1 Serviço de Anatomia Patológica, Centro Hospitalar e Universitário de Coimbra, 3004-561 Coimbra, Portugal

2 Institute of Biomedical Sciences Abel Salazar, University of Porto (ICBAS-UP), 4050-313 Porto, Portugal

3 Centro de Investigação em Meio Ambiente, Genética e Oncobiologia—CIMAGO, Faculdade de Medicina, Universidade de Coimbra, 3004-535 Coimbra, Portugal

4 Centro de Anatomia Patológica Germano de Sousa, 3000-377 Coimbra, Portugal

5 Faculdade de Medicina, Universidade de Coimbra, 3004-535 Coimbra, Portugal

Abstract

Cluster of differentiation 44 (CD44) is a transmembrane protein expressed in normal cells but overexpressed in several types of cancer. CD44 plays a major role in tumor progression, both locally and systemically, by direct interaction with the extracellular matrix, inducing tissue remodeling, activation of different cellular pathways, such as Akt or mechanistic target of rapamycin (mTOR), and stimulation of angiogenesis. As a prognostic marker, CD44 has been identified as a major player in cancer stem cells (CSCs). CSCs with a CD44 phenotype are associated with chemoresistance, alone or in combination with other CSC markers, such as CD24 or aldehyde dehydrogenase 1 (ALDH1), and may be used for patient stratification. In the therapy setting, CD44 has been explored as a viable target, directly or indirectly. It has revealed promising potential, paving the way for its future use in the clinical setting. Immunohistochemistry effectively detects CD44 overexpression, enabling patients to be accurately selected for surgery and targeted anti-CD44 therapies. In this review, we highlight the properties of CD44, its expression in normal and tumoral tissues through immunohistochemistry and potential treatment options. We also discuss the clinical significance of this marker and its added value in therapeutic decision-making.

Keywords

- CD44

- solid cancer

- tumor progression

- therapy

- cancer stem cells

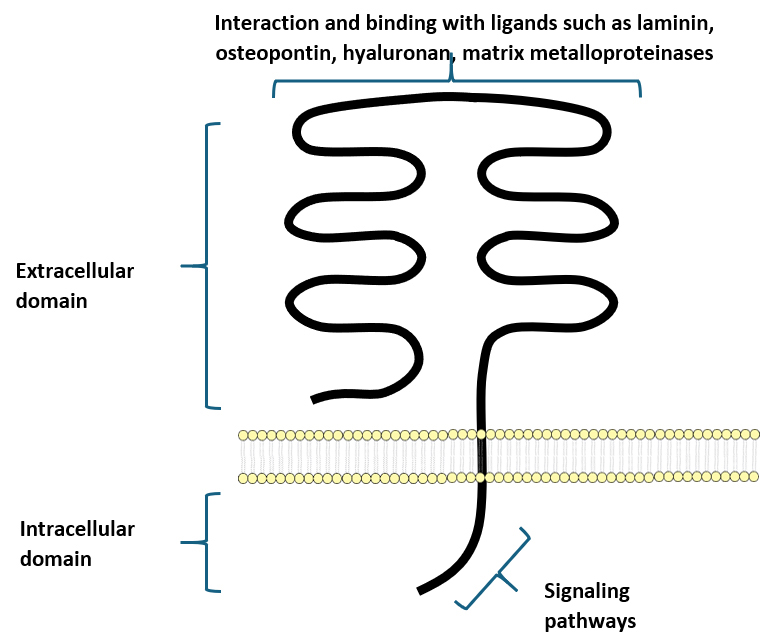

Cluster of Differentiation 44 (CD44) is a transmembrane glycoprotein encoded by a gene consisting of 20 exons on chromosome 11p13 [1]. The protein has a molecular weight of circa 200 kDa and results from the transcription of the exons 1–5 and 16–20 [2, 3]. This corresponds to the standard CD44, but some CD44 variants are generated by extensive alternative splicing involving the exons 6–15 [4]. CD44 is expressed throughout the human body, and its domains mediate its functions: the extracellular domain is responsible for the interaction with the external microenvironment; the transmembrane domain is a region for interaction with other proteins and has functions in lymphocyte homing; and the intracellular domain mediates transcription and cell signaling pathways [1, 5, 6, 7].

