1 Cardiology Department, Hospital Clínico San Carlos, IdISSC, 28040 Madrid, Spain

2 Cardiology Department, Hospital Universitario Virgen de Macarena, 41009 Sevilla, Spain

3 Cardiology Department, Hospital Regional Universitario de Málaga, 29010 Málaga, Spain

4 Cardiology Department, Hospital Universitario Son Espases, 07120 Palma de Mallorca, Spain

5 Cardiology Department, Hospital Universitario Joan XXIII, 43005 Tarragona, Spain

6 Cardiology Department, Hospital General Universitario Gregorio Marañón, 28007 Madrid, Spain

7 Cardiology Department, Hospital Universitario La Princesa, 28006 Madrid, Spain

8 Cardiology Department, Hospital Universitario de Torrejón, 28850 Madrid, Spain

9 Cardiology Department, Hospital Clínico Universitario de Salamanca, 37007 Salamanca, Spain

10 Cardiology Department, Hospital Universitario Vall d´Hebron, 08035 Barcelona, Spain

11 Cardiology Department, Hospital General Universitario de Albacete, 02006 Albacete, Spain

12 Cardiology Department, Hospital Universitario Arnau de Vilanova, 25198 Lérida, Spain

13 Cardiology Department, Hospital Universitario Puerta de Hierro, 28222 Madrid, Spain

14 Research Methodological Support Unit and Preventive Department, Hospital Clínico San Carlos, IdISSC, 28040 Madrid, Spain

15 Cardiology Department, Hospital Clínico Universitario de Valladolid, 47003 Valladolid, Spain

†These authors contributed equally.

Abstract

There is evidence that pacemaker implantation can trigger Takotsubo syndrome (TTS). However, limited information is available on the prognosis of TTS caused by this trigger, so our study aims to elucidate the clinical features, presentation, and prognostic factors associated with this syndrome in this specific situation.

We analyzed a group of patients with TTS triggered by pacemaker implantation (n = 41), including consecutive cases from the multicenter registry on takotsubo syndrome (RETAKO) and patients identified through a systematic literature search, and compared them to the general RETAKO cohort (n = 1559). We performed a 1:3 propensity score matching (PSM) based on dyslipidemia, diabetes mellitus, smoker/ex-smoker status, syncope, angina, vagal symptoms, and physical/mixed trigger, generating two balanced groups.

Compared to other triggers, TTS associated with pacemaker implantation was linked to a longer corrected QT interval (551.2 ms vs. 502.5 ms, p = 0.005), lower left ventricular ejection fraction (34.8% vs. 47.3%, p < 0.001), a higher proportion of acute kidney injury (29.3% vs. 11.0%, p = 0.001), and an increased rate of cardiogenic shock (20.6% vs. 8.8%, p = 0.029). However, there were no differences in all-cause mortality (12.2% vs. 13.1%, p = 0.858) or TTS recurrence (0.0% vs. 3.9%, p = 0.639). After PSM, the previously observed differences were no longer present, with no significant differences in death or recurrences.

TTS following pacemaker implantation predominantly presents with greater rates of cardiogenic shock and acute kidney injury, without differences in all-cause mortality or TTS recurrence. After PSM, no differences were found regarding cardiovascular outcomes, suggesting that the physical nature of the trigger could account for the initial differences observed.

Keywords

- takotsubo syndrome

- pacemaker implantation

- prognosis

- registry

Takotsubo syndrome (TTS), first described in Japan in the early 1990s [1], consists of a transient dysfunction of the left ventricle, more common in postmenopausal women.

Secondary forms of TTS (i.e., those associated with a physical or mixed trigger) have been described to have a worse prognosis than primary forms (i.e., those idiopathic or associated with a psychological stress) [2, 3]. Pacemaker implantation constitutes a physical stress situation for the patient. If the reason for pacemaker implantation is an acute advanced atrioventricular block, this process can be an even greater stressor, as it triggers low cardiac output [4].

The first case report of TTS after pacemaker implantation was published in 2006 [5]. Niewinski et al. [6] published a series of nine cases of TTS after pacemaker implantation in 2020. Two years later, Strangio et al. [7] conducted a systematic review of 28 published cases, with limited clinical information.

Our objective was to elucidate the clinical characteristics and cardiovascular outcomes of patients affected by TTS in the context of pacemaker implantation, using published cases from the literature and from the multicenter registry on takotsubo syndrome (RETAKO) to generate a cohort larger than those previously studied; and to compare them with the general RETAKO cohort, as well as with patients with physical or mixed trigger, using propensity score matching (PSM).

We conducted this study in accordance with the Helsinki Declaration and approval was granted by the Ethics Committee of the coordinating center. All patients provided signed informed consent.

We utilized the national multicenter registry of TTS: RETAKO, supported by the Ischemic Heart Disease and Acute Cardiovascular Care Section of the Spanish Society of Cardiology, initiated on January 1st, 2012. It is an ambispective multicenter registry developed in 36 centers: retrospective (from 2002 to 2012) and prospective (from 2012 to the present). Its rationale and design have been previously described [8].

