1 Department of Agricultural Microbiology, Tamil Nadu Agricultural University, 641003 Coimbatore, India

2 Agricultural Research Station, 623707 Paramakudi, India

3 Department of Soil Science and Agricultural Chemistry, Tamil Nadu Agricultural University, 641003 Coimbatore, India

Abstract

Rice is a staple crop worldwide, providing sustenance to over half the global population. The rice microbiome represents the complex interaction between rice plants and their surrounding microbial communities. Plants host various microorganisms in different regions, including the rhizosphere, surface tissues, such as the rhizoplane and phylloplane, and inner tissues (endosphere). These microorganisms engage in diverse interactions with the plants, ranging from beneficial to neutral or harmful. This rhizosphere microbiome plays a crucial role in improving the resilience and sustainability of rice cultivation. The relationship between the rice plants and their microbial communities is imperative for developing farming practices that maximize yields while minimizing biotic and abiotic stresses. Our examination underscores the diverse functions of rhizosphere microbiota within rice farming systems, particularly in nutrient uptake, drought resilience, pest and disease management, and tolerance to salinity. This review describes the different types of rice cultivation methods farmers use worldwide to improve the efficiency of rice production in various agro–ecological contexts. Moreover, the review details how alternate cropping methods influence the rhizosphere functioning of rice and techniques for managing the microbiome function for rice sustainability.

Keywords

- alternate cropping methods

- rhizosphere functioning

- rice microbiome

Globally, the majority of the people eat rice as their staple food. It is grown in highly diverse climates, from wettest to driest regions. In Asia, rice cultivation covers a significantly large share of the total farmland area. This region has a seasonal cycle of dry and wet weather conditions containing various massive river deltas. Rice, a type of annual grass from the Poaceae family, consists of approximately twenty-three species. However, only two—Oryza sativa and O. glaberrima—are commercially significant for cultivation [1]. Today, O. sativa is the primary species cultivated worldwide, whereas O. glaberrima is grown on a more regional scale in select areas of Africa [2]. Rice is nutritious, providing high quantities of complex carbohydrates, vitamins, and minerals [3]. Rice is a tremendous source of vital nutrients for billions of people worldwide.

Plants undergo various challenges throughout their lifespan, encountering various biotic (living organisms) and abiotic (non-living factors) elements. The intricate network involving plants, their surroundings, and every microbe in those habitats is known as the phytobiome [4]. The active interaction between the biotic and abiotic elements within the phytobiome significantly shapes both natural and agroecosystem ecosystems. The microbial communities linked with plants are called the plant microbiome within biotic factors [5, 6]. The microbiome encompasses the microbial community within a particular environment and its collective genome [7, 8]. It offers a more thorough understanding of the microbiological community by considering structural components and genetic makeup.

The health of the host plants is greatly influenced by the microbiological communities, with their effects ranging from positive to negative [9]. Nitrogen-fixing bacteria are instrumental in converting atmospheric nitrogen into ionic nitrogen, facilitating plant uptake [10]. Growth regulators produced by growth-promoting rhizobacteria also stimulate plant growth by producing cytokinins, auxins and gibberellins [11]. The microorganisms also bolster the adaptability of the plants to its environment by strengthening their ability to withstand biotic and abiotic stresses.

Rice is supplied as a primary food source for approximately half of the world’s population, with rice production covering an area of 165 million hectares. In 2021 [12], the world produced 787 million tonnes of paddy, achieving an average of 4.67 tonnes of yield per hectare. In India, where rice cultivation spans 46.4 million hectares, with 2.70 tonnes of average yield per hectare, the production reached 186 million tonnes of paddy [13]. Asia dominates rice production, contributing nearly 90% to the global output, with India being a significant player. Rice is India’s primary staple food crop, vital to many people’s livelihoods. However, challenges like urbanization, the shift of labour migration from agriculture to the non-agricultural sectors, increased labour and input costs, and water scarcity have led to a gradual reduction in rice cultivation [14].

One of the major concerns is the water-intensive nature of irrigated lowland rice, which leads to substantial water wastage. Unfortunately, global rice production is facing a critical situation, and challenges like diminishing cultivated areas, inconsistent produce, decreasing yields, and rising input costs are not unique to India. Consequently, it is essential to grow more rice with fewer resources. Worldwide, there is growing concern over the depletion of water resources, with a rapid decline in groundwater levels. Traditional rice cultivation methods, which heavily rely on water, exacerbate this issue. Long-term use of traditional rice farming methods has been linked to severe degradation of natural resources, lesser productivity, several nutrient deficiencies, groundwater depletion, labour shortage, and elevated cultivation costs [15].

The inability to replenish water sources emphasizes the urgent need for water conservation. Effective water management becomes crucial to ensure a sufficient water supply for crop production. Additional rice must be produced to achieve the United Nations’s Sustainable Development Goal to end global hunger by 2030, ensuring food security and feeding the growing population. Developing technologies that can maintain or increase rice production while reducing water consumption is imperative. Alternative strategies such as alternate wetting and drying, the system of rice intensification, aerobic rice cultivation, and semi-dry rice cultivation are being adopted to enhance water use efficiency without compromising yield.

There is a growing emphasis on modifying water management practices to address the challenges associated with rice cultivation, particularly regarding water consumption and environmental impact. Different types of rice cultivation are followed across the globe, like direct seeded rice, the system of rice intensification (SRI), upland rice, and semi-dry rice cultivation.

SRI was developed by Henri de Laulani, a priest from France, in the 1980s in Madagascar [16]. His objective was to establish sustainable agricultural practices that could enhance productivity, optimize the utilization of resources like capital and labour, reduce input costs, and minimize water requirements. This approach involves harmonizing plant, light, water, and soil elements to unlock the plant’s full potential, which might remain unrealized when improper techniques are employed [17]. The SRI is an alternative to enhancing rice yield while reducing water consumption. Diverging from traditional rice cultivation methods, SRI involves distinct practices in terms of water utilization, labour involvement, and seedling planting methodologies [18].

