1 Department of Cardiology, McGill University Health Centre, Montreal, QC H4A 3J1, Canada

Abstract

Congenital long QT syndrome (LQTs) is an inherited cardiac condition resulting from cardiac repolarization abnormalities. Since the initial description of congenital LQTs by Jervell and Lange-Nielsen in 1957, our understanding of this condition has increased dramatically. A diagnosis of congenital LQTs is based on the medical history of the patient, alongside electrogram features, and a genetic variant that is identified in approximately 75% of cases. The appropriate risk stratification involves a multitude of factors, with β-blockers being the cornerstone of therapy. Recent developments, such as the incorporation of artificial intelligence (AI) for electrocardiogram (ECG) interpretation, genotype–phenotype-specific therapies, and emerging gene therapies, may potentially make personalized medicine in LQTs a reality in the near future. This review summarizes our current understanding of congenital LQTs, with a focus on risk stratification, current therapeutic interventions, and emerging developments in the management of congenital LQTs.

Keywords

- long QT syndrome

- QT prolongation

- risk stratification

Congenital Long QT syndrome (LQTs), first described by Jervell and Lange-Nielsen in 1957, is an inherited cardiac channelopathy characterized by repolarization abnormality, characterized as prolonged QT interval on electrocardiogram (ECG) [1]. This condition predisposes individuals to recurrent syncope and fatal arrhythmias such as torsade de pointes (TdP) and sudden cardiac death [1]. Since its initial description, significant advancements have been made in understanding the underlying genetic predisposition, clinical presentation and management of this condition.

Disease-causing gene mutations have been identified in 75% of cases of LQTs and are further divided into subtypes based on the underlying genetic disruption [2]. Genes encoding for cardiac ion channels, with KCNQ1, KCHN2, SCN5A represent most of the common pathogenic variants in LQTs subtypes 1,2 and 3 respectively. Despite the growing insights into genotype-phenotype correlation for gene-specific therapies in LQTs, varying degrees of penetrance and phenotypic expression pose a significant diagnostic challenge [3]. Furthermore, optimising risk reduction in LQTs remains a concern. Recent developments such as incorporation of artificial intelligence (AI) for ECG interpretation, genotype-phenotype specific therapies, and emerging gene therapies can potentially make personalized medicine in LQTs possible in the near future.

This review aims to provide an up-to-date synthesis of the current understanding of LQTs, focusing on diagnosis, risk stratification, current and novel tools for therapeutic developments in the management of patients with LQTs.

Table 1 outlines the recently proposed modified LQTs score 1 [4]. A clinical diagnosis of LQTs is established when the score is

| Finding | Points | ||

| History | |||

| Clinical history of syncope | |||

| 1 | |||

| 2 | |||

| Family history | |||

| Family history of definite LQTs | 1 | ||

| Unexplained sudden death in a first-degree family member | 0.5 | ||

| ECG | |||

| Correct QT interval (QTc interval by Bazett’s formula: QT/√RR) | |||

| 1 | |||

| 2 | |||

| 3.5 | |||

| QTc interval increase | 1 | ||

| Torsade de pointes | 2 | ||

| T-wave alternans | 1 | ||

| 1 | |||

| Bradycardia for age | 0.5 | ||

| Genetic finding | |||

| Pathogenic variant identification | 3.5 | ||

LQTs, long QT syndrome; QTc, corrected QT; RR, time between 2 successive R waves on ECG; ECG, electrocardiogram.

It is important to note that adult women have longer QTc intervals than men. Although the mechanism of gender difference seen in human ECGs are not fully understood, it is believed that sex hormones, testosterone and progesterone, influence the repolarisation complex [5]. The changes in sex hormones during the menstrual cycle, pregnancy and menopause have a complex effect on the QTc interval in women but remain poorly understood [5]. Moreover, it is crucial to acknowledge that the response to treatment, particularly

QTc measurement remains the cornerstone of the diagnosis of LQTs. However, despite its apparent simplicity, incorrect QTc measurement leads to erroneous diagnoses, significantly influencing the potential for diagnostic reversals in affected patients. A prior study reported that 62% of electrophysiologists and

It is important to highlight that in approximately one in four patients with LQTs, the QTc interval can be normal, a phenomenon referred to as ‘concealed’ LQTs [9]. As such, it is critical to unmask QT changes with dynamic testing.

