1 Institute for Cardiometabolic Medicine, University Hospitals Coventry & Warwickshire NHS Trust, CV2 2DX Coventry, UK

2 Centre for Healthcare & Communities, Coventry University, CV1 5FB Coventry, UK

3 Warwick Medical School, University of Warwick, CV4 7HL Coventry, UK

†These authors contributed equally.

Abstract

The global prevalence of atrial fibrillation (AF) is growing with a significant increase in AF burden. The pathophysiology of AF is complex and exhibits a strong relationship with modifiable lifestyle AF risk factors, such as physical inactivity, smoking, obesity, and alcohol consumption, as well as co-morbidities, such as hypertension, diabetes mellitus, and cardiovascular disease. Current evidence suggests that cardiac rehabilitation and lifestyle risk factor modification can potentially lower the overall AF burden. Additionally, AF ablation can be an effective treatment for a rhythm control strategy, but reducing AF recurrences post-catheter ablation is paramount. Thus, addressing these modifiable lifestyle risk factors and co-morbidities is critical, as the recent 2024 European Society of Cardiology AF guidance update highlights. A comprehensive approach to treating these risk factors is essential, especially given the rising prevalence of AF. This article provides a state-of-the-art update on the evidence of addressing AF-related risk factors and co-morbidities, particularly in patients undergoing AF ablation.

Keywords

- atrial fibrillation

- risk factor modification

- cardiac rehabilitation

- AF ablation outcome

Atrial fibrillation (AF) is the most common cardiac arrhythmia. Further, AF represents an ever-growing global epidemic, with estimates demonstrating that more than 59 million individuals lived with AF globally in 2019, and the prevalence has doubled over the previous two decades [1, 2]. This trend was confirmed in international data, demonstrating a clear rise in costs and burden on healthcare systems because of increased morbidity and all-cause mortality, largely driven by thromboembolic events (i.e., stroke, myocardial infarction), cognitive decline, and heart failure (HF) [2, 3, 4]. Subsequently, this trend has been partially explained by advances in detection modes and improved survival but also due to the increased accumulation of co-morbidities that comprise AF risk factors [3]. While the pathogenesis of AF has a genetic component, environmental and lifestyle risk factors and co-existing medical and cardiovascular (CV) conditions play a major role by contributing to the electrical, structural, and functional remodeling of the heart [5, 6]. Suboptimal management of these risk factors can lead to increased arrhythmia burden, disease progression, and incidence of adverse events associated with AF [7].

