1 Department of Emergency, Beijing Anzhen Hospital, Capital Medical University, 100029 Beijing, China

2 Department of Clinical Medicine, Capital Medical University, 100029 Beijing, China

†These authors contributed equally.

Abstract

Previous studies on acute myocardial infarction (AMI) complicated by atrial fibrillation (AF) have mainly focused on anatomy or underlying disease state, and its prognostic predictors have not been fully explored. Therefore, there is a need for an effective prognosis model for patients with AMI-AF.

We retrospectively selected 126 patients with acute myocardial infarction complicated with AF hospitalized in Beijing Anzhen Hospital from January 2020 to December 2024 as the case group, and 1719 patients without AF as the control group. The clinical characteristics and laboratory test results of the two groups were compared to determine independent risk factors for AF in patients with acute myocardial infarction. The predictive performance of the model was evaluated by plotting Receiver Operating Characteristic (ROC) for each independent predictor. For the combined model, we used R software to build pattern plots, calibration plots, and Decision Curve Analysis (DCA) based on a multivariate logistic regression model.

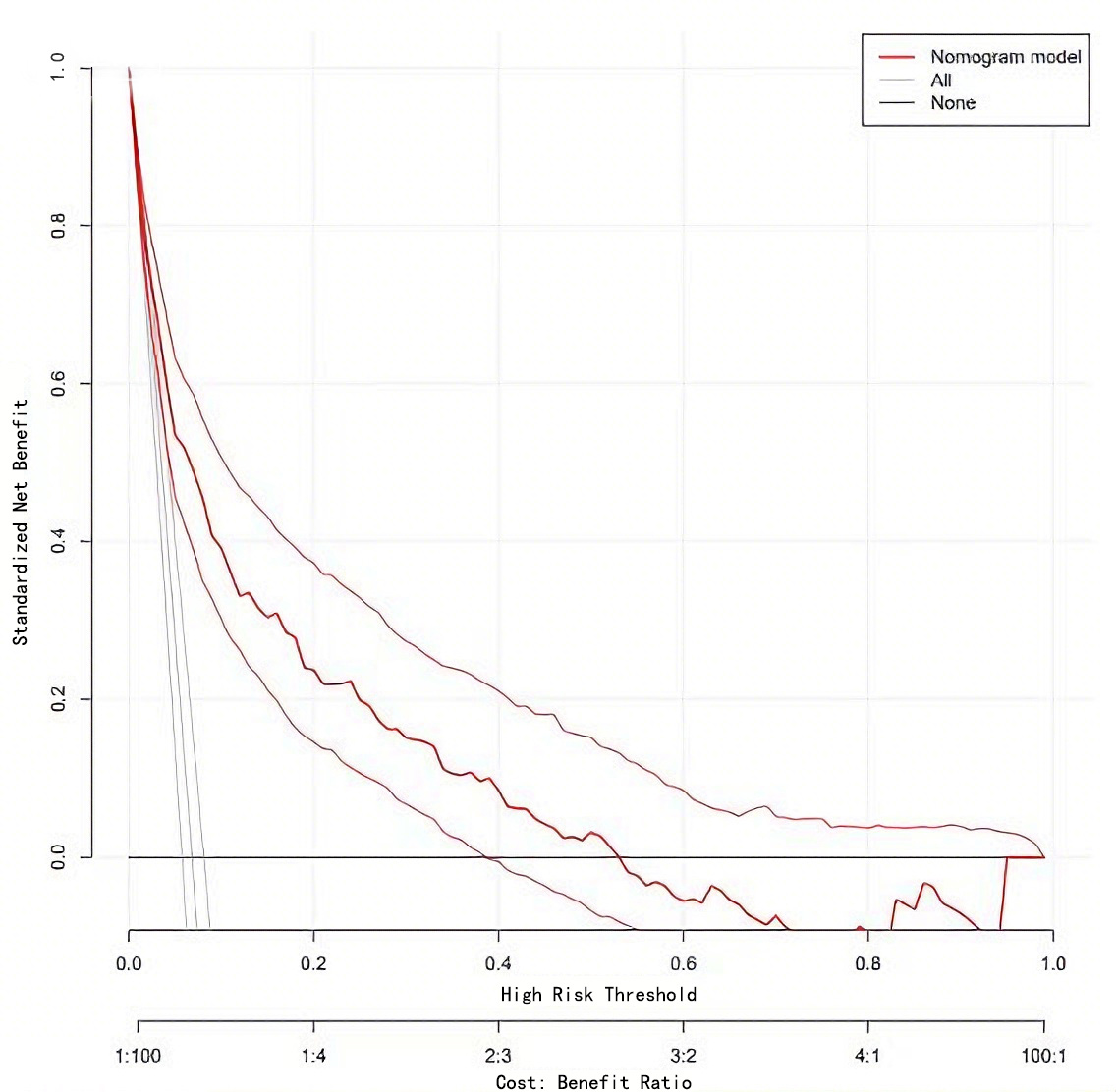

Multivariate Logistic regression analysis showed that older age (Odds Ratio (OR) = 1.067, 95% CI: 1.044–1.092), longer hospitalization days (OR = 1.039, 95% CI: 1.013–1.066). The AUCs for age, hospitalization days, history of coronary heart disease, heart rate, International Normalized Ratio (INR), Hemoglobin, and mean platelet volume were 0.721, 0.663, 0.577, 0.614, 0.688, 0.438, and 0.607. The AUC of nomogram model for predicting AF in AMI patients was 0.833 (95% CI: 0.796–0.870, p < 0.001), the sensitivity was 0.817, and the specificity was 0.726. The nomogram model indicated a clinical net benefit when the predicted risk threshold exceeded 0.06.

