1 Department of Internal Medicine, AdventHealth Hospital, Orlando, FL 32804, USA

2 Department of General Internal Medicine, University Hospital Galway, H91 YR71 Galway, Ireland

3 Gynecologic Oncology Program, AdventHealth Cancer Institute, Orlando, FL 32804, USA

Abstract

Biological therapies have transformed cancer treatment by targeting the molecular mechanisms involved in carcinogenesis. However, higher costs, limited accessibility, and supply chain disruptions—such as those caused by COVID-19 in recent years—underscore the need for cost-effective alternatives. Biosimilars, which are drugs that are highly similar to their reference biologics in terms of safety, efficacy, and quality, offer a viable solution (as these demonstrate clinically meaningful outcomes). This review article examines the role of biosimilars, mainly in gynecological cancers. The primary focus of this article is to compare the efficacy, safety, and cost-effectiveness of biosimilars, as well as to explore the barriers that restrict their widespread adoption. A comprehensive literature review was conducted, analyzing various studies, regulatory guidelines, and the latest data on biosimilars for the treatment of gynecological cancers. Pivotal trials, such as the GOG-0218, ICON7, and RUBY, were reviewed to assess the efficacy, safety, and cost-effectiveness of these biosimilars. This review highlights key oncologic therapies, including bevacizumab, trastuzumab, pembrolizumab, and their biosimilars, mainly for gynecological cancers. Additionally, this review considers the challenges of immunogenicity, interchangeability, and clinician awareness. After reviewing the latest peer-reviewed literature and related online materials, we found that biosimilars demonstrate comparable efficacy and safety to their reference biologics while also being more cost-effective. Recent clinical trials support the role of biosimilars in limiting the progression of disease and improving overall survival while reducing the financial burden of cancer treatments.

Keywords

- biosimilars

- cervical cancer

- endometrial cancer

- gynecologic cancers

- ovarian cancer

- targeted therapies

- monoclonal antibodies

- cost-effectiveness

The introduction of biological therapies in cancer treatment has significantly improved patient care, particularly in medical oncology. However, significant barriers remain, including high production costs of biologics, limited insurance coverage, and market supply challenges [1]. Nonetheless, the expiration of exclusivity for originator biologics has paved the way for biosimilars to attract the healthcare market, providing more cost-effective therapeutic alternatives [1, 2].

A biosimilar is a biological medicinal product that closely resembles an already authorized reference product, with minor differences that must be proven to be clinically insignificant [2, 3, 4]. Comparability exercises are required to ensure that biosimilars meet the same safety, efficacy, and quality standards as the original biologic. Indeed, biosimilar medications, rigorous though not identical to reference biologics, are highly similar and present a viable, cost-effective alternative as patent protections for leading biologics expire [2, 3]. Following the introduction of regulatory frameworks in Europe in 2003 and the subsequent approval of the first biosimilar in 2006, biosimilars have increasingly been incorporated into cancer treatment protocols [2]. Several countries, including the United States, Canada, and Japan, have adopted this model, signaling the growing global reliance on biosimilars to expand access to cancer therapies [1, 2, 3, 4].

As noted above, the introduction of biosimilars in oncology dates back over a decade, a process that was marked by approvals from the European Medicines Agency (EMA) for epoetin and filgrastim biosimilars in 2007 and 2008, respectively [2, 5]. In recent years, the focus has shifted from supportive therapies to monoclonal antibodies, which have the potential to prolong life. In 2017, the approval of rituximab biosimilars marked a pivotal moment in oncology, setting the stage for further approvals of monoclonal antibodies (mAbs), such as bevacizumab, in the treatment of metastatic gynecological cancers [4]. As the number of approved biosimilars continues to increase, the potential for these treatment products to reduce healthcare costs and expand patient access to life-saving treatments also rises. However, while the regulatory agencies are approving an increasing number of biosimilars for the treatment and supportive care of cancer, several challenges persist [5, 6]. These include issues related to cost, immunogenicity, a lack of widespread awareness, extrapolation of indications, and the complexities surrounding interchangeability with reference biologics. Therefore, in this review, we present key oncologic therapies, including bevacizumab, trastuzumab, pembrolizumab, and their biosimilars, mainly in ovarian, cervical, and endometrial cancers.

