1 Department of Cardiovascular Medicine, JR Hiroshima Hospital, 732-0057 Hiroshima, Japan

Abstract

Atrial fibrillation (AF) is a complication that occurs following a spasm provocation test (SPT) with acetylcholine (ACh). However, the characteristics of patients with AF remain unclear. Furthermore, the association of AF with the outcome of the coronary microvascular function test (CMFT) is unknown. This study aimed to evaluate whether patients with angina with non-obstructive coronary artery disease (ANOCA) who developed AF during SPT with ACh had any clinical characteristics. Additionally, we assessed the association of AF with the CMFT results.

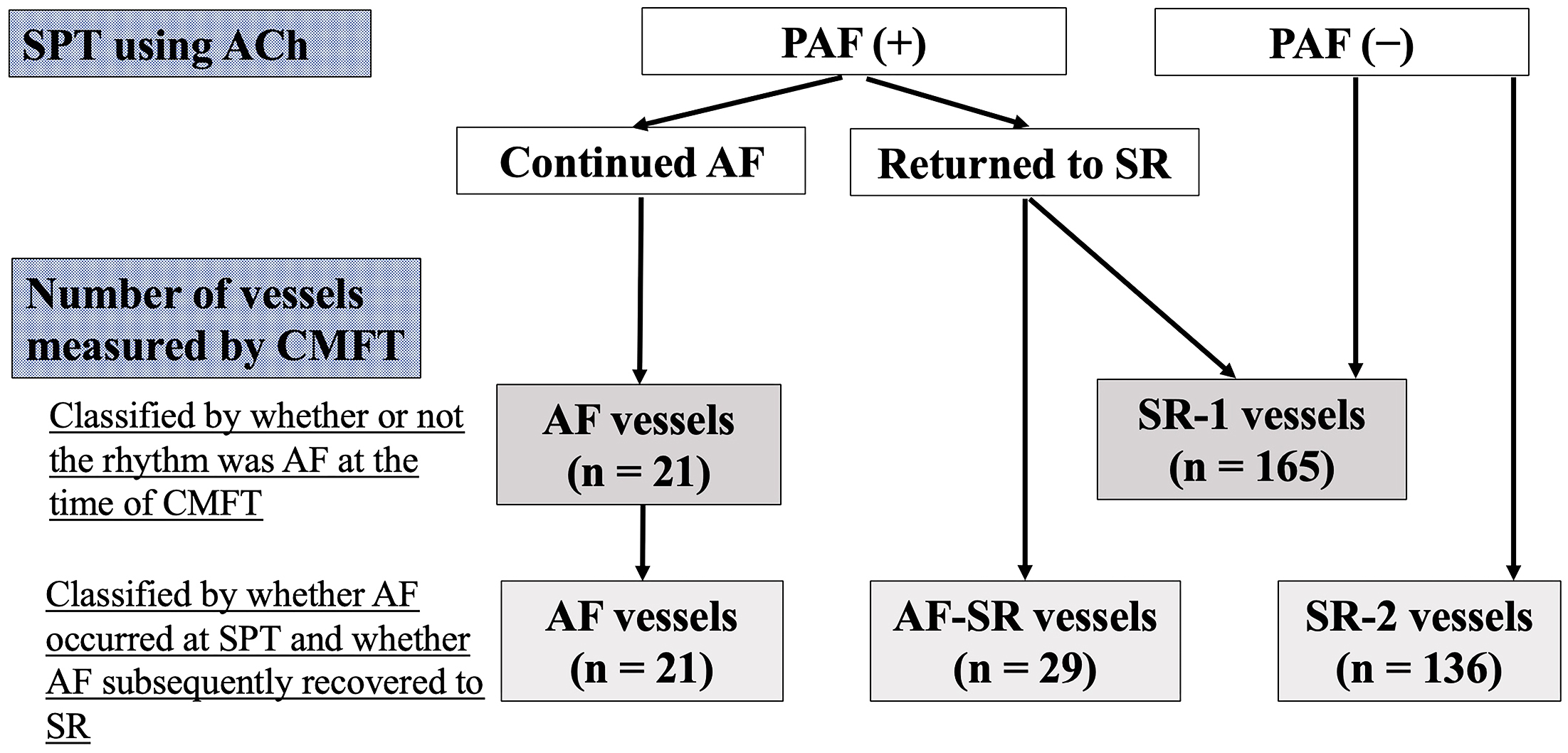

We included 123 patients with ANOCA who underwent SPT and CMFT. We defined AF as AF during ACh provocation. The coronary arteries that demonstrated AF before CMFT were defined as AF vessels (n = 21) and those in sinus rhythm (SR) were defined as SR-1 vessels (n = 165). Vessels that were restored to sinus rhythm immediately following AF were defined as AF-SR vessels (n = 29) and those that remained in sinus rhythm for some time were defined as SR-2 vessels (n = 136). Coronary flow reserve (CFR) and index of microcirculatory resistance (IMR) were obtained, and CFR of <2.0 and/or IMR of ≥25 were diagnosed as coronary microvascular dysfunction (CMD).