Multivariable prediction model has good prediction effect. The variables in this nomogram model are easily obtained in clinical practice and can provide reference for individualized prediction of AF in AMI patients.

Keywords

- acute myocardial infarction

- atrial fibrillation

- risk factors

- prediction model

Acute myocardial infarction (AMI) is a critical cardiovascular emergency caused by acute coronary artery occlusion leading to myocardial ischemic necrosis. Its morbidity and mortality remain elevated globally [1]. Although advances in percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI) and medical treatment have significantly improved the short-term prognosis of AMI, its complications (such as arrhythmia and heart failure) remain a major challenge affecting patient’s quality of life and long-term prognosis [2]. Among them, atrial fibrillation (AF) is a common complication of AMI, with an incidence rate of about 10% to 20%, and is closely related to patient mortality, stroke risk and cardiac function deterioration [3]. Studies have shown that the in-hospital mortality rate among patients with AMI and AF is 2–3 times higher than that of patients with AMI alone, and the long-term prognosis is worse [4].

The high incidence of AF in AMI patients is closely related to the complex pathophysiological mechanisms. Myocardial injury and ventricular remodeling after AMI disrupt atrial electrophysiology and promote AF [5]. Systemic inflammation, oxidative stress, and neurohormonal activation further contribute to atrial fibrosis and electrical instability [6]. In turn, AF exacerbates myocardial ischemia, reduces cardiac output, and increases thromboembolic risk [7]. Although previous studies have identified traditional risk factors such as age, left ventricular dysfunction, hypertension, and diabetes, these indicators rely mostly on anatomy or underlying disease status, and may not fully reflect the dynamic pathological process of AF in AMI patients [8]. Based on this, this study fully integrates hematological indicators and parameters such as cardiac ultrasound, and through large-scale clinical data analysis which aims to reveal the risk factors of AF in AMI patients and establish a risk prediction model, providing evidence-based basis for early identification of high-risk populations and the development of personalized intervention strategies.

