1 Department of Cardiovascular Diseases, University Hospital Centre Zagreb, 10000 Zagreb, Croatia

2 Department of Cardiovascular Diseases, University of Zagreb School of Medicine, 10000 Zagreb, Croatia

Abstract

Implantable cardioverter defibrillators (ICDs) have significantly reduced the incidence of sudden cardiac death in patients with heart failure, particularly those with ischemic heart disease. However, the impact on overall mortality remains controversial, especially in non-ischemic heart failure patients. The Danish Study to Assess the Efficacy of ICDs in Patients with Non-Ischemic Systolic Heart Failure (DANISH) trial and subsequent studies have questioned the efficacy of ICDs in this population, particularly among older patients. The present study aimed to evaluate survival outcomes and predictors in a Croatian cohort of patients with an ICD or cardiac resynchronization therapy defibrillator (CRT-D) device.

This retrospective cohort study analyzed data from 614 patients who received an ICD or CRT-D device at KBC Zagreb between 2009 and 2018. Patient data, including demographic information, device indication, and clinical parameters, were collected at the time of implantation. Follow-up data were systematically recorded to assess device activation and survival outcomes. Statistical analyses included a detailed descriptive analysis, Kaplan–Meier survival estimates, and Cox regression models.

The cohort consisted predominantly of males (83.4%), with a mean age of 58.7 years. Most had reduced left ventricular ejection fraction (mean 31.4%) and were classified as New York Heart Association (NYHA) class II or III. Over a median follow-up of 48.4 months, 36.6% of patients died. Device activation occurred in 30.3% of patients, with appropriate activation observed in 88.2% of these cases. Cox regression identified age, non-sustained ventricular tachycardia (NSVT), and decompensation history as significant survival predictors.

This study confirmed that appropriate device activation improved survival in patients with an ICD/CRT-D. Age, NSVT, and history of decompensation were key predictors of device activation and survival outcomes. These findings underscore the need for individualized patient assessment when considering inserting ICDs, particularly in non-ischemic heart failure patients. Further research is needed to refine clinical guidelines and optimize patient selection for ICD therapy.

Keywords

- implantable cardioverter defibrillator

- cardiac resynchronization therapy defibrillator

- non ischemic heart failure

- survival outcomes

- device activation

Over the past two decades, the implantation of implantable cardioverter-defibrillators (ICDs) has been associated with a significant reduction in the incidence of sudden cardiac death and overall mortality among patients with ischemic heart disease. In contrast, no individual study, nor subgroup analysis within studies examining all cardiomyopathy patients, has demonstrated a statistically significant difference between ICD therapy and medical therapy in non-ischemic cardiomyopathy, although there has been a clear trend favoring ICD therapy [1]. It was through a meta-analysis of all studies in 2017 that a statistically significant benefit of ICDs in reducing overall mortality for non-ischemic cardiomyopathy was established [2].

The aforementioned studies did not employ the same concomitant therapies. The only study that achieved statistical significance was the COMPANION trial (Comparison of Medical Therapy, Pacing, and Defibrillation in Heart Failure), where ICDs were combined with cardiac resynchronization therapy (CRT), which most likely significantly contributed to the positive outcome. The study also found no difference between patients with cardiac resynchronization therapy defibrillator (CRT-D) devices and those with cardiac resynchronization therapy pacemaker (CRT-P) devices [3]. Similarly, the Sudden Cardiac Death in Heart Failure Trial (SCD-HeFT) explicitly noted that all patients were on optimal medical therapy at the time, which included beta-blockers, angiotensin-converting enzyme (ACE) inhibitors, and aldosterone antagonists [4]. It is well-known that mortality (both overall and sudden death) has been significantly reduced since the systematic introduction of these medications. Notably, this study demonstrated a significant reduction in mortality in the overall patient group with ICD therapy. However, when observing patients by New York Heart Association (NYHA) class, no difference between ICDs and placebo was found in NYHA class III patients (p = 0.3) [4]. The difference was present only in the NYHA class II group. Similarly, when analyzing only the subgroup with non-ischemic cardiomyopathy, although the number of patients was comparable to the ischemic cardiomyopathy group, the benefit of ICDs did not reach statistical significance, despite showing a positive trend [4].

The more recent Danish study (DANISH), with the longest follow-up period (9.5 years) and contemporary optimal medical therapy in the non-ischemic cardiomyopathy group, did not demonstrate a benefit of ICDs in reducing overall mortality compared to medical therapy [1]. However, some benefit was observed in patients under 70 years of age, while no benefit was seen in older patients [5, 6]. In this study, 58% of patients also received resynchronization therapy. The group older than 70 years had a slightly higher rate of CRT therapy (68%), which may have contributed to the reduced benefit of ICDs [7]. On the other hand, the ratio of sudden to non-sudden cardiac death (non-SCD) was lower in younger patients compared to older ones, which may also influence the results of ICD therapy. In the younger population (

Cardiomyopathy is not a homogeneous condition, and risk assessment depends on the type of cardiomyopathy (ischemic/non-ischemic). Even non-ischemic cardiomyopathy is not a uniform group, encompassing dilated, myocarditis, arrhythmogenic dysplasia, restrictive, hypertrophic, and other forms. Increasing evidence suggests that a standardized approach to all patients is inadequate, as reflected in the latest ESC guidelines for sudden death prevention, which have downgraded the indication for primary prophylaxis in non-ischemic cardiomyopathy to a IIa recommendation [8]. This has prompted calls for revisiting guidelines for ICD use in primary prevention in non-ischemic heart failure, since newer treatment of heart failure have been developed since the initial recommendations were established [4, 9].