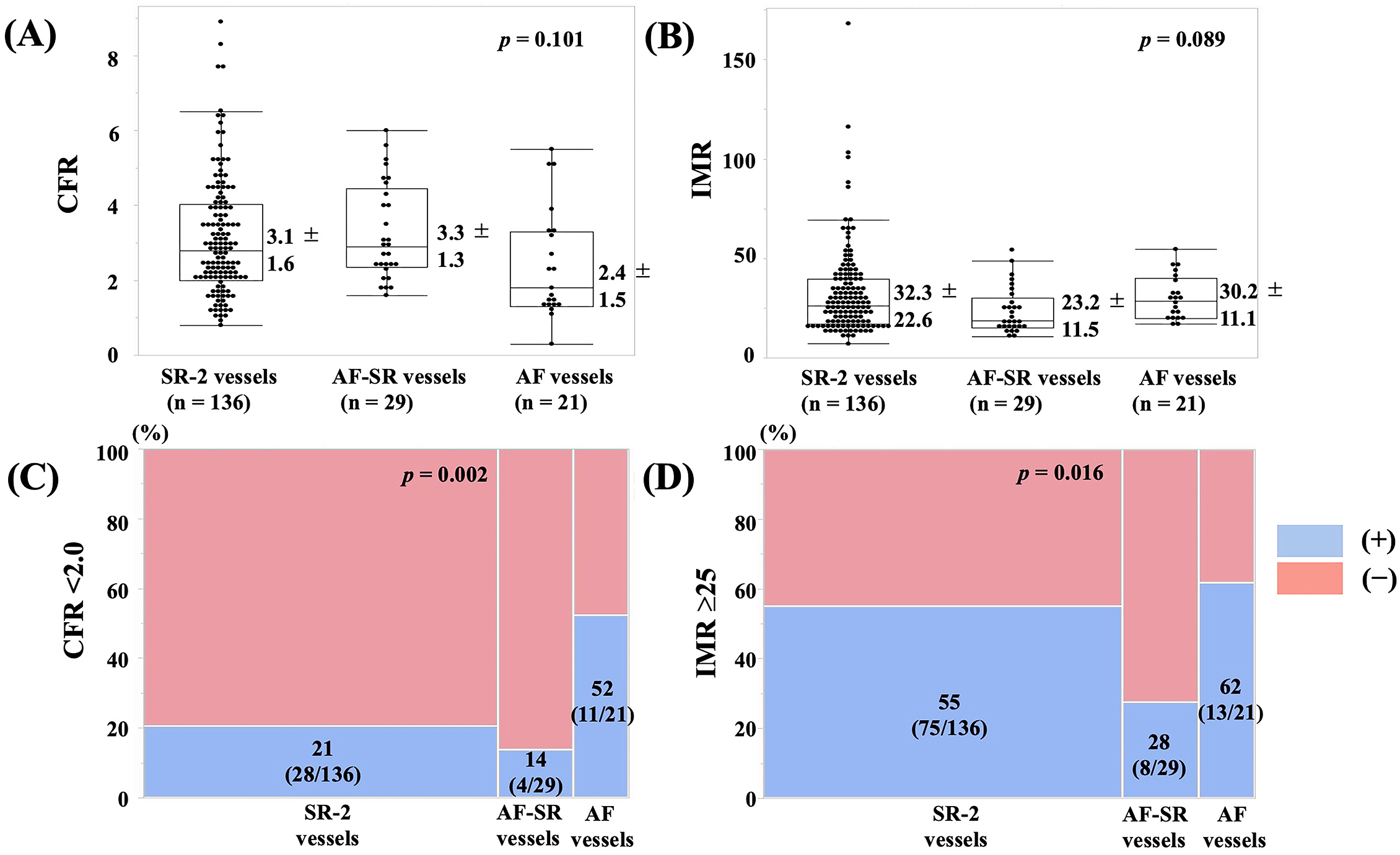

Of the 123 patients, 31 (25%) had AF but with no characteristic patient background. CFR was significantly lower in AF vessels than in SR-1 vessels (p = 0.035) and IMR did not differ between the two groups (p = 0.918). A study of the three groups that included AF-SR vessels revealed that IMR tended to be lower in AF-SR vessels than in the SR-2 and AF vessels (p = 0.089), and that the frequency of IMR of ≥25 was significantly lower than in the other two groups (p = 0.016).

AF occurred in 25% of SPTs with ACh, but the predictive clinical context remains unclear. Our results indicated that AF may affect the outcome of the CMFT. Thus, decisions for CMD management should be made with caution in the presence of AF.

Keywords

- acetylcholine

- coronary flow reserve

- coronary spasm

- index of microcirculatory resistance

- paroxysmal atrial fibrillation

- spasm provocation test

Angina with non-obstructive coronary artery disease (ANOCA) is a prevalent condition that has recently received increased attention [1, 2]. The leading causes of ANOCA are vasospastic angina (VSA), coronary microvascular dysfunction (CMD), or both [1, 2]. The coexistence of both underlying causes has a poor prognosis [3]. Treatment is superior for improving subjective symptoms in ANOCA with a known cause treated with pharmacological therapy [4]. Consequently, VSA is recommended to be identified using spasm provocation testing (SPT) and CMD with the coronary microvascular function test (CMFT).

SPT and CMFT are widely recognized for testing [1, 2]. However, which test should be performed first remains unestablished and also varies based on factors such as subjective symptoms, institutional experience, and policies. CMFT requires maximally dilated coronary arteries; thus, nitroglycerin (NTG) preadministration is mandatory. However, NTG preadministration may have a significant effect on SPT results [5]. Furthermore, patients with CMD (especially those with reduced coronary flow reserve [CFR]) demonstrate a poor prognosis [6], but VSA also causes cardiac arrest [7, 8]. Further, beta-blockers (the main treatment for CMD) [1] are restricted for treating VSA when administered alone [9]. Therefore, VSA must be diagnosed before beta-blocker administration. Hence, SPT is frequently administered before CMFT in Japan, including our institution.

Conversely, one of the complications of SPT with acetylcholine (ACh) is paroxysmal atrial fibrillation (PAF) [10, 11]. Clinical characteristics that cause PAF during SPT remain unclear. Furthermore, atrial fibrillation (AF) may affect CMFT testing, especially in the CFR [12, 13, 14, 15]. Furthermore, the effect of PAF on CMFT outcomes needs to be identified. We investigated the clinical characteristics of patients who underwent SPT and CMFT to investigate the etiology of ANOCA, the clinical characteristics of patients who developed PAF, and the association of PAF occurrence with CMFT outcomes.

