1 Department of Internal Medicine, Kirk Kerkorian School of Medicine at UNLV, Las Vegas, NV 89102, USA

2 VA Southern Nevada Healthcare System, North Las Vegas, NV 89086, USA

Abstract

Aortic regurgitation is a valvular disorder that necessitates the integration of multiple aspects of clinical practice. The underlying etiologies span an array of pathologies, including congenital, infectious, structural, and traumatic causes. Imaging studies range from traditional cardiac diagnostic strategies to advanced imaging modalities. Meanwhile, depending on clinical presentation, management may involve a medical or surgical approach. Long-term surveillance and chronic disease management are crucial in preventing progression into further complications, such as heart failure. This review aims to provide a thorough, comprehensive analysis of the contemporary understanding of aortic regurgitation. The information we have included will offer a unique perspective on how recent updates in diagnostic and management strategies can be applied to provide excellent patient care. Specifically, we have attempted to focus on exploring the innovations in the invasive management of aortic regurgitation.

Keywords

- aortic regurgitation

- imaging

- echocardiography

- magnetic resonance

- computed tomography

- aortography

- valve replacement

- surveillance

Aortic regurgitation (AR) is also known as aortic insufficiency and results from inadequate closure of the aortic valve leaflets. This promotes volume overload in the left ventricle, leading to subsequent deleterious effects. AR was first described by English surgeon and anatomist William Cowper in 1705 [1]. Meanwhile, the underlying mechanism stems from pathology at the aortic valve leaflets or the aortic root, meaning that as regurgitant blood flows retrograde from the aortic valve back to the left ventricle (LV) in diastole, the LV undergoes remodeling, eccentric hypertrophy, and dilatation. Often, this compensatory mechanism eventually reaches a limit, resulting in a decreased LV systolic function with a reduced LV ejection fraction (LVEF). AR can further manifest as symptoms such as dyspnea, angina, palpitations, presyncope, or syncope. Moreover, AR can progress into advanced diseases, such as elevated cardiac chamber pressures, myocardial ischemia, and decreased cardiac output. This review will explore the etiologies of AR and how imaging modalities can be utilized in diagnosis, risk stratification, surveillance, and intervention for patients with AR. This review also aims to analyze the indications for medical and surgical management and the postoperative surveillance of prosthetic valves.

The etiologies of AR encompass a wide range of pathological processes affecting the aortic valve leaflets, the aortic root, or both. These etiologies can be classified as valvular causes, aortic root causes, or combined etiologies as the primary drivers of pathophysiology. Thus, understanding the underlying cause of AR is critical for tailoring diagnostic and therapeutic strategies. Each major etiology of AR will be discussed in detail below and are summarized in Table 1.

| Aortic valve leaflet causes | Aortic root causes |

| Bicuspid aortic valve | Aortic root dilatation |

| Endocarditis | Aortic dissection |

| Rheumatic fever | Aortitis |

| Myxomatous degeneration | Connective tissue disease |

| Trauma | Trauma |

| Calcified aortic valve | Hypertension |

| Inflammatory/autoimmune | |

| Prosthetic valve dysfunction |

The most common congenital defect associated with AR is a bicuspid aortic valve (BAV) [2]. Compared to tricuspid aortic valves, BAVs induce turbulent blood flow patterns, causing higher levels of hemodynamic stress in the valves and the supporting structures [3]. Over time, the elevated hemodynamic stress predisposes the valve to fibrosis and calcification, eventually causing valve dysfunction. Indeed, patients with BAVs are at elevated risk of both aortic stenosis (AS) and AR, often at much younger ages.

In patients with BAVs and unequal leaflet sizes, one leaflet often has a midline raphe resulting from incomplete commissural separation during embryonic development. The orientations of the leaflets vary significantly among patients, with the most common BAV subtype involving fusion of the right and left (R–L) coronary leaflets (59% of cases) and the second most common subtype involving fusion of the right and noncoronary (R–N) leaflets (37% of cases) [4]. The BAV subtype is clinically significant, as the R–N fusion progresses faster than the R–L fusion in terms of both AS and AR, particularly in younger patients [5]. Approximately 32–43% of adults with BAVs develop significant AR, often accompanied by aortic root dilation, which increases the regurgitation volume and worsens the AR [6].

Additionally, the genetic basis of BAV is becoming increasingly recognized. BAVs are usually inherited in an autosomal dominant pattern but with incomplete penetrance and variable expressivity. Meanwhile, mutations in NOTCH1 and at least 25 other pathways have been implicated in the pathogenesis of BAVs [7, 8]. The systemic relevance of BAVs extends beyond the direct effects, whereby BAVs are also associated with syndromic conditions, such as Turner syndrome. The natural history of BAVs is highly variable, necessitating regular imaging surveillance to identify valvular or aortic disease progression.

Infective endocarditis (IE) is a critical cause of acute, subacute, and chronic AR. Bacterial and fungal pathogens adhere to the endocardium and valvular apparatus, creating an initial nidus [9]. Once the nidus is established, inflammatory cells and multiple cytokines initiate and mediate an inflammatory response with associated integrins, tissue factors, and adhesion molecules. The inflammatory response propagates, attracting monocytes and platelets, which leads to thrombus formation, creating a favorable environment for infectious pathogens to reside in, and finally, forming infected vegetation on the surface of the valve [10].

This vegetation can erode or perforate the leaflets, resulting in acute, severe

AR. Occasionally, leaflet rupturing can occur, precipitating an abrupt

hemodynamic collapse due to acute left ventricular volume overload [11]. In these

severe cases, IE causes low cardiac output, a significant rise in left

ventricular end-diastolic pressure (LVEDP), and cardiogenic shock [12]. The

clinical markers that highlight the level of severity of AR include increasing

heart rate (

Prompt diagnosis through echocardiography and blood cultures is essential, as untreated IE carries a high mortality rate. Research has shown that persons who inject drugs (PWID) present an elevated risk of recurrent IE, while fungal IE is more prevalent in second-episode endocarditis and associated with increased mortality [13]. Candida albicans is a common mycological pathogen that frequently contaminates illicit opioid drugs and, therefore, is the culprit of most fungal IE and potential valvular vegetations with fungal origins [13].

