1 Master Program in Process Design and Management, School of Engineering, Universidad de La Sabana, 140013 Chía, Colombia

2 Bioprospecting Research Group, School of Engineering, Universidad de La Sabana, 140013 Chía, Colombia

3 Chemical Engineering Program, School of Engineering, Universidad de La Sabana, 140013 Chía, Colombia

4 Doctoral Program of Biosciences, School of Engineering, Universidad de La Sabana, 140013 Chía, Colombia

Abstract

Azo pigments are widely used in the textile and leather industry, and they generate diverse contaminants (mainly in wastewater effluents) that affect biological systems, the rhizosphere community, and the natural activities of certain species.

This review was performed according to the Systematic Reviews and Meta Analyses (PRISMA) methodology.

In the last decade, the use of Streptomyces species as biological azo-degraders has increased, and these bacteria are mainly isolated from mangroves, dye-contaminated soil, and marine sediments. Azo pigments such as acid orange, indigo carmine, Congo red, and Evans blue are the most studied compounds for degradation, and Streptomyces produces extracellular enzymes such as peroxidase, laccase, and azo reductase. These enzymes cleave the molecule through asymmetric cleavage, followed by oxidative cleavage, desulfonation, deamination, and demethylation. Typically, some lignin-derived and phenolic compounds are used as mediators to improve enzyme activity. The degradation process generates diverse compounds, the majority of which are toxic to human cells and, in some cases, can improve the germination process in some horticulture plants.

Future research should include analytical methods to detect all of the molecules that are generated in degradation processes to determine the involved reactions. Moreover, future studies should delve into consortium studies to improve degradation efficiency and observe the relationship between microorganisms to generate scale-up biotechnological applications in the wastewater treatment industry.

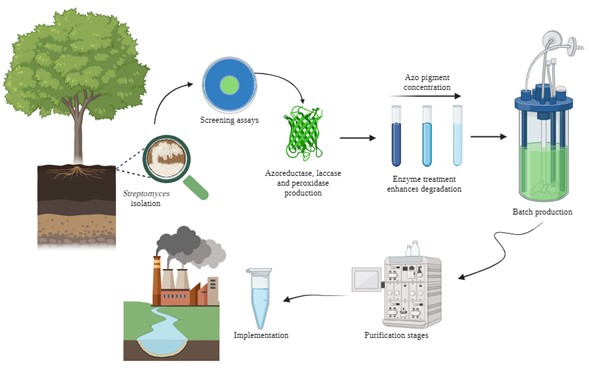

Graphical Abstract

Keywords

- bioremediation

- Streptomyces

- azo pigments

- isolation sources

- encapsulation

- biodegradation

Azo pigments are widely employed in the textile, cosmetic, food and

pharmaceutical sectors due to their vibrant colors and intense shades [1]. They

represent a massive portion of materials in these sectors, accounting for

65–75% of the pigments in the textile and leather markets [2]. Azo dyes are

classified as aromatic compounds with one or more azo groups (–N=N–) and are

synthesized via the diazotization of aromatic amines followed by coupling with a

coupling component, thus resulting in a wide range of colors ranging from yellow

to red to orange Education management information systems (EMIS) is a private

database of economic and market reports. URL: https://www.emis.com/la/. These

pigments are dyes with broader market impacts, increasing from

Contamination with azo pigments represents a substantial risk to human health and can disrupt biological systems, thereby affecting the diversity of the rhizosphere community and the natural activities of certain species [6]. Frequently, the degradation of most azo products can lead to allergic, mutagenic, and carcinogenic effects in humans. In some cases, it may even induce teratogenic effects [7]. Reactive yellow 14 (RY14) is an azo dye that is commonly used for dyeing and printing cotton fibers in the textile industry. Several studies have reported that RY14 can cause the formation of RNA and DNA adducts, which can serve as precursors to cancerous cells [8, 9]. As a result, some countries have implemented regulations regarding the use of azo pigments in textile and leather products that may have prolonged contact with the eyes or human skin; however, close to 397 aromatic amines continue to be used without regulations [10]. Therefore, some remediation strategies have been investigated for the removal of possible azo contaminants that are present in wastewater or other dangerous residues from the textile and leather industries to improve water quality and mitigate the effects of azo pigments on the environment [11].

Wastewater decolorization treatments involve a series of physical and chemical processes to remove organic dyes [12]. Physical treatments do not involve chemical modification of the substances that are present in the water; instead, they make use of common forces (such as electrical, gravitational and/or van der Waals forces) or physical barriers [13]. Adsorption and reverse osmosis are the most commonly used physical treatments, whereas chemical treatments mostly involve advanced oxidation reactions, including Fenton’s reagent, ozonation, photochemical oxidation, and electrochemical oxidation, as well as photolysis (UV/H2O2) and photocatalysis (UV/H2O2/TiO2) processes [14]. However, physical methods exhibit disadvantages in their repetitive use because of their ability to elicit decolorization; in the case of adsorption, materials that function as special filters and that do not represent an excessive expense to the industry are needed [15]. In the case of chemical methods, especially those that require oxidation, coagulation or flocculation, the use of iron and aluminum salts is necessary, which, when used in massive quantities, also exert a negative impact on both the environment and human health.

In recent years, bioremediation has emerged as a focal point in environmental sciences due to its significant efficacy in removing emerged contaminants (particularly azo dyes) from different contaminated scenarios [16]. The most popular microorganisms for azo biodegradation/biotransformation are fungi and bacteria, which use biological processes such as bioabsorption, biodegradation (both aerobic and anaerobic), and enzymatic methods [17]. These approaches offer advantages over physiochemical methods, which are represented by reduced costs, time, and residual release. Moreover, biological treatments possess the unique capability to neutralize toxicity, in contrast to alternative methodologies that merely mitigate toxicity [18].

Bioabsorption is a viable method for azo dye decolorization; however, it does not facilitate dye degradation, thus necessitating supplemental enzymatic degradation processes in certain instances. Notably, this method yields substantial residual biomass posttreatment [19]. Conversely, biodegradation represents a comprehensive method enabling both decolorization and reduction of azo dye molecules into simpler derivatives [20]. Although biodegradation can occur either aerobically or anaerobically, studies suggest that aerobic-anaerobic conditions optimize complete dye degradation [17]. Enzymatic processes complement these methods by facilitating the mineralization of reduced dye forms through the action of enzymes such as laccase, azo reductase, peroxidase, and hydrogenase, which are secreted by microorganisms. In bacteria-mediated bioremediation, actinomycetes exhibit the ability to degrade xenobiotic compounds due to their ability to produce ligninolytic enzymes, thus enabling the decolorization and mineralization of azo dyes. Species such as Bacillus subtilis, Pseudomonas sp., Escherichia coli, Acinetobacter sp., and Lactobacillus have been investigated for their efficacy in azo dye degradation [21]. Conversely, fungal-mediated bioremediation leverages ligninolytic fungi, such as Phanerochaete chrysosporium, Coriolus versicolar, Penicillium geastrivous, and Pycnoporus sanguineus, which have demonstrated the ability to degrade azo dyes [22]. Additionally, growth conditions pose challenges for fungal strains, as nitrogen deficiency adversely impacts lignin peroxidase production, thus consequently hindering decolorization [19].

