1 Department of Cardiovascular Surgery, Beijing Anzhen Hospital, Capital Medical University, 100029 Beijing, China

2 Department of Medicine, Renal Electrolyte and Hypertension Division, Perelman School of Medicine, University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia, PA 19104, USA

3 Center for Cardiac Intensive Care, Beijing Anzhen Hospital, Capital Medical University, 100029 Beijing, China

4 Department of Anesthesiology, Beijing Anzhen Hospital, Capital Medical University, 100029 Beijing, China

5 Department of Cardiovascular Surgery, Beijing Tongren Hospital, Capital Medical University, 100176 Beijing, China

6 Department of Cardiovascular Surgery, Beijing Hospital, 100005 Beijing, China

7 Department of Cardiovascular Surgery, Xuanwu Hospital Capital Medical University, 100053 Beijing, China

8 Department of Cardiovascular Surgery, Peking University People's Hospital, 100044 Beijing, China

†These authors contributed equally.

Abstract

We hypothesized that body surface area (BSA)-weighted left ventricular ejection fraction (LVEF) (bLVEF) would represent a superior predictor of mortality in off-pump coronary artery bypass grafting (OPCABG) patients than standard predictors. LVEF is associated with worse outcomes upon OPCABG, while referring left ventricular measurements to BSA should improve predictability.

The bLVEF was calculated by multiplying the LVEF by the BSA. The primary endpoint was all-cause mortality within 30 days of hospitalization, while secondary endpoints included major postoperative complications.

A total of 7927 patients from five leading cardiac centers participating in the Chinese Cardiac Surgery Registry were included in the final analysis, of which 7093 (89.48%) had normal LVEF, 639 (8.06%) presented heart failure with mid-range ejection fraction (HFmrEF), and 195 (2.46%) exhibited heart failure with reduced ejection fraction (HFrEF). The average bLVEF in the cohort was 109.63 ± 18.16. Both the mortality (odds ratio (OR) 0.97) and secondary endpoints (OR 0.97) followed a similar trend with increasing bLVEF, indicating that bLVEF is a more reliable predictor of adverse outcomes. The individual components of bLVEF, including BSA (area under the curve (AUC) 0.63) and LVEF (AUC 0.64), made minor contributions to mortality risk with relatively low AUC values. However, these components were less impactful than bLVEF (AUC 0.70). Notably, patients with a bLVEF less than 85 had an increased mortality risk relative to those whose bLVEF was 85 or higher (adjusted OR 4.65 (95% confidence interval (CI): 3.81–5.83; p < 0.01)).

The bLVEF serves as a key predictor of mortality in OPCABG patients, effectively eliminating BSA-related bias and demonstrating a strong capacity to predict mortality.

NCT02400125, https://www.clinicaltrials.gov/study/NCT02400125.

Keywords

- BSA

- LVEF

- OPCABG

- outcomes

In the 1990s, interest in performing coronary artery bypass grafting (CABG) on a beating heart, avoiding cardiopulmonary bypass, experienced a resurgence, leading to renewed focus on off-pump surgery [1, 2]. Off-pump coronary artery bypass grafting (OPCABG) has been widely utilized in patients with heart failure (HF) due to its association with reduced perioperative complications and improved long-term outcomes compared to on-pump procedures [3, 4]. The left ventricular ejection fraction (LVEF) is an indicator to evaluate HF, which associates with the outcomes in cardiac surgery [5]. Patients with low LVEF face a high risk of perioperative complications, adversely affecting both immediate and long-term survival. This risk is particularly pronounced in those with ventricular contractility impairment following cardiopulmonary bypass and cardioplegia, regardless of other comorbidities [6, 7]. In OPCABG, reduced LVEF, often associated with ischemic cardiomyopathy, is linked to an increased risk of long-term complications [8, 9, 10]. Further investigation is needed to elucidate the relationship between LVEF and perioperative outcomes in OPCABG, offering greater insight into its prognostic significance.

LVEF refers to the percentage of blood volume in the left ventricle at the end

of diastole that is pumped out with each contraction, which can be expressed

mathematically as

Consequently, we aimed to explore the distinct effects of LVEF, BSA, and bLVEF on early clinical outcomes for OPCABG patients using data from five leading Chinese cardiovascular centers. The objectives were to investigate (1) the impact of LVEF on perioperative outcomes, (2) the correlation between BSA and LVEF, and (3) the association of bLVEF with perioperative complications and mortality rates among.

