1 Colleague of Clinical Medicine, Jining Medical University, 272067 Jining, Shandong, China

2 Department of Cardiology, Shandong Key Laboratory for Diagnosis and Treatment of Cardiovascular Diseases, Jining Key Laboratory of Precise Therapeutic Research of Coronary Intervention, Affiliated Hospital of Jining Medical University, 272029 Jining, Shandong, China

Abstract

Coronary heart disease (CHD) is associated with increased morbidity and mortality. Acute cardiovascular events frequently occur in patients with coronary artery stenoses exceeding 70%. Although coronary revascularization can significantly improve ischemic symptoms, the inflection point for reducing mortality from CHD has yet to be reached. Therefore, the prevention and treatment of mild-to-moderate coronary artery stenosis should be given significant attention to more effectively reduce the incidence and mortality of acute events from CHD. Subsequently, a stenosis of less than 70% is used to characterize the incidence of mild to moderate coronary artery stenosis. While acute cardiovascular events caused by soft plaque and plaque rupture may not have a significant impact on hemodynamics, these events are detrimental and result in increased mortality. This review summarizes the methods available for detecting mild-to-moderate coronary artery stenoses, assessing risk, and understanding the mechanisms underlying adverse events. Moreover, this review proposes intervention strategies for preventing and treating mild to moderate coronary stenosis.

Keywords

- coronary artery disease

- mild-to-moderate coronary artery stenosis

- risk evaluation

- intervention approaches

The prevalence of coronary heart disease (CHD) in clinical practice is progressively increasing over time. It has emerged as one of the most significant threats to human health and mortality [1, 2]. The acute events of CHD are characterized by a stenosis of the vascular lumen and are commonly observed in patients with coronary artery stenoses exceeding 70%, necessitating interventions such as coronary stenting or coronary artery bypass graft surgery. Although these treatments significantly improve symptoms, they may not always reduce mortality rates for CHD. Therefore, emphasis should be placed on the prevention and treatment for CHD to reduce the incidence of acute events and mortality. This review focuses on patients with mild-to-moderate coronary artery stenoses, specifically those with coronary stenosis less than 70%. The timely identification and intervention in these patients can avert acute coronary events and reduce mortality.

Patients with mild-to-moderate coronary artery stenoses may not exhibit specific

symptoms, however, it is associated with a significantly high prevalence rate in

patients with CHD. According to a 2008 study involving 1000 asymptomatic

middle-aged subjects undergoing coronary computed tomography angiography (CCTA),

the incidence of coronary stenoses ranged from 25% to 74%, with an overall

incidence of 8.3‰, while more than 75% exhibited severe

stenosis. The incidence of coronary artery stenosis further escalates with

progressive aging [3]. In 2019, a study conducted in South Korea on 601 healthy

individuals who underwent CCTA revealed that 173 cases (28.8%) exhibited

coronary artery stenosis, with an average stenosis rate of 25.8

The presence of mild to moderate coronary artery stenosis may also contribute to the onset of acute cardiovascular events. The study included data from 42 patients who underwent invasive coronary angiography (ICA) before and after myocardial infarction (MI), and assessed the degree of stenosis of infarct-associated vessels in 29 patients with a new MI prior to the event. Among these patients, 19 (66%) had lumen diameters less than 50% and 28 (97%) had lumen diameters less than 70%. Interestingly, only a minority of MI (34%) were attributed to severe arterial occlusion observed on previous imaging studies, suggesting that atherosclerotic stenosis alone is not the primary etiology for cardiovascular events. Conversely, such events are more likely to occur in cases with mild-to-moderate stenosis [5]. Mild-to-moderate coronary artery stenosis may pose a greater risk compared to severe coronary artery stenosis due to the inherent instability of the plaque, making it more susceptible to rupture and thrombosis, thereby leading to vascular embolism and acute cardiovascular events. This study provides a comprehensive review on the detection, risk assessment, pathogenesis, and intervention strategies for mild to moderate coronary artery stenosis in order to increase attention to the prevention and treatment of patients with mild-to-moderate coronary artery stenosis.