Initial studies by Bazett showed that an abrupt increase in heart rate results in acute shortening of the action potential after the first fast heartbeat but requires several hundred beats or up to 2 minutes before a new steady state is achieved [10, 11, 12]. Patients with LQTs have been shown to have a maladaptive response to changes in heart rate, especially when this occurs suddenly, most notably in patients with LQT 2 [13, 14]. The epinephrine challenge is no longer recommended given high interobserver and intraobserver interpretation resulting in poor reproducibility and reliability [15]. Other methods that induce sudden changes in heart rate, such as exercise stress testing, hyperventilation and rapid standing with ECG monitoring, can provide valuable and practical diagnostic information [16]. Resultant sinus tachycardia from adrenergic stimulation affects QTc interval independently of the concomitant tachycardia [17]. A QTc interval

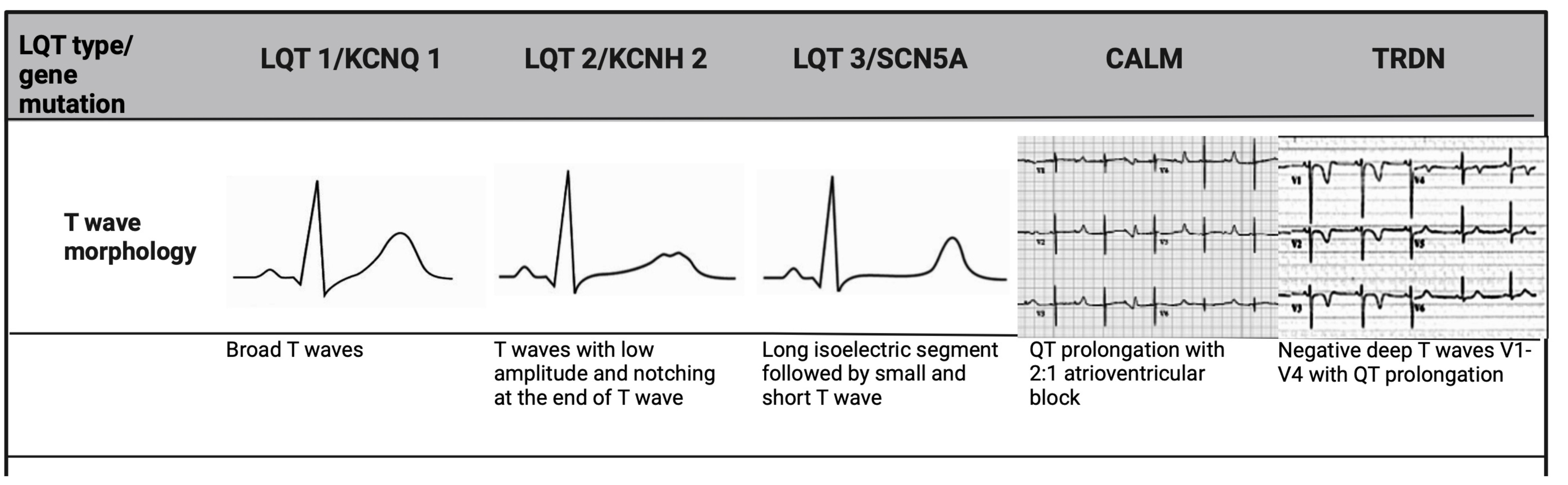

When QTc interval duration is borderline, the repolarisation morphology of T-waves on ECGs are particularly useful not only in making the diagnosis, but also in differentiating subtypes of LQTs [21]. In LQT 2, a distinct bifid T-wave morphology is noted, whereas LQT 3 will show an iso-electric interval before a low amplitude T-wave, similar to that seen in hypocalcaemia. In LQT 1, the T-wave morphology appears more broad-based and prolonged (Fig. 1). Given that these changes are subtle in LQT patients, it is imperative to assess all 12 leads of the ECG [16].

Fig. 1.

Fig. 1. T-wave morphology specific to LQTs genotype. LQT 1 shows broad-based T-waves; LQT 2 demonstrates low-amplitude and bifid T-waves; and LQT 3 presents with a prolonged ST-segment and a late-peaking T-wave. CALM mutations, manifest earlier in life, and are associated with bradycardia and atrioventricular block, while TRDN mutation shows deeply inverted T-waves in precordial leads. LQTs, long QT syndrome; TRDN, triadin.