The inclusion criteria for this registry are the revised Mayo Clinic criteria which include study of coronary anatomy to rule out obstructive coronary disease or acute plaque rupture. These criteria also include regional wall motion abnormalities that do not correspond to a specific coronary territory with transient changes on the electrocardiogram or modest elevation of troponin. Once patients were selected, their data were collected, anonymized, and transferred to a central database.

Patient follow-up after discharge could be conducted either remotely or in-person, with both patients and their families. The outcomes were pre-specified and were adjudicated by two experienced local investigators (I.N., O.V.). The same two experienced researchers carefully evaluated each case to assess the temporal relationship between pacemaker implantation and the development of TTS. Our predefined primary outcomes were all-cause mortality and the recurrence of TTS. As secondary outcomes, we established: the degree of left ventricular dysfunction (using the left ventricular ejection fraction (LVEF)), the length of the corrected QT interval (cQT), cardiogenic shock, in-hospital readmissions, acute kidney injury and intraventricular thrombus formation.

Thus, 21 patients from the RETAKO registry who suffered from TTS during the placement of a pacemaker; either immediately after or in the following 72 hours (as described in the literature [5, 9]), were included in the TTS group within the context of pacemaker implantation. The remaining 1559 patients were included in the group of TTS due to any other causes and served as a reference group.

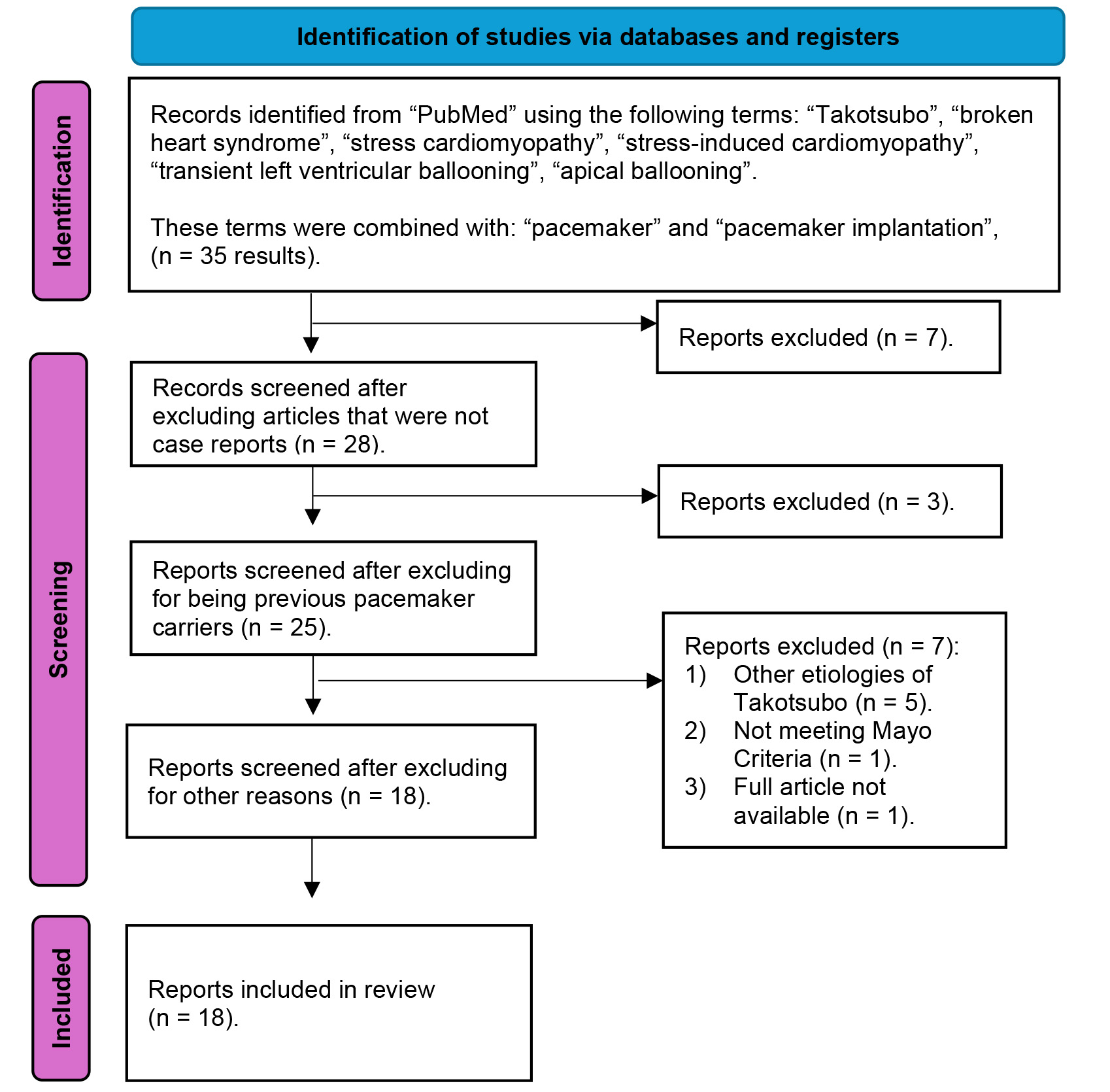

For our study, we conducted a systematic review in March 2024 of TTS in the context of pacemaker implantation using the PubMed database, including the following terms: “Takotsubo”, “broken heart syndrome”, “stress cardiomyopathy”, “stress-induced cardiomyopathy”, “transient left ventricular ballooning” and “apical ballooning”. We combined these terms with: “pacemaker” and “pacemaker implantation”. We only included patients over 18 years old who met the revised Mayo Clinic criteria for the diagnosis of TTS.

