1 Molecular Genetics and Microbiomics Laboratory, BIOTROF Ltd., 196602 Pushkin, St. Petersburg, Russia

2 Federal State Budgetary Educational Institution of Higher Education “St. Petersburg State Agrarian University”, 196605 Pushkin, St. Petersburg, Russia

3 Information Technologies, Mechanics and Optics (ITMO) University, 197101 St. Petersburg, Russia

4 School of Natural Sciences, University of Kent, CT2 7NJ Canterbury, Kent, UK

5 Animal Genomics and Bioresource Research Unit (AGB Research Unit), Faculty of Science, Kasetsart University, 10900 Chatuchak, Bangkok, Thailand

6 L. K. Ernst Federal Research Centre for Animal Husbandry, Dubrovitsy, 142132 Moscow Oblast, Russia

Abstract

Bacillus bacteria are often used in the production of biopreparations. Moreover, these bacteria can be used in agriculture as probiotics or starters for manufacturing fodder preserved by fermentation (silage). The ability of Bacillus bacteria to produce many biologically active molecules and metabolites with antimicrobial activity means that these bacteria can stimulate plant growth and restore the balance of the microbiome in the digestive system of certain animals.

Using molecular biological analysis, bioinformatic annotation, and metabolic profiling of whole genome sequences, we analyzed two promising candidates for creating biopreparations, i.e., two Bacillus strains, namely B. mucilaginosus 159 and B. subtilis 111. We compared the genomes of these two strains and characterized both their microbiomic and metabolomic features.

We demonstrated that both strains lacked elements contributing to the formation of toxic and virulent properties; however, both exhibited potential in the biosynthesis of B vitamins and siderophores. Additionally, these strains could synthesize many antimicrobial substances of different natures and spectrums of action. B. mucilaginosus 159 could synthesize macrolactin H (an antibiotic from the polyketide group), mersacidin (a class II lanthipeptide), and bacilysin. Meanwhile, B. subtilis 111 could synthesize andalusicin (a class III lanthipeptide), bacilysin, macrolactin H, difficidin, bacillaene (a polyene antibiotic), fengycin (a lipopeptide with antifungal activity), and surfactin (another lipopeptide). Further, a unique pathway of intracellular synthesis of the osmoprotectant glycine betaine was identified in B. subtilis 111, with the participation of betaine aldehyde dehydrogenase (BetB); this is not widely represented in bacteria of the genus Bacillus. These compounds can increase osmotic stability, which may be key for manufacturing biological starters for silage preparation.

These two Bacillus strains are safe for use as probiotic microorganisms or starters in producing preserved fodder. However, B. subtilis 111 may be preferable due to a wider spectrum of synthesized antimicrobial substances and vitamins. Our findings exemplify using genomic technologies to describe the microbiomic and metabolomic characteristics of significant bacterial groups such as Bacillus species.

Keywords

- Bacillus spp.

- biopreparations

- probiotics

- silage

- whole genome sequencing

- functional microbiomics

- metabolomics

- antimicrobial substances

- vitamins

- lipopeptides

Efforts to transition to more environmentally friendly agriculture systems are now commonplace worldwide. The following are desirable aspects of environmentally friendly agriculture: (1) refusal to use particular chemicals in crop production; (2) refusal to use other certain chemicals for feed antibiotics in livestock farming; (3) increasing the efficiency of roughage assimilation; (4) improving the quality of plant feed preparation; (5) reducing the share of compound feed for ruminants and other animals [1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6]. Using microorganisms with various enzymatic and metabolic activities represents one of the main components of the new environmentally friendly approach to agriculture [7, 8, 9, 10, 11, 12, 13]. Enzyme, probiotic, prebiotic, and combined enzyme–probiotic preparations are increasingly used to improve efficiency and stimulate the growth and development of ruminants and other animals. This can enhance non-specific immunity and improve the quality of feed preparation [14, 15, 16, 17, 18, 19]. The main purpose of using so-called “biopreparations” in feed production is to facilitate the creation of a microbial community that will lead to rapid acidification of the environment and prevent the development of pathogenic and opportunistic microorganisms [20, 21, 22, 23], such as clostridia and enterobacteria [24, 25, 26, 27]. Clostridia, which are found on crops and in the soil as spores, grow anaerobically. Clostridia also produce butyric acid and breaks down amino acids, making the silage tasteless and possessing reduced nutritional value. Enterobacteria are non-spore-forming facultative anaerobes that ferment sugars to acetic acid and other products and can break down amino acids [27, 28, 29, 30, 31].

The most commonly used microorganisms as probiotic preparations include bacilli, lactobacilli, and bifidobacteria [17, 22, 32, 33]. Moreover, the functional microbiomics of probiotic bacteria and their influence on related and other gut microbes have received particular attention [34, 35, 36, 37, 38, 39, 40]. The field of “gut microbiomics” investigates the function of the intestinal microbiota by examining its overall “microbiome”, including the genomes of its individual representatives [39, 41]. Microbiomics provides molecular tools for analyzing microbial communities, facilitating their comprehensive characterization. Thus, using such microbiomic approaches can provide more information regarding the function of a certain bacterial group [12, 42]. Strategies for developing food and feed preparations take advantage of incorporating genomic and microbiomic studies [38, 43, 44, 45], which generally rely upon omics and multi-omics approaches [22, 46, 47, 48]. The term “microbiomic” is currently widely used in the scientific literature [49, 50, 51, 52, 53, 54] as an adjective to mean “of, or relating to, the microbiome or to microbiomics” [55]. Paleri [56] defines microbiomic research as “Microbiomic studies cover the entire life systems as the collective genomes of the microbes that are composed of bacteria, bacteriophage, fungi, protozoa and viruses.” Thus, the term “microbiomic” was used in the present study in relation to this accepted terminology.

