1 Department of Cardiology, Jiading Branch of Shanghai General Hospital, Shanghai Jiao Tong University School of Medicine, 800 Huangjiahuayuan Road, 201803 Shanghai, China

2 Department of Cardiovascular Surgery, Ruijin Hospital, Shanghai Jiao Tong University School of Medicine, 197 Ruijin Er Road, 200025 Shanghai, China

3 Department of Cardiovascular Medicine, Ruijin Hospital, Shanghai Jiao Tong University School of Medicine, 197 Ruijin Er Road, 200025 Shanghai, China

4 Department of Cardiovascular Medicine, Ruijin-Hainan Hospital, Shanghai Jiao Tong University School of Medicine, 41 Kangxiang Road, 571473 Qionghai, Hainan, China

†These authors contributed equally.

Abstract

Abdominal aortic aneurysm (AAA) is a major public health challenge and presents high mortality due to diagnostic and therapeutic difficulties. This study investigated the role of high-mobility group box2 (HMGB2) and the HMGB2-triggering receptor expressed on the myeloid cell (TREM) pathway in male AAA patients. The goal was to evaluate HMGB2 as a novel biomarker and to elucidate its contribution to the pathogenesis of AAA. Our findings offer new insights into AAA biology and highlight the potential application of HMGB2 for early detection and therapeutic targeting.

This retrospective case–control study included 36 male AAA patients and 41 male controls with balanced baseline characteristics. HMGB1, HMGB2, soluble TREM-1 (sTREM-1), and sTREM-2 serum levels were measured by enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA). The association between HMGB2 and AAA was analyzed using multivariate logistic regression, while the diagnostic performance of HMGB2 was assessed using receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curves.

Elevated HMGB2 and HMGB1 levels were associated with higher risks of AAA (HMGB2: OR: 1.158, 95% CI: 1.011–1.325; p < 0.05; HMGB1: OR: 1.275, 95% CI: 1.048–1.551; p < 0.05) and aneurysm rupture (HMGB2: OR: 1.117, 95% CI: 1.005–1.241; p < 0.05; HMGB1: OR: 1.212, 95% CI: 1.003–1.465; p < 0.05). Meanwhile, sTREM-1 exhibited a negative correlation with AAA (OR: 0.991, 95% CI: 0.985–0.997; p < 0.01). The odds ratios of the fourth quartile HMGB2 and HMGB1 levels for AAA were 6.925-fold and 8.621-fold higher, respectively, than the first quartile levels. The HMGB2 serum level was positively correlated with a larger AAA diameter, with the diameter increasing progressively as the HMGB2 level increased. The area under the ROC curve (AUC) for predicting AAA was 0.713 for HMGB2, 0.677 for HMGB1, and 0.665 for sTREM-1. HMGB1 and sTREM-1 both correlated with HMGB2. Each HMGB1 quartile group exhibited a significant increase as HMGB2 increased. Further, sTREM-1 significantly increased at low to moderate HMGB2 levels but decreased in the highest HMGB2 quartile.

Elevated HMGB2 serum levels are independently associated with the incidence of AAA in males. HMGB2–TREM pathway disruption may play a critical role in AAA pathogenesis.

Keywords

- abdominal aortic aneurysm

- HMGB1

- HMGB2

- sTREM-1

- sTREM-2

Abdominal aortic aneurysm (AAA) is characterized by a permanent, localized dilation of the abdominal aorta that exceeds its normal diameter by 50%, or reaches a maximal diameter of 30 mm [1]. The majority of AAAs are located in the infrarenal aorta, proximal to the aortic bifurcation. The risk of AAA rupture escalates with increasing aortic diameter [2]. Non-syndromic AAA is a major cause of cardiovascular mortality due to the high risk of aortic rupture. The diagnosis of this condition is challenging because most aneurysms remain asymptomatic until rupture occurs [3, 4]. The incidence of AAA rupture in the American population between 2005 and 2012 was 7.29 per 100,000, accounting for 4%–5% of sudden death cases. Approximately 50% of patients who undergo AAA rupture reach hospital. The operative mortality rate is around 50%, although the exact figure is difficult to determine [4]. In 2017, AAA was responsible for more than 167,000 deaths globally, and 3 million disability-adjusted life years [5, 6]. In 2019, 35.12 million cases of AAA were reported world-wide among individuals aged 30–79 years (0.92%) [7]. Endovascular aneurysm repair (EVAR) and open surgery are the two surgical interventions for AAA repair [8]. While minimally invasive devices for EVAR have improved greatly, the durability of this treatment remains problematic, and the potential for rupture remains [9]. The development of novel therapies, including stem cell therapies, has faced significant challenges. Consequently, a strong imperative is to investigate the mechanisms underlying AAA formation and identify novel specific biomarkers or therapeutic approaches for diagnosing and treating AAA in its early stages.

Substantial evidence indicates the major contributors to AAA are chronic

inflammation and dysregulation of the extracellular matrix (ECM), composed

primarily of elastin and collagen proteins, and the loss of vascular smooth

muscle cells (VSMCs) [10, 11]. The high-mobility group box (HMGB) family is

comprised of four members (HMGB1-4) that play an important role in various

inflammatory diseases and have the capacity to modulate innate immunity [12].

Research indicates that elevated HMGB1 levels are present in the aneurysmal

tissue of human AAA and in murine experimental models of AAA [13]. The studies to

date have predominantly focused on HMGB1, which drives pro-inflammatory signaling

via receptors such as toll-like receptor (TLR) and advanced glycation end product

(RAGE) [14, 15, 16]. Despite sharing

The present study aims to address this gap in knowledge by investigating the specific contribution of HMGB2 to the pathogenesis of AAA, including the potential involvement of the HMGB2-TREM pathway. This should elucidate the potential value of HMGB2 for early detection and therapeutic targeting of AAA.

This retrospective case-control study included 77 consecutive male participants admitted to the cardiovascular surgery department of Ruijin Hospital from January 2019 to November 2021. All participants were screened for AAA.

The inclusion criteria were: (1) male adults who were clinically diagnosed with

AAA; (2) the diameter of the aneurysm as determined by computed tomography (CT)

examination was

The diagnostic criterion for AAA were the updated 2014 guidelines from the

European Society of Cardiology (ESC), i.e., an abnormal local dilation of the

infra-renal aorta at least 1.5-times greater than the normal aortic diameter at

the level of the renal artery (minimum diameter about 30 mm) [27]. Smoking status

was categorized as current (daily or at least monthly smoking), former (ceased

smoking for at least one month), or never smoked [28]. Hypertension was

identified as a systolic blood pressure

Peripheral venous blood samples were collected from all participants after overnight fasting. Standard laboratory techniques were used to measure creatinine, estimated glomerular filtration rate (eGFR), TG, TC, HDL-C, LDL-C, FBG, HbA1c, troponin I (TnI), N-terminal pro-brain natriuretic peptide (NT-pro BNP), and D-Dimer. These were performed using the HITACHI 912 Analyzer (Roche Diagnostics, Mannheim, Germany) in the Clinical Laboratory, Ruijin Hospital. Standard echocardiography (Vivid E95, GE Healthcare, Chicago, IL, USA) was performed within 72 h of admission, and left ventricular ejection fraction (LVEF) was calculated using the biplane modified Simpson’s method.