Rheumatic heart disease (RHD) due to rheumatic fever (RF) is most often caused by Streptococcus pyogenes (group A strep, GAS). However, substantial scientific evidence supports a rise in RHD cases involving group C and even group G streptococci [14]. Molecular mimicry has long been the accepted immunological pathway of RHD. Meanwhile, new evidence highlights the linkage between the streptococcal M-protein type 3 (M3-protein) and its interaction with the CB3-region in collagen type IV (CIV) [15]. Rheumatic fever can result in fibrotic changes to the aortic valve, which is usually a chronic phenomenon, leading to the classic finding of fusion of the aortic valve commissures. The fibrosed aortic valve cusps prevent proper forward cardiac flow, representing aortic stenosis associated with rheumatic fever. Likewise, these fibrosed aortic valve cusps prevent proper valve closure during diastole, which manifests as chronic aortic regurgitation. Mortality due to RHD presents a heavy burden, especially on low-income countries, with an annual reported mortality rate of 300,000 patients per year [16].

Myxomatous valve degeneration occurs when a native valve becomes fibrosed by depositing extracellular matrix components, such as glycosaminoglycans, and loses its intrinsic structural integrity. Recent research has shown a link between certain transcription factors and the risk of developing cardiac valve myxomatous degeneration [17]. If this valvular degeneration develops in the aortic valve, it can predispose patients to developing AR. In rare cases, cardiac myxomas can also contribute to AR; thus, prompt surgical intervention is warranted [18]. In the pediatric population, myxomatous degeneration of cardiac valves has been linked to genetic diseases such as trisomy 18, Noonan, Marfan, and Ehlers–Danlos syndrome, with a huge emphasis on the 6q25.1 gene deletion that expresses the transforming growth factor (TGF)-beta-activated kinase 1/mitogen-activated protein kinase kinase kinase 7 (MAP3K7)-binding protein 2 (TAB2 gene) protein [19].

AR, resulting from trauma, occurs due to direct damage to the valve apparatus, including cusp avulsion or annular disruption. Multiple case reports have described patients suffering from high-impact force attributed to motor vehicle collisions, mostly sustaining crushing chest injuries that have resulted in AR and eventual deterioration into cardiogenic shock [20, 21, 22]. These patients usually require emergent surgical intervention.

Thoracic aortic dissection (AD) is a critical cause of acute AR and should be considered in all patients presenting to the emergency department with acute chest or back pain. AD occurs when a tear in the intimal layer of the aortic wall allows blood to enter and “dissect” between the media layers, creating a false lumen. This disruption frequently extends to the aortic root, annulus, or commissures, leading to leaflet malcoaptation and acute, severe AR [23]. Clinical presentation often includes severe chest pain, described as a tearing or ripping sensation, which radiates to the back. Diagnosis is typically made using contrast-enhanced computed tomography (CT) angiography, which provides high-resolution images of the aorta. Transesophageal echocardiography (TEE) is another valuable tool, particularly in unstable patients, as it can assess both the aortic valve and dissection flap in real time [24]. Prompt diagnosis and localization of the dissection are crucial, since location assists with the classification of the dissection and guides management [25].

Cystic medial necrosis is a degenerative condition characterized by the

fragmentation of elastic fibers and the accumulation of the mucoid extracellular

matrix in the medial layer of the aortic wall. These changes weaken the

structural integrity of the aorta, predisposing it to dilation, aneurysm

formation, and dissection [26]. The pathophysiology of cystic medial necrosis is

linked to genetic mutations, particularly in fibrillin-1 (FBN1) in Marfan

syndrome and TGF-

Osteogenesis imperfecta (OI) is a genetic disorder resulting from gene mutations encoding type 1 collagen, COL1A1, and/or COL1A2. While OI primarily affects the skeleton, it also has significant cardiovascular implications due to the role of type I collagen in maintaining the structural integrity of the vascular wall, aortic root, and valve annulus; the aortic root is particularly vulnerable in OI [28]. Meanwhile, numerous studies have shown increased aortic root diameters in patients with OI, resulting in progressive dilation and AR over time [28, 29]. The severity of cardiovascular involvement varies with the type of OI, with moderate-to-severe forms (types III and IV) more commonly associated with aortic complications [29].

Long-standing, untreated hypertension may play a role in progressive aortic root dilatation [30, 31]. This may be due to continuous pressure overload, leading to accelerated vascular stiffening and loss of elastic fibers in the vasculature. Furthermore, endothelial dysfunction is a well-known risk factor for hypertension, and this may play a role in the pathogenic remodeling process. Collectively, these processes may result in greater annular stretching and degenerative valve changes, leading to the development and progression of AR [32].

Syphilitic aortitis represents a severe cardiovascular manifestation of tertiary syphilis, arising from chronic inflammation of the vasa vasorum. The small vessels that supply the outer layers of the aortic wall become inflamed, leading to obliterative endarteritis. This results in ischemic injury, medial necrosis, and fibrotic scarring, ultimately weakening the structural integrity of the ascending aorta [33]. Over time, these processes cause aortic root dilation and proper aortic valve leaflet coaptation failure, leading to progressive AR [34]. Syphilitic AR is often associated with ascending aortic aneurysms, which increase the complexity of management and contribute to significant morbidity.

Historically, syphilis was one of the leading causes of AR and valvular disease before the advent of antibiotics. The widespread use of penicillin and improved screening methods in the mid-20th century led to a dramatic decline in syphilis-related cardiovascular complications in developed countries. However, syphilitic aortitis and AR remain important concerns, particularly in resource-limited settings. Collectively, tertiary syphilis still occurs in 10–30% of untreated syphilis patients [35]. Among patients with tertiary syphilis, approximately 10–15% develop cardiovascular manifestations.

Functional AR results from left ventricular dilation that disrupts the normal mechanics of the aortic valve without primary valve disease. This condition is often seen in severe LV dysfunction cases caused by dilated cardiomyopathy, myocarditis, or ischemic heart disease [36]. In functional AR, the dilated LV pulls the aortic annulus apart, preventing complete coaptation of the valve leaflets during diastole. Additionally, aortic annular dilation is compounded by increased wall stress and remodeling, further exacerbating regurgitation [36]. Functional AR typically develops gradually and reflects the underlying disease progression in LV dilation. Symptoms are often overshadowed by those of heart failure, including exertional dyspnea, fatigue, and orthopnea. The regurgitant volume is frequently proportional to the degree of annular and ventricular enlargement; meanwhile, diagnosis relies on echocardiographic findings, which normally comprise LV dilatation, dilated cardiomyopathy, and aortic annulus dilatation [37].

Patients undergoing radiation therapy are at elevated risk of radiation-induced AR. Radiation damages the connective tissue and microvasculature of the aortic valve and ascending aorta, leading to fibrosis, scarring, and calcification. Over time, these changes can distort the valve anatomy, impair leaflet mobility, and cause AR [38]. Patients with radiation-induced AR often present decades after completing radiation therapy, with symptoms that mirror those of chronic AR. Therefore, diagnosis requires a high index of suspicion in patients with a history of mediastinal radiation. Notably, radiation damage often extends to surrounding cardiac structures, complicating the clinical presentation [39].

