1 Department of Bioengineering, University of Texas at Arlington, Arlington, TX 76010, USA

Abstract

Healthcare-associated infections (HAIs) are a source of constant risk for inpatients and healthcare workers and a serious challenge to human health services worldwide. Common surfaces, such as doorknobs, tables, and bedrails, can become contaminated and develop into a reservoir of pathogens; thus, common surfaces can play an important role in the fomite-mediated pathway through which HAIs are transmitted. Non-critical disinfection techniques are common practice in the nosocomial setting, aiming to reduce the bioburden of common surfaces and prevent the spread of HAIs. However, these techniques are limited by factors such as the need for frequent disinfectant reapplication and the potential recontamination that can occur at any moment after cleaning. Light-activated antimicrobial nanocoatings are an interesting alternative to overcome these issues, since these nanocoatings can confer self-disinfection capacities to nosocomial common surfaces, to supplement non-critical disinfection. Thus, this review aims to discuss the relevance of fomites and gaps in common disinfection strategies that favor the propagation of HAIs. In addition, nanotechnology-based antimicrobial coatings are considered, along with strategies for nanoparticle-based antimicrobial coating development. Furthermore, the use of titanium oxide nanoparticles to formulate photo-responsive antimicrobial nanocomposites/nanocoatings and concerns related to toxicity, environmental fate, and bacterial resistance development are discussed. Finally, emerging photo-responsive antimicrobial nanotechnologies and future perspectives are considered.

Keywords

- antimicrobial

- anti-infective agents

- disinfection

- fomites

- health services

- nanotechnology

- nanocomposites

- nanoparticles

- titanium dioxide

The focus of this article is on photo-responsive antimicrobial nanocoatings, a category of composite nanomaterials used to coat and confer self-disinfecting properties to inanimate surfaces to disrupt the transmission of infectious diseases. Infections occur when pathogens break through the immune defenses to invade a susceptible individual. Then the direct or indirect spread of infection to other hosts, known as contagion or infection transmission, may happen in different environments and by a variety of routes. Fortunately, for most of these diseases, the immune system fights and clears the infection within a few days. However, in environments such as the nosocomial setting, pathogens may be more virulent and can cause significant infections or even death. This article will review hospital-associated infections, the fomite route of contagion, and common non-critical disinfection strategies. Then the role of nanotechnology on the development of antimicrobial coatings will be discussed, followed by a description of commonly used strategies for antimicrobial coating development, the use of nanoparticles as antimicrobial agents with a focus on titanium oxide nanoparticles, and the formulation of photo-responsive antimicrobial nanocomposites. In the final sections, concerns related to toxicity, environmental fate, and bacterial resistance development will be discussed, followed by brief sections on emerging photo-responsive antimicrobial nanotechnologies and future perspectives. As an important note, all along the text, the terms antimicrobial coatings and antimicrobial nanocoatings are used indistinctly.

One environment that is prone to harbor dangerous pathogens is the nosocomial setting. In there, an increased number of patients are subject to modern therapies, such as organ transplantation or chemotherapy, which can temporarily weaken their immune systems. Other patients may present limited immune responses due to their advanced age or by the effect of debilitating diseases. All these factors contribute to the patient’s increased risk of acquiring opportunistic infections during their stay at the healthcare facility, also known as nosocomial or healthcare-associated infections (HAIs) [1, 2]. These infections are particularly challenging to patients and health services worldwide because of their potential long-term effects and increased risk of death [3]. In the United States for instance, HAIs have a reported incidence of 5–8%, which duplicates the likelihood of death for affected patients. Concerningly, in some developing nations the incidence of HAIs reaches a staggering 50%, adding a potential life threat to common hospitalization procedures [4, 5]. Moreover, these nosocomial infections involve microorganisms like E. faecium, S. aureus, K. pneumoniae, A. baumannii, P. aeruginosa, and Enterobacter species, aptly dubbed the ESKAPE pathogens [4, 6]. Additionally, other bacterial agents such as spore-forming C. difficile, viruses like rhinovirus, respiratory syncytial virus, parainfluenza, and coronavirus, or fungal species as Candida spp. and Aspergillus spp. may be a source of HAIs [7, 8]. Besides their virulence and pathogenicity, these microorganisms possess an innate resistance that extends their viability onto surfaces over extended periods [9, 10]. For example, recent studies confirmed that human pathogenic bacteria can survive for months on dry surfaces [11, 12]. Similarly, other studies demonstrated that the severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) from saliva droplets was able to survive up to seven days on contaminated surfaces [13, 14]. Hence, besides infection by direct exposure, another important route of HAI contagion is by indirect contact with contaminated surfaces or fomites [15].