Biosimilars were first introduced in the European Union in 2006 and refer to biological medicines developed to replicate the effects of original biologics after the expiration of their patents [1, 2]. According to the United States Food and Drug Administration (FDA), a biosimilar is defined as a biological product that demonstrates high similarity to an FDA-approved reference product (RP), with no difference in terms of clinical safety, purity, or potency, despite minor variations in clinically inactive components (Table 1, Ref. [3, 5, 6, 7]). This rigorous standard ensures that biosimilars maintain the same therapeutic efficacy as their reference products [4].

| Regulatory agency | Definition | Reference |

| WHO | A biosimilar is a SBP, defined as “a biotherapeutic product, which is similar in terms of quality, safety and efficacy to an already licensed reference biotherapeutic product”. | [6] |

| US FDA | A biosimilar is a biological product that is highly similar to a US-licensed RP, notwithstanding minor differences in clinically inactive components, and for which there are no clinically meaningful differences between the biological product and the RP in terms of the safety, purity and potency of the product. | [3] |

| EMA | [5] | |

| Jp-PMDA | [7] | |

Abbreviations: WHO, World Health Organization; SBP, similar biotherapeutic product; US FDA, United States Food and Drug Administration; RP, reference product; EMA, European Medicines Agency; Jp-PMDA, The Japanese Pharmaceuticals and Medical Devices Agency; FOBNP, follow-on biological medicinal product; RBP, reference biological product.

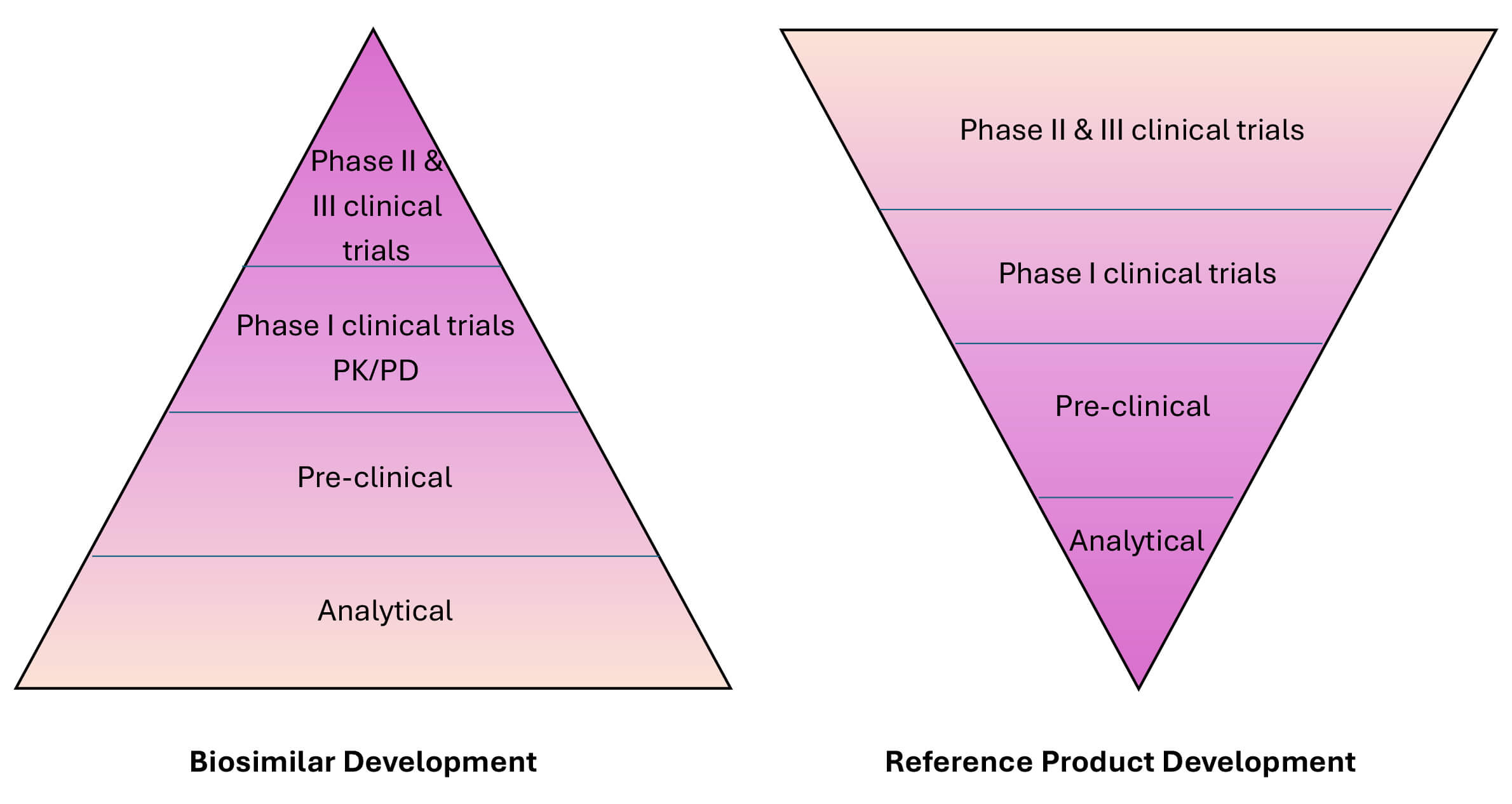

However, it is crucial to note that biosimilars differ from generic drugs. While generic drugs are identical chemically to their reference drugs, biosimilars and their reference biologics have complex structures and may vary in certain inactive components (Fig. 1). Nonetheless, these differences do not result in any significant clinical impact because biosimilars share the same mechanism of action as the original biologics; moreover, the biosimilars are approved for the same indications (although regulatory guidelines may allow for extrapolation across various indications) [5, 6].