According to many studies, the genus Bacillus has several useful properties, making these bacteria effective biopreparations [57, 58, 59, 60, 61]. These properties include (1) high preservation, (2) stability during storage, (3) antagonistic activity to a wide range of pathogenic and opportunistic microorganisms, and (4) high enzymatic activity. Bacteria in the genus Bacillus can form endospores, which allow them to remain viable under extreme conditions, i.e., at high or low temperatures, radiation, suboptimal pH, pressure, and in the presence of toxic chemicals that damage vegetative cells [62, 63, 64]. The ability to synthesize antibiotics, bacteriocins, cyclic lipopeptides, and lytic enzymes with antimicrobial activity is characteristic of the probiotic activity of bacteria in the genus Bacillus [22, 23, 26, 65, 66, 67, 68]. The genomes of microorganisms from this taxonomic group have many loci that determine the biosynthesis of antimicrobial compounds [19]. This provides one of their most important functional properties that are considered when choosing suitable microorganisms for drug production [22]. Herewith, the metabolomic data [69, 70] suggest that Bacillus spp. can perform metabolism via the pentose phosphate pathway, making them effective producers of vitamins, among which the most significant are cobalamin, riboflavin, folic acid, and biotin [71, 72, 73]. Whole genome sequencing (WGS) allows us to assess fully the biotechnological capabilities of promising strains [61, 74, 75]. As a result, we can identify the genetic determinants that are associated with the possibility of biosynthesis of various biologically active substances important for creating biopreparations for agriculture. At the same time, we can confirm the absence of different virulence factors that designate the biological safety of using microorganism strains [22, 46].

Among the issues associated with creating probiotic preparations, it is important to reveal the presence of unknown properties in strains, both positive (synthesis of antimicrobial substances and various enzymatic activities) and negative (synthesis of undesirable substances and the presence of pathogenicity factors). The development of new technologies in molecular genetics makes it possible to rapidly determine the complete genome of microorganisms [61, 74, 75]. The use of next-generation sequencing (NGS) technologies, which include WGS, for the analysis of strains of probiotic microorganisms allows for a complete characterization of a strain under study and predicts its capabilities [61], thus facilitating the creation of an effective and safe probiotic drug [22].

Among studies on the genomes of bacilli strains, Kapse et al. [60] performed WGS to examine the B. coagulans HS243 strain. This genome study revealed the presence of several marker genes that conform to probiotic features. In particular, genome analysis of HS243 revealed the presence of multi-subunit ATPases, hydrolases, and adhesion proteins necessary for survival and colonization of the intestine. The HS243 genome also contains genes for the biosynthesis of vitamins and essential amino acids, which suggests that HS243 can be used as a food additive. The strain was found to have genes responsible for producing bacteriocins; thus, it is apparent that the B. coagulans HS243 strain can potentially prevent diseases. Sulthana et al. [61] confirmed the genetic safety of the B. subtilis UBBS-14 strain using WGS. It was shown that this strain lacks antibiotic-resistance genes (within its mobile genetic elements) and pathogenicity factors. Therefore, it can be considered biologically safe.

The present study aimed to generate and compare the genomes of two promising strains to create biopreparations: B. mucilaginosus 159 and B. subtilis 111. A comprehensive characterization and assessment of B. mucilaginosus 159 and B. subtilis 111 were achieved using molecular biological analysis and bioinformatic annotations regarding their biological properties and potential use in antimicrobial feed additives.

The B. subtilis 111 and B. mucilaginosus 159 strains were obtained from the BIOTROF LLC collection (Pushkin, St. Petersburg, Russia). Total DNA was isolated from the strains using the Genomic DNA Purification kit (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc., Waltham, MA, USA). Furthermore, we employed the Nextera DNA Flex Library Prep kit (Illumina, Inc., San Diego, CA, USA) to prepare the DNA library samples for WGS using the Illumina MiSeq platform. The MiSeq Reagent kit v3 (300 cycles; Illumina) was utilized to sequence the resultant libraries [76, 77, 78]. The above purification, preparation, and reagent commercial kits were used following the in-house protocols [38, 78, 79, 80] based on the manufacturers’ instructions.

Sequence quality assessment was performed using the specialized FastQC software [81]. Unreliable sequences and adapters were removed using the Trimmomatic-0.38 program [82]. Paired-end nucleotide sequences, filtered by a length of at least 50 base pairs (bp), were assembled de novo using the genome assemblers SPAdes-3.11.1 (for B. subtilis 111) and SPAdes v. 3.12.0 (for B. mucilaginosus 159) [83]. The genome coverage for B. subtilis 111 and B. mucilaginosus 159 was 100

Functional annotation of genomic sequences was performed using the RAST 2.0 web server (RAST, Rapid Annotations Using Subsystems Technology; [86]). Herewith, the annotation scheme followed Classic RAST, while the FIGfams protein collection version 70 [87] was used to process the genome. An additional annotation was performed using Prokka version 1.13.3 [88] and the Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes (KEGG) Pathway database [89, 90]. In particular, the resultant amino acid sequences were uploaded to the KEGG Automated Annotation Server (KAAS). The sequences were processed using the BBH (bi-directional best hit) method and the BLAST search program [89, 90].