We analyzed data from 7927 patients across five prominent Chinese cardiovascular

centers: Beijing Anzhen Hospital, Beijing Tongren Hospital, Beijing Hospital,

Peking University People’s Hospital, and Beijing Xuanwu Hospital. The data,

sourced from the Chinese Cardiac Surgery Registry database, cover admissions that

occurred between December 2016 and January 2021 (refer to Supplementary

Fig. 1). Clinical data were collected in accordance with the Society of Thoracic

Surgeons National Adult Cardiac Database (http://www.sts.org). Data reliability

and comprehensiveness were ensured through established procedures, as detailed in

prior publications [16]. The study protocol was approved by the Ethics Committee

of Fuwai Hospital (Approval No: 2017-943) and is registered at

http://www.clinicaltrials.gov (NCT02400125). Patient confidentiality was

maintained by pseudo-anonymizing all data, substituting patient names with

identification codes and removing private information before analysis. A data

committee from the Peking University Clinical Research Institute was responsible

for assessing data quality and overseeing data quality and collection. All

participants received standard care, with no additional interventions, as

previously described [16]. Heart failure was classified according to the European

Society of Cardiology, including heart failure with reduced ejection fraction

(HFrEF, LVEF

Patient demographics and clinical features were collected and assessed,

including medical histories of peripheral vascular disease, cerebrovascular

events, prior myocardial infarctions, previous percutaneous coronary

interventions, and New York Heart Association (NYHA) classification. Peoperative

test results for serum creatinine, total cholesterol, low-density lipoprotein,

blood glucose levels, and estimated glomerular filtration rate (eGFR) were also

recorded. Intraoperative echocardiogram data were examined for left ventricular

end-diastolic volume (LVED), left ventricular end-diastolic diameter (LVEDd), and

left atrial dimension (LAD). Data on concomitant cardiac medications—including

nitrate lipid drugs, catecholamines,

Missing values and outliers were addressed using multiple imputations via the

Multivariate Imputation by Chained Equations (MICE) package [17]. As the database

was systematically monitored by a data committee, missing values and outliers

represented less than 2% of all metrics. We assumed that missing data and

misrecordings occurred randomly [18], and used predictive mean matching to

generate five imputed datasets suitable for logistic model fitting [19]. For

multivariate logistic regression, we adjusted for the following variables based

on clinical expertise: age, gender, smoking within two weeks prior to surgery,

diabetes, hypertension, hyperlipidemia, the last serum creatinine test before

surgery, the last total cholesterol test, the last low-density lipoprotein test,

the last blood glucose test, preoperative eGFR, and history of cerebrovascular

events. We used weight-of-Evidence binning which is a technique for binning both

continuous and categorical independent variables in a way that provides the most

robust bifurcation of the data against the dependent variable. This technique was

implemented by the woebin function from R. Continuous variables were categorized

according to established cutoffs. The bLVEF was optimally binned using

evidence-based segmentation via the scorecard package

(https://CRAN.R-project.org/package=scorecard), and coefficients were calculated

using Spearman correction. Continuous variables are presented as mean

A total of 7927 patients were included in the final analysis, among whom 7093

(89.48%) had normal LVEF, 639 (8.06%) had HFmrEF, and 195 (2.46%) had HFrEF.

The cohort’s mean age was 62.61

| Total | LVEF |

40 |

LVEF |

p-value | ||

| Number | 7927 | 195 | 639 | 7093 | ||

| Age | 62.61 |

60.26 |

61.72 |

62.75 |

||

| Gender (male)-n (%) | 6051 (76.33%) | 170 (87.18%) | 542 (84.82%) | 5339 (75.27%) | ||

| BMI | 25.69 |

25.26 |

25.5 |

25.71 |

0.05 | |

| BSA | 1.82 |

1.84 |

1.83 |

1.82 |

0.10 | |

| Smoking-n (%) | 3573 (45.07%) | 116 (59.49%) | 336 (52.58%) | 3121 (44.00%) | ||

| Diabetes-n (%) | 3103 (39.14%) | 94 (48.21%) | 302 (47.26%) | 2707 (38.16%) | ||

| Hypertension-n (%) | 4997 (63.04%) | 102 (52.31%) | 386 (60.41%) | 4509 (63.57%) | ||

| Hyperlipidemia-n (%) | 2698 (34.04%) | 68 (34.87%) | 215 (33.65%) | 2415 (34.05%) | 0.96 | |

| Past medical history | ||||||

| Peripheral vascular disease-n (%) | 240 (3.03%) | 7 (3.59%) | 19 (2.97%) | 214 (3.02%) | 0.89 | |

| Previous cerebrovascular event-n (%) | 1058 (13.35%) | 25 (12.82%) | 94 (14.71%) | 939 (13.24%) | 0.58 | |

| Previous MI-n (%) | 1256 (15.84%) | 82 (42.05%) | 205 (32.08%) | 969 (13.66%) | ||

| Previous PCI-n (%) | 1060 (13.37%) | 26 (13.33%) | 108 (16.9%) | 926 (13.06%) | 0.02 | |