In addition to bleaching, compared with fungi, Streptomyces actinobacteria exhibit the ability to mineralize contaminants, thus rendering them advantageous for expediting the decolorization of industrial dye mixtures and increasing the rate of decolorization and process efficacy [23, 24]. However, the potential of Streptomyces bacteria for azo dye degradation remains understudied. For this reason, this review aimed to explore the properties of Streptomyces strains and their potential to address environmental challenges, particularly regarding azo dye degradation.

To include most of the scientific articles on this topic, two different databases were consulted (SCOPUS and WOS [Web of Science]) using different search strategies, such as Boolean operators and synonyms. The utilized search equations were as follows: Scopus query equation TITLE-ABS-KEY “Streptomyces”AND (“azo”AND“dye”AND“degradation”) OR (“azo”AND“pigment”AND“degradation”) OR (“azo”AND“stain”AND“degradation”). WOS query equation “Streptomyces” AND (“azo”AND“dye”AND“degradation”) OR (“azo”AND“pigment”AND“degradation”) OR (“azo”AND“stain”AND“degradation”).

Different inclusion/exclusion criteria were selected for analysis of the studies, and duplicates were eliminated.

The inclusion criteria were as follows: (a) original research articles (not reviews, conference articles, or letters to the editor, among other articles); and (b) studies of azo dye biodegradation/bioremediation using only Streptomyces bacteria.

The exclusion criteria were as follows: (a) articles written in a language other than English; and (b) articles on methods of remediation, such as photocatalysts, fungi and Fenton reactions.

The selection process was performed in two steps. The first step was assisted by the use of Rayyan Qatar Computing Research Institute (QCRI) tool (http://rayyan.qcri.org) [25], wherein each researcher read the title and abstract of each paper after duplication deletions in a blinded process; afterwards, according to the inclusion or exclusion criteria, the researcher selected the articles that passed the second step. The second step involved full-text reading of the potentially eligible articles and selecting the final articles for data extraction.

Data collection was conducted by using a matrix with the key information of the topic to reduce the risk of avoiding some information and eliminating the bias of the researchers. The initial matrix was complemented with five random articles to verify that the information was sufficient and complete. The final matrix was used for data collection from the articles that were selected in the previous steps.

