1 Institute of General Pathology and Pathophysiology, 125315 Moscow, Russia

2 Institute on Aging Research, Russian Gerontology Clinical Research Centre, Pirogov Russian National Research Medical University, 129226 Moscow, Russia

3 Department of Polyclinic Therapy, NN Burdenko Voronezh State Medical University, 394036 Voronezh, Russia

4 Institute for Atherosclerosis Research, 121609 Moscow, Russia

5 Laboratory for Cardiac Fibrosis, Research Institute for Complex Issues of Cardiovascular Diseases, 650002 Kemerovo, Russia

6 Institute of Experimental Cardiology, Russian Medical Research Center of Cardiology, 121552 Moscow, Russia

Abstract

Cardiovascular diseases continue to be the primary cause of mortality in industrialised countries, and atherosclerosis plays a role in their development. A persistent inflammatory condition affecting big and medium-sized arteries is known as atherosclerosis. It is brought on by dyslipidemia and is facilitated by the immune system’s innate and adaptive components. At every stage of the progression of atherosclerosis, inflammation plays a crucial role. It has been demonstrated that soluble factors, or cytokines, activate cells involved in the pathophysiology of atherosclerosis and have a significant impact on disease progression. Anti-inflammatory cytokines (such as interleukin (IL)-5 and IL-13) mitigate atherosclerosis, whereas pro-inflammatory cytokines (such as IL-1, IL-6) quicken the disease’s course. Of interest is the fact that a number of cytokines can exhibit both atherogenic and atheroprotective properties, which is the topic of study and discussion in this review. This review provides a comparative analysis of the functions of the main cytokines involved in the pathogenesis of atherosclerosis. Their functional relationships with each other are also shown. In addition, potential therapeutic strategies targeting these cytokines for the treatment of atherosclerosis are proposed, with an emphasis on recent clinical research in this area.

Keywords

- atherosclerosis

- cytokines

- cytokine-targeted therapy

- cytokines in atherosclerosis

Atherosclerosis is a chronic inflammatory disease of the arteries that accounts for about 50% of all deaths in Western society. It is primarily a lipid process initiated by the accumulation of low-density lipoproteins and residual lipoprotein particles, as well as an active inflammatory process in focal areas of the arteries, especially in areas of impaired nonlaminar flow at arterial branch points. It is considered a major cause of the occurrence of atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease (ASCVD) leading to heart attacks, strokes and peripheral artery disease [1].

Because atherosclerosis is a predominantly asymptomatic condition, it is difficult to accurately determine the incidence. Atherosclerosis is considered the main cause of cardiovascular disease. Atherosclerotic cardiovascular diseases mainly affect the heart and brain: coronary heart disease (CHD) and ischemic stroke. Ischemic heart disease (IHD) and stroke are the first and fifth causes of death in the world, respectively [2].

Studies in humans and animals have established that atherosclerosis is caused by a chronic inflammatory process in the arterial wall, initiated primarily in response to endogenously altered structures, in particular oxidized lipoproteins, which stimulate both innate and adaptive immune responses [3]. The innate response is initiated by the activation of both vascular cells and monocytes/macrophages. Subsequently, the adaptive immune response develops against a variety of potential antigens presented to effector T lymphocytes by antigen-presenting cells. Vascular cells, endothelial cells and smooth muscle cells (SMCs) are involved in disease progression by providing feedback to maintain inflammation through the release of pro-inflammatory cytokines and chemokines. Cytokines play a dual role in atherosclerosis. Pro-inflammatory cytokines promote disease development and progression, whereas anti-inflammatory and T-cell-associated regulatory cytokines exert distinct antiatherogenic activity [4].

There is currently a growing interest in a new therapeutic area, namely agents directed against specific targets in the inflammatory cascade. New strategies are developing in the battle against atherosclerosis, and several of them show promise as our understanding of the function of cytokines in atherogenesis grows. The first objective of this review is to compare the functions of different types of cytokines in the pathogenesis of atherosclerosis, using interleukin (IL)-6 as an example, show in detail the ability of some cytokines to exhibit both atherogenic and atheroprotective properties. The second objective of this review is to select the most promising cytokines as therapeutic targets and to analyze existing preclinical and clinical studies using them.

