1 Faculty of Chemistry and Engineering, Pontifical Catholic University of Argentina (UCA), S2002QEO Rosario, Santa Fe, Argentina

2 National Scientific and Technical Research Council (CONICET), C1425FQB CABA, Buenos Aires, Argentina

3 Institute for Environmental Sciences, University Kaiserslautern-Landau, 76829 Landau, Germany

4 Laboratory of Ecotoxicology and Environmental Pollution, Institute of Marine and Coastal Research (IIMyC-CONICET, FCEyN), National University of Mar del Plata, 7600 Mar del Plata, Buenos Aires, Argentina

5 Laboratory of Research and Biotechnological Developments (LIDEB), Faculty of Biochemistry and Pharmaceutical Sciences, National University of Rosario (UNR-CONICET), S2002LRL Rosario, Santa Fe, Argentina

§Current address: Laboratory of Environmental and Sanitary Microbiology (MSMLab), Polytechnic University of Catalonia (UPC-BarcelonaTech), 08222 Terrassa, Barcelona, Spain

Abstract

The unsafe disposal of milk processing effluents has a negative impact on the environment due to their high content of nutrients and organic matter. Green alternatives can be applied to effectively manage and valorize these effluents, reducing their environmental footprint.

The ability of the free-living cyanobacterium Oscillatoria sp. to grow in real cheese whey was evaluated as a potential strategy for integrating dairy wastewater treatment with biomass valorization. Autotrophic and mixotrophic cultures were maintained under controlled laboratory conditions and monitored over 28 days for growth, cell viability, biomass, pigment content, and physicochemical parameters, including pH, protein, carbohydrate, and chemical oxygen demand (COD).

Oscillatoria sp. successfully adapted to the initial acidic conditions of the effluent (pH 2.8–2.9), increasing the pH of the treated whey to levels suitable for industrial wastewater disposal (pH 6.0–9.0). A 5-fold increase in dehydrogenase activity was observed after a 28-day culture, with no signs of oxidative damage. Cyanobacterial biomass cultivated under mixotrophic conditions displayed a significant reduction (∼55%) in photosynthetic pigments, including chlorophyll a and total carotenoids, compared to autotrophic cultures. Notably, Oscillatoria sp. biomass increased by 2.3-fold under mixotrophy, compared to the autotrophic control. The higher biomass production was accompanied by a significant reduction in the whey COD from 35,250 mg/L to 8500 mg/L, along with a 65% and 80% decrease in protein and carbohydrate content, respectively.

These findings provide new insights into the metabolic behavior of Oscillatoria sp. during cheese whey bioremediation, highlighting the potential of mixotrophic cyanobacteria for managing dairy wastewater management.

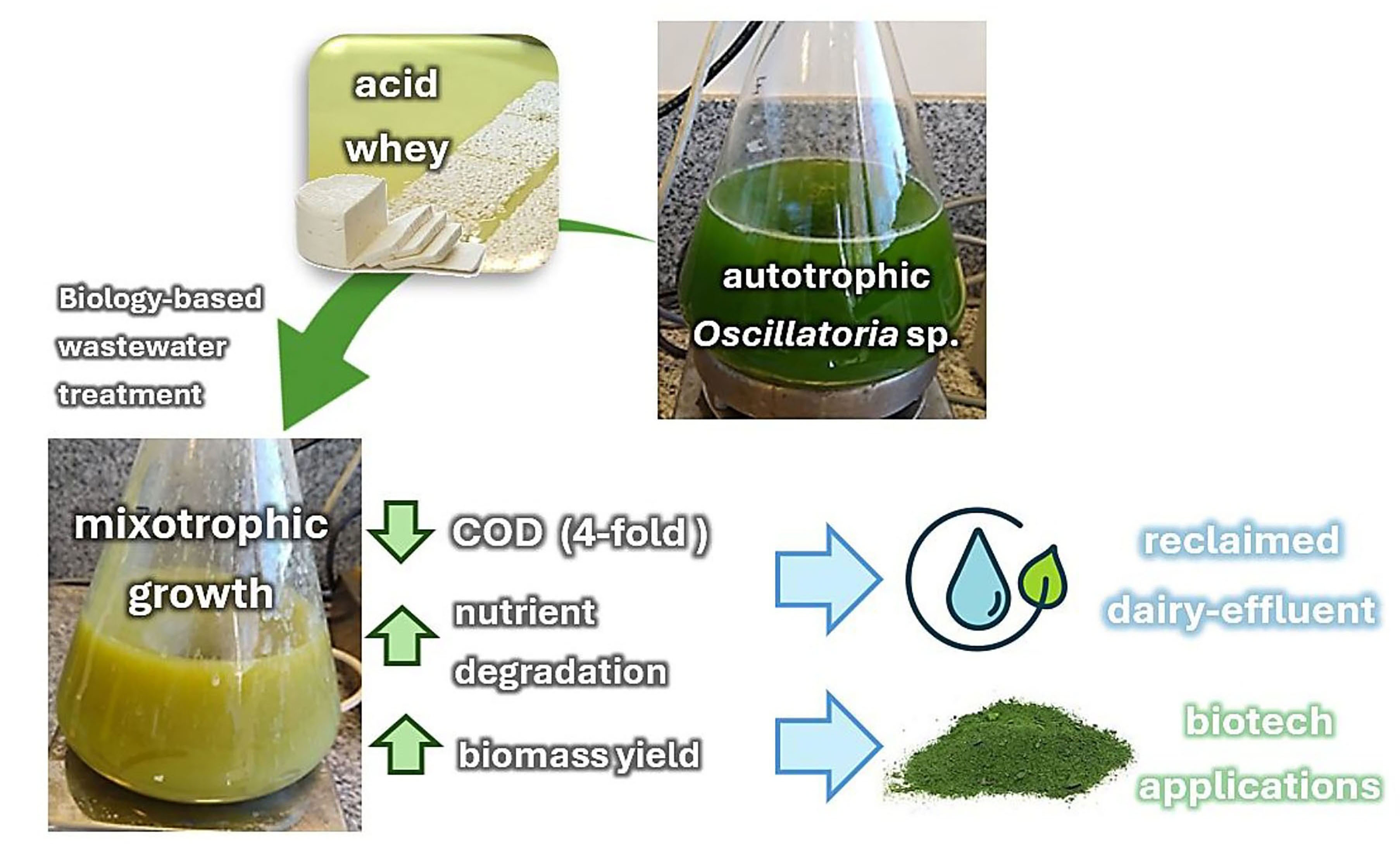

Graphical Abstract

Keywords

- dairy products

- waste water

- environmental sustainability

- cyanobacteria

- heterotrophic processes

- metabolism

- biomass

The dairy industry generates milk processing waste streams that significantly impact the environment [1, 2]. Cheese-making effluents, due to their high nutrient and organic content, contribute to resource depletion and greenhouse gas emissions during wastewater treatment processes [3]. The improper management of cheese whey can lead to microbial contamination, oxygen depletion, acidification, and eutrophication of natural and recreational waters, representing one of the most serious ecological consequences of cheese manufacturing [4, 5]. The final disposal or industrial reuse of whey depends on its quality (i.e., microbial load and physicochemical composition), quantity, available technologies, and the economic costs associated with its treatment.

