1 Department of Microbiology, M.G.S. University, 334004 Bikaner, India

2 Department of Industrial Biotechnology, School of Engineering Sciences in Chemistry, Biotechnology and Health (CBH), KTH Royal Institute of Technology, 114 28 Stockholm, Sweden

3 Department of Environmental Sciences, M.G.S. University, 334004 Bikaner, India

4 Faculty of Biomedical Sciences, Phenikaa University, Yen Nghia, Ha Dong, 12116 Hanoi, Vietnam

5 Department of Chemistry, School of Engineering Sciences in Chemistry, Biotechnology and Health, KTH Royal Institute of Technology, AlbaNova University Center, 106 91 Stockholm, Sweden

Abstract

Recently, the importance of biocatalysis in bioenergy has been noted, with policymakers and regulatory authorities intervening at the technological level to establish more efficient, varied, and vast-scale exploitations of biocatalysis. These approaches leverage natural catalysts, primarily enzymes, to facilitate the breakdown of larger organic compounds into simpler molecules, which can be further biochemically transformed into biofuels, such as ethanol, biodiesel, and biogas, using improved versions of metabolic enzymes. Advances in enzyme engineering have significantly enhanced the stability, specificity, and activity of key enzymes involved in biofuel synthesis, such as cellulases, oxidoreductases, xylanases, glucose isomerases, butanol dehydrogenase, acetoacetate decarboxylase, ferredoxin oxidoreductases, etc. Further, synthetic biological approaches have allowed the construction of microbial cell factories with restructured integrated biocatalytic pathways, capable of converting the raw biomass directly into biofuels. Despite these advancements, challenges remain, such as the cost of enzymes, their robustness, and the scalability of their production and biotransformation processes. Ongoing research is focused on overcoming these hurdles through innovative biocatalyst design, metabolic engineering, in silico modeling, and optimization. However, changes in government policies and reduced regulatory frameworks are expected to leverage biofuel production and competitiveness with fossil fuels and gradually replace them completely. This review highlights the recent advances in the field of biocatalysis related to the production of biofuels. This review also discusses the current challenges, sustainability, promotional initiatives performed at the government level, and future directions in the field of biofuels.

Keywords

- biocatalysis

- biofuels

- biohydrogen

- biodiesel

- biogas

- bioethanol

The growing demand for energy globally and the need to reduce carbon emissions have promoted the search for sustainable energy sources. Meanwhile, biofuels from renewable biological sources offer an attractive alternative to fossil fuels. Biocatalysis, whereby enzymes (free or immobilized) and microorganisms (whole cell biocatalysis) are used to catalyze chemical reactions under in situconditions, has emerged as a promising technique to produce biofuels [1]. However, traditional fermentation processes using yeast or bacteria to produce ethanol have significant limitations. These include low tolerance to high ethanol concentrations and the production of undesirable byproducts, highlighting the need for innovations in biofuel production technology. These may be generated using immobilized or engineered enzymes or those obtained from extremophiles [2, 3, 4, 5].

Enzymes are proteins that catalyze specific chemical reactions and represent key players in biocatalysis. Moreover, enzymes can be sourced from various organisms such as bacteria, fungi, algae, and plants [6, 7]. For instance, cellulases and hemicellulases are enzymes that break down cellulose and hemicellulose (the main components in plant biomass) into sugars that can be fermented to produce biofuels. Lipases and esterases can convert vegetable oils and animal fats into biodiesel. Meanwhile, biocatalysis using the isolated, immobilized, engineered, or naturally robust enzymes has numerous advantages over traditional fermentation processes [4, 8]. Firstly, these enzymes are more efficient and selective than microorganisms, leading to higher yields and purer products, ensuring the quality of biofuels. Secondly, enzymes can be used in milder reaction conditions, reducing energy consumption and operating costs. Finally, enzymes can be engineered per the reaction requirements and easily immobilized, allowing for continuous processes and easier product separations. However, using enzymes for biofuel production has some challenges. Indeed, one major challenge is the cost of enzymes since these are expensive to produce, purify, and immobilize; moreover, enzymes have shorter shelf lives, limiting their use in large-scale applications. Therefore, the urgent need to develop low-cost and highly efficient enzymes is not just a goal, but a necessity for commercial success and viability of biocatalysis in biofuel production.

