1 Department of Pharmaceutical Sciences, College of Pharmacy and Health Sciences, Texas Southern University, Houston, TX 75207, USA

2 Singapore Eye Research Institute (SERI), 169856 Singapore, Singapore

3 Institute of Ophthalmology, University College London (UCL), WC1E6BT London, UK

4 Ophthalmology Innovation Center, Santen Inc., Emeryville, CA 94608, USA

§Current address: Boston Scientific Corp, Boston, MA 01752, USA

Abstract

Low retinal blood flow and/or vasospasm represent major risk factors for the development of glaucomatous optic neuropathy (GON), a potentially blinding eye disease. Bradykinin (BK), a nonapeptide, is endogenously produced and released, which can cause smooth muscles to contract and relax in different tissues depending on the physiological/pathological situation and the presence or absence of vascular tone. Several reports have shown the presence of BK receptor mRNAs, and in some cases, B1- and B2-receptor proteins, in ocular tissues, including the retina. However, the function of these receptors remains to be determined, especially in retinal blood vessels.

We pharmacologically characterized the ability of BK and any related peptide agonists to promote the contraction of isolated bovine posterior ciliary arteries (PCAs) in an organ bath setup using a cumulative compound addition and tension development recording process. Receptor-selective kinin agonists and subtype-selective BK receptor antagonists were utilized to define the possible heterogeneity in the functional BK receptors for PCAs.

All agonist kinin peptides concentration-dependently contracted the PCA rings bi-phasically over a 5-log unit range (0.1 nM–10 μM). The relative potencies (EC50 values; n = 4–5) regarding the high-affinity receptor site were: Lys–BK = 0.9 ± 0.4 nM; Des–Arg9–BK = 0.9 ± 0.4 nM; RMP-7 = 1.1 ± 0.6 nM; Met–Lys–BK = 1.3 ± 0.5 nM; Hyp3–BK = 2.7 ± 0.5 nM; BK = 3.0 ± 0.7 nM. The low-affinity receptor site activated by these peptides mostly exhibited EC50 values ranging from 0.3 μM to 3 μM. The concentration–response curves to Des–Arg9–BK (B1-selective agonist) were shifted to the left in the presence of increasing concentrations of a B1-receptor antagonist (R715: 1–10 μM; n = 3). Similarly, WIN-64338 (a B2-receptor antagonist: 1–10 μM; n = 3) moved the BK concentration–response curves to the left.

The pharmacological characteristics of BK and analog-induced contractions, and their inhibition by receptor-selective antagonists, indicated the presence of both B1- and B2-receptors, and perhaps another subtype, which mediate the PCA contractions. These results have potential implications for the involvement of heterogeneous kinin receptors, narrowing PCA diameters in vivo, restricting blood flow to the retina, causing GON, and subsequent visual impairment that can eventually cause blindness.

Keywords

- posterior ciliary artery

- blood vessel contraction

- blood flow

- oxidative stress

- bradykinin

- retina damage

- glaucomatous optic neuropathy

- glaucoma

The etiology of multifactorial blinding eye diseases grouped under glaucoma or glaucomatous optic neuropathy (GON) has numerous intraocular pressure (IOP)-dependent and IOP-independent risk factors, including IOP spikes or chronically elevated IOP and vasospasm or prolonged reduction in retinal blood flow, respectively [1, 2, 3, 4]. The net result of some or all of these deleterious events is optic nerve head (ONH) inflammation, retinal ganglion cell (RGC) apoptosis, and decreased optic nerve axonal flow of neurotrophins and mitochondria, which ultimately promote visual impairment and can cause blindness [2, 4, 5, 6]. Much research into drug and device development has led to the successful medical treatment of ocular hypertension (OHT) and open-angle glaucoma (OAG) [1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6]. However, despite recent clinical reports of vitamin B3 curbing visual field loss [7], additional therapeutics and treatment options are urgently needed to prevent and treat GON and preserve the eyesight of millions of patients afflicted with normotensive glaucoma (NTG), pseudoexfoliation glaucoma (PEXG) and angle-closure glaucoma (ACG) [1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6].

Abnormalities in retinal blood flow and, thus, reduced tissue perfusion have been linked to optic nerve damage and GON, which have lent credence to the vascular theory of GON pathogenesis where numerous vasoconstrictors, such as endothelin-1 (ET-1), FP-receptor-activating prostaglandins, serotonin (5-hydroxy tryptamine; 5-HT), and histamine, have been implicated as culprits [3, 4, 8, 9, 10, 11, 12, 13]. Even though locally synthesized and liberated decapeptides (Lys–bradykinin; Lys–BK), BK and Des–Arg9–BK, and/or those that are present in the systemic circulation, are generally considered vasodilators [14, 15, 16, 17]; moreover, their ability to contract and constrict certain blood vessels [14, 15, 16, 17] perfusing major organs is under-appreciated and less well studied. This is particularly true for the ocular circulatory system, where a robust kallikrein–kinin generation system and specific kinin receptors exist on certain ocular tissues and blood vessels [18, 19, 20].

Regarding the retinal circulatory system, although the first branch of the internal carotid artery (ophthalmic artery) is a key source of fresh blood, ciliary arteries also significantly contribute to the perfusion of the retina, a high-energy and oxygen-dependent tissue. The optic disc/ONH forms the primary site where blood vessels enter and exit the retina. The posterior ciliary artery (PCA) is the major supplier of oxygenated and nutrient-filled blood in and around the ONH [21]. The PCA also supplies the retinal choroid up to the equator, the outer retina, the retinal pigment epithelium, and the medial and lateral segments of the ciliary body and iris in the anterior eye segment [21]. Therefore, occlusion or other disturbances in the PCA structure and/or circulatory system, such as vasospasm, can have serious consequences resulting in visual impairment, potentially leading to blindness [21, 22, 23, 24]. NTG-associated retinal vasculopathies [8, 9, 10, 11, 12, 13], and anterior arteritic ischemic optic neuropathy (AAION), non-arteritic anterior ischemic optic neuropathy (NAAION), and posterior arteritic ischemic optic neuropathy (PAION) [21, 22, 23] have been shown to cause serious vision loss. Although the precise etiologies of ischemic optic neuropathies remain unknown, non-clinical and clinical evidence suggest that reduced retinal perfusion in the ONH via PCAs causes ischemia, inflammation, edema, and compresses the optic nerve with resultant RGC death and eyesight deterioration [8, 9, 10, 11, 12, 13, 20, 21, 22, 23, 24].