In recent years, many countries, including the United States, Canada, Australia, New Zealand, and several in the European Union, have implemented strict environmental regulations to mitigate the polluting impact of whey [6]. These new standards, introduced alongside strong circular bioeconomy policies, have encouraged the dairy industry to explore novel approaches and opportunities for reusing the generated effluents [2]. The reuse of cheese whey faces several challenges, including microbial spoilage, high transportation costs, regulatory restrictions, and variability in composition. Effective processing and infrastructure are also required to ensure its sustainable utilization [4, 6, 7]. Therefore, the in situ remediation presents an effective solution to face these challenges. By treating whey directly at the production site, its environmental impact can be mitigated while simultaneously generating bioenergy or microbial biomass. This localized approach enhances sustainability, optimizes resource recovery, and aligns with bioeconomy principles within the dairy industry.

In this context, the production of microalgal and cyanobacterial biomass using agri-food effluents as a nutrient source has gained significant attention [8, 9]. Species such as Chlorella sp., Scenedesmus sp., Nostoc sp., and Plectonema sp. have shown great potential to reduce nutrient, metal, and carbonaceous compound loads in industrial wastewater to safe levels. Large-scale cultivation systems of autotrophic microorganisms can also contribute to carbon dioxide mitigation through photosynthesis [10, 11]. However, these systems usually require nutrient supplementation, which increases costs. Wastewater with a high organic load, such as cheese-making effluents, could serve as an alternative nutrient source, offering both economic and environmental benefits.

Cyanobacteria are of particular interest due to their physiological robustness and ability to convert inorganic carbon into valuable by-products. These microorganisms are increasingly recognized worldwide for their diverse biotechnological applications, including green energy production, sustainable agriculture, wastewater remediation, and use as feedstock in the biopharmaceutical, nutritional, and nutraceutical industries [12, 13, 14, 15, 16]. Among cyanobacteria, Oscillatoria is a dominant genus that thrives in a wide variety of natural environments. Despite its high biomass yield and filamentous structure, which facilitate a more efficient harvesting process, this organism remains largely untapped for the production of bioactive molecules, including food-value pigments [17, 18]. Additionally, limited research has focused on the eco-physiological adaptations that enable Oscillatoria to overcome stressful conditions and adapt to environmental changes. Its bioremediation potential for agri-food effluents, such as cheese whey, remains unexplored despite its known ability to capture excess nutrients. Therefore, a gap remains in understanding the full potential of this blue-green filamentous cyanobacterium.

This work evaluates the ability of Oscillatoria sp. to grow and survive in real cheese whey provided by a local company. The effects on oxidative damage, cell viability (dehydrogenase activity), biomass production, and photosynthetic pigment content (chlorophyll a and total carotenoids) during Oscillatoria sp. mixotrophism were compared with an autotrophic culture. The reduction in the pollutant load of the effluent through co-culturing with Oscillatoria sp. was also assessed by measuring chemical oxygen demand (COD) levels, carbohydrate, and protein content. To the best of our knowledge, this report is one of the first to describe the metabolic and physiological adaptations of this mixotrophic cyanobacterium during cheese whey remediation, as a first step toward its use in dairy effluent management.

The cheese whey sample used in the present study was kindly provided by a local

company (Milkaut S.A., Rafaela, Argentina). This side-stream liquid cannot be

re-introduced into the production chain during dairy manufacturing, and thus must

be properly disposed of, imposing additional costs on the company (data provided

by the supplier). A preliminary characterization of the acidic whey delivered by

the company is presented in Table 1. Biological oxygen demand (BOD5, mg/L)

and chemical oxygen demand (COD, mg/L) were determined according to American

Public Health Association Standard Methods for the Examination of Water and

Wastewater (APHA) methods SM5210-D and SM5220-D, respectively [19]. Electrical

conductivity (EC, mS/cm) and pH were measured using an AD1030 digital pH-meter

(Adwa, Nușfalău, Romania). Density (g/mL) was determined by weight and volume

measurements using a Mettler-Toledo balance (Model ML 201/01; accuracy,

| Parameter | Values |

| pH | 2.85 |

| Density (g/mL) | 1.0276 |

| Conductivity (mS/cm) | 6.55 |

| COD (mg/L) | 75,500 |

| BOD5 (mg/L) | 38,800 |

| Protein content (g/L) | 4.5 |

| Soluble carbohydrates (g/L) | 32 |

| Total fats (g/L) | 1.50 |

| Total solids (g/L) | 46.5 |

| Total heterotrophs (cfu/mL) | 4.0 |

Data are reported as the mean value

Oscillatoria sp. was kindly provided by INTA-Rosario (National

Institute of Agricultural Technology, Santa Fe, Argentina). The cyanobacterial

stock culture was grown and maintained in sterile modified Zarrouk medium (16.8

g/L NaHCO3, 0.5 g/L K2HPO4, 2.5 g/L NaNO3, 1.0 g/L

K2SO4, 1.0 g/L NaCl, 0.2 g/L MgSO4, 0.04 g/L CaCl2 and 1.0 mL

solution A5 prepared with 2.86 g/L H3BO3, 1.81 g/L MnCl2,

0.222 g/L CuSO4

| Parameter | Values |

| pH | 10.0 |

| Conductivity (mS/cm) | 16.5 |

| Protein content (% dry weight) | 38.5 |

| Soluble carbohydrates (% dry weight) | 21.3 |

| Total carotenoids (mg/L) | 10.9 |

| Chlorophyll a (mg/L) | 5.1 |

Data are reported as the mean value

Before the experiments, the biomass was harvested by centrifugation (3000

To compare the growth of Oscillatoria sp. under autotrophic and mixotrophic conditions, 500 mL of cyanobacterial culture (containing both mother microalgae and medium) was directly mixed with either 500 mL Zarrouk medium (Z) or 500 mL raw industrial acid whey (W). Prior to this, any intrinsic microflora in the whey sample was inactivated by UV light irradiation (40 W/cm2, 45 min) [23] to prevent possible interference in subsequent assays. UV sterilization was selected over membrane filtration primarily due to the high viscosity and particulate content of the raw industrial acid whey, which clogged membrane filters and compromised flow rates, making filtration impractical at the volumes used in this study. Additionally, membrane filtration can unintentionally remove macromolecules and micronutrients, potentially altering the nutritional composition of the whey and affecting its ability to support cyanobacterial growth. In contrast, UV sterilization was chosen as a non-invasive, time-efficient, and cost-effective method capable of significantly reducing microbial load in the crude sample, with minimal impact on the overall physicochemical and nutritional profile of the whey.

