1 Department of Physiology and Pharmacology, University of Western Ontario, London, ON N6G 2X6, Canada

§Retired.

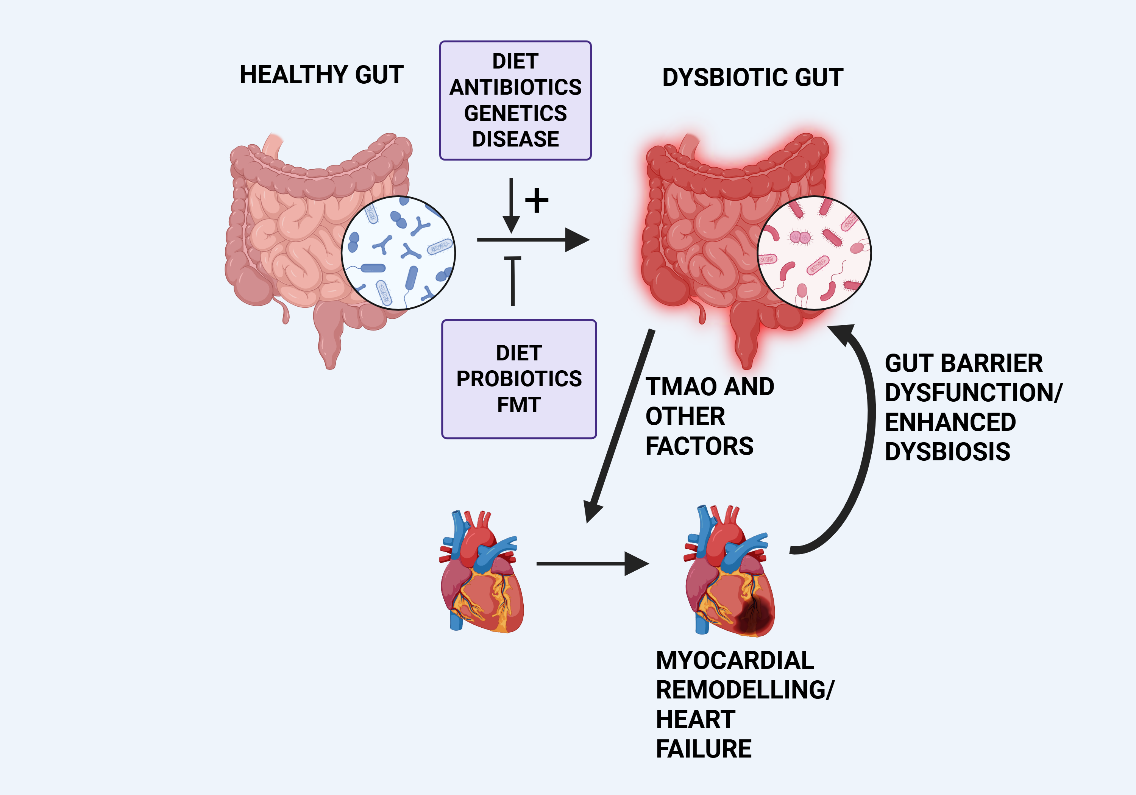

Gastrointestinal health is largely regulated by the nature of the bacterial and viral content inhabiting the intestinal tract, generally referred to as the gut microbiome [1]. The nature of the gut microbiome can markedly affect the disease process and an imbalance in these microorganisms, referred to as dysbiosis, can contribute to various diseases. Dysbiosis can occur as a consequence of numerous factors such as genetics, dietary and lifestyle habits, diseases, pharmacological agents such as antibiotics, as well as others [2]. Dysbiosis can negatively affect the function of numerous distal organs including the heart via a process generally referred to as the gut-heart axis. This editorial discusses the gut-heart axis and how dysbiosis can affect heart failure. Potential therapeutic approaches towards mitigating heart failure via manipulation of the gut microbiome and dysbiosis are reviewed.

The heart can be affected by gut dysbiosis. There is currently extensive evidence that heart disease can be markedly affected by disruption of the gut microflora. Therefore, modulation of the gut microbiome can represent an attractive and effective therapeutic approach for the treatment of various cardiovascular pathologies. Among these is heart failure, which occurs via enhanced myocardial remodelling and hypertrophy which can be augmented by the gut-heart axis [3, 4, 5].

The mechanisms underlying the gut-heart axis have been well studied and with

substantial evidence documented in both animal as well as clinical studies [3, 4, 5, 6].