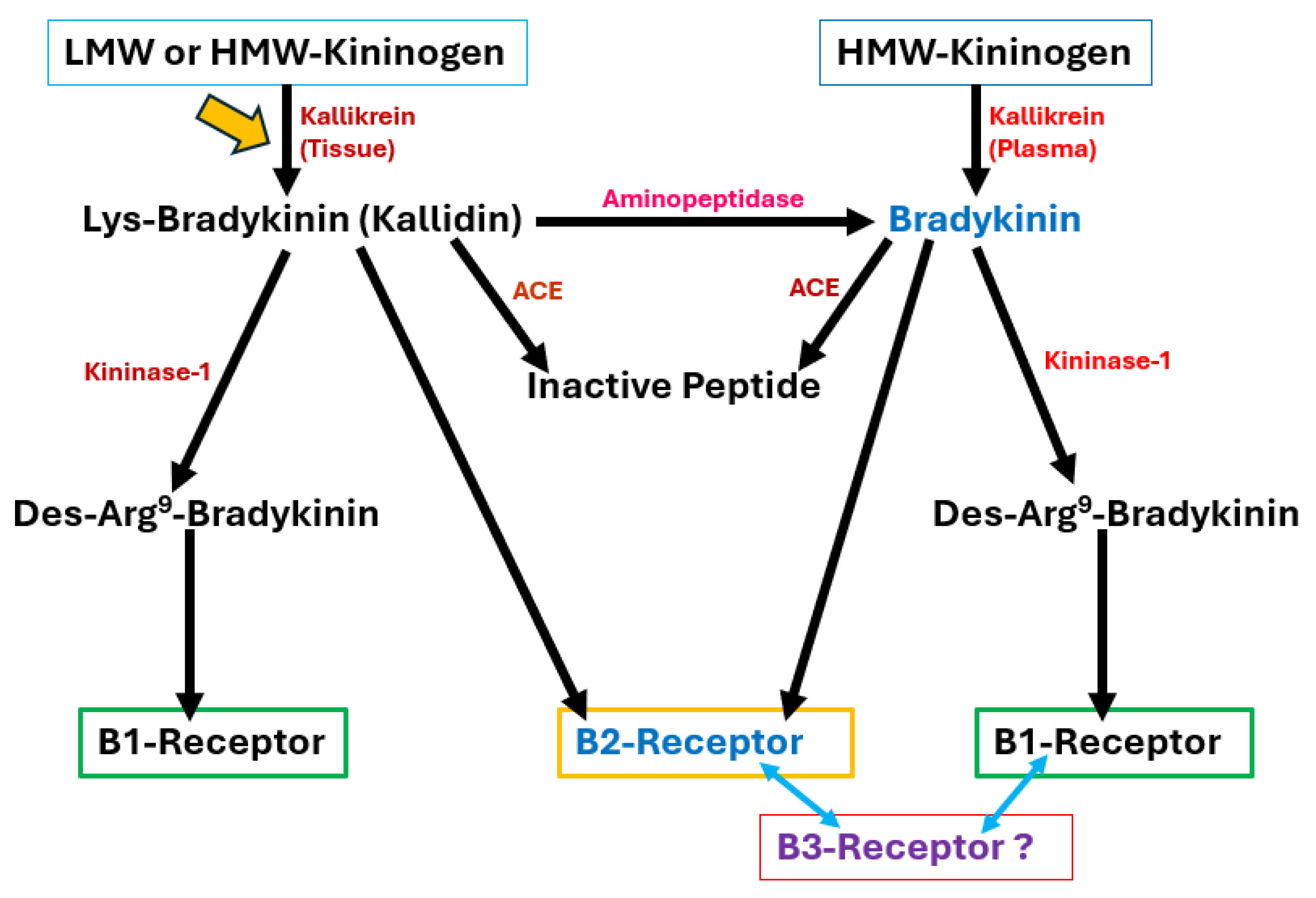

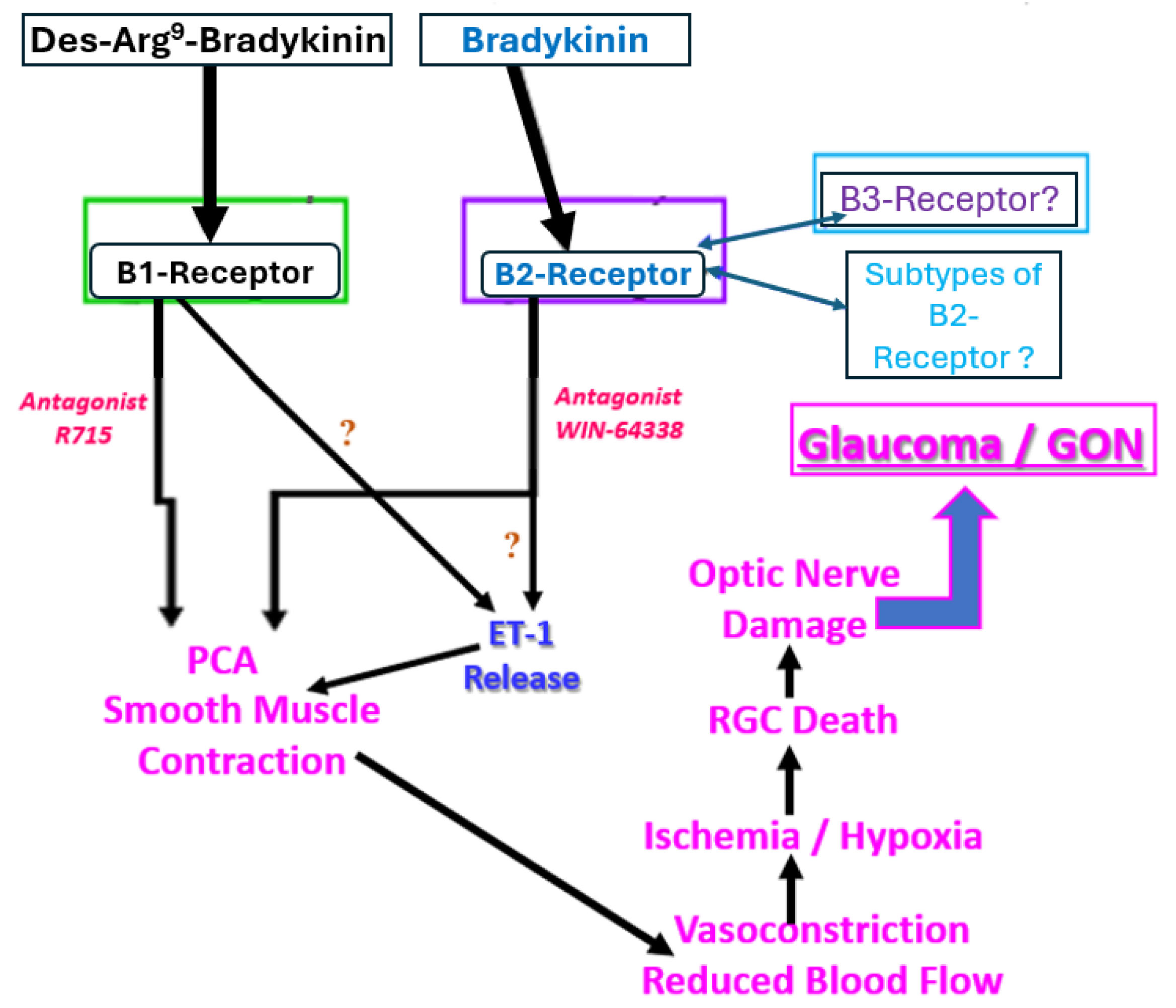

Bradykinin (BK) and its degradation product Des–Arg9–BK are relatively small peptide mediators that are locally synthesized and released to perform many different functions (Fig. 1) [14, 15, 16, 17, 18, 19, 20].

Fig. 1.

Fig. 1. The synthetic and degradative cellular machinery for the major endogenous kinins and their receptor interactions with B1- and B2-receptors. Although putative B2-receptor subtypes and a B3-receptor have been noted in the literature, these receptors have yet to be cloned. Therefore, this study aimed to invoke the tissue-based production of Lys–bradykinin from which other active peptides could be generated. However, investigating the main circulatory system source of kinins influencing ocular blood flow is also important. LMW, low molecular weight; HMW, high molecular weight; ACE, angiotensin converting enzyme; Lys, lysine; Des–Arg9–BK, where the arginine at the 9th position of bradykinin has been removed. The yellow arrow signifies that even the tissue-derived route of Lys-BK, BK and Des–Arg9–BK formation can add to the plasma-derived production