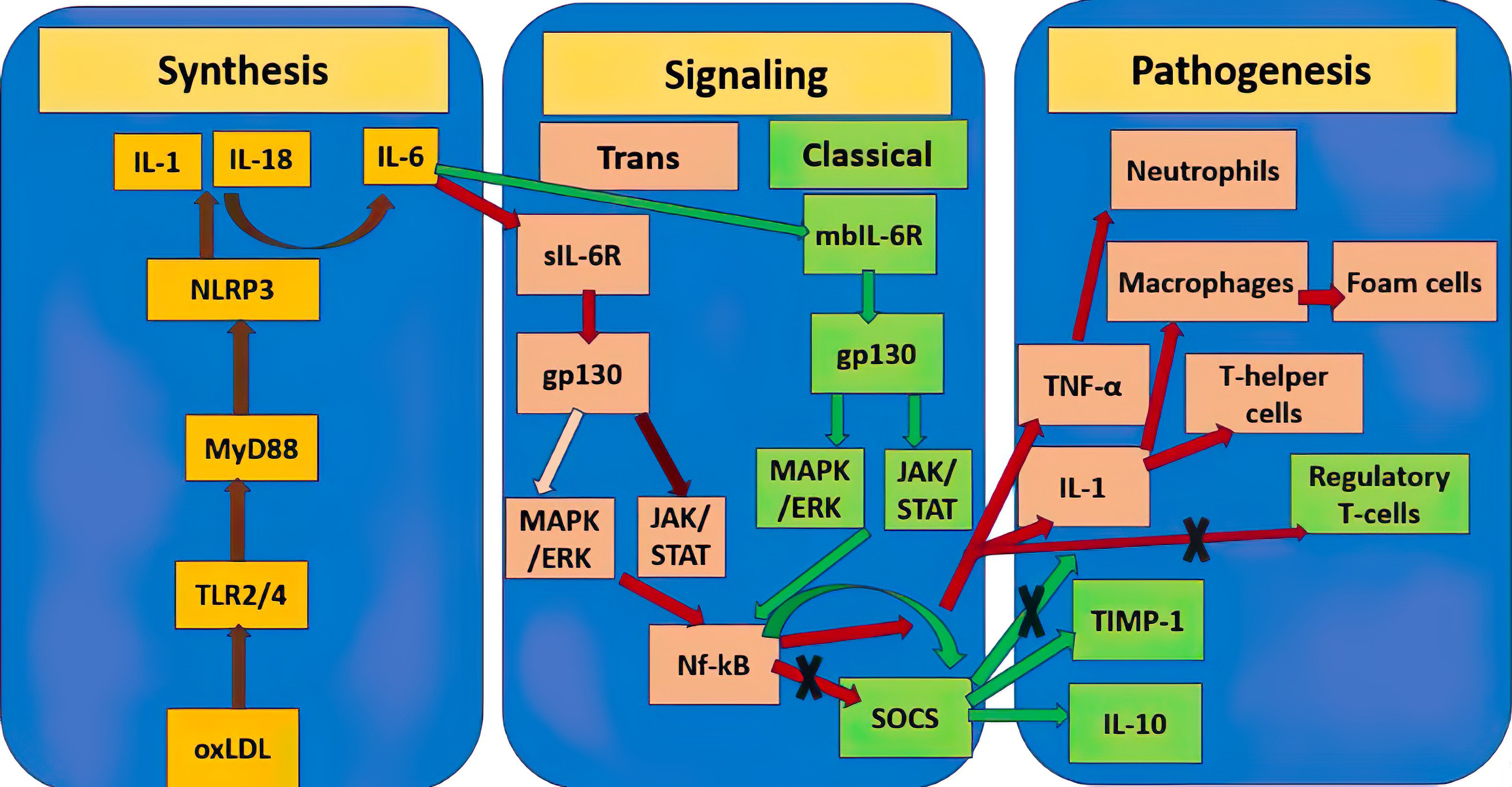

IL-6 is a significant cytokine implicated in several cardiac conditions. IL-6 possesses pro-inflammatory characteristics and can also exhibit anti-inflammatory features. IL-6 is generated by fibroblasts, endothelial cells, macrophages, monocytes, and vascular smooth muscle cells (VSMCs) in cardiovascular disorders [5]. Oxidized low density lipoproteins (oxLDL) which are formed in atherosclerosis initiate toll-like receptors (TLR especially TLR2/4) activation. It causes activation of the NOD-like receptor protein 3 (NLRP3) inflammasome and further maturation of IL-1 and IL-18 cytokines which stimulate myeloid cells to release IL-6 in addition to tumor necrosis factor alpha (TNF-

To initiate the conventional signaling cascade, IL-6 attaches to the membrane-bound (mb) IL-6 receptor (IL-6R) (mbIL-6R), which is found on some types of leukocytes. Intracellular signaling pathways, such as the Janus kinase/signal transducer and activator of transcription (JAK/STAT) pathway, are dimerized and activated by the IL-6/IL-6R complex [5]. Since soluble IL-6R (sIL-6R) enables IL-6 to stimulate cells lacking IL-6R on their membranes, it is crucial for trans-signaling. While trans-activation is linked to pro-inflammatory effects, classic IL-6 signaling is thought to have anti-inflammatory qualities [7]. The process of IL-6 signaling begins with the binding of the IL-6/IL-6R complex to the gp 130 protein. The newly formed complex activates two signaling pathways: JAK/STAT and mitogen-activated protein kinase (MAPK)/ERK (extracellular signal-regulated kinase) [8]. In the classical version, both pathways are activated uniformly and the subsequent evoked activation of inflammatory cytokine transcription is inhibited by the regulatory protein suppressor of cytokine signaling (SOCS) [8]. As a result of trans-signaling, there is a preferential activation of JAK/STAT and inhibition of signal transmission to SOCS, which contributes to the development of chronic inflammation [8].