The definitions of mild to moderate coronary artery stenosis vary among

different detection methods and institutions. In the CCTA test, the stenosis of

each coronary artery is classified as follows: minimal (

The evaluation of patients with mild to moderate coronary stenosis involves two aspects. First, the assessment of the degree of lumenal stenosis and plaque structure is mainly conducted through ICA, CCTA, cardiac magnetic resonance (CMR), intravascular ultrasound (IVUS), optical coherence tomography (OCT), and near infrared spectroscopy (NIRS). Second, the functional evaluation focuses on the impact of hemodynamics in patients with coronary stenoses and includes fractional flow reserve (FFR), instantaneous wave-free ratio (iFR) and quantitative flow fraction (QFR).

CCTA is a non-invasive imaging modality that exhibits high sensitivity in detecting CAD. It can effectively visualize early coronary atherosclerosis in patients with specific conditions, including plaque load (calcium score, lesion segment points, etc.), plaque composition, and high-risk plaque based on anatomical and functional image information [9]. The use of enhanced CT measurements has been shown to predict cardiovascular events by assessing arterial calcium (CAC) scores [10]. The CAC score may be appropriate for specific asymptomatic patients with a moderate risk of CAD, enabling non-invasive evaluation of coronary atherosclerotic plaques and identification of high-risk plaques for risk stratification [11]. CCTA displays high-risk plaque characteristics (HRP), which include low density, positive remodeling, punctate calcification, and “napkin ring” appearance [12]. Risk models have demonstrated that the presence of high-risk plaque characteristics independently predicts cardiovascular events [13]. The calculation of the peripheral fat attenuation index (FAI) score on CCTA enables a direct quantification of the residual vascular inflammatory load [14].

A recent study has demonstrated that artificial intelligence-based novel CCTA

assessment can rapidly and accurately identify and exclude stenoses, and are

consistent with blinded, core laboratory-interpreted quantitative coronary

angiography [15]. In comparison to ICA, CCTA tends to overestimate the degree of

coronary artery diameter stenosis by 5.7%–8.5% during diastole (QCT-D) and by

9.4%–11.9% during systole (QCT-S) (p

CMR is a highly effective noninvasive imaging technique for evaluating coronary vascular stenoses, that can comprehensively assess the heart’s structure, function, blood perfusion, and characteristics. It provides detailed imaging features of both the vascular lumen and wall and is non-invasive and has no radiation exposure. CMR offers high spatial and temporal resolution, excellent reproducibility and accuracy, even in individuals with a high body mass index [20]. A multicenter trial conducted by Kato et al. [21] demonstrated that 1.5-T whole-heart CMRA exhibits a high negative predictive value of 88%. This indicates that whole-heart CMRA is effective in excluding the presence of coronary artery disease and thus plays a valuable role in reducing the need for invasive angiography, as opposed to the technical limitations of CCTA, which results in false positive or negative results in the presence of severe calcification [22]. CMRA has better diagnostic performance than CCTA in detecting significant stenosis of coronary artery segments with moderate to severe calcified plaques [23]. Kim et al. [24] demonstrated that CMR can accurately identify an increase in coronary artery wall thickness in patients with non-significant (10%–50%) CAD, while maintaining lumen size. This finding contributes to the enhancement of risk stratification for individual patients, facilitating early treatment and prevention of acute coronary events. The sensitivity of CMR is relatively high, but the long imaging duration and high cost impose a burden on patients. In addition to concerns regarding gadolinium contrast media, CMR cannot be performed in patients with non-MR pacemakers or implantable cardioverter defibrillators, significantly limiting its clinical application [25]. In addition, CMRA is subject to motion artifacts due to both respiration and cardiac pulsation, which significantly limit its image quality. It’s lower spatial resolution hinders the assessment of small coronary vessels.