Fig. 1 summarizes the selection process and a detailed PRISMA flow diagram of the review. Finally, we selected 18 articles that met the established inclusion criteria, encompassing a total of 20 patients [5, 9, 10, 11, 12, 13, 14, 15, 16, 17, 18, 19, 20, 21, 22, 23, 24, 25].

Fig. 1.

Fig. 1. PRISMA flowchart of the systematic review of the literature. This figure shows the systematic literature review conducted in March 2024 in the PubMed database. A series of terms related to takotsubo syndrome (TTS) were combined with other terms related to pacemaker. Of the 35 results obtained, 17 were excluded. Finally, a total of 18 articles, including 20 patients, were selected for our study.

Clinical information of the case reports from the patients used for this systematic review can be found in the Supplementary Table 1.

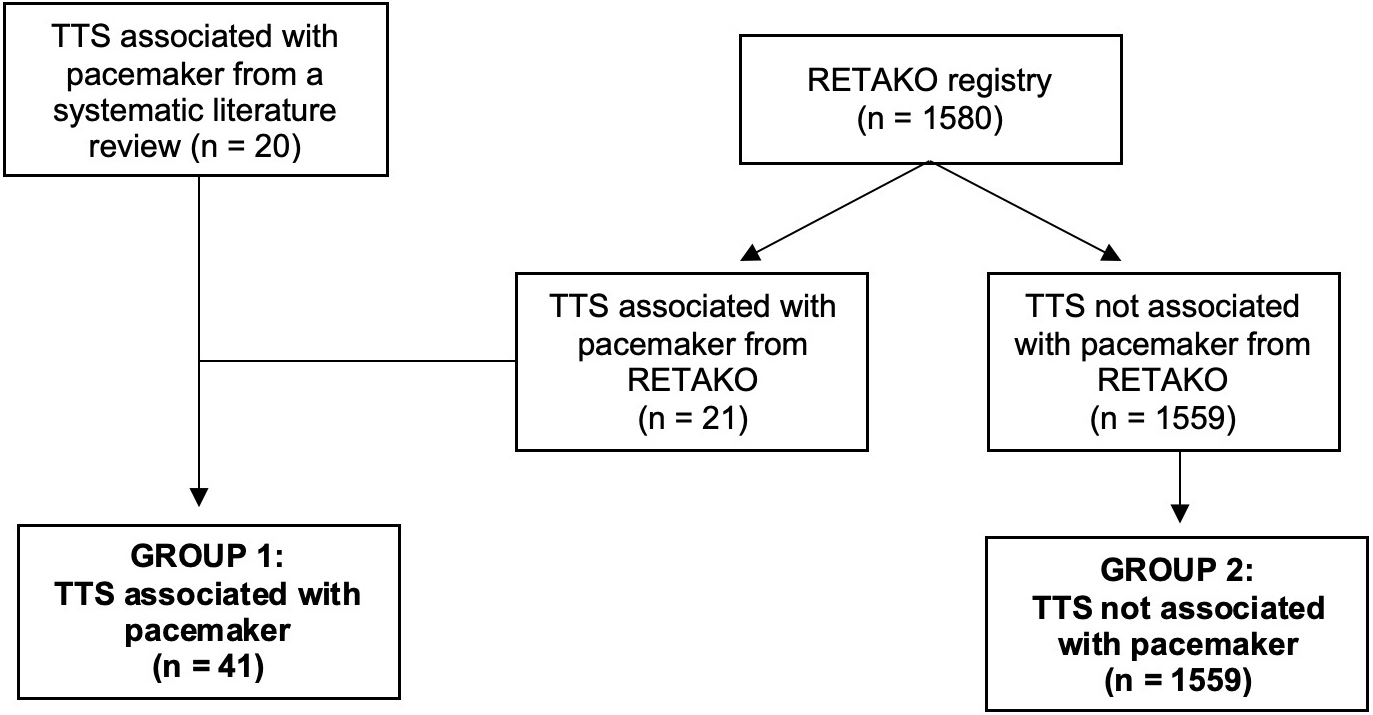

Two groups were produced: (1) a group of 41 patients with TTS in the context of pacemaker implantation, consisting of 21 patients from the RETAKO registry and 20 patients from our systematic review; (2) a second group comprised of 1559 patients with TTS due to other triggers, all extracted from the RETAKO registry as described in Fig. 2.

Fig. 2.

Fig. 2. Flowchart of the formation of the study groups. The first group of 41 patients with Takotsubo syndrome (TTS) associated with pacemaker implantation was formed, including 20 patients identified through the systematic literature review and 21 from the national multicenter registry on takotsubo syndrome (RETAKO). The second group consisted of 1559 patients from RETAKO who presented with TTS due to a different cause.