Ankylosing spondylitis, a chronic inflammatory disease primarily affecting the axial skeleton, can also involve the cardiovascular system and promote AR in some patients. Inflammatory changes in ankylosing spondylitis typically affect the aortic root and ascending aorta, leading to annular dilation, aortic wall thickening, and aortic valve leaflet fibrosis. These changes impair leaflet coaptation, resulting in progressive AR. Studies suggest that approximately 2–10% of patients with ankylosing spondylitis develop significant AR, with a higher prevalence observed in patients with long-standing or severe disease [40]. Imaging studies, including echocardiography, are essential for evaluating AR severity, while MRI may be used to assess spinal or joint involvement [41].

The clinical presentation of AR can vary depending on the chronicity of the disease and the disease severity. Acute AR is a critical medical condition that demands prompt identification and intervention to avert rapid deterioration, including death. Comparatively, chronic AR can remain asymptomatic for decades as the LV adapts to the regurgitant volume before these compensatory mechanisms fail. The presentations of both chronic and acute AR are discussed below.

Acute AR, most commonly caused by infectious endocarditis, aortic dissection, or aortic valve damage from trauma, usually results in a medical emergency. The sudden structural or functional impairment of the aortic valve leads to rapid diastolic backflow into the LV, which prevents compensatory mechanisms from developing. Hemodynamically, this leads to rapid decompensation through several mechanisms. Firstly, left ventricular volume overload occurs rapidly during acute AR. During diastole, the LV receives blood from both the left atrium and regurgitant flow from the aorta, resulting in acute volume overload. The sudden increase in end-diastolic volume causes an immediate rise in LVEDP, which is transmitted retrogradely to the pulmonary circulation, leading to pulmonary congestion and edema. As the volume rapidly increases, so does the left ventricular pressure and wall stress. This abrupt increase in LV wall tension due to the elevated volume and pressure exacerbates myocardial oxygen demand while impairing coronary perfusion during diastole, which can lead to myocardial ischemia and reduced contractility. Finally, acute AR can result in compromised mitral valve function. The elevated LV pressure during diastole may cause premature mitral valve closure, altering its normal function and leading to a soft first heart sound (S1).

Physical examination findings in acute AR patients are distinct and reflect the hemodynamic urgency of the condition. The pertinent physical examination findings of acute AR are detailed in Table 2.

| Category | Findings | Description |

| General appearance | Appear critically ill, with distress, diaphoresis, and cyanosis | Indicative of systemic hypoperfusion and respiratory compromise |

| Cardiac auscultation | Diastolic murmur | Short, high-pitched, decrescendo murmur best heard at the left sternal border during early diastole |

| Soft S1 sound | Premature mitral valve closure dampens the intensity of the first heart sound | |

| Absent or faint S3/S4 | Occurs due to limited time for ventricular adaptation | |

| Pulse characteristics | Absence of bounding pulses and narrow pulse pressure | Reduced stroke volume, and diastolic pressure remains elevated |

| Pulmonary findings | Rales or crackles | Bilateral crackles indicative of pulmonary edema, extending to apices in severe cases |

| Tachypnea and respiratory distress | Reflective of pulmonary congestion and hypoxemia | |

| Signs of hypoperfusion | Cool, clammy extremities with delayed capillary refill | Signals poor systemic perfusion secondary to low cardiac output |

| Systemic signs | Hypotension and tachycardia | Result of compensatory sympathetic activation |

| Cyanosis and altered mental status | Develops in advanced cases as cardiac output declines |

S1, first heart sound.

Chronic AR develops gradually, allowing time for the LV to employ compensatory mechanisms to accommodate the increased volume load caused by the regurgitant flow. The primary adaptive response involves eccentric hypertrophy, characterized by cardiomyocyte elongation and thinning, leading to LV dilatation. This structural remodeling enables the ventricle to maintain stroke volume and cardiac output despite the increased regurgitant volume. Notably, patients often remain asymptomatic during this compensatory phase, sometimes for as long as 10–15 years. However, these compensatory mechanisms are not indefinite, and the persistent volume overload over time results in progressive myocardial dysfunction, marked by rising LVEDP and declining LVEF. Subsequently, symptoms emerge when this transition to decompensation occurs. Patients typically report exertional dyspnea due to elevated pulmonary pressures, fatigue from reduced forward cardiac output, and orthopnea or paroxysmal nocturnal dyspnea associated with pulmonary congestion. Palpitations may also be reported, driven by an augmented stroke volume or arrhythmias, such as premature ventricular contractions, which are common in advanced disease states.

Findings from physical examination of patients with chronic AR reflect the hyperdynamic circulation caused by the regurgitant flow and the compensatory changes in the LV. These findings are summarized in Table 3.

| Category | Findings | Description |

| Pulse characteristics | Corrigan’s pulse (water hammer pulse) | Bounding, rapid upstroke, and collapse in the arterial pulse due to wide pulse pressure |

| De Musset’s sign | Rhythmic head bobbing in synchronization with the heartbeat caused by exaggerated arterial pulsations | |

| Quincke’s sign | Visible capillary pulsations in the nail beds when pressure is applied to the distal nail plate | |

| Muller’s sign | Pulsation in the uvula observed during cardiac systole | |

| Cardiac auscultation | Diastolic murmur | High-pitched, blowing decrescendo murmur best heard at the left sternal border |

| Austin Flint murmur | Low-pitched, mid-to-late diastolic rumble at the apex caused by the regurgitant jet | |

| Systolic murmur | Ejection murmur due to increased forward flow across the aortic valve | |

| Physical examination | Wide pulse pressure | Increased systolic and decreased diastolic pressures from the augmented stroke volume |

| Displaced apical impulse | Forceful and sustained impulse due to left ventricular dilation | |

| Lateral and inferior apical displacement | An enlarged left ventricle displaces the point of maximal impulse laterally and inferiorly |

Classifying chronic AR is essential for delineating disease progression, predicting long-term clinical outcomes, and tailoring management. Current guidelines stratify chronic AR into four progressive stages (A through D), each reflecting specific clinical and hemodynamic features. Stages A–D are summarized below in reference to the 2020 American College of Cardiology (ACC) and American Heart Association (AHA) Guidelines for the management of patients with valvular heart disease [42].

