1 Formerly School of Health Sciences, Cardiff Metropolitan University, CF5 2YB Wales, UK

2 Pharmacy and Allied Health Sciences, Iqra University, 7580 Karachi, Pakistan

Abstract

A direct link between the tryptophan (Trp) metabolite kynurenine (Kyn) and the aryl hydrocarbon receptor (AhR) is not supported by metabolic considerations and by studies demonstrating the failure of Kyn concentrations of up to 100 μM to activate the receptor in cell culture systems using the proxy system of cytochrome P-450-dependent metabolism. The Kyn metabolite kynurenic acid (KA) activates the AhR and may mediate the Kyn link. Recent studies demonstrated down regulation and antagonism of activation of the AhR by Trp. We have addressed the link between Kyn and the AhR by looking at their direct molecular interaction in silico.

Molecular docking of Kyn, KA, Trp and a range of Trp metabolites to the crystal structure of the human AhR was performed under appropriate docking conditions.

Trp and 30 of its metabolites docked to the AhR to various degrees, whereas Kyn and 3-hydroxykynurenine did not. The strongest docking was observed with the Trp metabolite and photooxidation product 6-Formylindolo[3,2-b]carbazole (FICZ), cinnabarinic acid, 5-hydroxytryptophan, N-acetyl serotonin and indol-3-yllactic acid. Strong docking was also observed with other 5-hydroxyindoles.

We propose that the Kyn-AhR link is mediated by KA. The strong docking of Trp and its recently reported down regulation of the receptor suggest that Trp is an AhR antagonist and may thus play important roles in body homeostasis beyond known properties or simply being the precursor of biologically active metabolites. Differences in AhR activation reported in the literature are discussed.

Keywords

- biological factors

- cytochrome P-450-catalysed reactions

- gene deletion

- ligand binding

- molecular docking

- tryptophan metabolism

The present study illustrates the value of metabolism in revealing important

principles and resolving controversial issues in biomedical research, namely the

link between the tryptophan (Trp) metabolite kynurenine (Kyn) and the aryl

hydrocarbon receptor (AhR). The AhR is a major player in body homeostasis. In

addition to control of xenobiotic metabolism, it is involved in many cellular

processes, including cellular differentiation, stem cell maintenance and immune

function [1, 2, 3]. Its involvement in immune function has been the subject of

intense investigation ever since it was recognised that its activation by the

industrial pollutant dioxin (2,3,7,8-tetrachlorodibenzo-p-dioxin or

TCDD) induces immunosuppression in humans and animals [4]. Activation of the AhR

can be either beneficial or harmful, hence its description as “friend or foe?”

[4]. It is activated not only by industrial toxins such as TCDD, polycyclic

hydrocarbons and many other chemicals, but also by endogenous ligands. Some

endogenous ligands, such as indole, indirubin and the tryptophan (Trp)

photooxidation product and microbial metabolite 6-formylindolo[3,2-b]carbazole

(FICZ) are potent activators (see [5] and references cited therein). It is also

activated by various Trp metabolites (Fig. 1, Ref. [6]) and by those produced by

gut microbiota (Fig. 2, Ref. [6]) [7]. The physiological implications of AhR

activation by Trp metabolites are numerous and are determined by extent of

activation, type of immune cells targeted and biological transformations of

metabolites catalysed in part by the AhR-linked cytochrome P-450 system

[4]. Surprisingly, the parent compound Trp itself has not been investigated for

interaction with the AhR until only recently [8, 9] and by us in the present work

(see the Discussion below). Kyn interaction with the AhR received much attention

and is believed to underpin the Kyn effects on immune function, e.g., promotion

of T-regulatory (Treg) cell development, suppression of T helper type 17 (Th17) differentiation and

reduction of Interleukin 13 (IL-13) and IL-10 and Interferon gamma (IFN-

Fig. 1.

Fig. 1.

The tryptophan metabolic pathways. This Figure is based on Fig. 1 in [6] by Badawy AA-B. Tryptophan metabolism and disposition in cancer biology and immunotherapy. Biosci Rep 2022; 42:BSR20221682. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC9653095/. Abbreviations used: Acet, acetaldehyde; ACMS, 2-Amino-3-carboxymuconic acid-6-semialdehyde: also known as acroleyl aminofumarate; ACMSD, 2-Amino-3-carboxymuconic acid-6-semialdehyde decarboxylase; ALAAD, aromatic L-amino acid decarboxylase; AlcAm, alkyl amino; ALDH, aldehyde dehydrogenase; AMS, 2-Aminomuconic acid -6-semialdehyde; AA, anthranilic acid; FAMID, N-formylkynurenine formamidase; FICZ, 6-formylindolo[3,2-b]carbazole; 3-HAA, 3-hydroxyanthranilic acid; 5-HIAcet, 5-hydroxyindoleacetaldehyde; 5-HIAA, 5-hydroxyindoleacetic acid; 5-HIAcet, 5-hydroxyindoleacetaldehyde; 3-HK, 3-hydroxykynurenine; 5-HT, 5-hydroxytryptamine or serotonin; 5-HTP, 5-hydroxytryptophan; IDO, indoleamine 2,3-dioxygenase; IAcet, indole acetaldehyde; IAA, indol-3-ylacetic acid; ILA, indol-3-yllactic acid; ILD, indole lactate decarboxylase; IPAD, indolepyruvic acid decarboxylase; IPA, indol-3-ylpyruvic acid; KA, kynurenic acid; KYNU, kynureninase; KAT, kynurenine aminotransferase; NFKyn, N-formylkynurenine; MAO, monoamine oxidase; NAD+, oxidised nicotinamide-adenine dinucleotide; OHIndole, hydroxyindole; OHINDMETransfersase, hydroxyindole methyl transferase; PA, picolinic acid; QA, quinolinic acid; TDO, tryptophan 2,3-dioxygenase; Trp AT, tryptophan aminotransferase; TPH, tryptophan hydroxylase; XA, xanthurenic acid; kyn, kynurenine; KMO, Kynurenine-3-monooxygenase; 3HAAO, 3-hydroxyanthranilate 3,4 dioxygenase.

