1 Department of Food Science and Technology, National Nutrition and Food Technology Research Institute, Faculty of Nutrition Science and Food Technology, Shahid Beheshti University of Medical Sciences, 19856-75353 Tehran, Iran

Abstract

The contamination of soil with toxic heavy metals is considered a significant environmental concerns, with the problem intensifying rapidly due to shifts in industrial practices. Even in trace quantities, heavy metals and metalloids, such as chromium, lead, mercury, cadmium and arsenic, are toxic and carcinogenic, representing a significant threat to agricultural production and human health. Additionally, prolonged exposure to these heavy metals can cause adverse health effects in humans and other living organisms. Heavy metals are non-degradable and tend to accumulate in soil, meaning their removal is necessary. One of the more sophisticated techniques for the remediation of heavy metals is utilizing biological methods, which employ naturally occurring microorganisms, such as Pseudomonas. Bioremediation is a superior method for the elimination of heavy metals in comparison to other approaches due to its environmentally benign nature, economic viability, and minimal labor and effort requirements, bioremediation is a superior method for the elimination of heavy metals in comparison to other approaches. Pseudomonas species can absorb heavy metals from soil and utilize these toxic contaminants in their metabolic processes, or transforming them into less or non-toxic forms. This review is focused on the studies that used the Pseudomonas genus is utilized for heavy metal bioremediation in contaminated soil. Notably, applying this strategy as a sustainable environmental technology in the near future has shown synergistic benefits with marked-fold increases in removing heavy metals from soil.

Keywords

- environmental pollution

- biomass

- biosorption

- bioaccumulation

- resistance

Heavy metal contamination in soil is becoming a crucial problem due to its toxicity and persistence in the environment [1]. Their presence in soil may have natural causes or they may be introduced to soil by human activities. Domestic waste, improper disposal of electronic waste, sewage sludge, vehicle emissions, waste treatment plants, various industrial processes, and agricultural fields are some of the human activities that lead to the entrance and accumulation of heavy metals in soil [2]. These non-biodegradable, highly toxic, and persistent elements usually are characterized by their bioaccumulation in the food chains [1]. Soil contamination by heavy metals threatens the ecosystem and human health by affecting the food chain safety, food quality and characteristics of agricultural lands leading to serious food security and land tenure issues [3]. It was reported that there are more than 5 million sites in the world with the soil being contaminated by various types of heavy metals with concentrations above the regulatory levels [3]. Moreover, the biochemical and physiological processes of agricultural crops are significantly altered by heavy metals accumulation. The metal contaminations decrease plant productivity, and in high concentrations, they can even lead to plant tissue necrosis. Moreover, in the next phase, through contaminated agricultural products, they enter other living organisms and highly accumulate via biomagnification which, in turn, poses serious risks for animals and humans [4].

Remediation involves several processes aiming to remove contaminants from soil, restore the environment and ultimately protect the ecosystem. A wide range of physicochemical methods, including membrane filtration, ion exchange, electrochemical treatment, reverse osmosis, chemical leaching, stabilization/solidification, evaporation, sorption and precipitation, have been employed in the past few years to remediate the contaminated soil. Nevertheless, these methods are not recognized as environmentally friendly since they generate toxic chemical sludge [5]. Instead, microbial remediation as one of the biological technologies is of much interest today owing to its high efficiency in restoring the soil by cleaning the soil from heavy metals. In the bioremediation process, specific microorganisms with high tolerance to heavy metals are exploited. They can remove heavy metals through mechanisms [6] that are based on absorption, redox transformations (in which microorganisms work as oxidizing agents), and changes in the reaction’s medium [4]. Bioremediation in general is considered as an easy-to-handle and inexpensive method besides being environmentally friendly and sustainable. Nevertheless, its major drawback is its slow rate of the process because the contact time has an important effect on the efficiency of the bioremoval [2].

Various types of microorganisms, including bacteria, algae and fungi, were employed to bioremediate the polluted soil from heavy metals in recent years. These biological tools work based on the evolution of various resistance mechanisms, including biomineralization, bioaccumulation, biosorption and biotransformation; with which they can adjust to different toxic metals in the environment [5]. According to Zoghi et al. [7], in bioremediation, either living or dead cells of microorganisms can be used via biosorption and bioaccumulation, respectively, to be able to get rid of heavy metals. Biosorption works as a reversible energy-independent bioprocess with no need for respiration. On the contrary, bioaccumulation is an energy-dependent and active bioprocess requiring respiration [8]. A vast range of bacteria is capable of bioremediation, including Microbacterium, Ochrobactrum, Aeromonas Enterobacter, Azospirillum, Bacillus, Pseudomonas and Rhizobium [9]. According to a report by Fakhar et al. [10], certain genera of bacteria, namely Bacillus and Pseudomonas, are among the most common types of bioremediating bacteria in soils contaminated by heavy metals.