There is growing evidence that reduced systolic function alone is not a precise predictor of whether ICD therapy will significantly impact mortality across all patients. In addition to age, the presence of myocardial fibrosis on cardiac magnetic resonance (CMR) imaging is now increasingly recognized as critical for assessing the risk of sudden death and the potential benefit of ICD therapy [10, 11, 12]. Most patients with ischemic cardiomyopathy have myocardial fibrosis, whereas this is not the case for non-ischemic cardiomyopathy.

In recent years, new medications, such as sacubitril/valsartan and sodium-glucose co-transporter-2 inhibitors, have been introduced and have resulted in a significant reduction of mortality beyond the benefits of standard medical therapy [13, 14].

In view of the conflicting results of existing studies, particularly in the non-ischemic cardiomyopathy group, the need for better stratification and even individualized therapy has been highlighted.

The aim of this study was to identify the characteristics of patients for whom ICD activation was justified and to determine whether certain clinical or laboratory parameters could better stratify patients who would derive greater benefit from ICD implantation.

This study was conducted on patients from the University Hospital Centre (UHC) Zagreb (the largest hospital in Croatia) who had an ICD or CRT-D implanted between 2009 and 2018. This period was chosen because, starting in 2009, the number of primary prevention implantations in our institution significantly increased, making it economically feasible to implement adequate primary prevention only from that point onward. It is important to note that UHC Zagreb, as the only national hospital, serves patients from across the Republic of Croatia. Most primary and secondary prevention procedures in Croatia are performed at this centre. This study was retrospective in nature.

Indications for ICD and CRT-D implantation were established according to the ESC guidelines at the time [15]. In almost the entire group, indications were limited to Class I recommendations of the guidelines. We randomly used Medtronic (Medtronic Parkway, Minneapolis, MN, USA), St. Jude (Danny Thomas Place, Memphis, TN, USA), and Biotronik (Biotronik Se & Co., Berlin, Germany) devices. Systolic function was expressed as the ejection fraction determined via echocardiography by a licensed specialist, while the type of cardiomyopathy (ischemic/non-ischemic) was determined through medical history, echocardiography, and coronary angiography (without significant coronary stenoses that would explain poor systolic function).

Each device was implanted by an experienced cardiologist under sterile conditions following professional standards. During the procedure, electrode parameters and final device programming were carried out in collaboration with authorized personnel from the device manufacturer. Follow-up was systematically conducted by the same team, recording all device parameters. In cases where therapy was activated, the reason for activation, the type, and the success of the therapy were documented. All data were entered into an Excel spreadsheet.

This was a retrospective study. Data was collected from archives pertaining to the day of implantation. Device check-ups and registration of changes in clinical parameters or adverse events (device activation, hospitalization, therapy changes) were performed annually or, towards the end of the device’s lifespan, every 3–6 months until device replacement. Follow-ups were conducted in outpatient clinics with the patient present. If the patient did not attend a scheduled follow-up, their status was checked with family members or the relevant state institution of their residence.

Statistical analysis was conducted using two software packages: SPSS v25 (IBM Corp. Released 2017. IBM SPSS Statistics for Windows, Version 25.0. Armonk, NY, USA), licensed to the Faculty of Medicine at the University of Zagreb, and Jamovi v2.5 (Jamovi Project (2024), Jamovi (Version 2.5) [Computer Software]. This software was retrieved from https://www.jamovi.org), which is open-source software.

The threshold for statistical significance (alpha, Type I error) was set at 0.05, and no correction for multiplicity was applied as the number of analyses did not require such an approach. Descriptive statistics for individual variables are presented as mean values with standard deviations (for ratio-scale variables) or as frequencies and counts (for nominal or ordinal-scale variables). Differences between observed groups were analysed using appropriate parametric or non-parametric tests, depending on the type and normality of the distribution of individual variables. Normality of distribution was tested using the Shapiro-Wilk test.

Survival analysis was performed in three ways: (1) a simple analysis of differences between two groups—deceased and surviving patients; (2) for variables that showed statistically significant differences between deceased and surviving patients, a Kaplan-Meier survival analysis was conducted; (3) finally, all variables were included as predictors in a Cox regression survival analysis.

