1 Department of Microbiology, College of Veterinary Medicine, Baghdad University, 10071 Baghdad, Iraq

2 Department of Environmental Biotechnology, Biotechnology Research Center, Al-Nahrain University, 64074 Baghdad, Iraq

Abstract

The E. coli O157:H7 strain has been the subject of many studies. In addition to producing severe abdominal illness in humans and animals, the E. coli O157:H7 strain is characterized by the production of Shiga toxins and demonstrates resistance to multiple antibiotics.

In this study, 20 fecal samples from patients with typical symptoms of E. coli O157:H7 infection and 20 from animals that tested positive for the same pathogen were analyzed. The bacterium was isolated, identified, and classified using both culture-based and molecular methods, employing the rpoB, stx, waa, and waaO genes.

The E. coli O157:H7 strain classification was highly similar to the E. coli O157:H7 strain Sakai. The rpoB, stx, waa, and waaO genes were deposited on the NCBI website under accession numbers PP059841, OR939814, PP059843, and PP059842, respectively. The mutant sequences at the waa sites K, L, and Y were analyzed to determine the alterations in the associated gene function, cell wall formation, and the ability of the mutant E. coli O157:H7 to develop antibiotic resistance compared to the wild-type.

Antibiotic resistance in the mutant E. coli O157:H7 increased significantly regarding some type of theses antimicrobial agents, while in some cases it decreased. This depends on the type of antibiotics and its mode of action and target. This may be explained by the waaK and waaL genes, which prevent the entry of antimicrobial agents into the bacterial cell.

Keywords

- E. coli O157:H7

- microbial pathogenesis

- bacterial cell wall modification

- site-directed mutagenesis

The Shiga-toxin-producing E. coli O157:H7 (STEC) strain was first identified in 1982 as a human pathogen after specimens were obtained from patients with unusual bloody diarrhea and abdominal pain, followed by watery diarrhea 24 hours later [1]. STEC is already recognized as a zoonotic pathogen that causes worldwide outbreaks [2], characterized by virulence factors including Shiga toxins 1 and 2 [3, 4]. Additional virulence factors have been identified, represented by plasmid-encoded enterohemolysin (EhxaA), autoagglutination adhesion (Saa), a catalase-peroxidase (KatP), and an intestine-damaging extracellular serine protease (EspP) [5]. The STEC strain is also known as enterohemorrhagic E. coli (EHEC) and can cause hemorrhagic colitis (HC), which can be a life-threatening sequelae, as well as hemolytic uremic syndrome (HUS) [6]. This bacterium was also isolated from animal stock. The prevalence of such infections may lead to reduced animal production, especially poultry and large animals, due to abdominal sepsis, urinary tract infection (UTI), blood poisoning, and diarrhea [7].

E. coli O157:H7 is transmitted through contaminated food, dairy products, and vegetables exposed to animal feces [8, 9]. Notably, large animals, such as sheep and cattle, are the fundamental reservoirs of E. coli O157:H7 [10]. Indeed, the feces from these animals can transmit diseases to individuals who come into contact with contaminated products, such as those contaminated with animal excrement, as seen in butchers, as well as water and soil [11]. Moreover, pets, such as birds and dogs, can be considered a potential route of infection [12].

Intestinal colonization of E. coli O157:H7 is accompanied by damage to the lining cells due to Shiga toxin production [13]. This bacterium can resist the host defense mechanism and mimic part of the normal intestinal flora [14, 15]. Thus, adhesion to intestinal epithelial cells is considered the first evolutionary step in STEC. Additionally, the interaction and binding patterns of STEC and epithelial cells are unique for eae-negative STEC strains [16]. Therefore, many EHEC are eae-positive, and the eae gene is considered a risk factor for HUS [17].

The E. coli O157:H7 name was designated owing to the ability of the

strain to express somatic (O) antigens with flagellar antigen [7], unique

criteria to delay D-sorbitol fermentation for more than 24 hours, and production

of

The primary gene(s) responsible for cell wall formation are a set of genes called waa; these genes were formerly known as Rf. These genes are responsible for forming the core oligosaccharide (core OS), a significant component in the E. coli outer membrane [19]. This core domain is divided into the inner and outer cores depending on the sugar composition [20]. Mutations in the waa region promote the formation of truncated lipopolysaccharide (LPS). In E. coli, the region is arranged according to three operons: waaD, waaF, and waaL, which encode proteins involved in transferring the heptose molecule into the inner core of the LPS.

In contrast, waaL encodes the ligase enzyme required for attaching the O antigen. The second operon which contains waaG, waaI, waaJ, waaB, waaQ, waaK, waaY, waaP, waaS, and waaZ, alongside waaQ and waaK, encodes heptotransferase, which adds the third and fourth heptose residues [21]. Studies have shown that a mutation in the waa region is often associated with a pleiotropic phenotype termed deep-rough [22].

The E. coli O157:H7 genome size is 5.5 Mb, with a 4.1 Mb backbone sequence that is conserved in E. coli strains [20]. A comparison of the E. coli O157:H7 genome size with that of non-pathogenic E. coli revealed an approximately 0.53 Mb difference in the E. coli O157:H7, suggesting that an evolutionary mechanism removed a region during the introduction of this strain [22, 23]. Most of the E. coli O157:H7 DNA, comprising 1.4 Mb, was identified as horizontally transferred foreign DNA composed mainly of prophage and prophage-like elements. Thus, from an evolutionary perspective, E. coli O157:H7 is considered a descendant of E. coli O55:H7, which is less virulent and non-toxigenic. Hence, E. coli O157:H7 has evolved through multiple steps, including the acquisition of stx1 and stx2 bacteriophages, as well as the acquisition of pO157 and the rfb region [24].

Antibiotic resistance is one of the characteristics of E. coli O157:H7 that contributes to increased pathogenicity. E. coli is highly resistant to quinolones, aminoglycosides, macrolides, cephalosporins, sulfonamides, fluoroquinolones, tetracyclines, and trimethoprim [24]. In addition to the occurrence of E. coli O157:H7, the spread of antibiotic-resistant bacteria and multidrug-resistant zoonotic foodborne pathogens has become a worldwide health concern [25]. Studies conducted in various parts of the world have indicated a significant increase in antimicrobial resistance of E. coli O157:H7, which has heightened the potential of this strain as a public health threat. The main factor in antibiotic resistance is the possession of resistance genes, such as CITM, blaSHV, cat1, cmlA, qnr, aac(3)-IV, sul1, tetA, tetB, and dfrA1 [26]; however, the cell wall and the shape transition of the cell may also play a critical role in this mechanism [27]. This change can be observed in the surface area to volume (S/V) ratio [26]. Indeed, a reduction in the S/V ratio was observed in E. coli upon treatment with antibiotics that inhibit the ribosome and target the cell wall [28, 29]. Previous literature [30, 31] has addressed the chemical modification, destruction of the antibiotic, or changes in the cell wall structure that inhibit antibiotic action. However, the molecular mechanisms underlying these changes require clarification, which is the focus of the planned research.

Therefore, this study aimed to investigate the effect of cell wall mutations on the development of antimicrobial resistance by targeting specific genes that play a major role in synthesizing this essential component of bacterial structure, and how this change contributes to the development of antimicrobial resistance.

The Biotechnology Research Center’s IRB at Al-Nahrain University issued ethical approval for animal welfare with reference no. PG/244, following EU Directive 2010/63/EU.

The study was conducted in accordance with the principles outlined in the Declaration of Helsinki.

The Biotechnology Research Center at Al-Nahrain University obtained approval for human sample collection after patients provided written consent—an ethical approval document with the number C.B 242 was issued for this purpose.

Following the Helsinki declaration, a total of 40 fecal samples and watery intestinal exudates were collected from patients residing at Al-Yarmouk Teaching Hospital and Al-Kindy Teaching Hospital. Samples were collected from patients after obtaining written consent for participation in this study. Samples were immediately processed at the clinical laboratories of the hospitals by cultivating them in nutrient broth and then transferring them after 24 hours to the university laboratories for further processing.

Furthermore, 40 additional animal feces samples were collected from large animals with symptoms of diarrhea, cold extremities, dizziness, and difficulty standing. Samples were preserved in a transport medium and transferred to the university laboratories in a cool box. Upon arrival, these samples were diluted with sterile normal saline and cultured in nutrient broth for 24 hours to allow bacterial growth.

Samples enriched in nutrient broth were diluted to 106, and cultivated on MacConkey agar (Oxoid, Leicester, UK) at 37 °C for 24 hours. Colorless colonies were transferred and spread on eosin methylene blue (EMB) agar (Hi Media, New Delhi, India), and then incubated at 37 °C for 24 hours. E. coli colonies that presented a metallic sheen were selected and cultivated on Hi Chrome medium with supplements (Hi Media, New Delhi, India) at 37 °C for 24 hours. The E. coli O157:H7 colonies appeared to have a dark purple to magenta color.