Suppression of T cell death, inflammatory cell recruitment, and inhibition of regulatory T cell differentiation are among the pro-inflammatory activities of IL-6. One of the key molecular participants in acute phase reactions is IL-6, and there is a correlation between IL-6 and C-reactive protein (CRP) levels. Because of this, clinical practice uses both IL-6 and CRP as inflammatory indicators [9]. The anti-inflammatory effects of IL-6 in atherosclerosis include inhibition of the expression of pro-inflammatory cytokines: IL-1 and TNF-

One of the earliest expressed pro-inflammatory cytokines related to heart disease is TNF-

In addition to TNF-

IL-1

IFN-

In addition to the cytokines described above, which activate the effector functions of leukocytes, cytokines that affect the development and reproduction of cells involved in the pathogenesis are of great importance in the pathogenesis of atherosclerosis. Such cytokines include G-CSF and GM-CSF.

Human cardiomyocytes, monocytes, fibroblasts, and endothelial cells are the primary producers of G-CSF [11]. Its base function in the pathophysiology of the heart is to promote the growth and differentiation of neutrophils from monocytes. Moreover, G-CSF is found to protect vascular endothelial cells and cardiomyocytes from apoptosis [18].

T cells are the main producers of GM-CSF, although fibroblasts, endothelium and epithelial cells, and epithelial cells can also release it [11]. This cytokine promotes the survival, development, and propagation of neutrophils, eosinophils, macrophages, dendritic cells, and mast cells, among other functions that contribute to the initiation of inflammation [19].