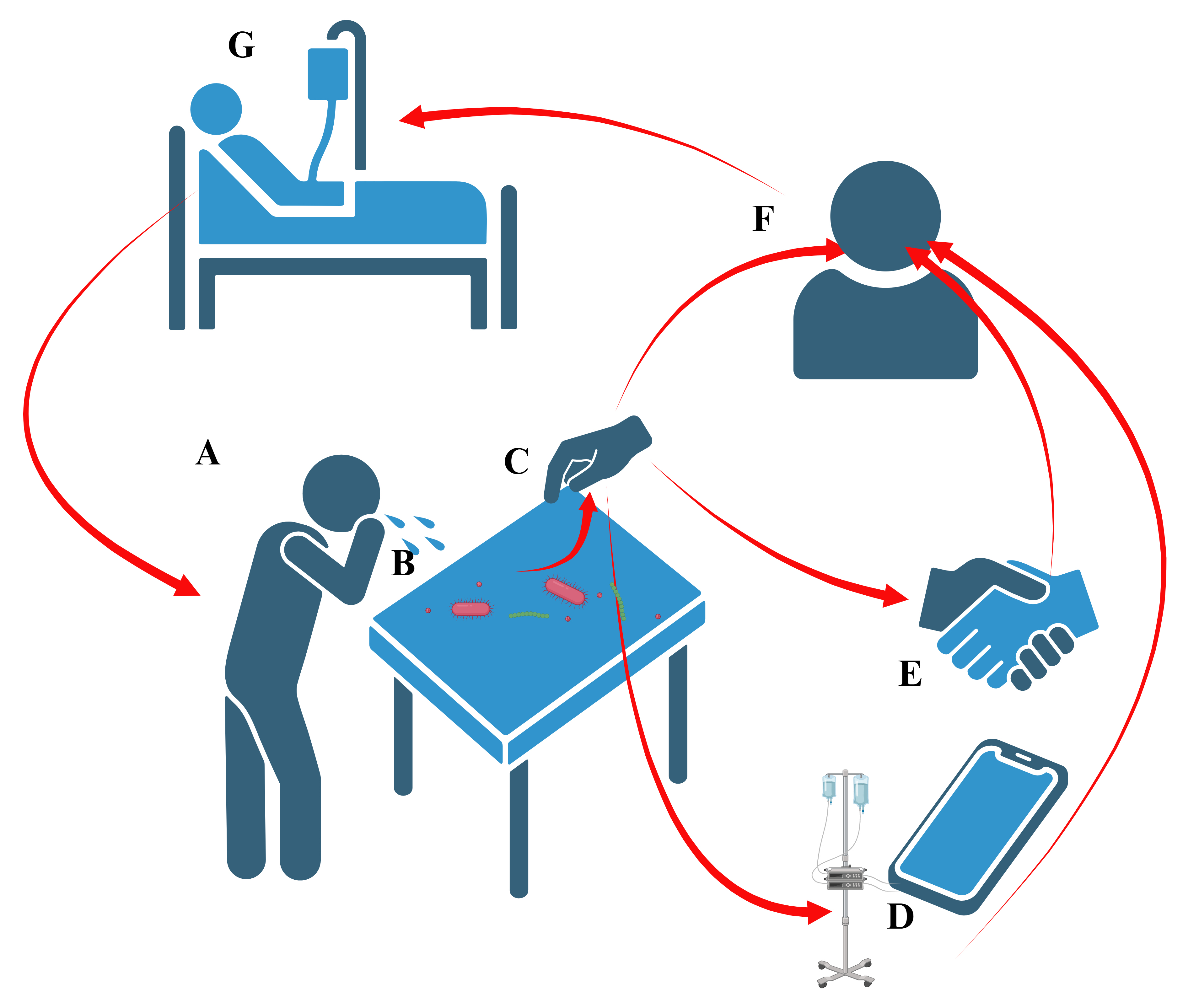

Fomites are defined as inanimate objects that can work as a vector and reservoir to transfer infective agents [15, 16]. Research shows that many infections of bacterial, fungal, or viral origin can be indirectly transmitted via fomites (Fig. 1). Their role as passive sources of HAI propagation has been recognized as an important health problem and their involvement in nosocomial infection cases is estimated to be about 20–40% [16, 17, 18, 19]. The mechanism of transmission can be by direct soiled fomite to mouth contact, or indirect, by touching the contaminated surface and subsequently tapping or rubbing exposed mucosa in the lips, nose, or eyes [20]. Fomites may get contaminated by different means. For example, by contact with droplets from coughing, touch by soiled hands, or by deposition of airborne pathogens [15, 21, 22]. In the nosocomial setting, surfaces that are touched by different people for distinct reasons are known as high-touch or frequently touched surfaces (FTSs). Some examples are doorknobs, hand- and bedrails, and bedside tables, among others. Contaminated FTSs are regarded as vectors for contagion episodes due to the persistence of pathogens [16], which may be transmitted by direct contact with the hands of healthcare workers to medical equipment, patients, visitors, or other personnel [5, 20]. For instance, researchers reported cross contamination of multidrug resistant bacteria between FTSs and staff gloves [23]. In another instance, researchers found viable methicillin-resistant S. aureus (MRSA) in the surroundings of infected patients and on surfaces such as furniture, beds, and clinical equipment, suggesting that the contamination of surfaces near the patient may be an important factor in the transmission of HAIs [9, 24]. Hence, prevention to avoid HAI contagion is especially important in this age where treatment can be difficult to achieve, either due to bacterial antibiotic resistance (AR) or the lack of treatment or vaccines for novel viral infections [25, 26, 27, 28]. In fact, research has shown that the incidence of HAI episodes is related to improper disinfection practices of FTSs [16]. Consequently, interrupting the fomite-mediated transmission cycle by preventive surface disinfection is an effective method to limit the spread of HAIs and is a common practice observed in hospitals today, aimed at reducing the environmental bioburden and incidence of infections [21, 24, 29]. In the words of Page et al. [30] “when it comes to the level of surface contamination, particularly in a healthcare environment, the lower the microbial load the better”.

Fig. 1.

Fig. 1. Simplified schematic of fomite-mediated routes of infection transmission. (A) An infected individual expels pathogen-containing respiratory droplets which settle on an inanimate surface or fomite. (B) The contaminated surface becomes a vector of transmission, able to harbor pathogens for long term, and facilitating the spread of disease through contact. (C) Pathogens are transmitted by touching the contaminated surface. Transmission may reach other surfaces (D), individuals (E), or include self-infection (F), resulting in sickness (G) and continuation of the cycle. Created with BioRender.com.

The disinfection of noncritical surfaces, such as FTSs, is an important infection prevention strategy to minimize HAI transmission [5, 29, 31, 32, 33]. The classification system from Spaulding, shown in Table 1, categorizes the amount of disinfection needed as a function of the procedure to be performed [34, 35]. For instance, surgery and all interventions that require opening sterile body cavities or organs are considered critical and demand a high level of disinfection or sterilization. On the other hand, procedures that involve touching the mucous membranes are classified as semi-critical and the instruments can be disinfected by heat or chemicals.

| Level | Bacteria | Fungi | Viruses | Examples | |||

| Vegetative | Mycobacterium tuberculosis | Spores | Lipid envelope medium size | Non-lipid small size | |||

| Low (non-critical) | Variable | Variable | Disinfection of FTSs | ||||

| Medium (semi-critical) | Variable | Disinfection of endoscopes by heat or chemicals | |||||

| High (critical) | Sterilization of surgical instruments | ||||||

FTSs, frequently touched surfaces.

In contrast, non-critical conditions or procedures involving only contact with healthy human skin require less stringent disinfection procedures. Hence, FTSs can be cleaned by applying low-level disinfection strategies, which commonly use quaternary ammonium compounds, sodium hypochlorite, iodophors, or alcohols. The U.S. Environmental Protection Agency regulates these products, which are labeled as “hospital disinfectants” and are assigned corresponding registration numbers [34, 36]. They are intended to inhibit or kill some bacteria, fungi, enveloped viruses, and some non-enveloped viruses [34, 37]. Low-level disinfection is usually performed by liquid contact for at least one minute using commercially available disinfectant cleaning wipes or sprays and can effectively reduce the population of epidemiologically relevant pathogens by about 99.99% [31]. The disinfectant’s primary mode of action varies with the substance used. For example, alcohol disrupts membrane lipids and denatures proteins causing cell lysis, while chlorine oxidizes thiol groups destroying the cellular activity of proteins. On the other hand, quaternary ammonium compounds denature essential cell proteins and disrupt the lipid membrane, resulting in generalized membrane damage [36, 38].

However, a potential drawback of low-level disinfectants is the continuous, uncontrolled release of biocides into the environment, which can further contribute to the development of AR [39]. Moreover, although the efficacy of these products has been demonstrated, many FTSs remain improperly cleaned, and therefore, potentially contaminated due to the inadequate application of cleaning protocols [31, 40, 41]. To address these issues, some manufacturers have developed systems that either use ultraviolet light or hydrogen peroxide mist, but besides their cumbersome application procedures, these technologies still require standard cleaning [32, 37]. Moreover, even with the application of these systems, the primary concerns related to non-critical disinfection of FTSs still remain: (a) the need for frequent disinfection, (b) the recontamination that can occur at any moment after cleaning, (c) the lack of a system to inactivate the collected pathogen particles, and (d) the risk of infection by touching the re-contaminated surface. Hence, considering the limitations of non-critical disinfection of FTSs, the development of supplemental approaches to reinforce the established procedures is widely justified. In this review, we discuss the role of nanotechnology-based antimicrobial coatings in addressing the creation of comprehensive protection systems to prevent fomite-mediated HAI transmission [42].

The coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic was a wakeup call regarding the preparedness of public healthcare systems around the world in handling devastating consequences of infection transmission. In that moment, some authors pointed out the enormous potential of nanotechnology to address the prevention of fomite-mediated infections by developing nanomaterials for continuous disinfection of FTSs [22, 43, 44]. Their visionary declarations remain valid in this post-pandemic world and apply to the emergent issues related to bacterial resistance development and HAI transmission. Scientists have long sought continuous disinfection of surfaces. For instance, in 1964 Willard and Alexander reported efforts to keep spacecraft surfaces sterile to prevent biological contamination of extra-terrestrial samples. They addressed the issue by developing a self-sterilizing coating formulated with formaldehyde as an active agent, potassium silicate as a binder, and aluminum silicate as a pigment [45]. Their work might have been inspired by previous research in 1962 from Kingston et al. [46] on self-disinfecting surface coatings. In 1985, Matsunaga et al. [47] reported the novel concept of photodisinfection by semiconductor platinum-loaded titanium oxide particles, laying the foundation for the development in 1988 of antimicrobials formed by titanium oxide powder immobilized in polymeric membranes [48]. Similarly, in 1995 Cooney [49] developed and tested copper-based paints to render surfaces self-disinfecting, with results suggesting the potential of these materials to prevent environmental causation of HAIs [50]. However, in that same year, Rutala and Weber [50] raised concerns regarding the toxicity and duration of the antimicrobial effect, suggesting further investigation into the topic. In 2009, Page et al. [30] published an interesting article establishing the major differences in antimicrobial coatings for inanimate environments and those for use in medical devices within the body, which can be considered a separate field of research. Moreover, they classified antimicrobial surfaces for use outside of the human body as (1) antifouling and resistant to bacterial adhesion, (2) biocide-releasing, (3) contact-active, and (4) light activated. In addition, they defined bioactive surfaces as those that can prevent adhesion or destroy adherent microorganisms, and which are crucial to tackle the issues associated with the cycle of fomite-mediated HAIs by reducing or eliminating the formation of microbial reservoirs [30]. More recently, in 2014 Humphreys [51] questioned the potential of self-disinfecting surfaces to interrupt the spread of HAIs. He concluded that although some approaches had shown promissory effects, there was still a need to confirm the persistence of antimicrobial activity as a function of repeated soiling-cleaning cycles and to investigate the open question regarding bacterial resistance development to these new technologies [51]. In 2023, a publication by Butler et al. [52] discussed the relevance of engineered nanomaterials, their antimicrobial properties, and their potential in biomedical applications, including nanocoatings to protect FTSs. They described nanocomposites formed by hybrid nanomaterials used to confer properties such as durability and antimicrobial activity, but warned about lack of regulation in safety, risk analysis, occupational exposure, and development of bacterial resistance [52]. In this article, we review self-disinfecting nanocoatings and mechanisms of action, explore novel lines of research, and discuss the issues of toxicity and bacterial resistance development.