Fig. 1.

Fig. 1.

Comparison of the development of originator biologics and biosimilars and their respective regulatory pathways. Safety and efficacy (phase II and phase III clinical trials) assessments are the pillars of developing a new biological product. In contrast, biosimilar development focuses on the establishment of a match between the biosimilar and the reference product. Abbreviations: PK, pharmacokinetics; PD, pharmacodynamics.

In terms of administration, biosimilars follow similar dosage, route, and/or strength as their reference products. A particularly intricate aspect of biologics, such as for bevacizumab, is their dependence on post-translational modifications and the selective degradation of regulatory subunits. This complexity is one reason why creating an exact copy of a biologic, akin to a generic, is not feasible. Instead, biosimilars are developed as close approximations of the original biologics, designed to offer the same clinical benefits without compromising quality or safety [7, 8] (Table 2).

| Properties | Generic drug | Biosimilar |

| Size | Small | Relatively longer |

| Molecular weight | Low molecular weight ( |

High molecular weight (4000 to |

| Molecular composition | Complex, difficult to characterize similarly to the biological reference product | |

| Comparison with reference product | Identical active ingredient | |

| Manufacturing | Chemically | Using living cellular systems |

| Stability | Stable | Sensitive to handling and storage |

| Immunogenicity | Low | |

| FDA approval requirements | ||

Abbreviations: RP, reference product; FDA, Food and Drug Administration; PK, pharmacokinetics.

A comprehensive, stepwise approach is employed to establish biosimilarity, encompassing analytical, non-clinical, and clinical studies. This rigorous process begins with a detailed characterization of the physicochemical properties and biological functions of the biosimilar, followed by non-clinical toxicity evaluations and comparisons with final clinical relevance (Fig. 1) [9, 10, 11]. Key analytical studies compare biosimilars to the reference product at various levels, including the primary amino acid sequence, higher-order protein structures, post-translational modifications, and biological activities. These structural analyses confirm that both products share the same primary protein sequence [12]. Functional assessments are also crucial, particularly for monoclonal antibodies, such as bevacizumab, where tests are performed to evaluate antigen-binding capabilities (Fab functions) and immune system interactions (Fc functions), such as antibody-dependent cellular cytotoxicity [13]. Pharmacokinetic (PK) studies are critical for demonstrating that the biosimilar behaves similarly in the body to the reference product (Fig. 2). Once PK similarity is confirmed, at least one comparative clinical study is generally required to evaluate the efficacy, safety, and immunogenicity of the biosimilar in comparison to the originator product (Table 2).

Fig. 2.

Fig. 2.

Biosimilar PK/PD model. Biosimilars, by definition, have structural differences with the respective originator products. The approval application of a biosimilar must present analytical characterization, pharmacokinetic, and pharmacodynamic profiles, as well as comparative clinical studies to demonstrate high similarity between the two products. Abbreviations: PK, pharmacokinetics; PD, pharmacodynamics.

Biosimilars are generally approved through an abbreviated regulatory pathway, established under the Biologics Price Competition and Innovation Act (BPCI Act) of 2009. This framework, part of the Obama Care or Affordable Care Act (ACA) of 2008, allows for a faster approval process while maintaining rigorous standards for the desired quality and safety. After completing the clinical trials, the manufacturer(s) must submit a Biologics License Application (BLA) to the FDA, which includes trial results, manufacturing details, and proposed labeling. The FDA approves a biosimilar for market use only if the benefits outweigh the risks and the manufacturer can ensure consistent product quality (Figs. 1,2). Notably, this application process is rather more complex than the one for generic drugs, reflecting the intricate nature of biological products [14].

In the clinical development of biosimilars, only a limited number of potential products undergo studies in patients with cancer during the initial phases of development. Thus, physicians involved in treatment need to familiarize themselves with the regulatory principles that support the approval of biosimilars, particularly the concept of extrapolating indications [8, 15]. Extrapolation is a key principle in the approval process for biosimilars, aimed at reducing the need for redundant clinical trials, which are time- and resource-intensive.

Many regulatory agencies (e.g., EMA) permit the extrapolation of clinical data from an RP to a biosimilar for indications that were not directly tested during the initial comparison [15, 16]. If the biosimilarity has been rigorously established through analytical, clinical, and/or non-clinical evaluations, regulatory agencies may permit the extrapolation of efficacy and safety data from one cancer indication to another. Hence, this allows biosimilars to be approved for multiple cancer indications without requiring additional new clinical trials for each specific condition. However, while extrapolation is a common practice in both the FDA and EMA approval processes, extrapolation is not automatically granted for other conditions and is subject to stringent scientific justification [12]. This process is crucial to the faster development and approval of biosimilars, as it accelerates patient access to more affordable treatments. Despite these benefits, surveys indicate that only about 12% of physicians are fully comfortable with the concept of extrapolation, pointing to a significant need for further education among healthcare professionals, particularly gynecologic oncologists, on the scientific and regulatory rationale behind extrapolation [17, 18].

