1 Department of Physiology, Pomeranian Medical University, 70-111 Szczecin, Poland

Abstract

Hypertrophic cardiomyopathy (HCM) is the most prevalent hereditary cardiovascular disorder, characterised by left ventricular hypertrophy and cardiac fibrosis. Cardiac fibroblasts, transformed into myofibroblasts, play a crucial role in the development of fibrosis. However, interactions between fibroblasts, cardiomyocytes, and immune cells are considered major mechanisms driving fibrosis progression. While the disease has a strong genetic background, its pathogenetic mechanisms remain complex and not fully understood. Several signalling pathways are implicated in fibrosis development. Among these, transforming growth factor-beta and angiotensin II are frequently studied in the context of cardiac fibrosis. In this review, we summarise the most current evidence on the involvement of signalling pathways in the pathogenesis of HCM. Additionally, we discuss the potential role of monitoring pro-fibrotic molecules in predicting clinical outcomes in patients with HCM.

Keywords

- hypertrophic cardiomyopathy

- signalling pathways

- transforming growth factor-β1

- cardiac fibrosis

Hypertrophic cardiomyopathy (HCM) is the most common hereditary cardiovascular disease, characterized by left ventricular hypertrophy (LVH) and myocardial fibrosis [1]. It is estimated that HCM affects 0.2% to 0.5% of the general population [2, 3]. One recent study indicate that the prevalence may be higher than previously thought due to underdiagnosis and the variable expression of genetic mutations [4]. HCM is familial in approximately 60% of cases, with first-degree relatives of affected individuals having a 50% probability of inheriting the condition [5]. This condition follows an autosomal dominant inheritance pattern, whereby a single mutation in one of the genes is sufficient to cause HCM [6]. The disease may manifest at any age, but the clinical symptoms typically emerge during adolescence or early adulthood. In some patients, however, disease progression may be delayed [5]. HCM is associated with an elevated risk of sudden cardiac death (SCD), particularly among young athletes, where it is one of the leading causes of SCD [7]. Consequently, HCM represents a significant contributor to hospitalizations and is a risk factor for heart failure in patients with advanced stages of the disease. Despite recent advances in diagnostic techniques and therapeutic modalities, a significant number of cases remain undiagnosed, thereby complicating the development of effective preventive and therapeutic strategies [8]. The underlying pathogenesis involves mutations in sarcomeric proteins, such as encoding

