1 Department of Cardio-Metabolic Medicine Center, Fuwai Hospital, National Center for Cardiovascular Diseases, Chinese Academy of Medical Sciences and Peking Union Medical College, 100006 Beijing, China

2 Intensive Care Center, Fuwai Hospital, National Center for Cardiovascular Diseases, Chinese Academy of Medical Sciences and Peking Union Medical College, 100006 Beijing, China

3 Department of Cardiology, Tibet Autonomous Region People’s Hospital, 850002 Lasa, Tibet Autonomous Region, China

4 Department of Cardiology, Fuwai Yunnan Hospital, Chinese Academy of Medical Sciences, Affiliated Cardiovascular Hospital of Kunming Medical University, 650000 Kunming, Yunnan, China

5 Department of Cardiology, Coronary Artery Disease Center, Fuwai Hospital, National Center for Cardiovascular Diseases, Chinese Academy of Medical Sciences and Peking Union Medical College, 100006 Beijing, China

†These authors contributed equally.

Abstract

The applicability of currently established high-risk inflammatory criteria to East Asian patients is unknown, particularly concerning the hypersensitive C-reactive protein (hs-CRP) cutoff value. In addition, the role of cholesterol and inflammation in determining the prognosis of these patients might shift after the patient accepts lipid-lowering treatments. This study aimed to explore the high-risk hs-CRP cutoff value and compare the prognostic value between inflammation and cholesterol risk in the East Asian population after treatment with percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI).

Post-PCI patients with serial hs-CRP and low-density lipoprotein cholesterol (LDL-C) level measurements were retrospectively enrolled. Major adverse cardiovascular and cerebrovascular events (MACCEs) were defined as a composite of cardiovascular death, non-fatal acute myocardial infarction (AMI), non-fatal stroke, and unplanned coronary revascularization. The association between residual risks and MACCEs was evaluated.

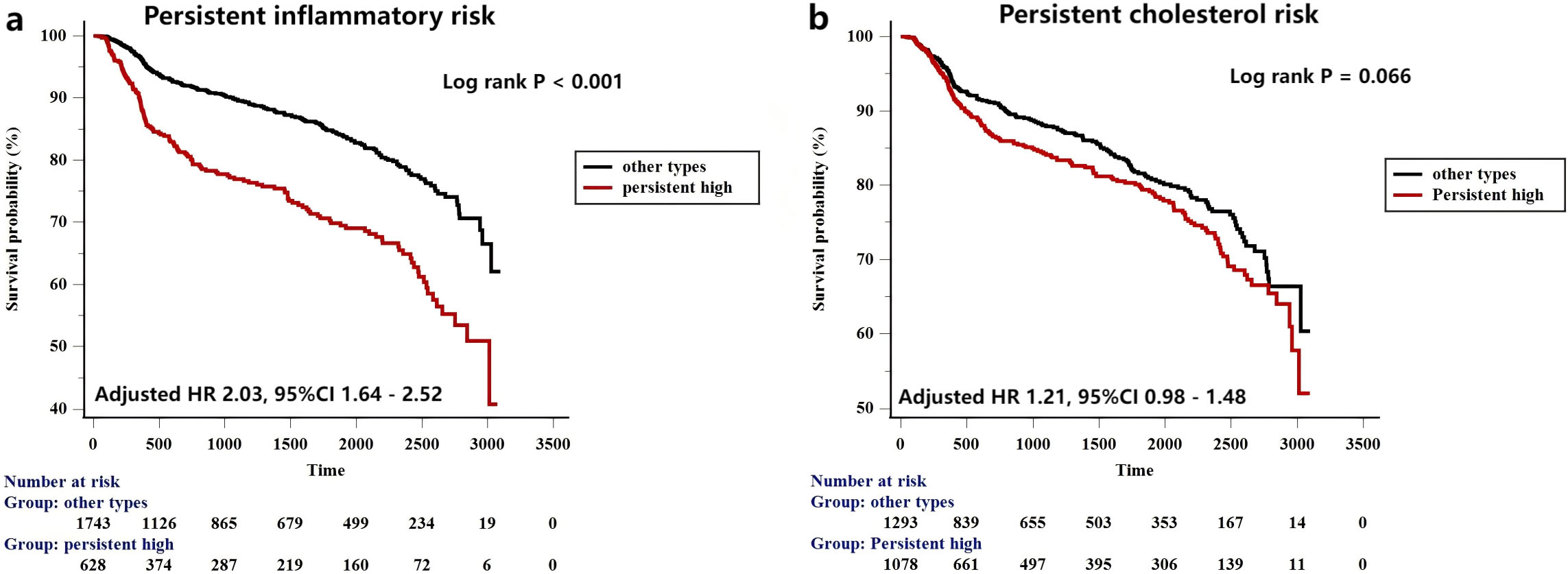

During a median follow-up of 30.4 months, 403 MACCEs occurred among 2373 patients. The high-risk LDL-C and hs-CRP cutoff values in the present study were set at 1.56 mg/L and 1.80 mmol/L, respectively, based on the results of tertile stratification and restricted cubic spline analysis. The adjusted hazard ratios (HRs) and 95% confidence intervals (CIs) of residual cholesterol risk (hs-CRP <1.56 mg/L; LDL-C ≥1.80 mmol/L), residual inflammatory risk (hs-CRP ≥1.56 mg/L; LDL-C <1.80 mmol/L), and residual cholesterol and inflammatory risk (hs-CRP ≥1.56 mg/L; LDL-C ≥1.80 mmol/L) for MACCEs were 1.26 (0.95–1.66), 2.15 (1.57–2.93), and 2.07 (1.55–2.76), respectively. Inflammatory-induced MACCEs were more likely to be associated with the increased risk of non-fatal AMI (HR: 4.48; 95% CI: 2.07–9.73; p < 0.001), while cholesterol-induced MACCEs were more likely to be associated with the increased risk of non-target vessel revascularization (TVR: HR: 1.60; 95% CI: 1.08–2.37; p = 0.019). Persistent high inflammatory risk (baseline and follow-up hs-CRP ≥1.56 mg/L) can be a major determinant of MACCEs (adjusted HR: 2.03; 95% CI: 1.64–2.52; p < 0.001), while persistent high cholesterol risk (baseline and follow-up LDL-C ≥1.80 mmol/L) was not. Serial hs-CRP measurements could produce more predictive values for MACCEs than a single measurement.

Despite statin treatment, residual cholesterol and inflammatory risks persist in post-PCI patients. The high-risk hs-CRP standard may be lower in East Asian patients than their Western counterparts, with a cutoff value of 1.56 mg/L. Inflammation and cholesterol could be major determinants for recurrent cardiovascular events, while hs-CRP seems to be a stronger predictor than LDL-C in post-PCI patients receiving statin therapy.

