1 Institute of Cerebrovascular Diseases Research and Department of Neurology, Xuanwu Hospital of Capital Medical University, 100053 Beijing, China

2 Beijing Institute of Brain Disorders, Collaborative Innovation Center for Brain Disorders, Capital Medical University, 100069 Beijing, China

†These authors contributed equally.

Abstract

microRNA-494 (miRNA-494) plays a key role in neuroinflammation following cerebral ischemia. We aimed to assess miRNA-494 levels as a biomarker for predicting acute ischemic stroke (AIS) severity and outcomes.

miRNA-494 levels in peripheral lymphocytes were measured using reverse transcription-quantitative polymerase chain reaction. Least Absolute Shrinkage and Selection Operator (LASSO) regression was employed to identify variables for multivariate logistic regression analysis. Univariate and multivariate logistic regression were conducted to assess the association between miRNA-494 levels and both AIS outcomes and stroke severity on admission. The primary outcome was defined as an excellent prognosis (modified Rankin Scale score of 0 or 1). The secondary outcome was milder stroke severity at admission (National Institutes of Health Stroke Scale score <15).

High miRNA-494 expression in patients aged <65 years predicted excellent AIS outcomes (odds ratio (OR) = 2.800 [1.120–7.002], p = 0.028, n = 105). In these patients, miRNA-494 levels predicted excellent outcomes for those who did not receive recanalization therapy (continuous: OR = 8.938 [2.123–62.910], p = 0.010; categorical: OR = 5.200 [1.480–20.773], p = 0.013). Elevated miRNA-494 levels were also linked to milder stroke severity (continuous: OR = 2.586 [1.024–6.533], p = 0.044; categorical variables: OR = 3.514 [1.501–8.230], p = 0.004, n = 205).

Increased miRNA-494 expression in lymphocytes predicts excellent outcomes in patients aged <65 years with AIS. Higher miRNA-494 levels are associated with milder stroke on admission.

Keywords

- microRNAs

- ischemic stroke

- lymphocytes

- prognosis

Cerebral ischemic stroke is one of the leading causes of mortality and disability worldwide [1, 2]. Currently, approximately half of patients with acute ischemic stroke (AIS) show no obvious abnormalities on computed tomography (CT) or magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) [3]. Some patients exhibit only atypical symptoms and commonly used assessment tools, such as the National Institutes of Health Stroke Scale (NIHSS), Glasgow Coma Scale, and modified Rankin scale (mRS), are often insufficient for accurate evaluation [4]. Consequently, the precise diagnosis of AIS remains an urgent challenge. Even among patients who receive recanalization therapy, only approximately one-third achieve excellent outcomes after 3 months [5]. Therefore, there is a pressing need to identify a reliable indicator to predict AIS prognosis and aid in more timely decision-making.

In recent years, non-coding RNAs, especially microRNAs (miRNAs), have garnered significant attention in biomarker research [6]. miRNAs are small non-coding RNA molecules (about 17–25 nucleotides) that help control gene expression by turning it down at the post-transcriptional level [7]. miRNA-mediated regulation of gene expression represents a key epigenetic mechanism in the nervous system [8]. After AIS, 24 types of miRNAs in endothelial progenitor cells were correlated with subacute stroke process and prognosis [9]. In addition to the cytoplasm and nucleus, miRNA and messenger RNA (mRNA) enrichment in mitochondria following cerebral ischemia or hypoxia can contribute to ischemia-reperfusion injury [10]. Growing evidence suggests that miRNAs may serve as important biomarkers for the diagnosis and prognosis of AIS and as potential therapeutic targets [11]. For instance, Sonoda et al. [7] identified seven serum miRNAs that could predict AIS risk before its onset.

Among these promising miRNAs, miRNA-494 has been associated with ischemic and neurodegenerative diseases [12]. In endothelial cells, miRNA-494 pretreatment reduces endoplasmic reticulum stress and increases cell viability [13]. In cardiomyocytes, miRNA-494 inhibits vascular smooth muscle apoptosis under oxidative stress, thereby enhancing cardio-protection following estrogen treatment [14, 15]. miRNA-494 is thought to target both pro-apoptotic and anti-apoptotic proteins, ultimately activating the protein kinase B (Akt) pathway, which offers protection against ischemia/reperfusion (I/R) damage in the heart [16]. However, the specific pro-inflammatory mechanisms related to AIS remain unclear. Immune cells, such as lymphocytes and neutrophils, can infiltrate the central nervous system and worsen I/R injury [17]. Our laboratory findings revealed that intravenous miRNA-494 antagonists exacerbate acute cerebral ischemic injury, modulate the expression of multiple matrix metalloproteinase subtypes, and influence neutrophil infiltration during the post-stroke reperfusion phase, partly by targeting histone deacetylase 2 (HDAC2). Additionally, miRNA-494 antagonism inhibits Th1 cell transition-related neurotoxicity [18, 19, 20].

Despite this evidence, the expression of miRNA-494 in patients with AIS and its potential clinical applications have not yet been explored. In this study, we aimed to detect miRNA-494 levels in the peripheral blood lymphocytes of patients with AIS and assess its potential as a biomarker of stroke severity and clinical outcomes predictions.