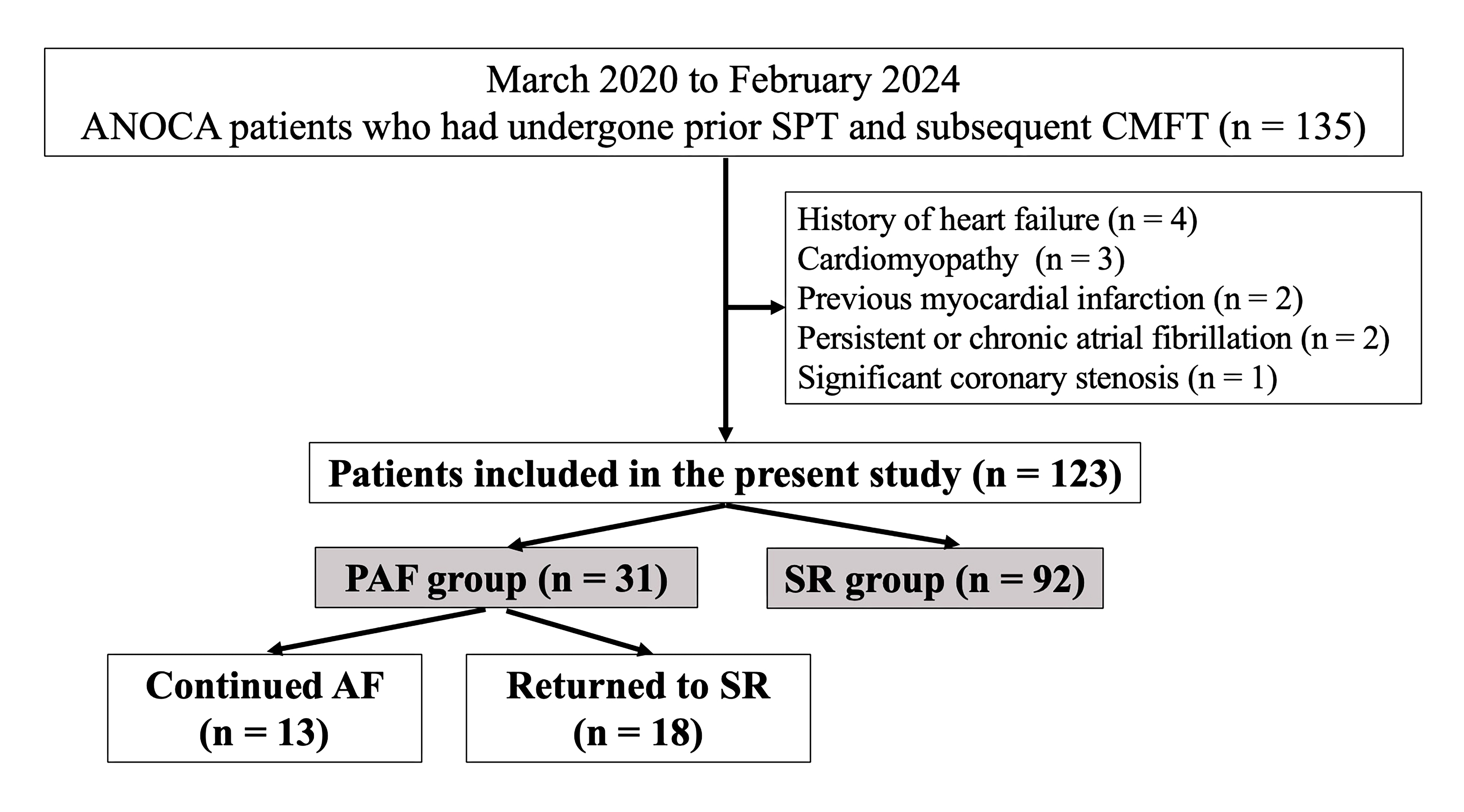

This retrospective observational study involved 135 patients who underwent prior SPT and subsequent CMFT at our institution from March 2020 to February 2024 to evaluate the ANOCA endotype. Patients in whom at least one coronary artery vessel could be assessed by SPT and CMFT were included. Patients who underwent percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI) were included if they had any anginal pain without concurrent significant stenosis. This study excluded patients who had heart failure (n = 4), cardiomyopathy (n = 3), previous myocardial infarction (n = 2), and significant coronary stenosis (% stenosis

Fig. 1.

Fig. 1. Flowchart of the study protocol (per patient). Abbreviations: AF, atrial fibrillation; ANOCA, angina with non-obstructive coronary artery disease; CMFT, coronary microvascular function test; PAF, paroxysmal atrial fibrillation; SPT, spasm provocation test; SR, sinus rhythm.

The SPT procedures utilized at our institution have been previously published [16]. SPT was conducted after the conventional diagnostic CAG test and used a percutaneous brachial or radial route with a 5 French (Fr) sheath and a diagnostic Judkins-type catheter. A 5-Fr gauge temporary pacing catheter (Bipolar Balloon Catheter, B. Braun, Melsungen, Germany) was introduced into the right ventricle and set to 50 beats per minute through the internal jugular vein or medial cubital vein. The left coronary artery (LCA) was injected after the initial CAG, with 50, 100, and 200 µg of ACh for a duration of 20 s, with a 3-min gap between each injection. CAG was conducted either immediately after the maximum ACh administration or following the coronary spasm provocation. A dose of 0.3 mg of NTG was immediately delivered to the coronary artery if the introduction of ACh into the LCA induced prolonged contractions of the coronary arteries or caused unstable hemodynamics. Approximately 20, 50, and 80 µg of ACh were injected into the right coronary artery (RCA) for 20 s, with 3-min intervals between each dose, after inducing spasms in the LCA. Ergonovine maleate (EM, Fuji Pharma, Tokyo, Japan) was administered intra-coronarily in patients with negative responses to ACh provocation, as described in an earlier study [16]. The attending physician had the authority to decide on EM administration. CAG was repeated by injecting NTG into the coronary artery after conducting all the provocation tests for the LCA and RCA. The outcome was classified as “not diagnosed” (ND) if the subsequently conducted SPT produced a negative result after the NTG injection.

The methods used for the CMFT have been previously detailed [16]. A PressureWire X Cabled guidewire manufactured by Abbot Laboratories in Abbot Park, IL, USA, was used with a pressure-temperature sensor tip. An Abbott Vascular RadiAnalyzerTM Xpress (Santa Clara, CA, USA) was employed to evaluate the parameters. A PressureWire was attached to the distal portion of the left anterior descending coronary artery (LAD) and RCA, and three 3 mL of saline injections were administered at room temperature to establish a thermodilution curve for measuring the resting mean transit time (Tmn). Adenosine triphosphate (ATP) was intravenously administered through the peripheral veins at 160 µg/kg/min to stimulate blood flow (hyperemia). The proximal aortic pressure (Pa), distal pressure (Pd), and Tmn were measured during maximum hyperemia. The fractional flow reserve (FFR) was determined by calculating the lowest average of three consecutive beats under stable hyperemia. CFR was calculated as the ratio between the resting Tmn and the hyperemic Tmn. The index of microcirculatory resistance (IMR) was calculated during hyperemia with the formula Pd

The methodology for confirming the diameter of the coronary artery has been previously described [16]. Segments demonstrating both spasticity and atherosclerosis were selected for the quantitative study. The study was conducted with the mean values derived from the three measurements. The percentage deviation from the baseline angiographic data was utilized to quantify the alterations in the coronary artery diameter in response to ACh and NTG infusions. Atherosclerotic lesions were categorized as those with stenosis of

Coronary spasm was the epicardial coronary artery narrowing of

We strictly monitored AF occurrence during SPT. PAF is characterized as AF that was absent before SPT and emerged after ACh provocations, regardless of whether it persisted for

Fig. 2.