As cancer incidence rises globally, driven by aging populations and inflation, improved access to care in high-income countries and expanding healthcare in lower-income regions, the financial strain on healthcare systems has grown considerably. Advances in cancer diagnosis and management have prolonged survival rates, further increasing treatment durations and associated costs.

In the United States, cancer drug spending has surged, reaching USD 193 billion in 2022, according to the Intercontinental Medical Statistics (IMS) Health. Meanwhile, the IQVIA (formerly Quintiles and IMS Health, Inc.) forecasts that oncology drug spending will increase by 95%, reaching an estimated USD 377 billion by 2027 [18]. A significant portion of this increase is attributed to monoclonal antibodies, which account for approximately 35% of the total global oncology drug spending, owing to the introduction of expensive and novel therapies. Thus, despite monoclonal antibodies forming only 15% of the drugs listed in the NCCN (National Comprehensive Cancer Network) guidelines, they dominate the U.S. cancer therapy expenditures. For example, bevacizumab and trastuzumab are among the top 20 most expensive cancer drugs used in outpatient settings. Indeed, by February 2022, the U.S. sales of bevacizumab alone totaled USD 2.6 billion, with biosimilars accounting for USD 1.6 billion (61.5%) of these sales. Therefore, the expanded use of biosimilars, such as bevacizumab, has the potential to significantly reduce the overall cost of cancer treatment. This, in turn, could lower insurance premiums and out-of-pocket expenses for patients, offering a more sustainable model for managing the growing financial burden of cancer care, including gynecologic malignancies.

The advancements made in clarifying the molecular mechanisms and pathways involved in carcinogenesis have promoted the development of targeted therapies. These therapies are designed to act on specific molecules that drive tumor growth and proliferation, thereby blocking downstream signaling pathways and inhibiting tumor development. However, the production of these innovative treatments is rather expensive, accounting for a significant portion of the total oncological spending in the United States and limiting patient access due to affordability concerns. As patents for biological therapies approach expiration, many pharmaceutical companies have the opportunity to develop more affordable biosimilars, which have the potential to increase patient access to effective treatments and, ultimately, reduce healthcare costs.

In 1971, Dr. Judah Folkman [19] was the first scientist to emphasize the critical role of angiogenesis as an essential step in the growth and metastasis of solid tumors. This discovery established angiogenesis as a promising therapeutic target for various types of cancer [20]. Subsequently, in 1989, the isolation of VEGF-A marked a breakthrough in understanding angiogenic mechanisms [21]. Meanwhile, subsequent research efforts have identified VEGF proteins and their receptors (VEGFRs) as crucial regulators of both normal and pathological tumor angiogenesis through the activation of various downstream pathways [22]. The VEGF protein binds to the corresponding VEGFR on endothelial cells. This leads to VEGFR dimerization, activation of the tyrosine kinase, and various downstream signaling pathways, such as the rapidly accelerated fibrosarcoma (RAF), the retinal activating system (RAS), and phosphoinositide 3-kinase (PI3K), ultimately promoting angiogenesis. Elevated VEGF levels have also been associated with metastasis and poorer clinical outcomes [23]. In addition to the role of the VEGF/VEGFR pathway in promoting metastasis, this pathway may also contribute to a direct tumor-promoting mechanism. Thus, inhibiting VEGF could potentially promote direct cytotoxic effects in cancer therapeutics [24].

Angiogenesis is a key process in tumorigenesis; thus, the VEGF/VEGFR pathway represents a crucial target in many solid tumors. A monoclonal neutralizing antibody has been demonstrated to potentially inhibit tumor proliferation in vivo, leading to the development of bevacizumab (Avastin®), a humanized recombinant monoclonal immunoglobulin G1 (IgG1) anti-VEGF-A antibody [23]. This biosimilar was engineered by incorporating the VEGF-binding residues of murine neutralizing antibody into the setting of a standard human IgG molecule [25, 26]. Bevacizumab specifically binds to soluble VEGF-A via the Fab region, thereby preventing VEGF from interacting with its receptors (i.e., VEGFR-1 and VEGFR-2) on the endothelial cell surface. This interruption in VEGF–VEGFR signaling inhibits tumor growth by causing the regression of cancer vasculature and suppressing the formation of new blood vessels [27]. Additionally, by normalizing the vasculature of the tumor microenvironment (TME), bevacizumab enhances the effectiveness of cytotoxic chemotherapies, which are frequently used in combination for solid tumors, including breast and ovarian cancers [27, 28].