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and approved by the Institutional Review Board (or Ethics Committee) of Xuanwu Hospital, Capital Medical University. This study included 345 patients diagnosed with AIS by experienced neurologists at the Emergency and Neurology Department of Xuanwu Hospital between November 2018 and September 2019, as well as 37 healthy volunteers. The time elapsed from symptom onset to hospital admission was also confirmed by experienced physicians through detailed medical history taking. This duration will be referred to as “time to hospital admission” and “onset-to-treatment time” in the following text. Inclusion criteria for AIS patients were: (1) diagnosis confirmed via brain MRI or CT; (2) evident neurological deficits (such as motor and/or sensory deficits on the opposite side, impairment of higher cerebral functions and homonymous hemianopia); (3) age

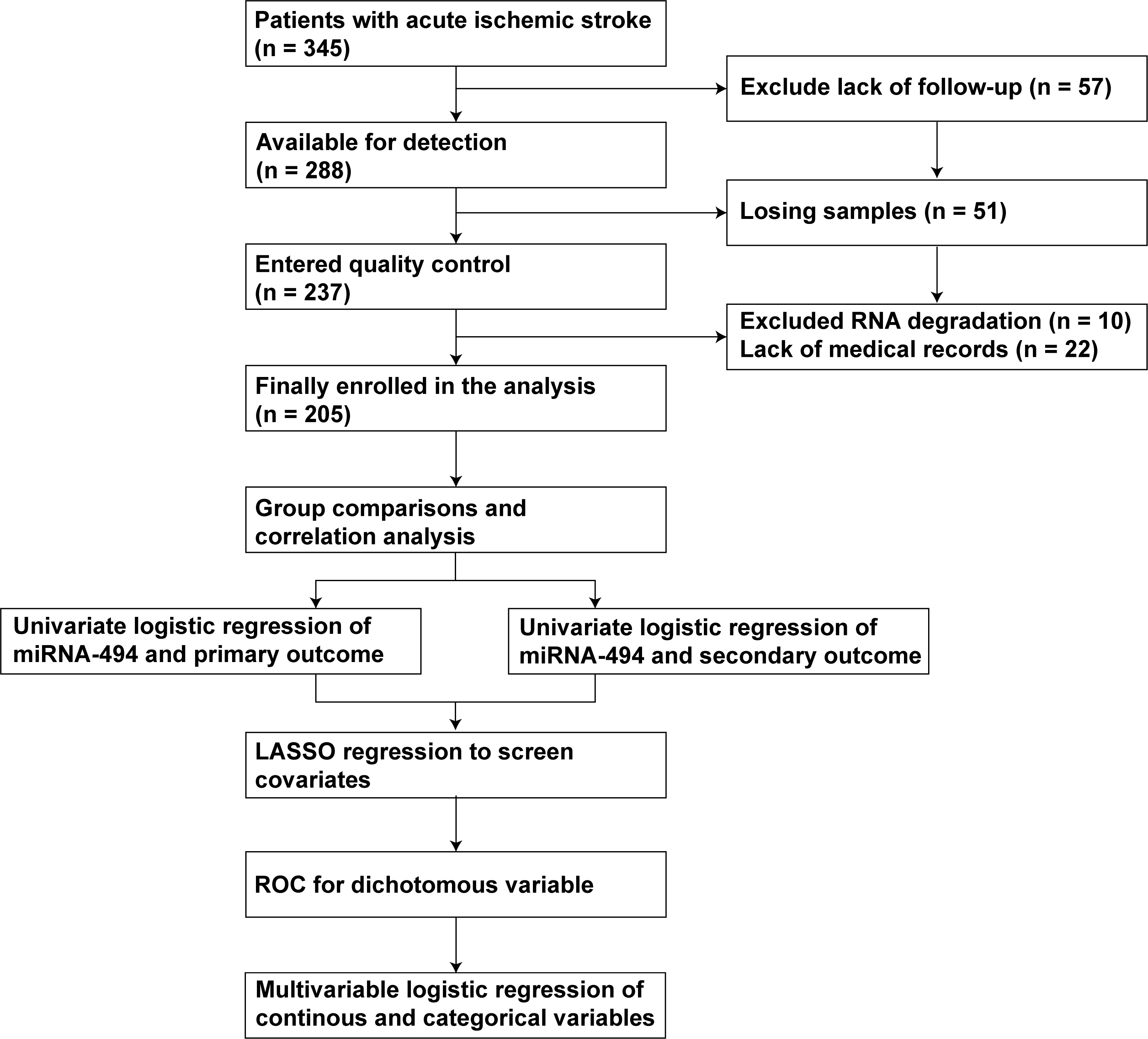

Fig. 1.

Fig. 1. Flow chart of this study. Abbreviation: miRNA-494, microRNA-494; LASSO, least absolute shrinkage and selection operator; ROC, receiver operating characteristic.

Stroke severity was evaluated using the NIHSS, where scores 0–5 indicated minor stroke, 6–10 mild stroke, 11–14 moderate stroke, and 15–42 severe stroke [21, 22]. After 3 months, the mRS was used to assess patient outcomes. The primary outcome was defined as an excellent outcome (mRS score

According to the Trial of Org 10172 in Acute Stroke Treatment (TOAST) criteria [28], AIS patients were classified into four subgroups for descriptive and analytical purposes (no patients fell under “other determined etiology”): large-artery atherosclerosis, cardioembolic infarction, lacunar infarct and undetermined etiology.

Hypertension is defined as a clinic systolic blood pressure

Peripheral venous blood from patients on admission and healthy volunteers was collected in ethylenediaminetetraacetic acid (EDTA) anticoagulant tubes. Lymphocytes were separated using the standard Ficoll-Paque Plus method. First, plasma and blood cells were separated through centrifugation. The blood cells were suspended in physiological saline and then carefully added along the wall of the centrifuge tube into the Lymphocyte Separation Medium (Haoyang Biotech, LTS1077, Tianjin, China). Following centrifugation, the lymphocytes from the middle layer were harvested and added to the red blood cell lysis solution (155 mM NH4Cl, 12 mM NaHCO3 and 0.1 mM EDTA, 12709101, 12600701, 10104201, Xilong Scientific Co., Ltd., Shantou, Guangdong, China). After vortexing and centrifugation, the pelleted cells were washed with physiological saline and transferred into new RNase-free EP tubes. The lymphocytes were finally suspended in 1 mL of TRIzol (Invitrogen Life Technologies, 15596026CN, Carlsbad, CA, USA) and stored at –80 °C until use. All samples were processed consistently throughout the study.

