1 Department of Urology, University of Iowa Hospitals & Clinics, Iowa City, IA 52242, USA

2 Department of Urology, Cochin Hospital, Assistance Publique-Hopitaux de Paris, 75014 Paris, France

3 Urology department, Universite Paris Cite, 75006 Paris, France

Abstract

While more than four decades have elapsed since intravesical Bacillus Calmette-Guérin (BCG) was first used to manage non-muscle invasive bladder cancer (NMIBC), its precise mechanism of anti-tumor action remains incompletely understood. Besides the classic theory that BCG induces local (within the bladder) innate and adaptive immunity through interaction with multiple immune cells, three new concepts have emerged in the past few years that help explain the variable response to BCG therapy between patients. First, BCG has been found to directly interact and become internalized within cancer cells, inducing them to act as antigen-presenting cells (APCs) for T-cells while releasing multiple cytokines. Second, BCG has a direct cytotoxic effect on cancer cells by inducing apoptosis through caspase-dependent pathways, causing cell cycle arrest, releasing proteases from mitochondria, and inducing reactive oxygen species-mediated cell injury. Third, BCG can increase the expression of programmed death ligand 1 (PD-L1) on both cancer and infiltrating inflammatory cells to impair the cell-mediated immune response. Current data has shown that high-grade recurrence after BCG therapy is related to CD8+ T-cell anergy or ‘exhaustion’. High-field cancerization and subsequently higher neoantigen presentation to T-cells are also associated with this anergy. This may explain why BCG therapy stops working after a certain time in many patients. This review summarizes the detailed immunologic reactions associated with BCG therapy and the role of immune cell subsets in this process. Moreover, this improved mechanistic understanding suggests new strategies for enhancing the anti-tumor efficacy of BCG for future clinical benefit.

Keywords

- bladder cancer

- BCG

- mechanism of action

- immunotherapy

- intravesical

Non-muscle-invasive bladder cancer (NMIBC) remains a major public health problem, as it represents currently the 9th most common cancer worldwide [1]. It is considered a heterogeneous tumor with potentially aggressive, life-threatening, behavior. Recurrence and progression of this tumor without treatment can occur in up to 80% and 50% of cases, respectively [2]. Treatment of NMIBC relies on a risk stratification approach according to tumor stage, grade, multifocality, recurrence history, and histologic features. For both intermediate-risk (IR) and high-risk (HR) disease, intravesical Bacillus Calmette-Guérin (BCG) has become the recognized standard-of-care adjuvant therapy to reduce NMIBC recurrence after initial transurethral bladder tumor resection (TURBT). BCG is also the mainstay therapy for eradication of an aggressive surface-spreading variety of NMIBC known as carcinoma-in-situ (CIS). BCG is most commonly instilled into the bladder first as “induction therapy” once weekly for 6 weeks followed by maintenance therapy for complete responders, given as 3-week miniseries every 3 to 6 months for 1–3 years [3].

BCG is a live, attenuated, vaccine form of cultured Mycobacterium bovis, a close relative of the human tuberculosis bacteria. In 1976, Morales et al. [4] first reported success using intravesical BCG to treat NMIBC. After demonstrating superiority over single agent intravesical chemotherapy in Phase III clinical trials, in 1990, it achieved FDA approval which propelled BCG to become the treatment of choice especially for HR NMIBC, including CIS. However, despite the success of BCG, about 40% of patients fail this treatment within two years. While up to half of initial BCG failures can be rescued with repeat BCG therapy, eventually many become BCG “unresponsive” where further BCG is poorly effectual [5]. Interestingly, patients who experience delayed high-grade (HG) relapse 24 months after therapy completion appear to response almost as well as those naïve to BCG, suggesting a time-dependent immune “reset”. Thus, BCG does not work with the same efficacy in all patients, and even it loses efficacy in some patients over time [6].

Another problem encountered when giving BCG therapy is the high prevalence of adverse events following BCG instillation. Local side effects such as chemical cystitis resulting in hematuria, urgency, and urinary frequency occur in up to 70% of cases. Most are mild-moderate and resolve within a few days. Systemic side effects such as malaise, rash, fever, and infectious sequelae may affect up to 40% of cases. Roughly 5% of patients have severe adverse reactions to BCG, including sepsis. Interestingly, most side effects appear host-dependent and do not associate with treatment success [7, 8]. Additionally, a patient’s tumor response to BCG therapy is a complicated process; BCG even works in transplant patients immunocompromised by anti-rejection drugs [9, 10]. Collectively these clinical observations suggest that the response to BCG therapy is not totally dependent on local immune reactions. Another observation is important to mention: patients receiving intravesical BCG experience a lower risk of respiratory infections and, thus, a protective systemic immune response against unrelated pathogens, including Covid-19 [11, 12].

The exact mechanism of action of BCG therapy in NMIBC is incompletely understood. Classic theories suggest that BCG induces innate and acquired immune responses and acts by inducing local inflammatory reactions within the bladder [13]. Recent data has suggested a direct effect of BCG on tumor cells by inducing an immune reaction after entering these cells and exerting a cytotoxic effect on them [14]. A better understanding of the mechanism of BCG therapy will help identify factors that may cause BCG failure. Additionally, this may aid in developing novel treatments for NMIBC by identifying how intravesical therapy eliminates cancer cells in the tumor microenvironment. In this article, we review the current literature available on the mechanism of action of BCG therapy given for bladder cancer and attempt to provide a more complete description of the intricate molecular processes involved in BCG effectiveness.

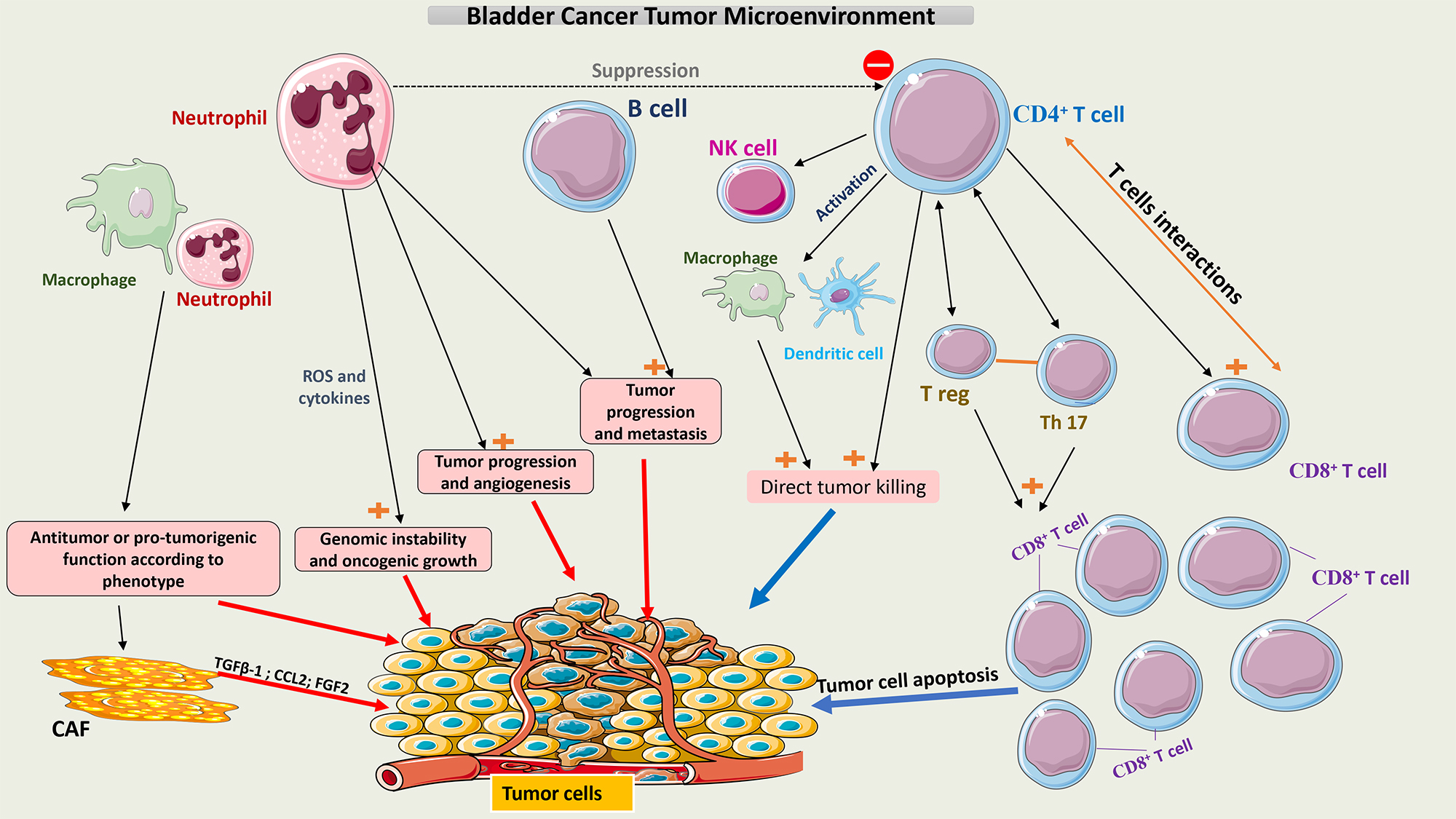

It is important to comprehend the role of multiple cells that infiltrate the

bladder tumor and constitute its microenvironment (TME). Numerous cells,

including lymphocytes, monocytes, neutrophils, natural killer cells (NK), and

dendritic cells (DCs), are involved in the release of various chemicals,

including reactive oxygen species (ROS) and cytokines [15]. It had been generally

accepted that lymphocytes elicit the anticancer response, whereas neutrophils

promote or sustain carcinogenesis, however, there are several interactions

between the innate and adaptive immune responses that are currently unclear and

challenge these “rules” [16]. Tumor-associated neutrophils (TAN) have been

reported to stimulate tumor development and angiogenesis, despite the possibility

that neutrophils play a binary function in the response to cancer [17].