Another challenge is the stability of enzymes, which can be affected by factors such as temperature, pH, and the presence of inhibitors. Meanwhile, researchers are exploring various strategies to overcome these challenges, such as genetic/enzyme engineering, the use of enzyme stabilizing agents, sourcing extremophilic enzymes from archaea [5], and the reconstruction of ancestral sequences approach [9] to search for novel enzymes with better biocatalytic properties [10, 11]. In addition, the choice of substrate for biofuel production is crucial for the success of biocatalysis since the availability and cost of the substrates and their composition and complexity can affect the efficiency of enzyme-catalyzed reactions. Therefore, developing efficient and cost-effective pretreatment and hydrolysis methods for converting raw substrates to fermentable substrates, precursors, or intermediates that can be enzymatically transformed into different biofuels is essential for biocatalysis in biofuel production. Nevertheless, biocatalysis offers an attractive alternative to traditional fermentation processes for producing biofuels. The use of enzymes offers several advantages, including shorter production times with higher yields, fewer contaminants with purer products, and milder reaction conditions compared to the chemosynthetic processes. However, the cost and stability of enzymes, the choice of substrates, their ease of availability, and the status regarding their food and feed demand are important challenges that need to be addressed for the commercial viability of biocatalysis in biofuel production. Further research and development in this area are essential for the realization of sustainable and renewable sources of energy [2, 12].

Biofuel refers to artificial hydrocarbon fuels derived from living beings, especially plants, microorganisms, and animals, in short durations, e.g., a few days to weeks. These artificial hydrocarbon fuels are renewable, environmentally friendly, and would represent a sustainable fuel choice in the future. Physically, these fuels can be classified into (i) solid: wood, agricultural waste, charcoal, dry manure, and firewood; (ii) liquid: bioethanol, biomethanol, biobutanol, and biodiesel; (iii) gaseous biofuels: biogas and biohydrogen. The main focus of this review is on liquid and gaseous biofuels.

Biofuels are also classified into various generations based on developmental order.

(i) First-generation biofuels, or conventional biofuels, refer to any biofuel made from a feedstock directly derived from human foods, such as sugars, starch, or vegetable oils. These biofuels are responsible for the food vs. feed debate.

(ii) Second-generation biofuels are produced from non-food crops or byproducts of food crops, such as wood, forest waste, food crop waste, waste vegetable oil, industrial waste, and biomass crops. Although second-generation biofuels do not rely on food crops per se, certain food products can become second-generation fuels when they are no longer useful for consumption.

(iii) Third-generation biofuels are produced from algal biomass or metabolism. Producing biofuels from algae has the advantage of using non-potable salty or marine water for cultivation.

(iv) Fourth-generation biofuels are produced from genetically engineered crops grown on non-arable land that can fix high amounts of CO2 to produce greater quantities of biomass, which can be conveniently converted into biofuels using second-generation techniques.

The rising global population increasingly demands increased resources for food, transport, and industrial production of commodities and other required items. These can be met by increasing the energy supply of fuels and electricity. Currently, fossil fuels are used to generate electricity, and liquid fuels remain in the developmental stages as renewable energy sources, especially biofuels. According to the Renewables 2019 report of the International Energy Agency, the total output of biofuels is expected to reach 190.3 billion liters (50.3 billion gallons) in 2024, a 25% increase from the 2018 levels [13], which can be fulfilled by producing biofuels at a substantial scale and using them to meet most of the energy demand in the present and near future [14]. Biofuels can be produced through animal, plant, and microbial biomass or lipids through fermentation and/or biochemical processes, where enzymatic catalysis or whole-cell biocatalysis may play a major role [15]. Since biofuel production from animals may require the animal to be sacrificed, this production method may present numerous ethical issues in many countries. Conversely, plants, algae, and microorganisms (microalgae, bacteria, and fungi) are more readily accepted sources of biofuel production [14, 16]. Biofuel production using plants and algae has been extensively investigated as these sources can fix the environmental CO2 to usable sugars or fats through photosynthesis [17, 18]. Plant and algal sugars can be converted to various biofuels, such as ethanol and butanol, through fermentation, and their lipids can be converted to biodiesel [19]. Recently, microalgae and cyanobacteria have been noted as newer sources of biomass and lipids that can be converted into biofuels [18].

