1 Department of Microbiology, Federal University Lokoja, 260102 Lokoja, Kogi State, Nigeria

2 Department of Medical Microbiology and Parasitology, Ladoke Akintola University of Technology, 210214 Ogbomoso, Oyo State, Nigeria

3 Department of Medical Microbiology and Parasitology, University College Hospital (UCH), 200212 Ibadan, Oyo State, Nigeria

4 Genomics and Sequencing Research Laboratory, National Reference Laboratory, Nigeria Centre for Disease Control, Gaduwa, 900104 Abuja, Nigeria

5 Research Ethics Unit, UNIOSUN Teaching Hospital, 230211 Osogbo, Osun State, Nigeria

6 Department of Biological Sciences, Faculty of Sciences, Kings University, 560102 Ode-Omu, Osun State, Nigeria

7 Humboldt Research Hub, Center for Emerging and Re-emerging Infectious Diseases, Ladoke Akintola University of Technology, 210214 Ogbomoso, Oyo State, Nigeria

Abstract

Klebsiella pneumoniae possesses a range of virulence factors that enable this bacterium to colonize, persist, adhere to host tissues, invade, and cause disease. The pathogen poses a significant risk to immunocompromised individuals and those with pre-existing health conditions. This research focused on assessing the virulence traits and biofilm-forming abilities of K. pneumoniae isolates in Nigeria.

Clinical samples were collected from 420 patients across seven tertiary hospitals in Southwestern Nigeria between February 2018 and July 2019. Standard microbiological procedures were employed to identify Klebsiella isolates. The presence of six specific virulence genes was determined using polymerase chain reaction (PCR): fimH, kfu, rmpA, uge, wcaG, and aero_1. Additionally, PCR was utilized to identify capsular serotypes K1, K2, and K5.

A substantial proportion (82%) of K. pneumoniae isolates demonstrated the ability to form biofilms. Of these, 51 isolates (39.8%) were classified as strong biofilm producers, 54 (42.2%) as moderate, and 23 (17.9%) showed no biofilm production. Among the virulence genes detected, uge was the most common (68.0%), followed by fimH (65.6%), aero_1 (63.3%), kfu (29.7%), rmpA (28.1%), and wcaG (14.1%). Statistically significant correlations were found between biofilm formation and the presence of aero_1, fimH, kfu, and rmpA. In terms of capsular serotypes, the majority of isolates were non-K1/K2/K5 (84.4%), with lower frequencies observed for K2 (7.0%), K1 (5.5%), and K5 (3.1%).

This study highlights that the aero_1, fimH, and uge genes are frequently present in K. pneumoniae isolates from this region, and that these strains often carry multiple virulence genes. The strong virulence potential and biofilm-forming capacity of these isolates underscore a significant public health threat, particularly in vulnerable populations.

Keywords

- biofilm formation

- K. pneumoniae

- virulence genes

Klebsiella pneumoniae is an opportunistic pathogen responsible for a range of infections in humans, including sepsis, urinary tract infections, cholangitis, osteomyelitis, meningitis, liver abscesses, and pneumonia [1]. This pathogen is particularly concerning in healthcare settings, where Klebsiella pneumoniae is associated with increased morbidity and mortality, especially among immunocompromised patients and those with underlying conditions [2].

The clinical manifestations of K. pneumoniae infections vary, which can be partly attributed to the presence of specific virulence factors and the antimicrobial susceptibility profile of the pathogen. Among these factors, the bacterial capsule is a crucial determinant of virulence. Composed of strain-specific capsular polysaccharides (K antigens), the capsule helps the bacteria evade phagocytosis and suppress host immune responses [3]. Notably, capsular types K1 and K2 are highly virulent and linked to severe infections in both experimental models and humans, particularly in cases of community-acquired liver abscess syndrome, septicemia, and pneumonia [4, 5, 6, 7]. These serotypes, especially K1, K2, and K5, are also implicated in other diseases, such as metritis in mares [8]. Furthermore, K. pneumoniae strains expressing the mucoviscocity-associated gene A (magA) or the capsule-associated gene A (K2A) are predominantly associated with serotypes K1 and K2, respectively [9, 10].

