1 Department of Cardiology, Universitas Padjajaran, Dr Hasan Sadikin General Hospital, 40161 Bandung, Indonesia

Abstract

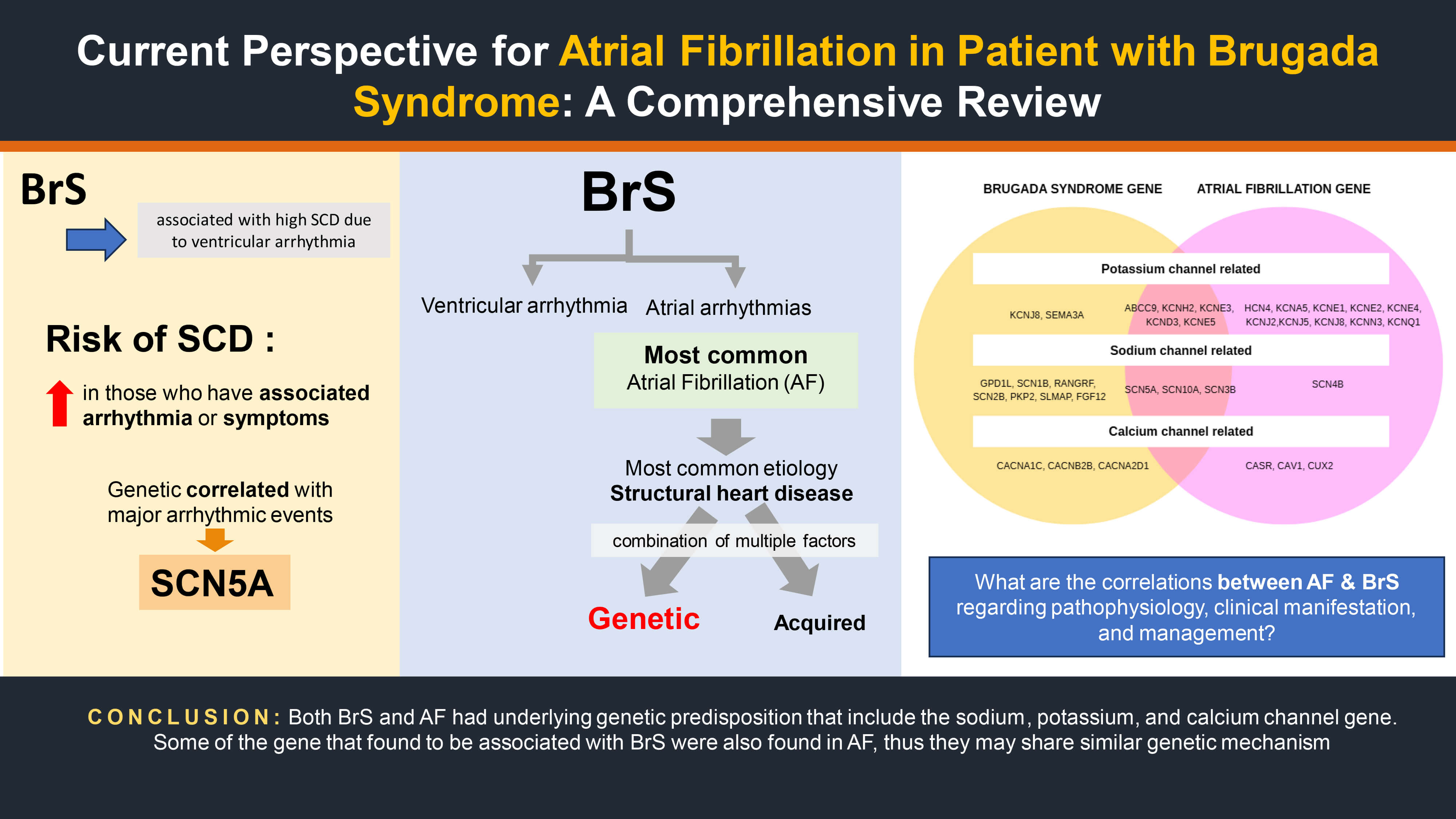

Brugada syndrome (BrS) is an inherited cardiac arrhythmia disorder associated with sudden cardiac death (SCD), primarily due to ventricular tachycardia (VT) or ventricular fibrillation (VF). Meanwhile, atrial fibrillation (AF) is becoming increasingly recognized in BrS cases, with a higher prevalence noted among individuals harboring Sodium Voltage-Gated Channel Alpha Subunit 5 (SCN5A) variants. However, the prognostic value and management implications of AF in BrS remain unclear. Therefore, this narrative review aims to summarize current evidence on the prevalence, clinical significance, pathophysiological mechanisms, and management of AF in BrS. Relevant studies were identified through systematic searches in the PubMed, EBSCOhost, and Google Scholar databases from inception to July 2025 using Boolean operators with keywords such as “Brugada Syndrome” AND “Atrial Fibrillation”, “Brugada” AND “AF” AND “Management”, and “Brugada” AND “SCN5A” AND “Atrial Arrhythmia”. The bibliographies of the selected articles were further reviewed to identify additional relevant studies. The prevalence of AF among patients with BrS ranged from 6% to 39% across various cohorts. Observational studies demonstrated a higher incidence of SCN5A-positive BrS, suggesting that overlapping atrial and ventricular arrhythmogenic substrates exist. Unrecognized BrS in patients presenting with AF may result in inappropriate administration of sodium channel-blocking agents, potentially triggering malignant ventricular arrhythmias. Management strategies include the careful selection of antiarrhythmic drugs, consideration of pulmonary vein isolation (PVI), and implantation of an implantable cardioverter-defibrillator (ICD) device in high-risk cases. Quinidine remains a potential pharmacological option for recurrent ventricular arrhythmias. AF is a relatively common but understudied arrhythmia in BrS. While the direct association of AF with SCD remains uncertain, AF may serve as a marker of a more arrhythmogenic phenotype in BrS. Nonetheless, current guidelines provide limited recommendations for managing AF in this population, underscoring the need for individualized treatment strategies and further research.

Graphical Abstract

Keywords

- Brugada syndrome

- atrial fibrillation

- SCN5A

- Implantable Cardioverter-Defibrillator

- genetic mutation