Continuous variables were expressed as either mean

Statistical analysis and graphing were carried out using the Office 365 package (Microsoft, Redmond, WA, USA), SPSS software v.26 (IBM, Chicago, IL, USA) and R statistical software v. 4.3.1 (R Foundation for Statistical Computing, Vienna, Austria).

Additionally, we performed a 1:3 PSM using the previously mentioned groups based on the following variables: dyslipidemia, diabetes mellitus, smoker/ex-smoker status, syncope, angina, vagal symptoms, and physical or mixed trigger.

The adjusted incidence of clinical events during follow-up was assessed using the Kaplan-Meier method after PSM (calculated from hospital discharge to the last follow-up or death), with group comparisons made via the log-rank test.

Moreover, we conducted a sensitivity analysis between patients with TTS following pacemaker implantation from the RETAKO registry and those obtained from the literature (Supplementary Table 2), to assess for relevant differences between the two groups that could bias the data pooling.

As including the variables “syncope” and “angina” in the initial PSM model could have introduced confounding, we constructed a revised PSM that omits these two covariates while preserving all other baseline factors. The results of this analysis are presented in Supplementary Table 3. We also presented an analysis of the pacemaker indication, the type of pacemaker, and the timing of implantation in Supplementary Table 4.

The baseline clinical characteristics and comorbidities are detailed in Table 1. The overall percentage of TTS in the context of pacemaker implantation within the RETAKO cohort was 1.3%. There were no differences in terms of age between patients with TTS associated with having pacemaker or not. Among patients with TTS, the proportion of females did not differ significantly between the two groups (78.0% vs. 86.7%, p = 0.112). Moreover, the burden of comorbidities was quite similar in both groups, although there was a higher percentage of patients with diabetes mellitus in the group associated with pacemaker implantation. No significant differences in cancer prevalence were observed between the groups.

| TTS due to pacemaker implantation (n = 41) | TTS not due to pacemaker implantation (n = 1559) | p | ||

| Age (years) | 73.63 | 70.52 | 0.200 | |

| Female | 32/41 (78.0) | 1345/1552 (86.7) | 0.112 | |

| Comorbidities | Hypertension | 25/34 (73.5) | 1002/1491 (67.2) | 0.437 |

| Dyslipidemia | 11/35 (31.4) | 694/1467 (47.3) | 0.063 | |

| Diabetes Mellitus | 13/36 (36.1) | 301/1474 (20.4) | 0.022 | |

| Smoker/Ex-smoker | 8/35 (22.9) | 399/1485 (26.9) | 0.596 | |

| Ischemic Heart Disease1 | 3/25 (12.0) | 94/1412 (6.7) | 0.236* | |

| Hepatopathy | 1/22 (4.5) | 56/1468 (3.8) | 0.579* | |

| Cancer | 2/41 (4.8) | 99/1559 (6.4) | 0.570* | |

| TTS clinical presentation | Syncope | 12/41 (29.3) | 115/1466 (7.8) | |

| Angina | 12/41 (29.3) | 936/1444 (64.8) | ||

| Vagal symptoms | 12/40 (30.0) | 641/1472 (43.5) | 0.088 | |

| Dyspnea | 19/34 (55.9) | 460/1110 (41.4) | 0.093 | |

| Palpitations | 3/40 (7.5) | 111/1462 (7.6) | 1.000* | |

| Physical/mixed trigger | 41/41 (100.0) | 530/1159 (34.0) | ||

| Apical akinesia2 | 34/41 (82.9) | 1161/1558 (74.5) | 0.221 | |

| Cardiovascular outcomes | LVEF (%)3 | 34.8 | 47.3 | |

| cQT interval (ms)4 | 551.2 | 502.5 | 0.004 | |

| Acute kidney injury | 12/41 (29.3) | 159/1447 (11.0) | 0.001 | |

| Pulmonary edema | 7/41 (17.1) | 135/1454 (9.3) | 0.102 | |

| Cardiogenic shock | 7/34 (20.6) | 97/1104 (8.8) | 0.029 | |

| Intraventricular thrombus | 2/41 (4.9) | 41/1457 (2.8) | 0.331* | |

| Readmission | 1/35 (2.9) | 137/1245 (11.0) | 0.167* | |

| Follow-up (months)5 | 4.0 (1.3–19.0) | 19.0 (5.0–52.0) | ||

| TTS recurrence | 0/35 (0.0) | 48/1245 (3.9) | 0.639* | |

| In-hospital death | 1/41 (2.4) | 31/1559 (2.0) | 0.568* | |

| All-cause mortality | 5/41 (12.2) | 205/1559 (13.1) | 0.858 |

Categorical variables are reported as n/N (percentage). Continuous variables are presented as mean

1Regardless of its severity.

2Patients were classified based on whether it presented in the typical form of TTS (apical akinesia) or an atypical form (basal or mid-segment akinesia).

3Left ventricular ejection fraction (LVEF) is expressed as a percentage according to the biplane Simpson method by echocardiography.

4The corrected QT interval (cQT) is expressed in milliseconds using Bazett’s correction formula.

5Follow-up is expressed in months as median and interquartile range.