IL-2, like IL-6, despite its predominant pro-inflammatory functions, can exhibit a dual role in the pathogenesis of atherosclerosis. It has been demonstrated from experimental data that IL-2 has been associated with heart disease, despite not having received as much research as some other cytokines. It is well recognized that IL-2 plays a crucial role in the growth and survival of T regulatory cells, which are necessary for tolerance and immune response suppression [20]. But because it is critical for promoting effector T cell development and proliferation, IL-2 has a dual function in inflammation. Although it has mostly been employed in cancer clinical settings, it has been shown to have cardiotoxic effects, particularly at high dosages [21].

Recently, scientists have started to comprehend the function of IL-17 in the pathophysiology of human disease. In comparison to other described cytokines, such as: IL-6, IL-1, IL-18, IFN-

Research using mice indicates that IL-5 and IL-13 may have an antiatherogenic effect [1]. It has been demonstrated that IL-5 increases the generation of neutralizing antibodies (IgM) to oxLDL, which in turn helps to shrink atherosclerotic plaques [24]. Research on the function of IL-13 in atherosclerosis has shown that recombinant IL-13 treatment stabilizes plaque by lowering macrophage accumulation, decreasing vascular adhesion molecule-1 (VCAM-1)-dependent monocyte enrollment, and raising collagen content [25]. Crucially, in LDLr -/- mice, IL-13 deficiency sped up the onset of atherosclerosis without changing blood cholesterol levels. As a result, IL-13 positively modifies plaque architecture and has preventive qualities against atherosclerosis [25].

Other cytokines that perform significant atheroprotective functions in addition to IL-5 and IL-13 are IL-27 and IL-35. A heterodimer made up of the subunits p28 and Ebi3, IL-27. The cytokines IL-27 and IL-35 have the same Ebi3 subunit [24]. With a wide range of effects on many cell types, IL-27 is considered as an anti-inflammatory cytokine [26]. Since IL-27 receptor-deficient animals show greater Th1 and Th17 CD4+ T cell activation and accumulation in the aorta as well as an increase in IL-17A and IL-17A-regulated chemokines (e.g., monocyte chemoattractant protein-1 (MCP-1)), IL-27 inhibits CD4+ T cell activation. This leads to an accumulation of different kinds of myeloid cells. Additionally, IL-27 suppresses the production of foam cells by preventing macrophages from accumulating lipids [27].

This heterodimer consists of the IL-35 subunits p35 and Ebi3. This anti-inflammatory cytokine originates from T-regulatory cells [24]. In addition to controlling the expression of anti-inflammatory cytokines, IL-35 limits the activation of CD4+ T-cells, promotes the development of T-regulatory cells, and delays the progression of inflammatory and autoimmune illnesses. The Ebi3 and p35 subunits have been identified as being present in the atherosclerotic aorta, and in mouse models predisposed to atherosclerosis, the loss of the Ebi3 subunit gene aggravates the disease [24]. According to study [28] IL-35 inhibits the MAPK signaling cascade, which in turn prevents endothelial cells from producing VCAM-1. This prevents acute inflammation in the vascular wall caused by lipopolysaccharide [28].

Like IL-27 and IL-35, IL-10 signaling affects various immune cell types involved in the pathogenesis of atherosclerosis. The production of IL-10 by lymphocytes and macrophages (M2) is crucial for the regulation of both innate and adaptive immunity. The generation of IL-10 in lymphocytes is linked to a fraction of Th2, T regulatory cells, and, more recently, certain Th1 cells that produce IFN-

IL-19 is one of the most significant anti-inflammatory cytokines contributing to plaque healing. The IL-20R1 and IL-20R2 subunits together form a receptor complex via which IL-19 functions [31]. Monocytes, endothelial cells, fibroblasts, and CD8+ T cells are the main producers of IL-19. The function of SMCs, the formation of Th2-dependent immune responses, and the reduction of intimal hyperplasia during vascular wall inflammation are all regulated by IL-19 [31]. The activation of VSMCs and the generation of pro-inflammatory molecules including TNF-

TGF-

The paragraph above makes clear that, depending on a variety of parameters, including the kind of activation signal and the terms of the microenvironment, the same cytokines can have both pro- and anti-inflammatory characteristics. This is clear shown in Fig. 1 by example of IL-6. The significance of various cytokines in atherosclerosis is summarized in Table 1.