A total of 786 individuals were included in this study. However, upon reviewer’s insisting on listwise missing cases deletion, the final sample size was 614 subjects. They were predominantly males (N = 512; 83.4%), with less of one-fifth of the participants being female (N = 102; 16.6%). The average age of participants at the time of implantation or inclusion in the study was 58.7

| Parameter | ||

| Age [years; M | 58.7 | |

| Gender [N; male (%)] | 512 (83.4%) | |

| Smoker [N; yes (%)] | 252 (41.0%) | |

| Ejection fraction [%; M | 31.4 | |

| NYHA class [N; (%)] | ||

| I | 125 (20.4%) | |

| II | 301 (49.0%) | |

| III | 174 (28.3%) | |

| IV | 14 (2.3%) | |

| Indication [N; (%)] | ||

| Cardiac arrest | 101 (16.4%) | |

| Low EF | 330 (53.7%) | |

| VT | 65 (10.6%) | |

| NSVT | 118 (19.2%) | |

| Concomitant medication [N; (%)] | ||

| Beta-blocker | 565 (92.0%) | |

| ACEi/ARB | 475 (77.4%) | |

| Amiodaron | 227 (37.0%) | |

SD, standard deviation; NYHA, New York Heart Association; EF, ejection fraction; VT, ventricular tachycardia; NSVT, non-sustained ventricular tachycardia; ACEi, angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitor; ARB, angiotensin receptor blocker.

All participants had a device implanted between January 2009 and February 2018. The end of the follow-up period was determined to be December 31, 2019. The mean follow-up duration was 52.9

The majority of participants (N = 565; 92.0%) were taking beta-blockers, followed by angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors/angiotensin receptor blockers (N = 475; 77.4%), amiodarone (N = 227; 37.0%) (Table 1).

Depending on the indication, either an ICD (N = 478; 77.9%) or a CRT-D (N = 136; 22.1%) device was implanted. ICD devices were mostly (N = 450; 94.1%) single-chamber type devices, while CRT-D devices were mostly (N = 111; 81.6%) dual-chamber type devices.

The indication for device implantation was a previous cardiac arrest (N = 101; 16.4%), reduced ejection fraction (N = 330; 53.7%), ventricular tachycardia (N = 65; 10.6%), or non-sustained ventricular tachycardia (NSVT) (N = 118; 19.2%). All participants had some form of cardiomyopathy, 286 participants (46.6%) had ischemic and 328 participants (53.4%) had non-ischemic cardiomyopathy.

Other pre-implantation parameters, including electrocardiogram (ECG) parameters and comorbidities, are shown in Table 2. The majority of participants had a history of hypertension (65.3%), decompensation (59.4%), and myocardial infarction (39.4%), while diabetes (27.2%) and thyroid diseases (17.8%) were less common. Electrocardiogram parameters included ventricular tachycardia (60.9%), left bundle branch block (34.5%), atrial fibrillation/flutter (30.9%), and ventricular fibrillation (13.5%). Table 3 presents the distribution of patients based on the types of cardiomyopathy observed in the study cohort. The majority of cases are categorized as ischemic or non-ischemic cardiomyopathy, with non-ischemic cardiomyopathy further subdivided into specific types, including dilated cardiomyopathy, arrhythmogenic right ventricular dysplasia, and other less common forms.

| Parameter [N; yes (%)] | |

| ECG – Ventricular tachycardia | 374 (60.9%) |

| ECG – Ventricular fibrillation | 83 (13.5%) |

| ECG – Atrial fibrillation/undulation | 190 (30.9%) |

| ECG – Left bundle branch block | 212 (34.5%) |

| History of myocardial infarction | 242 (39.4%) |

| History of decompensation | 365 (59.4%) |

| Hypertension | 401 (65.3%) |

| Diabetes | 167 (27.2%) |

| Thyroid condition | 109 (17.8%) |

ECG, electrocardiogram.

| Type of CMP | Counts | % of Total |

| Thyrotoxic | 1 | 0.2% |

| Toxic | 4 | 0.7% |

| ARVD | 5 | 0.8% |

| Non-compaction | 9 | 1.5% |

| General rhythm | 15 | 2.4% |

| Dilatative | 97 | 15.8% |

| Non-ischemic | 197 | 32.1% |

| Ischemic | 286 | 46.6% |

CMP, cardiomyopathy; ARVD, arrhythmogenic right ventricular dysplasia.