Brugada syndrome (BrS) is an inherited arrhythmogenic disorder associated with sudden cardiac death (SCD), most commonly due to ventricular arrhythmias [1]. The predominant arrhythmic events in BrS are ventricular tachycardia (VT) and ventricular fibrillation (VF); however, other rhythm disturbances, including atrial fibrillation (AF), are frequently observed [2]. The presence of AF in BrS has been linked to a more clinical course [1].

AF is frequently reported among individuals carrying SCN5A mutations—a gene also implicated in BrS [1, 3]. In patients carrying an SCN5A loss-of-function mutation, age-dependent atrial fibrosis and marked conduction slowing—linked to approximately a 50% decrease in atrial Connexin 43 expression—have been reported, indicating a possible common genetic basis for AF and BrS [4].

Multiple studies have identified AF as one of the most common atrial rhythm disturbances in BrS [5]. Reported prevalence of AF among BrS patients in previous investigations spans from 6% to 39% [1]. Although AF is typically attributed to structural heart disease, other etiologic factors should not be overlooked. AF may arise from a combination of inherited and acquired influences affecting autonomic regulation, atrial anatomy, conduction velocity, and possibly other unidentified mechanisms [3].

It has been proposed that disruptions in electrical conduction within the atria and ventricles contribute to disease progression [6]. The risk of SCD increases in patients with recurrent syncope, family history of SCD, autonomic imbalance, atrial remodeling, and conduction delay [6]. However, the prognostic significance of AF in BrS remains uncertain, as most studies have assessed major arrhythmic events (MAEs) rather than direct correlations with SCD [1].

Given the relatively high prevalence of AF in BrS and the unclear mechanisms linking the two, this review aims to provide a comprehensive overview of the epidemiology, clinical significance, pathophysiology, and management of AF in BrS.

This narrative review was conducted following a structured search strategy. Literature searches were performed in PubMed, EBSCOhost, and Google Scholar from database inception to July 2025. Boolean operators were used to combine Medical Subject Headings (MeSH) and free-text terms: “Brugada Syndrome” AND “Atrial Fibrillation”, “Brugada” AND “AF” AND “Management”, and “Brugada” AND “SCN5A” AND “Atrial Arrhythmia”. No language restrictions were applied. Additional relevant studies were identified by manually reviewing the reference lists of selected articles and recent clinical guidelines. Eligible studies included observational cohorts, clinical trials, case series, and major review articles addressing the epidemiology, pathophysiology, clinical outcomes, or management of AF in BrS. Editorials, correspondence without original data, and studies not addressing AF in BrS were excluded.