The effectiveness of the UV treatment was confirmed by plating 1.0 mL of the

treated sample on nutritive agar media (PCA), ensuring the complete absence of

bacterial colony growth. The corresponding control was routinely included in all

assays to ensure the reliability of the conclusions. Both cultures (Z and W) were

maintained under controlled laboratory conditions (23

The pH values of both Z and W cultures were measured using a digital pH-meter

AD1030 (Adwa, Nușfalău, Romania). Chlorophyll a, total carotenoids, soluble

carbohydrates and protein content were quantified by UV-Vis spectrophotometry

following the procedure described by Carralero Bon et al. [22]. Data

were reported as the mean value

To determine the viability of the cyanobacterial cultures, a colorimetric assay

based on the enzymatic reduction of 2,3,5-triphenyltetrazolium chloride (TTC) to

1,3,5-triphenyl formazan (TF, red color) was used [24]. An increase in the number

of metabolically active cells correlates with higher overall activity of

microalgal dehydrogenases responsible for converting TTC into the red-colored TF,

which can be spectrophotometrically measured at 485 nm [22, 25, 26]. Briefly, 2.0

mL aliquots of cyanobacterial culture along with 0.10 mg/mL of TTC

(Sigma-Aldrich, Catalog No. 108380, St. Louis, MO, USA; CAS No. 298-96-4) in test

tubes and incubated in the dark at room temperature for 1 h. After centrifugation

at 7000

TF (µmol/mL) = 0.0603

Lipid peroxidation was evaluated by quantifying the amount of thiobarbituric

acid reactive substances (TBARS) following the method described by Carralero Bon

et al. [22]. Results were expressed as nmol of malondialdehyde (MDA) per

liter (nmol/L) using an extinction coefficient of 155 mM/cm for calculation and

reported as the mean

The cyanobacterial biomass was determined before and after 28 days of growth

under autotrophic or mixotrophic conditions. For this, 10.00 mL samples from

cultures Z and W were added to pre-weighed crystallizing dishes (previously dried

at 105 °C for 24 h). The dishes were then oven-dried at 80 °C

to constant weight, and the loss in weight was calculated as grams of dry weight

per liter (g/L). To correct the data and avoid overestimation of the

cyanobacterial biomass, the same method was applied to determine the dissolved

and particulate solids initially present in the diluted whey, as well as the

amount of dissolved salts in the Zarrouk medium. These values were adjusted to

reflect the reduction in carbohydrates and proteins after 28 days of

cyanobacterial treatment. Data were expressed as mean values

All statistical analyses were performed using SigmaStat 3.5 (Systat Software

Inc., San Jose, CA, USA). The Student’s t-test (for

comparison between two groups) or Tukey’s Honest Significant Difference (HSD)

post-hoc test (for comparison between multiple groups after ANOVA) were

applied, with a confidence interval of 95% (p

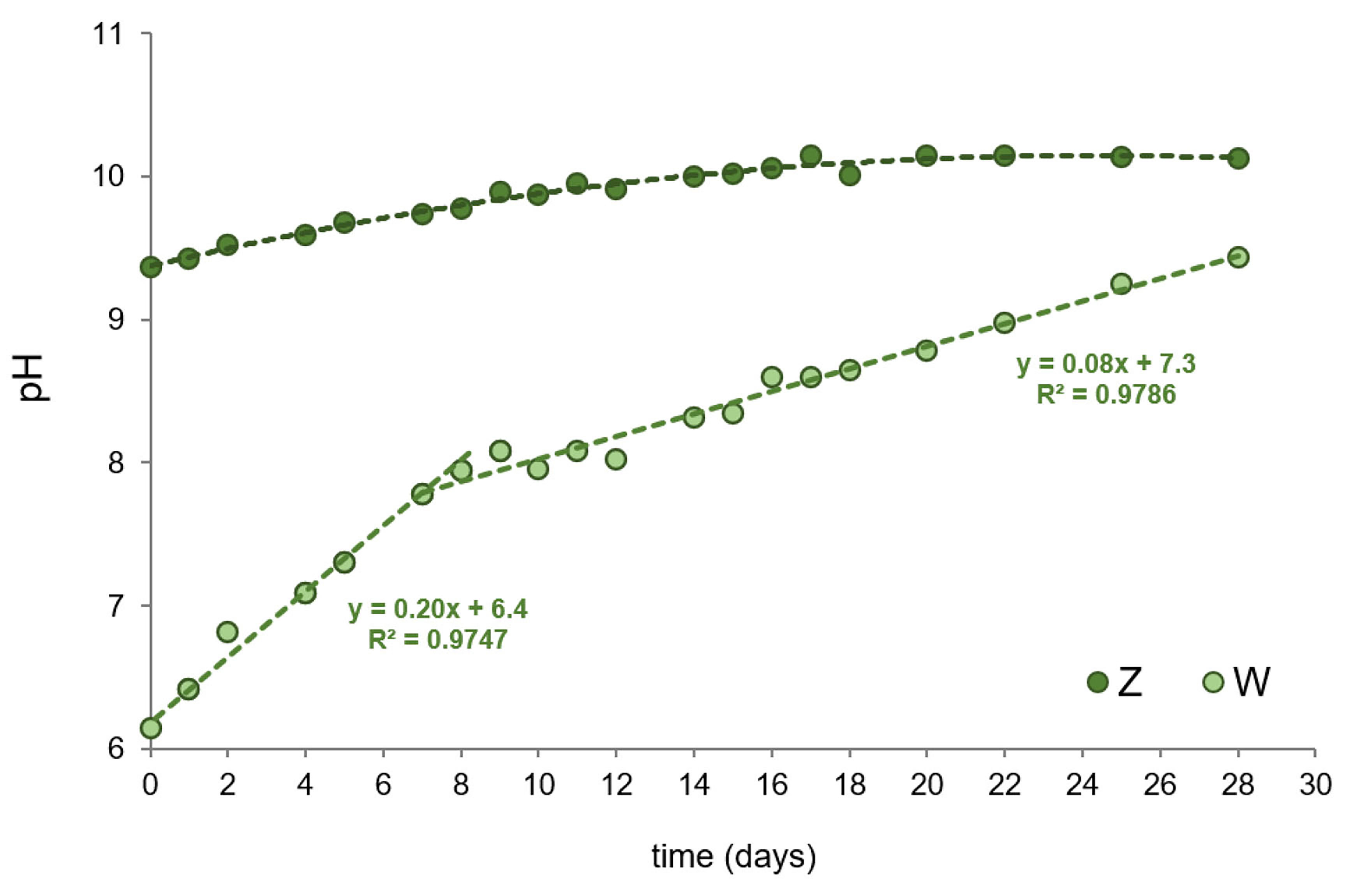

Fig. 1 shows the pH evolution in the autotrophic and mixotrophic cultures (Z and W, respectively) of Oscillatoria sp. over 28 days. The Z culture remained alkaline throughout the entire period, with pH values ranging from 9.4 to 10.1, as expected for an alkaliphilic cyanobacterium. Culture alkalinization is employed by cyanobacteria to reduce nutrient competition, as high pH inhibits the growth of non-alkaliphilic microorganisms [27, 28]. This strategy underscores the ecological advantage that Oscillatoria sp. gains by modifying its environment, alleviating pressure on resources. In contrast, acidification of the medium can serve as an early indicator of microbial contamination, suggesting the presence of competing or harmful microorganisms that could affect culture stability and biomass productivity. Thus, monitoring pH during cyanobacterial growth is an effective tool for evaluating culture health and optimizing growth conditions in both industrial and research settings [27].

Fig. 1.

Fig. 1.

Evolution of pH in Oscillatoria sp. cultures grown under autotrophic (Z) or mixotrophic (W) conditions.