In contrast to wetland cultivation, alternate wetting and drying are

incorporated in the rice fields in SRI [19]. Numerous research studies and

demonstration experiments conducted across various tropical countries have shown

that SRI improves productivity, enhances resource efficiency, reduces water

usage, and mitigates greenhouse gas emissions compared to traditional rice

cultivation methods [20, 21, 22]. Direct-seeded rice cultivation requires 75–100 kg

of seeds per hectare, while traditional transplanted rice uses 40–60 kg per

hectare. In contrast, the SRI only requires 8–12 kg of seeds per hectare, which

involves planting a single seedling per hill with wider spacing (25 cm

SRI adoption has documented higher yield outputs, between 6 to 8 tons per hectare, coupled with 25% of water savings. This method also generates robust grains, weighing approximately 100–110 kg per bag, and produces high-quality grains with a more pronounced aroma [24, 25]. Similar positive trends have been observed in Madagascar and China. In Madagascar, reported increases in yields and reductions in water usage fell within the range of 25% to 50% [26]. Consequently, SRI presents notable advantages over conventional approaches, especially in subsistence farming settings. Farmers in numerous countries have successfully boosted the yields of their existing rice varieties by adopting SRI strategies [20, 21, 27, 28].

The population of bacteria, fungi, and actinobacteria significantly increased in the soil due to the adoption of SRI techniques. Specifically, the SRI methods supported higher bacteria, fungi, and actinobacteria populations, measuring 7.20, 5.22, and 4.62 log cfu (colony-forming units)/gram of soil. On the contrary, traditional wetland cultivation showed lower populations of these microbial groups [29]. Compared to traditional wetland rice, SRI promotes more significant microbial populations by enhancing root exudation, increasing organic matter from weed incorporation, and creating more aerobic soil conditions [30]. In traditional wetland rice systems with continuous flooding, the roots suffer from oxygen deprivation, leading to plant deterioration.

In contrast, the alternate wetting and drying approach used in SRI prevents root degradation by maintaining adequate oxygen levels in the soil [31]. Rice plants grow more profoundly and extensively when they encounter periodic water scarcity [32], which helps enhance their ability to access nutrients and moisture from deeper soil layers. Several factors contribute to higher beneficial microbial counts and enhanced biochemical processes in SRI. These include reducing transplant shock by using young seedlings, employing upland nurseries, maintaining lower plant population density, promoting aerobic soil conditions, actively aerating the soil, and increasing soil organic carbon levels in the rhizosphere of rice plants.

A case study was conducted in Mahbubnagar district in Andhra Pradesh, where the SRI cost of cultivation was reduced by 58% per acre compared to traditional rice cultivation [33]. In West Bengal, India, a case study was conducted, and Paddy yields were higher in SRI by 32%, 67% of net returns, and an 8% reduction in labour inputs compared to conventional rice cultivation [28]. In Odisha, India, the allotted area for SRI increased from 1.14 acres in 2013–14 to 1.22 in 2015–16. 74% of farmers believed that using SRI improved the health of their soil, while just 42% believed the SRI increased water use efficiency [34].

Unlike transplanting, direct seeding initiates a rice crop by directly sowing seeds in the main field. After the germination and establishment of seedlings are completed, the crop can be continuously inundated, following water management practices similar to those of transplanted rice cultivation. As an alternative, crops may depend on rainfed conditions, with the upper layers of soil fluctuating between aerobic and anaerobic states. Before the late 1950s, the most common method used in developing nations to establish rice was directly sowing seeds in the field [35, 36].

Using conventional techniques, pre-germinated seeds are put into standing water, eventually receding to establish water-seeded rice. To ensure anchoring at the soil surface, seeds need to be heavy enough to sink beneath the surface of the standing water. Water seeding is a traditional method used in Asia when early flooding happens and the field cannot be drained. Only a few traditional rice varieties from Thailand, Indonesia, and Vietnam can use this technique. Modern water seeding techniques include aerial sowing with the United States and Australian aircraft. Tractor-mounted seeders are used for seed broadcasting in Italy. Motorized blowers are used in Malaysia. The most often utilized technique in temperate rice zones is aerial water-seeding [37]. Aerial seeding represents a cutting-edge method in rice cultivation that utilizes technology to improve efficiency and promote sustainability in agriculture. Compared to mechanical direct seeding and transplanting methods, multifunctional unmanned aerial vehicles (mUAVs) demonstrated efficiencies in seed sowing that were 2.2 times and four times greater, respectively. Additionally, these methods reduced labour costs by 68.5% and 82.5% [38].

When direct-seeded rice was introduced in South Asia, it reduced almost 40% of the water used and resulted in a 9% increase in grain output compared to conventional flood irrigation techniques [39]. A case study was carried out in Punjab, and the results showed that Sultanpur Lodhi block had greater grain yield than Kapurthala district and other blocks because more farmers in Sultanpur adopted Direct seeding of rice (DSR) cultivation [40].

“Aerobic rice” term has been introduced by the International Rice Research Institute (IRRI) to describe a type of high-yielding rice that is cultivated in non-flooded conditions, in non-puddled and aerobic soil. Aerobic rice farming is a contemporary method of cultivating rice, employing robust soil with efficient water retention and well-suited, high-yielding varieties directly sown in dry conditions [41]. This innovation helps in significantly conserving water resources. In China, aerobic rice cultivation has led to a remarkable 55–56% reduction in water usage compared to the traditional transplanting method, resulting in 1.6–1.9 times higher water productivity [42].