Stage A, termed “at risk”, encompasses individuals with structural valve abnormalities but no evidence of regurgitation or clinical sequelae of the disease. At this stage, these patients have no hemodynamic consequences. “At-risk” members in this stage include patients with congenital bicuspid aortic valve, mild aortopathy, early rheumatic changes, and diseases of the aortic sinuses or ascending aorta. Surveillance focuses on identifying patients transitioning to more advanced stages [42].

Stage B refers to asymptomatic “progressive AR”. Stage B is characterized by

mild to moderate regurgitation, preserved LVEF, and normal or mildly dilated LV

dimensions. Symptoms are absent, but Doppler echocardiography often reveals mild

diastolic flow reversal in the descending aorta and regurgitant jets with

specific characteristics. In stage B patients with mild AR, the left ventricular

outflow tract (LVOT) jet width is

Stage C denotes asymptomatic severe AR and is subdivided into C1 and C2. C1

includes patients with normal LVEF (

Stage D, or “symptomatic severe AR”, represents the most advanced stage, with

patients reporting dyspnea, angina, fatigue, or heart failure symptoms.

Echocardiographic findings include severe regurgitant volume (

Advances in imaging modalities, including cardiac magnetic resonance imaging and three-dimensional echocardiography, have enhanced the ability to stratify AR severity accurately and assess the interplay between valvular dysfunction and ventricular remodeling. These classifications provide a structured framework to ensure timely intervention, particularly as patients progress to stages C2 and D. At these stages, any delay in therapy can result in significant morbidity and mortality [42].

According to the 2020 ACC/AHA guidelines for managing valvular heart disease, transthoracic echocardiography (TTE) is indicated in patients with signs/symptoms of AR. In moderate to severe AR with equivocal TTE findings, these patients warrant further workup using TEE, cardiac magnetic resonance imaging, or angiography [42].