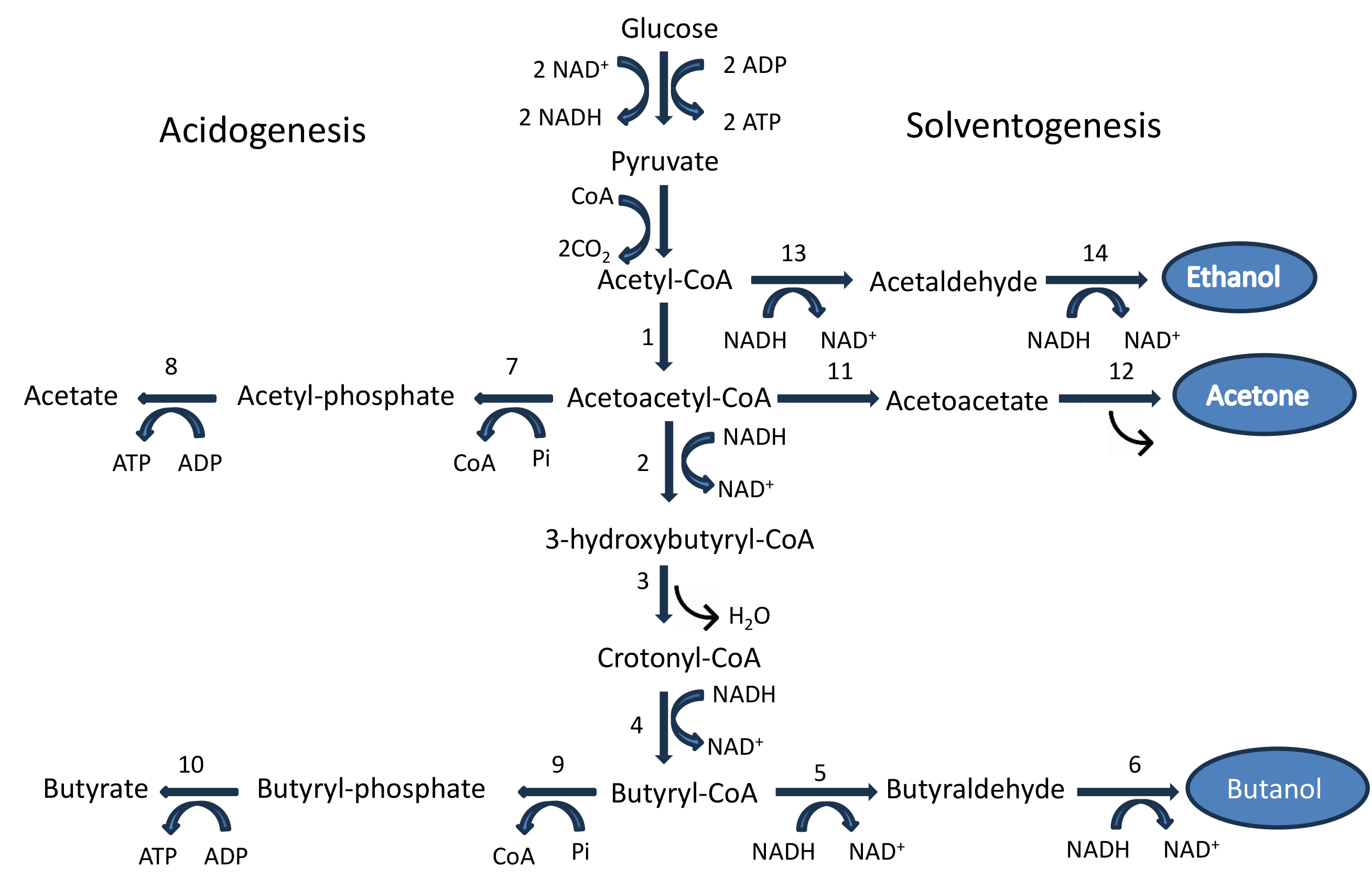

Bioethanol, biobutanol, and biomethanol comprise a major part of biofuels. Bioethanol and biobutanol can be produced through acetone–butanol–ethanol (ABE) fermentation carried out by different species of Clostridium, such as C. acetobutylicum, C. beijerinckii, etc. [20]. Fig. 1 (Ref. [21, 22, 23]) presents the biochemical routes showing the intermediates, enzymes involved, and branched pathways leading to the formation of various biofuels.

Fig. 1.

Fig. 1.

Butanol biosynthesis pathway in C. acetobutylicum.

Numbers refer to the enzymes employed: 1. acetyl-CoA acetyltransferase

(thiolase); 2.

Butanol synthesis is catalyzed by six enzymes, namely thiolase, also known as

acetyl-CoA acetyltransferase (THL),

CoA-transferase and acetoacetate decarboxylase are the key enzymes involved in acetone synthesis. CoA-transferase catalyzes the formation of the intermediate acetoacetate by transferring CoA from acetoacetyl-CoA to either acetate or butyrate. Acetoacetate decarboxylase (AADC) is the next important enzyme in this pathway, which decarboxylates acetoacetyl-CoA to acetone by releasing a CO2 molecule [21].

