1 Department of Translational Medicine, University of Eastern Piedmont, 28100 Novara, Italy

2 Division of Cardiology, Maggiore della Carità Hospital, 28100 Novara, Italy

Abstract

Transcatheter valve procedures have become a cornerstone in the management of patients with valvular heart disease and high surgical risk, especially for aortic stenosis and mitral and tricuspid regurgitation. Cardiopulmonary exercise testing (CPET) is generally considered the gold standard for objectively quantifying functional capacity, providing a comprehensive evaluation of the human body's performance, particularly in patients with heart failure (HF). Its accurate assessment is valuable for exploring the pathogenetic mechanisms implicated in HF-related functional impairment. It is also useful for objectively staging the clinical severity and the prognosis of the disease. The improvement in functional capacity after transcatheter valve procedures may be clinically relevant and may provide prognostic information, even in this setting. However, it remains to be fully determined as data on the topic are limited. This review aims to summarize the available evidence on the usefulness of CPET to assess functional improvement in patients undergoing transcatheter valve procedures.

Keywords

- cardiopulmonary exercise testing

- heart failure

- transcatheter valve procedures

Valvular heart disease (VHD) is a leading cause of acute and chronic heart failure (HF) [1]. Aortic stenosis (AS) and mitral regurgitation (MR) are the main aetiologies of severe native VHD, often linked to congestive HF [2]. Severe tricuspid regurgitation (TR) associated with right-sided HF has been adequately recognized only recently [1]. Transcatheter valve repair/replacement now represents a cornerstone in managing patients with VHD and is widely performed since it can ameliorate the poor prognosis of these patients [1, 3]. Traditionally, AS, MR, and TR conditions have been treated surgically [4]. However, the choice between transcatheter valve procedures or surgery should be made using a shared decision-making approach, considering the patient’s preferences, surgical risk, and anatomical characteristics. A multidisciplinary team of interventional cardiologists, cardiothoracic surgeons, radiologists, echocardiographers, nurses, and social workers, known as the “heart team”, should discuss all these features to determine the best course of action for each patient [1]. In candidate patients for percutaneous valve repair, a pre-procedural multimodality imaging assessment, mainly including transthoracic echocardiography, transesophageal echocardiography, and computed tomography, is essential for planning the intervention and selecting the most appropriate device to guarantee optimal outcomes [5].

Cardiopulmonary exercise testing (CPET) is likely the most comprehensive full-body test, providing a complete evaluation of the human body’s performance [6]. This test has been significantly improved throughout the years, especially in patients with HF, as it provides a considerable amount of highly valuable diagnostic and prognostic information [7, 8]. Exercise intolerance is an important prognostic characteristic related to HF [9]. Thus, accurate quantification of exercise intolerance, is beneficial for exploring the pathogenetic mechanisms implicated in functional impairment and objectively staging the clinical severity of the disease [9]. Health-related quality of life questionnaires (e.g., Kansas City Cardiomyopathy Questionnaire (KCCQ)) are commonly used in HF patients, yet they are subjective to personal interpretation and do not reflect the objective clinical and pathophysiological status [10]. Basically, the two methods currently used in daily clinical practice to define the extent of exercise restriction are the 6-minute walking test (6MWT) [11] and CPET [12]. Guazzi et al. [13] established that, even if the 6MWT is a straightforward and well-founded first-line test to assess the exercise limitation in patients with HF, no evidence supports its use as a prognostic tool to replace CPET-derived information. The advantage of CPET is that it assesses exercise tolerance and evaluates the individual’s pathophysiological responses to the body’s increased metabolic demands by analyzing gas exchange (primarily O2 and CO2) and other ventilatory variables [14]. This technique enables clinicians to investigate the causes of dyspnoea and fatigue, accurately differentiate between cardiac and pulmonary disease, improve decision-making and outcome prediction, and objectively identify targets for therapy [15]. CPET is routinely used in the prognostic evaluation of patients with HF, where the prognostic significance of peak oxygen consumption (peak VO2) and the minute ventilation/carbon dioxide production (VE/VCO2) slope is well established [16, 17]. Furthermore, CPET has become a reproducible and safe technique [7]. Previously, standard indications of CPET did not include evaluating patients with VHD, as data remain limited [18]. However, the clinical assessment of these pathological conditions by CPET has been considered an option by expert consensus since 2016 [19]. Nevertheless, despite mounting evidence, CPET is not mentioned in the European Society of Cardiology 2021 guidelines for VHD [1].