ICA remains the “gold standard” for the diagnosis of coronary artery stenosis. It can be used to make a definitive diagnosis of the location, extent, and severity of the lesion, and the condition of the vessel wall, to determine the treatment plan (interventional, surgical, or medical management), and can also be used to determine the efficacy of the treatment. However, its methodology for determining the degree of coronary stenosis based on the degree of contrast filling the vessel does not allow for assessment of either the specifics of the lumen or the characteristics and morphology of the diseased plaque. The invasive nature and cost of the technique limit its usefulness in assessing plaque stability and predicting the development of acute coronary syndromes [26]. The utilization of this method for assessing patients with mild-to-moderate coronary artery stenoses is subject to certain limitations, which include potential complications, increased cost, as well as radiation exposure and discomfort experienced by both patients and operators. Additionally, there exists inter-operator variability in assessing coronary stenosis definitions which may impact its clinical application in patients with mild-to-moderate stenoses.

In addition to assessing the degree of stenosis of the vessel lumen, detailed

evaluation of the plaque structure is more comprehensive and meaningful in

predicting its prognosis. IVUS, OCT, NIRS are utilized to identify high-risk

plaques and assess plaque inflammation. IVUS is one of the most widely used

invasive imaging methods for studying coronary plaques. Radiofrequency ultrasound

echo data identify plaque components, including plaque burden, expansive

remodeling, necrotic core, calcification, and neovascularization [27]. In

addition, despite the inability to measure the thickness of the thin fibrous cap,

a prospective study has shown that IVUS-defined thin-cap fibrous atherosclerotic

tumors (TCFA) are associated with major future adverse cardiovascular events

[28]. OCT is the second major invasive imaging method for coronary artery

plaques. OCT uses near-infrared light with a wavelength of 1.3 µm to image

the plaques, and the resolution can reach up to 20 µm. It can clearly show

the thickness of the fibrous cap and the collagen content, effectively identify

macrophages and neovascularization, and accurately determine plaque rupture, and

the presence of thrombi [29]. However, due to the high scattering effect of its

imaging medium, OCT is limited by longer image acquisition times and numerous

artifacts. It is difficult to evaluate the deep plaque structure, and its ability

to distinguish between calcified areas, such as microcalcifications with a

diameter of less than 5 µm, and the lipid core, is also relatively poor

[30]. To address this challenge, a new form of OCT with 1 to 2 µm

resolution, termed micro-OCT (µOCT), has been developed. This technology

can visualize key events in the development and progression of atherosclerosis at

the cellular and molecular levels, including leukocyte extravasation, fibrin

filament formation, extracellular matrix (ECM) production, endothelial

denudation, as well as microcalcification, cholesterol crystal formation, and

fibrous cap penetration [31]. High-resolution OCT excels in detecting potential

palque vulnerability, such as thin fibrous caps in atherosclerotic plaques. The

most reliable imaging method is confirming plaque erosion. NIRS utilizes the

characteristic emission spectra generated by the interaction of plaque content

with photons and is suitable for assessing the lipid content of plaques,

especially in the case of positive remodeling, large, deep, and lipid-rich

necrotic cores (maximal lipid core burden index in a 4 mm segment

FFR is the most effective indicator for assessing the hemodynamic significance

of a coronary artery stenosis. FFR represents the ratio of blood flow through a

stenosed coronary artery to that in the absence of stenosis, derived from

applying Poiseuille’s law and calculating the ratio of arterial pressure distal

to proximal to the stenosis. FFR serves as the “gold standard” for functional

evaluation at ICA [34]. The application of computational fluid dynamics in

estimating FFR based on CCTA studies has demonstrated a strong correlation with

invasive measurements, as evidenced by preliminary research findings [35]. In

evaluating percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI) outcomes in patients with

moderate stenosis (40%–70%), FFR guidance is non-inferior to IVUS guidance

regarding composite endpoints such as death, myocardial infarction, or

revascularization at 24 months [36]. An FFR

The presence of mild-to-moderate coronary artery stenosis did not exert a significant impact on hemodynamics. Nevertheless, owing to its high prevalence, the incidence rate of cardiovascular events remains elevated in this population. Given its widespread occurrence, the absolute number of incidents within this specific group remains substantial [45].