Additional studies have shown that neutrophils may have a role in suppressing the

T-cell immune response to tumors, contributing to cancer progression [18].

Recently, high amounts of CD66b+ neutrophils have been identified in bladder

cancer specimens and have been associated with advanced tumor stage, grade, and

metastasis. Interestingly, CD4+ T and CD8+ T cells have also been

localized in high proportions within the TME [19]. CD4+ T cells may have

tumor-suppressing and promoting effects in the TME according to their phenotype,

type-1 (tumor suppressing) versus type-2 (tumor promoting). These subtypes are

largely characterized by their cytokine release pattern. Type-1 cells (often

referred to as T-helper type 1 (or Th1)) are associated with interleukins (IL)

such as IL-2, IL-12, IL-15, and interferon-gamma (IFN-

While the role of B cells in TME is not understood, a few reports suggest an unfavorable effect by promoting tumor invasion and metastasis [24]. By contrast, a high number of CD8+ T cells in tumors has been associated with a better prognosis for bladder cancer. As these cytotoxic cells are at the end of the immune response to fight cancer cells, their activation relies on a long chain of immune cells involving hundreds of signaling pathways, some of which have suppressive and complicated negative feedback loops. We already know that simply targeting CD8+ T cells with “adoptive” or stimulatory immunotherapy only leads to low anti-tumor efficacy. Most likely, this ‘low activity’ of some targeting therapy is because multiple effectors are needed proximally to achieve an effective anti-tumor immune response [20].

An additional component of the bladder TME arises out of the tumor stroma, which

contains cancer-associated fibroblasts (CAFs), epithelial cells, and

extracellular cellular matrix (ECM). CAFs are heterogeneous cells that surround

tumor cells and contribute to tumorigenesis by secreting different signal

molecules. Transforming growth factor beta 1 (TGF-

An adenosine-producing cell surface enzyme called CD73 is also important in the TME. CD73 expression can be found on fibroblasts, urothelial cells, lymphocytes, and endothelial cells. CD73 has been associated with tumor cell migration. Loss of CD73 from urothelial cells induces malignant alteration of these cells [29].

This constantly evolving involvement of multiple cell types that make up the TME of bladder cancer is summarized in Fig. 1.

Fig. 1.

Fig. 1.

Schematic representation of the tumor microenvironment of

bladder cancer. Tumor growth or tumor cell death is facilitated by interactions

between the different cell populations within the TME. Neutrophils and

macrophages have pro- and anti-tumor activity according to their phenotype.

CD4+ T cells may induce apoptosis of tumor cells directly or indirectly by

interacting with multiple immune cells, mainly CD8+ T cells. A balance

between T-reg cells and Th17 cells is crucial to maintaining the function of

CD8+ T cells. CAFs secrete multiple chemokines like TGF-

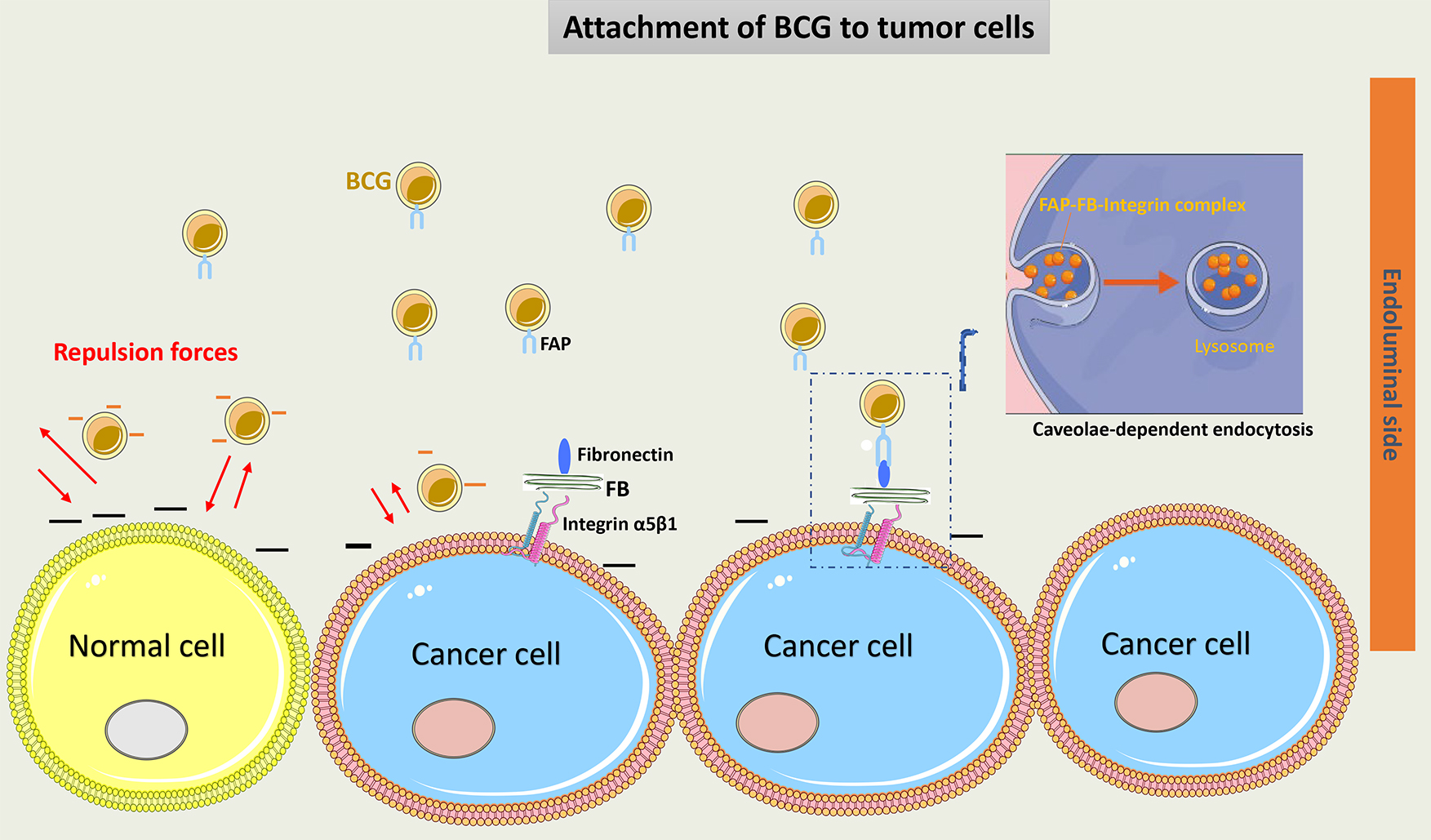

The attachment of BCG to urothelial cells is facilitated by two main mechanisms: a physicochemical mechanism and a ligand-dependent mechanism. The physicochemical process starts with injury induced to the glycosaminoglycan layer (GAG) on tumor cells, which may decrease the negative charge on their wall and thus increase BCG adherence to these cells [30]. The BCG cell membrane is negatively charged, which makes it repulsive to the normal urothelial cell membrane [31]. Interestingly, the use of drugs such as pentosane polysulfate or hyaluronic acid helps restore the GAG layer of urothelium and decrease BCG local effects. This suggests the GAG layer plays an important role in protecting normal urothelial cells from the BCG direct effect [32, 33]. Importantly, data has proven that BCG preferentially attaches to and enters only tumor cells [34].

Another important mechanism of BCG attachment to cancer cells is through the

Fibronectin Attachment Protein (FAP) present on the cell wall of BCG that binds

to fibronectin, a glycoprotein that is present on the membrane of cancer cells.

FAP is attached to

Interestingly, BCG binds to the carboxyl-terminal area of fibronectin, near the heparin-binding domain. This portion of fibronectin may be shielded by BCG from tumor proteases, enabling a better immune reaction against the tumor [39].

A suggested model of BCG attachment to tumor cells is represented in Fig. 2.

Fig. 2.

Fig. 2.

Schematic representation of BCG attachment to cancer cells.

Negative charges on the normal urothelial cell wall induce repulsion forces and

decrease BCG adherence to these cells. The GAG layer on tumor cells had a

decreased negative charge, thus increasing BCG attachment. Via a ligand-dependent

mechanism, FAP of the cell wall of BCG binds to fibronectin on cancer cells.