DNA was extracted using the GenX total DNA extraction kit (London, UK) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. On average, about 105 mg of DNA was obtained, with a purity of 1.8 as measured by a NanoDrop system (Techne, London, UK). DNA samples were preserved at –20 °C until processing.

E. coli O157:H7 possesses a unique set of genes that can be easily identified. Genes that were detected in the isolate under study were as follows:

2.3.2.1 The rpoB Gene

The rpoB gene was amplified using sequence-specific primers based on the gene sequence deposited in the NCBI database under accession number JX471606. The sequences of the primers were as follows: rpo F: 5′–CAGCCAGCTGTCTCAGTTTAT–3′; rpo R: 5′–GGCAAGTTACCAGGTCTTCTAC–3′. The Thermocycler (LabNet, MA, USA) program was one cycle of denaturation at 95 °C for 2 min, followed by 35 cycles of denaturation at 94 °C for 30 s, annealing at 49 °C for 30 s, and extension at 72 °C for 30 s. After the 35 cycles were completed, the samples were subjected to a final extension at 72 °C for 10 min, and then held at 4 °C until removed from the thermocycler. The obtained amplicons were preserved at –20 °C until required for electrophoresis.

2.3.2.2 The waa Gene

The waa gene was amplified using specific primers designed based on its accession number. M95398 in the NCBI database. The primer sequences were as follows: waa F: 5′–CACTAATTTTACGTGGCAGAC–3′; waa R: 5′–CCCATATGATCACATCAACTGA–3′. The thermocycler program was one cycle of denaturation at 95 °C for 2 min, followed by 35 cycles of denaturation at 94 °C for 30 s, annealing at 59 °C for 30 s, and extension at 72 °C for 30 s. After the 35 cycles were completed, the samples were subjected to a final extension at 72 °C for 10 min, and then held at 4 °C

2.3.2.3 The Shiga toxin stx Gene

In the initial survey, the bacterial isolate under study was found to produce Shiga toxin type 1. For this reason, the following primers were designed to amplify the stx1 gene depending on the accession number. OM304351 in the NCBI database. The primer sequences were as follows: stx F: 5′–CAGTTAATGTCGTGGCGAAGG–3′; stx R: 5′–CACCAGACAATGTAACCGCTG–3′. The stx gene was amplified using the following thermocycler program: 95 °C (1 cycle), denaturation at 94 °C for 30 s, annealing at 55 °C for 30 sec., and extension at 72 °C for 30 sec (35 cycles). The final extension was conducted at 72 °C for 10 min, and the samples were then held at 4 °C.

2.3.2.4 The waaO Gene

The waaO was targeted for amplification by PCR using specific primers designed against the gene sequence, depending on the accession number. X59852 from the NCBI database. The primer sequences were as follows: waaO F: 5′–CGTGATGATGTTGAGTTG–3′; rfo R: 5′–AGATTGGTTGGCATTACTG–3′. Amplification of the target gene by PCR was performed under the following conditions: one cycle of initial denaturation at 95 °C for 2 min, followed by 35 cycles of denaturation at 94 °C for 30 s, annealing at 59 °C for 30 s, and extension at 72 °C for 30 s. The final extension was performed at 72 °C for 10 min, and the samples were maintained at 4 °C until ready to be removed from the thermocycler.

The cell wall controlling the waa gene was targeted for mutagenesis. The specific primers were designed using the software available at https://nebasechanger.neb.com. The generated primers have the following sequence: mutF 5′ cgcacatcctttaaacttcattcattg 3′, and mutR 5′ catttaattaattgtattgttacgattattaatg 3′. The mutagenesis PCR conditions performed were as follows: initial denaturation at 95 °C for 2 min (1 cycle), followed by 30 cycles of denaturation at 94 °C, annealing at 60 °C for 1 min, and extension at 72 °C for 1 min; the final extension step was performed at 72 °C for 10 min, and samples were held at 4 °C after the reaction was completed.

The same primer used for site-directed mutagenesis was employed, with one notable exception. This included the addition of a specific sequence recommended by the cloning kit manufacturing company, which involves incorporating a complementary sequence into the cloned DNA fragment to clone the sticky ends of the vector. The complete sequences of these mutC primers are F: 5′–TCAGCAAGGGCTGAGGcgcacatcctttaaacttcattcattg–3′; mutC R: 5′–catttaattaattgtattgttacgattattaatgGGGAGTCGAAGGCGACT–3′. The capital letters in the sequences represent the sticky end additions. In addition, the PCR program was identical to the site-directed mutagenesis protocols, except that the annealing temperature was set to 63 °C.

The PCR product of the waa gene was used as a template for the mutagenesis experiment. A 2 µL sample of waa PCR amplification product was mixed with 1 µL of mutC F and 1 µL of mutC R (final concentration of 0.5 pmol/µL for each primer) in a master mix tube (Bioneer, Seoul, South Korea) and subjected to PCR amplification: initial denaturation at 95 °C for 2 min (1 cycle), followed by 30 cycles of denaturation at 94 °C, annealing at 62 °C for 1 min, and extension at 72 °C for 1 min; the final extension step was performed at 72 °C for 10 min, and the samples were held at 4 °C.

Cloning of the mutated waa gene was performed using NZYEasy Cloning and

Expression kit MB324 (NZYTech, Lisbon, Portugal). The kit contains the following

components: 10

The transformation procedure was performed for both competent cells (NZYTech DL3 star E. coli) and the wild-type. The transformation protocol was achieved through the following steps: a volume of 10 µL of the ligation product obtained from the cloning experiment was mixed directly with 100 µL of recipient cells and placed on ice for 30 min. The mixture was removed and subjected to a heat shock at 42 °C for 40 s, then placed on ice for 2 min. A volume of pre-warmed Super Optimal broth (SOC) medium was added to the cells, and the cell suspension was incubated at 200 rpm and 37 °C for 1 hour. Cells were then precipitated by centrifugation at 5000 rpm for 1 min, and the remaining medium was removed. After the precipitation step, the cells were gently resuspended by pipetting, and 100 µL of the cell suspension was spread on Luria-Bertani medium (LB) agar plates containing 50 µg/mL kanamycin. The plates were incubated at 37 °C overnight, which allowed only the transformants to grow.

The same protocol was used to transform wild-type E. coli, with one modification: cells were treated with lysozyme (10 µg/mL) at 4 °C for 1 hour before proceeding with the transformation protocol.

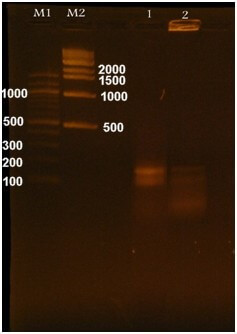

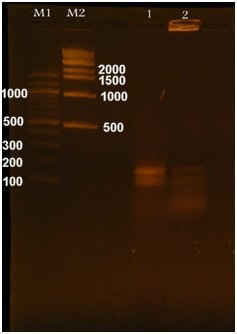

The confirmation of cloning with a mutated gene was performed by electrophoresis. 2 µL of standard mixture (pHTP9) only, and cloned product (pHTP9 with mutated gene) were subjected to PCR amplification using mutC F, mutCR primers, and pH F: 5′–GAATGAAAAACGCGACCACATGGTG–3′, pH R: 5′–GGTTATGCTAGTTATTGCTCAGCG–3′ primers designed by NZYTech company specifically to detect pHTP9 vector. The difference in DNA bands resolved by electrophoresis differentiates between the standard cloning product and the one with the mutated gene.

In addition, the selection of transformants was performed in two steps: first, only transformed cells with pHTP9 could grow on kanamycin-supplemented medium due to the resistance gene in the plasmid, which implemented positive selection; second, colony PCR was performed using the same procedure as that used to detect a successful cloning experiment.

All PCR products were resolved by electrophoresis using 1.5% agarose gels and a field strength of 8 V/cm. Gels were stained with ethidium bromide at a concentration of 10 mg/mL for 30 min and visualized under ultraviolet (UV) transilluminators (MS Scientific, Boston, MA, USA). Two types of DNA markers, 100 bp and 1000 bp, were used, depending on the resolution required for the DNA band.

PCR products were sent to Macrogen Corp. (Seoul, South Korea) for sequencing using the Sanger method.

Sequences obtained from PCR amplification were analyzed using available tools at the NCBI website: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov, including BankIt https://submit.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/about/bankit/, BLASTN https://blast.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/Blast.cgi?PROGRAM=blastn&PAGE_TYPE=BlastSearch&LINK_LOC=blasthome, BLASTX, and Phyre2, which is available at: http://www.sbg.bio.ic.ac.uk/phyre2/html/page.cgi?id=index.