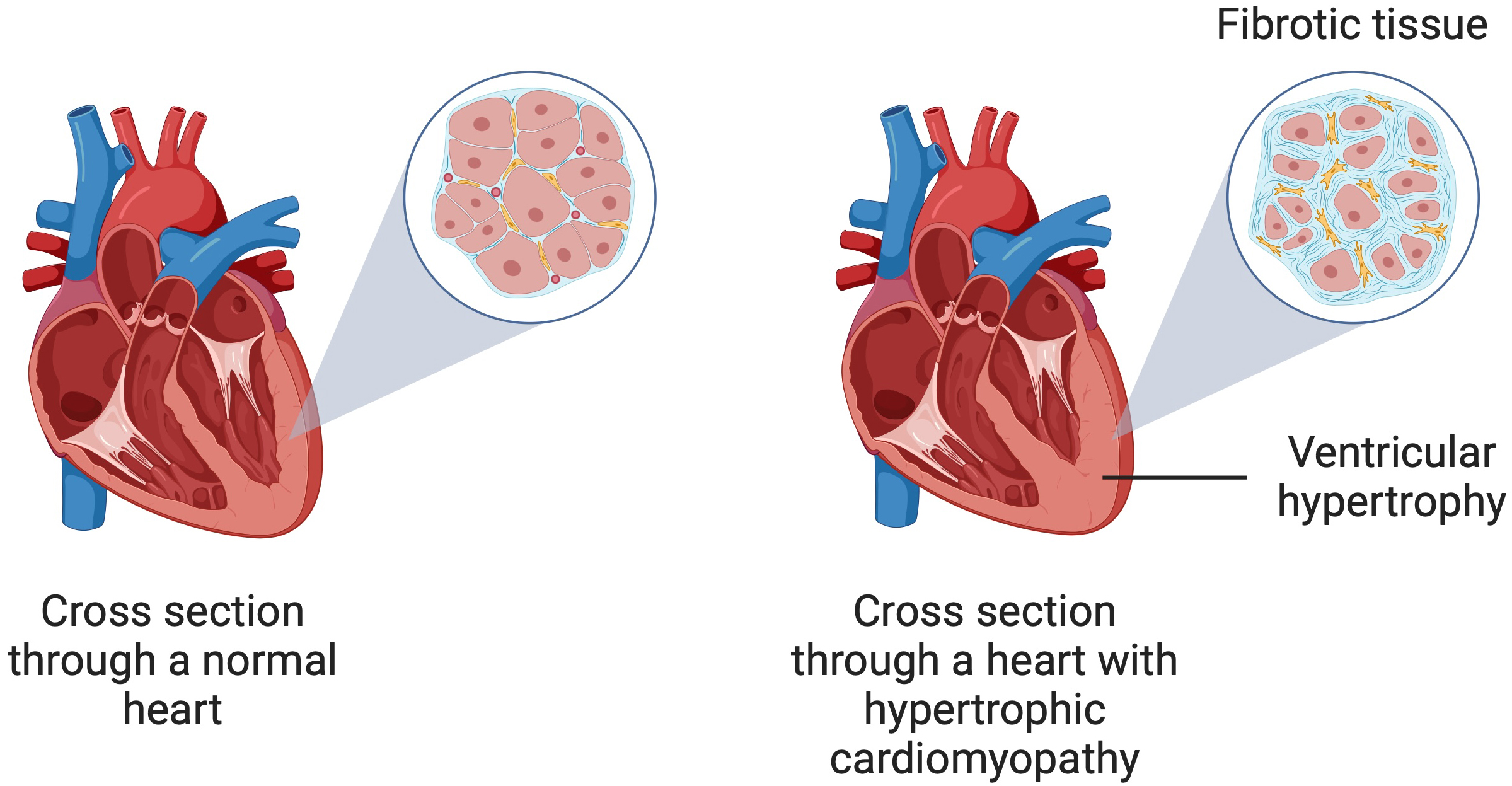

Fig. 1.

Fig. 1. A schematic illustration of hypertrophic cardiomyopathy showing ventricular hypertrophy and myocardial fibrosis. Created in BioRender. Kiełbowski, K. (2024) https://BioRender.com/q07s623.

Myocardial fibrosis is a complex and multifactorial process, which can develop after primary inflammatory processes, including cardiac sarcoidosis, acute myocarditis or genetically determined cardiomyopathies [18, 19, 20]. Furthermore, immune dysregulation and chronic inflammation, cardiac damage due to myocardial infarction, or pressure overload are also involved in the process of cardiac fibrosis development [21, 22, 23]. It leads to negative remodeling of the interstitial structure of the myocardium through excessive deposition of extracellular matrix (ECM) proteins in the cardiac interstitia. Collagen is synthesized most intensively, leading to an increased percentage of collagen fibers throughout the myocardial tissue [24, 25]. Therefore, the ECM plays a key role in regulating cardiac function [21]. Two types of fibrosis predominate in HCM—interstitial-perimyocytic and scar-like (replacement) fibrosis. It is estimated that up to one-third of the myocardium in HCM is covered by fibrosis, leading to asymmetric left ventricular thickening, reduced compliance, and progressive myocardial fibrosis. Furthermore, a degree of left ventricular fibrosis exceeding 20% is considered a high-risk condition associated with significant diastolic dysfunction [26].

Cardiac fibroblasts play a central role in the fibrosis process because they mediate intercellular communication between cardiomyocytes, inflammatory cells, and endothelial cells [27]. The phenotypic change of fibroblasts to myofibroblasts leads to a reduced rate of ECM degradation and increased collagen synthesis [28]. Additionally, the ECM influences cells such as myocytes and macrophages by regulating mechanical tension and controlling the availability of growth factors and matrix proteins [29]. Fibroblast activation occurs through communication between macrophages, fibroblasts, and cardiomyocytes in cardiac tissue, with chemokines and inflammatory cytokines playing a role in inducing this phenotypic change.

The primary factors promoting fibroblast transition include endothelin-1, angiotensin II (Ang II), platelet-derived growth factor (PDGF), fibroblast growth factor, interleukin (IL)-6, IL-4, IL-1, and transforming growth factor-

Genes encoding key proteins likely involved in this process are noteworthy. For instance, the type I/II collagen-binding prolargin encoded by PRELP and the COL22A1 gene, which encodes the alpha chain of collagen XXII, expressed in tendon-muscle junctions, are implicated [32]. These mechanisms, involving mitochondrial and cellular stress, contribute to the hypertrophic response in the heart. Although the initiating signalling pathways vary, they converge on common pathways that alter cell metabolism and result in HCM [33].