The samples were removed from –80 °C and allowed to thaw on ice; 200 µL of chloroform (10006818, Sinopharm Chemical Reagent Co., Ltd., Shanghai, China) was added to each EP tube, followed by vigorous shaking for 15 seconds and incubation at 25 °C for 15 minutes until phase separation was observed. The tubes were centrifuged (4 °C, 12,000 rpm, 15 minutes). Then, the upper aqueous phase was carefully transferred to a new RNase-free EP tube, and 500 µL of isopropanol (80109218, Sinopharm Chemical Reagent Co., Ltd., Shanghai, China) was added. The mixture was incubated overnight at –20 °C. The next day, the tubes were centrifuged again (4 °C, 12,000 rpm, 10 minutes). The supernatant was discarded, and the pellets were washed twice with 1 mL of 75% ethanol (10009218, Sinopharm Chemical Reagent Co., Ltd.). After removing the ethanol, the tubes were placed on a clean bench and air-dried at room temperature. Subsequently, 40 µL of diethylpyrocarbonate (DEPC)-treated water (Invitrogen Life Technologies, AM9920) was added to each tube to dissolve the RNA. The RNA purity and concentration were determined using a spectrophotometer, measuring absorbance ratios at 260/280 and 230/260. RNA integrity was assessed by agarose gel electrophoresis to check for any degradation.

The level of miRNA-494 in the peripheral blood lymphocytes of patients and volunteers was measured using RT-qPCR. First, cDNA was synthesized from total RNA using M-MuLV Reverse Transcriptase (P7040L; Enzymatics, Beijing, China). RT-qPCR was performed with a 2X PCR master mix (AS-MR-006-5, Arraystar, Rockville, MD, USA) on a QuantStudio5 Real-time PCR System (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA, USA). The PCR program was set as follows: initial denaturation at 95 °C for 10 minutes, followed by 40 cycles of PCR (95 °C for 10 seconds, 60 °C for 60 seconds with fluorescence collection). The mRNA levels were normalized to the level of U6, and the relative expression of each mRNA was calculated using the 2-ΔΔCT method. The following primers were used: U6, F: 5′ GCTTCGGCAGCACATATACTAAAAT 3′ and R: 5′ CGCTTCACGAATTTGCGTGTCAT 3′; has-miR-494-5p, GSP: 5′ GGGAGGTTGTCCGTGTTGT 3′ and R: 5′ GTGCGTGTCGTGGAGTCG 3′.

All data were analyzed using R software (version 4.2.3, R Core Team, R Foundation for Statistical Computing, Vienna, Austria), IBM SPSS Statistics 25 (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, USA), and GraphPad Prism 8.2.1 (GraphPad Software, La Jolla, CA, USA). The criteria for type one error was set at

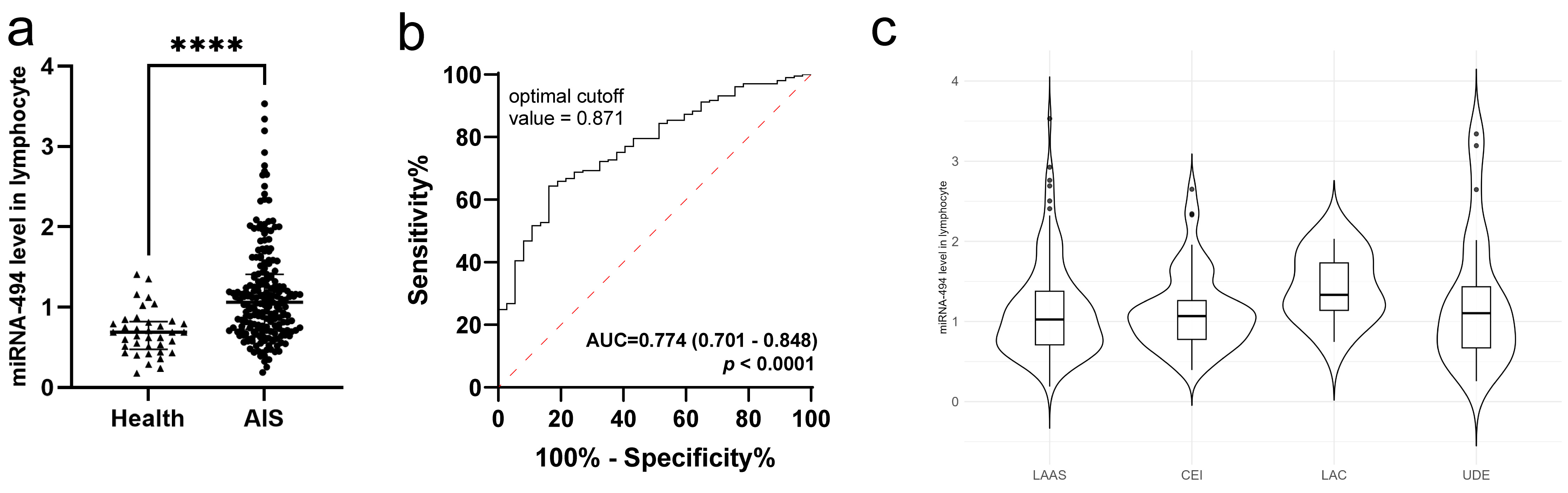

Initially, 205 patients with AIS and 37 healthy volunteers were analyzed for differences in miRNA-494 RNA levels in peripheral lymphocytes. The results indicated significantly higher expression in patients with AIS than in healthy individuals (Fig. 2a, p

Fig. 2.

