1 Department of Rheumatology and Immunology, Nanchong Central Hospital (Nanchong Clinical Medical Research Center)—The Second Clinical Medical College of North Sichuan Medical College, 637000 Nanchong, Sichuan, China

2 Key Laboratory of Inflammation and Immunity Nanchong, Nanchong Central Hospital (Nanchong Clinical Medical Research Center)—The Second Clinical Medical College of North Sichuan Medical College, 637000 Nanchong, Sichuan, China

Abstract

To develop a predictive model for cardiac valve calcification (CVC) in rheumatoid arthritis (RA) patients using a novel nomogram approach.

We analyzed data from patients diagnosed with RA at the Department of Rheumatology and Immunology, Nanchong Central Hospital, between January 1, 2020, and October 31, 2023. Data were gathered on patient demographics, disease characteristics, laboratory tests, and imaging findings. Patients were randomly divided into a training set (n = 210) and a validation set (n = 140), in a ratio of 6:4, respectively. Least absolute shrinkage and selection operator (LASSO) regression was employed to identify risk predictors. Meanwhile, both single-factor and multi-factor logistic regression analyses were conducted to ascertain the risk factors associated with cardiac valve calcification. A predictive model was constructed using R software and validated through Bootstrap techniques. The performance of the model was evaluated using the area under the receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curve (AUC), calibration curves, and decision curve analysis (DCA).

A total of 350 RA patients were included in the study, of whom 67 (19.1%) were diagnosed with CVC. Multivariate analysis identified several significant risk factors for CVC, including hypertension (odds ratio (OR) = 15.496, 95% confidence interval (CI): 4.373–54.916; p < 0.01), age (OR = 1.118, 95% CI: 1.003–1.246; p = 0.043), disease duration (OR = 1.238, 95% CI: 1.073–1.427; p = 0.003), and elevated erythrocyte sedimentation rate (ESR) (OR = 1.026, 95% CI: 1.006–1.047; p = 0.012). The predictive model demonstrated excellent discriminatory performance, with an AUC of 0.9474 (95% CI: 0.9044–0.9903) in the training set. The model also showed strong internal validity (C-index = 0.947) and maintained robust performance in external validation (AUC = 0.9390; 95% CI: 0.8880–0.9893). Calibration analysis further confirmed the predictive accuracy and reliability of the model.

The developed model can effectively identify RA patients at high risk for CVC. This tool provides a scientific basis for clinical decision-making and has significant potential for enhancing patient management and outcomes.

Keywords

- rheumatoid arthritis

- calcification of heart valves

- prediction model

Rheumatoid arthritis (RA) is a chronic autoimmune disease primarily characterized by symmetrical polyarthritis. In addition to joint involvement, RA often presents with systemic manifestations, including cardiovascular complications [1, 2]. Among these, cardiac valve calcification (CVC) has attracted increasing attention due to its significant impact on morbidity and mortality. CVC refers to the progressive deposition of lipids and calcium on the heart valves, leading to thickening, stiffening, and impaired valve function [3]. RA patients are at a substantially higher risk of developing CVC than the general population, with an approximately fourfold increase in prevalence [4, 5, 6, 7].

Although the precise mechanisms underlying CVC in RA remain unclear, chronic inflammation, endothelial dysfunction, and autoimmune-mediated vascular damage have been implicated [8, 9, 10]. Notably, rheumatoid nodules—granulomatous lesions typically associated with severe seropositive RA—may occasionally develop on heart valve cusps or annuli. These nodules are believed to promote localized inflammatory injury, fibrosis, and eventual calcification [11, 12]. In addition, clinical factors such as advanced age, prolonged disease duration, hypertension, and elevated C-reactive protein (CRP) or erythrocyte sedimentation rate (ESR) levels have also been linked to an increased risk of CVC [10].

However, in routine clinical settings, identifying RA patients at high risk for CVC remains challenging due to the absence of simple, disease-specific predictive tools. Therefore, this study aimed to develop and validate a predictive model for CVC in RA patients using a nomogram approach based on routinely available clinical and laboratory parameters. The proposed model is expected to assist clinicians in individualized cardiovascular risk assessment and to guide timely preventive interventions, ultimately improving the prognosis and quality of life in this patient population.

Patients who were diagnosed with rheumatoid arthritis at the Department of Rheumatology and Immunology of Nanchong Central Hospital from January 1, 2020, to October 31, 2023, were enrolled as participants for this study.

Inclusion Criteria: (1) A confirmed diagnosis of rheumatoid arthritis, adhering to the 2010 American College of Rheumatology/European League Against Rheumatic Diseases criteria [13]. (2) Availability of complete case data and demonstrated good cooperation during hospitalization. (3) A minimum disease duration of one year. (4) The study included patients aged 18 to 88 years. (5) Patients with complete case data and stable follow-up records during hospitalization were included.

We excluded conditions that could independently influence heart valve morphology or inflammation markers, to isolate RA-related effects. Exclusion Criteria: (1) A history of congenital heart disease, heart valve disease, rheumatic heart disease, or infective endocarditis. (2) Cases of liver or renal failure. (3) Occurrences of tumors, cardiovascular diseases, severe trauma, or acute infections within the last week.

This retrospective analysis was approved by the Ethics Committee of Nanchong Central Hospital [2024 Review (040)]. All procedures were conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki.