In comparison to patients without coronary artery disease, those with

A summary of these studies involving patients with mild-to-moderate coronary stenosis is presented in Table 1 (Ref. [7, 12, 13, 48, 49, 50, 51, 53]).

| Time | Country | Inclusion criteria | Subjects | Follow-up time (median) | Incidence and outcome events | |

| Yeonyee et al. [48] | 2012 | Japan | Suspected CAD | 207 | 25 months | The degree of stenosis |

| Yorgun et al. [49] | 2013 | Türkiye | Mild-to-moderate coronary artery stenosis ( |

1115 | 29.7 |

The incidence of MACE was 2.6% |

| Nakazato et al. [7] | 2014 | Multiple centers | Nonobstructive CAD | 15,187 | 2.4 |

The incidence of MACE was 1.22% in patients with stenosis |

| Chow et al. [50] | 2015 | Multiple centers | Normal or non-obstructive CAD (1%–49%) | 27,127 | 27.2 months | Mortality rate of 0.44% |

| Feuchtner et al. [51] | 2017 | Australia | CAD of low to moderate risk | 1469 | 7.8 years | The incidence of MACE was 1.3%, 2.5%, and 3% in patients with stenosis |

| Senoner et al. [12] | 2020 | Australia | CAD of low to moderate risk | 1469 | 10 years | The incidence of MACE was 2.8%, 3.5%, and 5.7% in patients with stenosis |

| Taron et al. [13] | 2021 | Multiple centers | Left main stenosis (1%–49%) or other (1%–69%) | 2890 | 26 months | The incidence of endpoint event was 3.3% |

| Huang et al. [53] | 2024 | China | Nonobstructive CAD | 2522 | 9 years | Annualized all-cause mortality: 4.9%, 8.2%, 13%, and 18% in the no CAD, 1-, 2-, and 3-vessel nonobstructive CAD groups, respectively |

Annotation: CAD, coronary artery disease; MACE, major adverse cardiovascular events.