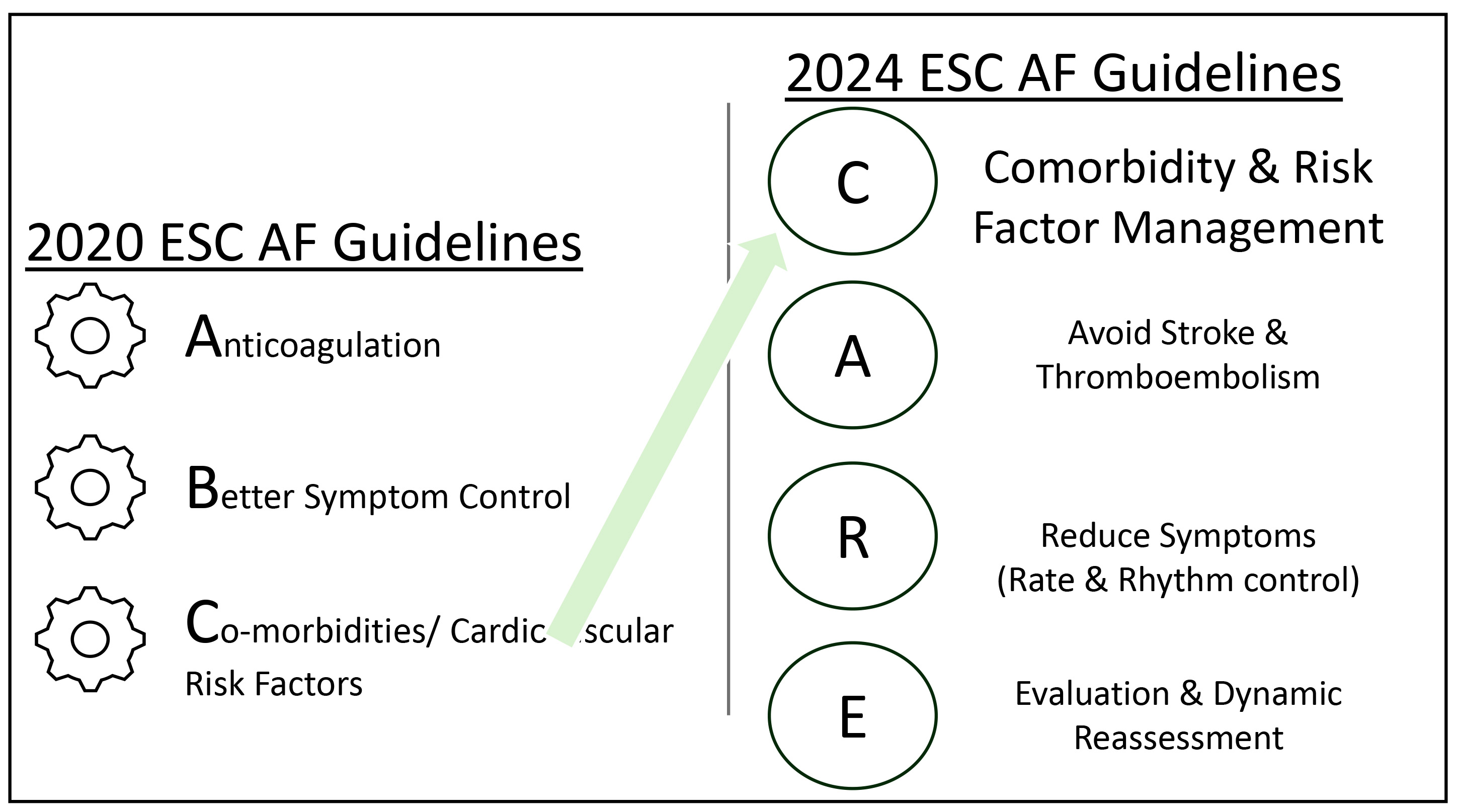

Historically, AF management primarily emphasized thromboembolic risk reduction and HF prevention through rate and rhythm control strategies [8, 9]. However, there has been a recent paradigm shift, with current international guidelines prioritizing the management of co-morbidities and risk factor modification to optimize patient outcomes [7, 10]. Indeed, the recent 2024 European Society of Cardiology (ESC) updated AF guidelines [7] advocate for the Co-morbidity, Avoid stroke, Reduce symptoms, Evaluation (CARE) approach (Fig. 1, Ref. [7]), placing increasing emphasis on the careful search for co-morbidities and risk factors and applying the strategy in all patients diagnosed with AF as a priority. Middeldorp et al. [11] have shown that the progression of AF from occasional episodes to persistent, long-standing persistent, and ultimately permanent forms can be halted and reversed by addressing these underlying risk factors. Despite the growing evidence supporting the critical role of risk factor modification, there is also evidence that these risk factors are often overlooked as presented in real-world data [12].

Fig. 1.

Fig. 1. The change in approach to atrial fibrillation management, as demonstrated in the 2024 ESC AF guideline update with prioritization of co-morbidities and AF risk factor management (adapted from the ESC 2024 Guidelines [7]). AF, atrial fibrillation; ESC, European Society of Cardiology.

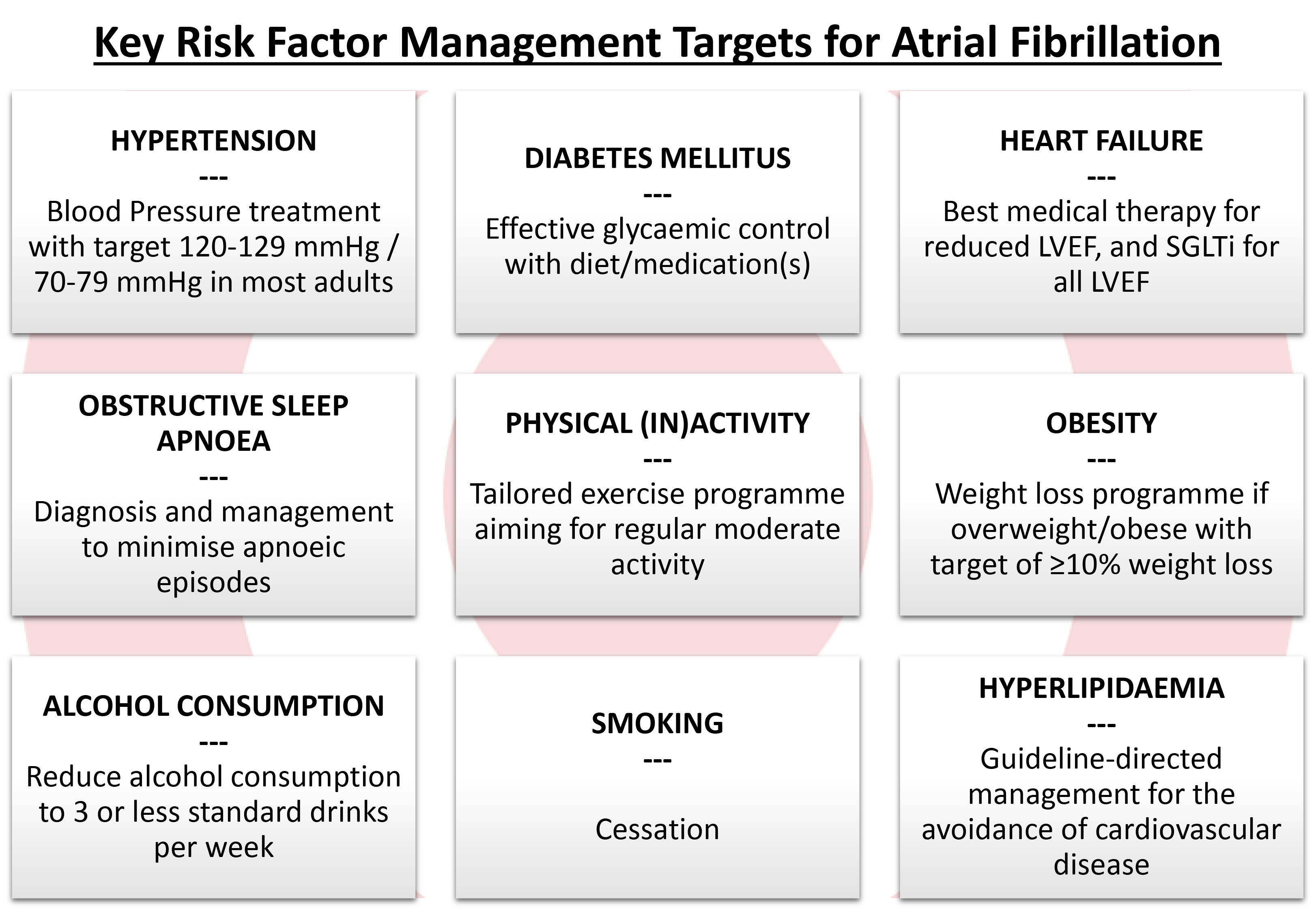

This review article aims to provide an update on the current evidence regarding the impact of risk factor management on outcomes, especially following AF ablation, in light of the renewed emphasis on AF risk factor modification, as highlighted by the 2024 International Consensus Statement and 2024 ESC AF guidelines [7, 13] (see Fig. 2, Ref. [7]).