Fig. 2. miRNA-494 level was elevated in patients with AIS. (a) Comparison between healthy volunteers and AIS patients, using Mann-Whitney U test (****, p

| Total (N = 205) | Excellent outcome (N = 109) | Poor outcome (N = 96) | p | ||

| Demographic characteristics | |||||

| Age (year, | 64.60 | 61.53 | 68.07 | ||

| Sex (%) | 54 (26.34%) | 27 (24.77%) | 27 (28.12%) | 0.700 | |

| Medical history | |||||

| Hypertension | 136 (66.34%) | 67 (61.47%) | 69 (71.88%) | 0.154 | |

| Diabetes mellitus | 68 (33.17%) | 32 (29.36%) | 36 (37.50%) | 0.277 | |

| Coronary heart disease | 43 (20.98%) | 16 (14.68%) | 27 (28.12%) | 0.029 | |

| Atrial fibrillation | 36 (17.56%) | 13 (11.93%) | 23 (23.96%) | 0.038 | |

| Hyperlipidemia | 60 (29.27%) | 38 (34.86%) | 22 (22.92%) | 0.085 | |

| Clinical and laboratory finding | |||||

| Onset-to-treatment time, h [IQR] | 2.90 [1.60–5.10] | 2.70 [1.40–4.30] | 3.25 [1.85–6.35] | 0.060 | |

| Systolic blood pressure, mmHg [IQR] | 150.00 [138.00–167.00] | 150.00 [137.00–167.00] | 150.00 [140.00–166.50] | 0.995 | |

| Diastolic blood pressure, mmHg [IQR] | 85.00 [77.00–91.00] | 85.00 [78.00–92.00] | 84.50 [75.00–90.00] | 0.312 | |

| White blood cell count, | 7.38 [6.00–8.84] | 7.22 [6.17–8.83] | 7.70 [5.99–8.84] | 0.668 | |

| Neutrophil count, | 5.06 [3.88–6.45] | 4.84 [3.85–5.92] | 5.54 [3.89–7.11] | 0.229 | |

| Lymphocyte count, | 1.53 [1.15–2.15] | 1.74 [1.24–2.20] | 1.42 [0.96–1.96] | 0.003 | |

| NLR [IQR] | 2.88 [2.10–5.50] | 2.63 [2.03–4.34] | 3.61 [2.14–6.93] | 0.011 | |

| Platelet count, | 207.00 [170.00–242.00] | 216.00 [182.00–257.00] | 196.00 [160.50–230.50] | 0.005 | |

| Triglyceride [IQR] | 1.48 [0.96–2.48] | 1.63 [1.00–2.70] | 1.40 [0.89–2.07] | 0.081 | |

| Total cholesterol [SD] | 4.53 [3.73–5.40] | 4.65 [3.88–5.54] | 4.43 [3.62–5.06] | 0.063 | |

| High density lipoprotein cholesterol [IQR] | 1.19 [1.01–1.40] | 1.17 [1.00–1.44] | 1.20 [1.02–1.37] | 0.910 | |

| Low density lipoprotein cholesterol [IQR] | 2.69 [2.03–3.41] | 2.79 [2.10–3.54] | 2.50 [1.99–3.30] | 0.145 | |

| Treatment and measurement | |||||

| NIHSS on admission [IQR] | 6.00 [3.00–11.00] | 3.00 [2.00–6.00] | 10.00 [6.00–14.00] | ||

| mRS on admission [IQR] | 3.00 [2.00–4.00] | 2.00 [1.00–3.00] | 4.00 [3.00–4.00] | ||

| Thrombolysis (%) | 90 (43.90%) | 53 (48.62%) | 37 (38.54%) | 0.190 | |

| Thrombectomy (%) | 32 (15.61%) | 10 (9.17%) | 22 (22.92%) | 0.012 | |

| Etiology | |||||

| Large artery atherosclerosis (LAAS) | 116 (56.59%) | 63 (57.80%) | 53 (55.21%) | 0.154 | |

| Cardioembolic infarct (CEI) | 54 (26.34%) | 33 (30.28%) | 21 (21.88%) | 0.154 | |

| Lacunar infarct (LAC) | 10 (4.88%) | 3 (2.75%) | 7 (7.29%) | 0.154 | |

| Stroke of undetermined etiology (UDE) | 25 (12.20%) | 10 (9.17%) | 15 (15.62%) | 0.154 | |

Excellent outcome: mRS score 0 to 1 at 3 months after AIS onset. Poor outcome: mRS score

After excluding patients with missing clinical indicators, we analyzed the baseline characteristics of the 205 patients, including demographics, past medical history, and various clinical indicators on admission, grouped by outcome (Table 1). The mean age of the patients was 64.60

Preliminary statistical analysis, including comparisons between the two outcome groups and correlation analysis, showed no significant correlation or association between miRNA-494 and the outcome at 3 months or with the mRS and NIHSS on admission. No trends were observed in the distribution plot of the miRNA-494 percentile divided by the interquartile range (Supplementary Fig. 1a–f). Additionally, miRNA-494 did not reach statistical significance in predicting the prognosis of all 205 patients using logistic regression (OR = 1.266, 95% CI: 0.794–2.018, p = 0.322).