The Statistical Package for Social Sciences (SPSS 2018 version 24, IBM Corp. Chicago, IL, USA) was used to conduct the statistical analysis. The parameters measured during the study were used to calculate the least significant difference (LSD), which indicates the difference among the groups being tested.

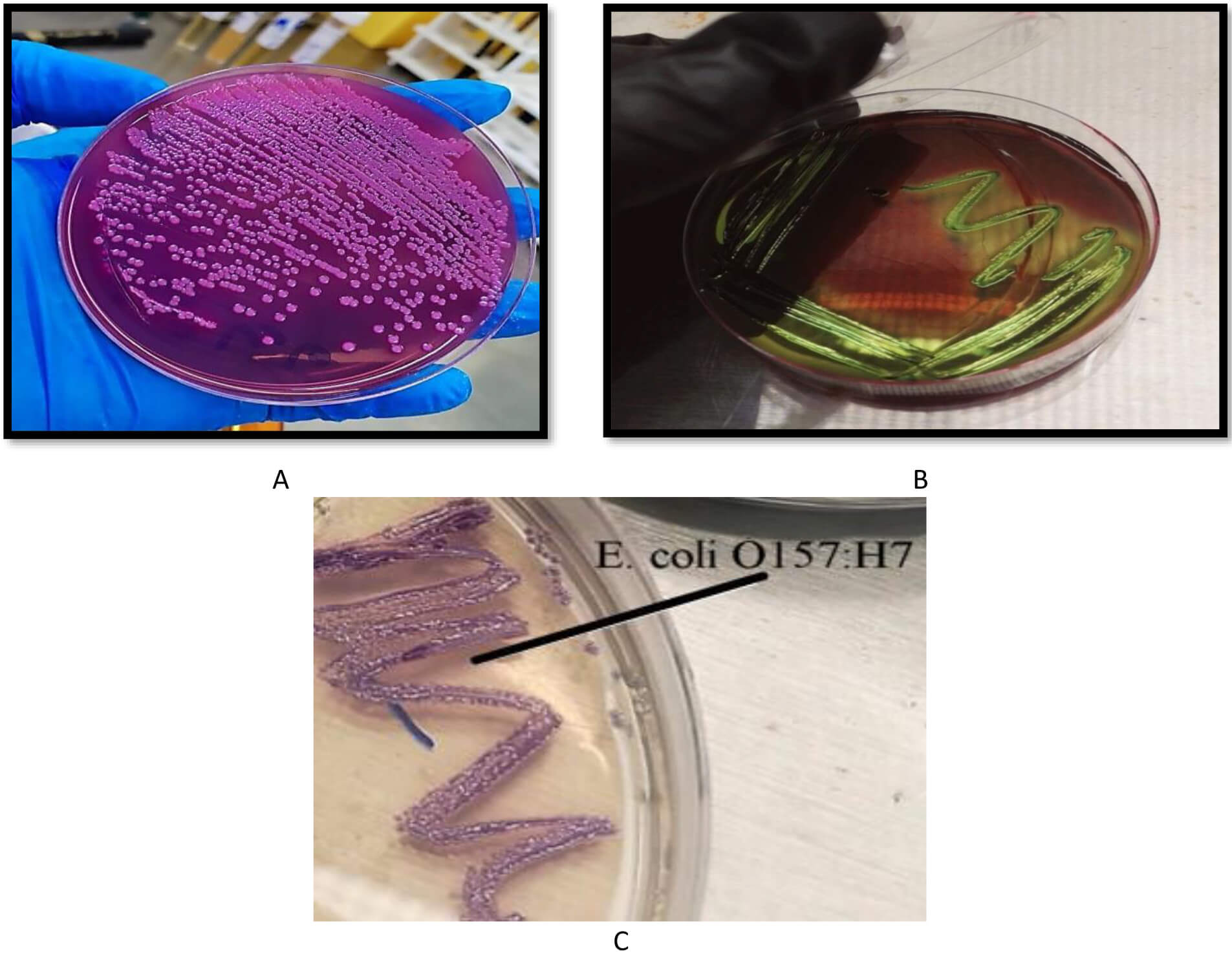

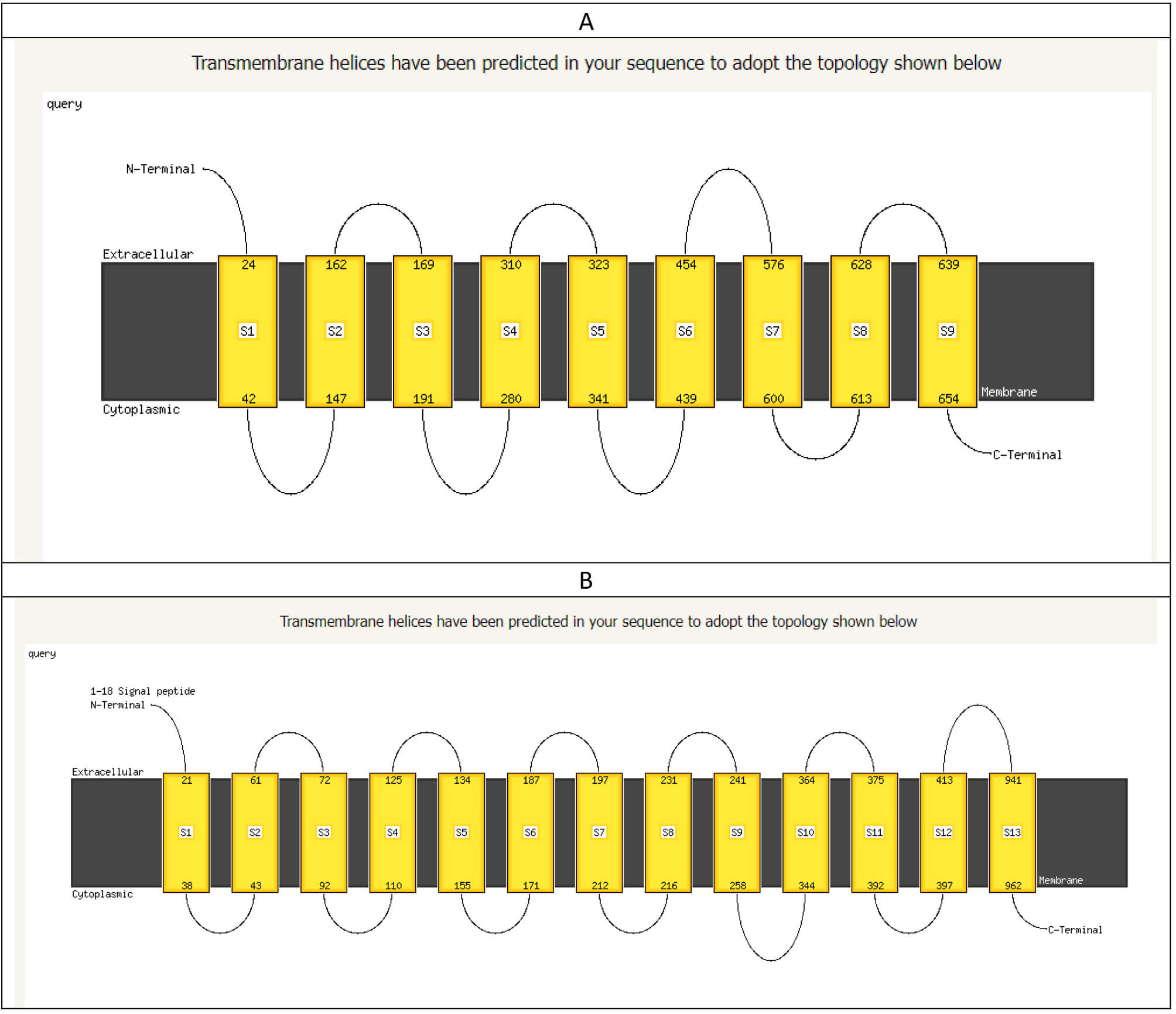

Among a total of 80 samples (40 from humans and 40 from animals), only 20 from each group were positive for E. coli. The initial isolation of the bacterium was performed by culturing the diluted samples on MacConkey agar. Colonies that appeared transparent in this medium were transferred to culture in EMB agar. After incubation at 37 °C for 24 hours, E. coli seemed to grow with a metallic sheen and a dark center. Colonies were grown on Chrome agar to differentiate between E. coli and E. coli O157:H7. Colonies with a mauve color, which is a characteristic of E. coli O157:H7, were selected to continue this study. Fig. 1 shows the growth of E. coli O157:H7 on different media.

Fig. 1.

Fig. 1.