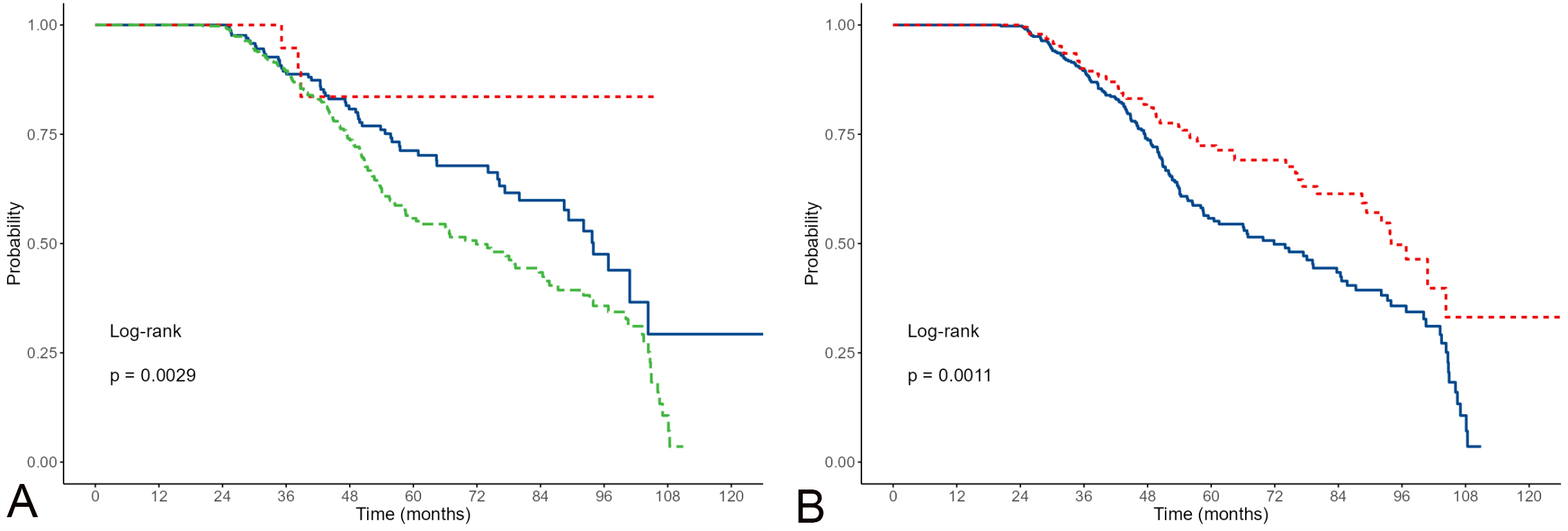

One of the study’s objectives was to thoroughly investigate the appropriateness of device activation in relation to other available parameters in the study. In the majority of participants (N = 428; 69.7%), the device did not activate. Of the remaining 186 participants (30.3%) whose device activated, the activation was appropriate in the vast majority of cases (N = 164; 88.2%), and inappropriate in only 11.8% (N = 22) of participants. Fig. 1 shows the survival results concerning different device activation parameters. There was a statistically significant (p

Fig. 1.

Fig. 1. Kaplan-Meier estimates of survival for appropriate/non-appropriate activations including non-activations. (A, appropriate are red; inappropriate green; non-activations blue); and appropriate/non-appropriate activations excluding non-activations (B, appropriate activations are red; non-activations blue).

In addition to the descriptive data presented in the previous tables, the study was designed to answer several additional questions regarding device activation, the results of which will be described in this section.

When device activation is considered as a binary variable, disregarding appropriateness and looking solely at the presence (N = 186; 30.3%) or absence (N = 428; 69.7%) of activation, outcomes for several key variables were observed. There were no statistically significant differences (p = 0.642; chi-square test) in the type of cardiomyopathy (ischemic vs. non-ischemic). This difference became marginally statistically significant (p = 0.049) when considering the appropriateness of activation, with a significantly higher percentage of inappropriate activations in non-ischemic cardiomyopathies (5.5%) compared to ischemic ones (1.7%), while for appropriate activations, the situation is reversed with 28.7% appropriate activations in ischemic patients and 26.5% in non-ischemic ones. The proportion of participants without activation is similar between the 2 groups (69.6% in ischemic vs. 68.0% non-ischemic cases). A statistically significant differences were also present for type of prevention (primary vs. secondary cases). When considering only the presence of activation, the proportion of activation was higher in individuals with secondary prevention (39.7% vs. 27.2%; p = 0.004; chi-square test). When considering the appropriateness of activation, inappropriate activations were significantly higher (5.0%) in primary prevention compared to secondary prevention participants (0.0%). For appropriate activations, the situation was reversed with 39.7% appropriate activations in secondary and 23.5% in primary prevention participants.

When only the appropriateness of activation is considered as an outcome, either appropriate (N = 169; 88.0%) or inappropriate (N = 23; 12.0%), the profiles of both groups of participants are shown in the Table 4. The statistical significance of the differences is shown in the “p” column. Appropriate activation was found to be statistically significant.