| Cytokine | Inflammatory/atherogenic role in atherosclerosis | Anti-inflammatory/atheroprotective role in atherosclerosis |

| IL-6 | ||

| TNF- | - | |

| IL-1 | - | |

| IL-37/IL-38 | - | |

| IFN- | - | |

| TGF- | ||

| IL-5 | ||

| IL-13 | ||

| IL-27/IL-35 | ||

| IL-10 | - | |

| IL-19 | ||

Abbreviations: IL, interleukin; TNF-

Fig. 1.

Fig. 1. Double role of IL-6 in the pathogenesis of atherosclerosis. Yellow rectangles show mediators of the molecular pathway of initiation of atherosclerosis synthesis, the stages between them are connected by brown lines. Pink rectangles designate the atherogenic pro-inflammatory pathway triggered by IL-6, further stages are connected by red lines, the dark burgundy line designate a stronger signaling pathway relative to the weaker pale pink one. Green rectangles designate the atheroprotective anti-inflammatory pathway triggered by IL-6, further stages are connected by green lines. Crosses designate inhibition of this molecular pathway. TNF-

The subject of atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease has greatly benefited from recent studies [36, 37]. A significant phase 3 clinical study has shown for the first time that patients with stable atherosclerosis can benefit clinically from therapeutic targeting of the inflammatory response [38]. The goal of the investigation was to assess the impact of canakinumab, a monoclonal antibody that targets IL-1

As an IL-1 receptor antagonist, anakinra inhibits both the effect of IL-1

In conclusion, it seems that there is more distinction to the link between IL-1 targeting and clinical results than first believed. Medications designed to target IL-1

Currently, anti-TNF monoclonal antibodies (adalimumab, infliximab, golimumab, and certolizumab pegol) and soluble TNF receptor (etanercept) are the five anti-TNF medications authorized for clinical usage. These are accepted for the treatment of psoriatic arthritis, ulcerative colitis, rheumatoid arthritis, and ankylosing spondylitis, golimumab is a completely humanized anti-TNF monoclonal antibody.

Despite the lack of information on the therapeutic effectiveness of golimumab in atherosclerosis, positive findings from a pilot research were reported [42]. The purpose of this double-blind, randomized, placebo-controlled trial was to determine how well golimumab works in individuals with ankylosing spondylitis (AS) to slow down the development of arterial stiffness and atherosclerosis. 20 patients received monthly golimumab dosages of 50 mg, whereas 21 individuals received a placebo for a full year. Vascular measures (such as aortic stiffness and carotid intima/media thickness) did not significantly differ between the two groups after six months. On the other hand, only the placebo group showed a significant increase in mean intima media thickness (IMT) compared to the golimumab group. The augmentation index (Aix), maximum IMT, and pulse wave velocity (PWV) did not alter. After a year of therapy, there were no appreciable variations in vascular markers between the two groups.

Additional extensive research is required to thoroughly examine the possible impacts noted in this investigation. TNF inhibitors have also been shown to strengthen the overall pathological characteristics with rheumatoid arthritis (RA) and psoriasis who are at high cardiovascular risk, in addition to these findings in atherosclerosis patients. TNF targeting therapy has been beneficial in avoiding atherosclerosis in RA, and it is possible that this is also the case in psoriasis [43]. The demonstrated efficacy of TNF inhibitors for the treatment of other inflammatory diseases provides a good basis for using existing developments for testing directly on atherosclerosis models. For example, a study [44] showed that ezetimibe contributed to a decrease in serum cholesterol levels, a decrease in the concentration of inflammatory cytokines (MCP-1 and TNF-