Capsule typing remains a widely used method for distinguishing K. pneumoniae isolates, demonstrating reliable reproducibility for clinical applications [11, 12]. In addition to the capsule, other virulence factors, such as the rmpA gene (which regulates the mucoid phenotype), endotoxin-related genes (uge and wcaG), and iron acquisition genes (kfu), contribute significantly to the pathogenic potential of this bacterium. K. pneumoniae strains typically express Type 1 fimbriae, encoded by the fimH gene, which play a key role in adherence to epithelial cells, particularly those in the bladder [13, 14]. Additionally, the kfu gene, involved in iron acquisition, is found in invasive strains and is linked to capsule formation and enhanced virulence [4].

These virulence factors, alone or in combination, determine the severity and outcome of infections caused by K. pneumoniae. Therefore, understanding the expression of these factors is critical for comprehending the pathogenicity of the pathogen and identifying potential therapeutic targets.

This study aimed to characterize the virulence factors present in clinical K. pneumoniae strains from Southwestern Nigeria. By focusing on key virulence genes, such as aero_1, fimH, and uge, and examining biofilm formation, this research can enhance our understanding of the behavior of the pathogen in this underrepresented geographical region. Additionally, this study aimed to investigate the relationship between biofilm formation and virulence gene expression, offering insights into the mechanisms through which K. pneumoniae can evade host immune responses and contribute to the persistence of infections. These findings are essential for developing public health strategies to control the spread of multidrug-resistant K. pneumoniae in Southwestern Nigeria and similar regions.

A total of 420 clinical samples were obtained from patients presenting with various health conditions across six states in Southwestern Nigeria. Sample types included urine, blood, sputum, wound swabs, high vaginal swabs, pus, stool, tracheal aspirates, and semen. These specimens were collected from seven tertiary healthcare institutions: Ladoke Akintola University of Technology Teaching Hospital (Osogbo, Osun State), Obafemi Awolowo University Teaching Hospitals Complex (Ile-Ife, Osun State), Lagos University Teaching Hospital (Lagos State), Federal Medical Centre (Abeokuta, Ogun State), University College Hospital (Ibadan, Oyo State), Federal Medical Centre (Ido-Ekiti, Ekiti State), and Federal Medical Centre (Owo, Ondo State). The collection spanned from February 2018 to July 2019. Alongside the specimens, relevant clinical and demographical information was recorded from the participating healthcare centers.

All 420 clinical specimens were cultured on blood agar and MacConkey agar and incubated at 37 °C for 18 to 24 hours. A single isolate per sample was selected for further analysis. Bacterial growth was assessed based on colony morphology and biochemical properties, followed by confirmation using the Microbact GNB 12E identification system. Final confirmation of K. pneumoniae isolates was conducted using the polymerase chain reaction (PCR) with species-specific primers.

Biofilm formation was assessed quantitatively using a microtiter plate assay, recognized as a standard approach for biofilm detection [15]. Fresh colonies were inoculated into 10 mL trypticase soy broth (TSB) supplemented with 1% glucose and incubated at 37 °C for 24 hours. The resulting cultures were diluted 1:100 with fresh TSB. Each well of a sterile 96-well flat-bottom polystyrene plate (Costar, Sigma-Aldrich, USA) was filled with 200 µL of the diluted bacterial suspension. Negative controls included sterile broth and reference strains. After incubating at 37 °C for 24 hours, the wells were gently emptied and washed four times with 0.2 mL phosphate-buffered saline (PBS, pH 7.2) to remove any remaining planktonic cells. The attached biofilms were fixed with 2% sodium acetate, stained with 0.1% crystal violet, and then rinsed with deionized water. Plates were then air-dried. The absorbance of the stained biofilm was measured at 570 nm using an ELISA microplate reader (Model 680, Bio-Rad, UK). All tests were conducted in triplicate and repeated three times. Mean absorbance values were calculated, and background absorbance (media-only wells) was subtracted. Biofilm production was categorized based on optical density (OD) values: OD

Genomic DNA was extracted using the boiling method. PCR was employed to detect specific capsular serotypes (K1 (magA), K2 (k2a), and K5) and virulence-associated genes, including rmpA (regulator of mucoid phenotype), aero_1 (aerobactin), fimH (type 1 fimbrial adhesin), uge (UDP-galacturonate 4-epimerase), kfu (iron uptake system), and wcaG (associated with outer core lipopolysaccharide biosynthesis). Details on the primers and expected PCR product sizes are provided in Table 1 (Ref. [17, 18, 19, 20, 21, 22, 23, 24]).