of these kinins to activate both the B1- and B2-receptors within and/or around the PCA in vivo. The blue arrows denote the possibility that other sub-types of BK receptors may exist that also contribute to PCA contraction.

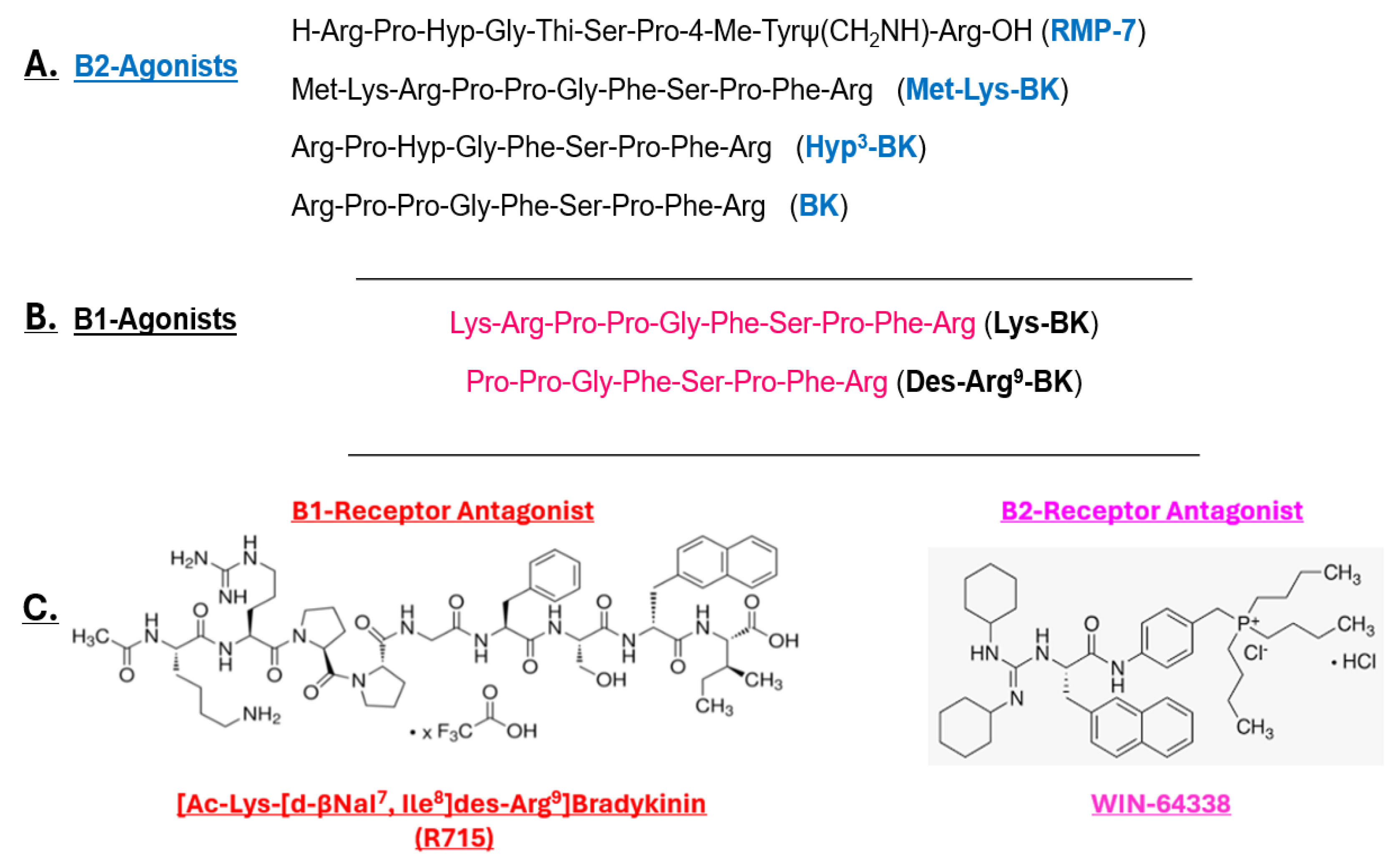

The endogenous kinin peptides shown in Fig. 1 have been reported to cause smooth muscle contraction/relaxation, induce edema and pain, lower IOP, and promote cell proliferation/angiogenesis, among others [14, 15, 16, 17, 18, 19, 24]. Des–Arg9–BK exhibits a high affinity and agonist potency at the B1-subtype kinin receptor, whereas BK has the opposite receptor selectivity, preferentially activating B2-receptors at nanomolar concentrations [14, 16, 17, 18, 19]. Additionally, several BK analogs have been synthesized to help further characterize the kinin receptor subtypes (Fig. 2) [16, 17, 18, 19, 25]. B1-receptors, normally present at relatively low concentrations, can be targeted and silenced by B1-receptor-selective antagonists (e.g., R715), but are only inducible under certain conditions [26]. Conversely, WIN-64338 is a fairly potent and selective B2-receptor antagonist (Fig. 2) [14, 16].