To search for gene clusters involved in the biosynthesis of secondary metabolites [46], the antiSMASH version 7.1.0 web service [91] was used in the relaxed detection strictness mode, followed by refinements in the NCBI Protein database [92]. The Norine database [93] was utilized to identify non-ribosomal peptides (NRPs). The search for prophage sequences was performed using the PHASTER web server [94]. The virulence of genomes was analyzed using the VirulenceFinder-2.0 (version 2.0.5), with the parameters set to the %ID threshold of 90% and the minimum sequence length of 60% program, and with the support of the Center for Genomic Epidemiology web service (National Food Institute, Technical University of Denmark, Lyngby, Denmark; [95]). The antibiotic resistance determinants were searched and assessed using the ResFinder program (version 4.6.0), with all parameters specified by default [96].

As illustrated in Table 1, the genome sizes of B. subtilis 111 and B. mucilaginosus 159 were established as similar: 3,949,468 and 3,970,760 bp, respectively. The guanine-cytosine (GC) composition was similar in percentage terms and amounted to 46.6% for B. subtilis 111 and 46.3% for B. mucilaginosus 159. According to the ResFinder assessment, no antibiotic resistance determinants were found in the genomes of B. subtilis 111 and B. mucilaginosus 159. A search for genes encoding putative virulence factors by the VirulenceFinder program also showed that these were absent in B. subtilis 111 and B. mucilaginosus 159.

| Assembly characteristics | B. subtilis 111 | B. mucilaginosus 159 | Model microorganism B. subtilis subsp. subtilis str. 168 |

| Genome assembly size, bp | 3,941,553 | 3,970,760 | 4,214,814 |

| Contig N50 | 2,109,194 | 500,910 | 4,215,606 |

| Guanine-cytosine (GC) composition, % | 46.6 | 46.3 | 43.5 |

| Number of open reading frames (coding sequences) | 3991 | 4002 | 4114 |

| Genes | 3964 | 3983 | 4536 |

| Protein-coding genes | 3807 | 3817 | 4237 |

| Number of subsystems | 444 | 438 | 515 |

| Number of RNAs | 87 | 73 | 181 |

We identified all the main groups of genes for proteins that characterize the metabolomic profiles in the genomes of the B. subtilis 111 and B. mucilaginosus 159 strains. These proteins jointly mediate and modulate certain biological processes involved in the functions of amino acid transport and metabolism, as well as transcription, translation, and carbohydrate/protein transport and metabolism. The strains had products that resembled a full set of functional metabolic pathways, including glycolysis, the tricarboxylic acid cycle, and the pentose phosphate pathway.