Collected data included demographic details (gender, age, duration of disease, history of hypertension) and clinical parameters. Venous blood was drawn on the day of admission for comprehensive laboratory tests: CRP, potassium, phosphorus, sodium, calcium, white blood cells (WBC), platelets (Plt), ESR, cyclic citrulline peptide antibody (CCP), rheumatoid factor (RF), complements C3, C1q, C4, immunoglobulin G (IgG), high-density lipoprotein (HDL), low-density lipoprotein (LDL), lipoprotein a, lipoprotein b, total cholesterol, triglycerides (TG), uric acid, hematocrit, hemocreatinine, cystatin C, albumin, pre-albumin and glucose. These markers were collected to explore possible systemic immune activity related to vascular and valvular pathology in RA, although their association with CVC remains uncertain. These samples were analyzed using a G9206 automatic biochemistry analyzer (Myriad Biomedical Co., Ltd., Shenzhen, China) and a Cobas E601 electrochemiluminescence immunoassay analyzer (Roche Diagnostics, Penzberg, Germany). Additionally, echocardiography and disease duration were recorded. Disease duration refers to the time since confirmed RA diagnosis. To ensure adequate representation of CVC cases and to maintain robust model validation despite the modest overall sample size, the data were randomly divided into a training set (60%) and a validation set (40%) using R software (R 4.3.1, Lucent Technologies, https://www.r-project.org/). The training set was utilized to construct the nomogram model, and the validation set was used to assess the model’s predictive efficacy.

Diagnosis of heart valve calcification was performed using an EPIQ7 echocardiographic machine (Philips, Amsterdam, the Netherlands) by two experienced sonographers, each with over five years of cardiovascular imaging experience. Standard transthoracic echocardiographic views were employed, primarily including the parasternal long-axis view and the apical four-chamber view. Calcification was defined as the presence of one or more strong echogenic areas measuring

Statistical evaluation was performed using SPSS version 23.0 (IBM, Armonk, NY, USA) and R version 4.3.1 (Murray Hill, NJ, USA). For continuous variables that did not conform to a normal distribution, the normality was assessed using the Shapiro–Wilk test. In cases where the Shapiro–Wilk test indicated a non-normal distribution, we employed the Mann–Whitney U test to compare differences between two groups. The results of these variables were reported as median values with interquartile ranges (Q1, Q3). Categorical data were processed using the chi-square test and are shown as n (%). Least absolute shrinkage and selection operator (LASSO) regression analysis was employed to identify risk factors, while logistic regression analysis was utilized for verification. Lambda.min refers to the value of the penalty term