The concept of the CD isoforms is very important since the expression of different isoforms has been associated with disease development and tumor progression, such as the CD44v8-10 in the pancreas [8] and CD44v6 in prostate and colorectal cancers [9, 10, 11, 12, 13]. An example of the CD44 structure can be seen in Fig. 1. This review focuses on CD44 and its role in solid cancer as a prognostic marker and possible therapeutic target.

Fig. 1.

Fig. 1.

A simple representation of the Cluster of Differentiation 44 (CD44) protein structure. CD44 is a transmembrane molecule composed of an intracellular domain responsible for signaling and an extracellular domain that can bind various ligands.

CD44 is present throughout the human body, and its expression may be seen in normal adult and fetal tissues [14]. Historically, the CD44 standard isoform was isolated in hematopoietic cells [15], but nowadays, it is identified in different tissues.

CD44 isoforms are found in macrophages and select epithelial cells at various stages of development and play a vital role in regulating hyaluronic metabolism, lymphocyte activation, and cytokine release [15]. The expression of CD44 in keratinocytes has been implicated in skin inflammatory and fibrotic processes, wound healing, and scarring [16]. CD44 also has implications in angiogenesis. A study from 2017 in arteriovenous fistula [17] demonstrated that CD44 promotes the accumulation of M2 macrophages, extracellular matrix deposition, and wall thickening during fistula maturation, thus demonstrating the ability of CD44 to modulate the microenvironment.

CD44 has also been linked to glucose metabolism [18]; however, the data regarding this subject is not so clear.

The role of CD44 in hematopoiesis is rather well-characterized. Its expression is down-regulated in myeloid [19] and erythroid development [20], and it is retained in hematopoietic progenitors located in the spleen and bone marrow [21]; it is also associated with lymphocyte migration and activation [22]. Therefore, CD44 regulates hematopoietic stem cells and the bone marrow microenvironment due to its influence in matrix remodeling, cytokine release/capture, and binding of proteins to the cytoskeleton, among others, in a complex and intricate network [19].

Recently, CD44 has been studied in tumor cells and has caught attention due to its potential as a cancer stem cell (CSC) marker and its interactions with the extracellular matrix. Depending on the CD44 ligands, it can have a promoting effect on cell growth and migration [23].

A major ligand for CD44 is hyaluronan (probably the best characterized CD44 ligand), and through this binding, hyaluronan can activate cytoskeleton and matrix metalloproteinases (MMPs) signaling pathways responsible for tumor progression [24]. Interestingly, hyaluronan can be cleaved in several ways, resulting in low or high-molecular-weight forms; these forms exhibit different functions, with high-molecular-weight forms being associated with tumor growth and antiangiogenic responses, while low-weight forms are associated with increased cellular motility and angiogenesis, translating different signaling pathways [25].

CD44 is also involved in extracellular matrix remodeling through interaction with matrix metalloproteinase 9, inducing a connection of its proteolytically active form in the cell surface. It increases matrix remodeling, cellular migration, and distant dissemination [26, 27]. This matrix degradation with increased tumor motility and dissemination is also described in clear cell renal cell carcinoma both by mRNA and protein expressions [28].

CD44 is also a receptor for osteopontin, which is highly expressed in some

metastatic cancers [29]. The interaction between osteopontin and CD44 stimulates

cell migration, from the vessels toward inflammatory/pro-inflammatory sites [30].

By interacting with

Very interestingly, the interaction of MMPs with CD44 may be mediated by both normal fibroblasts and cancer-associated fibroblasts, as demonstrated by Fullár et al. [32]. In breast cancer, CD44 activation was described, in vitro and in vivo, as a negative regulator of CD146 in a mechanism dependent of MMP. Inhibition of CD44 by siRNA mechanisms was able to increase the expression of CD146, suppressing breast cancer progression by regulating cancer angiogenesis and cellular motility [33].