Fig. 2.

Fig. 2. Key risk factors for atrial fibrillation and their management targets (adapted from ESC 2024 AF Guidelines [7]). LVEF, left ventricular ejection fraction; SGLTi, sodium-glucose co-transporter 2 inhibitor; AF, atrial fibrillation; ESC, European Society of Cardiology.

Over the last two decades, landmark studies have emphasized AF management through symptom reduction; however, the rationale for long-term rhythm control therapy has recently evolved [7]. Studies had initially found no mortality benefit and potentially increased hospitalization with pharmacological rhythm control versus rate-control [14, 15]; conversely, multiple studies demonstrated the positive impact of rhythm control strategies on quality of life when sinus rhythm was maintained [16, 17, 18]. In 2020, the EAST-AFNET 4 trial [19] demonstrated the benefit of an early rhythm control strategy in patients whose AF was

Over the last 30 years, evidence for catheter ablation of AF as a viable first-line option for AF management has evolved [20, 21] and has demonstrated benefits with or without AAD [22, 23, 24, 25, 26, 27, 28, 29]. In the EAST-AFNET 4 trial, at a 2-year follow-up, 19% of the early rhythm control arm had received catheter ablation [19]. In the CABANA trial [16], which compared catheter ablation with AAD in the treatment of symptomatic AF, the authors demonstrated no significant difference in the primary composite outcome of death, disabling stroke, serious bleeding, or cardiac arrest over a median 4-year follow-up. However, when interpreting the results of this study, one must consider the estimated treatment effect, which was affected by lower-than-expected event rates and treatment crossovers, with 27.5% of the drug therapy arm ultimately receiving catheter AF ablation. Furthermore, secondary outcomes (death or CV hospitalization and AF recurrence) significantly favored catheter ablation. A recent review [30] found catheter AF ablation as a first-line therapy for AF was associated with significant improvements in arrhythmia-related outcomes, symptoms, quality of life, and lower rates of adverse events. Primarily designed as an adjunct to cardiac surgical patients to reduce stroke risk in atrial fibrillation patients, left atrial appendage (LAA) ligation was shown to modify the atrial structural and electrical properties influencing AF dynamics [31, 32]. Subsequently, the role of the LAA has been explored as an arrhythmogenic focus, indicating that LAA ligation can potentially reduce AF triggers but may also create new substrates in some individuals [31, 32, 33, 34]. With the increasing accessibility to percutaneous methods for LAA ligation, the recent aMAZE trial, comparing adjunctive LAA ligation with pulmonary vein isolation (PVI) to PVI alone, met safety and closure efficacy, but did not meet prespecified efficacy for freedom from atrial arrhythmias at 12 months [35]. Catheter ablation, similar to many cardiac interventional procedures, is not without risk and carries a variable success rate of 40–80% for a first-time procedure, depending on AF type and an individual’s other clinical factors [36, 37]; paroxysmal AF carries a higher success rate (70–80%) compared with persistent and long-standing persistent AF (40–60%). AF catheter ablation also has demonstrable attrition at follow-up, with estimated AF recurrence rates of single-procedures reaching up to 30–70% at longer-term follow-ups [36, 38], with repeat ablations often required to achieve higher success rates [36, 37, 38, 39]. This has been especially noted in those with persistent AF and those with multiple co-morbidities and attributable risk factors for AF.

With healthcare systems evaluating treatments for sustainability, including cost-effectiveness, lower success rates with known attrition over time can significantly impact decisions and willingness to pay for expensive therapies, raising concerns about exactly who and how many patients can undergo an AF ablation procedure. Catheter ablation can be a cost-effective treatment strategy for patients with AF, particularly those with early-onset AF, as it may delay progression to more advanced forms of the condition. Therefore, greater utilization of ablation, especially in earlier stages of disease, can potentially deliver both clinical and economic benefits [40].

Atrial cardiomyopathy is widely recognized as a substrate for arrhythmic recurrences when aiming for rhythm control; however, evidence suggests that catheter ablation alone may not address this progressive atrial substrate remodeling [41]. Moreover, targeting additional atrial substrate during the initial AF ablation offers no advantage over PVI alone, suggesting its limited effect on post-ablation atrial remodeling [7]. Conversely, emerging evidence demonstrates the impact of AF risk factors on the progression and potential reversibility of the underlying atrial substrate. The following sections discuss the roles of various AF risk factors and their influence on the pathogenesis, incidence, and recurrence of AF, particularly in AF ablation.

The Framingham Heart study estimated that the presence of hypertension increased the likelihood of developing AF by 40–50% [42]. In an ovine model, hypertension has been associated with early and progressive changes in atrial remodeling [43, 44]. Indeed, left ventricular hypertrophy and stiffening, reduced diastolic filling and increased left atrial (LA) volumes because of the increased afterload with hypertension; LA dilatation, reduced LA function, adverse electrophysiological changes, and increased interstitial inflammation and fibrosis, which all serve as substrates for AF.