The human epidermal growth factor receptor (HER) receptors are monomers on the

cell surface, and after the ligand binds to their extracellular domains, the HER

proteins dimerize and transphosphorylate through intracellular regions. HER2 in

an open conformation forms the preferred dimerization partner through HER family

members [29, 30]. Two key downstream signaling pathways that are activated by HER

receptors are the PI3Kprotein kinase B (AKT) axis and the phosphatase and tensin

homolog (PTEN) pathway, which involve other critical influencers, such as nuclear

factor kappa-light-chain-enhancer of activated B cells (NF-

The overexpression of the HER2 protein is observed in approximately 25–30% of patients with breast/ovarian cancers and is associated with the more aggressive biological behavior of these cancers [34, 35]. Moreover, HER2 overexpression and amplification have been identified in subsets of endometrial cancers and are linked to poorer outcomes. Initial conflicting data regarding the prognostic value of HER2 have since been resolved, with overwhelming evidence supporting the significance of this genetic and biological finding [36, 37].

Berchuck et al. [33] first demonstrated the association between HER2 overexpression and lower survival in patients with advanced-stage ovarian cancer. In patients with epithelial ovarian cancer (n = 73), those with overexpressed HER2 had significantly poorer survival in comparison to cases with normal HER2 expression [33]. Additionally, high HER2 expression tumors were less likely to respond to primary therapy adequately or had negative second-look laparotomy when normal serum cancer antigen (CA)-125 levels were reported preoperatively.

The reported rates of HER2 overexpression in serous endometrial carcinomas range between 14% and 80%, and HER2 amplification ranges from 21% to 47%. Specifically, for endometrioid carcinomas, histology, HER2 overexpression, and amplification have been reported in 1% to 47% and 0% to 38% of cases, respectively [36, 37]. Both HER2 overexpression and amplification are associated with poor prognosis in endometrial carcinoma.

Trastuzumab (Herceptin), a mAb, targets the extracellular domain of the HER2 receptor, specifically domain IV. The mechanisms of action for trastuzumab include: (i) inhibition of HER2 shedding, (ii) inhibition of the PI3K–AKT pathway, (iii) attenuation of cell signaling, (iv) antibody-dependent cellular cytotoxicity, and inhibition of tumor angiogenesis [38]. The trastuzumab half-life after i.v. and s.c. administration is approximately 10 days. Indeed, s.c. administration of a trastuzumab dose of 600 mg generally achieves effective drug levels comparable to those achieved through i.v. administration [39].

Programmed cell death protein 1 (PD-1) is important in modulating immune responses and T-cell activity, thereby promoting self-tolerance. Moreover, PD-1 induces apoptosis of antigen-specific T cells while inhibiting apoptosis of T-regulatory cells. The PD-1/programmed cell death protein ligand 1 (PD-L1) pathway is essential in the induction and maintenance of immune tolerance within the TME. The interactions between PD-1 and PD-L1 (or PD-L2) regulate T-cell activation, proliferation, and cytotoxic secretion, ultimately dampening the anti-tumor immune response [40].

Pembrolizumab (Keytruda®) is a humanized mIgG4 kappa Ab that is directed against cell surface PD-1 on lymphocytes. The PD-1 receptor functions as an immune checkpoint, preventing the immune system from attacking itself [41]. Higher PD-L1 expression is observed in certain gynecological tumors. Some tumor types utilize adaptive immune resistance, in which these tumors exploit the natural physiology of PD-L1 induction and adapt towards anti-tumor responses. The inhibition of T cell function occurs during the PD-L1 and PD-1 interactions, thereby blocking the formation of the PD-1–PD-L1 complex, which results in improved T cell-mediated killing [42, 43].

Dostarlimab (Jemperli, also referred to as TSR-042) is a mAb for the humanized IgG4 isotype, produced in mammalian Chinese hamster ovary cells using recombinant DNA technology. Dostarlimab binds to PD-1 on T cells, blocking interactions with its ligands PD-L1 and PD-L2, thereby activating the immune response [44]. Dostarlimab binds to the PD-1 receptor with a high affinity (binding affinity (KD) of 300 pM). Meanwhile, similar binding profiles have been observed in preclinical assessments of previous treatments, such as nivolumab (OPDIVO®), pembrolizumab, and cemiplimab (LIBTAYO®).

HER2+ has been observed in cervical cancer in approximately 2%–6% of cases [45, 46, 47]. Trastuzumab–deruxtecan (T–DXd), an ADC, combines the humanized anti-HER2 mAb trastuzumab with the topoisomerase inhibitor deruxtecan [48]. A tumor-agnostic study demonstrated a durable clinical response of trastuzumab–deruxtecan in various HER2-expressing immunohistochemistry (IHC) 3+ or 2+ advanced solid tumors of patients who progressed on prior therapy or had no desirable/optimal treatment options.