Pancreatic cancer is well-known for its tissue interactions and extracellular matrix (ECM) remodeling. A study in pancreatic cancer cell lines [34] treated with a conditioned medium derived from normal fibroblasts and cancer-associated fibroblasts showed higher expression of CD44 on the cancer cells treated with the medium from cancer-associated fibroblasts. These cells had higher stem cell features, higher tumorsphere formation, self-renewal, and resistance to drugs. The stem features were correlated with overexpression of osteopontin in the conditioned medium.

In cholangiocarcinoma, CD44 is also associated with disease progression. A study from 2021 demonstrated that CD44 silencing was associated with decreased Akt and mechanistic target of rapamycin (mTOR) activity and consequent limitation of cell proliferation [35]. The silencing of CD44 was also associated with lesser ECM remodeling and lower epithelial-mesenchymal transition (EMT) phenotype due to downregulation of vimentin and upregulation of E-cadherin. In intrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma, CD44 expression is negatively associated with the T cell proliferation score, hindering a sustained proliferation of T cells in the microenvironment, but this may be reverted by reducing CD44 expression [36].

In lung cancer, there is some evidence that the nicotine carcinogenic effects are associated with CD44 through a JWA/Specificity Protein 1 (SP1)/CD44 axis [37]. Nicotine has enhanced effects in colony and spheroid formation, and this may be inhibited by JWA upregulation; low levels of JWA are associated with high CD44 expression and tumor-aggressive behavior.

In melanoma, there is also data regarding CD44. Gene expression profiling identified a gene of biological significance – RNF128. This gene, when downregulated, correlated with the malignant phenotype of melanoma, promoting higher biological aggressiveness, mainly due to epithelial-mesenchymal transition (EMT) and the acquisition of stemness, with activation of the Wnt pathway via CD44, thus resulting in CD44 overexpression. Therefore, patients with melanoma with low RNF128 and high CD44 have a worse prognosis [38].

The CD44 effect in lung cancer is also affected by hormonal conditions in women. A study from 2022 [39] found that premenopausal women with late-stage lung cancer had a diminished expression of Sp1. Sp1 levels are negatively associated with metastasis and cancer stemness, and its levels are downregulated by estradiol, which promotes SP1 degradation. CD44 and SP1 have a strong inverse correlation, and since premenopausal women have higher estradiol levels, this interaction may be explored.

Head and neck squamous cell carcinoma is another cancer where CD44 has been the object of study. Using publicly available data from The Cancer Genome Atlas (TCGA) and resorting to gene expression, Ludwig et al. [40] demonstrated a positive correlation between CD44 levels and pro-angiogenic genes, and in some tissue samples, there was an association between CD44 and microvessel density. This is consistent with the rationale that CD44 cells secrete pro-angiogenic factors, stimulating tumoral angiogenesis. This angiogenic mechanism has also been studied in ovarian cancer and may be reversible by administration of metformin [41].

Data regarding sarcomas is scarce due to their heterogeneity and rarity. In osteosarcoma, an interesting paper developed by Ma and colleagues [42] described the role of CD44 in tumor formation and metastatic progression, especially in the absence of Merlin, a tumor suppressor protein encoded by the NF2 gene.

Many studies support the role of CSCs and their specific markers associated with malignancies. One such compelling marker in tumor malignancies is CD44. This marker has been studied in several studies, from in vitro to in vivo, the latter including animal models and human cohorts [43].

As a CSC marker, CD44 has been considered an interesting option [44]. Within the tumor, the CSCs have a strong capacity for self-renewal and differentiation, generating new cancer cells, and have been pointed out as a factor of therapy resistance [31, 32] and aggressive biological behavior, being defined as active architects of the tumor microenvironment [45, 46, 47, 48].

Several in vitro studies have demonstrated an association between CD44 expression and tumor aggressiveness. Hao et al. [48] have demonstrated an association between CD44 expression and tumor progression and metastases in prostate cancer. This is in line with the findings from Li et al. [49], who also described that CD44+ positive cancer is linked to aggressive behavior, and with the data from Lai et al. [50] that associates CD44+ cells with chemoresistance. In two very recent studies, Sihombing et al. [51, 52] demonstrated an association of ovarian cancer with CD44+ CSC with chemoresistance, which was in consonance with previous findings from the same group.