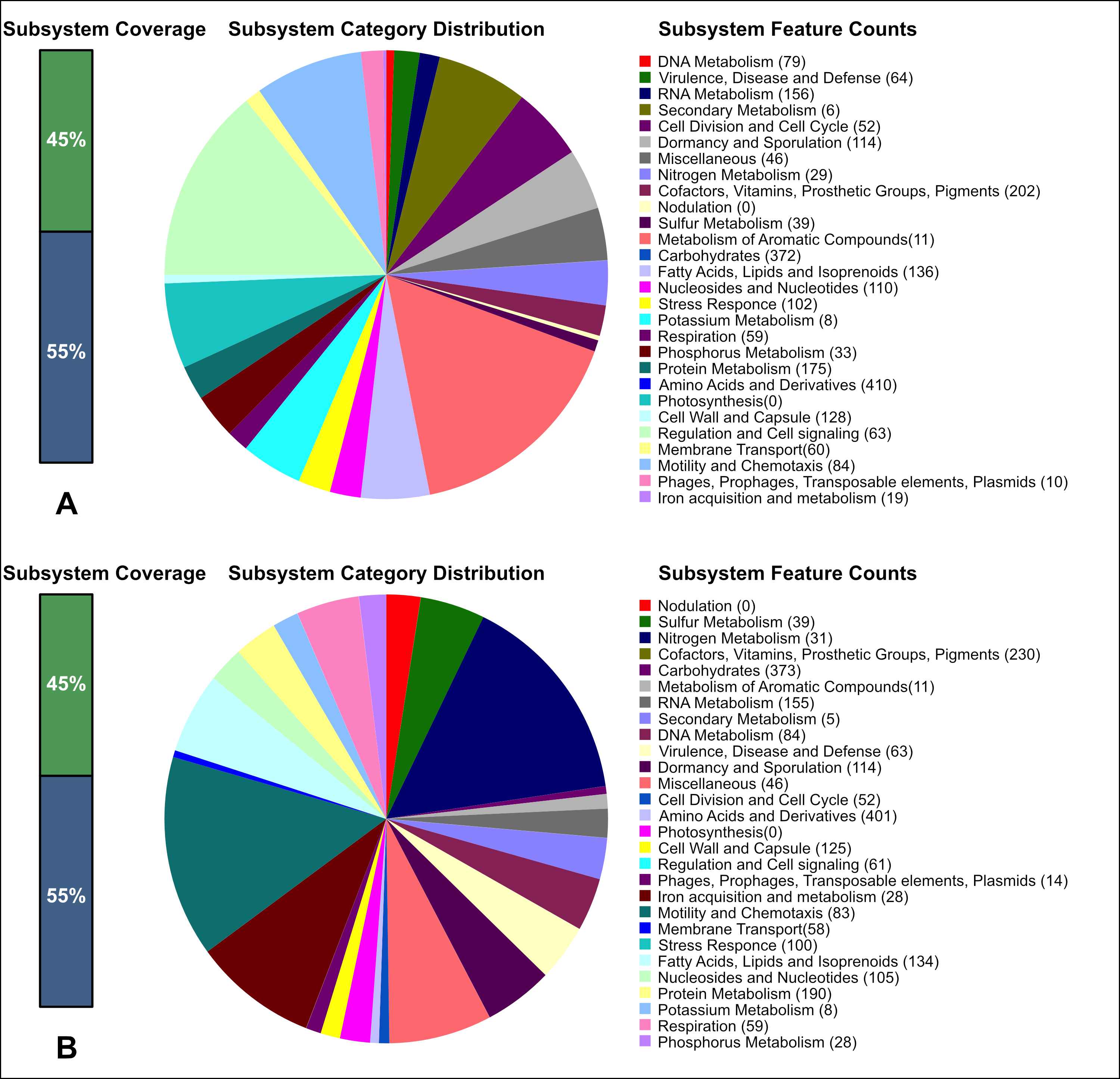

As presented in Table 2 (data produced using RAST 2.0 [86]) and Fig. 1 (data produced using RAST 2.0 [86] and antiSMASH 7.1.0 [91]), analysis of the genomes of B. subtilis 111 and B. mucilaginosus 159 in comparison to one another showed that the genomes of the studied bacteria contained a large number of genetic determinants. These define the metabolomic profiles of the strains, including the metabolism of carbohydrates, proteins, and amino acids.

| Metabolic systems | Distribution of the number of genes by functions of bacterial metabolic systems | |||||

| B. mucilaginosus 159 | B. subtilis 111 | Model organism B. subtilis subsp. subtilis str. 168 | ||||

| Total | % | Total | % | Total | % | |

| Protein metabolism | 175 | 6.8 | 190 | 7.3 | 242 | 7.1 |

| Carbohydrate metabolism | 372 | 14.5 | 373 | 14.4 | 535 | 15.8 |

| Metabolism of amino acids and their derivatives | 410 | 16.0 | 401 | 15.4 | 450 | 13.3 |

| Metabolism of nucleosides and nucleotides | 110 | 4.3 | 105 | 4.0 | 145 | 4.3 |

| Metabolism of fatty acids, lipids and isoprenoids | 136 | 5.3 | 134 | 5.2 | 102 | 3.0 |

| Metabolism of aromatic compounds | 11 | 0.4 | 11 | 0.4 | 10 | 0.3 |

| RNA metabolism | 156 | 6.1 | 155 | 6.0 | 198 | 5.8 |

| DNA metabolism | 79 | 3.1 | 84 | 3.2 | 136 | 4.0 |

| Sulfur metabolism | 39 | 1.5 | 39 | 1.5 | 44 | 1.3 |

| Phosphorus metabolism | 33 | 1.3 | 28 | 1.1 | 25 | 0.7 |

| Nitrogen metabolism | 29 | 1.1 | 31 | 1.2 | 30 | 0.9 |

| Systems determining potassium balance | 8 | 0.3 | 8 | 0.3 | 26 | 0.8 |

| Iron entry into the cell | 19 | 0.7 | 28 | 1.1 | 32 | 0.9 |

| Synthesis of cofactors, vitamins, prosthetic groups, and pigments | 202 | 7.9 | 230 | 8.9 | 311 | 9.2 |

| Cell division and cell cycle | 52 | 2.0 | 52 | 2.0 | 48 | 1.4 |

| Motility and chemotaxis | 84 | 3.3 | 83 | 3.2 | 69 | 2.0 |

| Regulation and signaling systems | 63 | 2.5 | 61 | 2.3 | 50 | 1.5 |

| Secondary metabolism | 6 | 0.2 | 5 | 0.2 | 6 | 0.2 |

| Dormancy and sporulation | 114 | 4.4 | 114 | 4.4 | 141 | 4.2 |

| Respiration process | 59 | 2.3 | 59 | 2.3 | 91 | 2.7 |

| Response to stress factors | 102 | 4.0 | 100 | 3.9 | 111 | 3.3 |

| Cell membrane transport systems | 60 | 2.3 | 58 | 2.2 | 84 | 2.5 |

| Cell wall and capsule synthesis | 128 | 5.0 | 125 | 4.8 | 142 | 4.2 |

| Cellular protection | 64 | 2.5 | 63 | 2.4 | 77 | 2.3 |

| Others | 56 | 2.2 | 60 | 2.3 | 290 | 8.5 |

| Total | 2567 | 100 | 2597 | 100 | 3395 | 100 |

Fig. 1.

Fig. 1. Analysis of the cellular metabolic systems of the two Bacillus bacteria as performed using RAST 2.0 (https://rast.nmpdr.org/) and antiSMASH 7.1.0 web service (https://github.com/antismash/antismash/releases). (A) B. mucilaginosus 159. (B) B. subtilis 111. To visualize the analysis results, the data were pre-displayed on a computer screen and saved as images using macOS Sequoia version 15 and the screenshot function. The screenshots were then edited using Adobe Photoshop (Adobe Inc., San Jose, CA, USA) version 26.1 to achieve the required quality.

Here, the strain B. subtilis 111 was found to have a higher proportion of genes involved in protein metabolism, i.e., 190 vs. 175 genes in B. mucilaginosus 159. A higher proportion of genes were also involved in the biosynthesis of cofactors, vitamins, prosthetic groups and pigments (230 vs. 202 genes) and more genes were involved in iron entry into the cell (28 vs. 19 genes). In contrast, the strain B. mucilaginosus 159 had more genes involved in amino acid metabolism (410 vs. 401 genes).