ChiCTR2100047090, https://www.chictr.org.cn/showproj.html?proj=127821.

Keywords

- percutaneous coronary intervention

- East Asian

- residual inflammatory risk

- residual cholesterol risk

- major adverse cardiovascular and cerebrovascular event

Due to the aging population and the increasing prevalence of cardiometabolic risk factors, cardiovascular deaths have become the leading cause of mortality in China [1]. Statin has been recognized as the cornerstone of secondary prevention due to its effectiveness in lowering the rates of recurrent myocardial infarction, stroke and cardiovascular death [2]. However, statin-treated patients, especially those with advanced atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease (ASCVD), still suffer from a relatively high incidence of recurrent events even after an early revascularization strategy, an issue commonly ascribed to the problem of ‘residual risk’ [3]. Residual cholesterol risk (RCR) and residual inflammatory risk (RIR) were both shown to be important predictors for the prognosis of ASCVD patients and therapies targeting cholesterol and inflammation delivered positive results [4, 5, 6, 7, 8]. However, there is a lack of serial monitoring of hypersensitive C-reactive protein (hs-CRP) and low-density lipoprotein cholesterol (LDL-C) values during medical follow-up. Therefore, the relative importance of inflammatory and cholesterol risk for predicting recurrent adverse clinical events after accepting statins remains elusive. In addition, the inflammatory burden, especially in East Asian patients, is generally lower than their counterparts in Western populations [9, 10, 11]. Whether the established standard (hs-CRP

The data about enrolled patients were derived from the efficacy and safety of genetic and platelet function testing for guiding antiplatelet therapy after percutaneous coronary intervention (GF-APT) registry (ChiCTR2100047090). The GF-APT was a single-center registry, which retrospectively enrolled consecutive PCI-treated patients during the hospitalization and discharged with dual antiplatelet therapy in the Fuwai Hospital between January 2016 and December 2018. The GF-APT registry was designed to explore whether the genetic-guided selection of an oral P2Y purinoceptor 12 (P2Y12) inhibitor therapy would be beneficial for patients after PCI treatment. In the GF-APT, demographics data, medical history, results of laboratory tests, angiographic features, procedural characteristics, and information on treatment outcomes were collected from electronic medical records for all enrolled patients. The primary efficacy endpoint of the study was a composite of cardiac death, myocardial infarction, and unplanned coronary revascularization following the index PCI. The major exclusion criteria of the registry were as follows: (1) expected duration of dual antiplatelet therapy

The primary endpoint of this study was the occurrence of MACCE after PCI treatment, defined as the composite of cardiovascular death, non-fatal acute myocardial infarction (AMI), non-fatal stroke and unplanned coronary revascularization. Non-fatal AMI was adjudicated using the universal definition (Fourth Universal Definition of MI). The definition of non-fatal stroke should include: (1) acute neurological deficit lasting

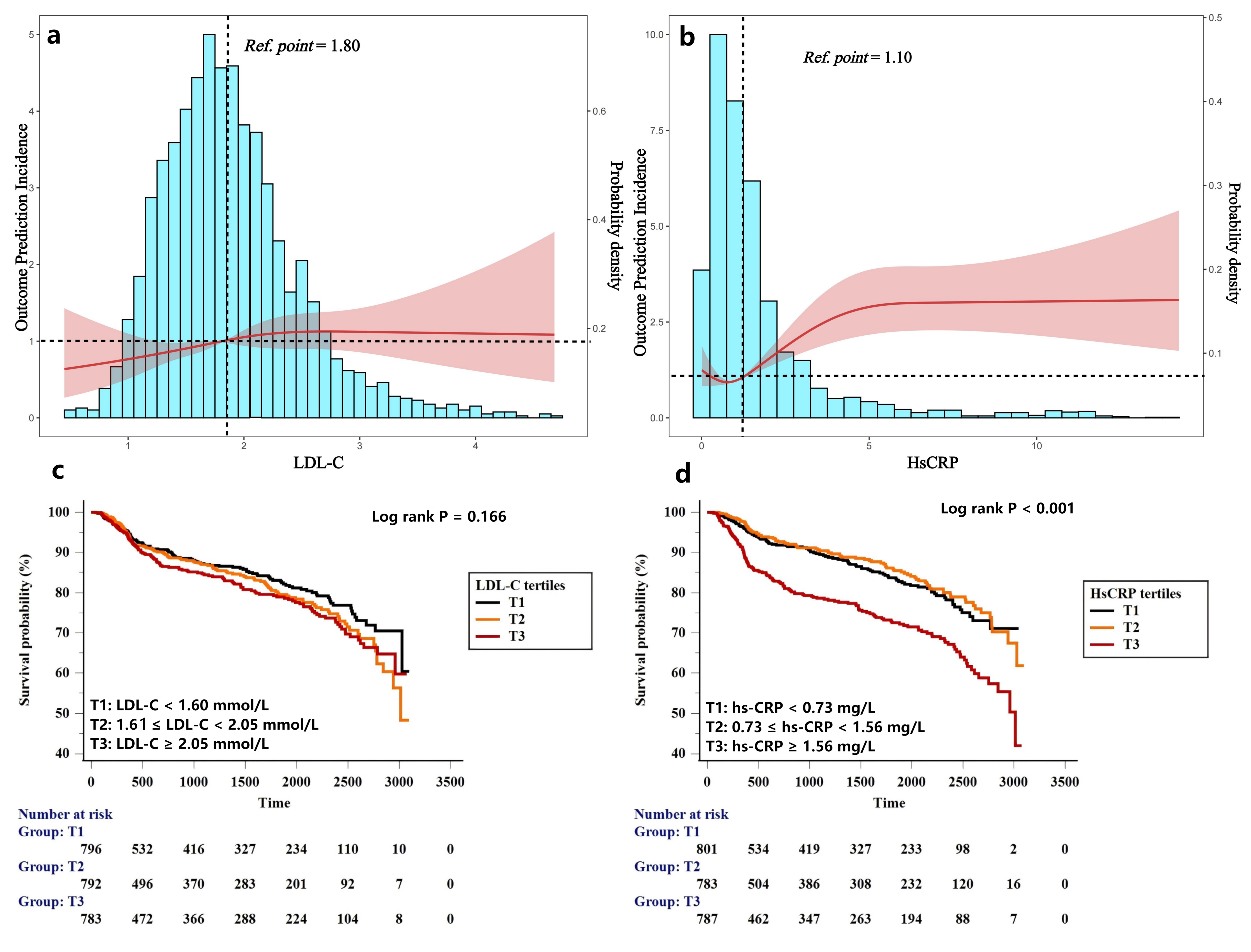

To better understand the characteristics of PCI-treated patients with residual cholesterol and inflammatory burdens, participants were categorized into four groups according to the high-risk LDL-C and hs-CRP values. To explore the high-risk cutoff values of hs-CRP and LDL-C for recurrent cardiovascular events, we performed restricted cubic spline analysis, which showed linear relationships between follow-up LDL-C and hs-CRP levels and risk of MACCE with an LDL-C

Fig. 1.