Ethanol synthesis is dependent on two key enzymes, namely, coenzyme A-acylating aldehyde dehydrogenase (CoA-AAD) and NAD(P)H alcohol dehydrogenase [NAD(P)H-ADH]. CoA-AAD is also an important enzyme (enzyme no. 13 in the biosynthetic pathway) that diverts acetyl-CoA towards ethanol synthesis during the fermentation process of C. acetobutylicum American Type Culture Collection (ATCC) 824. NAD(P)H-ADH then converts the acetaldehyde (generated through CoA-AAD action) to ethanol through a reduction process using the reducing power of NAD(P)H [21].

Bioethanol can also be produced through ethanolic fermentation performed by Saccharomyces cerevisiae [24]. Biomethanol, on the other hand, is created through a thermochemical or biochemical pathway. The biochemical path for methanol production involves the anaerobic degradation of biowastes to produce biogas, which involves four stages: hydrolysis, acetogenesis, acidogenesis, and methanogenesis. The microorganisms involved in methanol production are methanotrophic bacteria, including Methylococcus capsulatus and Methylobacterium extorquens [25].

Biohydrogen production uses biological systems such as bacteria, algae, or fungi to produce hydrogen gas. Biohydrogen production has been achieved through various pathways, including fermentation and photosynthesis. Biochemistry in biohydrogen production varies depending on the specific pathway and microorganisms involved, but some principles are common [14].

Fermentative biohydrogen production involves the use of anaerobic bacteria, such as Clostridium paraputrificum, C. butyricum, C. beijerinckii [26], and Ruminococcus albus [27], or facultative anaerobic bacteria such as Escherichia coli [28], Enterobacter cloacae [29], and Citrobacter freundii [30]. These bacteria can degrade organic compounds, especially carbohydrates, via an anaerobic fermentative pathway. Fermentation produces hydrogen gas and other byproducts such as acetic acid, butyric acid, and ethanol. As there is an incomplete breakdown of sugar molecules, the H2 yielded by this process is lower than that produced by photofermentative biohydrogen using phototrophic bacteria, such as the purple bacteria [31]. The overall reaction can be presented as:

meanwhile, when Y = acetic acid, the value of x = 4, i.e., 4 moles of H2 is produced from 1 mole of glucose, whereas when Y = butyric acid or ethanol, then x = 2, i.e., 2 moles of H2 is produced from 1 mole of glucose [32].

Fermentative biohydrogen production by Clostridium occurs when a proton is the final electron acceptor, forming hydrogen [33]. H2 production from protons is dependent on the activity of two types of hydrogenases: (i) pyruvate: ferredoxin oxidoreductase, which transfers electrons from reduced ferredoxin to protons and reduces these protons to H2; (ii) NADH: ferredoxin oxidoreductase, which uses NADH as the electron donor to reduce H+ to H2 [34].

(i) Direct biophotolysis: Photosynthetic biohydrogen production involves using photosynthetic microorganisms such as green algae and cyanobacteria. These microorganisms use light energy to split water into oxygen and hydrogen gas, known as photolysis. The overall reaction can be presented as:

in this reaction, water is split into two molecules of hydrogen gas and one molecule of oxygen using light energy. The above reaction scheme (2) can be further subdivided into two steps:

the reaction (3) occurs in all oxygenic phototrophs, but the second reaction (4) requires anaerobic or microaerobic conditions. The bidirectional hydrogenases catalyze the reaction (4), i.e., the H2 production step. There are two types of bidirectional hydrogenases: [Fe–Fe] enzymes, found in algae, and [Ni–Fe]-hydrogenases, found in cyanobacteria [14, 35].

(ii) Indirect biophotolysis: This method uses cyanobacteria and microalgae to produce hydrogen from stored carbohydrates in two steps. In the first step, carbohydrates (such as glycogen and starch) are synthesized in the presence of light. In the second step, these carbohydrates are utilized to produce hydrogen through photofermentation [14].

H2 production is a byproduct of the nitrogen fixation process in the indirect biophotolysis process, and the nitrogenase system represents the enzyme involved [14]. This process is also sensitive to oxygen, as the nitrogenase is deactivated in the presence of O2. Therefore, H2 production through this process occurs in specialized cells, such as heterocysts (found in filamentous cyanobacteria such as Nostoc), which lack photosystem II (PS-II) and do not perform the water-splitting reaction that evolves O2. Alternatively, some phototrophs (such as Cyanothece) perform photosynthesis during the daytime and H2 production at night [36]. At night, high respiration rates result in a microaerobic intracellular environment that allows N2 fixation and simultaneous H2 production by the nitrogenase system [37]. The rate of H2 production is highest in the absence of nitrogen when nitrogenase exclusively catalyzes the reduction of H+ to H2 [31].