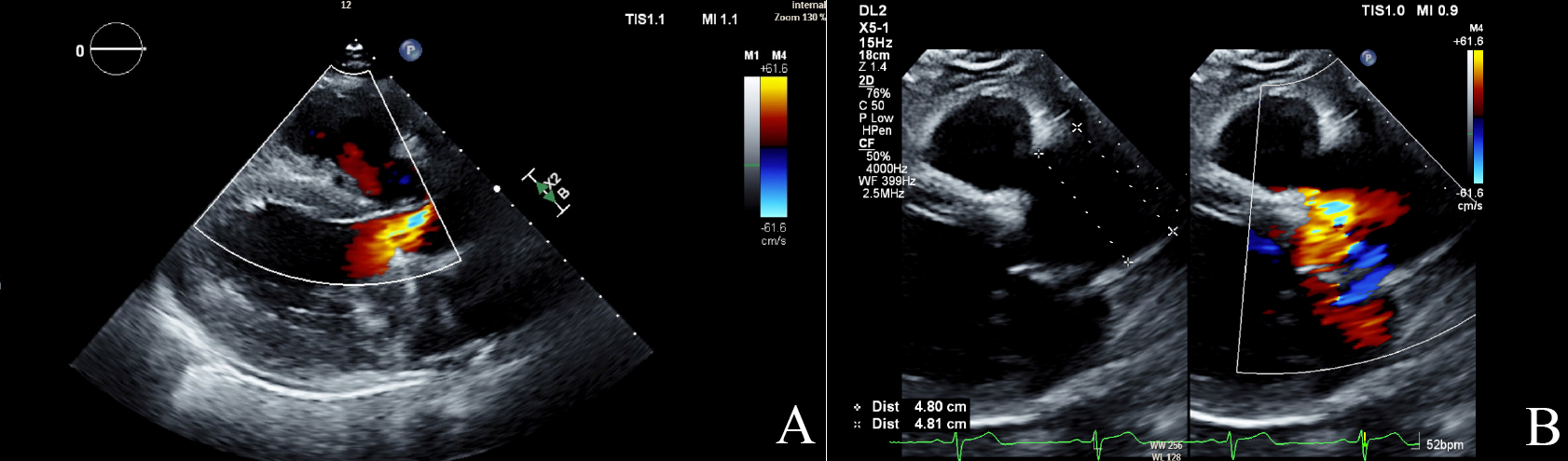

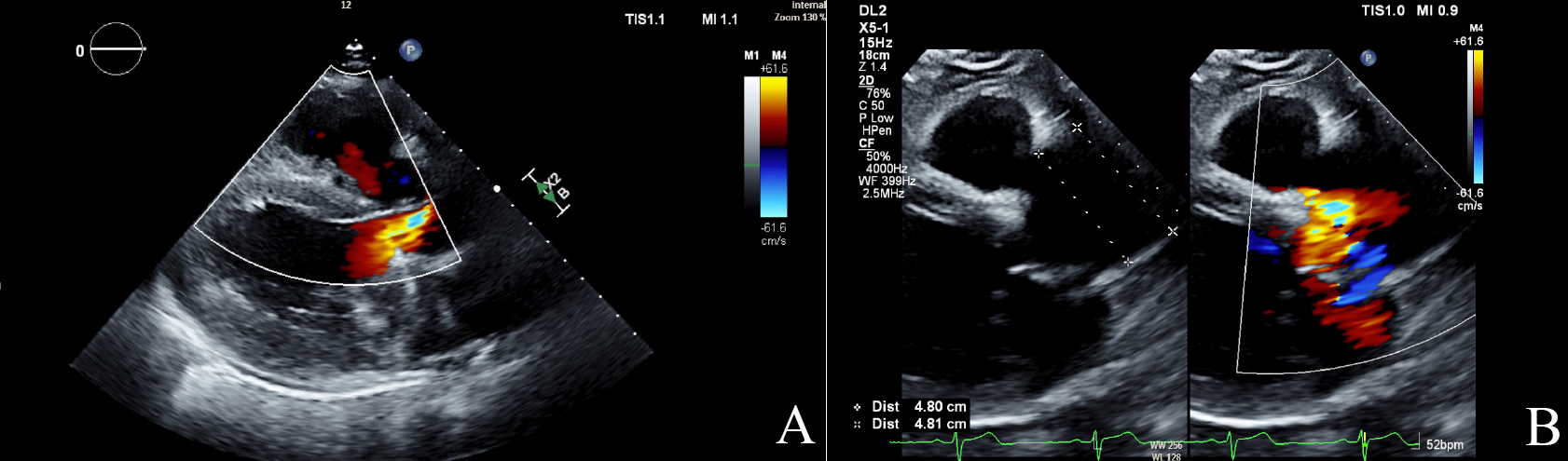

TTE forms the first-line diagnostic modality indicated for valvular disorders such as AR. TTE can also be used to determine the presence, severity, and cause of AR [43]. Fig. 1 shows the echocardiogram findings of AR in a patient with aortic leaflet dysfunction and dilated aortic root. Color flow Doppler imaging can identify the presence of a regurgitant jet at the aortic valve during diastole and measure the jet width, jet area, and vena contracta (VC) width [43]. These measurements tend to be reliable with a central jet. However, the AR severity could be underestimated if there is an eccentric jet, which is a regurgitant AR jet traveling along the posterior aspect of the LVOT or the anterior leaflet of the mitral valve [44]. If there is evidence of an eccentric jet, a measurement of the proximal isovelocity surface area (PISA) can be used to assess the AR severity. Continuous wave Doppler can be used to measure pressure half-time (PHT), deceleration time, and signal density [43, 45]. Pulsed wave Doppler via the suprasternal view is useful in determining the degree of holodiastolic flow reversal in the descending thoracic compared to the forward systolic flow, as well as the regurgitant volume, regurgitant fraction, and effective regurgitant orifice area (EROA) [43]. The M-mode can be used to evaluate for fluttering, a component of the Austin Flint murmur, and premature mitral valve closure caused by the regurgitant AR jet [43].

Fig. 1.

Fig. 1.

Echocardiographic findings in aortic regurgitation. (A) Color Doppler image of aortic regurgitation jet (mosaic color) in parasternal long axis (PSLAX). (B) The PSLAX view shows a dilated aortic root measuring 4.8 cm with a regurgitant jet in mosaic. TIS, thermal index soft tissue; MI, mechanical index; DL2, display layout 2; 2D, two-dimensional; CF, color flow; WF, wall filter.

TTE is useful for determining the LV size and systolic function, aortic root dilatation, aortic dissection, endocarditis, and other leaflet pathologies [42]. In chronic AR, the LV systolic function is initially normal or even slightly above normal. However, remodeling occurs over time to compensate for the increased LV pressure and volume. Thus, the LV size increases, and LVEF decreases. In contrast, the TTE findings in acute AR demonstrate significant regurgitation but normal LV size and systolic function [46]. A shorter PHT indicates rapid equilibration of the aortic and LV diastolic pressures, thus corresponding to more severe AR. This measurement is especially useful in acute AR; in chronic AR, the LV has undergone prolonged remodeling, which allows it to adjust for the increased diastolic pressures [47]. Certain measures for AR, including regurgitant volume (RV) and EROA, are predominantly used in the workup of chronic AR, as these measurements can be unreliable in acute AR [46]. Semiquantitative and quantitative measures can be utilized to stratify the severity of AR, as seen in Table 4 (Ref. [48]).

| Parameters | Mild | Moderate | Severe | |

| Semiquantitative | ||||

| Vena contracta width (mm) | 3–6 mm | |||

| Pressure half-time (ms) | 500–200 ms | |||

| Quantitative | ||||

| Effective regurgitant orifice area (mm2) | 10–30 mm2 | |||

| Regurgitant volume (mL) | 30–59 mL | |||

Echocardiographic findings are also used to predict outcomes, in addition to utilizing TTE to determine the prevalence and severity of AR. Indeed, the LVEF has been well-documented as a long-term predictor of survival in patients with chronic AR [49, 50]. In asymptomatic patients, quantitative American Society of Echocardiography (ASE) measurements, such as RV and EROA, were used to show a positive correlation between AR severity and an increased risk of mortality and cardiac events [51]. Other echocardiographic measures, including LV end-systolic volume index (LVESVi) and linear LV end-systolic dimension index (LVESDi), are associated with increased mortality risk [52, 53].

Chronic AR can progress over many years with new or worsening symptoms, increased severity, reduced LVEF, and LV enlargement [54]. This progression over time necessitates serial echocardiographic surveillance of AR, as the appropriateness for surgical intervention can change as symptoms, severity, and LV size and function worsen [42, 55, 56]. Moreover, the American and European guidelines vary slightly regarding the screening frequencies. Current recommendations for AR screening (for patients in which surgery is not yet indicated) can range anywhere from every 3–6 months to every 3–5 years, depending on AR severity and/or significant worsening of LV dysfunction or size [42, 57]. In patients meeting the criteria for surgical intervention, it is imperative to integrate shared decision-making in a patient-centered approach.

While TTE remains the gold standard in diagnosing AR, it has limitations. Indeed, poor acoustic windows or suboptimal image quality with TTE may necessitate the utilization of another imaging modality. Additionally, volumetric measurements obtained using TTE may display some variability in operator dependence and reproducibility compared with other modalities [58].

TEE is an alternative diagnostic tool in AR evaluation. If TTE is inconclusive or has poor acoustic windows, TEE can be utilized to obtain quantitative measures for identifying the presence and severity of AR [42, 59]. TEE can also further identify the aortic leaflet or root pathologies [43]. The diagnostic utility of TEE in evaluating endocarditis has long been established, and presents high sensitivity and specificity in identifying valvular vegetations [60, 61, 62]. In addition, TEE is useful in preoperatively evaluating the aortic valve and root structural anatomy for anticipated surgical interventions [43, 46]. Specifically, TEE is used in the presurgical evaluation to establish the underlying mechanism of AR, guide the operative approach in valve repair or replacement, and predict postoperative outcomes [63]. TEE also represents a valuable tool in assessing for dysfunction or misalignment of a prosthetic valve [46].

The information extracted from imaging studies, such as CT, is beneficial in precisely mapping the aortic size and morphological features of the AR whilst assessing the risk of coronary artery disease [64]. Maximum diameter measurements of the aortic valve are crucial for surgical planning and are divided into four levels: annulus, sinus of Valsalva, sino–tubular junction, and tubular ascending aorta [64]. CT imaging can also shed light on the pathological state of the aortic valve, such as calcifications, prolapse, infectious etiology, and/or rheumatic disease, with an emphasis on utilizing retrospective electrocardiographic (ECG)-gated CT as the best choice to pinpoint such findings rather than a higher radiation dose [64].

CMR imaging can be used as a diagnostic tool in AR when there is inadequate data from other imaging modalities. This includes situations with suboptimal echocardiographic images, poor acoustic windows, or discordance between echocardiographic and clinical findings. CMR imaging has also been validated as a reliable modality for evaluating valvular disorders such as stenosis and regurgitation [65]. Indeed, CMR imaging can be used for AR patients to assess aortic valvular or root pathology, AR severity, LV size, function, and remodeling [43, 65]. CMR imaging can also be used to evaluate for holodiastolic flow reversal in the descending aorta, which strongly predicts severe AR and mortality [66, 67].