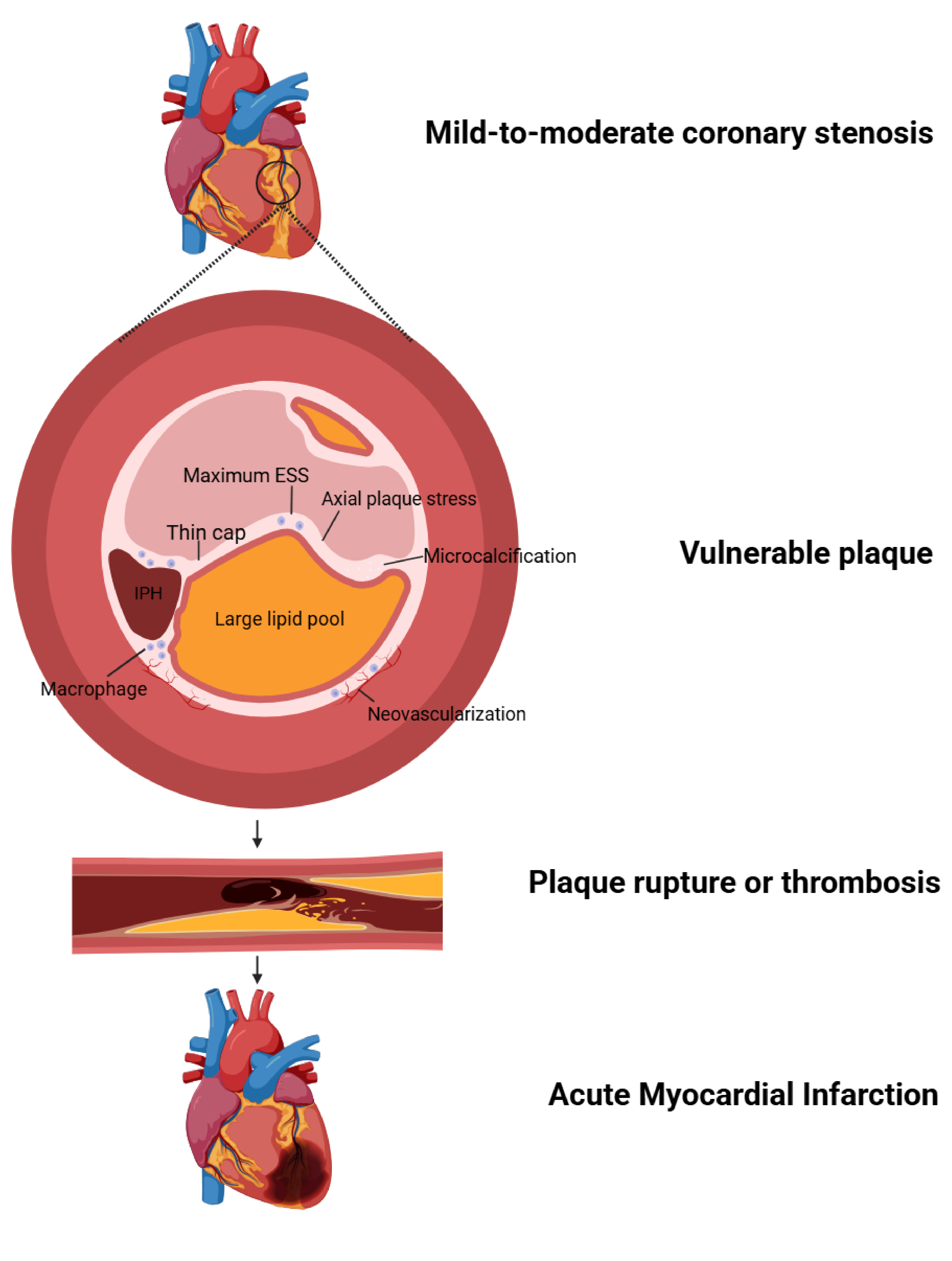

The primary etiological mechanism leading to major adverse cardiovascular events is the development of focal necrosis in the corresponding myocardium due to persistent ischemia caused by severe obstruction of the coronary lumen. In patients with mild-to-moderate coronary stenosis, the occurrence of cardiovascular events, in addition to the classical pathogenesis of the natural progression of coronary atherosclerosis, is closely related to the degree of plaque burden throughout the coronary arteries (Fig. 1), including both anatomical and biomechanical characteristics [54].

Fig. 1.

Fig. 1.

The pathophysiological mechanisms underlying acute cardiovascular events in patients with mild-to-moderate coronary stenosis. ESS, endothelial shear stress; IPH, intraplaque hemorrhage. Created with Biorender.com

The findings from autopsy studies have revealed that coronary luminal thrombosis

can be attributed to three distinct morphological entities: plaque rupture

(55–65%), plaque erosion (30–35%), and calcified nodules (2–7%) [55].

Plaque rupture of the precursor lesion, known as “vulnerable plaque”, is

considered the primary mechanism for sudden lumen thrombosis in patients with

mild-to-moderate coronary stenosis, leading to adverse cardiac events [13, 56].