According to a meta-analysis of six studies, AF is correlated with an increased risk in individuals diagnosed with BrS [1]. In a study by Ghaleb et al. [7] among 78 AF patients under 45 years of age without prior structural heart disease, 13 (16.7%) exhibited a type 1 Brugada electrocardiogram (ECG) pattern, identified via Holter monitoring or class IA/C antiarrhythmic drugs (IA/C) provocation testing. These patients more frequently reported syncope and a family history of BrS compared with controls [7]. This prevalence is higher than reported in earlier studies, supporting the hypothesis that AF may be linked to latent BrS. In another study of 190 patients with lone AF, 11 demonstrated Brugada ECG patterns following flecainide challenge; none experienced SCD, although three developed VF [8]. In the TETRIS investigation, Conte and colleagues found that of 522 individuals with inherited arrhythmia syndromes (IAS) who also had atrial arrhythmias (AAs), 355 (68%) were identified as having BrS [9]. This substantial proportion underscores the close association between AF and BrS, suggesting that AF is not merely incidental but may serve as a clinical marker of underlying sodium channel dysfunction and atrial conduction abnormalities in BrS patients [10].

The frequent coexistence of AF and BrS suggests a shared arrhythmogenic substrate involving both atrial and ventricular myocardium, potentially increasing arrhythmic risk and influencing clinical management strategies. Up to 30% of BrS patients experience AF without provocation, and its presence is often associated with a less favorable prognosis [11].