Fibronectin is attached to

Phagocytosis is an exclusive function of macrophages, but epithelial cells can, through different processes, acquire some capabilities to engulf particles. By secreting insulin-like growth factor 1 (IGF-1), macrophages modify the sort of particles that epithelial cells engulf [40]. It is still unknown how bladder cancer cells acquire the ability to internalize BCG.

In a 3D model, BCG has been found to be internalized by tumor cells and not benign urothelial cells. When BCG is internalized, it goes through the superficial layers of tumor cells (1–4 layers). This selective model of BCG internalization helps explain the absence of BCG in the bladder biopsy of tumor-free patients [41].

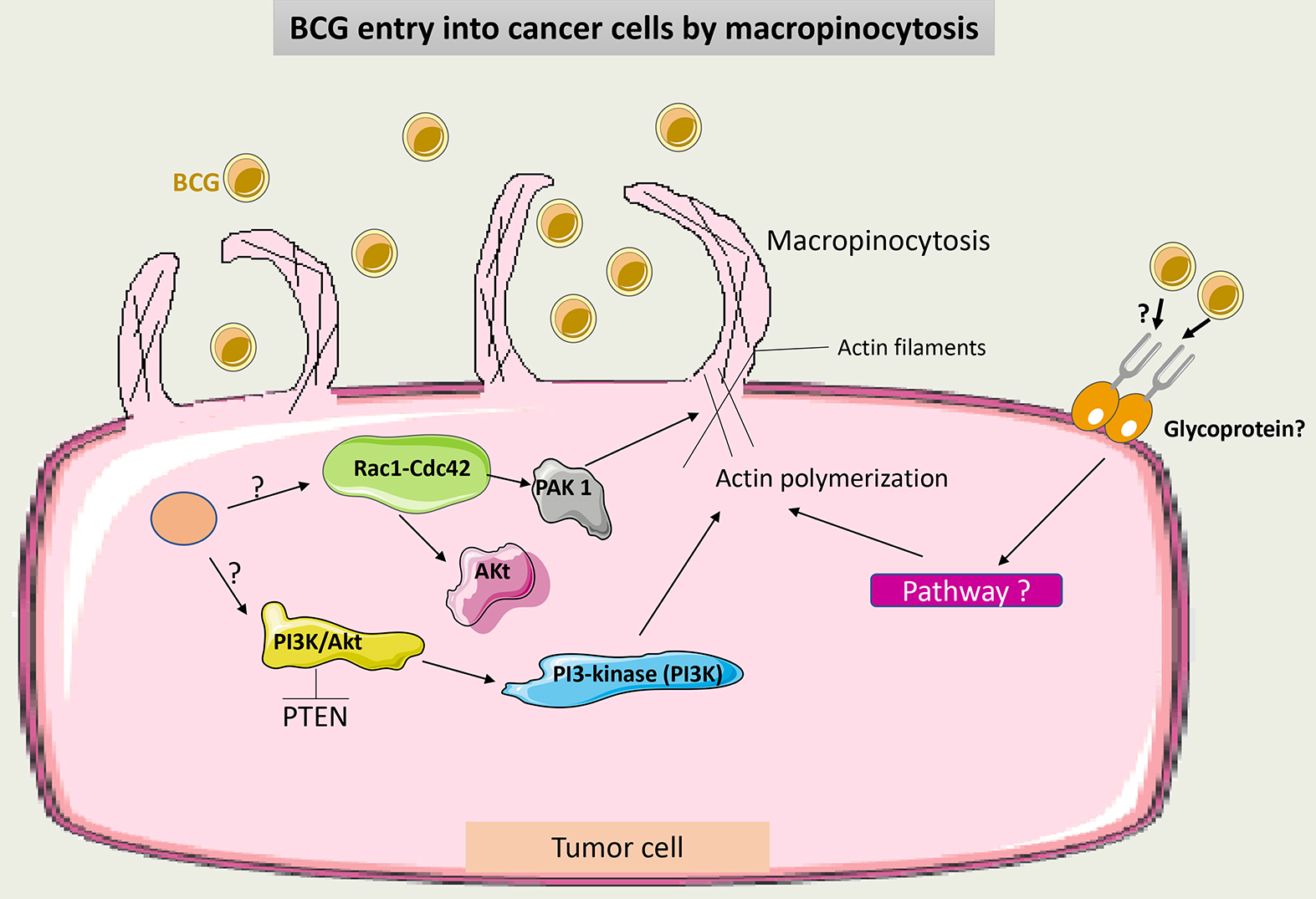

Classically, BCG internalization was referred to as a receptor-dependent process through FAP-FB-Integrin endocytosis [37]. Recently, it was demonstrated that BCG may also enter tumor cells via macropinocytosis, a process that is not receptor-mediated. Macropinocytosis is performed by the ruffling and reorganization of the cell membrane, which allows the influx of BCG into tumor cells. This depends on the small GTPases Rac1-Cdc42 cytoskeleton proteins and their effector kinase p21-activated kinase 1 (Pak1) [42]. Phosphatase and tensin homolog (PTEN) mutations in some tumor cells promote more entry of BCG into these cells and thus make BCG more effective. PTEN inhibits the phosphoinositide-3-kinase-protein kinase B/Akt (PI3K-Akt) pathway, thus modulating the actin cytoskeleton and allowing cell membrane rearrangement [43].

It is still unclear what induces macropinocytosis following BCG administration. A suggested hypothesis is that tumor mutations may activate the previously described pathway involved in this process, and BCG may potentiate this activation. Interestingly, the macropinocytosis of some viruses is dependent on glycoprotein receptors, which may also be the case with BCG [44].

Fig. 3 summarizes the factors involved in BCG entry into tumor cells by macropinocytosis.

Fig. 3.

Fig. 3.

Schematic representation of BCG uptake via macropinocytosis in cancer cells. Through intracellular signaling, Cdc42/Rac1-dependent activation of PAK1 induces membrane ruffling and macropinocytosis. Macropinocytosis also occurs through the conversion of membrane phosphoinositide by PI3K via the PTEN/PI3K/Akt pathway. It is not clear if macropinocytosis of BCG may occur additionally in a receptor-dependent manner. PAK1, p21-activated kinase 1; PTEN, phosphatase and tensin homolog; PI3Ks, phosphoinositide 3-kinases; BCG, Bacillus Calmette-Guérin.

BCG internalization is dependent on cancer cell differentiation. It has been

shown that high-grade tumor cells can internalize BCG more efficiently than

low-grade tumor cells. Subsequently, these cells secrete a high amount of IL-6

[45]. Recently, IL-6 has been correlated with the interruption of adaptive

immunity and enhancing cancer cell survival [46]. IL-6 secreted by cancer cells

may enhance the expression of

After BCG entry into tumor cells, specific chemokines (Interferon Gamma-induced

Protein 10 (IP-10) and IL-8) and cytokines (tumor necrosis factor-alpha

(TNF-

Also, after internalizing BCG, tumor cells express more Intercellular Adhesion Molecule 1 (ICAM-1) and major histocompatibility complex (MHC) Class II on their surface. These changes increase the immunogenicity of the tumor cells and allow them to act as antigen-presenting cells (APCs) for specific CD4+ T cells to activate the adaptive immune reaction [50, 51, 52].

Briefly, the internalization of BCG is essential to the antitumor response and

may be considered one of the first steps toward the emergence of an effective

immune reaction against bladder cancer. Enhancing BCG entry into tumor cells by

inhibiting cathelicidin induces a reduction in tumor cell proliferation [53].