Low-dose methotrexate (LD-MTX) treatment reduces circulating levels of CRP, IL-6, TNF-alpha, and cardiovascular events in patients with RA. An important feature of LD-MTX is its ability to increase adenosine production and stimulate the adenosine A2A receptor, which has been shown to promote the expression of several proteins involved in reverse cholesterol transport, thereby potentially reducing foam cell formation [46]. However, one should be careful when choosing doses and the mode of administration of such a systemic drug. Thus, in a clinical study [47], methotrexate, even in low doses (15 to 20 mg per week) when administered to patients with myocardial infarction and type 2 diabetes, was associated with a higher risk of developing severe side effects, including the development of non-basal cell skin cancer. In addition, it did not show effectiveness in reducing inflammation in patients with atherosclerosis—the levels of IL-1

Colchicine is a cheap anti-inflammatory medication that is prescribed to people with pericarditis, familial Mediterranean fever, and gout. Colchicine may disrupt phagocytosis, inflammasome activation, microtubule-based inflammatory cell chemotaxis, and other host immunological processes by blocking microtubule assembly. The initial benefit of colchicine on coronary artery disease (CAD) was noted in individuals who had a family history of Mediterranean fever [43]. Consequently, in order to assess the safety and effectiveness of long-term low-dose colchicine therapy in patients with acute coronary syndrome, the low dose colchicine (LoDoCo) research was created as a prospective trial. Randomization was used to assign 532 individuals receiving antithrombotic treatment and lipid-lowering medication to receive either no colchicine or a daily dosage of 0.5 mg/mL. Compared to 16% in the no-treatment group, 5.3% of patients in the low-dose colchicine group experienced the main endpoint (acute coronary syndrome, out-of-hospital cardiac arrest, or non-cardioembolic ischemic stroke) after a median follow-up of three years [48].

While there aren’t any T cell-targeted treatments being used in clinical care medicine right now to treat or prevent cardiovascular disease, a number of therapeutic strategies are being tested in clinical trials after showing promise in preclinical models. It has been demonstrated that regulatory T lymphocytes aid in the development and stagnation of atherosclerosis in mice that are susceptible to the condition [49]. On the other hand, many effector T cells—particularly the Th1 cells that secrete IFN

Therefore, the aim of T cell-targeted treatment methods in atherosclerosis is to modify the homeostatic balance of various T cell subsets by reducing populations of supposedly proatherogenic effector T cells and increasing atheroprotective, immunosuppressive T regulatory cells [51]. One approach to do this is by targeting pathways like IL-2 and boosting non-specific T regulatory cells. However, tolerogenic vaccinations against atherosclerosis-related antigens can be used to increase the number of certain T regulatory cells.

For the monoclonal antibody ziltivekimab, directed against IL-6, in 2 clinical phase 2 studies: RESCUE (in patients from the USA) [52] and RESCUE-2 [53] (in patients from Japan) demonstrated the effectiveness in reducing inflammatory and thrombotic markers of atherosclerosis in patients with chronic kidney disease, at high risk of developing atherosclerosis. According to the results of the studies, the levels of CRP in the groups of patients receiving ziltivekimab decreased in a dose-dependent manner from 77 to 96% compared with 4% (RESCUE) and 27% (RESCUE-2) in the placebo groups. There was also a significant decrease in such markers as: fibrinogen, serum amyloid A, haptoglobin, secretory phospholipase A2 and lipoprotein A. No significant side effects were observed. The success of these studies has allowed preparations to begin for a phase 3 clinical trial of ziltivekimab (ZEUS) [54] in a larger sample of patients with chronic kidney disease at high risk of developing atherosclerosis.

Given the dual nature of IL-6 in the development of atherosclerosis, it makes sense to study other IL-6 signaling mediators as targets, which determine whether the IL-6 signal will go via the classical or trans-pathway. Thus, it was shown that the IL-6R Asp358Ala variant, common in atherosclerosis, defectively binds to the leukocyte membrane, which blocks the classical transmission of the IL-6 signal [55]. Enhancement of the function of SOCS, a mediator that acts as a feedback regulator, blocking the inflammatory response of IL-6, may have great potential. Thus, the review considers the possibility of using SOCS mimetic drugs for the treatment of autoimmune diseases [56], taking into account the analysis carried out in this review, we can also assume with great confidence the potential for using these mimetics in the treatment of atherosclerosis.