| NYHA1-n (%) | 6087 (76.79%) | 152 (78.35%) | 497 (77.78%) | 5438 (76.66%) | ||

| NYHA2-n (%) | 4489 (56.63%) | 96 (49.48%) | 336 (52.58%) | 4053 (57.13%) | ||

| NYHA3-n (%) | 1518 (19.15%) | 47 (24.23%) | 144 (22.54%) | 1327 (18.71%) | ||

| NYHA4-n (%) | 82 (1.03%) | 9 (4.64%) | 15 (2.35%) | 58 (0.82%) | ||

| Last blood tests before surgery | ||||||

| Serum creatinine (µmol/L) | 74.06 |

84.54 |

80.08 |

73.23 |

||

| Serum total cholesterol (mmol/L) | 4.00 |

4.05 |

3.94 |

4.01 |

0.71 | |

| Serum low-density lipoprotein | 2.37 |

2.44 |

2.37 |

2.37 |

0.53 | |

| eGFR (mL/min/1.73 m2) | 95.45 |

92.72 |

93.44 |

95.70 |

||

| Blood glucose (mmol/L) | 6.49 |

6.76 |

6.68 |

6.46 |

||

| Ultrasound indicators | ||||||

| LVEDd (mm) | 48.98 |

58.31 |

55.27 |

48.16 |

||

| LAD (mm) | 35.86 |

39.04 |

38.29 |

35.55 |

||

| LVEF (%) | 60.24 |

36.20 |

44.32 |

62.34 |

||

| Normalized by weight/100 | 43.22 |

26.17 |

32.03 |

44.7 |

||

| Normalized by BMI/100 | 15.48 |

9.17 |

11.31 |

16.03 |

||

| Normalized by BSA | 109.63 |

66.49 |

81.24 |

113.37 |

||

| Preoperative medication | ||||||

| Nitrate lipid drugs-n (%) | 1733 (21.86%) | 41 (21.03%) | 130 (20.34%) | 1562 (22.02%) | 0.60 | |

| Catecholamines-n (%) | 30 (0.38%) | 1 (0.51%) | 3 (0.47%) | 26 (0.37%) | 0.62 | |

| 6611 (83.40%) | 149 (76.41%) | 546 (85.45%) | 5916 (83.41%) | 0.01 | ||

| ACEI or ARB-n (%) | 1571 (19.82%) | 37 (18.97%) | 129 (20.19%) | 1405 (19.81%) | 0.94 | |

| Statins-n (%) | 5236 (66.05%) | 115 (58.97%) | 413 (64.63%) | 4708 (66.38%) | 0.07 | |

| Aspirin-n (%) | 2284 (28.81%) | 58 (29.74%) | 186 (29.11%) | 2040 (28.76%) | 0.94 | |

| Clopidogrel-n (%) | 555 (7.00%) | 11 (5.64%) | 38 (5.95%) | 506 (7.13%) | 0.40 | |

| Ticagrelor-n (%) | 399 (5.06%) | 13 (6.67%) | 33 (5.19%) | 353 (4.98%) | 0.56 | |

BMI, body mass index; BSA, body surface area; NYHA, New York Heart Association; MI, myocardial infarction; PCI, percutaneous coronary intervention; eGFR, estimated glomerular filtration rate; LVEF, left ventricular ejection fraction; LVEDd, left ventricular end-diastolic diameter; LAD, left atrial dimension; ACEI, angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitor; ARB, angiotensin receptor blocker.

*Smoking within two weeks before surgery. Serum creatinine, serum total cholesterol, serum low-density lipoprotein, eGFR,

blood glucose, LVEF, LVEDd, and LAD are the last tests before surgery. Nitrate lipid drugs are administered intravenously 24 hours before surgery. Catecholamines are administered intravenously 48 hours before surgery.

We further analyzed outcomes across LVEF categories. As shown in Table 2, HFrEF

and HFmrEF patients experienced higher rates of multiorgan failure, acute kidney

injury (AKI), and the cumulative mechanical ventilation time (Table 2, p

for trend

| Total | LVEF |

40 |

LVEF |

p-value | |

| Number | 7927 | 195 | 639 | 7093 | |

| Perioperative blood transfusion-n (%) | 5183 (65.38%) | 135 (69.23%) | 429 (67.14%) | 4619 (65.12%) | 0.31 |

| Mechanical ventilation duration (hour) | 23.55 |

37.39 |

28.48 |

22.73 |

|

| Initial ICU length of stay (hour) | 31.50 |

51.81 |

39.97 |

30.18 |

|

| Perioperative blood loss (mL) | 1017.85 |

1011.68 |

1079.30 |

1012.48 |

|

| Serum creatinine (µmol/L) | 84.57 |

97.80 |

91.89 |

83.55 |

|

| eGFR (mL/min/1.73 m2) | 94.28 |

85.03 |

88.18 |

95.09 |

|

| AKI-n (%) | 641 (8.09%) | 22 (11.28%) | 64 (10.02%) | 555 (7.82%) | 0.04 |

| Use of IAPB-n (%) | 450 (5.68%) | 55 (28.21%) | 80 (12.52%) | 315 (4.44%) | |

| Use of ECMO-n (%) | 37 (0.47%) | 2 (1.03%) | 6 (0.94%) | 29 (0.41%) | 0.05 |

| Reoperation-n (%) | 122 (1.54%) | 5 (2.56%) | 10 (1.56%) | 107 (1.51%) | 0.41 |