Fig. 2.

Fig. 2. Peptidic and non-peptidic structures of B1- and B2-receptor agonists and antagonists. Primarily, B2-receptor-selective kinin peptides are shown in (A), whereas (B) depicts B1-receptor-selective agonists (Lys–BK and Des–Arg9–BK), and (C) shows the respective B1- and B2-receptor-selective antagonists. Hyp3, signifies that the original proline amino acid has been modified to hydroxyproline; BK, bradykinin.

As outlined above, due to the strong association between poor retinal blood perfusion and NTG (and other forms of glaucoma and AAION), discovering the molecular and cellular culprits that may cause vasoconstriction of retinal blood vessels to induce GON is important. Although endothelin-1 seems to be involved [27], we believe other contractile agents, such as BK [14, 15, 16, 17], also have a role in reducing retinal circulation. Therefore, studies have aimed to pharmacologically characterize the functionally active kinin receptors involved in contracting bovine PCAs using an organ bath-based bioassay that was previously utilized to study contractile/relaxant effects of other chemical mediators in numerous tissues derived from multiple mammalian species [15, 16, 17, 20, 28, 29, 30, 31, 32, 33, 34, 35, 36].

Whole bovine eyeballs with the optic nerve and blood vessels attached were obtained from a local slaughterhouse (Fisher Ham and Meat Company, Houston, TX, USA) and transported to the laboratory on ice within 1–2 h of sacrifice. The eyeballs were from a mixture of adult male and female cattle and were subsequently placed in warm oxygenated Krebs buffer solution (pH 7.4; 37 °C) for 30 minutes to equilibrate before the posterior ciliary artery was removed. The aforementioned conditions and factors were adhered to as much as possible to ensure uniformity and consistency in the data obtained from the animal tissues. Additionally, tissues obtained from several cattle during these studies helped provide further quality control and consistency. However, it was not possible to screen the animals for systemic diseases or vascular abnormalities; thus, the data from the studies represent and define real-world cattle population variability. Nonetheless, since we tested each PCA ring for viability and responsiveness to a tissue depolarizing concentration of KCl before any test peptides were screened, this quality control measure ensured consistency amongst the many experiments conducted over several weeks.

The experimental methodology employed for the current study was essentially the same as previously described [28, 29, 30, 31], with a few minor modifications. Briefly, the medial or lateral PCAs were dissected from the optic nerve at a distance of 2 cm from the posterior aspect of the globe. After removing the fatty and connective tissues, the blood vessels were cut into rings; two vessel rings were prepared from each eyeball [30, 31]. The rings with attached endothelium were then mounted on two tungsten wires (with one wire immobilized and the other connected to a Grass FT03 transducer, Grass Instruments, Quincy, MA, USA) to measure the isometric tension under 5 g tension in 25 mL organ baths containing oxygenated Krebs solution at 37 °C; the rings were allowed to equilibrate for 45 minutes under these controlled conditions [30, 31]. The Krebs solution was composed as follows: (final concentration in mM): NaCl2 = 118; KCl = 4.8; CaCl2 = 2.5; KH2PO4 = 1.2; NaHCO3 = 25; MgSO4 = 2.0; dextrose = 10, and flurbiprofen = 0.003 (pH 7.4). Flurbiprofen was present in the buffer to eliminate the production of prostaglandins and thus remove the potential confounding effects of the latter agents. However, since the endothelium remained within the PCA rings, no attempt was made to restrict the production or release of endogenous chemicals during the experiments. Longitudinal isometric tension responses were obtained following the cumulative addition of test compounds and recorded through an FTO3 transducer (Grass Instruments, Quincy, MA, USA) [30, 31]. The results were then displayed on a Polyview computer software analyzer (CNET Global Solutions, Richardson, TX, USA), and cumulative contractile concentration–response curves were constructed using GraphPad Prism 4.0 (San Diego, CA, USA) (see below). Before adding the test compounds, the PCA strips were challenged at least once with a buffer containing a high KCl concentration to assess the functional state of the blood vessels. This solution was replaced with fresh, warm, oxygenated Krebs buffer before adding the peptide. The results are expressed as gram tension and developed as the percentage of the maximum contractile response generated by each test compound [30, 31].

Met–Lys–BK, Lys–BK, Hyp3–BK, BK, RMP-7, Des–Arg9–BK, R715, and WIN-64338 were purchased from Tocris Bioscience (Bio-Techne Corporation, Minneapolis, MN, USA) and were of the highest purity possible. Other test compounds and buffer components were obtained from Tocris or Sigma-Aldrich Inc. (St Louis, MO, USA).

The obtained contractile responses are expressed as developed milligram tension and as percentages of the maximum response of each of the compounds [30, 31, 35]. Thus, each compound served as its control. GraphPad Prism 4.0 Software was utilized to construct the peptide concentration–response curves, in the absence or presence of the respective receptor-selective antagonist compounds. Half-maximal effective contraction potencies (EC50) of each phase of the biphasic curves for the agonist responses were obtained. The mean

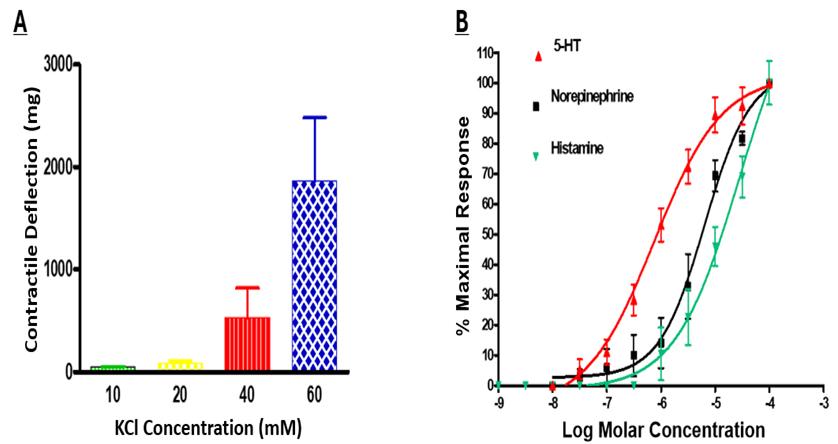

Various test chemicals were utilized to evaluate the viability and relative responsiveness of the PCA rings. Different KCl concentrations were tested to elicit the PCA rings to contract; the concentration–response data are shown in Fig. 3A.