In breast cancer, CD44 is also described as a marker of worse prognosis [53], alone or in combination with other CSC markers such as CD24 and aldehyde dehydrogenase 1 (ALDH1) [54]. Some studies have addressed this issue in breast cancer cell lines [55, 56] and in animal models [55, 57], and were translated into clinical studies and may be useful to stratify patients in the triple-negative breast cancer subtype [58, 59]. Interestingly, the CD44 marker retains its prognostic impact even in brain metastases [60]. In triple-negative breast cancer, there is data stating that CD44 is the most differentially released protein in basal conditions and is associated with the modulation of the inflammatory tumor microenvironment [61].

There is a positive correlation of CD44 mRNA level with histological grade, hormone receptor status, and human epidermal growth factor receptor-2 (HER2) and epidermoid growth factor receptor (EGFR); increased mRNA CD44 is also related to keratin expression and exhibited adverse impact in the Overall Survival (OS) of patients with basal or HER2 subtype [62].

Functionally, inhibition of EGFR activity by erlotinib impaired the invasion and migration ability of breast cancer cell lines. Western blot assays demonstrated that erlotinib treatment decreased the expression of CD44, accompanied by reduced protein levels of mesenchymal and cancer stem cell markers. Collectively, this study suggested that the expression of CD44 was upregulated by the EGFR pathway, and CD44 had a robust impact on the development of breast cancer.

In biliary cancer, CD44 is also described as a marker of aggressive disease and unfavorable prognosis, both in the extrahepatic duct [63] and in the gallbladder [64], with tumors CD44+ having lower survival rates and therapeutic resistance. A study from 2018 [65] demonstrated that CD44 overexpression was associated with poor outcomes and was an independent prognostic factor for overall survival (OS). These findings were further studied in cellular lines, where CD44 silencing by RNA interference hampered the tumoral cell capacity for proliferation, migration, and invasion.

In gastric cancer, CD44 has been pointed out as a marker for stem cells. A robust study from Hou et al. [66] used data from the the cancer genome atlas (TCGA) and gene expression profiling interactive analysis 2 (GEPIA2) database and found significant differences in CD44 expression between neoplastic and non-neoplastic gastric cells, with a higher expression in the former, and was correlated with cancer stage and lymph node metastasis. Patients with lower CD44 expression had prolonged PS and PFS. Interestingly, this study also revealed an association with immune evasion. A study resorting to flow cytometry from Gómez-Gallegos et al. [67] showed a high expression of CD44 in cancer cells with higher tumor stages and associated with metastasis, prompting the methodology as a valuable method for CD44 identification as a prognostic biomarker, especially when combined with other cancer stem cell markers such as CD24, CD54, and EpCam. Transcriptional factors can also be pivotal in CD44 expression, and there is data that correlates Signal transduction and transcriptional activator 5A (STAT5A) with upregulation of CD44 expression and consequently tumor invasion and worse prognosis [68].

The CD44 expression in gastric cancer may be modulated by mRNAs. Li et al. [69] reported that overexpression of miR-711 suppressed cell proliferation, migration, and invasion through CD44.

Several studies in colorectal cancer are also in line with these findings.

Studies in cellular lines [70, 71] and animal models [72] demonstrate an

aggressive biological behavior of CD44+ colorectal cancer, which was also present