The blood pressure (BP) control target suggests strict control, avoiding hypertensive ranges [45]. A dose-response relationship has been demonstrated, showing a greater reduction in the risk of new AF with lower systolic BP (SBP): a SBP 131–141 mmHg and SBP

When assessing outcomes of AF ablation, multiple studies have shown hypertension, and especially uncontrolled hypertension, was independently associated with and a predictor for AF recurrence [53, 54, 55, 56, 57]. Zylla et al. [58] explored long-term outcomes of the German Ablation Registry of 626 patients; patients with hypertension were older, had more CV co-morbidities, and presented with more persistent forms of AF. Though the study found no statistical difference in AF recurrence rates, freedom from AAD, and requirement for repeat ablation, hypertensive patients had higher hospitalization rates and complained of more dyspnea and angina. Similar to the optimal range for blood pressure in patients with AF, the SMAC-AF study [59] demonstrated aggressive BP (target

Randomized clinical trials have investigated the effects of combining renal denervation (RDN) and PVI in patients with AF and hypertension. Pokushalov et al. [60] considered patients with refractory symptomatic AF and resistant hypertension, demonstrating that the addition of RDN to PVI resulted in significantly higher rates of freedom from AF recurrence at 12 months, alongside notable reductions in blood pressure, compared to PVI alone. Similarly, the ERADICATE-AF trial [61], which focused on patients with paroxysmal AF and sub-optimally controlled hypertension, showed that combining RDN with PVI led to a significant reduction in AF recurrence, AF burden, and blood pressure levels relative to PVI alone. These findings suggest that RDN, when performed in conjunction with catheter ablation, may offer enhanced rhythm control and improved clinical outcomes in hypertensive AF patients, likely through modulation of sympathetic nervous system activity. Further large-scale studies are warranted to confirm these results and establish the long-term efficacy and safety of this combined approach. Furthermore, a lack of sham procedure controls for the RDN components in these studies represents a criticism, as this feature affected outcomes of renal denervation trials solely focused on hypertension management.

Individuals with diabetes mellitus (DM) have a significantly higher likelihood of developing AF, with a meta-analysis of 31 studies, including more than 10 million participants, demonstrating a dose-response relationship between incremental blood glucose and the risk of AF [62]. Estimates concluded a 20% increase in the pre-diabetic range and 28% with diagnosed DM. The ARIC study [63] described each 1% rise in HbA1c drove a 13% higher risk of AF. A registry-based cohort study concluded that DM was associated with an overall 35% higher risk than age- and sex-matched controls during a 13-year follow-up [64]. This study also suggested excess risk for AF, where there was the presence of poor glycemic control and evidence of renal complications. Similarly, the Framingham Heart Study [65] demonstrated an associated risk of DM with AF, as high as 40% in men and 60% in women. The risk from DM is likely multi-faceted, with mechanisms including mitochondrial dysfunction, oxidation, fibrosis, inflammatory fatty accumulation and infiltration, impairment of calcium transport, and thrombogenesis, leading to cardiac structural, electrical, and autonomic remodeling [66].

Arrhythmia-free survival after catheter ablation is known to be significantly lower among patients with DM, with risk associated particularly with poor glycemic control [67, 68]. However, a review of a large cohort from the German Ablation Registry demonstrated no increased atrial arrhythmia recurrence associated with DM [69]. A meta-analysis of 15 studies, including 1464 patients, also showed AF ablation safety and efficacy similar to the general population, particularly in a younger cohort with reasonable glycemic control. However, a higher frequency of redo-ablations in DM patients was required to achieve a similar efficacy [70]. One meta-regression analysis in this study demonstrated a higher baseline glycated haemoglobin (HbA1c), along with advanced age and higher body mass index (BMI), related to a higher incidence of arrhythmia recurrence.

Reinforcing the benefits of good glycemic control in DM patients due to undergoing AF ablation, a retrospective study of nearly 300 patients [71] demonstrated both avoidance of DM and increased glycemic control pre-ablation reduced arrhythmia recurrence post-ablation; HbA1c levels of

Recent studies have investigated the potential specific impact of sodium–glucose co-transporter-2 inhibitors (SGLTis) on AF recurrence following catheter ablation in patients with DM [72, 73]. A retrospective analysis has demonstrated that SGLTi use is associated with a significantly reduced risk of arrhythmia recurrence after AF ablation, thereby decreasing the requirement of subsequent interventions: cardioversion, AAD, or repeat ablation [72]. Similarly, a prospective study and a meta-analysis showed that SGLTi therapy correlates with improved maintenance of sinus rhythm post-ablation in DM patients [73]. These observed benefits are suggested to be attributable to the effects of SGLTis on weight reduction, blood pressure control, intravascular volume management, and mitigation of atrial fibrosis and adverse cardiac remodeling [72]. These findings highlight the potential role of SGLTis in enhancing outcomes following catheter ablation in patients with DM. However, further large-scale, prospective studies are needed to confirm these results and clarify the proposed underlying mechanisms.

HF and AF often co-exist, frequently complicating one another [74, 75]. HF is a key determinant for the prognosis of AF patients, including the recurrence and progression of arrhythmia. The Framingham cohort demonstrated that more than half of those with new HF had associated AF, and 37% of those with new AF diagnoses had HF [75]. The risk of new AF in HF can be attributed to multiple mechanisms related to neurohormonal, structural, and ultrastructural changes, including atrial pressure overload and enlargement, altered myocardial conduction, maladaptive gene expression, and cardiac remodeling [74].

Owing to the co-existence of the two conditions and the rise in options for medical therapy for HF, multiple studies containing large proportions of participants with AF have demonstrated mortality benefits, reduced hospitalization, and reduced urgent HF visits [76, 77, 78, 79, 80]. A recent meta-analysis [81] showed that SGLTis might only reduce HF hospitalization and CV death to a similar degree in those with or without AF but went on to build an association between SGLTis with reduced total and serious AF event rates. Our recent review postulated that SGLTis may have anti-arrhythmic effects via action on cardiac autonomic function [82].