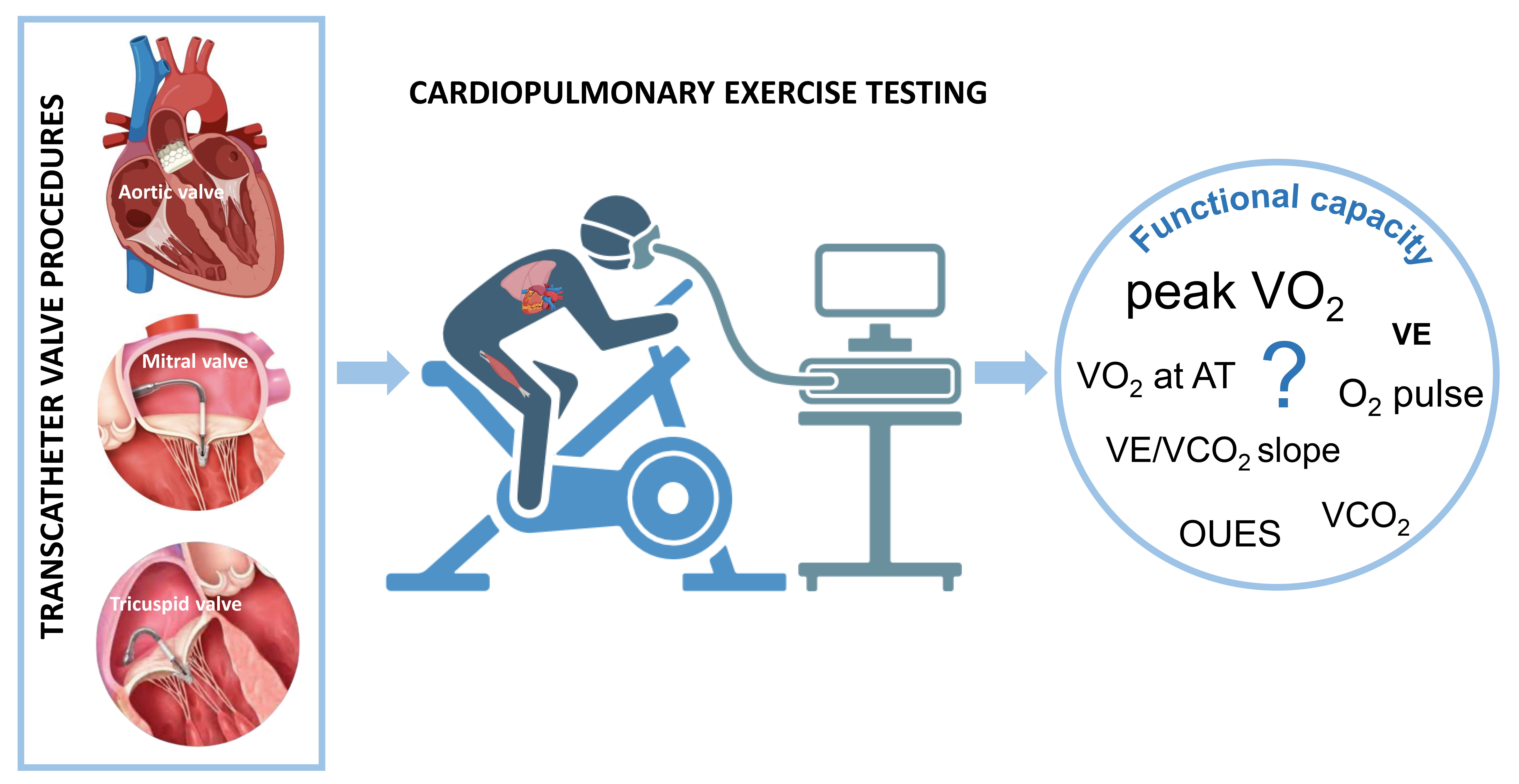

This review addresses such issues and attempts to summarize the evidence on the usefulness of CPET in patients undergoing transcatheter valve procedures (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1.

Fig. 1.

Cardiopulmonary exercise testing in transcatheter valve procedures. Transcatheter valve procedures have become a cornerstone in managing patients with valvular heart disease and high surgical risk. However, the objective quantification of functional improvement after procedures remains elusive due to a lack of robust data. Cardiopulmonary exercise testing, providing a comprehensive evaluation of the human body’s performance, may emerge as a promising tool in this setting. VE/VCO2 slope, minute ventilation/carbon dioxide production slope; VO2, oxygen consumption; VCO2, carbon dioxide production; AT, anaerobic threshold; VE, minute ventilation; OUES, oxygen uptake efficiency slope.