Fig. 2. Flowchart of the study protocol (per vessel). Abbreviations: AF, atrial fibrillation; CMFT, coronary microvascular function test; PAF, paroxysmal atrial fibrillation; SPT, spasm provocation test; SR, sinus rhythm; ACh, acetylcholine.

Information on the familial history of coronary artery disease, present smoking behavior, and alcohol intake was collected [16]. The traditional definition of hypertension was utilized. The estimated glomerular filtration rate (mL/min/1.73 m2) was computed with an established formula [19]. Chronic kidney disease was evaluated based on the approved criteria. Both medication administration for dyslipidemia and having a low-density lipoprotein cholesterol level of

Continuous variables with normal distributions are expressed as means and standard deviations, and those variables with nonnormal distributions are presented as medians (interquartile ranges). Categorical variables are expressed as frequencies (%). Student’s unpaired t-test, the Wilcoxon signed-rank test, or Chi-square test were utilized to compare baseline characteristics between the groups, i.e., PAF and SR group or AF and SR vessels, or AF vessels, AF-SR vessels, and SR vessels. Logistic regression analysis was conducted to identify the factors that contributed to a CFR of

All statistical analyses were conducted with JMP (version 17; SAS Institute Inc., Cary, NC, USA). p-values of

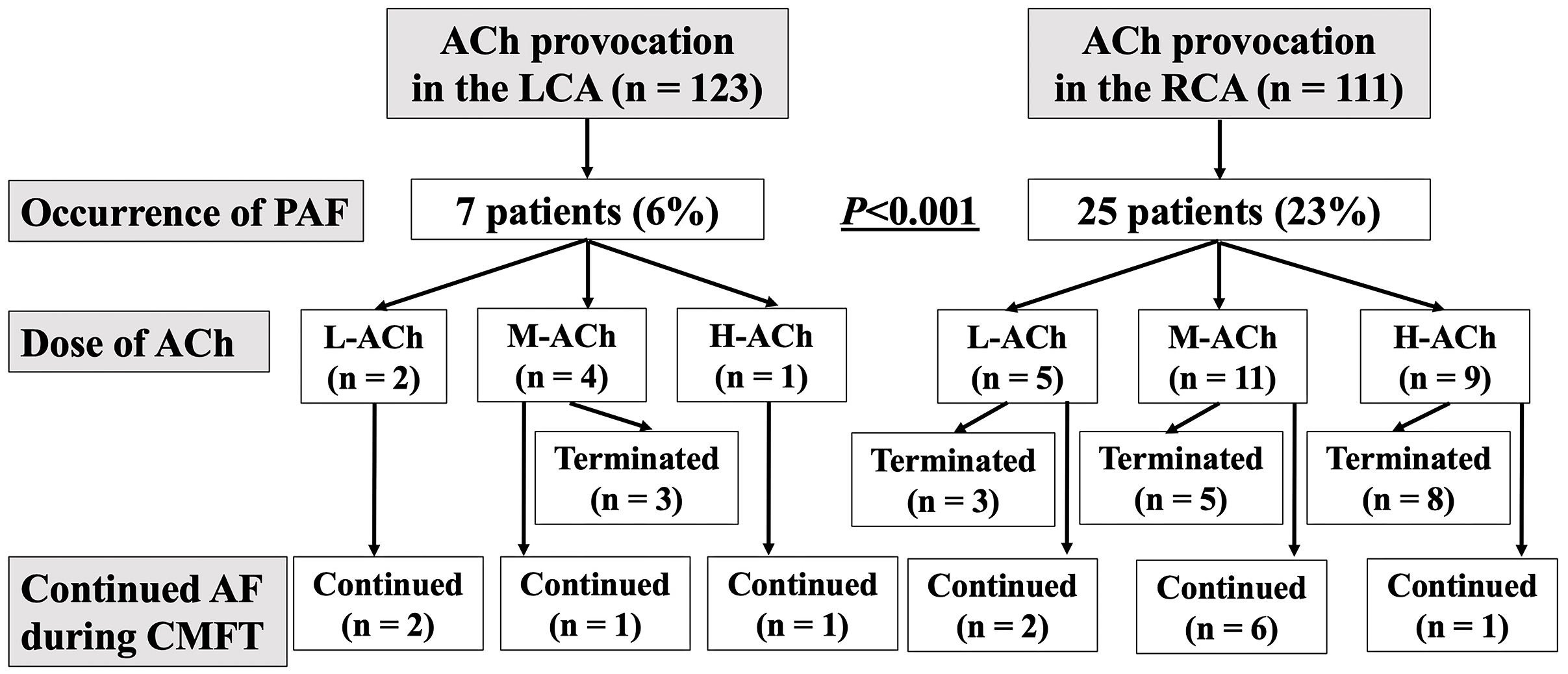

ACh provocation of LCA was performed in all 123 patients. ACh provocation was not performed in 12 patients due to the small size of the RCA or the judgment of the chief operator. ACh provocation of the RCA was performed in 111 patients. Additional use of EM provocation was performed in 26 (21%) patients. Hence, 31 (25%) patients had PAF (PAF group), consisting of 24 during RCA provocation, 6 during LCA provocation, and 1 in both coronary arteries (Fig. 3). One case in which PAF occurred in both LCA and RCA was calculated as LCA and RCA, respectively. PAF was reported in 7 (6%) of 123 patients with LCA provocation and 25 (23%) of 111 patients with RCA provocation, with PAF occurring more frequently during RCA provocation (p

Fig. 3.

Fig. 3. Flowchart of PAF occurrence during SPT. Abbreviations: SPT, spasm provocation test; ACh, acetylcholine; AF, atrial fibrillation; CMFT, coronary microvascular function test; H-ACh, high dose of acetylcholine; L-ACh, low dose of acetylcholine; LCA, left coronary artery; M-ACh, moderate dose of acetylcholine; PAF, paroxysmal atrial fibrillation; RCA, right coronary artery.