The clinical studies described in this section are summarized in Table 2.

| Drug | Target | Clinical trial | Results |

| Canakinumab | IL-1 | III phase | Reduction in cardiovascular events, but development of infectious complications. |

| Anakira | IL-1 | Pilot study | No definitive reduction in inflammatory mediators. |

| Golimumab | TNF- | Pilot study | No therapeutic effect was shown. |

| Methotrexate | Dihydrofolate reductase | III phase | Severe side effects. There was no therapeutic effect in inflammatory mediators decline. |

| Colchicine | NLRP3 | Pilot study (LoDoCo) | Reduced risk of cardiovascular events |

| Ziltivekimab | IL-6 | II phase (RESCUE and RESCUE-2) | Significant decrease in biomarkers of atherosclerosis. No significant side effects were shown. |

Abbreviations: LoDoCo, low dose colchicine; TNF-

There is presently insufficient data to support the beneficial effects of targeted anti-inflammatory medication in the treatment of atherosclerosis, despite the complexity and imperfect understanding of immune and inflammatory networks. This is true even if our understanding of the underlying mechanisms of cytokine activity in humans is continually growing. Specifically, as evidenced by the MRC-ILA-HEART study [57] and more direct and indirect anti-inflammatory approaches, these therapies may in some circumstances even raise the risk of unfavorable cardiovascular events. In fact, recent research indicates that several medications showing promise in animals do not work as well in people. Agents against IL-17 and IL-12/23p40 are two examples. A recent meta-analysis shown that therapy with such medicines (bikanumab and estekinumab) may even increase the risk of significant adverse cardiovascular events when compared to placebo, despite their proatherogenic effects in animals [58]. Due to the pro-inflammatory properties of IL-17, ixekizumab, secukinumab, and brodalumab—all IL-17 receptor A antagonists can potentially block atherosclerosis. These drugs are also used to treat psoriasis. IL-17 inhibition reduces atherosclerosis in animals, although there are currently no human clinical trials available [59].

Other research, however, has demonstrated that these anti-inflammatory techniques offer important advantages. All things considered, there seems to be a big disconnect between the advantages of such focused therapies and our comprehensive understanding of cytokine activity. This might be explained by the many cytokines involved in atherogenesis and their complicated effects, as well as the shortage of large-scale clinical trials that could also offer trustworthy information on the effectiveness of these theories. Therefore, cytokine modulation poses a therapeutic conundrum, and treatment must take into account the advantages and disadvantages of reducing inflammation. Observations are mostly restricted to rheumatic patients, especially for novel biologic treatments, and data demonstrating the benefits of some settings (e.g., TNF inhibitors) for survival and health is weak in small-scale clinical studies. It is interesting to note that there are a number of these clinical studies now taking place (most notably the CANTOS, CIRT, and Entracte trials), the outcomes of which are widely anticipated and might influence the course of atherosclerosis research in the future [60, 61, 62]. In addition, a promising future direction is the development and testing of mimetics of anti-inflammatory cytokines with a wide range of functions (IL-27, IL-35, IL-19). Another important direction is the study of the mechanisms of “switching” from atherogenic to atheroprotective action for cytokines that show a dual role in atherosclerosis: IL-6, TGF-

Both pro- and anti-inflammatory cytokines play a major role in the development of atherosclerosis. Some cytokines can play both of these roles to a greater or lesser extent, for example: IL-6 and TGF-

AVB, AVC, VNS designed the research study. AVB, IAS performed the data collection. TIK, TBP and AVC analyzed the data. AVB, VNS, IAS wrote the manuscript. All authors contributed to editorial changes in the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript. All authors have participated sufficiently in the work and agreed to be accountable for all aspects of the work.

Not applicable.

Not applicable.

This research was funded by Russian Science Foundation, Grant# 22-15-00134.

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

Publisher’s Note: IMR Press stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.