Recently, the role of the human

BCG acts as a pathogen-associated molecular pattern (PAMP) molecule to activate

the pattern recognition receptor (PRR) on the surface of different cells,

including antigen-presenting cells (APC), such as dendritic cells (DCs), and

macrophages. Other important cells involved in the response to BCG are natural

killer (NK) cells and neutrophils [57]. After 6 hours of BCG instillation, most

of the leucocytes found in the urine are neutrophils (

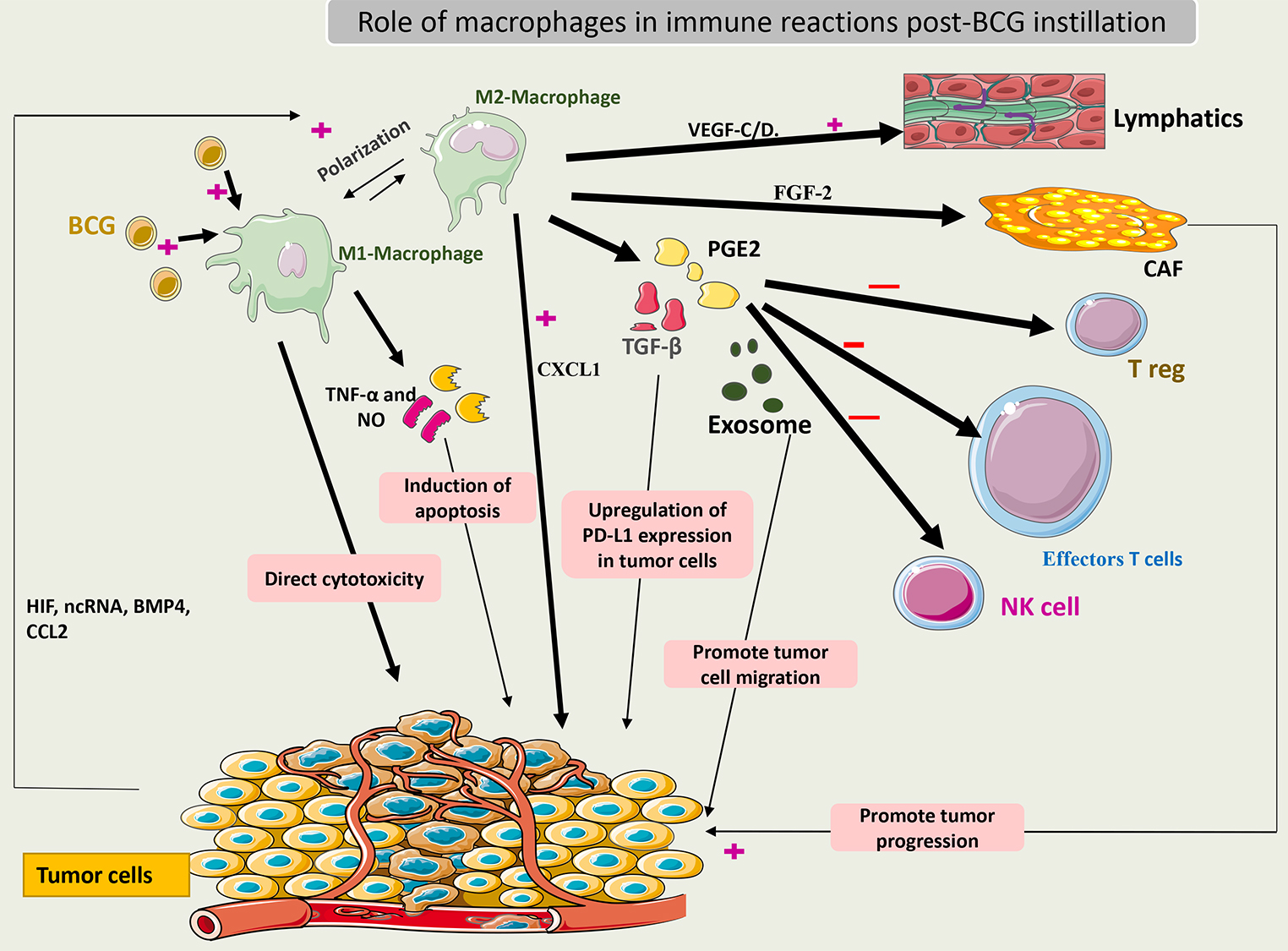

When activated, macrophages may have a direct cytotoxic effect on tumor cells or

an indirect effect through the secretion of TNF-

Interchange between the M1 and M2 macrophages is an important event in the TME of bladder cancer. This transition is dependent on immune system signals such as interaction with Treg cells and cytokines released by other immune cells. Some of these molecules are long non-coding RNAs (lncRNAs) and hypoxia inducing factor (HIF). Notably, CD163+ (markers of the M2 phenotype) was found in high numbers in BCG-unresponsive tumors [62]. Thus, these phenotypes may be related to BCG efficacy. Additionally, to escape from macrophage action, tumor cells may secrete bone morphogenetic protein (BMP4) and monocyte chemoattractant protein-1 (CCL2) to induce macrophage polarization to the M2 phenotype [63, 64].

M2 macrophages release TGF-

Recently, it was shown that macrophages could secrete fibroblast growth factor 2 (FGF-2) after exposure to BCG, which then stimulates fibroblasts and promotes tumor progression. What remains unknown is how BCG changes the microenvironment factors towards the differentiation of macrophages to the M1 or M2 phenotype. Some theories suggest that the pre-BCG tumor microenvironment could drive this differentiation according to the tumor mutational burden [66].

Fig. 4 summarizes the role of macrophages in the immune response to BCG.

Fig. 4.

Fig. 4.

Schematic representation of the role of macrophages in the

immune response to BCG. Activated macrophages (M1) induce cytotoxic effects on

cancer cells by secreting TNF-

Cancer cells secrete IL-8, which recruits neutrophils to the tumor site [67].

Studies have shown that TNF-related apoptosis-inducing ligand (TRAIL) is secreted

in an abundant amount in the urine of patients treated with BCG and is

overexpressed on their neutrophils [68]. BCG induces neutrophils to secrete TRAIL

by binding to Toll-like receptors (TLRs) 2 and 4, which provokes the selective

apoptosis of tumor cells [69]. Expression of TRAIL on other immune cells like

macrophages and T cells is dependent on the secretion of IFN-

Release of TRAIL from intracellular components of neutrophils is facilitated

through protease action. Evidence has shown that TRAIL coexists in high amounts

in neutrophils even before their exposure to BCG. Components of the BCG cell wall

are capable of inducing TRAIL secretion, but the exact intracellular signaling of

this process remains unknown. Theories suggest that intracellular processing of

BCG within neutrophils may help in the release of TRAIL and not just through the

TLR stimulation process. Neutrophils also secrete cytokines (IL-1, IL-6, IL-8,

IL-12, and TNF-

Emerging data has shown that neutrophils can also exert their direct cytotoxic

activity on tumor cells through the secretion of TNF-

BCG may also promote the formation of neutrophil extracellular traps (NETs), which can lead to tumor cell cytotoxicity by interrupting their cell cycle. Additionally, NET can help in the recruitment of T cells and potentiate the immune response. The process by which BCG induces NET formation remains unknown [72].

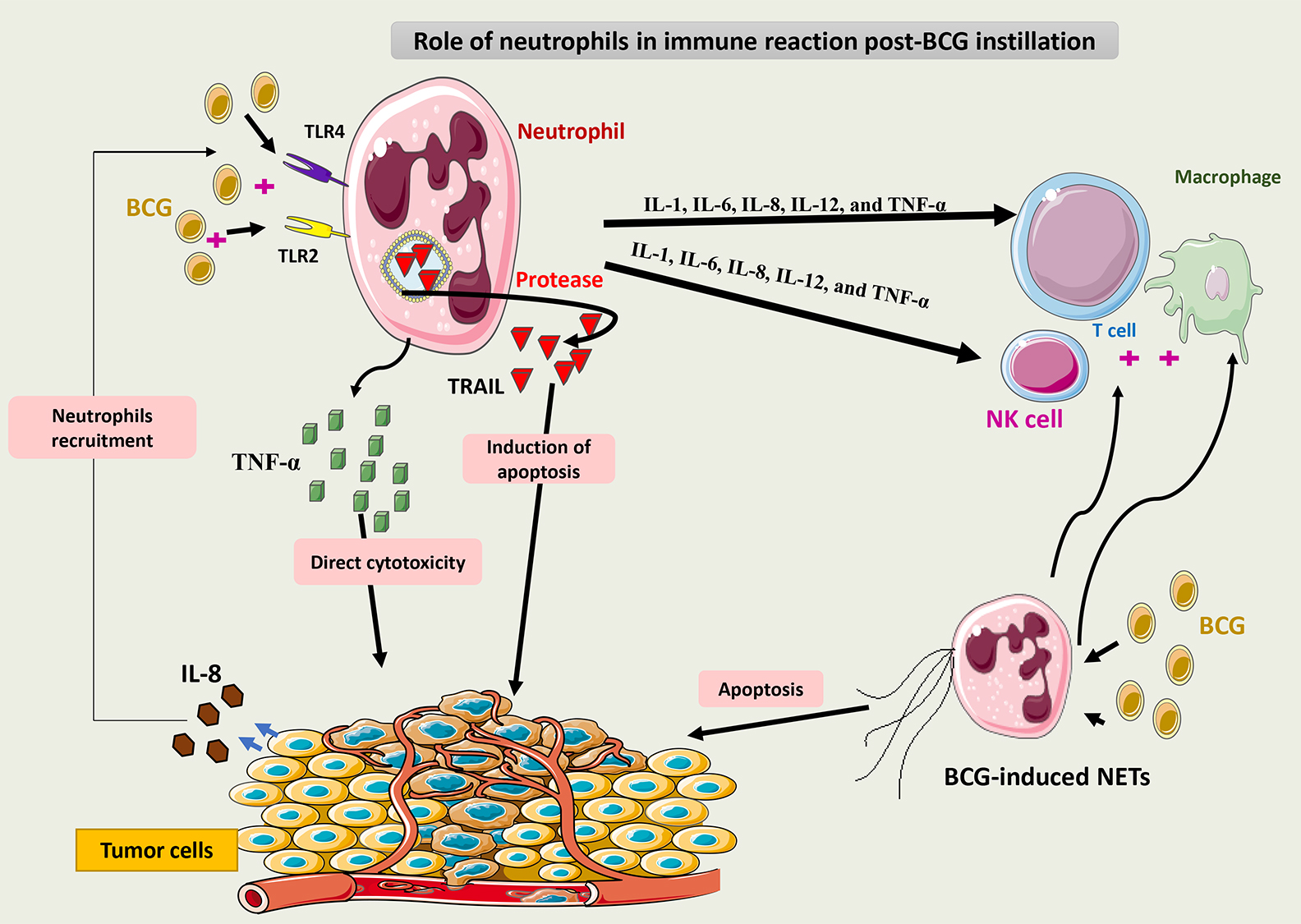

Fig. 5 summarizes the role of neutrophils in the immune response to BCG.