The soil remains aerobic throughout the growing season in the aerobic rice production system, and additional irrigation was supplied whenever needed. Cultivars chosen for this method are adapted explicitly to aerobic soils, exhibiting higher yield potential than traditional upland cultivars [43]. In response to changing agricultural dynamics, India has introduced approximately twenty-two varieties and two hybrids designed for aerobic conditions [41]. CR Dhan (Pyari), the first aerobic rice variety grown in the uplands of Orissa, India, has a yield potential of 6.9 t/ha. In Bihar and Chhattisgarh, CR Dhan 201 has a yield potential of 7.14 t/ha. CR Dhan 209 (Priya), also grown in Orissa, can yield up to 7.84 t/ha. In Maharashtra and Madhya Pradesh, CR Dhan 203 (Sachala) has a yield potential of 6.59 t/ha. Lastly, CR Dhan Srimati, cultivated in Orissa, yields 7.08 t/ha [41]. According to a case study, the yield of aerobic rice varieties in the North China Plain ranged from 3.5 to 5 t/ha, wherein the water intake was reduced by 50% compared to the wetland [44].

Upland rice can be grown in dry, hilly locations or places with steady rainfall and sufficient irrigation, providing an alternative to traditional rice cultivation [45]. Shifting to upland rice systems has benefits beyond stabilizing and increasing food output. It can improve water use efficiency, mitigate environmental issues associated with continually flooded paddies [46] and promote overall agricultural sustainability. The IRRI and other organizations have developed many upland rice cultivars. Chinese researchers have also produced numerous water-efficient, drought-resistant upland rice varieties. Especially with Japonica-type upland rice, China has reached globally competitive levels, with yield and quality unavailing paddy rice cultivars [47].

Upland rice cultivation has been gaining more attention lately, as the current varieties of rice with high yields have led to increased genetic vulnerability, reduced irrigation water availability, and disease resistance have been broken down due to intensive farming practices. High-yielding and irrigated cultivars have been primarily responsible for the recent global advancements in rice production developed through scientific research and modern technologies. Most research on upland rice has not been published. Thus, these advancements in upland rice yields have not had much of an impact. Upland rice was grown on 14 million hectares, accounting for 11% of global rice production. It is crucial for cropping systems that lack irrigation infrastructure and require lower production costs [48]. In Brazil, upland rice typically yields an average of 2 t/ha, whereas irrigated rice achieves a higher average of around 5 t/ha [48]. In Nigeria, productivity per unit area has remained at about 1.5 t/ha, even though there is an increase in rice production due to expanded cultivation [49]. Malaysia has an estimated rice cultivation area of 672,000 ha, with an average rice production of 3.66 t/ha. Upland rice was grown approximately 165,888 hectares in Malaysia, with mean yields ranging from 0.46 to 1.10 tonnes per hectare [50]. Bangladesh, Indonesia, and the Philippines are the primary regions where upland rice is cultivated, but the yields are notably low, averaging around 1 t/ha, and exhibit high variability [51].

Semi-dry rice cultivation is practised in several parts of Tamil Nadu, India, including Paramakudi, Sivaganga, Ramnad, and Tuthukudi districts. The paddy seeds will be sown as a direct seeded crop in September, anticipating the monsoon rain and channel irrigation. The seedlings will emerge and stand like dryland crops for up to 35–40 days. Then, the field will be transformed into a wetland system, and a water level of about 10 cm will be maintained until the panicle formation stage. Nutrient and weed management will be adopted after the wetland formation. This system, called “semi-dry rice cultivation”, is practised in low rainfall districts of Tamil Nadu, where there are normal and coastal saline soils. Semi-dry rice cultivation helps ensure food security in regions facing monsoon failures, unpredictable water resources, and soil salinity. In addition, Coastal saline soils in these regions are linked to various complex issues, including poor sanitation, waterlogging, the formation of impermeable clay pans, and the risk of sea inundation [52]. In Tamil Nadu state of India, semi-dry rice cultivation is practised with specific rice varieties such as PMK-1, PMK-2, PMK-3, and Anna-4.

A thin layer of soil surrounding the root system, called rhizosphere, hosts a diverse community of microorganisms known as rhizosphere microorganisms [53]. Through a process called “rhizosphere deposition” [54], the rhizosphere can influence plant growth and respond to root exudates in the surrounding soil. Through rhizosphere deposition, plants contribute carbon sources to support the growth of microbes and influence the community composition [9].

The intricate interaction occurs between the plants and microorganisms of the rhizosphere region surrounding the plant roots [55]. These complex root-microbe relationships are vital for plant growth, health, and adaptability [56]. The rhizosphere is the primary site for the plants to interact with native soil microorganisms. It is an interface for cooperation with the most significant microbial diversity present in the soil. Roots secrete various organic compounds, including carbohydrates, amino acids, organic acids, vitamins, and phenolics, as exudates while storing polysaccharide mucilage in the epidermal cells. This nutrient-rich environment attracts a diverse array of microorganisms in the soil, creating a functioning micro-ecosystem through their interactions [57]. The rhizo-microbiome facilitates nutrient acquisition, stress tolerance, pest and disease resistance, and yield for its host plant [58]. In addition, the root system, enriched with microbial interactions, is a crucial factor for the health and fertility of the soil, as it improves the soil’s biological activity and structure [59]. The external factors such as water, soluble chemical molecules, temperature, and agricultural practices, including tillage, nutrient management, cropping systems, cultivation methods, soil and water conservation methods, and cultivars of the crops influence the structural functioning of the rhizosphere microbiome [60]. Understanding the rhizosphere microbiome of each crop plant in the future is essential for sustaining their productivity.

Plant-associated microorganisms are essential for improving plant nutrition. Symbiotic relationships of plants with arbuscular mycorrhizal fungi (AMF) and Rhizobium have been extensively investigated in molecular processes governing nutrient acquisition [7]. Additionally, non-symbiotic and associative symbiotic bacteria such as Pseudomonas fluorescens, Azoarcus spp., Azospirillum spp., Bacillus spp., Paenibacillus spp. that promote plant growth can either increase the bioavailability of minerals that are otherwise insoluble or enhance the root system architecture of host plants. This improvement in root structure enhances the plant’s ability to explore and acquire water and minerals [61]. Azospirillum brasilense plays a crucial role in nitrogen fixation, which can significantly enhance plant dry weight [62]. Bacillus megaterium species exhibit strong phosphorus-solubilizing capabilities [63], while Bacillus and Pseudomonas strains contribute to increased plant zinc accumulation [64]. Microorganisms can solubilize phosphates, as reported in the phyllosphere of rice in Kenya [65]. Plant-associated microbiota is essential for activities including solubilization, mineralization, and excretion via iron-chelating siderophores that increase plant accessibility to nutrients like iron and inorganic phosphate. In situations where inorganic phosphate is limited, plants depend on microbial cooperation, including arbuscular mycorrhizal fungi (AMF) and their symbiotic endophytes, to meet their fundamental nutrient requirements, particularly for phosphate [66]. Rhizosphere microbes, AMF, and endophytes help plants obtain nutrients from the soil by solubilizing nutrients like sulphur, potassium, calcium, iron, zinc, and phosphorus [67].