in clinical cohorts, including metastases [73, 74]. In colon cancer [75], CD44

expression has been associated with enhanced tumorigenesis and chemoresistance

via CD44/

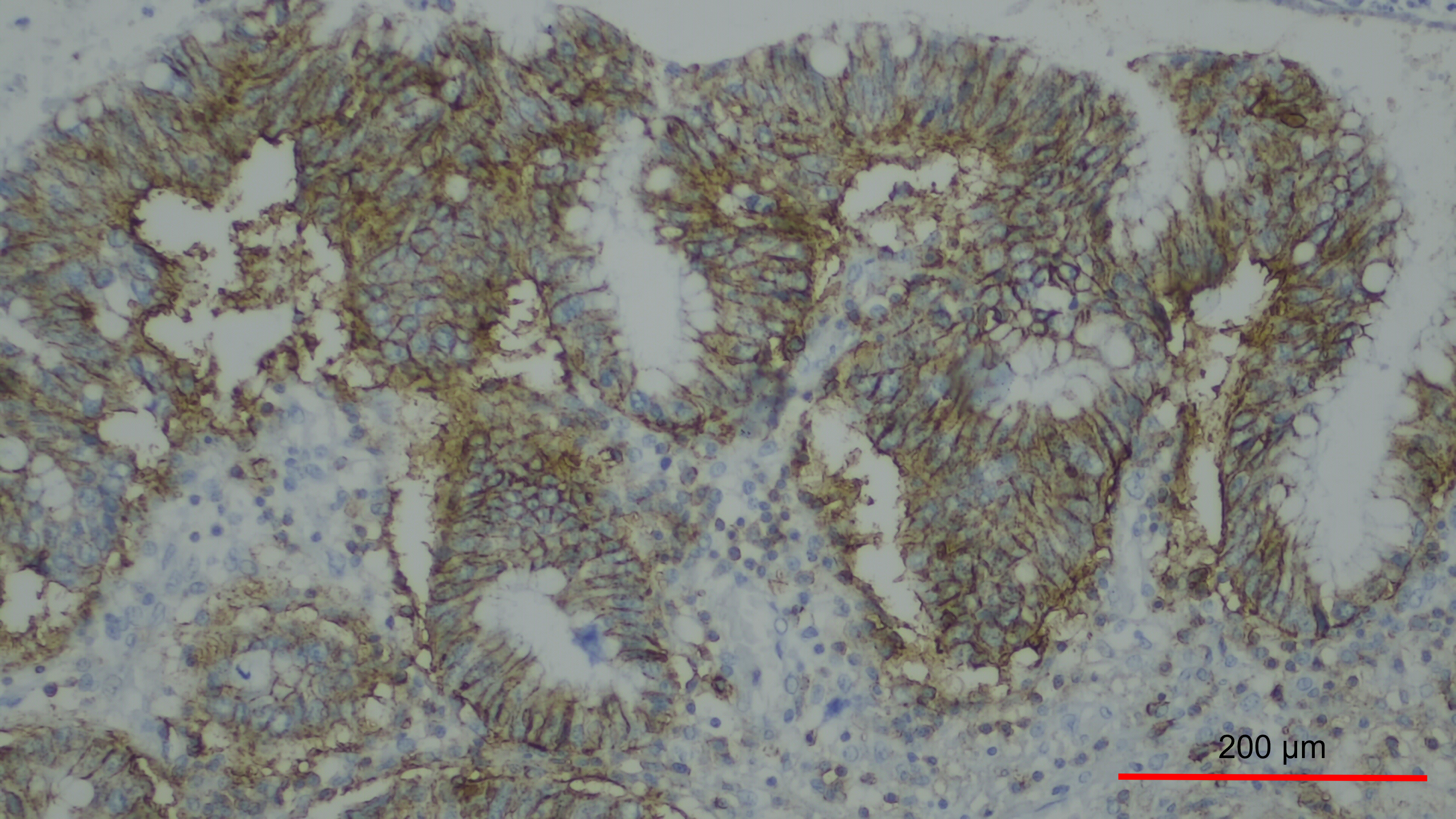

The main advantage of this marker is that it can easily be assessed by immunohistochemistry expression [76]. An example of this can be seen in Fig. 2 (Ref. [77]).

Fig. 2.

Fig. 2.

Overexpression of CD44 in a case of colorectal cancer. There is

membranous staining in more than 50% of tumor cells, 200

CD44 does not play an important prognostic role only in carcinomas. Several studies have assessed its role in brain cancer, specifically glioblastomas, with very similar biological effects, namely a switch to an M2 macrophage phenotype, immunosuppression, and Akt pathway activation [78, 79, 80].