Fig. 2.

Fig. 2.

Tryptophan metabolism by gut microbiota. This Figure is based on Fig. 2 in [6] by Badawy AA-B. Tryptophan metabolism and disposition in cancer biology and immunotherapy. Biosci. Rep 2022; 42: BSR20221682. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC9653095/. Abbreviations: ALAAD, aromatic L-amino acid decarboxylase; ALDH, aldehyde dehydrogenase; CYP2E1, cytochrome P-450 2E1; IAAO, indoleacetic acid oxidase; IPD, indolepyruvate decarboxylase; MAO, monoamine oxidase; PL Dehydratase, phenyllactate dehydratase; PLDH, phenyllactate dehydrogenase; TrpAT, tryptophan aminotransferase.

The majority of previous studies however used the ability of potential AhR ligands to activate cytochrome P-450-dependent metabolism, particularly that catalysed by Cytochrome P450 1A1 (CYP1A1), which is upregulated following ligand binding to and activation of the receptor [9]. This proxy approach is not a sufficient proof of ligand affinity. The latter requires a more direct approach, that of binding assessment or ligand binding assay [5] and/or gene deletion experiments or molecular docking. An almost universally held view by immunologists and others is that Kyn is a direct AhR agonist and that its AhR activation is at the root of many immune diseases involving stimulation of the Kyn pathway (KP) of Trp degradation (Fig. 1) [17].

Most studies involving the Kyn-AhR link have assessed it by using relatively high concentrations of Kyn, e.g., 30–70 µM [18], 50 µM [19] or 100 µM [20] in cultured cell systems. Under these experimental conditions, Kyn could have undergone metabolic transformation to either kynurenic acid (KA) or anthranilic acid (AA) by the catalytic actions of Kyn aminotransferase (KAT) or kynureninase (KYNU) respectively (Fig. 1), and/or to trace derivatives with potent AhR binding properties [21]. Using the HepG2 40/6 reporter cell line and P-450-dependent drug-metabolising activity, DiNatale et al. [22] reported that 10 µM KA, but not Kyn, activates the AhR, with xanthurenic acid being much less active. A 10 µM [Kyn] is at least 4-fold higher than its normal plasma values [23]. Also, because plasma [Kyn] is much higher than [KA] (µM vs. nM), a moderate (47%) increase in [Kyn] induced by a small oral Trp dose (1.15 g: ~16 mg/kg) consumed by healthy volunteers results in a 209% increase in [KA] [23]. A recent study [9] showed that AhR expression was not enhanced in wild-type HEK293-E cells incubated for 72 h with 80 µM Kyn. These latter authors reported that Kyn enhances AhR expression in the absence of Trp, with Trp depletion being a key determinant, but, nevertheless, this enhancement could not be attributed to Kyn itself. Taken together, the above studies show that Kyn may not activate the AhR directly, but can do so via a metabolite(s). Based purely on metabolic grounds, KA is the most likely mediator, given the very low affinity of KAT for Kyn [24]. Assessment of AhR ligand affinity by receptor activation in cell cultures or in vivo using P-450-related metabolism is not a direct measure of binding or affinity. Molecular docking to the crystal structure of the AhR can provide a more objective indication of binding of potential ligands in the absence of metabolic and other biological modulators. Using this technique, we now report the failure of Kyn and 3-hydroxykynurenine (3-HK) to dock to the AhR and suggest that Kyn activates this receptor via KA, but possibly also other metabolites depending on the complement of Kyn pathway enzymes present in the experimental cell system or in vivo. Our strong docking of Trp and its reported [8, 9] down-regulation and inactivation of the AhR suggest that Trp is an AhR antagonist with potential implications for body homeostasis. We further suggest that differences in AhR activation by Trp metabolites reported in the literature are due to the prevailing metabolic and other biological conditions.