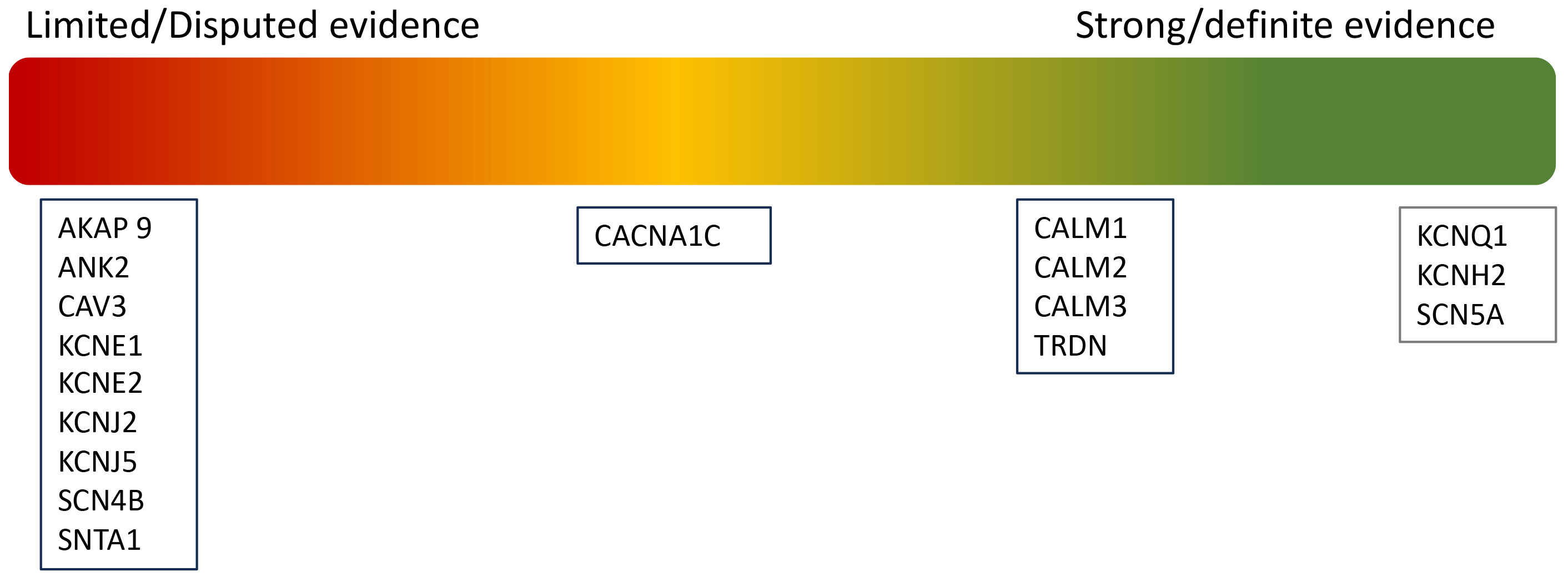

Although 17 genes were initially identified as causative of LQTs, a recent reappraisal by ClinGen has led to a reclassification, only seven genes now considered to have strong or definitive evidence for LQTs [22], as summarised in Fig. 2.

Fig. 2.

Fig. 2. Re-classification of pathogenic variants in LQTs.

The majority of cases of LQTs are caused by loss-of-function variants in voltage-gated potassium channels [23]. The two subtypes of delayed rectifier potassium channels, KV7.1 (slow) and KV11.1 (rapid) are primarily responsible for the outward potassium current in phase 3 of the ventricular action potential. These channels play a crucial role in cardiac myocardial repolarisation [23, 24]. LQT 1 is caused by a variation in KCNQ1 that encodes for the ɑ subunit of KV7.1, while LQT 2 is caused by a variation in KCNH2, which encodes for the ɑ subunit of KV11.1 [3]. LQT 3, on the other hand, is a result of the gain-of-function variant in the SCN5A gene, encoding NaV1.5, which causes persistent inwards sodium flow during the plateau phase of the action potential, resulting in delayed repolarization [3, 25]. Under normal conditions, sympathetic and parasympathetic activity results in overall augmentation of depolarisation and repolarisation kinetics. However, in patients with LQTs, this can lead to prolongation of action potential duration, promoting early after-depolarization (EAD) that may trigger TdP. The three undisputed genes KCNQ1, KCNH2, and SCN5A account for approximately 90% of gene-positive cases, with gene-specific triggers such as exercise (LQT 1), emotional stress (LQT 2) and sleep (LQT 3), identified respectively [26].