Fig. 1. Distribution of LDL-C and hs-CRP levels among PCI-treated patients and RCS plots for the association with MACCEs (a,b). Kaplan-Meier curves for MACCEs based on tertiles of LDL-C and hs-CRP levels (c,d). LDL-C, low-density lipoprotein cholesterol; hs-CRP, hypersensitive C-reactive protein; PCI, percutaneous coronary intervention; RCS, restricted cubic spline; MACCE, Major adverse cardiovascular and cerebrovascular event.

| Follow-up | MACCE events | Unadjusted model | Adjusted model | |||||

| n/N | HR | 95% CI | p value | HR | 95% CI | p value | ||

| Hs-CRP tertiles | ||||||||

| T1 (T1 | 111/801 | Ref. | Ref. | Ref. | Ref. | |||

| T2 (0.73 | 100/783 | 0.89 | 0.68–1.16 | 0.380 | 0.80 | 0.61–1.05 | 0.111 | |

| T3 (T3 | 192/789 | 1.91 | 1.51–2.42 | 1.67 | 1.30–2.14 | |||

| LDL-C tertiles | ||||||||

| T1 (T1 | 124/797 | Ref. | Ref. | Ref. | Ref. | |||

| T2 (1.61 | 135/793 | 1.17 | 0.92–1.50 | 0.203 | 1.13 | 0.88–1.46 | 0.329 | |

| T3 (T3 | 144/783 | 1.26 | 0.99–1.60 | 0.062 | 1.17 | 0.91–1.50 | 0.224 | |

Adjusted model included age, male sex, body mass index, current smoker, index presentation for PCI, medical history of previous myocardial infarction, coronary revascularization, hypertension, Type 2 diabetes mellitus, left ventricular ejection fraction, multivessel disease, ACC/AHA defined type B2/C lesions, stent length, use of ticagrelor and angiotensin blockade at discharge. p value in bold indicate the differences between groups were statistically significant. Ref, reference.

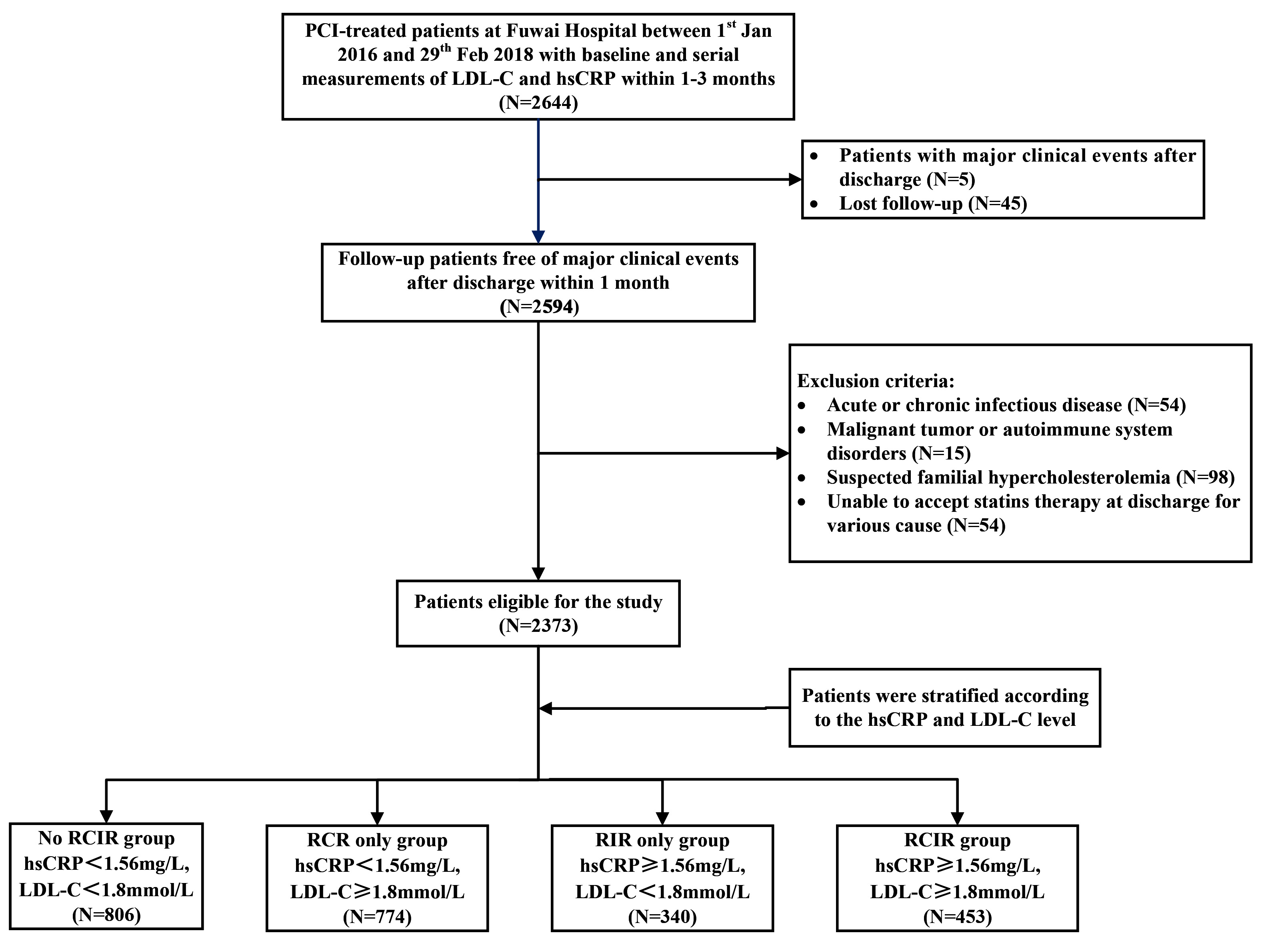

A total of 2644 consecutive participants with serial monitoring of hs-CRP and LDL-C values were recruited into study. The exclusion criteria included: (1) Failure to complete at least a 12-month follow-up (N = 45); (2) Major adverse clinical events before the latest measurement within 3 months after PCI procedure (N = 5); (3) Acute or chronic infectious diseases (N = 54); (4) Malignant tumors or autoimmune system disorders (N = 15); (5) Suspected familial hypercholesterolemia (N = 98); (6) Unable to accept statin therapy at discharge (N = 54). Finally, 2373 participants were included in the analysis. The patients were classified into 4 groups according to high-risk LDL-C and hs-CRP cutoff values: no residual cholesterol and inflammatory risk (RCIR) group: hs-CRP

Fig. 2.