| Parameter | Appropriate (N = 169) | Inappropriate (N = 23) | p | |

| Age [years; M | 57.6 | 50.3 | ||

| Gender [N; male (%)] | 143 (84.6%) | 21 (91.3%) | 0.591 | |

| Smoker [N; yes (%)] | 67 (39.6%) | 9 (39.1%) | 0.962 | |

| Ejection fraction [%; M | 33.0 | 31.5 | 0.590 | |

| NYHA class [N; (%)] | ||||

| I | 43 (25.4%) | 4 (17.4%) | 0.138 | |

| II | 83 (49.1%) | 15 (65.3%) | ||

| III | 42 (24.9%) | 3 (13.0%) | ||

| IV | 1 (0.6%) | 1 (4.3%) | ||

| Indication [N; (%)] | ||||

| Cardiac arrest | 37 (21.9%) | 0 (0.0%) | 0.027 | |

| Low EF | 62 (36.7%) | 17 (73.9%) | ||

| VT | 32 (18.9%) | 2 (8.7%) | 0.227 | |

| NSVT | 39 (23.1%) | 4 (17.4%) | 0.539 | |

| Concomitant medication [N; (%)] | ||||

| Beta-blocker | 155 (91.7%) | 23 (100.0%) | 0.314 | |

| ACEi/ARB | 126 (74.6%) | 19 (82.6%) | 0.559 | |

| Amiodaron | 70 (41.4%) | 5 (21.7%) | 0.070 | |

| ECG – Ventricular tachycardia | 137 (81.1%) | 11 (47.8%) | ||

| ECG – Ventricular fibrillation | 30 (17.8%) | 0 (0.0%) | 0.058 | |

| ECG – Atrial Fibrillation/undulation | 45 (26.6%) | 13 (56.5%) | 0.003 | |

| ECG – Left bundle branch block | 53 (31.4%) | 3 (13.0%) | 0.117 | |

| History of myocardial infarction | 67 (39.6%) | 5 (21.7%) | 0.096 | |

| History of decompensation | 96 (56.8%) | 12 (52.2%) | 0.674 | |

| Hypertension | 99 (58.6%) | 14 (60.9%) | 0.834 | |

| Diabetes | 39 (23.1%) | 8 (34.8%) | 0.221 | |

| Thyroid condition | 36 (21.3%) | 3 (13.0%) | 0.517 | |

| Cardiomyopathy [N; ischemic (%)] | 82 (48.5%) | 5 (21.7%) | 0.015 | |

| Prevention [N; (%)] | ||||

| Primary | 109 (64.5%) | 23 (100.0%) | ||

| Secondary | 60 (35.5%) | 0 (0.0%) | ||

The statistical significance of the differences, as indicated in the “p” column, reveals that appropriate activation was statistically significant in subjects who were older, had a history of cardiac arrest, lower ejection fraction (EF), took amiodarone, had ventricular tachycardia or ventricular fibrillation on ECG, a history of myocardial infarction, or ischemic cardiomyopathy.

To additionally analyse the impact of various parameters on the appropriateness and/or presence of activation, binary and multinomial regression analyses were conducted.

In the multinomial regression analysis model using the forward stepwise method, i.e., when activation was considered by the model as non-activated/appropriate/inappropriate, none of the models reached an R2 value above 0.05, so these models will not be further considered. However, in the binary logistic regression model where the outcome was the appropriateness of activation (appropriate/inappropriate; N = 192), the forward stepwise method found models with the following number of predictors:

(1) Ventricular tachycardia in ECG (R2 = 0.106),

(2) Ventricular tachycardia in ECG, prevention (R2 = 0.244),

(3) Ventricular tachycardia in ECG, prevention, atrial fibrillation/undulation in ECG (R2 = 0.310).

Ventricular tachycardia in ECG, prevention, atrial fibrillation/undulation in ECG, Left bundle branch block in ECG (R2 = 0.371). We began the survival analysis with the most straight-forward method, examining the differences between surviving and deceased patients across all available parameters in the study. The results are presented in Table 5.