| Postoperative MI-n (%) | 48 (0.61%) | 2 (1.03%) | 4 (0.63%) | 42 (0.59%) | 0.52 |

| Postoperative stroke-n (%) | 64 (0.81%) | 1 (0.51%) | 6 (0.94%) | 57 (0.80%) | 0.88 |

| Re-intubation-n (%) | 65 (0.82%) | 3 (1.54%) | 9 (1.41%) | 53 (0.75%) | 0.08 |

| Re-enter ICU-n (%) | 132 (1.67%) | 5 (2.56%) | 11 (1.72%) | 116 (1.64%) | 0.51 |

| Multiorgan failure-n (%) | 45 (0.57%) | 6 (3.08%) | 11 (1.72%) | 28 (0.39%) | |

| Dead-n (%) | 68 (1.05%) | 9 (5.49%) | 10 (1.96%) | 49 (0.84%) |

LVEF, left ventricular ejection fraction; ICU, intensive care unit; eGFR,estimated glomerular filtration rate; AKI, acute kidney injury; IABP, intra-aortic balloon pump; ECMO, extracorporeal membrane oxygenation; MI, myocardial infarction.

*Serum creatinine is the maximum serum creatinine after surgery; eGFR is the minimum eGFR after surgery.

| Mortality | Secondary outcomes | ||||||||||

| Univariate | Multivariate | AUC | Univariate | Multivariate | AUC | ||||||

| OR | p-value | OR | p-value | OR | p-value | OR | p-value | ||||

| Numerical bLVEF | 0.96 (0.95~0.97) | 0.97 (0.96~0.98) | 0.69 | 0.97 (0.97~0.98) | 0.97 (0.97~0.98) | 0.63 | |||||

| Categorized bLVEF | 0.47 (0.38~0.58) | 0.50 (0.40~0.62) | 0.70 | 0.59 (0.54~0.64) | 0.59 (0.54~0.65) | 0.64 | |||||

| [85, 120) | 0.40 (0.23~0.71) | 0.41 (0.23~0.73) | 0.38 (0.29~0.50) | 0.39 (0.30~0.51) | |||||||

| [120, 135) | 0.25 (0.15~0.42) | 0.27 (0.16~0.46) | 0.26 (0.20~0.32) | 0.26 (0.21~0.33) | |||||||

| [135, INF) | 0.08 (0.03~0.17) | 0.10 (0.04~0.22) | 0.21 (0.16~0.27) | 0.21 (0.16~0.28) | |||||||

| Numerical LVEF | 0.94 (0.92~0.96) | 0.94 (0.92~0.96) | 0.66 | 0.94 (0.93~0.95) | 0.94 (0.93~0.95) | 0.64 | |||||

| Categorized LVEF | 2.37 (1.71~3.20) | 2.48 (1.77~3.40) | 0.64 | 2.65 (2.30~3.05) | 2.65 (2.29~3.06) | 0.63 | |||||

| [50, INF) | |||||||||||

| [40, 50) | 2.21 (1.25~3.70) | 2.30 (1.29~3.91) | 2.71 (2.16~3.36) | 2.68 (2.13~3.34) | |||||||

| 5.88 (2.80~11.14) | 6.50 (3.02~12.68) | 6.89 (4.93~9.50) | 6.98 (4.96~9.72) | ||||||||

| Numerical BSA | 0.10 (0.03~0.33) | 0.21 (0.05~0.99) | 0.05 | 0.63 | 0.58 (0.35~0.97) | 0.04 | 0.54 (0.29~1.01) | 0.05 | 0.52 | ||

| Categorized BSA | 0.70 (0.60~0.82) | 0.76 (0.62~0.91) | 0.63 | 0.94 (0.88~10.00) | 0.04 | 0.93 (0.86~10.00) | 0.05 | 0.53 | |||

| [1.68, 1.79) | 1.12 (0.65~1.91) | 0.69 | 1.30 (0.73~2.32) | 0.37 | 0.93 (0.72~1.21) | 0.58 | 0.88 (0.67~1.16) | 0.37 | |||

| [1.79, 1.87) | 0.73 (0.40~1.31) | 0.29 | 0.90 (0.46~1.73) | 0.75 | 0.85 (0.65~1.11) | 0.22 | 0.79 (0.58~1.06) | 0.11 | |||