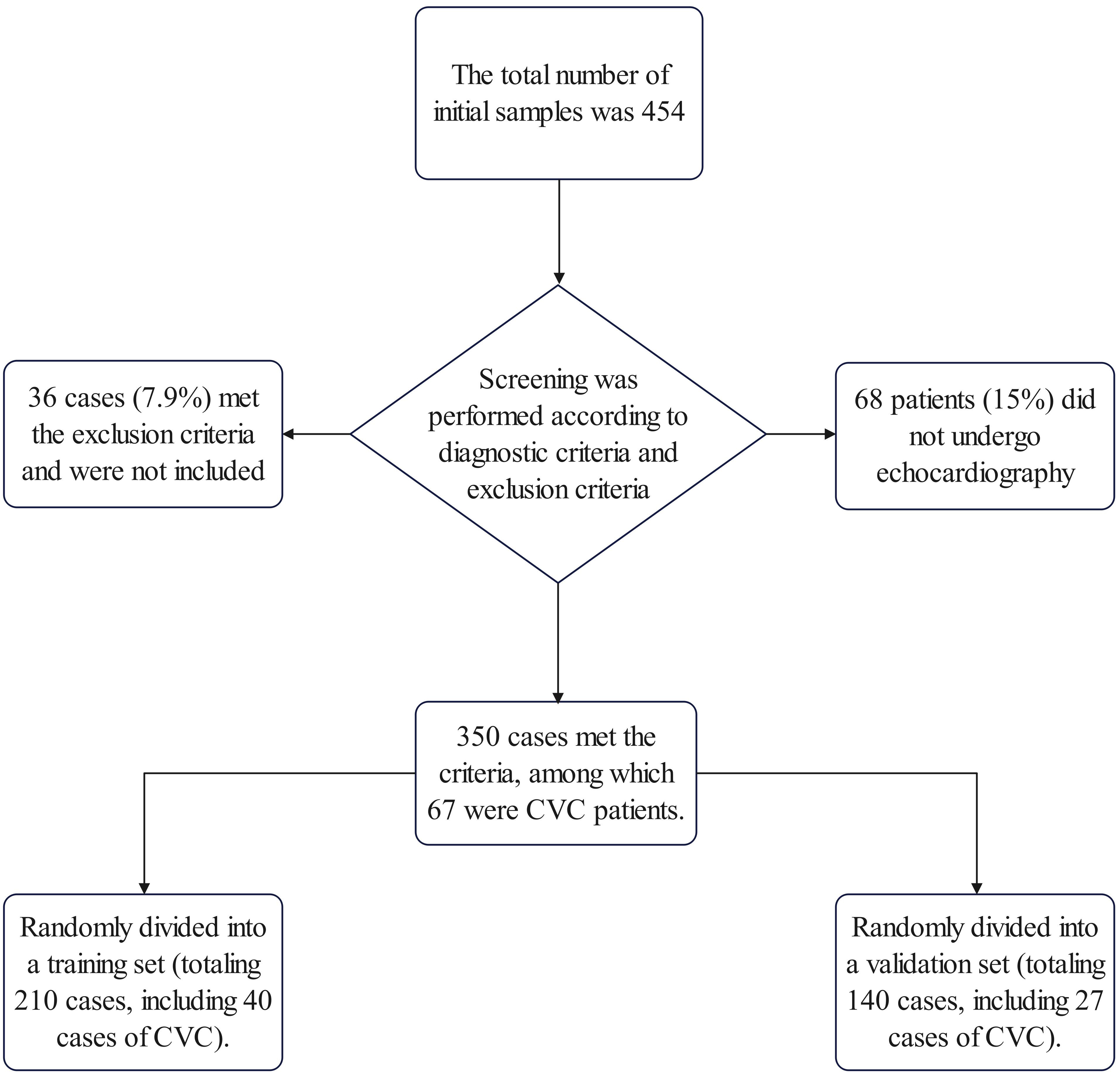

After screening according to the exclusion criteria, 350 patients were finally included. This cohort comprised 67 individuals (19.1%) with CVC and 283 (80.9%) without. Sixty-eight patients were excluded from the CVC analysis due to the absence of cardiac ultrasonography data, and an additional 36 were omitted based on exclusion criteria related to existing cardiac conditions and other factors (Fig. 1). The demographic breakdown showed 243 females (69%) and 107 males (31%), with a mean age of 68 (57, 73) years and an average disease duration of 10 (7, 13) years (Table 1). Within the CVC subgroup, there were 46 females (69%) and 21 males (31%), with 60 patients (89.6%) had hypertension.

Fig. 1.

Fig. 1. Workflow of sample collection in this study. CVC, cardiac valve calcification.

| Variables | Total (n = 350) | RA patients without cardiac valve calcification CVC (n = 283) | RA patients with CVC (n = 67) | p | |

| Hypertension, n (%) | |||||

| Yes | 88 (25) | 28 (10) | 60 (90) | ||

| No | 262 (75) | 255 (90) | 7 (10) | ||

| Sex, n (%) | 0.879 | ||||

| Male | 107 (31) | 86 (30) | 21 (31) | ||

| Female | 243 (69) | 197 (70) | 46 (69) | ||

| Duration of disease, median (Q1, Q3) | 10 (7, 13) | 9 (6, 11) | 15 (12.5, 18) | ||

| Age, median (Q1, Q3) | 68 (57, 73) | 62 (55.5, 71) | 75 (72, 78.5) | ||

| K, median (Q1, Q3) | 3.77 (3.47, 4.05) | 3.77 (3.46, 4.06) | 3.77 (3.5, 4.04) | 0.862 | |

| P, median (Q1, Q3) | 1.03 (0.91, 1.19) | 1.03 (0.9, 1.19) | 1.03 (0.92, 1.19) | 0.832 | |

| Na, median (Q1, Q3) | 140.6 (138.7, 142.4) | 140.7 (138.8, 142.6) | 139.8 (137.6, 141.9) | 0.039 | |

| Ca, median (Q1, Q3) | 2.15 (2.07, 2.23) | 2.15 (2.07, 2.23) | 2.17 (2.08, 2.22) | 0.579 | |

| Plt, median (Q1, Q3) | 252 (197, 333) | 252 (197, 332) | 252 (194, 336) | 0.890 | |

| WBC, median (Q1, Q3) | 7.03 (5.62, 9.32) | 7.05 (5.69, 9.16) | 6.94 (5.31, 9.37) | 0.539 | |

| ESR, median (Q1, Q3) | 68.5 (41, 99.8) | 68.5 (39.5, 90.5) | 92 (68.5, 112) | ||

| CCP, median (Q1, Q3) | 251.15 (251.15, 251.15) | 251.15 (251.15, 251.15) | 251.15 (251.15, 265.60) | 0.472 | |

| RF, median (Q1, Q3) | 260 (120.25, 473.25) | 260 (111, 409) | 260 (221, 619) | 0.069 | |

| C3, median (Q1, Q3) | 981.5 (873, 1070) | 981.5(865, 1080) | 981.5 (892, 1020) | 0.505 | |

| C1q, median (Q1, Q3) | 180 (161, 201) | 180 (161, 201) | 180 (160.5, 203.5) | 0.869 | |

| C4, median (Q1, Q3) | 219.5 (185, 255.8) | 219.5 (185.5, 265.5) | 219.5 (181, 230.5) | 0.250 | |

| Lipoprotein B, median (Q1, Q3) | 0.88 (0.77, 1.01) | 0.88 (0.79, 1.03) | 0.88 (0.71, 0.94) | 0.273 | |

| Lipoprotein A, median (Q1, Q3) | 167.65 (122.95, 252.35) | 167.65 (115, 234.15) | 167.65 (167.65, 314.95) | 0.016 | |

| IgG, median (Q1, Q3) | 13.7 (11.8, 16.4) | 13.7 (11.7, 16) | 13.7 (12.6, 18.8) | 0.115 | |

| Cholesterol, median (Q1, Q3) | 4.3 (3.72, 4.94) | 4.3 (3.87, 5) | 4.01 (3.33, 4.52) | 0.003 | |

| HDL, median (Q1, Q3) | 1.22 (1.02, 1.49) | 1.22 (1.03, 1.50) | 1.22 (0.97, 1.42) | 0.413 | |