Fig. 3.

Fig. 3. KCl-induced and various chemical mediator-induced contractions of isolated bovine PCAs. Different concentrations of extracellularly added KCl can promote contractions by the PCAs. KCl at 60 mM was routinely used to demonstrate the viability and functional activity of PCA rings in the organ bath system before any test chemicals were introduced into the organ bath. Data are presented as the mean

The 40 or 60 mM KCl concentrations were used in future experiments to analyze the responsiveness of PCAs before any of the peptides were tested. Additionally, concentration–response curves were generated in response to 5-HT, norepinephrine, and histamine to determine the responsiveness of the PCA rings to endogenous mediators that could influence vascular tone and/or contraction. All three agonists were shown to contract the PCA segments in a concentration-dependent and monophasic manner with a potency rank order of 5-HT

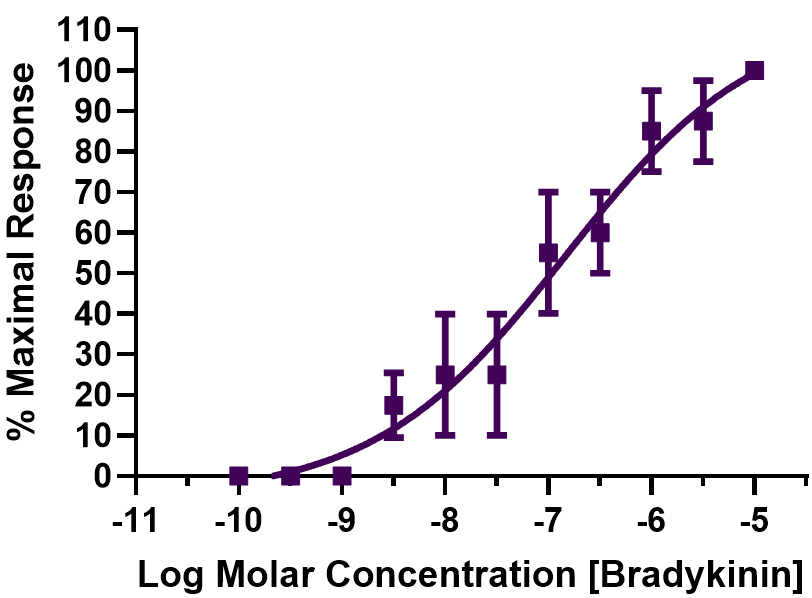

Upon testing the abilities of BK, Des–Arg9–BK, and a variety of BK analogs to influence the state of the PCA rings in the organ baths, this study noted that all compounds induced concentration-dependent contractile responses in a biphasic, positive direction manner; these were different to the profiles observed for the afore-mentioned mediator compounds (Fig. 3B). The high-affinity/potency asymptote reached by the kinin peptides was between 30 and 100 nM, while the second lower potency plateau effect was achieved at

Fig. 4.

Fig. 4. Concentration-dependent contraction of PCA rings by BK. Data from four independent experiments are shown (mean

Fig. 5.

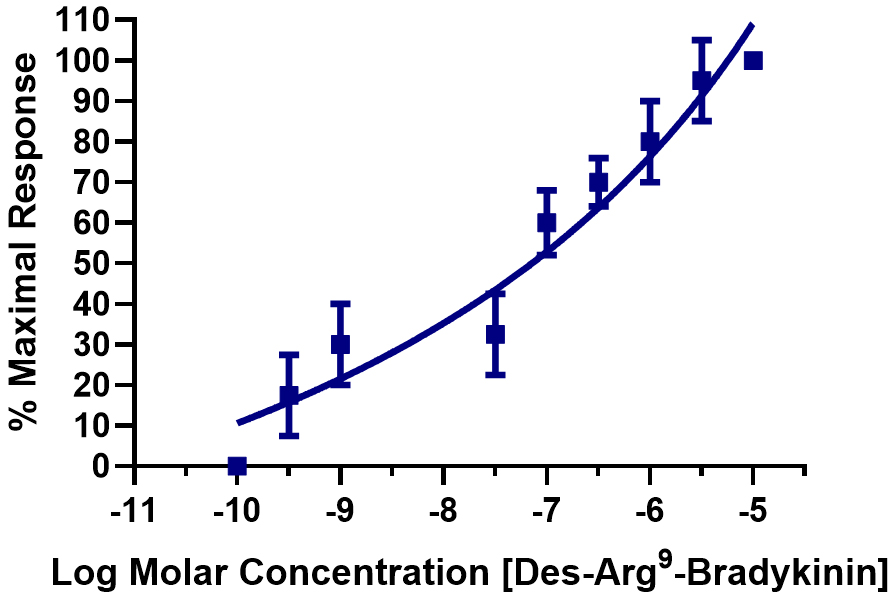

Fig. 5. Concentration–response curve for Des–Arg9–BK-mediated PCA ring contractions. The kinin contractions that induced contractions in the PCA segments were determined over 5-log units of the peptide, and the mean

Fig. 6.

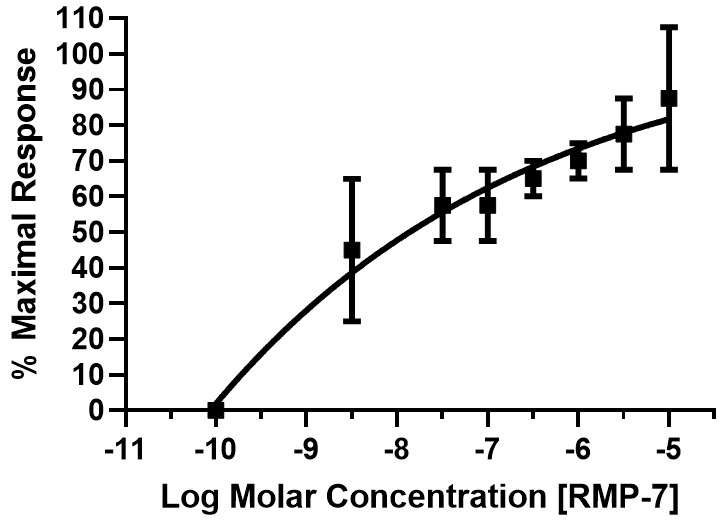

Fig. 6. Concentration–response curve for RMP-7-mediated PCA ring contractions. Multiple peptide concentrations (over 5-log units) were tested, and the cumulative data (mean

| Bradykinin and analogs | Max. tension generated (gm tension) in PCA rings | Agonist potency (EC50) of kinin peptides | |