Regarding clinical presentation on hospital admission, syncope was more frequent in the group associated with pacemaker implantation (29.3% vs. 7.8%; p

In both groups, there was a higher representation of the typical TTS pattern (apical akinesia with basal hypercontractility), with no significant differences (82.9% vs. 74.5%, p = 0.221). The representation of secondary forms of TTS (with a physical/mixed trigger) was 34.0% in the group not associated with pacemaker implantation.

Regarding the cardiovascular outcomes in the two groups: in the TTS associated with pacemaker implantation group, the LVEF was severely depressed (34.8%) and significantly lower (p

In the TTS associated with pacemaker group, a higher percentage of cardiogenic shock was observed, at up to 20.6% compared to 8.8%; this difference was statistically significant (p = 0.029). There was also a significantly higher proportion of acute kidney injury in nearly one third of the patients with pacemaker implantation.

Concerning patient follow-up, it was significantly longer in the non-pacemaker-associated group (group two) (4.0 vs. 19.0 months, p

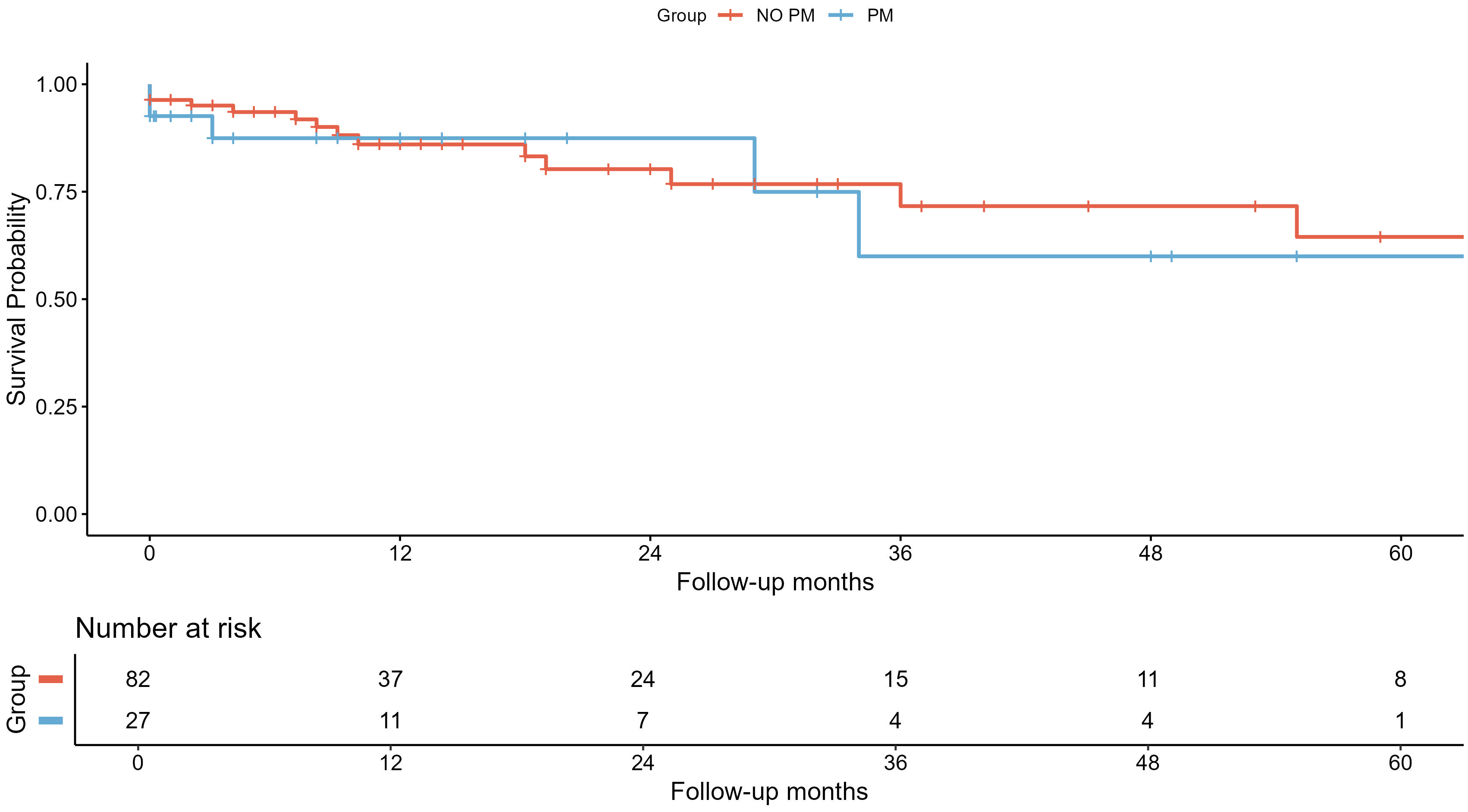

Table 2 shows the comparison after 1:3 PSM, in which the differences in various cardiovascular outcomes (i.e., acute kidney injury, cardiogenic shock, LVEF and cQT interval) are lost after matching. With respect to mortality rates and TTS recurrence, no differences were observed between the two cohorts either before or after PSM. The Kaplan–Meier survival curves of all-cause mortality are presented in Fig. 3 (log-rank test: p = 0.670) using the PSM population.