Blood samples were transferred immediately into pyrogen-free tubes, centrifuged

immediately at 1500 r/min for 15 min at 4 °C, and then stored in aliquots at –80

°C until analysis. Serum levels of soluble TREM-1 (sTREM-1) and sTREM-2 were

determined with commercially available enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA)

kits according to standardized protocols (human TREM-1 duoset, DY1278B, R&D

System, Minneapolis, MN, USA; human TREM-2 duoset, DY1828-05, R&D System,

Minneapolis, MN, USA). Human HMGB1 matched antibody pair (H00003146-AP41) and

human HMGB2 monoclonal antibody (H00003148-M03) were both purchased from Abnova

Corporation (Taipei, Taiwan), while polyclonal HMGB2 antibody (H9789) was

purchased from Sigma-Aldrich (St Louis, MO, USA). The serum levels of HMGB1 and

HMGB2 were determined by sandwich ELISA as described previously by our laboratory

[18, 19]. Briefly, for the evaluation of HMGB2, biotinylated monoclonal anti-HMGB2

antibody (H00003148-M03) was incubated in streptavidin-coated and blocked wells

for 1 h and then washed. Serum samples or HMGB2 calibrator standards were diluted

in 100 µL assay buffer containing 50 mM sodium phosphate (pH 7.4), 0.5%

bovine serum albumin (BSA), 5 mM ethylenediaminetetraacetic acid (EDTA), and

0.001% aprotinin. This mixture was placed into the wells and incubated at room

temperature for 1 h. After washing, the captured HMGB2 molecules were identified

using a polyclonal HMGB2 antibody (H9789) diluted 1:5000 in 50 mM sodium

phosphate buffer that included 0.5% BSA and 1% normal goat serum (NGS).

Following 1 h incubation, the reagents that were not fixed were removed and goat

anti-rabbit IgG-horseradish peroxidase compound (GAR-HRP) was added. After

incubation for 30 minutes, the wells were washed and HRP substrate was added. The

color reaction was stopped after 15 minutes by adding 100 µL of 1N H₂SO₄,

and the absorbance measured at 450 nm with 620 nm. Each sample underwent

triplicate analysis. The methodology for HMGB1 detection was the same as for

HMGB2, and hence additional details are not included here. The detection limits

for sTREM-1, sTREM-2, HMGB1, and HMGB2 were 93.8–6000 pg/mL, 46.9–3000 pg/mL,

1.250–80 ng/mL, and 0.625–40 ng/mL, respectively. The inter-assay coefficient

of variation for all tests was

The serum HMGB1, HMGB2, sTREM-1 and sTREM-2 quartile cutoff values (25th, 50th, 75th percentiles, respectively) calculated for all participants were: HMGB1 (3.54, 4.35, 7.23 ng/mL), HMGB2 (1.25, 2.02, 5.83 ng/mL), sTREM-1 (143.54, 192.71, 272.12 pg/mL) and sTREM-2 (194.21, 329.82, 462.26 pg/mL). The cutoff values for HMGB2 in the AAA group were 1.35, 4.36, and 9.97 ng/mL, respectively.

Statistical analyses were conducted using SPSS 25.0 (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL,

USA) and R software Version 4.3.2 (R Foundation for Statistical Computing,

Vienna, Austria), with GraphPad Prism Version10.1.2 (GraphPad Software Inc., La

Jolla, CA, USA) used for mapping. The normality test was applied using the

Shapiro-Wilk method and Kolmogorov-Smirnov test. Missing values and outliers were

filled with mean or median values. Normally distributed continuous variables were

expressed as the mean

A total of 77 male subjects (average age: 61.16

| Control group (N = 41) | AAA group (N = 36) | p | |

| Age (years) | 59.41 |

63.14 |

0.144 |

| Current smoker (n, %) | 6 (14.63%) | 18 (50.00%) | |

| Former smoker (n, %) | 11 (26.83%) | 5 (13.89%) | 0.163 |

| Never smoked (n, %) | 24 (58.54%) | 13 (36.11%) | 0.049 |

| Hypertension (n, %) | 19 (46.34%) | 28 (77.78%) | 0.005 |

| Hyperlipidemia (n, %) | 10 (24.39%) | 6 (16.67%) | 0.405 |

| Statins (n, %) | 8 (19.51%) | 1 (2.78%) | 0.023 |

| Diabetes (n, %) | 11 (26.83%) | 3 (8.33%) | 0.036 |

| Systolic blood pressure (mmHg) | 130.15 |

129.94 |

0.966 |

| Diastolic blood pressure (mmHg) | 72.00 (65.00, 78.00) | 72.00 (63.75, 85.50) | 0.931 |

| Heart rate (bpm) | 78.00 (72.00, 88.00) | 78.00 (68.00, 84.25) | 0.292 |

| HMGB1 (ng/mL) | 4.01 (3.56, 5.02) | 6.12 (3.54, 11.74) | 0.020 |

| HMGB2 (ng/mL) | 1.51 (1.17, 2.60) | 4.36 (1.43, 9.69) | 0.002 |

| sTREM-1 (pg/mL) | 231.62 (160.80, 299.60) | 176.14 (122.22, 228.87) | 0.008 |

| sTREM-2 (pg/mL) | 337.28 (238.55, 485.37) | 249.22 (160.72, 407.76) | 0.067 |

| sTREM-1/sTREM-2 | 0.63 (0.44, 0.82) | 0.56 (0.40, 1.25) | 0.959 |

| eGFR (mL·min–1·1.73 m–2) | 95.24 |

80.61 |

0.006 |

| TG (mmol/L) | 1.29 (0.93, 2.02) | 1.06 (0.75, 1.40) | 0.042 |

| TC (mmol/L) | 4.47 |

3.93 |

0.026 |

| HDL-C (mmol/L) | 1.09 (0.96, 1.34) | 1.06 (0.91, 1.21) | 0.358 |

| LDL-C (mmol/L) | 2.66 |

2.41 |

0.181 |

| FBG (mmol/L) | 5.48 (4.97, 5.88) | 5.30 (4.88, 5.93) | 0.472 |

| HbA1c (%) | 5.80 (5.50, 6.20) | 5.50 (5.20, 5.90) | 0.024 |

| TnI (ng/mL) | 0.01 (0.01, 0.01) | 0.01 (0.01, 0.07) | |

| NT-pro BNP (pg/mL) | 65.00 (43.50, 97.60) | 140.25 (81.53, 550.58) | |

| D-Dimer (mg/L) | 0.27 (0.19, 0.32) | 1.60 (0.47, 8.86) | |

| LVEF (%) | 68.00 (65.00, 71.00) | 67.00 (57.75, 70.00) | 0.089 |

Abbreviations: AAA, abdominal aortic aneurysm; HMGB1, high-mobility group box1; HMGB2, high-mobility group box2; sTREM-1, soluble triggering receptor expressed on myeloid cells-1; sTREM-2, soluble triggering receptor expressed on myeloid cells-2; eGFR, estimated glomerular filtration rate; TG, triglyceride; TC, total cholesterol; HDL-C, high-density lipoprotein cholesterol; LDL-C, low-density lipoprotein cholesterol; FBG, fasting blood glucose; HbA1c, glycosylated hemoglobin; TnI, troponin I; NT-pro BNP, N-terminal pro-brain natriuretic peptide; LVEF, left ventricular ejection fraction.