Growth of E. coli O157:H7 on different media. (A) MacConkey agar, where the colonies appear transparent, (B) eosin methylene blue (EMB) agar, where the colonies appear with a metallic sheen, and (C) chrome agar, where the colonies appear with a mauve color.

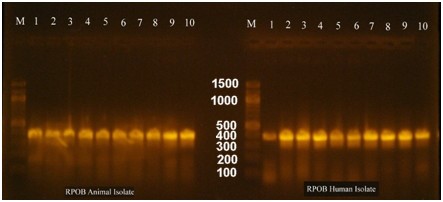

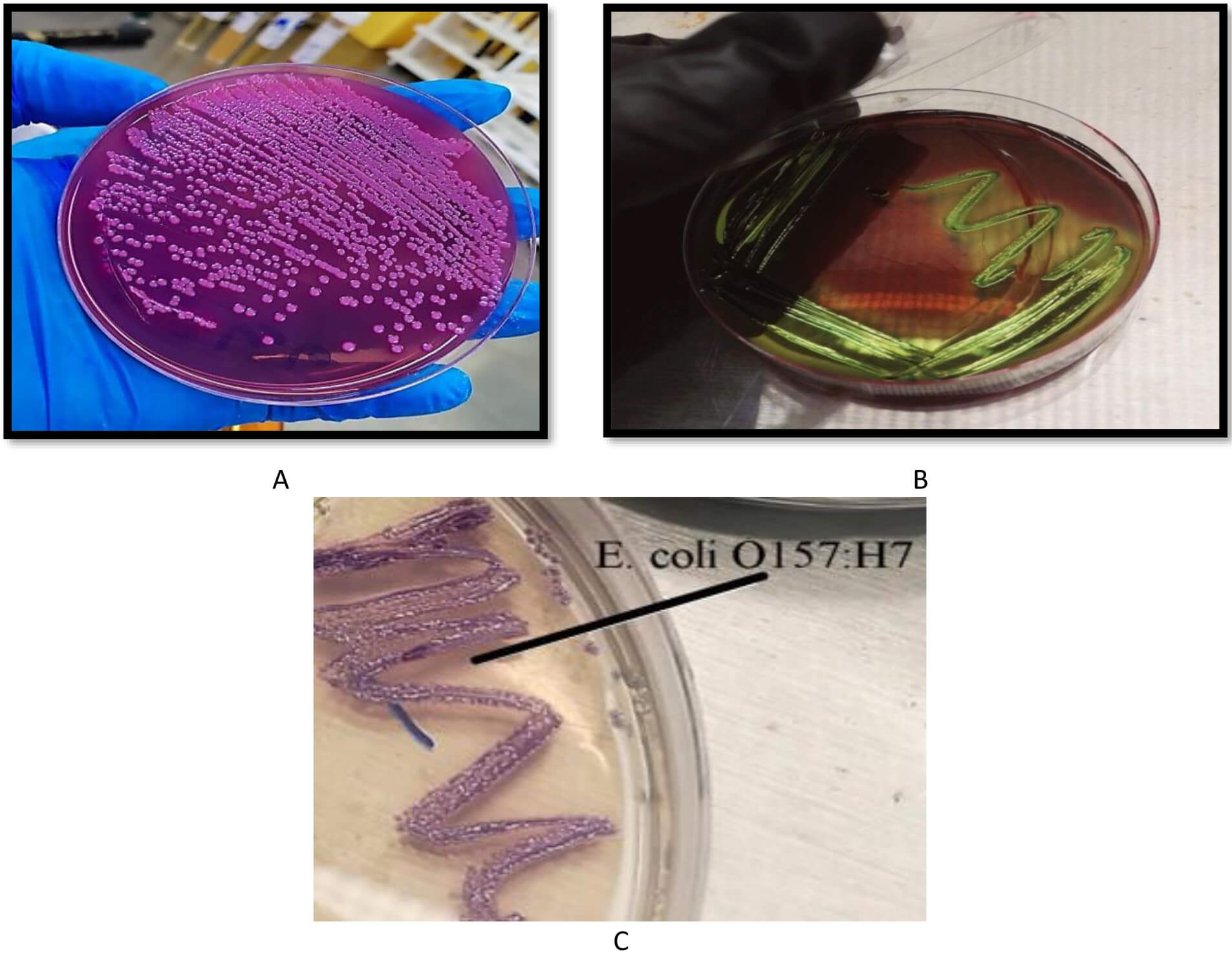

During this study, we used the rpoB gene to identify and classify the bacterium. The rpoB gene was amplified and sequenced, and the BLAST tool was used for identification. The result showed that the rpoB gene belongs to the E. coli O157:H7 strain Sakai, and our sequence was deposited in the NCBI database with the accession number PP059841. Fig. 2 shows the electrophoresis results for the rpoB gene in the human and animal samples.

Fig. 2.

Fig. 2.

Electrophoresis of the amplified rpoB gene from PCR for both animal and human isolates. M is a 100 bp DNA marker, whereas the numbers from 1 to 10 are the no. of E. coli O157:H7 isolates. Electrophoresis was performed in a 1.5% agarose gel for 1 hour under a field strength of 8 V/cm. The gene size of rpoB was determined to be 400 bp.

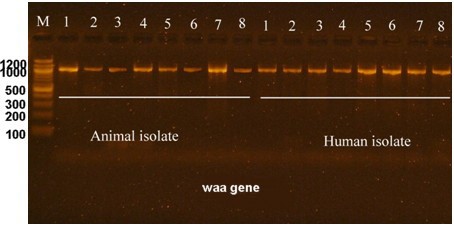

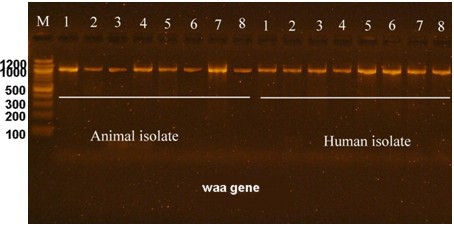

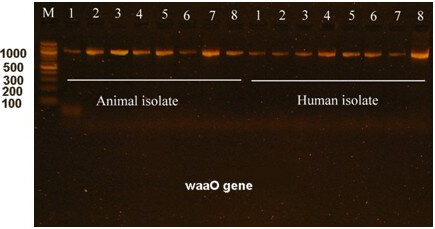

The waa gene was amplified by PCR using specifically designed primers. The amplicons were sequenced and analyzed. The results showed that the waa gene belongs to the E. coli O157:H7 strain Sakai, and it was deposited in the NCBI database with the accession number PP059843. Fig. 3 shows the electrophoresis of the waa gene obtained from PCR amplification.

Fig. 3.

Fig. 3.

Amplification of the waa gene from animal and human E. coli O157:H7 isolates. M is a 100 bp DNA marker, whereas the numbers from 1 to 8 represent the number of E. coli O157:H7 isolates. Electrophoresis was performed in a 1.5% agarose gel for 1 hour under a field strength of 8 V/cm. The waa gene size was 1100 bp.

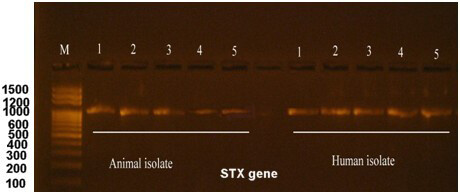

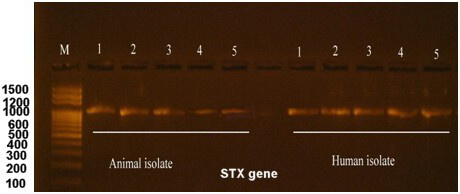

The production of the Shiga toxin is a primary characteristic of E. coli O157:H7. Our initial survey to identify the type of Shiga toxin revealed the presence of the type 1 toxin, which was subsequently amplified by PCR and subjected to further analysis. The obtained sequence was deposited in the NCBI database under the accession number OR939814. Fig. 4 shows the electrophoresis of the stx1 gene.

Fig. 4.

Fig. 4.

Electrophoresis of the stx1 gene after amplification by PCR for both human and animal isolates. M is a 100 bp DNA marker, whereas the numbers from 1 to 5 are the no. of E. coli O157:H7 isolates. Electrophoresis was performed in a 1.5% agarose gel for 1 hour under a field strength of 8 V/cm. The Stx1 gene size was calculated to be 600 bp.

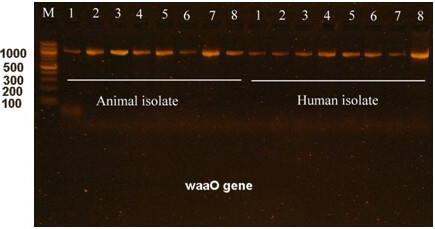

The waaO gene is a characteristic of E. coli O157:H7. The waaO gene encodes the O antigen, which is a major component of the bacterial cell wall. During this study, the waaO gene was targeted for amplification and sequencing, and found to be similar to the E. coli O157:H7 strain Sakai. The sequencing data were deposited on the NCBI website with an accession number PP059842. Electrophoresis of the amplified waaO gene is shown in Fig. 5.