No significant differences were found in the background of the three patient groups, including those with persistent AF until CMFT (n = 13), those who quickly recovered to SR (n = 18), and those who remained in SR (n = 92 patients) although not shown in the data.

Table 1 shows patient characteristics. No significant differences were found between the two groups. The frequency of female patients taking coronary vasodilators tended to be higher in the PAF group than in the SR group. Additionally, the E/e’ on ultrasound cardiography and NT-proBNP levels also tended to be lower than those in the SR group. Atherosclerotic lesion frequencies and PCI history were similar in the two groups, whereas the frequency of MB tended to be higher in the PAF group than in the SR group (p = 0.071). Positive SPT and CMD were comparable between the two groups.

| SR Group | PAF Group | p-value | ||

| No. (%) | 92 (75%) | 31 (25%) | ||

| Age (years) | 65 | 64 | 0.736 | |

| Male/Female sex | 43/49 | 9/22 | 0.084 | |

| Body mass index | 24.5 | 23.9 | 0.513 | |

| Coronary risk factors (%) | ||||

| Current smoker | 12 (13) | 2 (6) | 0.378 | |

| Hypertension | 57 (62) | 22 (71) | 0.365 | |

| Dyslipidemia | 51 (55) | 14 (45) | 0.322 | |

| Diabetes mellitus | 14 (15) | 4 (13) | 0.753 | |

| Family history of CAD (%) | 24 (26) | 10 (32) | 0.506 | |

| Alcohol drinker (%) | 42 (46) | 10 (32) | 0.192 | |

| CKD (%) | 27 (29) | 7 (23) | 0.137 | |

| Medications (%) | ||||

| Coronary vasodilators | 45 (49) | 21 (68) | 0.066 | |

| RAS inhibitors | 24 (26) | 5 (16) | 0.259 | |

| Beta-blockers | 8 (9) | 5 (16) | 0.244 | |

| Statins | 45 (49) | 12 (39) | 0.325 | |

| Anti-platelet therapy | 17 (18) | 5 (16) | 0.768 | |

| Blood chemistry parameters | ||||

| C-reactive protein (mg/dL) | 0.06 (0.03, 0.11) | 0.04 (0.02, 0.07) | 0.114 | |

| eGFR (mL/min/1.73 m2) | 67.5 | 70.8 | 0.268 | |

| NT-proBNP (pg/mL) | 71 (39, 142) | 50 (33, 96) | 0.062 | |

| Results of the UCG | ||||

| LA diameter (mm) | 34 | 32 | 0.125 | |

| LVEF (%) | 67 | 68 | 0.556 | |

| LVMI (g/m2) | 78 | 80 | 0.594 | |

| E/e’ | 11.2 | 9.6 | 0.084 | |

| Results of the CAG, SPT and CMFT | ||||

| Atherosclerosis (%) | 43 (47) | 15 (48) | 0.834 | |

| Myocardial bridging (%) | 18 (20) | 11 (35) | 0.071 | |

| History of PCI (%) | 5 (5) | 2 (6) | 0.833 | |

| Additional use of EM (%) | 20 (21) | 6 (19) | 0.779 | |

| Positive SPT (%) | 65 (71) | 20 (65) | 0.523 | |

| Presence of CMD (%) | 62 (67) | 18 (58) | 0.346 | |

Categorical variables are expressed as frequencies (percentages), and continuous variables are expressed as means

CMFTs were not measured in 60 vessels because of the small RCA (n = 7), inability to engage the catheter properly (n = 16), inability to insert the pressure wire into the targeted coronary artery (n = 5), the attending physicians’ decision (n = 29), and trouble with measuring equipment (n = 3). Hence, CMFT measurements were performed in 186 vessels. Table 2 summarizes the CAG, SPT, and CMFT results based on the vessels.

| SR-1 vessels | AF vessels | p-value | ||

| No. (%) | 165 (89) | 21 (11) | ||

| LAD/RCA | 105/65 | 11/10 | 0.316 | |

| Drugs provocative | ||||

| ACh L/M/H | 15/54/96 | 2/6/13 | 0.929 | |

| Additional use of EM (%) | 37 (22) | 5 (24) | 0.886 | |

| Atherosclerosis (%) | 57 (35) | 8 (38) | 0.748 | |

| VSA (%) | 90 (56) | 10 (48) | 0.455 | |

| Endotype of the coronary spasm | ||||

| Focal/Diffuse/MVS/None/ND | 40/50/20/48/7 | 9/1/6/5/0 | 0.021 | |

| Presence of focal spasm (%) | 40 (24) | 9 (43) | 0.068 | |

| Presence of diffuse spasm (%) | 50 (30) | 1 (5) | 0.014 | |

| Heart rate at CMFT (bpm) | 72 | 110 | ||

| Pa during ATP infusion (mmHg) | 93 | 93 | 0.853 | |

| (Numbers of vessels we were able to measure) | (140) | (14) | ||

| Pd during ATP infusion (mmHg) | 88 | 88 | 0.972 | |

| (Numbers of vessels we were able to measure) | (140) | (14) | ||

| Tmn at baseline (seconds) | 1.02 | 0.78 | 0.047 | |

| (Numbers of vessels we were able to measure) | (151) | (19) | ||

| Tmn during ATP infusion (seconds) | 0.37 | 0.35 | 0.770 | |

| (Numbers of vessels we were able to measure) | (151) | (19) | ||

| Baseline Pd/Pa | 0.98 | 0.98 | 0.619 | |

| FFR | 0.94 | 0.94 | 0.977 | |

| CFR | 3.2 | 2.4 | 0.035 | |

| CFR of | 32 (19) | 11 (52) | 0.001 | |

| IMR | 30.7 | 30.2 | 0.918 | |

| IMR | 83 (50) | 13 (62) | 0.316 | |

| CMD (%) | 92 (56) | 14 (67) | 0.342 | |

Data are expressed as frequencies (percentages or numbers in some data). Abbreviations: ACh, acetylcholine; AF, atrial fibrillation; ATP, adenosine triphosphate; CAG, coronary angiography; CFR, coronary flow reserve; CMD, coronary microvascular dysfunction; ND, not diagnosed; CMFT, coronary microvascular function test; EM, ergonovine maleate; FFR, fractional flow reserve; IMR, index of microcirculatory resistance; LAD, left anterior descending coronary artery; L/M/H, low/moderate/high dose of acetylcholine; MVS, microvascular spasm; ND, not diagnosed; No., numbers; Pa, aortic pressure; Pd, distal pressure; RCA, right coronary artery; SPT, spasm provocation test; SR, sinus rhythm; Tmn, transit mean time; VSA, vasospastic angina.