Fig. 2. Flow diagram of patient selection. RCIR, residual cholesterol and inflammatory risk; RCR, residual cholesterol risk; RIR, residual inflammatory risk.

| Overall | no RCIR | RCR only | RIR only | RCIR | p value | ||

| (n = 2373) | (n = 806) | (n = 774) | (n = 340) | (n = 453) | |||

| Demographic data | |||||||

| Age (years) | 58.5 | 57.2 | 59.4 | 59.3 | 58.7 | ||

| Male sex, n (%) | 1813 (76.4%) | 650 (80.8%) | 586 (75.7%) | 255 (75.0%) | 322 (71.1%) | 0.001 | |

| Cardiovascular risk factors | |||||||

| Hypertension, n (%) | 1517 (63.9%) | 475 (58.9%) | 484 (62.5%) | 241 (70.9%) | 317 (70.0%) | ||

| Diabetes mellitus, n (%) | 855 (36.0%) | 262 (32.5%) | 268 (34.6%) | 132 (38.8%) | 193 (42.6%) | 0.002 | |

| Hyperlipidemia, n (%) | 2165 (91.2%) | 727 (90.2%) | 707 (91.3%) | 305 (89.7%) | 426 (94.0%) | 0.088 | |

| Current Smokers, n (%) | 1418 (59.8%) | 483 (60.0%) | 445 (57.5%) | 216 (63.5%) | 274 (60.5%) | 0.287 | |

| Body mass index (Kg/m2) | 25.8 | 25.6 | 25.4 | 26.2 | 26.7 | ||

| Previous medical history | |||||||

| Previous coronary revascularization, n (%) | 445 (18.8%) | 138 (17.1%) | 161 (20.8%) | 53 (15.6%) | 93 (20.5%) | 0.080 | |

| Previous myocardial infarction, n (%) | 308 (13.0%) | 105 (13.0%) | 108 (13.9%) | 33 (9.7%) | 62 (13.7%) | 0.253 | |

| Previous stroke, n (%) | 249 (10.5%) | 71 (8.8%) | 92 (11.9%) | 38 (11.1%) | 48 (10.6%) | 0.240 | |

| Index presentation | 0.007 | ||||||

| Stable angina | 749 (31.6%) | 257 (31.9%) | 263 (34.0%) | 96 (28.2%) | 133 (29.4%) | ||

| NSTE-ACS | 1188 (50.1%) | 389 (48.3%) | 395 (51.0%) | 162 (47.6%) | 242 (53.4%) | ||

| STEMI | 436 (18.3%) | 160 (19.9%) | 116 (15.0%) | 82 (24.1%) | 78 (17.2%) | ||

| Laboratory measurements | |||||||

| White blood cell count, 109/L | 7.1 | 6.5 | 6.1 | 7.3 | 7.2 | ||

| Hemoglobin, g/dL | 14.3 | 14.3 | 13.0 | 13.9 | 13.8 | ||

| Baseline hs-CRP, mg/L | 1.7 (0.9–4.2) | 1.2 (0.7–2.8) | 1.3 (0.7–2.8) | 3.2 (1.7–7.8) | 3.1 (1.8–7.6) | ||

| Follow-up hs-CRP, mg/L | 1.1 (0.6–1.97) | 0.7 (0.4–1.0) | 0.8 (0.4–1.2) | 2.6 (1.9–4.6) | 2.8 (2.0–4.6) | ||

| Creatinine, mmol/L | 80.8 | 81.9 | 81.9 | 85.0 | 80.4 | 0.002 | |

| Fasting blood glucose, mmol/L | 6.3 | 5.9 | 6.1 | 6.2 | 6.5 | ||

| HbA1c, % | 6.3 | 6.2 | 6.2 | 6.4 | 6.5 | ||

| Triglyceride, mmol/L | 1.7 | 1.3 | 1.5 | 1.5 | 1.7 | ||

| Total cholesterol, mmol/L | 4.1 | 2.9 | 3.9 | 2.9 | 4.0 | ||

| HDL-C, mmol/L | 1.1 | 1.1 | 1.2 | 1.0 | 1.1 | ||

| Baseline LDL-C, mmol/L | 2.4 | 2.1 | 2.6 | 2.2 | 2.8 | ||

| Follow-up LDL-C, mmol/L | 1.9 | 1.4 | 2.3 | 1.4 | 2.4 | ||

| LVEF, % | 61.2 | 61.5 | 61.3 | 60.2 | 60.9 | 0.040 | |

| Medication at discharge | |||||||

| Aspirin + Ticagrelor, n (%) | 521 (22.0%) | 199 (24.7%) | 123 (18.9%) | 85 (25.0%) | 114 (25.2%) | ||

| 2052 (86.5%) | 698 (86.6%) | 664 (85.8%) | 291 (85.6%) | 399 (88.1%) | 0.671 | ||

| ACEI/ARB, n (%) | 1347 (56.8%) | 447 (55.5%) | 430 (55.6%) | 204 (60.0%) | 266 (58.7%) | 0.365 | |

| Statins intensity | 0.079 | ||||||

| Low or middle-intensity, n (%) | 1886 (79.5%) | 627 (78.7%) | 632 (80.7%) | 259 (79.1%) | 368 (79.1%) | ||

| High-intensity or plus Ezetimibe, n (%) | 487 (20.5%) | 179 (21.3%) | 142 (19.3%) | 81 (20.9%) | 85 (20.9%) | ||

| Target vessel during PCI, n (%) | |||||||

| LMCA, n (%) | 131 (5.5%) | 42 (5.2%) | 41 (5.3%) | 21 (6.2%) | 27 (6.0%) | 0.880 | |

| LAD, n (%) | 1392 (58.7%) | 484 (60.0%) | 450 (58.1%) | 205 (60.3%) | 253 (55.8%) | 0.461 | |

| LCX, n (%) | 599 (25.2%) | 184 (22.8%) | 213 (27.5%) | 76 (22.3%) | 126 (27.8%) | 0.052 | |