Annotation of genes in the KEGG Pathway database [89, 90] demonstrated that strain 111 is capable of biosynthesizing B vitamins (thiamine, riboflavin, pantothenic acid, B12), biotin, tetrahydrofolate, lipoic acid, and siderophores (bacillibactin). The siderophore bacillibactin is a catecholic trilactone secreted by various bacilli species for iron absorption during periods of iron limitation. Strain 159 could biosynthesize riboflavin, thiamine, and the siderophore bacillibactin.

In addition, the strains exhibited broad capabilities for the biosynthesis of fatty acids. We identified all the main enzymes responsible for forming fatty acids (C3—C18): FabD, FabF, FabG, FabZ, FabI (FabK, FabL), etc.

The genome of B. subtilis 111 contains genes for the biosynthesis of vitamin B6: thiamine monophosphate kinase [EC:2.7.4.16], thiamine phosphate phosphatase [EC:3.1.3.100], and 18 genes involved in this process. Both strains contain genes for enzymes involved in the biosynthesis of riboflavin, as well as its coenzyme derivatives, i.e., flavin mononucleotide (FMN) and flavin adenine dinucleotide (FAD): riboflavin synthase [EC:2.5.1.9], riboflavin kinase [EC:2.7.1.26], FAD synthetase [EC:2.7.7.2], FMN reductase [EC:1.5.1.38] and FMN reductase [NAD(P)H] [EC:1.5.1.39], as well as other enzymes. Strain 111 contains a gene for purine nucleoside phosphorylase [EC:2.4.2.1] involved in the biosynthesis of nicotinamide and nicotinic acid. The biological role of pantothenic acid is due to its participation in the biosynthesis of coenzyme A (CoA). The genome of strain 111 contains the enzyme pantoate-beta-alanine ligase [EC:6.3.2.1] (catalyzes the biosynthesis of B5 from pantoic acid and beta-alanine) and pantothenate kinase [EC:2.7.1.33] (the first enzyme in the pathway of CoA biosynthesis). Pantothenate kinase phosphorylates pantothenate (vitamin B5) to form 4′-phosphopantothenate using an adenosine triphosphate (ATP) molecule. Other genes were also identified in the biosynthesis of pantothenic acid from pyruvate, catalyzing its further conversion to CoA. The studied strain also possessed the biotin biosynthesis pathway and the key enzyme biotin synthase [EC:2.8.1.6].