Studies have demonstrated that more susceptible ruptured plaques are obstructive

plaques characterized by a thin fibrous cap (

Macrophages, are the primary inflammatory cells in plaques and play a crucial

role in plaque vulnerability. During the process of phagocytosing cholesterol

crystals, macrophages contribute to ROS cluster-mediated cellular damage and

plaque rupture by releasing TNF-

The new blood vessels typically consist of a single-layer ECM on the basement membrane, lacking support from smooth muscle cells (SMC). This renders the immature plaque blood vessels highly susceptible to damage. Activation of macrophages and mast cells can result in the release of matrix metalloproteinases and inflammatory cytokines, further contributing to the impairment of these newly formed blood vessels [68]. New blood vessels enhance macrophage infiltration and promote red blood cell sources of cholesterol in the lipid core transport, thereby accelerating the progress of atherosclerosis and intraplaque hemorrhage (IPH), resulting in an increase in plaque volume, and promoting plaque rupture [69]. In contrast, Brezinski et al. [70] believes that angiogenesis is a supply line for repairing cells in the healing area of the coronary artery. In vulnerable plaques with long necrotic cores, supply lines to the damaged area may not be reliably established, leading to plaque instability [70].

The involvement of mast cells is also crucial in atherosclerotic plaque rupture. The fibrous cap consists of vascular smooth muscle cells (VSMCs) and their collagen production, rendering the thin cap susceptible to rupture. The presence of activated mast cells is elevated in ruptured coronary plaques, leading to the secretion of heparan proteoglycans that effectively inhibit VSMC proliferation and reduce their collagen-producing capacity. The Mi enzyme, a neutral serine protease secreted by VSMCs, plays a role in inhibiting collagen synthesis mediated by SMC through its dependence on transforming growth factor beta and activates MMP-1 for extracellular matrix degradation. Furthermore, Mi enzyme promotes SMC apoptosis by degrading fibronectin, an essential component for SMC adhesion to the extracellular matrix. Both mechanisms contribute to weakening and eventual rupture of the thin fibrous cap in atherosclerotic plaques [71, 72]. The presence of a large necrotic core rich in lipid and collagen, along with the absence of cells and the eccentric distribution of the lipid core caused by patches of circumferential stress and shoulder area rearrangement, leads to an increased vulnerability of plaques [73].

Vascular calcification is associated with an elevated risk of cardiovascular

disease. Lineage tracing studies in mice have shown that 98% of plaque bone

cartilage cells originate from VSMC, which are formed in response to high levels

of calcium and phosphate, contributing to bone cartilage formation phenotypes

[74]. Microcalcification (

In addition to the properties and components of the plaque, coronary biomechanical forces also play a crucial role in the progression of coronary plaques, including endothelial shear stress (ESS), plaque structural stress (PSS), and axial plaque stress (APS) [76]. Wall shear stress (WSS) refers to the parallel friction force exerted by blood flow on the endothelial surface, which is considered as the key hemodynamic force influencing the occurrence, development, and transformation of atherosclerotic plaques. Low WSS disrupts the homeostatic atherogenic protective properties of normal endothelium, resulting in blood flow stagnation in that region and promoting plaque formation. High WSS can induce damage to vascular endothelial cells through increased expression of matrix-degrading metalloproteinases, leading to inflammation and oxidative stress. This ultimately increases plaque vulnerability and raises the risk for thrombosis [77].

PSS represents mechanical stresses located within an atherosclerotic plaque or arterial wall caused by changes in arterial pressure and cardiac motion-induced vasodilation, and stretching. PSS significantly increases with fibrous cap thickness reduction, necrotic core area enlargement, and microcalcification accumulation. Elevated PSS promotes macrophage accumulation while limiting smooth muscle cell activity through activated matrix metalloproteinase expression. These processes lead to matrix degradation and thinning fibrous caps until PSS exceeds their mechanical strength causing rupture. APS refers to the stress exerted on the surface of atherosclerotic plaque in the vessel wall, which is responsible for force imbalance within the lesion. Plaque formation and growth alter the mechanical properties of the vessel wall, resulting in localized areas of stress. Elevated APS increases the likelihood of plaque rupture and detachment, leading to adverse cardiovascular events. Furthermore, a significant inverse correlation was observed between APS and lesion length, which explains why short lesions and focal lesions have a higher incidence of plaque rupture compared to diffuse lesions [78].