One should note that inoculation of selected microorganisms without a proper formulation may lead to the failure of the whole process. This is due to the fact that soil is an unpredictable environment and without certain considerations, inoculate population will rapidly decrease. Providing a suitable microenvironment can enhance the bacterial cell condition and leads to a better retention of the microorganism [11]. This article reviews the previous literature that utilized the Pseudomonas genus for heavy metal bioremediation in contaminated soil.

As a Gram-negative bacteria, Pseudomonas strains (0.5 to 3 µm rod measuring) are mostly motile and can grow in both soil and water and surfaces in contact with them. Despite its respiratory metabolism, it can grow in the presence of NO3 when no oxygen is present and can survive with minimal nutrition [12]. Pseudomonas is frequently reported to be resistant to heavy metals, antibiotics, organic solvents, and detergents [8]. This strain is frequently used for bioremediation in contaminated soils owing to their metal-chelating siderophores as well as surface-active extracellular polymeric substances (EPS). Being ubiquitous in activated sludge and industrial waste, Pseudomonas species are regarded as one of the most common species to clean soil from heavy metal contamination [13]. This bacterial strain has a metal tolerance via molecular mechanisms by having resistant genes. Bacterial strains resistant to heavy metals are capable of growth when exposed to high concentrations and have the potential for use in the bioremediation of soils with elevated heavy metal content. Being found in water and soil of deserts, grassland, forests, and agriculture, as well as in river ecosystems, plants, sewage, hospitals, and metal-contaminated sites, P. aeruginosa has the metabolic adaptability that enables it to clean up various substances from phenol contaminants to soil spills [8]. Moreover, it has a good tolerance towards antibiotics, salinity, and chromate when tested in tannery effluent [6].

Soil biology is one of the most important factors affecting soil health, soil quality, and sustainable agriculture. Industrial activities such as mining, cause detrimental alteration to the environment, ecosystem, and human health. These effects include the depletion of biodiversity and the accretion of pollutants in the ecosystem. Thus, toxic materials that are mostly left with no further treatments after mining are one of the major causes of soil metalloid pollution. As a result, high concentrations of heavy metals abandoned in mine wastes lead to the massive destruction of soil and natural water resources [14].

As defined, metals with atomic numbers and elemental densities greater than 20 and 5 g/cm3, respectively, are considered as heavy metals [15]. Their toxicity leads to a slower breakdown of organic litter, causing uneven litter deposits on the soil surface. Additionally, heavy metals may inhibit soil enzymatic activities, such as alkaline phosphatase, arylsulfatase,

As a naturally abundant element in the Earth’s crust, As can be found in two organic and inorganic forms. Inorganic arsenic is considered as highly toxic (mostly found in water) while organic forms (mostly found in seafood) are considered less harmful. In well-drained surface soils, As is mainly found as As5+ (arsenate), while As3+ (arsenite) species are more found in reducing environments, muddy lands, and soils [3]. The latter is more toxic due to reactions with sulfhydryl residues in proteins and inhibiting essential biochemical processes in living organisms which includes bacteria [9].

Another heavy metal that causes severe environmental issues is Pb. Lead contamination degrades ecosystems and disrupts natural biodiversity. Lead is notably persistent, with the ability to remain in the soil for up to 5000 years, and has a high average biological half-life. Moreover, it can accumulate in plants and human bodies, leading to serious and irreversible damage [20].

Another heavy metal that is problematic in the environment is Cd. It is known to form stable dissolved complexes with inorganic and organic ligands, affecting its adsorption and precipitation. It is extensively used in industries, such as pulp and paper, paints, electroplating, chloralkali production, copper alloys, mining, alkaline batteries, zinc refining and fertilizer production [8]. Also, Cd selenide is a potential semiconductor that is widely utilized in the manufacturing of optoelectronic devices [21]. Moreover, Cd can gradually destroy enzyme functions and suppress DNA-mediated gene transfer in microorganisms. Mining, agriculture, and other industries are some of the human-caused sources of Cd occurrence [3].