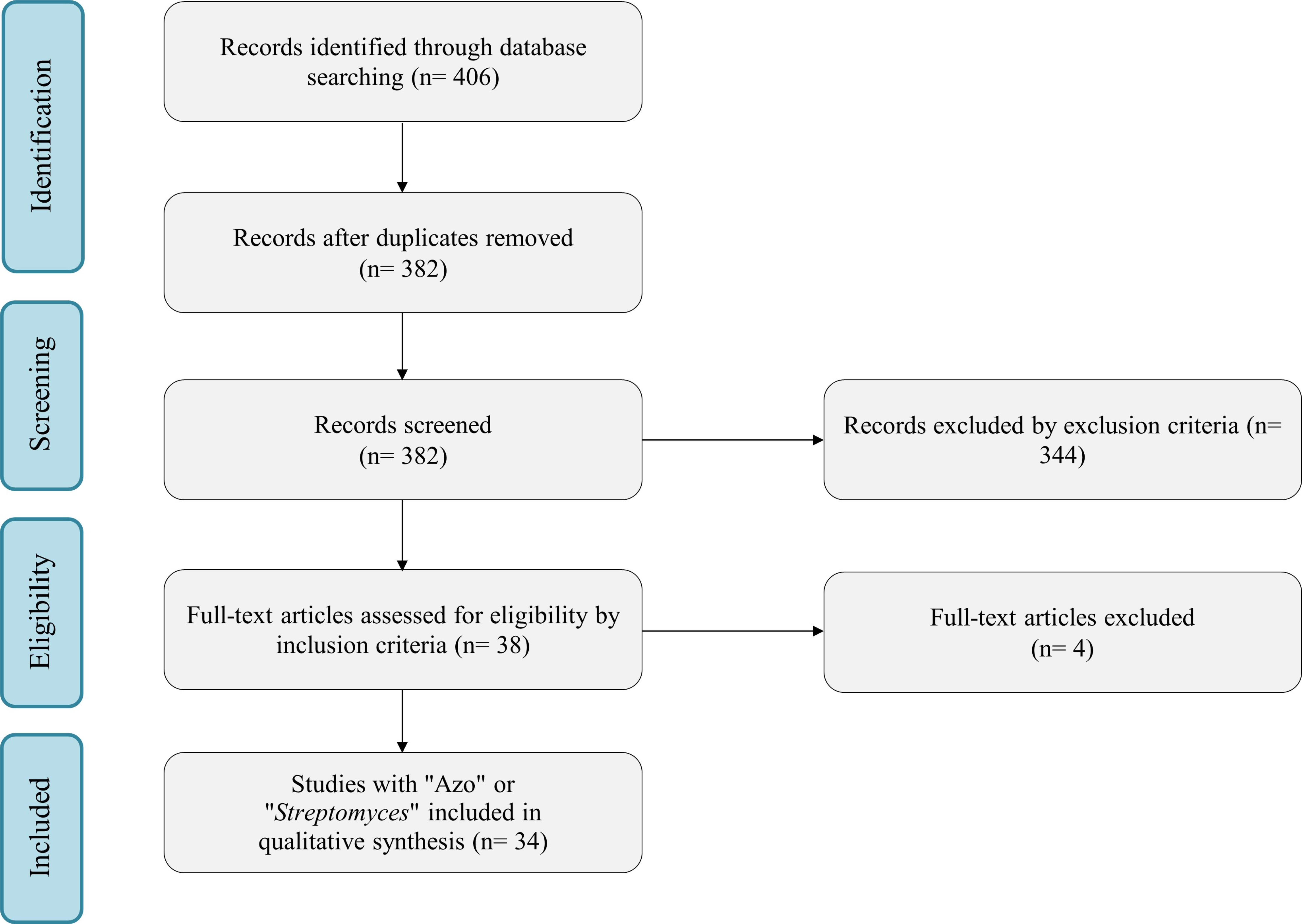

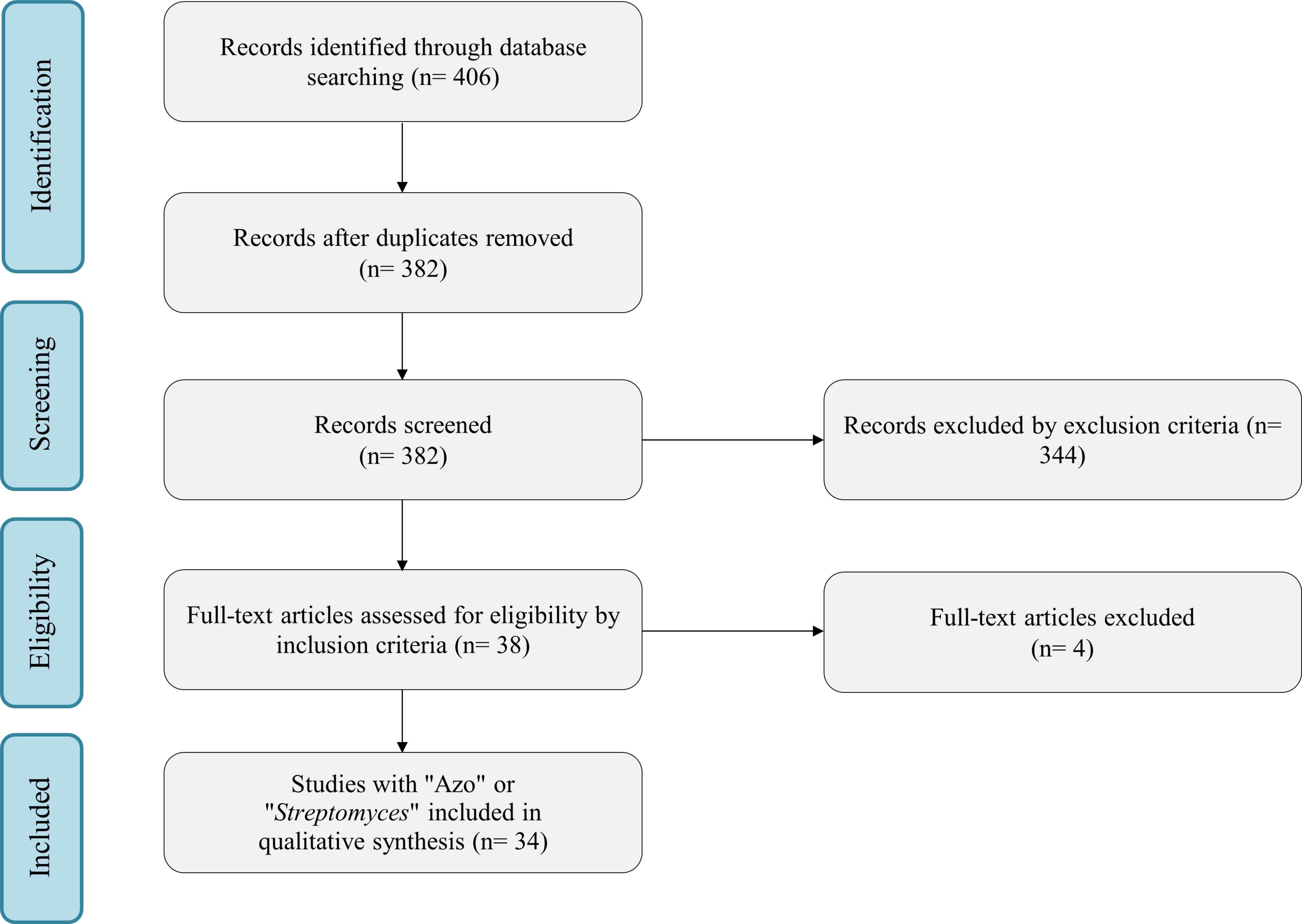

In the literature, 406 potential research articles were initially identified. Among these, 24 duplicates were identified, thus leaving 382 unique studies for further screening. The screening process involved reviewing the titles and abstracts based on predefined inclusion/exclusion criteria. Exclusion criteria included articles with the word “Review” and articles in languages other than English. For inclusion, studies were required to contain keywords such as “Azo dyes” or “Azo pigment” with “Streptomyces”. Following this initial screening, 38 articles were selected for a full-text assessment. Based on our inclusion/exclusion criteria, articles presented at conferences and congresses were also excluded. Three articles were excluded from the systematic review after full-text reading because they did not meet the inclusion criteria. These selected articles demonstrated the potential of Streptomyces for removing azo dyes from the environment through enzymatic activity or metabolic processes. The systematic review was conducted following the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta Analyses (PRISMA) statement guidelines, and the flowchart outlining the selection process can be found in Fig. 1.

Fig. 1.

Fig. 1.

Systematic Reviews and Meta Analyses (PRISMA) statement guidelines.