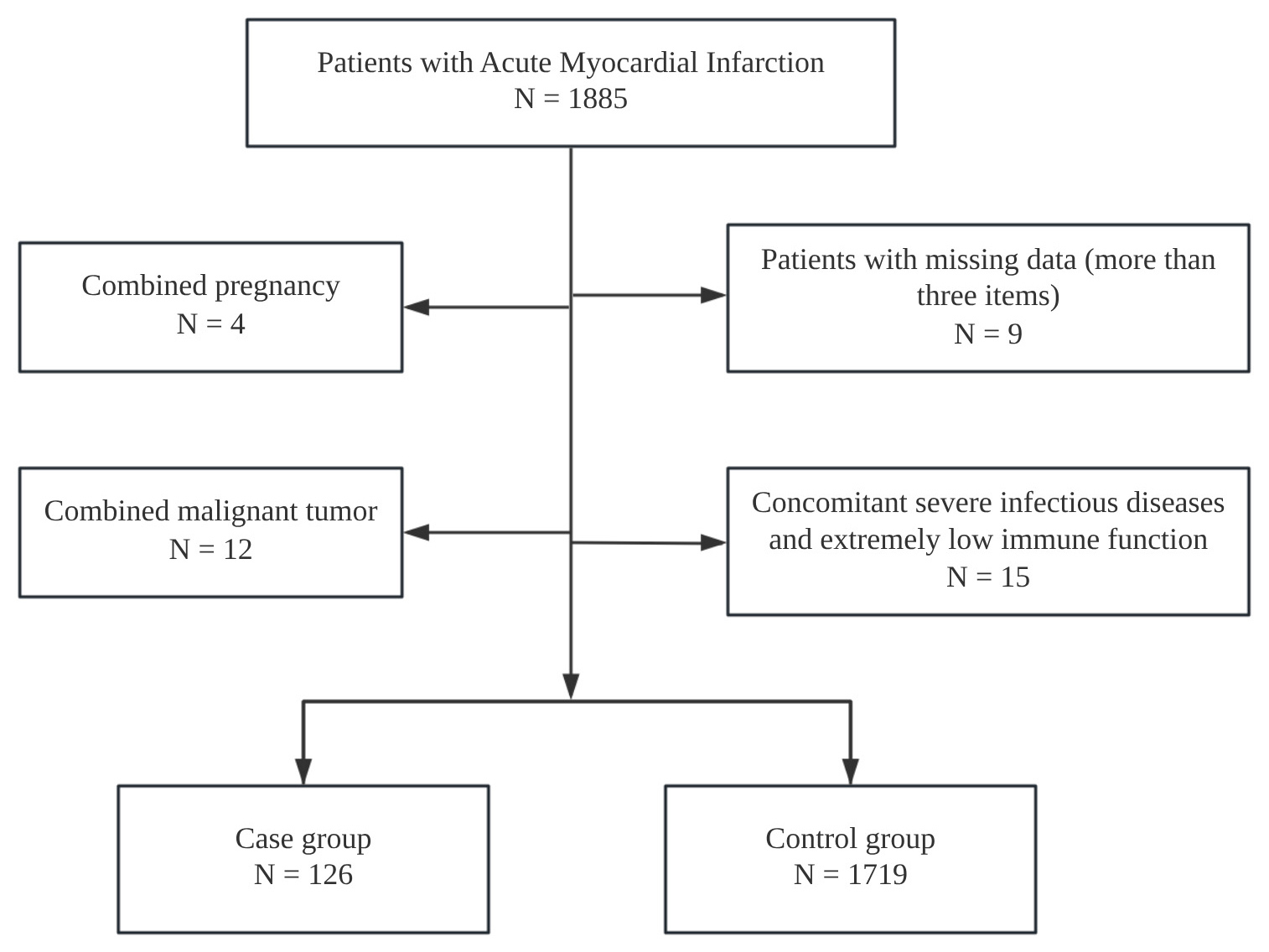

We selected 126 patients hospitalized with AMI complicated by AF in Beijing Anzhen Hospital Affiliated to Capital Medical University from January 2020 to December 2024 as the case group, and 1719 in patients with AMI without AF as the control group. The inclusion criteria were: age more than 18 years; meet the diagnostic criteria of AMI [9]; meet the diagnostic criteria of AF [10]. Exclusion criteria are: incomplete clinical data such as vital signs; pregnancy; concomitant severe infectious diseases and extremely low immune function. In total, 1845 participants were included in the final analysis (Fig. 1). This study was reviewed by the Ethics Committee of Beijing Anzhen Hospital Affiliated to Capital Medical University (Approval No. 2024-05).

Fig. 1.

Fig. 1.

A consort type diagram of whole patients with acute myocardial infarction.

This was a retrospective case-control study, and the sample size was estimated based on the “Events per Variable” principle. Based on previous research recommendations, at least 10 positive events are required for each predictor variable. This study ultimately included 7 independent risk factors, so at least 70 patients with AMI complicated by AF were needed. 126 cases were actually included, and there were sufficient concurrent events to meet the model construction needs.

All members of the investigation team have been trained on unified standards. Trained staff explained the purpose, implementation process, and benefits of this study to eligible research subjects within 24 hours of admission, and obtained their consent. Trained research staff abstracted data from the hospital’s electronic medical records and collected information about patients who agreed to participate in the study according to the designed data questionnaire. All information was checked by two people and entered into an Excel sheet. Atrial fibrillation was ascertained by 12-lead Electrocardiogram (ECG) or continuous telemetry interpreted by board-certified cardiologists during the index hospitalization, from emergency department triage to discharge. AF status therefore reflects AF present at admission or documented at any time before discharge. Predictors were abstracted at or near admission (Emergency Department (ED) triage/first-day vitals and initial laboratory tests, generally within 24 hours). For patients with AF on admission, the nearest available pre-AF measurements were used when possible.

Detailed medical history was collected for all patients (diagnosis complied with

relevant guideline standards). Clinical characteristics collected included: Age,

gender, body mass index (BMI), length of stay; Medical history: hypertension

[11], diabetes [12], coronary heart disease [13], old myocardial infarction [14],

history of PCI, coronary artery bypass grafting (CABG), stroke [15], peripheral

vascular disease [16], history of smoking and alcohol consumption; Clinical

complications included: Killip

The measurement data were subjected to Shapiro-Wilk normality test. The

measurement data conforming to the normal distribution were expressed as mean

Univariate analysis revealed significant differences between the case and

control groups for the following variables: age, length of stay, hypertension,

diabetes, coronary heart disease, old myocardial infarction, stroke, peripheral

vascular disease, Killip

| Characteristic | Case Group (n = 126) | Control Group (n = 1719) | p-value | ||

| Clinical characteristics | |||||

| Age, mean |

68.60 |

59.35 |

10.410 | ||

| Male, n (%) | 96 (76.19) | 1383 (80.45) | 1.087 | 0.297 | |

| Female, n (%) | 30 (23.81) | 336 (19.55) | 1.087 | 0.297 | |

| BMI, mean |

25.35 |

25.99 |

1.897 | 0.058 | |

| Hospitalization days, Median (IQR) | 8 (5, 12) | 5 (3, 8) | –3.695 | ||

| Medical history, n (%) | |||||

| Hypertension | 92 (73.02) | 1013 (58.93) | 9.120 | 0.003 | |

| Diabetes | 63 (50.00) | 662 (38.51) | 6.023 | 0.014 | |

| Coronary heart disease | 81 (64.29) | 841 (48.92) | 10.476 | 0.001 | |

| Old myocardial infarction | 23 (18.25) | 186 (10.82) | 5.740 | 0.017 | |

| PCI surgery | 32 (25.40) | 313 (18.21) | 3.532 | 0.060 | |

| CABG surgery | 9 (7.14) | 69 (4.01) | 2.118 | 0.146 | |

| Stroke | 24 (19.05) | 193 (11.23) | 6.185 | 0.013 | |

| Peripheral vascular disease | 6 (4.76) | 28 (1.63) | 4.756 | 0.029 | |

| Smoking status | 39 (30.95) | 649 (37.75) | 2.041 | 0.153 | |

| Alcohol consumption | 20 (15.87) | 351 (20.42) | 1.240 | 0.265 | |

| Clinical complication, n (%) | |||||

| Killip |

18 (14.29) | 77 (4.48) | 21.151 | ||

| Heart failure | 28 (22.22) | 115 (6.69) | 37.469 | ||

| Lung infection | 25 (19.84) | 75 (4.36) | 51.887 | ||

| Renal dysfunction | 30 (23.81) | 143 (8.32) | 31.354 | ||

| Hepatic dysfunction | 13 (10.32) | 125 (7.27) | 1.164 | 0.281 | |

| Hypoproteinemia | 29 (23.02) | 137 (7.97) | 30.647 | ||

| Hyperuricemia | 12 (9.52) | 73 (4.25) | 6.287 | 0.012 | |

| Vital signs | |||||

| Systolic blood pressure, mean |

125 |

126 |

–0.568 | 0.570 | |

| Diastolic blood pressure, mean |

74 |

76 |

–1.806 | 0.071 | |

| Heart rate, Median (IQR) | 84 (78, 90) | 79 (73, 85) | –4.002 | ||

| Cardiac ultrasound | |||||

| Ejection fraction, Median (IQR), % | 46 (36, 56) | 55 (45, 61) | 5.931 | ||

| Pericardial effusion, n (%) | 15 (11.90) | 103 (5.99) | 5.904 | 0.015 | |

| Aortic valve regurgitation, n (%) | 67 (53.17) | 513 (29.84) | 28.577 | ||

| Laboratory parameters | |||||

| TG, Median (IQR), mmol/L | 1.24 (0.89, 1.59) | 1.51 (1.11, 2.15) | 7.051 | ||

| TC, Median (IQR), mmol/L | 3.59 (2.98, 4.27) | 4.08 (3.40, 4.85) | 4.160 | ||

| HDL-C, Median (IQR), mmol/L | 1.04 (0.87, 1.21) | 0.99 (0.84, 1.17) | –1.360 | 0.174 | |