Multiple randomized trials have demonstrated the potential of AF ablation to improve clinical outcomes in patients with AF and symptomatic heart failure with reduced ejection fraction. The PABA-CHF trial [83] showed that PVI was superior to atrioventricular node ablation and biventricular pacing in improving functional capacity, quality of life, and left ventricular ejection fraction (LVEF). Similarly, the ARC-HF trial [84] found that catheter ablation led to significant improvements in exercise capacity, quality of life, and the neurohormonal states of patients compared to a pharmacological rate control strategy. Further reinforcing this notion, the AATAC trial [85] found that catheter ablation resulted in higher rates of freedom from AF, reduced mortality, fewer hospitalizations, and improvements in LVEF and exercise capacity compared to amiodarone therapy. Marrouche et al. [86] also demonstrated catheter AF ablation in HF patients intolerant or unwilling to take AADs was associated with a significantly lower rate of a composite endpoint of death from any cause or hospitalization for worsening HF when compared to medical therapy (rate or rhythm control). In a recent study, randomizing patients with AF and end-stage HF, the combination of catheter ablation and guideline-directed medical therapy was associated with a lower likelihood of a composite of death from any cause, implantation of a left ventricular assist device, or requirement for urgent heart transplantation, compared with medical therapy alone [87]. Together, these studies position catheter ablation as a potentially valuable therapeutic strategy in this patient population.

Given this evidence, optimal management of HF may benefit from increasing arrhythmia-free survival after rhythm control by modifying and reversing substrates for AF. There is, however, limited evidence for specific interventions. The RACE 3 trial [88], which combined best medical therapy with cardiac rehabilitation for patients with mild-to-moderate HF and persistent AF, increased maintenance of sinus rhythm after cardioversion at 12 months, but the results were no longer present at the 5-year follow-up.

In recent years, obstructive sleep apnea (OSA) has been increasingly recognized as an important risk factor for AF. OSA is characterized by apneic episodes resulting from pharyngeal collapse [7]. Meanwhile, increased vagal activation from repetitive transient hypoxemia has been proposed as a factor that may affect the atrial effective refractory period (ERP) and thereby increase susceptibility to the development of AF [89]. Furthermore, hemodynamic changes from long-standing OSA can cause an increase in LA pressure, leading to LA dilatation, which can lead to the development of AF [90]. Chronic OSA demonstrated in rat models induced cardiac remodeling, which is known to promote AF with conduction abnormalities related to connexin dysregulation and is associated with increased inflammatory and prothrombotic states and myocardial fibrosis [91].

Growing evidence suggests that outcomes post-AF ablation are poorer in patients with OSA, with meta-analytical data showing up to 70% higher risk of AF recurrence post-catheter ablation in this cohort [92]. In a study of 62 patients with OSA undergoing PVI for symptomatic AF, arrhythmia-free survival was better in those receiving continuous positive airway pressure (CPAP) than non-users [93], with other observational studies demonstrating similar results [94, 95]. We are currently undertaking the OSCA trial [96], which is a two-center nested cohort study using a Reveal LINQ II (Medtronic, Minneapolis, MN, USA) implantable loop recorder (ILR) to identify precise arrhythmia (atrial/ventricular) incidence in patients with moderate–severe OSA. We recruited 200 randomized patients 1:1 to standard care alone or standard care + ILR (+ Holter monitor at baseline and 12 months). The primary objective was to compare arrhythmia detection over 3 years between the two groups. Cardiac autonomic function was assessed in the ILR arm at baseline and 12 months post-CPAP. The secondary objectives explored the mechanisms linking OSA and arrhythmia using cardiac autonomic function parameters based on Holter recordings and circulating biomarkers (high sensitivity Troponin-T, N-terminal pro-B-type natriuretic peptide, matrix metalloproteinase-9, fibroblast growth factor 23, high sensitivity C-reactive protein, interleukin-6 and tumor necrosis factor-

The relationship between obesity and AF is well established, with increasing evidence linking obesity as an independent risk factor for AF [97]. Results from the ARIC study [98] have shown that being overweight and obese BMI

The distribution of body weight also appears to be significant. In a registry study involving patients with a BMI between 18.5 and 23 kg/m2, those with a waist circumference exceeding 80 cm in females and 90 cm in males had a higher risk of developing AF [107]. A prospective cohort database of 44,135 employees from a coal mining company identified similar waist circumference thresholds as independent predictors of AF incidence, even after adjusting for BMI [108]. These findings may explain why some studies have reported a linear relationship between BMI and AF risk, while others have observed a ‘j-shaped’ association.

Weight reduction has positively impacted cardiac structure, reduced AF events on ambulatory recording, and reduced AF symptom burden. The LEGACY-AF study [109] demonstrated long-term sustained weight loss, particularly with avoidance of weight fluctuation, was associated with a dose-dependent reduction in AF burden and maintenance of sinus rhythm. It is believed the benefit was derived from the coinciding favorable changes in cardiometabolic risk factor profile, inflammatory state, and improved cardiac remodeling. The ARREST-AF study [110] demonstrated increased post-ablation AF-free periods and greater weight loss with aggressive risk factor modification to address obesity. Studies on the effects of bariatric surgery on the outcomes of AF ablation, including a retrospective analysis of 239 patients with BMIs

Observational studies have shown inconsistent results regarding the association between lower cholesterol and AF risk, with some demonstrating a paradoxical lower risk with higher low density lipoprotein (LDL) levels [115, 116]. The relationship is likely consequential, with a deranged lipid profile increasing the risk of adverse CV events, providing a source to AF substrate [117]. Nonetheless, the exact mechanisms remain unclear, and until further evidence suggests otherwise, hyperlipidemia, at the least, should be managed as part of the overall CV risk [115].