| At high affinity and potency phase-1 receptor binding site (nM) | At low affinity and potency phase-2 receptor binding site (nM) | ||

| Lys–BK | 0.12 | 0.9 | 300 |

| Des–Arg9–BK | 0.05 | 0.9 | 278 |

| RMP-7 | 0.04 | 1.1 | 3012 |

| Met–Lys–BK | 0.07 | 1.3 | 1030 |

| Hyp3–BK | 0.03 | 2.7 | 36 |

| Bradykinin (BK) | 0.08 | 3.0 | 305 |

These data were obtained from 4–5 experiments and represent the mean

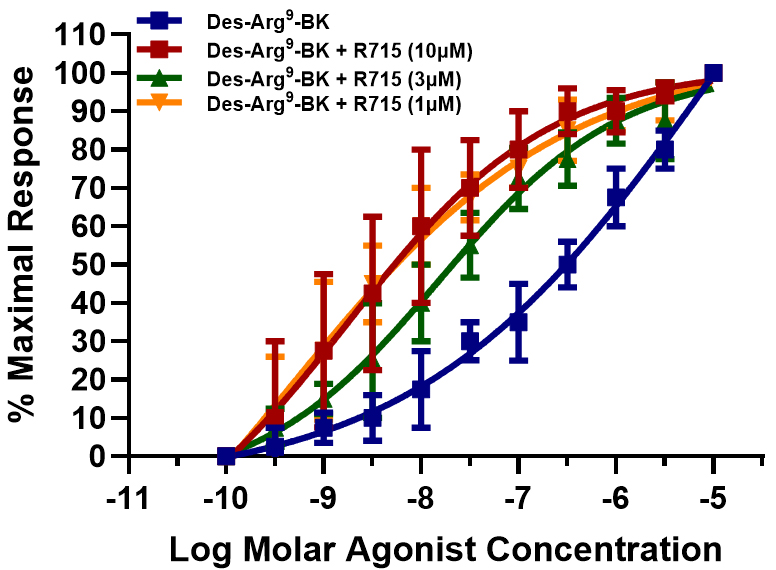

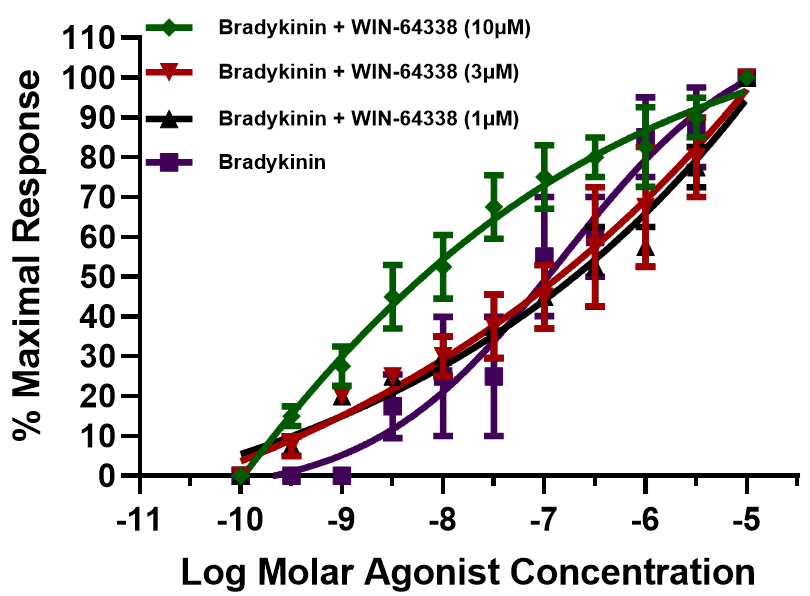

To further define the pharmacology of the receptors mediating PCA contractions, receptor-selective antagonists were used to block B1- and B2-receptors. The activities of Des–Arg9–BK and BK in the PCA contractile assay system were studied. As shown in Fig. 7, blocking the B1-receptor with increasing concentrations of R715 shifted the contraction–response curves for Des–Arg9–BK to the left of the concentration–response curve generated for this agonist alone. The PCA rings also exhibited the same contractile behavior when the B2-receptor was blocked with differing WIN-64338 concentrations, a B2-antagonist, and the concentration-dependent contractile effects of BK were investigated (Fig. 8).

Fig. 7.

Fig. 7. Effect of B1-receptor antagonist, R715, on the concentration–response of the PCA ring contractions to Des–Arg9–BK. Concentration–response curves were constructed for PCA contractions induced by the B1-receptor-selective agonist, Des–Arg9–BK, in the absence and presence of increased R715 concentrations, a B1-selective antagonist. Data are presented as the mean

Fig. 8.

Fig. 8. Effects of the B2-receptor antagonist, WIN-64338, on the concentration–responses of the PCA ring contractions to BK. Concentration–response curves were constructed for PCA contractions induced by the B2-receptor-selective agonist, BK, in the absence and presence of increased WIN-64338 concentrations, a B2-selective antagonist. Data are shown as the mean