Molegro virtual Docker (MVD) software was utilised for the molecular docking of

Trp and its metabolites as described previously [25, 26]. Re-ranking was performed

to improve accuracy. When re-ranked, 10 independent docking runs resulted in 10

solutions. The structures of Trp and 30 of its metabolites were imported into the

MVD work space in Structure Data File (SDF) format. All H atoms were added and important valence

checked. The crystal structure of the human AhR was obtained from the protein

data bank (https://www.rcsb.org/) (PDB ID: 5Y7Y [27]) and imported into the MVD

work region at reasonable resolution levels (

Scheme 1 (Ref. [28]) provides a flow chart of the docking procedure. Some docking details have already been described [26]. Additionally, the following details may be relevant in the light of the results obtained. The MolDock score is a negative score where lower scores indicate better binding affinities. The score combines various interaction terms to give an overall indication of the binding strength between the ligand and the protein. Positive docking scores generally indicate poor binding or unfavourable interactions within the binding site. This can occur due to significant steric hindrances between the ligand and the protein, unfavourable electrostatics, with repulsive electrostatic interactions outweighing attractive forces, and poor conformational fit, wherein the ligand cannot adopt a favourable conformation within the binding site. The docking results of ligands giving positive docking scores, despite being biologically active compounds, suggest that their specific conformations or functional groups are not well-suited for binding to the active site of the target protein in the modelled conditions.

Scheme 1.

Scheme 1.

Flow chart and criteria of the docking procedure.

Only crystal structures with a resolution of 2.8 Å or better were selected for docking studies. High-resolution structures provide more accurate atomic positions and reliable geometry of the binding sites, which are critical for precise docking simulations. Preparation of the protein structure for docking was performed using the SWISS PDB VIEWER tool (https://spdbv.unil.ch/). Addition of hydrogen atoms to the protein, which are often missing in crystal structures, was performed using the software of the Protein Preparation SWISS PDB Viewer. This step is essential for accurately modeling hydrogen bonding interactions and ensuring proper protonation states. The protonation states of ionizable residues (e.g., Asp, Glu, His, Lys, and Arg) were assigned based on physiological pH (7.4). This ensures that the protein environment is correctly modelled for docking. Orientation of hydrogen atoms in hydroxyl, thiol, and amino groups was optimized to form the most favourable hydrogen bonds. This involves reorienting groups to maximize hydrogen bonding interactions within the protein and with potential ligands. Valences of all atoms, especially those in the binding site, were checked to ensure there are no unrealistic bond lengths or angles. This step helps in avoiding errors in the docking simulation due to incorrect valence states. If the binding site includes metal ions or cofactors, their correct coordination states and geometry were verified and, if necessary, adjusted. Finally, the prepared protein structures were subjected to a restrained energy minimization to relieve any steric clashes or unfavourable interactions introduced during the preparation steps. Tools such as AMBER (https://ambermd.org/), CHARMM (https://academiccharmm.org/), or GROMACS (https://www.gromacs.org/) were used for this purpose, applying a force field appropriate for the protein system. All other details are in the Mole Gro software website (http://molexus.io/molegro-virtual-docker/).

A summary of docking to the AhR of Trp, 30 of its metabolites and three established agonists of the receptor is illustrated in Fig. 3, with docking details given in Table 1 and amino acid residues at the AhR active site and those binding the ligands listed in Supplementary Table 1.

Fig. 3.

Fig. 3.

Molecular docking of tryptophan and 30 of its metabolites to the human aryl hydrocarbon receptor in comparison with known ligands. FICZ, 6-formylindolo[3,2-b]carbazole; TCDD, 2,3,7,8- tetrachlorodibenzo-p-dioxin; NFKyn, Nformylkynurenine; Kyn, kynurenine; 3HK, 3-hydroxykynurenine; KA, kynurenic acid; AA, anthranilic acid; XA, xanthurenic acid; 3-HAA, 3-hydroxyanthranilic acid; CBA, cinnabarinic acid; QA, quinolinic acid; PA, picolinic acid; 5HTP, 5-Hydroxytryptophan, ; 5-HIAA, 5-hydroxyindoleacetic acid; IEth, indole-3-ethanol, also known as tryptophol; ILA, indolelactic acid.

| Compound | Docking score | Re-ranked score | Log P | RMSD | Torsion number | HB | M.Wt. |

| FICZ and others | |||||||

| Own ligand | –48.91 | –44.47 | –1.8 | 0 | 2 | –10.279 | 92.09 |

| Indirubin | –144.08 | –97.16 | 2.7 | 0 | 1 | –3.794 | 262.26 |

| FICZ | –118.07 | –97.05 | 4.3 | 0 | 1 | –1.938 | 282.29 |

| TCDD | –119.79 | –93.66 | 6.3 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 321.97 |