Notably, CMR has consistently produced reliable and reproducible results in multiple studies comparing the reliability of imaging findings to the well-established modality of Doppler echocardiography [68, 69, 70, 71, 72]. Moreover, compared to TTE, CMR imaging has demonstrated less variability in assessing regurgitant volume measurements [58, 73]. Additionally, CMR assessment of the regurgitant volume is more reliable than TTE, which may be due to the ability of CMR imaging to better localize the imaging slice to the correct aortic level [74, 75, 76, 77].

Long-term LV volume overload due to chronic AR can cause LV remodeling, which is mediated by myocardial fibrosis and predisposes to the development of heart failure [78, 79, 80]. Thus, investigating the extent of LV remodeling with CMR is important in evaluating AR [43, 81]. The degree of LV remodeling can be quantified using CMR imaging to determine the LVESVi. In asymptomatic or minimally symptomatic patients, the CMR measurement of the LVESVi and regurgitant fraction was associated with symptom progression and all-cause mortality [82]. Indeed, one study demonstrated that CMR imaging was superior to TTE in evaluating LV mass and remodeling [83].

Similar to serial echocardiography, CMR imaging can quantify the degree of chronic AR progression and determine the timing of surgical intervention. Moreover, CMR imaging can reliably predict outcomes and surgical requirements [84, 85]. In fact, CMR imaging can also be utilized post-transcatheter aortic valve implantation (TAVI) to assess for AR severity, paravalvular regurgitation, and LV function and size [86, 87].

While CMR imaging is an effective tool in evaluating AR etiology, severity, intervention, and screening, there are limitations to this modality; for example, the cost of CMR imaging is significantly increased compared with TTE, TEE, and CT. Additionally, unlike the previously discussed imaging modalities, CMR imaging is not currently widely available at all facilities. Nonetheless, as the healthcare industry continues to innovate and advance, CMR imaging will likely become a mainstay in the diagnostic approach to AR.

Updated societal guidelines suggest the reservations of cardiac catheterization with LV and aortic angiography for situations with inconclusive findings despite extensive diagnostic workup or when there is clinical concern for acute coronary syndrome (ACS) [42, 88]. Aortic angiography, or aortography, can assess hemodynamic measurements, AR severity, aortopathy, and LV size and function [89, 90]. Aortography was once considered a mainstay in the diagnostic workup of AR. However, aortography has since been overtaken by TTE and CMR imaging due to the reliability of these noninvasive imaging modalities. Thus, the modern indication of aortography is mainly for evaluating paravalvular leaks (PVLs), using the video-densitometry technique for monitoring after TAVI [91]. This technique can be utilized to obtain quantitative measurements, which predict post-TAVI outcomes, including mortality [92, 93, 94]. Thus, given these possible outcomes, aortography findings can be used to manage post-TAVI patients and evaluate for any indication of repeat valvular intervention.

The management of AR follows a comprehensive approach that factors in chronicity, clinical presentation, and objective data: this can include a medical, surgical, or combined approach.

Acute AR: Surgical intervention to treat acute severe AR should not be delayed, especially in patients with red flag signs involving hemodynamic instability, such as hypotension, pulmonary edema, or low flow state [42].

Chronic AR: Management depends on the stage, regurgitant severity, clinical symptoms, and LV size and function [42].

The key mechanism for pharmacologically managing AR is to reduce afterload on the LV, thus promoting forward cardiac output and discouraging regurgitant flow. Current guidelines recommend treating patients with chronic AR stages B and C using an antihypertensive regimen for systolic blood pressure (SBP) above 140 mmHg [42].

The mainstays of treatment include using an angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitor (ACE-i) or an angiotensin II receptor blocker (ARB). Many studies have shown the benefits of afterload-reducing agents in managing patients with AR and coexisting hypertension. These include decreased mortality, reduced LV volume overload, improved LVEF and cardiac output, decreased degree of regurgitation, and decreased myocardial oxygen demand [95, 96, 97, 98, 99, 100, 101]. Moreover, when used in patients with chronic severe AR, beta-blockers (BBs) improved survival, mainly in patients with higher heart rates [102]. Interestingly, BBs are avoided in acute AR caused by etiologies other than aortic dissection, as these drugs can attenuate the appropriate tachycardic compensatory response [42].

Further long-term studies have shown that the pharmacological approach does not decrease or delay the need for valve intervention in patients with chronic, severe AR [103]. Thus, in addition to medical management, the surgical approach plays a significant role in managing AR.

