqtn–/– male mice were subfertile and their spermatozoa show lower fertilization rates in vivo and in vitro (12) (Figure 3). Equatorin antibodies can significantly inhibit sperm penetration of the oocytes and reduce the in vitro fertilization rate. The mechanism involves calcium-triggered AE by increasing calcium efflux from the acrosome (69) (Figure 4-5). Another study indicated that equatorin interacts with the soluble N-ethyl-maleimide-sensitive factor attachment proteins receptors (SNARE) complex and enables completion of membrane fusion during AE (71). We also demonstrated that the equatorin protein might indirectly interact with SNAP25, a component of the SNARE complex, in a transfected cell line, although its loss did not affect the expression of the SNARE family members (Figure 6).

Figure 3

Figure 3The in vivo fertilization rate of Eqtn-knockout male mice was decreased significantly. Control and Eqtn–/– males were crossed with wild-type females, and embryos were collected from the oviducts at 1.5. days post copulation (dpc). Approximately 90% of the collected oocytes were fertilized and had developed to the 2-cell stage in the control group (A, C: black arrows in A). However, in the Eqtn–/– group, most oocytes remained at the 1-cell stage (B, C: black arrowheads in B), and fewer than 30% of oocytes were fertilized and had developed to the 2-cell stage (B, C: black arrow in B). This difference was significant. *p < 0.0.1 (12).

Figure 4

Figure 4Acrosome formation-associated factor (Afaf) is required for Ca2+-triggered acrosomal exocytosis (AE) by acting upstream of acrosomal Ca2+ efflux. (A) Schematic diagram demonstrating the treatment protocol of spermatozoa. (B) A: In the control group without stimulation, Afaf was present in the acrosome. B: In the presence of 10 mM Ca2+ stimulation, only a few spermatozoa showed Afaf staining. *p < 0.01 (69).

Figure 5

Figure 5In the presence of anti-Afaf antibody and 10 μM Ca2+ (anti-Afaf -Ca2+), the AE index was inhibited dramatically. Da: In the presence of NP followed by anti-Afaf and then Ca2+ and hv (NP-anti-Afaf-Ca2+-hv), AE was inhibited dramatically. Db: In the presence of NP followed by Ca2+ and then anti-Afaf and hv (NP-Ca2+-anti-Afaf-hv), no inhibition of AE was observed. Ab: Antibodies, NP: NP-EGTA-AM (photolabile Ca2+ chelator), hv: flash photolysis of the NP (69).

Figure 6

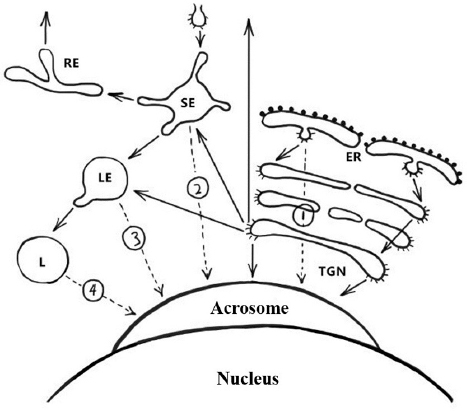

Figure 6Schematic representation of the pathways involved in biogenesis of the acrosome. Solid arrows indicate transport steps that have been well documented and verified, whereas dashed arrows indicate hypothetical transport steps. Numbers denote the extra-Golgi transport steps that possibly contribute to formation of the acrosome. Path 1, the direct transport path from the endoplasmic reticulum (ER) to the acrosome. Path 2, the transport path from the plasma membrane through the SE directly to the acrosome (the hypothetical trafficking path of Afaf). Path 3, transport path from LE to the acrosome. Path 4, the transport route from lysosome to acrosome. Abbreviations: SE, sorting endosome; RE, recycling endosome; LE, late endosome; L, lysosome; TGN, trans-Golgi network (13).

AR is triggered by sperm–ZP binding, which is a necessary prerequisite for successful fertilization. It is an interaction that allows the sperm head’s OAM and sperm plasma membrane to fuse, which enables the exposure of acrosomal contents through the formation of mosaic vesicles and is a critical step in fertilization. During the AR, sperm proteins are released. These can recognize the ZP, and help spermatozoa penetrate the ZP and cumulus. ZP3R acts a vital role in sperm–ZP adhesion, and PH-20 is not merely a receptor for ZP components but helps the spermatozoa pass through the cumulus as a special enzyme. When spermatozoa arrive at the oolemma, other sperm proteins play a role in binding. ADAM2 and IZUMO1 are essential in ensuring that sperm can migrate to the oocyte. However, IZUMO1 is unimportant for fertilization. Equatorin localization is limited to the ES and the IAM and OAM. It is not essential for acrosome biogenesis and knockout of its encoding gene does not affect acrosomal formation but is required for successful sperm–oocyte fusion in vitro and in vivo. These findings suggest that equatorin is essential for sperm–oocyte fusion, so it might be a candidate target for human contraception.

Tie-Cheng Sun and Jia-Hao Wang contributed equally to this work. This work was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (grant no. 31501953 to Shou-Long Deng; 31471352 to Yi-Xun Liu); Clinical Capability Construction Project for Liaoning Provincial Hospitals (grant no. LNCCC-C09-2015, LNCCC-D50-2015) to Yi-Xun Liu and Academician Workstation Support (Shenyang, Changsha and Shandong) to Yi-Xun Liu.