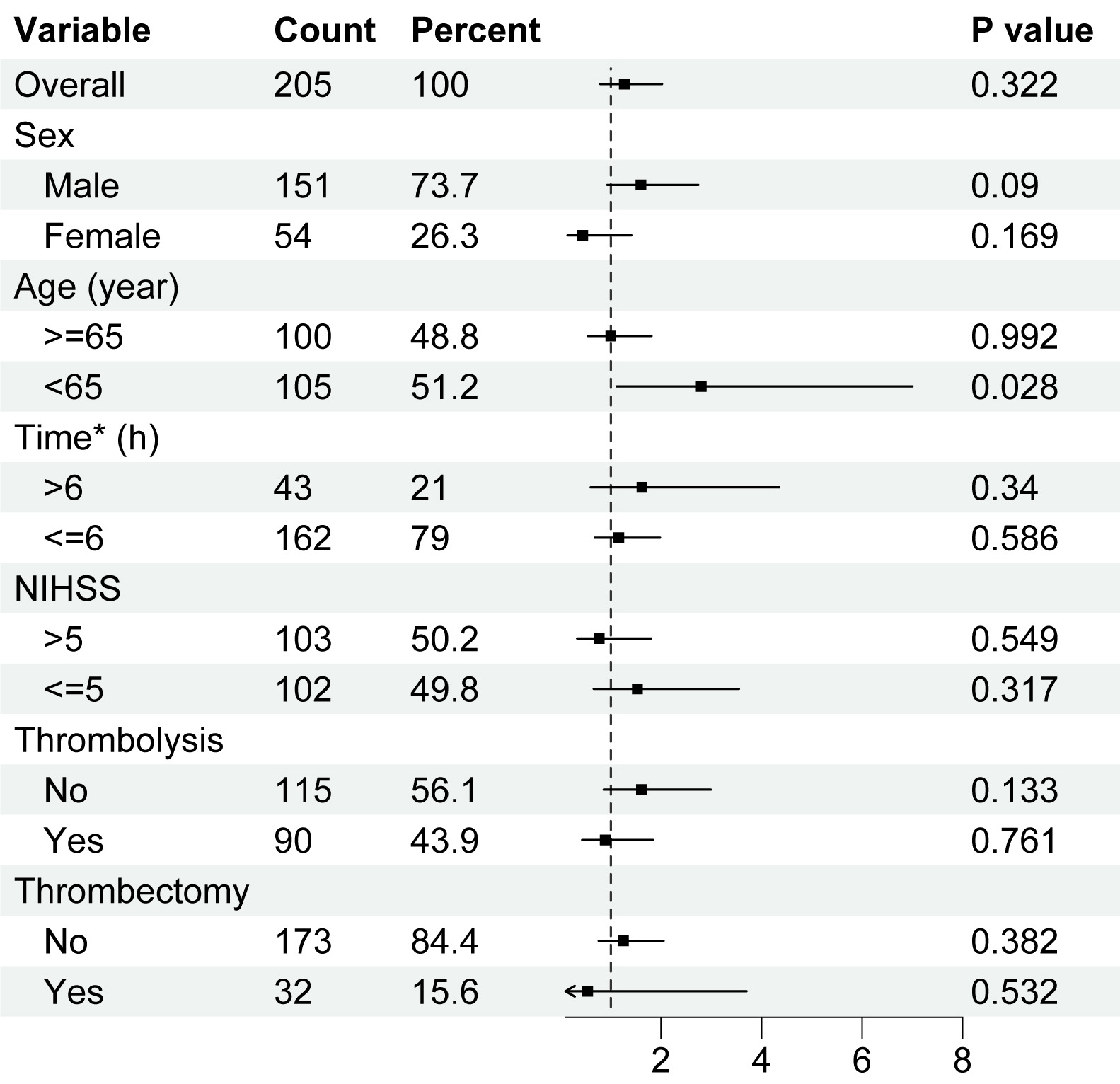

To further explore whether miRNA-494 levels in peripheral lymphocytes predict AIS prognosis, we analyzed various subgroups. Univariate logistic regression was employed to calculate the OR, 95% CI, and p-values of miRNA-494 levels in each subgroup, including sex, age (cutoff of 65 years), time to hospital admission (cutoff of 6 h), NIHSS score (cutoff of 5), and treatment acceptance, such as thrombolysis and mechanical thrombectomy. These cutoff values were based on baseline statistical data and clinical considerations. The results indicated that only the group aged under 65 years demonstrated a statistically significant prognostic ability of miRNA-494 levels in peripheral lymphocytes (Fig. 3, p = 0.028).

Fig. 3.

Fig. 3. Logistic regression analysis among subgroups of patients with acute ischemic stroke. Univariate logistic regression on miRNA-494 levels and excellent outcome at 3 months of AIS patients, in each subgroup. Higher miRNA-494 levels in peripheral lymphocytes predicted better outcome. Horizontal axis was the level of miRNA-494. Abbreviation: NIHSS, National Institutes of Health Stroke Scale. *Time means onset-to-treatment time of patients.