Fig. 5.

Fig. 5.

Electrophoresis of the waaO gene in E. coli O157:H7 isolated from humans and animals. M is a 100 bp DNA marker, whereas the numbers from 1 to 8 are the no. of E. coli O157:H7 isolates. Electrophoresis was performed in a 1.5% agarose gel for 1 hour under a field strength of 8 V/cm. The waaO gene size is 1200 bp.

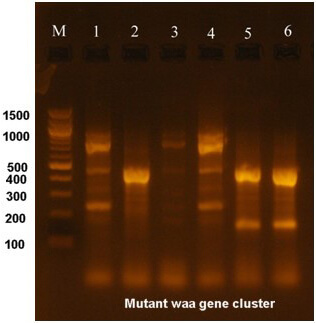

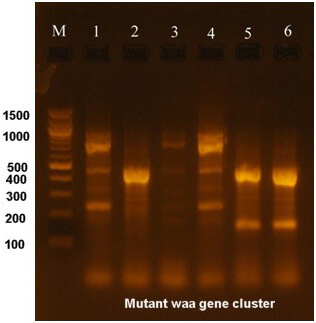

The waa gene, which was PCR amplified, was subjected to mutagenesis using specifically designed primers. These primers targeted the protein-coding sequences, resulting in highly different types of gene products that will be incorporated into the cell wall. The site-directed mutagenesis result for the waa gene is shown in Fig. 6.

Fig. 6.

Fig. 6.

Electrophoresis of the mutated waa gene amplified from E. coli O157:H7. M is a 100 bp marker DNA. Lanes 1, 2, and 3 represent the mutated waa gene from the animal isolate, whereas lanes 4, 5, and 6 represent the mutated waa gene in the human isolate.