| Kynurenine pathway | |||||||

| Trp | –107.21 | –83.16 | –1.1 | 0 | 3 | –6.780 | 204.23 |

| NFKyn | –100.97 | –25.09 | –2.3 | 0 | 5 | –4.066 | 237.23 |

| Kyn | 2002.36 | 65.71 | –2.2 | 0 | 4 | –6.574 | 208.20 |

| 3-HK | 2994.42 | 31.92 | –2.5 | 0 | 4 | –8.947 | 224.21 |

| KA | –98.9427 | –82.66 | 1.3 | 0 | 0 | –5.571 | 189.17 |

| AA | –79.9362 | –66.75 | 1.2 | 0 | 1 | –5.987 | 137.13 |

| XA | –97.26 | –77.59 | 0.9 | 0 | 0 | –5.925 | 205.17 |

| 3-HAA | –89.31 | –71.64 | 0.9 | 0 | 1 | –5.163 | 153.13 |

| CBA | –118.07 | –97.50 | 0.6 | 0 | 2 | –12.544 | 302.24 |

| QA | –94.87 | –78.20 | 0.2 | 0 | 2 | –8.546 | 167.12 |

| PA | –74.82 | –60.65 | 0.7 | 0 | 1 | –4.942 | 123.11 |

| Serotonin pathway | |||||||

| Trp | –107.21 | –83.16 | –1.1 | 0 | 3 | –6.780 | 204.23 |

| 5-HTP | –118.23 | –96.49 | –1.7 | 0 | 3 | –6.265 | 220.23 |

| 5-HT | –108.20 | –89.97 | –1.7 | 0 | 2 | –4.595 | 176.22 |

| 5-HIAA | –112.93 | –86.26 | 1.1 | 0 | 2 | –7.39 | 191.18 |

| N-Acetyl 5-HT | –129.26 | –95.23 | 0.5 | 0 | 3 | –4.70 | 218.25 |

| Melatonin | –110.81 | –76.61 | 0.8 | 0 | 4 | –0.809 | 232.28 |

| Decarboxylation and microbiota pathways | |||||||

| Tryptamine | –105.60 | –88.50 | 1.6 | 0 | 2 | 0.128 | 161.22 |

| Skatole | –87.04 | –70.51 | 2.6 | 0 | 0 | –2.367 | 131.17 |

| Indole | –76.33 | –63.95 | 2.1 | 0 | 0 | –0.593 | 117.15 |

| I-3-A | –76.33 | –63.95 | 2.1 | 0 | 0 | –0.593 | 145.16 |

| IAcetald | –102.91 | –84.17 | 1.4 | 0 | 2 | –2.244 | 159.18 |

| IAA | –99.78 | –78.88 | 1.4 | 0 | 2 | –2.500 | 175.19 |

| IAcetamide | –89.46 | –52.19 | 0.8 | 0 | 2 | –4.766 | 174.20 |

| ILA | –114.52 | –91.14 | 1.5 | 0 | 3 | –5.035 | 205.21 |

| IAcrylA | –103.36 | –83.63 | 2.2 | 0 | 1 | –2.787 | 187.19 |

| IEth | –99.58 | –76.57 | 1.8 | 0 | 2 | –2.447 | 229.20 |

| IPA | –110.06 | –88.81 | 1.3 | 0 | 2 | –2.154 | 203.19 |

| IPropA | –111.94 | –84.72 | 1.8 | 0 | 3 | –4.258 | 189.21 |

| Indoxyl | 1950.3 | –39.34 | 1.2 | 0 | 0 | –4.257 | 133.15 |

| Indoxyl SO4 | 2972.35 | –11.98 | 1.3 | 0 | 2 | –3.535 | 213.21 |

Docking scores are in Kcal/mol. Only the more accurate re-ranked scores are in bold. Abbreviations: TCDD, 2,3,7,8- tetrachlorodibenzo-p-dioxin; HB, hydrogen bond energy (kcal/mol); M.Wt., molecular mass; P, partition coefficient; RMSD, root mean square deviation; CBA, cinnabarinic acid; I-3-A, Indole-3-aldehyde; IAcrylA, indoleacrylic acid.

As shown in Table 1 and illustrated in Supplementary Fig. 1, the powerful AhR agonists indirubin and the Trp photooxidation product and metabolite FICZ showed equal binding potencies that were slightly greater than that by TCDD and are therefore included here as reference agonists and for comparison with Trp metabolites.

The data illustrated in Fig. 3, Table 1 and Supplementary Figs. 2,3

show that, of Trp and 10 metabolites of the KP, only Kyn and 3-HK failed to dock

to the human AhR crystal structure. By contrast, Trp and other kynurenines docked

strongly, with cinnabarinic acid (CBA) exhibiting the strongest binding, followed

by Trp = KA

The results in Fig. 3, Table 1 and Supplementary Fig. 4 show that all three 5-hydroxyindoles (5-HTP, 5-HT and 5-HIAA) docked strongly to the human AhR, with that of 5-HTP being close to that of the reference compounds. Docking of N-acetyl serotonin was comparable to that of 5-HTP and stronger than that of the melatonin metabolite.

Docking of metabolites of the decarboxylation (tryptamine) and transamination (indole pyruvic acid) pathways and of related metabolites produced by gut microbiota is also detailed in Table 1, summarised in Fig. 3 and illustrated in Supplementary Figs. 5,6. All 13 metabolites docked to the AhR to varying degrees. The strongest docking was observed with indolelactic acid (ILA), indolepyruvic acid (IPA) and tryptamine and the weakest was with indoxyl SO4. To test if this weak docking is limited to the human AhR, docking of indoxyl SO4 to the AhR of drosophila melanogaster and the mouse was performed. Indoxyl SO4 docked even more weakly to the mouse AhR and failed to dock to the fly AhR (Table 2, Supplementary Table 2, Supplementary Figs. 7,8).

| Re-ranked AhR docking scores (Kcal/mol) | |||

| Compound | Human | Drosophila | Mouse |

| Kyn | 65.71 | 72.03 | 32.72 |

| KA | –82.66 | –65.17 | –39.08 |

| TCDD | –93.66 | –52.97 | –70.05 |

| FICZ | –97.05 | 37.16 | –94.85 |

| Indoxyl SO4 | –11.98 | 14.87 | –7.58 |

Abbreviations: AhR, aryl hydrocarbon receptor; FICZ, 6-formylindolo[3,2-b]carbazole; KA, kynurenic acid; Kyn, kynurenine; TCDD, 2,3,7,8-tetrachlorodibenzo-p-dioxin.