| [1.87, 1.97) | 0.38 (0.17~0.77) | 0.52 (0.22~1.14) | 0.11 | 0.81 (0.61~1.06) | 0.12 | 0.76 (0.56~1.03) | 0.08 | ||||

| [1.97, INF) | 0.22 (0.08~0.51) | 0.33 (0.11~0.82) | 0.02 | 0.78 (0.59~1.02) | 0.07 | 0.74 (0.54~1.02) | 0.07 | ||||

LVEF, left ventricular ejection fraction; BSA, body surface area; bLVEF, BSA-weighted LVEF; AUC, area under the curve; eGFR, estimated glomerular filtration rate; INF, infinity. Age, gender, smoking within two weeks before surgery, diabetes, hypertension, hyperlipidemia, last test of serum creatinine before surgery, last test of serum total cholesterol before surgery, last test of serum low-density lipoprotein before surgery, last test of blood glucose before surgery, use of cardiopulmonary bypass (CPB), preoperative eGFR, and previous cerebrovascular events were used for the multivariate regression. bLVEF was categorized into 4 groups based on a weight of tree-like segmentation binning.

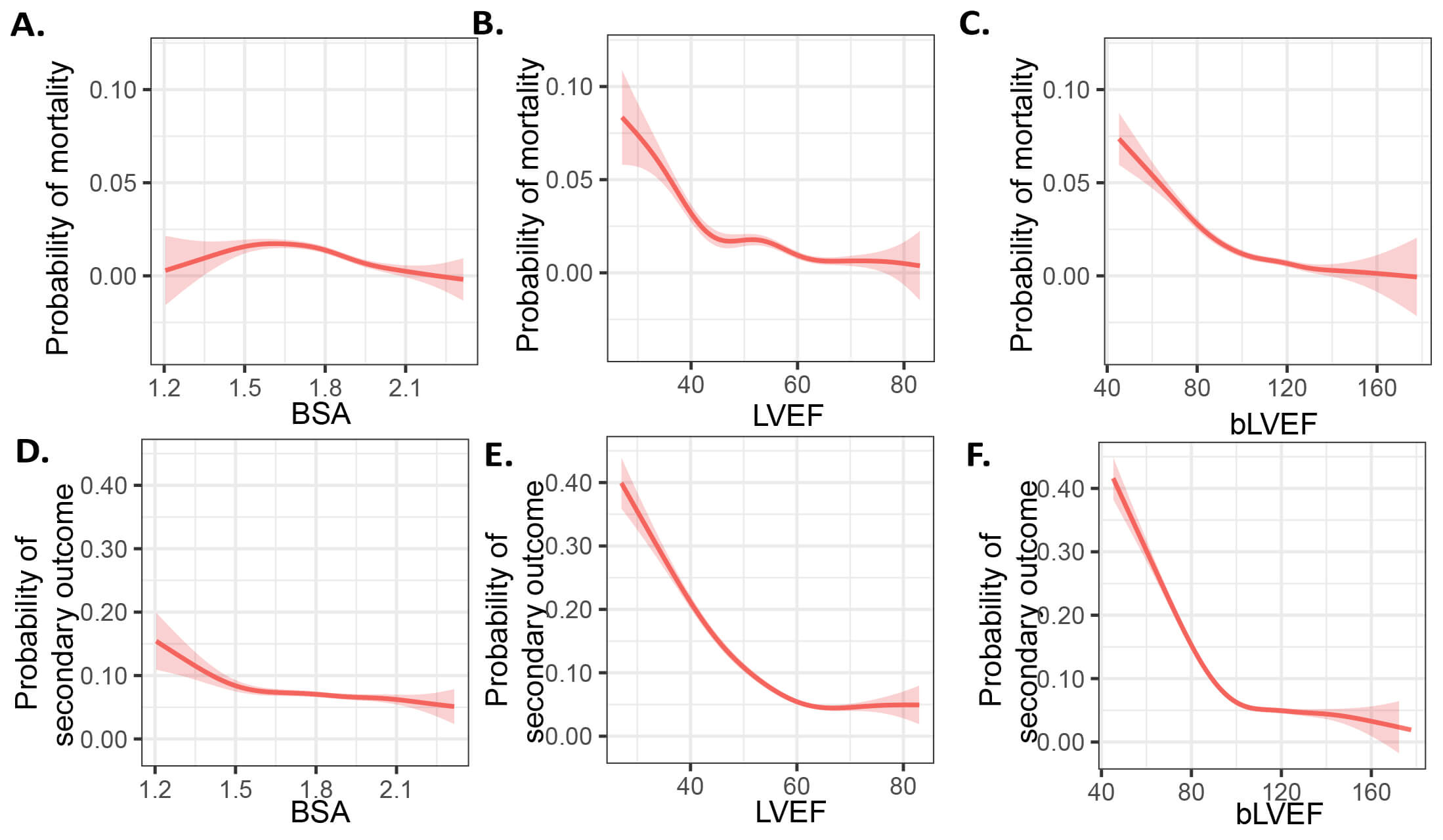

Fig. 1.