Late gadolinium enhancement (LGE) and extracellular volume (ECV) may be key indicators in the diagnosis of HCM. Although both indices are highly effective in the assessment of sudden cardiac death, it is LGE that has a stronger association with the risk of non-sustained ventricular tachycardia (NSVT) and diastolic dysfunction [34]. The determined receiver operating characteristic curve (ROC) curve for the extent of LGE in specific left ventricular segments obtained a high area under curve (AUC) value of 0.861 [35]. An even more reliable and repeated instrument in assessing risk classification in HCM based on variability and extent of cardiac scarring is LGE entropy [36]. Similar to the LGE entropy, LGE rate may discover an important role in the surveillance and monitoring of HCM patients [37]. Therefore, a thorough understanding of the molecular mechanisms regulating LGE in patients with HCM, may contribute to the stratification of protein biomarkers by proteomic profiling [38].

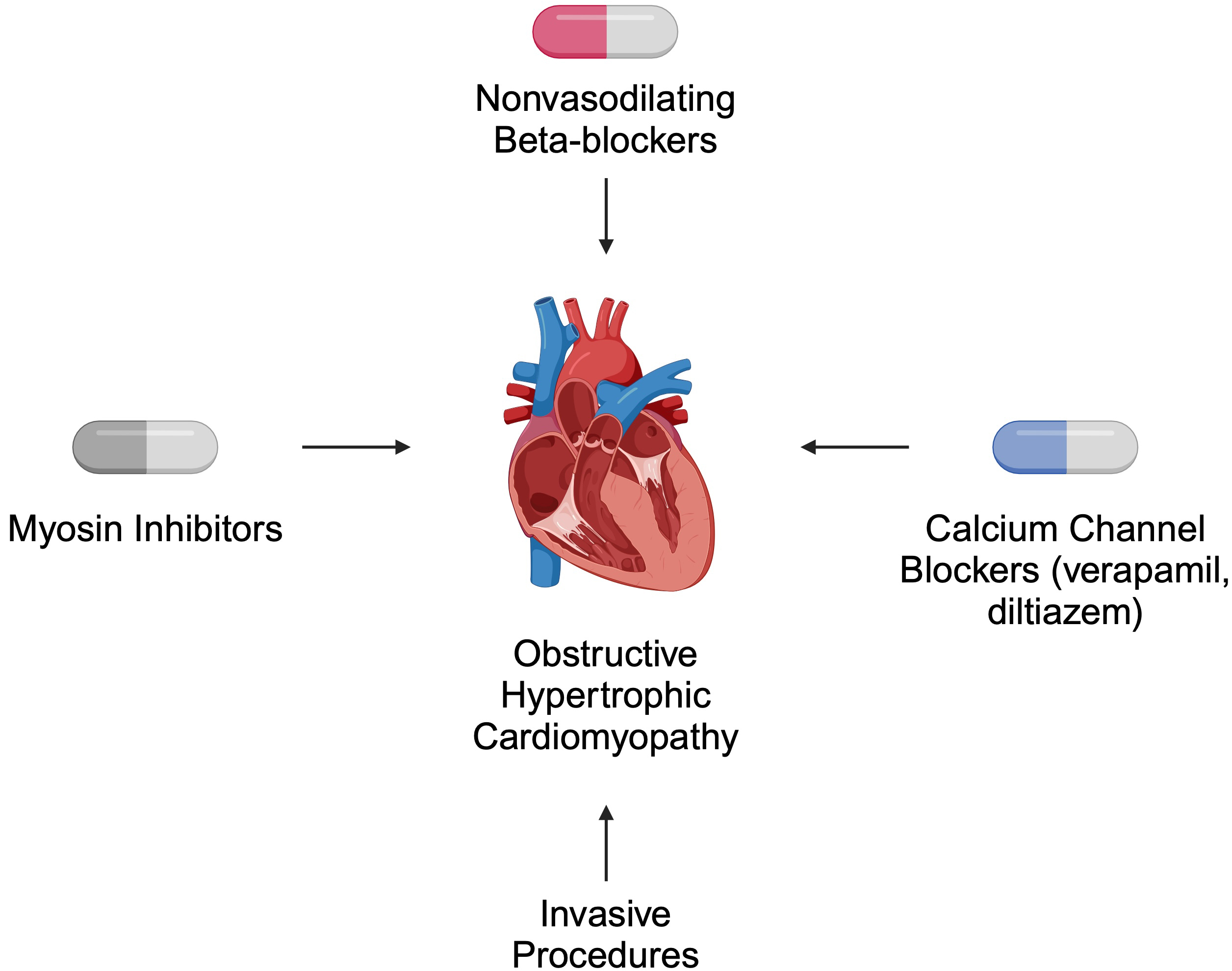

Both pharmacological and invasive treatment strategies are recommended for patients with HCM. In obstructive disease, the primary role of pharmacotherapy is symptom relief [39]. According to the 2024 American Heart Association (AHA)/American College of Cardiology (ACC)/American Medical Society for Sports Medicine (AMSSM)/Heart Rhythm Society (HRS)/Pediatric and Congenital Electrophysiology Society (PACES)/Society of Cardiovascular Magnetic Resonance (SCMR) guidelines, non-vasodilating beta-blockers are suggested as first-line therapy. Verapamil and diltiazem are alternatives for patients who cannot tolerate beta-blockers. For non-responders, myosin inhibitors such as mavacamten are recommended. Invasive approaches, such as septal reduction therapy, are offered to patients who do not respond to pharmacotherapy [39] (Fig. 2).

Fig. 2.

Fig. 2. Selected recommended treatment strategies for patients with obstructive hypertrophic cardiomyopathy. Created in BioRender. Kiełbowski, K. (2024) https://BioRender.com/a56h896.

HCM is an example of single-gene disorder, characterized by an autosomal dominant inheritance pattern. Genetic mutations disrupt the structure and functionality of the myocardium, exerting a profound influence on the fibrotic processes that define disease progression [15]. The primary genetic contributors to HCM are mutations in sarcomere proteins, particularly those in the MYH7 and MYBPC3 genes, which are the most frequently implicated genes across global HCM populations [40]. These genes encode