Those who live more sedentary lives are at higher risk of AF due to the associated risk of poorer CV health and the accumulation of other co-morbidities, including a higher risk of obesity, high BP, and DM [118]. Lack of physical activity further augments cardiomyopathy, exacerbating the AF substrate. Conversely, moderate regular activity can offset some of the AF risk associated with obesity and attenuate the increased risk of AF with LA enlargement [119]. Cardiorespiratory fitness has been demonstrated to predict arrhythmia recurrence in obese individuals with symptomatic AF, and an improvement in cardiorespiratory fitness augments the beneficial effects of weight loss [120]. Moderate amounts of activity significantly reduce AF risk [121]. There is a reduced risk of AF with moderate-intensity physical activity versus no exercise, which is not seen in low- or high-intensity exercise [122]. A balanced activity approach with a ‘u-shaped’ dose response to exercise is important. Supervised exercise is safe and beneficial to patients with AF. Even short, tailored physical activity programs have proven to reduce AF recurrence, improve LA and ventricular function parameters, improve quality of life, and increase cardiorespiratory fitness in participants with AF [123, 124, 125, 126, 127]. Physical activity as part of a cardiac rehabilitation model after AF ablation, as shown in the CopenHeartRFA trial [128], showed the impact of 12 weeks of physical exercise sessions with four psycho-educational consultations. Cardiorespiratory fitness, measured by VO2 max, increased and was maintained at the 12-month follow-up, and a lower proportion of patients had high anxiety at the 24-month follow-up.

The causal relationship between alcohol consumption and AF is well established, demonstrating a dose-dependent relationship [129] and a more prominent link with acute heavy drinking [130]. Two meta-analyses have further consolidated the linear dose-response relationship between alcohol intake and AF incidence [131, 132]. The Framingham study showed a significant 8% increase in the relative risk in the incidence of AF for each standard drink per day, compared to no alcohol at all [133]. A recent study also found that abstinence from alcohol significantly reduced arrhythmia recurrences at the 6-month follow-up in regular drinkers with AF (both paroxysmal and persistent) who were in sinus rhythm at baseline [134]. Alcohol has been shown to affect the autonomic nervous system, shorten the atrial ERP, and be associated with LA enlargement, all of which contribute to the pathophysiology of AF, as mentioned previously [135, 136]. Studies have also clearly demonstrated the link between alcohol and AF recurrence post-catheter ablation. In a 2016 Japanese study of 1361 patients with paroxysmal AF undergoing their first catheter ablation, AF recurrence post-intervention was noted to be higher in those who consumed alcohol compared to those who were abstinent [137]. In a Chinese cohort of 122 patients undergoing PVI for paroxysmal AF, LA voltage mapping reportedly showed a greater degree of low-voltage zones in those who consumed moderate to high amounts of alcohol, with the procedural success rate being 69.2% and 35.1%, respectively, compared to a success rate of 81.3% in those who abstained from alcohol consumption [138]. In light of the evidence, international guidelines [7, 10] recommend minimizing alcohol consumption, ideally achieving complete abstinence, in individuals with AF, with a stronger emphasis on those pursuing rhythm-control strategies.

Numerous prospective cohort studies have previously tried to explore the link between smoking and the increased risk of AF; however, reported results have varied. Results reported from the ARIC study showed that current smoking accounted for about a 10% increase in the incidence of AF [139]. In contrast, other authors have documented an increase in risk of up to 32% in current smokers, with some authors even presenting double this figure [139, 140]. Oxidative stress, an increase in sympathetic tone, and fibrotic changes to the atrial wall have been implicated in the pathological effects of smoking in the development of AF. In a study involving 59 patients with refractory AF undergoing PVI, the diameter of the pulmonary veins and the LA volumes was larger in smokers with an AF recurrence rate of 43% post-ablation, compared to 14% in non-smokers [141]. Though conclusive evidence regarding smoking and AF prevention (post-AF ablation) is lacking at present, smoking cessation is strongly recommended in general, especially in patients with CV disease.

Studies have investigated the relationship between caffeine or coffee consumption and AF risk, collectively challenging previous concerns about the arrhythmogenic potential of caffeine [142]. Cheng et al. [143] conducted a dose-response meta-analysis of prospective cohort studies and found that each 300 mg/day increase in habitual caffeine intake was associated with a 6% lower risk of AF, suggesting a potential protective effect. Similarly, Krittanawong et al. [144], in a systematic review and meta-analysis, concluded that caffeine or coffee consumption does not increase the risk of new-onset AF and may even offer modest protective benefits. Bodar et al. [145], in the Physicians’ Health Study, observed no significant association between coffee consumption and AF incidence in a large cohort of male physicians, with no evidence of a dose-response relationship. Together, these findings reassure that moderate caffeine consumption is not associated with an increased risk of AF and may confer a protective effect, supporting a more nuanced understanding of the impact of caffeine on cardiovascular health.

While addressing individual risk factors is beneficial, a holistic approach to management has demonstrated superior outcomes. The best demonstration of this was in the ARREST-AF study [110]. Here, a total of 149 consecutive patients undergoing AF ablation with BMI

Our CREED-AF study is recruiting and represents a randomized controlled trial designed to evaluate the effectiveness of cardiac prehabilitation, rehabilitation, and patient education on AF risk factors in those undergoing first-time AF ablation [146]. The study aims to determine if these simple interventions can improve cardiorespiratory fitness and explore the impact on clinical factors related to AF ablation, including health-related quality-of-life, AF recurrence and burden, and the requirement for repeat AF ablation; the study defined major adverse cardiovascular events and cost-effectiveness of such an intervention. Furthermore, the study introduces a novel approach by incorporating comprehensive risk factor management in the form of planned prehabilitation (a program of education, risk factor assessment, and exercise pre-procedure), in addition to rehabilitation, into a randomized controlled trial, providing a rigorous evaluation of its potential benefits for patients undergoing AF ablation.