Fig. 1.

BSA, LVEF and bLVEF for primary and secondary endpoints. (A–C) Probability of mortality and (D–F) adverse events using a generalized additive model. LVEF, left ventricular ejection fraction; BSA, body surface area; bLVEF, BSA-weighted LVEF.

The mean BSA is 1.82

To evaluate bLVEF as a predictor of postoperative mortality and adverse events,

as well as to compare its predictive efficacy with other outcome predictors, we

performed univariate and multivariate logistic regression analyses. Our results

indicated a significant correlation between bLVEF and postoperative mortality,

with findings showing an adjusted OR of 0.97 (95% CI: 0.96–0.98, p

To enhance the practicality of bLVEF in clinical applications, we employed a

tree-based segmentation method to categorize bLVEF into discrete ranges. Our

analysis revealed four distinct categories: [0, 85), [85, 120), [120, 135), and

[135,

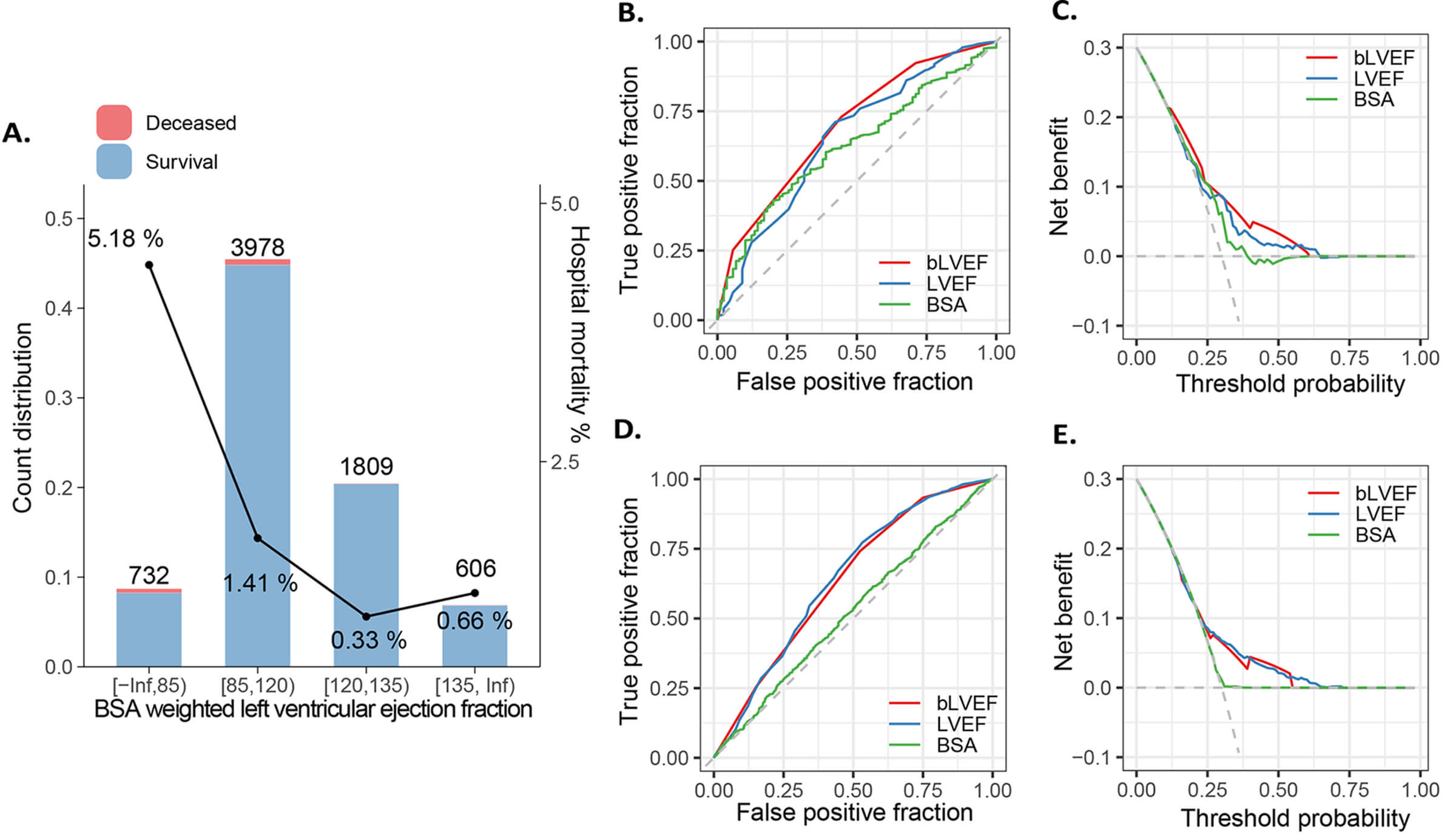

Fig. 2.