Fig. 5.

Fig. 5.

Schematic representation of the role of neutrophils in the

immune response to BCG. Via binding to TLR2 and 4, BCG induces neutrophils to

secrete TRAIL, which is selectively cytotoxic to tumor cells. Neutrophils may

also release cytokines such as IL-1, IL-6, IL-8, IL-12, and TNF-

Using in vitro and in vivo models, it has been demonstrated

that natural killer (NK) cells have an important role in inducing tumor death

after BCG instillation [73]. BCG-activated NK cells (BAKs) express a phenotype of

CD3-/CD56+. BAKs induces tumor cell death through perforin release [74].

BCG-infected monocytes interact with NK cells via IL-12 and IFN-

Recently, an emerging therapy (ALT-803) focusing on the activation of NK cells has been used to treat NMIBC patients. ALT-803 is an IL-15 cytokine antibody fusion protein that functions as a “superagonist” to enhance NK cells and CD8+ T cell activity. Efficacy and tolerability were acceptable when intravesical ALT-803 was used in preclinical and clinical trials. In addition, ALT-803 may enhance the efficacy of BCG if it were used as a combination therapy [76]. The efficacy of this doublet therapy (ALT-803+ BCG) needs to be validated in randomized trials.

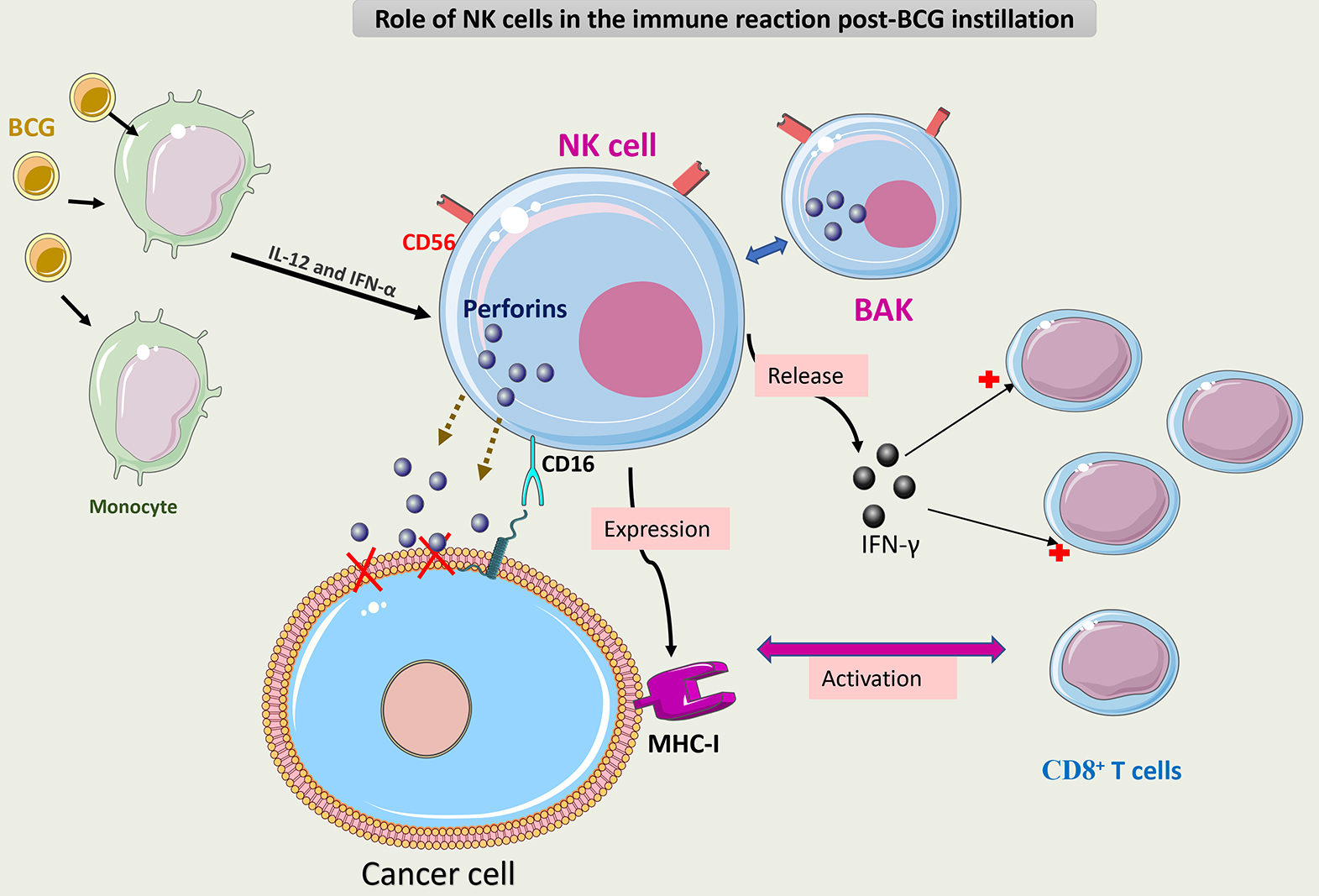

Fig. 6 summarizes the role of NK cells in the immune response to BCG.

Fig. 6.

Fig. 6.

Schematic representation of the role of NK cells in the immune

response to BCG. BCG-activated NK cells (CD3-/CD56+) (BAK) execute antitumor

activity through three mechanisms. The first mechanism is via direct cytotoxicity

caused by the secretion of perforin through CD16 receptor activation. The second

mechanism is via release of IFN-

Dendritic cells (DCs) derive from common myeloid progenitors. DCs acquire, through a special differentiation process, the ability to activate T cells. Moreover, DCs can interact with NK cells and macrophages. DCs helps to present antigens to CD8+ T cells and sustain their function through IL-12 production [77]. Another role of DCs is to activate NKs, which may induce apoptosis in tumor cells through direct cytotoxicity. In this manner, DCs are involved in both innate and adaptive immunity [78].

BCG increases the lifespan of DCs through nuclear factor-

In a mouse model, a new isolate of Mycobacterium tuberculosis called MTBVAC was used intravesically to treat bladder tumors. It was shown that MTBVAC increases the activation of CD8+ T cells by interacting more efficiently with DCs than traditional BCG to induce a stronger immune response. Furthermore, as DCs are necessary to induce adequate T-cell activation, other methods to ensure DC activation may be useful in BCG-unresponsive cases. Interestingly, MTBVAC expresses attachment proteins that do not exist on BCG, such as ESAT6 and CFP10, suggesting that the attachment capability of mycobacterium is also a crucial element for better immune cell activation [82].

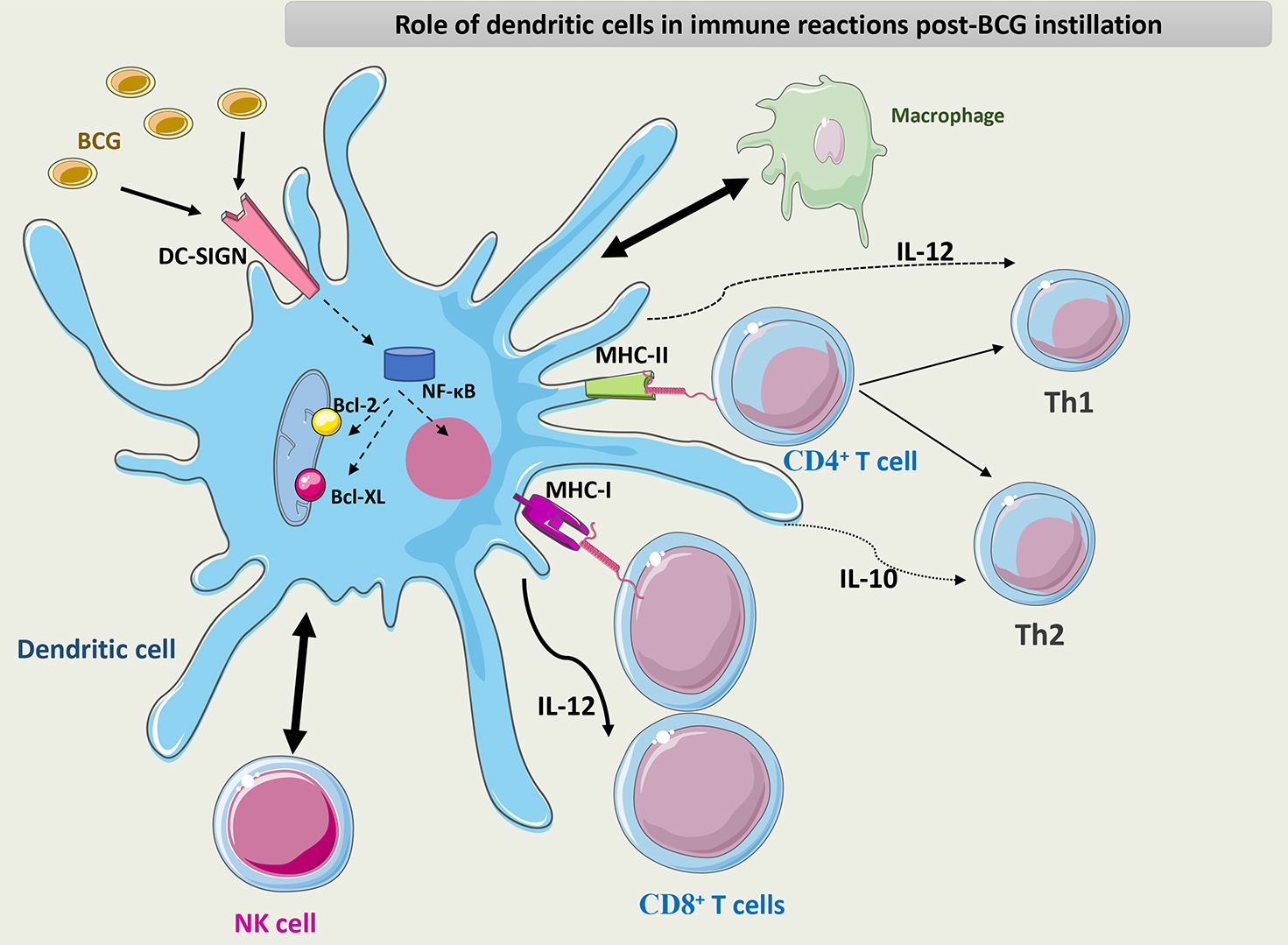

Fig. 7 summarizes the role of DCs in the immune response to BCG.