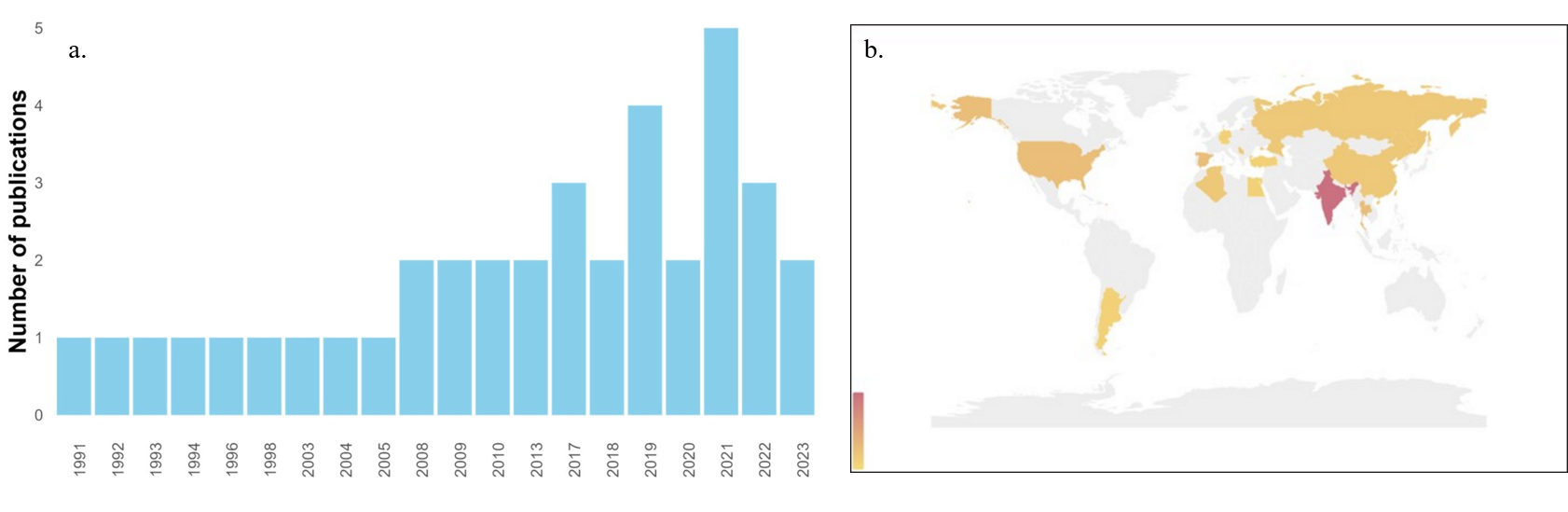

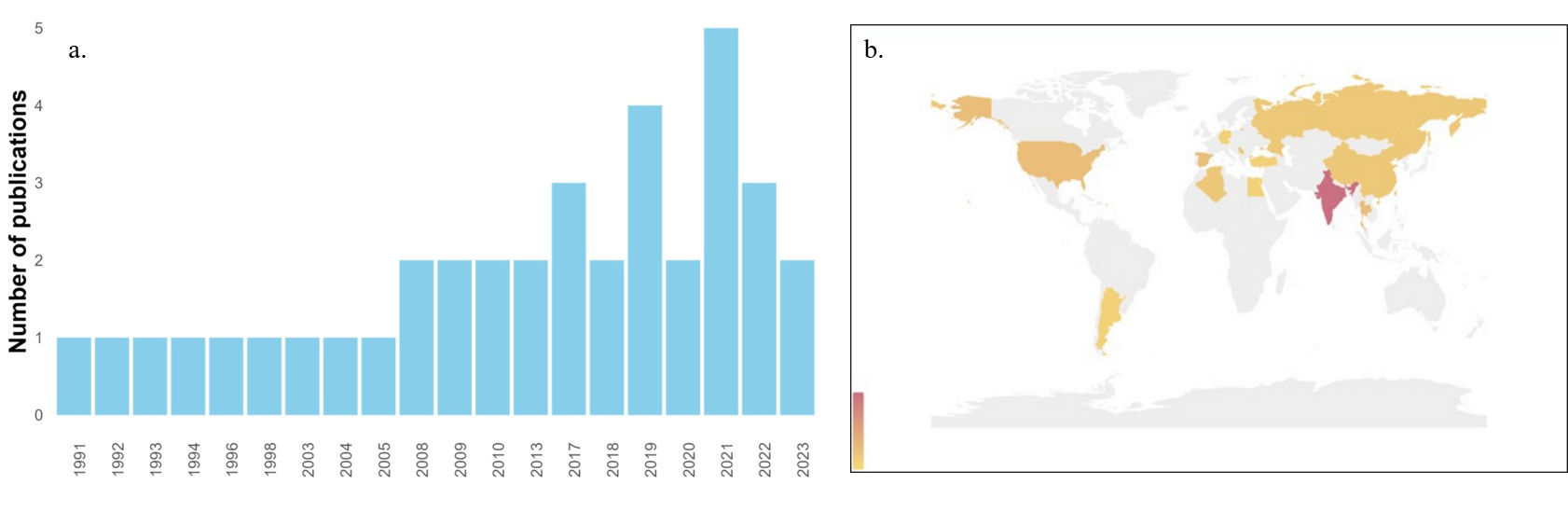

In general, the biological degradation of azo pigments using Streptomyces has been an understudied topic, with no more than five publications per year. In the past, particularly between 1991 and 2005, only an average of one article per year was published in this field (Fig. 2a). This scenario could be attributed to the limited environmental awareness during that time period, as research trends were primarily focused on areas such as medicine, industrial development, and social demography [26, 27]. Since 2008, there has been a noticeable increase in the number of publications in this area. This trend is a result of greater research funding support from developing countries and an increasing interest in environmentally friendly processes, including the leveraging of the diversity of natural microorganisms [28]. Notably, in 2021, there was a significant peak in research related to azo dye degradation by Streptomyces. This surge in interest can be linked to the global COVID-19 pandemic, which prompted major research journals to offer free access to medical research, subsequently encouraging increased publications in nonmedical research fields, such as a study by Gurnani and Kaur [29]. Currently, rapid population growth and urbanization have led to a surge in investigations related to azo dye bioremediation, which is driven by the necessity of reducing wastewater generation resulting from industrial expansion. Furthermore, the need to develop advanced remediation processes or technologies with minimal environmental and economic impact has fueled this research. Bioremediation using Streptomyces represents a promising avenue of research in this context [30].

Fig. 2.

Fig. 2.

Trends of publications in the literature by years and country of origin. (a) Publication distribution over the time. The y-axis shows the number of papers. (b) World map showing the countries where the articles included in this review were produced, specifically, the corresponding author affiliation.

According to Fig. 2b, India has emerged as the leading country for researching

azo dye bioremediation. In 2017, Asian countries accounted for approximately 75%

of the total production of synthetic dyes, with India and China being the top two

consumers [31]. These countries are strongly motivated to conduct research in

this field due to the critical environmental contamination stemming from the use

of azo pigments, the majority of which are present in textile industries.

Additionally, India is actively contributing to its target of achieving a

Synthetic dyes are extensively used in various industries, including textiles, pharmaceuticals, and the food sector, where azo pigments are present. Within this review, acid orange has emerged as being the most thoroughly investigated dye for biological degradation utilizing Streptomyces bacteria. This water-soluble anionic azo pigment serves as a common coloring agent in food products such as chili powder and tomato paste [33]. Consequently, environmental contamination with acid orange presents an elevated risk of toxic and mutagenic effects on aquatic ecosystems [33, 34]. Furthermore, certain studies have documented cases of individuals who develop rhinitis and genetic mutations after consuming water containing even trace amounts of acid orange [35].

Similarly, other azo pigments, such as indigo carmine, Evans blue, Congo red, Methyl orange, Bismarck brown, Xylidine ponceau, and Orange II, have also received significant attention in the literature (Table 1). These compounds have widespread applications in the textile and food industries, and their discharge into wastewater effluents has raised concerns due to their potential to increase carcinogenic and mutagenic effects on the environment and communities situated in proximity to these industrial sites [36]. These findings highlight the pressing need to mitigate the environmental impacts of azo dyes and leverage the microbiological degradation capabilities of Streptomyces bacteria.

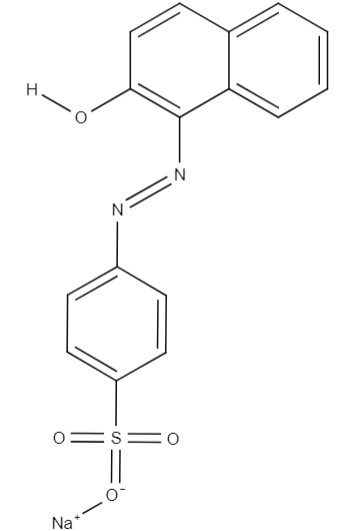

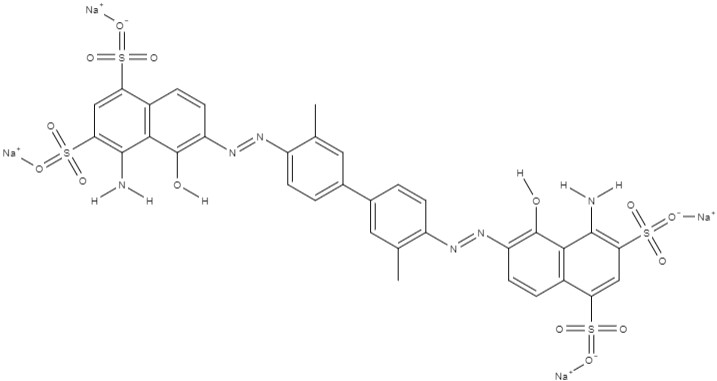

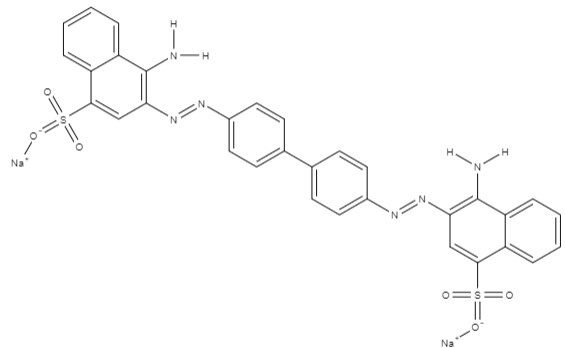

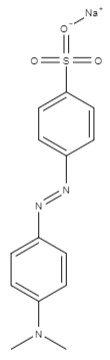

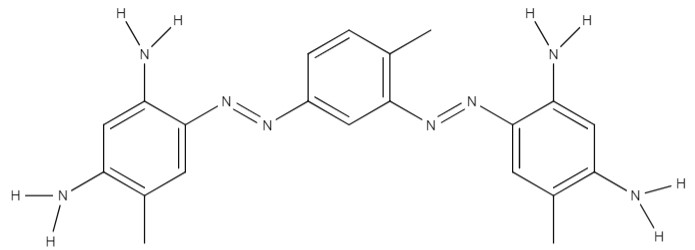

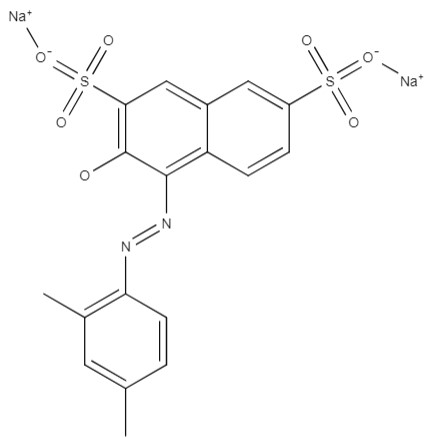

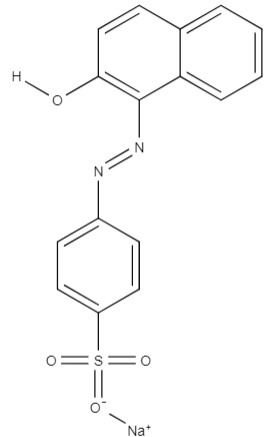

| Commercial name | International Union of Pure and Applied Chemistry (IUPAC) name | Molecular formula | Molecular structure | Main uses |

| Acid orange | sodium; 4-[(2-hydroxynaphthalen-1-yl)diazenyl]benzenesulfonate | C16H11N2NaO4S |  |