To establish if the failure of Kyn to interact with the AhR is limited to the human receptor, docking of Kyn to AhR structures of 2 other species was also performed: those of Drosophila melanogaster (PDB 7vni) [29] and mouse (PDB 4m4x) [30]. As shown in Table 2, detailed in Supplementary Table 2 and illustrated in Supplementary Figs. 7,8, Kyn failed to dock to the AhR of these 2 species, as well as to that of human. By contrast, KA docked to all three structures as did TCDD. Only FICZ (and indoxyl SO4) failed to dock to the Drosophila AhR structure. Binding of KA, TCDD and FICZ appears to be strongest with the human AhR.

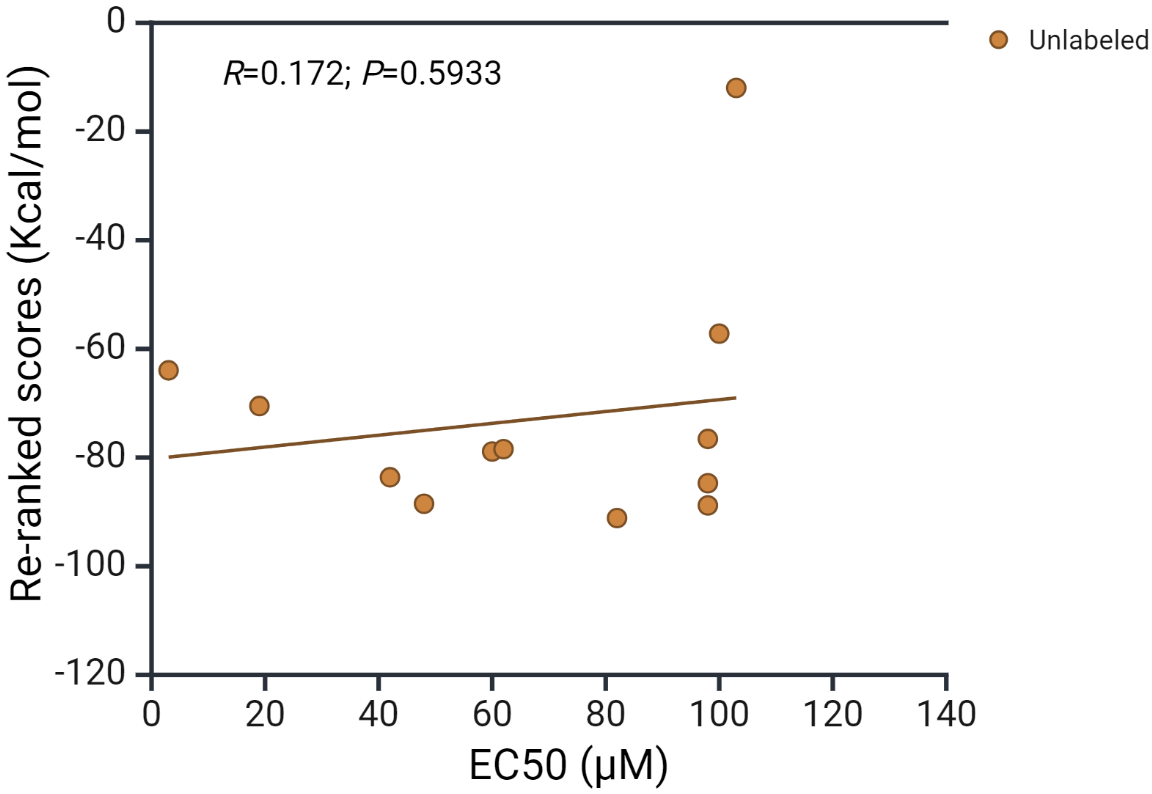

In order to correlate the AhR docking scores of Trp metabolites with published binding parameters obtained by other methods, we identified the median effective concentration (EC50) values of 12 metabolites from the review by Kumar et al. [31]. As shown in Fig. 4 (Ref. [31]), there appears to be no significant correlation between the docking score and the EC50 (Pearson Product Moment correlation gave a coefficient r of 0.172 and a p value of 0.5933).

Fig. 4.

Fig. 4.

Correlation of docking scores with AhR receptor activation by tryptophan metabolites. The EC50 values of the 12 compounds listed have been compiled from the review by Kumar et al. [31]. The 12 metabolites are: tryptamine, skatole, indoxyl SO4, indole acetamide, picolinic acid, indole ethanol, indole acrylic acid, indole propionic acid, indole lactic acid, indole-3-aldehyde, indole acetic acid and indole.

Our molecular docking results confirm the absence of a direct interaction between kynurenine and the human aryl hydrocarbon receptor (Fig. 3, Table 1 and Supplementary Table 1). Whereas species differences in AhR ligand binding are well documented [5, 32, 33], species differences do not provide an explanation of the absence of a Kyn interaction with the human AhR, as no docking was observed between Kyn and the AhR of two other species: the mouse and Drosophila melanogaster (Fig. 3, Table 2 and Supplementary Table 2). The failure of FICZ and indoxyl SO4 to dock to the fly AhR (Table 2) is however a further example of species differences.