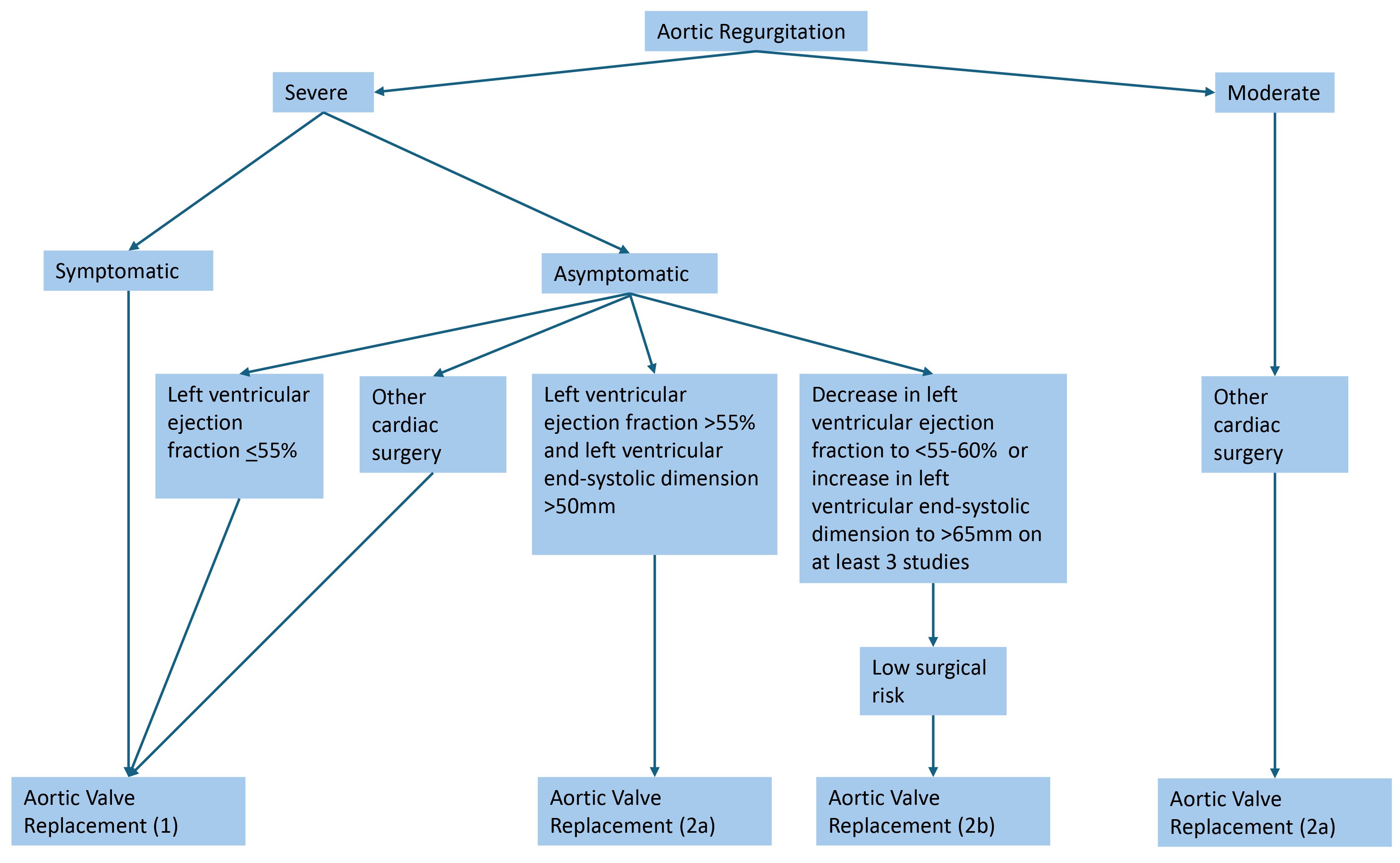

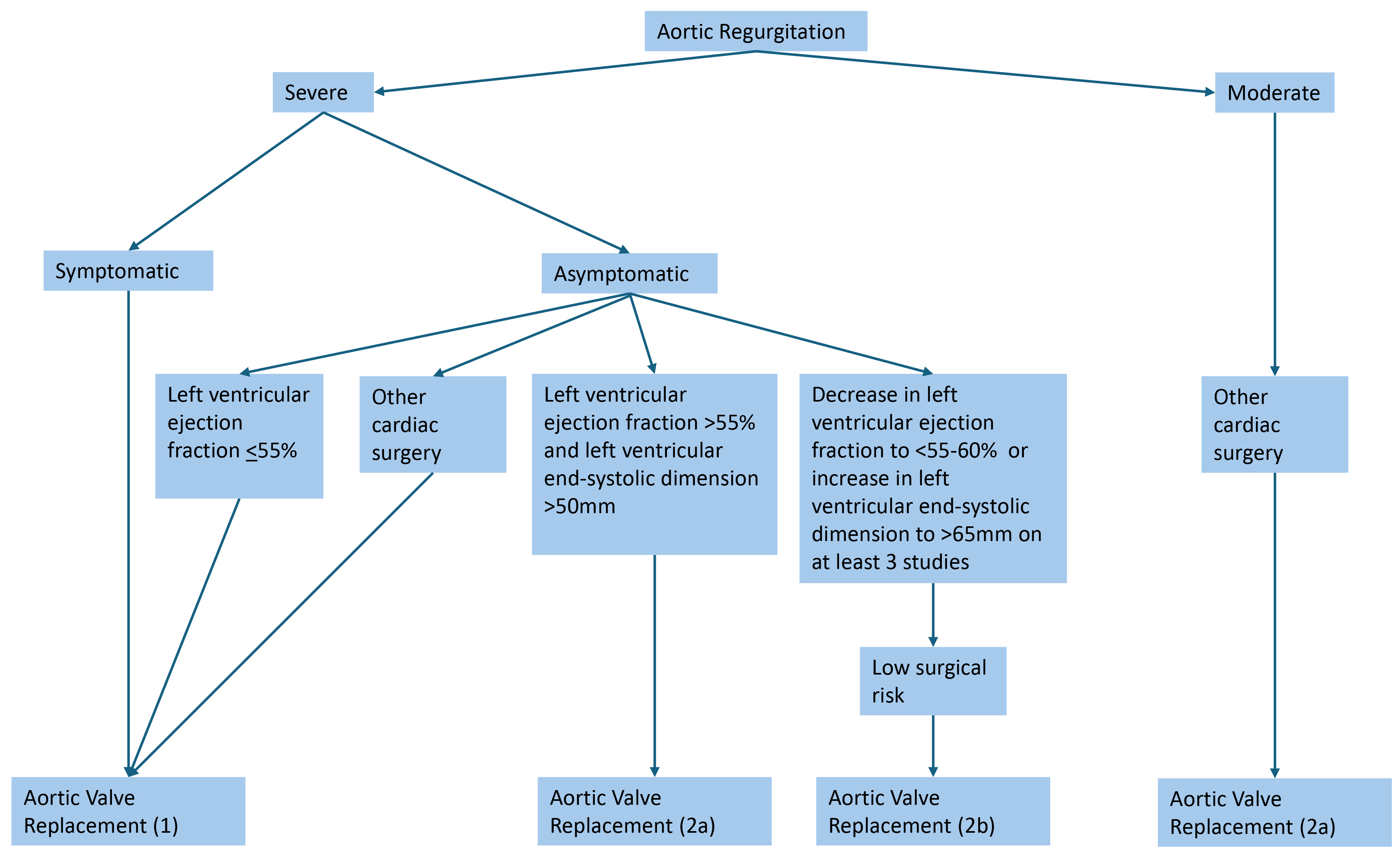

According to the updated 2020 AHA/ACC guidelines, recommendations for valvular intervention in AR are largely based on severity, symptoms, LV function, and size (Fig. 2; Ref. [42]). Aortic valve replacement (AVR) is indicated in symptomatic severe AR (stage D), asymptomatic severe AR with LV dysfunction or dilation (stage C2), asymptomatic severe AR with normal LV function (stage C1) but with progressively worsening LVEF or dilation, and moderate AR that is also undergoing surgery for other concurrent cardiac issues [42]. Shared decision-making with patients, considering patient-specific factors such as age, surgical risk, and risk factors, is an important aspect of preoperative evaluation.

Fig. 2.

Fig. 2.

Indications for aortic valve replacement in aortic regurgitation [42]. Severe aortic regurgitation is defined as a vena contracta length greater than 0.6 cm, holodiastolic aortic flow reversal, a regurgitant volume greater than or equal to 60 mL, a regurgitant fraction greater than or equal to 50%, and an effective regurgitant orifice area greater than or equal to 0.3 cm2.