An open-label, multicenter, phase II trial (DESTINY-PanTumor02) evaluated T–DXd

in 267 patients with HER2-expressing (IHC 3+ or 2+) locally advanced or

metastatic disease, following

For an advanced/metastatic/recurrent cervical carcinoma, the NCCN guidelines recommend HER2 IHC testing (with reflex to HER2 fluorescence in situ hybridization (FISH) for equivocal IHC). The biosimilar (viz., Fam–trastuzumab–deruxtecan–nxki) is also included as a category 2A option in the NCCN guidelines, indicating that this biosimilar is useful under certain circumstances as a second-line or subsequent therapy for HER2+ tumors (IHC 3+ or 2+).

In combination with chemotherapy and bevacizumab, the FDA approved the use of

pembrolizumab for patients with persistent, recurrent, or metastatic cervical

cancer tumors expressing PD-L1 (combined positive score (CPS)

Current guidelines recommend two immunotherapy-based regimens as the preferred

first-line therapy options for PD-L1-positive cases. Based on the Keynote-826

study [50], chemotherapy alongside pembrolizumab

Based on data generated in the GOG-218 and ICON7 clinical trials, bevacizumab-containing regimens have been suggested as a viable option for first-line chemotherapy following cytoreductive surgery [51, 52, 53]. These recommended regimens involve upfront combination (i.e., carboplatin/paclitaxel/bevacizumab) followed by bevacizumab maintenance. In the GOG-218 clinical trial, patients receiving upfront carboplatin/paclitaxel/bevacizumab without subsequent bevacizumab maintenance (as a single agent) did not demonstrate any improved outcomes compared to the control group (carboplatin/paclitaxel alone). There is currently no data supporting the introduction of bevacizumab (as maintenance therapy).

Based on the above-noted findings from the GOG-218 and ICON7 clinical trials, bevacizumab monotherapy is recommended as a maintenance option for patients with stage II–IV diseases who achieve a complete or partial response following primary treatment with surgery [51, 52, 53].

Although chemotherapy has been widely studied for endometrial cancer, multiagent regimens are included as first-line therapy options (viz., carboplatin/paclitaxel, carboplatin/docetaxel, or carboplatin/paclitaxel/bevacizumab) in the setting of recurrent disease [54, 55]. Carboplatin/paclitaxel is more commonly used for patients with advanced/metastatic/recurrent endometrial cancers, showing response rates of approximately 40%–62% and an OS of about 13–29 months [56, 57]. The phase III GOG-209 trial compared carboplatin/paclitaxel with a regimen of cisplatin/doxorubicin/paclitaxel/filgrastim and demonstrated similar oncologic outcomes between the two regimens; however, the toxicity and tolerability profiles favored carboplatin/paclitaxel [58]. Consequently, carboplatin/paclitaxel became the preferred first-line option; the NCCN guidelines also recommend this treatment.

A phase II trial evaluated bevacizumab

Carboplatin/paclitaxel is the preferred systemic therapy (as recommended by the NCCN guidelines) in the primary/adjuvant setting for patients with high-risk histologies or advanced-stage disease [62, 63]. Based on the data presented in the landmark phase III NRG-GY018 and RUBY trials, the NCCN guidelines have recently added the pembrolizumab/carboplatin/paclitaxel and the dostarlimab/carboplatin/paclitaxel triplet regimens as Category 1 preferred primary therapy options for advanced-stage disease [64, 65]. At 24 months, the PFS was 36.1% in the dostarlimab-based arm compared to 18.1% in the chemotherapy-alone arm, and OS was 71.3% versus 56.0% in the respective arms. More significant benefits were observed in the tumors of deficient mismatch repair (dMMR)/microsatellite instability-high (MSI-H) patients, with a PFS of 61.4% compared to 15.7% in the triplet therapy arm versus the doublet therapy arm [64].

Bevacizumab–awwb (ABP215 or Mvasi; Amgen, Inc.) became the first FDA-approved biosimilar in 2017 [66]. Multiple functional and structural studies using endothelial cell proliferation assays and an enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) have demonstrated that ABP215 is highly similar to bevacizumab in terms of VEGFA binding [66]. In vitro studies using human umbilical vein endothelial cells (HUVEC) cells assessed the functional similarity of ABP 215 in comparison to bevacizumab. These results showed that similar inhibition of proliferation was noted between the biosimilar and originator components that bind to the neonatal Fc receptor (EVEGF) [67, 68, 69]. Subsequently, numerous other bevacizumab biosimilars became approved for the treatment of gynecological and non-gynecological cancers; the principle of extrapolation is widely used in this context. Table 3 (Ref. [67, 70, 71, 72, 73, 74, 75, 76, 77, 78, 79, 80, 81, 82, 83, 84, 85, 86, 87, 88]) summarizes key pharmacological and clinical studies, along with their oncological outcomes, involving selected bevacizumab biosimilars.