The 3 LQT-associated CALM variants present with atypical features. In addition to QTc prolongation, CALM variants manifest in infancy or early childhood with marked sinus bradycardia or atrioventricular block, seizures and development delay (Fig. 1) [22]. Triadin (TRDN) is a critical protein in the cardiac calcium release complex, binding to type 2 ryanodine receptor (RyR2), calsequestrin 2 (Casq 2), junctophilin 2 (Jph 2) to release calcium from the sarcoplasmic reticulum to ensure proper excitation-contraction coupling in the heart [27]. The loss of TRDN can result in a particularly malignant phenotype, termed Triadin knockout syndrome, usually presenting in childhood [28]. These patients exhibit transient QTc prolongation and T-wave inversion in precordial leads V3–V5, that are very atypical (Fig. 1) [28]. They also display exercise-induced ectopy at peak exertion, a hallmark of catecholaminergic polymorphic ventricular tachycardia (CPVT) rather than LQTs. This overlap of clinical features has led to its consideration as a distinct disorder however, given that QT prolongation was considered the most discernible abnormality, it is currently included as an atypical phenotype of LQTs [22]. The role of CALM 1–3 and TRDN genes remains to be established in typical adult LQT patients [4, 22].

Genetic testing should be performed in any patient presenting with a prolonged QTc on the ECG. When a pathogenic mutation is found, subsequent cascade screening of family members of the proband is critical [4]. Genetic testing allows mitigation of gene-specific triggers and guides gene-specific treatment for different LQTs subtypes, which are discussed later in this review [29]. Given its high sensitivity, with a potential pathogenic variant identification in 75–80% of cases, genetic testing may similarly be considered useful in ruling out the presence of an inherited aetiology in patients where the clinical diagnosis is very borderline [30]. It is important to note, however, that in patients who are genotype-negative, but phenotype positive with clear QT prolongation, the risk of cardiac events remains equivalent, underscoring the continued need for these patients to be followed in a specialized cardiogenetics clinic and the importance of continuing