| Parameter | Alive (N = 389) | Deceased (N = 225) | p | |

| Age [years; M | 56.1 | 63.2 | ||

| Gender [N; male (%)] | 321 (82.5%) | 191 (84.9%) | 0.447 | |

| Smoker [N; yes (%)] | 167 (42.9%) | 85 (37.8%) | 0.211 | |

| Ejection fraction [%; M | 32.6 | 29.3 | ||

| NYHA class [N; (%)] | ||||

| I | 95 (24.4%) | 30 (13.3%) | ||

| II | 200 (51.4%) | 101 (44.9%) | ||

| III | 87 (22.4%) | 87 (38.7%) | ||

| IV | 7 (1.8%) | 7 (3.1%) | ||

| Indication [N; (%)] | ||||

| Cardiac arrest | 62 (15.9%) | 39 (17.3%) | 0.653 | |

| Low EF ( | 199 (51.2%) | 131 (58.2%) | 0.091 | |

| VT | 46 (11.8%) | 19 (8.4%) | 0.190 | |

| NSVT | 82 (21.1%) | 36 (16.0%) | 0.124 | |

| Concomitant medication [N; (%)] | ||||

| Beta-blocker | 356 (91.5%) | 209 (92.9%) | 0.545 | |

| ACEi/ARB | 295 (75.8%) | 180 (80.0%) | 0.235 | |

| Amiodaron | 130 (33.4%) | 97 (43.1%) | 0.017 | |

| ECG – Ventricular tachycardia | 244 (62.7%) | 130 (57.8%) | 0.226 | |

| ECG – Ventricular fibrillation | 53 (13.6%) | 30 (13.3%) | 0.919 | |

| ECG – Atrial fibrillation/undulation | 112 (28.8%) | 78 (34.7%) | 0.129 | |

| ECG – Left bundle branch block | 128 (32.9%) | 84 (37.3%) | 0.266 | |

| History of myocardial infarction | 143 (36.8%) | 99 (44.0%) | 0.077 | |

| History of decompensation | 212 (54.5%) | 153 (68.0%) | 0.001 | |

| Hypertension | 242 (62.2%) | 159 (70.7%) | 0.034 | |

| Diabetes | 90 (23.1%) | 77 (34.2%) | 0.003 | |

| Thyroid condition | 67 (17.2%) | 42 (18.7%) | 0.652 | |

| Cardiomyopathy [N; ischemic (%)] | 160 (41.1%) | 126 (56.0%) | ||

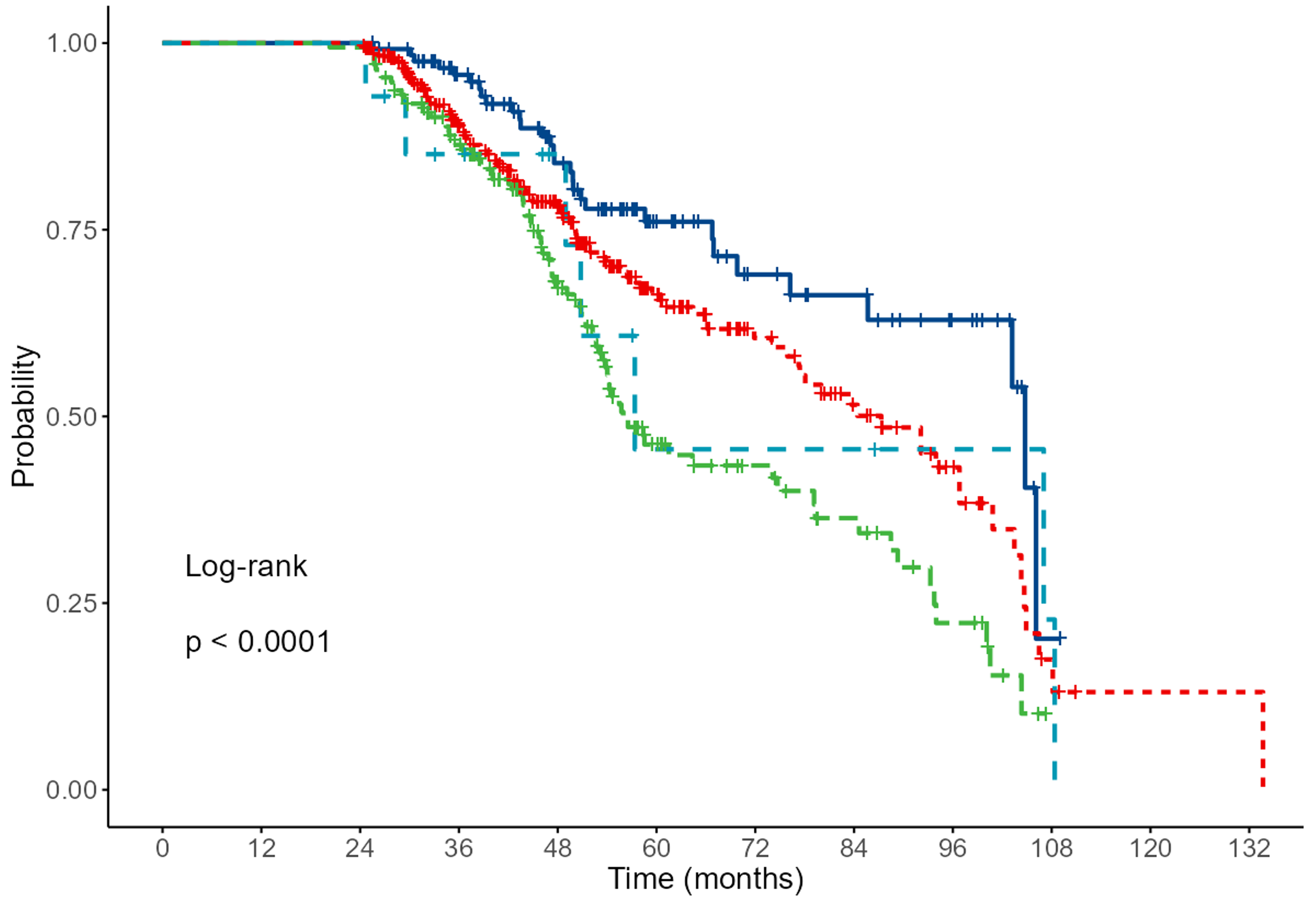

As the next step, we applied the Kaplan-Meier method (Fig. 2) to nominal or ordinal variables that showed statistical significance in the previous table. The results are presented in the graphs below.

Fig. 2.

Fig. 2. Results of Kaplan-Meier analysis for NYHA. Grade 1 (dark blue), 2 (red), 3 (green) and 4 light blue (p

Finally, the Cox regression survival analysis resulted in 3 models: the first model included only age as a predictor, the second model included both age and non-sustained ventricular tachycardia, and the third model adds a history of decompensation as an additional predictor (Table 6).