Purple phototrophic bacteria (PPB) mainly produce biohydrogen through anoxygenic

photosynthesis. In place of water, these bacteria use hydrogen sulfide as a

source of electrons or reducing agents, releasing sulfur as a byproduct rather

than oxygen [38]. Purple phototrophic bacteria use light in the near-infrared

region (

Biodiesel is another renewable energy source that is a suitable substitute for hydrocarbon diesel. Biodiesel is largely prepared through the transesterification reaction between triacylglycerides and alcohols (methanol or ethanol). Moreover, enzymes such as lipase and phospholipase are crucial for biodiesel synthesis. Some companies use enzymatic processes to commercialize biodiesel [8, 40]. Lipase converts free fatty acids (FFAs) and triacylglycerol into fatty acid methyl esters, which are the main components of biodiesel [8]. Phospholipase converts phospholipids into diacylglycerols, which are then transesterified to ethanol or methanol by lipases to produce the corresponding fatty acid ethyl/methyl esters [40]. Traditional methods using methanol and chemical catalysts must remove FFAs and phospholipids to enhance biodiesel quality. However, enzymes can use these compounds as substrates, resulting in higher yields and reduced chemical waste [41]. Despite the availability of these enzymes, the high cost limits their use, especially with clean plant oils. Therefore, to reduce costs, enzymes can be immobilized on solid substrates for reuse, produced more cost-effectively, or enhanced activity [42].

Biodiesel production through microbial fermentation provides more efficient, less costly, and sustainable biodiesel production strategies, which multiple biotechnology start-ups and research centers are investigating. Genetic manipulations play important roles in transforming microorganisms into efficient manufacturers with high capabilities for enhanced biodiesel production. Indeed, microorganisms can produce biodiesel using different fatty acid sources (both endogenous and exogenous) and serve as catalysts in this process. Oleaginous microorganisms are currently being used and investigated for their potential to provide a cheap and enormous supply of fatty acids/lipids for efficient and sustainable biodiesel production. Grease microorganisms can convert agro-industrial materials (e.g., plant and algal biomass) to cellular lipids [3]. Grease strains have been reported in bacterial species (Rhodococcus opacus DSM 1069, Gordonia sp. DG), fungi (Cryptococcus sp. (KCTC 27583), Fusarium oxysporum), and algae (Chlorella vulgaris, Dunaliella primolecta, etc.) [43]. The current genetic engineering approach uses E. coli as the host for the co-expression of the wax ester synthase/acyl-CoA-diacylglycerol acyltransferase (WS/DGAT) gene from the Acinetobacter baylyi strain ADP1 and ethanol production genes from Z. mobilis [44]. This strategy has been shown to produce biodiesel (wax esters) within the bacterial cell upon availability of fatty acyl-CoA substrate, as shown below:

the bacterial strain may provide the fatty acyl CoA substrate exogenously/endogenously by genetic manipulations [44].

Enzymes also play a crucial role in transforming agricultural feedstocks into usable substrates required for the production of biofuels. Thus, developing and optimizing these biocatalysts are vital to advancing sustainable biofuel technologies, which are essential for reducing reliance on fossil fuels and mitigating environmental impacts. Continued research and optimization of these biocatalysts are crucial for improving the efficiency and scalability of biofuel production. Concise information showing the important depolymerizing and oxidizing enzymes for the conversion of agricultural feedstock to fermentable sugars and enzymes involved in metabolic pathways for the production of different biofuels is presented in Table 1 (Ref. [23, 27, 31, 34, 38, 45, 46, 47, 48, 49, 50, 51, 52, 53, 54, 55, 56, 57, 58, 59, 60, 61, 62]).

| Enzymes | Source organism | Substrate | Biofuel type | Reaction type | Advantages | Ref. |

| Cellulases | Trichoderma reesei, Aspergillus niger | Cellulose | Ethanol | Hydrolysis | Efficient breakdown of cellulose into fermentable sugars | [48, 49] |

| Hemicellulases | Thermotoga maritima, Aspergillus spp. | Hemicellulose | Ethanol | Hydrolysis | Converts hemicellulose into xylose and other sugars | [50, 51] |

| Ligninases | Phanerochaete chrysosporium, Pleurotus ostreatus | Lignin | Ethanol | Oxidative degradation | Degrades lignin, enhancing access to cellulose and hemicellulose | [52] |

| Lipases | Candida antarctica, Rhizomucor miehei | Triglycerides | Biodiesel | Transesterification | High specificity for ester bond formation, crucial for biodiesel production | [53, 54] |