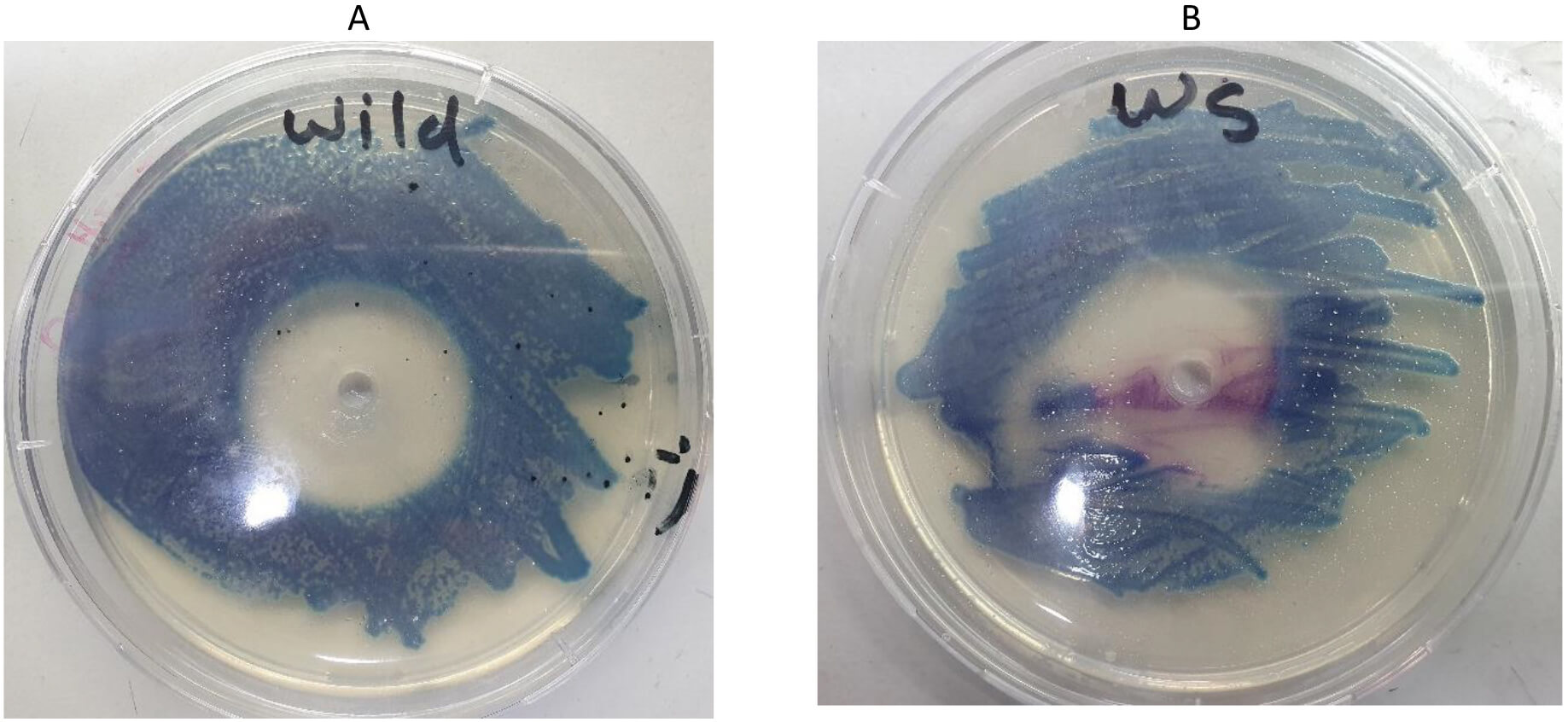

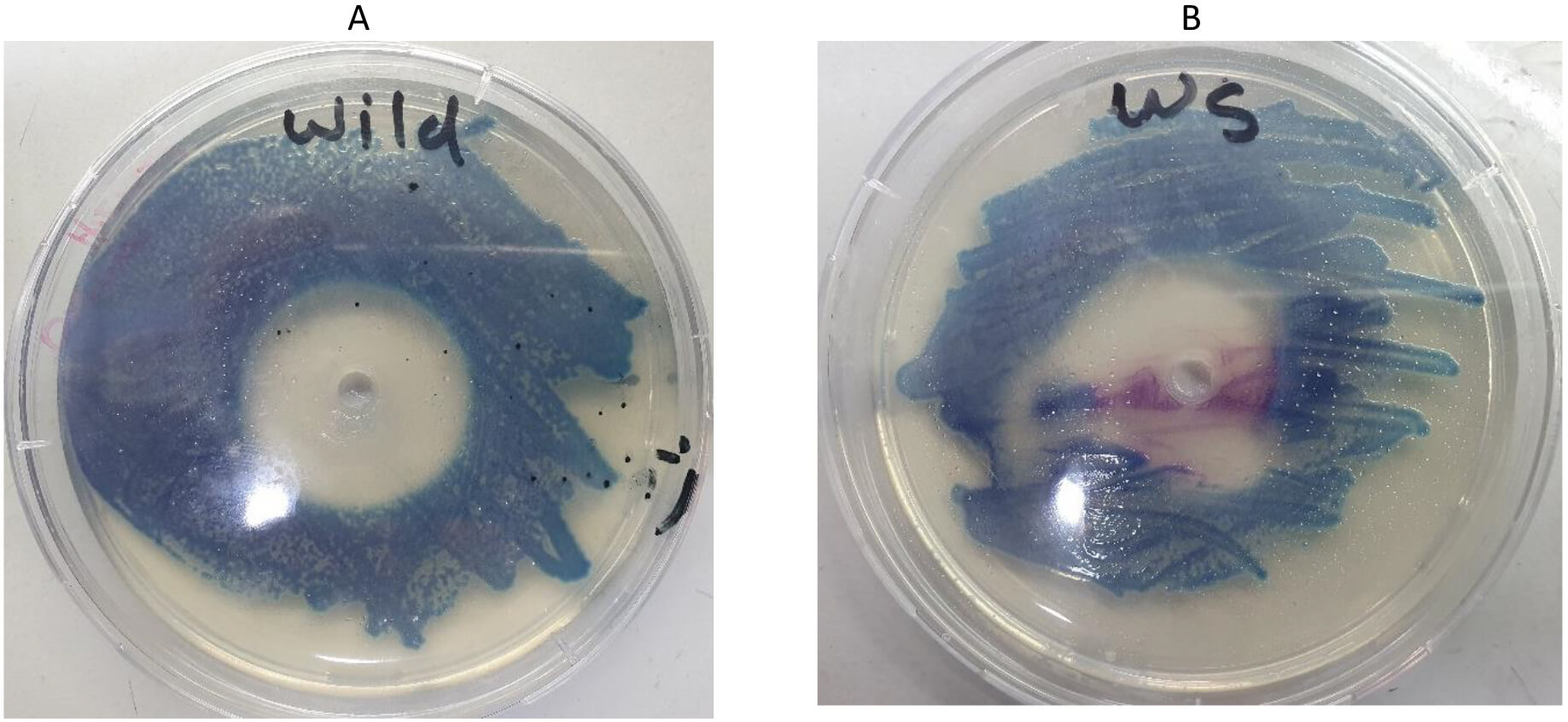

The mutated waa gene was cloned into the pHTP9 cloning vector. The generated mutated DNA fragment exhibited a single difference: a complementary sequence to the sticky ends of the cloning vector was added to the primers used in the site-directed mutagenesis, as described in the Methods section, to facilitate ligation during the cloning process. The product of the cloning experiment was used to transform the competent and wild-type strains. Positive selection was the basis on which transformants were selected, as these colonies could resist kanamycin due to the resistant gene harbored by pHTP9. When transformants were able to grow on LB agar supplemented with kanamycin, we performed colony PCR using primers (mutC) and (pH) to target the mutated gene and specific sequence on pHTP9, respectively. This confirmed successful transformation procedures. Fig. 7 shows the growth of the transformants on kanamycin-supplemented LB medium compared to normal cells, whereas Fig. 8 shows the colony PCR result.

Fig. 7.

Fig. 7.

Antibiotic susceptibility of E. coli O157:H7 to kanamycin on Hi-chrome agar. (A) Wild-type bacterium with a wide inhibition zone. (B) The cell line transformed with pHTP9 was able to grow in the presence of kanamycin (magenta-colored colonies).

Fig. 8.

Fig. 8.

PCR amplification of the mutated gene and pHTP9. M1 is a 500 bp DNA marker, and M2 is a 100 bp DNA marker. Lanes 1 and 2 represent the amplification results of the mutated gene and the pHTP9-specific sequence, respectively, following the cloning experiment and colony PCR.

Targeting specific sites in the waa gene for mutation, specifically those involved in the biosynthesis of core lipopolysaccharide (waaY and waaZ), the site engaged in O-antigen encoding (waaL), and the gene controlling transcription (waaH), resulted in an alternative type of protein with different criteria that included function conservation and mutational sensitivity compared to the wild-type proteins.

The waaH gene is responsible for the regulatory DNA binding that results in a DNA/RNA/protein complex. Therefore, mutating this site can dramatically alter the regulatory function and change the associated mutation sensitivity. Supplementary Table 1 illustrates the change in this gene criterion.

The waaK gene is responsible for N-acetylglucosamine transferase synthesis, and its product is involved in modifying the LPS core before it is attached to the O-antigen. This site was identified for site-directed mutagenesis to investigate the effect of the newly encoded protein on the bacterium. The results are provided in Supplementary Table 2.

The waaL gene product is involved in core modification and O-antigen coding. The specific criteria resulting from a mutation in this gene are detailed in Supplementary Table 3.

The waaZ has a function in LPS core integration but is not involved in O-antigen construction. As a secondary gene in LPS formation, the characteristics associated with a mutated waaZ gene were not studied. However, the changes in related gene functions are listed in Supplementary Table 4.

The role of the waaY gene is to decorate and modify the cell, which increases the LPS size. Hence, a mutation in the waaY gene was created to investigate specific criteria that may be crucial for cell wall formation; the associated changes are presented in Supplementary Table 5.

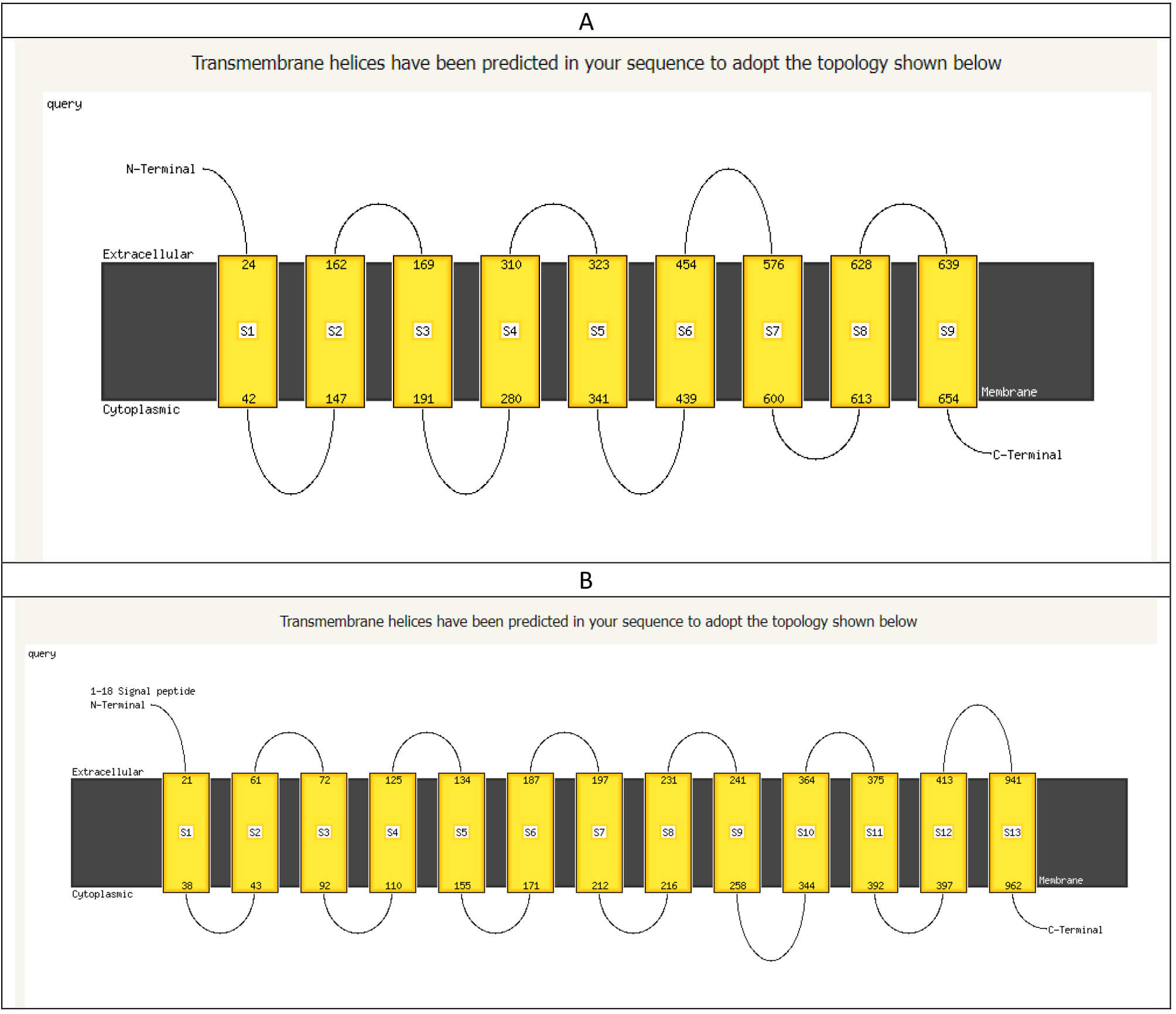

In all types of bacteria, the cell wall is characterized by a specific topology that enables the exchange of chemical and biochemical compounds, allowing for efficient interactions with the environment. Thus, modifying the protein structure in the cell wall may lead to a corresponding change in its topology. In our experiment, the topology of the cell wall in wild-type and the mutated E. coli was determined, and the data are provided in Supplementary Table 6.