| LDL-C, Median (IQR), mmol/L | 1.95 (1.49, 2.70) | 2.35 (1.75, 3.06) | 3.588 | ||

| APTT, Median (IQR), Sec | 32.65 (29.33, 38.45) | 31.00 (28.80, 34.00) | –1.474 | 0.141 | |

| INR, Median (IQR) | 1.07 (1.02, 1.21) | 1.02 (0.97, 1.07) | –4.907 | ||

| FDP, Median (IQR), ug/mL | 1.40 (0.78, 4.39) | 0.90 (0.60, 1.70) | –2.013 | 0.044 | |

| DD, Median (IQR), µg/L | 161.00 (82.25, 567.25) | 108.00 (63.00, 208.00) | –1.787 | 0.074 | |

| WBC, Median (IQR), |

7.71 (6.18, 10.53) | 7.41 (6.90, 34.00) | –1.972 | 0.051 | |

| HB, Median (IQR), g/L | 133 (117, 151) | 140 (126, 151) | 2.440 | 0.016 | |

| PLT, Median (IQR), |

196 (162, 241) | 223 (185, 267) | 4.007 | ||

| MPV, mean |

10.25 |

9.85 |

–4.060 | ||

| NEUT%, mean |

74.91 |

70.43 |

–4.819 | ||

| NEUT, Median (IQR), |

5.83 (4.19, 8.25) | 5.12 (3.96, 6.89) | –3.756 | ||

BMI, body mass index; PCI, percutaneous coronary intervention; CABG, coronary artery bypass grafting; TG, triglyceride; TC, total cholesterol; HDL-C, high-density lipoprotein cholesterol; LDL-C, low-density lipoprotein cholesterol; APTT, Activated Partial Thromboplastin Time; INR, International Normalized Ratio; FDP, fibrin degradation products; DD, D-dimer; WBC, white blood cells; HB, Hemoglobin; PLT, platelets; MPV, Mean Platelet Volume; NEUT%, Neutrophils Percentage; NEUT, Neutrophils Count.

Whether AMI patients had AF was used as the dependent variable, and items with

statistically significant differences within single factors were used as the

independent variable. The difference variables screened by the above

single-factor analysis were included in the Logistic model for multivariate

analysis. The results showed that older age, longer hospital stay, previous

history of coronary heart disease, faster heart rate, higher INR level, lower Hb

level, and larger mean platelet volume were all independent risk factors for AF

in AMI patients (p

| Characteristic | b | Sb | Wald |

OR (95% CI) | p-value | |

| Clinical characteristics | ||||||

| Age, years | 0.065 | 0.011 | 33.008 | 1.067 (1.044, 1.092) | ||

| Hospitalization days | 0.038 | 0.013 | 8.529 | 1.039 (1.013, 1.066) | 0.003 | |

| Medical history | ||||||

| Hypertension | 0.417 | 0.236 | 3.110 | 1.517 (0.955, 2.41) | 0.078 | |

| Diabetes | 0.317 | 0.213 | 2.220 | 1.373 (0.905, 2.084) | 0.136 | |

| Coronary heart disease | 0.471 | 0.219 | 4.620 | 1.602 (1.042, 2.462) | 0.032 | |

| Old myocardial infarction | –0.187 | 0.304 | 0.379 | 0.829 (0.457, 1.506) | 0.538 | |

| Stroke | 0.043 | 0.268 | 0.025 | 1.044 (0.617, 1.766) | 0.873 | |

| Peripheral vascular disease | –0.273 | 0.651 | 0.176 | 0.761 (0.212, 2.727) | 0.675 | |

| Clinical complication | ||||||

| Killip |

0.063 | 0.372 | 0.029 | 1.065 (0.514, 2.21) | 0.865 | |

| Heart failure | 0.538 | 0.300 | 3.212 | 1.712 (0.951, 3.081) | 0.073 | |

| Lung infection | 0.436 | 0.358 | 1.487 | 1.547 (0.767, 3.118) | 0.223 | |

| Renal dysfunction | 0.190 | 0.312 | 0.371 | 1.209 (0.656, 2.228) | 0.542 | |

| Hypoproteinemia | 0.397 | 0.309 | 1.651 | 1.487 (0.812, 2.724) | 0.199 | |

| Hyperuricemia | 0.577 | 0.392 | 2.166 | 1.781 (0.826, 3.842) | 0.141 | |

| Vital signs | ||||||

| Diastolic blood pressure | 0.005 | 0.010 | 0.301 | 1.005 (0.987, 1.024) | 0.583 | |

| Heart rate | 0.021 | 0.007 | 8.218 | 1.021 (1.007, 1.035) | 0.004 | |

| Cardiac ultrasound | ||||||

| Ejection fraction, % | –0.014 | 0.009 | 2.354 | 0.986 (0.968, 1.004) | 0.125 | |

| Pericardial effusion | –0.172 | 0.357 | 0.232 | 0.842 (0.418, 1.695) | 0.630 | |

