1 Clinic of Cardiology, University Clinical Centre of Kosovo, 10000 Prishtina, Kosovo

2 Medical Faculty, University of Prishtina, 10000 Prishtina, Kosovo

3 Department of Public Health and Clinical Medicine, Umeå University, SE-901 87 Umeå, Sweden

4 Instituto Auxologico IRCCS, 20145 Milan, Italy

5 National Heart and Lung Institute, Imperial College London, SW3 6LY London, UK

Abstract

Heart failure (HF) is a complex clinical syndrome that is associated with high morbidity and mortality. The prognosis of chronic HF in Kosovo has never been objectively assessed and compared with other countries. Thus, this study aimed to investigate the long-term prognostic value of clinical and cardiac function parameters in predicting the mortality of patients in Kosovo with chronic HF.

This study included 203 consecutive patients with chronic HF who were followed up for a mean of 86 ± 40 months. The primary outcome of the study was all-cause mortality.

During the follow-up period, there were 94 deaths (46.3%). Deceased patients were older (p < 0.001), commonly in New York Heart Association (NYHA) class ≥III (p < 0.001), had lower 6-minute walk distances (p = 0.014), higher prevalence of type 2 diabetes mellitus (T2DM) (p = 0.018), raised creatinine (p = 0.001), and lower hemoglobin (p = 0.004). Moreover, these patients often had left bundle branch block (p = 0.001), lower left ventricular (LV) ejection fraction (EF) (p < 0.001), larger left atrium (LA) (p < 0.001), lower lateral and septal mitral annular plane systolic excursion (MAPSE) values (p = 0.001 and p < 0.001, respectively), and tricuspid annular plane systolic excursion (TAPSE) (p = 0.009), reduced lateral systolic myocardial velocity (s’) (p = 0.018), early diastolic myocardial velocity (e’) (p = 0.011) and late diastolic myocardial velocity (a’) (p = 0.010) velocities, reduced septal e’ (p < 0.001) and a’ (p = 0.032) velocities, and had higher E/e’ (p = 0.021), compared to survivors. Multivariate analysis identified NYHA class ≥III (odds ratio (OR) = 5.573, 95% CI 1.688–18.39; p = 0.005), raised creatinine (OR = 1.027, 95% CI 1.006–1.047; p = 0.011), advanced age (OR = 1.069, 95% CI 1.011–1.132; p = 0.020), enlarged LA (OR = 3.279, 95% CI 1.033–10.41; p = 0.044), and left ventricular ejection fraction (LVEF) ≤45% (OR = 3.887, 95% CI 1.221–12.38; p = 0.022), as independent predictors of mortality.

In medically treated patients with chronic HF from Kosovo, worse functional NYHA class, impaired kidney function, age, compromised LV systolic function, and enlarged LA were independently associated with increased risk of long-term all-cause mortality.

Keywords

- heart failure

- predictors

- echocardiography

- outcome

- mortality

Despite many recent advances in the diagnosis and treatment of heart failure (HF), this condition remains a complex, heterogeneous, life-threatening clinical syndrome, which is accompanied by high morbidity and mortality, poor quality of life, and high economic burden [1, 2, 3]. HF affects more than 64 million people worldwide; thus, this syndrome is considered a global pandemic [4]. Moreover, the prevalence of HF is predicted to continue rising due to population longevity, which is impacted by advances in medical treatment [5]. Although survival rates of chronic HF patients have already increased over the past decades, the 5-year survival remains close to 50%, and the 10-year survival is less than 35% [6]. HF may be caused by several underlying etiologies, and is often accompanied by cardiac and non-cardiac comorbidities, associated with different adverse outcomes [1]. Previous studies have identified different clinical and echocardiographic predictors of short- and long-term outcomes of HF patients [7, 8, 9, 10, 11, 12]. However, the results are controversial and depend on the type of HF, the age of the patients, the geographic area of residence, and the national economic status. The prognosis of chronic HF in Kosovo has never been objectively assessed and compared with other countries. Therefore, this prospective study aimed to investigate the long-term prognosis of a group of patients admitted with HF at the Clinic of Cardiology, University Clinical Centre of Kosovo. The data for each patient included epidemiological, clinical, and echocardiographic heart structure and function parameters.