Changes in the cell topology and conformation can affect bacterial susceptibility to antibiotics. This effect may extend to antibiotics that specifically target the cell wall, but may also include those that work on protein, RNA, and DNA synthesis. The impacts of the cell wall-related mutations on the response to antibiotic exposure are listed in Table 1.

| Antibiotic | Antibiotic group | Inhibition zone (mm)/wild E. coli O157:H7 | Inhibition zone (mm)/mutant E. coli O157:H7 | L.S.D. value |

| Amoxicillin | Penicillins | 6 | 6 | 0.00 (NS) |

| Amoxicillin/clavulanic acid | B-lactam combination agents | 6 | 6 | 0.00 (NS) |

| Piperacillin–tazobactam | B-lactam combination agents | 26 | 26 | 0.00 (NS) |

| Ceftazidime | Cephalosporins I, II, III, IV | 32 | 32 | 4.327 (NS) |

| Cefepime | Cephalosporins I, II, III, IV | 25 | 28 | 4.197 (NS) |

| Cefotaxime | Cephalosporins I, II, III, IV | 33 | 34 | 3.551 (NS) |

| Ceftriaxone | Cephalosporins I, II, III, IV | 18 | 20 | 3.065 (NS) |

| imipenem | Carbapenems | 34 | 34 | 5.88 (NS) |

| Meropenem | Carbapenems | 32 | 40 | 6.04 * |

| Aztreonam | Monobactams | 11 | 32 | 7.62 * |

| Gentamicin | Aminoglycosides | 11 | 6 | 4.95 * |

| Tobramycin | Aminoglycosides | 18 | 10 | 6.55 * |

| Amikacin | Aminoglycosides | 15 | 18 | 3.46 (NS) |

| Azithromycin | Macrolides | 17 | 17 | 4.796 (NS) |

| Doxycycline | Tetracyclines | 17 | 14 | 4.071 (NS) |

| Minocycline | Tetracyclines | 14 | 17 | 3.875 (NS) |

| Ciprofloxacin | Fluoroquinolones | 6 | 13 | 5.812 * |

| Levofloxacin | Fluoroquinolones | 6 | 15 | 5.923 * |

| Chloramphenicol | Phenicol | 21 | 6 | 5.702 * |

| Sulfamethoxazole/trimethoprim | Folate pathway antagonist | 6 | 6 | 0.00 (NS) |

| Nitrofurantoin | Nitrofurans | 21 | 20 | 2.961 (NS) |

| Trimethoprim | Folate pathway antagonist | 6 | 6 | 1.00 (NS) |

* (p

Foodborne infections are prominent in both developing and developed countries. A global study by the World Health Organization (WHO) found that 66 million people get infected from consuming unsafe water or food, with 33 million of those infected potentially dying. Diseases causing diarrhea are considered a serious threat to health and well-being. Among these diseases are those caused by E. coli [32], which can be easily distinguished from other bacteria using differentiation media. Since this strain is not a sorbitol fermenter, previous reports have suggested using MacConkey agar as a selective medium, as sorbitol is a useful marker to aid in the detection of E. coli O157:H7 from stools [33]. The greenish sheen produced by E. coli on the surface of the colony cultivated on EMB agar can provide a rapid and accurate method for differentiating the bacterium from other Gram-negative pathogens, which is pH-sensitive [34]. However, using Hi-chrome agar proved to be highly recommended in identifying E. coli O157:H7 from other types and species of the same genus. Further identification of E. coli O157:H7 can be performed using emerging high-throughput methods, such as isothermal DNA amplification, surface-enhanced spectroscopy, biosensors, and rapid paper-based diagnostic methods [6]. Furthermore, using stable genes, such as housekeeping genes, is another reliable approach that can identify the bacterium down to the strain level, as exemplified by rpoB, which was amplified, sequenced, and registered in the NCBI database under the accession number PP059842.

LPS is the main component of the outer membrane of Gram-negative bacteria, including E. coli. LPS comprises lipid A, an oligosaccharide core made of glucose, heptose, galactose, 2-keto-3-deoxyoctonate (KDO), and a highly variable component of the O-antigen. The location on the chromosome responsible for LPS synthesis is called waa, which is composed of three operons. Thus, mutations in waa may lead to truncated LPS with pleotropic effects on bacterial cells, resembling antibiotic sensitivity and susceptibility to bacteriophages [35]. Hence, studying these mutations in the E. coli O157:H7 cell wall may provide crucial insights into the pathogenicity, infectivity, and severity of symptoms associated with this bacterium.

The waaH site is of significant importance in cell wall formation. Previous reports have described an extreme case of virulence related to waaH modifications [36]. The dramatic change in waaH folding poses an intriguing problem due to the absence of all necessary information required to fully illustrate the folding process during the transformation [21]. In our study, multiple criteria associated with the waaH mutation were studied. The first criterion was the change in the three-dimensional (3D) structure of the encoded protein. The wild-type waaH protein was encoded as a transcriptional activator that promotes the expression of central cell surface waa components (suwaace) involved in the pathogenicity of E. coli [37]. Meanwhile, the reconstructed mutated waaH protein was shown to be a putative membrane antigen. Further analysis revealed a significant change in alpha-helix content, increasing from 11% in the wild-type to 28% in the mutants, and a decrease in beta-strand content, from 50% in the wild-type to 21% in the mutants. It is known that transcriptional control of waaH is mediated by binding with NusA and NusG, which are conserved bacterial elongation factors essential for bacterial viability [38]. The conformational change in the protein structure resulting from such binding may be altered. Studies on waaH have shown a shared mechanism for all Nus-like proteins from bacteria to humans, which acts as a processivity clamp for RNA polymerases; thus, any alterations may affect cellular function [37]. Such cellular function can be observed in the preservation of function and mutational sensitivity. Our finding showed that the function of waaH was highly affected by the mutation and the amino acid residues affected were Y, W, H, W, Y, P, C, W, P, W at locations 11, 14, 16, 23, 24, 36, 40, 42, 52, respectively, in the protein sequence when compared to the wild-type that showed highly conserved regions in which M, W, Y, L, L, P, F, T, F, P are found at positions 1, 4, 5, 14, 29, 31, 36, 66, 78, 85, respectively. When both findings were compared, we found that the preservation of waaH function begins with the start of the protein sequence, which may represent the binding site for the Nus-like protein to initiate the normal function of the gene that means its function is not vital to initiate cell formation. Moreover, in the wild-type, the mutational potential of waaH was very low and was mostly noted at the end of the protein sequence, whereas in the mutated gene, it was completely diminishedat the end of the residues, and the mutation-sensitive amino acids were identified in the middle of the protein. Such high functional preservation and low mutational potential can be explained on the basis that waaH is universally conserved by the Nus/Spt5 family of proteins, which co-evolved with RNA polymerase and function as housekeeping genes [39, 40].

The waaK gene region is responsible for encoding

N-acetylglucosamine transferase and participates in surface O-antigen

formation by providing the N-acetylglucosamine matrix providing a

non-stringent N-acetylglucosamine matrix [41]. In our study, the wild-type

waaK product was identified as UDP-glycosyltransferase/glycogen

phosphorylase, which is the normal protein produced from this location in the

waa cluster. Comparatively, the mutated sequence produced an identified

Ced A transcription factor. Through gene analysis, the protein showed a reduction

in the alpha-helix from 36% in the wild-type to 27% in the mutant, and a beta

helix from 13% to 22%. The interesting finding is that the loss of

transmembrane helices in the mutated gene was measured at 4% in the wild strain.

The function of the mutated gene was significantly diminished compared to the

wild-type, which showed a tendency to lose its function at residues distributed

throughout the DNA sequence of the gene. Moreover, the mutational potential at

this site appears to be high when tested under the Markov model, starting from

amino acid residue 1 and ending with residue 120, with short intervals among

them. In the previous report [42], it seems that the function of waaK is

the addition of

The waaL gene is the only gene known to be required for the O-antigen ligation during bacterial cell formation [44]. Although considerable information exists regarding waaL from in vivo studies, mutation analyses continue to be performed to understand the role of this gene [19]. In our research, the wild-type sequence was identified as a putative cell surface polysaccharide polymerase/ligase of the waaL O-antigen. However, following the introduction of the mutation at the waaL site, a beta-galactosidase enzyme was subsequently produced. The alpha helix reduced from 72% in the wild-type to 23% in the mutant, and the beta helix changed from 0% to 20% in the mutant. The significance of this mutation lies in the fact that the transmembrane helix in the wild-type bacteria was reduced from 52% to 12% in the mutant version. Consequently, such changes led to low function preservation represented by most amino acid residues along the encoded protein except for Y, W, H, W, P, Y, C, W, W, C, H, Y, C, and W, distributed at positions 8, 11, 13, 16, 21, 22, 46, 52, 62, 69, 73, 104, and 105, respectively. The mutational hotspots differed when comparing the two types of bacteria. The wild-type sites prone to mutation contained M, H, Y, C, L, W, Y, R, Q, P, and R, at positions 1, 8, 26, 29, 88, 152, 161, 215, 218, and 265, respectively. In contrast, the mutated bacteria possessed Y, W, H, W, P, Y, C, W, W, C, I, C, and W, at positions 8, 11, 13, 16, 21, 22, 46, 52, 62, 69, 73, 104, and 105, respectively. The waaL mutant is unable to cap lipid A-core with relaxed specificity for the polymer to which it attaches, and it is essential for O-antigen transfer to the cell, significantly contributing to cell wall topology [45]. Previous reports have shown that if the WAAL protein loses its function, it results in a full-length oligosaccharide core OS that is not capped by O-polysaccharide O-PS [46].