Two main approaches aiming to protect FTSs and prevent HAI transmission are cited in the literature. The macroscale strategy is based on bulk materials such as metallic sheet coatings or polycationic polymers loaded with biocides and is out of the scope of this paper. The nanoscale approach to develop antimicrobial coatings uses nanomaterials such as nanoparticles or nanofibers combined with bulk materials. Both methods use one or more of the following functional principles: (a) formation of anti-adhesive surfaces, (b) bacterial killing by contact, and (c) continuous release of biocides [18, 53, 54, 55, 56, 57, 58]. In the following sections, the nanoscale approach will be discussed, with a focus on the application of nanoparticles and nanocomposites to develop photoresponsive self-disinfecting surfaces.

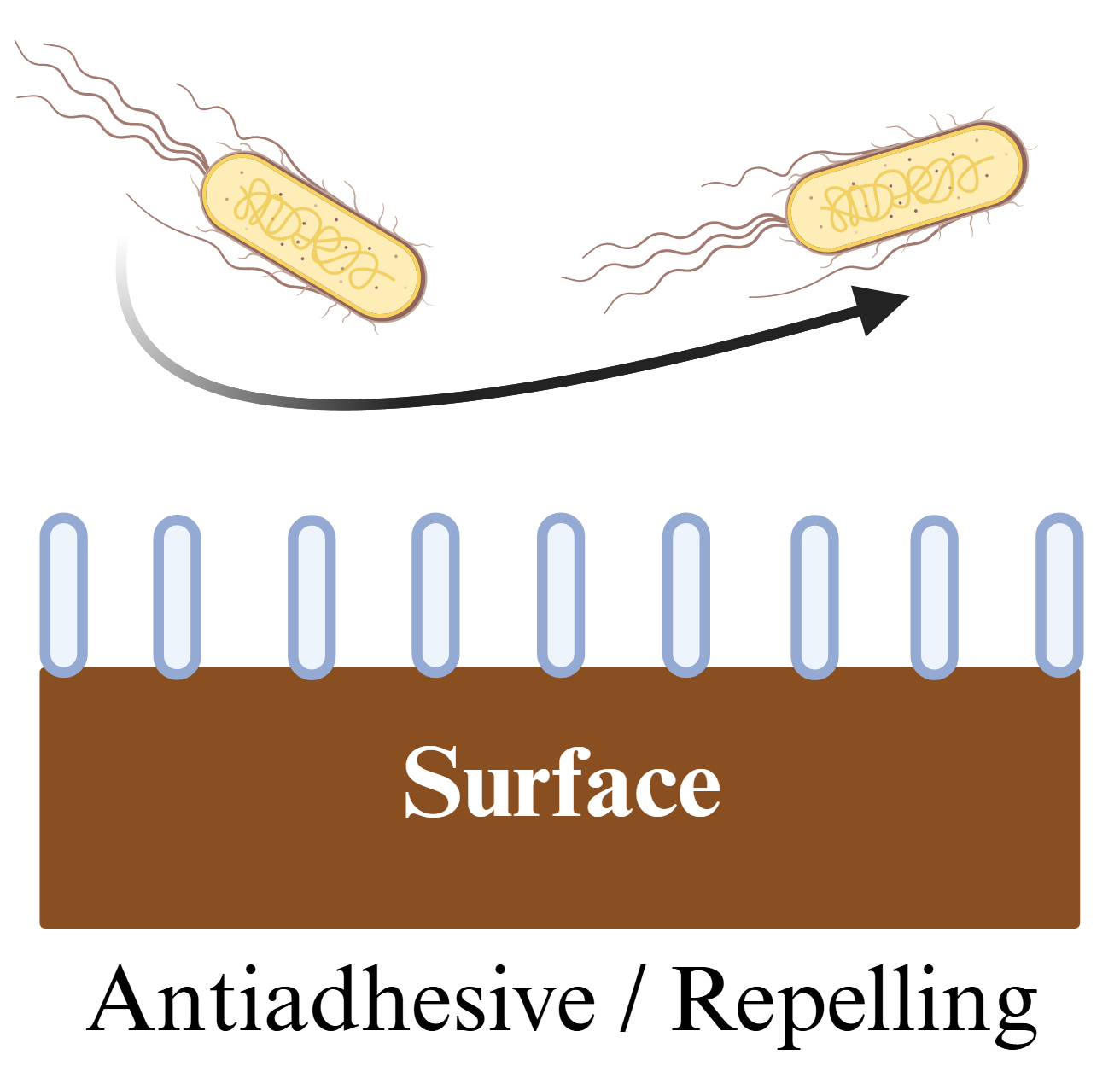

Anti-adhesive surfaces work by decreasing or repelling microbial attachment (Fig. 2). The prevention of planktonic bacterial adhesion is attained by means of hydrophobic or hydrophilic nano topographies, zwitterionic polymers, or a combination of both [57, 58]. In short, surface modifications minimize the adhesion force between surfaces and bacterial adhesive proteins, which in turn limits bacterial attachment, interferes with quorum sensing, and reduces or eliminates the subsequent biofilm formation in a process called antifouling [55]. Nanostructures modify the surface topography, rendering a surface either hydrophobic or hydrophilic. For instance, a structure of nanopillars on an aluminum surface was coated with Teflon® resulting in a 99.9% reduction of the adhesion of S. aureus [59]. In another case, a surface was treated with oxygen plasma to create nanofibers, which increased the hydrophilicity of the surface and decreased the attachment of E. coli due to its negative zeta potential (–40 mV). Then the surface was fluorinated to make it super hydrophobic and self-cleaning by repelling bacterial adhesion [60]. Similarly, zwitterionic polymers inhibit protein adsorption and prevent bacterial adhesion [61, 62]. Furthermore, the combination of nanostructures and zwitterionic polymers has also been explored. For example, nano-brushes made of zwitterionic polymers were attached to a surface made of stainless steel to prevent the adhesion of E. coli and S. aureus [63].

Fig. 2.

Fig. 2. Antiadhesive surface. Planktonic bacteria attachment and subsequent biofilm formation is hindered by repelling, antiadhesive, and antifouling nanostructures. Created with BioRender.com.

However, the most important drawback of this approach is the lack of biocidal activity from the antiadhesive surfaces. Once bacterial proteins anchor and take hold on the surface, microbial colonization and biofilm formation are inevitable [64]. Moreover, anti-adhesive surfaces may become soiled due to non-specific attachment of other materials and/or debris from dead microorganisms, thus reducing the repelling efficacy. Furthermore, since the repelling activity is performed in a close range, the surface must be free of defects that can harbor microorganisms, which can make the surface coating process cumbersome and expensive [65].