The recent European Valvular Heart Disease II survey showed that AS is the

leading cause of single-valve disease [2]. The increase in the prevalence of this

condition correlates with age, with 26.5% of AS patients being older than 80

years. Due to the unfavorable prognosis, clinical practice guidelines currently

recommend early intervention in symptomatic patients with severe AS [1]. However,

many patients are considered asymptomatic, and valve repair is indicated when

only the left ventricular ejection fraction is reduced or conventional exercise

testing cannot be tolerated [1]. An outpatient follow-up and conservative

management are recommended for patients who do not meet either criteria [1].

Therefore, the decision to repair a severely stenotic aortic valve in

asymptomatic patients is more complex. Transcatheter aortic valve implantation

(TAVI) is an effective and safe treatment alternative for patients with severe

AS, particularly if vulnerable and with multiple comorbidities. Compared to

traditional surgical replacement, TAVI has indications primarily in older and

frail patients with various risk factors and concomitant diseases [20].

Nevertheless, the role of TAVI in improving patients’ functional capacity has yet

to be established. Murata et al. [21] prospectively enrolled 58 patients

undergoing CPET less than 1 month after successful TAVI. Patients were followed

for

Generally, older patients undergoing TAVI have impaired mobility and reduced

quality of life [22, 23]. Thus, the benefit of post-interventional exercise

training in improving their physical capacity remains to be robustly

demonstrated. Pressler et al. [24] reported a prospective pilot study

where 27 post-TAVI patients were randomized 1:1 to an intervention group

performing 8 weeks of supervised combined aerobic exercise and resistance

training or usual care. The primary endpoint was the between-group difference in

change of peak VO2, as assessed by CPET from baseline to 8 weeks. A change

favoring the training group was observed, with a between-group significant

difference in change of peak VO2 (+3.7 mL/min/kg, 95% CI, 1.1–6.3,

p = 0.007) and oxygen uptake at anaerobic threshold (VO2 at AT:

+3.2 mL/min/kg, 95% CI, 1.6–4.9; p

Organic MR is caused by a primary abnormality of one or more elements of the

valve apparatus [1]. Moreover, in patients with HF and dilated left ventricle, MR

can develop due to geometric displacement in papillary muscles and chordae

tendineae, which impairs leaflet coaptation [25]. This functional MR increases

the severity of volume overload and is associated with reduced quality of life,

repeated hospitalizations for HF, and poor survival [26]. Guideline-directed

medical therapy and cardiac resynchronization therapy can deliver symptomatic

relief, improve left ventricular function, and, in some patients, reduce the

severity of MR [26]. Neither surgical valve replacement nor surgical valve repair

has been shown to reduce hospitalization rates or death in patients with

functional MR, and both procedures carry a significant risk of complications [1].

As a result, most patients with HF and functional MR are treated conservatively

and often have few therapeutic alternatives. For those at high surgical risk,

transcatheter mitral valve interventions represent an emerging treatment option

[27] without relevant differences in outcome between the two MR aetiologies

[28, 29]. Due to the complexity of the mitral valve anatomy, different techniques

have been developed to target specific components of MR. Mitral transcatheter

edge-to-edge repair (TEER) utilizes a clip to bring the valve leaflets closer

together, effectively treating severe MR and avoiding the risks associated with

open surgery [30]. The COAPT trial [31] enrolled 614 patients with

moderate-to-severe or severe functional MR and HF who were randomized 1:1 to

receive either TEER and medical therapy (device group) or medical therapy alone

(control group). The annualized rates of all-cause hospitalization for HF within

24 months were 35.8% per patient–year in the device group vs. 67.9% per

patient–year in the control group (hazard ratio (HR) 0.53; 95% CI 0.40 to 0.70;

p

| Study (year) | Type of study | No. of patients | Follow-up, months | CPET-derived variables | |||||||||||

| Pre-TEER | Post-TEER | Change | |||||||||||||

| Peak VO2, mL/min/kg or (mL/min) | VO2 at AT, mL/min | O2 pulse, mL/beat | VE/VCO2 slope | Peak VO2, mL/min/kg or (mL/min) | VO2 at AT, mL/min | O2 pulse, mL/beat | VE/VCO2 slope | Peak VO2, mL/min/kg or (mL/min) | VO2 at AT, mL/min | O2 pulse, mL/beat | VE/VCO2 slope | ||||

| Mitral regurgitation | |||||||||||||||

| Benito-González et al. (2019) [33] | Prospective | 11 | 6 | 9.8 | 510 | 7.2 | 30 | 13.5 | 850 | 8.3 | 31.5 | +3.7 | +340 | + 1.1 | +1.5 |

| Vignati et al. (2021) [35] | Prospective | 66 | 6 | (936) | 708 | 34.2 | (962) | 740 | 33.9 | (+26) | +32 | –0.3 | |||