The overall patient cohort was divided into four groups according to HMGB2

quartiles: group A, HMGB2

| A (N = 19) | B (N = 19) | C (N = 20) | D (N = 19) | p | |

| HMGB1 (ng/mL) | 3.28 (2.99, 3.78) | 3.82 (3.25, 4.44)* | 4.97 (3.69, 6.32)*# | 12.32 (9.45, 21.14)*#@ | |

| sTREM-1 (pg/mL) | 152.9 (105.18, 210.19) | 177.48 (142.86, 231.62) | 279.04 (217.30, 403.24)*# | 181.06 (154.68, 275.66)@ | |

| sTREM-2 (pg/mL) | 302.37 (192.53, 359.17) | 235.52 (152.65, 430.49) | 398.22 (227.61, 903.03)* | 361.58 (198.12, 463.59) | 0.115 |

| sTREM-1/sTREM-2 | 0.54 (0.47, 0.82) | 0.75 (0.44, 1.22) | 0.54 (0.38, 1.42) | 0.50 (0.35, 0.76) | 0.694 |

| Prevalence of AAA (n (%)) | 7 (36.84) | 6 (31.58) | 8 (40.00) | 15 (78.95)*#@ | 0.013 |

Compared to group A: *p

Abbreviations: AAA, abdominal aortic aneurysm; HMGB1, high-mobility group box1; HMGB2, high-mobility group box2; sTREM-1, soluble triggering receptor expressed on myeloid cells-1; sTREM-2, soluble triggering receptor expressed on myeloid cells-2.

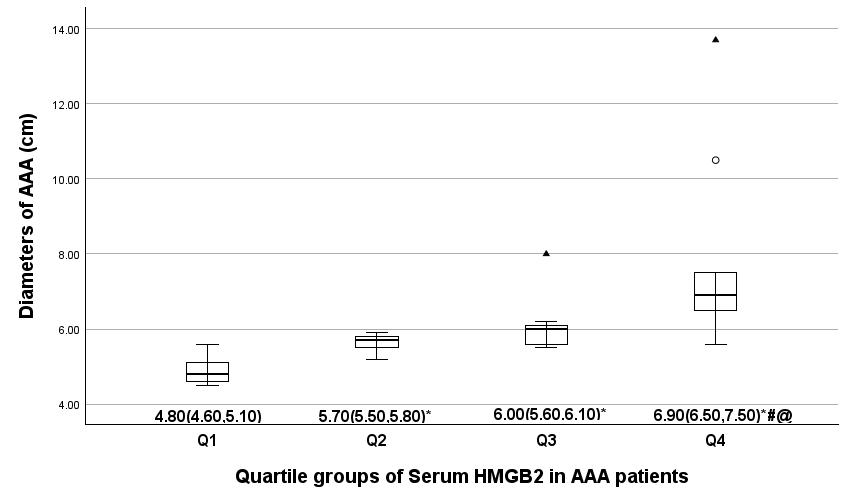

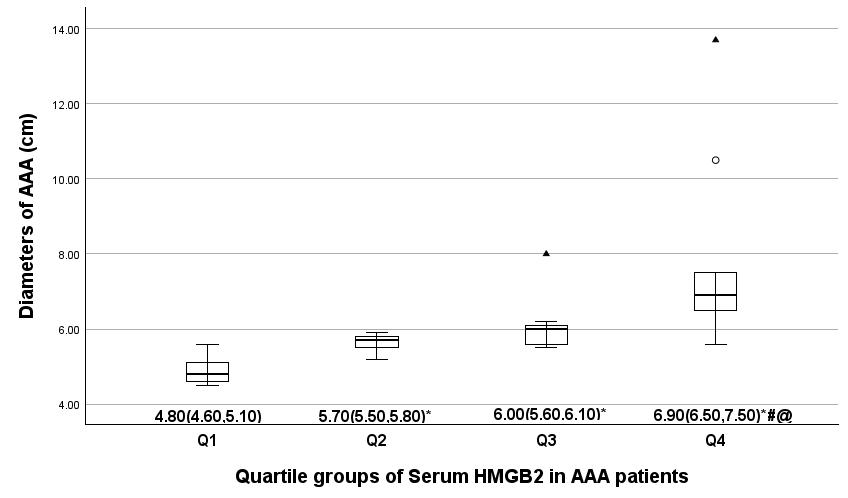

The AAA patient cohort was divided into four groups based on the HMGB2

quartiles: group Q1, HMGB2

Fig. 1.

Fig. 1.

Comparison of the AAA diameter in serum HMGB2 quartile groups.

The average AAA diameter in four serum HMGB2 quartile groups is indicated by

median (25th and 75th percentiles).