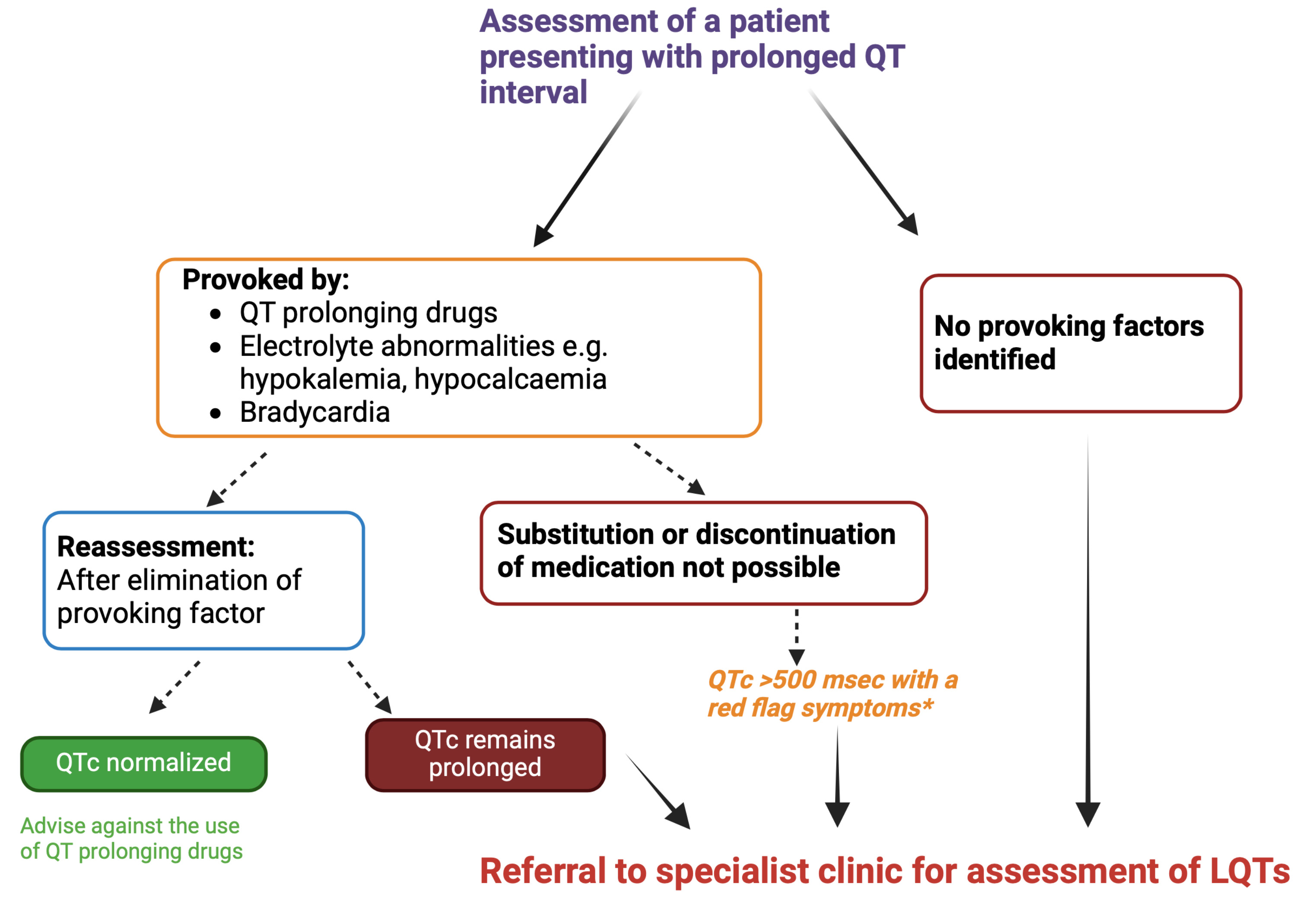

Fig. 3.

Fig. 3. Assessment of patients presenting with prolonged QT interval. *Red flag symptoms include the history of syncope or a family history of unexplained sudden death. If QTc interval

Currently, the diagnosis of LQTS, as described initially, hinges on accurate measurement of the QTc interval and 25% of patients have ‘concealed’ LQTs (i.e., gene positive, phenotype negative), which could delay appropriate therapy, making it critical for an efficient diagnostic tool for screening and detection. AI offers a promising new means of enhancing ECG interpretation [33].

Neural networks, which are a subtype of supervised machine learning algorithms, are capable of processing large volume data, in this case, ECGs, extracting meaningful patterns such as QTc interval and T-wave morphology [34, 35, 36]. Further to this, deep learning models excel in making predictions based on these learned patterns and can assist clinicians in risk stratification and decision-making [33].

In addition to 12-lead ECG, which is commonly used in training AI models, single-lead mobile ECGs have also yielded comparable results [37, 38]. A prospective study that assessed smartwatch single-lead ECG with conventional 12-lead ECG showed negligible difference (mean QTc interval was 407

AI has the potential to transform the way we approach LQTs, both in diagnosis and risk stratification, however, we need to be cognizant of the potential pitfalls of this technology. Potential bias in data gathering and the information used to train machine learning algorithms, challenges related to the interpretability of prediction models, potential utilisation of patient information and privacy leaks are a few concerns regarding the widespread use of this technology which needs to be addressed [33].

The advent of genetic testing has led to a significant increase in the identification of patients with ‘concealed’ LQTs [9]. These individuals have a substantially lower risk of arrhythmic events, approximately eight times lower, compared to those who are both genotype and phenotype-positive patients [9]. The annual rate of sudden death in symptomatic patients, however, is approximately 5%, with a further 10-year mortality rate as high as 50% [39].

The 1-2-3-LQTS-Risk model, used in the latest European Society of Cardiology (ESC) guidelines, estimates an individual risk of life-threatening arrhythmias based on two key prognostic determinants: the QTc interval and genotype (LQT1, LQT, LQT3) [4]. Furthermore, they also reported an incremental life-threatening arrhythmic risk of 15% for every 10 msec increase in QTc interval duration and subtypes LQT 2 and LQT 3 conferring a greater arrhythmic risk compared to LQT 1 at 130% and 157% respectively [9]. This study also highlighted the commencement of

This highlights the importance of adopting a ‘dynamic’ score in patients with LQTs, given how QTc interval and its associated risk change during patient follow-up and with therapy initiation and optimisation [29]. While the 1-2-3-LQTS-Risk model represents a ‘static’ score, i.e., a score determined at the time of diagnosis, recent evidence highlights the potential for risk modification over time [40]. A study reported the ‘static’ M-FACT score of