| Model | Variables | B | SE | Wald | p | Exp(B) | 95% CI |

| 1 | age | 0.037 | 0.006 | 39.705 | 0 | 1.038 | 1.026–1.050 |

| 2 | age | 0.037 | 0.006 | 39.190 | 0 | 1.038 | 1.026–1.050 |

| ventricular tachycardia in ECG | –0.791 | 0.141 | 31.626 | 0 | 0.454 | 0.344–0.597 | |

| 3 | age | 0.037 | 0.006 | 36.370 | 0 | 1.037 | 1.025–1.050 |

| ventricular tachycardia in ECG | –0.794 | 0.140 | 31.959 | 0 | 0.452 | 0.343–0.595 | |

| history of decompensation | 0.464 | 0.144 | 10.429 | 0.001 | 1.591 | 1.200–2.109 | |

| 4 | age | 0.038 | 0.006 | 38.034 | 0 | 1.038 | 1.026–1.051 |

| indication of VT | 0.808 | 0.205 | 15.505 | 0 | 2.243 | 1.501–3.354 | |

| ventricular tachycardia in ECG | –0.984 | 0.153 | 41.557 | 0 | 0.374 | 0.277–0.504 | |

| history of decompensation | 0.574 | 0.148 | 15.091 | 0 | 1.775 | 1.329–2.371 |

The first 5 studies on primary mortality prevention in patients with cardiomyopathy mostly demonstrated a positive impact of ICD on mortality (MADIT I and II, MUSTT). However, the CABG-Patch and CAT studies did not achieve statistical significance, though the CAT study showed a positive trend in the ICD group. It is believed that the potential reason for this is the positive impact of revascularization, while in the CAT study, which investigated non-ischemic cardiomyopathy, mortality was significantly lower than expected (5.6%, expected 30%). Furthermore, the number of patients in the study was relatively small. To increase the study’s power by increasing the number of patients, a meta-analysis was conducted. This meta-analysis showed a statistically significant 34% reduction in mortality in the ICD group. However, when the non-randomized MUSTT study was excluded, there was no statistical significance in overall mortality between groups (p = 0.124), though a difference was observed when considering arrhythmic death alone (p

Subsequently, 5 newer studies were published (AMIOVIRT, DEFINITE, COMPANION, DINAMIT, and SCD-HeFT). The first 2 studies focused solely on non-ischemic cardiomyopathy, while the other 3 examined either ischemic cardiomyopathy or cardiomyopathy in general. In the studies on non-ischemic cardiomyopathy, there was no statistically significant difference in mortality between the group receiving optimal medical therapy and the ICD group, although the DEFINITE study showed a trend toward lower mortality in the ICD group (13.8% vs. 8.1%) with a 41% relative risk (RR) reduction, albeit without statistical significance (p = 0.081). It should be noted that follow-up in these 2 studies was up to 3 years.

The COMPANION study was primarily based on the impact of resynchronization therapy on mortality, so all patients had a prolonged QRS complex (

The last and largest study, SCD-HeFT, with a follow-up of 4 years, showed a significant reduction in mortality in the ICD group (p = 0.007) with a 24% RR reduction. Mortality in the ICD group was 22%, compared to 28% in the amiodarone group and 29% in the control group. However, a subgroup analysis by NYHA classification showed significant differences only in the NYHA II group (p

In the group of patients with the lowest baseline risk, ICD reduced the risk of sudden death by 88% and total mortality risk by 54%, while in the group with the highest baseline risk, sudden death mortality was reduced by 24%, and total mortality by only 2%. A meta-analysis of all studies showed a 25% reduction in overall mortality RR in the ICD group (p = 0.003). Overall mortality in the ICD group was 18.5%, compared to 26.4% in the control group.

The Danish study on the efficacy of ICDs in non-ischemic cardiomyopathy did not show a reduction in overall mortality in the ICD group compared to the group receiving optimal medical therapy. The average age of patients was 63 years (21–84), with an average follow-up period of 5.6 years. Sub-analysis revealed that in the group

In the

Compared to the Danish study, the population in our study was younger (58.7 years) with a significantly smaller proportion of patients older than 70 years and a slightly shorter follow-up period (4.5 years). Most patients were on optimal medical therapy, with a relatively high percentage also receiving amiodarone (37.0%). This may be related to the initially relatively high incidence of atrial fibrillation/flutter and attempts to control ICD activation during a period when atrial fibrillation, ablation and ventricular tachycardia ablation for structural heart disease were not widely available in our country. The proportion of patients in NYHA class III was slightly higher than in other primary prevention studies. ICD activation did not occur in 69.7% of patients, a slightly lower percentage than in other studies, which could be explained by the inclusion of more severe patients, i.e., a higher proportion of those in NYHA class III, and slightly longer follow-up. In the SCD-HeFT study, mortality in the NYHA III group was almost double that in the NYHA II group.

Among patients with device activation in our study, 12.0% of activations were inappropriate (3.7% of the total population with implanted ICDs), which is similar to the Danish study (5.9%). Inappropriate shocks were mostly due to supraventricular rhythm disorders (AF, atrial flutter, SVT, sustained ventricular tachycardia) and, in fewer cases, technical issues, predominantly involving the lead (fracture, electromagnetic interference, inadequate grounding). All causes were successfully resolved (AF, atrial flutter, or SVT ablation, atrioventricular (AV) node ablation, lead replacement) without further adverse events.