| Amylases | Aspergillus oryzae, Bacillus amyloliquefaciens | Starch | Ethanol | Hydrolysis | Breaks down starch into fermentable sugars, suitable for bioethanol production | [55, 56] |

| Xylanases | Bacillus subtilis, Aspergillus niger | Xylan | Ethanol | Hydrolysis | Degrades xylan into xylose, enhancing ethanol yield | [45] |

| Pectinases | Aspergillus niger, Penicillium spp. | Pectin | Ethanol | Hydrolysis | Hydrolyzes pectin, facilitating the release of fermentable sugars | [47] |

| Proteases | Bacillus licheniformis, Aspergillus oryzae | Proteins | Biohydrogen | Hydrolysis | Breaks down proteins, facilitating microbial hydrogen production | [57, 58] |

| Aspergillus niger, Saccharomyces cerevisiae | Cellobiose | Ethanol | Hydrolysis | Converts cellobiose to glucose, boosting ethanol yield from cellulose | [59] | |

| Phytases | Aspergillus niger, Peniophora spp. | Phytate | Bioethanol | Hydrolysis | Releases phosphate from phytate, improving fermentation efficiency | [60] |

| Laccases | Trametes versicolor, Pleurotus ostreatus | Lignin and phenolic compounds | Ethanol, Biohydrogen | Oxidation | Degrades lignin and detoxifies phenolic compounds, aiding in biofuel production | [46] |

| Glucose isomerases | Streptomyces spp., Bacillus sp. | Glucose | Ethanol | Isomerization | Converts glucose to fructose, which can be fermented into bioethanol | [61, 62] |

| Butanol dehydrogenase | C. acetobutylicum, C. beijerinckii | Butyraldehyde | Butanol | Oxidation | Converts glucose to butanol through anaerobic fermentation | [23] |

| Acetoacetate decarboxylase | C. acetobutylicum, C. beijerinckii | Glucose | Acetone | Oxidation | Converts glucose to acetone through anaerobic fermentation | [23] |

| Ferredoxin oxidoreductases | Clostridium paraputrificum, C. butyricum, C. beijerinckii, Ruminococcus albus | H+ | H2 | Reduction | Two types of hydrogenases: (i) pyruvate: ferredoxin oxidoreductase, transfers electrons from reduced ferredoxin to protons and reduces them to H2; (ii) NADH: ferredoxin oxidoreductase, uses NADH as the electron donor to reduce H+ to H2 | [27, 34] |

| Nitrogenases | Purple phototrophic bacteria | Formic, acetic, and butyric acids | H2 | Reduction | Nitrogenase uses reducing power (electrons) supplied by the photoassimilation of organic acids to produce H2 from protons (H+) | [31, 38] |

Cellulases are a group of enzymes that specifically target cellulose, a

polysaccharide found in the cell walls and lignocellulose components of plants.

These enzymes catalyze the hydrolysis of cellulose into glucose and other

fermentable sugars, which are then used to produce biofuels such as ethanol and

biobutanol. The cellulase–enzyme complex includes three enzymes: (i)

Endoglucanases: These enzymes cleave internal bonds within the cellulose chain,

creating shorter cellulose fragments; (ii) exoglucanases (or cellobiohydrolases):

These enzymes act on the ends of cellulose chains to release cellobiose and

glucose units; (iii)

Endoglucanases, also called carboxymethyl cellulase (CMCase), cleave internal bonds within the amorphous regions of cellulose, creating nicks that ultimately convert lignocelluloses into simple sugars. These enzymes are valued for their low energy requirements and high specificity, making them cost-effective [64]. Commercial endoglucanase production typically involves fungal strains of Aspergillus and Trichoderma and bacterial strains such as Streptomyces sp. and Bacillus sp. [65]. Endoglucanases operate through two primary mechanisms—retention and inversion—to hydrolyze cellulose [63].

Exoglucanases, also known as cellobiohydrolases (CBHs), work in concert with

endoglucanases and

The final and crucial step in converting cellulose into simpler sugars is

conducted by

Hemicellulose is a key structural polysaccharide found in the cell walls of plants. Hemicellulose is a branched, heteropolymeric carbohydrate composed of a mix of hexose (six-carbon) and pentose (five-carbon) sugars [69]. Hemicellulose is critical in the plant cell wall, providing structural support and contributing to the flexibility and strength of the wall. Hemicellulose also forms a matrix around cellulose fibers and interacts with lignin, another major cell wall component, to stabilize the cell wall structure. This interaction is crucial for maintaining cell wall integrity and overall plant rigidity. The breakdown of hemicellulose is performed by a group of enzymes known as hemicellulases. Xylanases are crucial in enhancing the saccharification of lignocellulosic waste, including hemicelluloses such as xylan. By breaking down these complex polysaccharides, xylanases increase the availability of sugars for fermentation, thereby boosting biofuel production [45]. Both bacterial and fungal species have been employed for xylanase production, including B. subtilis, B. amyloliquefaciens, B. stearothermophilus, Clostridium thermocellum, Streptomyces sp., Aspergillus spp., and Trichoderma spp. [45].