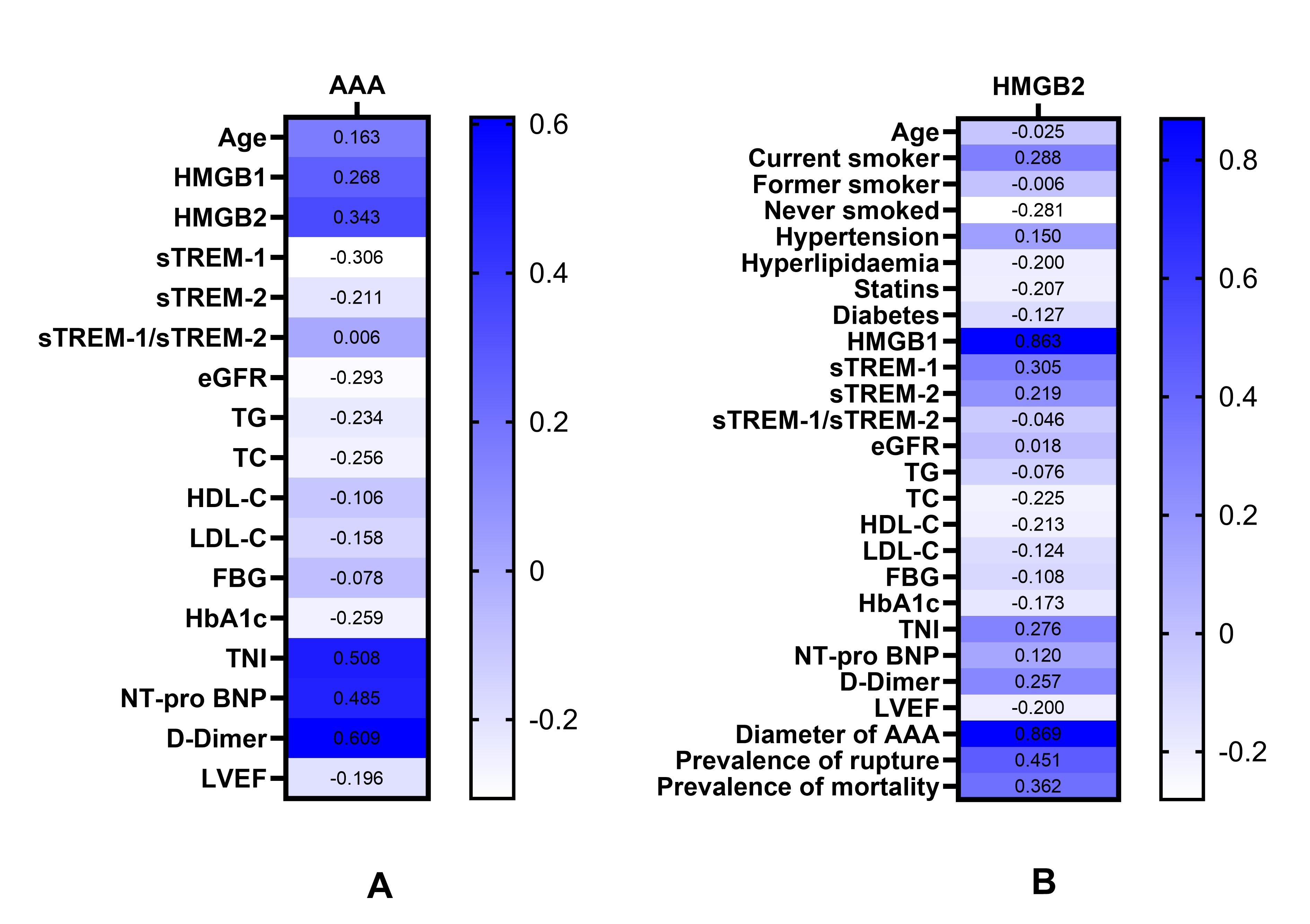

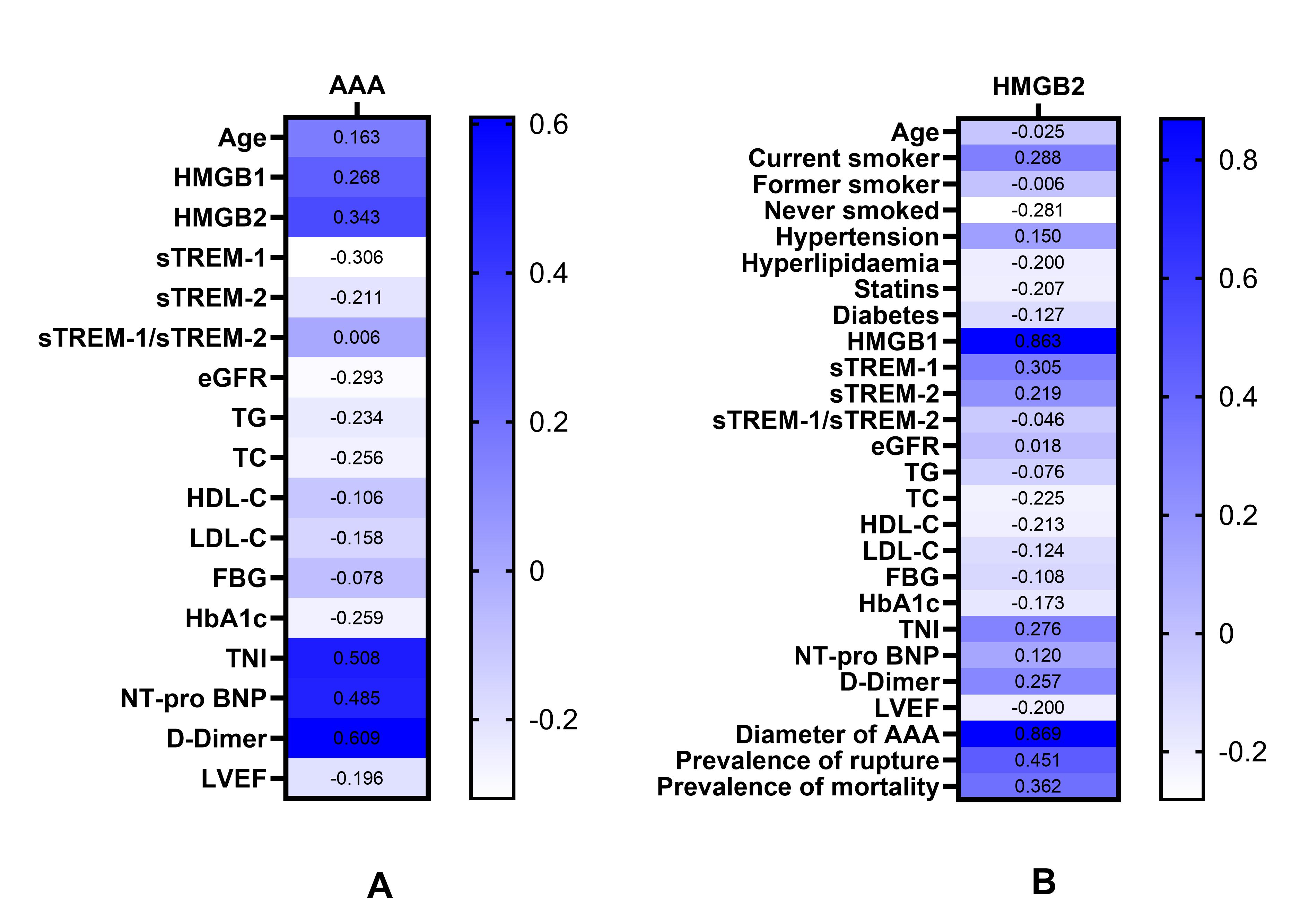

Spearman correlation analysis revealed that HMGB1, HMGB2, TnI, NT-pro BNP and

D-Dimer were positively correlated with the occurrence of AAA (p

| Variables | AAA | HMGB2 | ||

| r | p | r | p | |

| Age | 0.163 | 0.157 | –0.025 | 0.830 |

| Current smoker | / | / | 0.288 | 0.011 |

| Former smoker | / | / | –0.006 | 0.959 |

| Never smoked | / | / | –0.281 | 0.013 |

| Hypertension | / | / | 0.150 | 0.194 |

| Hyperlipidemia | / | / | –0.200 | 0.081 |

| Statins | / | / | –0.207 | 0.070 |

| Diabetes | / | / | –0.127 | 0.270 |

| HMGB1 | 0.268 | 0.018 | 0.863 | |

| HMGB2 | 0.343 | 0.002 | / | / |

| sTREM-1 | –0.306 | 0.007 | 0.305 | 0.007 |

| sTREM-2 | –0.211 | 0.066 | 0.219 | 0.055 |

| sTREM-1/sTREM-2 | 0.006 | 0.956 | –0.046 | 0.694 |

| eGFR | –0.293 | 0.010 | 0.018 | 0.875 |

| TG | –0.234 | 0.041 | –0.076 | 0.509 |

| TC | –0.256 | 0.025 | –0.225 | 0.049 |

| HDL-C | –0.106 | 0.359 | –0.213 | 0.063 |

| LDL-C | –0.158 | 0.171 | –0.124 | 0.281 |

| FBG | –0.078 | 0.578 | –0.108 | 0.440 |

| HbA1c | –0.259 | 0.023 | –0.173 | 0.133 |

| TnI | 0.508 | 0.276 | 0.015 | |

| NT-pro BNP | 0.485 | 0.120 | 0.301 | |

| D-Dimer | 0.609 | 0.257 | 0.026 | |

| LVEF | –0.196 | 0.088 | –0.200 | 0.081 |

| Diameter of AAA | / | / | 0.869 | |

| Prevalence of rupture | / | / | 0.451 | 0.006 |

| Prevalence of mortality | / | / | 0.362 | 0.030 |

Abbreviations: AAA, abdominal aortic aneurysm; HMGB1, high-mobility group box1; HMGB2, high-mobility group box2; sTREM-1, soluble triggering receptor expressed on myeloid cells-1; sTREM-2, soluble triggering receptor expressed on myeloid cells-2; eGFR, estimated glomerular filtration rate; TG, triglyceride; TC, total cholesterol; HDL-C, high-density lipoprotein cholesterol; LDL-C, low-density lipoprotein cholesterol; FBG, fasting blood glucose; HbA1c, glycosylated hemoglobin; TnI, troponin I; NT-pro BNP, N-terminal pro-brain natriuretic peptide; LVEF, left ventricular ejection fraction.

Fig. 2.

Fig. 2.

Heat map: Correlations of various parameters with AAA and with the levels of serum HMGB2. (A) Correlations of various parameters with the occurrence of AAA. (B) Correlations of various parameters with serum HMGB2 levels. Abbreviations: AAA, abdominal aortic aneurysm; HMGB1, high-mobility group box1; HMGB2, high-mobility group box2; sTREM-1, soluble triggering receptor expressed on myeloid cells-1; sTREM-2, soluble triggering receptor expressed on myeloid cells-2; eGFR, estimated glomerular filtration rate; TG, triglyceride; TC, total cholesterol; HDL-C, high-density lipoprotein cholesterol; LDL-C, low-density lipoprotein cholesterol; FBG, fasting blood glucose; HbA1c, glycosylated hemoglobin; TnI, troponin I; NT-pro BNP, N-terminal pro-brain natriuretic peptide; LVEF, left ventricular ejection fraction.

