1 Cardiology Department, Hospital General Universitario Gregorio Marañón, Instituto de Investigación Sanitaria Gregorio Marañón, CIBERCV, 28007 Madrid, Spain

2 School of Biomedical and Health Sciences, Universidad Europea, 28670 Madrid, Spain

3 School of Medicine, Universidad Complutense, 28007 Madrid, Spain

Abstract

Stress cardiomyopathy/Takotsubo syndrome (TTS) is a transient cardiac condition characterized by sudden and reversible left ventricular dysfunction, typically triggered by emotional or physical stress. The international TTS (InterTAK) score predicts the probability of suffering from TTS. However, the diagnostic algorithm includes three mutually exclusive diagnoses: acute coronary syndrome (ACS), TTS, and acute infectious myocarditis. Thus, we propose to include the conditions in which TTS is associated with ACS or myocarditis. While TTS is commonly associated with non-ischemic stressors, recent evidence has indicated that TTS can be found in patients with ACS. Nonetheless, in some cases, ACS may trigger rather than exclude TTS. Additionally, TTS could also prompt plaque ruptures in coronary arteries. Meanwhile, infections and conditions that cause myocarditis can also produce physical stress that may trigger TTS. Furthermore, TTS has been reported after confirmed viral myocarditis. This opinion article explores the intricate relationships between (i) TTS and ACS, and (ii) TTS and myocarditis, delving into the related pathophysiologies and diagnostic challenges. However, further research is required to elucidate the mechanisms that link TTS with these conditions.

Keywords

- stress cardiomyopathy

- Takotsubo syndrome

- acute coronary syndrome

- trigger

Stress cardiomyopathy/Takotsubo syndrome (TTS) was first identified in Japan in the early 1990s [1], named after the Japanese term for an octopus trap due to the distinctive shape of the left ventricle during systole observed in affected patients. TTS is an acute reversible form of myocardial dysfunction. Typical TTS is triggered by physical or emotional stressful events and is characterized by a peculiar left ventricular apical hypokinesia/akinesia abnormalities extended beyond a single epicardial coronary artery distribution, basal hyperkinesia (“apical ballooning”) and absence of a “culprit” coronary artery obstruction [2]. Atypical presentations include absence of a stressful trigger, wall motion abnormalities in other areas of the left ventricle (including midventricular and basal regions or focal segments), and presence of coronary artery disease.

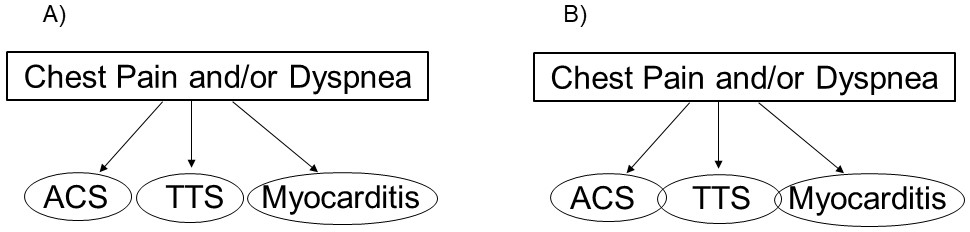

The International Takotsubo (InterTAK) diagnostic algorithm comprises seven parameters (female sex, emotional trigger, physical trigger, absence of ST-segment depression [except in lead aVR], psychiatric disorders, neurologic disorders, and QT prolongation) to obtain a predicted probability of suffering from TTS [3]. However, the current diagnostic algorithm includes three mutually exclusive diagnoses: acute coronary syndrome (ACS), TTS, and acute infectious myocarditis. We propose to include conditions in which TTS is associated with ACS or myocarditis (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1.

Fig. 1. Diagnostic algorithms. (A) Current international takotsubo (InterTAK) diagnostic algorithm that includes three mutually exclusive diagnoses: acute coronary syndrome (ACS), takotsubo syndrome (TTS), and acute infectious myocarditis. (B) Our proposal to include conditions in which TTS is associated with ACS or myocarditis.