Lignin is a complex organic polymer found in plant cell walls, particularly in wood and bark. It is one of the most abundant natural polymers on Earth, second only to cellulose. Lignin is crucial in providing structural support to plants by reinforcing the cell walls, making them rigid and resistant to decay [70]. This polymer is highly cross-linked, which provides its characteristic hardness and insolubility in water.

Laccase is a multicopper oxidase enzyme that is crucial in lignin degradation. Laccase catalyzes the oxidation of phenolic substrates, leading to the breakdown of lignin into smaller, more manageable components. Laccase is produced by various organisms, including fungi, bacteria, and plants, but it is most commonly associated with white-rot fungi, which are highly efficient lignin degraders [71]. The lignin degradation mechanism employed by laccase involves oxidizing phenolic hydroxyl groups in lignin, generating phenoxy radicals. These radicals can undergo further reactions, including depolymerization, leading to the breakdown of the complex lignin structure into smaller aromatic compounds [46]. Laccase can also act on non-phenolic lignin structures when combined with mediators, which are small molecules that extend the range of substrates that laccase can oxidize. This mediator system enhances the efficiency of lignin degradation, making laccase a powerful tool in biotechnological applications aimed at lignin valorization. In addition to its role in natural lignin degradation, laccase has gained significant attention for its potential in producing biofuels from lignocellulosic biomass [72].

Pectin is a naturally occurring polysaccharide found in the cell walls of plants, particularly in the primary cell walls and middle lamellae. Pectin plays a crucial role in maintaining the structural integrity of plant tissues by acting as a cementing substance that binds cells together. Pectin is composed mainly of galacturonic acid units, which are linked together to form a linear chain, though it can also include various side chains of other sugars [73].

Pectinase plays a crucial role in pectin degradation by cleaving the glycosidic bonds within the pectin molecules. This leads to the depolymerization and solubilization of pectin into simpler sugars such as galacturonic acid. Pectinase is produced by various microorganisms, including bacteria, fungi, and yeasts, as well as by some plants [74]. In biofuel production, pectinases contribute to the breakdown of plant cell walls, facilitating biomass conversion into bioethanol. Specifically, in biomass with lower lignin content, pectinases aid in the degradation of plant materials, enhancing the efficiency of enzymatic conversion processes [47, 75].

Protease enzymes play an important role in the degradation of biomass used to produce biofuels. Indeed, protease enzymes degrade proteins in plant and microbial biomass. While the primary focus in biofuel production often centers on the breakdown of carbohydrates, such as cellulose and hemicellulose, the degradation of proteins is also crucial, particularly in processes involving complex biomass such as algae, which contain significant protein content [76].

In the context of biofuel production, proteases contribute to the overall efficiency of biomass conversion by hydrolyzing proteins into smaller peptides and amino acids. This process not only helps reduce the protein content in the biomass, thereby increasing the relative concentration of fermentable sugars, but also releases nitrogen, which can serve as a nutrient for microbial communities involved in subsequent fermentation processes [76]. The breakdown of proteins by proteases can improve the accessibility of other enzymes, such as cellulases and hemicellulases, to the carbohydrate components in the biomass, thereby enhancing the overall yield of biofuels such as bioethanol and biogas. This leads to a more efficient conversion process, ultimately improving the cost-effectiveness and sustainability of biofuel production.

The International Organization for Standardization (ISO) and other bodies have developed specific standards for different types of biofuels, ensuring global consistency in quality measures.

(i) Feedstock selection: The type and quality of feedstock used in biofuel production significantly impact the quality of the final products. Common feedstocks include vegetable oils, animal fats, non-edible oils from plants [77] and microorganisms [78], agricultural residues, and microbial biomasses [12, 79]. Each feedstock has unique properties that affect the combustion characteristics, energy content, and emission profile (g/m3) of the biofuel. For instance, feedstocks with high free fatty acid content can produce biodiesel with poor cold-flow properties [77].