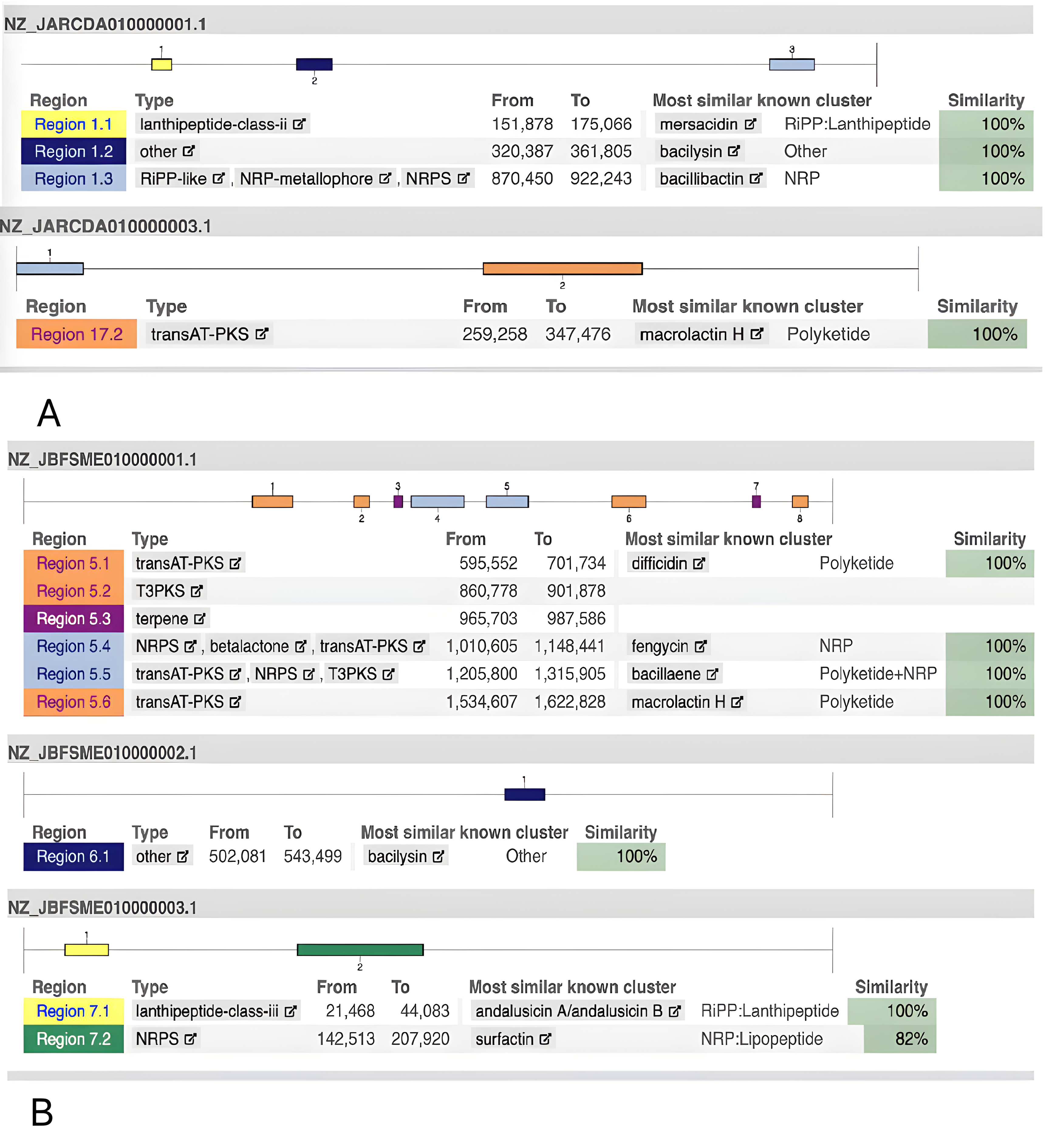

Fig. 1 shows the metabolic capacities of the two strains to synthesize antimicrobial substances. According to the complete genomic sequence analysis, the B. mucilaginosus 159 strain can simultaneously synthesize several antimicrobial compounds of different natures and spectrums of action (Fig. 2A; data produced using antiSMASH 7.1.0 [91] and KAAS [89, 90]). This analysis allowed us to identify sequences encoding biosynthesis of macrolactin H (an antibiotic from the polyketide group), mersacidin (a class II lanthipeptide), and bacilysin. The B. subtilis 111 strain genome (Fig. 2B) can synthesize andalusicin (class III lanthipeptide), bacilysin, the polyketide antibiotic macrolactin H, difficidin, and bacillaene (a polyene antibiotic).

Fig. 2.

Fig. 2. Gene clusters involved in the biosynthesis of secondary metabolites that were determined using the antiSMASH 7.1.0 web service (https://github.com/antismash/antismash/releases) and KAAS (KEGG Automated Annotation Server; https://www.genome.jp/kegg/kaas/). (A) B. mucilaginosus 159. (B) B. subtilis 111. To visualize the analysis results, the data were pre-displayed on a computer screen and saved as images using macOS Sequoia version 15 and the screenshot function. The images were then edited using Adobe Photoshop version 26.1 to achieve the required quality.

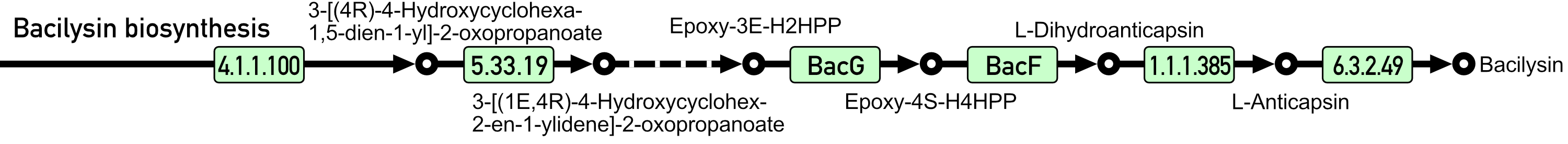

Both strains could synthesize the antibiotic bacilysin (Fig. 3; data produced using KEGG Pathway database and KAAS [89, 90]). The strains possessed all the genes controlling this process (gene cluster bacABCDE). Bacilysin is a non-ribosome-synthesized dipeptide antibiotic with an l-alanine residue at the N-terminus and a non-proteinogenic amino acid, l-anticapsin, at the C-terminus. Despite its simple structure, bacilysin is active against a wide range of bacteria and fungi, including Candida albicans. The antibacterial action of bacilysin depends mainly on its transport into host cells, its hydrolysis by intracellular peptidases to anticapsin, and inhibition of glucosamine-6-phosphate (GlcN6P) synthase by anticapsin.

Fig. 3.

Fig. 3. Biosynthesis of the antibiotic bacilysin by the strains B. subtilis 111 and B. mucilaginosus 159 (according to the KEGG Pathway database (https://www.genome.jp/kegg/pathway.html) and using KAAS (KEGG Automated Annotation Server; https://www.genome.jp/kegg/kaas/)). To visualize the analysis results, the data were pre-displayed on a computer screen and saved as images using macOS Sequoia version 15 and the screenshot function. The images were then edited using Adobe Photoshop version 26.1 to achieve the required quality.

As follows from Fig. 1B, the B. subtilis strain 111 can synthesize fengycin (a lipopeptide with antifungal activity) and surfactin (another lipopeptide).

It was previously established that Bacillus spp. lipopeptides are small metabolites with a cyclic structure formed by 7–10 amino acids (including 2–4 D-amino acids) and a beta-hydroxybutyric acid with 13–19 C atoms [97]. These lipopeptides have a variety of biological activities, including biofilm interactions and antifungal, anti-inflammatory, antitumor, antiviral, and antiplatelet properties. The multiple activities of lipopeptides have stimulated significant interest in the exploitation of these lipopeptides for use as antibiotics, feed additives, antitumor agents, acute thrombolytic therapeutics, and drug delivery systems. Hence, gaining knowledge of the inherent roles played by these structurally varied lipopeptides in Bacillus species is essential for effectively producing more potent products and understanding microbial regulatory systems. To increase the efficiency of their biosynthesis for industrial applications, ongoing efforts are required as there is currently a lack of knowledge regarding the direct target of these lipopeptides [97, 98].