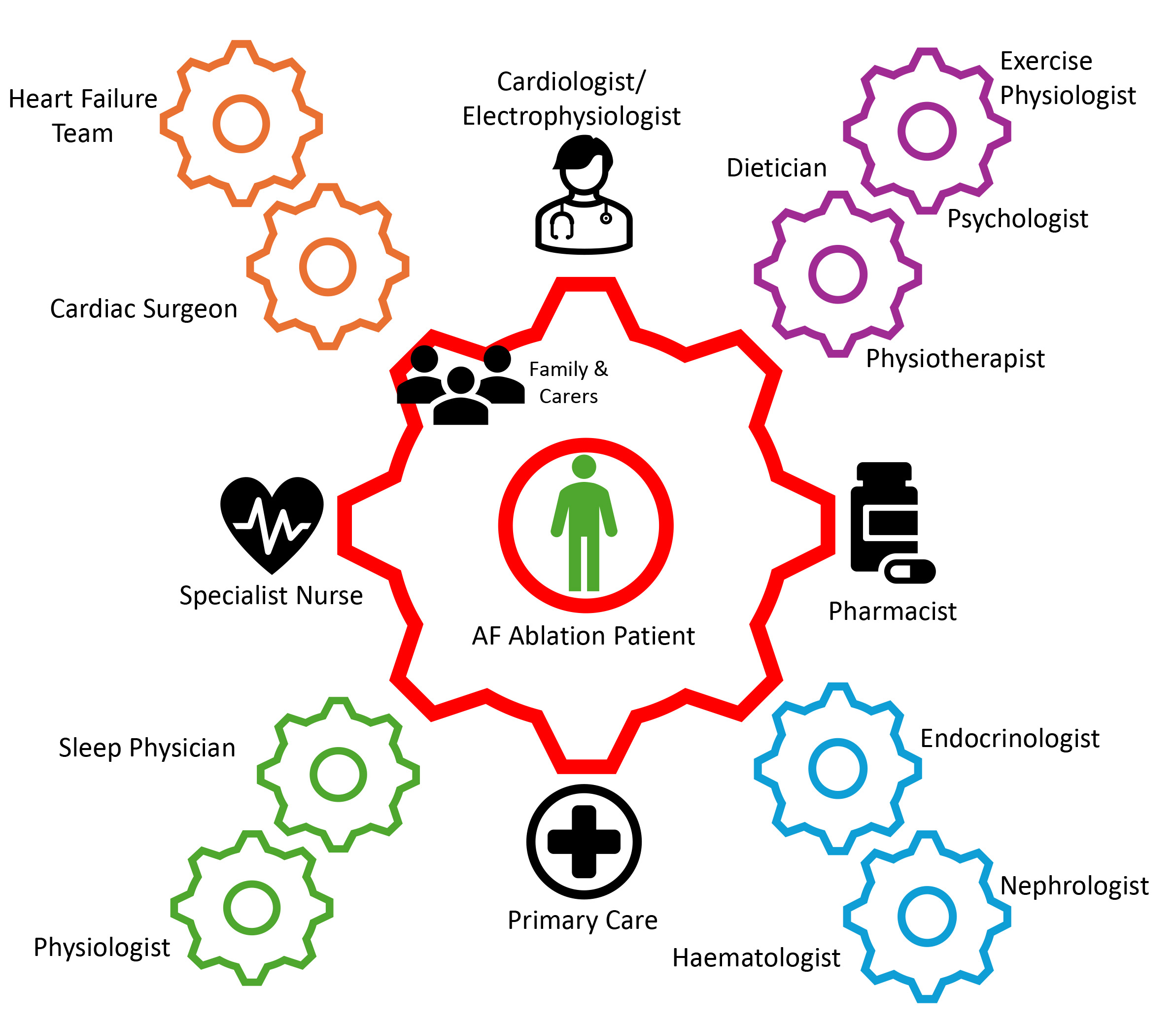

Increasing evidence supports a holistic/integrated AF care approach to each patient, working with them to tackle co-morbidities [7]. Meanwhile, international guidelines call for employing a multidisciplinary-based approach [7, 10]. Though this approach may be resource-intensive, it is preferred over opportunistic methods. Indeed, a ’hub-and-spoke’ model could be suggested, with a central coordinating team including the cardiologists, general practitioners, specialist nurses, and pharmacists, and further involving other healthcare professionals depending on local funding and targeted therapy (see Fig. 3). Multiple models, including multi-disciplinary teams, nurse-led clinics, or cardiologist-led, have been employed and published with mixed results [147, 148, 149, 150]. Hendriks et al. [147] demonstrated better outcomes of CV hospitalizations and CV mortality in AF patients with a nurse-led care group compared to usual care. However, the recent RACE 4 trial [148] failed to show the superiority of a nurse-led over usual care approaches but suggested that nurse-led care by an experienced team could be clinically beneficial. Thus, more evidence on these strategies is required [7].

Fig. 3.

Fig. 3. Demonstration of the multi-disciplinary team ‘hub-and-spoke’ approach to the management of patients undergoing an AF ablation procedure. AF, atrial fibrillation.