| Aortic valve regurgitation | 0.344 | 0.214 | 2.574 | 1.411 (0.927, 2.147) | 0.109 | |

| Laboratory parameters | ||||||

| TG, mmol/L | –0.252 | 0.178 | 2.007 | 0.777 (0.549, 1.101) | 0.157 | |

| TC, mmol/L | –0.101 | 0.369 | 0.074 | 0.904 (0.439, 1.862) | 0.785 | |

| LDL-C, mmol/L | –0.062 | 0.410 | 0.023 | 0.94 (0.421, 2.101) | 0.881 | |

| INR | 0.716 | 0.312 | 5.275 | 2.047 (1.111, 3.773) | 0.022 | |

| FDP, ug/mL | –0.026 | 0.014 | 3.373 | 0.975 (0.948, 1.002) | 0.066 | |

| HB, g/L | 0.017 | 0.005 | 10.375 | 1.018 (1.007, 1.028) | 0.001 | |

| PLT, |

–0.001 | 0.002 | 0.384 | 0.999 (0.996, 1.002) | 0.535 | |

| MPV, fL | 0.205 | 0.100 | 4.185 | 1.227 (1.009, 1.493) | 0.041 | |

| NEUT%, % | 0.022 | 0.015 | 2.260 | 1.022 (0.993, 1.052) | 0.133 | |

| NEUT, |

0.012 | 0.046 | 0.075 | 1.013 (0.926, 1.107) | 0.785 | |

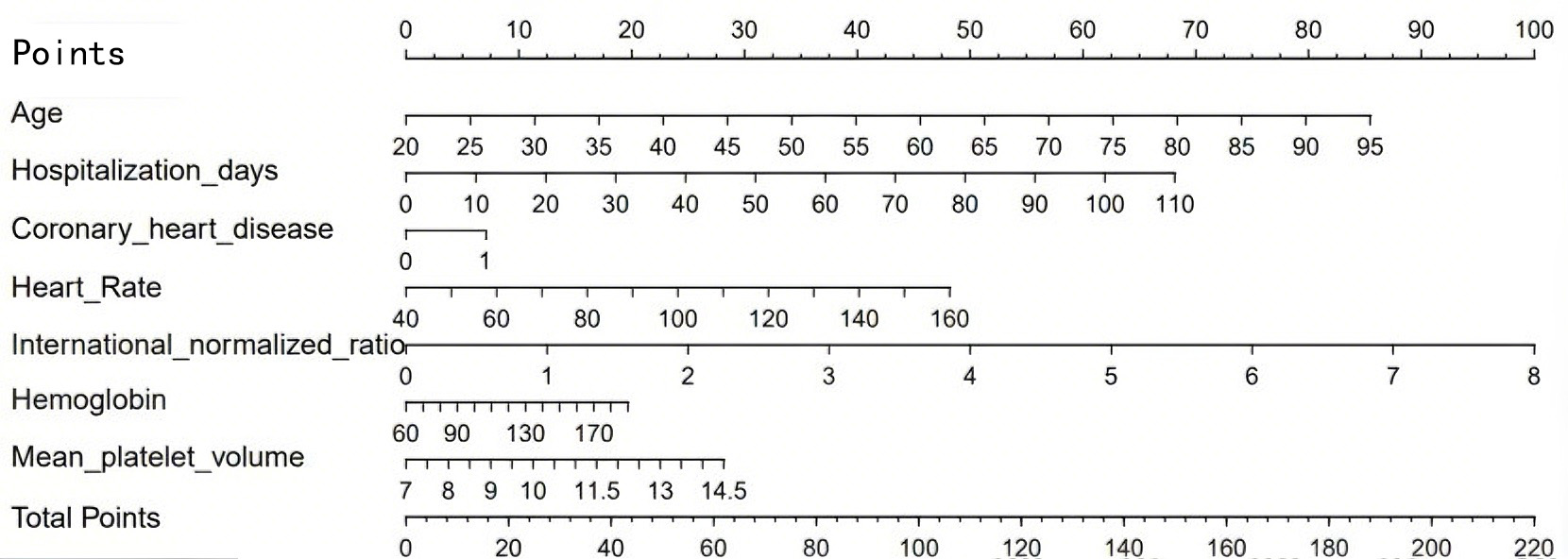

We constructed a nomogram using the independent predictors identified by multivariable logistic regression: age, length of stay, history of coronary heart disease, heart rate, INR, Hb, and mean platelet volume (MPV). The scale (0–100 points) at the top of the graph can measure the score of each variable under the corresponding circumstances. Add the scores of all patient variables corresponding to the scale to form the total score, and correspond to the total score scale and incidence probability at the bottom of the figure, to obtain the predicted risk of AF in patients with AMI (Fig. 2).

Fig. 2.

Fig. 2.

A nomogram prediction model for AF in AMI patients. AF, atrial fibrillation; AMI, acute myocardial infarction.