Textile and leathers |

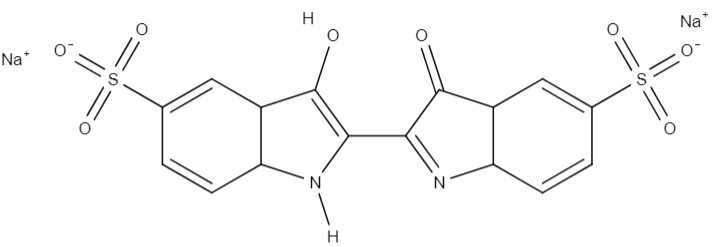

| Indigo carmine | disodium; 2-(3-hydroxy-5-sulfonato-1H-indol-2-yl)-3-oxoindole-5-sulfonate | C16H8N2Na2O8S2 |  |

Food industry |

| Evans blue | tetrasodium; 4-amino-6-[[4-[4-[(8-amino-1-hydroxy-5,7-disulfonatonaphthalen-2-yl)diazenyl]-3-methylphenyl]-2-methylphenyl]diazenyl]-5-hydroxynaphthalene-1,3-disulfonate | C34H24N6Na4O14S4 |  |

Medicine |

| Congo red | disodium; 4-amino-3-[[4-[4-[(1-amino-4-sulfonatonaphthalen-2-yl)diazenyl] phenyl] phenyl]diazenyl]naphthalene-1-sulfonate | C32H22N6Na2O6S2 |  |

Textile industry |

| Methyl orange | sodium; 4-[[4-(dimethylamino)phenyl]diazenyl]benzenesulfonate | C14H14N3NaO3S |  |

Textile industry |

| Bismarck brown | 4-[[3-[(2,4-diamino-5-methylphenyl)diazinyl]-4-methylphenyl]diazinyl]-6-methylbenzene-1,3-diamine; dihydrochloride | C21H28Cl2N8 |  |

Laboratory |

| Xylidine ponceau | disodium; 4-[(2,4-dimethylphenyl) diazinyl]-3-hydroxynaphthalene-2,7-disulfonate | C18H14N2Na2O7S2 |  |

Food industry |

| Orange II | sodium; 4-[(2-hydroxynaphthalen-1-yl)diazenyl]benzenesulfonate | C16H11N2NaO4S |  |