While societal guidelines recommend valvular intervention for AR based largely on symptoms and echocardiographic findings, there is a growing belief amongst clinicians that interventions should be pursued even before deleterious LV remodeling occurs. One study that evaluated young patients with chronic AR who underwent AVR showed that patients with higher baseline LVESD values were less likely to achieve improvement after valve replacement [104]. Another study demonstrated that, among patients who underwent surgical aortic valve replacement (SAVR), those who met either class II or no indication had better survival outcomes than those who met the class I indication for AVR [105].

These findings suggest that pursuing an earlier intervention may be beneficial in preventing the development of clinical symptoms, heart failure, and death. This may be partly due to the formulation of the current guidelines using older studies, which do not consider the contemporary advances in invasive management. While the 2020 AHA/ACC guidelines did progress in updating parameters from previous guidelines, future societal guidelines should aim to advance these recommendations further to favor earlier intervention.

Significant recent advancements have been made in developing transcatheter heart valves (THVs) used for transcatheter aortic valve replacement (TAVR). Previously, standard bioprosthetic valves were used for TAVR to treat both AS and AR; however, structural differences between AS and AR limit the reliability of the same valve in both pathologies. For example, TAVR valves in AS rely on the calcification of the aortic valve to allow for the replacement valve to be seated properly. In contrast, AR (in the absence of concomitant AS) does not have significant valvular calcification; thus, there can be challenges with ensuring stabilization of the replacement valve. For these reasons, innovation in TAVR valve technology for AR has been an area of growing research and industry interest.

The JenaValve Trilogy system is a novel, dedicated THV developed to treat pure AR [106]. Once deployed, the device clips onto the native aortic valve leaflets to ensure anchoring within the annulus; early results show favorable outcomes for technical success and survival [106, 107, 108, 109].

Meanwhile, the J-Valve system represents another recently introduced THV for pure, native AR [110]. This device is a self-expanding porcine valve with anchor rings to assist with proper seating within the annulus. Studies have shown high procedural success rates and survival, and a low rate of complications [111, 112, 113].

In treating native AR, dedicated THV outperforms off-label TAVR valves in outcomes including procedural success, reintervention rates, and mortality [114, 115]. While these novel THVs offer an exciting innovation to the invasive AVR approaches, further studies are needed to assess the long-term outcomes of these valves. Large-scale studies are ongoing to evaluate these devices further using real-world data.

The catheterization and surgical approaches used in AR interventions are associated with TAVR and SAVR, respectively. TAVR involves inserting a bioprosthetic aortic valve replacement, whereas SAVR involves inserting either a bioprosthetic or mechanical aortic valve.

TAVR is generally recommended in patients older than 80 years of age with an expected life expectancy of less than 10 years, as older patients have a high risk of morbidity and mortality with SAVR [42, 116]. Conversely, the current guidelines highlight the importance of SAVR as the preferred treatment method in patients under 65 years old with a life expectancy greater than 20 years.

The use of TAVR to treat AR can pose unique challenges. Some repercussions include the formation of acute transcatheter valve embolization or migration (TVEM) [117]. Additionally, aortic dilatation and possible valve malpositioning pose significant risks of causing paravalvular regurgitation or leaks. These complications can be a major cause of morbidity and mortality after aortic valve replacement, and regular post-procedural monitoring is often indicated to screen for complications.

Postoperative evaluation of prosthetic aortic valves via either SAVR or TAVR is primarily performed using Doppler echocardiography. Initially, a TTE is performed within 6–12 weeks after patients undergo aortic valve replacement, which serves as a new baseline against which future studies can be compared. Echocardiographic information that is obtained for the evaluation of the prosthetic valve includes LV systolic function and size, pressure gradients, valvular velocities, jet contour, regurgitant severity, opening and closing of valve leaflets, leaflet thickening, valve obstruction, paravalvular regurgitation, and prosthetic valve position [118]. TEE should also be considered if the patient develops heart failure symptoms or if TTE reveals abnormal transvalvular gradients.

The subsequent echocardiographic surveillance intervals are performed using a patient-specific, dynamic approach.

For the bioprosthetic SAVR valves, it is generally recommended to repeat TTE 5 years after the initial study, and then again after 10 years, before continuing surveillance annually [42]; annual TTE is recommended for bioprosthetic TAVR valves [42]. Comparatively, regular surveillance is not indicated for mechanical prosthetic valves, and general recommendations, as seen in the other valve types, suggest obtaining repeat imaging if new signs or symptoms concerning valvular or myocardial dysfunction develop. As discussed, alternative imaging modalities, including TEE, CT, or CMR, may be utilized for suboptimal TTE findings.

AR is a valvular disorder that can progress over time, eventually causing LV dilatation and dysfunction. AR can result from acute or chronic pathologies of the aortic leaflets or the aortic root. Thus, accurate diagnosis and severity grading are warranted in the workup of AR to deliver the appropriate intervention.

TTE represents the first-line tool for diagnosis, severity, and monitoring; however, other imaging modalities can be utilized if inadequate TTE findings are present. Further, TEE is a strong diagnostic tool for evaluating the underlying etiology and for surgical evaluation. CT can be used to assess for AR etiology, surgical planning, and coexisting coronary artery disease. CMR has already been established as a powerful imaging modality with reliable results and appears to be heading toward dominating the diagnostic approach to AR in the near future as the healthcare system catches up to its rapid emergence. While the role of aortography has diminished as other imaging modalities have increased, aortography remains valuable in assessing for PVL after valvular intervention.

Medical management is mainly limited to afterload reduction in AR with systemic hypertension. Invasive management, including SAVR or TAVR, is indicated based on severity, symptomatology, and LV dynamics. Significant recent innovations in AVR have been shown to improve outcomes to such a degree that many experts are considering pursuing valvular intervention even before the requirement by current guidelines. Additionally, advancements in THV devices continue to expand the boundaries of the transcatheter approach. The diagnosis and management of AR remains at the cutting edge of technology and innovation, and future research should endeavor to continue to drive this field forward.

RG, MVD, KL, and TT designed the project. RG, NR, MVD, and TT completed the formal analysis. RG, NR, MVD, and TT wrote the original draft of the manuscript. TT, SH, KL, RG, MVD, NR, and TC performed critical review, editing, and revision of the manuscript. TT, SH, KL, and TC provided supervision of the project. All authors contributed to the conception and editorial changes in the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript. All authors have participated sufficiently in the work and agreed to be accountable for all aspects of the work.

Not Applicable.

We would like to acknowledge the Department of Internal Medicine at the Kirk Kerkorian School of Medicine at the University of Nevada, Las Vegas (UNLV) for providing administrative and technical support.

This research received no external funding.

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

Publisher’s Note: IMR Press stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.