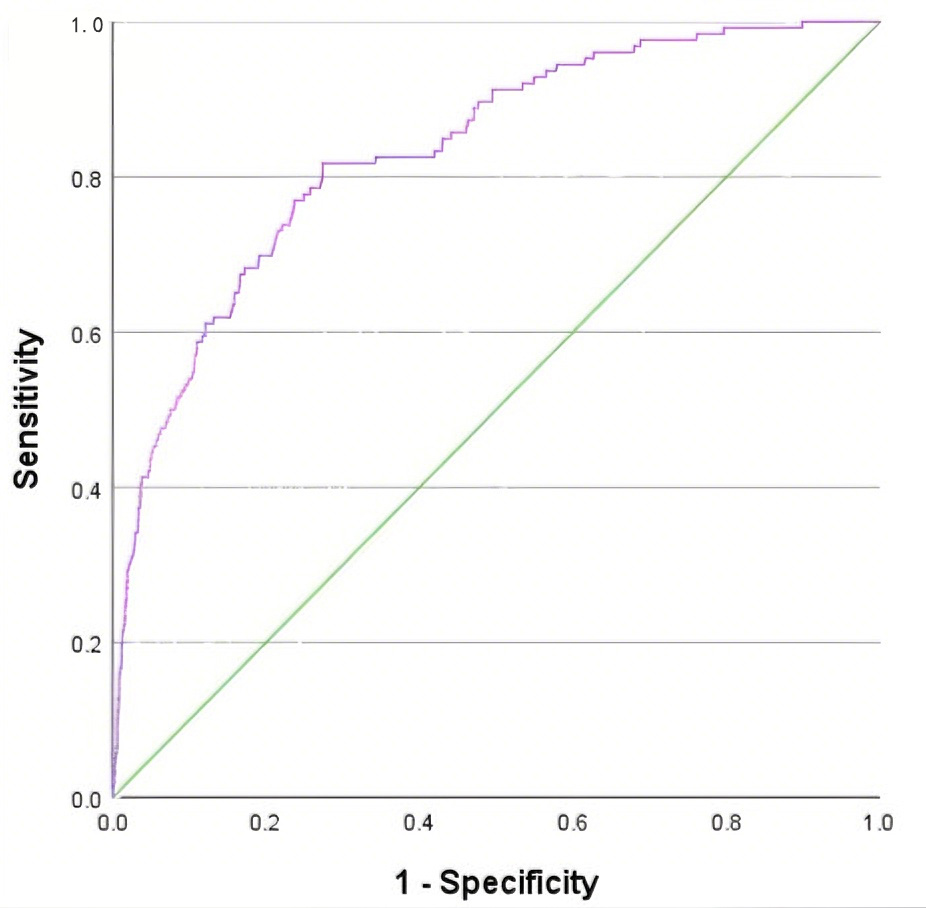

The predictive effect of nomogram model was analyzed. The results showed that

“AUCs” of variables age, hospitalization days, coronary heart disease history,

heart rate, INR, Hb, and MPV were 0.721, 0.663, 0.577, 0.614, 0.688, 0.438, and

0.607. The area under the ROC curve AUC of nomogram model for predicting AF in

AMI patients was 0.833 (95% CI: 0.796–0.870, p

Fig. 3.

Fig. 3.

ROC curve of risk prediction model for AF in AMI patients.