Surfactin is one of the powerful surfactants of biological origin and has a wide range of potential applications in industry and medicine. The main factor limiting its active usage is the high production cost. Due to the complexity of the structure, the chemical synthesis of surfactin is unprofitable, meaning microbiological synthesis is the main approach to its production [75]. Fengycin is an antifungal lipopeptide first discovered in the B. subtilis F-29-3 strain. Fengycin inhibits mycelial fungi but is ineffective against yeast and bacteria [99, 100]. Thus, we may conclude that the B. subtilis strain 111 has a broader spectrum of activity, including fungicidal properties.

The osmotic stability of strains may be crucial for developing biological starters for silage production. If the dry matter content in the grass is 30% or more, the increased osmotic pressure in plant cells consequently leads to inhibiting the development of lactic acid bacteria and causing a slowdown in the acidification of the grass mass, especially in the first, most crucial stage of its ensiling [101]. However, using osmotolerant bacteria in silage preparations helps overcome this problem [102, 103, 104, 105]. Osmoprotectants, also known as compatible solutes, are tiny organic compounds that function as osmolytes to assist organisms in resisting excessive osmotic stress. Osmoprotectants have a neutral charge and are not hazardous at high concentrations. Overall, osmoprotectants can be divided into three chemical classes: (1) betaines and related molecules, (2) sugars and polyols, and (3) amino acids. These molecules accumulate in cells and balance the osmotic difference between the cell environment and the cytoplasm. There are two pathways for the accumulation of osmoprotectants in the cell: transport from the external environment and the biosynthesis of osmoprotectants inside the cell [106].

The uptake of osmotic stress protectants occurs via the Opu family of transporters, a system of central importance for managing osmotic stress in bacteria. The osmolarity of the environment controls opuD-mediated glycine betaine transport activity in Bacillus spp. High osmolarity maximizes glycine betaine absorption activity by activating pre-existing OpuD proteins and stimulating de novo OpuD synthesis. Strains have different mechanisms of tolerance to high osmotic pressure [107].