Non-sarcomeric genetic mutations play a substantial role in the fibrotic processes observed in HCM, influencing cellular stability, calcium homeostasis, and overall myocardial function [48]. Mutations in the PLN gene affect calcium cycling by impairing the reuptake of calcium into the sarcoplasmic reticulum, which results in elevated cytoplasmic calcium concentrations [49, 50]. This dysregulation of calcium handling not only disrupts cardiomyocyte relaxation but also activates profibrotic pathways [51]. An increase in cytoplasmic calcium is associated with the activation of the TGF-

Cardiac fibrosis is a pathological process characterised by the excessive deposition of ECM proteins in response to pathophysiological stimuli, leading to scarring of heart tissue. Patients with HCM experience significant levels of cardiac fibrosis, which can result in diastolic dysfunction [26]. One of the primary drivers of fibrosis is fibroblast activation. Fibroblasts transform into myofibroblasts, producing an excess of ECM. The interaction between cardiomyocytes and fibroblasts, such as through the TGF-

The cellular mechanisms of fibrosis in HCM involve intricate interactions between cardiomyocytes, fibroblasts, and immune system cells. Endothelial-to-mesenchymal transition (EndoMT) is a process in which endothelial cells transform into mesenchymal cells, promoting fibrosis [64]. In HCM, EndoMT contributes to increased numbers of fibroblasts and myofibroblasts within cardiac tissue. It is suggested that factors such as TGF-

Cells of the immune system, such as macrophages and lymphocytes, also play an important role in fibrosis processes in HCM [67]. In patients with HCM and acute clinical worsening, myocardial biopsy often demonstrates inflammatory infiltration that is associated with necrosis of myocytes [22]. Pro-inflammatory cytokines such as tumour necrosis factor-

When discussing tissue fibrosis and signaling pathways, it is crucial to focus on TGF-

Several studies have investigated the relationship between TGF-

Huang et al. [77] recently examined TGF-

Apart from EGR1, TGF-

Recently, TGF-

Recently, significant attention has been directed toward regulatory mechanisms that mediate gene expression. These epigenetic mechanisms often involve non-coding RNA, such as microRNA (miRNA). These small molecules, typically about 20 nucleotides in length, bind to their target mRNA to suppress translation. The importance of miRNAs was highlighted in 2024 when the Nobel Prize in Medicine and Physiology was awarded to the discoverers of these molecules [88].