| LDL, median (Q1, Q3) | 2.41 (1.99, 2.89) | 2.42(2.08, 2.92) | 2.21 (1.81, 2.64) | 0.006 | |

| TG, median (Q1, Q3) | 1.15 (0.87, 1.67) | 1.15 (0.89, 1.67) | 1.15 (0.84, 1.67) | 0.691 | |

| UA, median (Q1, Q3) | 270 (220.1, 337) | 269 (220.1, 325.3) | 284.5 (219.6, 361.7) | 0.187 | |

| Urea, median (Q1, Q3) | 5.15 (4.01, 6.69) | 5.12 (3.93, 6.45) | 5.73 (4.53, 7.61) | 0.021 | |

| Cystatin C, median (Q1, Q3) | 1.24 (1.00, 1.65) | 1.21 (0.97, 1.55) | 1.48 (1.11, 1.82) | ||

| Cr, median (Q1, Q3) | 56.9 (47, 69) | 56.2 (47, 67.5) | 60 (47, 75.3) | 0.144 | |

| Albumin, mean | 38.51 | 38.75 | 37.49 | 0.040 | |

| Prealbumin, median (Q1, Q3) | 180 (135, 231) | 186 (136, 235.5) | 169 (134.5, 220.5) | 0.183 | |

| CRP, median (Q1, Q3) | 38.4 (11.0, 68.7) | 38 (9.6, 64.9) | 44.4 (15.4, 76.7) | 0.119 | |

| Glu, median (Q1, Q3) | 5.61 (4.86, 6.82) | 5.50 (4.76, 6.79) | 5.98 (5.42, 7.86) | 0.001 | |

CVC, cardiac valve calcification; RA, rheumatoid arthritis; ESR, erythrocyte sedimentation rate; CRP, C-reactive protein; RF, rheumatoid factor; CCP, cyclic citrullinated peptide antibody; WBC, white blood cells; Plt, platelets; IgG, immunoglobulin G; HDL, high-density lipoprotein; LDL, low-density lipoprotein; TG, triglycerides; UA, uric acid; Cr, creatinine; Na, sodium; K, potassium; Ca, calcium; P, phosphorus; Glu, glucose.

In addition to the identification of calcification, key echocardiographic parameters were analyzed to further characterize valvular and cardiac function in RA patients. Among patients with cardiac valve calcification, the average thickness of the aortic valve was 2.8