| Biosimilar | Manufacturer | Study design | Population | Primary endpoint | Outcomes |

| ABP | Amgen | Randomized single-dose study to assess PK of ABP215, US- and EU-bevacizumab [67] | Healthy adult male volunteers, aged 18–45 years | AUCinf | |

| Cmax | |||||

| Randomized, double-anonymized study to compare safety and efficacy of ABP215 and bevacizumab [70] | Previously untreated adults with stage IV or metastatic NSCLC (n = 642) | ORR and RR | |||

| PF-06439535 | Pfizer | Non-clinical assessment, structural and functional assays, cell growth assay, in vivo studies in monkey [71, 72] | Not applicable | Structure, function, PK | |

| Multinational double-blinded, randomized parallel-group phase III clinical trial [73] | Previously untreated adults with stage IIIb, IV or recurrent metastatic non-squamous NSCLC (n = 719) | ORR at week 19 confirmed at week 25 | |||

| CT-P16 | CellTrion Healthcare | Randomized, double-anonymized parallel-group phase I trial [74] | Healthy adult males | AUCinf | |

| Cmax | |||||

| Double-bind, randomized, active-controlled, parallel-group, phase III clinical trial [75] | Patients with stage IV or recurrent NSCLC | ORR | |||

| SB8 | Samsung Bioepis Co. | Randomized, open-label, single- dose study [76] | Healthy male volunteers, aged 18–55 years | AUCinf | Similar AUCinf, AUClast, and Cmax across SB8, US- and EU-bevacizumab |

| AUClast | |||||

| Cmax | |||||

| Double-blinded, randomized phase III study [77] | Previously untreated adults with metastatic or recurrent non-squamous NSCLC (n = 384) | Best ORR by week 24 | |||

| FKB238 | Centus Biotherapeutics | Randomized, open-label, single-dose study [78] | Healthy male volunteers | AUCinf | AUCinf and AUClast are similar across FKB238, US- and EU-bevacizumab |

| AUClast | |||||

| Randomized, double-anonymized study to compare safety and efficacy of FKB238 and bevacizumab [79] | Previously untreated adults with recurrent or stage IV non-squamous NSCLC (n = 731) | ORR | |||

| MYL-1402O | Biocon Biologis and Vitaris | Randomized, open-label, single-dose study [80] | Healthy male volunteers | AUCinf | AUCinf was similar across MYL-1402O, US- and EU- bevacizumab |

| Double-anonymized, randomized, phase III study [81] | Previously untreated adults with stage IV non-squamous NSCLC (n = 671) | ORR at 18-weeks | |||

| MB02/BEV92 | Randomized, open-label comparative trial until progression or important toxicity [82] | Previously untreated adults with mCRC | AUC0-336 | AUC0-336 and AUCs (cycle 7) were similar for both arms | |

| AUCss (Cycle 7) | |||||

| Multinational randomized, double-blind, phase III study (STELLA) [83] | Patients with stage IV non-squamous NSCLC (n = 627) | ORR at week 18 | |||

| BI 695502 | Boehringer Ingelheim | Randomized, single-blind, single-dose study [84] | Heathy male volunteers (n = 91) | AUC0-inf at 99 days | Similar PK and safety profiles |

| Phase III, multicenter, randomized, double-blind trial [85] | Adult patients with recurrent or metastatic NSCLC (n = 671) | ORR at 18-weeks | |||

| BCD-021 | Biocad | PK sub-study of randomized, double-blinded study [86] | Adult patients with advanced NSCLC | AUCtau (504 h) | Similar PK and safety profile |

| International multicenter phase III clinical trial [87] | Patients with no previous treatment for advanced NSCLC (n = 357) | ORR | |||

| BAT1706 | Bio-Thera Solutions | Randomized, double-blind, phase III study [88] | Previously untreated adults with recurrent or stage IV NSCLC (n = 649) | ORR at week 18 | |

Abbreviations: ABP, albumin-bound paclitaxel; AUC, area under the curve; AUCinf, area under plasma concentration–time curve (from time zero to infinite time); AUClast, area under the curve (from time of administration up to the time of the last quantifiable concentration); AUCtau, area under the concentration–time-curve (in one dosing interval); Cmax, maximum observed concentration; EU, European Union; ORR, objective response rate; RR, relative response; PK, pharmacokinetics; CI, confidence interval; NSCLS, non-small cell lung cancer; ADA, anti-drug antibody; mCRC, metastatic colorectal cancer; PFS, progression-free survival; AE, adverse events.