Textile, cosmetic and food industries |

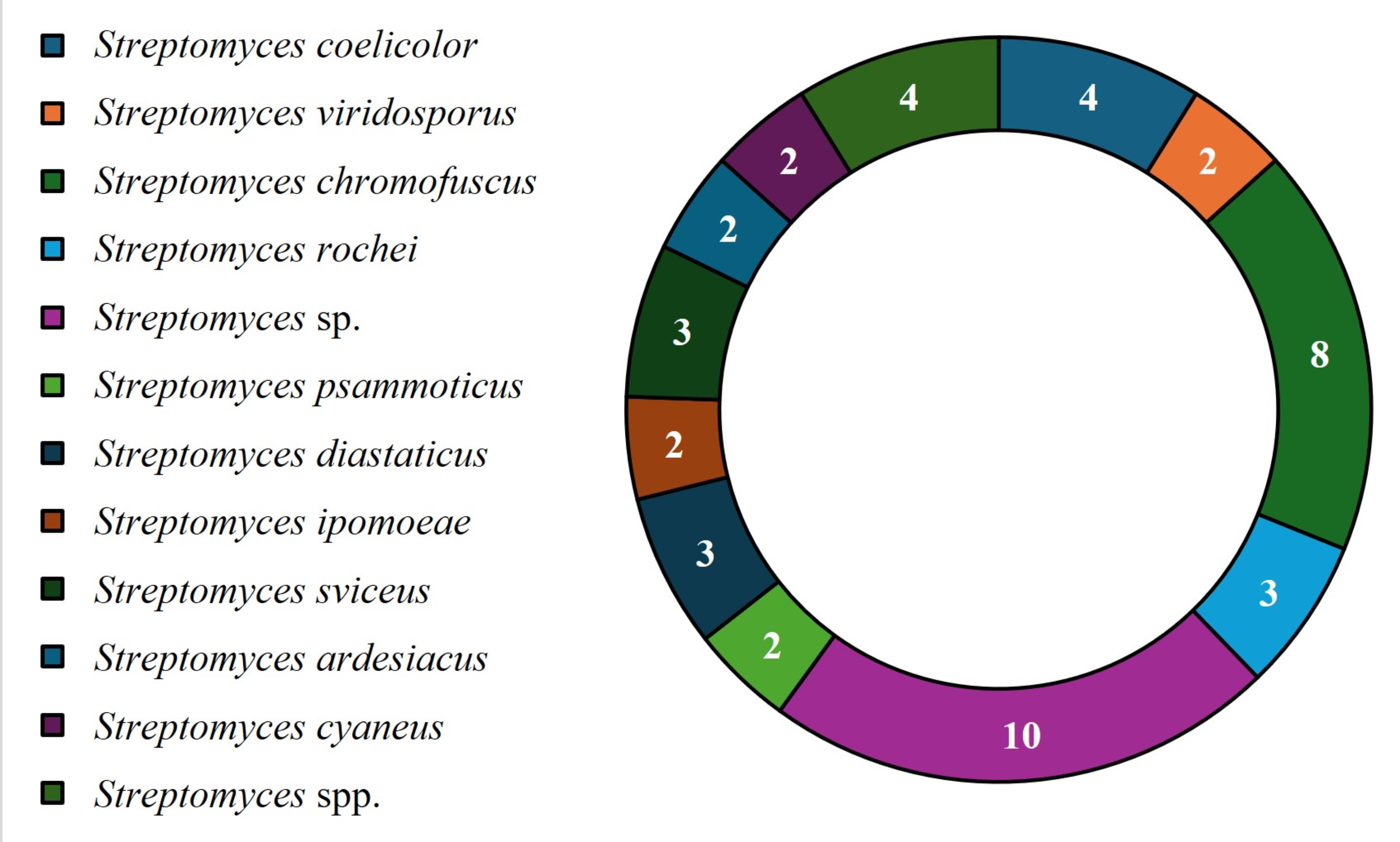

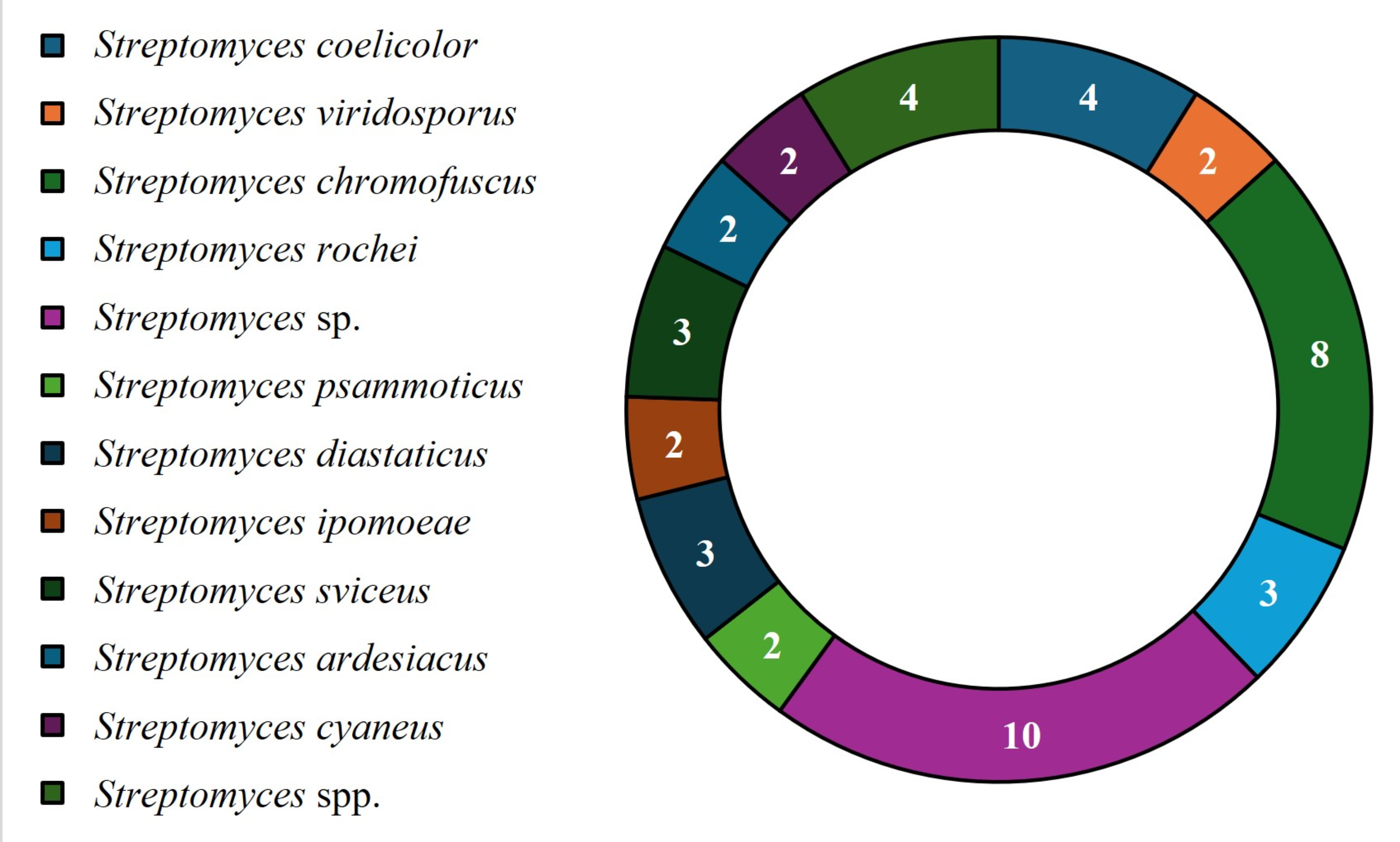

For the molecular identification of bioactive Streptomyces strains, the most popular methodology is 16S rRNA sequencing; however, most studies do not report of the species of strains that were evaluated. The most frequently reported species were Streptomyces sp., followed by Streptomyces chromofuscus, Streptomyces coelicolor, Streptomyces spp., Streptomyces virdosporus, Streptomyces rochei, Streptomyces psammoticus, Streptomyces diastaticus, Streptomyces ipomoeae, Streptomyces sviceus, Streptomyces ardesiacus and Streptomyces cyaneus (Fig. 3). These findings show that in most cases, 16S rRNA sequencing cannot be used to identify strains according to species name; thus, it is necessary to identify new primers or perform total sequencing to achieve complete strain identification.

Fig. 3.

Fig. 3.

Streptomyces strains with reported azo biodegradation activity.

Commonly, strains with enormous potential for the biodegradation of azo pigments are isolated from soil contaminated with different azo pigments or water effluents from textile industries. However, another unusual source was marine sediments or termites. These isolation sources represent a high opportunity for discovery of bioactive Streptomyces due to their harsh environment and extreme conditions, which forces microbial communities to adapt to these conditions, thus modifying their metabolism and producing different secondary metabolites, such as enzymes and bioactive compounds, with biotechnological applications in different industries [37].

The identification of enzymes produced by Streptomyces was performed by in vitro assays in liquid and solid media enriched with substrates, phenolic substrates (such as ABTS), guaiacol and dichlorophenol. The production of these enzymes is evidenced by the appearance of oxidative halos generating coloration in the culture medium. ABTS, or 2,2′-azinobis-(3-ethylbenzothiazoline-6-sulfonic acid), is the most commonly used substrate due to its exceptional stability and well-understood redox chemistry. When ABTS undergoes oxidation, it transforms into a free radical [38]. When laccase or peroxidase are used as the reducing agent, the radical that is formed is ABTS•+. In both cases, the oxidation process is visualized through the formation of a green complex in the culture, and enzymatic activity can be quantified by using a Ultraviolet–visible spectroscopy (UV‒VIS) spectrophotometer [39]. In addition, Chakravarthi et al. [39] reported of an enzymatic activity of 10.2 U/mg in Streptomyces sviceus supernatant when ABTS was used as the screening medium. Upon oxidation, guaiacol imparts a brown color to the culture due to the formation of tetraguaiacol. An enzymatic activity of 24.42 U/mg was documented in Streptomyces griseobrunnenus [40].

Indigenous bacteria isolated from contaminated environments have shown remarkable potential for bioremediation, as they can adapt to a wide range of conditions [41]. In some cases, this adaptation enhances metabolite and enzyme production and resistance to adverse conditions such as temperature and nutrient availability. Our systematic findings demonstrated that the predominant mechanism for azo dye degradation by Streptomyces bacteria is enzymatic, with laccase, peroxidase, and azoreductase being the principal enzymes produced by these bacteria [42]. Typically, Streptomyces enzymes are produced extracellularly, thus improving interactions between pigments and enzymes compared to intracellular production. However, this can complicate enzyme purification and the efficiency of azo dye degradation. Saipreethi and Manian [43] reported that an extracellular peroxidase in crude broth exhibited a specific activity of 0.017 U/mg protein, whereas the purified enzyme (obtained through a Sephadex G-100 column) increased the specific activity to 0.893 U/mg protein, thus enhancing the degradation process. Various researchers have proposed different degradation pathways. Several degradation pathways have been proposed for different azo pigments. Chakravarthi et al. [39] reported that the laccase enzyme produced by Streptomyces sviceus KN3 degrades the Congo red-21 azo pigment. Their findings suggest that laccase cleaves the molecule through asymmetric cleavage, followed by oxidative cleavage, desulfonation, deamination, and demethylation. The final degradation product was 1,2-benzenedicarboxylic acid (molecular weight = 390). They used gas chromatography–mass spectrometry (GC–MS) nalytical methods to track the intermediate molecules in the proposed pathway. Furthermore, Saipreethi and Manian [43] suggested that the degradation pathway of Eriochrome black T by the peroxidase enzyme produced by Streptomyces coelicolor SPR7 begins with azo bond cleavage and reduction, followed by symmetric cleavage through deamination. The final degradation products include phenol, benzene, sulfocarbolic acid, and nitrobenzene. These molecules help to reduce the negative impact of azo pigments on the germination process of Vigna radiata. Enzymes involved in reduction, such as peroxidase and azo reductase, require low concentrations of oxygen or anoxic conditions, as azo dyes and oxygen compete for reduced electron carriers. Hence, these systems operate best under motionless conditions [44].