On the other hand, the pH of the mixotrophic W culture initially exhibited lower values (pH 6.0) compared to Z. This can be attributed to the intrinsic acidity of the whey (pH 2.8–2.9; see Table 1), primarily due to the presence of organic acids (e.g., lactic acid) produced by lactic acid bacteria during the cheese-making process. Over the following days, the pH gradually increased, becoming alkaline. Notably, two distinct phases were observed. The first (from day 1 to day 10) showed a rapid pH rise, reaching a value around 8.0, which is still suitable for safe industrial effluent disposal [29]. This behavior could be attributed to the consumption of carbohydrates and organic acids (major components of cheese whey), and to a lesser extent, the degradation of whey proteins (further explained in Section 3.2), which releases ammonia (NH3) into the culture. The second stage (days 10 to 28) showed a more gradual pH increase, reaching a maximum between 9.0 and 9.5 (Fig. 1). The slower increase could reflect the cyanobacterium’s prolonged adaptation to the presence of whey, where the depletion of nutrients slows the rate of degradation, leading to a more gradual pH rise. These results show that Oscillatoria sp. successfully adapted to mixotrophic conditions with a 1:1 ratio of crude whey as the primary substrate. This is particularly relevant, as the acidity of cheese-processing effluents often limits the use of biological methods for whey bioremediation, typically requiring prior chemical neutralization [4, 5]. Minimizing additional chemical or water-based treatments (e.g., dilution) is crucial for reducing costs and the volume of effluent to be treated [30]. Further, the observed pH trends demonstrate that Oscillatoria can not only grow in the presence of acid whey but also generate an alkaline environment, which may help ensure that the resulting biomass remains free of pathogens.

Although the pH evolution of the mixotrophic culture towards alkaline values can be considered a good indicator of healthy cyanobacterial growth [27, 28], analyzing cellular metabolic activity offers a more precise assessment of Oscillatoria sp. viability [31].

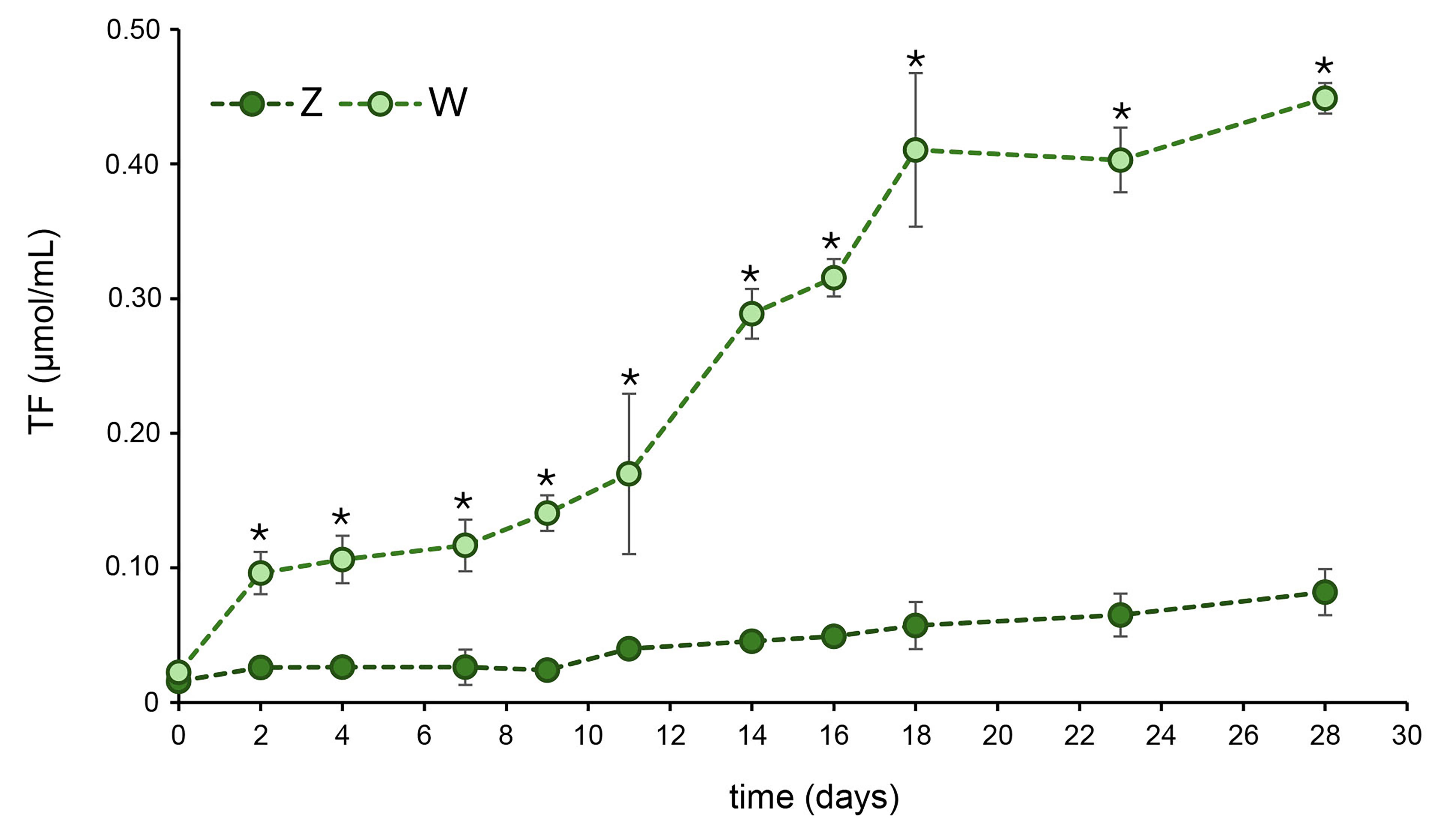

In culture W, a parallel trend between the pH evolution (Fig. 1) and cell dehydrogenase activity (Fig. 2) was observed. The accumulation of TF in the biomass growing under mixotrophic conditions was lower during the first 10–12 days but began to increase from day 14 onward, continuing until the end of the experimental period (day 28). These results are consistent with the two stages of pH evolution observed for this culture in Fig. 1. During the initial days of growth, the suboptimal conditions caused by the high acidity of the cheese whey likely affected the enzymatic reduction of TTC to TF by the cyanobacterial cells, as this conversion is a metabolism-driven process [24].

Fig. 2.

Fig. 2.