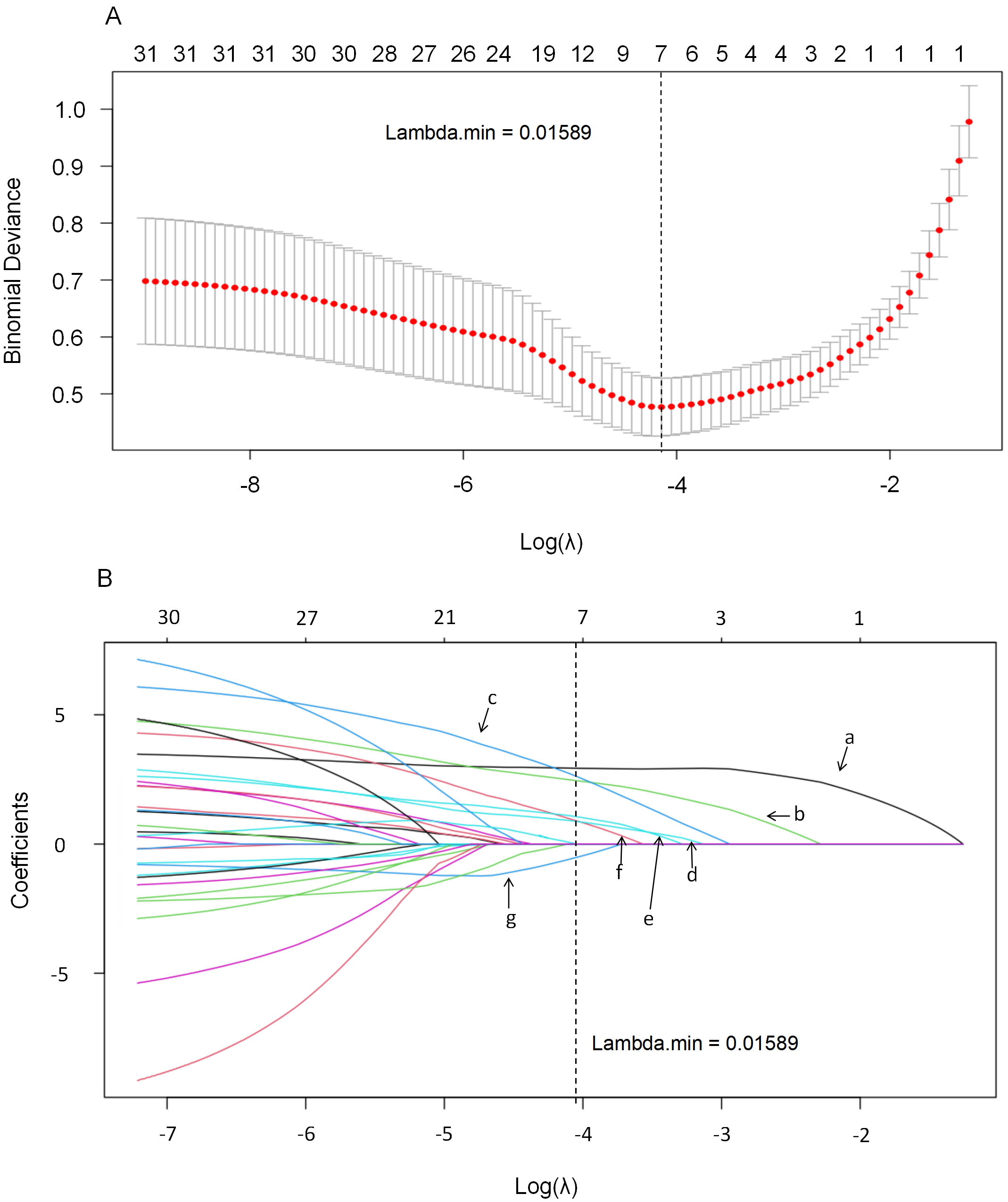

LASSO regression was applied to select variables with non-zero coefficients that may be predictive of CVC. The Lambda.min value (0.01589) was determined through 10-fold cross-validation to minimize binomial deviance. Selected variables were subsequently entered into univariate and multivariate logistic regression analyses. The 31 variables mentioned were included in the LASSO regression analysis, with Lambda.min serving as the cutoff point for screening the independent variables. At a Lambda value of 0.01589, seven variables with non-zero coefficients were identified: age, disease duration, hypertension, ESR, urea, cystatin C, and creatinine. The LASSO regression system profile and cross-validation results are illustrated in Fig. 2.

Fig. 2.

Fig. 2. This figure illustrates the application of the LASSO regression model for variable selection within the cohort. The model employs a 10-fold cross-validation method (A) to enhance its reliability. Using Lambda.min (B) as the cutoff point, the analysis identifies seven predictors with non-zero coefficients: (a) Hypertension; (b) Duration of disease; (c) Age; (d) ESR; (e) Urea; (f) Cystatin C; and (g) Cr. Cr, creatinine. LASSO, least absolute shrinkage and selection operator.

The analysis began with a univariate logistic regression using data from the training set, with the presence of CVC as the outcome variable (coded as no = 0, yes = 1). Significant predictors included age, disease duration, hypertension, ESR, urea, cystatin C, and creatinine (all p

| Predictor variable | B | SE | Wald value | p-value | OR value | 95% CI |

| Disease duration | 0.213 | 0.073 | 8.588 | 0.003 | 1.238 | 1.073–1.427 |

| Age | 0.111 | 0.055 | 4.080 | 0.043 | 1.118 | 1.003–1.246 |

| Hypertension | 2.741 | 0.646 | 18.024 | 15.496 | 4.373–54.916 | |

| ESR | 0.026 | 0.011 | 6.243 | 0.012 | 1.026 | 1.006–1.047 |

| Cystatin C | 0.451 | 0.504 | 0.802 | 0.37 | 1.570 | 0.585–4.213 |

| Urea | 0.107 | 0.141 | 0.576 | 0.448 | 1.113 | 0.844–1.468 |

OR, odds ratio; CI, confidence interval; ESR, erythrocyte sedimentation rate.