(ii) Production processes: The methods used to convert feedstock into biofuel also play a critical role in determining quality. Transesterification is commonly used for biodiesel production, while fermentation and distillation are typical for bioethanol production. Advanced biofuels, such as those produced through gasification or pyrolysis, can offer higher quality due to more controlled processes and better feedstock utilization [22, 78]. Impurities, incomplete reactions, and byproducts can degrade biofuel quality if the production process is not carefully managed [77].

(iii) Compliance with standards: Adherence to established quality standards and certifications is essential for ensuring biofuel quality. Standards such as American Society for Testing and Materials (ASTM) D6751 and EN 14214 for biodiesel and ASTM D4806 for ethanol set stringent specifications for parameters, such as cetane number, sulfur content, water content, and acid value. Compliance with these standards ensures that biofuels perform reliably in engines and do not cause damage or increase emissions.

(iv) Storage and handling: Proper storage and handling practices are critical to maintaining biofuel quality. Biofuels are susceptible to degradation through oxidation, microbial contamination, and water absorption. These factors can lead to sediments, gums, and acids forming, adversely affecting fuel quality and engine performance. Hence, using appropriate storage materials, maintaining optimal storage conditions, and adding stabilizers can help preserve biofuel quality over time.

(v) Engine compatibility and performance: The quality of biofuels also depends on their compatibility with existing engine technologies and their performance characteristics. High-quality biofuels should perform similarly or better than conventional fuels, including energy output, combustion efficiency, and emission levels. Biofuels with high cetane numbers, low sulfur content, and good lubricity are preferable for diesel engines, while those with high octane numbers are suitable for gasoline engines [79].

While significant progress has been made, challenges remain in scaling up biocatalytic processes for industrial biofuel production. These include improving the cost-effectiveness of enzyme production processes, increasing the robustness and specificity of engineered enzymes to catalyze specific reaction for higher product yield with lower side reactions, developing cost-effective enzyme immobilization methods, advancements in continuous biofuel production processes using the immobilized enzymes, optimizing biomass/feedstock conversion to maximize the yields of biofuels and evolving the enzyme reactors at commercial scales for sustainable production of different biofuels. However, other correlated challenges must also be tackled to sustain biofuel production. These include but are not limited to (i) fluctuating oil prices: the fluctuating oil prices affect the viability of biofuels; (ii) the cultivation of biofuel crops is expected to alter and use patterns that may promote deforestation and loss of biodiversity, this may impose regulatory constraints on their production; (iii) problem of consistent and sustainable supply of feedstock for biofuels production; (iv) generation of biofuels feedstocks in regions with limited water availability is assumed to put extra burden on the available water resources for food crop cultivation and other potable uses.

The challenges discussed here may be overcome through some measures such as (i) using algae-based biofuel feedstocks as promising future resources that are expected to bring the production of biofuels to the front; (ii) government policies that would incentivize and subsidize biofuel production shall further boost their sustainability; (iii) regulatory frameworks should be more oriented to address environmental economic challenges; (iv) developing certification for biofuels standards can enhance their acceptability and wide-scale applications; (v) blending of biofuels with petroleum-based fuels may result in more resilient and sustainable energy systems. For continuous development in biofuels to achieve sustainability goals, future research should focus on integrating omics technologies, utilizing genomics, proteomics, and metabolomics to improve understanding and optimize the metabolic pathways involved in biofuel production. The goal is to develop robust enzyme cocktails that can work synergistically to break down complex biomass materials efficiently.

Biocatalysis holds great promise for the sustainable production of biofuels. The

efficiency and viability of biofuel production processes continue to improve

through the evolution of engineering enzymes to create tailor-made enzymes with

required specificities, development of cost-effective enzyme immobilization

techniques and immobilized enzyme reactors, progress in the continuous

biocatalysis processes, and generation of engineered microbial cell factories for

in vivo production of biofuels. Presently, biocatalysis for the

production of biofuels relies on two types of enzyme groups: (i) metabolic

enzymes that are involved in the biochemical routes leading to the formation of

different biofuels; for example, enzymes such as acetyl-CoA acetyltransferase,

GKM: Conceptualization, Investigation, Methodology, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. SV: Formal analysis, Methodology, Writing – original draft. RC: Conceptualization, Formal analysis, Methodology, Writing – original draft. AV: Conceptualization, Formal analysis, Writing – original draft. NTTT: Formal analysis, Investigation, Writing – original draft. RK: Conceptualization, Investigation, Supervision, Formal analysis, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. All authors read and approved the final manuscript. All authors have participated sufficiently in the work and agreed to be accountable for all aspects of the work.

Not applicable.

Not applicable.

This research received no external funding.

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

Publisher’s Note: IMR Press stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.