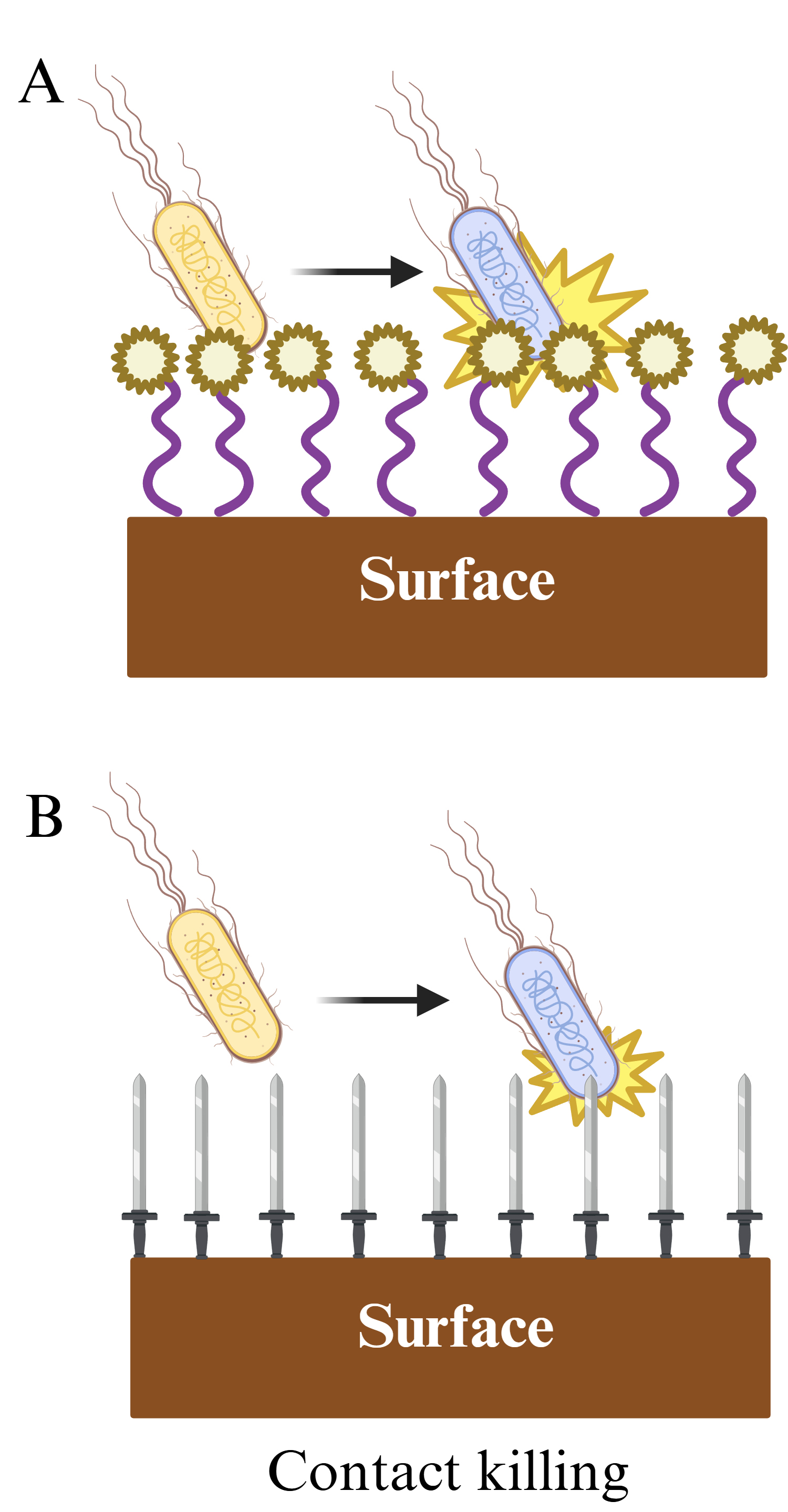

Contact-killing surfaces can overcome the limitations of anti-adhesive surfaces and are mainly based on two strategies: anchoring of polymeric chains conjugated with biocides (Fig. 3A) or nanotopography modifications (Fig. 3B), also called mechano-bactericidal surfaces [66]. They base their biocidal activity on nanostructures such as nanospikes, nanopillars, and nanocones that interact with and damage the bacterial wall. Some of those nanostructures mimic the natural biocide strategies found in insect wings. For example, the nanopillar arrays present on the wings of cicadas (Psaltoda claripennis) have been found to be very effective in puncturing and killing P. aeruginosa cells [67]. In another research study, nano-dagger arrays were prepared with zeolitic imidazolate on a variety of surfaces. The material demonstrated elevated biocidal properties, reaching above 7 log10 reduction when challenged with S. aureus or E. coli [68]. Moreover, the combination of antibacterial materials conjugated to polymer chains attached to surfaces has demonstrated significant potential. In one case, polymeric brushes embedded with silver nanoparticles on top of the brush demonstrated improved antimicrobial properties as compared to nanoparticles deposited at the base of the brush [69]. In another example, polyethyleneimine equipped with nanospikes was tested and demonstrated to efficiently kill bacteria by perforation of the cell membrane [70]. Nevertheless, in spite of their safer mode of action, contact-killing materials may present a potential limiting drawback. As on any other surface, the microbial load can quickly dehydrate, which may affect the contact area with the antimicrobial coating to reduce the biocidal effect [55]. Furthermore, similar to antiadhesive surfaces, debris from dead cells may remain trapped, soiling the surface and reducing its antimicrobial efficacy. Additionally, crevices and irregularities on the surface may compromise its performance and make the fabrication process complex and expensive in order to minimize those defects [65].

Fig. 3.

Fig. 3. Contact killing surfaces. (A) Biocidal chemical effect. (B) Mechano-bactericidal effect. Created with BioRender.com.