It has been found that several well-known genera of the root microbiome in maize, wheat, rice, and legumes contribute to the uptake of micronutrients and stimulate the formation of roots, hence promoting plant growth and development. These include Azospirillum, Achromobacter, Azotobacter, Bacillus, Burkholderia, Citrobacter, Chryseobacterium, Streptomyces, Gluconacetobacter, Herbaspirillum, Klebsiella, and Pantoea [68]. Under field conditions, the bioavailability of iron, copper, manganese, and zinc in Zea mays is improved by the presence of Azotobacter chroococcum and Azospirillum brasilense [69]. Similarly, Bradyrhizobium japonicum enhances the uptake of copper, zinc, iron, and manganese in cowpea pods [70]. Although iron cannot enter plant cells directly, not even with transporters, siderophores made by endophytes help to uptake soil iron [22]. Specific root endophytes like Azoarcus, Herbaspirillum, Acetobacter, and Diazotrophicus are involved in nitrogen fixation. Some nitrogen-fixing endophytic microbes in rice, such as Firmicutes, Gammaproteobacteria, and Actinobacteria, can fix atmospheric nitrogen [22].

Drought is one of the most common abiotic factors diminishing crop productivity and yields globally. Scientists have isolated endophytic and rhizosphere bacteria and fungi adapted to drought from xerophytic plants or arid habitats. These microorganisms have been shown to improve the growth of staple crops like rice, wheat, sorghum and millet when water availability is severely limited [71]. There is ample evidence that microorganisms intimately linked with the plant roots can facilitate plants’ continued growth, fitness and performance under drought conditions [72].

Though root-associated microbes demonstrate the potential to relieve drought pressures in crops, there have been no systematic studies characterizing the identity and plant growth promoting the capacity of microbes inhabiting the rhizosphere and roots of upland rice under drought conditions. In vitro and in vivo assays on plant growth-promoting and drought-mitigating traits in upland rice isolates have revealed species from genera Bacillus, Pantoea, Serratia, Flavobacterium, Penicillium, Pseudomonas, Trichoderma Klebsiella, and Talaromyces, demonstrate the highest prevalence of these beneficial characteristics [73]. Known fungi and plant growth promote bacteria for various xerophytes and crops, including Bacillus thuringiensis and Piriformospora indica, affiliated with these genera [74]. Notably, most bacteria do not confer any growth-promoting impacts on rice seedlings subjected to drought stresses like natural moisture deficiency or extreme heat (with temperatures approaching 46.7 °C—typical of tropical climates). Despite many lab-screened bacteria demonstrating plant growth potentials, actual field benefits under water-limited conditions are lacking. However, some plant growth-promoting bacteria can generate exopolysaccharides that improve moisture retention in soil and stabilize soil aggregates—relevant adaptations for arid agroecosystems [75].

Additionally, laboratory inoculations with plant growth-promoting bacteria (PGPB) profusely proclaim efficacy under controlled settings. However, the mechanisms conferring drought tolerance benefits remain undiscovered and unproven in real-world crop systems [76]. Many studies struggle to conclusively pinpoint specific PGPB traits that directly translate to enhanced plant performance under water-deficient conditions in the field (e.g. [72]). Hence, elucidating the mechanisms behind how root microbes modulate drought tolerance in crops and gauging their efficacy under realistic water-limited field conditions bears great potential for bolstering resilience to drought in vulnerable rain-fed agricultural systems [72]. Thus, it is unassailable to explicate the molecular mechanism and mode of action of the plant root-microbiome interaction system under drought stress. Using high-throughput sequencing, examining the root microbial populations in various rice niches has become more common in recent years. Thus, combining metagenomics, plant metabolomics, and other technical techniques is required to investigate the actual community structure of the root system.

Salinity is a concern to coastal areas in the current climate change context and rapidly limits the usability of agricultural fields. By 2050, it is predicted that salt will consume more than half of the arable land [77]. Soil salinity significantly disrupts soil structure and has pronounced influences on agriculture productivity [78]. The soil is classified as salt-affected when its electrical conductivity (EC) is more than 4.0 dSm-1 [79]. Excessive salinity disrupts the ionic balance within plants, increasing the uptake of Na+ while decreasing the K+ and Ca++ ions uptake, leading to ion toxicity in plant tissues [80]. This disruption adversely affects crop productivity by inhibiting photosynthesis through the accumulation of Cl– ions [81] and induces hyperosmotic stress, ultimately causing dehydration and adversely affecting crop productivity [82]. Salinity stress is particularly intricate among abiotic stresses as it induces imbalances in ionic, osmotic, and redox processes [83].

Salinity stress substantially alters plant morphology, physiology, biochemical compounds, and yield [84]. Numerous molecular events have been identified as triggered by salinity stress [85]. Plants exhibit varying responses to salinity stress, classifying them into two major groups: glycophytes, susceptible to salinity stress, and halophytes, which can withstand salinity stress. Rice falls into the category of glycophytes, making it inherently susceptible to salinity stress and prone to detrimental effects. Notably, rice, being one of the most crucial food crops globally [86], experiences significant yield losses due to salinity stress. The soil with electrical conductivity of 3.5 and 7.2 dS/m recorded 10% and 50% yield losses in rice, respectively [79].