Fig. 7.

Fig. 7.

Schematic representation of the role of DCs in the immune

response to BCG. DCs interact with macrophages and NK cells through different

chemokines and cytokines. DCs activate CD8+ T cells through their APC

capacity and maintain the differentiation of CD4+ T cells into the Th1

phenotype through the secretion of IL-12. BCG interacts with PRRs such as DC-SIGN

on the surface of DCs and induces NF-

Both CD4+ T cells and CD8+ T cells are important effectors in the response to BCG therapy, as experiments have shown that BCG is ineffective if either T cell subset is absent [83]. The balance of the Th1/Th2 phenotype of CD4+ T cells is crucial to inducing an adequate anti-tumor immune response to BCG. In a mouse model, BCG was completely ineffective in IL-12 knockout mice (Th1 cells inactive) and had enhanced efficacy in IL-10 knockout mice (Th2 cells inactive) [84].

It is not clear yet what constitutes the key antigenic target(s) for T cells

after BCG administration. It is unlikely to be tumor antigens themselves in a

classic MHC-I antigen-specific response since related cancers (particularly CIS)

in “sanctuary” sites, such as in the upper urinary tract, fail to disappear

with resolution of bladder CIS treated with BCG unless BCG is dripped directly

into the upper urinary tract. Increasingly, other data show that the antigen

target can be BCG itself. Intravenously administered BCG generates a powerful

immune response against bladder cancer if given before intravesical instillation

in an experimental model. This may indicate that previous exposure to BCG

triggered rapid and effective T cell infiltration of the tumor site [85]. BCG

activates most of the innate immune cells through direct action via the

IFN-

Additional data suggests that adaptive immune response after BCG relies on

non-classical tumor-specific T-cell activation. Recently, two specific types of T

cells were identified in the TME after BCG instillation: CD4+ T cells with

MHC class II-restricted bladder tumor antigen and gamma delta T cells

(

CD8+ T cells are important effector cells in tumor cytotoxicity and, thereafter, adequate BCG therapy. Unfortunately, if BCG stimulates CD8+ T cells continuously through several processes as described above, then CD8+ T cells may become anergic or, in other terms, ‘exhausted’ with time. Exhaustion of CD8+ T cells leads to a decrease in their cytotoxic function and, thus, the escape of tumor cells from the immune response [92]. Current data has shown that high-grade recurrence after BCG therapy is related to T-cell anergy. Apparently, this is associated with a high mutational burden in tumors before instillation therapy [93].

An important concept has emerged recently in bladder cancer pathogenesis known as field cancerization. A lineage is considered cancerized if it exhibits some but not all of the phenotypic traits required for malignancy. This area depends on and influences the TME. High-field cancerization has been associated with CD8+ T cell ‘exhaustion’ after BCG therapy overwhelming these effector cells with neoantigens during the tumor elimination process. A recent study, including genomic and proteomic analyses of 136 patients with HR NMIBC, assessed this concept. During the first nine months of monitoring, patients with greater levels of field cancerization had a significant decline in high-grade recurrence-free survival (HG-RFS), suggesting an association between higher levels of field cancerization and worse patient outcomes in the short term. It is noteworthy, nevertheless, that this association did not maintain statistical significance across extended follow-up times, and no correlation was found with either progression-free survival or overall recurrence-free survival. Despite this, the results suggest that the level of field cancerization may be a useful diagnostic for identifying individuals who are more likely to benefit from closer surveillance [94].

T-regs exerts immunosuppressive effects on CD8+ T cells following BCG therapy. The exact mechanism of T-reg activation in this setting is not yet understood. Data has shown that in BCG failure cases, tumors were highly infiltrated with Treg CD4+, FOXP3+, and CD25+ T cells [95]. In a clinical study of 71 patients with NMIBC treated with BCG, a high count of T-regs in tumor sites had a negative prognosis in terms of survival outcomes [96]. More data is still needed to show if T-reg suppression can be a major target for novel therapy for NMIBC.

The role of B cells in immunological responses to BCG therapy is not yet clear. Based on IHC analysis, bladder tumors that are highly infiltrated with B cells recurred less, suggesting that B cells have a protective effect against tumors [97]. However, patients with high IgG against purified protein derivatives (PPD) (antigens of BCG) were associated with a higher tumor recurrence rate. The exact causal relationship between the humoral response and the local immunological response in the bladder mucosa is yet unknown, which may explain these contradictory results [98]. It will be important to demonstrate if there is a ‘blood-bladder barrier’ that regulates immune cell influx toward the mucosa in order to ascertain the role of humoral responses to BCG.

A unique subgroup of Th cells known as Th17 cells has been shown to infiltrate

bladder cancer. Although data suggests that these cells may have protumor

activity, the exact role of these cells is still up for debate. While the precise

association between a high concentration of Th17 cells and the stage and grade of