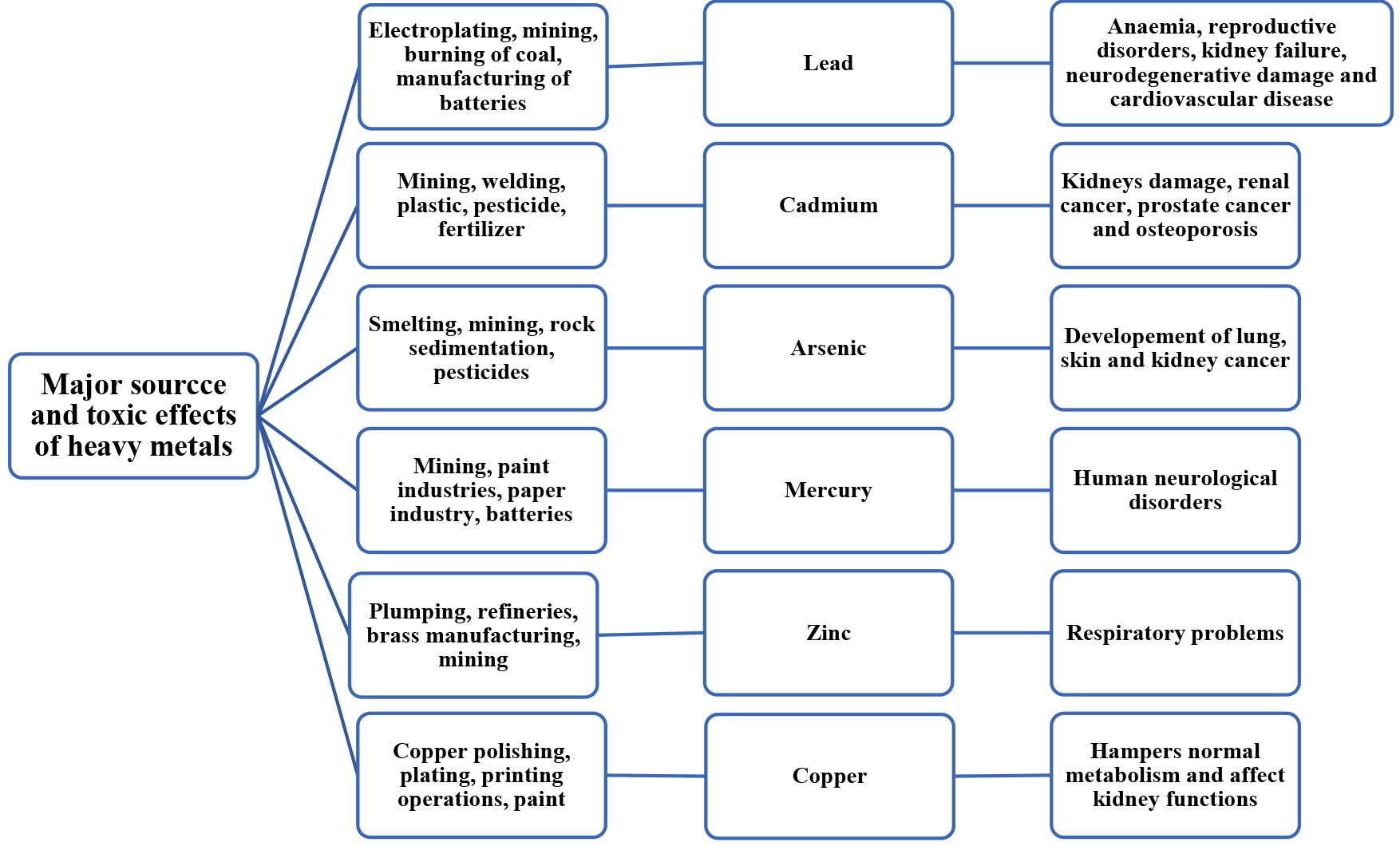

Cadmium accumulation in living organisms such as plants adversely affects their structure, physiology, and biochemistry. These effects include altering mineral nutrient absorption and photosynthesis, altering antioxidant and carbohydrate metabolism and decreasing crop and agricultural productivity [8]. As specified by standards of the Environmental Protection Agency (EPA), the maximum permissible concentration for Pb, As, Hg, Cd, and Cr should not exceed 0.015, 0.01, 0.002, 0.005, and 0.1 mg/L, respectively [22]. The Major source and toxicity of various heavy metals to humans is illustrated in Fig. 1.

Fig. 1.

Fig. 1. Different heavy metals and their Major source and toxicity on human beings.

Pseudomonas genus is a widely studied species to bioremediate soil and clean it from heavy metals. In Table 1 (Ref. [1, 6, 11, 23, 24, 25, 26, 27, 28, 29, 30, 31, 32, 33, 34, 35, 36, 37]), recent studies on different species capable of bioremediation are summarized. One of the most frequently used species is P. aeruginosa which showed a promising tolerance towards polluted environments by heavy metals owing to its biosorption attributes. Furthermore, there are some reports that show this species can employ some enzymatic pathways, such as oxidization pathway, to convert pollutant materials into non-toxic compounds [8, 23]. In this regard, three species of P. aeruginosa, P. nitroreducens, and P. alcaligenes were examined and showed to be able to tolerate high concentrations of Pb; however, concentrations higher than 50 mg/mL of Pb with an exposure time of 40 hours significantly affected the Pseudomonas species isolates [24]. In biosorption assays measuring the percentage of Pb removal, no significant differences among the Pseudomonas species were observed despite varying exposure times. The process was generally more effective with live biomass.