Effective risk factor management is crucial in treating AF, especially in those undergoing AF ablation, regardless of the approach. A comprehensive approach to managing risk factors, including hypertension, obesity, DM, OSA, HF, and lifestyle choices, such as smoking and excessive alcohol consumption, can significantly reduce AF recurrence and improve long-term prognosis. A summary of the pertinent studies explored in our review is represented in Table 1 (Ref. [59, 60, 61, 71, 72, 73, 93, 94, 95, 110, 111, 112, 113, 128]). Importantly, with AF predicted to become an increasing load on healthcare systems worldwide, any attempts to curtail and enhance the current epidemic will ease and potentially reverse this growing burden. The broad adoption and assessment of risk factor management are essential in this endeavor.

| Study | Population | Risk factor modification/intervention | Outcomes |

| Hypertension | |||

| Parkash et al., 2017 (SMAC-AF) [59] | AF patients (57% paroxysmal) | Aggressive BP treatment (target | At 12 months: recurrence of AF/atrial tachycardia/atrial flutter not different to control group (p = 0.763) |

| Pokushalov et al., 2012 [60] | AF patients refractory to 2 AAD with drug-resistant hypertension | Renal denervation in addition to PVI vs. PVI alone | At 12 months: intervention group: 69% arrhythmia-free; control group: 29% arrhythmia-free (p = 0.033) |

| Steinberg et al., 2020 (ERADICATE-AF) [61] | Paroxysmal AF patients | Renal denervation in addition to PVI vs. PVI alone | At 12 months: intervention group: 72% freedom from AF recurrence; control group: 57% freedom from AF recurrence (p = 0.006) |

| Diabetes mellitus | |||

| Donnellan et al., 2019 [71] | AF patients with diabetes (40% paroxysmal) | Pre-procedure HbA1c control | At 26 months: HbA1c control ( |

| Abu-Qaoud et al., 2023 [72] | AF patients with diabetes | Baseline SGLTi use vs. no baseline SGLTi use | SGLTi use: 27.8% event rate; no SGLTi use: 36% event rate (p |

| Zhao et al., 2023 [73] | AF patients with diabetes | Baseline SGLTi use vs. no baseline SGLTi use | At 18 months: SGLTi use: 26.8% AF recurrence; no SGLTi use: 39.3% AF recurrence (p |

| Obstructive sleep apnea | |||

| Fein et al., 2013 [93] | AF patients (53% persistent AF) | Treatment of OSA vs. non-treatment | At 12 months: with CPAP: 72% arrhythmia-free survival; without CPAP: 37% arrhythmia-free survival (p = 0.01) |

| Patel et al., 2010 [94] | AF patients (53% paroxysmal AF) | Treatment of OSA vs. non-treatment | At 32 months: with CPAP: 79% arrhythmia-free survival; without CPAP: 68% arrhythmia-free survival (p = 0.001) |

| Naruse et al., 2013 [95] | AF patients (54% paroxysmal AF) | Treatment of OSA vs. non-treatment | At 19 months: with CPAP: 30% AF recurrence; without CPAP: 53% AF recurrence (p |

| Obesity | |||

| Donnellan et al., 2019 [111] | AF patients, BMI 41 (39% paroxysmal AF) | Bariatric surgery vs. no bariatric surgery | At 36 months: bariatric surgery group: 20% AF recurrence; no bariatric surgery group: 61% AF recurrence (p |

| Donnellan et al., 2019 [112] | AF patients, BMI 35 (41% paroxysmal AF) | Bariatric surgery vs. no bariatric surgery vs. non-obese | At 6 months: Group 1: 57% freedom from AF, Group 2: 85% freedom from AF (Fisher’s Test: p = 0.085; OLR: p = 0.046) (p |

| Goldberger et al., 2023 (LEAF Study) [113] | AF patients, BMI 36 (20% paroxysmal AF) | RFM + Liraglutide or RFM alone | At 6 months: Group 1: 57% freedom from AF, Group 2: 85% freedom from AF (Fisher’s Test: p = 0.085; OLR: p = 0.046) At 12 months: RFM + Liraglutide: 83% freedom from AF; RFM alone: 57% freedom from AF. Group 1 ( |

| Exercise/cardiac rehabilitation | |||

| Risom et al., 2020 (CopenHeartRFA) [128] | AF patients (72% paroxysmal) | 12 weeks of cardiac rehabilitation vs. usual care | VO2 max increased in the cardiac rehabilitation group vs. controls, but no significant difference in mental health or other SF-36 components at 4- and 12-month follow-ups |

| Comprehensive risk factor management | |||

| Pathak et al., 2014 (ARREST-AF) [110] | AF patients, BMI | Aggressive comprehensive RFM vs. usual care | At 41 months: RFM group: reduced AF-symptom burden (p |

AAD, anti-arrhythmic drugs; AF, atrial fibrillation; BP, blood pressure; CPAP, continuous positive airway pressure; HbA1c, glycated haemoglobin; OLR, ordinal logistic regression; OSA, obstructive sleep apnea; PVI, pulmonary vein isolation; RFM, risk factor management or risk factor modification; SF-36, 36-item short form survey; SGLTi, sodium glucose co-transporter 2 inhibitor; BMI, body mass index.

NC, VA, TH, VGL, TL, HE, GM, and FO helped with the design of the review. NC and VA wrote the initial draft and GM, FO provided help, advice and supervision. All authors contributed to writing, reviewing and editing the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript. All authors have participated sufficiently in the work and agreed to be accountable for all aspects of the work.

Not applicable.

We would like to thank the UHCW R&D Department for their support.

NC was supported with a fellowship from Boston Scientific. VA was supported with a fellowship from Medtronic Ltd.

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

Publisher’s Note: IMR Press stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.