Fig. 2.

Segmentation of bLVEF and its abilities to predict clinical outcome. (A) Supervised tree-like segmentation of bLVEF (B) ROC and (C) decision curve analysis for mortality, and (D,E) secondary outcomes. bLVEF, BSA-weighted LVEF; LVEF, left ventricular ejection fraction; BSA, body surface area; ROC, receiver operating characteristic.

In this multi-center cohort investigation, we found that (1) low LVEF is a significant predictor of postoperative survival and adverse events; (2) BSA exhibited a slight negative correlation with LVEF; (3) bLVEF emerged as the most consistent predictor of mortality compared to BSA and LVEF; and (4) a bLVEF cutoff of 85 effectively identified patients at high risk of mortality.

Cardiac surgery improves survival in patients with advanced left ventricular

dysfunction compared to medical management [20]. However, low preoperative LVEF

is a known risk factor for the adverse outcomes following CABG [21]. Since

Benetti et al. [2] successfully performed OPCABG with the emphasis on

myocardial protection and the surgeon’s increasing proficiency in bypass

grafting, OPCABG has become a well-developed and safe procedure [22]. Recent

years have seen increased interest in its use for severe coronary artery disease,

with several studies highlighting its efficacy in patients with low LVEF [23].

Shennib et al. [24] reported favorable outcomes and low mortality rates

in patients with impaired ventricular function undergoing off-pump surgical

revascularization. Arom et al. [22] discovered that performing

multivessel coronary artery bypass using the OPCAB technique is both suitable and

feasible for patients with left ventricular function at or below 30%. In

addition, Ueki et al. [10] reported that OPCABG is linked to

significantly lower rates of early mortality and morbidity in patients with an

ejection fraction of less than 30%. Despite these findings, comparative studies

on OPCABG across different EF categories remain limited. In our cohort, 7093

(89.48%) patients had normal LVEF, 639 (8.06%) had HFmrEF, and 195 (2.46%) had

HFrEF, consistent with previously reported population distributions [25].

Patients with HFrEF or HFmrEF exhibited higher rates of diabetes, hypertension,

impaired kidney function, and prior myocardial infarctions, along with elevated

LVEDd and LAD, worse NYHA Functional Classification scores, and greater statin

use (p for trend

CAD with reduced EF presents a significant challenge to OPCABG. Proper exposure

of the anastomosis site during OPCABG necessitates cardiac manipulation, which

can compress the left ventricular outflow tract and lead to hypotension. In

patients with low LVEF, the limited cardiac reserve makes them highly susceptible

to abrupt drops in blood pressure. Additionally, patients with left main trunk

and three-vessel disease are at increased risk of malignant arrhythmias during

cardiac manipulation [4, 26, 27]. Therefore, it is necessary to implement

appropriate emergency measures and coordinate with anesthesiologists before

repositioning the heart. The use of IABP helps to improve the success rate of

OPCABG surgery [28]. Suzuki et al. [29] indicated that preoperative IABP

therapy in high-risk coronary patients effectively prevents hemodynamic

instability and yields surgical outcomes similar to those seen in moderate to

low-risk patients. In our study, HFrEF and HFmrEF were identified as strong

negative prognostic factors for mortality, suggesting that a decrease in the odds