Pearson or Spearman correlation analysis showed that current smoking, HMGB1,

sTREM-1, TnI, D-Dimer, AAA diameter, prevalence of rupture, and mortality were

positively correlated with serum HMGB2 levels, whereas never smoked and TC were

negatively correlated with serum HMGB2 levels (p

Univariate logistic regression analysis identified current smoking and

hypertension as independent risk factors for AAA, while statin use and a history

of diabetes were protective (p

| p | OR | 95% CI | |||

| Lower | Upper | ||||

| Age | 0.141 | 1.032 | 0.990 | 1.077 | |

| Current smoker | 0.001 | 5.833 | 1.971 | 17.260 | |

| Former smoker | 0.251 | 0.500 | 0.153 | 1.633 | |

| Never smoked | 0.051 | 0.400 | 0.159 | 1.006 | |

| Hypertension | 0.006 | 4.053 | 1.495 | 10.984 | |

| Hyperlipidemia | 0.407 | 0.620 | 0.200 | 1.919 | |

| Statins | 0.049 | 0.118 | 0.014 | 0.994 | |

| Diabetes | 0.046 | 0.248 | 0.063 | 0.975 | |

| HMGB1 | |||||

| Model 1 | 0.004 | 1.262 | 1.079 | 1.476 | |

| Model 2 | 0.005 | 1.248 | 1.070 | 1.455 | |

| Model 3 | 0.015 | 1.275 | 1.048 | 1.551 | |

| HMGB2 | |||||

| Model 1 | 0.007 | 1.185 | 1.049 | 1.339 | |

| Model 2 | 0.009 | 1.173 | 1.041 | 1.322 | |

| Model 3 | 0.034 | 1.158 | 1.011 | 1.325 | |

| sTREM-1 | |||||

| Model 1 | 0.027 | 0.994 | 0.989 | 0.999 | |

| Model 2 | 0.012 | 0.993 | 0.987 | 0.998 | |

| Model 3 | 0.005 | 0.991 | 0.985 | 0.997 | |

| sTREM-2 | |||||

| Model 1 | 0.681 | 0.9998 | 0.9990 | 1.0007 | |

| Model 2 | 0.455 | 0.9997 | 0.9988 | 1.0005 | |

| Model 3 | 0.417 | 0.9996 | 0.9987 | 1.0005 | |

| sTREM-1/sTREM-2 | |||||

| Model 1 | 0.542 | 1.325 | 0.536 | 3.273 | |

| Model 2 | 0.401 | 1.490 | 0.588 | 3.778 | |

| Model 3 | 0.371 | 1.619 | 0.563 | 4.660 | |

| Quartiles of HMGB1 | 0.006 | ||||

| 1st quartile | / | 1 | / | / | |

| 2nd quartile | 0.138 | 0.254 | 0.042 | 1.551 | |

| 3rd quartile | 0.410 | 0.518 | 0.108 | 2.477 | |

| 4th quartile | 0.027 | 8.621 | 1.278 | 58.145 | |

| Quartiles of HMGB2 | 0.040 | ||||

| 1st quartile | / | 1 | / | / | |

| 2nd quartile | 0.829 | 0.828 | 0.150 | 4.563 | |

| 3rd quartile | 0.560 | 0.609 | 0.115 | 3.232 | |

| 4th quartile | 0.045 | 6.925 | 1.045 | 45.895 | |

| Quartiles of sTREM-1 | 0.008 | ||||

| 1st quartile | / | 1 | / | / | |

| 2nd quartile | 0.621 | 0.643 | 0.112 | 3.698 | |

| 3rd quartile | 0.313 | 0.398 | 0.067 | 2.377 | |

| 4th quartile | 0.001 | 0.029 | 0.004 | 0.240 | |

Univariable model: each smoking status was analyzed independently (current, former, never). sTREM-2: full-precision ORs and CIs for sTERM-2 are provided in 4 decimal places.