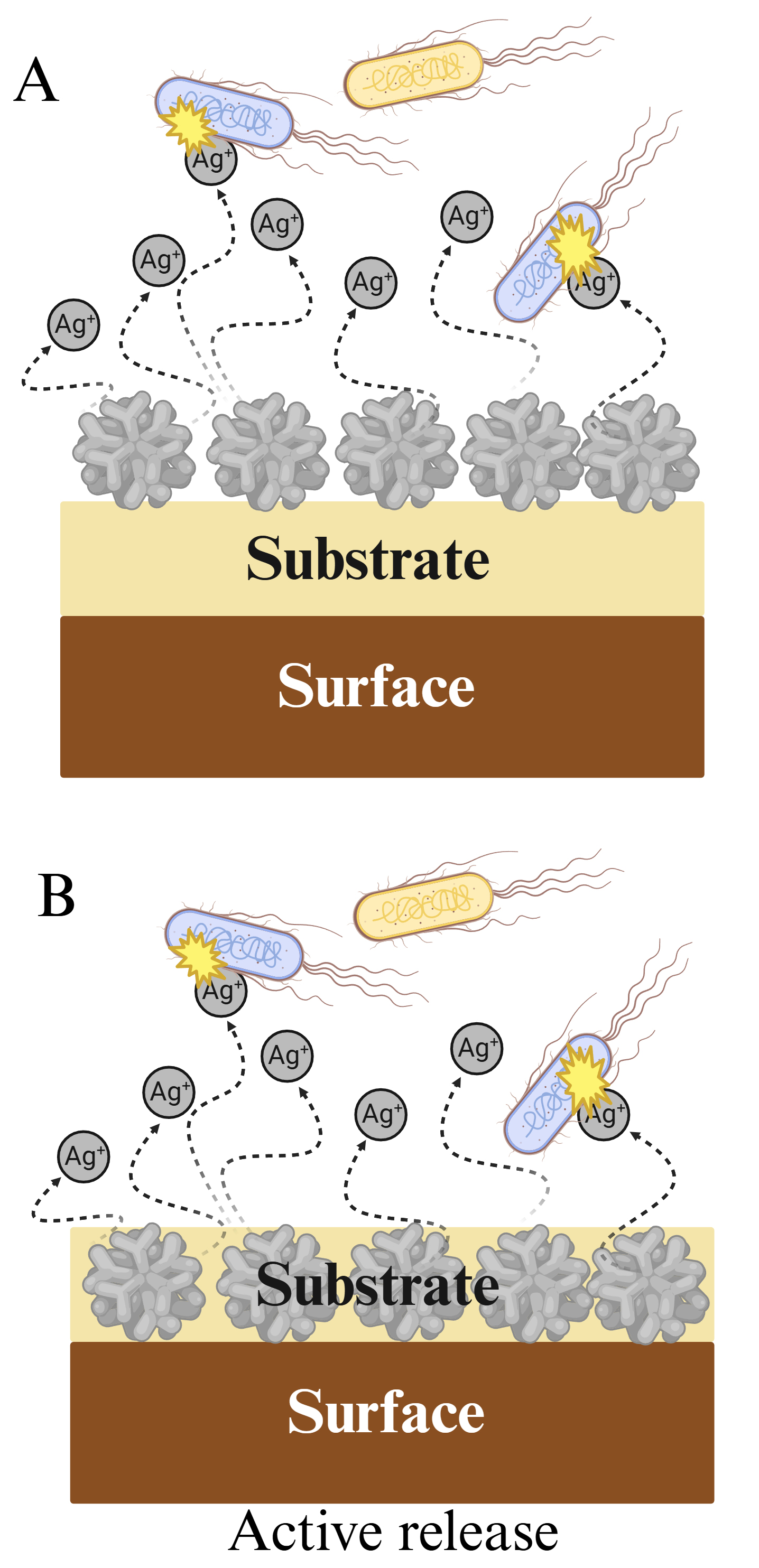

Active release surfaces, also known as biocide-eluting surfaces, comprise most current antimicrobial coating technologies and are based on the combination of a carrier or substrate with one or more nano biocides. In some cases, the substrate is adhered to the surface, with biocide elements attached to the opposite face, from which the active agent is released directly to the interface (Fig. 4A). In some other cases, the antimicrobials are embedded into the carrier forming a nanocomposite (Fig. 4B), where the active agent is mostly released into a porous matrix and is probably transported to the interface by diffusion [58]. In both cases, after reaching the interface, the active agent kills bacteria in either a short or long range. Among the biocidal nanomaterials most commonly used are silver, copper, zinc, and titanium dioxide nanoparticles, but other strategies include inorganic nanoparticles such as carbon quantum dots and graphene nanotubes [71, 72, 73]. The main advantage of active release surfaces is also their main limitation. To exert an antimicrobial effect, the active component must be able to act in proximity or over a long-distance range, implying a continuous, uncontrolled release of biocide to the environment. Although effective, this approach risks environmental contamination and potential AR development. Moreover, another drawback is related to the duration of the antimicrobial effect, due to the exhaustion of the biocide source [65, 74, 75]. However, these issues can be addressed using a combination of nanotechnology approaches. In the following section, the specific details on the application of nanoparticles in active release surfaces and strategies to surpass their constraints will be discussed, with a focus on metal oxide nanoparticles.

Fig. 4.

Fig. 4. Active release surfaces. (A) Surface-bound biocide. (B) Embedded biocide. Created with BioRender.com.

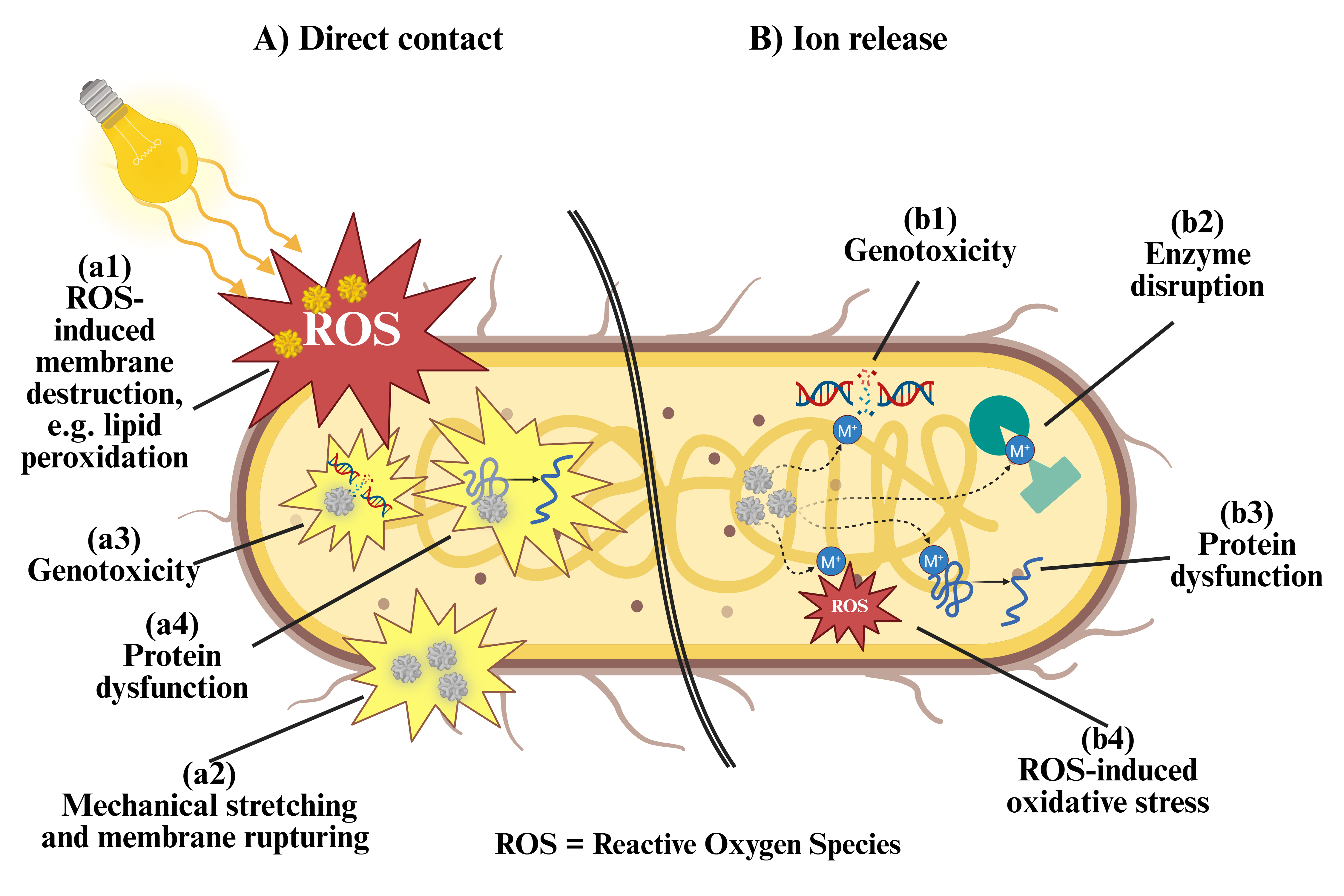

Because of their extended surface areas and physicochemical properties, nanoparticles can present electrostatic interactions with the cell membranes to exert their antimicrobial activity by direct contact. They also can be internalized by bacteria and release toxic ions or biocides. As a result, they may attack multiple targets of bacterial replication simultaneously. Hence, nanoparticle antimicrobial activity may be classified as either by direct contact or by ion release (Fig. 5). Direct contact killing is mediated either by nanoparticle intake or by nanoparticle interactions with the bacterial wall. In the latter, nanoparticles that cannot penetrate the bacterial cell membrane may kill the microorganism by mechanically stretching and rupturing the membrane or by inducing reactive oxygen species (ROS) mediated chemical interactions, e.g., lipid peroxidation [76, 77, 78]. In the former, internalized nanoparticles can severely impair the membrane function, cause protein dysfunction, and block cell replication via genotoxicity, thus resulting in bacterial death [79, 80, 81]. In comparison, bacterial killing by ion release is correlated with the size and metallic nature of nanoparticles. Smaller particle sizes correspond to extended surface areas, which in turn lead to an increased ion production. Hence, smaller nanoparticles are capable of presenting a higher antimicrobial effect [82]. Additionally, smaller particles may have a more efficient way to penetrate the bacterial membrane, even following different endocytic pathways as compared to larger nanoparticles [83]. Once released in the cytosol, metal ions may wreak havoc by inactivating proteins and enzymes, damaging nucleic acids, and promoting the generation of reactive oxygen species for ulterior destruction of cell components [52, 84]. Taken together, the direct contact and ion release mechanisms contribute to the efficient antimicrobial effects of nanoparticles. For instance, by generating oxidative stress, metal ion release, or other non-oxidative factors, nanoparticles can disrupt the bacterial membrane, trigger the destruction of nucleic acids, and generate free radicals that can interfere with protein synthesis, thus reducing the chances for bacterial adaptation and/or antibiotic resistance development [85, 86, 87]. However, depending on the type of nanoparticles, one mechanism may be more relevant than the other. For example, metal oxide nanoparticles are capable of exerting a potent bactericidal effect, which is mainly attributed to their capacity to generate reactive oxygen species, although ion release or physical structure may play an important role [52, 56, 85, 88, 89].