More than 10 years ago, Bagnall et al. [89] analyzed the miRNA profile in a double mutant mouse HCM model. Among their findings, the authors observed that microRNA- 1 (miR-1) expression was reduced to a pre-disease state. This finding aligns with more recent research. Specifically, TGF-

Monitoring TGF-

The effect of Ang II on cardiac hypertrophy depends on the activation of specific receptors. Activation of the pro-hypertrophic Ang type 1 receptor stimulates phosphorylase C, promotes protein kinase C, and mobilises Ca2+ ions. This cascade activates nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide phosphate (NADPH) oxidase and alters cardiomyocyte metabolism, ultimately leading to pathological cardiac hypertrophy [94]. Interestingly, Ang II enhances the expression of connective tissue growth factor, an ECM protein, while downregulating epidermal growth factor receptor expression. This regulation is mediated by extracellular signal-regulated kinase 1/2 (ERK1/2), a member of the MAPK pathway [95]. An important mechanism has been observed in a mouse model, where Ang II and phenylephrine infusion resulted in greater upregulation of insulin-like growth factor-1 (IGF-1) receptor expression in myofibroblasts than in cardiomyocytes. The study also suggested that IGF-1 attenuates interstitial myocardial fibrosis by downregulating the expression of rho-associated coiled-coil containing kinase (ROCK)2-mediated

Another mechanism contributing to myocardial fibrosis involves the effect of Ang II on the upregulation of wingless-type MMTV integration site family, member 3a (WNT3a) in cardiomyocytes. This promotes the paracrine transformation of fibroblasts, enhancing fibrosis through increased expression of

The literature demonstrates conflicting results on the efficacy of RAAS inhibition in reducing cardiac fibrosis in patients with HCM [99]. Recently, the phase 2b clinical trial investigated the use of valsartan (AngII receptor blocker) showed improved cardiac functionality and structure in patients with early stage HCM [100]. However, according to the VANISH trial, valsartan was not effective in patients with subclinical HCM [101].

The interaction of a ligand with its corresponding receptor activates the Janus kinase (JAK)/signal transducers and activators of transcription 3 (STAT3) signalling pathway. This leads to autophosphorylation of the JAK kinase, which is bound to the receptor, by phosphorylating its tyrosine residue. STAT3 is subsequently phosphorylated, causing it to dissociate and form a dimer. These STAT3 dimers regulate transcription by binding to promoters in the cell nucleus. Because this pathway is activated by factors promoting fibroblast activation—such as endothelin-1, Ang II, vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF), PDGF, TGF-

Interestingly, the peptide hormone Elabela inhibited myocardial fibrosis in mouse models by suppressing the IL-6/STAT3 signalling pathway and activating the cystine–glutamate antiporter xCT/glutathione peroxidase pathway [104]. Obesity and diet are also significant factors influencing HCM progression. Animal studies have shown that a high-fat, corn oil-rich diet that induces a type 2 diabetes phenotype promotes left ventricular collagen synthesis. This occurs through increased IL-6 and reactive oxygen species synthesis, activating the JAK1/STAT3/Ang II/TGF-

Furthermore, adipose tissue in obese individuals leads to elevated levels of the adipokine resistin, which promotes fibroblast differentiation by activating the JAK2/STAT3 and c-Jun N-terminal kinase (JNK-cJun) pathways. This, in turn, drives the expression of numerous ECM proteins, contributing to chronic cardiac fibrosis, particularly in overweight and diabetic individuals [106]. Aerobic training over a 28-day period has been shown to inhibit negative myocardial remodelling via miR-574-3p in animal models, which suppresses IL-6 [107]. miR-326, inhibits myocardial hypertrophy by downregulating the JAK/STAT and MAPK signalling pathways. These miRNA molecules may have significant roles in HCM progression and represent potential therapeutic targets [108]. Women with HCM experience significantly greater age-related deterioration in heart function after menopause than men of the same age group [109]. Protein arginine methyltransferase 7 (PRMT7) is an important factor in this pathology. Reduced PREMT7 expression in the cardiomyocytes of postmenopausal women diminishes the alleviation of inflammation and oxidative stress associated with menopause. PRMT7, through STAT3 activation, induces the expression of SOCS3, a direct inhibitor of the JAK/STAT pathway [110]. STAT3 regulates the expression of Collagen-IV (Col-IV) which is linked to interstitial fibrosis. STAT3/Col-IV expression has been shown to be different between HCM patients with different phenotypes of fibrosis [111]. Table 1 (Ref. [73, 76, 84, 99, 100, 101, 111]) presents a summary of the potential involvement of TGF-