The waaZ gene was not identified in the E. coli R1, R3, and R4 core types, which suggests that the waaZ sequence is highly conserved in E. coli isolates with a specific core structure, signifying a shared function in core OS assembly. In our study, we successfully detected this sequence in E. coli O157:H7, and site-directed mutagenesis was performed to elucidate the associated characteristics. The wild-type waaZ sequence produced a protein with glycosyltransferase activity composed of 24% alpha helix, 14% beta helix, and a transmembrane helix of 8%, whereas the mutated protein produced a conserved domain protein with an alpha helix of 23%, beta helix of 20%, and an increased transmembrane helix of 12% compared to the wild-type. The mutated waaZ protein was non-functioning, but the amino acid residues at positions 8, 11, 16, 46, 52, 62, 104, and 105, which included Y, W, W, C, W, W, C, and W, retained their function as domain proteins. It seems that waaZ should be expressed in a controlled, specific amount, since the lack or overexpression of this gene product results in modified LPS and a truncated outer core with a reduced O-polysaccharide side chain [47].

The waaY and waaQ regions are located within the waaP gene responsible for the phosphorylation activity during cell wall formation. The waaY region is situated in the center of the waa operon and is involved in the assembly of the core region of the LPS molecule. The loss of this gene activity resulted in the loss of phosphoryl substituents [19, 48]. In this study, we investigated the mutation-related effect on the waaY function. A significant shift was observed in the function of this gene. Instead of the produced protein demonstrating kinase activity on the heptose molecule, the protein underwent a transition and illustrated transferase activity. This can be explained by the formation of transmembrane helices in the mutant protein, which were not detected in the wild-type protein, accounting for 14% of the secondary structure of the protein. Furthermore, both alpha and beta helices in the wild-type changed from 36% to 25% and from 18% to 29%, respectively. The function preservation of the gene was limited to W, W, C, W, C, W residues located at 11, 16, 36, 40, 71, 159, respectively, from the protein in the mutated protein, whereas it is resembled by K, Y, H, S, D, H, and N residues located at 60, 124, 192, 178, 160, 162, and 165 from the protein in the wild-type. The mutation susceptibility was found to be very low in the wild-type and was limited to the G, F, and H residues, located at positions 127, 178, and 198, respectively. Instead, this criterion increased in the mutated protein resembling W, W, C, W, C, C, and W, located at positions 11, 16, 36, 40, 71, 141, and 158, respectively, in the amino acid sequence. From our study, the waaY gene appears to be highly conserved due to its low susceptibility to genetic change, with the essential function of LPS phosphorylation as previously reported [49].

The cell walls in Gram-negative bacteria are mainly composed of LPS. This central component is encoded by specific genes, each of which has a distinct function that contributes to its formation. In E. coli, this set of genes is known as the waa gene family (formerly referred to as rfa); details have been published previously [50]. The waaL protein functions in the formation of O-antigen; waaFC and waaQ are required for the transfer of l, d-heptose in the inner core; waaP and waaY modify the inner core through phosphorylation [51]. In this study, site-directed mutagenesis was performed at multiple essential waa sites, which facilitated the prediction of changes that E. coli O157:H7 may undergo, potentially altering its infectivity, pathogenicity, and susceptibility to antibiotics. We found that despite multiple mutations in the waa operon, the bacterium still maintains the O-antigen core on the surface, suggesting that even with the waaL mutation, the cell possesses an alternative mechanism to include this protein. The interesting observation we made when determining the whole surface LPS of the mutated type E. coli O157:H7 is that there was a change in the secondary structure of the protein helices that form the transmembrane domain, resulting in a decrease of approximately 14% compared to the wild-type. We were unable to determine the function preservation and mutational hotspots in the mutated type, whereas in the wild-type, function preservation was moderate with a low tendency to mutation.

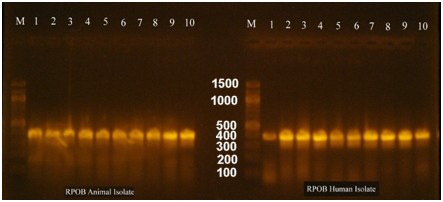

Moreover, the transmembrane topology in both types of bacteria was significantly changed. This is evident in the arrangement of the spanning proteins integrated into the cell wall, as illustrated in Fig. 9.

Fig. 9.

Fig. 9.

The arrangement of the transmembrane domain of mutant E. coli O157:H7 (A) and wild-type E. coli O157:H7 (B). The figure shows a significant change in the spanning proteins in the cell wall.

Significant changes were also predicted when applying the hidden Markov model (HMM) to both cell walls, as listed in Table 2.

| Criteria of predicted criteria | Mutant bacterium cell wall | Wild-type bacterium cell wall |

| WEBSEQUENCE length | 773 | 1453 |

| Number of predicted TMHs | 6 | 11 |

| Expected number of AAs in TMHs | 190.05804 | 215.48052 |

| Expected number, first 60 AAs | 22.2313 | 36.55825 |

| Total prob. of N-in | 0.04190 | 0.86538 |

HMM, Hidden Markov model; TMHs, Transmembrane helices; AAs, amino acids.

In both the studied and predicted cell walls, the distribution of both the

| Mutated cell wall (733 residues) | Wild-type cell wall (1453 residues) | ||||

| Location on the cell wall | Amino acid sequence | Type of the helix | Location of the amino acid residue | Amino acid sequence | Type of the helix |

| Outside | 1–19 | Inside | 1–19 | ||

| 20–42 | TM | 20–37 | TM | ||

| Inside | 43–144 | Outside | 38–40 | ||

| 145–162 | TM | 41–60 | TM | ||

| Outside | 163–166 | Inside | 61–71 | ||

| 167–186 | TM | 72–91 | TM | ||

| Inside | 187–290 | Outside | 92–105 | ||

| 291–310 | TM | 106–128 | TM | ||

| Outside | 311–319 | Inside | 129–134 | ||

| Inside | 320–436 | 135–157 | TM | ||

| 437–459 | TM | Outside | 158–166 | ||

| Outside | 460–733 | 167–189 | TM | ||

| Inside | 190–195 | ||||

| 196–213 | TM | ||||

| Outside | 214–239 | ||||

| 240–259 | TM | ||||

| Inside | 260–345 | ||||

| 346–368 | TM | ||||

| Outside | 369–371 | ||||

| 372–394 | TM | ||||

| Inside | 395–398 | ||||

| 399–418 | TM | ||||

| Outside | 419–1453 | ||||

Bacterial defense mechanisms against antimicrobial agents are of great interest.

Meanwhile, developing antibiotics represents the primary control strategy against

bacterial infection and stopping the spread of many epidemics that kill many

people. Thus, when a bacterial cell develops a resistance-mediated mechanism

against this medication, the consequence is a hazard to human health. Previous

studies [52, 53] have detailed resistance genes harbored by bacteria and

considered them a virulence factor in bacterial infection. In our research, we

noticed a significant change in the responses of mutant E. coli O157:H7

to certain families of antibiotics represented by

E. coli O157:H7 is responsible for many outbreaks and food poisoning reported in numerous countries. E. coli O157:H7 is characterized by its ability to resist antimicrobial agents and cause abdominal illness in both humans and animals. Most outbreaks originate from contaminated food and dairy products contaminated with E. coli O157:H7. The ability of E. coli O157:H7 to resist antimicrobial agents comes from cell wall modifications that prevent the entry of such substances into the cell. A thorough investigation to identify the site from which such resistance comes showed that waaK and waaL play key roles in developing cell wall-related antibiotic resistance. Meanwhile, site-directed mutagenesis at these sites produced a transferase enzyme that modifies the cell wall structure by altering the core OS structure, ultimately resulting in altered permeability and allowing the transfer of substances from the surrounding environment into the cell, including the antimicrobial agent.

All authors approved the publication of the article after reviewing the results, discussion, and the draft.

Data recorded, samples collected, questionnaires, and genomic DNA, and PCR products used during this study are available and stored at https://zenodo.org/uploads/14623186 with DOI: 10.5281/zenodo.14623186. The datasets used and analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

WAS performed sample collection, DNA extraction, PCR amplification, RNA performed data analysis, and article drafting, and IAA performed the research, supervised the progress of the project. All authors contributed to editorial changes in the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript. All authors have participated sufficiently in the work and agreed to be accountable for all aspects of the work.

The Biotechnology Research Center’s IRB at Al-Nahrain University issued ethical approval for animals welfare with reference no. PG/244, following EU Directive 2010/63/EU. The study was conducted in accordance with the principles outlined in the Declaration of Helsinki. The Biotechnology Research Center at Al-Nahrain University approved human sample collection after patients gave written consent—an ethical approval document with no. C.B 242 was issued for this purpose.

Not applicable.

This research received no external funding.

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Supplementary material associated with this article can be found, in the online version, at https://doi.org/10.31083/FBE38572.

References

Publisher’s Note: IMR Press stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.