| Pseudomonas genus | Heavy metal | Mechanism of removal | Reduction rate | Reference |

| Pseudomonas sp. | Cu, Cd, Pb | Biosorption | 70.4%, 93.5%, 97.8% | [25] |

| Pseudomonas sp. | As, Cd, Hg | Biosorption | 34%, 55%, 53% | [26] |

| Pseudomonas sp. | Ni, Zn | Biosorption | 52.9% | [27] |

| P. azotoformans JAW1 | Cd | Biosorption | 98.57% | [28] |

| P. azotoformans JAW1 | Pb | Biosorption | 78.23% | [29] |

| P. aeruginosa FZ-2 | Hg | Biosorption | 99.7% | [30] |

| P. aeruginosa RW9 | Cr | Bio-accumulation | 90% | [31] |

| P. aeruginosa | Pb | Exopolysaccharide production and biosorption | 80% | [24] |

| P. aeruginosa | Cr, Cu, Zn | Biosorption | 41.6%, 79.1%, 52.4% | [6] |

| P. aeruginosa | Pb, Cd | Biosorption | 33.6%, 58.8% | [23] |

| P. aeruginosa | Pb, Cd | Bio-augmentation | - | [32] |

| P. aeruginosa N6P6 | Pb | Bio-transformation | 98% | [33] |

| P. putida A (ATCC 12633) | Al3+ | Biosorption | 95% | [34] |

| P. putida PT | Cd | Immobilized cells | 97.57 % | [11] |

| P. veronii 2E | Cd | Exopolysaccharide production and biosorption | 82.8% | [35] |

| P. stutzeri LBR | Pb | Exopolysaccharide production and biosorption | 58.07% | [1] |

| P. stutzeri AS22 | Pb, Co, Fe, Cu, Cd | Exopolysaccharide production and biosorption | - | [36] |

| P. stutzeri TN_AlgSyn | Cr, Pb, Co | Exopolysaccharide production and biosorption | 96% | [37] |

Pb, lead; Cd, cadmium; Hg, mercury; Cr, chromium; As, arsenic; Ni, nickel; Zn, zinc; Cu, copper; Al, aluminum; Co, cobalt; Fe, iron.

Li et al. [38] identified a strain of Pseudomonas (I3) that demonstrated better Pb uptake using live cells (49.8 mg/g of biomass) compared to dead biomass (42.37 mg/g of biomass). Similarly, Xu et al. [39] found that the maximum biosorption capacity was 92.59 mg/g for live biomass, whereas it was 63.29 mg/g for dead biomass. The key difference between these mechanisms is the reliance on cell metabolism: live biomass requires the metal to be transferred through the cell wall into the cytoplasm, implying that the cells are metabolically active. In a biosorption study, adapted cells of P. aeruginosa strain JCM 5962, as well as genetically engineered P. aeruginosa, showed the ability to remove Cd [40].

A recent study identified several strains capable of eliminating heavy metals from the test medium, including Pantoea sp., Achromobacter denitrificans, Klebsiella oxytoca, Rhizobium radiobacter, and P. fluorescens [4]. Among these, Achromobacter denitrificans, Klebsiella oxytoca, and Rhizobium radiobacter were the strongest scavengers of Pb, As, Hg, Ni, and Cd from the soil [4]. Additionally, the effectiveness of Pseudomonas species in reducing the concentrations of heavy metals, while being used in combination, was evaluated by Chidiebere et al. [12]. Their study showed that exploiting a combination of P. fluorescens, P. aeruginosa, and P. putida, isolated from rice fields, had the highest removal effect towards Cu, Pb, Ni, Cr, and Cd from contaminated soils after 48 hours of incubation.

There is no choice for microorganisms exposed to heavy metal stress conditions, but either succumb to the induced toxicity or survive by evolving resistance mechanisms. The microorganisms capable of surviving through their evolved resistance mechanisms are considered as bioremediate agents. In fact, their intrinsic structural and biochemical attributes, besides their physiological and genetic conformation, are responsible for their capability of survival in contaminated media [16]. There are five known major mechanisms for microorganisms to become invulnerable and resistant against heavy metals, i.e., active transport of metal ions, extracellular sequestration, extracellular barriers, intracellular sequestration, and reduction of heavy metal ions [41].

In the genus Pseudomonas, various resistance mechanisms against heavy metals are identified in addition to the presence of chromosome and plasmid-encoded genetic determinants. These mechanisms involve toxic metals discharge in the cell wall, alteration of toxic accumulation, and modifications to the cell wall-plasma membrane complex [8]. According to a report by Muneer [42], gene amplification by chromosomal DNA specifies the existence of resistant genes on the chromosome, with sequencing that verifies the gene responsible for heavy metal resistance (the czcA) in P. aeruginosa EP-Cd1. P. aeruginosa has shown tolerance to Pb, Zn, and Cu ions through biofilm production. Adsorption of Pb ions observed in P. aeruginosa is reported by means of exopolysaccharides (ExP) that act as barriers against heavy metals [16].