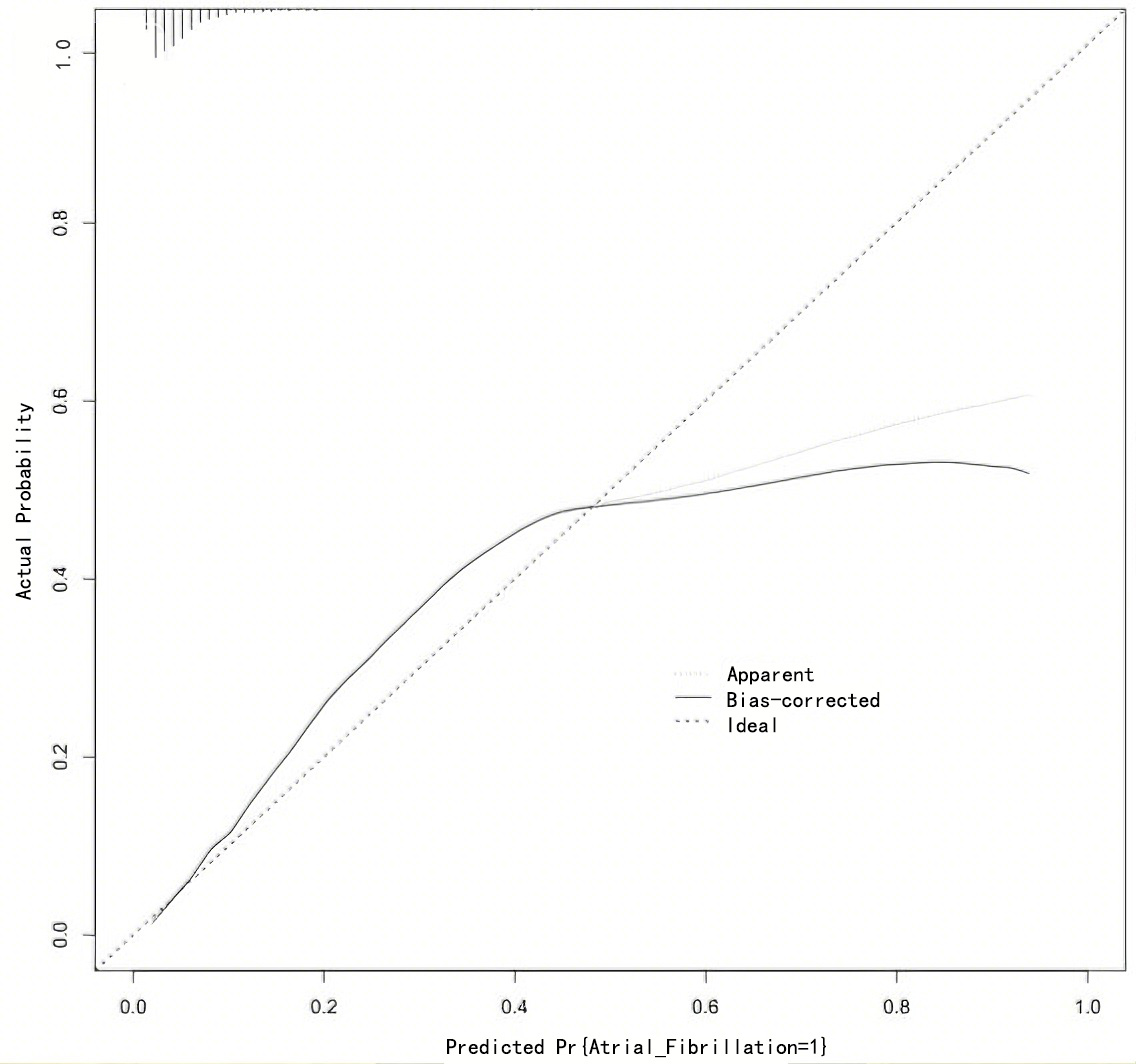

On the basis of the above, the nomogram model was calibrated and a calibration curve was drawn. The results showed that the predicted values were in good agreement with the measured values (Fig. 4). At the same time, the DCA curve was drawn to calculate the clinical net benefit. DCA indicated that the nomogram model provided a clinical net benefit when the predicted risk threshold for AF exceeded 0.06 (Fig. 5).

Fig. 4.

Fig. 4.

Calibration curve for Nomogram model.

Fig. 5.

Fig. 5.

Decision curve of Nomogram model.

This study used multivariate Logistic regression analysis and nomogram model construction to systematically reveal independent risk factors for AF in AMI patients and verify the clinical efficacy of the joint prediction model. The results showed that age, hospitalization days, coronary heart disease history, heart rate, INR, Hb and MPV were independent predictors of AF in AMI patients, and the AUC of the nomogram model was significantly better than that of a single indicator, indicating that the integration of multi-dimensional variables can significantly improve the prediction accuracy. This nomogram model provides a scientific basis for stratification of the risk of AF in AMI patients, and highlights the multi-dimensional effects of underlying disease burden, inflammation-immunity, and myocardial remodeling.

Age is an independent risk factor for AF in AMI patients, and its mechanism involves multiple interactive effects of myocardial aging, atrial fibrosis and autonomic nervous dysfunction [23]. Previous studies have shown that the proportion of patients with AMI complicated by AF is as high as 6%–20%, and the proportion is higher in elderly patients, which is consistent with the results of this study [24]. AF is linked to higher mortality in elderly patients, including those undergoing hip fracture surgery—even without heart failure—and in pacemaker recipients, where it predicts adverse cardiac outcomes [25, 26, 27]. These findings highlight AF as a significant risk factor, underscoring the importance of early identification in AMI patients. It is worth noting that the effect of age on AF in AMI patients may have a non-linear relationship: on the one hand, elderly patients are more prone to electrophysiological disorders due to decreased myocardial elasticity and conduction system degradation [28]; on the other hand, young patients may also be at high risk for AF if they experience severe myocardial damage or genetic atrial matrix abnormalities [29]. The extension of hospitalization days reflects the complexity of the disease and the heterogeneity of treatment response. For example, long-term hospitalizations may induce AF due to repeated myocardial ischemia, electrolyte disorders, or drug side effects such as digitalis toxicity [30]. In addition, extended hospitalization days may also indicate lung infection, deterioration of organ function [31]. Therefore, the number of days in hospital is not only a clinical indicator, but also a “time window” for the dynamic evolution of the disease, which needs to be comprehensively evaluated in conjunction with other biomarkers.

History of coronary heart disease is an independent risk factor for AF in AMI patients, and its mechanism may be related to myocardial scar formation and atrial electrical remodeling [32]. In the past, patients with coronary heart disease were prone to atrial matrix fibrosis and abnormal electrical activity due to multiple myocardial ischemic events, providing a substrate for the development of AF [33]. In addition, coronary heart disease is often accompanied by autonomic dysfunction (such as excessive sympathetic nerve activation), which may promote the development of AF by increasing the heterogeneity of atrial refractory [34]. A fast heart rate suggests excessive activation of the sympathetic-adrenal axis, which not only increases myocardial oxygen consumption, but may also induce reentrant AF by shortening the effective atrial refractory period [35]. It is worth noting that heart rate is very important in the management of AF in patients with AMI: beta blockers can effectively reduce heart rate and improve atrial electrical stability, but the risks of hypotension and deterioration of cardiac function should be vigilant [36]. Therefore, as a predictor of AF in AMI patients, heart rate has clinical significance not only in risk stratification, but also in guiding the optimization of treatment strategies.

Higher INR level suggests the possibility of coagulation dysfunction, which promotes the occurrence of AF through two ways: first, insufficient anticoagulation treatment under high INR conditions is easy to form intraatrial thrombus, leading to local hemodynamic disorders [37]; second, elevated INR is often accompanied by abnormal liver function or vitamin K deficiency, which may indirectly induce AF by interfering with the calcium ion channel function of cardiomyocytes [38]. The mechanisms of the impact of low Hb levels on AF include: insufficient oxygen supply leads to aggravation of myocardial ischemia, which in turn leads to abnormal atrial electrical activity [39]; anemic cardiomyopathy causes ventricular remodeling, which indirectly promotes the occurrence of AF [40]. Therefore, INR and Hb are not only independent predictors of AF in AMI patients, but also important basis for intervention targets (such as optimizing anticoagulation regimens and correcting anemia).