This study demonstrated 21 (11%) AF vessels and 165 (89%) SR-1 vessels. No significant differences were observed in LAD or RCA vessels, ACh dosage and additional EM administration, atherosclerosis presence, or coronary spasm frequency. Significant differences were observed between AF and SR-1 vessels in the coronary spasm endotypes (p = 0.021), with the incidence of diffuse spasm being lower in AF vessels (p = 0.014). The heart rate at the CMFT assessment was significantly higher in the AF vessels than in the SR-1 vessels (p

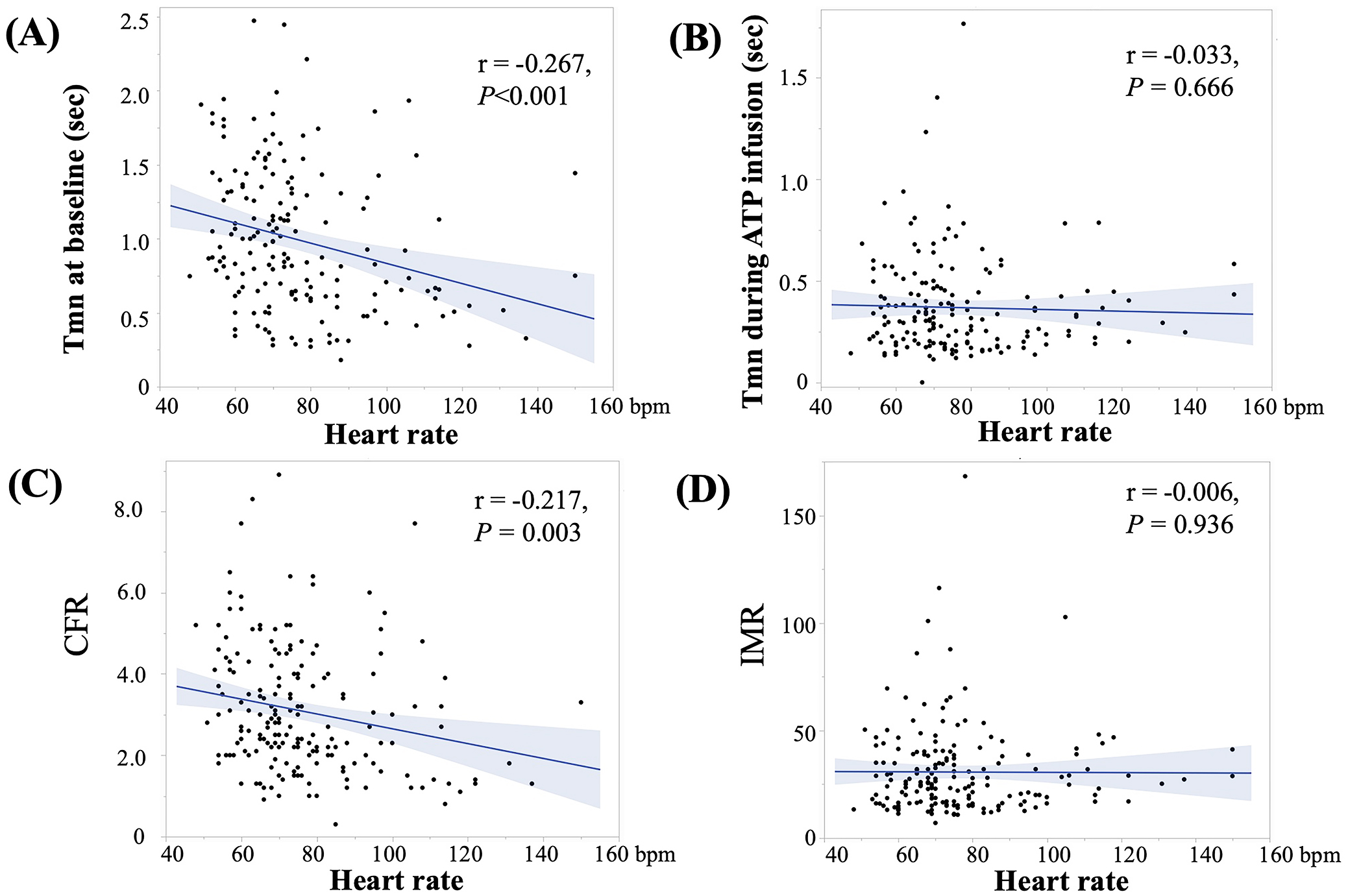

Fig. 4.

Fig. 4. Association between heart rate and Tmn at baseline (A), Tmn during ATP infusion (B), CFR (C), and IMR (D). Heart rate was negatively associated with Tmn at baseline (r = –0.267, p

Based on the subgroups of vessels, 21 (11%) were AF vessels, 29 (16%) were AF-SR vessels, and 136 (73%) were SR-2 vessels (Fig. 2 and Table 3). No significant differences were observed in LAD or RCA vessels, ACh dosage and additional EM administration, atherosclerosis presence, or coronary spasm frequency. A significant difference in the coronary spasm endotypes was observed among the three groups (p = 0.004). The heart rate at CMFT examination was significantly higher in the AF vessels group than in the other two groups (p