| TTS due to pacemaker implantation (n = 33) | TTS not due to pacemaker implantation (n = 99) | p | ||

| Age (years) | 73.18 | 70.53 | 0.985 | |

| Female | 25/33 (75.8) | 78/99 (78.8) | 0.716 | |

| Comorbidities | Hypertension | 22/31 (71.0) | 58/99 (58.6) | 0.216 |

| Dyslipidemia | 10/33 (30.3) | 23/99 (32.3) | 0.829 | |

| Diabetes Mellitus | 11/33 (33.3) | 24/99 (24.2) | 0.306 | |

| Smoker/Ex-smoker | 8/33 (24.2) | 24/99 (24.2) | 1.000 | |

| Ischemic Heart Disease1 | 2/23 (8.7) | 0/92 (0.0) | 0.039* | |

| Hepatopathy | 1/21 (4.8) | 16/97 (16.5) | 0.302* | |

| Cancer | 2/18 (11.1) | 16/99 (16.2) | 0.740* | |

| TTS clinical presentation | Syncope | 12/33 (36.4) | 36/99 (36.4) | 1.000 |

| Angina | 10/33 (30.3) | 24/99 (24.2) | 0.491 | |

| Vagal symptoms | 10/33 (30.3) | 27/99 (27.3) | 0.737 | |

| Dyspnea | 15/26 (57.7) | 20/67 (29.9) | 0.013 | |

| Palpitations | 3/32 (9.4) | 8/98 (8.2) | 1.000* | |

| Physical/mixed trigger | 33/33 (100.0) | 99/99 (100.0) | - | |

| Apical akinesia2 | 26/33 (78.8) | 79/99 (79.8) | 0.901 | |

| Cardiovascular outcomes | LVEF (%)3 | 36.9 | 41.2 | 0.144 |

| cQT interval (ms)4 | 549.0 | 521.6 | 0.188 | |

| Acute kidney injury | 11/33 (33.3) | 29/98 (20.4) | 0.131 | |

| Pulmonary edema | 5/33 (15.2) | 6/99 (6.1) | 0.141 | |

| Cardiogenic shock | 7/26 (26.9) | 16/67 (23.9) | 0.760 | |

| Intraventricular thrombus | 1/33 (3.0) | 5/99 (5.1) | 1.000* | |

| Readmission | 1/27 (3.7) | 3/76 (3.9) | 1.000* | |

| Follow-up (months)5 | 4.00 (1.0–29.0) | 9.50 (4.0–25.5) | 0.154 | |

| TTS recurrence | 0/27 (0.0) | 2/77 (2.6) | 1.000* | |

| In-hospital death | 1/33 (3.0) | 3/99 (3.0) | 1.000* | |

| All-cause mortality | 5/33 (15.2) | 14/99 (14.1) | 1.000 |

Categorical variables are reported as n/N (percentage). Continuous variables are presented as mean

1Regardless of its severity.

2Patients were classified based on whether it presented in the typical form of TTS (apical akinesia) or an atypical form (basal or mid-segment akinesia).

3Left ventricular ejection fraction (LVEF) is expressed as a percentage according to the biplane Simpson method by echocardiography.

4The corrected QT interval (cQT) is expressed in milliseconds using Bazett’s correction formula.

5Follow-up is expressed in months as median and interquartile range.

Fig. 3.

Fig. 3. Survival analysis of all-cause mortality using Kaplan–Meier curves. Survival analysis of all-cause mortality after 1:3 propensity score matching represented by Kaplan–Meier curves and number of patients at risk after the end of each time period. In blue, the takotsubo syndrome (TTS) group associated with pacemaker implantation (PM) and, in red, the group not associated with pacemakers (NO PM).

Supplementary Table 2 shows the sensitivity analysis between patients with TTS following pacemaker implantation from the RETAKO registry and those obtained from the literature, which showed that patients from both subgroups were comparable in terms of their baseline characteristics and outcomes (i.e., cardiogenic shock and mortality) although a lower left LVEF was observed in the literature-derived pacemaker-associated TTS group. Therefore, we could assume that this comparison is acceptable as a whole and does not constitute a limiting bias.

With the revised PSM model (excluding angina and syncope as covariates), no statistically significant differences emerged between groups for the principal outcomes—pulmonary edema, cardiogenic shock, readmission, TTS recurrence, in-hospital mortality and all-cause mortality. However, differences persisted in secondary parameters, namely LVEF, cQT, and acute kidney injury.

Our study included what is, to date, the largest cohort of TTS in the context of pacemaker implantation, comprising patients from a systematic review of the literature and the multicenter registry RETAKO, and compared it with a cohort of patients with TTS due to other causes, extracted from the RETAKO registry.

Our main findings were: (1) TTS in the setting of pacemaker implantation presents with a higher rate of cardiogenic shock, but not greater mortality, prior to PSM; (2) the greater rates of cardiogenic shock and acute kidney injury are lost when adjusting for physical/mixed trigger and baseline characteristics; (3) syncope is more common as an initial symptom in patients with TTS in the setting of pacemaker implantation, whereas angina is less frequent; and (4) there are no significant differences regarding sex in patients with TTS in the setting of pacemaker implantation compared to the general RETAKO cohort.