Model 1: adjusted for age; Model 2: further adjusted (from Model 1) for history of smoking; Model 3: further adjusted (from Model 2) for hypertension, hyperlipidemia, statin use and diabetes.

Abbreviations: AAA, abdominal aortic aneurysm; HMGB1, high-mobility group box1; HMGB2, high-mobility group box2; sTREM-1, soluble triggering receptor expressed on myeloid cells-1; sTREM-2, soluble triggering receptor expressed on myeloid cells-2.

| Variable | p | Firth-Corrected OR | 95% CI | ||

| Lower | Upper | ||||

| Age | 0.142 | 1.031 | 0.990 | 1.077 | |

| Current smoker | 0.001 | 5.458 | 1.978 | 16.727 | |

| Former smoker | 0.259 | 0.524 | 0.156 | 1.598 | |

| Never smoked | 0.051 | 0.411 | 0.162 | 1.005 | |

| Hypertension | 0.005 | 3.861 | 1.496 | 10.720 | |

| Hyperlipidemia | 0.420 | 0.640 | 0.204 | 1.887 | |

| Statins | 0.023 | 0.166 | 0.017 | 0.801 | |

| Diabetes | 0.038 | 0.278 | 0.065 | 0.932 | |

| Model 3 | |||||

| HMGB1 | 0.003 | 1.214 | 1.057 | 1.508 | |

| HMGB2 | 0.012 | 1.121 | 1.020 | 1.303 | |

| sTREM-1 | 0.002 | 0.993 | 0.987 | 0.998 | |

| sTREM-2 | 0.426 | 1.000 | 0.999 | 1.000 | |

| sTREM-1/sTREM-2 | 0.377 | 1.556 | 0.573 | 4.212 | |

Univariable model: each smoking status was analyzed independently (current, former, never).

Model 3: all multivariable logistic regression models were tested separately for each biomarker of interest (HMGB2, HMGB1, sTREM-1, sTREM-2, and the sTREM-1/sTREM-2 ratio) in relation to the increased risk of AAA and adjusted for age, smoking history, hypertension, hyperlipidemia, statin use, and diabetes.

Abbreviations: AAA, abdominal aortic aneurysm; HMGB1, high-mobility group box1; HMGB2, high-mobility group box2; sTREM-1, soluble triggering receptor expressed on myeloid cells-1; sTREM-2, soluble triggering receptor expressed on myeloid cells-2.

Following adjustment for age, smoking history, hypertension, hyperlipidemia,

statin use and diabetes, the serum levels of HMGB1 (OR: 1.212, 95% CI:

1.003–1.465, p

| Variable | p | OR | 95% CI | p | Firth-Corrected OR | 95% CI | ||

| Lower | Upper | Lower | Upper | |||||

| HMGB1 | 0.046 | 1.212 | 1.003 | 1.465 | 0.028 | 1.152 | 1.015 | 1.390 |

| HMGB2 | 0.041 | 1.117 | 1.005 | 1.241 | 0.030 | 1.089 | 1.008 | 1.207 |

All multivariable logistic regression models were tested separately for each biomarker of interest (HMGB2, HMGB1) in relation to the increased risk of AAA rupture and adjusted for age, smoking history, hypertension, hyperlipidemia, statin use, and diabetes.

Abbreviations: AAA, abdominal aortic aneurysm; HMGB1, high-mobility group box1; HMGB2, high-mobility group box2.

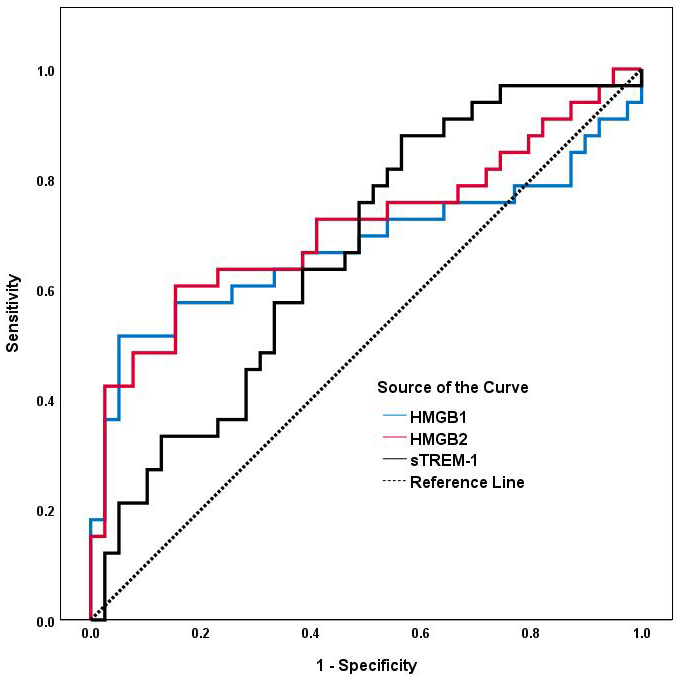

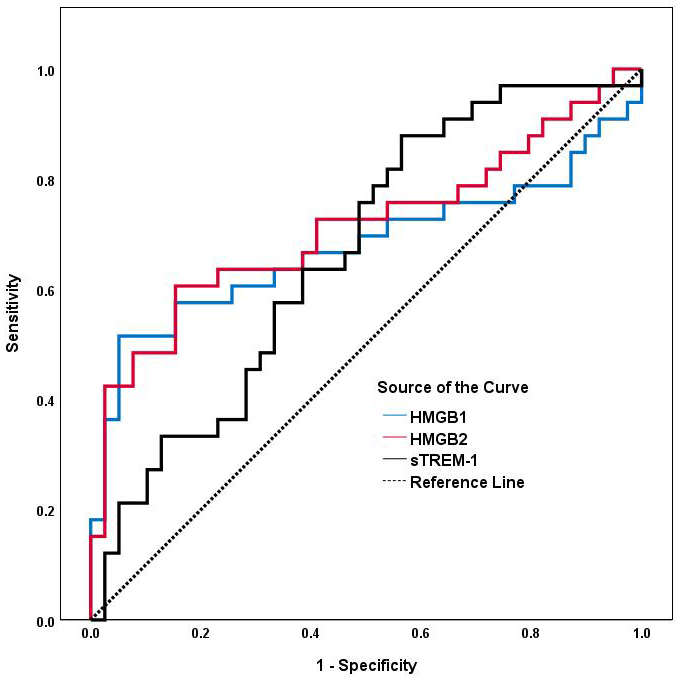

As shown in Table 7 and Fig. 3, an HMGB2 cut-off level of 3.110 ng/mL

discriminated AAA patients from controls with a sensitivity of 60.6% and

specificity of 84.6% (AUC: 0.713, 95% CI: 0.588–0.839; p

Fig. 3.