| SR-2 vessels | AF-SR vessels | AF vessels | p-value | ||

| No. (%) | 136 (73) | 29 (16) | 21 (11) | ||

| LAD/RCA | 87/49 | 18/11 | 11/10 | 0.594 | |

| Drugs provocative | |||||

| ACh L/M/H | 15/40/81 | 0/14/15 | 2/6/13 | 0.184 | |

| Additional use of EM (%) | 32 (24) | 5 (17) | 5 (24) | 0.779 | |

| Atherosclerosis (%) | 46 (34) | 4 (38) | 8 (38) | 0.869 | |

| VSA (%) | 75 (56) | 15 (58) | 10 (48) | 0.746 | |

| Endotype | |||||

| Focal/Diffuse/MVS/None/ND | 31/44/16/42/3 | 9/6/4/6/4 | 9/1/6/5/0 | 0.004 | |

| Presence of focal spasm (%) | 31 (23) | 9 (31) | 9 (43) | 0.125 | |

| Presence of diffuse spasm (%) | 44 (32) | 6 (21) | 1 (5) | 0.021 | |

| Heart rate at CMFT (bpm) | 71 | 76 | 110 | ||

| Pa during ATP infusion (mmHg) | 92 | 94 | 93 | 0.901 | |

| (Numbers of vessels we were able to measure) | (116) | (24) | (14) | ||

| Pd during ATP infusion (mmHg) | 88 | 88 | 88 | 0.998 | |

| (Numbers of vessels we were able to measure) | (116) | (24) | (14) | ||

| Tmn at baseline (seconds) | 1.06 | 0.83 | 0.78 | 0.012 | |

| (Numbers of vessels we were able to measure) | (124) | (27) | (19) | ||

| Tmn during ATP infusion (seconds) | 0.39 | 0.26 | 0.35 | 0.028 | |

| (Numbers of vessels we were able to measure) | (124) | (27) | (19) | ||

| Baseline Pd/Pa | 0.98 | 0.98 | 0.98 | 0.844 | |

| FFR | 0.94 | 0.93 | 0.94 | 0.746 | |

| CFR | 3.1 | 3.3 | 2.4 | 0.101 | |

| CFR of | 28 (21) | 4 (14) | 11 (52) | 0.002 | |

| IMR | 32.3 | 23.2 | 30.2 | 0.089 | |

| IMR of | 75 (55) | 8 (28) | 13 (62) | 0.016 | |

| CMD (%) | 81 (60) | 11 (38) | 14 (67) | 0.065 | |

Data are expressed as frequencies (percentages or numbers for some data). Abbreviations: ACh, acetylcholine; AF, atrial fibrillation; ATP, adenosine triphosphate; CAG, coronary angiography; CFR, coronary flow reserve; CMD, coronary microvascular dysfunction; CMFT, coronary microvascular function test; EM, ergonovine maleate; FFR, fractional flow reserve; IMR, index of microcirculatory resistance; LAD, left anterior descending coronary artery; L/M/H, low/moderate/high dose of acetylcholine; MVS, microvascular spasm; ND, not diagnosed; No., numbers; Pa, aortic pressure; Pd, distal pressure; RCA, right coronary artery; SPT, spasm provocation test; SR, sinus rhythm; Tmn, transit mean time; VSA, vasospastic angina.

Fig. 5.

Fig. 5. The values of (A) CFR and (B) IMR and the frequencies of (C) CFR of

This retrospective observational study investigated the clinical characteristics of patients with ANOCA who developed AF when first treated with SPT with ACh, followed by CMFT treatment. Approximately 25% of the patients developed PAF, but our study could not determine any clinical characteristics that would predispose patients to PAF. Additionally, we examined the effect of AF on subsequent CMFT. Our results revealed that patients with persistent AF demonstrated little effect on IMR despite a reduced CFR caused by increased coronary blood flow velocity at rest. Conversely, CFR and IMR may be affected in patients who developed PAF but recovered to SR, indicating an improved coronary microcirculation. Moreover, caution should be exercised when interpreting SPT results using ACh preceded by CMFT because AF complications may affect CMFT measurements.

PAF occurred in approximately 8%–17% of the patients in the SPT using the ACh group [10, 11]. This was more predominant in RCA provocations [10, 11]. This could be caused by the differences in the distribution of muscarinic receptors in the coronary arteries [22]. The present study revealed PAF in 23% of the patients receiving RCA and in 6% administered with LCA, indicating that PAF was more prevalent in the RCA provocation. Our study observed provocation was more common than previously reported [10, 11], which may be caused by the definition of AF used and because we included patients with PAF of short durations (such as those that were brief and quickly restored to SR). Additionally, the definition of low, moderate, and high doses of ACh differed from study to study, and these definitions must be cautiously interpreted, but it did not occur at higher ACh doses as reported by Sueda et al. [23]. Few studies have examined which patients are more likely to develop PAF during SPT with ACh [11]. Saito et al. [11] revealed that PAF is more likely to occur in patients with a PAF history and low body mass index (BMI). The present study revealed that patients with PAF reported no PAF history, and BMI did not differ between patients with or without PAF. The differences in the groups studied may explain the differences in patients with ANOCA. Saito et al. [11] conducted a univariate analysis revealing that men were less likely to have PAF, but the differences were not significant in the multivariate analysis. The present study indicated no such significant differences but observed a trend toward a higher PAF incidence in women. Further research is warranted to understand the sex-related differences in PAF complications during the SPT in a multicenter registry. The present study revealed a trend toward lower NT-proBNP and echocardiographic E/e’ in the PAF group, although the differences were not statistically significant. These results indicated that patients with less severity of cardiac organic abnormalities may be more prone to PAF caused by ACh provocation. Additionally, MB also tended to be more prevalent in the PAF group. An association between MB and PAF during the operation was observed in patients with hypertrophic cardiomyopathy [24]. More research is required to clarify the associations of NT-proBNP, E/e’, and MB with PAF during ACh provocation. Additionally, no significant association was observed between the occurrence of AF and coronary spasms, based on previous reports and our research results [10, 11]. Our study revealed that diffuse spasm was less common in AF vessels than in SR-1 vessels among the endotypes of coronary spasm. The number of cases in a multicenter registry or other methods to investigate this issue needs to be increased because of the small number of cases of AF vessels.