Fig. 5.

Fig. 5. Potential mechanisms of nanoparticle-mediated bactericidal effect. (A) Nanoparticles in direct contact with bacterial membranes can be up taken or remain at the surface, to exert different effects. Non-penetrating nanoparticles can (a1) respond to external stimuli to generate reactive oxygen species, which then induce lipid peroxidation and membrane destruction, or (a2) mechanically pull and break apart the bacterial membrane, causing lysis. On the other hand, internalized nanoparticles can (a3) disrupt bacterial DNA to cause genotoxicity, or (a4) denature proteins, interfering with their function. (B) Internalized nanoparticles can also release ions into the cytosol, which can (b1) damage nucleic acids to cause genotoxicity, (b2) disrupt enzyme function, (b3) inactivate proteins, and (b4) induce intracellular ROS formation and destruction of cell components. Created with BioRender.com.

The different types of nanoparticles used as antimicrobials can be classified as polymeric, non-metallic, metal, and metal oxide nanoparticles (Table 2, Ref. [52, 56, 72, 82, 83, 84, 85, 88, 89, 90, 91, 92, 93, 94, 95, 96, 97, 98]). Although the first three types possess interesting and promising antibacterial activities, their characteristics and modes of action are outside the relevant range of this work. Conversely, the antimicrobial characteristics of metal oxide nanoparticles, specifically titanium dioxide, are particularly interesting to fabricate photoactivated self-disinfecting surfaces and are discussed in the following section.

| Nanoparticle type | Materials | Characteristics | Limitations | References |

| Polymeric | Natural/artificial polymers | ● Biocides are encapsulated in the nanoparticle core or conjugated onto its surface. | ● Loss of activity due to biocide reservoir depletion or biofouling. | [90, 91, 92, 93, 94, 95, 96, 97] |

| ● Mainly used for antibiotic delivery. | ||||

| ● Cationic polymers like chitosan (CS) possess inherent antimicrobial activity attributed to their electrostatic interactions with microbial membranes, e.g., depending on its molecular weight, CS can function as a metal chelator or as disruptor of protein synthesis. | ||||

| Non-metallic | Carbon | ● Amphiphilic carbon dots can bind to and damage bacterial membranes, besides generating ROS by enzymatic and photocatalytic processes. | ● Limited understanding of their potential environmental safety. | [72, 98] |

| ● Poor water dispersibility. | ||||

| Metallic | Aluminum | ● Metallic nanoparticles can generate antimicrobial ions that cause intracellular genotoxicity and protein/enzyme disfunction. | ● Uncontrolled release of biocides to the environment. | [52, 82, 83, 84, 85] |

| Copper | ● Potential environmental toxicity. | |||

| Gold | ||||

| Manganese | ||||

| Platinum | ||||

| Silver | ||||

| Titanium | ||||

| Iron | ||||

| Metal Oxide | Aluminum Oxide | ● Metal oxide nanoparticles can generate a strong antimicrobial effect by their ROS-generating photocatalytic capacity, ion release, and physical structure. | ● Largely unexplored avenue. | [52, 56, 85, 88, 89] |

| Cupric Oxide | ● Potential environmental toxicity. | |||

| Silver Oxide | ||||

| Titanium Oxide | ||||

| Zinc Oxide |

One interesting approach to develop antimicrobial coatings is based on photocatalytic nanoparticles. The concept of photocatalysis to eradicate bacteria was the subject of a study by Michael Wilson [99] in 2003. He applied a layer of cellulose acetate mixed with Toluidine Blue O, a photosensitizer, and inoculated it with MRSA. After 24 hours of exposure to visible light (60 W, 780 lux), he found the MRSA killing efficacy was 94%. Furthermore, he envisioned a coating useful in a nosocomial setting, especially considering that in hospitals most areas are illuminated with light intensities around 1000 lux [99]. Previously, Matsunaga et al. [47, 48] had reported photodisinfection by titanium oxide nanoparticles immobilized in polymeric membranes. Nowadays, research on light-activated antimicrobial coatings is an active field of research that still requires more studies to confirm feasibility and safety of use [10, 41]. As stated by Cloutier et al. [65], the use of metallic nanoparticles as “plasmon-resonators for light-trigger release” is a largely unexplored avenue, but their potential to generate heat or free radicals to interfere with germ replication is an inexpensive and effective strategy to face future pandemics [65, 100].

Out of the different types of photocatalytic metal oxide nanoparticles, titanium oxide nanoparticles are very attractive because of their availability, reduced cost, and photoresponsiveness [101, 102, 103, 104]. Under ultraviolet light irradiation, the nanoparticles of titanium oxide form electron-hole pairs which react with moisture and oxygen producing reactive oxygen species [105, 106, 107, 108]. This characteristic has been used for antimicrobial development or for water-contaminant degradation [77, 109, 110, 111]. However, for antimicrobial coating applications, where the material is coated onto FTSs and is ideally activated by artificial light, this same characteristic is the main drawback of titanium oxide [112]. Moreover, only a few studies have been published on the application of light-activated nanosized titanium oxide as antimicrobial coating [30, 113, 114, 115]. For instance, the TITANIC study, which evaluated the performance of a commercial titanium oxide coating onto nosocomial frequently-touched surfaces, determined that the materials were able to limit E. coli colonization on surfaces, but only had a limited effect on S. aureus [115, 116]. Nevertheless, the study pointed to future lines of research including the improvement of artificial light responsive titanium oxide based antimicrobial coatings and their characteristics like morphology and microstructure, illumination to activate the coating, durability, and testing against relevant healthcare-associated infection pathogens.