| Pathway | Relationship with hypertrophic cardiomyopathy and cardiac fibrosis | References |

| TGF- | TGF- | [73, 76, 84] |

| TGF- | ||

| Increased expression of SMAD2 and SMAD3 (pro-fibrotic signalling elements of the TGF pathway) was found in patients with obstructive HCM. | ||

| RAAS | The use of valsartan provided beneficial outcomes in patients with early HCM. However, conflicting results were published regarding the inhibition of RAAS and cardiac fibrosis. | [99, 100, 101] |

| JAK/STAT3 | Analysis of STAT3 could be used to analyze fibrosis phenotypes in patients. | [111] |

TGF-

The WNT/

WNT3a and WNT5a are key ligands promoting this pathway, although they act through different mechanisms. WNT3a facilitates the nuclear translocation of

The profibrotic response can be further enhanced by the synergistic effects of WNT3a and TGF-

In mice with myocardial infarction, collagen synthesis was inhibited by circNSD1 knockdown. CircNSD1 acts as a sponge for miRNA-429-3p, and its knockdown reduces sulfatase1(SULF1) expression and WNT/

Doxorubicin has been shown to activate the WNT/

A potential protein enhancing the production of fibrosis-associated compounds, such as

Finally, inhibition of Col-I/III and

Molecules belonging to the MAPK family play a significant role in negative cardiac remodelling. These include kinases such as ERK1/2, p38MAPK, and JNK1/2 [125]. Suppression of ERK in a mouse model of cardiomyopathy inhibited myocardial fibrosis [126]. One mechanism for the inhibition of cardiac fibroblasts involves SO2-induced sulphenylation of ERK1/2 [127]. Additionally, the use of ERK1/2 inhibitors may counteract the profibrotic effects elicited by the TNF family member CD137 [128]. Myocardial fibrosis can also be mitigated through inhibition of the ERK1/2-matrix metalloproteinase-9 (MMP- 9) axis via activation of the G protein-coupled oestrogen receptor 30 [129].

The SerpinE2 protein exhibits antagonistic effects, interacting with membrane proteins such as low-density lipoprotein receptor-related protein 1 (LPR1) and urokinase-type plasminogen activator receptor (uPAR) to activate ERK1/2 and

The p38MAPK plays a crucial role in cardiac fibrosis and hypertrophy. Inhibition of this kinase reduces cardiac hypertrophy and preserves collagen synthesis in neonatal rat cardiac myocytes and IGF-1-induced fibroblasts [132]. In septic mice,

Interestingly, p38MAPK activation leads to a decrease in Cx43, a protein required for normal myocardial function, disrupting the balance between microtubule depolymerisation and polymerisation in the myocardium [134]. IL-17 regulates p38MAPK, promoting negative cardiac remodelling by upregulating C-C motif ligand 2 (CCL2) and activating AP-1 via the adaptor protein 1 (Act1)/TNF receptor-associated factor 6 (TRAF6)/p38MAPK pathway [135]. JNK1/2 also contributes to the synthesis of profibrotic factors through the transforming growth factor beta-activated kinase 1-p38 (TAK1-p38)/JNK1/2 regulatory axis. Ubiquitin-specific protease 19 negatively affects this axis by inhibiting the transition of fibroblasts to myofibroblasts [136]. Similarly, zinc finger protein zinc finger and BTB domain containing 20 (ZBTB20) may inhibit fibrosis after myocardial infarction by targeting the TNF-

In HCM, Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes (KEGG) enrichment analysis demonstrates significant dysregulation of the MAPK pathway [138]. Furthermore, dysregulation of MAPK signalling is associated with the worsening of heart failure [139].