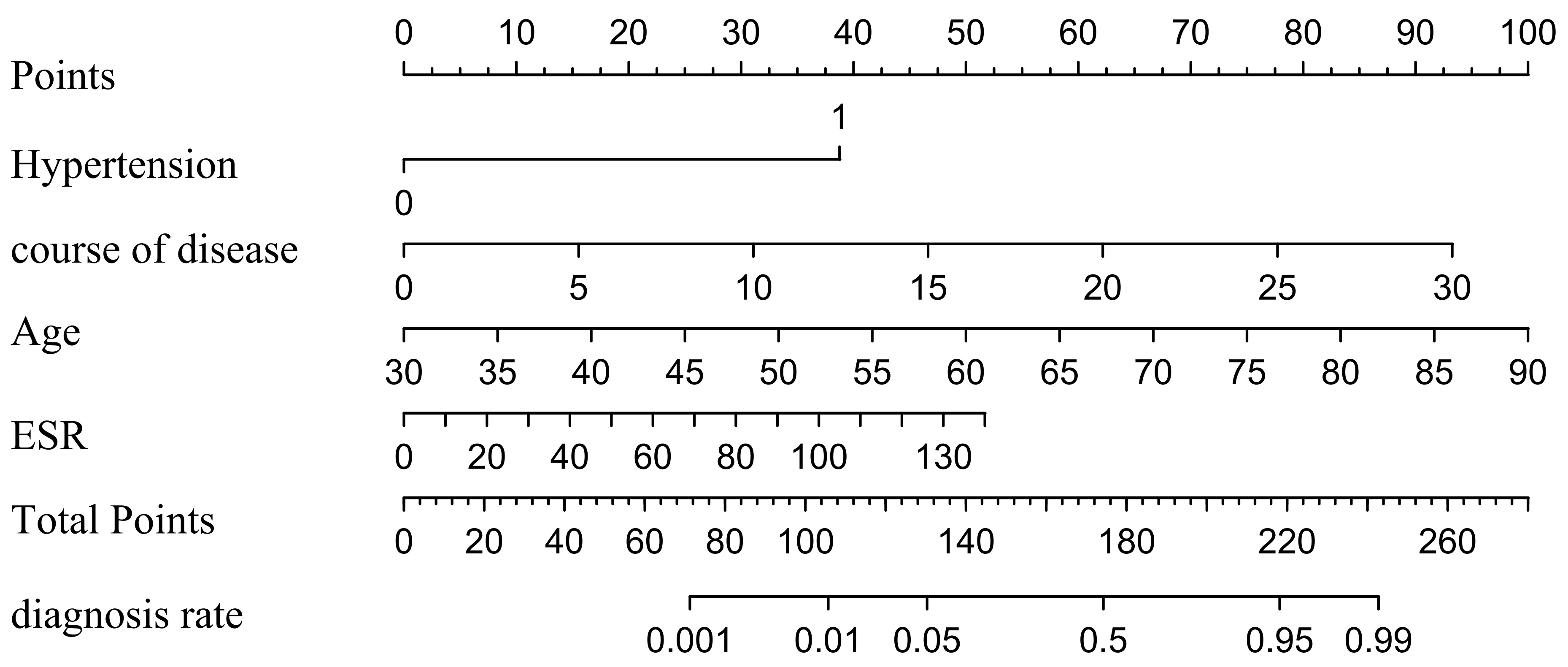

Fig. 3.

Fig. 3. Based on the results of multi-factor logistic analysis, predicting the probability of CVC in RA patients. CVC, cardiac valve calcification; RA, rheumatoid arthritis; ESR, erythrocyte sedimentation rate.

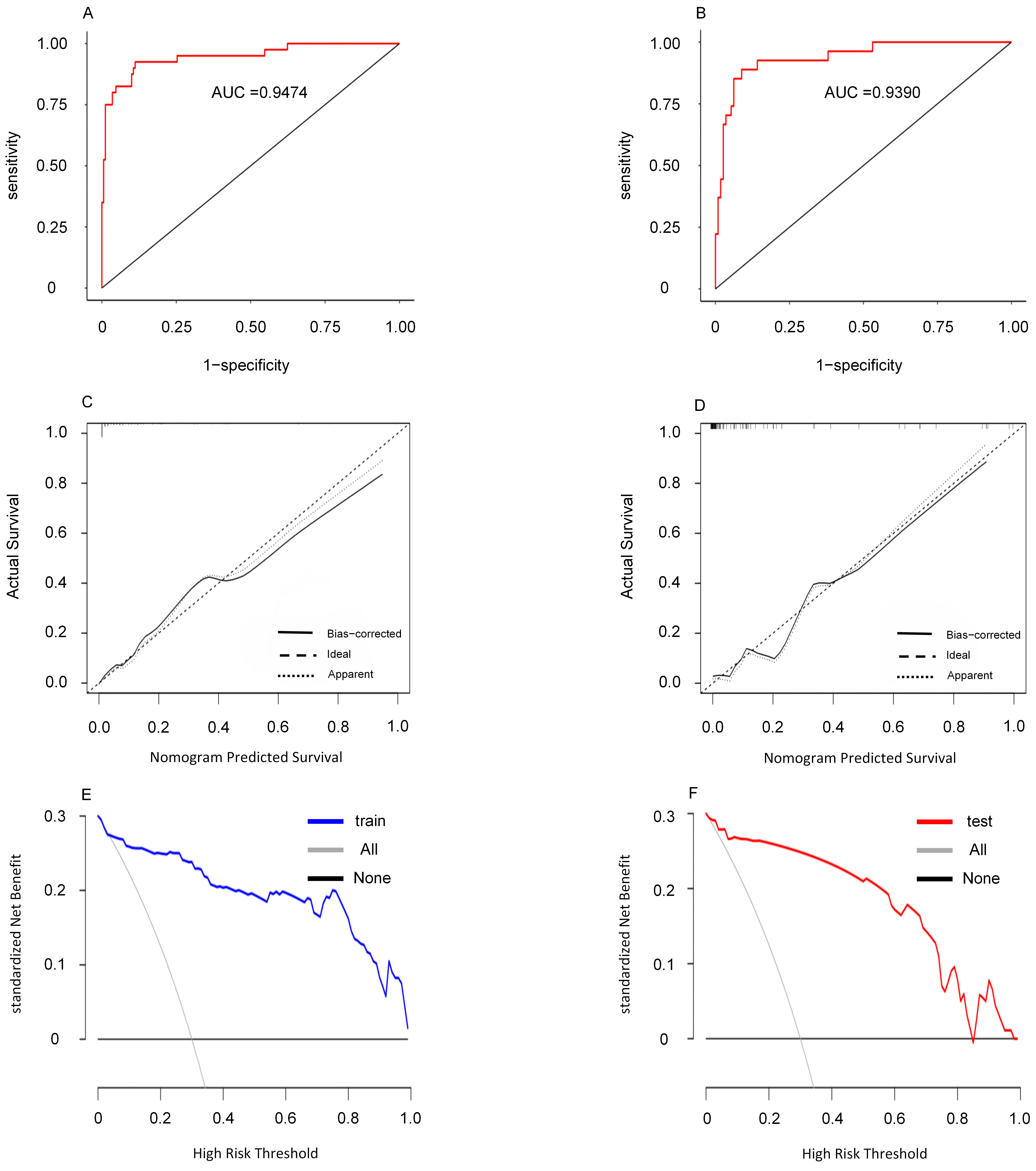

The predictive performance of the model was validated with ROC curves, achieving an area under the receiver operating characteristic curve (AUC) of 0.9474 (95% CI: 0.9044–0.9903) for the training set and 0.9390 (95% CI: 0.8880–0.9893) for the validation set. Calibration curves displayed excellent agreement between observed occurrences and predictions, while DCA indicated substantial clinical utility and net benefit across a wide score range (Fig. 4).