What occurs in extracellular sequestration, is that components within the periplasm or outer membrane of cells bind with metal ions to form complexes. This metal-ion complexation may lead to the formation of insoluble compounds. Cell membranes of microorganisms contain proteins and metabolic products that can form chelates with metal ions [16]. Copper-resistant P. syringae strains produce copper-inducible proteins, such as CopA and CopB (periplasmic proteins), and CopC (outer membrane protein), which bind microbial colonies to Cu ions [43]. A very similar mechanism is found in the Cu-tolerant P. pickettii strain US321. In this strain, Cu is accumulated as a complex and transferred into the cytoplasm, whereas in the sensitive strain, Cu accumulates in a highly toxic free ionic form [44]. In a report on arsenic resistance mechanisms, a whole genome analysis of P. putida was conducted. This analysis revealed that 61 open reading frames (ORFs) were associated with metal resistance, indicating the presence of multiple metal resistance mechanisms. Among these, seven ORFs were specified as critically important, including two arsenic resistance systems, two cadA genes, two operons for Cu chelation, and one for chromate ion resistance. Additionally, some proteins were found to be resistant to multiple metals [45].

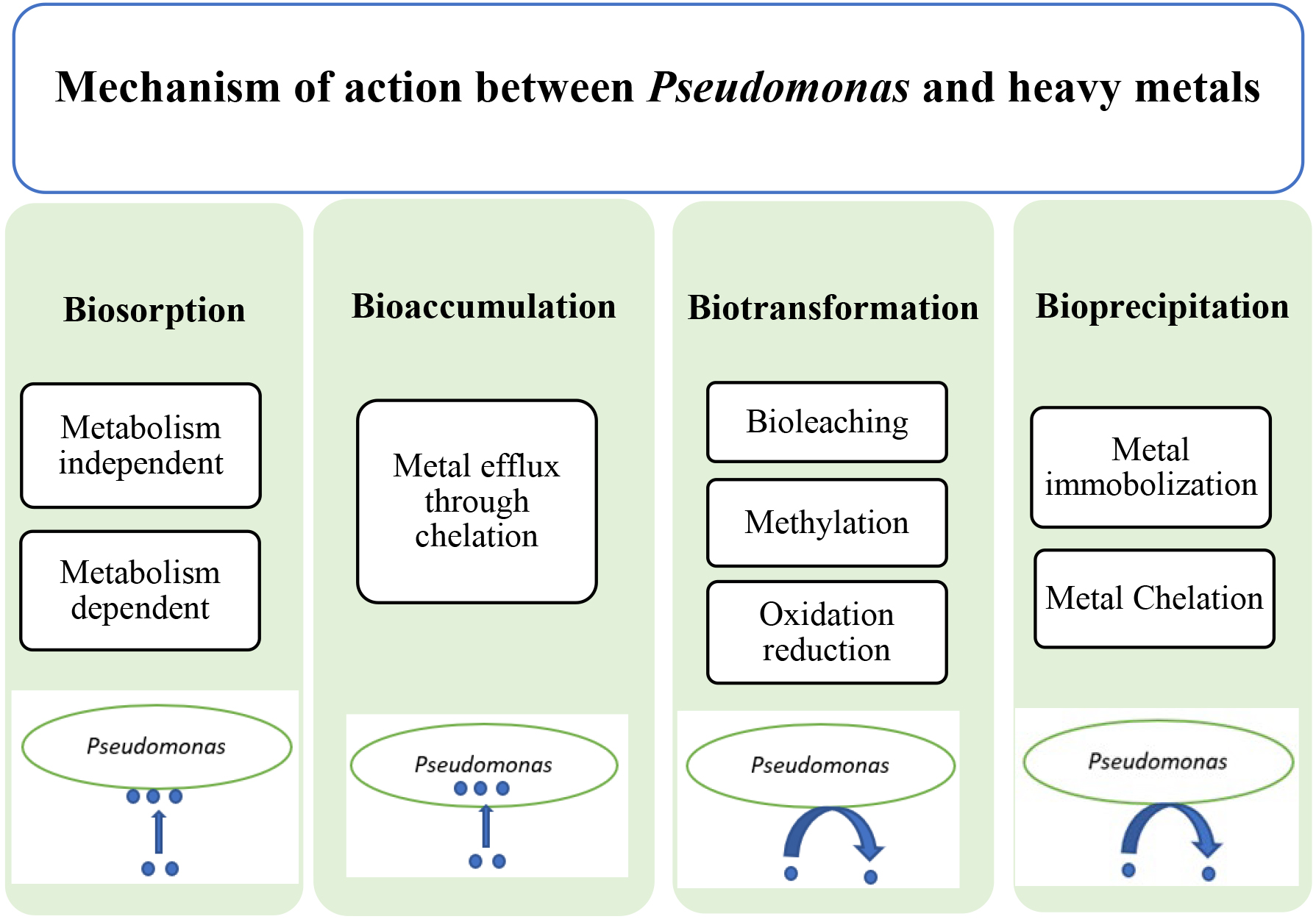

The mechanisms behind the bioremediation of heavy metals by pseudomonas are mainly shown in Fig. 2.