No differences were found regarding sex between TTS in the setting of pacemaker implantation compared to the general RETAKO cohort, but a trend was observed toward a higher proportion of males in the pacemaker group, which is in line with the literature [26, 27, 28]. Previous studies indicate that physical triggers, compared to psychological, are more common in male individuals, with a greater incidence of cardiogenic shock and mortality. No differences were found in mortality in our study (neither before nor after the PSM), which might be due to the limited power, owing to the uncommon nature of this particular trigger, further studies are needed to elucidate this matter.

One of the most widely accepted mechanisms in the pathophysiology of TTS is sympathetic nervous system activation with subsequent catecholamine release [29, 30]. Experimental work in animal models has demonstrated an apicaltobasal gradient in catecholamine responsiveness that reflects regional differences in adrenoceptor subtype expression [31].

Whether this sympathetic surge is triggered primarily by the pacemaker implantation itself—through procedural pain or procedurerelated anxiety—or by the advanced conduction disturbance—via low cardiac output and attendant hemodynamic stress—remains a matter of debate [17]. Reports of TTS following urgent pacemaker placement for complete atrioventricular block support the latter hypothesis [10, 14]. Conversely, occurrences of TTS following elective pacemaker placement for sicksinus syndrome in hemodynamically stable patients [15, 22], where circulating catecholamine levels are presumably low, suggest that the implantation alone may suffice as a trigger.

In fact, cases of TTS have been reported in the context of other types of percutaneous cardiac procedures, such as atrial fibrillation ablations [32] or percutaneous mitral repair with edge-to-edge therapy [33]. These interventions, associated with peri-procedural pain but not with conduction disturbances, support our hypothesis.

A further pathophysiological hypothesis is that ventricular pacing itself may be poorly tolerated and thus may trigger TTS. However, the prompt recovery of ventricular function and the low recurrence rate observed in our series—despite continued ventricular stimulation—make this explanation less likely.

Patients with non-pacemaker-associated TTS more frequently presented with angina associated with vagal symptoms, while the pacemaker-associated TTS patients were notable for a higher frequency of syncope. Núñez-Gil et al. [2] described primary forms of TTS presented more frequently with chest pain and vagal symptoms, but secondary TTS had a higher frequency of syncope as a clinical presentation. We believe that the initial presentation is most likely explained by the pacemaker indication (i.e., bradyarrhythmia requiring permanent pacing).

Although both groups exhibited prolonged corrected QT intervals, the duration was significantly greater in the group associated with pacemaker implantation. This finding may be attributable to the cardiac memory phenomenon as well as cQT prolongation secondary to pacing. Ventricular activation induced by pacing leads to slower depolarization and, consequently, a wider QRS complex compared to conduction through the native His-Purkinje system. These prolonged ventricular complexes are linked to abnormal repolarization, resulting in cQT interval prolongation. In several studies involving patients with cardiomyopathies, such prolongation of ventricular depolarization and repolarization has been associated with an increased risk of ventricular arrhythmias. Although TTS is not considered a true cardiomyopathy due to its reversible nature, this feature could nonetheless contribute to adverse cardiovascular outcomes in larger patient cohorts [34]. Moreover, previous studies have described an association between the risk of ventricular arrhythmias in TTS and both cQT duration [35] and Tpeak–Tend interval prolongation [36].

Rhythm disorders have been linked to decreased long-term survival in TTS [37], with cardiogenic shock being an independent predictor (either for tachyarrhythmias or bradyarrhythmias). This study aligns with our findings, as the association between a higher proportion of cardiogenic shock and TTS after pacemaker implantation (indicated mostly by bradyarrhythmias as shown in Supplementary Table 3) is reproduced.

Nevertheless, the short follow-up and the low rate of ventricular arrhythmias reported in the literature group preclude any conclusions to be made about the arrhythmic burden. Moreover, most of the electrocardiographic tracings are post-pacemaker implantation, and the Tpeak-Tend has not been validated in this situation. Although the electrocardiogram shows ventricular pacing with secondary repolarization alterations, this does not prevent the observation of electrocardiographic changes caused by TTS and their progression over time [38].

In the TTS group following pacemaker implantation, a significantly lower LVEF was observed, although this did not translate into a worse prognosis. We believe that, in part, the ventricular dysfunction could be explained by advanced conduction disorders, whereas another part might be attributed to contractility alterations inherent to TTS. It is likely that the ventricular dysfunction resolved quickly because the trigger was short-lived (limited to the implantation time), and the conduction disorders were resolved with pacemaker placement. This could explain the lower mortality, as it has been reported [39] that a rapid recovery of LVEF (within less than ten days) is associated with a better prognosis compared to delayed recovery. However, due to the limited follow-up in the patient cohort described in the literature, we cannot confirm this hypothesis.

In the study group, a higher percentage of cardiogenic shock was observed during the hospital stay; a phenomenon that can be observed in other particular TTS settings, such as the peripartum period [3] and the pediatric population [27], in which physical triggers are more common [26]. However, before and after adjusting for potential confounders, the mortality rate remained similar between groups. This increase in cardiogenic shock was most likely driven by the greater percentage of apical akinesia pattern and the greater LVEF dysfunction that was corrected after PSM. As in the peripartum period [3], in which the population is much younger, the detection of the TTS in a controlled in-hospital environment might have played a role in early diagnosis and prompt vasoactive therapy as well as intensive surveillance, which might have accounted for a similar mortality rate than that of the general RETAKO population, in an otherwise greater mortality setting of a physical trigger in an elderly population.