We enrolled 268 patients, who were admitted at the Clinic of Cardiology (Second

Division), University Clinical Centre of Kosovo, between September 2009 and

November 2013, with the diagnosis of chronic HF, based on the available

definitions at the time. All included patients were in New York Heart Association

(NYHA) functional classes I–III, including those with ischemic and non-ischemic

etiologies [13]. All patients were also receiving conventional, optimized HF

treatment, based on the available clinical guidelines in use at the time of the

study. During the follow-up period, 65 patients were inaccessible and were

therefore excluded from the analysis. The exclusion criteria were, cardiac

decompensation (NYHA class IV, those with peripheral edema), recent acute

coronary syndrome, severe mitral regurgitation, stroke, limited physical activity

due to cardiac and/or non-cardiac causes, significant anemia, more than mild

renal failure (raised creatinine

The patients were categorized into two groups: HF with preserved EF (HFpEF: EF

The medical history of each patient was obtained, and a clinical examination was

undertaken in all patients at the time of enrollment. Biochemical tests,

including lipid profile, blood glucose level, kidney function tests, and

hemoglobin, were also performed in all patients. Body mass index (BMI) was

measured using weight and height measurements, and the body surface area (BSA)

was calculated using the Du Bois formula: BSA (m2) = 0.007184

Cardiac structure and function were studied using conventional Doppler

echocardiography. All echocardiographic examinations were performed by a single

operator using the Philips Intelligent E-33 system (Philips Healthcare, Andover,

MA, USA), equipped with a multi-frequency transducer and harmonic imaging as

needed. Images were obtained during quiet expiration, while the patient was in

the left lateral decubitus position. LV end-diastolic and end-systolic

dimensions, as well as interventricular septal and posterior wall thickness, were

measured based on the recommendations of the European and American Society of

Echocardiography [17, 18]. Left ventricular volumes and EF were calculated using

the modified Simpson’s method. The M-mode technique was used to study left and

right ventricular (RV) long-axis function, placing the cursor at the lateral and

septal angles of the mitral annulus and the lateral angle of the tricuspid

annulus [19]. Long axis measurements were identified as lateral and septal mitral

annular plane systolic excursion (MAPSE) and tricuspid annular plane systolic

excursion (TAPSE). LV and RV long-axis myocardial velocities were also studied

using the Doppler myocardial imaging technique (tissue Doppler imaging, TDI),

from the apical 4-chamber view. Longitudinal velocities were obtained using the

pulsed wave Doppler sample volume placed at the basal part of the LV lateral and

septal segments, as well as the basal part of the RV free wall. Systolic (s’) as

well as early and late (e’ and a’) diastolic myocardial velocities were measured

with the gain optimally adjusted. The mean value of the lateral and septal LV

velocities was calculated [20]. Left atrial (LA) size was estimated in the

parasternal long-axis view from the trailing edge of the posterior aortic wall to

the leading edge of the posterior LA wall, in systole. The LA cavity was

described as enlarged if the transverse diameter was

A 6-minute walk test (6-MWT) was performed within 24 hours of the echocardiographic examination. The test was performed in a level hallway corridor and administered by a specialized nurse, who was blinded to the echocardiographic findings. All study patients, who were on regular medical treatment, were informed of the purpose and protocol of the 6-MWT [26, 27, 28]. Patients were instructed to walk as far as possible for 6 minutes, turning 180° at the end of the corridor. Patients were not influenced by walking speed and walked unaccompanied. The supervising nurse measured the total distance patients walked at the end of the 6 minutes.

After the baseline Doppler echocardiogram, all study patients were followed for

a mean period of 86

Data are presented as the mean

A total of 94/203 (46.3%) patients had died at the end of the follow-up period

of 86

| Variable | All study patients (n = 203) | Survivors (n = 109) | Deceased (n = 94) | p-value |