MPV suggests a synergistic effect between platelet activation and inflammatory response [41]. Previous studies have shown that platelet activation can promote atrial thrombosis and aggravate electrophysiological disorders by releasing adenosine diphosphate (ADP) and thromboxane A2 (TXA2) [42]; in addition, elevated MPV may also reflect systemic inflammatory conditions (such as elevated C-reactive protein), which is highly related to the pathological mechanism of AF in AMI patients [43]. It is worth noting that dynamic monitoring of MPV may provide new ideas for early warning of AF in AMI patients: the rapid increase in MPV during the acute phase of AMI may indicate that the inflammatory response is out of control and intensive anti-inflammatory treatment is needed; while the continuous increase in MPV during the recovery phase may impaired myocardial repair and require prolonged anti-platelet therapy [44]. Therefore, MPV is not only a predictor of AF in AMI patients, but also a biomarker reflecting inflammation-thrombosis interaction.

This study built a nomogram prediction model for the risk of AF in AMI patients by integrating multi-dimensional indicators such as age, hospital stay, coronary heart disease history, heart rate, INR, Hb and MPV, providing a new evidence-based tool for clinical practice. The nomogram model (AUC = 0.833) constructed in this study has high practical value in clinical practice. Its advantages are: The selection of variables takes into account the underlying disease burden, inflammation-immune status and clinical dynamic indicators, covering multi-dimensional pathological mechanisms; All variables are clinical routine detection indicators and do not require additional equipment or complex detection processes, and have high clinical practicality; The sensitivity and specificity of the model are good, which can provide a reliable risk threshold in clinical decision-making; Decision curve analysis shows that the model has good clinical net benefits.

Our nomogram provides an interpretable tool for predicting in-hospital AF in AMI. However, machine learning (ML) offers complementary potential by capturing complex patterns in clinical and electrophysiological data. Recent studies demonstrate ML’s value—using P, QRS, and T wave features to predict obstructive coronary disease during treadmill testing, and deep learning models to forecast short-term mortality in pulmonary embolism—highlighting its growing role in cardiovascular risk prediction. Integrating such advanced methods could enhance predictive accuracy in future AF risk models [45, 46]. Future research needs to combine a multidisciplinary perspective to further explore the molecular mechanisms and intervention strategies of AF in AMI patients, and promote the dynamic and individualized development of risk stratification of AF in AMI patients. For example, single-cell sequencing technology is used to analyze the interactions of platelets, lymphocytes and other immune cells in the atrial matrix; machine learning algorithms are used to develop a comprehensive prediction model including biomarkers, imaging features and clinical variables; multi-genomic data (such as genomics, proteomics) and artificial intelligence algorithms are combined to build a more accurate prediction model and explore new intervention strategies for AMI patients with AF (such as anti-inflammatory therapy, atrial electrophysiological regulation). In addition, dynamic monitoring of the changing trends of INR, Hb and MPV may provide more accurate time window information for the prognosis of AMI patients with AF. Eventually, the predictive model of AF in AMI patients’ needs to be integrated with clinical pathways to promote the in-depth application of precision medicine in the field of cardiovascular emergencies.

However, the limitations of the model still need to be addressed: The sample size is relatively small, and its extrapolation needs to be verified through a multi-center prospective study; It does not distinguish between paroxysmal and persistent AF, or between new-onset and pre-existing AF; It does not include joint analysis of imaging indicators (such as left atrial enlargement and abnormal ventricular wall motion), which may underestimate the comprehensiveness of the model; The lack of analysis of the interaction between inflammatory pathways and gene polymorphisms limits the exploration of individualized treatment targets. We explicitly acknowledge potential detection bias arising from variable telemetry exposure vs intermittent ECGs and note that single-center practices may limit generalizability.

Multivariable prediction model based on age, hospital stay, coronary heart disease history, heart rate, INR, hemoglobin, and average platelet volume has good prediction effect. The variables in this nomogram model are easily obtained in clinical practice and can provide reference for individualized prediction of AF in AMI patients.

AMI, acute myocardial infarction; AF, atrial fibrillation; PCI, percutaneous coronary intervention; CABG, coronary artery bypass grafting; BMI, body mass index; TG, triglyceride; TC, total cholesterol; HDL-C, high-density lipoprotein cholesterol; LDL-C, low-density lipoprotein cholesterol; APTT, Activated Partial Thromboplastin Time; INR, International Standardized Ratio; FDP, fibrin degradation products; DD, D-dimer; WBC, white blood cells; HB, Hemoglobin; PLT, platelets; MPV, Mean Platelet Volume; NEUT%, Neutrophils Percentage; NEUT, Neutrophils Count; SD, standard deviation; ROC, receiver operating characteristic; DCA, Decision Curve Analysis; ADP, adenosine diphosphate; TXA2, thromboxane A2.

The datasets used and analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

GY, LF and XNH designed the research study and made substantial contributions to the conception and design. They were also involved in drafting the manuscript and critically reviewing it for important intellectual content. YLP and MKX performed the research, contributed to the acquisition of data, and participated in drafting and critically reviewing the manuscript. WWD and DCC contributed to the analysis and interpretation of data, and critically reviewed the manuscript. MTN and SJY contributed to the conception and design of the study and were involved in the critical review of the manuscript. All authors have participated sufficiently in the work to take public responsibility for appropriate portions of the content and have agreed to be accountable for all aspects of the work, ensuring that questions related to the accuracy or integrity of any part of the work are appropriately investigated and resolved. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

The study was carried out in accordance with the guidelines of the Declaration of Helsinki, approved by the Ethics Committee of Beijing Anzhen Hospital, Capital Medical University (approval number: 2024-05). Due to the retrospective nature of the study and the use of deidentified patient data, the requirement for informed consent was waived.

Not applicable.

(1) General Project of the National Natural Science Foundation of China (62272327); (2) “Yang Fan 3.0”, Clinical Medicine Development Special Project of Beijing City Hospital Management Center (YGLX202); (3) 2024 CSC Clinical Research Special Fund of the Chinese Medical Association (CSCF2024B03).

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

Publisher’s Note: IMR Press stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.