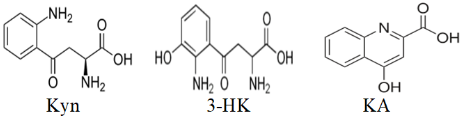

There are several factors involved in the failure of Kyn and 3-HK to bind (dock) to the AhR. These are molecular shape and size, hydrogen bonding and electrostatic interactions, steric hindrance, binding pocket conformation, energy landscape and binding affinity, and solvent effects. Thus, Kyn is a linear molecule with several functional groups, including an amino group and a carboxyl group (Fig. 5). The linear structure might not fit well into the binding pocket of the AhR if the pocket requires a more compact or differently shaped molecule. 3-HK has an additional hydroxyl group compared to Kyn, which can increase its polarity and potentially introduce steric hindrance if the hydroxyl group does not fit well within the binding pocket. The amino and carboxyl groups in Kyn can form hydrogen bonds, but if the binding site of the AhR does not have suitable hydrogen bond acceptors or donors positioned correctly, interactions may not occur. Whereas the hydroxyl group in 3-HK can participate in hydrogen bonding, it may also increase the overall polarity of the molecule, potentially leading to unfavourable electrostatic interactions if the binding site of AhR has regions of similar polarity or charge. Both Kyn and 3-HK might experience steric clashes with the amino acid residues lining the binding pocket of AhR. If the binding pocket is narrow or has a specific shape, larger or differently shaped molecules might not fit properly. The conformation of AhR’s binding pocket might not be compatible with the linear structure of Kyn or the additional hydroxyl group in 3-HK. Proteins often have binding pockets tailored to specific ligand shapes, and even small deviations can prevent proper binding. The binding energy landscape might not favour the interaction between AhR and Kyn or 3-HK. If the energy required for the molecules to adopt a binding-competent conformation is too high, or if the resulting binding energy is not sufficiently negative, stable docking will not occur. Finally, solvation can play a significant role in docking. If Kyn or 3-HK forms strong interactions with solvent molecules (e.g., water), this could compete with the binding interactions within the AhR binding pocket, leading to failed docking attempts. The structure of kynurenic acid (Fig. 5), by contrast, does not suffer from these restrictive influences, enabling it to bind to the AhR. Further structural studies are likely to clarify the roles of these potential determinants of the failure of Kyn and 3-HK to bind to the AhR.

Fig. 5.

Fig. 5.

Structures of kynurenine (Kyn), 3-hydroxykynurenine (3-HK) and kynurenic acid (KA).

The absence of a direct link between Kyn and the AhR is not surprising, as

studies have demonstrated the failure of Kyn to activate the AhR or induce its

mRNA expression at ligand concentrations of 10–100 µM [9, 22]. Indirect AhR

activation by Kyn can be visualised on biochemical grounds, with kynurenic acid

being the primary mediator. Thus, as KAT exhibits a low affinity for Kyn, the

impetus for KA formation is the substrate concentration [24]. Almost all studies of

Kyn-AhR interaction have been conducted with larger than physiologically relevant

concentrations of Kyn in cell cultures or in vivo, with no control over

potential metabolic transformation of Kyn. Our results are the first to

demonstrate the absence of a direct interaction of Kyn with the AhR. Previous

studies suggesting a direct Kyn-AhR link have used the proxy system of cytochrome

P-450-dependent drug metabolism or induction of AhR target genes. This

is no substitute for a pharmacological or a biochemical approach, such as

competitive ligand binding assays, gene deletion models [5, 34] or molecular

docking in silico. Future studies using these techniques should confirm

the absence or otherwise of a direct Kyn-AhR link, if experimental conditions are

well controlled to block Kyn metabolism. In the meantime, we propose that

diagrams of this link should read: Kyn

In the recent study by Solvay et al. [9], the authors reported that Trp depletion by culturing HEK-293-E cells (expressing KAT, but not Kynurenine-3-monooxygenase (KMO) or KYNU) in a Trp-free medium supplemented with foetal bovine serum (FBS: providing ~26 µM Trp) for 72 h, but not for 24 h, allows Kyn and various KP metabolites to enhance expression of AhR target genes. The 72 h culture ensures depletion of the Trp present in the FBS. Although Solvay et al. [9] proposed that Kyn may act via KA through KAT upregulation, an additional possibility is that the Trp provided by FBS can also be transaminated by KAT (or by Trp aminotransferase, if expressed) to IPA that is known to be a more powerful AhR agonist [35]. Solvay et al. [9] also reported that Trp down-regulates the AhR and proposed that its absence allows the above “weak” AhR agonists to exert a stronger activation. The Trp interaction with the AhR in the present study coupled with this AhR down regulation strongly suggest that Trp is an AhR antagonist and therefore functions in the opposite direction to neutralise AhR activation by agonists: a notion supported by the Trp dose-response data of the above authors [9] and also by the earlier reported [8] ability of Trp to block AhR activation by agonists. Given that the indole structure is amenable to AhR binding and that a whole range of indole metabolites of Trp are known AhR agonists, it is surprising that Trp itself has not been included in previous studies. The concept of Trp as an AhR antagonist may prove to have important biological and clinical consequences (see below) and should be the subject of future studies.