Dehydrogenase activity in Oscillatoria sp.

cultures grown under autotrophic (Z) or mixotrophic (W) conditions. Asterisks

(*) indicate statistically significant differences (p

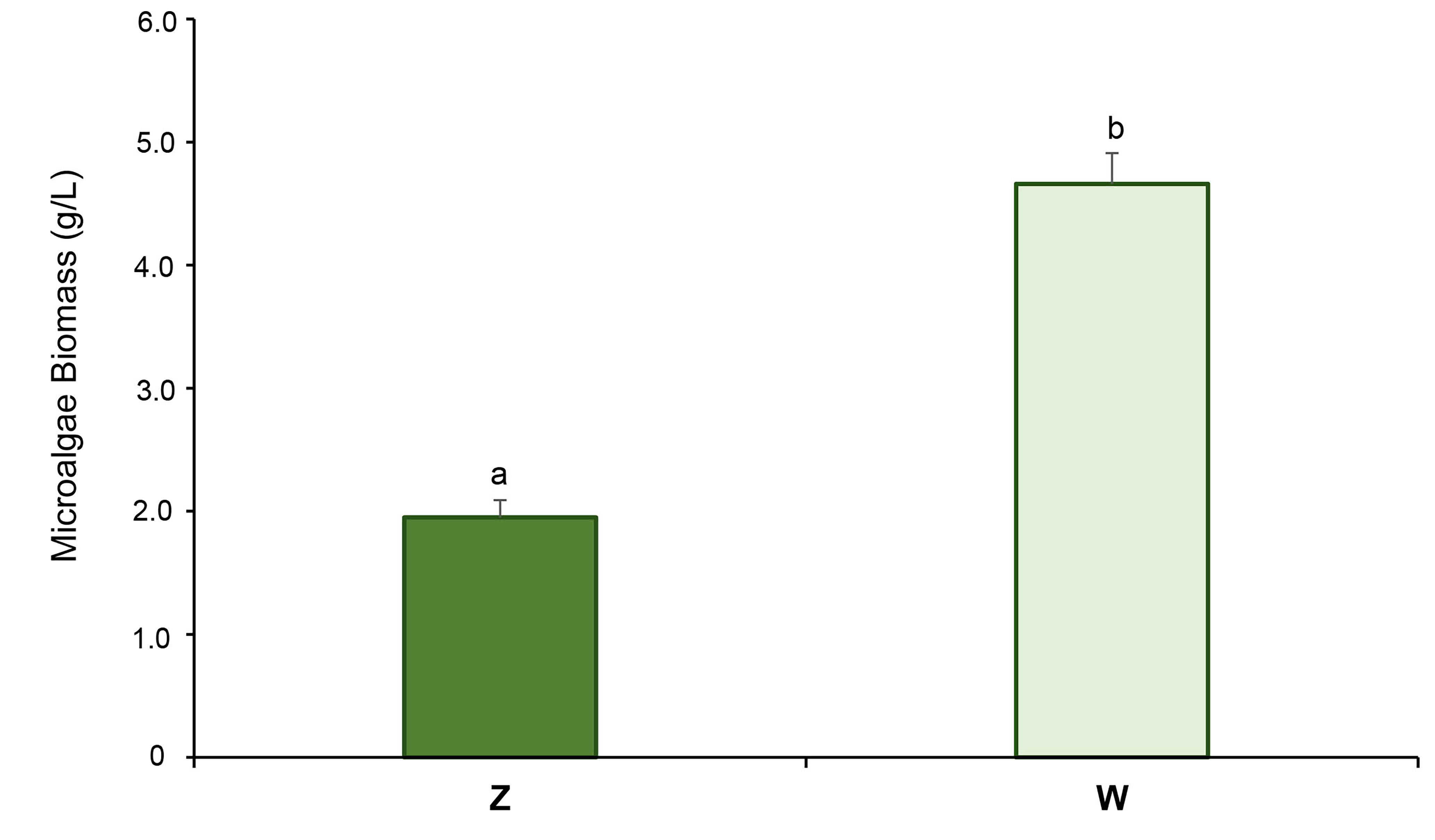

The quantity of TF formed is also proportional to cell density [26].

Accordingly, Fig. 3 shows that under autotrophic conditions (Z), the amount of

cyanobacterial biomass obtained after 28 days of culture was 2.3 times lower (2.0

Fig. 3.

Fig. 3.

Total cyanobacterial biomass production (g/L) after 28

days of growth under autotrophic (Z) and mixotrophic (W) conditions. Different

letters indicate statistically significant differences (t-test,

p

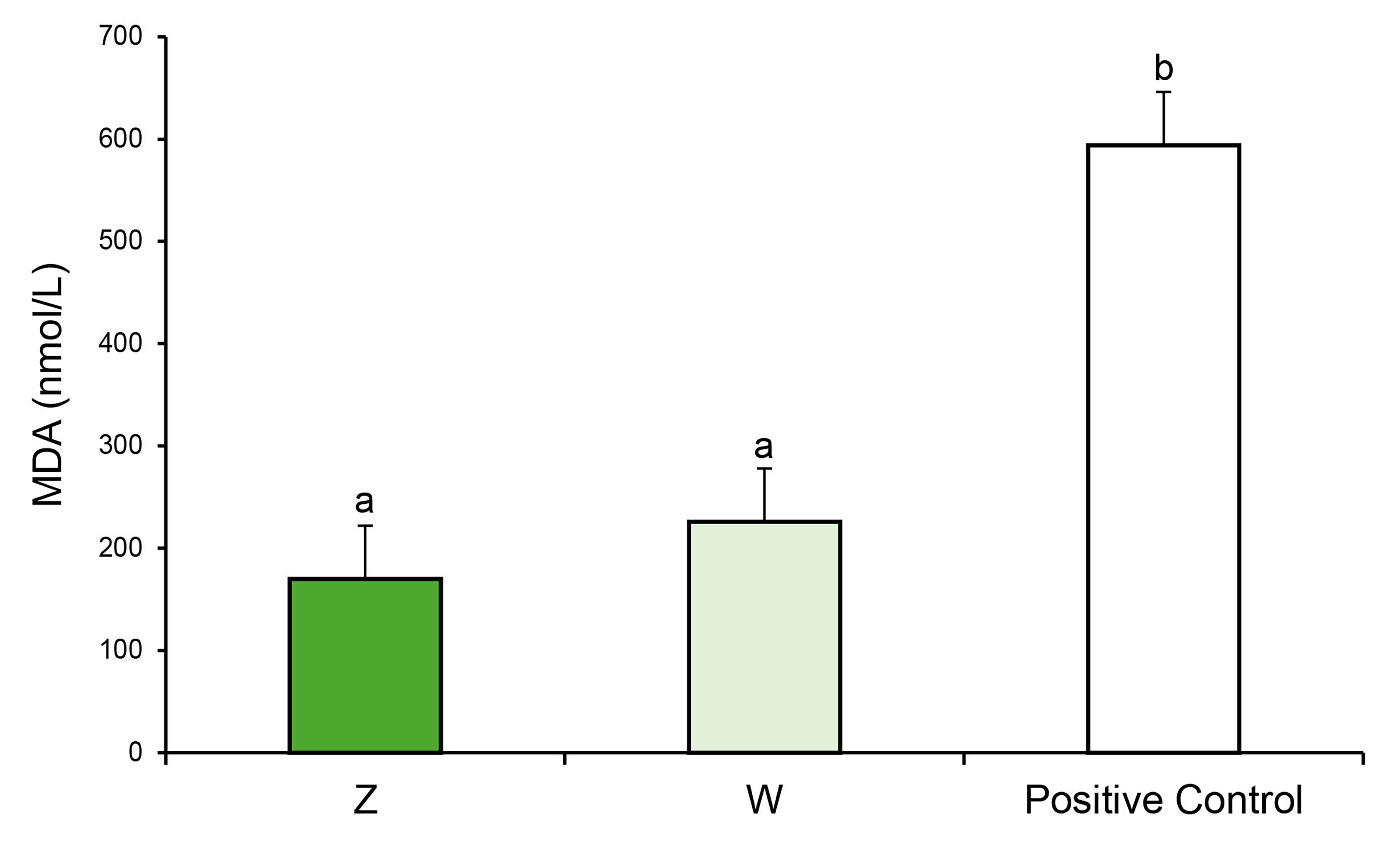

Fig. 4.