of mortality compared to the reference group (LVEF

Echocardiography is extensively utilized for diagnosing and managing cardiac conditions, particularly in the preoperative assessment of patients undergoing cardiac surgery [30, 31]. However, cardiac surgeons often rely on unstandardized absolute values when interpreting echocardiographic parameters, despite the influence of body mass factors on heart structure [32]. Assessing echocardiographic indicators solely based on absolute values does not enable precise diagnosis of cardiac conditions [33]. BSA, a metric for characterizing body size, is frequently employed to normalize mass and volume and to index physiological parameters related to cardiovascular disease [34, 35]. A study has indicated that left ventricle (LV) diameter provides a basic and simplified evaluation of a three-dimensional structure, failing to account for the more intricate variations in ventricular shape or size [36]. To address this, the American Society of Echocardiography and the European Association of Cardiovascular Imaging recommended indexing echocardiographic parameters, such as right and left ventricular sizes, to BSA [35]. Moreover, the Simpson’s biplane method, which uses orthogonal long-axis views, allows for a more accurate calculation of LV volume that can be indexed to BSA for improved precision [37]. LVEF is a parameter obtained from echocardiography that measures the amount of blood ejected from the heart’s left ventricle—the primary pumping chamber—with each contraction [38]. Furthermore, LVEF is acknowledged as an independent risk factor for CABG. A lower ejection fraction correlates with increased perioperative mortality and reduced five-year survival rates [39, 40]. While the conventional definition of the normal range for EF is derived from the general population, encompassing groups with varying clinical characteristics and prognoses. Thuijs DJFM et al. [25] found a U-shaped association between LVEF and all-cause mortality three years after CABG. In our study, we identified a J-shaped curve in LVEF when predicting perioperative mortality in patients undergoing OPCABG. This observation is of considerable clinical significance, as it suggests a potential for misinterpretation among cardiac clinicians. Specifically, clinicians may incorrectly assume that patients with an LVEF at the relatively “good” level have adequate cardiac function, thus deeming them to be at a low risk for perioperative complications. However, this oversimplification can obscure the true risks associated with the procedure. Given the complexity of heart failure and the multitude of factors influencing perioperative outcomes, it is imperative to consider all relevant risk factors beyond just LVEF when making surgical decisions for patients undergoing OPCABG. Relying solely on LVEF could lead to incomplete assessments of a patient’s functional status, potentially compromising patient safety. To mitigate this risk of bias, we advocate for the normalization of LVEF to BSA, a practice that enhances the reliability of prognostic assessments. By doing so, we established a critical numerical threshold of 85 as a ‘divider’ that serves to refine the prediction of perioperative mortality. This threshold represents a key parameter in stratifying patient risk, enabling more accurate and personalized surgical decision-making. It is worth noting that the observed patterns are hypothesis-generating and require validation in cohorts with harmonized analytical frameworks. Ultimately, our findings underscore the importance of incorporating LVEF normalization into clinical practice, ensuring that all relevant factors are weighed appropriately to optimize patient outcomes in OPCABG. This approach can significantly improve the predictive accuracy regarding mortality and enhance the overall management of patients undergoing coronary revascularization.

There are limitations in our study. Firstly, the retrospective cohort design relies on historical patient data, which restricts the availability of comprehensive preoperative activity tolerance information. Additionally, the extended follow-up period resulted in a considerable loss to follow-up. Secondly, common post-surgery complications such as severe heart failure and atrial fibrillation were not included due to challenges in accurately documenting them during follow-up assessments. Thirdly, the study did not discuss gender differences, which will be further explored in future research. Lastly, body surface area is calculated using a formula based on weight and height, which does not reflect the true surface area of an individual. Furthermore, factors like age, gender, and race may confound the BSA measurement, highlighting the need for future research to investigate the correlating variables associated with BSA.

bLVEF serves as a key predictor of mortality in OPCABG, effectively eliminating BSA-related bias and demonstrating a strong capacity to predict mortality.

CABG, coronary artery bypass grafting; OPCABG, off-pump coronary artery bypass grafting; HF, heart failure; LVEF, left ventricular ejection fraction; BMI, body mass index; BSA, body surface area; GFR, glomerular filtration rate; HFrEF, heart failure with reduced ejection fraction; HFmrEF, heart failure with mid-range ejection fraction; LVEDd, left ventricular end-diastolic diameter; LAD, left atrial dimension; ACEI, angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitor; ARB, angiotensin receptor blocker; ECMO, extracorporeal membrane oxygenation; IABP, intra-aortic balloon pump; ICU, intensive care unit; MSA, multiple system atrophy; AKI, acute kidney injury; MI, myocardial infarction; AUC, area under the curve.

All data reported in this paper will be shared by the lead contact upon request.

HBZ and YQL conceived and designed the study; ZPW, ZHZ, YHL, MYW, HBW, DX, YC gathered the data; CYL, ZPW, ZHZ performed statistical analyses; ZPW, ZHZ wrote the first draft of the manuscript; NL, JKL made critical revision of the manuscript for key intellectual component. All authors contributed to the conception and editorial changes in the manuscript. All authors provided approval of the final version of the manuscript. All authors have participated sufficiently in the work and agreed to be accountable for all aspects of the work.

The study was carried out in accordance with the guidelines of the Declaration of Helsinki and approved by the Ethics Committee of Fuwai Hospital (Approval No: 2017-943), and all of the participants provided signed informed consent.

We gratefully thank the Peking University Clinical Research Institute for evaluating the data quality and supervising data collection. We gratefully thank Prof. Jing Liu in Beijing Anzhen Hospital for the statistics consulting. We wish thank Prof. Zhe Zheng in Fuwai Hospital for many helpful courtesies and facilities in this study.

This work is supported by the Beijing Science and Technology Commission of China (grant number: D171100002917001 and D171100002917003) and the Beijing Anzhen Hospital High Level Research Funding (grant number: 2024AZC1003).

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Supplementary material associated with this article can be found, in the online version, at https://doi.org/10.31083/RCM26681.

References

Publisher’s Note: IMR Press stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.