The general intervention in patients with mild-to-moderate coronary stenosis follows the same overall strategy for preventing coronary atherosclerotic stenosis: maintaining a healthy diet and normal body weight, engaging in regular exercise, quitting smoking, and regularly monitoring blood pressure, cholesterol levels, and blood glucose. Additionally, incorporating rehabilitation training into the treatment of patients with mild-to-moderate coronary stenosis has shown significant effects by reducing the incidence of vulnerable plaques and improving plaque composition, thereby lowering the risk of cardiovascular disease [79]. Furthermore, a study has indicated that certain traditional Chinese medicine treatments such as acupuncture may serve as effective adjunct therapies for patients with stable angina pectoris and moderate (40%–70%) CAD by regulating brain activity [80].

Selective drugs target the modification of the atherosclerotic plaque, address risk factors, and manage the environment of clots and inflammation. These drugs include statins and antiplatelet agents.

The administration of statins has been shown to have lipid-lowering properties, improve endothelial function, exhibit antioxidative and anti-inflammatory effects, possess antithrombotic properties, and effectively prevent the development of atherosclerosis. Furthermore, they promote plaque stability and reduce the incidence of cardiovascular disease and mortality [50, 81]. Statin treatment has been shown to effectively reduce the progression of low attenuation plaques and non-calcified plaques [82]. A 2013 review [83] retrospectively analyzed a cohort of 1952 patients with coronary stenosis ranging from 1–69% on CCTA. Statins were found to have significant benefits in patients with non-calcified or mixed plaques (HR: 0.47, p = 0.047). However, no benefit was observed in reducing adverse events. In patients with stable angina pectoris and mild-to-moderate coronary artery stenosis, a daily dose of 40 mg atorvastatin is superior to 20 mg [84]. High-intensity statin therapy results in a significant increase in the minimum thickness of fibrous cap and reduction in the presence of vulnerable plaques, potentially transforming up to three-quarters of plaques into a more stable phenotype within 13 months after infarction-related coronary artery events [85]. However, it is important to note that they may also increase the incidence of liver and kidney damage, myalgia, rhabdomyolysis, among other adverse effects. Therefore, further investigation is required to assess the benefits and risks specifically in patients with mild-to-moderate coronary artery stenosis that are not hemodynamically significant.

The Proprotein convertase subtilisin/kexin 9 (PCSK9) inhibitors decrease the

degradation of the low-density lipoprotein (LDL) receptors. They are primarily

used to lower low-density lipoprotein cholesterol (LDL-C) and are particularly

useful in patients with pure familial hypercholesterolemia. In addition, studies

have shown that PCSK9 inhibitors decrease the degradation of the LDL receptors

[86]. A study has shown that the use of PCSK9 inhibitors is accompanied by a

beneficial remodeling of the inflammatory load in patients with atherosclerosis.

This effect may be, or is partially, independent of their ability to lower LDL-C

and may provide additional cardiovascular benefits [87]. The 2024 edition of the

European Society of Cardiology (ESC) guidelines recommends that all patients with

chronic coronary syndrome (CCS) should be treated with the highest tolerated dose

of a high-intensity statin in order to achieve an LDL-C

Aspirin is the most classical antiplatelet drug, which inhibits platelet aggregation and activation induced by neutrophils. It also reduces nitric oxide production by limiting endothelial prostacyclin synthesis and protects low-density lipoproteins from oxidative modification, thereby impeding the progression of atherosclerosis [89]. A multicenter study conducted in seven countries demonstrated that aspirin treatment did not significantly reduce the risk of major cardiovascular events in patients with moderate risk [90]. In a study involving patients with non-obstructive stenosis (1%–49%), the use of aspirin did not have a significant impact on MACE, baseline all-cause mortality, or MI [91]. The findings of a meta-analysis demonstrated that aspirin exhibited a significant reduction in the incidence of cardiovascular events among individuals without cardiovascular disease. However, it was associated with an elevated risk of major bleeding and did not demonstrate any impact on mortality [92]. This limits its use in individuals with low risk or those who are intolerant to aspirin.