Fig. 4.

Quantification of thiobarbituric acid reactive species (TBARs)

in Oscillatoria sp. after 28 days of growth under autotrophic (Z) or

mixotrophic (W) conditions. The positive control refers to TBARs generated in

cyanobacterial cells treated with 1 mM H2O2 for 24 h. Different letters

indicate statistically significant differences (p

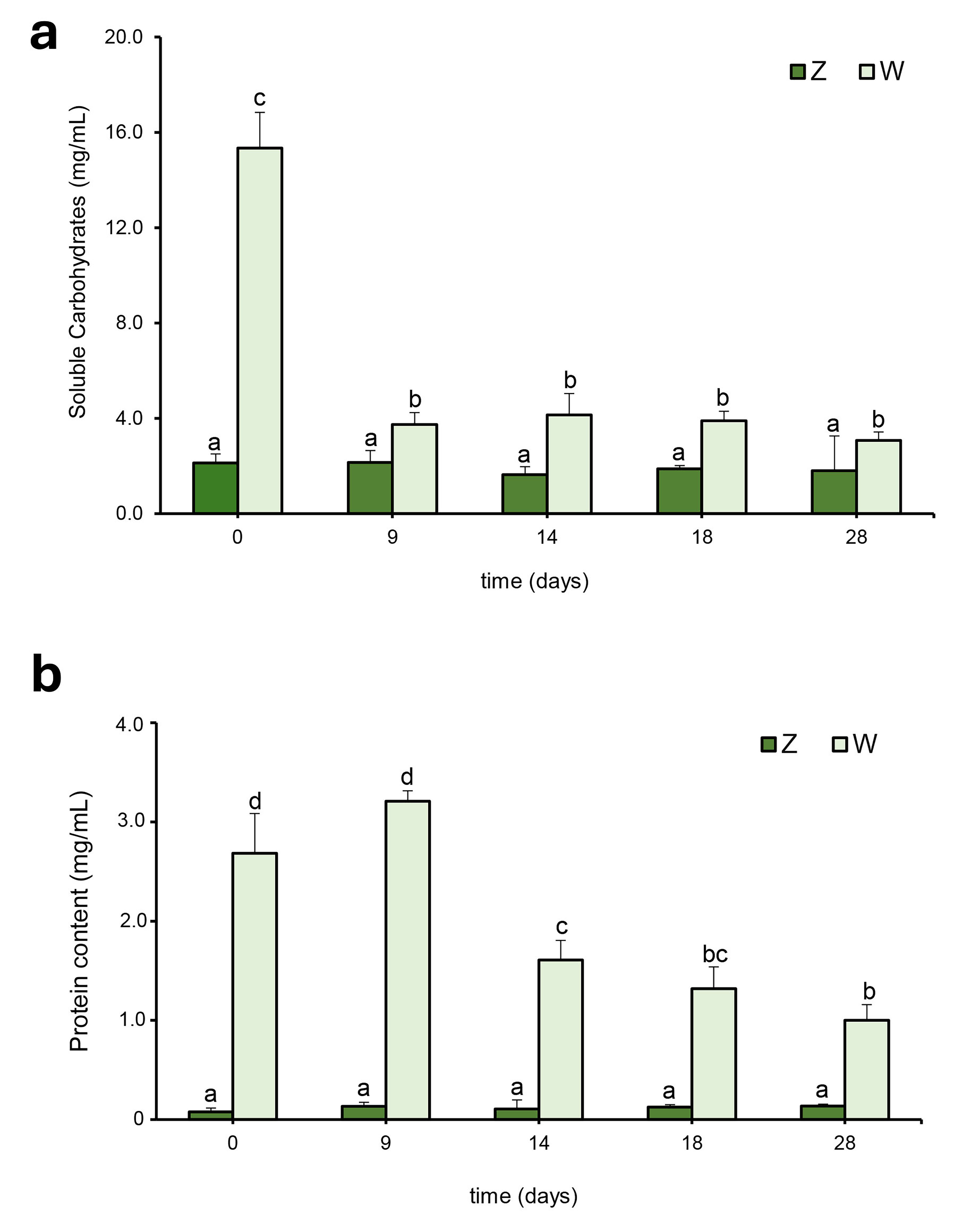

The higher dehydrogenase activity observed in Oscillatoria sp.

grown in the presence of whey, as shown in Fig. 2, provides compelling evidence

of the cyanobacterium’s heterotrophic metabolism. Dehydrogenases are involved in

the aerobic catabolism of carbohydrates, primarily in glycolysis, as well as in

the oxidative pentose phosphate pathway and the tricarboxylic acid (TCA) cycle.

These enzymes also play a role in lipid and protein metabolism [33, 34, 35, 36].

Consequently, the results in Fig. 2 align with the concomitant decrease in

carbohydrate and protein content in the industrial whey when mixed with

Oscillatoria sp. (Fig. 5). The concentration of soluble

carbohydrates in the mixotrophic culture (W) significantly decreased (p

Fig. 5.

Fig. 5.

Changes in the biochemical composition of the culture

medium during cyanobacterial growth. (a) Soluble carbohydrate and (b) protein

contents in Oscillatoria sp. cultures grown under autotrophic

(Z) or mixotrophic (W) conditions (the latter using industrial whey as the

nutrient source). Different letters indicate statistically significant

differences (p

Lipids constitute another major metabolic product of cyanobacteria. Although lipid content was not assessed here due to resources and technical limitations, it is well-established that lipid accumulation often increases under certain stress conditions, such as nutrient limitation or changes in environmental factors [37]. Given that acidic whey presents a complex and potentially stressful growth substrate, it is plausible that Oscillatoria sp. might also modulate its lipid metabolism in response to these conditions. Future investigations incorporating quantitative and qualitative lipid analyses (e.g., solvent extraction followed by chromatographic profiling) would provide valuable insights into the full metabolic adjustments of Oscillatoria during growth on acidic whey.