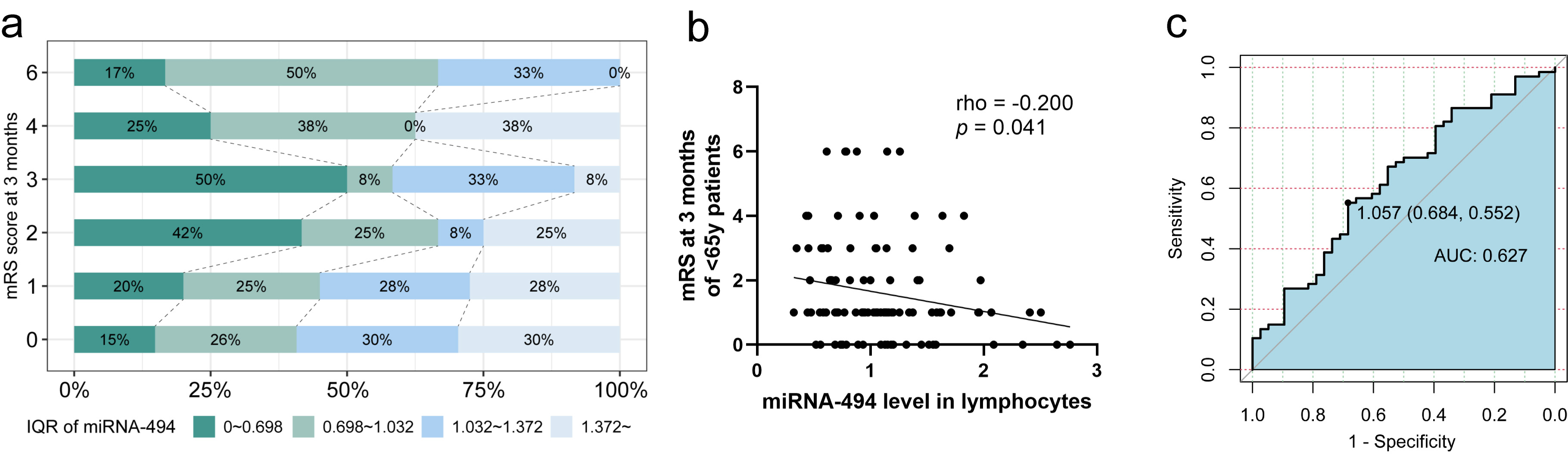

We focused on patients aged under 65 years (n = 105). The distribution of miRNA-494 in lymphocytes among the six groups according to the mRS score at 3 months is shown in Fig. 4a, revealing a clear trend where lower mRS scores were associated with higher levels of miRNA-494. Additionally, miRNA-494 expression in lymphocytes was significantly negatively correlated with the mRS score at 3 months (Fig. 4b). Univariate logistic regression analysis indicated that the OR for miRNA-494 levels predicting an excellent outcome for patients 3 months post-stroke was 2.800 (95% CI: 1.120–7.002, p = 0.028) (Table 2). The ROC curve analysis identified the optimal cutoff point for miRNA-494 at 1.057, which yielded a sensitivity of 68.4% and specificity of 55.2% for AIS (Fig. 4c, AUC = 0.627, 95% CI: 0.516–0.739). This level was then categorized as a dichotomous variable with a cutoff point of 1.057. We assessed the association of miRNA-494 levels with AIS outcomes using univariate logistic regression analysis, revealing that miRNA-494

Fig. 4.

Fig. 4. Analysis of prognosis of patients with AIS aged under 65. (a) Age

| Univariable model 1* | Multivariable model 2& | Multivariable model 3⊚ | |||||||

| OR (95% CI) | R2 | p value | OR (95% CI) | R2 | p value | OR (95% CI) | R2 | p value | |

| miRNA-494a | 2.800 (1.120–7.002) | 0.052 | 0.028† | 3.165 (1.222–8.199) | 0.134 | 0.018† | 2.565 (0.803–8.195) | 0.332 | 0.112 |

| miRNA-494 | 2.672 (1.158–6.168) | 0.051 | 0.021† | 2.788 (1.166–6.665) | 0.125 | 0.021† | 2.901 (1.031–8.159) | 0.341 | 0.044† |

*Model 1 was an unadjusted logistic regression model with the miRNA-494.

&Model 2 was an adjusted logistic regression model. The variables in model 2 included SBP, PLT and LDL on admission.

⊚Model 3 was an adjusted logistic regression model. The variables in model 3 included SBP, PLT, LDL, NIHSS score and mRS score on admission.

a miRNA-494 as a continuous variable.

b miRNA-494 as a categorical variable.

†p

Variance inflation factor of each valuable of different logistic models were all less than 10.

Abbreviation: OR, odds ratio; CI, confidence interval; SBP, Systolic blood pressure; PLT, Platelet count; LDL, Low density lipoprotein cholesterol.

Following univariate analysis, we combined miRNA-494 levels with other clinical indicators to determine whether the predictive power remained reliable when accounting for additional factors. LASSO regression was employed to screen potential variables from 24 candidates, selecting miRNA-494 levels in lymphocytes, NIHSS score, mRS score on admission, SBP, PLT, and LDL as covariates for sensitivity analysis. As a continuous variable, miRNA-494 alone was statistically significant in predicting AIS prognosis, and the inclusion of SBP, PLT, and LDL did not significantly influence the results (Table 2, OR = 3.165 [95% CI: 1.222–8.199], p = 0.018). However, when including the NIHSS score, the predictive effect of miRNA-494 was less stable (Table 2, OR = 2.565 [95% CI: 0.803–8.195], p = 0.112). Nevertheless, as a categorical variable, miRNA-494

We further analyzed whether miRNA-494 and miRNA-494

| miRNA-494a | miRNA-494 | ||||

| OR (95% CI) | p value | OR (95% CI) | p value | ||

| Overall (n = 105), 100% | 2.800 (1.184–7.521) | 0.028† | 2.672 (1.177–6.328) | 0.021† | |

| Intravenous thrombolysis | |||||

| Yes (n = 51), 48.6% | 1.044 (0.260–4.591) | 0.952 | 1.600 (0.467–6.019) | 0.464 | |

| No (n = 54), 51.4% | 6.458 (1.871–31.922) | 0.009† | 4.800 (1.551–16.234) | 0.008† | |

| Endovascular thrombectomy | |||||

| Yes (n = 13), 12.4% | 0.529 (0.023–8.619) | 0.656 | 2.500 (0.260–29.560) | 0.433 | |

| No (n = 92), 87.6% | 3.449 (1.303–10.987) | 0.022† | 2.833 (1.147–7.439) | 0.028† | |

| Recanalization therapy | |||||

| Either (n = 60), 57.1% | 1.093 (0.306–4.127) | 0.892 | 1.680 (0.564–5.302) | 0.359 | |

| Neither (n = 45), 42.9% | 8.938 (2.123–62.910) | 0.010† | 5.200 (1.480–20.773) | 0.013† | |

a miRNA-494 as a continuous variable.

b miRNA-494 as a categorical variable.