Since the 1990s, laccase enhancers or mediators have been discovered, which are primarily aimed at enhancing the oxidation of specific components through nonenzymatic reactions. Mediators are characterized by their small molecular size and high affinity for the enzyme [45]. In this review, various enhancers have been reported to improve azo pigment degradation. For instance, Qin et al. [46] suggested that a series of lignin unit-derived compounds (particularly acetosyringone) can significantly enhance the degradation of reactive black 5 using laccase enzymes secreted by Streptomyces thermocarboxydus. These compounds also contribute to the degradation of mycotoxins such as aflatoxin and zearalenone. Similarly, Syringaldehyde (SA) and Methyl syringate (MeS), including Acid black 48, Acid orange 63, Xylidine ponceau, and Azure B, have been identified as being effective mediators for the degradation of azo pigments. The addition of these mediators resulted in a sixfold increase in decolorization compared to the use of laccase alone. This enhancement can be attributed to the stability of the phenolic compounds, which oxidize and serve as electron donor groups at the para-position [47, 48]. Moreover, natural phenolic mediators with commonly used compounds, including lignin, gallic acid, and tannic acid, have been reported to possess peroxidase activity. A recent study by Preethi [49] demonstrated that the addition of 1 mM gallic acid led to decolorization rates of 36.8% and 47.9% for direct red 23 and direct blue 15, respectively. This resulted in a twofold increase in degradation compared to peroxidase alone, as produced by Streptomyces coelicolor SPR7. This enhancement can be explained in a manner similar to that of laccase, as mediators generate substrate radicals that participate in various nonenzymatic reactions, including deprotonation, polymerization, and electron transfer (oxidative or reductive) [50].

In addition to substances that enhance degradation yields, there are compounds that can reduce the efficiency of enzymatic processes by either masking the substrate or blocking the active site of the enzyme (competitive inhibition). In some cases, inhibitors bind to allosteric sites, thereby diminishing enzyme activity [51]. The effects of inhibitors are often tested by using ABTS as a substrate. Lu et al. [40] reported that the laccase enzyme produced by Streptomyces sp. C1 could be completely inactivated by 2,2′,2′′,2′′′-(Ethane-1,2-diyldinitrilo)tetraacetic acid (EDTA), sodium azide (NaN3) and dicyclohexyl carbodiimide (DDC) at concentrations of 20 mM, 1 mM, and 1 mM, respectively. Certain compounds, such as EDTA and other organic substances, can reduce laccase activity by forming complex compounds with copper ions, which modify the enzyme’s active site [52, 53]. Additionally, ethanol at a concentration of 50% (w/v) led to an approximately 80% decrease in specific activity, which was attributed to denaturation caused by changes in pH. Similarly, Koschorreck et al. [54] reported that CuSO4 at a concentration of 2 mM inhibited the specific activity of laccase by 15% when secreted by Streptomyces sviceus SSL1. Furthermore, certain detergents, such as sodium lauryl sulfate (SDS) at a concentration of 1%, can denature an azoreductase enzyme produced by a Streptomyces strain [55]; moreover, SDS improves the solubilization of synthetic dyes by incorporating them into micelles. However, it is possible that azo dye molecules become trapped inside of these micelles, thus creating a barrier between the dye and the biodecolorizing bacteria and resulting in apparent inhibition [56]. In addition, potassium cyanide and sodium azide have been employed for denaturing studies of extracellular heme-containing enzymes. Tuncer et al. [57] reported that these chemical compounds could entirely degrade an extracellular peroxidase produced by Streptomyces sp. F6616, thus suggesting that the enzyme may contain a heme group in its tertiary structure. Sodium azide affects internal electron transfer, thus leading to a decrease in laccase activity [40].

The enzymatic activity of Streptomyces is influenced by various parameters, including the culture medium, growth temperature, shaking conditions, incubation time, and pH. These parameters can vary depending on the specific microorganism under investigation. Therefore, the application of statistical design methodologies such as Plackett‒Burman and Box‒Behnken methods is crucial for identifying the optimal conditions for enzyme production. Starch-casein media have been widely employed for laccase and peroxidase production by Streptomyces. Preethi [49] reported that starch-casein medium enhances peroxidase production compared to International Streptomyces Project 2 (ISP2) and Actinomycete Isolation Agar for Streptomyces coelicolor SPR7. They maintained a fixed temperature of 27 °C and an incubation time of 96 hours, with peroxidase production occurring primarily during the log phase of the microorganism (at approximately 56 hours). Various specific media have been reported to improve extracellular enzyme production, with temperatures and incubation times ranging from 25 °C to 40 °C and 3 to 7 days, respectively. The literature suggests that maintaining a carbon-to-nitrogen source ratio of 4.6:1, as recommended by Tuncer [57], can significantly enhance enzyme production. Moreover, Dong et al. [55] reported that a novel 702 bp gene from Streptomyces sp. S27 encodes an azoreductase gene known as “azored2”, which encodes an azoreductase enzyme. The azoreductase enzyme produced by the Streptomyces sp. S27 strain has a maximum relative activity at 55 °C, but its thermostability decreases at temperatures greater than 35 °C; for this reason, the incubation of Streptomyces strains should be in the range of 25–30 °C to guarantee the quality of the azoreductase enzyme.

Purification is a crucial step in enhancing the specific activity of azo-degrading enzymes. Various methodologies have been reported for this purpose, including chromatography, sodium dodecyl sulfate polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (SDS‒PAGE), ultrafiltration, and dialysis. Typically, enzymes are secreted into the culture medium, thus necessitating prior physical separations such as centrifugation, filtration (0.2 µm), ultrafiltration using 10 kDa molecular weight cutoff membranes [57], and precipitation using ammonium sulfate to improve the efficiency of subsequent chromatographic methods [40, 47]. In cases where the enzyme is produced by genetically modified microorganisms (and some genetic fragments are present in the sample), purification was performed by using a HisTrap HP column (GE Healthcare, Uppsala, Sweden) to separate the His-tag residue from the pET plasmid [47]. Sephadex G-100 columns are also employed for the purification of laccase enzymes; by using this method, the specific activity increased from 0.95 U/mg in the culture medium to 24.42 U/mg protein [40]. Immobilized metal affinity chromatography (IMAC), which requires a Ni-NTA column and potassium phosphate running buffer, has been used for laccase purification [58]. Additionally, fast protein liquid chromatography (FPLC) was used for laccase purification, thus obtaining a laccase with a monomeric structure and a molecular weight of approximately 60 kDa, which was detected by using SDS‒PAGE [39].

Dopamine pectin encapsulation is an innovative method employed to safeguard

enzymes from various adverse conditions, including temperature and pH variations.

The formation of the complex involves modifying pectin with dopamine through

chemical processes such as periodate oxidation and reductive amination reactions.