| Age (years) | 61 |

58 |

65 |

|

| Female (n, %) | 119 (58.6) | 70 (64.2) | 49 (52.1) | 0.088 |

| Smoking (n, %) | 55 (27.8) | 26 (24.3) | 29 (30.9) | 0.343 |

| Diabetes mellitus (n, %) | 56 (28.1) | 22 (20.8) | 34 (36.6) | 0.018 |

| Arterial hypertension (n, %) | 154 (77.4) | 88 (83) | 66 (71) | 0.061 |

| Atrial fibrillation (n, %) | 34 (16.7) | 16 (14.7) | 18 (19.1) | 0.541 |

| HFrEF (n, %) | 65 (32) | 16 (14.7) | 49 (52.1) | |

| NYHA Class |

57 (28.1) | 10 (9.2) | 47 (50) | |

| LBBB (n, %) | 35 (17.2) | 10 (9.2) | 25 (26.6) | 0.001 |

| Waist/hips ratio | 0.96 |

0.94 |

0.97 |

0.008 |

| BMI (kg/m2) | 29 |

29 |

28 |

0.054 |

| Fasting glucose (mmol/L) | 6.8 |

6.7 |

6.9 |

0.636 |

| Total cholesterol (mmol/L) | 4.7 |

4.87 |

4.49 |

0.090 |

| Triglycerides (mmol/L) | 1.6 |

1.68 |

1.54 |

0.298 |

| Blood urea nitrogen (mmol/L) | 9.3 |

6.7 |

11.4 |

|

| Creatinine (µmol/L) | 101 |

85 |

114 |

0.001 |

| Hemoglobin (g/dL) | 12.6 |

13 |

12.2 |

0.004 |

| 6-MWT distance (m) | 283 |

308 |

253 |

0.014 |

| Baseline HR (beats/min) | 77 |

75 |

78 |

0.118 |

NYHA, New York Heart Association; LBBB, left bundle branch block; 6-MWT, six-minute walk test; BMI, body mass index; HR, heart rate; HFrEF, heart failure with reduced ejection fraction.

Non-survivors had lower left ventricular ejection fraction (LVEF) (p

| Variable | All study patients (n = 203) | Survivors (n = 109) | Deceased (n = 94) | p-value | |

| Systolic LV function | |||||

| LV ejection fraction (%) | 52 |

59 |

49 |

||

| MAPSE lateral (cm) | 1.3 |

1.3 |

1.1 |

0.001 | |

| MAPSE septal (cm) | 1.0 |

1.1 |

0.9 |

||

| Left atrium diameter (cm) | 4.3 |

4.1 |

4.6 |

||

| Lateral s’ wave (cm/s) | 5.7 |

6.0 |

5.4 |

0.018 | |

| Septal s’ wave (cm/s) | 5.0 |

5.15 |

4.65 |

0.071 | |

| Diastolic LV function | |||||

| E/A ratio | 1.1 |

0.93 |

1.3 |

0.015 | |

| E wave deceleration time (ms) | 179 |

186 |

171 |

0.069 | |

| Lateral e’ (cm/s) | 7.1 |

7.7 |

6.5 |

0.011 | |

| Septal e’ (cm/s) | 5.6 |

6.2 |

4.6 |

||

| E/e’ (cm/s) | 9.9 |

8.8 |

11 |

0.021 | |

| Lateral a’ (cm/s) | 8.0 |

8.5 |

7.3 |

0.010 | |

| Septal a’ (cm/s) | 8.0 |

8.3 |

7.2 |

0.032 | |

| Global LV function | |||||

| T-IVT (s/min) | 9.5 |

9.6 |

9.3 |

0.523 | |

| Tei index | 0.42 |

0.49 |

0.56 |

0.118 | |

| RV function | |||||

| TAPSE (cm) | 2.2 |

2.3 |

2.1 |

0.009 | |

| Right e’ (cm/s) | 9.6 |

9.9 |

9.2 |

0.244 | |

| Right a’ (cm/s) | 12.2 |

12.1 |

12.5 |

0.673 | |

| Right s’ (cm/s) | 8.8 |

8.8 |

8.8 |

0.930 | |

LV, left ventricle; RV, right ventricle; A, atrial diastolic velocity; E, early diastolic filling velocity; T-IVT, total isovolumic time; s’, systolic myocardial velocity; e’, early diastolic myocardial velocity; a’, late diastolic myocardial velocity; MAPSE, mitral annular plane systolic excursion; TAPSE, tricuspid annular plane systolic excursion.

In the univariate analysis, age, NYHA class

Fig. 1.

Fig. 1.