| Koh (2023) [34] | Retrospective | 7 | 7 |

14.3 | 792 | 6.9 | 35.5 | 17.8 | 887 | 7.8 | 33.4 | +3.5 | +95 | +0.9 | –2.1 |

| Tricuspid regurgitation | |||||||||||||||

| Volz et al. (2022) [37] | Retrospective | 11 | 3 | 9.5 | 639 | 39 | 11.4 | 749 | 38 | +1.9 | +110 | –1 | |||

| Cumitini et al. (2024) [38] | Case report | 1 | 1 | 12 | 610 | 6.2 | 31.8 | 14.4 | 750 | 8.2 | 31.8 | +2.4 | +140 | +2 | 0 |

All CPET values (except for the case report) are expressed as the mean or median. CPET, cardiopulmonary exercise testing; TEER, transcatheter edge-to-edge repair; VE/VCO2 slope, minute ventilation/carbon dioxide production slope; VO2, oxygen consumption; VO2 at AT, oxygen uptake at anaerobic threshold.

TR is a widespread valve disease in Western countries, with a prevalence of

In patients with HF, the presence of VHD has a prognostic significance, while new transcatheter treatment options have emerged. In this context, CPET is accurate for evaluating and managing various cardiopulmonary symptoms and clinical conditions. Therefore, it may be a useful tool for several purposes. For example, if baseline CPET parameters are anomalous, the test could discriminate borderline patients for performing or not performing the intervention. It is also helpful to guide clinical management and follow-up, especially in patients with predefined poorer variables. After percutaneous procedures, CPET may provide objective evidence documenting changes in the cardiorespiratory endurance of the patient (Table 2). By objectifying an improvement in functional capacity, CPET may increase the strength of guideline recommendations for percutaneous valve repair. Since published studies derive from small, non-randomized series, it is important to recognize that their results are only hypothesis-generating and require further confirmation in adequately powered prospective investigations.

| Assess functional capacity and exercise intolerance |

| Recognize different causes of exercise limitation |

| Discriminate borderline patients for the intervention |

| Contribute to clinical management, especially for patients with predefined poorer values |

| Evaluate clinical progression during follow-up |

| Provide objective variables documenting changes in cardiorespiratory endurance after the procedure |

Recently, numerous other diagnostic tools have been identified, in addition to

CPET (also called “complex CPET” [6]), to provide additional clinical and

pathophysiological data that could be used in patients undergoing transcatheter

valve procedures [6]. Non-invasive CO measurement has been proposed, and two

approaches during the exercise are the most recognized: the Physioflow technique

and the inert gas rebreathing technique. The former is based on thoracic

bioimpedance measurements and the latter utilizes a blood-soluble and a

blood-insoluble inert gas. The concentration of the blood-soluble gas drops

during rebreathing at a rate related to the pulmonary blood flow, while the

insoluble gas establishes the lung volume [6, 44, 45]. Both tools allow VO2 to

be split into its two components, CO and

Furthermore, near-infrared spectroscopy quantitatively evaluates oxygenated and deoxygenated hemoglobin [46], thereby representing a promising tool for better understanding the role of O2 delivery to the working muscle and its use [6, 47]. Arterial blood sampling has a well-defined clinical role in evaluating the ratio of death to tidal volume during the exercise, because it can only be reliably assessed by directly measuring arterial CO2 partial pressure [48]. Vignati et al. [35] suggested that the restriction of the assessment to VO2 only does not allow an accurate evaluation of the impact of therapeutic interventions, such as TEER, cardiac resynchronization therapy, or training, because of the significant change in blood flow delivery during the exercise [36, 49]. Thus, all the aforementioned techniques can be combined with CPET in patients with VHD to better define the pathophysiology of exercise in this setting.

Although limited by the small number of patients enrolled in the studies and the lack of powered randomized trials, transcatheter valve procedures appear to be associated with improved cardiopulmonary performance. In this setting, detecting such functional improvement may be clinically significant and have a prognostic relevance. Given its objective, specific, and unique information, CPET can emerge as a promising tool for addressing this issue.

LC, AG and GP determined the topic of and designed the procedure for this literature review. LC, AG and GP conducted the literature search and wrote the review. LC, AG and GP assisted with data analysis, interpretation, and editing of corresponding sections of the text. All authors read and approved the final manuscript. All authors have participated sufficiently in the work and agreed to be accountable for all aspects of the work.

Not applicable.

The authors are grateful to our colleagues in cardiology and nurses who worked to provide high-quality of care for our patients.

This research received no external funding.

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

Publisher’s Note: IMR Press stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.