Our docking data in Fig. 3 and Table 1 show that most Trp metabolites exhibited

docking scores of –50 Kcal/mol or lower, with only one exception, that of

indoxyl SO4 giving a much less negative score. A similarly moderate docking

of indoxyl SO4 to the mouse AhR and no docking to the Fly AhR were observed

(Table 2). This moderate docking of indoxyl SO4 together with its relatively

high EC50 value (~100 µM) (Fig. 4) suggest that this

metabolite exerts effects largely and/or additionally unrelated to direct AhR

activation. Indoxyl SO4 is formed by sulphuration of indoxyl by aryl

(phenol) sulphotransferase (EC 2.8.2.1) in the reversible reaction: Indoxyl +

3′phosphoadenylylsulphate

The little known Trp metabolite, cinnabarinic acid (CBA) exhibited the strongest interaction with the AhR among Kyn and other metabolites (Table 1, Fig. 3). CBA is formed by auto-oxidation of 3-hydroxyanthranilic acid (3-HAA) with O2 first via the anthranilyl radical and O2-, followed by dismutation of superoxide to H2O2 and O2 and subsequent oxidation of the anthranilyl radical to CBA [40]. CBA exerts important effects, including generation of reactive oxygen species, apoptosis of thymocytes [41] and activation of NMDA (N-methyl-D-aspartate) receptors [42]. Its AhR activation is likely to play a part in the former effects. Utilisation of these properties of CBA may yield important indicators for therapeutic targeting.

Whereas kynurenine metabolites and indole derivatives produced by intestinal microbiota have been the focus of AhR research, little attention has been given to the potential links between 5-hydroxyindoles and the AhR. Our docking results show that 5-HTP, 5-HT and 5-HIAA are strong AhR ligands, despite earlier doubts regarding 5-HT [43]. 5-HTP [44], 5-HT [43] and 5-HIAA [45] have previously been suggested to activate the AhR, with 5-HT having been proposed to modify AhR activation by interfering with CYP1A1 clearance of AhR ligands [43]. The awaited demonstration of direct interaction of melatonin with the AhR [46] has recently been demonstrated [47] and is also reported in the present study. Our finding that the melatonin precursor N-acetyl serotonin docks to the AhR more strongly than melatonin is consistent with this precursor being a stronger antioxidant [48]. An intriguing observation is that of N-acetyl 5-HT being a positive allosteric regulator of Indoleamine 2,3 dioxygenase 1 (IDO1) resulting in restraining neuroinflammation [49]. Melatonin however is a competitive inhibitor of Trp 2,3-dioxygenase with an half maximal inhibitory concentration (IC50) of 2.7 µM [50]. These are clear examples of the cross talk between the serotonin and kynurenine pathways. Whether many of the beneficial effects of serotonin and melatonin [51, 52] involve their interaction with the AhR remains to be assessed. Table 3 (Ref. [1, 7, 8, 9, 12, 22, 43, 44, 46, 47, 53, 54, 55, 56, 57, 58, 59, 60, 61, 62, 63, 64, 65, 66, 67, 68, 69, 70, 71, 72, 73, 74, 75]) lists single examples of effects of Trp metabolites related to their interaction with the AhR. A detailed account of AhR-related effects is clearly outside the scope of the present discussion. However, effects of FICZ, KA and Trp merit further discussion.

| Metabolite | Reranked AhR docking score | Example of properties/effects associated with AhR binding [References] |

|---|---|---|

| Trp | –83.16 Antagonist | Production of AhR agonists [1], Blockade of AhR activation [8], |

| Down-regulation of the AhR [9] | ||

| NFKyn | –25.09 | Precursor of Kyn and subsequent metabolites |

| Kyn | 65.71 (–) | Indirectly activates the AhR via KA and AA |

| 3-HK | 31.92 (–) | Indirectly activates the AhR via XA and 3-HAA |

| KA | –82.66 | Physiological Kyn pathway AhR agonist [9, 22] |

| Pro- and anti-inflammatory [12, 53] | ||

| AA | –66.75 | Pro- or anti-inflammatory, acting via 3-HAA [53] |

| XA | –77.59 | Promotes tumor cell migration and parasite development [46] |

| 3-HAA | –71.64 | Enhances AhR activation by nuclear coactivator 7 [54], apoptotic [55, 56] |

| CBA | –97.50 | Protects against oxidative stress [57], enhances production of IL-22 [58] |

| QA | –78.20 | Skin anti-inflammatory: inhibits NLRP3 inflammasome activation [59] |

| PA | –60.65 | Anti-inflammatory [60, 61], but docking suggests AhR agonism |

| 5-HTP | –96.49 | AhR activator: mediates IL-2-induced T cell exhaustion in cancer [44] |

| 5-HT | –89.97 | Indirect AhR activator [43], but may also be an AhR antagonist |

| 5-HIAA | –86.26 | Reverses LPS production of proinflammatory Trp metabolites [62] |

| N-Acetyl 5-HT | –95.23 | Docking suggests AhR agonism, which may explain some of its protective properties |

| Melatonin | –76.61 | AhR agonism [47] may explain some of its protective properties |

| Tryptamine | –88.50 | Docking suggests AhR agonism, also a proligand acting via FICZ [63] |