In 2019, Lee et al. [93] enrolled 100 diabetic subjects with mild-to-moderate coronary stenosis as assessed by CCTA. The findings revealed that treatment with ciliostazole for a duration of 12 months resulted in significant reductions in coronary artery stenosis and non-calcified plaque components, along with an increase in high density cholesterol levels, and decreased levels of triglycerides, liver enzymes, and highly sensitive C-reactive protein. Furthermore, it was observed that abdominal visceral fat area and insulin resistance were also reduced as a result of this intervention. In a subsequent extended study with a median follow-up period of 5.2 years [94], cilostazole treatment demonstrated its superiority over aspirin in reducing the incidence of cardiovascular events among subclinical CAD patients with diabetes.

A study demonstrated that the administration of isosorbide mononitrate combined with nicorandil can effectively reduce levels of inflammatory factors, thereby improving myocardial ischemia and alleviating symptoms associated with mild-to-moderate coronary stenosis and unstable angina [95]. Recent studies have demonstrated that sodium-glucose transporter 2 inhibitors (SGLT2-I) exhibits a beneficial effect on improving lipid deposition, inflammation, and thickness of atherosclerotic plaques, while also reducing MACE by half—the most favorable clinical outcome—in diabetic patients with multi-vessel nonobstructive coronary artery stenosis (20–49%). Furthermore, the implementation of ICA and OCT following SGLT2-I treatment has shown to predict a 65% lower risk of MACE during one-year follow-up [96]. The anti-inflammatory effects of colchicine are distinct, and in a randomized trial involving patients with chronic CAD, those who received a daily dose of 0.5 mg of colchicine exhibited a significantly reduced risk of cardiovascular events compared to the placebo group [97]. Despite numerous reports on drug intervention in patients with mild-to-moderate coronary artery stenosis, the specific mechanism and application criteria remain unclear, necessitating the need for further extensive clinical trials and studies to confirm these findings.

FFR is employed to assess whether a stenosis leads to ischemia, enabling an

evaluation of moderate coronary artery lesions suitable for PCI [98]. An

international multicenter prospective study in Europe and Asia demonstrated that

the risk of cardiac death or MI associated with moderate coronary artery stenosis

based on FFR

Although patients with mild-to-moderate coronary artery stenosis may not exhibit characteristic clinical symptoms, they have a high incidence and are at a high risk for cardiovascular events. Therefore, early intervention to reduce these events is of great significance in the management of CHD. Currently, there is a lack of specific risk assessment models for patients with mild-to-moderate arterial stenosis, and the benefits and risks associated with PCI and drug interventions are still under debate. Clear guidelines for control are also lacking. Thus, further research is needed to investigate the unique mechanisms underlying mild-to-moderate arterial stenosis and develop effective intervention strategies aimed at reducing both the progression of coronary artery narrowing and acute events as well as reducing mortality rates associated with CHD.

All authors contributed to the conception and design of the study. The first draft of the manuscript was written by CG, with HG and XB helping to consult the literature. Writing guide: XC, LG and NL. All authors have commented on previous versions of the manuscript. All authors contributed to editorial changes in the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript. All authors have participated sufficiently in the work and agreed to be accountable for all aspects of the work.

Not applicable.

Not applicable.

This work was supported by Jining Medical University Research Fund for Academician Lin He New Medicine (JYHL2022), Shandong Province Key Project of TCM science and technology (Z-2022081), Key research and development plan in Jining City (2023YXNS031).

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

Publisher’s Note: IMR Press stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.