bladder tumors is unknown, some evidence points to a rise in Th17 percentage in

high-grade tumors [99, 100]. A high level of IL-17 was also found in bladder

cancer patients [99]. Since IL-17 receptors are present on both tumor cells and

tumor-associated stromal cells, IL-17 directly influences these cells to

encourage the growth of tumors. IL-17 increases IL-6 production, which activates

multiple signaling pathways and activator of transcription (Stat) 3, which in

turn upregulates proangiogenic genes [101]. Recent data showed that IL-17 levels

were associated with higher clinical stage and lymph node metastasis in patients

diagnosed with bladder cancer [102]. Interestingly,

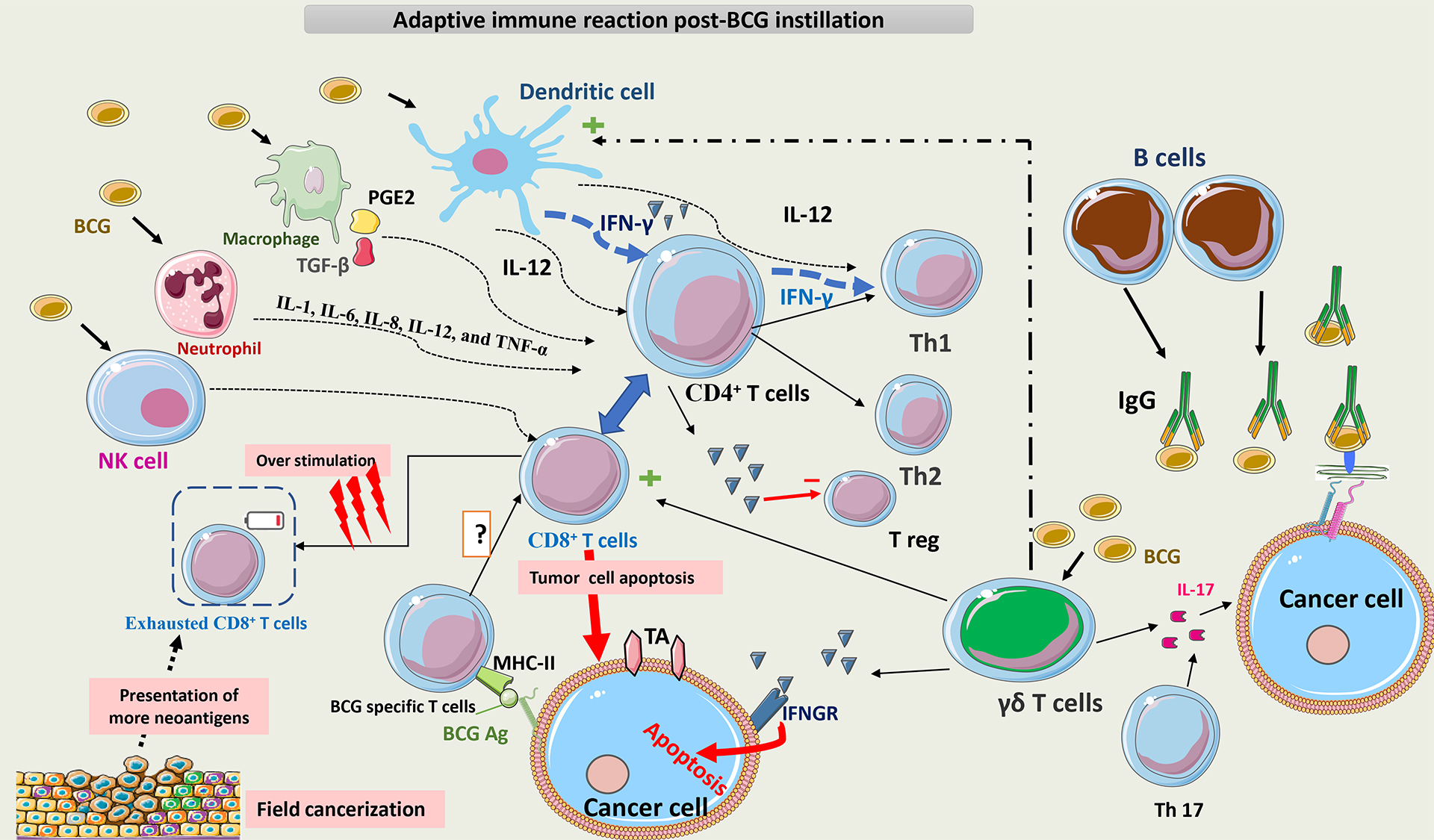

Fig. 8 summarizes the adaptive immune reaction post-BCG instillation.

Fig. 8.

Fig. 8.

Schematic representation of adaptive immunity post BCG

instillation. BCG interacts with multiple cells of innate immunity, such as NK

cells, macrophages, neutrophils, and DCs. The main APCs for T-cells are DCs,

which act directly and indirectly on T-cells via cytokines to promote the

differentiation of CD4+ T cells toward a Th1 phenotype. Later on, T cells

become the main secretors of IFN-

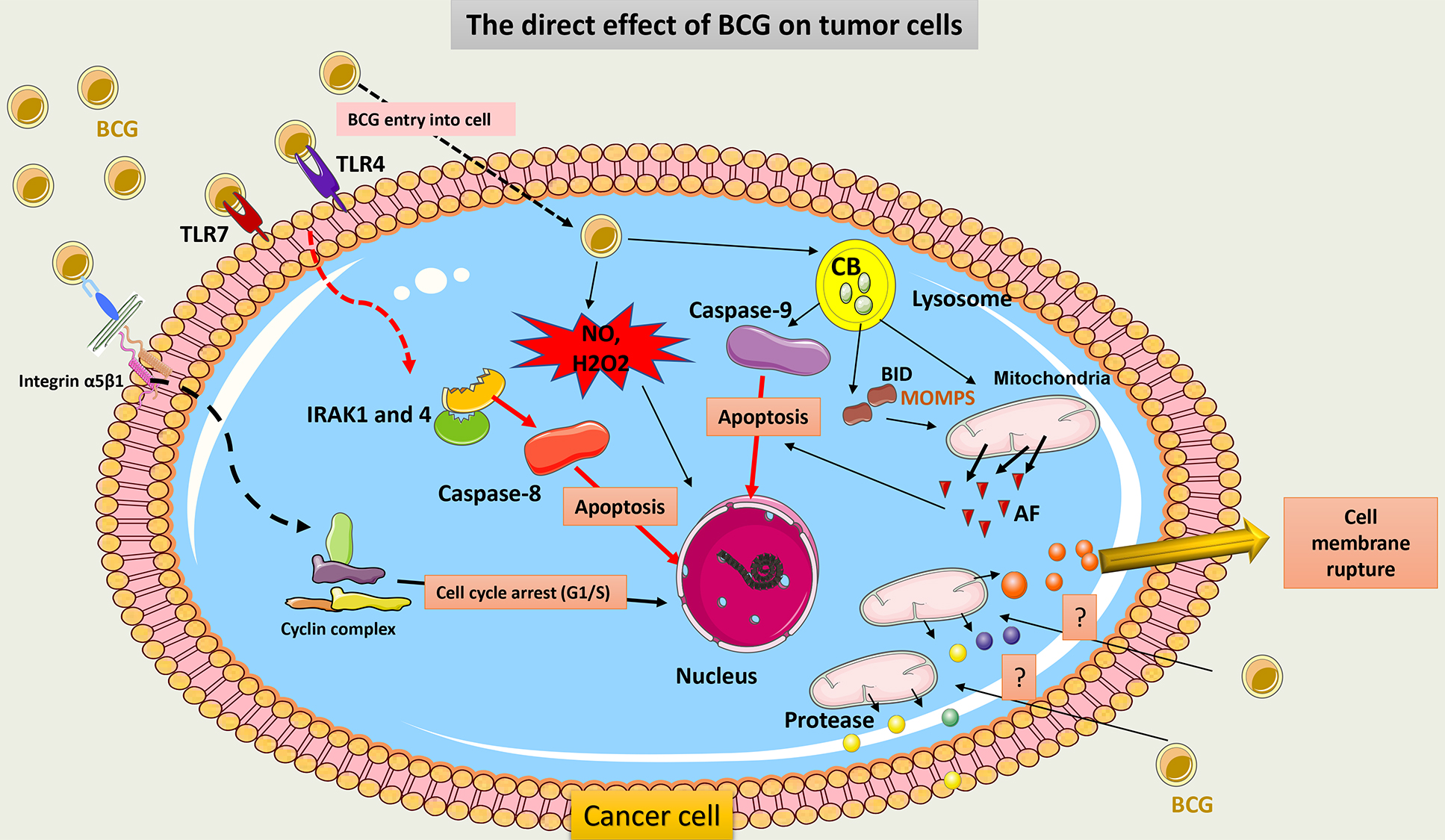

BCG directly induces tumor cell death through several mechanisms. First, BCG provokes overexpression of TLR4 and TLR7 on the surface of cancer cells. Then, apoptosis is triggered through a caspase-8-dependent pathway. This pathway contains IL-1 receptor-associated kinase (IRAK) 1 and 4, important molecules in TLR signaling [14, 105]. Second, after BCG internalization into tumor cells, cathepsin B (CB) protein, a lysosomal hydrolase, increases and activates caspase-9, which induces cell apoptosis. Also, CB may allow truncation of pro-apoptotic Bcl-2 protein (BID), or pro-apoptotic Bcl-2 protein, which results in increasing mitochondrial outer membrane permeability (MOMP) and the release of multiple apoptotic factors [106]. Third, BCG attaches to tumor cells by an integrin-mediated process that can inhibit cell cycle progression from the G1 to S phase. This may be due to the downregulation of the synthesis of cyclin D1 and cyclin E [107].

An additional mechanism of tumor cell death following BCG therapy is necrosis. High mobility group box 1 (HMGB1) has been found to be released in a high amount from bladder tumor cells following BCG therapy. These serve as necrosis markers [108]. It is currently unclear how BCG causes structural cell membrane damage in tumor cells that results in cell rupture. It has been suggested that in cancer cells, necrosis may be due to mitochondrial rupture following activation of the receptor-interacting protein kinase 1 (RIPK1) mediator [109].

Finally, BCG can induce the generation of oxidative stress products like NO within tumor cells that contribute to cell damage. After BCG internalization, inducible nitric oxide synthase (iNOS) activity increases, and NO is released in high amounts [110]. Also, BCG contributes to the production of hydrogen peroxide (H2O2), which may increase the function of iNOIS and thus NO production [111].

Fig. 9 summarizes the direct cytotoxic effect of BCG on cancer cells.

Fig. 9.

Fig. 9.

Schematic representation of the direct cytotoxic effect of BCG

on cancer cells. BCG binds to TLR7 on tumor cells and induces subsequent

signaling involving IRAK1 and 4 molecules to activate caspase-8 and promote the

apoptosis of tumor cells. BCG internalization within tumor cells induces

activation of CB within the lysosome, which activates capsase-9 signaling and

induces cell apoptosis. CB also induces truncation of BID to release AF from

mitochondria. Through its adhesion to integrin on tumor cells, BCG inhibits the

cell cycle transition from the G1 to the S phase and thus promotes cell death.