Survival free of death predicted by LVEF

| Univariate analysis | Multivariate analysis | |||||

| Variable | OR | 95% CI | p-value | OR | 95% CI | p-value |

| Age | 1.082 | (1.047–1.119) | 1.069 | (1.011–1.132) | 0.020 | |

| Female gender | 0.607 | (0.345–1.065) | 0.082 | |||

| BMI | 0.932 | (0.866–1.002) | 0.057 | |||

| Smoking | 1.424 | (0.765–2.650) | 0.264 | |||

| Diabetes | 2.241 | (1.195–4.204) | 0.012 | 1.716 | (0.536–5.487) | 0.363 |

| Cholesterol | 0.789 | (0.597–1.041) | 0.940 | |||

| Creatinine | 1.024 | (1.010–1.038) | 0.001 | 1.027 | (1.006–1.047) | 0.011 |

| Hemoglobin | 0.774 | (0.647–0.925) | 0.005 | 1.021 | (0.758–1.376) | 0.889 |

| NYHA class |

9.900 | (4.603–21.29) | ˂0.001 | 5.573 | (1.688–18.39) | 0.005 |

| Severely enlarged left atrium | 5.485 | (2.650–11.36) | ˂0.001 | 3.279 | (1.033–10.41) | 0.044 |

| LVEF |

6.329 | (3.248–12.33) | ˂0.001 | 3.887 | (1.221–12.38) | 0.022 |

| E/A | 1.587 | (1.071–2.351) | 0.021 | |||

| 6-minute walk distance | 0.996 | (0.992–0.999) | 0.017 | |||

| MAPSE lateral | 0.214 | (0.085–0.537) | 0.001 | |||

| MAPSE septal | 0.104 | (0.033–0.325) | ˂0.001 | |||

| TAPSE | 0.469 | (0.263–0.838) | 0.011 | 0.999 | (0.411–2.266) | 0.936 |

| S’ lateral | 0.798 | (0.658–0.967) | 0.021 | |||

| S’ septal | 0.807 | (0.636–1.023) | 0.076 | |||

| E/e’ | 1.060 | (1.006–1.117) | 0.028 | |||

LVEF, left ventricular ejection fraction; MAPSE, mitral annular plane systolic excursion; TAPSE, tricuspid annular plane systolic excursion; NYHA, New York Heart Association; BMI, body mass index; HR, heart rate; A, atrial diastolic velocity; E, early diastolic filling velocity; e’, early diastolic myocardial velocity.

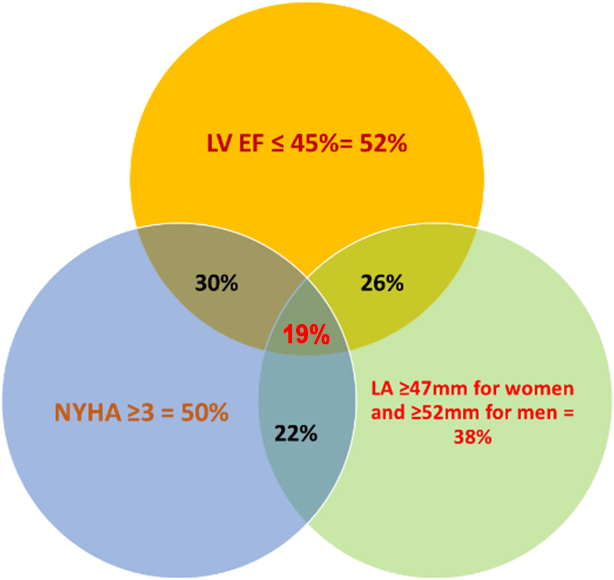

Predictor accuracies were not significantly different from one another, except

for the enlarged LA, which was modestly lower than the others. In total, 52% of

the deceased patients had an LVEF

Fig. 2.

Fig. 2.