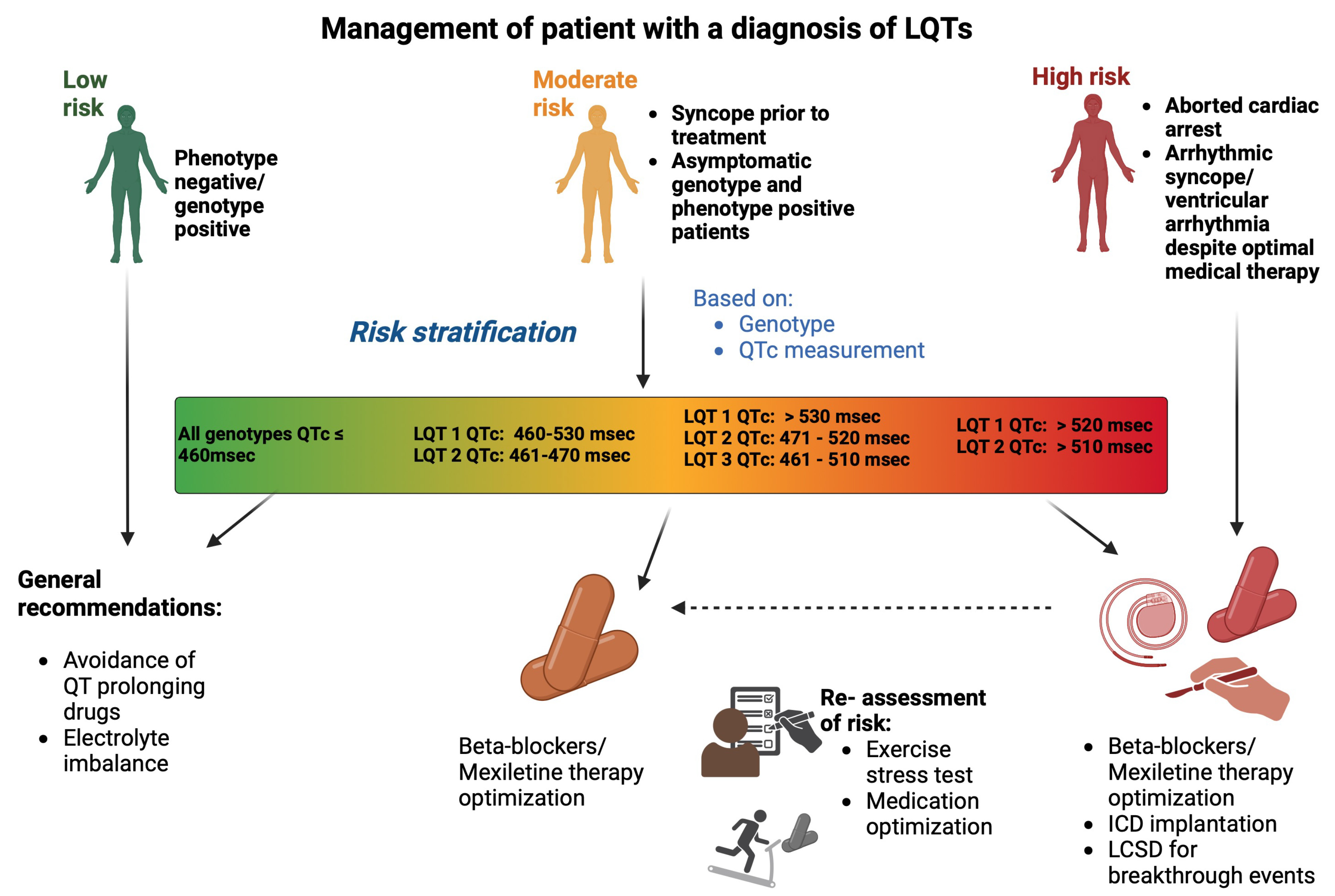

Fig. 4.

Fig. 4. Management of a patient with a diagnosis of LQTs. Risk stratification is based on QTc interval and genotype, categorizing patients into low, moderate, or high-risk. Management includes avoidance of QT-prolonging drugs, and pharmalogical management with

All patients with LQTs, regardless of ECG manifestation of QTc prolongation, should be given advice regarding avoidance of medications that prolong QTc interval, ensuring communication with their pharmacist. Re-iteration of the importance of adherence to beta blocker use, and avoidance of electrolyte imbalances such as hypokalaemia, is necessary at each follow-up appointment [4].