Cell membrane rupture may occur post-BCG exposure due to the release of a huge

amount of protease from the mitochondria. BCG can further induce the production

of potent ROS (NO and H2O2) via the activation of iNOS, which causes ROS-mediated

cell injury. TLR, Toll-like receptors; IRAK, IL-1 receptor-associated kinase; CB, Cathepsin B; BID, pro-apoptotic Bcl-2 protein; AF, apoptotic factors;

MOMP, mitochondrial outer membrane permeabilization; HMGB1, High mobility group

box 1; H2O2, hydrogen peroxide; iNOS, induce-NO synthase; NO, nitric oxide; ROS,

reactive oxygen species; Integrin

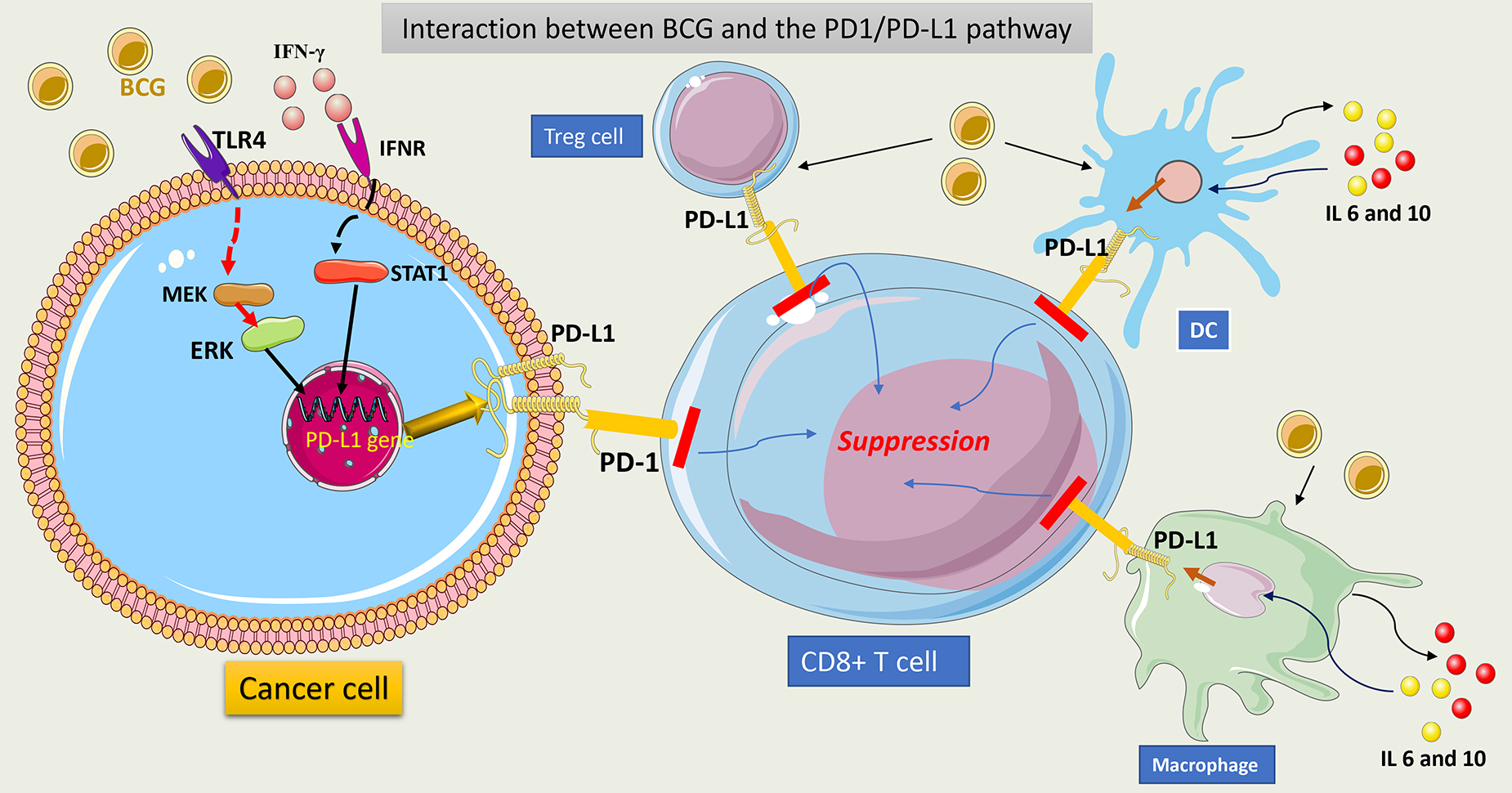

Programmed Cell Death Protein 1 (PD-1) is an important protein on T cells, which, by interaction with programmed Cell Death Ligands 1 (PD-L1) on cancer cells, may cause inhibition of T cell function and suppression of the antitumor response. Tumor cells use this mechanism to escape immune control. Data show that high PD-L1 expression on tumor cells was associated with a higher tumor stage and a lower response to BCG (PD-L1 expression of 7% in pTa tumors, 16% in pT1, and 45% in carcinoma in situ (CIS) tumors) [112, 113].

BCG affects PD-L1 expression on the tumor cell surface by activating TLR4 on

these cells and increasing IFN-

The prognostic role of overexpression of PD-L1 following BCG therapy was assessed in 141 patients with high-grade NMIBC. Interestingly, PD-L1 expression decreased post-BCG therapy in BCG-refractory cases and did not correlate with recurrence or progression [120]. This was contradictory to previously published reports on the topic [117, 119]. Data that assesses PD-L1 expression among BCG responders and non-responders has demonstrated that the PD-L1 expression rate before BCG therapy was more than 25% in BCG non-responders (n = 32) vs. BCG responders (less than 5%) (n = 31). After therapy, PD-L1 gene expression remained constant. This suggests that the response to BCG therapy may be more dependent on the initial PD-L1 expression in tumor cells [121]. The explanation for the contradictory results about PD-L1 expression between studies using cell culture models and clinical data is that the sample size in clinical studies was small, with variable regimens and BCG strains used, and thus the data was too heterogeneous to allow making a formal conclusion. Furthermore, PD-L1 expression is a dynamic process that changes with time after BCG therapy, and analyzing one measurement at a time leads to bias. Several phase II and III trials are ongoing to assess the role of PD-L1 inhibitors alone or in combination with BCG in the management of BCG-unresponsive disease [122]. Plans are also underway to test PD-1/PDL-1 inhibitors with BCG in previously untreated NMIBC patients. This data will help to resolve previous contradictions in a real-world setting.

BCG can induce PD-L1 expression on T-reg cells, making them a non-classic source

of PD-L1-expressing cells. This contributes to additional inhibition of T cells.

Extrapolated data from in vitro studies suggests that BCG acts by

inducing the secretion of IFN-

Furthermore, BCG provokes the secretion of IL-6 and IL-10 from macrophages and DCs, which may drive back signal transducer and activator of transcription 3 (STAT 3) phosphorylation and then overexpression of PD-L1 on APCs. This can result in further T-cell function inhibition [124]. In cell line culture, inhibition of STAT 3 decreases PD-L1 expression on tumor cells and enhances the antitumor response [125]. This may be another potential target to induce a better BCG response.

Fig. 10 summarizes the interaction between BCG and the PD1/PDL1 pathway.

Fig. 10.

Fig. 10.

Schematic representation of interaction between BCG and

PD1/PDL1 pathway. BCG interacts with TLR4 on tumor cells and upregulates the

PD-L1 gene via activation of the MAPK (MEK)/ERK/STAT1 pathway. This

induces PD-L1 overexpression in tumor cells. Secreted IFN-

The long-term efficacy mechanism of BCG is important to reveal. It’s unclear if immune surveillance or only the elimination of tumor cells contributes to the long-term response to BCG therapy. Pathological analyses of the bladder mucosa following a few months of BCG instillation have shown that while the quantity of T-cell lymphocytes decreased, the inflammatory response persisted [126]. A positive BCG DNA has been identified in 4.2%–37.5% of biopsies taken up to 24 months after intravesical instillation [127]. Additionally, local cytokine production within the mucosa persists for up to 21 months following therapy, indicating that local immune reactions continue even after cessation of instillations [128]. Further investigation is needed to assess the long-term immune response to BCG; this will add important information if tumor recurrence is related to an immune mechanism or the actual reactivation of senescent cancer cells.

Trained immunity (TI) is the process where innate immune cells undergo

functional reprogramming in response to multiple antigens; thus, these cells

respond more vigorously in subsequent antigen encounters. It was extremely

difficult to comprehend that TI can endure for years because it has only occurred

in cells with a limited lifespan (

In a bladder cancer model, engineered BCG with high expression of cyclic-di-AMP (c-di-AMP), a PAMP that provokes type 1 IFN secretion, can enhance the induction of TI and the antitumor response to BCG [133]. Modifying epigenetic processes involved in TI may increase the long-term systemic innate immune response after BCG therapy, hence augmenting the anticancer effect of BCG in NMIBC.

Despite the use of BCG therapy for NMIBC for decades, its exact mechanism of action remains unknown. New data has emerged, especially describing the direct cytotoxicity effect of BCG on tumor cells via multiple processes and the interaction of BCG with the PD-1/PD-L1 pathway. The latter mechanism has led to the implementation of ongoing clinical trials combining PD-1/PD-L1 inhibitors with BCG for the treatment of NMIBC. In the long run, however, it may very well be that BCG works so well against NMIBC precisely because it evokes so many pleiotropic anti-tumor actions. Nonetheless, eliciting the complex details involved in BCG’s mechanism of action along with the molecular signaling involved in these aggressive tumors will identify several novel strategies for potentially improving bladder cancer treatment.

MAC: conceptualization, data interpretation, methodology, writing-original draft preparation. YL: conceptualization, methodology, writing–review & editing. ID: data interpretation, writing–review & editing. MAO: conceptualization, methodology, data interpretation, writing–review & editing, supervision. All authors read and approved the final manuscript. All authors have participated sufficiently in the work and agreed to be accountable for all aspects of the work.

Not applicable.

Parts of the figures were drawn using Servier Medical Art, licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 3.0 Unported License (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/3.0/).

This research received no external funding.

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

Publisher’s Note: IMR Press stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.