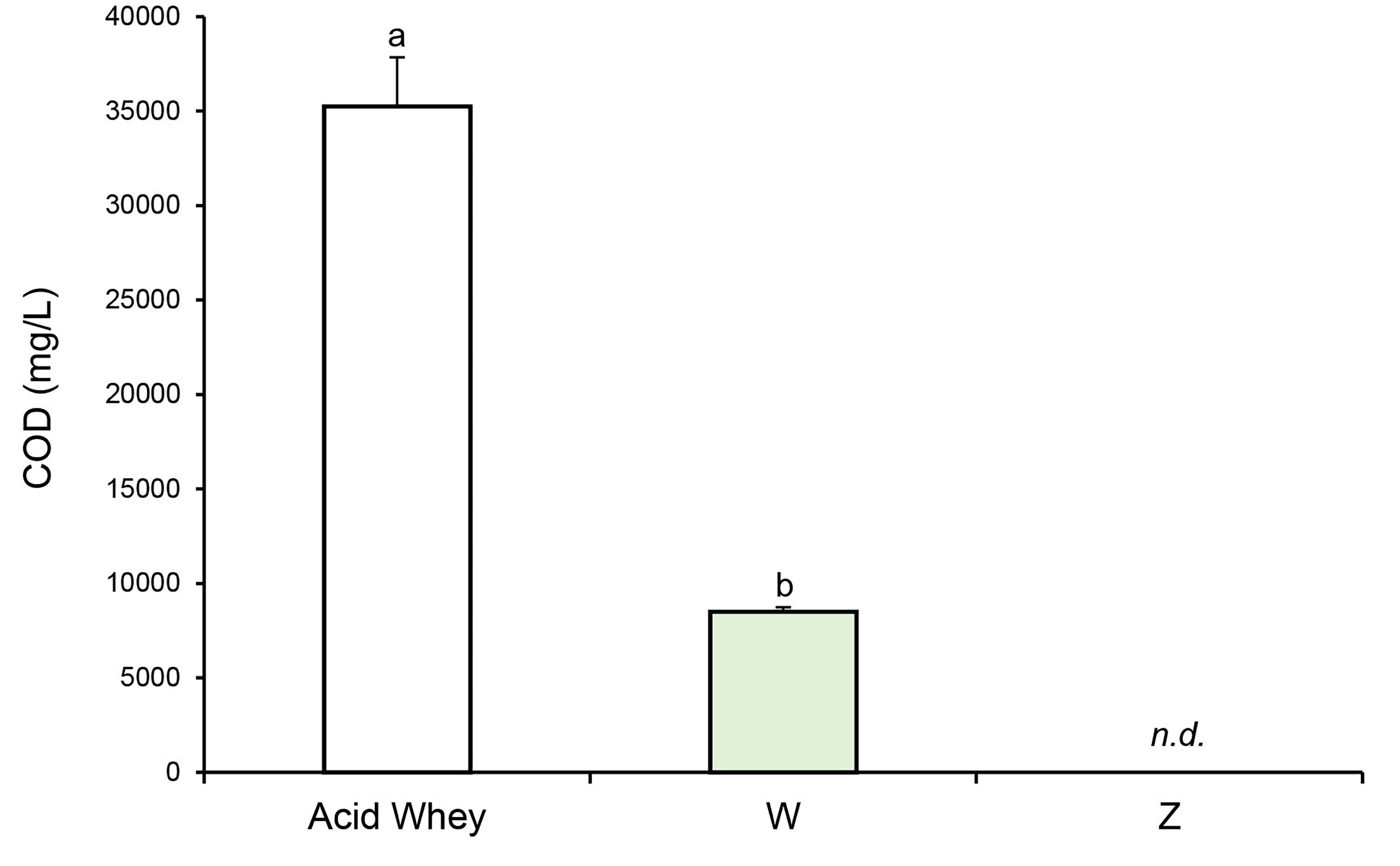

In parallel, the decrease in the content of soluble carbohydrates and proteins

in the mixotrophic culture (W) was strongly correlated with a significant

reduction (about 75%) in the chemical oxygen demand (COD) after 28 days of

culture, compared with the untreated whey (1:1) (Fig. 6). No COD values were

detected in Oscillatoria sp. grown under autotrophic conditions (Z),

which is consistent with the negligible levels of soluble carbohydrates and

proteins quantified (Figs. 5,6). Therefore, the difference in COD between the

mixotrophic culture (W) and the untreated whey sample (i.e., “Acid Whey” in

Fig. 6) is attributed to the consumption of organic matter (e.g., carbohydrates,

organic acids, and proteins) by the cyanobacterium. The COD values in the W

culture remain above the permissible limit for wastewater discharge (

Fig. 6.

Fig. 6.

COD values for the industrial acid whey used in this

study (diluted 1:1) and the supernatants of the mixotrophic (W) and autotrophic

(Z) cultures of Oscillatoria sp. after 28 days. Different

letters indicate statistically significant differences (p

These results highlight the viability of Oscillatoria as an effective primary remediation agent in handling high organic loads. In practical industrial applications, such a biological step would typically be integrated into a multi-stage treatment system, complemented by secondary polishing processes to meet regulatory discharge thresholds. This work therefore serves as a proof-of-concept for the use of cyanobacterial-based treatment in the initial phase of whey effluent management. Furthermore, the mixotrophic behavior demonstrated by Oscillatoria underscores its ability to efficiently utilize organic-rich waste streams such as cheese whey as a growth substrate. This capability not only enhances COD removal but also reduces the need for external nutrient inputs in biomass cultivation. As such, the process holds potential for lowering operational costs in dairy wastewater treatment. These features align well with the principles of a circular bioeconomy, wherein industrial waste is repurposed into valuable biological products, promoting both economic and environmental sustainability [38].