Drug therapy with

The choice of

Additionally, nadolol has been shown to reduce the risk of life-threatening arrhythmias by 62% when compared to other

Another common concern is the use of

Despite its efficacy, adherence to

LQT 3 can lead to a risk of life-threatening arrhythmias secondary to bradycardia [61]. Unlike other LQTs where ventricular arrhythmia occurs secondary to sympathetic activation, in this unique bradycardia-dependent QTc prolongation, the traditional use of

Mexiletine is a class 1b anti-arrhythmic agent that can suppress the effects of I Na-L, which has a ‘gain-of-function’ effect of SCN5A mutation in patients with LQT 3. Mexiletine has demonstrated shortening of the QTc interval by 63

However, the extent of QTc shortening with mexiletine strongly correlates with the baseline QTc interval and may not always lead to the suppression of arrhythmic events [64, 65]. Current ESC guidelines suggest verifying QTc interval shortening by at least 40 msec before long-term prescription of the agent, given the differential responses to mextiline in patients with LQT 3 [4]. Ranolazine, an anti-anginal agent and eleclazine, a novel selective inhibitor of I Na-L, have shown promising outcomes in shortening QTc interval in LQT 3, and clinical testing of these medications is currently underway [66, 67].

Patients with a history of cardiac arrest or ventricular arrhythmias should have an ICD implanted, given a 14% recurrence risk within 5 years [68]. Those with a clear diagnosis of LQTs and a history of malignant syncopal episodes, despite initiation of

The choice regarding a transvenous system as opposed to a subcutaneous ICD predominantly depends on the need for pacing support. A subcutaneous ICD consists of a parasternal subcutaneous lead connected to an active pulse generator positioned in the axillary region, with the entire system placed extravascularly [69]. This design reduces the risk of systematic infection and preserves the vascular system which is an important consideration in young patients with inherited cardiac conditions who may face long-term device-related complications [63, 64]. This is an important consideration when choosing the device, especially in patients where arrhythmias may be triggered by pause or bradycardia may be a limiting factor in

The role of cardiac sympathectomy in LQTs was first reported by Moss and McDonald in 1971 [71]. Although the exact mechanism of neuromodulation in LQTs remains to be completely elucidated, it reduces levels of norepinephrine release, thereby raising the threshold for ventricular fibrillation [72]. In addition to the therapeutic effects of beta-blockade, LCSD has an additive alpha-adrenergic-mediated effect due to preganglionic denervation that prevents repolarisation heterogenicity [73].

Initial studies reported LCSD to be effective in patients who remained symptomatic or presented with cardiac arrest despite the use of

The Heart Rhythm Society/European Heart Rhythm Association/Asia Pacific Heart Rhythm Society consensus document recommends LCSD in symptomatic patients despite the use of

Unlike structural cardiomyopathies, such as hypertrophic cardiomyopathy and arrhythmogenic cardiomyopathy, primary electrical conditions, such as LQTs, Brugada and catecholaminergic polymorphic ventricular tachycardia, result from ion channel abnormalities. Advanced cardiac imaging tools, such as speckle tracking, have shown subtle electrical and anatomical abnormalities in primary electrical conditions [76]. In initial electroanatomical mapping studies, more than 2 decades ago, Haïssaguerre et al. [77] demonstrated that in LQTs, premature ventricular contractions (PVCs) originated from the Purkinje system of the left ventricular, while in Brugada syndrome, the PVCs originated from the right ventricular outflow tract (RVOT). Following this, in Brugada syndrome, bipolar low-voltage areas and abnormal late potentials were identified in the RVOT with ablation in this region resulting in the normalisation of the Brugada pattern on the surface ECG [78].

Pappone et al. [79] sought to reveal similar findings in LQTs. They observed abnormally prolonged and fragmented electrograms in the RVOT of patients with LQTs, similar to that seen in with Brugada syndrome. Radiofrequency ablation of these abnormal substrates in the RVOT showed a reduction in ventricular arrhythmia burden and shortening of QT interval, suggesting that epicardial right ventricular outflow tract modification may be beneficial for patients with LQTS. The right ventricular epicardium (and particularly the RVOT) has a lower expression of connexins and cardiac sodium channels, which heightens its vulnerability to cardiac arrhythmias compared to other myocardial regions [80]. Although fragmentation of electrograms arising from this region has been postulated as the mechanism for the arrhythmogenic substrate, the precise mechanism of these abnormalities needs further clarification [81]. Larger, well-characterized controlled studies are required to explore this interesting preliminary observation, given the genetic and phenotypic heterogeneity presentations of LQTs [82].

Current therapies in LQTs primarily target symptoms to reduce arrhythmia-triggering events but fail to address the underlying molecular cause (i.e., ion channel dysfunction). Gene therapy promises mechanism-driven therapy. At present, gene replacement therapy, gene silencing therapy and direct genome editing are the three main means of achieving gene therapy [83].