The original product of Merck Sharp & Dohme, Keytruda® (pembrolizumab), received approval from the FDA on September 4, 2014, and from the EMA on July 17, 2015 [89]. Keytruda achieved global sales of USD 14.4 billion in 2020, making it an attractive target for biosimilar developers. The Keytruda patents are set to expire in the U.S. in November 2036 and in Europe by June 13, 2028 [89]. Hence, there could be a genuine use for pembrolizumab biosimilars for oncological indications soon. Several biosimilars of pembrolizumab and non-originator biologicals, which are either approved or currently under translational or clinical development, are listed in Table 4.

| Company name | Country | Stage of development |

| BioXpress Therapeutics | Switzerland | In pipeline |

| DM Bio | South Korea | In pipeline |

| Formycon | - | In pipeline |

| NeuClone/Serum Institute of India | India, Australia | Preclinical (NeuClone and Serum Institute of India have agreed to co-develop 10 biosimilar monoclonal antibodies) |

| PlantForm/PlantPraxis Biotecnologia/Bio-Manguinhos/Fiocruz (ANVISA, Brazilian Health Regulatory Agency) | Canada/Brazil | In pipeline |

Several trastuzumab biosimilars and biosimilar candidates, including CT-P6 (Herzuma), SB3 (Ontruzant), PF-05280114 (Trazimera), ABP 980 (Kanjinti), MYL-1401O, BCD-022 (HERtiCAD), HD201, EG12014, HX102, and TX05, have undergone phase III trials. As shown in Table 5, five of these biosimilars are currently EMA- and/or FDA-approved for early and metastatic breast cancers [90, 91, 92, 93, 94]. Data remain limited and generally lacking regarding the use of trastuzumab biosimilars in uterine and/or ovarian cancers. Further research and trials are highly desirable to address the unmet need for immunotherapeutic biosimilars in the field of gynecological oncology.

| Biosimilar name | Biosimilar code | Date of approval | Manufacturer (Location) |

| Ogivri (trastuzumab–dkst) | MYL-1401O | December 2017 | Mylan GmbH, Steinhausen, Switzerland |

| Kanjinti (trastuzumab–anns) | ABP 980 | June 2018 | Amgen Inc., Thousand Oaks, CA, USA |

| Herzuma (trastuzumab–pkrb) | CT-P6 | December 2018 | Celltrion Inc., Incheon, Korea |

| Ontruzant (trastuzumab–dttb) | SB3 | January 2019 | Samsung Bioepis Co., Ltd., Incheon, Korea |

| Trazimera (trastuzumab–pkrb) | PF-05280014 | March 2019 | Pfizer Ireland Pharmaceuticals, Ringaskiddy, Ireland |

For the treatment of primary advanced/recurrent endometrial cancer (dMMR or MSI-H), dostarlimab–gxly (Jemperli, GlaxoSmithKline) was FDA approved on July 31, 2023, for use in combination with carboplatin/paclitaxel, followed by single-agent dostarlimab–gxly. The efficacy was evaluated in the RUBY trial [64] (NCT03981796), where the efficacy analysis focused on a prespecified subgroup of patients (n = 122) with dMMR/MSI-H [64]. In this trial, patients were randomized (1:1) to receive either dostarlimab–gxly in combination with carboplatin/paclitaxel, followed by dostarlimab–gxly, or a placebo combined with carboplatin/paclitaxel, followed by a placebo. A statistically significant improvement in PFS was observed in the dMMR/MSI-H population, with a median PFS of 30.3 months in the dostarlimab–gxly group compared to 7.7 months in the placebo group [45]. Based on these encouraging observations, additional biosimilars are likely to be developed and approved for oncological therapeutic indications in the near future, while obstacles and challenges remain for their acceptance [95].

Biosimilars are the successor to reference biologics for which the patent has expired or is expiring. Biosimilars match their reference biologics in terms of safety, efficacy, and quality, thereby demonstrating clinically meaningful/similar outcomes. Over the past decade, there has been an exponential growth in targeted therapeutic development and regulatory approval of biosimilars for oncological indications. Likewise, the introduction of biosimilars as novel therapeutic agents for gynecological cancers is expected to enhance patient access to costly therapies, mitigate drug shortages, and reduce healthcare expenditure, making them an attractive treatment option. In addition to the FDA-approved biosimilars, several other potential agents for targeted therapies are in advanced stages of development. Approval of biosimilars by regulatory authorities is expected to involve extrapolation from studies on different types of tumors in patients, both in vivo and in vitro, as well as clinical studies that have shown equivalent pharmacokinetics, safety, efficacy, and immunogenicity between the originator and the biosimilar. The acquaintance of oncologists with the principle of extrapolation and their understanding of the scientific and regulatory aspects of biosimilars is critical to the progression of biosimilars as a treatment option, as only a wider use of biosimilars will prompt the adoption of these agents in clinical routine for managing patients with gynecological malignancies.

MG—Conception, literature review, data acquisition, interpretation, writing manuscript first draft, illustration, table execution. AH––Literature review, data acquisition, interpretation, writing manuscript first draft, illustration, table execution. SA––Literature review, data interpretation, writing & editing manuscript draft, execution, supervision, resources. All authors read and approved the final manuscript. All authors have participated sufficiently in the work and agreed to be accountable for all aspects of the work.

Not applicable.

Not applicable.

This research received no external funding.

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

Publisher’s Note: IMR Press stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.