Fig. 4.

Fig. 4. This figure presents an evaluation of the nomogram, including the ROC curve (A), calibration curve (B), calibration curve (C), the ROC curve (D), decision curve (E) and decision curve (F) are shown for the validation centralized nomogram. In the decision curve, the term ‘all’ denotes the scenario in which all patients develop CVC, while ‘None’ indicates the scenario where no patients develop CVC. CVC, cardiac valve calcification; ROC, receiver operating characteristic; AUC, area under the receiver operating characteristic curve.

Despite notable advancements that have reduced overall mortality among RA patients, there remains a concerning increase in mortality associated with concomitant cardiovascular diseases (CVD). This trend underscores the critical need for early diagnosis and proactive intervention in the precision medicine era. In this study, we have identified age, disease duration, hypertension, and blood sedimentation rate as independent risk factors for CVC in RA patients, utilizing both LASSO regression model, univariate and multivariate logistic regression analyses. A nomogram model was further constructed to predict the risk of CVC in RA patients, aiming to identify patients at high risk of CVC as early as possible.

Savage et al. [15] found in early studies that as age increases, the risk of CVC also rises, with a positive correlation between prevalence and age. In the general population, some studies suggest that the formation of CVC may be influenced by several factors, including passive calcium deposition, lipid deposition, and changes in hemodynamics [16]. This study found that the age of the group with valve calcification was generally higher than that of the group without valve calcification. While this does not exclude the possibility that the observed differences may be attributed to the aforementioned factors, it also suggests that inflammatory stimuli may contribute to the formation of CVC. Furthermore, as previously mentioned, CVC serves as a risk marker for cardiovascular disease, potentially leading to earlier occurrences of cardiovascular events compared to the general population. Further research by Fulkerson et al. [17] indicates that CVC may lead to severe cardiovascular conditions such as valvular stenosis [18], endocarditis [19], atrial fibrillation, and atrioventricular block [15, 20], with a noted potential for triggering cerebrovascular events [21]. These findings highlight the importance of early and precise assessment and intervention for heart valve issues in RA patients. By doing so, we can possibly slow the disease’s progression and, in some instances, decrease the incidence of both cardiovascular and cerebrovascular complications. Therefore, implementing regular and thorough cardiovascular assessments for RA patients—especially those who present with the identified risk factors—can be crucial in mitigating the risk of severe complications. This strategic approach not only helps in managing the immediate health concerns but also contributes to the long-term well-being and quality of life of the patients, thereby aligning with the goals of modern precision medicine.

Historical histopathologic studies have revealed that valvular calcification can develop in the context of systemic inflammation, where prolonged inflammatory states contribute to lipid deposition, macrophage and T-cell infiltration, and ultimately, disruption of the basement membrane—factors that collectively initiate the production of CVC [22]. It has been noted that an extended duration of disease significantly elevates the risk for CVC among RA patients. This observation is supported by findings from Yiu et al. [10], which indicated a marked increase in CVC prevalence when disease duration exceeded ten years. Consequently, RA patients with CVC exhibit a considerably higher likelihood of experiencing future cardiovascular events compared to the general population, potentially leading to severely diminished prognosis and quality of life [17, 18, 19, 20, 21]. Thus, early screening for cardiovascular complications and thorough cardiac function assessments are critical for RA patients who have lived with the disease for a decade or more. These measures are vital not only for managing current health concerns but also for implementing timely interventions to prevent severe cardiovascular diseases.

The precise mechanisms through which hypertension contributes to CVC remain somewhat elusive but are thought to involve sustained high blood flow against valve surfaces, increasing transvalvular pressure that over time may cause structural damage including fiber breakage and calcium salt deposition. This theory is corroborated by a comprehensive meta-analysis of cross-sectional and case-control studies involving over 6450 hypertensive patients, which suggested a potential link between high blood pressure and the development of CVC [11]. In our cohort, an overwhelming majority (89.6%) of patients diagnosed with CVC also had hypertension, echoing the broader data trends and suggesting that hypertension may exacerbate the progression of cardiovascular diseases in those already compromised by RA. Consequently, rigorous blood pressure monitoring and holistic management of both hypertension and CVC are imperative in the treatment protocol for RA patients to mitigate the risk of further cardiovascular complications.

Although hypertension is a recognized independent risk factor for cardiac valve calcification in the general population, its impact in RA patients may be compounded by chronic systemic inflammation and immune-mediated endothelial injury. In RA, prolonged exposure to elevated cytokine levels, oxidative stress, and vascular dysfunction may accelerate the deleterious effects of high blood pressure on valvular tissue. Our study revealed that 90% of RA patients with CVC had coexisting hypertension, supporting the hypothesis that inflammatory and hemodynamic factors may synergistically promote calcification in this unique clinical setting. Therefore, the contribution of hypertension in RA patients cannot be interpreted in isolation but should be considered within the broader context of autoimmune-mediated cardiovascular risk.