| Primer | Sequence 5′–3′ | Annealing temperature | Product size (bp) | Reference |

| aero_1-F | GCATAGGCGGATACGAACAT | 50 °C | 556 | [17] |

| aero_1-R | CACAGGGCAATTGCTTACCT | |||

| fimH F | TGCTGCTGGGCTGGTCGATG | 60 °C | 550 | [18] |

| fimH R | GGGAGGGTGACGGTGACATC | |||

| rmpAF | ACTGGGCTACCTCTGCTTCA | 55 °C | 535 | [19] |

| rmpAR | CTTGCATGAGCCATCTTTCA | |||

| uge F | TCTTCACGCCTTCCTTCACT | 55 °C | 534 | [20] |

| uge R | GATCATCCGGTCTCCCTGTA | |||

| wcaG F | GGTTGGKTCAGCAATCGTA | 58 °C | 169 | [21] |

| wcaG R | ACTATTCCGCCAACTTTTGC | |||

| Kfu F | GAAGTGACGCTGTTTCTGGC | 54 °C | 797 | [20] |

| Kfu R | TTTCGTGTGGCCAGTGACTC | |||

| K1 F | GTAGGTATTGCAAGCCATGC | 55 °C | 1283 | [22] |

| K1 R | GCCCAGGTTAATGAATCCGT | |||

| K2 F | GGAGCCATTTGAATTCGGTG | 65 °C | 646 | [23] |

| K2 R | TCCCTAGCACTGGCTTAAGT | |||

| K5 F | TGGTAGTGATGCTCGCGA | 55 °C | 280 | [24] |

| K5 R | CCTGAACCCACCCCAATC |

Data analysis was conducted using the IBM Statistical Package for the Social Sciences (SPSS), version 25 (IBM Corp., Armonk, NY, USA). The presented results are expressed as frequencies and percentages. Associations between variables were assessed, and a p-value of less than 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Out of all the examined K. pneumoniae isolates, 82% demonstrated the ability to form biofilms. Specifically, 51 isolates (39.8%) were categorized as strong biofilm producers, 54 isolates (42.2%) showed moderate biofilm-forming ability, while 23 isolates (17.9%) did not exhibit any detectable biofilm production (Table 2).