Venn diagram of the percentages of the deceased patients with HF

who had an LVEF

During the follow-up period, 45/138 (32.3%) patients with an EF

| LVEF |

LVEF | |||||

| Variable | OR | 95% CI | p-value | OR | 95% CI | p-value |

| Age | 1.033 | (0.952–1.121) | 0.436 | 1.085 | (0.980–1.201) | 0.118 |

| Diabetes | 2.973 | (0.642–13.77) | 0.164 | 1.092 | (0.123–9.759) | 0.983 |

| Creatinine | 1.025 | (1.004–1.046) | 0.021 | 1.046 | (0.989–1.107) | 0.117 |

| Hemoglobin | 1.020 | (0.710–1.466) | 0.913 | 1.460 | (0.676–3.152) | 0.355 |

| NYHA class |

9.299 | (1.985–43.56) | 0.005 | 6.717 | (0.484–93.13) | 0.156 |

| Enlarged left atrium | 5.145 | (0.994–26.64) | 0.051 | 2.973 | (0.311–28.46) | 0.344 |

| TAPSE | 0.600 | (0.197–1.852) | 0.368 | 2.424 | (0.340–17.42) | 0.376 |

NYHA, New York Heart Association; TAPSE, tricuspid annular plane systolic excursion; LVEF, left ventricular ejection fraction; HF, heart failure.

This follow-up study of a cohort of Kosovo patients with chronic HF who were

clinically stable on conventional HF medical treatment identified several factors

that predicted all-cause mortality within a follow-up period of 86

In this study, the deceased patients were older, predominantly smokers, with

worse kidney function, worse NYHA class, and shorter 6-minute walk test distance.

These patients also exhibited worse cardiac function, characterized by a lower

LVEF, a larger LA, and clear signs of elevated LV filling pressures, yet a

similar degree of LV global dyssynchrony, as assessed by total isovolumic time

and Tei index. Therefore, although clinically stable at the beginning of the

study, the deceased patients were in worse clinical condition compared to the

survivors. This probably justifies their higher all-cause mortality, which was

likely contributed to by many other clinical factors in addition to cardiac

dysfunction. Interestingly, the accuracy of the above predictors was not

significantly different, except for that of the enlarged LA, which is secondary

to the primary LV systolic and diastolic disturbances. The coexistence of the

three predictors was identified in only 19% of the deceased, thus confirming the

different hemodynamic statuses of the patients, with some having a worse LVEF and

others a stiffer cavity with raised filling pressures and a dilated LA. Splitting

patients into two groups based on LVEF (

This study has some obvious limitations. Although it was a prospective study in its nature, several patients did not fulfil the inclusion criteria and therefore had to be excluded; hence, the study cannot be described as consecutive. Furthermore, the study did not include myocardial deformation measurements, as these were not part of the routine clinical protocol used to assess the patients. The cohort size is modest, so we could not classify the patients into small groups according to the most likely clinical diagnosis that led to death. We also did not use the current HF classification based on LVEF, which was not available at the time of planning. Modern medical treatments, according to current clinical guidelines, were not available at the time; this could have altered our results. The left atrial diameter was used in this study, rather than the more robust indices of the left atrium, which can also assess left atrial function.

In a group of patients from Kosovo with chronic HF, age, worse NYHA class, and

severity of LV dysfunction, in addition to renal impairment, predicted all-cause

mortality. Patients with an LVEF

In medically treated patients from Kosovo with chronic HF, worse functional NYHA

class, impaired kidney function, age, compromised LV systolic function, and

enlarged LA were independently associated with an increased risk of long-term

all-cause mortality, particularly in patients with an LVEF above 45%. The

relevance of these predictors in patients with an LVEF

The datasets used and analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

GB, MH and PI designed the research study. GB, ABaj, and AP performed the research. GA, AP and ABat collected data. SE, PI and GB analyzed the data. GB and SE drafted the manuscript. MH and FD offered guidance in the study design and intellectual input. All authors contributed to critical revision of the manuscript for important intellectual content. All authors read and approved the final manuscript. All authors have participated sufficiently in the work and agreed to be accountable for all aspects of the work.

The study was carried out in accordance with the guidelines of the Declaration of Helsinki. Ethics Committee of Medical Faculty, University of Prishtina, with reference number 1056/2009. All included patients provided signed informed consent to participate in the study.

Not applicable.

This research received no external funding.

The authors declare no conflict of interest. Michael Y. Henein is serving as one of the Editorial Board members and Guest Editors of this journal. We declare that Michael Y. Henein had no involvement in the peer review of this article and has no access to information regarding its peer review. Full responsibility for the editorial process for this article was delegated to Massimo Iacoviello.

References

Publisher’s Note: IMR Press stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.