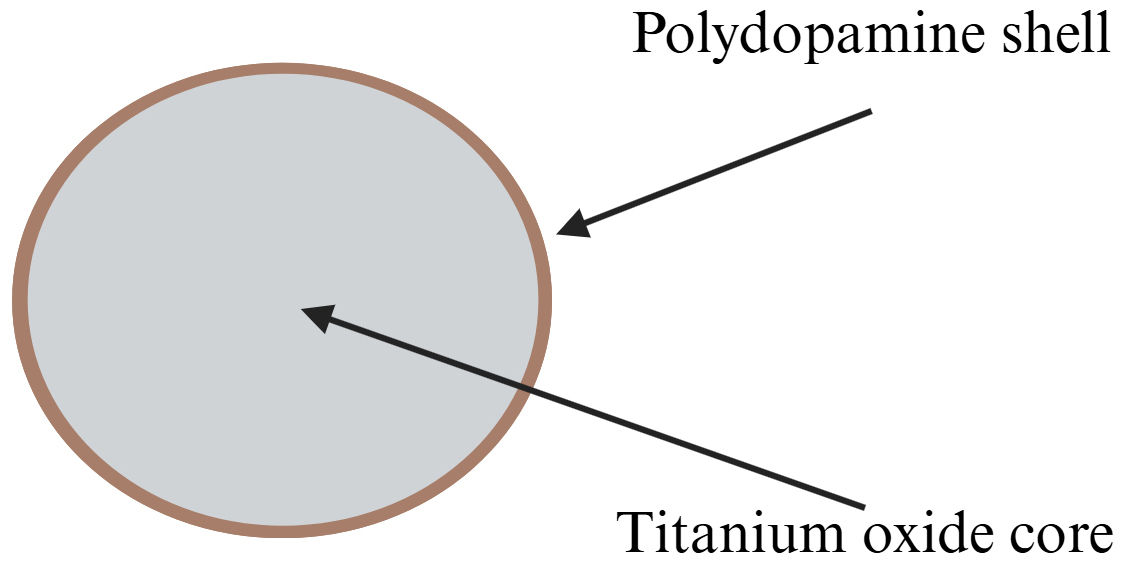

To overcome their limitations and to improve their performance under safer, non-ultraviolet indoor lighting, titanium oxide nanoparticles need to increase their spectral response and quantum efficiency [101, 117]. One proven way to address this issue is by modifying the surface of titanium oxide nanoparticles via oxidative in-situ polymerization of dopamine [118, 119, 120, 121, 122]. This technique, previously reported by Mao et al. [118], allows the creation of a thin layer of polydopamine onto the titanium oxide nanoparticles (Fig. 6). Although its carbonaceous nature impedes polydopamine to show any photocatalytic activity, it can still improve the photocatalytic capacity of titanium oxide by reducing its band gap from 3.25 eV to 2.35 eV, allowing the absorption of visible light [106, 117, 119, 123, 124]. Additionally, polydopamine contributes to elevate the number of

Fig. 6.

Fig. 6. Schematic of photoresponsive polydopamine titanium oxide nanoparticles. The core may be formed by aggregates or primary titanium dioxide nanoparticles, particularly in the anatase tetragonal form. A shell of polydopamine is coated onto the core surface by oxidative polymerization of dopamine. Created with BioRender.com.

Besides their biocidal characteristics to protect FTSs, antimicrobial coatings are expected to satisfy other requirements such as affordability, stability, safety by design, risk management for antibiotic resistance development, and simplicity of on-site application and use [10, 58]. Furthermore, an added benefit is that by enveloping titanium oxide nanoparticles with biocompatible polydopamine shells, the resultant nanoparticles exhibit higher biocompatibility and less risk for the environment, which are the core motivations of safer-by-design materials [125, 128]. To form antimicrobial coatings, these nanoparticles require formulation with a carrier to facilitate their application and attachment to the protected surface. In other words, one way to make the application of photocatalytic antibacterial nanoparticles simple and attractive to the end user is the formulation of a hybrid material in the form of a coating or a paint, as discussed in the next section [112].

Nanocomposites are hybrid materials in which at least one component is in the nano scale [129, 130]. Antimicrobial nanocomposites can be categorized by their main mechanism of action (Table 3, Ref. [62, 64, 66, 71, 72, 73, 76, 83, 131, 132]), including anti-adhesion, contact-killing, and active release of biocides. A few case studies [133, 134] in real-life conditions have been reported in the literature. In one case, a nanocomposite coating named Copper Armour™ was the subject of a 9-week pilot study in 2 rooms in an adult intensive care unit. Four FTSs were coated, including bed rails, overbed tables, bedside tables, and IV poles. Bed rails and overbed tables demonstrated a significant reduction of the microbial burden compared to control surfaces [133]. In another case, a nano textured top surface was created onto different FTSs at the Royal Liverpool University Hospital in the United Kingdom. The copper-based surface coating, denominated iC-nano™, was applied via physical vapor deposition. Results demonstrated

| Nanocomposites | Advantages | Applications | Limitations | References |

| Anti-adhesive | Prevents bacterial adhesion. | Antifouling surfaces | Lack of biocidal activity. | [62, 64] |

| Easily soiled. | ||||

| Contact-killing | High efficiency. | Antimicrobial surfaces | Easily soiled. | [66, 76] |

| Damages the bacterial wall. | Complex fabrication process. | |||

| Active release | High efficiency. | Antimicrobial surfaces | Uncontrolled release of biocides to the environment. Limited availability of biocide. | [71, 72, 73, 83] |

| Biocides kill bacteria in short or long range. | ||||

| Photo-responsive | Potential to generate heat or free radicals. | Antimicrobial surfaces | Largely unexplored avenue. | [131, 132] |

| Inexpensive and effective. |

Photocatalytic nanocomposites formulated as paints or coatings are very simple to apply [112]. Moreover, the incorporation of titanium oxide or other types of nanoparticles into polymeric matrices also has the advantage of the potential contribution of the matrix to the overall performance of the nanocomposite [130, 135, 136]. For instance, Salvadores et al. [137] prepared photocatalytic paints for indoor air purification by mixing nano-sized titanium oxide or carbon-doped titanium oxide with commercial acrylic resins, dispersers, and extenders. The paints were applied by air spray onto acrylic surfaces and evaluated by measuring the decomposition of acetaldehyde under artificial illumination. They concluded that carbon-doped titanium oxide was the most efficent material to remove the contaminant [137]. In an additional example, a titanium oxide-polyvinyl chloride nanocomposite was prepared and dip coated onto medical devices to prevent biofilm formation. The material was exposed to ultraviolet light for 11 hours, and then inoculated with bacteria cultures. Results demonstrated a very high killing efficacy against E. coli [138]. Moreover, since the encasing of nanoparticles into the polymer makes the release of the former into the environment difficult, this kind of material may be less hazardous to the environment [102]. Additionally, the use of surfactants to disperse and stabilize the nanoparticle formulation may add an extra antimicrobial effect, while allowing simpler, one-pot formulations [139, 140].

Photoresponsive nanocomposites specifically designed as antibacterial surface coatings have also been reported. For instance, titanium oxide nanoparticles incorporated in polyurethane were tested as sunlight activated antimicrobial nanocoatings against E. coli. After 60 minutes of light irradiation, the bacterial population had a 99.5% reduction as compared to pure polyurethane [141]. In another example, carbon dots embeddded in a polyurethane matrix were developed for application onto FTSs in the nosocomial setting. These materials demonstrated very high antibacterial efficacy versus E. coli after 30 minutes of exposure to blue light [131]. Similarly, a photoreactive antibacterial paint based on silver-titanium oxide was formulated to reduce HAIs. It was shown that under visible light exposure, the coating exerted high activity against E. coli and moderate efficacy against S. aureus [132]. In another study, modified nano titanium oxide was coated onto PVC plates and exposed to visible light. The material killed 99.8% of E. coli, 98.8% of S. aureus, and 99.0 % of P. aeruginosa after four hours [142]. These studies have shown that photo-responsive nanocoatings can be used to develop self-cleaning antimicrobial surfaces that inhibit or exterminate pathogens, showing a promising potential to limit fomite induced nosocomial infections. However, their effectiveness in real-life conditions at the hospital setting is still largely unexplored. Besides the TITANIC study described in section 2.2.3 [115, 116], no case studies of photoresponsive nanocomposites were found in an exhaustive literature search. Furthermore, the antimicrobial capacity of photoresponsive nanocomposites still needs to be evaluated beyond the traditional gram positive and gram negative models. Future studies should include testing against multi-drug resistant and clinically relevant pathogens [143]. Additionally, the low level of photocatalytic activity in low humidity or dry conditions should be considered when developing new photo-responsive nanocoatings [144]. Finally, an additional aspect to consider is the potential degradation of the polymeric matrix, which may result from the presence of unreacted ROS. This effect may lead to early degradation of the coating, reducing its effective lifespan [30]. Therefore, to ensure the adequate performance and durability of future photocatalytic antimicrobial coatings, their development should be paired with the investigation on ROS-resistant matrices with adequate adhesive properties to facilitate coating application.