| Biofilm status | Number (%) |

| Strong biofilm producer | 51 (39.8) |

| Moderate biofilm producer | 54 (42.2) |

| Non-biofilm producer | 23 (17.9) |

| Total | 128 |

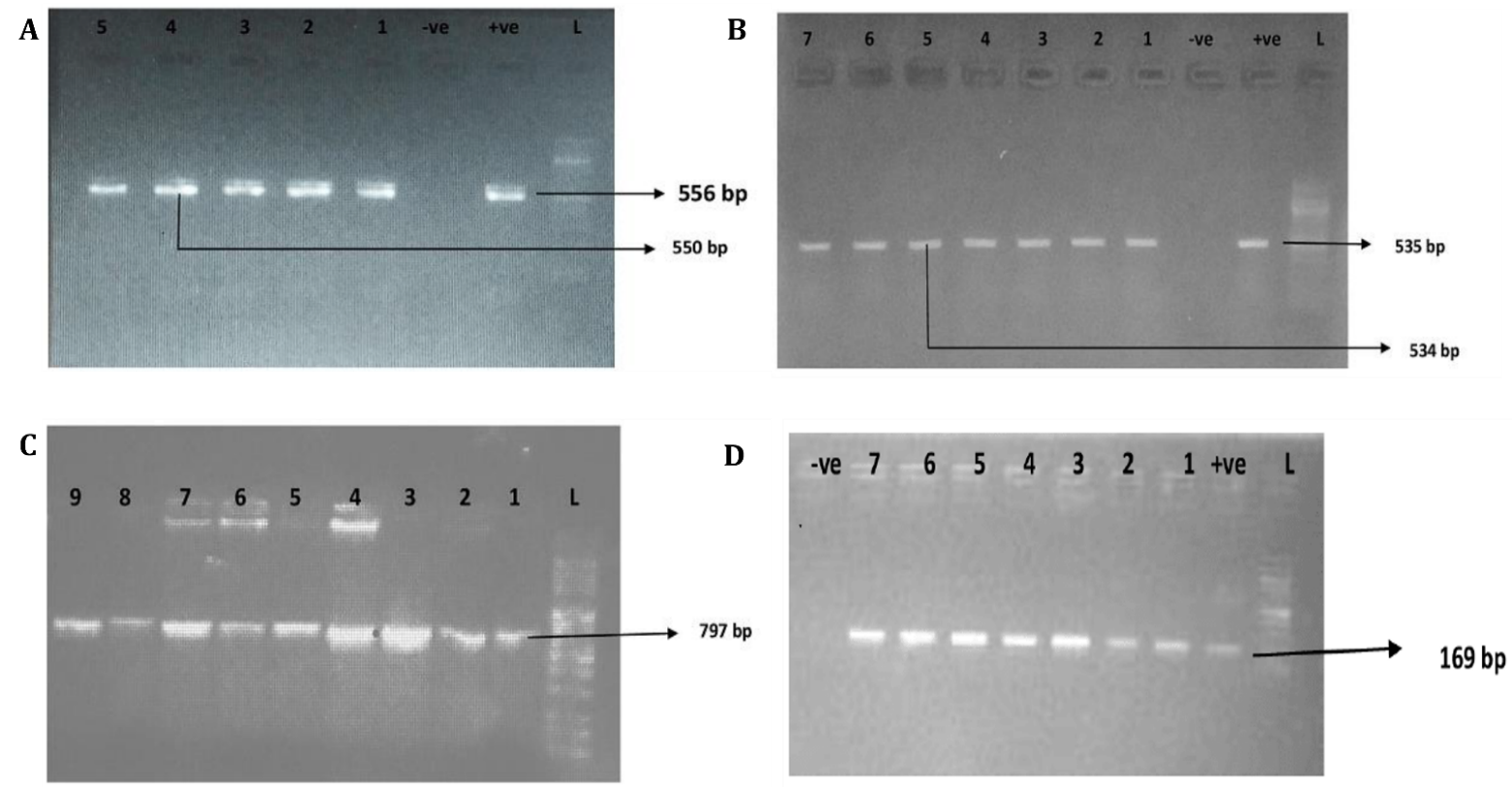

Among the virulence genes analyzed, uge was the most frequently detected (68.0%), followed closely by fimH (65.6%) and aero_1 (63.3%); other identified genes included kfu (29.7%), rmpA (28.1%), and wcaG (14.1%). The presence of these genes in the isolates was confirmed via agarose gel electrophoresis, as illustrated in Fig. 1.

Fig. 1.

Fig. 1. Agarose gel electrophoresis of the PCR amplification of selected virulence genes in K. pneumoniae isolates. (A) Amplification of aero_1 (lanes 1–3; expected size: 556 bp) and fimH (lanes 4–5; expected size: 550 bp). (B) Detection of rmpA (lanes 1–4; 535 bp) and uge (lanes 5–7; 534 bp). (C) Amplification of the kfu gene (lanes 1–9; 797 bp). (D) Detection of the wcaG gene (lanes 1–7; 169 bp). Lane “L” denotes the 100 bp DNA ladder; “+ve” and “-ve” represent positive and negative controls, respectively. Arrows indicate the expected sizes of the PCR products. PCR, polymerase chain reaction.

Isolates capable of forming biofilms exhibited a significantly greater prevalence of the aero_1, fimH, rmpA, and kfu genes compared to non-biofilm-forming counterparts. Among these, kfu-positive strains demonstrated the highest rate of biofilm production (97.4%), whereas the wcaG-positive isolates showed the lowest biofilm-forming ability (83.3%) (Table 3).

| Virulence genes | Biofilm forming K. pneumoniae (n = 105) | Non-biofilm forming K. pneumoniae (n = 23) | p-value |

| Aero_1 (81) | 76 (93.8%) | 5 (6.2%) | 0.002 |

| fimH (84) | 78 (92.9%) | 6 (7.1%) | 0.003 |

| rmpA (36) | 34 (94.4%) | 2 (5.6%) | 0.001 |

| Uge (87) | 79 (90.8%) | 8 (9.2%) | 0.263 |

| wcaG (18) | 15 (83.3%) | 3 (16.7%) | 0.337 |

| Kfu (38) | 37 (97.4%) | 1 (2.6%) | 0.0001 |

Of the 128 K. pneumoniae isolates, 5.5% belonged to the K1 serotype, 7.0% to K2, and 3.1% to K5. The remaining 84.4% did not belong to any of these three serotypes. This is presented in Table 4.