Fig. 3.

ROC analyses of serum HMGB1, HMGB2 and sTREM-1 for predicting AAA. The area under the ROC curve for HMGB1, HMGB2 and sTREM-1 is shown for the prediction of AAA. Abbreviations: ROC, receiver operating characteristic; AUC, area under the ROC curve; AAA, abdominal aortic aneurysm; HMGB1, high-mobility group box1; HMGB2, high-mobility group box2; sTREM-1, soluble triggering receptor expressed on myeloid cells-1.

| Variable | AUC (95% CI) | p | Cut-off | Sensitivity | Specificity |

| HMGB2 (ng/mL) | 0.713 (0.588–0.839) | 0.001 | 3.110 | 0.606 | 0.846 |

| HMGB1 (ng/mL) | 0.677 (0.541–0.813) | 0.011 | 6.699 | 0.515 | 0.949 |

| sTREM-1 (pg/mL) | 0.665 (0.540–0.790) | 0.016 | 259.289 | 0.889 | 0.439 |

Abbreviations: ROC, receiver operating characteristic; AUC, area under the ROC curve; AAA, abdominal aortic aneurysm; HMGB1, high-mobility group box1; HMGB2, high-mobility group box2; sTREM-1, soluble triggering receptor expressed on myeloid cells-1.

AAA is associated with a high mortality rate following aortic rupture and with severe effects on human health [32]. No specific biomarkers or effective drugs are currently available for the prevention, early identification and treatment of AAA [33]. Substantial evidence indicates that chronic inflammation and dysregulation of the ECM are key factors in the development of AAA, thus presenting a possible therapeutic strategy for controlling its progression [34]. Our study found that elevated serum HMGB2 and HMGB1 levels were both independently associated with the incidence and rupture of AAA in males. The Firth-corrected estimates aligned closely with the results from multiple logistic regression, demonstrating the robustness of the significant associations observed in the standard analysis. Compared to the first quartile of serum HMGB2 and HMGB1 levels, the odds ratio for AAA in the fourth quartile were increased by 6.92-fold and 8.62-fold, respectively. We also found that decreased levels of sTREM-1 were significantly associated with an increased risk of AAA. Moreover, sTREM-1 was positively correlated with serum HMGB2 levels, especially in the lower three HMGB2 quartiles, indicating that disruption of the HMGB2-TREM pathway may play a critical role in the pathogenesis of AAA.

HMGB1 is expressed in inflammatory cells, VSMCs, and endothelial cells, with

previous studies also showing high abundance in human AAA lesions [13, 35, 36, 37].

Blocking HMGB1 with antibodies reduces pro-inflammatory cytokines and

proteinases, and inhibits CaCl2-induced AAA formation [13]. The current

evidence suggests that HMGB1 activation of TLR4 amplifies TLR4 signaling, thereby

promoting the release of interleukin (IL) 6 and monocyte chemoattractant

protein-1 (MCP-1) from VSMCs and contributing to AAA formation and progression

[14]. TLRs and HMGB1 can also induce signaling cascades via RAGE [15]. The

HMGB1-RAGE signaling pathway is essential for maintaining chronic inflammation

during the development of AAA [16]. Our study also found that serum HMGB1 levels

are independently associated with a higher risk of AAA, confirming findings from

previous research. However, information on the role of HMGB2 in AAA is still

limited. Previous studies have shown that it is important for both the

development of atherosclerosis and coronary artery in-stent restenosis by

promoting neointimal hyperplasia in mice with femoral artery injury, and for the

proliferation and migration of VSMCs [19, 38]. HMGB2 exacerbates myocardial

ischemic injury via reactive oxygen species (ROS)-mediated apoptosis, aberrant

autophagy, and the inflammatory response [18]. Wu et al. [20] observed

increased HMGB2 levels in an angiotensin II-induced mouse model of AAA. Moreover,

these authors reported that a potential therapeutic strategy for AAA may be the

inhibition of HMGB2-regulated ferroptosis and inflammation in

angiotensin-II-treated VSMCs through inactivation of NF-

Our study found a correlation between low serum sTREM-1 levels and the

occurrence of AAA, suggesting that it may offer protection against AAA. Our

results contrast to those of Vandestienne et al. [23], who reported

elevated TREM1 mRNA expression in human aortic aneurysm tissues, and

increased serum sTREM-1 levels in AAA patients. Their research indicated that

TREM-1 could control angiotensin II-induced monocyte activity and promote

experimental AAA. The reasons for the discrepancies between their results and the

current findings are unclear, but may be attributable to several factors. First,

Gibot et al. [40] reported that non-survivors exhibited reduced sTREM-1

levels on the first day after admission compared to survivors. sTREM-1 plasma

concentrations in non-survivors remained stable or increased over time, but

decreased in survivors, indicating that a high baseline sTREM-1 level is an

independent protective factor in severe inflammatory conditions. Only the

baseline level of sTREM-1 was assessed in our study, and hence any potential

changes that occur subsequently require investigation at later follow-up times.

Second, Giamarellos-Bourboulis et al. [41] reported that sTREM-1

functions as an anti-inflammatory mediator in sepsis, as evidenced by its

positive correlations and similar kinetics with the anti-inflammatory cytokine

IL-10. A decreased sTREM-1/tumor necrosis factor (TNF) ratio may promote the

progression from sepsis to severe sepsis, and potentially to septic shock. Dai

et al. [42] found that sTREM-1 plays a protective role in endothelial

inflammation by inhibiting the expression of IL-1b, IL-6, TNF-

Previous studies have confirmed that HMGB1 is one of the ligands for TREM-1 [25, 45, 46]. However, the relationship between HMGB2 and TREM-1 and the potential involvement of the HMGB2-TREM pathway in the pathogenesis of AAA has not been previously reported. The present findings indicate that sTREM-1 is positively correlated with HMGB2. Analysis of quartile groups based on HMGB2 levels revealed that serum sTREM-1 levels increased significantly in a concentration-dependent manner as the HMGB2 levels rose more moderately. Interestingly, a statistically significant decrease in the serum sTREM-1 level was observed in the upper quartile group of HMGB2. While sTREM-1 generally correlates positively with HMGB2, we hypothesize that there is a critical threshold beyond which this relationship inverts. Our analyses revealed a biphasic relationship between HMGB2 and sTREM-1 levels. Previous studies have also reported on the role of TREM-1 in amplifying the inflammatory response [47, 48]. We hypothesize that TREM-1 mediates the activation of its ligands, such as HMGB2, as well as inflammatory cell receptors (RAGE, TLR-4 and TLR-2), thereby initiating downstream signaling pathways that ultimately lead to AAA. The release of sTREM-1 depends on the activation and cleavage of mTREM-1 [43]. A mild to moderate increase in HMGB2 can stimulate sTREM-1 production, which acts as a decoy receptor and antagonist to mTREM-1, thus conferring anti-inflammatory properties. However, a negative feedback regulation between HMGB2 and sTREM-1 occurs when HMGB2 is highly expressed, thereby reducing its anti-inflammatory effect and contributing to the development of AAA. TREM-2 serves as a negative regulator of the inflammatory response [49]. Nonetheless, we did not observe any significant associations between sTREM-2 and AAA or HMGB2 in the current study.