The lack of clinical data to grade cardiogenic shock according to the Society for Cardiovascular Angiography and Interventions (SCAI) scale in our series also may have influenced our inability to find differences in mortality between groups. As described by Camblor-Blasco et al. [40], there is an association between a higher SCAI grade in the context of TTS with higher in-hospital and one-year mortality. However, these authors report that mortality in the early stages of cardiogenic shock is low: 2.3% in SCAI A and 4.9% in SCAI B. It is possible that many of the patients in our series with cardiogenic shock had a low SCAI grade and, therefore, not a high mortality rate. Moreover, other variables that could negatively influence outcomes in cardiogenic shock in the setting of TTS, such as thyroid hormone homeostasis [41] could not be calculated due to the lack of available data.

Furthermore, in the study group, a higher rate of acute kidney injury was observed. Renal impairment in TTS has been associated with lower LVEF, higher rates of bleeding, a higher percentage of cardiogenic shock, as well as higher rates of all-cause mortality and major cardiovascular events at 5 years [42]. However, after PSM, acute kidney injury was equally common between groups, suggesting that the physical trigger was most likely driving these differences.

Although cancer prevalence was comparable in both cohorts, a longer follow-up might have revealed differences, but when truncated Kaplan-Meier curves were performed at 6, 12, 18 and 24 months (Supplementary Fig. 1), no differences were observed, suggesting that the shorter follow-up in the literature cases did not have a significantly impact the overall analysis.

Accurate ascertainment of malignancies in the context of TTS is clinically pertinent, as previous studies have shown that this subgroup experiences a higher incidence of adverse events [43]—both during the index hospitalization and over longitudinal follow-up.

Beta-blockers are widely used for the treatment of TTS (up to 75% in some series [2]) and have recently been shown to reduce mortality [44]. In this subgroup of patients with TTS, the use of beta-blockers appears to be a reasonably safe therapy, as the pacemaker ensures a minimum heart rate.

In the future, the potential occurrence of TTS as a complication of pacemaker implantation should be considered, particularly in relation to implant type (transvenous or leadless). However, retrospectively identifying TTS requires large databases [45].

There is a limited amount of data available on cases of TTS associated with pacemaker implantation published in the literature. The longest series published to date, with 9 cases [6], could not be included in our work as it did not strictly meet the revised Mayo criteria because in four of the nine patients, coronary anatomy was not assessed.

Another limitation of the study is that we do not have access to a number of patients in the TTS associated with pacemaker implantation group who received isoproterenol (a drug commonly used in patients with conduction disturbances), which could act as an adrenergic trigger, thus generating potential confounding.

As this is an observational study, it is not possible to fully ensure causality. However, the 21 cases in the RETAKO registry have been thoroughly evaluated to confirm the temporal relationship between pacemaker implantation and the development of TTS. However, since we did not have access to the medical records of the 20 patients included in the systematic literature review, we were unable to reconfirm this association in this subgroup of patients.

The low recurrence rate may be explained by the limited follow-up reported in the literature; in many cases, follow-up was restricted to a single outpatient visit or ended at hospital discharge. While the recurrence rate in TTS is generally low—approximately 4% in the overall RETAKO cohort—we believe that the absence of recurrence in the pacemaker-associated TTS group is more likely due to insufficient follow-up and a small sample size than a distinctive feature of this population. Therefore, these findings should be interpreted with caution.

TTS following pacemaker implantation more frequently presents with syncope than with chest pain at the its initial presentation. TTS triggered by pacemaker implantation is associated with a longer cQT interval, lower LVEF, a higher rate of acute kidney injury and cardiogenic shock, with no differences in all-cause mortality or TTS recurrences, compared with TTS not associated with pacemaker implantation. However, our study shows that TTS following pacemaker implantation is associated with prognostic outcomes similar to other TTS cases secondary to physical triggers.

All the material is available through the corresponding author via e-mail upon reasonable request.

GGM, RV and ING designed the research study. GGM, ING and RV drafted the manuscript and performed the research. RSDH analyzed the data and reviewed critical portions of the manuscript such as: methodology and statistical analysis. OV, AMG, AU, MCP, EBP, JEV, CFC, MAD, VB, APC, MGM, BA and FA contributed to editorial changes in the manuscript, as well as the acquisition of data. All authors read and approved the final manuscript. All authors have participated sufficiently in the work and agreed to be accountable for all aspects of the work.

We conducted this study in accordance with the Helsinki Declaration and approval was granted by the Hospital Clínico San Carlos (Madrid, España) Ethics Committee of the coordinating center (11/349-E). All patients provided signed informed consent.

The authors thank all the cardiologists from the various hospital centers participating in the RETAKO registry, whose nationwide patient enrollment made this study possible.

The authors thank Fundación Interhospitalaria para la Investigación Cardiovascular (FIC) for their support.

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Supplementary material associated with this article can be found, in the online version, at https://doi.org/10.31083/RCM39440.

References

Publisher’s Note: IMR Press stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.