Inappropriate ICD activation was significantly more common in non-ischemic cardiomyopathy (5.5% vs. 1.7%), while the opposite was true for appropriate activations (26.5% vs. 28.7%). When examining the profile of patients with inappropriate activations, it was significantly more common among those who initially did not have ventricular rhythm disturbances, with the indication being solely reduced ejection fraction. Furthermore, inappropriate activation was significantly lower among patients taking amiodarone and those with initial ECG findings of ventricular tachycardia (VT)/ventricular fibrillation (VF) or a history of myocardial infarction. These patients were initially prescribed amiodarone, which likely contributed to fewer inappropriate activations (suppression of supraventricular arrhythmias and slowing of SVT/VT below detection thresholds). Conversely, patients with reduced EF alone were not prescribed antiarrhythmic therapy initially and only received it after inappropriate activation due to AF/flutter, supported by the fact that inappropriate activations were more frequent in patients with recorded AF/flutter.

Patients with ischemic cardiomyopathy were more likely to have severe arrhythmias and were thus prescribed antiarrhythmic therapy earlier, which might have reduced the frequency of arrhythmias and ventricular response below detection thresholds.

Mortality in our study was 36.6%. In the ischemic cardiomyopathy group, 46.6% of patients died, while significantly fewer patients died in the non-ischemic cardiomyopathy group (28.5%). Deceased patients were significantly older, had more severe cardiomyopathy (lower EF, higher NYHA class), and ischemic cardiomyopathy. In the Danish study of non-ischemic cardiomyopathy, mortality was only slightly lower (21.6%) compared to our study, which could be explained by the higher proportion of patients receiving concomitant resynchronization therapy (58% compared to 22.1% in our study). Higher mortality among older patients and those with poorer functional status were observed not only in the Danish study but also in meta-analyses of all primary prevention studies.

In line with these findings, our Cox regression analysis demonstrated that combined predictors of mortality despite ICD implantation were age and a history of heart failure. The presence of NSVT, which also contributes to increased mortality, is harder to explain. However, NSVT in this group could indicate more severe structural heart disease or represent a confounding factor not considered in this study (e.g., side effects of certain antiarrhythmic therapies).

It is unquestionable that ICD reduces sudden death, but there is increasing evidence that better patient stratification is needed to maximize the benefits of ICD therapy. Candidates for ICD implantation should be those with a higher risk of sudden death and lower risk of non-arrhythmic mortality. ICD implantation involves both acute and chronic complications in nearly 20% of patients. According to current guidelines, more than 70% of patients recommended for ICD implantation did not require ICD therapy. Therefore, they did not benefit from this therapy but were exposed to its adverse effects. Furthermore, in most studies, mortality with ICD implantation ranged from 15–20%.

In light of new heart failure drug therapies introduced in recent years, which have demonstrated reduced overall mortality on top of standard therapies, better risk stratification would be desirable, particularly for ischemic and especially non-ischemic cardiomyopathy. There is increasing evidence that myocardial fibrosis detected by cardiac magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) indicates high risk status regardless of systolic function. Patients with ischemic cardiomyopathy generally exhibit significant fibrosis, while this is not typically the case in non-ischemic cardiomyopathy. In a meta-analysis of non-ischemic cardiomyopathy patients [16], the annual rate of malignant arrhythmias was 6.9% in patients with myocardial fibrosis, compared to 1.6% in those without fibrosis, regardless of systolic function (EF

With newer medical and invasive heart failure therapies, an aging population with more comorbidities, and advanced imaging, risk stratification studies based solely on systolic function may no longer be adequate. Until new studies are published (some involving cardiac MRI are ongoing), current guidelines remain in place. However, the indication for ICD therapy should still be individualized, especially for non-ischemic cardiomyopathy. Consideration should be given to whether ICD implantation is justified in older patients (

Although ICDs and CRT-D devices are effective in sudden cardiac death, their impact on overall mortality depends on multiple factors, including patient age and type of heart disease. This study suggests that younger patients benefit more from the implantation of the device than the older patient population. In elderly patients

This study had several limitations. The study was retrospective, and thus limited to the predefined available parameters. Additional parameters could not be observed as this would result in incomplete findings. The study did not include a control group, as all patients had an ICD implanted. Furthermore, the cause of death (sudden or non-sudden) was unknown, though this was less relevant since all patients had an ICD implanted. Longer follow-up would provide a better assessment of the adequacy of therapy, as some studies achieved significance only after several years of follow-up. However, we believe that these limitations are not critical and do not significantly impact the results or the conclusions drawn from the findings.

All raw data reported in this paper will also be shared by the lead contact upon request.

MP and VV designed the research study. EC, MDD, VP, IP, RM, MK, BPN performed the research. DP, DM provided help and advice on design of study and did follow up and analysis of data. PH analyzed the data. MP, AB, MLB wrote the manuscript and participated in experiments. All authors contributed to editorial changes in the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript. All authors have participated sufficiently in the work and agreed to be accountable for all aspects of the work.

The study was carried out in accordance with the guidelines of the Declaration of Helsinki and approved by the Ethics Committee of University Hospital Centre Zagreb (Protocol Class 8.1-24/2022, No 02/013AG). As study was retrospective, there was no informed consent.

Not applicable.

This research received no external funding.

The authors declare no conflict of interest. Vedran Velagic is serving as Guest Editor of this journal. We declare that Vedran Velagic had no involvement in the peer review of this article and has no access to information regarding its peer review. Full responsibility for the editorial process for this article was delegated to Matteo Bertini.

References

Publisher’s Note: IMR Press stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.