In glioblastomas, the relation between CD44 and antiangiogenic therapy with Bevacizumab has been explored. In the study from Nishikawa et al. [81] a high expression of CD44 in the periphery of the glioblastomas was associated with higher resistance to antiangiogenic therapies.

To elucidate the roles of CD44 in the Bevacizumab therapy, in vitro and in vivo studies were performed using glioma stem-like cells (GSCs) and a GSC-transplanted mouse xenograft model, respectively. Glioblastomas expressing a high P/C ratio of CD44 were much more refractory to Bevacizumab than those expressing a low P/C ratio of CD44, and the survival time of the former was much shorter than that of the latter. In vitro inhibition of VEGF with siRNA or Bev-activated CD44 expression and increased invasion of GSCs. Bevacizumab showed no anti-tumor effects in mice transplanted with CD44-overexpressing GSCs. The P/C ratio of CD44 expression may become a useful biomarker predicting responsiveness to Bevacizumab in glioblastoma. CD44 reduces the anti-tumoral effect of Bevacizumab, resulting in more invasive tumors.

A recent study by Chen et al. [82] assessed the value of CD44 as a prognostic marker in a pan-cancer context. Using data from TCGA database, they were able to associate CD44 expression with Tumor Mutation Burden (TMB) and microsatellite instability (MSI), thus demonstrating that CD44 can be used to predict immunotherapy outcomes but was also associated with crucial immune cell-related pathways. The effects of CD44 in the tumoral microenvironment were explored, and CD44 expression was associated with a malignant phenotype and functional states at single-cell resolution, with a positive correlation with angiogenesis, differentiation, EMT, inflammation, and metastasis in several types of cancer. The CD44 expression was also significantly associated with tumor-infiltrating cells, such as T cells, B cells, NK cells, and macrophages, among others.

As stated in this review, CD44 has an important role as an oncology driver, marker of disease-aggressive behavior, and resistance to therapy [83]. With this in mind, it is rather logical that CD44 may be a promising therapeutic target, and several studies have addressed this aspect [83, 84].

In bladder cancer, an association with hormone therapy is described [85]. The study from Sottnik et al. [85] states that CD44 is significantly associated with androgen stimulation. An inverse correlation between tumor androgen receptors and CD44 mRNA and protein expression was identified in the studied samples from human patients with bladder cancer. This opens perspectives of modulating the hormonal axis, indirectly affecting the CD44.

Due to its special connection with metalloproteinase 9, a dual blockade has been attempted. Yosef et al. [24] developed a multi-specific inhibitor that simultaneously targets CD44 and both the catalytic and PEX domains of metalloproteinase 9, showing both anti-tumoral potency and specificity. The compound was able to compete with the metalloproteinase 9 localization on the surface of the cell, diminishing its catalytic activity and, therefore, the matrix degradation and the diverse signaling pathways.

However, in the clinical setting, developing anti-metalloproteinase drugs has been difficult due to dose-limiting toxicity and side effects [86]. The recent development of andecaliximab, a specific anti-metalloproteinase 9 antibody, has shown promising activity and safety in clinical trials [87, 88, 89, 90].

Even in rare cancer subtypes, CD44 has been identified as a promising

therapeutic tool. In nasopharyngeal carcinoma, the role of serglycin has gathered

significant attention [91]. Serglycin is a proteoglycan component of the ECM,

able to promote tumor seeding and metastases, thus being a marker of unfavorable

prognosis. Serglycin was also shown to be a new ligand for CD44, with a positive

correlation between the two markers, and the two were connected via positive

feedback loops. Serglycin was able to induce CD44 upregulation, with activation

of the MAPK/

CD44 may also have implications in immunotherapy [92]. A study from Liu et al. [84] found, in bladder cancer, that CD44 was involved in macrophage regulation and favored an M2 phenotype; it also stated that CD44 expression prompted a positive regulation of programmed death-ligand 1 (PD-L1) expression, thus leading to an immune exhaustion phenotype.