Addressing the challenge of salinity stress requires the development of rice cultivars that are not only high-yielding but also tolerant to salt [87]. In 1939, Sri Lanka introduced the first salt-tolerant variety named Pokkali [88]. Other halotolerant rice cultivars include Oryza coarctata, BRR1dhan67, G1710, Nonabokra, SR26B, Getu, G58, Dudheswar, Damodar, FL478, Dasal, Talmugur, Nonasail, Bhutnath [89]. The development and adoption of these salt-tolerant varieties play a vital role in ensuring stable rice production in saline-prone areas.

Research has shown that the rice reproductive stage is highly susceptible to salinity, with 3 dSm-1 of electrical conductivity (EC) being enough to cause a significant reduction in paddy production [87]. In response to saline conditions, plants employ both ‘functional adaptation’ and a ‘sensing and signalling mechanism’. Functional adaptation primarily involves stomatal regulation, osmotic adjustment, ion homeostasis, and maintaining nutrient balance [90, 91].

Beneficial microorganisms are crucial in improving the plant’s ability to withstand salt stress. Microbes use various mechanisms to mitigate the effects of salinity on plants. For example, some microbes produce exopolysaccharides (EPS) that help maintain proper Na+/K+ ratios in plant tissues [92]. Important bacterial genera, including Bacillus, Halomonas, Burkholderia, Pseudomonas, Enterobacter, and Microbacterium, secrete exopolysaccharides (EPS) when conditions in the soil become unfavourable, such as high salinity [93].

Even when soil salinity is high, beneficial plant-growth-promoting rhizobacteria (PGPR) bacteria exhibit various plant growth-promoting traits that help the plants tolerate salt stress. These traits include secreting exopolysaccharides (EPS), producing auxins like IAA, solubilizing phosphate and potassium nutrients, producing siderophores, fixing nitrogen, and generating hydrogen cyanide and ammonia. Through these mechanisms, the PGPR bacteria improve salt tolerance signalling pathways, osmolyte production, antioxidant activity, nutrient acquisition, and phytohormone signalling in plant hosts - all of which combat the damaging effects of salt stress [94]. Applying salt-tolerant PGPR has been documented to increase rice crop yields in coastal areas with high soil salinity [92]. Specific bacterial genera, including Bacillus, Klebsiella, Agrobacterium, Streptomyces, Ochromobacter, Enterobacter and Pseudomonas, have been shown to boost productivity for various crops under salt stress conditions [95].

In rice plants, salt-tolerant microbes can stimulate alternative oxidase-based defence mechanisms, accumulate various osmolytes, improve seed germination and early seedling growth, and modulate gene expression related to salinity stress tolerance [95]. Specific bacterial strains that have been documented to exert positive effects on the grain yield and development of rice plants affected by high salinity include Bacillus subtilis, B. aryabhattai, B. tequilensis Microbacterium esteraromaticum, and Pseudomonas multiresinivorans [86].

Research shows that in rice, the halotolerant PGPR strain B. amyloliquefaciens NBR1SN13 can overcome severe salinity effects by altering gene expression patterns of both the rhizosphere microbial communities and rice leaf tissues [96]. Beyond PGPR, arbuscular mycorrhizal fungi (AMF) also play an essential role in salinity stress alleviation in rice. AMF help rice endure salt exposure by facilitating water uptake, ion homeostasis maintenance, bolstering photosynthetic and carbon fixation capacity, reducing stem translocation of excess sodium, and promoting absorption of adequate potassium [97].

Insects and pathogenic microorganisms infect crop plants, hampering productivity, growth, and robustness. However, research indicates that the plant root microbiome is a valuable source of diverse bioactive compounds with potential applications bolstering plant defences [77]. Analyses of phyllosphere microbes—those colonizing the aerial parts of plants—have revealed that many bacteria from the Phylum Firmicutes produce volatile organic compounds that can protect crops against fungal and bacterial phytopathogens [98].

The plant root microbiome can confer protection against insects, pathogens and

herbivores by eliciting antimicrobial activity or induced systemic resistance

(ISR). Specific compounds produced by beneficial root-associated endophytic

bacteria have been shown to trigger ISR that primes plant immune responses. These

include antibiotics, bacterial flagella, jasmonic acid, lipopolysaccharide

molecules, siderophores, salicylic acid, and N-acyl homoserine lactones [99].

B. subtilis enhanced the activity of peroxidase, polyphenol oxidase and

superoxide dismutase against Megnaporthe oryzae in rice [100].

Pseudomonas fluorescens and P. clororaphis are the primary

producers of phenazines and have been demonstrated to be excellent antagonists of

fungal plant diseases [101]. R. solani growth was suppressed by volatile

organic compounds (VOCs) released by rhizobacterial isolates of Serratia

odorifera, S. plymuthica, Stenotrophomonas rhizophila,

S. maltophilia, P. fluorescens, and P. trivialis [102]. Collimonas pratensis Ter 91 generates a minimum of four

monoterpenes, among which

Actinobacteria belonging to the order Actinomycetales, especially those from the prolific genus Streptomyces, have been extensively analyzed regarding their capacity to produce antimicrobial compounds guarding plants from pathogens. These filamentous, gram-positive soil microbes can synthesize and export an array of bioactive metabolites with anti-infective activities against plant pathogenic fungi, oomycetes and bacteria. Such actinobacterial antimicrobials include indole-sesquiterpene compounds, the munumbicins, coronamycin and kakadumycins secreted by various Streptomyces species [77]. Additional research has shown that siderophores produced by certain microbes can elicit ISR in plants, bolstering their biocontrol activity against pathogens. Specifically, particular endophytic Methylobacterium strains capable of secreting siderophores have successfully restricted the growth of the harmful pathogen Xylella fastidiosa, the agent responsible for chlorosis disease in citrus [105] (Fig. 1).