Altering the gut microbiota to a more favourable microorganism profile results in

improved cardiovascular status. Dysbiosis is associated with enhanced myocardial

oxidative stress, proinflammatory responses, as well as alterations in the

myocardial epigenetics profile, all of which contribute to the onset of heart

failure [7, 8, 9, 10]. These negative effects can occur via both direct and

indirect mechanisms. Dysbiosis is associated with intestinal dysfunction

including enhanced inflammation and intestinal wall permeability resulting in the

release of pathogenic toxins into the bloodstream which directly exert

cardiotoxic effects as has been shown clinically in heart failure patients [11, 12]. The second major mechanism for cardiac impairment associated with dysbiosis

involves the production of microorganism-derived toxic metabolites released into

the circulation. One of the most widely studied of these metabolites is

trimethylamine N-oxide (TMAO), a dietary choline-derived metabolite which

produces a plethora of effects including increased cardiac fibrosis partially via

activation of the NLRP3 inflammasome, increased inflammation, endothelial

dysfunction, and progression of atherosclerosis [13] as well as directly

promoting cardiac hypertrophy [14]. The latter effects appear to be dependent on

multifaceted mechanisms including elevations in intracellular calcium

concentrations and TGF-

Fig. 1.

Fig. 1.

Simplified diagram illustrating dysbiosis-induced cardiac remodelling and the reciprocal nature of the gut-heart axis. Various factors, indicated in the upper box, can promote gut dysbiosis resulting in the release of factors promoting myocardial remodelling and heart failure, as discussed in the text. The remodelled heart can further promote dysbiosis via various mechanisms, principally via gut barrier dysfunction. Potential reduction of dysbiosis can result from dietary intervention, administration of probiotics or by Fecal Microbiota Transplantation (FMT) as indicated in the lower box. TMAO, trimethylamine N-oxide. Created with BioRender.com.

The phenomenon of dysbiosis affecting cardiac function and contributing to heart failure has led to a number of potential therapeutic interventions which could result in effective adjunctive treatments for heart disease including heart failure. One such approach is the administration of probiotics which would enhance the composition of the gut microbiota with so-called beneficial microorganisms thus attenuating the heart failure process. Such a benefit has been demonstrated in a number of experimental animal models including rats subjected to 30 minutes of ischemia followed by 2 hours of reperfusion in which administering the probiotic supplement Goodbelly® (containing L. plantarum and Bifidobacterium lactis) for 14 days prior to surgery significantly reduced infarct size in these animals [22]. The author’s laboratory demonstrated that the administration of the probiotic Lactobacillus rhamnosus GR-1 reduced myocardial hypertrophy and improved left ventricular function in rats subjected to 6 weeks of coronary artery ligation [23]. Administering a synbiotic (combination of probiotic and prebiotic) attenuated myocardial structural changes and hypertrophy in a porcine model of the metabolic syndrome [24]. In a small clinical study of heart failure patients (NYHA Class II and III), administration of the probiotic Saccharomyces boulardii resulted in an improvement in various parameters including a significant increase in left ventricular ejection fraction [25], although a recent clinical evaluation of this probiotic in 46 heart failure patients revealed no improvement following three-month of treatment [26]. Recently, a multistrain probiotic was shown to reduce sarcopenia and improve physical capacity in heart failure patients [27]. The composition of this multistrain probiotic can be found in reference [27].

Fecal microbiota transplantation offers another approach towards improving the gut microbiome and potentially mitigating myocardial remodelling. Fecal transplantation, first recorded hundreds of years ago, has been shown to favourably influence various diseases [28] and was demonstrated to reduce the severity of heart failure in a number of experimental animal models [29, 30].

Substantial evidence suggests that modifying the gut microbiome by reducing dysbiosis contributes not only to gastrointestinal health but also to ameliorating various pathologies including cardiovascular diseases such as heart failure. Interest in the gut-heart axis, particularly within the past ten years, has been impressive based on the number of publications cited in PubMed. Experimental animal studies strongly support the concept of the gut-heart axis and its contribution to cardiac pathology due to dysbiosis. This is derived to a large degree from cardiac benefits seen through the administration of probiotics as well as improvement in cardiac parameters in experimental heart failure following fecal transplantation. Application of this concept to the clinical scenario is important particularly in view of the limited data currently available from studies derived from small patient populations. Thus, clinical evaluation of probiotics in heart failure patients in large scale clinical studies is warranted. Addition of probiotics to standard heart failure therapy or the use of other approaches to reduce gut dysbiosis would be a reasonable initial approach in order to ascertain clinical efficacy for the treatment of heart failure particularly in view of the discordant clinical results, as noted in the previous section. Nevertheless, clinical evaluation presents complex challenges when compared to animal studies, with factors such as co-morbidities, patient demographics and many other factors coming into play. Yet these clinical trials, particularly with appropriate patient recruitment, are critical to clearly assess the efficacy of reducing dysbiosis for the treatment of heart failure.

The author is responsible for the entire preparation of this manuscript.

Not applicable.

Not applicable.

Research from the author’s laboratory cited in this editorial was funded by the Canadian Institutes of Health Research.

The author declares no conflict of interest. Morris Karmazyn is serving as Guest Editor of this journal. We declare that Morris Karmazyn had no involvement in the peer review of this article and has no access to information regarding its peer review. Full responsibility for the editorial process for this article was delegated to Karol E. Watson.

References

Publisher’s Note: IMR Press stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.