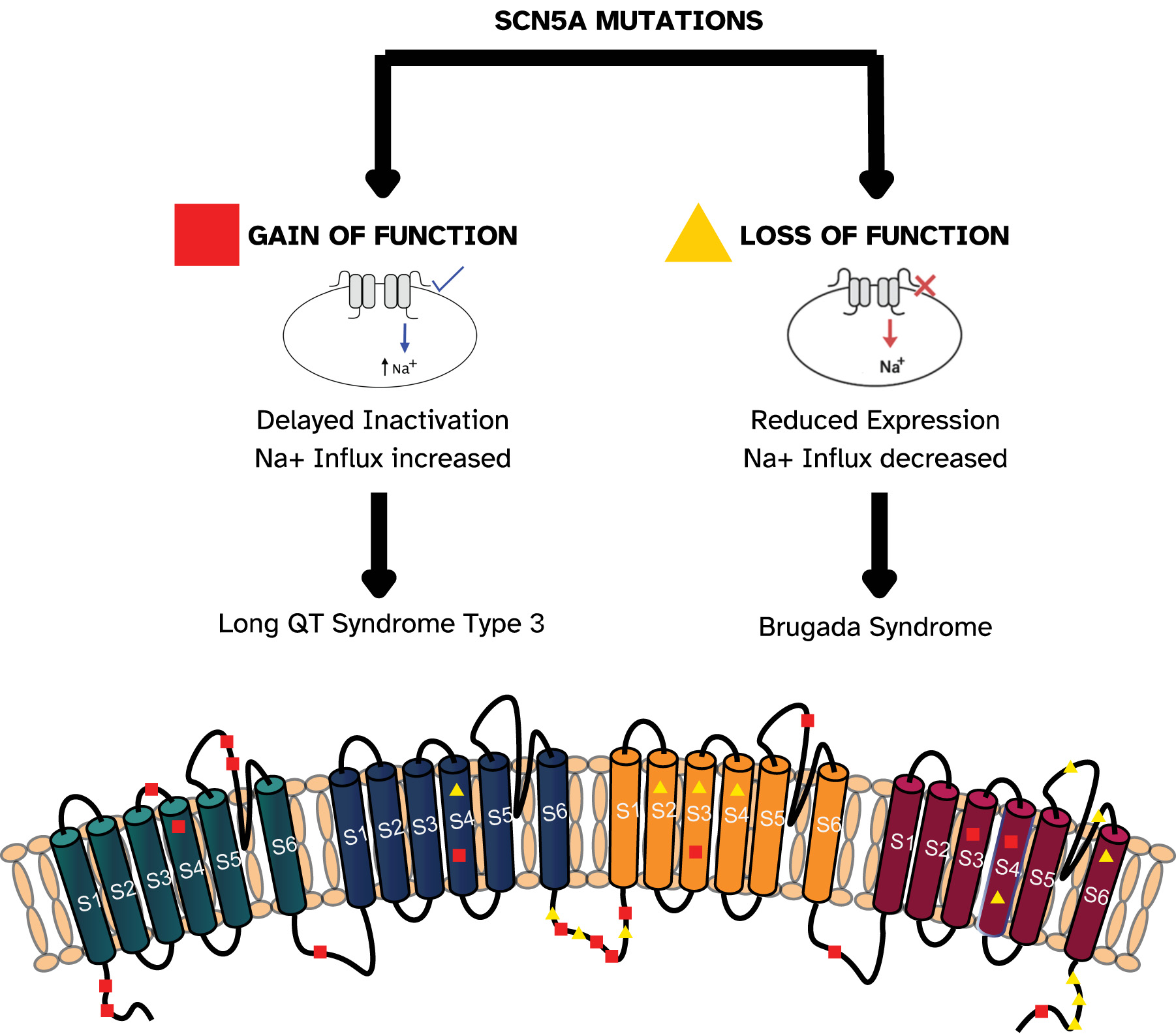

BrS is linked to various genetic abnormalities, most notably in SCN5A, which accounts for more than a hundred identified mutations, Fig. 1 (Ref. [12]), present in approximately 20%–30% of patients [13]. Less commonly, variants have been identified in genes affecting sodium currents (Sodium Voltage-Gated Channel Beta Subunit 1 (SCN1B), SCN10A) and calcium currents (Calcium Voltage-Gated Channel Subunit Alpha1 C (CACNA1C), Calcium Voltage-Gated Channel Auxiliary Subunit Alpha 2 delta 1 (CACNA2D1), Calcium Voltage-Gated Channel Auxiliary Subunit Beta 2B (CACNB2B)) [14]. These mutations typically result in loss-of-function effects, leading to reduced sodium or calcium channel activity and subsequent alterations in cardiac electrophysiology. The functional consequences of these genetic defects have been validated through various experimental approaches. Experimental work on zebrafish also demonstrated that loss-of-function mutations in zebrafish sodium channel orthologs reproduce hallmark BrS features, including slowed atrioventricular conduction, spontaneous arrhythmias, and ST-segment elevation–like ECG changes [15].

Fig. 1.

Fig. 1.

Schematic representation of Nav1.5 channel domains and examples of SCN5A mutations associated with gain- and loss-of-function effects. The SCN5A transcript, consisting of 28 exons, encodes the

The European Society of Cardiology (ESC) guidelines for managing ventricular

arrhythmias advise SCN5A genetic testing for all individuals with a

confirmed diagnosis of Brugada syndrome [14]. In humans, the SCN5A gene

encodes the

Genetic studies have identified 23 genes associated to Brugada syndrome, organized by the ionic currents they regulate: sodium (INa) — SCN5A, SCN10A, Glycerol-3-Phosphate Dehydrogenase 1-Like (GPD1L), SCN1B, SCN3B, RAN Guanine Nucleotide Release Factor (RANGRF), SCN2B, Plakophilin 2 (PKP2), Sarcolemma Associated Protein (SLMAP), Fibroblast Growth Factor 12 (FGF12); potassium (IK) — Potassium Inwardly Rectifying Channel Subfamily J Member 8 (KCNJ8), Potassium Voltage-Gated Channel Subfamily H Member 2 (KCNH2), Potassium Voltage-Gated Channel Subfamily E Regulatory Subunit 3 (KCNE3), Potassium Voltage-Gated Channel Subfamily D Member 3 (KCND3), KCNE5, KCND2, Semaphorin 3A (SEMA3A), ATP Binding Cassette Subfamily C Member 9 (ABCC9); calcium (ICa) — CACNA1C, Calcium Voltage-Gated Channel Auxiliary Subunit Beta 2B (CACNB2B), CACNA2D1 [18].

Similarly, AF-related genetic variants include potassium channel genes (ABCC9, Hyperpolarization Activated Cyclic Nucleotide Gated Potassium Channel 4 (HCN4), Potassium Voltage-Gated Channel Subfamily A Member 5 (KCNA5), KCND3, KCNE1, KCNE2, KCNE3, KCNE4, KCNE5, KCNH2, Potassium Inwardly Rectifying Channel Subfamily J Member 2 (KCNJ2), KCNJ5, KCNJ8, Potassium Calcium-Activated Channel Subfamily N Member 3 (KCNN3), Potassium Voltage-Gated Channel Subfamily Q Member 1 (KCNQ1)) and sodium channel genes (SCN3B, SCN4B, SCN5A, SCN10A), and genes involved in gap junction and nuclear pore complex function (Gap Junction Protein Alpha 5 (GJA5), Nucleoporin 155 (NUP155), E169K, Calcium-Sensing Receptor (CASR), Paired Like Homeodomain 2 (PITX2), Nuclear Receptor Subfamily 4 Group A Member 2 (NURL1/NR4A2), Paired Related Homeobox 1 (PRRX1), Caveolin 1 (CAV1), Cut Like Homeobox 2 (CUX2), Zinc Finger Homeobox 3 (ZFHX3)) [19].