Fig. 2.

Fig. 2. Diagram showing different mechanisms of bioremediation action between Pseudomonas and heavy metals.

Biosorption, whether involving dead or live bacteria, is a surface process where heavy metals are adsorbed onto the cellular surface. This passive uptake occurs independently of the bacterial metabolic cycle [46]. Of all organisms, bacteria are known as the most effective biosorbent, perhaps owing to the abundance of chemosorption sites in their cell walls, e.g., teichoic acid as well as their considerably large surface-to-volume ratio. Metal ion biosorption primarily occurs through surface binding, as a result of the biomass ion exchange process in which protons and metal ions compete for binding sites [47]. The surface of bacterial cells, typically with a negative charge, robustly attracts heavy metals. In certain cases, the cell surface may also have a mucus or polysaccharide layer that can effectively adsorb heavy metals through physical interactions [7]. Heavy metals are passively adsorbed onto the surface without energy expenditure until equilibrium is reached. Using living biomass for sorption can be impractical because toxic metals may accumulate in cells, disrupting metabolic functions and leading to cell death. In contrast, dead biomass is not affected by toxicity, doesn’t require growth or nutrient mediums, and can adapt to varying environmental conditions [48].

The ExP produced by Pseudomonas species, particularly P. aeruginosa, is composed of heteropolysaccharides, including alginates, biosurfactants, and rhamnolipids [49]. ExP exhibits a robust metal-binding capacity, strongly halting complex heavy metals from engaging in bacterial intracellular environments. This attribute helps protect bacteria from heavy metal toxicity [41]. Nevertheless, other reports found the production of these compounds promising for removing heavy metals from contaminated soil through which the ExP matrix interacts with aerobic sludge or anaerobic granules [24]. In fact, heavy metals form a better complex when extracellular polymers and charged functional groups are present in the environment, which in turn, causes their lower remainder in the soil [22]. Another recent study [50] highlighted the importance of carboxyl functional groups in alginate to the adsorption process as they primarily form complexes with Cu in EPS of P. putida.

The exposure of P. aeruginosa spp. to salts of metal fatty acids containing Cd (II) stearate caused a poorly developed biofilm with the least amount of ExPs, as reported by previous research [51]. As a result, the amount of absorbed Cd (II) by the biofilm ExPs was limited to 1.1%, whereas the removed amount of Zn, Cu, and Fe (III) by the ExPs were 58%, 52%, and 48.5%, respectively. The complexation of metal ions with the carboxyl and phosphate functional groups of ExPs was revealed by Fourier-transform infrared spectroscopy (FTIR). Another research [52] underscored the essential role of ExPs in metal sequestration, noting that these biomolecules help sustain the metabolic activity of Gram-negative P. aeruginosa CPSB1 under heavy metal stress and also protect against desiccation. Therefore, exposure to 200 µg/mL of Cu (II), Cd (II), Cr (VI), Ni (II), or Pb (II) led to at least a 34% increase in ExP production by P. aeruginosa spp., compared to the untreated control.

Bioaccumulation in microorganisms involves an active metabolic process using an import-storage system, where transporter proteins facilitate the movement of metal ions through the cell membrane into the cytoplasm. This process, known as active uptake, occurs when metal ion concentrations in the biosphere exceed those in the surrounding environment [16]. Two phases are defined for heavy metal transport over the phospholipid bilayers of living cells. The first phase involves the non-metabolic adherence of heavy metals to the cell surface. In the second phase, metal ions are internalized through the cell membrane. Various mechanisms contribute to this process, including endocytosis, ion channels, carrier-mediated transport, complex permeation, and lipid permeation, all of which play roles in heavy metal bioaccumulation in bacterial membranes [53, 54].

Bacterial cells’ capability to accumulate metals intracellularly has been exploited in various applications, particularly in waste treatment. For instance, a Cd-tolerant strain of P. putida utilized low molecular weight cysteine-rich proteins to sequester Cu, Cd, and Zn ions within its cells [16]. Additionally, research by Rani and Goel [55] investigated Cd removal using P. putida spp., revealing both periplasmic and intracellular metal accumulation via transmission electron microscopy.

Biotransformation involves converting metals into different forms rather than degrading them. Efficient bioremediation can alter the physical and chemical properties of metals and transform them into either a less or more water-soluble state in which the latter is less toxic [56]. The cellular metabolic activity of the microorganism is in charge of bio-transformation mostly through redox mechanisms [57]. Metals reduction frequently happens in nature through hydrolysis, condensation, new carbon bond formation, oxidation, isomerization and functional group introduction, which, in turn, can lead to metal compound volatilization and reduce their toxicity [41].