Several reports [12, 13, 14, 15] on the effects of AF on coronary microcirculation have reported that increased heart rate with AF results in a faster coronary blood flow velocity at baseline, causing a lower CFR. The present study revealed no difference in the maximal coronary blood flow velocity under ATP infusion although the resting coronary blood flow velocity increased with increased heart rate. Additionally, no significant changes were observed in blood pressure at baseline (data not shown) and during ATP infusion. Thus, an increased heart rate was the only significant factor responsible for a reduced CFR on logistic regression analysis. Our data were consistent with the results of previous studies [12, 13, 14, 15]. However, the results were somewhat different when the correlations between heart rate and Tmm at baseline and CFR were investigated separately for SR-1 and AF vessels. Significant negative correlations between heart rate and Tmm at baseline and CFR were observed in SR-1 vessels, whereas no significant correlations between them were found in AF vessels. Factors other than simply increased heart rate, such as irregular rhythm, may be involved in the shortening of the Tmm at baseline and the decrease in CFR although the small number of AF vessels may contribute to this result. In any case, the number of cases of AF vessels is small and should be increased in the future. Myocardial ischemia has been reported in animal models of AF complicated by significant coronary artery stenosis [13]. However, we considered that no apparent myocardial ischemia was induced during AF because the patients in our study demonstrated no significant stenosis in the coronary arteries and no significant decreases in intracoronary pressure (Pd) or FFR during ATP infusion. Increased heart rate (although not AF) increases CFR variability, indicating that it could be a reliable IMR indicator in such cases [25]. The present study revealed that IMR was unaffected by the heart rate and did not significantly differ between the AF and SR vessels. Many cases revealed that an increase in IMR does not always coincide with a decrease in CFR in clinical practice [16, 26]. Therefore, IMR alone cannot diagnose CMD, but it is recommended to refer to the IMR value when the CFR decreases during the AF duration.

The coronary microcirculation in vessels that recovered quickly from PAF to SR was interesting. CFR was preserved in these vessels and IMR appeared lower, although this was not statistically significant. Consequently, a lower rate of having the two components of CMD was observed with CFR of

Clinically, this study implies that SPT with ACh first followed by CMFT was effective in improving the rate of coronary spasm identification, but concomitant AF may affect the results of subsequent CMFT. IMR values are advisable to be referred for CMD diagnosis because CFR decreases with increased heart rate in cases of persistent AF. Diagnosing CMD may be difficult if PAF is restored to SR immediately after it occurs. In any case, the CMFT should be interpreted with caution when AF occurs. AF frequently occurs during ACh provocation of the RCA. Performing SPTs and CMFTs in the LCA and RCA may increase the diagnostic yield of VSA and CMD [27], but limiting them to the LCA could be a countermeasure [26].

This study has some limitations. First, this was a single-center, retrospective study and the number of patients with persistent AF or with AF restoring to SR was quite small. Additionally, many cases underwent CMFT in only one coronary artery at the attending physician’s discretion. The application of these results is unclear internationally. Second, recording during CMFT measurements with intracoronary pressure and Tmn data missing in some cases was insufficient. Third, none of the patients in this study reported a PAF history, as far as we could identify from their medical records and interviews. However, the method of confirmation may not be sufficient because Holter ECGs were not performed frequently enough. Fourth, LAD and RCA were analyzed together because the number of AF cases was not large in this analysis. However, RCAs demonstrated generally higher Tmn and higher IMR than LADs [28]. Our study revealed no differences in the frequency of LAD and RCA measurements between the AF and SR groups, which did not influence the present results, but analyzing LAD and RCA separately for each vessel as they should seem correct. This is another issue that should be considered with an increased number of cases in a multicenter registry or other studies. Finally, the data were obtained from a cross-sectional study, and the CMFT data evolution in patients with AF was not observed. A method is used to measure CMFT after electrical cardioversion or administration of antiarrhythmic drugs by restoring AF to SR, but restoration of AF to SR is only performed after completing the examination due to the effects of these procedures and drugs on coronary microcirculation and because of time constraints.

We focused on AF which occurs when SPT with ACh is utilized for chest pain screening in patients with ANOCA in the present study. PAF occurred in 25% of the patients in our protocol. Our study did not reveal any particular clinical features in the background of patients that would predispose these patients to PAF development. We then examined whether AF would affect the results of the subsequent CMFT and the results indicated that CFR decreased with increasing heart rate in cases of persistent AF, but IMR was not related to heart rate. CMD with reference to IMR is recommended to be evaluated when AF is persistent and CFR declines. Conversely, CFR was preserved and IMR was low in vessels where AF was quickly restored to SR. This indicates retained coronary microcirculation. Subsequent interpretation of CMFTs should be done cautiously when AF occurs during SPT with ACh, whether persistent or not. The results of this study warrant validation in a multicenter registry.

No AI was used in the preparation of this paper.

ACh, acetylcholine; AF, atrial fibrillation; ANOCA, angina with non-obstructive coronary artery disease; ATP, adenosine triphosphate; CAD, coronary artery disease; CAG, coronary angiography; CFR, coronary flow reserve; CKD, chronic kidney disease; CMD, coronary microvascular dysfunction; CMF, coronary microvascular function; CMFT, coronary microvascular function test; DM, diabetes mellitus; eGFR, estimated glomerular filtration ratio; EM, methylergometrine maleate; FFR, fractional flow reserve; H, high dose; IMR, index of microcirculatory resistance; L, low dose; LAD, left anterior descending coronary artery; LCA, left coronary artery; LVEF, left ventricular ejection fraction; LVMI, left ventricular mass index; M, moderate dose; MB, myocardial bridging; MVS, microvascular spasm; n, number; ND, not diagnosed; NTG, nitroglycerin; No., number; NT-proBNP, N Terminal-pro brain natriuretic peptide; Pa, aortic pressure; PAF, paroxysmal atrial fibrillation; PCI, percutaneous coronary intervention; Pd, distal pressure; RAS, renin–angiotensin system, RCA, right coronary artery; SPT, spasm provocation test; SR, sinus rhythm; Tmn, transit mean time; UCG, ultrasound cardiography; VSA, vasospastic angina.

Data and materials inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

HT, CO, YH and SN were involved in the patient enrolment and the collection of clinical data. HT drafted the manuscript and CO, YH and SN checked the manuscript before submission. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript. All authors have participated sufficiently in the work and agreed to be accountable for all aspects of the work.

This study was conducted in accordance with the guidelines of the Declaration of Helsinki and was approved by the Institutional Review Board of JR Hiroshima Hospital (protocol code: 2024-16; date of approval: 15 August 2024). Informed consent was obtained from all the patients who underwent the SPT and CMFT before the procedure. The opt-out method was adopted because of the retrospective study design.

The authors thank the staff of the cardiac catheterization room and the nursing staff of the Cardiovascular Medicine Ward at JR Hiroshima Hospital.

This research received no external funding.

The authors declare no conflict of interest. Hiroki Teragawa is serving as Guest Editor of this journal. We declare that Hiroki Teragawa had no involvement in the peer review of this article and has no access to information regarding its peer review. Full responsibility for the editorial process for this article was delegated to Francesco Pelliccia.

References

Publisher’s Note: IMR Press stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.