Three of the ten sodium channel-related genes (SCN5A, SCN10A, SCN3B) and five of eight potassium channel-related genes (ABCC9, KCNH2, KCNE3, KCND3, and KCNE5) implicated in BrS are also associated with AF [16]. While no BrS-associated calcium channel genes have been definitively linked to AF, SCN5A remains the most extensively studied due to its high prevalence among BrS patients [3, 19].

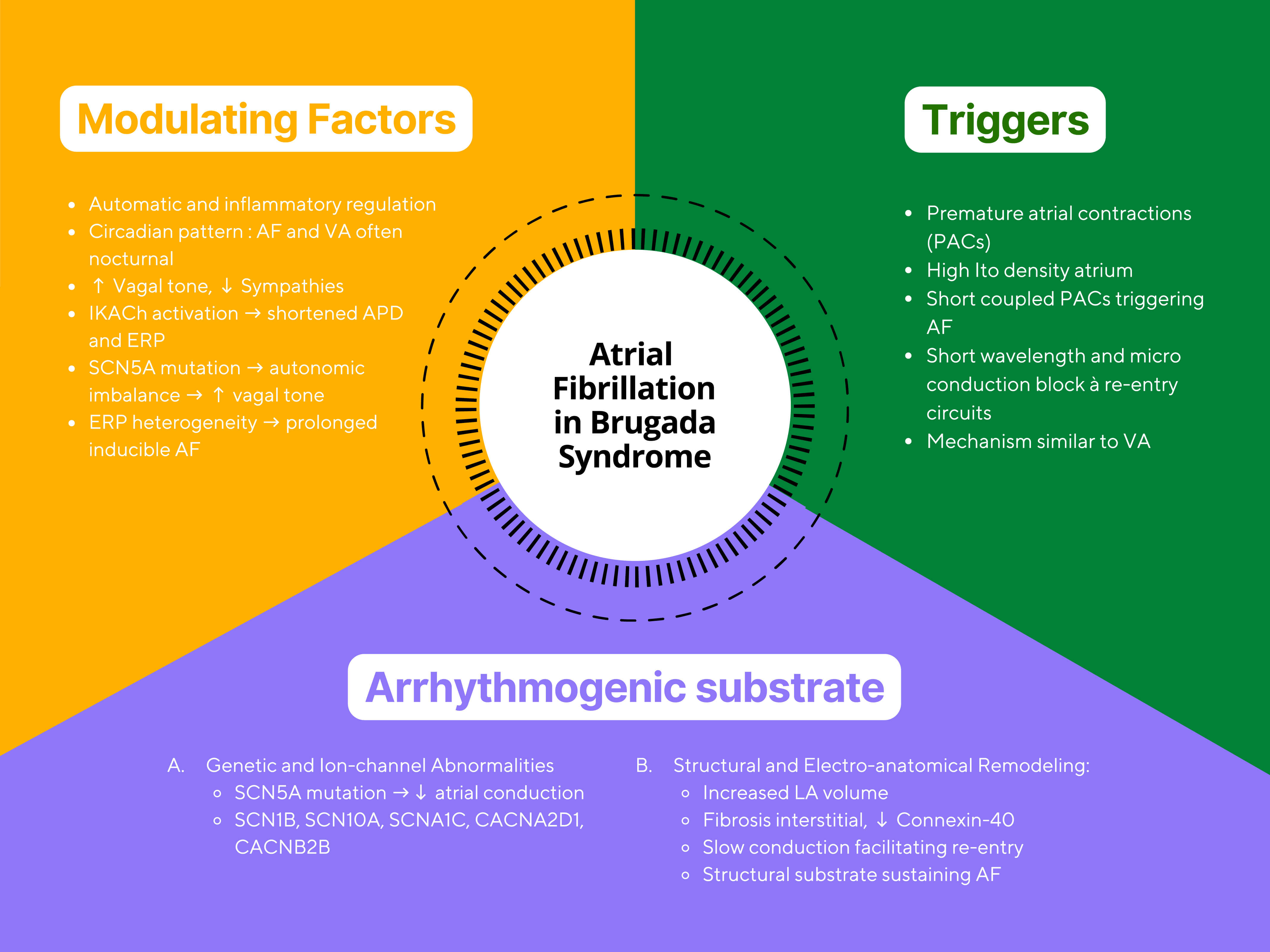

The pathophysiology of AF in BrS involves an interplay between arrhythmogenic triggers, a vulnerable myocardial substrate, and modulators such as autonomic tone and inflammation (Fig. 2) [4]. AF often follows a circadian rhythm, with most episodes arising at night when vagal influence is greater. Increased vagal stimulation decreases atrial conduction velocity and reduces refractory periods, creating favorable conditions for AF onset [4]. Experimental studies have shown that vagal stimulation can shorten atrial refractory periods and slow conduction, facilitating re-entry. Parasympathetic denervation via ganglionated plexi ablation has been shown to reduce AF by eliminating vagal input, prolonging the effective refractory period (ERP), stabilizing atrial conduction, and suppressing pulmonary vein triggers [20, 21, 22, 23, 24, 25, 26, 27, 28, 29].

Fig. 2.

Fig. 2.

Conceptual illustration of atrial fibrillation mechanisms in Brugada syndrome. The figure summarizes the interaction between autonomic triggers, arrhythmogenic substrate, and modulating factors. Abbreviations: AF, atrial fibrillation; BrS, Brugada syndrome; APD, Action Potential Duration; PAC, Premature Atrial Contraction; Ito, Transient Outward Potassium Current; SCN5A, Sodium Voltage-Gated Channel Alpha Subunit 5; LA, left atrium; VA, ventricular arrhythmia; IKAch, Acetylcholine-Activated Potassium Current; ERP, Effective Refractory Period.

Structural atrial abnormalities in BrS and AF patients can delay interatrial conduction, usually serving as a substrate for re-entry [30]. Re-entry requires both an anatomical or functional block and an excitable gap [30]. Slow atrial conduction facilitates re-entry and may explain the higher incidence of tachyarrhythmias in BrS patients [1]. Bradycardia and heightened vagal tone may also reduce calcium influx, contributing to ST-segment elevation and proarrhythmic risk [31].

Abnormalities in cardiac conduction and repolarization are strongly associated

with SCN5A mutations, which code for the

Atrial remodeling creates conduction heterogeneity between the atrial myocardium and conduction pathways, acting as both a trigger and perpetuator of AF [35]. One study reported a shortened atrial effective refractory period in the first days of AF, downregulation of L-type calcium channel currents, and upregulation of potassium currents, which shorten the atrial ERP, potentially contributing to the arrhythmogenesis seen in BrS [31].