| RCA, n (%) | 840 (36.4%) | 291 (36.1%) | 259 (33.5%) | 124 (36.5%) | 166 (36.6%) | 0.589 | |

| Others, n (%) | 8 (0.3%) | 0 (0.0%) | 5 (0.6%) | 2 (0.6%) | 1 (0.2%) | 0.062 | |

| Multivessel disease, n (%) | 1703 (71.8%) | 550 (68.2%) | 559 (72.2%) | 253 (74.4%) | 341 (75.3%) | 0.030 | |

| Stent length, mm | 36.3 | 36.4 | 36.4 | 36.9 | 35.6 | 0.900 | |

| AHA/ACC lesion: type B2/C, n (%) | 1726 (72.7%) | 589 (73.1%) | 567 (73.3%) | 242 (71.2%) | 328 (72.4%) | 0.898 | |

| Major adverse clinical events, n (%) | 403 (17.0%) | 94 (11.7%) | 117 (15.1%) | 83 (24.4%) | 110 (24.3%) | ||

| Cardiovascular death, n (%) | 4 (0.2%) | 0 (0.0%) | 0 (0.0%) | 3 (0.9%) | 1 (0.2%) | 0.004 | |

| Non-fatal AMI, n (%) | 73 (3.1%) | 11 (1.4%) | 17 (2.2%) | 19 (5.6%) | 26 (5.7%) | ||

| Non-fatal Stroke, n (%) | 10 (4.3%) | 1 (0.1%) | 2 (0.3%) | 1 (0.3%) | 6 (1.3%) | 0.021 | |

| Target vessel revascularization, n (%) | 152 (6.4%) | 44 (5.5%) | 39 (5.0%) | 26 (7.6%) | 43 (9.5%) | ||

| Non-target vessel revascularization, n (%) | 206 (8.7%) | 44 (5.5%) | 66 (8.5%) | 46 (13.5%) | 50 (11.0%) | ||

Data are expressed as the mean

According to the high-risk hs-CRP and LDL-C cutoff value, the cohort were classified into no RCIR group (hs-CRP <1.56 mg/L and LDL-C <1.80 mmol/L, N = 806, 38.7%), RCR only group (hs-CRP <1.56 mg/L and LDL-C ≥1.80 mmol/L, N = 774, 37.2%), RIR only group (hs-CRP ≥1.56 mg/L and LDL-C <1.80 mmol/L, N = 340, 9.9%) and RCIR group (hs-CRP ≥1.56 mg/L and LDL-C ≥1.80 mmol/L, N = 453, 14.2%). Table 2 showed that compared with those with no RCIR, patients with residual risks had more rates of hypertension, diabetes mellitus, and higher body mass index (BMI) values. The prevalence of MACCE was higher in RCR only (15.1%), RIR only (24.1%) and RCIR (24.3%) group than in the no RCIR group (p