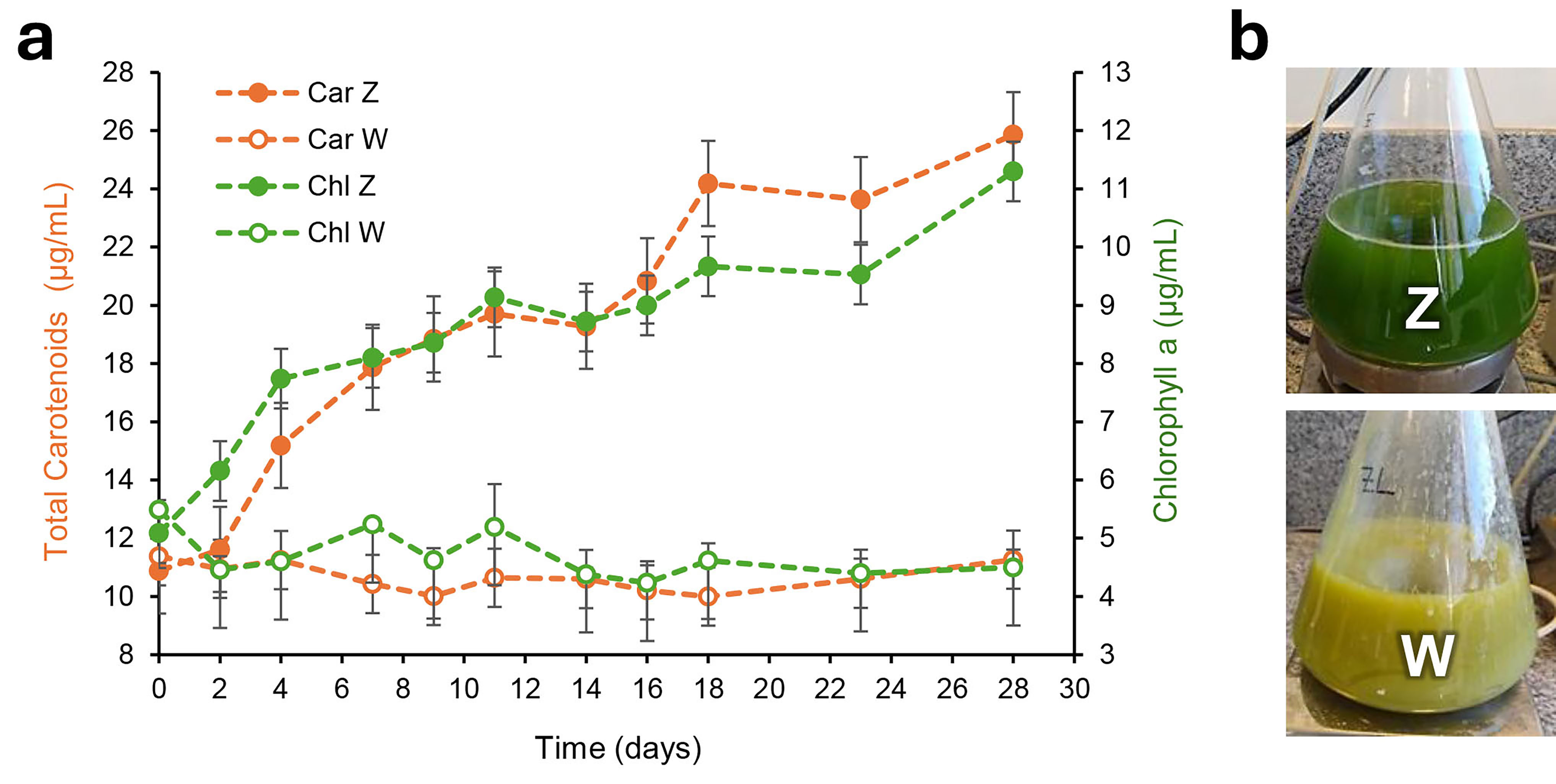

The evolution in the concentration of chlorophyll a and total carotenoids during Oscillatoria sp. autotrophic or mixotrophic growth is shown in Fig. 7a. In the absence of exogenous carbon sources (i.e., culture Z), cyanobacteria depend entirely on their photosynthetic machinery. Under this condition, the cells initiate the biosynthesis of photopigments to maximize light absorption and CO2 fixation [39]. Chlorophylls and carotenoids are the most important molecules involved in photosynthesis, with chlorophylls actively participating in capturing and transforming sunlight into chemical energy, and carotenoids playing a key role in neutralizing reactive oxygen species. Carotenoids also play essential roles as accessory light-harvesting molecules, acting as secondary pigments as well as pro-vitamin factors [40].

Fig. 7.

Fig. 7.

Evolution of photosynthetic pigments during cyanobacterial growth. (a) Changes in chlorophyll a (Chl) and total carotenoid (Car) content in Oscillatoria sp. grown under autotrophic (Z) and mixotrophic (W) conditions over 28 days. (b) Representative photographs of cyanobacterial cultures after 28 days of growth illustrating differences in photopigment content between the two conditions, as described in the text.

The results from Fig. 7a also explain the lower dehydrogenase activity detected in culture Z (Fig. 2), as cyanobacteria lacking an external carbon source grow exclusively through photosynthesis. The reduction of tetrazolium compounds, such as TTC, is not inherently linked to cell ATP production [24]. Therefore, the reduced dehydrogenase activity in autotrophic Oscillatoria sp. is not necessarily associated with ATP depletion in the photosynthetically growing cells.

On the other hand, a significant reduction in chlorophyll a and total carotenoid content was detected in the cells growing under mixotrophic conditions (culture W) (Fig. 7a), compared to the autotrophic culture, despite the increase in cyanobacterial biomass (Fig. 3). This can be attributed to the high bioavailability of organic carbon provided by the presence of whey, which allows Oscillatoria sp. to grow while restricting photosynthesis [33]. During mixotrophy, cyanobacteria can utilize both inorganic (CO2) and organic carbon sources. The increase in carbon availability can result in faster growth and higher biomass yield, as observed in Fig. 3. However, the presence of organic carbon alters the balance of cellular processes, leading to a decrease in the production of photopigments (Fig. 7). Hence, pigments reduction indicates a shift in metabolic priorities, with cells relying more on heterotrophic metabolism (i.e., organic carbon utilization) and less on photosynthesis. Additionally, the turbidity in culture W as shown in Fig. 7b, caused by the presence of whey, hinders light penetration and its capture by cells, thereby affecting photopigment biosynthesis [39].

While mixotrophic growth of Oscillatoria sp. offers the advantage of utilizing organic matter, beneficial for cheese whey bioremediation and boosting biomass, this strategy leads to a decrease in photopigments. Oscillatoria shows potential for dairy wastewater treatment, but the trade-off is a reduction in the biosynthesis of valuable feed ingredients. Despite this, the increased cyanobacterial biomass yield offers significant applications, such as biosorbents for heavy metal and dye removal from wastewater, biochar production, and potential use as a biofertilizer in agriculture [22, 41, 42]. However, before applying such biomass in environmental or agricultural contexts, safety considerations must be addressed. Future studies should therefore assess the potential accumulation of harmful compounds or toxin production by the cyanobacterial biomass. Additionally, post-harvest treatments, such as thermal inactivation, anaerobic digestion, or pyrolysis, may enhance the safe reuse of the biomass as biosorbent material, biofertilizer, or feedstock for bioenergy, in line with circular bioeconomy and waste valorization strategies.

In this study, we investigated the potential of the mixotrophic Oscillatoria sp. to assimilate organic matter from real cheese whey. Our results demonstrated that the cyanobacterium effectively metabolizes carbohydrates and proteins from whey, transitioning from a predominantly photosynthetic mode to utilizing exogenous carbon sources. This metabolic shift led to a reduction in chlorophyll a and total carotenoid content compared to autotrophic growth. Notably, the high acidity of the cheese whey did not induce oxidative stress or impair cyanobacterial metabolic activity. Furthermore, Oscillatoria sp. significantly reduced the chemical oxygen demand of the whey and adjusted the effluent pH to levels suitable for safe disposal. Under mixotrophic conditions, the culture yielded higher biomass after 28 days. These findings underscore the potential of using Oscillatoria sp. in milk-processing effluent treatment while simultaneously enhancing cyanobacterial biomass production for further valuable applications. However, considerations around biomass safety and reuse pathways must be addressed through further contaminant profiling and regulatory assessment.

The datasets used and analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

ICB: methodology; validation; investigation; supervision. DL, SF, and DC: conceptualization; methodology; investigation; formal analysis; visualization. DB: methodology; validation; resources; supervision. LDL: investigation; formal analysis; writing—original draft. LMP: conceptualization; formal analysis; validation, visualization, writing—review and editing, supervision, project administration, funding acquisition. DL, SF, and DC contribute equally to this work. All authors contributed to editorial changes in the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript. All authors have participated sufficiently in the work and agreed to be accountable for all aspects of the work.

Not applicable.

The authors want to express their gratitude to Milkaut S.A. (Argentina) and the National Institute of Agricultural Technology (INTA-Rosario, Centro Regional Santa Fe, Argentina) for providing the acid whey and Oscillatoria sp. culture. I.C.B. thanks to the National Council for Scientific and Technical Research (CONICET, Argentina) for the doctoral fellowship.

This research was funded by grants provided by the Pontifical Catholic University of Argentina (UCA), project number pj00286 (https://repositorio.uca.edu.ar/cris/project%20/pj00286), and supported by a doctoral scholarship from the National Council for Scientific and Technical Research (CONICET, Argentina).

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

Publisher’s Note: IMR Press stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.