| Skatole | –70.51 | Regulates intestinal epithelial function [64] |

| Indole | –63.95 | AhR agonist: potentiates IL-1b-mediated IL-6 mRNA induction [65] |

| I3A | –63.95 | Epithelial protection and antifungal resistance [7] |

| IAcetald | –84.17 | Agonist [66], hepatoprotective [67] |

| IAA | –78.88 | Maintains intestinal epithelial homeostasis via mucin sulfation [68] |

| IAcetamide | –52.19 | Alleviates alcoholic liver injury [69] |

| ILA | –91.14 | Anti-inflammatory [70] |

| IAcrylA | –83.63 | Anti-inflammatory [71] |

| IEth | –76.57 | Regulates gut integrity by correcting permeability [72] |

| IPA | –88.81 | Enhances barrier integrity [72] |

| IPropA | –84.72 | Improves gut-blood barrier function [73] |

| Indoxyl | –39.34 | Untested: likely to mediate the indoxyl SO4 effects |

| Indoxyl SO4 | –11.98 | Induces oxidative stress [74] |

| FICZ | –97.05 | Route-dependent metabolism determines type of effect [75] |

The Trp photooxidation product and bacterial metabolite FICZ is one of the most

powerful AhR ligands, as illustrated in the present study. It exerts a range of

biological effects that render it a potential drug in the making (reviewed in

[75]). It exerts antiinflammatory [76, 77, 78], antibacterial [79, 80] and anticancer

[81, 82, 83] effects in experimental models via a range of mechanisms including, among

others, decreased IL-17 and IL-22, increased chemokine ligand 5 and filaggrin,

increased macrophage survival and ROS production, decreased IL-6,

keratinocyte-derived chemokine and apoptosis, and increased NK cells, IL-18 and

IFN-

As our data and those of others [8, 9] suggest that Kyn activates the AhR indirectly via KA, the question arises as to whether some AhR-related, among the many, effects attributed to Kyn [84, 85] may in fact be exerted by KA. The answer awaits future studies. The association of KA with the AhR however is an important issue that cannot be over-emphasised. Whereas the “Janus-faced” KA is both pro- and anti-inflammatory [12, 53], it exerts a long-term influence on immune function through this association. With IDO1 induction by the AhR-IL-6-STAT3 autocrine loop [86, 87], activation of the kynurenine pathway can be maintained, with continued production of KA. This can lead to increased IL-6 production and with inflammation, increased IL-6 can induce IDO1 to produce more KA and activate the AhR [22]. A vicious circle is thus established and it is notable that KA levels are increased in tumors, sera, bone marrow and intestinal mucosal material of patients with a range of cancer types [88].

Tryptophan is an AhR antagonist [8, 9] and this study is a landmark statement in bioscience. It elevates Trp from being the simple precursor of biologically active metabolites to an orchestrator of defensive mechanisms against excessive AhR-related harm. Trp assumes the role of a protective parent of metabolites. While Trp supplementation increases the production of AhR activators in an in vitro simulator of intestinal microbial ecosystem, it was reported [8] to antagonise AhR signaling. Recently, Trp was reported to inhibit the gene expression and ligand activation of the AhR [9] and the authors suggested that Trp depletion enables weak ligands to exert a strong AhR activation. However, the Trp concentration-response data [9] suggest that Trp acts in the opposite direction, namely antagonising AhR activation by ligands. AhR antagonism by Trp now sheds more light on the earlier controversy of the role of Trp depletion versus kynurenine metabolite formation in bacterial and viral infections [89, 90]. While current opinion emphasises the importance of both phenomena, Trp depletion acquires a new meaning, synonymous with loss of protection against excessive AhR activation. Trp supplementation may be a valid option in appropriate circumstances. Although one of us [91] and others [92] have warned against the use of Trp in therapy of SARs-CoV-2 (COVID-19) infection to avoid production of the AhR-activating and T-cell damaging effects of Kyn metabolites, AhR antagonism by Trp suggests that Trp could be effective provided its use is combined with inhibitors of tryptophan-2,3-dioxygenase (TDO), indoleamine-2,3-dioxygenase (IDO) and aminotransferases. This should ensure blockade of production of the AhR agonists KA and IPA.

The present molecular docking findings strongly suggest that kynurenine

activates the aryl hydrocarbon receptor indirectly via kynurenic acid.

Investigators should therefore revise the Kyn-AhR link accordingly and insert KA

as an intermediate. As this is the first stage in elucidating the nature of the

Kyn-AhR link, a limitation of this study is the absence of further experimental

scrutiny of this link. The proposed Kyn

All data in this submission have been included. The source of the protein structures tested was the protein data bank (http://www.rcsb.org/).

SD and AABB designed the study. SD directed, performed and curated the experimental data. AABB analysed the data and wrote the first draft. AABB and SD edited and approved the final version. Both authors have participated sufficiently in the work to take public responsibility for appropriate portions of the content and agreed to be accountable for all aspects of the work in ensuring that questions related to its accuracy or integrity.

Not applicable.

Not applicable.

This research received no external funding.

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Supplementary material associated with this article can be found, in the online version, at https://doi.org/10.31083/j.fbl2909333.

References

Publisher’s Note: IMR Press stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.