It has been well documented that due to the unique composition and arrangements of the cellular and tissue structural elements in blood vessels and their respective innervation (or lack thereof), veins and arteries in different vascular beds respond heterogeneously to endogenous and exogenous chemicals and pharmacological compounds [15, 16, 17, 20, 25, 26, 28]. Furthermore, several differences exist in the relative sensitivity of vascular elements to contractile/relaxant compounds, often depending on the assay conditions, vein/artery/capillary diameter, source and type of tissue, and species from which the blood vessels were derived [15, 16, 17, 20, 25, 26, 28]. Although much research has been reported for systemic circulatory blood vessels [15, 16, 17], there remains a relative paucity of similar studies encompassing retinal microcirculation and the physio/pathological responses of retinal and optic nerve-associated veins and arteries. This study revealed unique contractile responses by PCA rings to a variety of test agents ranging from different KCl concentrations to specific and diverse agonist blood-borne mediator compounds (Fig. 3A,B), alongside BK and its analogs (Figs. 2,3,4,5,6). Notably, the kinin peptides caused biphasic contractile responses (Figs. 4,5,6), whereas 5-HT, norepinephrine, and histamine-induced contractions in a monophasic manner (Fig. 3B), occurred most likely through 5-HT2, alpha-1/2, and H1-receptors [20, 31], respectively. These distinguishing agonistic features were further evidenced by the observations that the concentration–response curves to the afore-mentioned non-peptidic compounds were relatively steep (Fig. 3B). In contrast, the kinins produced quite shallow concentration-dependent contractile response curves (Figs. 4,5,6). The characteristics of the latter findings strongly suggest that multiple kinin receptors are involved in the contraction process in the PCA rings, similar to previous observations in various tissues of different species [14, 15, 16, 17, 32, 33, 35]. Indeed, the use of receptor-selective agonists (e.g., Des–Arg9–BK for B1-receptors), and BK, Met–Lys–BK, RMP-7 (selective for B2-receptors [14, 16, 19, 25]) confirmed this designation. Further pharmacological evidence was obtained using kinin receptor-selective antagonists that supported these conclusions. Thus, when the B1-antagonist R715 [26] completely blocked the agonistic actions of Des–Arg9–BK at the B1-receptors, the PCA rings still contracted in a concentration-dependent manner; however, this now occurred via B2-receptor activation. Consequently, the concentration curves to Des–Arg9–BK (in the presence of R715; 1–10 µM) became steeper and appeared monophasic, indicating that a single population of kinin receptors was stimulated, most likely the B2-receptors, with nanomolar potency (Fig. 7). Following these observations, we hypothesized a converse receptor engagement when the B2-receptors were blocked by WIN-64338 (e.g., at 10 µM [27]). Indeed, this was the case (Fig. 8). The BK activity was mediated with a nanomolar potency via the B1-receptors, indicated by the monophasic nature of the response curves (Fig. 8). The collective agonist and antagonist profiles of kinin-induced PCA contractions relate to the presence of functionally active heterogeneous B1- and B2-receptors in this retinal blood vessel. Similar kinin receptor multiplicity and, hence, a positive profile biphasic concentration response to BK and its analogs have been reported in the dog saphenous vein [34], for rabbit colon and trachea [32, 33], and recently in bovine ciliary muscles [35]. Further, similar agonist potency values to those discovered for the bovine PCA under similar experimental conditions (Table 1 and its legend) were noted, whereby a prostaglandin synthesis inhibitor was included in the organ bath buffer during the tissue contraction studies to eliminate the production of endogenous prostaglandins and complicating matters. Contractile actions by BK- and BK-related kinins have also been reported in human umbilical arteries, rabbit aorta, rat liver veins, and feline pulmonary bed and numerous human and other species tissues [14, 15, 16, 17], alongside the porcine interlobular renal artery [36]. Agonist and antagonist potency differences have underscored species and tissue differences, indicative of further subtypes of kinin receptors.

In some ways, the shift to the left in the BK- and Des–Arg9–BK-induced contractile responses in the presence of their respective receptor-selective antagonists in the PCA preparations represents unique and novel findings. Pharmacological principles suggest that such features indicate at least three possibilities [37, 38]. Firstly, antagonists blocking the currently defined kinin receptors revealed a previously undefined kinin receptor subtype that mediates contractions of this blood vessel despite the B1- and B2-receptors being blocked by high concentrations of their cognate antagonists. Secondly, if the currently utilized antagonists act as neutral antagonists, and BK and Des–Arg9–BK behave as inverse agonists in the PCA rings, then the concentration–response curves can be anticipated to exhibit a shift to the left by these peptides under antagonist influence, as has been reported for other receptor systems [37, 38]. The third explanation for the unique observations in the PCA ring contractile process implicates potential negative cooperation by receptor dimer proteins (autologous or heterologous) and sufficient receptor reserves to permit agonist-stimulated contractions even in the presence of high micromolar concentrations of the respective kinin antagonists. Such features have been previously reported for cannabinoid receptors, neutral antagonists, and inverse agonistic characteristics of certain compounds [37, 38]. However, regarding additional kinin receptor subtypes, although a B3-receptor has been invoked to explain potentially unique features of certain rabbit tissues responding to BK [32, 33], such a receptor has yet to be cloned, and may represent a different state or conformation of the B2-receptor. Based on radioligand binding studies and later on functional tissue contraction studies, Regoli et al. [16] and Rhaleb et al. [17] proposed the existence of B2A and B2B receptor subtypes. Another possibility is the potential presence and interaction of kinins with an alternate BK receptor (AltB2R) recently described in certain peripheral tissues [39]. The BDKRB2 gene is a dual-coding gene that encodes the B2- and AltB2-receptor, with the AltB2R behaving as an enhancer of the B2-receptor-mediated signal transduction via cytoplasmic interactions but not via the ligand binding site in the B2-receptor located in the cell plasma membranes [39]. Interestingly, other receptor forms, such as nuclear BK-receptors [24, 25] and protein dimers composed of B2-receptors, angiotensin-II receptors, and other receptor heterodimers, have also been reported [24, 25]. Whether the AltB2R, B3-receptor, nuclear BK receptors, and/or dimers or heterodimers exist in the PCA, or other retinal blood vessels, and modulate the kinin-mediated vasoconstriction of retinal microvasculature remains to be determined. Lastly, the current observations may be related to a combination of non-competitive antagonism, allosteric modulation, or the release of other chemicals from the tissues that affect the PCA ring reactivity. These elements require further investigation in future experiments.

From a pathological perspective, the latter findings support the clinical observation of vasoconstriction and reduced retinal blood flow, which initiates the ischemia/hypoxia conditions that underlie spontaneous AAION, NAAION, PAION [21, 22, 23], retinal vein occlusion, and/or pathogenesis of chronic glaucoma and GON [9, 10, 11, 22]. The retinal vascular abnormalities caused by vasoconstriction of retinal arteries also support the development of normotensive glaucoma, where ocular hypertension is not a risk factor [9, 10, 11]. Thus, there is the possibility that under these pathological conditions, endogenous kinins derived from the blood vessel or the surrounding retinal tissue(s) are locally released to contract retinal blood vessels and thus exert deleterious effects on the retinal structure and function. In this regard, although this study has demonstrated that the direct actions of endogenous kinins on B1- and B2-receptors cause PCA contractions, there also exists the possibility that other intermediary chemicals, such as the most potent vasoconstrictor agent, endothelin-1 (ET-1), may be released following kinin receptor activation. Indeed, this alternative scenario has been reported in bovine glomerular capillary endothelial cells [40, 41], endometriotic stromal cells [42], and melanoma cells [43]. Further, since sub-nanomolar ET-1 concentrations can also promote the contraction of coronary arteries [44, 45], airways smooth muscle [45], and ciliary arteries leading to vasoconstriction and significantly reduced ophthalmic microcirculation [46], the kinin-receptor-induced ET-1 release may be an unidentified culprit mechanism responsible for vasoconstriction of retinal blood vessels. Whether such a phenomenon occurs in vitro (and/or in vivo) in retinal blood vessels remains to be determined. However, evidence exists regarding such a possibility in the mouse retinal vasculature, where ET-1 and its receptors may be upregulated to cause RGC death [47]. Moreover, endothelial cell injury induces ET-1 release [44, 48, 49], which may cooperatively interact with BK and other vasoconstrictor mediators to affect vasoconstriction, especially when the vascular endothelium is damaged due to disease and an effective counter-acting vasodilator, such as nitric oxide (NO), is reduced or absent [8, 10, 13, 21]. The involvement of endogenous ET-1 in the pathogenesis of progressive open-angle glaucoma [50] and normotensive glaucoma [27] has already received clinical support, and available data indicate powerful contractions of retinal arteries by ET-1 [20, 46]. A mechanistic overview of how BK and its analogs may directly and/or indirectly promote the PCA and other retinal blood vessels to contract, and how the resultant reduction in retinal blood flow, especially at the ONH, can lead to ischemia/hypoxia with eventual GON development and progression to vision loss is depicted in Fig. 9. This schematic aims to also account for the possible existence of types and subtypes of BK- and related peptide-accepting ligand binding sites that may be involved in the multiphasic contractions observed in the PCA preparations studied in vitro. Whether such entities prevail in vivo remains to be ascertained.