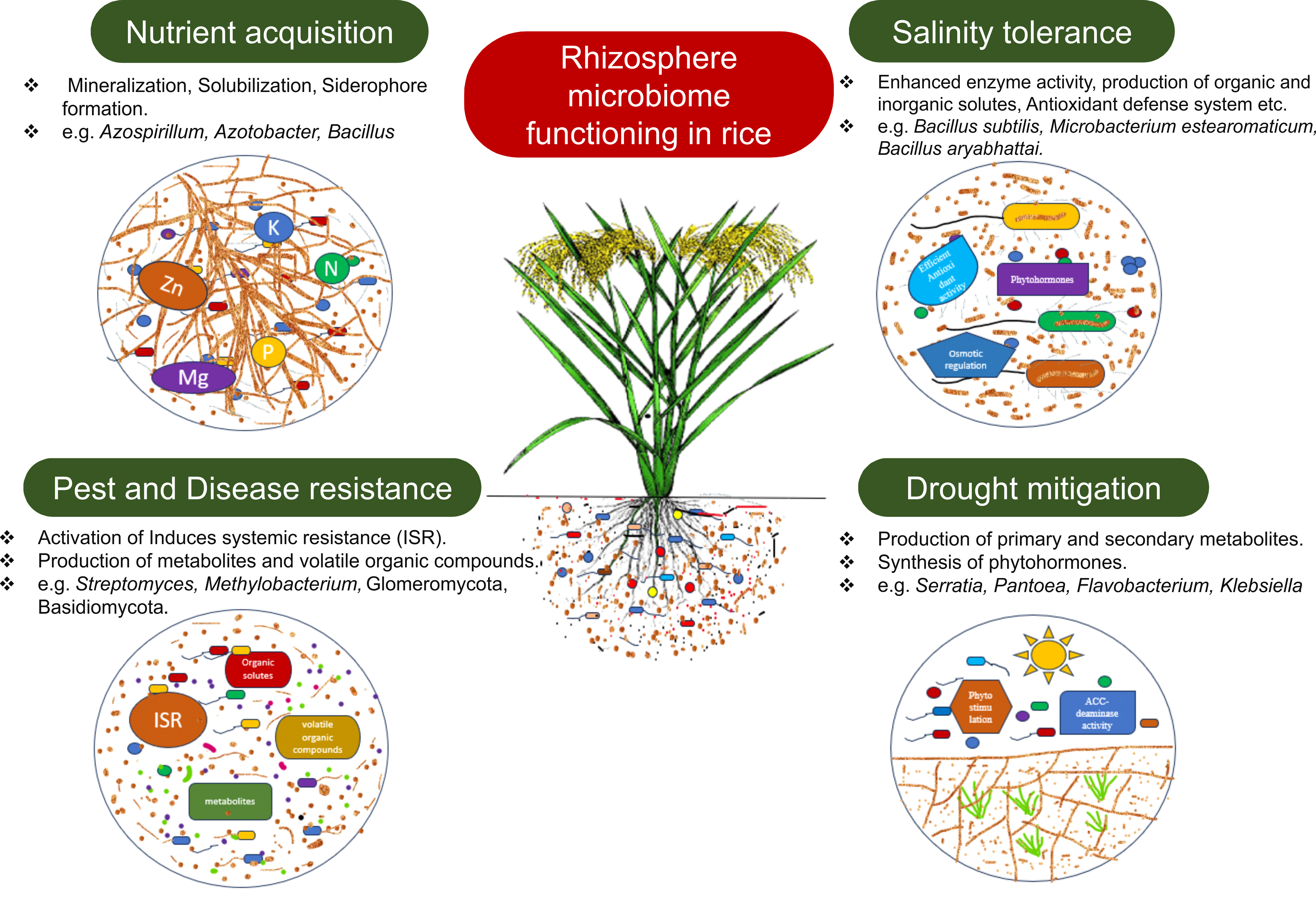

Fig. 1.

Fig. 1.

The possible impacts of different cropping methods on plant growth promoting rhizobacteria and their benefits. ACC, 1-aminocyclopropane-1-carboxylate. Created the image using CoralDRAW X7 (Corel, Ottawa, Ontario, Canada).

Plants establish direct contact with a vast array of microorganisms in the soil. The well-established understanding is that a mutualistic relationship exists between plants and microorganisms [106]. Notably, the roots of the rhizosphere release carbon metabolites that foster the growth and activities of microbes [107]. Reciprocally, rhizosphere microbes play an essential role in supporting plants by providing nutrients, producing growth-stimulating hormones, suppressing plant pathogens, and improving tolerance to various agroclimatic stresses such as drought and salinity [108]. This mutualistic interaction between plants and microorganisms is indispensable for ecology’s functions in terrestrial ecosystems [106].

The root structure of rice can be divided into three spatial compartments: the endosphere, rhizoplane, and rhizosphere [109]. It sets rice apart in its cultivation in flooded paddy soils throughout most growth stages, with the roots releasing oxygen through aerenchyma, creating oxic zones in the rhizosphere around the roots, surrounded by anoxic bulk soil [110]. Aerobic, anaerobic or facultative anaerobic microbes are colonized in between oxic and anoxic conditions [111, 112]. The presence of methanogens in the rhizosphere soil and bulk soil makes paddy fields a significant source of biogenic methane release, contributing approximately 5 to 19% to the global methane budget [113].

Addressing the tasks posed by a growing world population and changing climate, rice agriculture faces the dual task of achieving high yields with limited cultivation areas while mitigating CH4 emissions from paddy soils. Recognizing the profound impact of microbial diversity on soil and plant productivity [114, 115] helps in effectively adapting sustainable productivity in paddy ecosystems. However, current research lacks comprehensive studies on the microbiomes specific to the endosphere, rhizoplane, and rhizosphere.

Microbial communities present in the rice microbiome, particularly bacterial communities, exhibit notable diversity and dynamic characteristics. These structures are predominantly influenced by factors associated with the soil and the plant, including geographical location, soil type, and the rice genotype [62, 109]. Notably, changes in these factors can impact soil conditions relevant to microbial growth and expansion, such as soil pH and root exudation pattern, leading to variations in the structure of rhizosphere microbial communities. Moreover, agricultural practices, such as cultivation methods, drainage, and different growth stages, also have a significant role in shaping the rhizosphere microbiome of rice [109, 116].