Bacterial methylation, particularly by Pseudomonas spp., significantly contributes to metal remediation by converting heavy metals like Hg (II), As, and Pb into gaseous methylated forms through volatilization [58]. Another mechanism that can be used to remove heavy metals is bioleaching which employs microorganisms as reduction agents to remove heavy metals. For instance, using P. aeruginosa biomass with 0.1 M HCl results in up to 82% Cd (II) recovery. Similarly, using P. putida cells immobilized in a volcanic rock matrix and displaying cyanobacterial metallothioneins at pH 2.35 shows effective metal recovery [59].

A set of microbial activities that convert soluble metal ions and metalloids into insoluble forms, such as hydroxides, carbonates, phosphates, and sulfides, is called bio-precipitation [60]. These metal precipitates adhere to bacterial cells, allowing for the recovery of heavy metal ions through minor pH changes. Unlike bioaccumulation, bioprecipitation relies more on environmental changes induced by bacteria rather than metabolic activities. For instance, P. aeruginosa can facilitate the precipitation of cadmium ions.

Metal binding through precipitation happens when metal ions interact with functional groups on bacterial surfaces, leading to the formation of insoluble metal precipitates that remain attached to the microbial cells. This involves the exchange of binary metal cations with counter ions on the bacterial surface [22].

Focusing solely on selecting the right method and technique for bioremediation without considering influencing factors can limit its effectiveness. The process can be enhanced by adapting strategies to the specific conditions of the contaminated environment. One such approach is bio-stimulation, which involves elevating bacterial growth at the site by adding pH adjusters, nutrients, surfactants, and oxygen [23]. To assess whether heavy metals are stimulatory or inhibitory to bacteria, it is crucial to consider total metal ion concentration, their chemical forms and related parameters, such as redox potential. Factors like soil temperature, pH, and moisture content influence the bioavailability of heavy metals to bacteria [22].

Soil temperature, in particular, plays a key role in optimizing conditions for bacterial growth, metabolism, enzyme activity and heavy metal adsorption. Higher temperatures boost the rate of adsorption diffusion and enhance microbial activity within an optimal range, accelerating metabolism and enzyme activity to improve bioremediation [61]. In favorable conditions, both the adsorption capacity and adsorption intensity of metals generally increase with rising temperature. However, soil moisture levels can significantly impact the bioremediation process. Low soil moisture restricts microbial growth and metabolism, while excessive moisture can impede soil aeration. Typically, higher soil moisture levels facilitate more effective metal uptake by microorganisms [47].

Both bacterial activity and metal behavior are strictly affected by the pH of the soil. In fact, the enzymatic activity of bacteria directly influences the rate of heavy metal metabolism. Moreover, pH impacts the surface charge of microorganisms, thereby altering their ability to adsorb metal ions. Generally, a decrease in soil pH increases the bioavailability of metals in the soil solution. Furthermore, pH affects the hydration and mobility of various metal ions within the soil [16]. Generally, lower pH levels enhance the activity of metal cations, while higher pH levels increase the solubility of metal anions [47]. According to Wierzba [62], the removal rate of heavy metals by microorganisms increases with pH up to a certain level, beyond which further increases in pH lead to a reduction in the removal rate.

The effectiveness of soil bioremediation is highly influenced by factors, such as inoculum density, contact time, survival, colonization, competitiveness, biological activity and physical diffusion capacity [47]. Soil type plays a crucial role in determining metal bioavailability. Metal ions and pesticides are most available in loam and sandy soils, with less availability in clay loam, and the least in fine-textured clay soils. Variations in soil type can also impact how metals and pesticides interact [63]. As hydrogen ion concentrations increase, the adsorbent surface becomes more positively charged, reducing its attraction to metal cations and potentially increasing toxicity. The stability of the microbe-metal interaction is influenced by sorption sites, the microbial cell wall structure, and the ionization of chemical components on the cell wall. The outcome of the degradation process is affected by the substrate and various environmental factors [64].

The contact time between the bacteria and heavy metal affects the rate of biosorption. At the outset of the process, the affinity for binding metal ions is high due to the availability of binding sites on the bacterial surface. However, as time progresses, the affinity declines until it reaches a saturation point, which is a consequence of a reduction in the number of available binding sites. The time required to achieve maximal adsorption depends on various factors, including the type of metal ion, the type of bacterial species used, and the combination of the two [65].

The rates of bioremediation are affected by heavy metal concentration and the expression of specific enzymes by Pseudomonas species. Enhancing remediation effectiveness can be reached by adding carbon sources and increasing pH [23]. Adsorption characteristics vary among soils; for example, beach tidal soil has higher adsorption capacity compared to black soil and yellow mud [16]. Additionally, individual bioavailability of Pb2+, Cd2+, and Zn2+ is often greater than that of multiple metal ions [66]. Soil amendments can significantly improve microbial removal of heavy metals, with additive concentrations impacting leaching rates differently [67].