Autonomic imbalance plays a critical role in AF onset; increased vagal tone slows atrial conduction and shortens refractoriness [36]. Mutations in SCN5A may exacerbate intra-atrial conduction delay [32], and patients with both BrS and AF often exhibit marked conduction slowing, suggesting that impaired atrial conduction is a key electrophysiological substrate for AF initiation [30]. Signal-averaged ECG studies have demonstrated prolonged filtered P-wave duration and a higher prevalence of interatrial block in BrS patients with AF, supporting conduction delay as a central mechanism [10].

The clinical presentation of atrial fibrillation of AF ranges widely, from asymptomatic cases to severe outcomes such as cardiogenic shock or stroke [37]. Patients may report mild symptoms, including palpitations, fatigue, reduced exercise tolerance, presyncope, syncope, and dizziness [38].

BrS can be diagnosed in both symptomatic and asymptomatic individuals. Among asymptomatic patients, approximately 63% are diagnosed incidentally. Symptomatic presentations most commonly include syncope, seizures, and VT/VF, which, if sustained, may result in sudden cardiac death [2, 37]. Data from the SABRUS registry indicate that the incidence of syncope and SCD in BrS ranges from 17% to 42%, with SCD most frequently occurring in adult men [37].

Atrial arrhythmias are increasingly recognized in BrS, with prevalence estimates between 6% and 38% [1]. Among these, AF is the most common, affecting approximately 10–20% patients, and is often associated with syncope and an elevated risk of SCD [2]. Genetic analyses have linked AF to SCN5A mutations, which are also implicated in BrS, suggesting a possible shared genetic basis. However, this association remains incompletely understood.

Treating AF in patients with BrS poses significant challenges. Due to the pro-arrhythmic potential of sodium channel-blocking antiarrhythmic drugs (AADs), Class IC agents, including flecainide and propafenone, are generally avoided [39]. Furthermore, certain Class III agents, including amiodarone and sotalol, may be hazardous due to their effects on repolarization and potential to induce bradycardia-related arrhythmias [40]. These pharmacological limitations necessitate the investigation of novel therapeutic strategies. In addition to standard treatment strategies, innovative technologies are increasingly shaping AF management. Artificial intelligence (AI) offers significant opportunities across the care spectrum—from early detection and individualized risk assessment to guiding therapeutic choices [41].