Soil microbes exhibit distinct community structures in various soil types and under different cultivation methods, adapting to changes in their living environment [117]. While considering paddy cultivation, mechanical transplanting and direct seeding have significantly enhanced the abundance and richness of soil microorganisms, leading to alterations in the soil microbial community, where they have enriched soil microbial community and diversity compared to traditional transplanting methods [118].

Under SRI cultivation, there was an 8% increase in bacterial population, a 12% increase in fungal population, and a 20% increase in actinobacteria compared to conventional transplantation and flooding methods [29]. To gain better insight into the microbial community dynamics explicitly associated with upland rice ecotypes, various upland rice genotypes were selected—including both local Chinese cultivars and international varieties—grown in Xishuangbanna in southwest China for analysis. Several previous studies have examined differences among root microbial communities of different irrigated rice varieties. These have identified specific bacterial groups like Kosakonia, Flavobacterium, Klebsiella, Microbacterium, Pantoea, Serratia, and certain fungal groups as commonly isolated from the roots of most rice cultivars [119, 120].

Gemmatimonadetes, actinobacteria, and proteobacteria were significantly increased in direct-seeded rice compared to transplanted rice. The abundance of Actinobacteria, Acidobacteria, Patescibacteria, and Verrucomicrobia is relatively higher in direct-seeded rice when compared to transplanted rice [121]. The study was carried out in Western Burkina Faso, between the rainfed and irrigated lowlands of two rice growing systems. Agricomycetes, Sordariomycetes, and Microbotryomycetes are the indicator taxa that are present in the irrigated areas, while Chytridiomycetes, and Ustilagomycetes, Dithideomycetes, and Saccharomycetes are present in the rainfed lowlands [122].

Rice ecotypes, in association with environmental conditions, contribute to the enrichment of the root microbiome [72]. The distinction between upland and lowland environments significantly influences the composition of the root microbiome in different ecological rice varieties, with the environmental effect surpassing that of the rice variety itself. In upland environments, the root microbiome mainly consists of Serratia, Ascomycota and Enterobacteriaceae. Conversely, the transition of lowland rice ecotypes from paddy fields to uplands results in the specific enrichment of certain Gram-positive microbes like Actinobacteria and Thermoleophilia [73].

Based on 16s rRNA sequencing, the bacterial communities in the rhizosphere microbiome of rice are significantly influenced by alternate cropping methods like SRI, direct seedling of rice (DSR), and wetland rice cultivation. In DSR, Proteobacteria dominated the rhizosphere highly, compared to SRI and wetland cultivation. Bacteroidetes are significantly higher in SRI than in DSR and wetland cultivation. Choloroflexi was significantly higher in wetlands than DSR and SRI [123]. The impacts of different cropping methods are summarized in Table 1 (Ref. [124, 125, 126, 127, 128, 129, 130, 131, 132, 133]).

| Cropping method | Consequences | References |

| System of Rice Intensification | Increase in soil dehydrogenase activity, microbial biomass, soil enzyme activity, available N and P in soil | [124, 125] |

| Direct seeded rice | High bulk density, organic carbon, soil moisture content, soil enzyme activity, and microbial community | [126, 127] |

| Aerobic rice | An increase in soil pH | [128, 129] |

| Diminish the natural supply of phosphorus (P) | [130] | |

| Soil dehydrogenase activity is more | [125] | |

| Upland rice | The redox potential is increased | [131] |

| Greater rate of soil organic matter (SOM) decomposition | [132] | |

| Semi-dry rice | Soil hydraulic conductivities were relatively small, and bulk density decreased | [133] |