The first Mayo Clinic TTS diagnostic criteria from 2004 required the exclusion of obstructive coronary artery disease [4]. However, quickly it became clear that coronary artery disease frequently coexists with TTS [5]. Sharkey et al. [6] encountered 9 patients with features of both ACS and TTS among a population of 3506 consecutive ACS patients (0.3%) and 146 TTS patients (6.1%). Napp et al. [7] only found 3 patients with ACS among a total of 1016 TTS patients (0.3%), although the rate of obstructive coronary artery disease was much higher (23%) and 47 patients (4.6%) underwent percutaneous coronary intervention.

It is well-known that transient episodes of coronary ischemia may induce reversible left ventricular dysfunction. In fact, post-ischemic myocardial stunning is common after ACS/reperfusion and after other types of transitory myocardial ischemia (percutaneous coronary angioplasty, cardiac surgery, and ischemia induced by exercise, dobutamine or dipyridamole) [8]. In spite of being a strong physical and emotional stress factor, ACS is frequently regarded as an exclusion criterion for TTS. However, recent evidence shows that ACS and TTS may coexist and a growing body of case reports and case series show that TTS and ACS can occur concomitantly [9, 10, 11, 12, 13, 14, 15, 16, 17, 18, 19, 20, 21, 22, 23, 24, 25, 26, 27, 28, 29, 30, 31, 32, 33, 34, 35, 36, 37, 38, 39]. A myriad of emotional and physical stress factors have been reported to precipitate TTS. SCA is a major physical stress factor and frequently produces significant emotional impact [30]. It seems reasonable to assume that the high stress associated with ACS can also trigger TS. However, although ACS may trigger TTS, the opposite could also happen, as it has been hypothesized that the disrupted systolic motion of the left ventricular myocardium might promote the rupture of coronary artery plaques and coronary thrombotic occlusion [31]. This means that ACS may be the initial event, subsequently triggering TTS. Alternatively, TTS could precipitate ACS through plaque rupture mediated by this sudden change in left ventricular geometry and regional strain, but also due to the sympathetic discharge that causes vasoconstriction [7].

Differentiating the two entities or recognizing their concomitant occurrence might not straightforward, as there is considerable overlap in pathophysiological, clinical, and diagnostic characteristics. Moreover, emotional and physical triggering factors can occur both in TTS and in ACS, and, as we described above, one may precipitate the other. Perfusion-contraction mismatch might be the key to detect this double diagnosis [32], based on the fact that in patients with TTS, regional ventricular dysfunction typically does not adhere to the coronary anatomy, often extending beyond the boundaries of the supply region of the culprit artery. Moreover, cardiac magnetic resonance imaging frequently shows findings suggestive of myocardial infarction after TTS [33, 34] suggesting that the delayed enhancement seen in some patients may be a sign of a myocardial infarction that triggered TTS. We recognize that concomitant occurrence is unusual and that some authors prefer not to diagnose TTS in patients with ACS due to the fear of confusing clinicians and patients and the lack of therapeutic implications of the double diagnosis [35]. However, as Aristotle defined “to say of what is that it is, and of what is not that it is not, is true”.

Infections and conditions that cause myocarditis can also produce physical stress that may trigger TTS and different authors have suggested myocarditis is common in TTS [36, 37, 38, 39, 40, 41]. Myocarditis is due to an inflammatory injury to the myocardium, typically due to viral infections, immune-mediated mechanisms, or toxins. TTS has been reported after confirmed viral myocarditis [42, 43, 44, 45], durvalumab-induced myocarditis [46], immune checkpoint inhibitor myocarditis [47] and lupus myopericarditis [48].

In addition, typical myocarditis magnetic resonance imaging results have been reported in patients with TTS [49, 50, 51, 52, 53, 54, 55, 56, 57]. Although magnetic resonance imaging in patients with TTS usually show myocardial edema without significant late gadolinium enhancement some patients also have the patchy or subepicardial late gadolinium enhancement suggestive of myocarditis. Moreover, endomyocardial biopsy, while not routinely performed in patients TTS, is sometimes done, and some biopsy results have shown inflammatory infiltrates typical of myocarditis [58, 59] instead of myocyte damage without inflammation (seen in pure TTS).