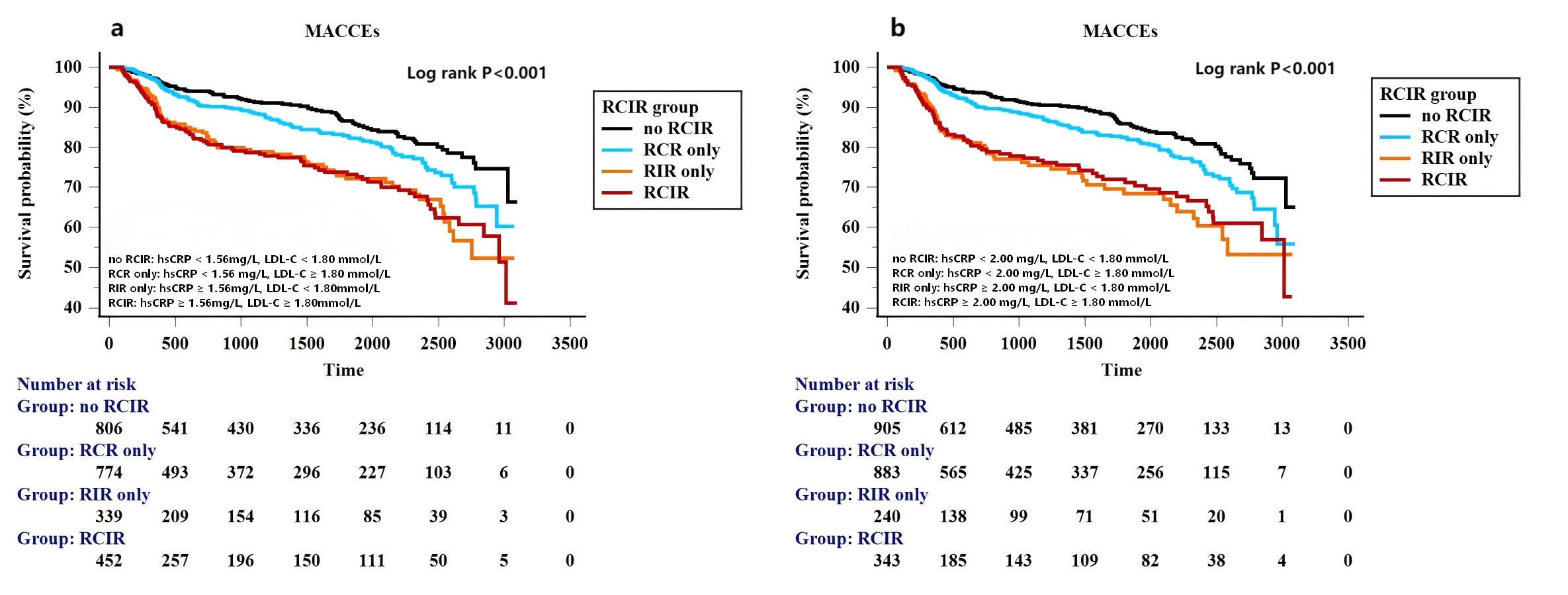

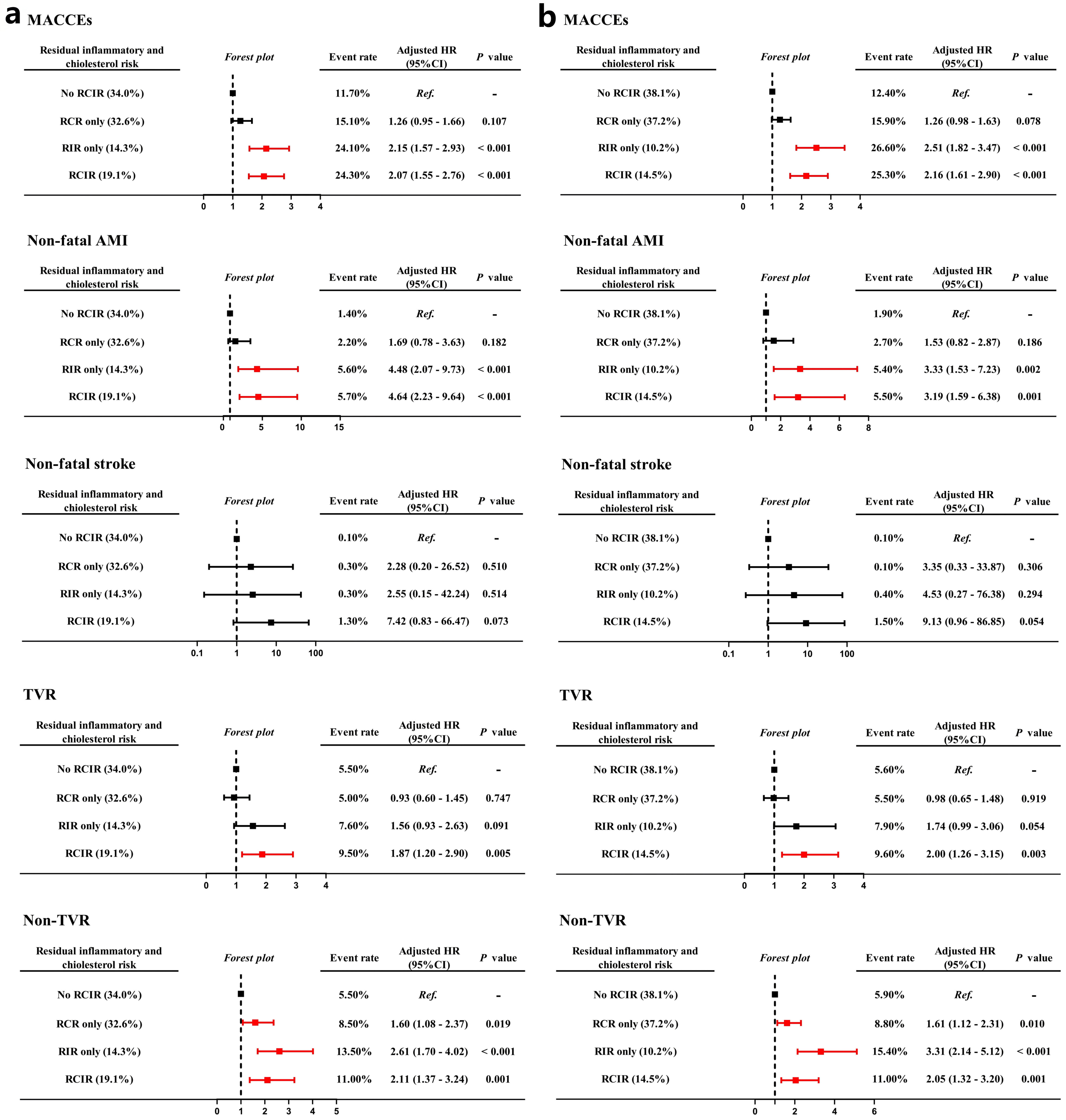

During the follow-up period, there were significant differences in the risk of MACCE across the residual cholesterol or inflammatory risk group, irrespective of whether the hs-CRP threshold value was 1.56 mg/L or 2 mg/L (Fig. 3a,b). Table 3 shows that compared with the no RCIR reference group, the adjusted HR (95% CI) of RCR only, RIR only and the RCIR group for MACCE were 1.26 (0.95–1.66), 2.15 (1.57–2.93) and 2.07 (1.55–2.76) after adjusting for the following confounders: age, male sex, BMI, current smoker, index presentation for PCI, medical history of previous myocardial infarction, coronary revascularization, hypertension and Type 2 diabetes mellitus, the presence of multivessel disease, ACC/AHA defined type B2/C lesions, total stent length, use of ticagrelor and angiotensin blockade at discharge and left ventricular ejection fraction (LVEF) if hs-CRP 1.56 mg/L was used as the high-risk threshold value. Adjusted HR (95% CI) of RCR only, RIR only and RCIR group for MACCE were 1.26 (0.98–1.63), 2.51 (1.82–3.47) and 2.16 (1.61–2.90) if the high-risk hs-CRP cutoff value was 2 mg/L. We further evaluated and compared prognostic implications of residual risks for the incidence of non-fatal AMI, non-fatal stroke, unplanned coronary revascularization according to different high-risk hs-CRP standards. Fig. 4a shows that inflammatory-induced MACCE were more likely to be associated with increased risks of non-fatal AMI (HR 4.48, 95% CI 2.07–9.73, p

Fig. 3.

Fig. 3. Kaplan-Meier curves for MACCEs based on different standards (East Asian standard (a), Western standard (b)) for residual cholesterol and inflammatory risk categories.

Fig. 4.

Fig. 4. Forest plots for risks of MACCEs, non-fatal AMI, non-fatal stroke, TVR and non-TVR based on different hs-CRP standards (East Asian standard (a), Western standard (b)) for residual inflammatory and cholesterol risk models. TVR, target vessel revascularization.

| Unadjusted model | Adjusted model | ||||||

| HR | 95% CI | p value | HR | 95% CI | p value | ||

| Demographic data | |||||||

| Age | 0.99 | 0.98–1.01 | 0.312 | 0.99 | 0.98–1.00 | 0.136 | |

| Male sex | 1.12 | 0.88–1.43 | 0.358 | 0.94 | 0.68–1.31 | 0.729 | |

| Body mass index | 1.05 | 1.02–1.08 | 1.02 | 0.99–1.05 | 0.243 | ||

| Current smoker | 1.2 | 0.98–1.47 | 0.078 | 1.10 | 0.84–1.43 | 0.483 | |

| Index presentation | 0.969 | 0.993 | |||||

| Stable angina | Ref. | Ref. | Ref. | Ref. | |||

| NSTE-ACS | 0.99 | 0.79–1.23 | 0.916 | 0.99 | 0.79–1.25 | 0.969 | |

| STEMI | 0.96 | 0.72–1.29 | 0.804 | 0.98 | 0.70–1.38 | 0.904 | |

| Medical history | |||||||

| Pervious myocardial infarction | 1.62 | 1.26–2.07 | 1.34 | 0.99–1.80 | 0.056 | ||

| Previous coronary revascularization | 1.85 | 1.49–2.29 | 1.62 | 1.26–2.08 | |||