In general, there is a lack of understanding on the safety and eco-toxicological effects of antimicrobial coatings due to the absence of comprehensive data [55]. Some antimicrobial coatings are based on the creation of reservoirs of biocidal agents or ion metals, which are subsequently released to exert the bactericidal effect. These approaches show a decrease in their antimicrobial efficacy over time as the reservoir is depleted. Moreover, as the coating suffers environmental degradation, superficial deterioration can result in environmental concerns. For instance, a previous study on the risk and benefits of antimicrobial coatings concluded that metals such as silver, copper, and zinc, release ions and soluble salts that are more toxic to aquatic organisms than to bacteria, and their extensive use can be a factor in the development of AR [57]. Furthermore, the influence of the interaction of cleaning agents and antimicrobial coatings in AR development still needs to be elucidated [55]. In addition, the uncontrolled release of ROS from photoresponsive antimicrobial coatings has the potential to cause tissue damage at high concentrations and may play a role in genotoxicity [145]. Hence, a rigorous assessment of the benefits and risks over the product life cycle should be performed using standardized techniques [146].

Moreover, new antimicrobial coatings should be developed with risk mitigation and safer-by-design concepts in mind [128]. In this sense, photoresponsive coatings using titanium oxide have demonstrated less environmental risk when formulated with anti-corrosion features [147]. Furthermore, the potential toxicity of titanium oxide nanoparticles can be reduced by the application of polydopamine shells, which not only confer photoresponsive properties to the material but also enhance its biocompatibility [125]. Hence, future developments in photoresponsive antimicrobial coatings could be safer to the environment by the application of polydopamine coatings or similar materials, but their environmental safety should be validated with standard assessments promoted by international agencies, such as the Organization for Economic Co-operation and Development [148].

The revolutionary improvements in human health and medical sciences resulting from the discovery of antibiotics are at risk, due to the emergence of bacterial AR [149]. Bacteria can adapt and deal with single-mechanism antibiotics by modifying, inactivating, or limiting their uptake. Or in other cases, by simply expelling them using efflux pumps [150, 151]. Hence, a crucial question regarding the use of photocatalytic antimicrobial coatings is if they may prevent AR development. Evidence suggests a positive outcome, but future research in the topic is needed. For instance, it is known that AR only develops when a specific site is targeted by a single mechanism of action. However, when the mode of action works simultaneously through multiple pathways, there is an increased chance of avoiding AR development [30]. Hence, combinatory therapies or multi-mechanism approaches have a substantial potential to overcome the disadvantages of individual therapies by enhancing the antibacterial performance and limiting AR development [152]. Photocatalytic nanoparticle systems are one of those promissory approaches since their mode of action is multi-targeted and non-selective. Nanoparticles may minimize AR [86, 87] by breaking the cell membrane [76, 77, 78] causing lysis and disrupting nucleic acids, protein synthesis, and enzymatic processes [79, 80, 81, 85]. Thus, the combination of antibacterial nanoparticles and polymeric carriers to form antimicrobial coatings has a high potential to alleviate the crisis of AR development by satisfying specific criteria on safety-by-design, risk management, stability, and simplicity of application and use [10, 58].

Because of the advanced materials and technology involved, nanotechnology-based antimicrobial coatings potentially may be more expensive than traditional coatings. Nevertheless, factors such as function, materials used, coating application methods, and type of coating, may have a significant influence in the cost. For instance, higher initial costs may be upset by extended functionality and durability. Furthermore, durability may also have a significant impact on associated maintenance and long-term costs [112]. Hence, a key design aspect should be an adequate carrier selection to facilitate application, increase durability, and potentiate the antimicrobial effects from nanocomponents. Overall, potential elevated costs should not hinder the search for effective antimicrobial coatings that may offer higher long-term benefits by reducing HAI transmission and associated healthcare costs.

Novel light-activated antimicrobial nanocoatings aim to reduce fomite-mediated infections by blocking pathogen adhesion or killing by contact or biocide release. In the case of photocatalytic metal oxide-based materials, ROS generation is a major mechanism of action [153]. A different approach, also based on photocatalysis, is the use of transition metal carbonyl complexes to release carbon monoxide (CO), which has been proven to reduce proliferation and cause the rapid death of E. coli and S. aureus [154]. This strategy was applied to generate nanofiber-based structures with integrated photo-responsive carbon monoxide-releasing molecules that exhibited antimicrobial behavior when exposed to visible light near the UV light range [155]. Results demonstrated a 70% reduction of S. aureus biofilms after exposure to visible light (405 nm). Interestingly, the researchers also determined that the material was able to produce ROS, thus enhancing the antimicrobial properties of the nanofibers. This technology, originally developed as a therapy for skin wound infections, could easily be repurposed to create antimicrobial coatings by mixing adequate amounts of nanofibers with an appropriate adhesive carrier.

Another developing approach is based on the photothermal effect, which occurs by the interaction of electrons with photons, and subsequent generation of thermal energy by the relaxation of the former [108]. This in turn results in an antimicrobial effect due to the thermal degradation of bacterial membranes [156, 157, 158]. For example, S. aureus populations were reduced by 3.0

These few examples of emerging technologies in antimicrobial nanocoatings reflect the sense of urgency among the infection prevention community to protect the public health by disrupting an important pathway of disease transmission [160]. However, any future direction on antimicrobial coating development should consider the classification of such materials. In the U.S., the Environmental Protection Agency classify antimicrobial coatings as non-food use antimicrobial pesticides for noncritical environmental surfaces in medical premises and equipment. Hence, future research should include selected studies from the agency’s guidelines to test antimicrobial efficacy, health effects, and occupational and residential exposure, among others [161, 162]. Moreover, besides the commonly studied microorganisms, E. coli and S. aureus, new research should include clinically relevant pathogens such as K. pneumoniae, P. aeruginosa, A. baumannii, Vancomycin-resistant Enterococci, and C. difficile, as well as Candida spp. and Aspergillus spp. [8, 163, 164]. In addition, future work should include the exploration of enhanced photocatalytic antimicrobial coatings and their activity against hard-to-inactivate prions, infective agents that have the potential to transmit neurodegenerative disorders to humans and animals [165].

Antimicrobial coatings and nanocoatings are a promissory strategy to tackle disease transmission, especially infections transmitted through the fomite-mediated pathway. In specific, photoresponsive antibacterial nanocoatings may have the capacity to fill some of the gaps existing in other approaches, such as the limited duration of biocidal reservoirs or the uncontrolled release of metal ions to the environment. Moreover, owing to the multiple mechanisms involved in their biocidal effect, these materials also may be an efficient way to address the growing issues related to antibiotic resistance development. Nevertheless, the essential questions posed by Humphreys [51] and Butler et al. [52] remain unanswered. There is still a need to investigate the permanence of biocidal activity along the life cycle of the materials, the long-term effect on bacterial resistance development, the safety, environmental fate, toxicity, and efficacy of antimicrobial coatings against the most relevant nosocomial pathogens.

AR, antibiotic resistance; HAIs, healthcare-associated infections; FTSs, frequently touched surfaces; MRSA, methicillin-resistant S. aureus; ROS, reactive oxygen species.

Conceptualization, KTN and LSG; Funding acquisition, KTN and LSG; Investigation, LSG, IDGR, and LD; Resources, KTN; Supervision, KTN and LSG; Visualization, LSG; Writing – original draft, LSG; Writing – review & editing, KTN, LSG, IDGR, and LD. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript. All authors have participated sufficiently in the work and agreed to be accountable for all aspects of the work.

Not applicable.

We would like to thank the Reviewers for their time and effort. Their comments and insights contributed significantly to improving the quality of this manuscript.

The authors wish to recognize the support from the U.S. National Institutes of Health (NIH) and the National Science Foundation (NSF). Research reported in this publication was supported by the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases under award number F31 AI169954 (LSG), and partly supported by the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute under award number R01 HL158204 (KTN, and IDGR is a recipient of HL158204-02S1 award). Additionally, IDGR and LD were supported by NSF Partnerships for Research and Education in Materials (PREM) program at The University of Texas at Arlington (NSF DMR-2425164). The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health.

LSG has a potential research conflict of interest due to financial interest with Active BioMed LLC. A management plan has been created to preserve objectivity in research in accordance with UTA policy. The rest of the authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

References

Publisher’s Note: IMR Press stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.