Fig. 9.

Fig. 9. The involvement of pharmacologically defined functionally active B1 and B2 BK receptors in the direct or indirect induction of PCA smooth muscle contractions. The consequences of such contractile processes mediated by kinin receptors are also illustrated to demonstrate how normotension glaucomatous damage can lead to vision loss downstream from the kinin receptor activation at the retinal blood vessel level. The question marks indicate potential interactions and pathways that need further confirmation for bovine PCAs but offer plausible indirect mechanisms of action of kinins based on data from other cells and tissues. GON, glaucomatous optic neuropathy; RGC, retinal ganglion cell. The large blue arrow indicates the final outcome of B1- and/or B2-receptor-mediated PCA contraction, namely glaucoma and GON.

A range of receptor-selective kinin agonist peptides promoted the biphasic contractions of bovine PCA rings, indicating the existence of a heterogeneous population of kinin receptors. In the presence of receptor-selective kinin antagonists, the biphasic concentration–response curves were rendered monophasic, thereby confirming the presence of functionally active B1- and B2-receptors involved in the contractile process. Although direct receptor-mediated vasoconstriction of PCA appeared likely, a possibility exists that other forms of kinin receptors (AltBR2; B3-receptor; intracellular receptors; dimers; heterodimers) are also responsible for these PCA contractions. Similarly, the BK-receptor-mediated release of other endogenous compounds, such as ET-1, 5-HT, epinephrine, or even histamine, may be partially responsible for the PCA contractions, and potential additive effects may also occur. Since such vasoconstriction in vivo causes oxidative stress [4, 8, 9, 10], local inflammation [1, 2, 3, 4, 51, 52], and can uncouple NO production for homeostatic purposes [53, 54, 55], further damage to the inner retinal neurons (RGCs) and their axons can ensue, thereby causing vision loss [1, 2, 6]. Due to the importance of sustained retinal blood flow to nourish and preserve the millions of neurons, Muller glia, retinal pigmented epithelial and other cells, and rods and cone photoreceptors, the facile ability of retinal blood vessels to contract and relax in response to changing conditions in the absence or presence of local mediators is critical for preserving good eyesight. Hence, continued studies directed at better understanding the physiopathology and regulation of retinal microcirculation and its modulation are warranted to prevent visual impairment in patients suffering from different forms of eye diseases involving dysregulated or damaged retinal veins, arteries, and microcapillaries [3, 4, 8, 9, 10, 11, 12, 13, 24]. Therefore, the use of antioxidants and vasodilators to mitigate such damage appears to be a useful strategy for reducing the negative impact of retinal arterial or venous constriction induced by endogenous kinins and other vasoconstrictor agents in various eye diseases involving dysregulated retinal blood flow [6, 10, 22, 24, 55]. Hence, from a clinical perspective, drugs that would prevent BK-induced vasoconstriction would be expected to be beneficial in enhancing retinal blood flow and reducing the severity and longevity of ensuing oxidative stress [56] and demise of RGCs by endogenously released kinins in and around retinal arteries. Likewise, the discovery of drugs that can inhibit the generation and release of ET-1 and those that can block ET-1 receptors and prevent the release of BK would be useful in treating OHT and GON.

5-HT, 5-hydroxy trytamine (serotonin); AAION, anterior arthritic ischemic optic neuropathy; AltB2R, alternate BK receptor; BK, bradykinin; ET-1, endothelin-1; GON, glaucomatous optic neuropathy; ION, ischemic optic neuropathy; IOP, intraocular pressure; NO, nitric oxide; OHN, optic nerve head; PAION, posterior arthritic ischemic optic neuropathy; PCA, posterior ciliary artery; RGC, retinal ganglion cell.

All relevant data and information supporting this manuscript are included within the article in the Materials and Methods and Results sections (including Figures and Table). Additional data or materials are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

NAS, SEO, and YFNM designed the research study. MKC, AO and SDC performed the research, analyzed the data, generated the Figures and Table, and performed appropriate literature searches for the bibliography. NAS, SEO, YFNM and SDC wrote and/or edited the manuscript. All authors contributed to and approved the final manuscript. All authors contributed to editorial changes in the manuscript. All authors have participated sufficiently in the work and agreed to be accountable for all aspects of the work.

This study used bovine eyeballs collected from a local abattoir with consent for scientific research. In accordance with local regulations and institutional policy, research involving animal tissues obtained as by-products from licensed slaughterhouses is exempt from ethical approval. A formal exemption was granted by the Ethics Committee of Texas Southern University (TSU). All procedures were conducted in compliance with relevant ethical standards, including the Animal Welfare Act and the Animal Protection Act.

Authors are grateful for the support and encouragement received from internal and external mentors to conduct ocular research in the department of Pharmaceutical Sciences, College of Pharmacy and Health Sciences at TSU.

This research was funded by internal grants from Texas Southern University.

The authors declare no conflict of interest. The only aim of the reported studies is to share research results and to encourage other scientists to conduct other relevant basic and applied research to help find suitable treatments for various ocular diseases. The latter encompass glaucoma, GON, diabetic retinopathy and age-related macular degeneration, and other retinal disorders where vascular abnormalities prevail. Madhura Kulkarni-Chitnis is affiliated with Boston Scientific Corp, Saima D. Chaudhry is affiliated with Ophthalmology Innovation Center, Santen Inc.; the judgments in data interpretation and writing were not influenced by this relationship.

References

Publisher’s Note: IMR Press stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.