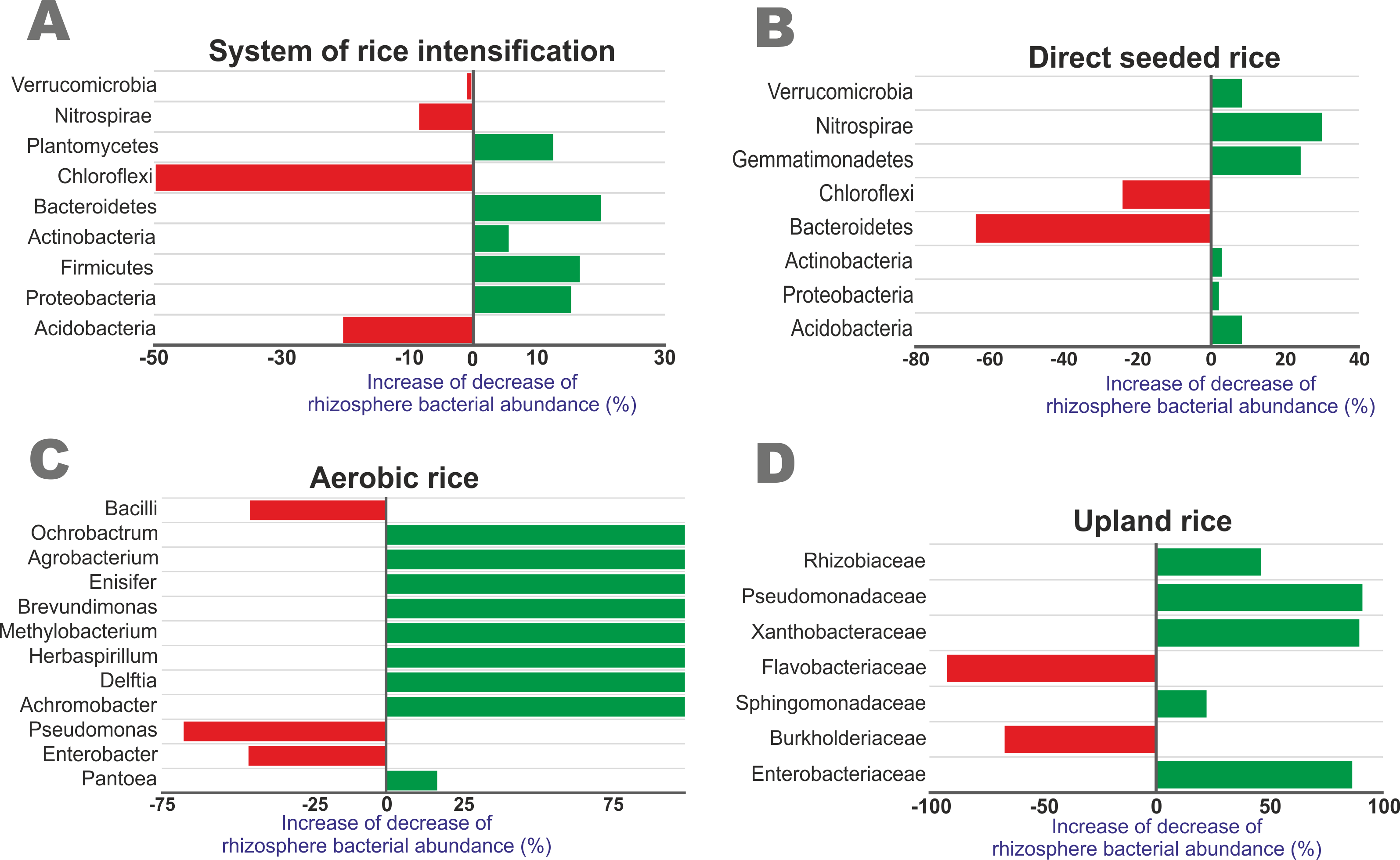

The rhizosphere microbiome, as influenced by different cropping methods in comparison with traditional wetland rice cultivation, was presented in Fig. 2 (Ref. [121, 123, 134, 135]). The increased percentage of bacterial abundance of Acidobacteria, Actinobacteria and Proteobacteria in SRI was higher when compared to DSR. Nitrospirae had a higher decrease in DSR than SRI. Gemmatimonadetes was highly increased when compared to other genera in DSR. Aerobic rice was highly reduced by Enterobacter and Bacilli when compared to wetland cultivation. Pseudomonadaceae, Enterobacteriaceae, and Xanthobacteraceae have a higher increase in upland rice than in wetland cultivation. These studies underscore that the rice rhizosphere microbiome had a greater influence on cropping methods.

Fig. 2.

Fig. 2.

Increased or decreased bacterial abundance in rice rhizosphere as influenced by different cropping methods compared to traditional wetland cultivation. (A) System of Rice Intensification, (B) Direct seeded rice, (C) Aerobic rice, (D) Upland rice. The bacterial abundance data of each cropping system were obtained from [121, 123, 134, 135].

The rhizosphere microbiome plays a vital role in enhancing the resilience and sustainability of rice cultivation, positioning it as a vital tool for addressing the challenges posed by diverse agro-climatic conditions. Research shows that various rice cultivation practices—such as irrigated, upland, rainfed lowland, and direct-seeded rice—significantly influence the composition of the rice microbiome. This microbiome adapts to different practices and geographical locations, enabling rice plants to thrive under various climatic conditions. The rhizosphere microbiome enhances nutrient acquisition through plant growth-promoting rhizobacteria (PGPR), including nitrogen-fixing bacteria, phosphate-solubilizing microorganisms, potash-releasing bacteria, and zinc-solubilizers. These microbes increase nutrient availability and reduce dependence on synthetic fertilizers. Additionally, the rhizosphere microbiome is pivotal in mitigating environmental stresses like salinity and drought, while certain microorganisms act as biocontrol agents against pests and diseases. The rhizosphere’s PGPR stimulates root development, produces growth hormones, accelerates plant growth, and ultimately increases crop yield.

The key challenges in studying and managing the rhizo-microbiome in different rice cultivation include the complexity and diversity of microbial communities, limited understanding of their specific functions, and variability in environmental conditions across regions. Inconsistent sampling methods, high costs, and limited access to advanced technologies (e.g., metagenomics, metatranscriptomics, and metabolomics) further challenge research efforts. The unpredictable performance and establishment of microbial inoculants and the effects of synthetic chemicals hinder the adoption of microbiome-based solutions. Additionally, the lack of long-term studies, scalability issues, and limited awareness among farmers about microbiome management complicates its integration into rice farming practices, particularly in resource-poor regions. The key questions for the future direction in rice microbiome research include: (1) How does the composition and functioning of rhizosphere microbiome differ among different cultivation methods? (2) Which microbial taxa abundance across the cultivation methods are responsible for impacting rice’s health and nutrient acquisition? (3) What management strategies are specifically needed for each rice cultivation method to optimize the rhizosphere function towards yield sustainability? (4) What strategies can we adopt to develop plant-growth-promoting rhizobacteria (PGPR)-based inoculants to enhance the nutrient uptake of rice across the cultivation methods?

Tailored strategies are needed to sustain the rhizosphere microbiome and enhance its contribution to growth and yield across different rice cultivation methods. Synthetic microbial community inoculants, conservation tillage, judicious use of organic amendments, and reduced reliance on synthetic chemicals are proven techniques. By implementing these strategies, rice farmers can optimize the rhizosphere microbiome’s function, improving nutrient acquisition, greater stress resilience, enhanced growth, and higher yields across different cultivation methods.

During the preparation of this work, the authors used ChatGPT to check the spelling and grammar of the manuscript. After using this tool, the authors reviewed and edited the content as needed and take full responsibility for the content of the publication.

ED and DB outlined the review. ED and DB wrote the original draft. SeM, SuM and RA contributed to the literature search. SeM, SuM and RA provided oversight, literature search, and direction for the manuscript. All authors have participated sufficiently in the work and agreed to be accountable for all aspects of the work. All authors read and approved the final manuscript. All authors contributed to editorial changes in the manuscript.

Not applicable.

Not applicable.

This work was supported by TNAU Research Project entitled Biostimulants Efficacy Testing Structure (BETS) (BMGF/BETS/DR/CBE2023/R001) funded by Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation, USA, through a student fellowship to ED.

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

Publisher’s Note: IMR Press stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.