†p

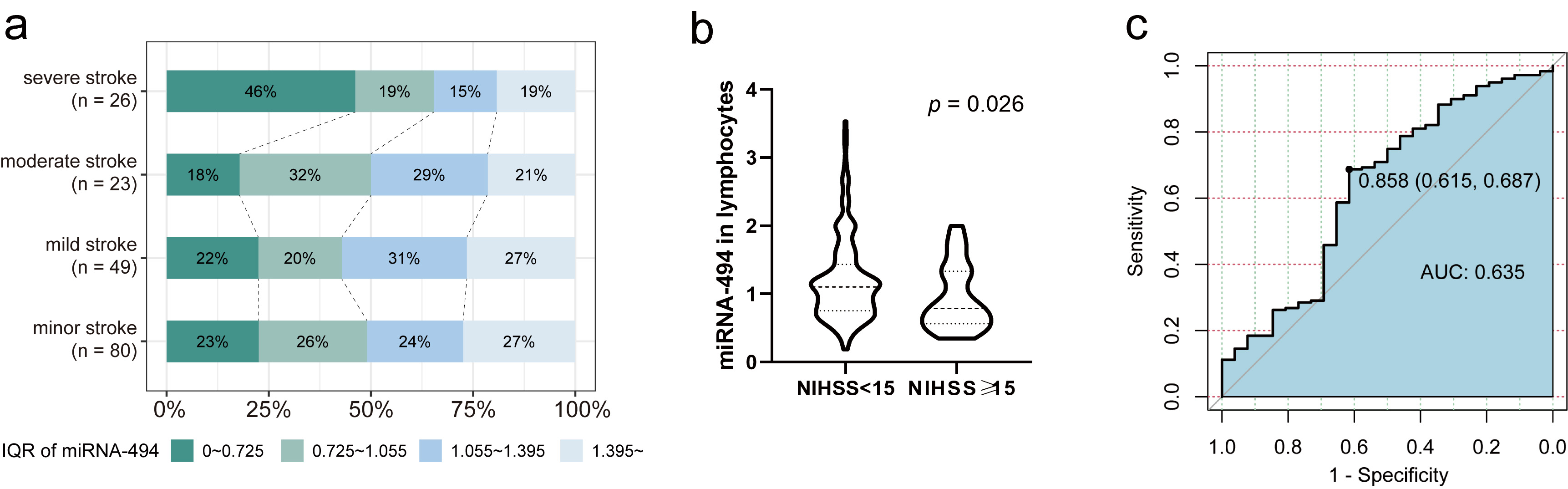

The relationship between miRNA-494 levels and admission NIHSS scores in 205 patients was analyzed using statistical methods and correlation analysis. In terms of severity, miRNA-494 levels showed a general downward trend in patients with more severe strokes (Fig. 5a). Based on the distribution of miRNA-494 levels and stroke severity, combined with clinical criteria and previous studies, the 205 patients with stroke were classified into minor-to-moderate and severe stroke groups, with an NIHSS score threshold of 15 [35, 36]. miRNA-494 levels in peripheral lymphocytes were significantly higher in patients with minor-to-moderate strokes compared with those with severe strokes (Fig. 5b, OR = 1.10 [95% CI: 0.74–1.42] vs. OR = 0.76 [95% CI: 0.53–1.29], p = 0.026). To establish a reliable association between miRNA levels and stroke severity, logistic regression and LASSO regression were applied to the 205 patients. miRNA-494 levels, coronary heart disease, atrial fibrillation history, PLT on admission, and NLR were identified as key variables. A multivariate logistic regression analysis using these variables showed that elevated miRNA-494 levels independently indicated minor-to-moderate stroke (Table 4, OR = 2.586 [95% CI: 1.024–6.533], p = 0.044).

Fig. 5.

Fig. 5. Analysis of stroke-severity of patients with AIS. (a) Division by interquartile range, under 4 classifications of severity according to NIHSS score on admission, the distribution of miRNA-494 levels percentiles of AIS patients (n = 205). (b) miRNA-494 level of two groups, cutoff by 15 score of NIHSS, Mann-Whitney U test, p = 0.026. (c) ROC curve of miRNA-494 levels to indicate NIHSS score on admission (n = 205). Abbreviation: ROC, receiver operating characteristic.

| Univariable model 1* | Multivariable model 2# | Multivariable model 3& | |||||||

| OR (95% CI) | R2 | p value | OR (95% CI) | R2 | p value | OR (95% CI) | R2 | p value | |

| miRNA-494 levels | 2.586 (1.024–6.533) | 0.024 | 0.044† | 2.407 (0.926–6.261) | 0.152 | 0.072 | 2.618 (0.955–7.177) | 0.196 | 0.061 |

| miRNA-494 | 3.514 (1.501–8.230) | 0.041 | 0.004† | 3.346 (1.297– 8.631) | 0.162 | 0.012† | 3.881 (1.403–10.738) | 0.207 | 0.009† |

*Model 1 was an unadjusted logistic regression model with the miRNA-494.

#Model 2 was an adjusted logistic regression model. The variables in model 2 included miRNA-494, NLR, PLT on admission.

&Model 3 was an adjusted logistic regression model. The variables in model 3 included miRNA-494, NLR, PLT on admission, history of coronary heart disease, atrial fibrillation, hyperlipidemia.

†p

R2 was calculated using Cos and Snell way.

Variance inflation factor of each valuable of different logistic models were all less than 10.

Abbreviations: AIS, acute ischemic stroke; PLT, platelet count.