| Hypertension | 1.53 | 1.23–1.90 | 1.29 | 1.00–1.66 | 0.046 | ||

| Type 2 diabetes mellitus | 1.31 | 1.08–1.60 | 0.007 | 1.08 | 0.88–1.33 | 0.471 | |

| LVEF, % | 0.99 | 0.98–1.01 | 0.907 | 1.01 | 0.99–1.03 | 0.235 | |

| PCI procedural characteristics | |||||||

| Multivessel disease | 2.14 | 1.64–2.80 | 2.09 | 1.59–2.75 | |||

| ACC/AHA lesions: type B2 or C | 1.09 | 0.95–1.36 | 0.346 | 0.94 | 0.74–1.19 | 0.590 | |

| Stent length | 1.00 | 0.99–1.01 | 0.124 | 1.00 | 1.00–1.01 | 0.065 | |

| Medication at discharge | |||||||

| Use of ticagrelor | 1.29 | 1.03–1.60 | 0.026 | 1.18 | 0.92–1.50 | 0.194 | |

| Use of angiotensin blockade | 1.40 | 1.14–1.72 | 0.001 | 1.12 | 0.89–1.42 | 0.329 | |

| RCIR phenotype (hs-CRP 1.56 mg/L, LDL-C 1.8 mmol/L) | |||||||

| No RCIR | Ref. | Ref. | |||||

| RCR only | 1.36 | 1.04–1.79 | 0.026 | 1.26 | 0.95–1.66 | 0.107 | |

| RIR only | 2.32 | 1.72–3.12 | 2.15 | 1.57–2.93 | |||

| RCIR | 2.36 | 1.79–3.11 | 2.07 | 1.55–2.76 | |||

| RCIR phenotype (hs-CRP 2 mg/L, LDL-C 1.8 mmol/L) | |||||||

| No RCIR | Ref. | Ref. | |||||

| RCR only | 1.35 | 1.06–1.73 | 0.017 | 1.26 | 0.98–1.63 | 0.078 | |

| RIR only | 2.62 | 1.93–3.57 | 2.51 | 1.82–3.47 | |||

| RCIR | 2.4 | 1.81–3.18 | 2.16 | 1.61–2.90 | |||

Adjusted model included age, male sex, body mass index, current smoker, index presentation for PCI, medical history of previous myocardial infarction, coronary revascularization, hypertension, Type 2 diabetes mellitus, left ventricular ejection fraction, multivessel disease, ACC/AHA defined type B2/C lesions, stent length, use of ticagrelor and angiotensin blockade at discharge. p value in bold indicate the differences between groups were statistically significant.

To further evaluate the impact of persistent residual risks on prognosis, we also evaluated the prognostic implications of persistent residual risk in the current study (Fig. 5). Persistent high inflammatory risk group was defined as patients with baseline and follow-up hs-CRP

Fig. 5.

Fig. 5. Kaplan-Meier curves for MACCEs based on the persistent inflammatory (a) and cholesterol risk (b) model.

| MACCE events | Unadjusted model | Adjusted model | ||||||

| n/N | HR | 95% CI | p value | HR | 95% CI | p value | ||

| Baseline inflammatory risk | ||||||||

| Hs-CRP | 158/1108 | Ref. | Ref. | Ref. | Ref. | |||

| Hs-CRP | 245/1256 | 1.41 | 1.15–1.72 | 0.001 | 1.40 | 1.13–1.74 | 0.002 | |

| Follow-up inflammatory risk | ||||||||

| Hs-CRP | 211/1580 | Ref. | Ref. | Ref. | Ref. | |||

| Hs-CRP | 192/793 | 2.00 | 1.64–2.43 | 1.84 | 1.49–2.27 | |||

| Persistent inflammatory risk | ||||||||

| Other types | 234/1743 | Ref. | Ref. | Ref. | Ref. | |||

| Persistent high | 169/630 | 2.16 | 1.77–2.63 | 2.03 | 1.64–2.52 | |||

Adjusted model included age, male sex, body mass index, current smoker, index presentation for PCI, medical history of previous myocardial infarction, coronary revascularization, hypertension, Type 2 diabetes mellitus, left ventricular ejection fraction, multivessel disease, ACC/AHA defined type B2/C lesions, stent length, use of ticagrelor and angiotensin blockade at discharge. p value in bold indicate the differences between groups were statistically significant.

Patients were categorized into 4 group according to baseline and follow-up hs-CRP and LDL-C values. Other types included Persistent low, Attenuated and Fortified inflammatory or cholesterol risk group.

The main findings of this study were as follows: (1) Almost half of the PCI-treated patients presented with high cholesterol burden and one-third of PCI-treated patients presented with high inflammatory burden despite lipid-lowering therapies. (2) The inflammatory criteria for high-risk hs-CRP standards may be lower in East Asian patients than their Western counterparts, with a threshold value of 1.56 mg/L in the present study. (3) Cholesterol and inflammation could still be major determinants for recurrent cardiovascular events while hs-CRP seemed to be a stronger predictor than LDL-C in post-PCI patients receiving statins. (4) Serial measurements of hs-CRP levels appear to produce more prognostic values than a single measurement.

Statins remain the cornerstone therapy for the secondary prevention of ASCVD patients due to the pleiotropic effects in lowering cholesterol levels, stabilizing plaques, improving endothelial function and alleviating vascular inflammation [20]. Previous RCTs have shown the effectiveness of statin in reducing future cardiovascular events [2]. However, for advanced ASCVD patients, increased risks for recurrent cardiovascular events can still occur during long-term follow-up despite an early coronary revascularization strategy and guideline-recommended medical therapy, an issue commonly ascribed to the problem of ‘residual risk’ [3, 21, 22]. Cholesterol undoubtedly is a major residual risk factor and was defined as an unachieved LDL-C level goal despite lipid-lowering therapy. While the precise goal for LDL-C remained unknown, current clinical practice guidelines provide Class I recommendations for LDL-C targets of less than 1.80 mmol/L (70 mg/dL) in most patients with atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease [12]. In the present study, the enrolled participants were all post-PCI patients, most of whom received moderate intensity statins (79.5%) at discharge. However, we found that high cholesterol burden could still be present in almost half of the enrolled patients (51.4%) during follow-up, indicating the importance of intensified lipid-lowering therapies in current practice. The concept of ‘the lower, the better’ for LDL-C levels has brought intensified lipid-lowering therapy into clinical practice. Aggressive lipid-lowering therapies have produced positive results and further reduced adverse event rates by 2–15% [5, 23, 24]. Although the predictive value of high cholesterol risk measured by LDL-C for MACCE was mediated by statin treatment in the present study, the beneficial effect of intensified lipid-lowering therapies could not be simply explained by achieving the LDL-C goal. An Asian-specific cohort study focusing on post-PCI patients found that patients receiving high-intensity statins had a lower adjusted risk of major cardiovascular outcomes irrespective of LDL-C target attainment [25]. In addition, we found that RCR was significantly associated with the risk of non-TVR in the present study. The lipid accumulation in non-target vessels that were not severe enough to require intervention during the PCI procedure could be the main cause of recurrent cardiovascular events during the long-term follow-up [26, 27]. Intravascular imaging studies have shown that the benefit of intensified lipid-lowering therapies lies in slowing the plaque progression and lowering the rates of unplanned coronary revascularization [28, 29]. Considering the impact of cholesterol on prognosis and a relatively low percentage of statin-treated patients with achieved LDL-C goals in the current study, intensified lipid-lowering therapy remains necessary in post-PCI patients.