Our findings indicate that current smoking and hypertension are independent risk factors for AAA, whereas the use of statins and the presence of diabetes confer protection against AAA, consistent with previous research. There is substantial evidence that smoking is a significant risk factor for AAA, with current smokers exhibiting a 5-fold increased risk and former smokers a 2-fold increase risk compared to individuals who have never smoked. Furthermore, a positive dose-response relationship was observed between the daily quantity of cigarettes smoked and the risk of developing AAA, as well as cumulative pack-years smoked and risk of AAA [50]. Although our study did not identify a significant association between hyperlipidemia and AAA, a negative correlation was observed between statin use and the incidence of AAA. Multiple Mendelian randomization analyses have implicated elevated LDL-C and reduced HDL-C levels as contributing factors to the pathogenesis of AAA [51]. Specifically, small dense LDL shows a strong association with AAA [3]. Despite these associations, there is no evidence that dyslipidemia is associated with the risk of AAA growth or rupture [52]. Several studies suggest that most statins can decrease or prevent AAA progression through various mechanisms, including regulation of endoplasmic reticulum stress, antioxidant activity, ECM synthesis, and inhibition of matrix-metalloproteinase (MMP) [53]. The increased use of statins among hyperlipidemic patients in the control group of our study may account for the observed lack of association between hyperlipidemia and AAA. Our study found a negative correlation between diabetes and AAA, consistent with results from previous research. The relationship between diabetes and a slower rate of AAA growth is well-documented [54]. However, it remains uncertain whether this effect is attributable to the diabetes itself, or to pharmacological treatments associated with its condition. In this regard, metformin, a widely used diabetes medication, has been found to mitigate matrix remodeling and inflammation in AAA [55]. The patient cohort in our study included individuals with hyperlipidemia, diabetes, or hypertension. Relevant pharmacological agents were administered during the study to treat these conditions, which may have influenced the observed outcomes.

This research has several limitations. First, it was a preliminary, retrospective, and cross-sectional study aimed at investigating the relationship between the HMGB2-TREM pathway and AAA from an inflammatory perspective. The association between the HMGB2-TREM pathway and AAA is still not fully elucidated and warrants further research. Second, we conducted a single-center, small-scale cohort study comprised of male participants only to eliminate possible sex-related confounders. The small sample size reduced the statistical power, increased the risk of Type II errors, and limited the subgroup analyses. The single-center design also introduces potential selection bias, as the study cohort may not accurately represent all populations. The exclusion of female participants, while intended to control for sex-specific confounders, prevents extrapolation of the findings to women, who exhibit distinct AAA risk profiles and pathophysiological mechanisms. In the quartile-based regression analysis, the wide confidence intervals observed for the 4th quartile of HMGB1 and HMGB2 are likely because of the small sample size of these subgroups, thus reducing the estimate precision. While point estimates suggest a strong association, the broad intervals indicate uncertainty and warrant a cautious interpretation. However, the consistent and statistically significant trend seen across quartiles supports the robustness of our findings. Due to corona virus disease 2019 (COVID-19), this study experienced difficulties with the recruitment of patients, further restricting sample diversity and potentially skewing the results toward individuals with more severe or accessible AAA cases. Additionally, only the baseline level of HMGB2 was assessed in our study. It remains to be determined whether subsequent changes in this level during follow-up could mask its role as a prognostic biomarker for the growth, rupture, or repair of AAA. Finally, our study did not investigate the mechanistic and pathological roles of the HMGB2-TREM pathway in AAA.

Given the limitations of our study, there are many issues concerning AAA that still need to be addressed in future research work. One major issue is the uncertain pathological mechanism of AAA. Further in vitro and in vivo experiments are needed to elucidate the mechanistic and pathological roles of the HMGB2-TREM pathway in AAA. These should focus on the impact of this pathway on inflammatory responses, VSMC apoptosis, and ECM degradation. Various AAA animal models and gene knockout or overexpression models could also be used to study the role of the HMGB2-TREM pathway on AAA development. The second major issue to be addressed is the difficulty of early diagnosis. To explore the potential of HMGB2 as a biomarker for the early diagnosis and prognostic assessment of AAA, dynamic changes in the serum level of HMGB2 in relation to AAA progression should be evaluated. The third issue to be addressed is the lack of effective treatment. This requires screening and development of small molecule inhibitors or agonists targeting the HMGB2-TREM pathway, followed by an evaluation of their efficacy for the prevention and treatment of AAA. Early-stage clinical trials that assess the safety and efficacy of HMGB2-TREM pathway-targeted therapies in human patients will be required. These efforts should help to identify specific biomarkers and therapeutic strategies for the early diagnosis, prognosis, and treatment of AAA patients.

In conclusion, elevated serum HMGB2 levels are independently associated with the incidence of AAA. Disruption of the HMGB2-TREM pathway may have a significant impact on the pathogenesis of AAA. The HMGB2-TREM pathway therefore represents a potentially novel therapeutic target for the treatment and prevention of AAA.

The data that support the findings of this study are not publicly available due to their containing information that could compromise subsequent unfinished research. The data of this study can not be disclosed until the results of the follow-up study are published.

LP and JC contributed equally to this work. LP contributed to data analyses and drafting of the manuscript. JC contributed to data collection and collation. YS was responsible for the supply of materials and samples. FW was responsible for the conception, design and supervision of the manuscript. All authors contributed to the conception and editorial changes in the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript. All authors have participated sufficiently in the work and agreed to be accountable for all aspects of the work.

All procedures were performed according to the principles of the Declaration of Helsinki and approved by the local Research and Ethics Committee of the Ruijin Hospital (ethical approval number: 2023 (No.70)). Informed written consent was obtained from all participants.

We would like to thank the data support of the cardiovascular surgery department of Ruijin Hospital and the team partners for their close cooperation.

This study was supported by Chinese National Nature Science Foundation (Grant no. 81900413), Hainan Provincial Health Commission (Grant no. 22A200174) and National Key Research and Development Program of China (Grant no. 2021YFC2500600, Grant no. 2021YFC2500602). Three-Year Action Plan for Promoting Clinical Skills and Clinical Innovation in Municipal Hospitals (SHDC2022CRS037). The funders had no role in the design, data collection, data analysis, and reporting of this study.

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

Publisher’s Note: IMR Press stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.