| Serotype | Number (%) |

| K1 | 7 (5.5) |

| K2 | 9 (7.0) |

| K5 | 4 (3.1) |

| Others | 108 (84.4) |

| Total | 128 |

The pathogenicity of Klebsiella pneumoniae is primarily attributed to the presence of diverse virulence factors, including capsular polysaccharides, endotoxins, siderophores, iron-acquisition systems, and adhesins. These elements enable the bacterium to resist host defenses and establish infections, particularly in immunocompromised individuals or those with underlying health conditions. Specifically, the capsular polysaccharide plays a vital role in resistance to phagocytosis and serum-mediated killing among clinical isolates of K. pneumoniae [25].

Biofilm formation represents another significant mechanism contributing to the pathogenic potential of K. pneumoniae. Biofilms provide a physical barrier that enhances bacterial survival against antimicrobial agents and host immune responses. The protective nature of biofilms and outer membrane lipoproteins has been widely reported, with biofilm-producing bacteria demonstrating a marked resilience compared to non-biofilm producers [26].

In this study, 82% of the K. pneumoniae isolates were capable of forming biofilms, a finding that is consistent with previous research. For instance, Karimi et al. [27] reported biofilm formation in 74.5% of clinical isolates. The variability in biofilm-forming ability among isolates may be influenced by several factors, including the physicochemical characteristics of the bacterium, environmental factors such as temperature and pH, the nature of the surface to which the bacteria adhere, and the presence of surface appendages, such as fimbriae and pili [28].

Among the virulence genes investigated, rmpA was identified in 28.1% (36/128) of isolates. This is higher than the 15.4% prevalence reported in a similar study in China [29] but significantly lower than the 93.75% found in Taiwan, where the study focused on community-acquired isolates [30]. This discrepancy may reflect differences in strain types, sample sources, or geographic variations.

The uge gene, which is associated with capsule production and contributes to phagocytosis resistance [31], was present in 68.0% of our isolates. This is notably higher than the 48.6% reported in India [32], but lower than the 90.2% reported in Southeastern China [33]. Thus, this widespread presence of uge in our isolates reinforces the role of this gene as a fundamental virulence factor in K. pneumoniae.

The aerobactin-associated gene aero_1 was detected in 63.3% of the isolates, a figure considerably higher than the 5.4% reported in India [32]. This high prevalence is significant, as aerobactin is known to facilitate iron acquisition, providing bacteria with a survival advantage in iron-limited environments, such as the human host. Moreover, the presence of aerobactin has been strongly linked to hypervirulence phenotypes.

Another capsule-associated gene, wcaG, which may play a role in capsular fucose synthesis and immune evasion [34], was detected in 14.1% of isolates. This is higher than the 3.8% observed in China [29] but lower than the 68.7% reported by Zhang et al. [33] in Southeastern China. The regional variability in the prevalence of wcaG may reflect the dominance of different clonal lineages.

The iron-acquisition gene kfu was found in 29.7% of isolates, aligning closely with the 27.8% prevalence reported in India [32], but notably higher than the 3% documented in Pakistan [35]. Differences in the distribution of iron-uptake genes, such as kfu, across studies may be due to various factors, including geographic location, the site of sample collection, the clinical source of isolates, and differences in antibiotic resistance profiles. It is also plausible that the isolates lacking kfu and aero_1 possess other iron acquisition systems, such as yersiniabactin, salmochelin, or enterobactin, which were not assessed in this study.

A significant finding of this study is the strong association between biofilm formation and the presence of specific virulence genes, particularly aero_1, fimH, kfu, and rmpA. Several previous studies have also presented similar associations, suggesting that genes related to fimbriae, capsular polysaccharide synthesis, and lipopolysaccharide biosynthesis contribute synergistically to biofilm formation. Indeed, the process of biofilm formation typically begins with initial adhesion mediated by fimbriae and lipopolysaccharides, followed by the maturation of the biofilm structure facilitated by the capsule [36].