In gene replacement therapy, pathogenic variants that result in insufficient production of protein, are the primary target [84]. Therapy is aimed at either augmenting or correcting the expression of the deoxyribonucleic acid (DNA) sequence to ensure near normal production of the protein. In gene silencing therapy, the main aim of therapy is to inactivate the mutated DNA sequence, which often produces adequate protein but exhibits harmful functionality that results in a dominant negative effect [84]. These 2 mechanisms of therapy are achieved through ribonucleic acid (RNA)-based strategies, with variable exogenous protein-coding sequence delivery, either a viral vector (such as adeno-associated virus 9) or via lipid nanoparticles [85, 86].

A recent proof-of-concept study in LQT 1 rabbits demonstrated a pronounced shortening of action potential duration with KCNQ1-Suppression Replacement (SupRep) gene therapy when compared to LQT 1 controls (LQT1-Untreated vs LQT1-SupRep, p

These RNA-based therapies are opposed to direct genome editing, in which the DNA sequence is modified with permanent effects. One such tool that has gained traction recently is the clustered regularly interspaced short palindromic repeats (CRISPR)/Cas9 nuclease system [84]. CRISPR/Cas 9 results in double-strand breaks in DNA, generated by programmable nuclease, with DNA sequences which can be inserted or deleted to inactivate an abnormal gene copy either in vitro or in vivo [89]. Its use is currently being studied, in vivo, on patient-derived induced pluripotent stem cells [90, 91]. Base and prime editors which comprise Cas9 nickase and a modified reverse transcriptase, can introduce, delete or substitute nucleotides without DNA breakage and are considered to have a more specific effect [84]. This method has been studied, in which a mouse with a pathogenic variant of SCN5A resulting in LQT 3, was effectively treated by the delivery of adenine base editor delivery via an adeno-associated virus vector [92].

However, off target mutations as well as tissue specific delivery of genome editors remain a hurdle. Another important concern regarding genome editing is the heritability of editing, as in theory genome editing can be expanded to germline cells (i.e., in human embryos) to treat inherited cardiac conditions such as LQTs with serious ethical issues [89].

Clinical genetic therapy holds the promise of personalised therapy in cardiac genetics. The presence of numerous unique LQT-causing variants and the complexity of cofounding mechanisms make these current methods challenging for widespread clinical use at present.

Despite enhanced understanding, LQTs continue to pose a diagnostic and management challenge in everyday clinical practice. While the identification of key pathogenic variants and development of subtype-specific treatment strategies have significantly improved patient outcomes, many patients remain underdiagnosed or misdiagnosed due to limitations of current diagnostic tools especially those with concealed or borderline phenotype [7]. Overdiagnosis also remains a concern, as misinterpretation of QTc interval can lead to unnecessary interventions, such as ICD implantation and long-term medication use [8].

In the era of technology, AI-enabled tools offer a promising solution to the detection of subtle ECG abnormalities, through deep learning algorithms [93]. Furthermore, the intergration of AI with wearable technologies, such as smartwatch-based single-lead recordings, could further facilitate timely diagnosis empowering patient-directed monitoring [37, 38]. However, the inherent challenges such as data validation across a diverse population, transparency in algorithm-based decision making and concerns regarding data privacy need to be addressed before the widespread adoption of these tools [33].

In addition to early detection and diagnosis, the forefront of management for LQTs is also shifting to genotype-guided management. Recent interest in gene replacement therapies, such as the SupRep and CRISPR, offers an opportunity for precision-based medicine in the near future.

LQTs is an inherited cardiac condition which occurs as a result of maladaptive cardiac repolarisation. It is imperative that physicians assess the patient’s clinical presentation, family history, and genetic test results in conjunction with QT measurement on ECG. Although a missed diagnosis of LQTs can be fatal, erroneous overdiagnosis of LQTs can also lead to substantial lifelong implications.

In the era of precision medicine, there is a paradigm shift in the clinical care of these patients, with the possibility of delivering patient-centric therapy in the near future.

DR, SG, RH and JJ made substantial contributions to the conception or design of the work; or the acquisition, analysis, or interpretation of data. All authors were involved in drafting the manuscript or revising it critically for important intellectual content. All authors gave final approval of the version to be published. All authors agree to be accountable for all aspects of the work in ensuring that questions related to the accuracy or integrity of any part of the work are appropriately investigated and resolved.

Not applicable.

Not applicable.

This research received no external funding.

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

Publisher’s Note: IMR Press stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.