In lung cancer, a study in non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC) from Moutafi et al. [93] showed, using spatial proteomic profiling, that CD44 expression in the tumoral component (and not in the immune component) was a predictor of better progression-free survival (PFS) and OS, independent of PD-L1 tumor proportion score (TPS) expression; however high CD44 expression had no prognosis meaning in the absence of immunotherapy. The data was also able to demonstrate that there was upregulation of PD-L1 in tumor regions with high CD44 expression, prompting the use of CD44 as a biomarker for immune checkpoint blockade.

Clinical trials evaluating anti-CD44 therapies are also in the pipeline. In 2016, a phase I study [94] evaluated the efficacy of RG7356, a recombinant anti-CD44 immunoglobulin G1 humanized monoclonal antibody in a pan-cancer context in patients with advanced solid malignancies. There was an interesting safety profile, but the anti-tumoral activity was classified as modest.

In 2023, a new Phase I trial (NCT03616574) [95], assessed the efficacy of CA102N, a covalently bound conjugate of modified nimesulide and NaHA, the sodium salt of hyaluronic acid (HA), which is a CD44 natural ligand. This study enrolled 37 patients with locally advanced or metastatic solid tumors, and demonstrates a safe and well-tolerated profile, with preliminary evidence of anti-tumoral activity.

The therapy based on the capacity of the HA to deliver chemotherapy and decrease CD44 expression had been tried before in patients with small-cell lung cancer. HA conjugated with irinotecan in a cohort of 34 patients [96] achieved interesting but non-statistical significant results. Nevertheless, the study prompted that the use of immunohistochemistry may be used to identify patients who benefit from therapy based on HA conjugates.

In the age of nanotherapy, CD44 has also been contemplated. Nanotechnology-based nanocarriers have been developed to overcome the difficulties of conventional chemotherapy, namely side effects and an increase in anti-tumoral action [97, 98, 99, 100, 101, 102]. Since the molecular structure of a cancer cell is different from that of non-tumoral cells, receptors such as CD44 are valuable targets with the possibility of selective killing [103]. As we have seen previously, CD44 is overexpressed in different types of cancer, especially due to its high affinity with glycosaminoglycan polymers. Examples of these polymers include HA and chondroitin sulfate. HA has the capacity to bind to CD44, and since it has several functional groups, it can be conjugated with nanomaterials and chemotherapy agents such as paclitaxel and doxorubicin, among others [104, 105, 106, 107, 108, 109]. Similarly, chondroitin sulfate has the same therapeutic potential since it has a chemical structure comparable with HA; thus, it is able to be drug-conjugated [110, 111].