In this study, ESR has been identified as a potential risk factor for CVC in patients with RA. Elevated ESR levels are often observed in RA patients, likely reflecting ongoing disease activity and inflammation levels. Previous research by Ingelsson et al. [23] in a longitudinal cohort study suggested that high ESR is a significant predictor of heart failure, a finding further supported by Maradit-Kremers et al. [24], who reported that prolonged inflammatory stimuli in RA patients might lead to heart failure. These studies imply a possible link between elevated ESR and the development of CVC, although direct correlations are yet to be extensively documented. Our results open new avenues for research into the mechanisms underlying the relationship between ESR and CVC. Going forward, we aim to delve deeper into this association to devise more accurate diagnostic and preventative strategies for cardiovascular complications in RA patients. This study also highlights the importance of vigilant monitoring of ESR levels in clinical practice, which could be crucial for the timely detection and prevention of CVC.

Interventions aimed at delaying the progression of valve calcification in RA should address both inflammation and traditional cardiovascular risk factors. Biologic disease-modifying antirheumatic drugs (DMARDs), such as TNF-

Numerous studies have investigated the potential link between CRP and CVC, yet this study did not establish a clear association between them. This outcome introduces both challenges and opportunities for further research, underscoring the need to delve deeper into the underlying causes and potential mechanisms. To enhance our understanding of this complex relationship, more comprehensive studies are required. Firstly, increasing the sample size would allow for a better representation of the general population and could help validate the findings more robustly. Secondly, employing advanced research techniques and tools, such as genomics and proteomics, could provide greater insights into the biochemical interactions at play. Additionally, conducting longitudinal studies to monitor CRP levels over time relative to CVC development could offer valuable data on how these factors correlate longitudinally. By expanding the scope of our research and employing these methods, we aim to uncover nuanced details about the relationship between CRP and CVC. This could potentially lead to innovative approaches for the prevention and treatment of CVC, thereby contributing to better cardiovascular health outcomes.

Importantly, the predictive model developed in this study incorporates both traditional cardiovascular risk factors and RA-specific indicators, such as ESR and disease duration, which reflect systemic inflammation and autoimmune burden. While hypertension and age are well-established risk factors for valve calcification, their inclusion alongside RA-specific markers adds novel clinical value. The use of a nomogram—a visual, user-friendly tool—allows for individualized risk estimation in clinical practice, facilitating early identification and intervention in high-risk RA patients. To our knowledge, this is the first study to construct such an integrative and quantitative model tailored to RA populations, addressing a critical gap in cardiovascular risk stratification for this group.

This research has its limitations that must be acknowledged. Primarily, being a single-center study with a relatively small sample size and data collected at a single point in time, there is a potential for bias which might affect the generalizability of the findings. Furthermore, while CRP is recognized as a marker for cardiovascular issues [12, 25, 26], our analysis did not find a definitive link between CRP levels and CVC. This could be due to several factors including the scale of the sample size, the particular characteristics of the study population, and the data collection and processing methodologies employed. Additional studies are necessary to explore this relationship further, considering other potential confounding variables such as lifestyle, genetic predispositions, and environmental influences which could impact the dynamics between CRP and CVC. Although an association between CRP and CVC is hypothesized, the complexity of this relationship suggests that a deeper understanding is required to draw conclusive links. Given the retrospective, single-center design of the study, selection bias may have influenced the findings. Patients with incomplete clinical records or those demonstrating poor compliance during hospitalization were excluded, potentially resulting in the underrepresentation of individuals with more severe disease or atypical presentations. This may limit the generalizability of the nomogram to broader RA populations. Future studies should aim to validate this model prospectively across multiple centers with more diverse cohorts, and explore the integration of imaging or biomarker-based indicators to enhance its predictive performance.

Upon analyzing the data and refining our predictive model, we identified that age, disease duration, hypertension, and ESR are key predictors of CVC in RA patients. These factors are vitally important for pinpointing patients at high risk for CVC. This model provides a potentially valuable tool to aid clinical risk assessment, though further prospective validation is warranted.

CVC, cardiac valve calcification; RA, rheumatoid arthritis; ROC, receiver operating characteristic; DCA, decision curve analysis; CRP, C-reactive protein; BNP, B-type natriuretic peptide; hsTnT, hypersensitive troponin; WBC, white blood cells; Plt, platelets; ESR, erythrocyte sedimentation rate; CCP, cyclic citrulline peptide; RF, rheumatoid factor; IgG, immunoglobulin G; HDL, high-density lipoprotein; LDL, low-density lipoprotein; TG, triglycerides.

All data generated or analysed during this study are included in this. Further enquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

YWL is responsible for guarantor of integrity of the entire study, study design, literature research, clinical studies, experimental studies, data acquisition & analysis, statistical analysis, manuscript preparation & editing & review; XZ is responsible for the data acquisition; XYH is responsible for the definition of intellectual content, literature research, clinical studies; MLL is responsible for the literature research, clinical studies; QQX is responsible for the clinical studies; SQS is responsible for the study concepts, manuscript editing. All authors contributed to the conception and editorial changes in the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript. All authors have participated sufficiently in the work and agreed to be accountable for all aspects of the work.

This retrospective analysis was approved by the Ethics Committee of Nanchong Central Hospital [2024 Review (040)]. Written informed consent was obtained from all individuals included in this study. The study was carried out in accordance with the guidelines of the Declaration of Helsinki.

Not applicable.

This study was supported by 2023 Nanchong City Science and Technology Plan Project (23JCYJPT0020).

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Supplementary material associated with this article can be found, in the online version, at https://doi.org/10.31083/RCM38668.

References

Publisher’s Note: IMR Press stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.