Quinidine, a class IA antiarrhythmic that blocks both Ito and IKr currents, has demonstrated potential benefits in preventing ventricular arrhythmias and suppressing AF in BrS patients [39, 42, 43]. In a study by Giustetto et al. [42], hydroquinidine effectively suppressed AF episodes over 28 months of follow-up in BrS patients. In the cohort studied by Mazzanti et al. [44], BrS patients with symptomatic AF treated with quinidine experienced no AF during follow-up, suggesting quinidine may stabilize atrial rhythm while primarily targeting ventricular arrhythmia prevention. Kusano et al. [45] reported that two patients with AF and recurrent VF who received quinidine and bepridil experienced no further AF episodes during treatment. Bepridil, a multichannel-blocking AAD, has been shown to reduce both atrial and ventricular arrhythmias in BrS, though its use is limited by risk of QT prolongation and torsades de pointes [40]. Despite limited evidence, bepridil may be considered in highly selected patients under close monitoring.

Pulmonary vein isolation (PVI) has been evaluated as a rhythm control strategy for BrS patients with symptomatic or drug-refractory AF [37]. In one series, freedom from AF after PVI was 76.7%, slightly lower than in the general AF population (80–90%, depending on patient characteristics and ablation techniques) [7]. In BrS, PVI significantly reduces inappropriate implantable cardioverter–defibrillator (ICD) therapies [37]. Similarly, Kitamura et al. [46] reported a 92.9% success rate in maintaining sinus rhythm post-PVI and complete elimination of inappropriate ICD therapies after ablation in BrS patients with prior inappropriate shocks. A meta-analysis by Rodríguez-Mañero et al. [47] reviewed 49 studies on procedural interventions for AF in BrS, including 49 patients with both BrS and AF, and 39% are still experiencing inappropriate shocks due to AF episodes prior to undergoing PVI [7]. During long-term follow-up after one or more PVI sessions, 91.8% of BrS patients remained free from arrhythmia, and no further inappropriate ICD discharges occurred, supporting catheter ablation as an effective and safe option [7]. Mugnai et al. [48] further corroborated these findings, showing a 74% freedom from AF recurrence at three years post-PVI without antiarrhythmic drugs and no major procedural complications. Nonetheless, catheter ablation in BrS requires caution, as underlying structural and electrical atrial abnormalities may contribute to increased post-ablation recurrence risk. Further research is warranted to define optimal ablation strategies and refine patient selection criteria.

The role of ICD implantation in BrS patients with concomitant AF remains

debated. While ICDs are highly effective in preventing SCD, AF increases the risk

of inappropriate shocks due to misclassification of rapid atrial rhythms as

ventricular arrhythmias. This may result in patient discomfort, psychological

distress, and potential proarrhythmic effects. AF in BrS may also signify more

diffuse conduction abnormalities [39, 49]. Inappropriate ICD shocks are frequently

triggered by AF. Optimal device programming—such as setting a single, high-rate

VF detection zone (

| Study | Year | N | BrS + AF | Method | Intervention | Key findings | Outcome |

| Giustetto et al. [42] | 2014 | 560 | 48 (9%) | Registry-based observational study | Quinidine | Group 1 (AF after BrS diagnosis): younger age, higher spontaneous type 1 ECG, worse prognosis. Group 2 (BrS unmasked by IC drugs): older, better prognosis | AF prevalence is higher than in the general population. HQ is effective and safe for AF prevention |

| Kusano et al. [45] | 2008 | 2 | 2 | Case series | Quinidine 0.3 g oral; Bepridil 100–200 mg/day | No episodes of AF were observed during the therapy | Effective |

| Mazzanti et al. [44] | 2019 | 53 | 9 (17%) | Prospective Cohort | Quinidine | No recurrent AF episodes | Effective |

| Bisignani et al. [37] | 2022 | 60 (BrS + AF)/60 (control) | 60 (50%) | Comparative matched cohort study | PVI | AF freedom rates of 76.7% in BrS vs. 83.3% in control | PVI is less effective in the BrS group |

| Rodríguez-Mañero et al. [47] | 2019 | 49 | 49 (100%) | Systematic review | PVI | 91.8% success rate with PVI; 100% elimination of inappropriate ICD shocks | PVI is highly effective and safe |

| Kitamura et al. [46] | 2016 | 14 | 14 (100%) | PVI (RF) | PVI (RF) | 92.9% had no recurrence of AF | Excellent outcomes with a systematic approach |

| Mugnai et al. [48] | 2018 | 23 | 13 (56%) underwent PVI | Retrospective observational study | PVI | 74% AF-free at 3 years | Good success with both technologies |

Abbreviations: AF, atrial fibrillation; BrS, Brugada syndrome; ICD, implantable cardioverter-defibrillator; PVI, pulmonary vein isolation; RF, radiofrequency; VT, ventricular tachycardia; VF, ventricular fibrillation; ECG, electrocardiogram; IC, Ion Channel; HQ, Hydroquinidine.