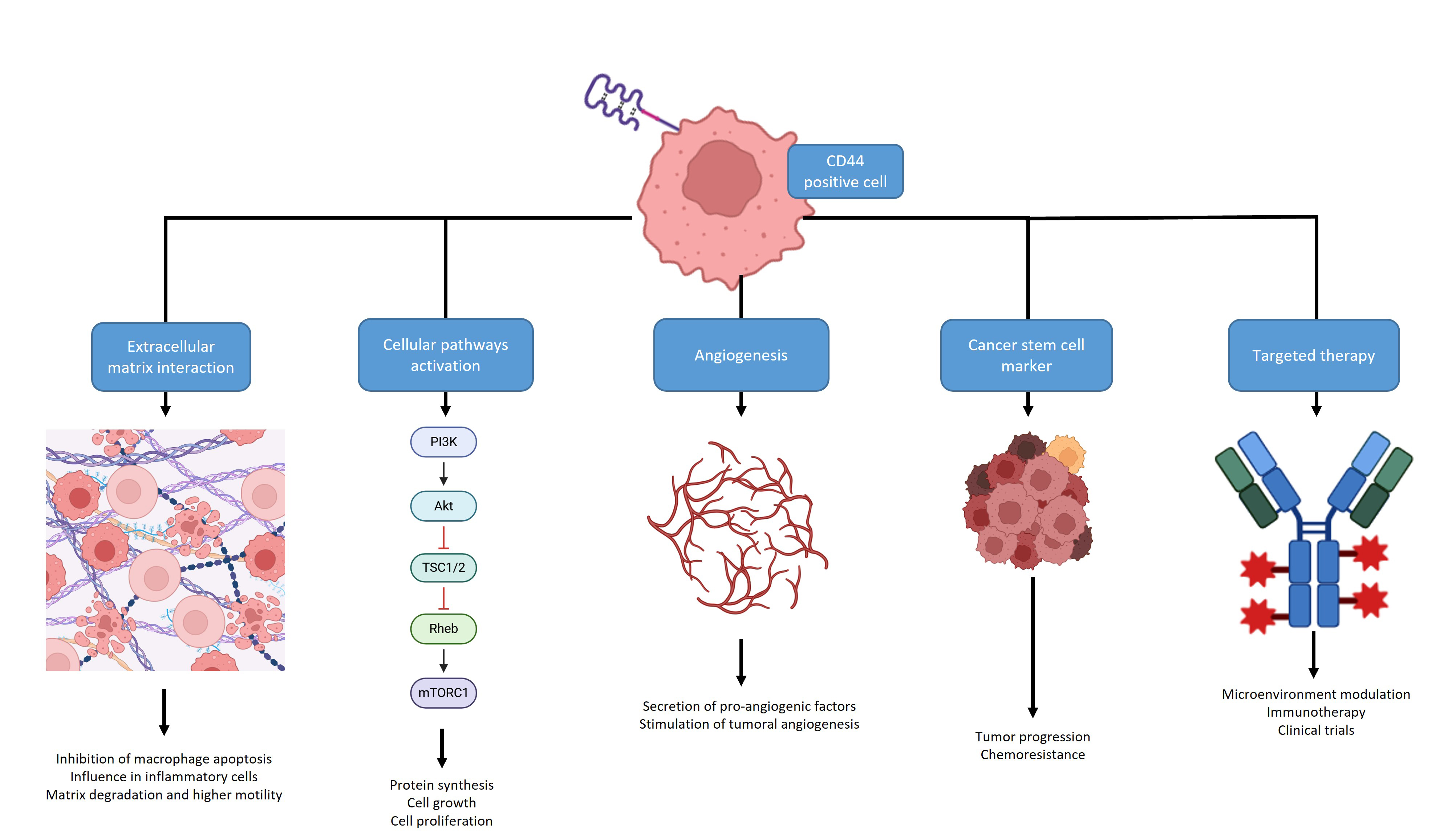

CD44 carries an adverse prognostic significance across various tumors, as summarized in Fig. 3.

Fig. 3.

Fig. 3.

A summary of the different roles of CD44: it can display interactions with the extracellular matrix, activation of cellular pathways, angiogenesis stimulation or play a role as a Cancer Stem Cell marker, all associated with tumor progression and outcome. It can also be a valuable target for therapy, alone or in combination and work as a surrogate marker for immunotherapy. Create with BioRender.com.

The straightforward assessment of this marker via immunohistochemistry should prompt a standardized evaluation in almost every pathology laboratory, tailoring patients for personalized medicine. CD44 exhibits a wide interaction with several signaling pathways, hormone receptors, and miRNAs; thus, it may be inhibited indirectly with less toxicity and good efficacy. CD44 has the potential to be performed as an ancillary marker in tumor biopsies/surgical specimens, prompting a standard identification of patients with aggressive tumors and less likely to respond to chemotherapy. This marker may be also beneficial for target therapy and referral to clinical trials. This is particularly valuable in the integration of targeted anti-CD44 therapies into clinical settings.

JMG and RCO performed the research, image draft and the writing/reviewing of the manuscript in similar manner. Both authors have participated sufficiently in the work to take public responsibility for appropriate portions of the content and agreed to be accountable for all aspects of the work in ensuring that questions related to its accuracy or integrity. Both authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Not applicable.

Not applicable.

This research received no external funding.

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

Publisher’s Note: IMR Press stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.