Capsular serotypes K1 and K2 have historically been considered the most virulent among K. pneumoniae strains, especially in cases of septicemia and liver abscesses [37]. In this study, the prevalence of the K2 serotype was 7.0%, which is lower than the 20% reported by Lee et al. [38] but higher than the 5% found in Sweden [39]. The K1 serotype was identified in 5.5% of isolates, a figure significantly lower than the 64.3% reported by Lee et al. [38], but, likewise, higher than the 1.4% reported in Sweden [39]. Interestingly, a study from Iraq reported a much higher prevalence of the K1 serotype (61.11%), which contrasts with our findings [25].

The majority of our isolates (84.4%) belonged to serotypes other than K1, K2, and K5, which is consistent with the 90% prevalence of non-K1/K2 serotypes reported in Côte d’Ivoire [40]. Although K1 and K2 are considered classical hypervirulent serotypes, emerging evidence suggests that other serotypes, including non-K1/K2/K5 types, are also capable of causing severe infections [30]. Our findings support this notion, indicating that non-K1/K2/K5 serotypes are predominant in Southwest Nigeria and may play an important role in disease pathogenesis.

These results revealed the diverse virulence arsenal of K. pneumoniae isolates in Southwest Nigeria. While classical hypervirulence markers, such as K1/K2 serotypes and rmpA, are relatively infrequent, the high prevalence of other virulence genes and the ability of most isolates to form biofilms suggest a significant pathogenic potential. Nonetheless, continuous surveillance of both virulence and resistance patterns is crucial for a more comprehensive understanding of the evolving threat posed by K. pneumoniae in both community and hospital settings.

This study demonstrates that Klebsiella pneumoniae isolates from clinical settings in Southwestern Nigeria harbor a diverse array of virulence genes, many of which contribute to the pathogenic potential of this bacterium. Notably, a strong correlation was observed between biofilm-forming ability and the presence of specific virulence factors, including aero_1, fimH, rmpA, and kfu. These genes are well-documented for enhancing bacterial adhesion, immune evasion, and survival under hostile conditions, including exposure to antibiotics.

Furthermore, the predominance of serotypes other than K1, K2, and K5 among the isolates suggests that strains beyond the classical hypervirulent types are playing an increasingly important role in disease causation. This finding reinforces emerging global evidence that non-K1/K2 serotypes can still exhibit considerable virulence, particularly when equipped with multiple pathogenicity-related genes.

Given these insights, there is a pressing need for continued molecular surveillance, especially in resource-limited settings. Monitoring the distribution of virulence genes and biofilm-forming capacity should be integrated into infection control strategies to enhance the effectiveness of these strategies. Meanwhile, preventive measures, improved diagnostics, and stewardship programs remain essential in curbing the clinical impact and potential spread of both classical and emerging hypervirulent K. pneumoniae strains in the region.

PCR, Polymerase Chain Reaction; magA, Mucoviscosity-associated gene A; rmpA, regulator of mucoid phenotype A; LPS, Lipopolysaccharides; uge, Uridine diphosphate galacturonate 4-epimerase; kfu, Klebsiella ferric iron uptake; GNB, Gram -Negative Bacteria; OD, optical density; SPSS, Statistical Package for Social Sciences software.

The datasets used and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

OAO and GO conceived the study. OAO, GO, and ROO designed the study and prepared the literature review and methodology. GO and FDO collected the data. AAA, OBM, and OJA performed the data analysis, with contributions from RAO. GO and RAO drafted the initial manuscript. OBM, OO, and OAO revised and edited the manuscript and supervised the work; OO also contributed to data collection. All authors read and approved the final manuscript. All authors contributed to editorial changes in the manuscript. All authors have participated sufficiently in the work and agreed to be accountable for all aspects of the work.

All participants gave their informed consent for inclusion before they participated in the study. The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki, and the protocol was approved by the Ethics Committee of Research Ethics Committee, Uniosun Teaching Hospital, Osogbo, Osun State, Nigeria (UTH/REC/2023/04/762).

Not applicable.

This research received no external funding.

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

Publisher’s Note: IMR Press stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.