In the past decades, advancement in vascular biology has reshaped our understanding of atherosclerosis. It has shifted from the disease of lipid accumulation in arterial walls to the multifactorial and inflammatory-driven disease. In this novel perspective, inflammation and hyperlipidemia contributed similarly to the initiation and progression of atherosclerosis [30]. The concept of ‘dual targets of inflammatory and cholesterol risk’ has been confirmed in the IMPROVE-IT trial [4]. Increasing evidence from large clinical trials focusing on inflammation among high-risk ASCVD individuals is now emerging. In the Canakinumab Anti-inflammatory Thrombosis Outcomes Study trial (CANTOS trial), participants with a history of myocardial infarction and hs-CRP

High inflammatory risk continues to persist after PCI treatment, ranging from 18.3% in East Asian populations to 38.0% in Western populations [38, 39]. In the present study, the rate of PCI-treated patients with persistent high inflammatory burden was 18.0% according to the Western standard, which is consistent with previous findings in East Asian populations, showing that almost one-fourth of the PCI-treated populations were under persistent high inflammatory burden. Furthermore, the current study also showed that continuous monitoring of inflammatory indicator could be more valuable than a single measurement in predicting prognosis. The persistent high inflammatory risk was a reliable predictor for prognosis even in patients with baseline LDL-C

Several limitations should be acknowledged in our study. First, this was a single-center observational retrospective cohort study in which exclusively included post-PCI patients with serial measurements of hs-CRP and LDL-C values, which may unavoidably introduce selection bias in two aspects: (1) Healthcare access disparity: Patients with multiple measurements likely had better care continuity and socioeconomic status, potentially limiting generalizability to disadvantaged populations. (2) Survivorship test: High-risk individuals may die prior to the second measurement, possibly attenuating true risk estimates. Second, the sample size was relatively small, so the exact cutoff value of hs-CRP still needs to be further confirmed in a larger sample size study; Third, the cardiovascular death and stroke rates were relatively low during the follow-up, which may limit the statistical analysis and make it difficult to find an association with the residual risk. Fourth, unmeasured confounders persist despite multivariate Cox regression adjustment; Finally, the intensity and duration of lipid-lowering strategies during the follow-up could not be obtained. Therefore, whether the change in intensity had an impact on the prognostic value of residual risk still needs to be further explored.

PCI-treated patients receiving statins still presented with a relatively high residual cholesterol and inflammatory burden. The high-risk hs-CRP standard may be lower in East Asian patients than their Western counterparts, with a cutoff value of 1.56 mg/L in present study. Inflammation and cholesterol could be major determinants for recurrent cardiovascular events while hs-CRP seemed to be a stronger predictor than LDL-C in PCI-treated patients after statin treatment.

Lower hs-CRP cutoff value for East Asian Population: Clinical evidence from Asian or Western registries have substantiated the usefulness of measuring RIR (hs-CRP

Stressing the importance of managing residual inflammatory risk: In the present study, all patients are treated with statin therapy and, thus, the relative importance of inflammation and hyperlipidemia as determinants of residual cardiovascular risk might have shifted. Residual inflammatory risk in the present study seemed to result in more predictive value for future cardiovascular events than the residual cholesterol risk, indicate inhibiting inflammation may provide greater prognostic benefit than further LDL-C reduction in patients already receiving statin therapy.

Hs-CRP, Hypersensitive C-reactive protein; LDL-C, Low-density lipoprotein cholesterol; PCI, Percutaneous coronary intervention; MACCE, Major adverse cardiovascular and cerebrovascular event; AMI, Acute myocardial infarction; TVR, Target vessel revascularization; HR, Hazard ratio; CI, Confidence interval; ASCAD, Advanced atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease; RCR, Residual cholesterol risk; RIR, Residual inflammatory risk; RCIR, Residual cholesterol and inflammatory risk; GF-APT registry, Genetic and platelet function testing for guiding antiplatelet therapy after percutaneous coronary intervention registry; TC, Total cholesterol; TG, Triglyceride; HDL-C, High-density lipoprotein cholesterol; ACS, Acute coronary syndrome; NSTE-ACS, Non-ST-segment elevation acute coronary syndrome; STEMI, ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction; HbA1c, Hemoglobin A1c; BMI, Body mass index; LVEF, Left ventricular ejection fraction; ACEI/ARB, Angiotensin converting enzyme inhibitor/angiotensin receptor blocker; LMCA, Left main coronary artery; LAD, Left anterior descending coronary artery; LCX, Left circumflex coronary artery; RCA, Right coronary artery; CANTOS trial, Canakinumab Anti-inflammatory Thrombosis Outcomes Study trial; COLCOT trial, Colchicine Cardiovascular Outcomes Trial; LoDoCo2 trial, Low-Dose Colchicine 2 trial; IL-6, Interleukin-6; NLRP3, NOD-like receptor family, pyrin domain containing 3.

The datasets and materials mentioned above are available from the authors upon reasonable request.

AG concepted and designed the research study. AG and TTG drafted the manuscript and were major contributors in the collection, analysis and interpretation of data. ZQY, HQ and RLG were major contributors in the acquisition and interpretation of data and contributed to the revision of manuscript critically for important intellectual content. All authors contributed to editorial changes in the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript. All authors have participated sufficiently in the work and agreed to be accountable for all aspects of the work.

The study was carried out in accordance with the guidelines of the Declaration of Helsinki and approved by the ethics committee of Fuwai Hospital (No. 2021-1063). The need to obtain informed consent from the participants was waived by the Ethics Committee.

Not applicable.

This work was supported by the Major science and Technology Special Plan project of Yunnan Province (202302AA310045).

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Supplementary material associated with this article can be found, in the online version, at https://doi.org/10.31083/RCM36438.

References

Publisher’s Note: IMR Press stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.