The use of live or dead bacteria can impact the efficiency of bioremediation. Live bacteria engage in two key processes to mitigate metal toxicity. First, they perform biosorption, a passive process where the bacterial cell wall serves as an initial barrier against metal toxicity without requiring metabolic activity. Second, metal ions can be transported into the bacterial cell interior through mechanisms, such as complex permeation, endocytosis, or ion pumps, leading to bioaccumulation. Additionally, live cells are metabolically active and can produce H+ ions, which may compete with metal ions and potentially reduce the biosorption capacity for toxic metals [24].

Recent advancements in genetic engineering indicated that genetically engineered microorganisms are often more effective than natural ones for environmental restoration, particularly in removing persistent compounds [68]. For example, genetically modified strains of P. putida and Escherichia coli M109, which carry the merA gene, have been successfully used to remove mercury from contaminated soils and sediments [69]. Additionally, the introduction of new genes into Pseudomonas cultures using the pMR68 plasmid has enhanced mercury resistance [70].

The main disadvantage of bioremediation is its prolonged timeframe, which is a notable contrast to the relatively reasonable processes of excavation and pollutant removal from the site [71]. Also, several factors could affect the efficiency of the bioremediation process and incomplete bioremoval may occur, so, the affecting factors, which are mentioned in the previous part, should always be controlled in order to achieve the optimum bioremediation. In addition, the products of biodegradation have been observed to become more toxic than the original compound on occasion. Moreover, these biological processes are highly specific. Examples of effective site factors include the presence of microbial populations, growth conditions, and the quantity of nutrients and pollutants [2]. Besides, biodegradation capacity and efficiency cannot be predicted because of dealing with a live organism [58].

It is of paramount importance to remediate soil contaminated by heavy metals. Heavy metal contamination can originate from both anthropogenic and natural sources. Significant resources were dedicated over recent decades to addressing the issue of heavy metal pollution, with the development of new strategies to remediate the problem. However, the application of bioremediation techniques remains the most favorable approach, due to the variability of bioremediation mechanisms, which makes these techniques applicable and affordable. Bioremediation is an effective method, particularly for vast, low-contaminated regions. It is also a cost-effective, readily available, environmentally safe, and highly acceptable approach. Pseudomonads sp. are of particular importance in the context of nutrient cycling and their ability to adapt rapidly to contaminated environments makes them an optimal choice for eco-friendly studies. The aforementioned information corroborates the assertion that Pseudomonas sp. is an optimal bacterium, or perhaps more accurately, an especially suitable choice for the bioremediation of heavy metals in soil. The most abundant toxic heavy metals in soil include Pb, Cd, As, Hg, and Cu. According to previous investigations, P. aeruginosa was reported several times on its ability to bioremoval of Hg and Pb in soil, with high efficiency. Also, P. putida and p. stutzeri have a high potential to remove Cd and Pb in soil, respectively. It should be mentioned that several factors, such as soil characteristics, pH, temperature, the bioavailability of heavy metals, total metal ion concentrations and chemical forms of the metals can all affect the efficiency of heavy metal bioremediation in soil. In addition, the mechanisms underlying the bioremediation of heavy metals can be broadly classified into four main categories: biosorption, bioaccumulation, biotransformation (which encompasses both bioleaching and methylation), and bioprecipitation.

A considerable number of research is conducted in laboratories under artificially controlled conditions. It is essential that the experimental parameters are designed in a manner that closely resembles natural circumstances, including factors, such as climate, weather patterns and pollution levels. Further research is required to validate the efficacy of bioremediation in real-world settings, as opposed to pot trials. It is recommended that field applications be carried out in a variety of locations. In addition, the soil pollution assessment techniques employed prior to remediation and the effectiveness evaluation conducted subsequent to remediation should be more precise, integrated, intelligent, consume less energy, and be completed more rapidly.

P., Pseudomonas; EPS, extracellular polymeric substances; ExP, exopolysaccharide; EPA; Environmental Protection Agency; Pb, lead; Cd, cadmium; Hg, mercury; Cr, chromium; As, arsenic; Ni, nickel; Zn, zinc; Cu, copper; Al, aluminium; Co, cobalt; Fe, iron; Mn, manganese; Mg, magnesium; FTIR, fourier-transform infrared spectroscopy; ORF, open reading frame.

AZ designed the research study, wrote the manuscript, and approved the final manuscript; SFSR participated in designing the research study, wrote the manuscript, searching references, and approved the final manuscript. Both authors have participated sufficiently in the work and agreed to be accountable for all aspects of the work.

Not applicable.

Not applicable.

This research received no external funding.

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

Publisher’s Note: IMR Press stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.