We also calculated the predictive value of miRNA-494 levels for minor-to-moderate strokes using ROC curve analysis. When miRNA-494 was treated as a dichotomous variable with a cutoff of 0.858, it had a sensitivity of 68.7% and a specificity of 61.5% for predicting minor-to-moderate stroke (Fig. 5c, AUC = 0.635 [0.786–0.615]). The association between dichotomous miRNA-494 levels and stroke severity was further evaluated using multivariate logistic regression. The OR for miRNA-494 levels

Previous studies have shown that miRNA-494 mediates inflammation following stroke, suggesting that miRNA-494 may protect the nervous system by inhibiting Histone Deacetylase 3 (HDAC3) expression [18]. However, in neutrophils, antagonizing miRNA-494 reduced injury and neurotoxicity in experimental I/R models [19, 20]. In this study, miRNA-494 levels were higher in patients with AIS than in healthy individuals, consistent with previous findings [20]. Despite this, whether elevated miRNA-494 levels in lymphocytes are protective or a risk factor for AIS prognosis remains unclear. Insufficient statistical analysis has been conducted on the relationship between miRNA-494 and patient outcomes in AIS, whether in plasma, neutrophils, or lymphocytes. Therefore, we aimed to determine whether lymphocyte miRNA-494 could predict stroke prognosis.

Although miRNA-494 levels differed significantly between healthy volunteers and patients with AIS, they did not significantly predict excellent outcomes at 3 months among the 205 patients studied. One potential reason is that several confounding factors affecting miRNA-494 distribution were not controlled when enrolling patients. We did not exclude patients with immune system diseases, such as rheumatic heart disease, even though lymphocytes are closely tied to immune system functions. Another possible reason is that the time from symptom onset to hospital admission varies among patients, which leads to different time points for miRNA detection. The expression of certain miRNAs (such as miRNA-124, miRNA-210, miRNA-155, and miRNA-30a) has a nonlinear relationship with the duration of AIS illness [37]. However, whether miRNA-494 expression is time-dependent has not yet been studied. This variability may introduce bias into the statistical results. Therefore, we conducted subgroup analyses to determine whether other factors influenced miRNA-494’s predictive power.

Patients were classified as adults (age

We also investigated the impact of recanalization therapy on miRNA-494’s predictive value. No significant relationship was found between miRNA-494 and outcomes in patients who underwent reperfusion treatment. However, miRNA-494 was a promising predictor of prognosis in patients under 65 years who did not receive recanalization therapy. We hypothesize that miRNA-494 in lymphocytes has a protective role against ischemia. However, this effect becomes ambiguous after brain reperfusion. These findings offer hope for patients who cannot undergo recanalization therapy within the narrow treatment window. However, the underlying mechanisms require further investigation.

A correlation between miRNA-494 and stroke severity was observed. Among all patients, higher levels of miRNA-494 (or miRNA-494

The role of miRNA-494 in the nervous and immune systems remains contentious. Our analysis found no correlation between miRNA-494 levels in lymphocytes and lymphocyte or neutrophil counts (Supplementary Fig. 1g,h). In previous studies, miRNA-494 upregulation improved functional recovery, reduced injury, and inhibited apoptosis in rats after spinal cord injury (SCI) [41]. Similarly, in a hepatic I/R model, miRNA-494 reduced damage by inhibiting the Phosphatase and Tensin homologue/Phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase/Protein Kinase B (PTEN/PI3K/AKT) pathway [42]. Compared to healthy controls, miRNA-494 was upregulated in the peripheral blood of patients, likely as a protective response to acute-phase damage. Based on these studies, it is speculated that insufficient miRNA-494 upregulation in lymphocytes after I/R may result in weak protection. In neutrophils, miRNA-494 may act as a regulatory molecule that induces inflammation. Combined with the results of this study, low miRNA-494 expression in lymphocytes may lead to more severe stroke. Further research using experimental models is needed to elucidate the specific pathways involved in the protective mechanism of miRNA-494 in brain lymphocytes after I/R.

This study had certain limitations, including its single-center design, which restricts generalizability, and potential selection bias. The sample size of healthy controls is also relatively small (n = 37), which may affect one of the results, the higher expression of miRNA in the patient group compared to healthy individuals. Detailed clinical baseline information for these healthy volunteers was lacking, therefore, we could not further analyze between the two groups. Several risk factors associated with stroke, such as body mass index, alcohol or smoking habits, blood glucose levels, and stroke history, were not considered due to missing data. Additionally, the second part of the study focused on minor-to-moderate and severe strokes; however, only 26 patients (12.68%) had severe strokes. Future replication studies are necessary to further investigate the effects of miRNA-494 on AIS [43].

In summary, miRNA-494 levels in peripheral lymphocyte are significantly elevate in patients with AIS compared with healthy volunteers, suggesting its potential as a novel therapeutic strategy. A miRNA-494 level greater than 1.057 in peripheral blood lymphocytes may help predict an excellent outcome in patients with AIS aged under 65 years, particularly those who do not receive intravenous thrombolysis or endovascular thrombectomy. Additionally, a high level of miRNA-494 or a level greater than 0.858 may indicate minor-to-moderate stroke at admission.

All data used for this study are provided in the manuscript. Additional details are available from the corresponding author on request.

ZH and YL designed the research study. ZX and TS performed the research. LZ, JF, RW, FY, HZ, and QM provided help and advice on data curation and RT-qPCR experiments. ZX analyzed the data. All authors contributed to editorial changes in the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript. All authors have participated sufficiently in the work and agreed to be accountable for all aspects of the work.

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki, and approved by the Institutional Review Board (or Ethics Committee) of Xuanwu Hospital, Capital Medical University (No.[2021]079). Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study. Written informed consent has been obtained from the patients to publish this paper.

We thank all patients and their families for participating in this study.

This research was funded by grants from the National Natural Science Foundation of China (82171301 and 82171298) and Beijing Municipal Health Commission (11000025T000003320673).

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Supplementary material associated with this article can be found, in the online version, at https://doi.org/10.31083/RN37809.

References

Publisher’s Note: IMR Press stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.