One of the most concerning clinical challenges is the unrecognized coexistence of BrS in patients presenting with AF [32]. In such cases, the use of commonly prescribed antiarrhythmic agents for AF management, particularly Class IC drugs such as flecainide or propafenone, may provoke potentially fatal ventricular arrhythmias or sudden cardiac death among individuals with latent Brugada patterns [51]. Class III drugs—such as amiodarone and sotalol—may also exacerbate arrhythmogenic risk through bradycardia-mediated mechanisms or alteration in repolarization [52].

Several case series and registry-based studies have documented instances in which AF was the initial presentation, with BrS remaining undiagnosed until patients experienced ventricular tachyarrhythmias following exposure to sodium channel blockers [7, 35]. Expanding upon the findings of Iqbal et al. [53], which indicated a heightened likelihood of sudden cardiac death among individuals with BrS who also exhibited AF, the current investigation examines their clinical profiles, electrophysiological patterns, and potential overlapping mechanisms, aiming to refine both risk assessment and therapeutic approaches. Supporting this concern, observational data from Ghaleb et al. [7] demonstrated that among AF patients younger than 45 years without structural heart disease, 16.7% exhibited a type 1 Brugada electrocardiographic pattern, highlighting the underrecognized prevalence of concealed BrS in this population. This risk underscores the importance of identifying Brugada electrocardiogram patterns, whether occurring spontaneously or induced by pharmacological agents, prior to initiating any Class I antiarrhythmic therapy.

Because concealed BrS may remain dormant, particularly in younger patients without structural heart disease, baseline ECG screening should be considered in all new-onset AF cases, especially when AF occurs at a young age or in the presence of a suggestive family history [36]. In selected cases, ajmaline or flecainide challenge testing may be warranted to unmask a Brugada phenotype, provided the procedure is performed in a controlled electrophysiology laboratory setting [54, 55].

To prevent iatrogenic complications, greater clinician awareness is essential, supported by guideline-based precautions before prescribing sodium channel-blocking drugs [14]. Eventually, there is a pressing need to develop standardized screening protocols for BrS in AF patients, particularly in those with early-onset disease or unexplained syncope, and to conduct further research evaluating the cost-effectiveness and clinical outcomes of such screening strategies. Implementation of these measures could substantially reduce the risk of preventable, drug-induced ventricular rhythm disturbances in this vulnerable overlap population.

A mutation in the SCN5A gene alters sodium channel function, resulting in abnormal depolarization and repolarization that can trigger arrhythmias, including AF. Due to the shared genetic basis between AF and BrS through SCN5A mutations, the risk of AF in BrS patients is higher than in the general population. AF in the context of BrS may indicate a more severe disease phenotype and may increase the incidence of inappropriate ICD shocks. Both BrS and AF have underlying predispositions involving sodium, potassium, and calcium channels. Several genes associated with BrS have also been implicated in AF, suggesting shared genetic mechanisms. Although BrS is primarily a ventricular arrhythmia, the presence of AF may indicate that the genetic expression predisposing to BrS has already manifested. BrS and AF are thought to arise as phenotypic manifestations of shared genetic mutations, which may explain the genetic link between these two arrhythmic entities. Treatment recommendations for AF in BrS remain limited; however, dual-chamber ICD implantation, quinidine therapy, and PVI have demonstrated some benefit in this patient population.

MI conceived and designed the study. RB, KK, and GK contributed to data collection and analysis. CA contributed to the conceptual design of the study, assisted in data interpretation, supervised the overall research process, and provided substantial intellectual input through critical revision of the manuscript. All authors participated in manuscript drafting, reviewed and approved the final version for publication, and agreed to be accountable for all aspects of the work.

Not applicable.

The authors would like to express their sincere gratitude to all colleagues and collaborators who contributed to this work.

This research received no external funding.

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

Publisher’s Note: IMR Press stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.