In the previous sections, we have focused on the genetic background of HCM pathogenesis and the potential involvement of signaling pathways in hypertrophy and cardiac fibrosis. Recently, there is growing attention towards mitochondrial dysfunction as a pathogenic element in the occurrence of HCM. Analyses of the HCM cardiac samples demonstrate impaired energy metabolism. Diseased hearts show signs of disrupted fatty acid metabolism, with reduced expression of enzymes involved in metabolism and transport of acylcarnitines. Moreover, the state of HCM is associated with impaired structure of mitochondria and their ability to perform oxidative phosphorylation, together with reduced levels of ATP, thus demonstrating energy deprivation [33]. In addition, HCM hearts show alterations in the expression of enzymes involved in the mitochondrial transport of Ca2+, which is also involved in adenosine triphosphate (ATP) production [140]. Consequently, disturbances in mitochondrial functionality are considered to be involved in HCM. Perhaps, mitochondrial abnormalities are also linked with the processes of cardiac fibrosis. Tian et al. [141] showed that stimulation of cardiac fibroblasts with TGF-

As previously mentioned, either pharmacological therapy or invasive procedures can be performed in patients with HCM. Pharmacological treatment represents an initial approach in these patients. Recent investigations focus on studying a relatively novel class of therapeutics – myosin inhibitors. An animal study demonstrated mavacamten to suppress cardiac contractility and reduce left ventricle wall thickness. Importantly, if administered early, the drug significantly reduced fibrotic changes in the cardiac tissues. However, administration of the therapeutic in advanced hypertrophy did not reduce fibrotic lesions [143]. Thus, by modulating fibrotic mechanisms, the drug can reduce the risk of developing arrhythmias [16] and further deteriorating heart functionality. The EXPLORER-HCM phase 3 clinical trial proved the efficacy of mavacamten in obstructive HCM, as the drug improved left ventricular outflow tract obstruction and NYHA class, compared to placebo [144]. In 2022, mavacamten was approved by the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) to treat patients with obstructive HCM [145]. A recently published meta-analysis that analyzed 3 randomized controlled trials comparing mavacamten and placebo supports the benefits of myosin inhibition, but warrants further research regarding the issue of treatment-emergent adverse events [146]. Aficamten, a next-generation myosin inhibitor [147], is currently being investigated in patients with HCM. The most recent clinical trials demonstrated the beneficial effects of aficamten in patients with obstructive [148, 149] and nonobstructive HCM [150].

Induced pluripotent stem cells (iPSCs) offer an interesting insight into the pathophysiology of cardiac diseases and potential therapeutic methods. Fibroblasts can be obtained and switched towards iPSCs, which then can be differentiated into cardiomyocytes or other cellular lineages. We have discussed the potential benefits of iPSCs in myocardial infarction in a previous paper [151]. This method is exciting for studying the pathogenesis of diseases, as it is possible to use patient-derived iPSCs and differentiate them towards cardiomyocytes. For instance, Shiba et al. [152] generated iPSCs using peripheral blood mononuclear cells of patients with a DSG2 mutation, which was associated with cardiomyopathy. Researchers then introduced the proper gene to the iPSCs through the adeno-associated viruses. Gene replacement improved the contraction force of the three-dimensional (3D) self-organized tissue rings, thus demonstrating enormous potential in iPSCs. iPSCs are also being used to study cardiac hypertrophy. Rosales and Lizcano [153] studied iPSC-derived cardiomyocytes and identified histone demethylase JMJD2A as a probable enzyme involved in the development of hypertrophy. In the context of this review, iPSC models could be implemented to study signaling pathways or molecules implemented in the development of HCM or HCM-associated cardiac fibrosis.

HCM is a disease with a complex pathogenesis, involving a genetic background and the activity of several signalling pathways. Aberrant activity of these cascades is associated with pro-fibrotic changes in cardiac tissue, contributing to the progression of heart failure, the occurrence of MACEs, and a generally poor prognosis. We are currently in an era of large-scale transcriptomic and proteomic studies, which broadly and comprehensively analyse the dysregulated expression of genes and proteins in patients with HCM. These studies have identified hub genes associated with the pathogenesis of HCM, highlighting potential therapeutic targets. Several signalling pathways are implicated in cardiac fibrosis, with the TGF-

AP conceptualized the review paper. PS, JP, EB, and KK performed a thorough literature search. PS, JP, EB, KK, and AP wrote the paper. All authors contributed to editorial changes in the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript. All authors have participated sufficiently in the work and agreed to be accountable for all aspects of the work.

Not applicable.

Not applicable.

This research received no external funding.

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

Publisher’s Note: IMR Press stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.