Thus, TC and myocarditis do not need to be mutually exclusive and three possibilities exist: (i) primary myocarditis triggering TTS, where inflammation and infection could lead to a catecholamine surge, a pathophysiology somewhat similar to pheochromocytoma [60, 61]; (ii) primary TTS with secondary inflammation, as TTS-induced myocardial injury may provoke localized inflammation, resulting in a myocarditis-like pattern [62, 63, 64, 65]; (iii) a common underlying trigger, where a shared external trigger (e.g., viral infection or systemic inflammation) causes simultaneous myocarditis and the physical stress that originates TTS [66, 67, 68, 69, 70]. Advances in cardiac magnetic resonance imaging and biopsy techniques have begun to reveal this underrecognized overlap. Greater awareness of the possibility of coexistence can lead to more accurate diagnosis, more personalized treatment, and better outcomes for patients presenting with this mixed acute myocardial dysfunction.

TTS has traditionally been categorized as a distinct entity, often mutually exclusive from ACS and myocarditis. However, this rigid compartmentalization is increasingly challenged by clinical and imaging evidence showing significant overlap among these conditions. Current diagnostic algorithms frequently present TTS, ACS, and acute infectious myocarditis as separate paths, with criteria designed to rule out one in favor of the others. While useful for clarity, this approach oversimplifies complex clinical scenarios. In real-world settings, there are documented cases of co-occurrence of TTS triggered by ACS and myocarditis. By forcing clinicians to choose between ACS, TTS, and myocarditis, the diagnostic model may fail to capture the dynamic, multifactorial nature of myocardial injury in certain patients. This approach could have important implications for management, prognosis, and research. Recognizing and documenting the possibility of overlap in some patients could provide several benefits, allowing clinicians to better understand the mechanism of myocardial dysfunction in ambiguous presentations, changing treatment plans, and enabling more nuanced data collection and better understanding of pathophysiology. The risks of this more inclusive approach include overdiagnosis and an increase in resource utilization but the net clinical value of moving away from rigid diagnostic silos appears favorable. In some patients, especially those with atypical features or incomplete diagnostic clarity, it is reasonable to consider that TTS might coexist with ACS or myocarditis. The diagnostic algorithm must evolve to reflect the overlapping spectrum of myocardial injury syndromes, ensuring that care is guided by the complexity of individual presentations rather than artificial boundaries. For instance, in patients with ACS and electrocardiograms with QT prolongation [71] or high N-terminal pro–B-type natriuretic peptide/troponin ratio [72], coexistence with TS should be evaluated. In this regard, cardiac magnetic resonance imaging might be particularly useful to assess that possibility [73]. Magnetic resonance might also suggest the concurrence of TS in patients with myocarditis [63].

Most studies analyzed in this manuscript are case reports, case series or are limited by small sample sizes, and lack of methodological standardization. These limitations highlight the need for larger, multicenter prospective studies to clarify the frequence and clinical implications of TS in patients with ACS and myocarditis.

TTS might be seen in patients with ACS and in patients with acute myocarditis. Further research is needed to elucidate the pathophysiological mechanisms that explain these associations. Meanwhile we need to recognize that, in some uncommon cases, ACS may trigger rather than exclude TTS. In addition, TTS could prompt plaque ruptures in coronary arteries. TTS can also be associated with myocarditis. We propose that the diagnostic algorithm should include conditions in which TTS is seen together with ACS or myocarditis.

MMS is the sole author of the article and assumes full responsibility for its content and was the one to perform all article-related activities: conception and design, acquisition of data from previous publications, analysis and interpretation of data, writing the manuscript. MMS is to be accountable for all aspects of the work. No other person was involved in this manuscript.

Not applicable.

Not applicable.

This research received no external funding.

The author declares no conflict of interest. Manuel Martínez-Sellés is serving as one of the Editorial Board Members and Guest Editors of this journal. We declare that Manuel Martínez-Sellés had no involvement in the peer review of this article and has no access to information regarding its peer review. Full responsibility for the editorial process for this article was delegated to Yuanhui Liu.

References

Publisher’s Note: IMR Press stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.