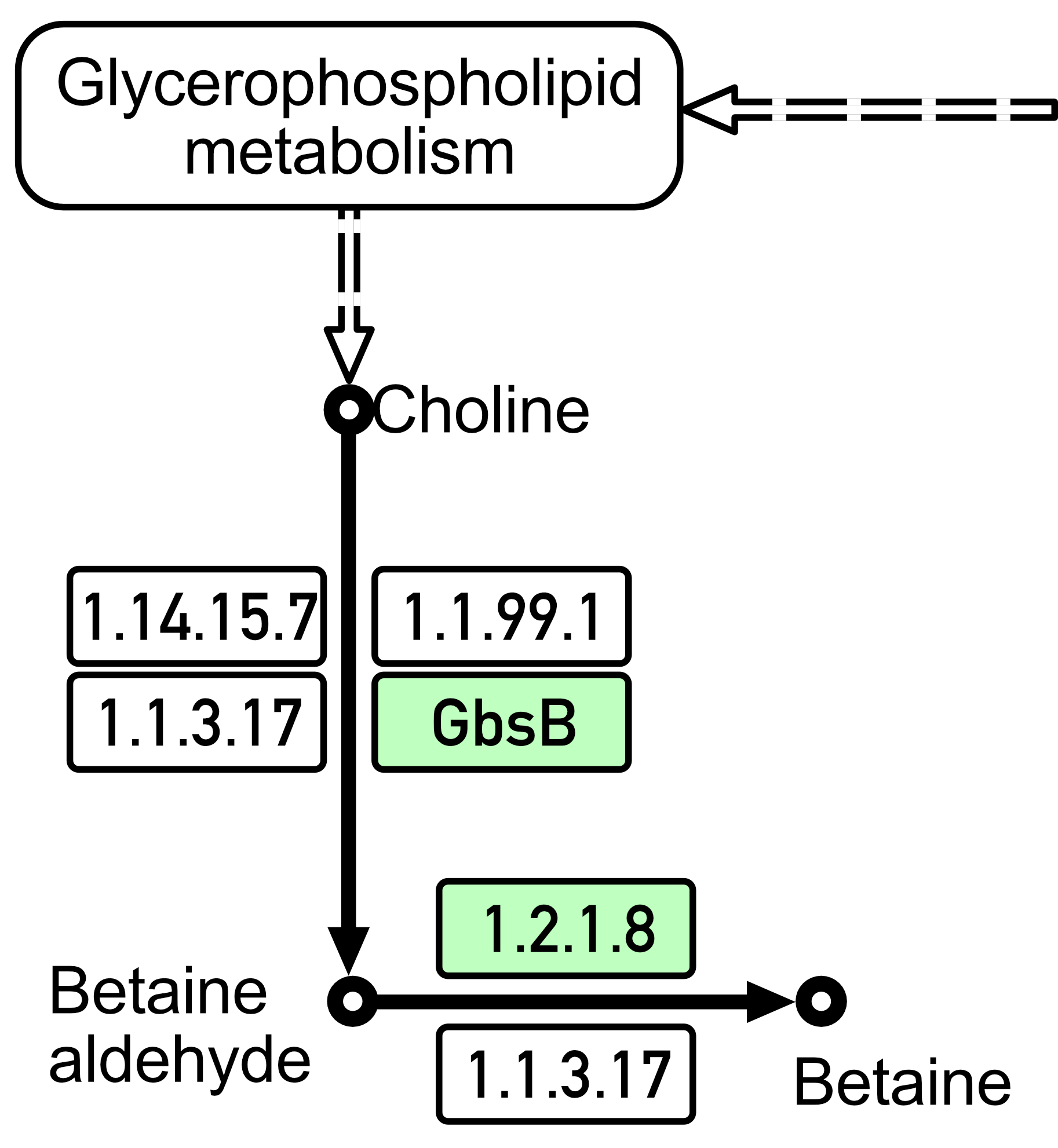

Previously, bacilli were believed to be mainly capable of synthesizing only one osmoprotective substance within themselves, i.e., proline. However, one of the adaptation mechanisms that was identified in both studied Bacillus spp. strains (as shown in Fig. 4; data produced using KAAS [89, 90]) turned out to be the biosynthesis mechanism of glycine betaine, which is a very effective osmoprotectant that accumulates in high concentrations in response to increased osmotic pressure from choline under the action of the choline dehydrogenase (BetA(GbsB)) and betaine aldehyde dehydrogenase (BetB) enzymes. Glycine betaine is synthesized in cells from choline in a two-step pathway under the action of these two enzymes [108, 109]. Among the compatible solutions used, glycine betaine plays a particularly important role for bacilli since it can be both synthesized and imported through three high-affinity and osmotically induced transport systems [107]. Glycine betaine importation is mediated by the betaine–choline–carnitine transporter (BCCT)-type transporter OpuD and the ABC transporters OpuA and OpuC [110].

Fig. 4.

Fig. 4. Biosynthesis of glycine betaine by B. subtilis 111 strain and B. mucilaginosus 159 strain (according to the KEGG Pathway database; https://www.genome.jp/kegg/pathway.html). To visualize the analysis results, the data were pre-displayed on a computer screen and saved as images using macOS Sequoia version 15 and the screenshot function. The image was then edited using Adobe Photoshop version 26.1 to achieve the required quality.

Thus, the strains we studied here are characterized not only by their ability to pump osmoprotectants from the environment but also by their ability to synthesize proline and glycine betaine independently (Fig. 4).

Our findings provide comprehensive information about the metabolomic profiles of the two strains and the functional properties of the important proteins they are capable of synthesizing. Among them, we also highlight the genetic determinants for such a crucial metabolic system as response to stress factors (Table 2) [111, 112, 113]. The present study was performed in accordance with state-of-the-art investigations aimed at describing and defining a healthy gut based on important characteristics of microbial functionality that may be derived from microbiomics and its research methodologies [13, 38, 114]; these, in turn, benefit from omics and multi-omics approaches [19, 22, 46, 47, 115].

Analysis of the genomic sequences of B. subtilis 111 and B. mucilaginosus 159 demonstrated that these bacteria were similar in terms of their metabolomic profiles based on the sets of proteins they produce. Moreover, these strains did not contain antibiotic resistance determinants or virulence factors. Antimicrobial activity against Gram-positive and Gram-negative bacteria is among the important requirements for promising strains used as silage starters. Both strains can synthesize many antimicrobial substances of various natures and spectrums of action. The B. mucilaginosus 159 strain can synthesize macrolactin H (an antibiotic from the polyketide group), mersacidin (a class II lanthipeptide), and bacilysin. The B. subtilis 111 strain can synthesize andalusicin (class III lanthipeptide), bacilysin, polyketide antibiotic macrolactin H, difficidin, bacillaene (a polyene antibiotic), as well as fengycin (a lipopeptide with antifungal activity) and surfactin (another lipopeptide). Thus, the spectrum of biosynthesized antimicrobial substances is wider in the B. subtilis 111 strain. The osmotic stability of strains can also be a determining property for generating biological starters for silage preparation. The studied strains are characterized by the ability to pump osmoprotectants from the environment and synthesize them independently, both proline and glycine betaine. In general, it can be stated that these strains are safe for use as probiotic microorganisms or as starters for obtaining preserved feed. The B. subtilis 111 strain may be preferable due to a wider spectrum of synthesized antimicrobial substances and vitamins. Our study demonstrates the applicability of modern genomic technologies to characterize functional microbiomic and metabolomic features of such important bacterial groups as Bacillus spp. and their subsequent use as antimicrobial feed additives.

This article contains a presentation of all the experiments and findings from the study. Further details can be obtained upon request from the corresponding author.

Conceptualization, GYL, LAI, VAF and EAY; methodology, LAI and VAF; software, ESP and EAB; validation, VAF, NIN and DKG; formal analysis, ESP; investigation, IAK, ASD, KAS and VAZ; resources, DGT and NIN; data curation, DGT and MNR; writing—original draft preparation, EAY and MNR; writing—review and editing, EAY, MNR and DKG; visualization, AVD, EAY and MNR; supervision, GYL and DKG; project administration, GYL and NIN; funding acquisition, LAI. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript. All authors contributed to editorial changes in the manuscript. All authors have participated sufficiently in the work and agreed to be accountable for all aspects of the work.

Not applicable.

Not applicable.

The research was supported by the Russian Science Foundation grant No. 23-16-20007 (https://rscf.ru/project/23-16-20007/) and by the St. Petersburg Science Foundation grant No. 23-16-20007.

The authors declare no conflicts of interest. Authors Valentina A. Filippova, Georgi Yu. Laptev, Larisa A. Ilina, Elena A. Yildirim, Evgeni A. Brazhnik, Kseniya A. Sokolova, and Irina A. Klyuchnikova are affiliated with BIOTROF Ltd., which sponsored this study. The study design, data analysis, interpretation, and manuscript preparation were carried out independently and were not influenced by the sponsor.

References

Publisher’s Note: IMR Press stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.