This approach represents a novel method of modifying pectin, as the conventional

method typically involves carbodiimide chemistry [58]. The optimal conditions for

the encapsulation process involve a 5 mol% dopamine concentration in the

peroxidation reaction and a 5% w/v dopamine-pectin complex. Under these

conditions, Popović et al. [58] achieved the highest specific

activity of 0.001 UI/mg for the encapsulated laccase enzyme. However, it is worth

noting that the encapsulation process has a negative impact on the Vmax parameter

of enzymatic kinetics, whereas Km increases. In the case of free laccase, the Km

and Vmax were 0.0634 mM and 7.22 µM/min

Calcium alginate is a frequently used method for the encapsulation of microorganisms or proteins due to its ease of development and the wealth of available information about the process [59]. Several articles have reported that the decolorization process is enhanced when enzymes are encapsulated. For example, Chakravarthi et al. [39] demonstrated that immobilized laccase exhibited a 92% decolorization rate of Congo red 21 azo dye after 24 hours, which is a 23% improvement compared to that of the crude enzyme. To encapsulate laccase enzymes using calcium alginate, a 4% sodium alginate solution was mixed with a 1 mg/mL enzyme solution at a ratio of 1:2 (v/v). This mixture was then placed into a 2% w/v CaCl2 solution. Afterward, the calcium alginate beads were washed with sterile water and stored at 4 °C. The encapsulation process is valuable for enhancing the capacity of laccase and peroxidase enzymes to degrade azo pigments in textile effluents and other biotechnological processes [39].

To determine the biodegradation percentage commonly used in decolorization

assays via UV‒Vis spectral analysis of the maximum wavelength of each pigment, it

is necessary to determine the

The release of aromatic amines occurs via cleavage of the N=N bond. According to Bhaskar et al. [62], several aromatic amines, such as benzidine, 4-aminobiphenyl and 2-napthylamine, are released by the chemical and enzymatic degradation of the dyes Xylidine ponceau-2R, direct black-38 and direct Brown-1 by Streptomyces SS07. This study demonstrated that the amines released by chemical and enzymatic processes are similar; however, chemical processes release a greater percentage of these compounds. Moreover, when the degradation occurs in an alkaline medium, the presence of hydroxyl ions in the aqueous phase enhances the cleavage compared to that of hydrogen ions [62].

According to Chakravarthi et al. [39], the metabolites produced by the degradation of Congo red-21 (Table 2, Ref. [39, 43, 61, 63]) are nontoxic to plants. Additionally, it was evident that the products of the degradation of this dye did not affect the structure of the plant chromosomes, and it presented with a greater germination potential and normal growth in the seeds of the plants that were exposed to these metabolic agents.

| Azo dye | Metabolite name | Monitoring technique | Reference |

| Direct brown-1 | • Benzidine | LC‒MS and UV‒VIS | [63] |

| • 4-amino biphenyl | |||

| Direct black-38 | • Benzidine | LC‒MS and UV‒VIS | [63] |

| • 4-amino biphenyl | |||

| Xylidine ponceau 2R | • 2,6-xylidine | GC‒MS and UV‒VIS | [61] |

| • 2,4-xylidine | |||

| • 2,4,5-trimethylaniline. | |||

| Congo red-21 | • 1,1′-biphenyl-4,4′-diol | GC‒MS and UV‒VIS | [39] |

| • [1,1′-bil(cyclohexylidene)]-2,2′,5,5′-tetraene-4,4′-dione 1,1′-biphenyl monosodium mono(1,1′-biphenyl)-4,4-bis(olate) | |||

| • sodium 4-aminonaphthalene-1-sulfonate | |||

| • 1,2-Benzenedicarboxylic acid | |||

| Eriochrome black T | • Phenol | FITR, GC‒MS and UV‒VIS | [43] |

| • Benzene | |||

| • Sulfocarbolic acid nitrobenzene |

LC‒MS, Liquid chromatography–mass spectrometry; UV‒VIS, Ultraviolet–visible spectroscopy; GC‒MS, Gas chromatography–mass spectrometry; FITR, Fourier-transform infrared spectroscopy.

In contrast, Saipreethi and Manian [43] reported that the metabolites

produced by the biodegradation of Eriochrome black T are nonphytotoxic (Table 2),

thus increasing the germination percentage of seeds to 50% compared to that of

seeds treated with de azo dye (20%). Furthermore, the statistical means of

radicle and plumule length were drastically affected after treatment with

Eriochrome black T (100 ppm). Conversely, the degraded compounds of Eriochrome

lacking T exhibited a lower toxicity profile on V. radiata, as the

radicle and plumule lengths were greater than those of the pure dye mixture (1.08

With the growth of the textile and food industries, substantial amounts of azo pigments will be demanded in the future, thus causing contamination at different sites, such as soil and water effluents. The Streptomyces genus has a greater biotechnological opportunity to reduce the impact of azo pigments and to allow for the utilization of different enzymes, such as laccase, peroxidase, and azoreductase, which are produced in the fermentation of these strains. These enzymes can degrade azo dyes, thus reducing their toxicity in the environment. However, research should focus on improving the technology and scale-up process to treat samples contaminated with azo and support other technologies to create a sustainable and circular process, thus minimizing the effects of subproducts in the environment. Additionally, other azo pigments should be studied, the number of evaluated molecules should be increased, and new subproducts of biodegradation should be identified, which will help the scientific community to formulate new warnings if a new hazardous molecule is found.

Furthermore, new broth media and culture methodologies should be explored. In this review, we found that the most popular culture method was substrate-submerged fermentation; however, solid-state fermentation has not been studied. These new study areas can increase the efficiency of bioactive enzymes, increase the profitability of the process, and increase the ease of performing new processes.

With this study, we demonstrate that Streptomyces bacteria have immense potential to reduce the impact of emerging contaminants from the textile, pharmaceutical, cosmetic, and food industries. Further studies of Streptomyces enzymes will be necessary to optimize bioprocesses and scale-up technologies, improve the efficiency of the bioremediation of azo pigments and help society in reducing the effects on human health, thus preventing future human diseases, mutations, and deaths.

This systematic review highlights the potential of bacteria of the genus Streptomyces to metabolize highly polluting azo dyes and the ways in which they can be treated and eliminated from the environment. Streptomyces produce different enzymes with great biotechnological application in scenarios contaminated with azo dyes. It is interesting to see how this area of research has grown in recent years.

Available in supplementary materials or by contact with the corresponding author.

Conceptualization, LD, and FB; methodology, FB, MF, JF and LD; software, FB; validation, FB; formal analysis, FB and JF; investigation, FB, JF, JG, MF and LD; resources, LD; data curation, FB and JF; writing—original draft preparation, FB, JF, MF and JG; writing—review and editing, FB, JF, MF and JG; visualization, FB; supervision, FB and LD; project administration, LD; funding acquisition, LD. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript. All authors have participated sufficiently in the work to take public responsibility for appropriate portions of the content and agreed to be accountable for all aspects of the work in ensuring that questions related to its accuracy or integrity. All authors contributed to editorial changes in the manuscript.

Not applicable.

We acknowledge at the General Research Directorate from the Universidad de La Sabana and Jeysson Sánchez at the Bioprospecting Research Group.

This research was funded by Universidad de La Sabana (ING-204-2018).

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Supplementary material associated with this article can be found, in the online version, at https://doi.org/10.31083/j.fbe1603029.

References

Publisher’s Note: IMR Press stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.